Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore from the Middle‐Eastern mothers’ perspective, the experience of breastfeeding and their perceptions of attributes of the health care system, community and society on their feeding decisions after migration to Canada. New immigrant mothers from the Middle East (n = 22) were recruited from community agencies in Edmonton, Canada. Qualitative data were collected through four focus groups using an ethnographic approach to guide concurrent data collection and analysis. Survey data were collected on socio‐demographic characteristics via pre‐tested questionnaires. All mothers, but one who was medically exempt, breastfed their infants from birth and intended to continue for at least 2 years. Through constant comparison of data, five layers of influence emerged which described mothers’ process of decision making: culture/society, community, health care system, family/friends and mother–infant dyad. Religious belief was an umbrella theme that was woven throughout all discussions and it was the strongest determining factor for choosing to breastfeed. However, cultural practices promoted pre‐lacteal feeding and hence, jeopardising breastfeeding exclusivity. Although contradicted in Islamic tradition, most mothers practised fasting during breastfeeding because of misbeliefs about interpretations regarding these rules. Despite high rates of breastfeeding, there is a concern of lack of breastfeeding exclusivity among Middle‐Eastern settlers in Canada. To promote successful breastfeeding in Muslim migrant communities, interventions must occur at different levels of influence and should consider religious beliefs to ensure cultural acceptability. Practitioners may support exclusive breastfeeding through cultural competency, and respectfully acknowledging Islamic beliefs and cultural practices.

Keywords: breastfeeding, ethnography, immigrant, refugee, Canada

‘… Mothers should give suck to their children for two whole years, for those parents who desire to complete the term.’ Verse 2:233, Qur'an

Introduction

Adequate nutrition from birth to 2 years of age is a critical window for promotion of health, growth and behavioural development (Dewey 2004). Breast milk is well recognised as the best form of infant nutrition, which is associated with better cognitive development and lowers the risk of infections, allergy, obesity, gastroenteritis and sudden infant death (Dewey 2004; Ip et al. 2007). Similarly, breastfeeding mothers also benefit from quicker post‐delivery recovery and weight loss, improved child spacing because of lactational amenorrhoea, and enhanced maternal–infant bonding (Kramer & Kakuma 2004). In spite of numerous benefits of breastfeeding, 1.4 million children under five die annually from being deprived of or receiving insufficient amounts of breast milk (Black et al. 2008).

Unlike breastfeeding initiation rates, exclusive breastfeeding rates for the first 6 months have shown little or no improvement over the past few decades in Canada. Despite the high prevalence of breastfeeding initiation (87.9%), the rates of ‘any breastfeeding’ and ‘exclusive breastfeeding’ for 6 months post‐partum have been reported at 51% and 16.4%, respectively (Statistics Canada 2011). Breastfeeding is a complex behaviour, constructed and practised within the social living environment of a woman, and therefore, variations exist in breastfeeding rates among different socioeconomic and cultural groups (Celi et al. 2005) while lower rates being reported among multi‐ethnic groups (Meedya et al. 2010). However, Middle‐Eastern immigrants have shown the greatest rates of breastfeeding compared with women from other ethnic groups and those from the host country (Ghaemi‐Ahmadi 1992; Homer et al. 2002; Dahlen & Homer 2010). This finding may highlight the role of strong mediating factors that are mutually shared by Middle‐Eastern mothers and may be independent of acculturation to the local practices of the host country.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have evaluated the cultural beliefs of new‐settler Middle‐Eastern mothers regarding infant feeding from an emic perspective, which is the perspective of the participants. Emic constructs are descriptions and accounts regarded as meaningful by the native members of the culture whose behaviours are being studied (Lett 1990). This is important in the Canadian context where the Middle‐Eastern population (West Asians and Arabs) constitutes the fastest growing group to influx Canada (Statistics Canada 2005). The aim of the present study was to explore the beliefs, values and experiences that shape breastfeeding practices of Middle‐Eastern mothers residing in a city in Western Canada. Providing this contextually detailed description of infant feeding will provide insights into ways health care providers may support breastfeeding practices of mothers who have immigrated to Canada from the Middle East.

Key messages

Interventions to promote breastfeeding must occur at different levels of influence and should consider religious and cultural beliefs and socioeconomic status in order to be successful.

Media campaigns are recommended to target Middle‐Eastern families focusing on the importance of breastfeeding exclusivity and timely introduction of complementary foods.

Health care professionals need continuing education that provides common messaging to avoid inconsistencies.

Methods

Research design

An ethnographic approach guided the concurrent data collection and analysis to investigate the cultural background of infant feeding among Middle‐Eastern mothers (Schmoll 1987). Ethnography is a research design that facilitates the study of ways implicit beliefs and values shape behaviour (Holloway & Wheeler 2002). As noted by Field & Morse (1985), the knowledge gained in this approach is emic in nature, which conforms to our objective of understanding mothers’ experiences of infant feeding from their own points of view.

Sampling

Protocols of this study were approved by the Women and Children's Health Research Institute (WCHRI) and Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta, Canada. Mothers were recruited from community agencies in the Edmonton area (AB, Canada) via flyers and word of mouth. Individuals who were interested in participating were asked to either contact researchers directly or provide their contact information to their community leaders at the participating community agencies. A member of the research team then met with those who expressed interest and who met eligibility criteria, answered any questions, and obtained written consent provided in their own native languages. Because the provision of informed consent was new to most mothers and some were illiterate, the focus group (FG) facilitator read the consent form to interested individuals and addressed questions before consent forms were signed. To ensure good attendance, transportation was arranged for those who needed it. Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card to a local retail store at the conclusion of each session and snacks were provided in the tradition of Middle‐Eastern society (Winslow et al. 2002).

