Abstract

Diet and nutrition, particularly among low‐income groups, is a key public health concern in the UK. Low levels of fruit and vegetable consumption, and obesity, especially among children, have potentially severe consequences for the future health of the nation. From a public health perspective, the UK government's role is to help poorer families make informed choices within healthy frameworks for living. However, the question is – to what extent are such policies in accordance with lay experiences of managing diet and nutrition on a low‐income? This paper critically examines contemporary public health policies aimed at improving diet and nutrition, identifying the underlying theories about the influences on healthy eating in poor families, and exploring the extent to which these assumptions are based on experiential accounts. It draws on two qualitative systematic reviews – one prioritizing low‐income mothers’ accounts of ‘managing’ in poverty; and the other focusing on children's perspectives. The paper finds some common ground between policies and lay experiences, but also key divergencies. Arguably, the emphasis of public health policy on individual behaviour, coupled with an ethos of empowered consumerism, underplays material limitations on ‘healthy eating’ for low‐income mothers and children. Health policies fail to take into account the full impact of structural influences on food choices, or recognize the social and emotional factors that influence diet and nutrition. In conclusion, it is argued that while health promotion campaigns to improve low‐income families’ diets do have advantages, these are insufficient to outweigh the negative effects of poverty on nutrition.

Keywords: nutrition, low‐income, systematic reviews, policy

Introduction

Diet is a key issue for UK health policy: low levels of fruit and vegetable consumption among people in poorer socio‐economic groups are of particular concern, as are increasing levels of obesity, especially among children (Acheson 1998; Department of Health 2002a, 2002b, 2003a, 2003b, 2003c, 2004a, 2004b). Socio‐economic differences in diet and nutrition across the UK are striking. Lower‐income families, socially excluded groups, and those living in deprived areas, consume less fruit and vegetables and higher levels of fat, sugar and salt in their diets (Cooper et al. 1999; Hunt et al. 2000; Henderson et al. 2002; Department of Health 2003b). It is well documented that low‐income households face difficulties in achieving a healthy diet, including affordability and access to fresh food (Piachaud & Webb 1996; Riches 1996; Lobstein 1997; Dowler et al. 2001; Sustain 2002; National Children's Home 2004) (but see Dibsdall et al. 2003 for a counter argument). The result is that children from poorer households eat on average half as much fruit and vegetables as children from higher‐income families (Gregory et al. 2000), and are at a greater risk of obesity (Jebb et al. 2004). Recent survey evidence suggests that the last decade has seen no significant improvement in the diets of children from low‐income families (National Children's Home 2004). One explanation is simply that eating more healthily costs more. A study by the Food Commission compared the cost of a basket of regular food with that of healthier equivalents, such as low‐fat, reduced‐salt and wholegrain versions. In 2001, the Commission found that the average cost of healthier foods was 51% more than the regular items (Davey 2001). Inadequate nutrition can have long‐term negative impact on health, especially for children, and makes a major contribution to health inequalities (Department of Health 2002a).

A key goal of UK public health policy is to achieve better health for all members of society, and to narrow the health gap between social classes (Department of Health 1999). The aim is to engage everyone, both adults and children, in ‘choosing health’, and thus improve health outcomes (Department of Health 2004b). The rationale underpinning UK public health policies is that too many people, particularly the worst off in society, experience preventable illness and early death (Department of Health 1999); therefore, the government needs to intervene to support the development of healthy frameworks for living (Department of Health 2004b). According to Wanless’ (2004) report, the benefits of a population ‘fully engaged’ in promoting and protecting health would be people living longer, healthier lives, fewer working days lost, and reduced pressure on the National Health Service (NHS). Adequate diet and nutrition are seen as vital to promoting health throughout the life course (Department of Health 1999), providing protection against ‘killer diseases’ such as coronary heart disease, stroke and diabetes.

Recent years have seen the introduction of numerous government initiatives aimed at improving diet, particularly among poorer groups in society. Government strategies to improve nutrition include promoting ‘healthier choices’ of food, such as fruit and vegetables and foods low in saturated fat, sugar and salt, in line with World Health Organization guidelines (WHO 1990; Department of Health 2003a, 2004a).

For example, the NHS Plan highlighted diet and nutrition as key areas for action, and introduced the 5 a day programme, as part of a government drive to address problems in disadvantaged areas of the country, and improve children's long‐term health (Department of Health 2000). The 5 a day programme aims to increase consumption of fruit and vegetables by increasing awareness of the health benefits, and to improve the availability of fruit and vegetables (Department of Health 2003a). The programme has five main strands: The National Fruit Scheme, local 5‐a‐day initiatives, a communications programme, work with industry, and with national and local partners. The National School Fruit Scheme provides one piece of fruit a day to children in Local Education Authority maintained infant and nursery schools (Department of Health 2002b). Reforms to the Welfare Food Scheme (renamed Healthy Start) have introduced vouchers for fresh produce and milk for low‐income families (Department of Health 2004c). Other schemes aimed at improving nutrition for people living in disadvantaged areas include school breakfast clubs, neighbourhood renewal projects, Single Regeneration Budget programmes, Sure Start initiatives and Healthy Living Centres (Department of Health 2004a). Many interventions are designed to be implemented in partnership with local communities, including food cooperatives, community cafes, and ‘cook and eat’ projects (Food Matters 2003). Healthy eating is also a key theme of the National Healthy Schools Programme (Department of Health 2003a).

