Abstract

Supplementation with lipid‐based nutrient supplements (LiNS) is promoted as an approach to prevent child undernutrition and growth faltering. Previous LiNS studies have not tested the effects of improving the underlying diet prior to providing LiNS. Formative research was conducted in rural Zimbabwe to develop feeding messages to improve complementary feeding with and without LiNS. Two rounds of Trials of Improved Practices were conducted with mothers of infants aged 6–12 months to assess the feasibility of improving infant diets using (1) only locally available resources and (2) locally available resources plus 20 g of LiNS as Nutributter®/day. Common feeding problems were poor dietary diversity and low energy density. Popular improved practices were to process locally available foods so that infants could swallow them and add processed local foods to enrich porridges. Consumption of beans, fruits, green leafy vegetables, and peanut/seed butters increased after counselling (P < 0.05). Intakes of energy, protein, vitamin A, folate, calcium, iron and zinc from complementary foods increased significantly after counselling with or without the provision of Nutributter (P < 0.05). Intakes of fat, folate, iron, and zinc increased only (fat) or more so (folate, iron, and zinc) with the provision of Nutributter (P < 0.05). While provision of LiNS was crucial to ensure adequate intakes of iron and zinc, educational messages that were barrier‐specific and delivered directly to mothers were crucial to improving the underlying diet.

Keywords: complementary feeding, nutrition education, ready‐to‐use therapeutic foods, food supplementation, TIPs

Introduction

The complementary feeding period, when solid foods are introduced to complement breast milk, is associated with the onset of growth faltering in resource poor countries (Shrimpton et al. 2001; Victora et al. 2010). While mothers may think they are providing more food for their children, this new diet often puts the child at risk for malnutrition for several common reasons: (1) foods lack sufficient energy and nutrient density; (2) foods displace breast milk too quickly and (3) foods when prepared, fed and stored in unsanitary conditions increase exposure to food‐borne pathogens (Brown et al. 1998). Inappropriate care practices such as poor responsive feeding, low feeding frequency and insufficient feeding during recovery from illness further augment the risk of malnutrition (Brown et al. 1998). Thus, the period of complementary feeding, usually from 6–24 months of age, also represents the optimal time for intervention (Martorell 1995). Various preventive approaches are available including processed complementary foods, education and micronutrient supplementation.

Supplementation with lipid‐based nutrient supplements (LiNS) is a promising new intervention that could overcome some of the limitations associated with other processed complementary foods (PCF) and provide benefits not found with micronutrient supplementation (Dewey & Brown 2003). LiNS are usually peanut butter mixed with milk powder, sugar and vegetable oil (Briend & Lescanne 2002). LiNS can be manufactured locally using local ingredients, with the exception of the fortificants, and do not require expensive extrusion technologies like those used in cereal/legume PCF. LiNS are also resistant to microbial growth and oxidation due to a low water activity (Dewey & Brown 2003).

LiNS evolved from ready‐to‐use therapeutic food that has been successful in treating severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and allows for home‐based treatment of SAM (Briend 2001; Ciliberto et al. 2005). However, when used in a preventive approach, LiNS has shown modest growth results. In a Ghanaian supplementation trial from 6–12 months of age, children receiving LiNS containing ∼450 kJ/day gained ∼200 g in weight and ∼0.5 cm in length more than children receiving only multiple micronutrients (Adu‐Afarwuah et al. 2007). In Malawi, children of the same age given LiNS (532–1072 kJ/day) experienced no advantage in weight or length gain compared to children receiving ∼282 g of a fortified, uncooked maize‐soy flour per day (Phuka et al. 2008). The only significant effects were a decrease in severe stunting and a greater improvement in length‐for‐age Z score in children with a low baseline value. In another study in Malawi, children from 6 to 12 months consuming 837 kJ/day of LiNS showed a significant weight increase of only 100 g compared with children consuming 837 kJ/day of a maize porridge fortified with fish powder (Lin et al. 2008).

None of these studies attempted to improve the underlying complementary diet of their infant subjects. Only the study in Ghana collected dietary intake data to compare the diets of the different intervention groups and assess replacement of complementary foods. While there was no replacement in the Ghana study, it should be noted that they instructed mothers to feed only 20 g of LiNS per day mixed into other complementary foods while the two other trials in Malawi suggested 25–50 g of LiNS/day without the recommendation to serve in other foods. How these instructions may have influenced intake of other complementary foods, and how much LiNS could improve growth combined with an improved local diet is unknown.

Our objective was to conduct two rounds of 2‐week home interventions known as Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) to inform the design of a future intervention (Dickin et al. 1997). The aim of the first round was to understand how local infant diets in rural Zimbabwe could be improved without the use of a new commodity. The aim of the second round was to introduce a LiNS, Nutributter® (NB, Nutriset, Malaunay, France), while also improving the quality of the diet with local foods.

Key messages

-

•

Studies on lipid‐based nutrient supplements (LiNS) have not tested the effects of improving the underlying diet prior to providing LiNS.

-

•

Improving feeding practices using locally available foods should be considered prior to supplementation with LiNS.

-

•

Complementary feeding messages should be context specific and target cultural feeding barriers.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted during the hungry season (between November and April) in a rural, drought‐prone district of central Zimbabwe. The major livelihoods are subsistence farming and market gardening. The diet staple is sadza, a stiff maize porridge, usually eaten with tomato and onion relish, green leafy vegetables, beans, fish or meat. During the study, non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) were distributing soap, beans, maize meal, barley and corn‐soy blend.

Enrollment

Village health workers (VHW) identified all breastfeeding mothers with 6–12‐month‐old children in their catchment area for recruitment. The list of children was divided into two groups: 6–8 months and 9–12 months. Children on the list were randomly selected for enrollment (eight per age group per round) to avoid discrimination of children based on household location (n = 32). Teams comprising a district‐level nutritionist and a VHW visited participants at home, and obtained written consent before conducting the first interview.