In total, 22 Middle‐Eastern mothers (6 Iranian, 16 Arab) participated in the present study and met the following eligibility criteria: being over 18 years of age, being born and raised in the Middle East, being healthy (absence of health conditions that contraindicated breastfeeding), and having a healthy infant(s) less than 1 year of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the Middle‐Eastern mothers in an ethnographic study in Edmonton, AB, Canada*

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age † , years | 25.5 (10.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 21 (95.5) |

| Widowed | 1 (4.5) |

| Education level | |

| Illiterate | 1 (4.5) |

| <High school degree | 1 (4.5) |

| Completed high school degree | 15 (68.2) |

| Some college or university ‡ | 3 (13.6) |

| Completed college or university degree | 2 (9.1) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed for wages | 2 (9.1) |

| Self‐employed | 5 (22.7) |

| Unemployed | 15 (68.2) |

| Ethnicity (birthplace) | |

| Iran | 6 (27.3) |

| Iraq | 4 (18.2) |

| Kuwait | 6 (27.3) |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 (27.3) |

| Religion § | |

| Islam | 22 (100.0) |

| Length of residency in Canada (year) | |

| <1 | 1 (4.5) |

| 1–3 | 12 (54.5) |

| 4–5 | 5 (22.7) |

| >5 | 4 (18.2) |

| Annual household income, CAD | |

| <20 000 | 7 (31.8) |

| 20 000–39 000 | 12 (54.5) |

| 40 000–69 000 | 2 (9.1) |

| 70 000–99 000 | 1 (4.5) |

| Smoking/recreational street drug abuse | 0 (0.0) |

| Alcohol consumption | 0 (0.0) |

| Parity † , n | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Gestational age † , weeks | 39.0 (1.0) |

| Chronic disease history | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2 (9.1) |

| Diabetes | 2 (9.1) |

| Goiter | 2 (9.1) |

| None | 16 (72.7) |

| Planned pregnancy | |

| Yes | 14 (63.6) |

| No | 8 (36.4) |

| Body mass index † , kg m−2 | 27.3 (7.4) |

| Partner's education | |

| Some high school (grades 10–11) | 1 (4.5) |

| Completed high school degree | 3 (13.6) |

| Some trade, technical, vocational school or business/community college | 7 (31.8) |

| Completed trade, technical, vocational school or business/community college | 6 (27.3) |

| Completed university undergraduate degree | 3 (13.6) |

| Completed university postgraduate degree | 2 (9.1) |

| Partner's employment | |

| Employed for wages | 14 (63.6) |

| Self‐employed | 7 (31.8) |

| Unemployed | 1 (4.5) |

*Values are n (%), unless otherwise noted. †Median (interquartile range). ‡Have some post‐secondary education, but not completed. §Although participants were not asked about their religion, when asked of their ethnicity, all women indicated that they followed Islam.

CAD, Canadian dollars.

The Persian Gulf countries have undergone rapid economic and social changes during the past two decades and have similar cultural, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics as well as common health beliefs and problems (Musaiger 1996). Because ‘ethnic group’ lacks an objective definition, researchers are required to construct their own definition of ethnicity (Oppenheimer 2001), and therefore, we defined ‘Middle‐Eastern’ people as those born and raised in one of the countries located in the Persian Gulf region (i.e. Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia). This corresponds with Statistics Canada's definition of ethnicity, which is based on the ‘birthplace’, rather than language or religion, for categorising immigrant groups (Statistics Canada 2010). Except for Iranians who speak Farsi, the official language of other Middle‐Eastern countries is Arabic, and the vast majority of people in these countries follow the Islamic religion (from 70% in Lebanon to 100% in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia) (Kittler & Sucher 2007).

Data collection and analysis

FG discussions

Data were collected using FGs because this strategy provides access to participants’ ideas in their own language and accesses their real‐world experiences on topics where data are limited (Tiggemann et al. 2000). FGs are useful among those with limited power and influence, such as ethnic minority women with lower literacy levels (Barbour 1999), which might be due to the fact that they are less threatening than an individual interview with a member of the research team. FGs were particularly suited for this study because they align well with the strong oral tradition in Arabic culture (Winslow et al. 2002). In addition, FGs address interactions among participants and provide an opportunity to explore the construction and co‐construction of meaning (Morgan 1997).

According to Krueger & Casey (2000), three FGs are generally sufficient to gain topic saturation; however, we left the option open to conduct additional FGs until no new issues emerged. We conducted four FGs each including four to six participants, because smaller FGs yield development of more in‐depth ideas (Reed & Payton 1997). In addition, previous studies conducted among Middle‐Eastern populations have shown that the voluble oral tradition of Arab women often results in participants holding side conversations and talking at the same time during FGs, which lead to losing part of the data during larger FGs (Winslow et al. 2002). Each session lasted 1 h 15 min–1 h 45 min and ended by mutual agreement between participants and facilitator that the topics were adequately addressed.

Our FGs took place at a time that did not interfere with Muslims’ five daily prayers. Because none of the mothers were fluent in English, FGs were conducted and analysed in the mothers’ respective languages (3 Arabic and 1 Farsi FGs) to maximise the quality (Twinn 1998). The principal investigator (M.J.) and the FG facilitator were both from the same ethnic background as the participants and were fluent in Farsi, Arabic and English.

Open‐ended FG questions were initially constructed based on the review of literature, and were then reviewed and modified by independent expert faculty members, Health Canada's nutrition advisors and community facilitators. Guiding questions and FG procedures were then piloted with five Middle‐Eastern mothers for confirming clarity, relevance and comprehension. Generally, questions targeted methods of infant feeding, beliefs around infants’ health, mothers’ feeding intentions during pregnancy and sources of infant feeding information. These questions were supplemented by transition questions as well as by clarifying, probing and challenging questions to yield more in‐depth responses (Wilkinson 1998). Beyond this, a flexible approach was taken ensuring that mothers directed the discussions (Wilkinson 1998).

The FGs were audio‐taped and transcribed verbatim immediately after each FG and pseudonyms were used throughout to ensure the anonymity of participants. Field notes (mainly of participants’ interactions and non‐verbal expressions) and analytical memos written periodically during the study were also used to inform the analyses. Transcripts were analysed after being verified for concordance with audiotapes. Thematic analyses of mothers’ comments were performed independently by the principal investigator and the facilitator in the language of FGs in order to preserve linguistic authenticity (Richards & Morse 2007). Data were analysed line by line and words/phrases that captured the emerging issues were highlighted. These words or phrases formed the initial coding scheme and were then categorised into meaningful clusters. The categorised recurrent themes were discussed with the research team and further refinement of the overall coding was performed upon reaching unanimous agreement. Patterns and relationships between the categories were identified and main themes were synthesised, which reflected maternal beliefs and cultural values about infant feeding. Interaction data were analysed using the congruent methodological approach (Duggleby 2005).To determine the importance given to each topic, judgments were made about frequency (number of times a topic was mentioned), extensiveness (number of mothers who mentioned the topic), intensity (the depth of feelings expressed), specificity (the use of personal specific experiences) and level of agreement (Tiggemann et al. 2000).

Survey

Survey data were collected at the end of each FG using pre‐tested questionnaires developed for the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) study (see http://www.Apronstudy.ca for further details). Permission to adopt these questionnaires was sought by the graduate supervisor (A.P.F.), who is an investigator of the APrON study. Data were collected on socio‐demographic characteristics and the health status of participating families. Questionnaires, consent forms and recruitment posters were translated independently by the researcher and the facilitator and were then back‐translated into English and checked for accuracy by bilingual community leaders of Middle‐Eastern mothers. Quantitative survey data were analysed by simple descriptive statistics using the Statistical Software for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Because the number of participants in each ethnic group was small, data were not analysed separately for each ethnic group.