To what extent, however, do such policies accord with families’ own strategies for coping on low income? The aim of this paper is to explore how UK health policies conceptualize the type of issues that low‐income mothers and children see as important with regard to diet and nutrition. The paper critically analyses policies aimed at improving diet and nutrition, identifies the underlying assumptions about healthy eating in poor families, and explores the extent to which these assumptions have their foundations in experiential accounts. Evidence is drawn from two qualitative systematic reviews of studies undertaken in the UK – one prioritizing low‐income mothers’ accounts of ‘managing’ in poverty; and the other focusing on children's perspectives (Attree 2004a, 2004b, 2005a, 2005b).

The impact of socio‐economic factors on diet and nutrition is widely recognized as a risk to public health in many countries. For example, in recent years the impact of food inequality on health has been acknowledged by the World Health Organization European Office, and action taken to address the problem (WHO 2000; Dowler 2001). However, cultural and social factors mean that social groups have different priorities and ideas regarding nutrition and what constitutes a ‘healthy’ diet; the findings of UK studies are therefore limited in their transferability to other countries and cultures. Public health policies to address nutritional inequalities for low‐income groups also vary, and are not readily generalizable. A notable difference between countries, for example, is the emphasis placed on private, charitable forms of aid, such as food banks and emergency kitchens, common in the United States, Canada and parts of Europe (Dowler 2001).

Evidence from developed countries suggests, however, that there are more similarities than differences in poor households’ experiences of securing adequate food (Center on Hunger and Poverty 1999; Dowler 2001; Tomkins 2001). Reflecting the UK studies described in this paper, a Canadian ethnographic study of disadvantaged women noted the innovative strategies they used to ‘stretch’ food budgets (Travers 1996). Other studies of low‐income families found that money intended for food was often eroded on other household necessities (Hamelin et al. 1999; Tarasuk 2001). Parents were aware of nutritional messages about healthy eating, but simply unable to respond to them because they lacked the means. Again mirroring research in the UK, low‐income parents in the United States and Canada described making do with ‘skimpy meals’, or going without, in order to shield their children from poverty (Hamelin et al. 1999; Connell et al. 2005).

Research methods

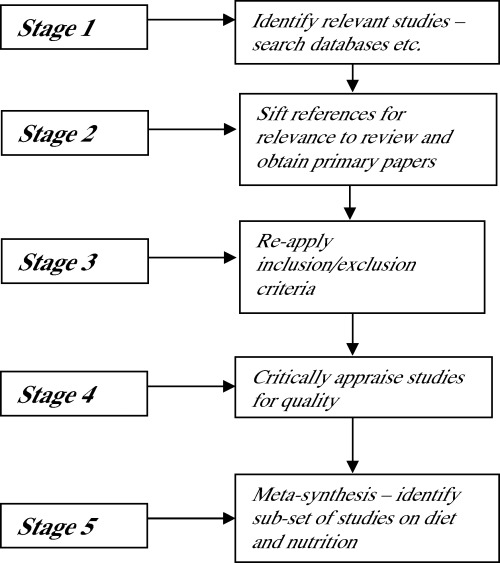

Systematic review protocols broadly followed the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2001) guidelines. The main stages of the process are outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Main stages of the systematic review process.

In stage 1 of the reviews, literature was sought through a mixture of electronic database searching, contacts with experts, website and citation searching. At stage 2, titles and abstracts were sifted for relevance to the research questions and ‘fit’ with the inclusion criteria for the review. Primary papers were then obtained and further scrutinized against the inclusion criteria (stage 3).

Studies were then appraised for quality (stage 4), using a checklist based on earlier models of assessing qualitative research (Popay et al. 1998; Seale 1999; Mays & Pope 2000; NHS CASP 2001; Spencer et al. 2003). This was divided into 10 main sections – research background, aims and objectives, study context, appropriateness of design, sampling, data collection, data analysis, reflexivity, contribution to knowledge, and research ethics – with specific questions asked of studies in each section. Two experienced qualitative researchers graded the studies for quality on a scale from A to D, initially independently, then meeting for discussion. Studies graded A to C were included in the main meta‐synthesis; those graded D were excluded. In the initial stage of the analysis, studies graded A and B were scrutinized to identify the main ideas, concepts and interpretations. When an analytical framework was established, data from grade C studies were introduced, to flesh out the conceptual categories. The evidence presented in this paper therefore is based only on research where there is a high level of confidence attached to the findings.

