Abstract

Growing acceptance that measurable improvements in public health, particularly in lower‐income groups, could be achieved by increasing the incidence of breastfeeding has focused attention on the current lack of educational provision in breastfeeding issues for many health professionals. An audit of general practitioners in one area of northern England revealed an interest in receiving breastfeeding training. Department of Health funding was obtained by the breastfeeding subgroup of the local Maternity Services Liaison Committee to develop, deliver and evaluate a practice‐based educational session supplemented by a resource pack. Over a 12‐month period, 22 practices received the session and the project was evaluated using an illuminative evaluation model. Response rates to two evaluation questionnaires of 81% (133/164) and 62.5% (65/104) were achieved and findings indicated high levels of satisfaction with the session and its accompanying resource pack. Qualitative data related to perceived influence on future practice were subjected to thematic network analysis and revealed four main (organizing) themes: the acquisition of greater knowledge, improved access to resources, a proactive approach to breastfeeding support and the creation of a breastfeeding‐friendly environment. The illuminative evaluation also identified recurring issues that could impact on any attempt to replicate or adapt this project; these were the influence of personal breastfeeding experiences, the desire for greater interaction during the training session and the wider implications for practice education of multidisciplinary attendance.

Keywords: breastfeeding, general practitioner, training, illuminative evaluation

Introduction

There is now an extensive body of research evidence demonstrating a range of positive health outcomes for both breastfed infants and their mothers (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 2004). Consequently, increasing the initiation and duration of breastfeeding is seen as a means of achieving improvements in public health in the UK, particularly in relation to cardiovascular disease, some cancers and obesity (Fewtrell 2004). Lack of breastfeeding is thought to be a contributory factor to the inequalities in health that exist between the various socio‐economic groups. Only 59% of mothers classified into lower socio‐economic occupational groups by the UK Office of National Statistics commence breastfeeding compared to 80% of those in the higher socio‐economic occupational groups. Lower educational attainment is also associated with a reduced likelihood of breastfeeding (Hamlyn et al. 2002). A commitment to increase support for breastfeeding by 2004 as part of a proposed strategy to improve diet and nutrition was contained within the National Health Service Plan (DH 2000). However, the NHS Priorities and Planning Framework 2003–2006 more specifically requires that all strategic health authorities and Trusts ‘deliver an increase of 2% points per year in breastfeeding initiation rates, focusing especially on women from disadvantaged groups’ (DH 2002, p. 20).

Therefore, there is currently considerable interest from health professionals in finding innovative and effective ways of facilitating increases in breastfeeding rates. However, Hoddinott & Pill (1999) have postulated that social and cultural factors, in particular embodied experiences of breastfeeding, have a greater influence on the decision to initiate breastfeeding than do educational messages and interventions by health professionals. Nevertheless, there is also evidence that women from low‐income groups, in particular, value the advice and support of knowledgeable health professionals (Raisler 2000). Bowes & Domokos (1998) suggest that this may be attributable to these mothers being less able to access information from family and friends, because breastfeeding has been a minority pursuit within their communities for many years.

It would seem essential therefore that health professionals are equipped with the necessary breastfeeding knowledge and skills to provide such support. Whilst midwives and health visitors hold the major responsibility for the promotion and support of breastfeeding, it has been recommended that all healthcare workers in contact with breastfeeding women should receive training in breastfeeding issues at levels appropriate to their needs (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative 2002). The need for such comprehensive provision is also endorsed by the WHO's (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding and the European Commission's (2004) Blueprint for Action to ensure that breastfeeding women can readily access professional support that is free from ill‐informed and conflicting advice.

In order to increase local support for breastfeeding and complement existing training packages for midwives and health visitors, a health authority in the north of England identified a need to provide breastfeeding education for general practitioners (GPs) and other members of the practice team. The potential role of GPs in the support of breastfeeding has been highlighted by Thorley (2000), but their apparent lack of breastfeeding knowledge, as identified by Hyde (1994) and Robertson & Goddard (1997), is clearly a barrier. The benefits of breastfeeding education for doctors have been illustrated by Taveras et al. (2003) who found that US mothers who received positive encouragement to breastfeed from their doctors were more likely to continue to breastfeed beyond 12 weeks. Labarere et al. (2005) similarly found that an early postnatal preventative visit by a trained primary care physician improved breastfeeding outcomes in a group of French mothers. It is acknowledged that differences in healthcare systems must be taken into account when applying these findings to the UK, nevertheless it would seem difficult to argue that GPs should not be aware of, and able to endorse, the evidence‐based breastfeeding information and support provided by other healthcare workers.