Results

Most of the participants were new settlers with 18 of 22 residing in Canada for <5 years. All mothers followed the Islam religion, 17 of 22 had an educational level of ≤high school, 15 of 22 were unemployed and 17 of 22 had annual household income of <$40 000 (Table 1).

At the beginning of the FGs, mothers tended to mention only factors that encouraged them to breastfeed. However, with little prompting, they became more forthright, starting to criticise the Canadian health care system and the Western society for not being more supportive of breastfeeding. Throughout the FGs, women were speaking enthusiastically and loudly all at the same time, and discussions were far ranging and freely flowing. Participants talked from a very broad perspective and explained how their living conditions, beliefs and values influenced their choice. The breastfeeding perceptions of these mothers were deeply rooted in their spiritual beliefs and cultural values.

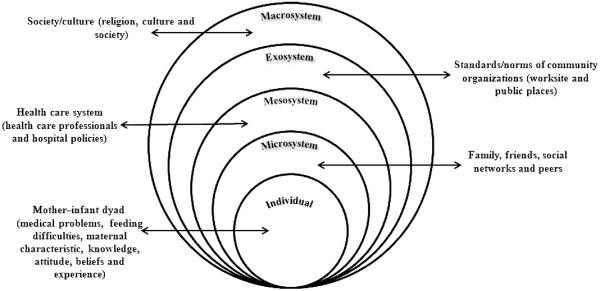

We identified the beliefs and values that shaped breastfeeding practices in the following five areas: (1) society/culture; (2) community; (3) health care system; (4) family/friends; and (5) mother–infant dyad. We applied the human ecological framework to breastfeeding in order to cohesively conceptualise these overlapping spheres of influence (Fig. 1) (Bronfenbrenner 1986; Tiedje et al. 2002). The human ecological model considers processes operating in different layers of the concentric circles to be bidirectional and have an impact on each other. The following section begins with describing the macro‐level influences and continues through the micro‐level factors.

Figure 1.

Different levels of influence explaining the breastfeeding behaviours of Middle‐Eastern mothers in Canada according to the human ecological framework. Sources: Bronfenbrenner U. (1986) Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology 22 (6):723–742 . Tiedje LB, Schiffman R, Omar M, Wright J, Buzzitta C, McCann A, Metzger S. (2002) An ecological approach to breastfeeding. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 27(3):154–161; quiz 162.

Societal/cultural influences

Religious beliefs

Beliefs rooted in Islamic teachings were a central feature of the society within which the participants lived their daily lives and engaged in breastfeeding. These teachings provide specific instruction about breastfeeding. It is not surprising that mothers were extremely motivated to continue breastfeeding because they had decided to do so since childhood. Mothers attributed their breastfeeding success to cultural and religious beliefs rather than to support and encouragement of health professionals. Mothers mentioned that breastfeeding for 2 years is explicitly recommended in the holy book (Qur'an) and by the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH), and therefore disobeying is a sin:

Fatheema: : ‘… from an Islamic point of view we are supposed to breastfeed for 2 years if we can … and when it is in Qur'an I feel like it is important.’

Abeer: : ‘Breastfeeding takes lots of patience and … you should be very determined …. I was about to stop long time ago … but I thought when Allah says you have to do it there must be some benefits.’

Some women stated that religious beliefs of family members also influenced their decision to breastfeed:

Najla: : ‘… my mother has breastfed us and that influenced me and my sisters a lot …. She always says that is what Allah wants us to do.’ [Speaks while breastfeeding]

Mothers were dissatisfied with being unable to practise 40 days of rest post‐delivery, and to adopt a wet nurse when problems arise. They expressed positive experiences with wet‐nursing in their home countries:

Amina: : ‘When my first baby was born in my country, I could not breastfeed …. I wanted to feed him formula but my mother said: “no!” … they asked my cousin, who had just given birth, to feed my baby too and she helped a lot until my milk problem was solved … this helped prevent my infant from getting used to the bottles.’

Qamar: : ‘Me too … my milk was not enough so my sister did that [breastfeeding] and alhamdulilah [praise to Allah] it worked well because she had lots of milk …’

Adopting a wet nurse was not possible in the Canadian context because the wet nurse should be Muslim and someone whom the mother knows and is confident of her proper Islamic behaviours. It is believed that the morals of a wet nurse influence those of the child. In addition, mothers stated that Western women were unaware of such practices:

Qada: : ‘… if you tell them [about the wet nurse], they will laugh at you … they have never even heard of it.’

Sabah: : ‘In Western countries, breast is a sexual thing and if you ask them [to be wet nurse] they might even get mad …. Also, a Muslim should feed your baby not everyone is allowed.’

Because this study was conducted immediately before Muslims’ month of fasting (Ramadan), the concern for milk insufficiency was also raised. All mothers had planned to fast and supplement infants’ diet with foods, if necessary:

Alia: : ‘I can tolerate fasting quite well … I was pregnant with my first baby in Ramadan and I fasted the whole month, and the next year I was breastfeeding him and I fasted the whole month.’

Everyone: : ‘MashaAllah’ [appreciation]

Alia: : ‘I intend to do the same this year for my daughter … although summer days are too long in Canada but Allah will help InshaAllah.’ [If Allah wills]

Everyone: : ‘InshaAllah’ [If Allah wills]

Tension between religious beliefs and beliefs in host country

Participants described numerous points of tension between their own beliefs rooted in Islamic teachings and the perceived beliefs held by Canadians. For example, in one FG, one of the mothers mentioned the milk bank, which was unfamiliar to all other participants. Generally mothers did not support the idea from an Islamic point of view:

Qada: : ‘Even if they [physicians] tell us that it [donated milk] is necessary, we cannot use it, because we do not know who that milk is coming from.’

Faiqah: : ‘In Islam if you donate or get milk from someone, your babies will be sisters and brothers and then cannot marry, although feeding should happen 15 times but still … I do not like the idea because not everyone is proper to feed my baby.’

Culture

Practices such as cessation of breastfeeding during pregnancy and pre‐lacteal feeding were commonly practised. Mothers believed that their culture is not adequately respected in Canadian society:

Habiba: : ‘… They [Canadians] try to change your habits and cultural practices … without knowing what your practices are … they have this feeling that we are always wrong.’