For each review, a meta‐synthesis of data was carried out separately (stage 5) (cf. Britten et al. 2002; Arai et al. 2003; Campbell et al. 2003; Harden et al. 2003). The term meta‐synthesis is used in its broadest sense to represent ‘a family of methodological approaches to developing new knowledge based on rigorous analysis of existing qualitative research findings’ (Thorne et al. 2004, p. 1343). Noblit & Hare's (1988) guidelines for conducting a meta‐ethnographic synthesis were used to structure the analyses. Meta‐ethnography provides an alternative to aggregative methods of synthesizing qualitative research, in which authors’ interpretations and explanations of primary data are treated as data and are translated across several studies (Britten et al. 2002; Campbell et al. 2003). The analytic steps carried out were as follows:

-

1

Reading the studies – checking for relevant metaphors, ideas, concepts and interpretations.

-

2

Identifying the relationship between studies, using lists of key metaphors, ideas and concepts arranged in matrix form.

-

3

Interpretation and translation – that is, assessing whether some concepts, metaphors and interpretations are able to encompass those of other accounts (while maintaining the integrity of individual studies).

-

4

Writing the synthesis.

(Adapted and simplified from McCormick et al. 2003, p. 939)

The process of translation entails ‘examining the key concepts in relation to others in the original study, and across studies, and is analogous to the method of constant comparison used in qualitative data analysis’ (Campbell et al. 2003, p. 673). Although the method is described in linear terms, in practice it consists of a series of overlapping stages of reading and rereading, comparing similarities and differences across studies, interpreting, recording and synthesizing findings (McCormick et al. 2003). It was at this interpretive stage of the reviews that diet and nutrition emerged as key themes.

Next, key public health documents published since 1997 were located through UK government official websites: these were Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (Department of Health 1999), Tackling Health Inequalities: A Programme for Action (Department of Health 2003c) and Choosing Health (Department of Health 2004b). Two further public consultation documents, seen as indicative of the government's approach to diet and nutrition, were also included in the analysis –Choosing Health: Choosing a Better Diet (Department of Health 2004a) and Healthy Start (Department of Health 2004c). Policy documents were examined in the light of the experiential evidence from the systematic reviews. They were read and reread to identify key themes, to explore areas of commonality, and to note disparities in approach and terminology. The assumptions underpinning policy were then compared with key findings from the systematic reviews – to identify areas where the qualitative evidence supports the government's perspectives on improving diet and nutrition, and where it runs contrary to them.

Findings

Promoting ‘healthy choices’: the role of government

What understandings of poverty, diet and nutrition, are evident in contemporary government health policies? Policy documents suggest that the role of the UK government is primarily to support people in making healthy choices, and to create the conditions for individuals to make healthy decisions (Department of Health 2004b). Supporting people in making healthy choices includes communicating the health risks of a poor diet (Department of Health 2003c), and providing practical health education and skills (Department of Health 2004b). From this perspective, the government's primary role is to facilitate increased consumer awareness and understanding of healthy food choices. Thus, an integral component of the Healthy Start scheme is the ‘added value’ of contact with health professionals for low‐income mothers, offering opportunities to provide health education (Department of Health 2004c).

Policies acknowledge constraints on choice for low‐income families, such as high prices for fresh fruit and vegetables in disadvantaged areas and ‘food deserts’ (i.e. a lack of affordable ‘healthy’ foodstuffs in poor communities) (Department of Health 1996, 1999; Policy Action Team 2000). Part of the government's role in creating the conditions for individuals to make healthy food choices therefore is to increase access to a wider range of foods and improve the availability of healthy foodstuffs in deprived areas of the country, for example, through the National School Fruit and Vegetable scheme, community initiatives such as food cooperatives, Healthy Start (reform of the Welfare Food Scheme), and transport reforms (Policy Action Team 2000; Department of Health 2002a, 2002b, 2004c).

Individual responsibility and informed choice

In contemporary policy approaches, the apparent failure of lower socio‐economic groups to adopt healthier eating practices is explained in two main ways: deficiencies in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours, and restricted access and availability of healthy foodstuffs. Poverty and social exclusion are seen as the ‘breeding ground of poor health’ (Department of Health 1999, p. 3) and thus as contributing to health inequalities; however, poor parenting and ‘risky’ behaviour, such as eating an ‘unhealthy’ diet, are also seen to influence health outcomes (Department of Health 2003c). These factors are considered amenable to change through the implementation of public health policies (Department of Health 2004b). Policy documents draw on the concept of the ‘cycle of deprivation’ (Department of Health 2003c, 2004b, 2004c), in which patterns of ill health ‘flow down the generations’ (Department of Health 1999, 3:13), to make the case that changes in attitudes and behaviour, as well as material improvements, should properly be the focus of health promotion measures. Individual behaviourist explanations therefore appear to carry greater weight in political discourses. Commentators commonly use the language of individual responsibility and informed choice (which, of course, will be a ‘healthy choice’). For example:

Individuals also have to be responsible for their own health and that of their children by making appropriate and informed lifestyle choices on smoking, diet and exercise, all of which can widen health inequalities. (Department of Health 2003c, 5:36)

The prime responsibility for improving the health of the public does not rest with the NHS nor with the Government, but with the public themselves. (John Reid, Secretary of State for Health, 3 February 2004, Department of Health 2004d, p. 7)

Policies are also informed by notions of the empowered consumer, who is (or should be) actively pursuing health as a goal. In the Choosing Health White Paper, for example, the government draws on a social marketing model to argue that:

Promoting health on the principles that commercial markets use – making it something people aspire to and making healthy choices enjoyable and convenient – will create a stronger demand for health and in turn influence industry to take more account of broader health issues in what they produce. (Department of Health 2004b, p. 20)

In the sections that follow, evidence drawn from the systematic reviews is used to explore the utility of the social marketing model in practice.

