Abstract

We aimed to analyse growth and recovery from undernutrition among moderately underweight ambulatory children receiving micronutrient‐fortified maize–soy flour (Likuni Phala, LP) or ready‐to‐use fortified spread (FS) supplementary diet. One hundred and seventy‐six 6–18‐month‐old individuals were randomized to receive 500 g LP or 350 g FS weekly for 12 weeks. Baseline and end of intervention measurements were used to calculate anthropometric gains and recovery from underweight, wasting and stunting. Mean weight‐for‐age increased by 0.22 (95% CI 0.07–0.37) and 0.28 (0.18–0.40) Z‐score units in the LP and FS groups respectively. Comparable increase for mean weight‐for‐length was 0.39 (0.20–0.57) and 0.52 (0.38–0.65) Z‐score units. Recovery from underweight and wasting was 20% and 93% in LP group and 16% and 75% in FS group. Few individuals recovered from stunting and mean length‐for‐age was not markedly changed. There were no statistically significant differences between the outcomes in the two intervention groups. In a poor food‐security setting, underweight infants and children receiving supplementary feeding for 12 weeks with ready‐to‐use FS or maize–soy flour porridge show similar recovery from moderate wasting and underweight. Neither intervention, if limited to a 12‐week duration, appears to have significant impact on the process of linear growth or stunting.

Keywords: fortified spread, infants and young children, randomized controlled trial, supplementary feeding, moderately underweight, undernutrition

Introduction

In Malawi, like most low‐income countries, childhood malnutrition is very common. Between 22% and 48% of Malawian children are undernourished by the age of 18 months (National Statistical Office & ORC Macro 2001). The peak incidence is between 6 and 18 months of age and moderate underweight is the most common presentation (National Statistical Office & ORC Macro 2001; Maleta et al. 2003a). Apart from causing acute morbidity and adverse long‐term sequelae, malnutrition is estimated to contribute to approximately half of the worldwide deaths in children under 5 years of age (Pelletier et al. 1995; Caulfield et al. 2004).

The epidemiology of undernutrition in Malawi necessitates emphasis on prevention or early home‐based management of children who have developed signs of malnutrition but who do not yet require hospitalization. There are, however, no easy options for such approaches as infection control has not proven widely successful and not many indigenous foods are rich in all the nutrients or available throughout the year (ACC/SCN 2001). Furthermore, widespread poverty in many communities reduces the possibility to purchase commercially available complementary foods. Thus, there is a need to develop and test new and inexpensive food supplements that could be easily used at the community level.

Cereal and legume mixtures that resemble the indigenous diet and are prepared in a manner similar to staple food have often been recommended for supplementary feeding of moderately undernourished children (Maleta et al. 2004). One such item is porridge made of vitamin and mineral‐enriched maize–soy flour [Likuni Phala (LP)], but data on its actual impact to the children's growth and nutritional status are scarce. Another option are micronutrient‐fortified, high‐energy spreads (ready‐to‐use therapeutic foods, RUTF) that have proven very beneficial for severely malnourished children both in famine and non‐famine situations (Briend et al. 1999; Briend 2001; Collins 2001; Diop el et al. 2003; Manary et al. 2004; Sandige et al. 2004; 2005, 2006; Ndekha et al. 2005). Similar products have recently been given also to less severely wasted children (Patel et al. 2005; Defourny et al. 2007), and recent data from a preliminary dose‐finding trial in Malawi suggested that they might improve growth also among moderately underweight young individuals (Kuusipalo et al. 2006). Thus far, however, the effects of fortified spreads (FS) and maize–soy flour have not been compared in this target group with a randomized controlled trial.

To more comprehensively analyse the efficacy of FS and maize–soy flour in promoting growth and recovery from malnutrition among moderately underweight 6–18‐month‐old children, we conducted a randomized controlled, single‐blind trial where moderately underweight children were provided for 12 weeks with weekly supplementary rations of either maize–soy flour or FS. The present communication reports mean growth, recovery from malnutrition and change in blood haemoglobin concentration among 6–18‐month‐old children getting the two supplements.

Methods

Study area and timing

The study was conducted in Lungwena, Mangochi district of Malawi, South‐Eastern Africa. In Lungwena, exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months is almost non‐existent and infant diet is typically complemented with thin maize porridge (‘phala’, 10% dry weight of maize flour) as early as from 2 to 6 months of age. Underweight and stunting are very common: in a recent prospective cohort study of 813 newborns, underweight [weight‐for‐age Z‐score (WAZ) < −2] and stunting [length‐for‐age Z‐score (LAZ) < −2] prevalence was 10% and 50% by 6 months of age and 40% and almost 80% by 18 months of age respectively (Maleta et al. 2003a). The climate in the area has one rainy season between December and March during which the staple food maize is grown. Enrolment to the trial was performed during the growing season when food levels were at the lowest, i.e. in March 2005. The 12‐week follow‐up of the last participant ended in July 2005.