The audit department of the health authority, with the assistance of the Breastfeeding Subgroup of the local Maternity Services Liaison Committee (MSLC), conducted an audit to identify the perceived breastfeeding learning needs of local GPs. GPs were paid £10 to complete a postal questionnaire, and 52% (128) GPs representing 51 practices (57%) responded. Twenty‐eight per cent (36) reported feeling inadequately informed about breastfeeding problems, in particular insufficient milk syndrome, and 32 practices expressed an interest in receiving breastfeeding training. The MSLC Breastfeeding Subgroup undertook to develop and deliver an educational package, based on the audit findings, and obtained funding for a 12‐month period from the Department of Health Infant Feeding Initiative Breastfeeding Projects Fund. The money remaining from the audit was used to reward participating practices.

Methods

Development of educational package

A multidisciplinary project team was formed comprising a tutor from the Breastfeeding Network (BfN, a voluntary breastfeeding support organization), a midwife employed as an infant feeding specialist and a health visitor who was also a BfN supporter. It proved impossible to secure the involvement of a GP. Support and advice with the evaluation strategy was obtained from the local university.

A literature search and contact with domain experts at this time failed to reveal any training packages specifically targeted to the needs of general practice in the UK. In addition, it appeared that attempts to obtain GP participation in existing local and national breastfeeding management training courses had been largely unsuccessful.

Recognizing that this might reflect the limited time GPs would be willing or able to devote to breastfeeding education, the project team decided that the educational package should comprise an hour‐long Powerpoint presentation delivered on practice premises and supplemented by a comprehensive resource pack that would be retained by the practice. A session of this length could easily be delivered within a lunch break or any other convenient slot in a practice's working day.

The presentation (Table 1) highlighted the importance of breastfeeding to public health and drew attention to local breastfeeding rates of below the national average. In addition, the evidence‐based management of three common breastfeeding difficulties was discussed. Two of the topics, insufficient milk syndrome and thrush infection, had been identified by the GPs at audit as of particular interest; whilst the third, mastitis, was included because calls to a local breastfeeding telephone helpline showed it still to be the subject of much conflicting advice. In conclusion, simple, low‐cost ways in which general practices could enhance their support for breastfeeding women were identified, for example, the display of a poster welcoming breastfeeding on practice premises and the dissemination of information about local sources of breastfeeding advice and support.

Table 1.

Programme outline

| 1. Introduction |

| Aims and objectives of programme |

| Breastfeeding as a public health issue |

| Local and national trends |

| 2. Recent developments in breastfeeding management |

| The critical importance of positioning and attachment |

| Nipple pain/soreness |

| Thrush |

| Mastitis |

| Insufficient milk |

| 3. Sources of breastfeeding information, support and referral in the local area |

| 4. Role of general practice in supporting breastfeeding |

| 5. Open forum and evaluation |

A lecture format was deliberately selected for the presentation as, when there are time constraints, this teaching method is thought to be a particularly effective means of transmitting information (Bligh 1998). It was hoped that the use of Powerpoint illustrations and a team teaching approach would provide sufficiently varied auditory and visual stimulation to maintain the attentiveness of listeners. Sharing the delivery of the presentation between all three members of the project team would also provide a range of expertise and demonstrate multi‐agency cooperation. Approval for the project was gained from the Local Research Ethics Committee. Participant autonomy and confidentiality were protected to throughout the project by the use of code numbers and following UK research governance principles. Postgraduate Education Approval (PGEA) was also obtained for the session.