Explaining diet and nutrition in low‐income families: insights from experiential accounts

‘Strategic adjustment’ to poverty was one of the main concepts identified in the mothers’ systematic review (cf. Attree 2005b). The concept refers to the material constraints on choice that low‐income mothers experience, in particular the cutbacks in household spending on food typically associated with living in poor circumstances. The concept encompasses several factors; first ‘juggling’ household bills to make ends meet, prioritizing the purchase of certain items, such as food, rent and fuel (not necessarily in that order). Allocating money in this way was often complicated by debt repayments, however, which could leave little for necessities. For example:

. . . I only get £53 . . . all her child benefit goes on our catalogue bills . . . and I have to pay . . . gas . . . electric . . . water rates . . . I find that once I’ve bought her nappies . . . I haven’t got no money left for myself . . . I even struggle to buy dinners for myself . . . I’ve got to buy her baby food and everything. My cupboards are bare. I can’t tell you the last time I ever even bought shopping . . . I just find it really hard. (Peggy, ‘alone’ lone mother) (Dearlove 1999, p. 207, unpublished thesis)

Second, managing on a low‐income meant that mothers’ ability to buy ‘healthy’ food, such as meat, fruit and vegetables, was severely compromised. These more expensive items were therefore often cut back to make financial savings. One woman explained, for example:

We try to eat ‘proper meals’ like meat and veg. and that but there just isn’t the money to do it all the time. So we eat properly maybe once or twice a week depending on the money and the rest of the time we make do with things like sausages, pies, potatoes and things like beans. The meals aren’t as good but they do the job, they’ll fill them [children] up and stop them from being hungry, it's the best I can do. (Long‐term Income Support recipient, couple, more than one child) (Dobson et al. 1994, p. 17)

At worst, mothers’ struggle to manage on restricted budgets meant inadequate nutritional intake, poorer food variety, and less healthy dietary patterns (cf. Dowler & Calvert 1995). Many women said that they would prefer to include more fruit and vegetables in their children's diets, but were restricted by limited budgets. However, children's tastes were also a factor influencing food purchasing in poor families. For example:

With having the children, they’ve got likes and dislikes so I have to try and cater for their likes and dislikes. (Long‐term Income Support recipient, lone parent) (Dobson et al. 1994, p. 31)

Mothers’ desire to provide food familiar to children that they would eat without fuss was often driven by the need to avoid waste. Cost was again a major influencing factor.

Finally, some women shopped around for cheaper food as a way of coping on a low income. For example:

. . . yae can get 4 tins of beans in Asda for 99 pence, whereas yer like 40, 50 odd pence for one tin of beans up here. Ken [you know] that's why a lot – most – folk dae their shopping in Airth – because it's cheaper. (Focus group participant, peripheral housing estate, small de‐industrialising town in rural area) (McKendrick et al. 2003, p. 11)

The costs associated with ‘shopping around’ as a strategy tended to fall on mothers, who typically invested much time and effort in searching for food bargains. Those living in poorer areas often had problems in accessing healthy food in local shops, exacerbated by a dearth of public transport. Shopping for affordable foodstuffs was more often than not a source of stress for mothers, especially when accompanied by young children.

Walking up to the shops is nice during the summer, but if it's winter then it's just a nightmare. And it's dragging the shopping home with you that gets me sometimes. Jackie's just walking along and there's me with a bloody pushchair full, sky high with shopping and trying to push up the road. It would be nice just to dump it in the car and come home, you know. (White lone mother, on income support, caring for two children aged 5 and 3 years) (Bostock 2001, p. 14)

This finding suggests that access to affordable, healthy food in convenient locations continues to be a problem for some families in deprived areas of the UK.

Social and emotional aspects of diet and nutrition

The strategies described thus far in ‘adjusting’ to poverty in terms of household food purchasing have been mainly practical. There are social and emotional aspects to diet and nutrition in poor families, however, which are not reflected in official policies. Reading across women's accounts of ‘managing’ poverty, the concept of the ‘good’ mother emerged as important, for example (Attree 2005b). This concept relates to ‘keeping up appearances’ in public, especially for children, even if this requires a degree of self‐sacrifice (Ritchie 1990; Cohen et al. 1992; Kempson et al. 1994; Middleton et al. 1994). From women's perspectives, part of the role of a ‘good’ mother was to make sure that their children did not stand out as ‘different’ among contemporaries. Thus, providing chocolate or crisps for consumption at school, although perhaps less than ideal from a healthy eating perspective, meant that mothers could at least ensure that their children fitted in with their more affluent peers (Dobson et al. 1994).