Society

Participants were critical of the lack of social support for breastfeeding by some Canadians. Mothers mentioned that it appears that the Canadian society viewed breastfeeding as an outdated, time‐consuming and restrictive task, which was harmful to mothers’ physical attractiveness. They thought that these negative beliefs could influence mothers’ breastfeeding practices negatively, if they did not deeply believe in them:

Badra: : ‘One of my coworkers always warns me: “you are destroying your body at such a young age … your breasts would deflate and your body will be so awful after a year.” ’

Alia: : ‘…. neighbors tell me: “breastfeeding takes much of your time … and it is a very old way of feeding maybe for a woman of hundred years ago” …. as a Muslim I do not care for what they say I believe it [breastfeeding] from my heart.’

Sabah: : ‘… once I talked about breastfeeding to my employer's wife and she said “I have never breastfed” and when I asked the reason she answered: “breastfeeding reminds me of cow, a peasants’ practice and I cannot accept someone drinking milk out of me” …. it was really off‐putting for me as a pregnant woman.’

Faiqah: : ‘… like the woman I visited at the infant ward in hospital, she told me: “why do you resist the formula? You are starving the baby. You would be better forgetting this nonsense breastfeeding” …. When I told my husband he said that they could say whatever they wanted, and that I should not let anyone discourage me from what Allah has advised us to do.’

Community influences

The participants provided further detail about the tensions between their beliefs about breastfeeding and the beliefs that were dominant in Canadian society, as reflected in some employment practices, the lack of places for breastfeeding outside of their homes, and their experiences with health care professionals.

Employment

Although most mothers were either unemployed or worked from home, some of the employed mothers had returned to work 4 months after delivery because of financial problems. Employed mothers were dissatisfied with the lack of nursing rooms at worksites and having to pump their milk in the washrooms. Pumping milk in the washroom was not a pleasant experience, especially (as mothers mentioned) ‘for shy Muslim mothers who were gazed at by colleagues’. The main cited reasons for choosing not to work were: high cost of day care per day home, necessity of feeding Halal (Arabic word meaning ‘permitted’) foods to children, which required maternal supervision, and having multiple children at home:

Aaysha: : ‘The cost of day home is more than our apartment's monthly rent, let alone the day care which is even more expensive. The quality of care is so poor in both … I do not have anyone to leave the kids with and so I do not go to work.’

Faiqah: : ‘That's why I decided not to work as my husband said: “the money you make if you have to put it in a day care that is really no point.” … I would rather stay at home and make handmade gift boxes, I prefer working from home.’

Muslim mothers were also concerned about culture and religion of day homeowners and the poor quality of childcare:

Suraya: : ‘… I checked with other mothers and they said that day home owners do not feed babies their milk … and the food is of poor quality.’

Aidah: : ‘…. Also in day cares they have schedules for everything. They make children sleep when it is sleep time no matter if they are tired or not.’

This situation was intolerable especially for Middle‐Eastern mothers who had previously received from their home country considerable worksite support through policies such as ‘nursing breaks’ (30 min for 2 h of work), long‐term paid maternity leave and on‐site subsidised child‐care facilities. Mothers suggested that these provided employed mothers with flexibility to work and breastfeed without concern.

Public places

For these young Muslim mothers, breastfeeding in public created a dilemma between their desire to breastfeed and feelings of shame and prudence. Breastfeeding in public had never been a problem for Muslim mothers in their home countries because of the presence of ‘Mosalas’ (mosques) in all public places, which is used for breastfeeding. Mosalas have designated places for women in which men are not allowed to enter. Environmental barriers, such as the lack of nursing rooms in most public places, unacceptability of family rooms that allow male parents to enter, and negative attitudes of Western society towards breastfeeding in public make it a challenge for Muslim mothers to breastfeed in public. Mothers noted that infants did not comfortably feed under nursing covers or hijabs, and said that standing in washrooms to breastfeed was unpleasant:

Alia: : ‘… so I am in a store and then I have to go to the washroom and spend an hour or so standing breastfeeding and burping and then changing and …. I hate going out.’

Badra: : ‘But my question is: are we really supposed to feed a baby in a washroom? … because we are not supposed to eat in a washroom.’

Qada: : ‘Like I last week went to a mall and they had this room that had a changing table and a sink, and then there were few chairs so you could breastfeed in there but the ridiculous thing is that it was a family room …. So when I went in there a woman and her husband were there changing their baby, so I waited until they left because I cannot feed the baby in front of men …. Then I do not know if guys are allowed to come in, what is the point of nursing rooms?’

[Group admits]

Muslim mothers explained adopting several coping strategies for breastfeeding in public, such as using nursing covers, and shopping at stores with breastfeeding rooms. However, they noted, feeding infants food and drinks alternatively was always an easier option:

Aaysha: : ‘… I always have some mashed dates or Muhallabia (rice pudding) with me when I go outside …. cause I don't feel comfortable [breastfeeding] even around women.’

Badra: : ‘I usually pump and take my milk outside but that doesn't always happen because sometimes you are in a hurry and haven't really planned ahead … it is just easier to take a bottle of homo‐milk or foods outside.’

Negative attitude towards breastfeeding in public in Western society was yet another concern:

Mahnaz: : ‘… even when you are breastfeeding under nursing covers, all passers‐by stare at you as if you are committing a crime … this is really off‐putting.’

[Group agrees]

Community services

Except for one, none of mothers were aware of community resources for breastfeeding support (e.g. pre‐/post‐natal classes offered through community services). This lack of knowledge was attributed to reliance of these facilities on word of mouth and networking, and lower proficiency in English and health literacy for some mothers.

Health care system influences

Participants thought some Canadian health care professionals were not as supportive of breastfeeding as they could be, at least compared with their previous experience with health care professionals from their home countries.

Health care policy

They noted the lack of consensus on infant feeding advice received from hotline services (available through health services), brochures, nurses, physicians and other health care staff. These discrepancies had left mothers confused about proper practices and resulted in mistrust of the Canadian health care system. Mothers suggested that it appears that some clinicians provide support based on their own personal experiences and beliefs, rather than according to a standard policy:

Aidah: : ‘… With my daughter they said you could start homo‐milk at 9 months … and with my son they said: “no! leave it to 1 year”, and then with him [points to her son who is sleeping in her arms] the doctor said it is safe. I was worried but he said it was okay to start at 6 months because his growth is so good mashaAllah [appreciation] … each doctor says something different.’

When mothers were asked about health care use, enthusiastic long discussions were often ignited. There is room for improvement in the area of educating and familiarising newcomers with available services and the way the health care system works. The majority of Middle‐Eastern mothers were unaware of breastfeeding clinics and hotlines:

Shahla: : ‘After discharge I was feeling guilty that my milk was not enough … so after 3 weeks when I went to a gynecologist, I asked her if there were any possibilities that I could breastfeed him without formula, and she then referred me to the breastfeeding clinic … I did not know such facilities existed …. I had pumped and fed him breast milk in bottle since birth and he was used to it …. they [clinicians] should inform us of these options in case problems occurred.’