Preliminary work

A review of previously collected data was completed before the study to identify general infant feeding problems in rural Zimbabwe. The data included 24‐h dietary recalls, food frequencies and focus group discussion summaries. Upon arrival in the study site, research supervisors met with a local VHW to learn about locally available foods. The VHW worked with the research team to develop nutritious recipes based on those foods. The preliminary work informed the initial set of improved practices.

Trial protocol

The primary methodology used in this study was TIPs (Dickin et al. 1997). The TIPs methodology is a formative research technique recommended to identify the most acceptable and feasible improved practices to promote in a behaviour change programme (Dewey & Brown 2003). The typical TIPs protocol includes an assessment of household behaviours, negotiation to try 1–3 improved practices over 1–2 weeks and a follow‐up interview to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of the improved practices. The goal of TIPs is to narrow a potential list of practices down to the few that are the most acceptable and feasible in the population.

TIPs Round 1 without NB (non‐NB)

Five home visits were conducted with each of the 16 enrolled mothers over 12 days. On Day 1, teams conducted an initial interview to collect demographic, infant health and infant feeding behaviour information along with a 24‐h dietary recall. To estimate portion sizes in the dietary recall, mothers transferred the amount her child consumed from samples of commonly consumed foods, which were brought by the teams, to her household dishes, and the food was weighed to the nearest gram using a digital kitchen scale (Model No. HR 2385, Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). When samples were not available, mothers were asked to fill their household dishes using water with the same volume of food as the child consumed, which was then measured with standard measuring cups. The teams assessed these baseline data to identify poor feeding practices. On Day 3, a second 24‐h dietary recall was conducted, followed by a counselling session that consisted of discussing the identified feeding problems, providing recommended improved practices and negotiating with mothers to try two or three improved practices over 10 days. The nutritionist conducted the counselling session, and the VHW contributed by demonstrating the practices to the mother. On Day 5, teams conducted the first follow‐up interview and an observation of one feeding episode to verify implementation of improved practices. On Days 9 and 12, follow‐up interviews and 24‐h dietary recalls were conducted. The interviews were semi‐structured with open‐ended responses and were conducted in Shona language by bilingual nutritionists.

TIPs Round 2 with NB

A second group of 16 mothers were enrolled for Round 2. The protocol was the same as Round 1 with these exceptions: the Day 3 counselling visit included a demonstration/taste test of NB and all mothers were asked to (1) feed 4 teaspoons (∼20 g total) of NB per day (2) choose one sanitation/hygiene improved practice from the options presented and (3) choose one or two other infant feeding improved practices to reinforce the importance of continuing to improve feeding practices concomitantly with NB. Round 2 follow‐up and final interviews also included questions about NB acceptance. NB was supplied by Nutriset (Malaunay, France). The primary ingredients were peanut butter, skimmed milk powder, sugar, and oil. The NB was packaged in plastic containers with Nutriset's standard label that listed ingredients, dosage and storage conditions in English and French. The daily dose provided ∼1 day's requirement of micronutrients along with 452 kJ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nutrient composition of Nutributter

| Nutrient | Amount per 20 g |

|---|---|

| Energy, kJ | 452 |

| Protein, g | 2.56 |

| Fat, g | 7.08 |

| Calcium, mg | 100 |

| Phosphorus, mg | 82.13 |

| Potassium, mg | 152 |

| Magnesium, mg | 16 |

| Zinc, mg | 4 |

| Copper, mg | 0.2 |

| Iron, mg | 9 |

| Iodine, µg | 90 |

| Selenium, µg | 10 |

| Manganese, mg | 0.08 |

| Vitamin A, mg RE | 0.4 |

| Vitamin C, mg | 30 |

| Vitamin B1, mg | 0.3 |

| Vitamin B2, mg | 0.4 |

| Vitamin B6, mg | 0.3 |

| Vitamin B12, µg | 0.5 |

| Folic acid, µg | 80 |

| Pantothenic acid, mg | 1.8 |

| Niacin, mg | 4 |

Calculation of nutrient intake

Recipes of mixed foods were entered into Nutrisurvey (WHO). A Nutrisurvey function estimated nutrient retention of cooked foods. Some indigenous foods needed to be added to the software from a Zimbabwean composition table, a botanical reference book and published articles (Chitsiku 1991; PROTA Foundation 2005; van der Walt et al. 2009). Due to the limited number of nutrients commonly found in each of these sources, there was no way to analyze other nutrients that might be of interest such as essential fatty acids. Consumption of NB was ascertained by weighing the containers at follow‐up interviews, by asking the number of spoonfuls fed in the two, 24‐h recalls on Days 9 and 12, and by asking the mothers how often they fed Nutributter during interviews on Days 5, 9, and 12. Pre‐ and post‐counselling intakes were calculated by averaging the intakes from the 24‐h recalls on Days 1 and 3 (pre) and Days 9 and 12 (post).

Data analysis

Qualitative data

Interview responses were transcribed and labelled with codes related to acceptability and feasibility of improved practices or NB. Coded data were tabulated and summarized for emergent themes (Strauss & Corbin 1998). Pertinent quotes were selected to illustrate each theme.

