Abstract

Considerable evidence suggests that fathers' absence from home has a negative short‐ and long‐term impact on children's health, psychosocial development, cognition and educational experience. We assessed the impact of father presence during infancy and childhood on children's height‐for‐age z‐score (HAZ) at 5 years old. We conducted secondary data analysis from a 15‐year cohort study (Young Lives) focusing on one of four Young Lives countries (Peru, n = 1821). When compared with children who saw their fathers on a daily or weekly basis during infancy and childhood, children who did not see their fathers regularly at either period had significantly lower HAZ scores (−0.23, P = 0.0094) after adjusting for maternal age, wealth and other contextual factors. Results also suggest that children who saw their fathers during childhood (but not infancy) had better HAZ scores than children who saw their fathers in infancy and childhood (0.23 z‐score, P = 0.0388). Findings from analyses of resilient children (those who did not see their fathers at either round but whose HAZ > −2) show that a child's chances of not being stunted in spite of paternal absence at 1 and 5 years old were considerably greater if he or she lived in an urban area [odds ratio (OR) = 9.3], was from the wealthiest quintile (OR = 8.7) and lived in a food secure environment (OR = 3.8). Interventions designed to reduce malnutrition must be based on a fuller understanding of how paternal absence puts children at risk of growth failure.

Keywords: father–child relations, fatherhood, health and illness, single‐parent families

Introduction

Nutrition is intimately connected with the cognitive, physical and emotional development of children (Agarwal et al. 1989; Grantham‐McGregor et al. 1999; Glewwe & King 2001; Victora et al. 2008). The causes of malnutrition are multifaceted and include poverty, unsanitary living conditions, unfavourable political environment and family characteristics (Frongillo et al. 1997; Rayhan et al. 2007; Pryer et al. 2004; Engle et al. 2007; Black et al. 2008).

There is considerable evidence from industrialised and less‐industrialised nations that suggests that fathers' absence from home has a negative short‐ and long‐term impact on children's psychosocial development, cognition and education as well as their health (Sahn & Alderman 1997; Joshi et al. 1999; Clarke et al. 2000; Sigle‐Rushton & McLanahan 2006). With respect to health, research carried out in less‐industrialised nations suggests a relationship between family structure and undernutrition. In two studies (Sahn & Alderman 1997; Bronte‐Tinkew & DeJong 2004), children from single‐parent homes were found to be at higher risk of undernutrition. In another study (Chopra 2003), children who saw their fathers less than weekly had higher rates of malnutrition than children who saw them more frequently. Father absence may also be related to illness in children (Schmeer 2009).

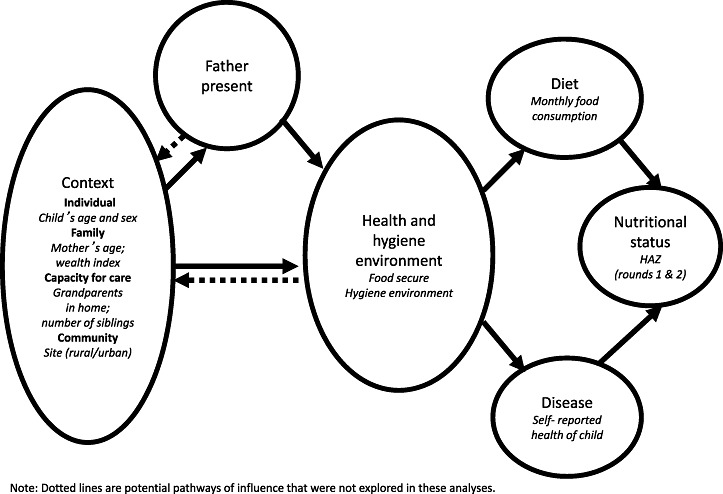

There are few additional studies from less‐industrialised countries that describe the link between paternal presence and children's nutritional status. Just as importantly, little is known about how the type and quality of paternal involvement affects children's nutrition. There are many ways fathers can positively impact children's health and their nutrition in particular. These include decision‐making and greater resource provision that favour children, access to resources as a result of fathers' status in the community, social and emotional attachment and role modelling. Our conceptual framework (Fig. 1) posits that father presence mediates the relationship between individual/family/community context and health and hygiene environment. Specifically, father's presence can have a direct bearing on household food security and hygiene. Alternatively, context, including mother's age, a family's socio‐economic status and the presence of grandparents and siblings in the home, can affect food security and hygiene directly or may do so indirectly by influencing whether fathers co‐reside with their children. For example, fathers frequently contribute to household resources (as measured by the wealth index) but diminished resources may lead the father to migrate in hopes of obtaining employment elsewhere. Additionally, father presence may positively or negatively impact upon food security, depending on whether fathers mobilise resources in favour of (or against) the provision of food for individual household members.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework guiding analyses on the relationship between father presence and nutritional status.