Those who had used health care services found it inefficient because of long waiting lists for clinics and the high costs of drugs and supplements:

Setareh: : ‘The breastfeeding clinic nurse recommended a pill for increasing my milk that costs $100 …. I would rather give my baby table foods cause we cannot afford it’

In addition, mothers found clinicians’ solutions for infant feeding problems rather impractical:

Habiba: : ‘My grandmother and mother say: “when babies cry, feed them”. But here [in Canada] they [physicians] put you on a schedule and say, for example, “breastfeed every 2 hours!” ’

Suraya: : ‘I think in the West, physicians are too focused on employed mothers; so they have come up with these schedules … but it ignores all cues in the baby and contradicts the natural ways of infant feeding.’

The most significant problem that hindered Middle‐Eastern mothers’ use of health care was perceived lack of cultural competency among health care providers, provision of health care and resources only in English language, and at the same time mothers’ lack of language proficiency:

Habiba: : ‘My physician also talks very fast and with an accent that I don't understand; my husband is very busy and cannot accompany me [to the hospital] all the time …. If they [clinicians] really want us to use these services, they should consider our language abilities.’

Middle‐Eastern mothers had to rely on their family members in order to use the health care system:

Abeer: : ‘I have to wait for my older children to get back from school and call on my behalf to the Health Link when I have problems with my younger one … but sometimes I really do not want to take too much of my children's time, so I just let go.’

All mothers agreed that inclusion of bilingual clinicians in health care systems facilitates higher health care use among new settlers, although they believed this was more like a ‘dream’:

Mehri: : ‘Why Canada with this many immigrants and refugees does not provide health care in different languages? If it did, we would have known that even if we go there [hospitals] without our husband or children, there is one nurse who understands what we say.’

Health care staff

Generally, mothers were dissatisfied with lack of emotional support post‐delivery for immigrant/refugee mothers despite their loneliness. Mothers perceived that clinicians did not encourage breastfeeding initiation due to having a pre‐assumption that most mothers are unwilling to breastfeed. Some of these impressions may result from the mixed reactions from health professionals; some clinicians encouraged breastfeeding while others did not. Some nurses may have refrained from educating mothers on appropriate methods of breastfeeding because of the convenience of free commercial formulas:

Shohreh: : ‘I had natural childbirth delivery for my third daughter and I did not have any problems, so I was just sitting on the bed breastfeeding when the nurse suddenly came holding a box of liquid formula, and Allah! she was shocked seeing me breastfeeding. She said: “oh … you know how to do it!”, and I said: “yes! This is my third child” … for my previous children in Iran, they [health care staff] did not offer any formula, although I did not know how to breastfeed then. In Iran, nurses gave me time and education and encouraged me and insisted that I could succeed; that is the way I managed to do it.’

Farnaz: : ‘The nurse at the breastfeeding clinic encouraged me a lot and she gave me some pills to improve my milk output. But when I showed the pills to my physician to see whether they were safe, he smiled ironically saying: “if you let them [breastfeeding clinic nurses], they would suggest breastfeeding until the child is 10‐year old! Why don't you feed the formula instead?” ’

In addition, health care professionals’ lack of awareness of the differences between infant feeding recommendations offered in different countries was another problem:

Shohreh: : ‘Once the physician found that I have previously had children he stopped offering me information on what to feed my baby …. (Last month) he figured she [infant] had anemia, and asked me about the foods that I feed her. I was so proud to tell that I only feed her home‐made foods, but he shouted at me saying I have to give her ready foods.’

Setareh: : ‘Like fast foods?’

Shohreh: : ‘No … he meant baby foods …’

Mehri: : ‘I think that is because in the Middle East, iron supplementation is mandatory from 4 months, but it is not in Canada.’

It is important to note that in Canada, some of the infant food products are iron‐fortified, which replace the iron supplements that are commonly used in some other countries.

Family/friends influences

Despite living far away from home, mothers still depended on family and friends’ advice because they viewed them as tangible moral and emotional sources of support, reliable sources of information and role models. Having been breastfed and being exposed to breastfeeding from an early age were important factors influencing maternal feeding decisions. Mothers trusted their family and friends’ advice more than those from health care professionals:

Fatheema: : ‘I trust my mother's advice because she has breastfed 9 children and had raised us healthy …. Those hotlines and health services recommend you things that are not practical; they lack the experience component …’

In addition, Muslim husbands supported breastfeeding, which positively influenced mothers’ decisions:

Aidah: : ‘I wanted to give up [breastfeeding], but my husband said: “just give it a few more days, you would regret if you give it up now”. And I am glad that I did not [give up] … he always supports me in that way.’

However, lack of support and supervision of female relatives and friends was a concern for these young immigrant/refugee new settlers, especially primiparous mothers who lacked confidence:

Aaysha: : ‘In the beginning, my baby cried a lot and I did not know what to do …. you have your millions of options: does he need to be changed? Is he hungry? I did not know! After struggling for 2 days, the nurse came to visit us at home and she said that my milk was not coming enough …. If my mother was here with me, I am 100% sure that she would have figured from the beginning …. Now that I am experienced I could tell too, but in the beginning no one helped.’

Mother–infant dyad influences

Participants enumerated many individual problems that they themselves and their peers had experienced challenging their breastfeeding experience. These factors could be categorised as medical problems, feeding difficulties, lack of information and maternal characteristics.

Medical problems

Most of these young mothers had experienced post‐partum depression, although the majority attributed it to seasonal depression, language barriers, loneliness, lack of support, burden of household duties and being culturally restricted from having close contact with society:

Shahla: : ‘After discharge I was so depressed that I cried all day and night … It had even influenced my breastfeeding negatively … after a week my husband called Alberta Health Link and they [nurses] said that it was “baby blues”. I never knew of something like that’. [Mother used the word “baby blues” in English]

Mahnaz: : ‘Is it when baby gets blue out of crying?’

Shahla: : ‘No, it is actually related to mother and not the baby. It is a kind of depression after delivery …. During that period my milk supply was so low that I had to bottle‐feed also.’

Farnaz: : ‘I was in the same situation, but I think it is mainly because of being alone and without support … you think you need someone to be with you and at least burden some of your duties, but there is nobody there.’

In addition, in this study, infant health problems were reported to interfere with breastfeeding including: immaturity, inability to suckle milk, colic, jaundice, cardiac problems and respiratory diseases.