Eligibility criteria, enrolment and randomization of the trial participants

Inclusion criteria for the trial included age of at least 6 months but less than 15 months, low WAZ (WAZ < −2.0), assumed residence in the study area throughout the follow‐up period and signed informed consent from at least one authorized guardian. Exclusion criteria were severe wasting, weight‐for‐length Z‐score (WLZ < −3.0), presence of oedema, history of peanut allergy, severe illness warranting hospitalization on the enrolment day, concurrent participation in another clinical trial or any symptoms of food intolerance within 30 min after the ingestion of a 6‐g test dose of FS, one of the food supplements used in the trial (given to all potential participants to exclude the possibility of peanut allergy).

For enrolment, trained health surveillance assistants from a local health centre contacted families, who were registered to live in the study area and known to have a baby of approximately right age. Infants and children, whose ages were appropriate and verified from an under‐five‐clinic card, were weighed in their homes and those who were moderately underweight or near the cut‐off point for it (WAZ < −1.8) were invited for further screening at the health centre. At the enrolment session, guardians were given detailed information on the trial contents and the infants and children were fully assessed for eligibility.

For group allocation, consenting guardians of eligible participants were shown and asked to pick one from a set of 10 identical opaque envelopes containing information on the group allocation of the participant. Because one set had to be finished before using the next, for each block the first guardian chose one from a total of 10, the second chose one from a total of 9 and the 10th picked the last envelope. The blocked randomization list and envelopes were created by people not directly involved in trial implementation and the code was not broken until all data had been collected and entered into a database. The actual randomization was done with a tailor‐made computer program, using random number and rank functions of a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Interventions and follow‐up

Trial participants received one of two interventions: An average of 71 g day−1 of micronutrient‐fortified maize–soy flour (LP) or an average 50 g of micronutrient FS. The supplements were home‐delivered to the participants at weekly intervals (either 500 g LP or 350 g FS at each food delivery). LP was packed in bags of 500 g and was purchased from a local producer (Rab Processors, Limbe, Malawi). Fortified spread was produced and packed in 50 g daily dose packets by Nutriset (Malaunay, France). Ingredients of LP were maize flour, soy flour and micronutrients and those of FS were peanut butter, milk, vegetable oil, sugar and micronutrients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Energy and nutrient content of the daily ration of the food supplement used in the trial

| Variable | LP group | FS group | Recommended nutrient intake* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 71 g | 50 g | |

| Energy (kcal) | 282 | 256 | |

| Protein (g) | 10.3 | 7.0 | |

| Carbohydrates (g) | n/a | 13.8 | |

| Fat (g) | 3.1 | 16.9 | |

| Retinol (µg RE) | 138 | 400 | 400 |

| Folate (µg) | 43 | 160 | 160 |

| Niacin (mg) | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| Panthothenic ac.(mg) | n/a | 2 | 2 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 48 | 30 | 30 |

| Vitamin D (µg) | n/a | 5 | 5 |

| Calcium (mg) | 71 | 366 | 500 |

| Copper (mg) | n/a | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Iodine (µg) | n/a | 135 | 75 |

| Iron (mg) | 5 | 8 | 5 |

| Magnesium (mg) | n/a | 60 | 60 |

| Selenium (µg) | n/a | 17 | 17 |

| Zinc (mg) | 3.6 | 8.4 | 8.4 |

LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); FS, fortified spread; n/a, information not available; * FAO & WHO 2002.

FS could be eaten as such, whereas the maize‐soy flour (LP) required cooking into porridge before consumption. The guardians were provided with spoons and advised to daily offer their infants or children either a packet of FS (FS group) or porridge containing 12 spoonfuls of maize–soy flour (LP group). All mothers were encouraged to continue breastfeeding on demand and to feed their children only as much of the food supplement as the child wanted to consume at a time (i.e. using responsive feeding practices and recognizing signs of satiety).

The participants were visited weekly at their homes to collect information on supplement use and possible adverse events. Empty food containers were collected every 3 weeks. At 6 and 12 weeks after enrolment, the participants were invited to a local health centre where they underwent physical examination, anthropometric assessment and laboratory tests.

Measurement of outcome variables

The primary outcome of the trial was weight gain during the 12‐week follow‐up. Secondary outcomes comprised length gain, mean change in anthropometric indices WAZ, LAZ and WLZ, recovery from moderate underweight, stunting or wasting, change in mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) and change in blood haemoglobin concentration.

Weight was measured from naked children with an electronic children weighing scale (SECA 834, Chasmors Ltd, London, UK) and recorded to the nearest 10 g. Length was measured to the nearest 1 mm with a high quality length board (Kiddimetre, Raven Equipment Ltd, Essex, UK). MUAC and head circumference were measured to the nearest 1 mm with non‐stretchable plastic tapes (Lasso‐o tape, Harlow Printing Limited, South Shields, Tyne and Wear, UK). All measurements were done in triplicate by one author (JP), whose measurement reliability was assessed at the start of the study and who was blinded of the participant study allocation from enrolment to the end of follow‐up. All instruments were calibrated every day before the measurements. Anthropometric indices (WAZ, LAZ and WLZ) were calculated with Epi‐Info 3.3.2 software (CDC, Atlanta, USA), based on the CDC 2000 growth reference (Kuczmarski et al. 2002), which was the latest available reference material at the time of enrolment to the trial.

