Abstract

Given the overwhelming evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding, and yet the low prevalence rates in the UK, it is crucial to understand the influences on women's infant feeding experiences to target and promote effective support. As part of an evaluation study of the implementation of the UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI) Community Award within two primary (community‐based) care trusts in North West England, 15 women took part in an in‐depth interview to explore their experiences, opinions and perceptions of infant feeding. In this paper, we have provided a theoretical interpretation of these women's experiences by drawing upon Aaron Antonovsky's Sense of Coherence (SOC) theory. The SOC is a global orientation to how people are able to cope with stressors and maintain a sense of well‐being. The three constructs that underpin the SOC are ‘comprehensibility’ (one must believe that one understands the life challenge), ‘manageability’ (one has sufficient resources at one's disposal) and ‘meaningfulness’ (one must want to cope with the life challenge). In this paper, our interpretations explore how infant feeding is influenced by the ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’ of this event; contextualized within a wider socio‐cultural perspective. The findings of this paper offer a unique means through which the influences on women's experiences of infant feeding may be considered. Recommendations and suggestions for practice in relation to the implementation of the BFI have also been presented.

Keywords: Sense of coherence, infant feeding, women's experiences, socio‐cultural influences

Introduction

The protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding has become a major international public health goal based on overwhelming scientific evidence related to the health benefits of exclusive breastfeeding for mother and child (WHO 2003). However, it is only more recently that studies have sought to understand women's experiences of feeding their babies whether by breastfeeding or using formula milk or both. These studies have been collated in several meta‐syntheses. Nelson (2006) conducted a meta‐synthesis of qualitative breastfeeding studies and reported that breastfeeding as an embodied experience required commitment and adaptation from the mother and support from multiple sources. McInnes & Chambers (2008) conducted a synthesis of qualitative papers focusing upon support given to breastfeeding mothers. Health service support for women was reported to be less than satisfactory due to time pressures on staff, lack of staff availability, inadequate guidance, unhelpful practices and conflicting advice. Larsen et al. (2008) conducted a meta‐synthesis related to influences upon women's confidence in breastfeeding. They reported that women's confidence was undermined by unmet expectations, and these related in part to mixed messages from their social networks, health professionals and breastfeeding discourses. Schmied et al. (2009) conducted a meta‐synthesis of women's perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support; they reported that support for breastfeeding occurs along a continuum from authentic presence at one end to disconnected encounters at the other. They identified a facilitative approach vs. a reductionist approach, as contrasting styles of support women experienced as helpful or unhelpful. These studies illuminate some key issues related to women's experiences, but there is little theoretical focus upon women's coping strategies with regard to feeding their infants. The studies mainly focus upon breastfeeding, but these provide a partial picture as less than 35% of infants worldwide are exclusively breastfed for even the first four months of life (WHO 2003).

Key messages

-

•

Antonovsky's Sense of Coherence (SOC) theory offers an in‐depth interpretive lens to explore and understand infant feeding experiences

-

•

Women's experiences of infant feeding are influenced by the extent to which they are ‘comprehensible’, ‘manageable’ and ‘meaningful’

-

•

Application of the SOC theory and recognition of socio‐cultural influences needs to be considered when implementing global policies such as the WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative Award.

The theoretical insights of medical sociologist Aaron Antonovsky provide a useful conceptual lens to support understanding of women's experiences of infant feeding. Aaron Antonovsky's fundamental contribution was the philosophical salutogenic question of what creates health and well‐being. He became interested in successful coping strategies and constructed the notion of general resistance resources (GRRs). GRRs are identified as buffering, ameliorating or mediating mechanisms, believed to reduce the impact of stressors and subsequently prevent breakdown (illness, disease) (Antonovsky, 1979). GRR's operate on a range of levels, such as physiological, psychological, cultural and social. Examples of these include intelligence, identity, social support, family ties, cultural stability, religion, healthy lifestyle and so on (Antonovsky 1979, 1987).

Antonovsky argued that stressors are omnipresent in our lives, and that it is the subjective rather than objective perception of the event which renders it stress inducing (Antonovsky 1987, p. 93). He also believed that well‐being is determined by how people respond to and deal with the stressor, rather than purely the availability of GRRs at someone's disposal. These contemplations eventually led to his development of the Sense of Coherence (SOC), which he viewed as a theory of successful coping (Antonovsky 1979, 1987). Antonovsky theorized that a person's SOC is determined by the extent to which life events are ‘meaningful’, ‘comprehensible’ and ‘manageable’. It represents a global attitude that explains the extent to which people have confidence that life events are predictable, structured and understandable (comprehensible), that the person has resources needed to meet the demands of the life events (‘manageability’) and that the demands are worthy of investment and effort (meaningfulness) (Antonovsky 1987). A person with a strong SOC is considered to be able to select from a range of successful coping strategies to effectively deal with the stressor and remain in good health. While Antonovsky's theories are applicable cross‐culturally, he considers that a person's SOC is constructed within their social, cultural and historical background as well as through the idiosyncratic events in the individual's own life.

Antonovsky developed a quantitative tool to operationalize his SOC theory (Antonovsky 1987). A number of studies have been undertaken to validate the SOC and assess its relationship with psychological variables such as anxiety and traumata (Eriksson & Lindström 2005). These studies have concluded that a participant's SOC determines their level of psychopathology following a stressful life event (Antonovsky & Sagy 2001; Engelhard et al. 2003).

The SOC scale has been utilized within a childbirth and motherhood arena. Hildingsson et al. (2008) found that women who were dissatisfied with partner support had lower SOC scores and low emotional and physical well‐being. Oz et al. (2009) revealed that women with a strong SOC were more likely to experience an uncomplicated childbirth compared with women with a lower SOC score.

We consider that the SOC's three underpinning concepts of ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’ offer an important theoretical lens to explore how people make sense of and interpret their infant feeding experiences. Furthermore, a qualitative interpretation of these constructs may illuminate meanings and key influences that impact upon women's choices, decisions and experiences of infant feeding. The aim of this paper was therefore to provide a theoretical interpretation of the ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’ of women's experiences of infant feeding.