Evidence from the mothers’ systematic review suggests that within low‐income households, children's nutritional needs often take precedence. Because it is most often women who organize household shopping and cooking (Travers 1996), it is relatively simple for them to go without food or ‘make do’ at mealtimes, so that their children have sufficient. Graham (1985), for example, describes how women practised ‘individualised consumption’, and prioritized their children's needs if money for food was tight. One mother explained:

Oh yes, I cut down myself. Sometimes if we’re running out the back end of the second week and there's not really a lot for us to eat, I’ll sort of give the kids it first and then see what's left, and we’ll have what's left. (Mother in low income, two‐parent family) (Graham 1985, p. 144)

If women were able to keep their children reasonably happy, and budget within their means, then they felt that they were coping satisfactorily as mothers. However, the economic stringencies of low income meant this was not always possible; consequently, women could feel that they had failed in one of their primary roles. For example:

I just get the kids together and say, well, I’m sorry, but this has happened, I’m afraid there’ll be no dinners this week. I try to supplement it [sandwiches] with soup or something to make it more like a meal. But there again, you see, I’m sort of getting used to doing that now, but I still feel, God, you know, I’m not fulfilling my role as a mother properly here. (Single parent) (Cohen 1991, p. 31)

‘Keeping up appearances’ was also a central theme in children's experiential accounts (Middleton et al. 1994; Daly & Leonard 2002; Ridge 2002; Attree 2004b). While in the main this theme relates primarily to physical appearance – that is, children wearing the ‘right’ kind of clothes and shoes (cf. Morrow 2001; Daly & Leonard 2002) – food, especially within schools, is an important aspect of social inclusion. Children eligible to claim free school meals may be dissuaded from doing so by the stigma attached to appearing poor, for example – which could go some way towards explaining low participation rates (Ridge 2002; Child Poverty Action Group 2005). As meals are the largest item of parental expenditure relating to children's schooling (Brunwin et al. 2004), this additional expense increases pressures on low‐income family budgets.

Discussion

To what extent therefore do policies to improve diet and nutrition in low‐income groups chime with the experiential evidence synthesized in the reviews? I would suggest that, while there are certain areas of commonality between policy assumptions and lay experiences, divergences are also apparent. First, measures which aim to increase the access and availability of healthy foodstuffs in disadvantaged areas are broadly in accord with mothers’ experiential accounts. However, those aspects of policy which emphasize increasing consumer awareness and understanding, and changing attitudes and behaviour, are more problematic.

Second, there is little evidence that low‐income mothers are ignorant of healthy food choices (although the systematic review did not specifically explore mothers’ knowledge of nutrition). The majority wanted to provide ‘healthy choices’ for their children, but felt constrained by their circumstances. This evidence is reinforced by recent surveys. For example, the Food Standards Agency (2004) found that low‐income parents had a basic knowledge about healthy eating guidelines, although they tended to group foods into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ categories (for example, cereals were broadly categorized as ‘good’, whatever their nutritional content). However, the price of healthy foods was an major factor influencing household purchasing. This study found two main factors influenced food purchasing decisions – children's preferences and cost. As the review evidence suggests, experimentation with new and unfamiliar, albeit ‘healthier’, foods is less likely if every penny has to be accounted for.

School children interviewed for a Barnardo's study, many of whom received free school meals (a proxy for low income), also had relatively clear ideas about healthy eating, although the majority failed to apply this knowledge to their own diets (Ludvigsen & Sharma 2004). Peers were a powerful influence on children's food choices, both for school meals and for packed lunches (Ludvigsen & Sharma 2004). Children also made connections between branded foods and family incomes, displaying strong pressures towards conformity. Eating ‘healthy’ food was primarily associated with affluence, and therefore seen as outside the ‘norm’ within children's peer groups. However, buying cheap branded foods was perceived as an indicator of poverty, and thus an outward sign of ‘difference’.

Third, a major difficulty is that the policy emphasis on increasing consumer awareness of healthy eating takes little account of the psychosocial and cultural aspects of food consumption, and both mothers’ and children's desire to ‘fit in’ with mainstream tastes and values. Therefore, whether a social marketing model, which emphasizes the importance of the empowered consumer, is an appropriate one to employ for health promotion initiatives among poorer groups in society is open to question.