Quantitative data

Data on nutrient intakes and nutrient densities were analyzed using a multi‐level model with provision of NB and time (pre‐ and post‐counselling) as fixed effects and child as a random factor. Models were adjusted for daily intake of food (g). Significant interactions with time were included. Results that were not normally distributed were log‐transformed. To assess the potential for consuming an adequate diet of complementary foods before and after counselling, energy and nutrient intakes were compared with the ‘estimated requirement from complementary food’, which was created by subtracting the amount of energy/nutrient in an average intake of breast milk (600 g for 6–8 months and 550 g for 9–11 months) from the WHO estimated energy requirement, the US recommended daily allowance for protein (RDA) and the WHO recommended nutrient intakes (RNI) for vitamins and minerals (Brown et al. 1998; FAO/WHO/UNU 2001; FAO/WHO 2002; Dewey & Brown 2003; Institute of Medicine 2005). The estimated requirement from complementary food for calcium was calculated using a recommendation between the US dietary reference intakes and the WHO RNI because of the large discrepancy between the two reference values (Abrams & Atkinson 2003). Multi‐level logistic regression using the generalized estimating equation method was similarly used to model the probability of consuming the estimated requirement from complementary food and of consuming different types of food. All children were included in the analysis (n = 32). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Means are least square means ± standard error. Analyses were done using JMP 7.0 (Cary, NC) and SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

Participants

Demographic characteristics of mothers in the non‐NB and NB TIPs were similar in most cases (Table 2). Most mothers were married and had secondary education. The majority of households had a latrine and protected water source. Most children experienced symptoms of illness in the previous 2 weeks such as cough (43.8% in both rounds) and diarrhoea (43.8% in the non‐NB round and 31.3% in the NB round).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants

| Non‐NB | NB | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 16 | 16 |

| Age group of infant – 6–8 months, n (%) | 7 (43.8) | 5 (31.3) |

| Sex of infant – male, n (%) | 8 (50.0) | 12 (75.0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married | 12 (75.0) | 11 (68.8) |

| Separated/Divorced | 1 (6.3) | 3 (18.8) |

| Single/Never Married | 3 (18.8) | 1 (6.3) |

| Widowed | 0 | 1 (6.3) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| Completed primary school | 5 (31.3) | 2 (12.5) |

| Some secondary school | 3 (18.8) | 4 (25.0) |

| Completed secondary school | 8 (50.0) | 10 (62.5) |

| No. of children caring for, mean ± SEM | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| Type of toilet, n (%) | ||

| Pit latrine | 3 (18.8) | 4 (25.0) |

| Ventilated improved pit latrine | 9 (56.2) | 5 (31.3) |

| None, Bush | 4 (25.0) | 6 (37.5) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (6.3) |

| Water source, n (%) | ||

| Protected source | 9 (56.3) | 11 (68.8) |

| Unprotected source | 7 (43.8) | 5 (31.3) |

| Morbidity in past 2 weeks, n (%) | 9 (56.3) | 13 (81.3) |

| Growth Faltering | ||

| Children with ≥1 months of static weight gain, n (%) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Children with ≥1 months of negative weight gain, n (%) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) |

| Breastfeeding frequency, mean ± SEM | ||

| Day | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 7.2 ± 0.6 |

| Night | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| No. of meals/day, mean ± SEM | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

NB, Nutributter.

Feeding and hygiene problems

The initial interviews identified 10 major feeding and hygiene problems for these mothers (supplementary Tables S1,S2). The most common feeding problem was feeding a limited variety of foods (16 infants in non‐NB; 15 infants in NB). The three foods most frequently fed to the children were porridge, sadza and sauce because the mothers believed children ‘could not chew and swallow’ other foods like vegetables, fruits and meat. Some foods were also believed to cause side effects like diarrhoea, constipation and vomiting of ‘bile.’ Low energy density of porridges was the second most common feeding problem (11 non‐NB; 6 NB) followed by low feeding frequency, low amount of food served at each meal (three non‐NB; seven NB), breastfeeds being reduced (four non‐NB; two NB) and not assisting the child when eating (one non‐NB; one NB). The common hygiene problems were not washing hands with soap and running water (6 non‐NB; 15 NB), not treating drinking water (five non‐NB; four NB), serving leftover food without reheating (six non‐NB; two NB), using a cup with a spout (two non‐NB; three NB) and poor infant stool disposal (zero non‐NB; one NB).

Improved practices suggested and tried

The improved practices given and tried most frequently corresponded with the frequency of feeding and hygiene problems (supplementary Tables S1,S2). The lack of variety in the diet was due to mothers' beliefs about children's inability to chew. Thus, improved practices focused on how to process these foods so infants could swallow them, along with motivational messages on their value for babies. In the non‐NB TIPs, we did not know which types of foods mothers would feed their children, so each recommendation mentioned only one type of food. We found that all types of foods were acceptable to mothers. Therefore in the NB TIPs, we combined the previous recommendations into a single recommendation to ‘mash and feed a variety of local foods’. Mashing fruits and vegetables were the most commonly tried recommendations for both the non‐NB and NB TIPs.

Pounding roasted pumpkin seeds or beans and adding to porridge or relish was a single recommendation in the non‐NB TIPs, but was split into two recommendations in the NB TIPs based on initial findings. Mothers served only one relish per day along with sadza, and they preferred to alternate relishes. Therefore, the recommendation to pound roasted beans into a powder was modified to ‘Make and store bean powder for the baby to add to porridge and/or relish every day.’ Thus, the emphasis was less on finding a way to process beans so they could be fed to the baby, and more on finding a way to conveniently feed beans everyday to the baby no matter what relish is prepared for the family. The result was that more mothers actually made bean powder in the NB TIPs (three in the NB TIPS vs. one in the non‐NB TIPs). Pounding roasted pumpkin seeds or dried insects was only tried in the non‐NB TIPs because none were available during the NB TIPs due to seasonality.

The most frequently suggested and tried hygiene recommendations were improved hand washing techniques (supplementary Table 2). Most mothers used still vs. running water to wash their hands; running water was perceived as necessary only when in a large group. Mothers were given three levels of recommendations with the highest being ‘use soap and running water’ when washing hands followed by ‘use ashes when soap is unavailable and running water’ and finally, ‘use running water.’ Fifty per cent or more of the women who were given these recommendations attempted using them. The other hygiene recommendations were actually tried by only one or two women during either round of TIPs.

Acceptability of improved practices

The facilitators, motivations and barriers for practicing the recommendations in both rounds of TIPs centered on four themes: (1) transformational learning, (2) maternal values, (3) resources and (4) cultural values and practices.