As this data set was originally collected to help inform the UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI) community award implementation, the relevance of the SOC concepts to help embed the BFI and promote breastfeeding are considered within the discussion.

Materials and method

Context

The interviews with women were part of an evaluation into how the BFI was being implemented within two Primary Care Trusts in North West England. The BFI is a global strategy developed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNICEF in 1991 to protect, promote and support breastfeeding. The BFI is a fairly prescriptive, staged award designed to support the infrastructure of health or hospital facilities such as through the creation of policies, protocols, training, information networks and evaluation mechanisms. BFI accreditation is issued to facilities deemed to have reached the minimum externally auditable standards. As part of this evaluation, 15 women were interviewed to explore their views, attitudes and experiences of infant feeding.

Participants/recruitment

Health professionals engaged in the BFI evaluation were asked to recruit 2–3 women (irrespective of their infant feeding method) who they were currently working with, and who were willing to share their infant feeding experiences. The professionals were provided with copies of service user information sheets for subsequent distribution. The only selection criteria were that the women had recently had a baby (under 12 months post‐partum). Following verbal consent, health professionals provided the names, contact details and infant feeding methods to Gill Thomson (GT) (details of 25 women were provided by 12 professionals). While the nomination of participants by professionals may have had the potential for selection bias, a purposive sample of 15 participants was selected (by GT) to cover a broad range of ages and infant feeding experiences. All interviews were conducted by GT in the women's homes; each interview took between 50 and 90 min to complete.

The women recruited were between 4 weeks to 9 months post‐partum (mean of 16 weeks). The participants were aged between 19 and 39 years, with a mean age of 30 years. All the women were white‐British which, to a large extent, reflects the lack of ethnic diversity within these geographical locations (black and minority ethnic groups represent 1.6% and 2.9%, respectively, in these two areas). The participants were recruited from a range of socio‐demographic groups with participants living within areas of high and low deprivation. Ten of the women were married and five were living with their partners. Twelve of the women were first‐time mothers, two had two children and one had four children. All of the women had given birth in one of two large maternity units. Three of the infants were pre‐term, and the remainder were full‐term.

With regard to infant feeding, all of the women had originally intended to breastfeed. At the time of the interview, nine women were exclusively breastfeeding and one was mixed feeding. Four infants were on formula milk, though all had been breastfed for a period of time (from 3 days up to 4.5 months). One was feeding her baby breast milk, all of which was expressed and fed through a bottle (infant was 7 weeks at time of interview). This woman self‐defined herself as an ‘exclusive pumper’.

A semi‐structured interview schedule was developed for the evaluation by incorporating questions within the BFI audit tools for bottle feeding and breastfeeding mothers as well as open‐ended questions to uncover attitudes and meanings. The interviews specifically explored women's experiences of the information and support they had received regarding infant feeding; as well as factors perceived to help facilitate or prevent successful breastfeeding.

Ethical issues

The project was reviewed by the NHS Regional Committee and ethics approval was obtained through the University's ethics committee. At the start of the interview, the mothers were provided with a verbal overview of the nature and purpose of the study and any questions were answered. All participants were asked to sign a consent form. All interviews were digitally recorded following consent. A typed copy of the transcript was returned to the participants, and they were invited to amend or alter the information as appropriate. All participants were provided with a 2‐month period (from date of issue) for these changes to be completed and forwarded to GT. Two of the women made comments on the text providing further clarity of issues raised. Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identity of the participants.

Data analysis

All transcribed data were entered into the MaxQDA qualitative software package. Data collection and analysis was undertaken on a concurrent basis. Initially, the data were broken into global, organizing and basic themes using thematic networks analysis as described by Attride‐Sterling (2001). Data analysis identified a number of factors that influence and impact upon women's experiences, attitudes and perceptions of infant feeding.

Antonovsky's SOC theory was utilized as a conceptual lens through which to view the data. While the SOC offers a global orientation to health and well‐being, the underpinning constructs of this theory were found to resonate with how women externalize as well as internalize their decisions, choices and experiences around infant feeding. The analysis and interpretations revealed that women's experiences of infant feeding were influenced by the ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’ of this life event.

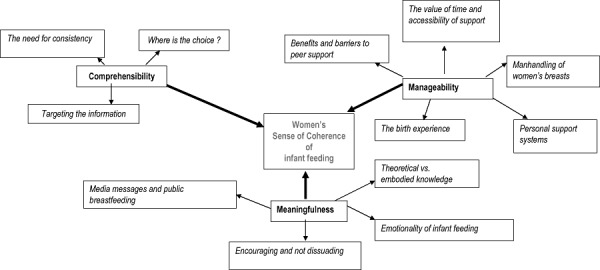

A pictorial representation of these three SOC concepts and the sub‐themes identified under each is displayed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Influences of a woman's sense of coherence towards infant feeding.

Findings

Comprehensibility

According to Antonovsky (1979), ‘comprehensibility’ is the extent to which a person perceives their world to be understandable, static, stable and consistent (as opposed to what he refers to as the ‘noise’ of chaotic, random, inexplicable and unpredictable stimuli). The stimuli the person receives from internal and external environments should make ‘cognitive sense’ (Antonovsky 1987, p. 16). The ‘comprehensibility’ of information that women receive and interpret in relation to infant feeding is, to a large extent, a direct reflection on how infant feeding practices in the UK have altered. Since the Second World War, the promotion and mass marketing of artificial milk has resulted in the UK moving from a predominantly breastfeeding culture towards a bottle feeding culture. While recent global and national policies now promote breastfeeding, the critical shift in socio‐cultural values, beliefs and practices over this time have played an important influence in terms of how women make ‘cognitive sense’ of infant feeding.

Antonovsky (1979) proposed that a person's SOC is a crucial element of their basic personality, culture or historical period. In this study, the cultural and historical period influenced women's ‘comprehensibility’ in terms of how information was targeted; women's ‘choices’ in relation to infant feeding; and how the ‘noise’ (Antonovsky 1979) of inconsistent messages and care threatened to destabilize women's cognitive interpretations. These issues are discussed in more depth below.