Finally, the notion of ‘choice’ in relation to health is problematic. As Cockerham et al. (1997) point out, ‘common sense dictates that a person would choose health’ (p. 332). But attitudes to personal control over health differ fundamentally according to socio‐economic status (King's Fund 2004). The lower down the social scale the individual – the less power they feel they have to influence their health status. The ability to ‘choose health’ is constrained by life circumstances beyond the control of the individual, such as social class and status, educational and economic opportunities, gender, age, race and ethnicity (Cockerham et al. 1997; Marmot 2004). Thus:

. . . health lifestyles are patterns of voluntary health behaviour based on choices from options that are available to people according to their life situations. (Cockerham 1995, p. 90, my emphasis)

Cockerham et al. (1997) suggest that health promotion campaigns (such as the 5 a day programme) reflect fundamentally middle‐class ideas about healthy lifestyles, and attempt to apply these to the rest of society. From this perspective, health is seen as an achievement, requiring discipline and self‐control, to the extent that:

In an increasing ‘healthist’ culture, healthy behaviour has become a moral duty and illness an individual moral failing. (Crawford 1984, p. 70)

Crawford (1984) argues that health, and the pursuit of a healthy lifestyle, has taken on the character of a moral discourse through which mainstream middle‐class cultural values are disseminated and validated. He further suggests that this coexists with a oppositional discourse, which is resistant to health promotion messages, and in which ‘the cosmology of an instrumental, future‐oriented control is rejected in favour of an immediate, experiential, ethic’ (Crawford 1984, p. 85). Twenty years later, these arguments remain cogent.

Importantly, in attributing primacy to individual choice, health as moral discourse underplays the significance of structural determinants of health. The underlying influences on health are acknowledged in policy documents; for example, in the preface to the Choosing Health White Paper on public health, John Reid, the Health Secretary, remarked that ‘existing health inequalities show that opting for a healthy lifestyle is easier for some people than for others’ (Department of Health 2004b, p. 5). It is also recognized by the government that inequalities and restricted opportunities for choice are a feature of market systems. Arguably, however, public health policies attribute greater weight to modifying individual behaviour and influencing healthy lifestyle choices than to structural change (King's Fund 2004). For some low‐income mothers, faced with competing demands on restricted budgets, and influenced by the desire to ‘keep up appearances’ for their children, it remains likely that ‘choosing health is an unaffordable luxury’ (Crawford 1984, p. 69).

The arguments presented in this paper are based on systematic review evidence drawn from UK studies only; thus the extent to which they are transferable to other countries and cultures is limited. In recent years, the UK has experienced greater levels of poverty and increases in inequality than elsewhere in Europe, for example (Dowler 2001). There are differences, both in low‐income families’ experiences of diet and nutrition and policy responses, which are beyond the remit of this paper to explore. However, there are also substantial areas of commonality between poor parents in different countries in the difficulties they face in providing a healthy diet for their families (Center on Hunger and Poverty 1999; Dowler 2001; Tomkins 2001). Research concerning the impact of ‘adjusting’ to low‐income on social and emotional aspects of well‐being chimes with experiences in the UK, for example. In both Canada and the USA, studies demonstrate that food insecurity can reinforce both parents’ and children's feelings of social exclusion and powerlessness (Hamelin et al. 1999; Connell et al. 2005).

Conclusions

This paper has critically examined UK government health policy documents, with the aim of identifying the assumptions underpinning policies, and examining the extent to which these premises are grounded in low‐income mothers’ and children's experiential accounts. The role of government is seen to be twofold; first, to create the conditions for people to make healthy decisions, and second, to support individuals in making healthy choices. While the first of these two aims, creating the conditions for healthy choices, is broadly supported by research evidence, the second is more problematic. Research evidence suggests that health promotion campaigns to improve the diets of poor families, and thus reduce health inequalities, do have benefits, but these are insufficient to outweigh the effects of poverty. Thus:

Practices that encourage parents and children to eat ‘fresh, healthy food’ can make a difference, even in smokers’ families, and even on a limited budget. But they do not take away the effects of being poor: diets are worse in poorer households. . . . (Dowler & Calvert 1995, p. 4)

This paper argues that the emphasis in policy documents on individual choice, coupled with an ethos of empowered consumerism, underplays the limitations on achieving a healthy and nutritious diet experienced by low‐income households. Experiential accounts of managing in disadvantage cast doubt on the utility of adopting an individualistic model as a basis for public health policies relating to diet and nutrition. It is less a failure to apply knowledge about healthy eating, and poor attitudes, that influence diet and nutrition in low‐income families, but in the main, lack of resources. Therefore:

Dogmatic nutritional messages do not assist the disadvantaged in making reasonable and moderate choices among available alternatives, but foster a sense of inadequacy and guilt for failing to live up to the standard set by them. (Travers 1996, p. 551)

Parents’ attempts to protect their children from the impact of poverty on their diets may be undermined by benefit and tax credit entitlements that leave families living below the poverty line (Child Poverty Action Group 2005). Evidence suggests that material changes in family's circumstances such as improvements in income, if of sufficient magnitude, can have a positive effect on diet and nutrition in poor families (Farrell & O’Connor 2003). Such an approach carries broad public support. For example, in an opinion survey, 64% of respondents, and 70% of those from lower socio‐economic groups, said that tackling poverty would be the surest way to achieving a healthier nation (King's Fund 2004). From a policy perspective, placing the emphasis on measures to lift families out of poverty is essential if ‘choosing health’ is ever to be an achievable goal for all.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Department of Health National Co‐ordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development, postdoctoral training fellowship number RDO/35/21. I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Hilary Graham, now of York University, Professor Margaret Whitehead, of Liverpool University; and my co‐research fellow Beth Milton, also of Liverpool University, for their support and advice. I would also like to acknowledge members of my research advisory group at Lancaster University, for their help in discussing methodological and conceptual issues associated with this paper.