A 2 ml venous blood sample was drawn and serum was separated by centrifugation at the beginning and end of follow‐up. Haemoglobin concentration was measured from a fresh blood drop with Hemo‐Cue® cuvettes and reader (HemoCue AB, Angelholm, Sweden).

All participants were tested for malaria parasites and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection at the beginning of the trial. Thick and thin blood smears were made, stained with Giemsa and screened microscopically for malaria parasites from all participants. Screening for HIV‐infection was done from fresh blood with two antibody rapid tests, according to the manufacturers’ instructions (Determine, Abbott Laboratories, Abbot Park, IL, USA and Uni‐Gold, Trinity Biotech plc, Bray, Ireland). Dried filter paper blood samples from participants with a positive result in either of the rapid tests were further tested with DNA amplification technology, according to the manufacturers’ instructions (Amplicor HIV‐1 Monitor Test Version 1.5, Hoffmann‐La Roche, Ltd, Basel, Switzerland).

Training and quality control

All data collection was implemented according to standard operating procedures (SOP) developed before commencing the study. The four research assistants for the trial were trained on the use of these SOPs as well as the use of questionnaires and food hygiene. The performance of data collectors were daily monitored by one author (JP) and a senior research assistant (MB).

The reliability of anthropometric measurements was assessed for one authors (JP) and one research assistant (MB) before the commencement of the trial. In standardization measurements from eight infants, the technical error of measurement for JP was 0.41 cm, 0.13 cm and 0.35 cm for length, MUAC and head circumference respectively (WHO, Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006). Compared with the expert (MB), the observer (JP) overestimated MUAC by 0.35 cm and underestimated head circumference and length on average by 0.35 cm and by 0.37 cm respectively. Coefficient of reliability was 0.98, 0.89 and 0.96 for length, MUAC and head circumference respectively (Marks et al. 1989).

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated from expected values for the primary outcome (weight gain) based on an earlier preliminary dose‐finding trial (Kuusipalo et al. 2006). Assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 0.39 kg for changes in weight in both groups during intervention period and a mean gain difference of 0.17 kg between the intervention group (FS) and the control group (LP), a sample size of 84 infants per group was required to provide the trial with 80% power and 95% confidence. To allow for approximately 5% attrition, the target enrolment was 88 infants per group.

Data management and analysis

Raw data were initially recorded on paper forms and their coherence was checked daily by a senior research assistant. Summary data were transcribed to paper case report forms and then double‐entered into a tailor‐made Microsoft Access 2003 database. The two entries were electronically compared; all extreme and otherwise susceptible values were confirmed or corrected.

Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). For the statistical analysis, the study participants were classified into two groups according to the trial allocation. Participants with no anthropometric data at the final measurement were excluded from outcome analyses but included in the comparison of baseline characteristics, and all those with at least one follow‐up measurement were included in the sensitivity analysis.

For continuous and categorical outcomes, the two intervention groups were compared with t‐test and Fisher's exact test respectively. For comparison of continuous baseline and final anthropometric and haematological group values, paired t‐test was used, whereas categorical baseline and final variables were compared using sign test. For the studies of compliance using visits as units of analysis, the Huber–White robust standard error was used to allow for correlated data (multiple visits per child). Confidence interval for SD was calculated using the Jacknife method.

Recovery from underweight was defined as WAZ ≤ −2.0 at enrolment and WAZ > −2.0 at the end follow‐up. Recovery from wasting (WLZ ≤ −2.0 at enrolment) and stunting (LAZ ≤ −2.0 at enrolment) were defined accordingly as WLZ > −2.0 and LAZ > −2.0 at completion of the trial respectively.

Ethics, study registration and participant safety

The trial was performed according to International Conference of Harmonization–Good Clinical Practice (ICH‐GCP) guidelines and it adhered to the principles of Helsinki declaration and regulatory guidelines in Malawi. Before the onset of enrolment, the trial protocol was reviewed and approved by the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (University of Malawi) and the Ethical Committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District (Finland). Key details of the protocol were published at the clinical trial registry of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, trial identification is NCT00131222).

A data safety and monitoring board (DSMB) continuously monitored the safety of the trial. All suspected serious adverse events (SAE) were reported to the DSMB for assessment. SAE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence that either resulted in death or was life‐threatening, or required inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, or results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or other serious medical condition.