Targeting the information

Comprehensibility of infant feeding was influenced by how, or what information the health professionals provided to women. A number of the participants described a ‘one size fits all’ approach to information provision rather than amended or adapted to their individual needs, and this related to time shortages. In this study, some women preferred to read and self‐process written information, whereas others felt ‘bombarded’ by the abundance of literature provided. The latter women stated how they would have preferred ‘time’ to discuss issues, and be offered practical help and information:

They (professionals) told you to read the leaflets. I presumed it was a time thing. They didn't have the time to go through it with you in detail, they expected you to read it and come back with questions (Jenny).

Mothers reported a lack of information from health professionals for women who were not undertaking the classical ‘breastfeeding’ or ‘bottle‐feeding’ scenarios, for example the exclusive pumper. Others regarded the advice on positioning and attachment for breastfeeding as ‘technical’ and dissonant with their expectations of ‘natural feeding’. The fact that this advice or ‘noise’ may potentially destabilize women's cognitive decision‐making abilities needs to be considered:

. . . the way they are showing you how to do it, it sounds so technical, the latch, the position all that sort of thing and I think that is why women tend to give up as well (Jenny).

Others considered that professionals withheld information associated with potential risks for their infants in their desire to ‘protect’ mothers from potential distress. This concern for their welfare was not only considered ‘patronizing’, ‘unnecessary’ and ‘inappropriate’ but also threatened the stability and potential safety of women's knowledge to respond to certain risk situations:

We were being told about honey and Botchilism, and one of the mothers asked what it was, and one of the Health Visitors said it's a really bad tummy bug, and another mum said ‘just a tummy bug? it can kill your baby’. And the Health Visitor was like ‘I don't want to panic people and put fear in them’– and I was like well you need too. (Belinda)

The need for consistency

Antonovsky (1987) believed that for life to be comprehensible and understandable, it needs to include a level of predictability. In this study, inconsistencies in infant feeding information and support was a recurrent issue to emerge, as identified by others (McInnes & Chambers 2008). Frequent areas of contradiction related to the timing of feeds, how often to feed from each breast, when to introduce complementary foods and how to make up and store infant formula feeds:

Well I am not sure who to listen to really. There is my mum, his mum and then my Nan. Both [partner's] sisters who have children. Then there are health visitors or midwives or just medical people in general just going oh no you shouldn't be doing this, you should be doing it that way. . . . (Bernie)

These insights suggest that the changing and pervasive socio‐cultural influences on infant feeding have led to women receiving different information from various health professionals as well as via personal networks. Ultimately, this led to these participants experiencing confusion and anxiety.

Where is the choice?

Even though all the women had planned to breastfeed their infants, the cultural norm of bottle feeding meant that bottles, formula food and dummies were commonplace in their life worlds. The extent to which information about these products was provided by health professionals was found to impede or facilitate the ‘comprehensibility’ in relation to the choices that women made about infant feeding.

On one level, a number of women complained or voiced ‘surprise’ about the lack of information and support about formula milk and associated products. The paucity of information and restricted opportunities to discuss formula feeds with women is reflected within the systematic review undertaken by Laksham et al. (2009)). Women who experienced difficulties said that professionals did not talk about alternatives or offer choices when breastfeeding was not successful. Subsequently, they were left ‘hiding’ their bottles due to fear of disapproval. Also, mothers who decided to bottle feed their infants were often concerned about which products they should purchase:

Bring the choice back for God's sake. When breastfeeding doesn't work bottle feeding is a good alternative. I didn't have a clue what I should be using. (Lorraine)

Mothers indicated that a ‘dogmatic’ approach to breastfeeding and disavowal of any alternatives was not necessarily what they needed. One woman wanted to supplement breastfeeding with a formula feed in order for her cracked nipples to heal. The health professionals advised against this decision in case it interfered with future breastfeeding. The mother considered this advice to not be in her best interests, but this may have reflected her lack of understanding of the importance of effective attachment to the breast as the most important way of preventing sore nipples (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 2003).

Several women did use a range of tools (such as nipple shields, bottles and teats) which are not encouraged by the BFI. However, rather than being perceived to discourage breastfeeding, these aids were considered by some women as essential to help them sustain breastfeeding. On a number of occasions, these products were encouraged and even supplied by health professionals. As promotion of these products is against the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (WHO 1981) and detrimental to the establishment of breastfeeding, the information and advice provided was often covertly relayed. One of the women who had been provided with nipple shields by her midwife reflected upon the clandestine nature of this transaction:

Well the nipples shields, they are not allowed to use them, talk about them or advocate them in any way at all, they made it clear, all of them said the same thing, then eventually one girl said ‘I will be back later on’ and said ‘I have got these (nipple shields) for you’– everything is by the book, because they have got a duty and got to be careful. (Kathy)

Women were often ‘shocked’ that health professionals adhered to rigid policies and were not able to divulge this information. These findings resonate with the ‘breaking the rules’ concept developed by Furber & Thomson (2006) who identified that midwives ‘hide’ practice not congruent with evidence‐based baby feeding policy.

On a number of occasions, while women were aware of the ‘recommended’ guidance about infant feeding, they often made their own decisions to not adhere to the advice provided. For these women, ‘comprehensibility’ was not necessarily about static and orderly processes which should be mechanically and unquestioningly applied. As they considered that ‘no two babies are the same’, a flexible, open and embodied approach was considered to be far more effective rather than a rigid ‘must do’ approach. Others have reported women's agential approach with decisions made based on what worked best for them (Graffy & Taylor 2005; Marshall et al. 2007).