Feeding difficulties

The most commonly cited problems clustered around milk insufficiency, poor latching, thickness of milk and insufficient milk outflow:

Mahnaz: : ‘Two days after discharge and I had nipple ulcers and severe breast pain. I did not know what to do …. Finally, I asked a sister [Muslim friend] who also had a baby and she gave me an ointment. You cannot believe, when I used it all ulcers disappeared.’

From the participants’ point of view, perceived milk insufficiency was the result of poor dietary intakes and lack of adequate rest. Inadequacies in dietary intake were rooted in material deprivation and cultural traditions, which led to food insecurity. Mothers stated that as a cultural norm, they often sacrifice their own needs for the sake of the health and food security of others in the family.

Most of the women were challenged facing multiple roles as employees, mothers and wives. These were particularly challenging for mothers who worked outside of the home, in addition to having the burden of domestic responsibilities. Mothers mentioned that in their patriarchal culture, men are not supposed to help with feminine household tasks and that it was expected:

Fatheema: : ‘Although I pump milk at work, it is not as much as before …. My mother says it is because I work too hard and do not rest enough …. I still enjoy breastfeeding, although I also feed her sugary water or Muhallabia (rice pudding) when she is not full. You cannot believe [laughs], when I get home from work I sit on the floor like this breastfeeding and my other kids are around me while I am chopping foods and making dinner before my husband arrives.’

Maternal characteristics

Generally, mothers had such positive attitudes towards breastfeeding that all but one, were breastfeeding and intended to continue for at least 2 years. This strong belief and confidence in breastfeeding was shaped through their Islamic background, advice from family and friends ‘back home’, and their previous positive breastfeeding experience. Mothers described breastfeeding by using words such as ‘pleasant’, ‘natural’ and ‘healthy’, and they considered the ‘mother–infant bonding’ formed during breastfeeding to be a rewarding experience. Generally, mothers believed that if breastfeeding is stopped voluntarily, the purpose of motherhood is under question.

Abeer: : ‘I guess breastfeeding is different from formula feeding in that children get hungry faster with the breast milk … But I do not really mind … I have made this a priority. I am just okay so breastfeeding is my priority.’

Discussion

The ethnographic approach provided an opportunity to explore Middle‐Eastern mothers’ perspective and shed light on the cultural/societal, community, health care system, social networks and mother–infant dyad factors that influence breastfeeding after migration to Canada. Cultural and religious beliefs about breastfeeding emerged as the most important factors influencing infant feeding decisions and empowering mothers to overcome external barriers to breastfeeding. All mothers, with the exception of one, were breastfeeding since birth and were intending to continue for at least 2 years. Although breastfeeding rates were high among these mothers, none of them were exclusively breastfeeding because of the cultural custom of pre‐lacteal feeding.

High breastfeeding rates observed in the present study are in accordance with those in previous research. Middle‐Eastern mothers have the highest rates of breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration compared with other ethnic groups, both in their home countries (i.e. mean breastfeeding duration = 21 months) (Roudbari et al. 2009) and after migration to Western societies (Ghaemi‐Ahmadi 1992; Dahlen & Homer 2002; Homer et al. 2002). Participants in this study reported several health benefits to breastfeeding, including its healing potential, convenience and cost‐effectiveness. Other studies have shown Arab mothers to support breastfeeding and consider it as the easiest and most nutritious method of feeding (Al‐Nasser et al. 1991).

Generally, in the present study, the decision to breastfeed among Middle‐Eastern mothers appears to be shaped by spiritual and religious beliefs. Mothers demonstrated their commitment to breastfeeding for at least 2 years despite a variety of factors at the community, health care and individual level that may negatively influence maternal breastfeeding decisions. Islamic teachings and advice promoted in the Qur'an influence all aspects of culture and tradition in the Middle East, which formally recommends 2 years of breastfeeding as a right of Muslim children. However, those who do not abide to these rules are considered sinful and cruel (Pak‐Gorstein et al. 2009).

Muslims are advised not to feed animal milk to their infants, and instead, foster a ‘wet nurse’ in situations where the mother is unable to breastfeed, so infants preserve their sucking ability and benefit from the breast milk. There were many barriers preventing mothers from this practice in Canada. Because many of the mothers lacked social supports, engaging a trustful Muslim mother to serve as wet nurse was often not possible. Yet, at times, when mothers perceived they had insufficient milk, they preferred to feed their infants solids rather than relying on a surrogate to breastfeed. In addition, mothers’ belief that children who are breastfed by the same mother are considered siblings and are prohibited from marrying each other is an important consideration when establishing donor human milk programmes in Muslim communities (Shaikh & Ahmed 2006).

Fasting during Ramadan was another Islamic practice with implications for breastfeeding. Although breastfeeding mothers are temporarily exempted from fasting from an Islamic perspective, all mothers in the present study indicated their intentions to fast. This has been attributed to mothers’ unawareness of breastfeeding rules in Islam. Also, there is the belief that milk production is not jeopardised by fasting and even if it is, solid foods could replace the breast milk during the month of Ramadan. Another justification for mothers’ decision to fast during breastfeeding might be their willingness to accompany their husbands and family in the fasting rather than having to fast alone at a later time because all missed fasting days should be compensated by nursing mothers once they cease breastfeeding (Shaikh & Ahmed 2006). Fasting during breastfeeding exemplifies a practice that contradicts religious teaching and offers a useful opportunity for developing educational campaigns to target Muslim mothers through the support of their religious leaders.

Unlike the teachings of Islam, which have a positive influence on continuation of breastfeeding, Middle‐Eastern ‘culture’ has a negative impact on its exclusivity by promoting introduction of solids at an early age. Previous studies conducted in Persian Gulf countries have indicated high rates of pre‐lacteal feeding and mixed feeding (Al‐Nasser et al. 1991). Interestingly, Middle‐Eastern mothers in Canada introduced the same types of foods that mothers commonly feed their infants in the Middle East. Such foods as ghee (melted clarified butter), dates, honey and water are fed from the first days of life, to strengthen the baby and lubricate the intestine, while glucose and herbal water are fed during the first week in the belief that they are providing colic relief (Musaiger 1996).