Results

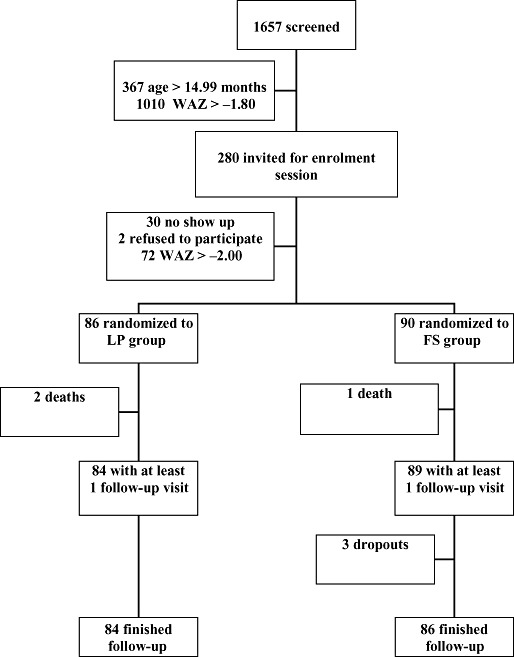

Of the 1657 initially screened infants and children, 367 were too old (>14.99 months), 1010 were above anthropometric cut‐off for further evaluation (WAZ > −1.80) and two were too ill on the day of screening. Among the rest, 30 were not brought to the enrolment session, 72 were not underweight (WAZ > −2.00) and 2 declined participation after receiving full information of the trial. The remaining 176 infants and children were randomized into two intervention groups (Fig. 1). There was no difference in the mean WAZ between the enrolled children and those who were eligible but not enrolled (P = 0.34). None of the participants showed any adverse reaction to the 6‐g test dose of FS.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants. FS, fortified spread; LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); WAZ, weight‐for‐age Z‐score.

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics and anthropometric measurements of the participants by intervention group. At enrolment, participants in the LP group were on average 5 days younger, 100 g lighter and 0.6 cm shorter than those in the FS group (Table 2). The prevalence (number of participants) with underweight (WAZ < −2) was 100% (86) in the LP and 99% (89) in the FS group. Comparable figures for stunting (LAZ < −2) were 69% (59) vs. 64% (33) and those for wasting (WLZ < −2) were 16% (14) vs. 13% (12), in the LP and FS groups respectively. Eight of the participants had a positive HIV‐antibody test at enrolment, but only five of them were truly HIV‐infected, as evidenced by a positive Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test.

Table 2.

Background characteristics of the participants at enrolment

| Variable | LP group | FS group |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 86 | 90 |

| Mean (SD) age (months) | 11.58 (2.77) | 11.73 (2.46) |

| Proportion of boys | 49/86 (57.0%) | 44/90 (49.0%) |

| Mean (SD) weight (kg) | 7.02 (1.05) | 7.12 (0.82) |

| Mean (SD) length (cm) | 67.3 (4.5) | 67.9 (3.8) |

| Mean (SD) mid‐upper arm circumference (cm) | 12.9 (1.0) | 13.0 (0.87) |

| Mean (SD) head circumference (cm) | 44.3 (1.9) | 44.4 (1.6) |

| Mean (SD) weight‐for‐age Z‐score | −3.09 (0.85) | −2.95 (0.71) |

| Mean (SD) length‐for‐age Z‐score | −2.45 (0.93) | −2.26 (0.88) |

| Mean (SD) weight‐for‐length Z‐score | −1.20 (0.83) | −1.21 (0.69) |

| Mean (SD) blood haemoglobin concentration (g L−1) | 93 (15) | 91 (17) |

| Proportion with PCR confirmed HIV infection | 4/82 (4.9%) | 1/82 (1.2%) |

| Proportion with peripheral blood malaria parasitaemia | 10/86 (11.6%) | 10/89 (11.2%) |

LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); FS, fortified spread; SD, standard deviation; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

During the 12‐week follow‐up, three participants died and three were lost to follow‐up (Fig. 1). The assumed causes of death were anaemia and respiratory tract infection in the LP group and respiratory tract infection in the FS group. From the lost participants, one moved away and two were unavailable for final measurements although they had participated in all home visits and received and apparently eaten the intervention food. Comparison of baseline WAZ between participants who completed the follow‐up and those who died or were lost did not suggest that they come from different populations (P = 0.15 and P = 0.70 respectively). The losses to follow‐up were also not significantly different between the intervention groups (P = 0.61 for deaths and P = 0.68 for total loss to follow‐up; Fisher's exact test).

All mothers reported that their children readily ate the provided supplement and diversion of any portion to someone else than the intended beneficiary was reported only at 2/2065 (0.10%) food delivery interviews, both in LP and FS groups. From the weekly home visits during which trial products were checked, the percentage of visits with leftovers found were 4.9% and 6.5% in the LP and the FS groups respectively (P = 0.18).

Table 3 shows the main outcome data for continuous variables. Among the 170 participants followed up for 12 weeks, mean gain in weight was 50 g [95% confidence interval (CI) −80–174 g] higher in the FS group than the LP group. Comparable change for length was 1.5 mm (95% CI −5.1–2.2 mm) lower in the FS group. Correspondingly, mean WAZ and WLZ increased more and mean LAZ fell more in the FS group than the LP group. None of these differences reached statistical significance. Average changes in mean MUAC, head circumference and blood haemoglobin concentration were also quite similar in the two groups (Table 3). As shown, all 95% CIs were consistent with only relatively small between‐group differences to either direction.