References

- Acheson D. (1998) Independent Inquiry Into Inequalities in Health Report. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Arai K., Popay J., Roen K. & Roberts H. (2003) Preventing Accidents in Children – How Can We Improve Our Understanding of What Really Works? Exploring Methodological and Practical Issues in the Systematic Review of Factors Affecting the Implementation of Child Prevention Initiatives. Health Development Agency: London. [Google Scholar]

- Attree P. (2004a) Growing up in disadvantage: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Child: Care, Health and Development 30, 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attree P. (2004b) The social costs of poverty: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Children Society 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Attree P. (2005a) Parenting support in the context of poverty: a meta‐synthesis of the qualitative evidence. Health Social Care in the Community 13, 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attree P. (2005b) Low‐income mothers, nutrition and health: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Maternal and Child Nutrition 1, 227–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock L. (2001) Pathways of disadvantage? Walking as a mode of transport among low income mothers. Health Social Care in the Community 9, 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N., Campbell R., Pope C., Donovan J. & Morgan M. (2002) Using meta ethnography to synthesis qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of Health Service Research and Policy 7, 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunwin T., Clemens S., Deakin G. & Mortimer E. (2004) The Cost of Schooling. DfES Research Report RR588. Department for Education and Skills: London. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Pound P., Pope C., Britten N., Pill R., Morgan M. et al. (2003) Evaluating meta‐ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Social Science and Medicine 56, 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Hunger and Poverty (1999) Childhood Hunger, Childhood Obesity – An Examination of the Paradox Available at: http://www.centeronhunger.org/obesity.html♯hunger (Accessed 2 January 2006).

- Child Poverty Action Group (2005) Ten Steps to a Society Free of Child Poverty. Child Poverty Action Group: London. [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham W.C. (1995) Medical Sociology, 6th edn Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham W.C., Rutten A. & Abel T. (1997) Conceptualizing contemporary health lifestyles: moving beyond Weber. Sociological Quarterly 38, 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R. (1991) ‘If you have everything secondhand, you feel secondhand’: bringing up children on income support. FSU Quarterly 46, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R., Coxall J., Craig G. & Sadiq‐Sangster A. (1992) Hardship Britain: Being Poor in the 1990s. Child Poverty Action Group: London. [Google Scholar]

- Connell C.L., Lofton K.L., Yadrick K. & Rehner T.A. (2005) Children's experiences of food insecurity can assist in understanding its effect on their well‐being. Journal of Nutrition 135, 1683–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H., Arber S., Fee L. & Ginn J. (1999) The Influence of Social Support Social Capital on Health. Health Education Authority: London. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford R. (1984) A cultural account of ‘health’: control, release, and the social body In: Issues in the Political Economy of Health Care (ed. McKinlay J.B.), pp. 60–103. Tavistock Publications: London. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M. & Leonard M. (2002) Against All Odds: Family Life on a Low Income in Ireland. Combat Poverty Agency: Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- Davey L. (OctoberDecember 2001) Healthier diets cost more than ever! Food Magazine 55, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (1996) Low Income, Food, Nutrition and Health: Report from the Nutrition Task Force. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (1999) Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2000) NHS Plan. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2002a) Five‐a‐Day Community Pilot Initiatives: Key Findings. Department of Health: London. Available at: http://www.doh.gov.uk/fiveaday (Accessed 9 June 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2002b) The National School Fruit Scheme. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2003a) A Local 5 A DAY Initiative: Increasing Fruit and Vegetable Consumption – Improving Health. Booklet 1. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2003b) Health Survey for England. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2003c) Tackling Health Inequalities: A Programme for Action. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2004a) Choosing Health: Choosing a Better Diet. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2004b) Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2004c) Healthy Start. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2004d) Choosing Health? Resource Pack. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Dibsdall L.A., Lambert N., Bobbin R.F. & Frewer L.J. (2003) Low‐income consumers’ attitudes and behaviour towards access, availability and motivation to eat fruit and vegetables. Public Health Nutrition 6, 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson B., Beardsworth A., Keil T. & Walker R. (1994) Diet, Choice and Poverty Family Policy. Studies Centre: London. [Google Scholar]

- Dowler E. (2001) Inequalities in diet and physical activity in Europe. Public Health Nutrition 4, 701–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowler E. & Calvert C. (1995) Nutrition and Diet in Lone Parent Families in London Family Policy. Studies Centre: London. [Google Scholar]

- Dowler E., Turner S. & Dobson B. (2001) Poverty Bites: Food, Health and Poor Families. Child Poverty Action Group: London. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell C. & O'Connor W. (2003) Low‐Income Families and Household Spending. Department for Work and Pensions, Research Report No. 192. Corporate Document Services: Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Food Matters (2003) Review of Existing UK Work on Food and Low‐Income Initiatives: A Report for the Food Standards Agency. Food Matters: Brighton. [Google Scholar]