Participants in this study consistently compared governmental and community support for breastfeeding in the Middle East with those in Canada. Canadian worksite policies were criticised when compared with the Middle‐Eastern policies (e.g. full paid leave, nursing breaks and subsidised child‐care facilities). In addition, modesty and privacy of Muslim mothers are not facilitated in Western societies because of lack of nursing rooms in most public places, while Muslim mothers are provided with nursing rooms in all public places in their home countries. Previous studies have suggested that supportive breastfeeding macro‐policies in the Middle East positively influence breastfeeding rates among mothers (Ghaemi‐Ahmadi 1992). Mothers in the present study perceived negative attitudes of some Canadians towards breastfeeding, and this has also been noted in previous research where Canadian mothers reported being restricted and housebound because of the social stigma associated with nursing in public, which eventually resulted in their breastfeeding cessation (Pollak et al. 1995). In another study, Canadian mothers described their insecure feeling of breastfeeding in public by terms such as ‘vulnerable’, ‘nervous’ and ‘self‐conscious’ (Sheeshka et al. 2001). It has been suggested that social and cultural factors may jeopardise breastfeeding success if mothers feel embarrassed by breastfeeding in public or if they worry that others find breastfeeding offensive (Sheeshka et al. 2001).

At health care system level, mothers claimed that Muslim physicians and nurses in the Middle East have a strong belief in breastfeeding and are consistent in the messaging to mothers regarding breastfeeding compared with some of the health care staff in Canada. There were times when participants received contradictory advice and this seemed unacceptable to new‐settler mothers resulting in mistrust of the Canadian health care system. This is in line with previous migrant studies that suggest that recommendations from medical staff are perceived as vague, negative and inconsistent (Rossiter 1998). Specifically, Canadian physicians have shown low self‐efficacy for breastfeeding counselling and high rates of misinformation and lack of interest, and some have been reported to provide erroneous advice to mothers (Burglehaus et al. 1997). Because physicians can influence breastfeeding behaviours considerably, these findings are concerning and call for an action to strengthen the competence of physicians in breastfeeding counselling through high‐quality and specific training sessions (Burglehaus et al. 1997).

Moreover, mothers in the present study were dissatisfied with the routine practice of bottle feeding in Canadian hospitals, which influenced the breastfeeding ability of infants. This confirms the findings of a national Canadian survey that suggest lack of adherence of hospital practices to the guidelines of the World Health Organization/UNICEF Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, such as avoiding pacifier use, not providing free formula samples for mothers, early skin‐to‐skin contact between mother and infant, rooming‐in, demand feeding and exclusive breastfeeding (Chalmers et al. 2009). The open concept (i.e. four beds in hospital room) of Neonatal Intensive Care Units presented a dilemma for these shy Muslim mothers. Mothers in this study and other studies reported occasions when health care practitioners could have practised more culturally sensitive care and used portable privacy screens or baby blankets when mothers breastfeed (Pak‐Gorstein et al. 2009).

Given the lack of cultural and language competency of health care staff, community and hotline services were cited as a barrier to accessing and using health care services among participants. Mothers suggested that provision of care in their native languages may potentially increase their confidence and health care use. Cultural competency of practitioners would be enhanced by considering the teaching of Islam and the strong cultural link between religion and infant feeding practices of new settlers from the Middle East. It is pertinent to understand that breastfeeding is not simply a nutritional or health care choice, but has a religious basis in this population.

At the personal level, several maternal characteristics influenced infant feeding practices. In Canada, higher breastfeeding rates have been shown among mothers with higher socioeconomic status (Al‐Sahab et al. 2010), which is justified by the fact that higher education helps mothers formulate well‐informed infant feeding decisions. In contrast to Western countries, women with higher education in developing countries have lower rates of breastfeeding, which might be due to social transition and westernisation (Amin et al. 2011). Mothers in Gulf countries are usually illiterate or have lower education levels, which is favourably associated with higher duration of breastfeeding (Musaiger 1996).

Finally, the level of poverty experienced by families in the present study made mothers sacrifice their own needs in order to ensure food security for their husband and children. This self‐sacrifice, which is a common tradition in the Middle East, resulted in poor maternal dietary intakes and their breast milk insufficiency. In Arabic culture, societal expectations often compromise women's health especially after delivery. Women are expected to continue their role of taking care of their husband and children and doing the housework and they should not complain about the difficulties, otherwise they would be labelled as a ‘bad wife’ (Nahas et al. 1999). Upon migration to Western countries, women have to also shoulder financial responsibilities by working because of economic demands, all of which contribute to women's poor health. Overall, ethnic mothers often suffer from cultural, racial and language barriers, which influence their social and health problems as well as their infants’ health (Manderson & Mathews 1981).

There are several strengths associated with the present research. This is the firstly study to explore Middle‐Eastern mothers’ infant feeding beliefs and practices after migration using qualitative methodology. Secondly, conducting FGs in mothers’ native languages by bilingual researchers, translation and back‐translation of forms, transcripts (quotes) and final codes, and analysing the data in the language of interviews resulted in an enriched data. The limitation of this study, however, is inherent in its qualitative design. Being a pilot hypothesis‐generating study, only a small number of participants were recruited, although Sharp (1998) suggests that theoretical generalisation arising from a non‐representative sample is valid and it generates theoretical explanation for the phenomena.

Findings from the present study inform an urgent need for development of in‐service educational strategies targeting exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding and maternal nutrition among this group. Health care professionals need continuing education that provides common messaging to avoid inconsistencies, because practitioners’ behaviours are the most influential at the front lines in the perception of ethnic mothers from primary health care. Although our findings might be of relevance to many young refugee/immigrant Middle‐Eastern mothers in Canada, it is suggested that further research is conducted to determine if these findings resonate with other mothers of similar socioeconomic context in the Canadian society.

Source of funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the WCHRI, through the funds of the ‘Stollery Children's Hospital Foundation’; Alberta, Canada. M.J. is partially funded by the ‘2011 Dr Elizabeth A. Donald M.Sc. Fellowship in Human Nutrition’.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

This study is based on part of a M.Sc. thesis submitted by MJ to the University of Alberta, Canada. MJ conceptualised the study, conducted the FGs, analysed the data and drafted the paper. APF guided and supervised the study and assisted in interpretation of findings and finalising the paper. KO helped with designing the study and data analyses and provided professional comments.

Acknowledgements

This work was not possible without the keen support of Multicultural Health Brokers Co‐operative Ltd, Muslim Community of Edmonton Mosque (MCE) and Community‐University Partnership (CUP) programme in Edmonton. We are grateful to Ms Kara McCarthy, Ms Yvonne Chiu and Dr Muna Murad who assisted us in conducting the FGs. We also acknowledge Dr Noreen Willows (University of Alberta) and Ms Hélène Lowell (Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Health Canada) for providing input on the FG guides.