Table 3.

Anthropometric and haematological outcomes among underweight infants receiving a 12‐week dietary supplementation with either FS or maize–soy flour

| Variable | LP group | FS group | Difference in mean changes (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Change in weight (kg) | 0.84 (0.46) | 0.89 (0.38) | 0.05 (−0.80 to 0.17) |

| Change in length (cm) | 2.65 (1.1) | 2.50 (1.3) | −0.14 (−0.51 to 0.22) |

| Change in mid‐upper arm circumference (cm) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.3) |

| Change in head circumference (cm) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.5) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) |

| Change in weight‐for‐age Z‐score | 0.22 (0.69) | 0.29 (0.51) | 0.07 (−0.11 to 0.26) |

| Change in length‐for‐age Z‐score | −0.08 (0.41) | −0.13 (0.42) | −0.05 (−0.17 to 0.08) |

| Change in weight‐for‐length Z‐score | 0.39 (0.85) | 0.52 (0.63) | 0.13 (−0.09 to 0.36) |

| Change in blood haemoglobin concentration (g L−1) | 1.5 (16.1) | 3.8 (16.9) | 2.3 (−2.7 to 7.3) |

LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); FS, fortified spread; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Because of the limited outcome difference between the groups, we compared the variation in weight gain to the predictions used for sample size calculation. The observed standard deviation for weight gain was 0.38 kg in FS group and 0.46 kg in LP group, compared with estimated SD of 0.39 kg in both groups. While the observed variation is slightly different in either direction than expected, the 95% CI of the SDs of the whole sample and that of the two intervention groups included the expected value of 0.39 (Jacknife method), suggesting that a marked between‐group difference would have been identified with the current sample and trial design if it existed in the population.

Table 4 documents recovery from various forms of moderate malnutrition. During the 12‐week intervention, approximately 20% of the initially underweight individuals, 85% of the initially wasted, and 10% of the initially stunted children recovered from their condition, with little difference between the two intervention groups.

Table 4.

Recovery from moderate malnutrition among participants in maize–soy flour and FS groups

| Variable | LP group | FS group | Absolute risk difference (95% CI) | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence (%) | Incidence (%) | |||

| Weight‐for‐age Z‐score ≥ −2.0 | 17/84 (20.2) | 14/88 (15.9) | −4.3 (−15.8 to 7.2) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) |

| Weight‐for‐length Z‐score ≥ −2.0 | 13/14 (92.9) | 9/12 (75.0) | 17.9 (−45.8 to 10.1) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| Length‐for‐age Z‐score ≥ −2.0 | 5/57 (8.8) | 7/57 (12.3) | 3.5 (−7.7 to 14.8) | 1.4 (0.5 to 4.2) |

LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); FS, fortified spread; CI, confidence interval.

Table 5 demonstrates the prevalence of malnutrition at the end of follow‐up, i.e. the function of enrolment prevalence, incidence of new cases and recovery during the intervention. Again, no statistically significant group‐level differences were observed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prevalence of malnutrition with various criteria at final measurement among participants in maize–soy flour and FS groups

| Variable | LP group (n = 84)* | FS group (n = 86)* | Difference of proportions (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | ||

| Weight‐for‐age Z‐score < −2 | 68 (81.0) | 74 (86.1) | 5.1 (−6.1 to 16.2) |

| Weight‐for‐length Z‐score < −2 | 4 (4.8) | 5 (5.8) | 1.0 (−5.7 to 7.8) |

| Length‐for‐age Z‐score < −2 | 62 (73) | 54 (62.8) | −11.0 (−24.9 to 28.7) |

| Mid‐upper arm circumference < 12.5 cm | 17 (20.2) | 7 (8.1) | −12.1 (−22.5 to 17.4) |

| Blood haemoglobin < 100 g L−1 | 48 (57.8) | 51 (60.0) | 2.2 (−12.7 to 17.0) |

LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); FS, fortified spread; CI, confidence interval; *n for blood haemoglobin was 83 and 85 for LP and FS respectively.

In a comparison between enrolment status (Table 2) and end of intervention (3, 5), the mean WAZ increased by 0.22 (95% CI 0.07–0.37) Z‐score units in the LP group and by 0.28 (95% CI 0.18–0.40) Z‐score units in the FS group. Increase for mean weight‐for‐length was 0.39 (95% CI 0.20–0.57) and 0.52 (95% CI 0.38–0.65) Z‐score units for LP and FS groups respectively. The prevalence of underweight (WAZ < −2.00) was reduced significantly in both groups (P < 0.001 for LP and P = 0.001 for FS, sign test). A similarly reduced trend was noticed for the prevalence wasting (P < 0.001 for LP and P = 0.07 for FS, sign test), and low MUAC (P = 0.02 for LP and P < 0.001 for FS, sign test). The prevalence of stunting (P = 0.27 for LP and P > 0.99 for FS, sign test) and anaemia (P = 0.69 for LP and P = 0.04 for FS, sign test) were not markedly changed during the intervention.