Manageability

Antonovsky defined ‘manageability’ as the extent to which people have the resources ‘at their disposal’ to meet the demands of the stressor (Antonovsky 1987). These resources are either directly under a person's control (such as physical and emotional health) or by resources controlled by legitimate others, namely partners, personal networks and professionals. They incorporate the physiological, psychological and socio‐cultural GRRs which Antonovsky considered essential to successfully cope with life events (Antonovsky 1979, 1987). Therefore, even if a person can comprehend the stressor (i.e. breastfeeding), if they do not possess the necessary internal and external resources to ‘manage’ this experience, their SOC and experience of breastfeeding is likely to be impaired.

In this study it appeared that women's ability or inability to ‘manage’ breastfeeding was influenced by their ‘birth experience’, the ‘manhandling of women's breasts’, the nature and extent of personal support a woman has at her disposal to manage infant feeding, and the ‘benefits and barriers of peer support’.

The birth experience

Most of the women who had not sustained breastfeeding or who had difficulties initiating breastfeeding (n = 7) had not had a vaginal birth. Difficulties associated with medicalized and operative births and breastfeeding initiation have been highlighted in the literature (Chang & Heaman 2005). Five of the women in this study spoke of the ‘difficult’, ‘traumatic’ and ‘disappointing’ childbirth experience they had endured.

The majority of women who experienced medical interventions/complications during the birth did not have skin‐to skin‐contact with their infants in the immediate post‐natal period. Some of these women felt ‘cheated’ and ‘robbed’ by not experiencing the period of unhurried skin‐to‐skin contact they had been offered antenatally. Furthermore, a small number of women who had experienced skin‐to‐skin contact following a medicalized birth were often too ‘out of it’ to remember or enjoy the experience.

This was of particular relevance when the value of skin‐to‐skin contact in ‘managing’ to initiate and continue breastfeeding was evident in a number of the women's stories:

She was put on my chest immediately and she suckled there and then. I believe from reading all the books that that is the best thing to do because it helps, and it has – it's been an absolute breeze. (Susan)

‘Manhandling’ of women's breasts

A woman's self‐efficacy (confidence) to breastfeed also appeared to be influenced by the ‘manhandling’ of her breasts. A number of women recounted distressing experiences of babies being ‘forced’ onto their breasts by the health professionals:

It was very much, I had hold of X and she (midwife) came to the bedside and got hold of X (son) round the back of the neck, and had hold of my breast and was trying to force the two together if you will. I don't know whether it's because she had a forceps delivery, she was quite tender on her head, she wasn't comfortable with it at all. They kept trying, trying, trying. (Katrina)

While women were not happy with these procedures, they often felt powerless to complain due to health professionals being perceived as the ‘expert’.

This invasion of women's ‘spatial boundaries’ has been reported by others (Dykes 2005a; Schmied et al. 2009). In this study, the invasive ‘mauling’ of the women's bodies impacted upon their willingness to seek out future support, thereby preventing these women from acquiring the necessary resources to ‘manage’ breastfeeding. These mothers were concerned that it would be another ‘unknown’ professional touching their intimate body parts. Their personal memories of this experience were considered embarrassing, intrusive and for some, deeply upsetting:

They say they have groups, people can come round and show you, but it's a stranger in your home you don't know, grabbing your breasts, trying to shape them in a certain way to get it into your baby's mouth' (Is that the experience you have had?) Yes that is the experience I had in hospital and at home. It's bloody awful, really embarrassing, I could actually cry (starting to cry). (Annie)

Personal support systems

The emotional and practical support received from external resources such as partners as well as family members and friends played an important influence on the ‘manageability’ of breastfeeding (Hoddinott et al. 2000). Almost all of the women interviewed felt that their partners had supported their infant feeding choices despite the fact that some partners were disappointed or felt frustrated at the lack of comfort they could provide to their children:

I think he almost wanted to give me a break sometimes, and I think he found it a bit distressing that he could not calm her. (Louise)

One of the mothers stated that while her partner had ‘pushed’ her into introducing formula feeds as he wanted to ‘bond with his daughter’ a ‘satisfactory’ compromise was made for mixed feeding (breastfeeding during the day and formula milk at night‐time). Support from this external source was therefore determined through a combination of persuasion and negotiation.

The most positive information and support was provided by friends and family who had breastfed their own children. Negative attitudes were generally expressed by those who had not experienced breastfeeding. The unhelpful messages and advice often seemed to justify and excuse their own personal choices whilst undermining woman's decisions.

My father and my step mother would say ‘I don't know why you are bothering, you put yourself through all this for nothing, just get her on a bottle, she is not happy and you're not happy’ and it was constant. (Kathy)

Negative comments did not necessarily deter women from continuing to breastfeed, but with regard to women's SOC, they contributed to an emotionally draining experience, which threatened their ‘comprehensibility’, sense of well‐being and potentially their ‘manageability’ to breastfeed.

The value of time and accessibility of support

A recurrent theme within the women's stories was the value of time to provide them with the support they needed to succeed at breastfeeding. A divergent picture was presented in that there was a marked lack of time to support women on the post‐natal wards; whereas ample time was available to provide care and support once the women went home. The time constraints on midwives in hospital are reported by others (Dykes 2005a; Schmied et al. 2009).

A number of the mothers made reference to buzzing for assistance – but nobody came:

X (health professional) said when she wakes up, buzz me, I buzzed for two hours and nobody came.(Lorraine)

Lorraine ceased breastfeeding when she was discharged home at 3 days post‐delivery.

As reported by Dykes (2005a) the participants noted how ‘busy’, ‘overworked’ and ‘stressed’ the midwives were, and this often deterred them from seeking support. This presented a paradox in that, while women were being encouraged to stay in hospital to establish breastfeeding, they were not being provided with, or felt unable to access the necessary support for this to be achieved. The lack of available support was also magnified for those who were physically restricted due to a complicated birth.

A different picture emerged once women had returned home, with most emphasizing the time they were afforded during the postnatal period; whether this was provided by the community midwife, health visitor, health care assistant, breastfeeding volunteer or help‐line. The accessibility and availability of this support was repeatedly emphasized, with women being provided with an array of options through which help and support could be obtained. These options included printed information, contact details of professionals, helpline numbers as well as details of support groups.