The presentation and resource pack were piloted with three practices with 31 practice members attending, including GPs, health visitors, midwives and receptionists. Responses from the participants were overwhelmingly positive and only minor amendments to the presentation were required. Most importantly, the participants agreed the relevance and benefits of inviting all members of the practice team to participate, despite the medical emphasis of a large proportion of the session. The contents of the resource pack were finalized from the recommendations of the pilot study participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Contents of resource pack

| Breastfeeding Answerbook (1997) La Leche League International, Illinois |

| Medications and mothers’ milk (2001) T.Hale, Pharmasoft Publications |

| Implementing the Baby Friendly best practice standards (2001) UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative, London |

| Having it all: a woman's guide to combining breastfeeding and work (2001) Maternity Alliance, London |

| Breastfeeding twins, triplets or more (2000) TAMBA, Winston & Co, London |

| Thrush and Breastfeeding (1999) Breastfeeding Network, Paisley, Scotland |

| Mastitis and Breastfeeding (1999) Breastfeeding Network, Paisley, Scotland |

| Feeding your new baby, UNICEF UK BFI, London |

| Feeding your new baby, Gujarati translation, UNICEF UK BFI, London |

| Breastfeeding Your Baby, UNICEF UK BFI, London |

| Breastfeeding Your Baby, Gujarati translation, UNICEF UK BFI, London |

| Sharing a bed with your baby, UNICEF UK BFI, London |

| Information sheets |

| Additional benefits of breastfeeding |

| Risks of formula feeding |

| Assessing positioning and attachment |

| Local and national sources of breastfeeding support |

| Breast pump hire |

| Breastfeeding websites |

| Breastfeeding and thrush |

| Insufficient milk |

| Planning to breastfeed and return to work |

| Breastfeeding and work – legal rights |

| Introducing solids |

| Training opportunities |

| Poster: You are welcome to breastfeed here |

| Flyers: local breastfeeding groups |

| Order forms |

Delivery of educational session

Within the funding period of 12 months, 22 practices received the educational session. Attendances varied from 1 to 24, with an average attendance of 8. At least one GP was present at each session, but beyond this, the range of different personnel attending varied considerably from practice to practice.

The presentation consistently occupied 45–50 min of the allotted session time and thus, on most occasions, a minimum of 10 min was available for discussion. A record was made of topics discussed and questions raised at each session for evaluation purposes. At the close of each session, participants were asked to complete evaluation questionnaires (Questionnaire 1) and were then provided with attendance certificates for Personal Development portfolios.

The second evaluation questionnaire (Questionnaire 2) was sent to each participant of the first 15 sessions, with a reply‐paid envelope, approximately 3 months after their practice's session. The time interval and the limited number of practices surveyed were dictated by the funding period of 12 months.

Further details of the session delivery are recorded in Table 3, with particular emphasis on practical difficulties encountered and the means by which they were resolved.

Table 3.

Practical aspects of educational session delivery

| Aspect | Difficulty experienced | Addressed by: |

|---|---|---|

| Arranging session | Poor response to written invitation to participate | Telephone contact by project team |

| Venue | Limited space & facilities within some practice premises | Ensuring only essential requirement for session was blank wall for data projection |

| Timing | Hard to assemble all participants to start session promptly and avoid overrunning | Limiting questions to end of session. Questionnaire 1 returned by post where participant needed to leave before conclusion |

| Multidisciplinary attendance | Variations in understanding of ‘practice team’ leading to attendance by health professionals only at some practices | Invitation to all members of practice extended verbally & in writing. Advertising flyers also provided. Compulsory attendance not sought (except for GPs wishing to receive payment) |

GP, general practitioner.

Evaluation strategy

The choice of an appropriate evaluation methodology was guided by examination of the literature relating to educational evaluation. The innovative nature of the project, the desire to allow the intervention to develop during its delivery and the difficulty of achieving clearly measurable outcomes in the short term suggested that a qualitative methodology would be appropriate. Descriptive methodologies, in particular, can assist other workers to replicate or adapt interventions to fit their own circumstances. After consideration of various alternatives, an illuminative evaluation model (Parlett & Hamilton 1987) was adopted. This model requires an examination of the learning system, i.e. methods and content of the update session, and also of the learning milieu, i.e. the context of the intervention and the perspectives of the participants. Several of these aspects have been described and discussed within the earlier part of this paper. The perspectives of the participants were elicited using the two questionnaires described above. It was thought that the use of questionnaires would not only allow all participants who wished to contribute to do so, but also offer the opportunity to provide quantitative data which might have greater impact in any future search for funding to continue the project than would purely qualitative data. The combining of qualitative and quantitative methods within an evaluation study is increasingly common as researchers argue that methodological purism has the potential to ‘stifle creativity and innovation in evaluation research’ (Cook & Reichardt 1979) and so advocate that methods should be synthesized in a way that best serves the particular requirements of each evaluation (Murphy et al. 1998). The before and after assessment of breastfeeding rates that might seem the most obvious means of evaluation not only was impossible within the short period of the project but would have been influenced by other initiatives taking place in the area. It is acknowledged therefore that the evaluation cannot provide firm evidence of change in practice and is limited to assessments of the acceptability of this educational approach and the achievement of increased breastfeeding awareness.