Sensitivity analysis to assess robustness of the results after loss to follow‐up produced similar standardized weight gain as those reported above: 0.30 Z‐score (95% CI 0.19–0.41) and 0.22 Z‐score (95% CI 0.19–0.41) for FS and LP groups respectively.

There was no significant interaction between intervention and baseline WAZ, WLZ or LAZ, either using weight gain (P = 0.26 for WAZ, P = 0.93 for WLZ and P = 0.25 for LAZ) or length gain (P = 0.47 for WAZ, P = 0.19 for WLZ and P = 0.10 for LAZ) as an outcome.

Morbidity was similar in both groups (Table 6). All interventions were well tolerated by the participants. Besides the three deaths, three participants were hospitalized and recorded as having experienced an SAE during the follow‐up. The LP and FS groups shared four and two of these SAEs (P = 0.44; Fisher's exact test). Both the study physician and the DSMB considered all deaths and SAE unlikely related to the trial interventions.

Table 6.

Occurrence of morbidity among participants in maize–soy flour and FS groups

| Variable | LP group (n = 1020) | FS group (n = 1063) | Difference of proportions (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | ||

| Home visits fever was reported | 36 (3.6) | 54 (5.1) | 1.6 (−0.5 to 3.6) |

| Home visits diarrhoea was reported | 74 (7.3) | 79 (7.4) | 0.2 (−2.7 to 3.1) |

| Home visits ARI was reported | 93 (9.1) | 95 (8.9) | −0.2 (−2.7 to 2.2) |

| Home visits other illnesses were reported | 78 (7.7) | 63 (5.9) | −1.7 (−4.3 to 0.9) |

LP, Likuni Phala (maize–soy flour); FS, fortified spread; CI, confidence interval; ARI, acute respiratory tract infection.

Discussion

The present trial was carried out to test the growth‐promoting effects of a micronutrient‐fortified, energy dense ready‐to‐use spread (FS), when used as a supplementary food among 6–18‐month‐old underweight infants and children in rural Malawi. Enrolment rate for the trial was high, group allocation was random, trial groups were rather similar at enrolment, follow‐up was identical for all groups, compliance with the intervention appeared good, loss to follow‐up was infrequent and balance between the groups and people measuring the outcomes were blinded to the group allocation. Additionally, because calculation of anthropometric indices (WAZ, LAZ and WLZ) standardizes for gender, baseline differences of gender proportions between the trial groups did not affect the interpretation of the main results. Hence, the observed results are likely to be unbiased and thus representative of the population from which the sample was drawn.

In our sample, participants receiving FS for 12 weeks gained on average slightly more weight but less length than those receiving an iso‐energetic portion of maize–soy flour (LP). Mean changes in MUAC and blood haemoglobin concentration were also higher in the FS group but head circumference increased more in the LP group. However, all differences between the groups were marginal and the 95% CIs for point estimates excluded large difference in population. Although the higher end of the 95% CI for the difference in mean weight gain just overlapped with the predefined cut‐off for clinical significance, the data do not therefore support our initial hypothesis that weekly home provision of FS to 6–15 months underweight children in rural Malawi would be noticeably better in alleviating their being underweight or promoting catch‐up growth over a 12‐week period than similar supplementation scheme with maize–soy flour. Rather, our results are consistent with the two interventions having a similar or only slightly different impact on these outcomes.

Children in both intervention groups showed good recovery from wasting, some recovery from being underweight and no change in their stunting status. For ethical reasons, however, we did not include an unsupplemented control group in our trial design. This omission, while allowing a comparison between the two interventions, limits our possibility to make conclusions on their effect as compared with young children receiving no intervention. It is thus possible that the observed recovery from wasting or being underweight, and the increase in mean weight‐for‐age or weight‐for‐length result from a confounder like a seasonal effect on growth or regression to the mean phenomenon. A comparison to earlier studies in the same area suggest, however, that unsupplemented underweight children of this age would have a somewhat lower weight and length gain velocity (Kuusipalo et al. 2006) and that seasonal effect on weight gain would be markedly lower than the approximately 0.3 Z‐score unit increase observed in this trial (Maleta et al. 2003b). Rather, the increase in relative weight is comparable to observations with other supplementary feeding interventions in similar target groups (Simondon et al. 1996; Lartey et al. 1999; Becket et al. 2000; Bhandari et al. 2001; Oelofse et al. 2003; Adu‐Afarwuah et al. 2007).