I can't complain really, because the support I have had – I've always had a phone number and the Breastfeeding Network number that I was given is pretty much 24 hours. You can ring at any point. (Teresa)

The passion and commitment demonstrated by pro‐breastfeeding professionals and lay supporters was often over and above the women's expectations:

Those that are involved in the Breastfeeding Network are very passionate about it and are more than willing to go out of their way to help you as much as possible in any way that they can. (Annie)

Positive feedback to the postnatal support was perhaps understandably more often provided by women who had managed to successfully breastfeed, compared to those who had not. A number of these women spoke of how professionals would time the support to coincide with the feeds, thereby providing the support exactly when it was needed. Furthermore, these participants actively recognized that the extent of care received was determined by their method of infant feeding:

The midwives were wonderful afterwards . . . brilliant, totally pro‐breastfeeding . . . I am sure if I hadn't have been breastfeeding, that they wouldn't have come as often as they did. (Kathy)

Benefits and barriers to peer support

Almost all the women who had sustained breastfeeding over a period of time had accessed breastfeeding peer support groups in the postnatal period. These support networks were considered to be invaluable. Informational, social and emotional benefits were highlighted in terms of being with ‘like‐minded people’, making friends and social networks, as well as providing women with the positive reinforcement, confidence and encouragement to sustain breastfeeding. These findings are supported by previous research (Britton et al. 2007; Schmied et al. 2009).

In relation to the barriers to accessing peer support, the mother who had been unable to conventionally breastfeed (exclusive pumper) did not want to access this support in case she was made to feel like she had not persevered, or was offered unwanted advice:

I didn't fit into that category in its truest form of breastfeeding. Certainly didn't want women who are fanatical about it, giving me lectures. (Annie)

Other barriers related to mother's unwillingness to make potential admissions of ‘not coping’ or attending a group on their own.

These barriers demonstrate how an unpredictable scenario of providing infants with breast milk, fear of personal admission or lack of confidence has a direct influence on the external and internal resources at the women's disposal.

Meaningfulness

The third underpinning concept of the SOC is ‘meaningfulness’. According to Antonovsky, this is the extent to which life makes sense emotionally; that the demands presented are worthy of emotional investment. Coping with the life challenge is thereby viewed as a desirable action (Antonovsky 1993). ‘Meaningfulness’ was perceived to be the motivational element of the SOC (Antonovsky 1987). It provided people with care, concern and the ‘importance of being involved’ in the life challenge (Antonovsky 1987, p. 18).

From an infant feeding perspective, the ‘meaningfulness’ of the event was influenced by how infant feeding messages were delivered: how the discrepancies between theoretical and embodied knowledge altered women's perceptions of breastfeeding; the myths, media images; and difficulties associated with public breastfeeding and the emotionality of infant feeding.

Encouraging and not dissuading

There did appear to be an important balance in terms of how professionals engaged with women and how they delivered infant feeding messages in terms of whether they encouraged or dissuaded a woman to maintain breastfeeding.

The value and importance of emotional support in terms of the affirmation and reassurance it provides is widely reported in the literature (McInnes & Chambers 2008; Schmied et al. 2009). In this study, a selection of mothers considered that reassurance, encouragement and re‐enforcement of the benefits and value of breastfeeding were essential. These messages were beneficial to re‐emphasize and promote the ‘meaningfulness’ of breastfeeding and to enhance the mother's willingness and confidence to persevere:

Well if it wasn't for the health professionals I don't think I would have carried on as long because they kept pushing me and pushing me and telling me I am doing the right thing. Every time I have got to the point where I am feeling like I am going to stop they have reassured me and I have carried on. (Gail).

On the other hand a number of the women in this study described feeling ‘pressured’ to breastfeed, as reported by Schmied et al. (2009). These women considered the need for professionals to present a balanced perspective of the pros and cons of infant feeding. An over‐enthusiastic breastfeeding advocate made some women feel pressured which first‐time mothers, in particular, felt ill‐equipped to cope with:

I think there was too much emphasis on breastfeeding. The tone of it needs to be different, the way it's done needs to be different, more sensitivity around it definitely. You have all this pressure and you don't need it. (Teresa)

Theoretical vs. embodied knowledge

Most mothers referred to discrepancies between their theoretical expectations and the embodied reality of infant feeding. These insights have also been reported by others (Dykes 2005b; Marshall et al. 2007; Schmied et al. 2009). A number of the women had anticipated breastfeeding to be a pain‐free, straightforward and natural experience. However, the reality of breastfeeding was ‘tying’, ‘difficult’, ‘painful’ and required women and babies to ‘learn together’:

I didn't think twice about whether I was going to or not, I thought it's the most natural thing, and I am aware of formula exists and stuff, but I thought I don't want to do that. I was going to breastfed and that was it. In my ignorance I didn't think it would be as hard as it was. (Chris)

For two of the mothers, it was the ‘unnatural’ nature of their experience that contributed to their decision to stop breastfeeding. From a SOC perspective, it appeared that when women's priori assumptions of breastfeeding were not fulfilled, this influenced their ‘comprehensibility’, the personal resources to continue breastfeeding, as well as their ‘meaningfulness’ of infant feeding:

AllI ever heard was it's the most natural thing in the world to do, and I thought it was the most unnatural thing. I found it so stressful and once she was on the whole time I was just ‘oh my God’. (Lorraine)

Media messages and public breastfeeding

Most women in this study made reference to negative media images and information about breastfeeding, as reported by Henderson et al. (2000), which impinged upon the ‘meaningfulness’ of breastfeeding:

Well if there is anything in the media about breastfeeding it is negative. You know somebody has fed somewhere and somebody has said something, or asked them to leave. It's the negative things that are printed, and it's the negative things that I remember. (Katrina)

Most of the participants expressed personal difficulties in feeding in front of other people, as widely reported (Dykes 2003). These difficulties tended to be expressed towards ‘strangers’, though for some this difficulty also extended to their close personal networks. One of the main deterrents of public breastfeeding was the fear of possible retribution. This belief was often strongly associated with the socio‐cultural perception of breasts as sexual objects (Henderson et al. 2000). According to Antonovsky, one of the key facets of achieving ‘meaningfulness’ is the social validation of the event (Antonovsky 1979). The lack of social validation implied by their concern not to ‘offend’ members of the public was a powerful deterrent.