Gaining new knowledge through transformational learning was the most critical factor for overall acceptability. Transformational learning is defined as ‘learning that transforms problematic frames of reference to make them more inclusive, discriminating, reflective, open, and emotionally able to change’ (Mezirow 2009). Transformational learning can best be understood by distinguishing it from assimilative learning, which is taking new information and adopting it as ‘additions or extensions to existing cognitive schemes’, while transformational learning is the ‘restructuring of several cognitive as well as emotional schemes’ (Illeris 2002). The four core elements of transformational learning are a (1) disorienting experience, (2) critical reflection, (3) reflective discourse and (4) action (Merriam et al. 2006; Taylor 2009). Several quotes provide evidence that transformational learning was beginning to take place among mothers in the study. First, mothers had the disorienting experience of being counselled to process various foods they had purposefully avoided up until then (‘I was not feeding fruits such as mangoes because the baby can't chew . . . I used to caution other children not to give the baby fruits’). Second, mothers critically reflected on their previous assumptions with respect to their new knowledge when they saw that children could consume and digest these foods (‘When I grated cabbage or chopped vegetables, they did not come out like that. The baby managed to digest them.’) and (‘I saw that I had been depriving my baby of them.’). Third, mothers and family members engaged in reflective discourse with the nutritionists to understand how their old assumptions could be so different from their new knowledge (‘How did you know that these foods such as termites can be fed to babies?’). Lastly, the successful transformation of these mothers' beliefs about infant feeding led to action on their part to teach other mothers in the community without any prompting from the study team [‘I have already taught one mother on how to prepare these foods particularly preparation of mowa (amaranth) and pounding of mapudzi (pumpkin) seeds, and she liked it.’].

The one barrier to this new knowledge that affected initial acceptability was the assumption that certain foods cause side effects, such as sweet fruits causing diarrhoea and/or constipation. Only two mothers expressed this concern in the first round of TIPs, but by the second and final follow‐up they too learned this was not true because their children were happily eating them without any side effects.

Mothers valued having a healthy baby and feeding foods that their babies enjoyed and that did not cause adverse reactions. These values were the most common motivations mentioned by mothers for all improved practices, including hand washing. A few women commented positively that the improved practice caused ‘no reactions’ in their children particularly in the case of NB itself, but also with regard to mashed fruits and vegetables.

Concepts around resources included everything from food availability, time and ease of preparation. Food availability was both a facilitator and barrier for mothers' acceptance of the improved practices. Availability encompasses cost and supply because items such as cooking oil and sugar were often scarce in these rural villages, and when they were available in shops, the cost was prohibitive for many families. Mothers' said they liked these improved practices because ‘no money is required’, ‘this substitute (meaning pounded pumpkin seeds) for peanut butter is cheap and locally available’ and ‘adding custard fruit makes the porridge sweet as if I added sugar’. When asked why mothers chose the recommendations that they did, the second most common response after availability was that it was ‘easy’, meaning that the practice did not require lots of skills and was time efficient. Mothers responded similarly regarding hand washing with ashes and said things like, ‘I can try that since you can never be without ashes’.

Conversely, when foods or other resources were unavailable, mothers were prohibited from trying the recommendation or being willing to continue the recommendation on a daily basis. For instance, even though many of the mothers in the non‐NB TIPs had a supply of dried beans given to them by an NGO, they were hesitant to cook them because of a lack of firewood as one mother described, ‘The problem is that there is no readily available firewood to use for preparation of beans which takes time’. Another example is that no mothers in the NB TIPs could try the pounded seeds or pounded insects because the pumpkin harvest was poor and the insects were out of season.

Finally, cultural values and practices played a role in determining these mothers' motivations for trying and continuing these improved practices over the 2 weeks. Mothers were pleased that recommended recipes were based on foods eaten every day by their families and said things like, ‘These foods actually taste good and can be eaten by adults’. The fact that several of the foods such as the pounded seeds were once highly valued indigenous foods appealed to mothers and other family members as one grandmother explained, ‘It's good you talked about mashamba (a pumpkin variety) seeds because it was also used by our forefathers’. Some of the preliminary research uncovered the notion that during times of better economic prosperity, commercial products gained favour among younger women who started to stigmatize indigenous foods and feeding practices as primitive and antiquated (G. Mukaratirwa, personal communication).

NB acceptability

NB was acceptable to mothers and children. Most mothers thought it tasted good, and children had positive reactions such as continual licking of the spoon. During the TIPs follow‐ups, several mothers noticed that their children were eating more of their food because of the added NB and said things like, ‘I like the taste and that my baby likes it so much. This makes him eat more’. Other mothers commented that it was like a substitute for cooking oil and sugar, which are common additives to porridge. Only one infant disliked the NB.

Impact on diet

Nutrient intakes from complementary foods

Based on the 24‐h dietary recalls, intakes of energy, protein, vitamin A, folate, calcium, iron and zinc were significantly higher after TIPs counselling with or without the provision of Nutributter (Table 3). With the provision of NB, intakes of fat, folate, iron and zinc after counselling were significantly greater than post‐intakes in the non‐NB TIPs. After counselling, children were significantly more likely to meet the recommended nutrient intakes of vitamin A and calcium with or without the provision of NB (Table 4) (Dewey & Brown 2003). The probabilities of children meeting the recommended nutrient intakes for fat (based on 45% energy from fat estimates), iron and zinc only increased with the provision of NB.

Table 3.