Questionnaires were completed voluntarily and anonymously, although participants were asked to identify the professional group to which they belonged. In addition, the final results were merged across all the practices so that potential bias, for example due to hierarchical influences in an individual practice, was minimized. The design of both questionnaires was guided by the recommendations of Oppenheim (1992) to ensure ease of use and hence the maximum response rate and the reduction of potential bias. A variety of question formats was employed with responses recorded using tick boxes and summated rating scales, but some open questions were also included to provide richer data that could be subjected to content analysis.

Questionnaire 1 sought to establish whether the presentation had provided new and useful information that might influence future practice. It also aimed to assess levels of satisfaction with the venue and length of the session and to elicit comments on the value of multidisciplinary attendance. Questionnaire 2 focused on usage of the resource pack and whether participants felt that their practice had been influenced by the presentation.

Results

Questionnaire 1

An overall response rate of 81% (133/164) was achieved (Table 4), with 90% of GPs (35/39) completing questionnaires. The high response rate from this professional group is considered sufficient to enable confident assessment of their views (St Leger et al. 1997). The main reason for non‐completion of questionnaires was early departure from the session due to the need to attend clinics or other appointments.

Table 4.

Questionnaire response rates according to professional group

| Professional group | Questionnaire 1 Responses/attendance no. (%) | Questionnaire 2 Responses/no. sampled (%) |

|---|---|---|

| General practitioners | 35/39 (90) | 21/25 (84) |

| Health visitors | 26/30 (87) | 17/23 (74) |

| Community midwives | 12/18 (67) | 8/13 (62) |

| Practice nurses | 18/20 (90) | 5/13 (38) |

| District nurses | 6/6 (100) | 0 |

| Nursery nurses | 2/2 (100) | 1/1 (100) |

| Speech therapist | 1/1 (100) | 0 |

| La Leche League breastfeeding counsellor | 1/1 (100) | 0 |

| Sure Start managers & family support workers | 4/7 (57) | 0 |

| Practice managers | 7/10 (70) | 5/10 (50) |

| Reception & clerical staff | 21/30 (70) | 8/19 (42) |

| Total | 133/164 (81) | 65/104 (62.5) |

Participants were asked to specify which topics within the session contained new information relevant to their needs. As anticipated, the GPs were the professional group least knowledgeable about breastfeeding issues (Table 5). In particular, many GPs (77.1%) were not fully aware of the current thinking about thrush infection and over 50% appeared not to have considered the potential of their role in the promotion and support of breastfeeding. The length of the session was generally considered to be about right and the convenience of practice‐based delivery was rated highly. There was also a clear majority (67%; n = 89) in favour of all practice‐attached staff being made aware of the support needs of breastfeeding mothers, although 16 of the 25 sessions were attended by health professionals only. Therefore, it may be more accurate to conclude that, whilst participants generally thought it beneficial for all health professionals to attend the session, there was less consensus about the attendance of administrative staff. Midwives and health visitors appeared to be of the opinion that administrative staff should be included, whereas the doctors were less convinced of the need for their attendance. Indeed, whilst some of the administrative staff were very enthusiastic, and in a number of instances had requested to attend, others clearly felt the session to be irrelevant to them.

Table 5.

Topics containing new and relevant information

| Professional group | Topic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding as a public health issue no. (%) | Mastitis no. (%) | Thrush no. (%) | Insufficient milk no. (%) | Role of general practice no. (%) | |

| GP n = 39 | 17 (49) | 15 (43) | 27 (77) | 18 (51) | 19 (54) |

| HV n = 26 | 5 (19) | 4 (15) | 7 (27) | 8 (31) | 7 (27) |

| Midwives n = 12 | 1 (8) | 5 (42) | 8 (67) | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| Other nurses n = 26 | 12 (46) | 10 (39) | 13 (50) | 14 (54) | 13 (50) |

| Others n = 34 | 21 (62) | 25 (74) | 25 (74) | 24 (71) | 18 (53) |

GP, general practitioner; HV, health visitor.