Emotionality of infant feeding

Women's decision to breastfeed was generally related to the health benefits for the infant rather than for personal reasons, as reported by others (Dykes 2005b; Marshall et al. 2007). The mothers highlighted a desire to ‘protect’ their infants from health related illnesses such as asthma, colic and eczema, and to give them the ‘best start’ in life. Socio‐emotional benefits such as bonding and attachment also operated as a significant influence in a woman's decision to breastfeed, whereas the ‘convenience’ and ‘ease’ of breastfeeding were often expressed as secondary issues.

There were a number of emotions attached to breastfeeding. Those who had managed to breastfeed spoke of ‘love’, ‘pride’ and ‘determination’. As some of the women had had complicated births, the ability to breastfeed was associated with compensatory qualities as it was something positive they could be in control of, and ‘do properly’:

If I had not been able to carry him full term, at least I can do this for him and give him the best start I can from now on. (Emma)

Similar findings were reported by Flacking et al. (2006) with regard to mothers of pre‐term infants.

In his later theorizing, Antonovsky recognized the primary importance of the concept of ‘meaningfulness’. He considered that it is only when coping is viewed as desirable that ‘comprehensibility’ and ‘manageability’ is likely to improve. This view was supported by the findings from this study. Personal values appeared to be one of the key motivators for women to succeed at breastfeeding. It was not necessarily the case that women who successfully breastfed had not suffered from any problems, or were those who had experienced fewer difficulties compared with those who moved on to bottle feeding. Several of the breastfeeding women had experienced mastitis, engorgement, infections and difficulties with lactation:

I said to my husband if anyone ever asks me what my greatest achievement is, this is it, never mind getting a degree or anything like that, this is my greatest achievement, feeding my baby through all that shit. It was so important for me to do. (Kathy)

Antonovsky also stressed that goal attainment is contingent on investment of effort and energy (Antonovsky 1987). He believed that there needed to be an ‘underload – overload’ balance. A strong SOC was not necessarily related to everything being easy and requiring no effort; rather he considered that a state of tension could also be linked to valuable benefits in terms of the sense of achievement and direction of effort warranted to achieve the intended goal. For the mothers in the study who managed to successfully breastfeed despite their endured adversity, what appeared essential was the commitment and perseverance to fulfil their desire to breastfeed their infants.

The women who had been less successful at breastfeeding (discontinued within the early post‐natal period) expressed ‘guilt’ and remorse. One of the mothers retrospectively considered that she ‘had not tried hard enough’, and this sense of culpability continued for a long time after formula feeds had been introduced. Blame was attributed to the potential impact on attachment relationships (‘I don't feel that closeness with my baby’), de‐valuing of the maternal role (‘anyone can feed him now’), and the knowledge of the health benefits of breastfeeding:

I start thinking ‘touch wood’ she's not a sickly baby because you think if she's gonna be a sickly baby I'm not gonna blame myself, but think to myself if I'd have breastfed her, I'd never have any of this. (Lorraine)

These negative emotions attached to unsuccessful breastfeeding have been reported in previous studies (Laksham et al. 2009). From a SOC perspective they also illuminate the significance of ‘meaningfulness’ not being fulfilled. Antonovsky considered guilt to be one of the most debilitating and negative of our emotions (1993). For one of the women in the current study, her sense of failure and guilt due to her inability to breastfeed was associated with her subsequent postnatal depression.

Discussion

This paper has provided a theoretical interpretation of women's experiences of infant experiences using the three underpinning constructs of Aaron Antonovsky's SOC theory. This theoretical lens has generated important insights into how women's experiences of infant feeding are influenced by the ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’ of this life event.

The limitations of this study are that it was conducted with a small cohort of women from one geographical area and, as all of the women in this study had initiated breastfeeding, the sample is less reflective of groups who are least likely to breastfeed, such as lower socioeconomic occupational groups.

As Antonovsky's SOC theory reflects a global orientation to life, it may be that the women who persevered and sustained breastfeeding were those who held a strong SOC in terms of developing and employing cognitive, affective and instrumental strategies which were likely to facilitate coping (Antonovsky 1979). Whereas those with a weak SOC may have focused on the burdensome aspects of breastfeeding, felt overwhelmed, and given up before any sense could be made of their experience (Antonovsky 1979, p. 139). Future research could introduce the SOC's quantitative based scale to assess and measure how the SOC is associated with infant feeding choices and experiences.

Overall, these insights reflect, as highlighted by 1979, 1987), that women's SOC of infant feeding is affected by their personal, social and cultural factors. The BFI and associated policies and guidance to improve breastfeeding and infant feeding options does address some of the issues concerning the predictability of information and support. However, there is little or no consideration of the wider socio‐cultural influences which affect all the underpinning SOC constructs. Careful deliberation of the issues, through adopting a SOC perspective, is paramount if women's infant feeding experiences and, in particular, the promotion of breastfeeding is to be achieved. The utility of the SOC to uncover these issues together with practice based recommendations have been outlined as follows:

Comprehensibility

In this study, women's ‘comprehensibility’ of infant feeding was influenced by the predictability of information, support and guidance they received, which in turn affected the choices that they make. Formula/bottle feeding and its associated paraphernalia are deeply culturally embedded in the UK. The fact that professionals either did not, or were restricted in their choices to, divulge information about these products challenged women's ‘comprehensibility’ of infant feeding within their cultural context. Whilst it is appreciated that women's infant feeding decisions should not be undermined, their opportunities to make ‘cognitive sense’ of these issues are paramount.