Daily nutrient intakes and densities from complementary foods before and after counselling with and without Nutributter

| Nutrient | Factor* | Round | Pre | Post | P | Adjusted R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | ||||||

| kJ/day | 1507 ± 82.5 | 1926 ± 82.5 | <0.001 | 0.9 | ||

| kJ/100 g | NB | No | 263 ± 20.5a † | 305 ± 20.1b | 0.040 | 0.6 |

| Yes | 270 ± 20.1ab | 368 ± 20.1c | <0.010 | |||

| Protein | ||||||

| g/day | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 11.9 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 0.8 | ||

| g/100 kJ | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | NS | 0.4 | ||

| Fat | ||||||

| g/day | NB | No | 4.7 ± 0.8a | 5.7 ± 0.8a | 0.109 | 0.8 |

| Yes | 5.5 ± 0.8a | 11.3 ± 0.8b | <0.001 | |||

| g/100 kJ | NB | No | 0.4 ± 0.05a | 0.3 ± 0.05a | 0.840 | 0.8 |

| Yes | 0.4 ± 0.05a | 0.6 ± 0.05b | <0.010 | |||

| Vitamin A | ||||||

| µg RE/day | 29.0 ± 1.3 | 208 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | 0.7 | ||

| µg RE/100 kJ | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 13.0 ± 0.3 | <0.010 | 0.5 | ||

| Folate | ||||||

| µg/day | NB | No | 44.4 ± 7.0a | 74.2 ± 7.0b | 0.001 | 0.7 |

| Yes | 48.8 ± 7.0a | 106.0 ± 7.0c | <0.001 | |||

| µg/100 kJ | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 0.020 | 0.3 | ||

| Calcium | ||||||

| mg/day | 159 ± 11.4 | 209 ± 11.4 | <0.001 | 0.8 | ||

| mg/100 kJ | 11.4 ± 0.7 | 11.9 ± 0.7 | NS | 0.6 | ||

| Iron | ||||||

| mg/day | NB | No | 3.2 ± 0.5a | 4.6 ± 0.5b | 0.041 | 0.8 |

| Yes | 3.3 ± 0.5a | 10.6 ± 0.5c | <0.001 | |||

| mg/100 kJ | NB | No | 0.2 ± 0.02a | 0.2 ± 0.02a | NS | 0.6 |

| Yes | 0.2 ± 0.02a | 0.5 ± 0.02b | <0.010 | |||

| Zinc | ||||||

| mg/day | NB | No | 2.1 ± 0.2a | 2.6 ± 0.2b | 0.031 | 0.9 |

| Yes | 2.2 ± 0.2ab | 5.1 ± 0.2c | <0.001 | |||

| mg/100 kJ | NB | No | 0.1 ± 0.01a | 0.1 ± 0.01a | NS | 0.6 |

| Yes | 0.1 ± 0.01a | 0.3 ± 0.01b | <0.010 |

NB, Nutributter; NS, not significant. *Model factors which had a significant interaction with the time factor, P < 0.05. If no factor is shown, time is the only factor shown. †Means within factors with different letters are significantly different, P < 0.05. Means are least square mean ± standard error, n = 32.

Table 4.

Probabilities of consuming the estimated requirement from complementary food before and after counselling with and without Nutributter

| Nutrient | Factor* | Round | Pre | Post | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 0.830 ± 0.747 | 0.957 ± 0.839 | 0.064 | ||

| Protein | 0.973 ± 0.736 | 0.987 ± 0.825 | 0.463 | ||

| Fat † | NB | No | 0.019 ± 0.874 | 0.109 ± 0.677 | 0.273 |

| Yes | 0.024 ± 0.681 | 0.669 ± 0.653 | <0.001 | ||

| Vitamin A | 0.173 ± 0.634 | 0.895 ± 0.672 | <0.001 | ||

| Folate | 0.951 ± 0.715 | 0.980 ± 0.754 | 0.279 | ||

| Calcium | 0.584 ± 0.631 | 0.897 ± 0.680 | 0.004 | ||

| Iron | NB | No | 0.020 ± 0.842 | 0.063 ± 0.682 | 0.490 |

| Yes | 0.025 ± 0.661 | 0.854 ± 0.678 | <0.001 | ||

| Zinc | NB | No | 0.004 ± 0.889 | 0.067 ± 0.768 | 0.019 |

| Yes | 0.000 ± 0.912 | 0.990 ± 0.909 | 0.004 |

NB, Nutributter. *Model factors that had a significant interaction with the time factor, P < 0.05. If no factor is shown, time is the only factor shown. †Estimated requirement from complementary food is based on the upper limit of a 30–45% range of energy from fat (Dewey & Brown 2003). Probabilities are exponentiated least square means ± standard error, n = 32.

Nutrient density was also higher after TIPs counselling with or without provision of NB. Energy, protein, vitamin A and folate densities were increased (Table 3). Not surprisingly, the increase in energy density was even greater with the provision of NB. Densities of fat, iron and zinc were only increased when NB was provided.

Diet characteristics

The 24‐h recalls asked about breastfeeding frequency. For mothers in the non‐NB round, the point estimate of the mean breastfeeding frequency declined slightly from 10.4 ± 0.7 to 9.9 ± 0.7 breastfeeds/24‐h period. However, mothers in the NB round had a significant increase in breastfeeding frequency going from 9.9 ± 0.7 breastfeeds/24‐h period to 10.8 ± 0.7, P = 0.034. Provision of NB was nearly a significant factor in the individual change in breastfeeding frequency, P = 0.056.

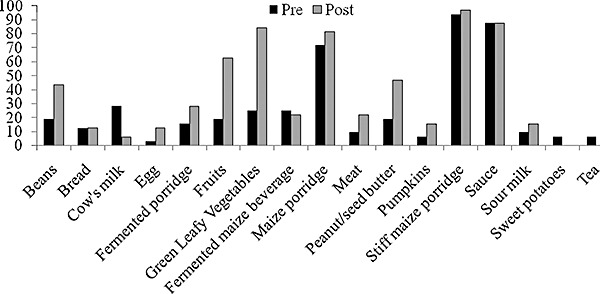

The main feeding problem, lack of dietary diversity, was reflected in the two 24‐h dietary recalls conducted prior to TIPs counselling (Fig. 1). Less than a third of mothers had fed a green leafy vegetable (GLV), fruit, beans or meat to their children. This is in contrast to staple foods like maize porridge, sadza and its accompanying sauce (cooking liquid from steamed GLV or meat with or without a tomato and onion sauce). After counselling, mothers were significantly more likely to feed beans (OR = 3.9 ± 2.5, P = 0.029), fruits (OR = 7.8 ± 4.1, P < 0.001), GLV (47.9 ± 43.7, P < 0.001) and peanut/seed butters (OR = 3.9 ± 2.3, P = 0.019). There was also a modest increase in the number of mothers who had fed meat (9.4 to 21.9%) on the previous day. There were no real changes to the numbers of women who fed maize porridge (71.9 to 81.3%), sadza (93.8 to 96.9%) or sauce (87.5 to 87.5%) to their children after counselling.