- Food Standards Agency (2004) Food Promotion and Marketing to Children: Views of Low Income Consumers. Food Standards Agency: London. [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. (1985) Caring for the Family: The Report of a Study of the Organization of Health Resources and Responsibilities in 102 Families with Pre‐School Children. Health Education Council: London. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory J., Lowe S., Bates C.J., Prentice A., Jackson L.V., Smithers G. et al. (2000) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Young People Aged 4–18 Years, Vol. 1: Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin A.M., Habicht J.P. & Beaudry M. (1999) Food insecurity: consequences for the household and broader social implications. Journal of Nutrition 129, 525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden A., Oliver S., Rees R., Shepherd J., Brunton G., Garcia J. et al. (2003) A New Framework for Synthesising the Findings of Different Types of Research for Public Policy. Paper Presented at the 3rd Campbell Collaboration, Stockholm, February 2003.

- Henderson L., Gregory J. & Swan G. (2002) The National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Adults Aged 19–64 Years. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt C.T., Nichols P.N. & Pryer J.A. (2000) Who complied with the national fruit and vegetable population goals? Findings from the dietary and nutritional survey of British adults. European Journal of Public Health 10, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Jebb S.A., Rennie K.L. & Cole T.J. (2004) Prevalence of overweight and obesity among young people in Great Britain. Public Health Nutrition 7, 461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempson E., Bryson A. & Rowlingson K. (1994) Hard Times. Policy Studies Institute: London. [Google Scholar]

- King's Fund (2004) Public Attitudes to Public Health Policy King's Fund: London. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/pdf/publicattitudesreport.pdf (Accessed 24 February 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Lobstein T. (1997) If They Don’t Eat a Healthy Diet It's Their Own Fault! Myths About Food and Low Income. National Food Alliance: London. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsen A. & Sharma N. (2004) Burger Boy and Sporty Girl: Children and Young People's Attitudes Towards Food in Schools. Barnardo’s: Barkingside, Ilford. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick J., Rodney P. & Varcoe C. (2003) Reinterpretation across studies: an approach to meta‐analysis. Qualitative Health Research 13, 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendrick J.H., Cunningham‐Burley S. & Backett‐Milburn K. (2003) Life in Low Income Families in Scotland: Research Report. Scottish Executive Social Research: Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. (2004) Status Syndrome: How Our Position on the Social Gradient Affects Longevity and Health. Bloomsbury: London. [Google Scholar]

- Mays N. & Pope C. (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal 330, 50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton S., Ashworth K. & Walker R. (1994) Family Fortunes: Pressures on Parents and Children in the 1990s. Child Poverty Action Group: London. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow V. (2001) Networks and Neighbourhoods: Children's and Young People's Perspectives. Health Development Agency: London. [Google Scholar]

- National Children's Home (2004) Going Hungry: The Struggle to Eat Healthily on a Low Income. NCH: London. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2001) Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD’s: Guidance for Those Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews. NHS CRD, York University: York. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP ) (2001) Appraisal Tools for Qualitative Research. Available at: http://www.phru.org.uk~casp/resources/index.htm.

- Noblit G.W. & Hare R.D. (1988) Meta‐Ethnography: Synthesisng Qualitative Studies. Sage Publications: London. [Google Scholar]

- Piachaud D. & Webb J. (1996) The Price of Food: Missing Out on Mass Consumption. STICERD Occasional Paper 20. London School of Economics and Political Science: London. [Google Scholar]

- Policy Action Team (2000) Improving Access for People in Deprived Neighbourhoods. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Rogers A. & Williams G. (1998) Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qualitative Health Research 8, 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riches G. (1996) Hunger, Food Security and Welfare Policies: Issues and Debates in First World Societies. Paper Presented to Nutrition Society Summer Meeting, June 1996. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ridge T. (2002) Childhood Poverty Social Exclusion: From a Child's Perspective. Policy Press: Bristol. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J. (1990) Thirty Families: Their Living Standards in Unemployment. DSS Report No. 1. HMSO: London. [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. (1999) The Quality of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications: London. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L., Ritchie J., Lewis J. & Dillon L. (2003) Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. Cabinet Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Sustain (2002) Hunger from the Inside: The Food Poverty in the UK. Sustain: London. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V.S. (2001) Household food insecurity with hunger is associated with women's food intakes, health and household circumstances. Journal of Nutrition 131, 2670–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Jensen L., Kearney M.H., Noblit G. & Sandelowski M. (2004) Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qualitative Health Research 14, 1342–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins A. (2001) Vitamin and mineral nutrition for the health and development of children in Europe. Public Health Nutrition 4, 101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers K.D. (1996) The social organisation of nutritional inequities. Social Science and Medicine 43, 543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanless D. (2004) Securing Good Health for the Whole Population: Final Report. HMSO: London. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (1990) Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. WHO: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2000) The Impact of Food on Public Health. Case for a Food and Nutrition Policy and Action Plan for the WHO European region 2000–2005. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Working Draft 15 May 2000.