From a BFI perspective, the mandatory elements of this award identifies that all professionals should attend a comprehensive breastfeeding course with the aim that women will receive consistent information and support. Consistent information from professionals may also, over time, help to combat the ‘noise’ that operates fluidly and pervasively in women's socio‐cultural networks. Local evaluations to uncover these socio‐cultural norms together with structured dissemination methods (such as via workshop events) may well help professionals to appreciate and develop skills to address these factors.

The BFI stipulates that formula feeding should not be discussed antenatally (in group settings only), but encourages postnatal information being given once the mother has decided to bottle feed (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 2003). In this study all the women were breastfeeding at the time of discharge from the post‐natal wards. The five women who introduced formula milk did not receive any bottle feeding information prior to initiation of this practice. The BFI criteria also instructs that dummies and teats are not to be recommended by professionals to breastfed babies (with nipple shields only recommended in extreme and ‘rare’ circumstances). These recommendations are established via evidence‐based associations with reduced milk supply, attachment difficulties and interference with demand feeding (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 2003).

In this study, some professionals did make covert recommendations for non‐breastfeeding options/products; supporting the ‘breaking the rules’ concept (Furber & Thomson 2006). From a contemporary socio‐cultural viewpoint, these tools and products are widely promoted (via personal networks), available and utilized. Findings from this study revealed that a number of women introduced these options, irrespective of the professional advice provided. Their introduction often mirrored the clandestine nature adopted by professionals, with women keeping these practices ‘hidden away’ from professionals for fear of criticism or disapproval. The fact that these aids were often utilized to sustain successful breastfeeding is however an important consideration.

To some extent these findings suggest health professionals have misinterpreted the BFI guidance. The BFI standards do not restrict discussions on formula feeding once a post‐natal woman has made her decision. Recommendations for nipple shields may also be made in extreme circumstances, as long as the potential difficulties and appropriate usage have been clearly imparted (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 2003). The varied and embedded attitudes and values (from a service‐user as well as professional perspective) towards infant feeding appears to have created an artificial situation in which professionals, women and evidence‐based decisions have become alienated from one another. The danger in professionals not openly discussing the range of options may result in inappropriate usage of products and subsequent discontinuation of breastfeeding.

This dilemma directs us to the need to embrace the ‘evidence based medicine’ approach as defined and discussed by Sackett et al. (1996). This is an approach that integrates the best current evidence, clinical expertise and consideration of the patient's context, circumstances, rights and preferences. In practice this would involve the education and support for professionals to offer ‘real choice’ to women, based on the best available research and tailored to the women's specific needs. Opportunities for professional and service‐user infant feeding discussions (during antenatal/early post‐natal period) based on this approach should be considered.

Manageability

In relation to the ‘manageability’ of infant feeding, women's ability to ‘manage’ breastfeeding was influenced by the nature and emotional response to the birth experience and the opportunities for skin‐to‐skin contact in the immediate post‐natal period. From a practice‐based perspective, professionals need to be cognizant of the difficulties that women can experience following a difficult birth, as well as prepare women for potential problems in initiating breastfeeding. The BFI standards actively promote consultations with women on their choices of pain‐relief, and advocate prolonged periods of skin‐to‐skin contact in the immediate postnatal period. As more and more hospitals and community health facilities adopt the BFI standards, it is anticipated that these practices will be enhanced.

A further important influence on the ‘manageability’ of infant feeding was the invasion of women's spatial boundaries. ‘Insensitive and invasive’ touch (Schmied et al. 2009) induced significant distress and created personal barriers for women to develop resources to manage breastfeeding. This is not to suggest that ‘touch’ cannot be sensitive or helpful for successful attachment (Schmied et al. 2009), however health professionals need to respect women's personal boundaries in a perceptive and, if necessary, ‘hands‐off’ manner. These issues need to become an integral component of the BFI training modules; to raise awareness and promote positive practice.

The important impact of external resources (provided by family, friends and social networks) on women's infant feeding preferences (Hoddinott et al. 2000; Dykes 2003) is not directly addressed within the BFI standards. Attempts to improve breastfeeding practices and options via support from external sources needs to be an integral and simultaneous consideration of the implementation of the BFI award. Recommendations could include: targeted breastfeeding social marketing campaigns; active and targeted inclusion of personal networks in antenatal education classes; and inclusion of infant feeding issues within the secondary school curriculum.

A crucial deterrent to successful breastfeeding was the lack of ‘time’ and support women were afforded on the postnatal wards. Whilst the mothers frequently cited the breadth of community support options available to them, restricted help and support in the immediate postnatal period often determined their infant feeding choices. The BFI provides training, policy and guidance on how to promote, protect and support breastfeeding. However, without sufficient breastfeeding resources to support women, breastfeeding rates are unlikely to improve.

Meaningfulness

The final construct of the SOC is ‘meaningfulness’– the extent to which life events make sense emotionally. In this study, ‘meaningfulness’ was influenced by how infant feeding messages were delivered. Whilst positive reinforcement and reassurance were essential to encourage women, there was a need to prevent women feeling pressurized and guilty when breastfeeding was not successful or sustained. Schmied et al. (2009) emphasize that professionals should demonstrate authentic presence through empathy, encouragement and affirmation. The findings from this study suggest that this approach should be extended to all mothers; whether they feed their babies by breast or with formula milk. The links between bottle feeding and depression are reported in the literature (Gallup et al. 2009). Health professionals therefore, need to be cognizant of the implications of this association for mothers, infants and their families. Additional learning modules to equip professionals with the skills/abilities to promote positive well‐being, irrespective of infant feeding preferences and decisions, should be contemplated.

The dominance of a bottle feeding culture, negative media images and fear of lack of social validation all influenced the ‘meaningfulness’ of breastfeeding in terms of how, where and when women fed their infants (see also Dykes 2003). A key practice based implication to address these issues is the promotion of social learning opportunities to help normalize and validate breastfeeding. This could be achieved through the development of ‘breastfeeding friendly premises’ to promote public breastfeeding; and for breastfeeding women to interact with antenatal women. In this study, the degree of divergence between the women's theoretical and embodied experiences influenced the meanings and decisions associated with infant feeding. The inclusion of breastfeeding mothers at antenatal groups/classes could enable more realistic and personal experiences of breastfeeding to be divulged. The SOC theory identifies that it is the ‘meaningfulness’ of the event that will determine the person's comprehension as well as their willingness to invest resources to succeed. As the meaning of breastfeeding provides the drive and motivation for women to continue, efforts need to promote the benefits as well as challenges of breastfeeding so that a more ‘predictable’ and ‘manageable’ experience can be achieved.