Micronutrient FS were initially designed to be used as a rehabilitation food for malnourished children (Briend et al. 1999). In a succession of studies, therapeutic versions of the spreads (RUTF) were shown to induce recovery, first in a hospital setting, then as outpatients in efficacy trials and finally in programmatic settings (Collins 2001; Diop el et al. 2003; Manary et al. 2004; Sandige et al. 2004; 2005, 2006; Ndekha et al. 2005). Recently, there has been a major interest to expand the use of spreads to treatment of less severe conditions or primary prevention malnutrition. The results from our study support the findings of Patel et al. (2005) in Malawi and those of Medicins Sans Frontieres in Niger (Defourny et al. 2007), suggesting that FS can also efficiently promote recovery from moderate wasting, thus acting as a secondary prevention of severe malnutrition.

In contrast to recovery from wasting and associated increase in weight‐for‐age, linear growth and the process of stunting seems to be very little affected by a 12‐week supplementary feeding with FS or LP, as evidenced by a decreasing LAZ and a very low recovery rate from stunting in both groups in our trial. This is not surprising, as length gain acceleration has often been shown to follow weight gain increase with a certain lag period, e.g. by 3 months in rural Malawi (Walker & Golden 1988; Costello 1989; Heikens et al. 1989; Maleta et al. 2003b). Hence, only a longer intervention might have the potential for the primary prevention of stunting or rehabilitation of moderately underweight children in an area, where low weight is usually a function of inadequate linear growth. First results from such an approach, i.e. 6–12‐month supplementation of complementary feeding with 20–50 g FS have been promising, documenting increased length gain and prevention of severe stunting among rural infants in Ghana and Malawi (Adu‐Afarwuah et al. 2007; Phuka et al. 2008). Possible nutrients in FS that could account for improved linear growth in longer interventions include, e.g. essential fatty acids, zinc or components of cow milk (Brown et al. 2002; Hoppe et al. 2006; Adu‐Afarwuah et al. 2007).

Taken together, our results suggest that 12 week‐long supplementary feeding with FS and LP porridge have similar impacts on the weight and length gain of underweight infants in a low‐income setting like Malawi. Although the results are consistent with the idea that both interventions promote recovery from wasting or moderate underweight, the lack of no‐food control group hinders any firm conclusions on the independent effect of either intervention. This, and the possible effect of seasonality on the growth outcomes, should be addressed in further controlled trials.

Source of funding

The trial was funded by grants from the Academy of Finland (grants 200720 and 109796), Foundation for Paediatric Research in Finland and Medical Research Fund of Tampere University Hospital. The micronutrient mixture used in the production of FS was provided free of charge by Nutriset, Inc. (Malaunay, France). John Phuka and Chrissie Thakwalakwa are receiving personal stipends from Nestlé Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

André Briend was a consultant to Nutriset until December 2003 and the company has also financially supported the planning of another research project by the same study team through Per Ashorn and the University of Tampere after the completion of this trial. Other authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders of trial had no role in the implementation, analysis or reporting.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the people of Lungwena, the staff at the Lungwena Training Health Centre and our research assistants for their positive attitude, support and help in all stages of the study, and to Laszlo Csonka for designing the collection tools and data entry programs. André Briend is currently a staff member of the World Health Organization (WHO). André Briend alone is responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions or stated policy of the WHO.

References

- ACC/SCN (2001) What works? In: A Review of the Efficacy and Effectiveness of Nutrition Interventions (eds Allen L.H. & Gillespie S.R.), pp 69–87. ACC/SCN: Geneva in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank: Manila. [Google Scholar]