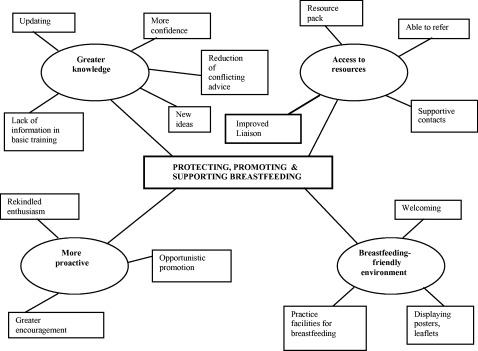

The qualitative data elicited when respondents were asked to describe how they anticipated their approach might be altered were combined with relevant data from field notes, and subjected to thematic analysis. The results of this analysis are presented as a thematic network (Attride‐Stirling 2001); whereby the lowest order themes evident in the text (Base Themes) are extracted and grouped together in categories that summarize more abstract principles. Each of these categories is described as an Organizing Theme and, collectively, these are examined to determine a superordinate or Global Theme. The result is a web‐like map (Fig. 1) that clearly illustrates the relationships between the three thematic levels. The Global Theme that emerged is best described using the words of the joint World Health Organization and UNICEF statement: Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding: the special role of the maternity services (WHO 1990).

Figure 1.

Thematic network: influence of session on participants’ approach to breastfeeding women.

A. Greater knowledge

Many of the participants commented that their increased knowledge would give them more confidence to advise breastfeeding women and that the support they could offer would be enhanced by new ideas. The updated information would also reduce the incidence of conflicting advice, particularly in the management of thrush and mastitis. A newly qualified doctor commented on how limited the information about these topics had been within her undergraduate medical degree.

B. More proactive

The session was said to have rekindled one participant's enthusiasm for promoting breastfeeding and reminded another that the many benefits of breastfeeding warranted more active promotion, whilst more than one participant made a commitment to employ an opportunistic approach to breastfeeding promotion. Many of the participants stated an intention to give greater encouragement to women, both to initiate breastfeeding and to persevere in the face of any difficulties.

C. Access to resources

Participants felt more aware of local resources and supportive contacts to whom mothers could be referred. At some practices, there had been little liaison between community midwives and health visitors and the session had provided an apparently welcome opportunity to meet and confer. In addition, the resource pack would provide practice staff with ready access to up‐to‐date reference material to enable appropriate advice and information to be given promptly.

D. Breastfeeding‐friendly environment

The importance of a welcoming environment was acknowledged and also the ease with which this could be provided. A commitment was made by some practices to display relevant posters and leaflets and also to seek to provide facilities for women wishing to breastfeed on practice premises. Others simply said they would be more helpful.

Very few suggestions were made for the improvement of the session, but those that occurred most frequently were the inclusion of more opportunities for interaction and discussion (n = 4) and an increase in the information content about effective positioning and attachment (n = 7). In general the comments about the session were very favourable and included remarks such as ‘well‐presented’, ‘comprehensive’ and ‘useful’. Although comments on the resource pack were not sought specifically at this stage, both written and verbal feedback indicated that the provision of the pack was seen as particularly valuable.

Questionnaire 2

A total of 104 questionnaires were despatched with reply‐paid envelopes and a response rate of 62.5% was achieved. There were marked differences in response rates between different professional groups (Table 4).

The programme was primarily designed to meet the needs of GPs and their high response rate three months after the event lends credibility to the evaluation findings. It should also be recognized that, as many were working in areas with a low incidence of breastfeeding, their opportunities to assess the influence of the session or to use the resource pack would have been limited within such a short period. Nevertheless, 67% (14) of the GP respondents considered that that the session had had a positive impact, reporting that they were now more supportive and proactive in encouraging mothers to initiate or continue exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months (WHO, 2003). They felt more able to give detailed information, were less ready to prescribe antibiotics and, in one practice, the support of breastfeeding had become an integral part of efforts to reduce child obesity and diabetes. Although 14% (3) were unsure whether the session had influenced their practice, 19% were certain that they had not altered their practice but explained this by saying they were already well informed and supportive.