Figure 1.

Percentage of children receiving foods pre‐ and post‐counselling based on 24‐h dietary recalls. Foods fed by more than one mother are included.

The second most common feeding problem, poor energy density, was also evident in the 24‐h recalls before counselling. The majority of mothers in the non‐NB round fed thin maize porridge without any enrichment with the exception of a little cooking oil. In the NB round, fewer mothers had this problem, and this is seen in the 24‐h recalls because mothers were more likely to make thick porridges than thin (OR = 5.7 ± 5.1, P = 0.049) and fewer porridges contained no enrichments (51.4% vs. 68.6%). After counselling in both rounds, the majority of reported porridges was thick and contained some type of enrichment such as bean powder, cream, custard fruit, juice, milk, NB, peanut butter, pounded termites or pounded seeds. However, some enrichments were found in only one of the rounds. Custard fruit, juice, milk, pounded termites and pounded seeds were only in the non‐NB round. Cream and NB were only found in the NB round.

NB consumption

Based on the disappearance rate of NB, infants consumed an average 21.0 ± 1.3 g NB/day, consistent with the recommended dose of 20 g NB/day. However, the feeding frequency of NB based on the 24‐h recalls was only 2.8 ± 0.3 spoons of NB/day, less than the instructed 4 spoons. In the interviews, zero mothers reported feeding less than 4 spoons a day, and only a few mothers reported anyone other than the baby having consumed any of the NB.

Out of the food entries in the 24‐h recalls that included NB, 40% were porridge, 20% were GLV and 20% were plain NB. The rest of the entries were beans, pumpkin, sauces, mango, meat, potatoes, rice and sour milk. This order corresponds to how mothers responded in the interviews. The majority of mothers said they had tried the NB in porridge and GLV followed by feeding it plain and with pumpkin.

Discussion

Mothers were able to increase nutrient intakes from complementary foods and feeding practices of their infants with and without the provision of NB. This indicates that significant and meaningful improvements in infant diets were achieved through focused infant feeding messages based on local foods. However, NB required to reach recommended intakes of iron and zinc due to a lack of animal‐source foods in the diets.

Previous studies with LiNS conclude that in order to see even greater growth effects future studies need to use a multi‐faceted approach (i.e. provision of LiNS along with some type of disease prevention) (Lin et al. 2008; Phuka et al. 2008). While this is likely true, these comments maintain the notion that providing LiNS ‘does not require major changes to dietary practices’ in a community (Adu‐Afarwuah et al. 2008). In this acceptability study with in‐depth dietary assessment, we found no extra effect of NB on energy, protein, vitamin A or calcium intakes. However, we found improvements in energy, protein, vitamin A, folate, calcium, iron and zinc with or without the provision of NB indicating meaningful behaviour changes were brought about by the TIPs counselling. Vitamin A intake is the best example since reporting of GLV increased by a factor of 3.4 after counselling. In this context, there was a need for these dietary changes prior to introducing NB. While some have promoted the use of LiNS on the basis that mothers are unwilling to change dietary practices and sustain new ones, there is evidence for the opposite when new feeding messages are adapted from local foods and customs, and mothers are given the information directly to learn and apply for themselves (Caulfield et al. 1999; Hotz & Gibson 2005; Penny et al. 2005). Improving feeding practices can complement the provision of NB or other at‐home fortificants by optimizing the diets to which these supplements are added. Mothers will also be less reliant on the supplements and may be able to carry on if distribution of supplements is disrupted, a common worry for any programme. When there is nutritious food to be consumed such as fruits, pumpkin, GLV and insects, there is little justification for ignoring any dietary practice that prevents children from consuming them.

Another benefit of providing education in addition to NB was the variety of foods to which mothers were able to add NB. The appreciation of these Zimbabwean mothers upon learning how to prepare locally available and usual family foods for their children echoes a similar response to mothers in rural Bangladesh, who expressed disappointment in a nutrition education programme for not providing recipes that incorporated wholesome traditional family foods (Kimmons et al. 2004). Mothers here reported that when enrichments were added to their children's food, the children were inclined to eat more of that food. This statement was particularly common in the NB TIPs. While increased portion sizes were not evident in the 24‐h recall data, a longer study may detect this effect.

The lessons learned from our research highlight the need for feeding messages crafted to address the specific feeding barriers and to accommodate the available delivery system. First, we hypothesize that culturally‐specific messages about processing locally available foods may be more effective in promoting behaviour change than general messages such as those outlined in the WHO training curriculum, Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Counselling: An Integrated Course (WHO & UNICEF, 2006). For example the specific messages ‘mash mango’, ‘grind termites’ and ‘prepare bean powder’ were more helpful to mothers than the general messages such as, ‘peas, beans, lentils, and nuts and seeds, are good for children’ or ‘dark‐green leaves and yellow‐colored vegetables help the child to have healthy eyes and fewer infections’. We developed three key messages for the later intervention: (1) an infant can eat any food an adult eats; (2) grind food so that infants can swallow and digest it and (3) food that is locally available in your area is important for your baby. These messages do not have direct parallels in the WHO IYCF curriculum (although they do not contradict any messages), but were the most impactful messages from our study. A cluster‐based randomized controlled nutrition education trial in Peru came to similar conclusions when they found significantly reduced rates of stunting, improved feeding practices and increased nutrient intakes using key messages developed from their own formative research (Penny et al. 2005). The important conclusion is that general key messages, although inherently correct and comprehensive, may not impact feeding practices as much as context specific messages that are generated from formative research.