- Adu‐Afarwuah S., Lartey A., Brown K.H., Briend A., Zlotkin S. & Dewey K.G. (2007) Randomized comparison of 3 types of micronutrient supplements for home fortification of complementary foods in Ghana: effects on growth and motor development. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86, 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becket C., Durnin J.V., Aitchison T.C. & Pollitt E. (2000) Effects of an energy and micronutrient supplementation on anthropometry in undernourished children in Indonesia. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 54 (Suppl. 2), S52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari N., Bahl R., Nayyar B., Khokhar P., Rohde J.E. & Bhan M.K. (2001) Food supplementation with encouragement to feed it to infants from 4 to 12 months of age has a small impact on weight gain. Journal of Nutrition 131, 1946–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briend A. (2001) Highly nutrient‐dense spreads: a new approach to delivering multiple micronutrients to high‐risk groups. British Journal of Nutrition 85, S175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briend A., Lacsala R., Prudhon C., Mounier B., Grellety Y. & Golden M.H. (1999) Ready to use therapeutic food for treatment of marasmus. Lancet 353, 1767–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K.H., Peerson J.M., Rivera J. & Allen L.H. (2002) Effect of supplemental zinc on the growth and serum zinc concentrations of prepubertal children: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 75, 1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield L.E., De Onis M., Blossner M. & Black R.E. (2004) Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 80, 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto M.A., Sandige H., Ndekha M.J., Ashorn P., Briend A., Ciliberto H.M. et al (2005) A comparison of home‐based therapy with ready‐to‐use therapeutic food with standard therapy in the treatment of malnourished Malawian children: a controlled, clinical effectiveness trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 81, 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto M.A., Manary M.J., Ndekha M.J., Briend A. & Ashorn P. (2006) Home‐based therapy for oedematous malnutrition with ready‐to‐use therapeutic food. Acta Paediatrica 95, 1012–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. (2001) Changing the way we address severe malnutrition during famine. Lancet 358, 498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello A.M. (1989) Growth velocity and stunting in rural Nepal. Archives of Disease in Childhood 64, 1478–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defourny I., Seroux G., Abdelkader I. & Harczi G. (2007) Management of moderate acute malnutrition with RUTF in Niger. Emergency Nutrition Network 31, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Diop el H.I., Dossou N.I., Ndour M.M., Briend A. & Wade S. (2003) Comparison of the efficacy of a solid ready‐to‐use food and a liquid, milk‐based diet for the rehabilitation of severely malnourished children: a randomized trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 78, 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO & WHO Joint Expert Consultation Report (2002) Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Heikens G.T., Schofield W.N., Dawson S. & McGregor S. (1989) The Kingston project. I. Growth of malnourished children during rehabilitation in the community, given a high energy supplement. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 43, 145–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe C., Molgaard C. & Michaelsen K.F. (2006) Cow's milk and linear growth in industrialized and developing countries. Annual Review of Nutrition 26, 131–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski R.J., Ogden C.L., Guo S.S., Grummer‐Strawn L.M., Flegel K.M., Mei Z. et al (2002) 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital & Health Statistics 11, 246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusipalo H., Maleta K., Briend A., Manary M. & Ashorn P. (2006) Growth and change in blood haemoglobin concentration among underweight Malawian infants receiving fortified spreads for 12 weeks: a preliminary trial. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 43, 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartey A., Manu A., Brown K.H., Peerson J.M. & Dewey K.G. (1999) A randomized, community‐based trial of the effects of improved, centrally processed complementary foods on growth and micronutrient status of Ghanaian infants from 6 to 12 mo of age. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70, 391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleta K., Virtanen S.M., Espo M., Kulmala T. & Ashorn P. (2003a) Childhood malnutrition and its predictors in rural Malawi. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 17, 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleta K., Virtanen S.M., Espo M., Kulmala T. & Ashorn P. (2003b) Seasonality of growth and the relationship between weight and height gain in children under three years of age in rural Malawi. Acta Paediatrica 92, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleta K., Kuittinen J., Duggan M.B., Briend A., Manary M., Wales J. et al (2004) Supplementary feeding of underweight, stunted Malawian children with a ready‐to‐use food. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 38, 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manary M.J., Ndekha M., Ashorn P., Maleta K. & Briend A. (2004) Home‐based therapy for severe malnutrition with ready‐to‐use food. Archives of Disease in Childhood 89, 557–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G.C., Habicht J.P. & Mueller W.H. (1989) Reliability, dependability, and precision of anthropometric measurements. The second national health and nutrition examination survey 1976–1980. American Journal of Epidemiology 130, 578–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (Malawi) & ORC Macro. (2001) Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2000. National Statistical Office and ORC Macro: Zomba, Malawi and Calverton, Maryland, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ndekha M.J., Manary M.J., Ashorn P. & Briend A. (2005) Home‐based therapy with ready‐to‐use therapeutic food is of benefit to malnourished, HIV‐infected Malawian children. Acta Paediatrica 94, 222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelofse A., Van Raaij J.M., Benade A.J., Dhansay M.A., Tolboom J.J. & Hautvast J.G. (2003) The effect of a micronutrient‐fortified complementary food on micronutrient status, growth and development of 6 to 12‐month‐old disadvantaged urban South African infants. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 54, 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M.P., Sandige H.L., Ndekha M.J., Briend A., Ashorn P. & Manary M.J. (2005) Supplemental feeding with ready‐to‐use therapeutic food in Malawian children at risk of malnutrition. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 23, 351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier D.L., Frongillo E.A., Schroeder D.G. & Habicht J.P. (1995) The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 73, 443–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuka J.C., Maleta K., Thakwalakwa C., Cheung Y.B., Briend A., Manary, M.J. et al (2008) Complementary feeding with fortified spread and incidence of severe stunting in 6–18 month old rural Malawians. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 162, 619–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandige H., Ndekha M.J., Briend A., Ashorn P. & Manary M.J. (2004) Home‐based treatment of malnourished Malawian children with locally produced or imported ready‐to‐use food. Journal of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 39, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simondon K.B., Gartner A., Berger J., Cornu A., Massamba J.P., Miguel J.L.S. et al (1996) Effect of early, short‐term supplementation on weight and linear growth of 4–7‐mo‐old infants in developing countries: a four‐country randomized trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 64, 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S.P. & Golden M.H.N. (1988) Growth in length of children recovering from severe malnutrition. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 42, 395–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group (2006) Reliability of anthropometric measurements in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatrica 450 (Suppl.), 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]