Usage of the resource pack (Table 6) by over 44% of doctors was greater than anticipated in the relatively short period since the session and all reported finding the information they were seeking. Health visitors had made most use of the resource pack as, perhaps, might have been expected as they, and community midwives, are the professional groups that will have most contact with breastfeeding women. The community midwives were more likely to access information at their base hospitals. A number of health visitors and midwives felt that the resource packs should be made more widely available and be located at local clinics as well as at GP surgeries. This was the only suggestion made for improvement of the pack. Respondents were invited to make further comments about the session and the most frequently recurring theme was the usefulness of both the session and the resource pack. The only negative response was from a receptionist who still felt that her attendance at the session had been unnecessary:

Table 6.

Usage of resource pack

| Professional group | Usage of resource pack | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not used (%) | One occasion (%) | More than one occasion (%) | |

| GP n = 21 | 12 (57) | 4 (19) | 5 (24) |

| Health visitor n = 17 | 3 (18) | 4 (24) | 10 (59) |

| Community MW n = 8 | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | 0 |

| Practice nurse n = 5 | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | 0 |

| Nursery nurse n = 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Practice manager n = 5 | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| Receptionist n = 8 | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | 0 |

GP, general practitioner; MW, midwifery.

-

•

‘Very useful and informative session’– GP

-

•

‘Keep promoting this work’ and ‘Need sessions more regularly’– Health visitor

-

•

‘Invaluable update’– Midwife

-

•

‘Brilliant information’– Practice nurse

-

•

‘Gave me a new approach and knowledge’– Receptionist

Recurring issues identified from evaluation data

The final stage of an illuminative evaluation study is described by Parlett & Hamilton (1987) as the phase in which the evaluator seeks to identify or explain general principles underlying her findings. These principles can then inform future developments or improvements in a programme.

Reflection on the experiences of developing and implementing this programme combined with the analysis of questionnaire and discussion data revealed the following recurring issues:

-

•

The influence of personal breastfeeding experiences;

-

•

The identified desire (need) for greater interaction and discussion during the session; and

-

•

The wider implications for practice education of multidisciplinary attendance.

The influence of personal breastfeeding experiences

Personal breastfeeding experiences appeared to influence the way in which individuals responded, not only to the training session, but also to the initial invitation to participate. Throughout the programme, many of the participants were keen to share their own breastfeeding stories, encompassing both positive and negative experiences.

The narration of stories about events is said by Kirkham (1997, p. 183) to be the way that ‘people render their experiences coherent and give them meaning’. The opportunity for participants to revisit these stories and connect them with new knowledge offered during the session may help to reinforce or restore positive attitudes to breastfeeding. One participant commented: ‘It's 15 years since I breastfed, but I could relate to everything you said. It is good to see these issues being addressed.’

The need for greater interaction and discussion

This was primarily identified as a recurring issue through the observations of the project team. Several sessions were temporarily halted either to listen to personal experiences or to discuss particular issues as they arose. The facility to accommodate participants’ needs in this way within the session conforms to Parlett & Hamilton's (1987) view that the instructional system should have the ability to adapt to changes in the learning milieu.

Multidisciplinary attendance

The presentation was specifically designed to meet the identified needs of GPs and, whilst there appears to be a sound rationale for suggesting that GPs might invite other practice staff as a means of raising the awareness of breastfeeding amongst the wider practice team, there may be some disadvantages. For example, the GPs had requested that breastfeeding problems should be the dominant focus of the session and this could have reinforced pre‐existing negative impressions of breastfeeding or, even more alarmingly, introduced the concept that breastfeeding is problematic to those participants who had had little or no contact with breastfeeding women. Within those practices where all staff were present at the session, there were clearly those who felt the topic to be irrelevant to their needs. Compulsory attendance was not sought by the project team recognizing that it could cause resentment and was unlikely to facilitate effective adult learning, since a readiness to learn is said to be dependent on recognition of a topic's relevance (Knowles 1990). As the system of protected training time becomes more widely adopted, this issue of multidisciplinary attendance will need to be addressed by many practices because there must be many topics of either limited relevance for one or more professional groups or requiring a greater depth of knowledge or experience to appreciate the new information being offered.