Conclusion

The SOC theory has provided unique insights into how women's experiences of infant feeding are influenced by the ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’ of this life event. Application of this knowledge and understanding can support practitioners in addressing the wider socio‐cultural pressures which impact upon women's ways of negotiating infant feeding within a specific cultural context. Application of this knowledge by health care staff when implementing the BFI will help and support women to negotiate infant feeding in ways that integrate with their personal situation and circumstances.

Source of funding

This project was funded by a Primary Care Trust in North‐West England, specific details not provided to maintain confidentiality.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the women who took part in this study, as well as Professor Andy Bilson for his contributions.

This article was published online on 27 MAY 2010. The author's name Lakshman R. was initially spelled incorrectly and has now been fixed throughout the article [18 September 2014].

References

- Antonovsky A. ( 1979. ) Health, Stress and Coping . Jossey‐Bass Publishers; : San Francisco . [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. ( 1987. ) Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well . Jossey‐Bass Publishers; : San Francisco . [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky H. & Sagy S. ( 2001. ) The development of a sense of coherence and its impact on responses to stress situations . Journal of Social Psychology 126 , 213 – 225 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attride‐Sterling J. ( 2001. ) Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research . Qualitative Research 1 , 385 – 405 . [Google Scholar]

- Britton C. , McCormick F.M. , Renfrew M.J. , Wade A. & King S.E. ( 2007. ) Support for breastfeeding mothers . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001141. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chang Z.M. & Heaman M.I. ( 2005. ) Epidural analgesia during labor and delivery: effects on the initiation and continuation of effective breastfeeding . Journal of Human Lactation 21 , 305 – 314 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F. ( 2003. ) Infant Feeding Initiative: A Report Evaluating the Breastfeeding Practice Projects 1999–2002 . Department of Health; : London . [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F. ( 2005a. ) Critical ethnographic study of encounters between midwives and breastfeeding women on postnatal wards . Midwifery 21 , 241 – 252 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F. ( 2005b. ) ‘Supply’ and ‘demand’: breastfeeding as labour . Social Science & Medicine 60 , 2283 – 2293 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhard I.M. , Van den Hout M. & Vlaeyen J.W.S. ( 2003. ) The sense of coherence in early pregnancy and crisis support and posttraumatic stress after pregnancy loss: a prospective study . Behavioural Medicine 29 , 80 – 84 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M. & Lindström B. ( 2005. ) Validity of Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale: a systematic review . Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59 , 460 – 466 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R. , Ewald U. , Nyqvist K.H. & Starrin B. ( 2006. ) Trustful bonds: a key to ‘becoming a mother’ and to reciprocal breastfeeding. Stories of mothers of very preterm infants at a neonatal unit . Social Science and Medicine 62 , 70 – 80 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber C.M. & Thomson A.M. ( 2006. ) ‘Breaking the rules’ in baby‐feeding practices in the UK: deviance and good practice? Midwifery 22 , 365 – 376 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup G.G. , Pipitone R.N. , Carrone K.J. & Leadholm K.L. ( 2009. ) Bottle feeding simulates child loss: postpartum depression and evolutionary medicine . Medical Hypotheses 74 , 174 – 176 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffy J. & Taylor J. ( 2005. ) What information, advice, and support do women want with breastfeeding? Birth 32 , 179 – 186 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L. , Kitzinger J. & Green J. ( 2000. ) Representing infant feeding: content analysis of British media portrayals of bottle feeding and breast feeding . British Medical Journal 321 , 1196 – 1198 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildingsson I. , Tingvall M. & Rubertsson C. ( 2008. ) Partner support in the childbearing period – a follow up study . Women and Birth 21 , 141 – 148 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P. , Pill R. & Hood K. ( 2000. ) Identifying which women will stop breast feeding before three months in primary care: a pragmatic study . British Journal of General Practice 50 , 888 – 891 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laksham R. , Ogilvie D. & Ong K.K. ( 2009. ) Mother's experiences of bottle‐feeding: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies . Archives of Disease & Medicine 94 , 596 – 801 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J.S. , Hall E.O.C. & Aagaard H. ( 2008. ) Shattered expectations: when mothers' confidence in breastfeeding is undermined – a metasynthesis . Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 22 , 653 – 661 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.L. , Godfrey M. & Renfrew M.J. ( 2007. ) Being a ‘good mother’: managing breastfeeding and merging identities . Social Science & Medicine 65 , 2147 – 2159 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes R.J. & Chambers J.A. ( 2008. ) Supporting breastfeeding mothers: qualitative synthesis . Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 , 407 – 427 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A.M. ( 2006. ) A metasynthesis of qualitative breastfeeding studies . Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health 51 , 13 – 20 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz Y. , Sarid O. , Peleg R. & Sheiner E. ( 2009. ) Sense of coherence predicts uncomplicated delivery: a prospective observational study . Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 30 , 29 – 33 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D.L. , Rosenberg W.M.C. , Gray J.A.M. , Haynes R.B. & Richardson W.S. ( 1996. ) Evidence‐based medicine: what it is and what it isn't . British Medical Journal 13 , 71 – 72 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmied V. , Beake S. , Sheehan A. , McCourt C. & Dykes F. ( 2009. ) A meta‐synthesis of women's perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support . JBI Library of Systematic Reviews 7 , 583 – 614 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative ( 2003. ) Implementing the Baby Friendly: Best Practice Standards . UNICEF; : London . [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation ( 1981. ) International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes . WHO; : Geneva . [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation ( 2003. ) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding . WHO; : Geneva . [Google Scholar]