Second, mothers received the messages from local nutritionists and VHW, rather than nurses or other facility‐based workers. Community based approaches may be a more effective way of delivering messages in this type of setting. In our study, we saw a reinvigoration of VHW and a transformation among mothers as they first recognized their community's collective lack of knowledge on infant feeding, and then as they eagerly transferred their new knowledge to other community members. In Mozambique, many community health volunteers for Save the Children US, who were all mothers, maintained their involvement beyond the end of their 3‐year programme because of strong community‐based motivations, not any type of material incentive (Michaud‐Letourneua 2008). Interventions are likely to be more sustainable if the motivation for maintaining good health resides at the household and community level, and not only in the health clinic.

Breastfeeding displacement is always a concern when studies encourage increasing intake of complementary food. Drewett calculated a decrease of 239 kJ from breast milk for every increase of 419 kJ from complementary food (Drewett et al. 1993), which was the increase seen in our study. This represents a decrease of 85 g of breast milk/day, less than half of one SD of breast milk intakes in other studies (Drewett et al. 1993; Islam et al. 2008). Encouragingly, reported decline in breastfeeding frequency was small among non‐NB mothers, and NB mothers actually increased their breastfeeding frequency while concurrently improving complementary feeding practices.

There are limitations to this study that are worthy of mention. The sample size was small, but children were randomly selected from the communities and feeding observations verified the use of improved practices. An unintentional limitation was a gap in time between the first round of TIPs and the second round making the NB factor representative of a seasonal difference. Possible consequences were a different set of seasonal foods and leakage of nutritional messages, which may have caused some changes in initial dietary diversity in the second round. However, the pre‐counselling nutrient intakes did not differ greatly between the two rounds of TIPs, and in both rounds the predominate problem was lack of diversity in children's diets.

TIPs is an appropriate formative research method for developing feasible behaviour change messages. First, TIPs provides an evaluation of short‐term adoption that goes beyond initial trial/acceptance of practices such as one would assess with a taste test, recipe trial or focus group. Indeed, taste tests and recipe trials are often the only type methods used to test acceptability of processed complementary foods or improved recipes (Baskaran et al. 1999; Mensa‐Wilmot et al. 2001; Pachon et al. 2007). In a previous study in Tanzania, we found that TIPs better identified the potential impact and pitfalls of a processed complementary food intervention than a 1‐day taste test (Paul et al. 2008). Second, although this study primarily used college‐educated nutritionists to conduct the TIPs, less educated individuals with experience in fieldwork can be trained to conduct TIPs (Dickin et al. 1997). Third, the final messages developed using TIPs can then be incorporated into larger behaviour change communication programmes as appropriate for the context. The intensive visitation schedule in TIPs is to document the feasibility of these practices in daily home life and not to provide a counselling regimen that needs to be replicated in a programme. For instance, an 8‐week feasibility study for feeding expressed and heat treated (EHT) breast milk plus NB to HIV‐exposed infants used just the three final messages, and the dietary assessment showed that EHT milk and complementary foods alone were only limited in iron (45.8% RDA) and calcium (81.2% RNI) (Mbuya et al. 2010). Currently, the VHW training curriculum in Zimbabwe is being revised to include the messages developed in this formative research.

We conclude that context specific messages to improve complementary diets of infants aged 6–12 months in rural Zimbabwe can bring about substantial improvements in infant diets. However, improvements in iron and zinc intake are likely to require provision of a fortified food or point‐of‐use fortificant. Provision of barrier specific feeding messages directed at the household and community level were important to transform infant feeding practices. While NB has many advantages over other technological approaches, in contexts such as Zimbabwe where local situations may change frequently, over‐reliance on this or any commercial product (especially imports) is worthy of caution. Just as prevention of childhood malnutrition will require a multi‐faceted approach including nutrition and disease prevention strategies, nutrition interventions themselves may require a multi‐faceted approach that incorporates both technological approaches such as NB and contextually appropriate educational strategies.

Source of funding

The study was supported by the Department for International Development, UK. The sponsors of this study had no role in study design, data collection, or writing of this report.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Identified feeding problems and improved practices suggested and tried.

Table S2. Identified sanitation/hygiene problems, suggested improved practices, and tried improved practices.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

The study was approved by the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe and the Institutional Review Boards of Research Institute of McGill University Health Centres, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Cornell University. We thank the District Nutritionists and Village Health Workers from the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare and the staff of ZVITAMBO for their contribution to the data collection. We also thank Dr. Rosemary Caffarella for her guidance on adult learning.

References

- Abrams S.A. & Atkinson S.A. (2003) Calcium, magnesium, phosphorus and vitamin D fortification of complementary foods. The Journal of Nutrition 133, 2994S–2999S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adu‐Afarwuah S., Lartey A., Brown K.H., Zlotkin S., Briend A. & Dewey K.G. (2007) Randomized comparison of 3 types of micronutrient supplements for home fortification of complementary foods in Ghana: effects on growth and motor development. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86, 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adu‐Afarwuah S., Lartey A., Brown K.H., Zlotkin S., Briend A. & Dewey K.G. (2008) Home fortification of complementary foods with micronutrient supplements is well accepted and has positive effects on infant iron status in Ghana. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 87, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran V., Mahadevamma S., Malleshi N.G., Shankara R. & Lokesh B.R. (1999) Acceptability of supplementary foods based on popped cereals and legumes suitable for rural mothers and children. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 53, 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briend A. (2001) Highly nutrient‐dense spreads: a new approach to delivering multiple micronutrients to high‐risk groups. British Journal of Nutrition 85, S175–S179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briend A. & Lescanne M. Food or nutritional supplement, preparation method and uses. Patent 6,346,284. 12 February 2002.