References

- Al‐Nasser S.N., Bamgboye E.A. & Alburno M.K. (1991) A retrospective study of factors affecting breastfeeding practices in a rural community of Saudi Arabia. East African Medical Journal 68, 174–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Sahab B., Lanes A., Feldman M. & Tamim H. (2010) Prevalence and predictors of 6‐month exclusive breastfeeding among Canadian women: a national survey. BMC Pediatrics [Electronic Resource] 10, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin T., Hablas H. & Al Qader A.A. (2011) Determinants of initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Breastfeed Medicine 6, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour R.S. (1999) The use of focus groups to define patient needs. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 28, S19–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R.E., Allen L.H., Bhutta Z.A., Caulfield L.E., De Onis M., Ezzati M. et al; Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 371, 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1986) Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Developmental Psychology 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Burglehaus M.J., Smith L.A., Sheps S.B. & Green L.W. (1997) Physicians and breastfeeding: beliefs, knowledge, self‐efficacy and counselling practices. Canadian Journal of Public Health. Revue canadienne de sante publique 88, 383–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celi A., Rich‐Edwards J., Richardson M., Kleinman K. & Gillman M. (2005) Immigration, race/ethnicity, and social and economic factors as predictors of breastfeeding initiation. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 159, 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers B., Levitt C., Heaman M., O'Brien B., Sauve R. & Kaczorowski J.; Maternity Experiences Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System, Public Health Agency of Canada (2009) Breastfeeding rates and hospital breastfeeding practices in Canada: a national survey of women. Birth 36, 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen H.G. & Homer C.S. (2010) Infant feeding in the first 12 weeks following birth: a comparison of patterns seen in Asian and non‐Asian women in Australia. Women and Birth 23, 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey K. (2004) Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child [online] . Pan American Health Organization, Division of Health Promotion and Protection: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/a85622/en/index.html (Accessed 20 December 2011).

- Duggleby W. (2005) What about focus group interaction data? Qualitative Health Research 15, 832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field P.A. & Morse J.M. (1985) Nursing Research: The Application of Qualitative Approaches. Aspen Publishers: Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi‐Ahmadi S. (1992) Attitudes toward breast‐feeding and infant feeding among Iranian, Afghan, and Southeast Asian immigrant women in the United States: implications for health and nutrition education. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 92, 354–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway I. & Wheeler S. (2002) Qualitative Research in Nursing. Blackwell: Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Homer C.S., Sheehan A. & Cooke M. (2002) Initial infant feeding decisions and duration of breastfeeding in women from English, Arabic and Chinese‐speaking backgrounds in Australia. Breastfeed Review 10, 27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magila N., DeVine D. et al (2007) Breastfeeding and Maternal and Child Health Outcomes in Developed Countries, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD. AHRQ Publication No 07‐E007. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler P.G. & Sucher K. (2007) Food and Culture , 5th edn, Cengage Learning: Independence, KY. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S. & Kakuma R. (2004) The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 554, 63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R. & Casey M. (2000) Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research , 3rd edn, Sage: Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Lett J. (1990) Emics and etics: notes on the epistemology of anthropology In: Emics and Etics: The Insider/Outsider Debate (eds Headland T.N., Pike K.L. & Harris M.), p 130 Frontiers of anthropology, v.7. Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Manderson L. & Mathews M. (1981) Vietnamese attitudes towards maternal and infant health. The Medical journal of Australia 1, 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meedya S., Fahy K. & Kable A. (2010) Factors that positively influence breastfeeding duration to 6 months: a literature review. Women and Birth 23, 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. (1997) Focus Groups as Qualitative Research (Qualitative Research Methods) , 2nd edn, Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Musaiger A.O. (1996) Nutritional status of infants and young children in the Arabian Gulf countries. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 42, 121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahas V.L., Hillege S. & Amasheh N. (1999) Postpartum depression. The lived experiences of Middle Eastern migrant women in Australia. Journal of Nurse‐Midwifery 44, 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer G.M. (2001) Paradigm lost: race, ethnicity and the search for a new population taxonomy. American Journal of Public Health 91, 1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak‐Gorstein S., Haq A. & Graham E.A. (2009) Cultural influences on infant feeding practices. Pediatrics in Review 30, e11–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak A., Robson R. & Evers S. (1995) Study of Attitudes on Breastfeeding. (Health Canada Cat. No. 0‐662‐23702‐1). Sage Research Corporation: Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Reed J. & Payton V.R. (1997) Focus groups: issues of analysis and interpretation. Journal of Advanced Nursing 26, 765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. & Morse J.M. (2007) Readme First for a User's Guide to Qualitative Methods , 2nd edn, Sage Publications, Inc: Thousands Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter J.C. (1998) Promoting breast feeding: the perceptions of Vietnamese mothers in Sydney, Australia. Journal of Advanced Nursing 28, 598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudbari M., Roudbari S. & Fazaeli A. (2009) Factors associated with breastfeeding patterns in women who recourse to health centres in Zahedan, Iran. Singapore Medical Journal 50, 181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmoll B.J. (1987) Ethnographic inquiry in clinical settings. Physical Therapy 67, 1895–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh U. & Ahmed O. (2006) Islam and infant feeding. Breastfeed Medicine 1, 164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp K. (1998) The case for case studies in nursing research: the problem of generalization. Journal of Advanced Nursing 27, 785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeshka J., Potter B., Norrie E., Valaitis R., Adams G. & Kuczynski L. (2001) Women's experiences breastfeeding in public places. Journal of Human Lactation 17, 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada (2005) Population Projections of Visible Minority Groups, Canada, Provinces and Regions (2001–2017) . Ottawa, Ontario. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?catno=91-541-X%26lang=eng (Accessed 24 December 2011).

- Statistics Canada (2010) Definition of Immigrant . Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/81-004-x/2010004/def/immigrant-eng.htm (Accessed 24 December 2011).

- Statistics Canada (2011) Health Indicator Profile, Annual Estimates, by Age Group and Sex, Canada, Provinces, Territories, Health Regions (2011 Boundaries) and Peer Groups, Occasional . CANSIM (database). Available at: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a01?lang=eng (Accessed 17 November 2011).

- Tiedje L.B., Schiffman R., Omar M., Wright J., Buzzitta C., McCann A. et al (2002) An ecological approach to breastfeeding. MCN. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing 27, 154–161; quiz 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M., Gardiner M. & Slater A. (2000) ‘I would rather be size 10 than have straight A's’: a focus group study of adolescent girls’ wish to be thinner. Journal of Adolescence 23, 645–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twinn S. (1998) An analysis of the effectiveness of focus groups as a method of qualitative data collection with Chinese populations in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 28, 654–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S. (1998) Focus group methodology: a review. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 1, 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow W.W., Honein G. & Elzubeir M.A. (2002) Seeking Emirati women's voices: the use of focus groups with an Arab population. Qualitative Health Research 12, 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]