Discussion

This educational package appears to be an acceptable and effective means of delivering breastfeeding information to GPs and practice teams. The majority of participants considered that they had gained a greater awareness of breastfeeding issues that would positively influence their approach to breastfeeding women. The relatively high response rate to the second questionnaire, with its self‐reports of improvements in practice and usage of the resource pack by several different professional groups, would also suggest that the package may be capable of influencing behaviour in the longer term.

Although it might seem more cost‐effective to organize an educational session at a central venue to which several practices could be invited, this approach has previously failed, presumably either through lack of interest or impracticality. Similarly, it could be argued that it is unnecessary and costly to use three presenters for such a short session. As a new initiative addressing an emotive topic that has previously been the subject of much conflicting advice, the demonstration of interagency collaboration is thought to be critically important.

The main adaptation to the session that should perhaps be considered is the introduction of greater opportunities for interaction and discussion. This would allow participants to narrate the personal breastfeeding experiences that are increasingly being recognized to influence the way in which health professionals support breastfeeding (Battersby 2002). It would also conform to recent recommendations that exploration of personal experiences should be an integral part of breastfeeding training programmes (Dykes 2004). Furthermore, the narration of positive experiences might help to counteract the previously expressed concern that a problem focused session might be presenting an unduly negative picture of breastfeeding to some participants. Reorganizing future sessions to incorporate greater opportunities for discussion could be achieved by reducing the information content of the presentation by removing the topics found to be of less general interest, such as the statistical information, to the resources pack. Nevertheless, care should be taken to ensure the balance of the session still allows sufficient time to comprehensively cover the requested information. Not only did the questionnaire responses indicate that new knowledge gained from the session was highly valued, but a more interactive session relies more heavily on the interpersonal skills of the presenters, with the potential for the session to be less focused and less structured.

Although, as previously discussed, there may be some drawbacks to multidisciplinary attendance, the considerable contribution to many of the sessions made by practice managers, receptionists and other non‐health professionals and their subsequent activities to improve their practice environments should not be underestimated. Organizers of any future programmes would be well advised to continue the practice of inviting and welcoming all practice‐attached staff irrespective of their professional grouping but to actively avoid any suggestion of coercion.

The evaluation findings illustrated the critical importance of the resource pack to the success of this programme and this has been confirmed since the end of the project by the purchase of a number of resource packs by a local Primary Care Trust so that packs are now available at each health visitor base. The packs can also now be purchased directly from the Breastfeeding Network. Clearly, only limited information can be conveyed in a relatively short presentation and so, in addition to acting as a reference source, the resource pack extends the range of information that can be made available, both to participants and to those practice team members unable to attend the training or who are subsequently employed. However it is important that material within the pack is updated regularly and the responsibility for this currently must lie with each practice.

It is recognized that the GPs who took part in this project are likely to be those who were already predisposed to support breastfeeding and, whilst it cannot be guaranteed that this package would elicit equally favourable responses from less‐motivated GPs, it is hoped that the evaluation is sufficiently positive to convince stakeholders, in particular Primary Care Trusts, of the value of developing of this work further. Certainly, since the conclusion of this project, other agencies have recognized the breastfeeding training needs of GPs and have begun to develop their own training packages (UNICEF UK BFI 2005; Dodds, personal communication). However, it is perhaps unfortunate that the Priorities and Planning Framework 2003–2006 (DH 2002) requires an increase of 2% points per year in rates of breastfeeding initiation but not in its duration. Fairbank et al. (2000), in their systematic review of interventions to promote the initiation of breastfeeding, suggest that the education of health professionals may have, in the first instance, more impact on the duration rather than the initiation of breastfeeding. It is to be hoped that funding authorities do not fall prey to seeking only initiatives thought likely to produce dramatic improvements in breastfeeding initiation rates with little regard to the irresponsibility of encouraging more women to breastfeed before health professionals are provided with the knowledge and skills to more adequately support them.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Anthony Sudell, Consultant in Public Health, Cumbria and Lancashire Strategic Health Authority, Christine Laverty, Clinical Governance Facilitation Manager, Preston Primary Care Trust and the members of the North‐west Lancashire Maternity Services Liaison Committee Breastfeeding Subgroup for helping to initiate and support this project. Funding for this one year project was received from the UK Government – Department of Health. Additional funds were provided by North‐west Lancashire Health Authority.