- Brown K.H., Dewey K.G., Allen L. & World Health Organization (1998) Complementary Feeding of Young Children in Developing Countries: A Review of Current Scientific Knowledge. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield L.E., Huffman S.L. & Piwoz E.G. (1999) Interventions to improve intake of complementary foods by infants 6 to 12 months of age in developing countries: Impact on growth and on the prevalence of malnutrition and potential contribution to child survival. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 20, 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chitsiku I.C. (1991) Nutritive Value of Foods of Zimbabwe. University of Zimbabwe Publications: Harare, Zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto M.A., Sandige H., Ndekha M.J., Ashorn P., Briend A., Ciliberto H.M. et al (2005) Comparison of home‐based therapy with ready‐to‐use therapeutic food with standard therapy in the treatment of malnourished Malawian children: a controlled, clinical effectiveness trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 81, 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey K.G. & Brown K.H. (2003) Update on technical issues concerning complementary feeding of young children in developing countries and implications for intervention programs. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 24, 5–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickin K., Griffiths M. & Piwoz E.G. (1997) Designing by Dialogue: A Program Planners Guide for Consultative Research for Improving Young Child Feeding. Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Drewett R., Amatayakul K., Wongsawasdii L., Mangklabruks A., Ruckpaopunt S., Ruangyuttikarn C. et al (1993) Nursing frequency and the energy intake from breast milk and supplementary food in a rural Thai population: a longitudinal study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 47, 880–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO (2002) Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO/UNU (2001) Human Energy Requirements. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Hotz C. & Gibson R.S. (2005) Participatory nutrition education and adoption of new feeding practices are associated with improved adequacy of complementary diets among rural Malawian children: a pilot study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 59, 226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illeris K. (2002) The Three Dimensions of Learning: Contemporary Learning Theory in the Tension field between the Cognitive, The Emotional and the Social. Roskilde University Press: Roskilde. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2005) Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. National Academy Press: Washington, DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.M., Khatun M., Peerson J.M., Ahmed T., Mollah M.A., Dewey K.G. et al (2008) Effects of energy density and feeding frequency of complementary foods on total daily energy intakes and consumption of breast milk by healthy breastfed Bangladeshi children. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 88, 84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmons J.E., Dewey K.G., Haque E., Chakraborty J., Osendarp S.J. & Brown K.H. (2004) Behavior‐change trials to assess the feasibility of improving complementary feeding practices and micronutrient intake of infants in rural Bangladesh. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 25, 228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.A., Manary M.J., Maleta K., Briend A. & Ashorn P. (2008) An energy‐dense complementary food is associated with a modest increase in weight gain when compared with a fortified porridge in Malawian children aged 6–18 months. The Journal of Nutrition 138, 593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell R. (1995) The effects of improved nutrition in early childhood: the Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP) follow‐up study. The Journal of Nutrition 125, 1027S–1138S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuya M.N.N., Humphrey J.H., Majo F., Chasekwa B., Jenkins A., Israel‐Ballard K. et al (2010) Heat treatment of expressed breast milk is a feasible option for feeding HIV‐exposed, uninfected children after 6 months of age in rural Zimbabwe. The Journal of Nutrition 140, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensa‐Wilmot Y., Phillips R.D. & Sefa‐Dedeh S. (2001) Acceptability of extrusion cooked cereal/legume weaning food supplements to Ghanaian mothers. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 52, 83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S.B., Caffarella R.S. & Baumgartner L. (2006) Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. Jossey‐Bass: San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (2009) Transformative learning theory In: Transformative Learning in Practice (eds Mezirow J., Taylor E.W. & Associates ), p. 22 Jossey‐Bass: San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud‐Letourneua I. (2008) Motivations of community volunteers in Northern Mozambique: food security program, save the children. Masters Thesis, p. 18 University of North Carolina‐Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Pachon H., Dominguez M.R.L., Creed‐Kanashiro H. & Stoltzfus R.J. (2007) Acceptability and safety of novel infant porridges containing lyophilized meat powder and iron‐fortified wheat flour. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 28, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul K.H., Dickin K.L., Ali N.S., Monterrosa E.C. & Stoltzfus R.J. (2008) Soy‐ and rice‐based processed complementary food increases nutrient intakes in infants and is equally acceptable with or without added milk powder. The Journal of Nutrition 138, 1963–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny M.E., Creed‐Kanashiro H.M., Robert R.C., Narro M.R., Caulfield L.E. & Black R.E. (2005) Effectiveness of an educational intervention delivered through the health services to improve nutrition in young children: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuka J.C., Maleta K., Thakwalakwa C., Cheung Y.B., Briend A., Manary M.J. et al (2008) Complementary feeding with fortified spread and incidence of severe stunting in 6‐ to 18‐month‐old rural Malawians. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 162, 619–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROTA Foundation (2005) Plant Resources of Tropical Africa PROTA. Prota: Wageningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Shrimpton R., Victora C.G., de Onis M., Lima R.C., Blossner M. & Clugston G. (2001) Worldwide timing of growth faltering: implications for nutritional interventions. Pediatrics 107, E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A.L. & Corbin J.M. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.W. (2009) Fostering transformative learning In: Transformative Learning in Practice (eds Mezirow J., Taylor E.W. & Associates ), p. 4 Jossey‐Bass: San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt A.M., Ibrahim M.I., Bezuidenhout C.C. & Loots du T. (2009) Linolenic acid and folate in wild‐growing African dark leafy vegetables (morogo). Public Health Nutrition 12, 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora C.G., de Onis M., Hallal P.C., Blossner M. & Shrimpton R. (2010) Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics 125, e473–e480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO & UNICEF (2006) Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling: An Integrated Course. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Identified feeding problems and improved practices suggested and tried.

Table S2. Identified sanitation/hygiene problems, suggested improved practices, and tried improved practices.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item