References

- Attride‐Stirling J. (2001) Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Battersby S. (2002) Midwives’ embodied knowledge of breastfeeding. Midirs Midwifery Digest 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh D. (1998) What's the Use of Lectures? Intellect Books: Exeter. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes A. & Domokos T.M. (1998) Negotiating breastfeeding: Pakistani women, white women and their experiences in hospital and at home. Sociological Research Online, 3 Available at: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/socresonline/3/3/5.html [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. & Reichardt C. (1979) Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Evaluation Research. Sage: Beverley Hills, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (DH) (2000) The NHS Plan: Improving Health and Reducing Inequality, July 2000. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/nationalplan/npch13.htm (12 June 2002).

- Department of Health (DH ) (2002) Improvement Expansion and Reform: The Next 3 Years Priorities and Planning Framework 2003–2006: Appendix B. p. 20. Available at: http://www.doh.gov.uk/planning2003−2006/index.htm (15 October 2002).

- Dykes F. (2004) Synthesis of Exploratory Studies that Relate to Training Needs of Health Professionals and Groups Involved in Supporting Breastfeeding Women. Report (unpublished) to Maternal and Child Nutrition Practice. Collaboration Centre, University of York.

- European Commission (2004) EU Project on Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding in Europe: A Blueprint for Action. European Commission, Directorate Public Health and Risk Assessment: Luxembourg. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank L., O'Meara S., Renfrew M., Wooldridge M., Sowden A. & Lister‐Sharp D. (2000) A systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to promote the initiation of breastfeeding. Health Technology Assessment 4, 1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fewtrell M.S. (2004) The long‐term benefits of having been breastfed. Current Paediatrics 114, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlyn B., Brooker S., Oleinikova K. & Wands S. (2002) Infant Feeding 2000. TSO: London. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P. & Pill R. (1999) Qualitative study of decisions about infant feeding among women in east end of London. British Medical Journal 318, 30–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L. (1994) Knowledge of basic nutrition amongst community health professionals. Maternal and Child Health 19, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham M. (1997) Stories and childbirth In: Reflections on Midwifery (eds Kirkham & M. E Perkins), pp 183–204. Bailliere Tindall: London. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles M. (1990) The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species, 4th edn Gulf Publishing: Houston, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Labarere J., Gelbert‐Baudino N., Ayral A.‐S., Duc C., Berchotteau M., Bouchon N. et al. (2005) Efficacy of breastfeeding support provided by trained clinicians during an early, routine, preventive visit. Pediatrics 115, 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Dingwall R., Greatbatch D., Parker S. & Watson P. (1998) Qualitative research methods in health technology assessment: a review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment 2, 215–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim A. (1992) Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. Pinter Publishers: London. [Google Scholar]

- Parlett M. & Hamilton D. (1987) Evaluation as illumination: a new approach to the study of innovatory programmes In: Evaluating Education: Issues and Methods (eds Murphy R. & Torrance H.), pp 57–73. Paul Chapman Publishing: London. [Google Scholar]

- Raisler J. (2000) Against the odds: breastfeeding experiences of low‐income mothers. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health 45, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson C. & Goddard D. (1997) Monitoring the quality of breastfeeding advice. Health Visitor 70, 422–424. [Google Scholar]

- St Leger A., Schnieden H. & Walsworth‐Bell J. (1997) Evaluating Health Services Effectiveness. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Taveras E.M., Capra A.M., Braveman P.A., Jensvold N.G. & Escobar G.J. (2003) Clinician support and psychosocial risk factors associated with breastfeeding discontinuation. Pediatrics 112, 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorley K. (2000) How GPs can support new mothers. General Practitioner 28: 44. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative (UNICEF UK BFI ) (2002) Proposal to Introduce Best Practice Standards for Breastfeeding Education Provided to Midwifery and Health Visiting Education. Available at: http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/education.htm (Accessed 19 May 2002).

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative (2004) Health Benefits of Breastfeeding. Available at: http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/health.asp (Accessed 20 March 2004).

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative (2005) Teaching Pack for GPs. Available at: http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/health.asp (Accessed 27 February 2005).

- World Health Organization (1990) Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding: the special role of maternity services. A joint WHO/UNICEF statement. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 31(Suppl 1), 171–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. WHO: Geneva. [Google Scholar]