Globally, paternal absence is on the rise (Lang & Zagorsky 2001). Absence may result from childbirth outside of formal marriage, marital discord, abandonment or migration – either temporary or long term (Frank & Wildsmith 2005). Peru – the focus of this research – has a high prevalence of paternal absence. According to the Demographic and Health Survey, one in four Peruvian children live in homes where fathers are absent (Cespeda et al. 2004).

The purpose of this study is to determine whether paternal presence is associated with better nutritional status [measured by height‐for‐age z‐scores (HAZ)] after accounting for the impact of other factors. A second purpose is to determine whether some children whose fathers are absent are not stunted and to identify factors associated with resiliency among these children. Using secondary data analysis, we tested two hypotheses: (1) paternal presence is associated with better nutritional status (HAZ) after accounting for the impact of other factors that may influence nutritional status such as resources and individual, family and community context, and (2) resources and individual, family and community context explain why resilient children are not stunted.

We focus on Peru because father absence is higher in Peru than in Ethiopia, India and Vietnam where similar (Young Lives) research is being conducted. Additionally, childhood stunting is very common in Peru. Elucidating the extent to which paternal presence affects children's nutritional status and identifying how some children whose fathers are absent are able to remain well nourished – is critical to designing programs and policies that ensure children's well‐being.

One of the challenges in conducting research on paternal presence in less‐industrialised countries is the lack of longitudinal datasets that are sufficiently rich in detail to shed light on the relationship between paternal presence and children's nutritional status. We analyse the Young Lives dataset for Peru to examine this relationship.

Key messages

-

•

Paternal absence is related to chronic undernutrition of Peruvian children.

-

•

Additional research is needed to understand how paternal absence influences child nutrition and health outcomes, and how particular vulnerabilities can be mitigated through social services and appropriate safety net programs.

-

•

Researchers, policy makers, program planners and implementers should focus greater attention on resilient children and how their families achieve positive outcomes for children.

-

•

Governmental and non‐governmental efforts to improve health should focus not only on mothers but should actively involve fathers as well and should be aimed at reducing gender stereotypes.

Materials and methods

Young Lives is an international study of childhood poverty. The study follows approximately 8000 children every 3–5 years in four countries (∼2000 children each in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam). Young Lives began in 2002 when children were 1 year of age and will continue for 15 years. In future analyses, we will analyse data from Ethiopia, India and Vietnam and will include information from the third round of data collection when children were 8 years old. The Grupo de Análisis para el Desarrollo and the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional (IIN) designed and conducted primary data collection in Peru.

The Peruvian study sample consisted of 20 districts that were selected through a multistage sampling strategy that consisted of systematic sampling based on poverty ranking and random sampling of 100 households in each district. Sample size calculations were based on power to detect moderate‐sized differences when subgroups represented at least 20% of the overall sample (Wilson et al. 2006). All three geographic regions of Peru (coastal, highland and jungle), as well as urban and rural sites, were represented (Crookston et al. 2010).

Details of primary data collection are described elsewhere (Crookston et al. 2010). In brief, the cohort is comprised of children aged 6–17.9 months at enrolment (n = 2052). Subjects were recruited from randomly selected communities within the 20 districts. Within each community, the starting point for data collection was also randomly chosen. Data were gathered from 100 children in each site. Between round 1 and round 2 (R1 and R2) when children were 1 and 5 years of age, only 4.3% (n = 89) were lost to follow‐up. Approximately 5.7% children did not see their mothers on a daily basis and were not included in the sample (n = 117). Furthermore, 1.2% of respondents were omitted because they lacked complete data on paternal presence (n = 25). These selections resulted in a sample size of 1821 children.

Three teams consisting of six interviewers each collected household and child level data. Interviews were conducted on one or more days depending on family preference and lasted approximately 4 hours. Staff from IIN used Epilnfo (Version 3.4.3, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) for data entry. Data were transferred to Microsoft Access (version 2000, Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA). Ethical approval for this study was secured from London South Bank University, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the University of Reading and locally from the IIN. Written informed consent was obtained from all household heads or guardians.

The survey instruments included information on demographics, household composition, socio‐economic characteristics of families, food security, food consumption, hygiene, perceptions of psychosocial well‐being, anthropometric data for children and many other issues. Many of these measures were based on composite scores or scales adapted from previous research. For example, socio‐economic characteristics were measured using a composite wealth index score (ranging from 0 to 100) developed by the World Bank that accounts for services such as drinking water and electricity as well as housing quality and consumer durables (Filmer & Pritchett 2001). Household food consumption was calculated by dividing the total monthly food consumption by the total number of members living in the home. Food security was measured using a scale consisting of a series of 18 standardised questions from the Food Insecurity and Hunger Module that were adapted for Peru (Vargas & Penny 2010). Lastly, the hygiene environment was characterised using an eight‐question scale that measures the cleanliness of the child's living environment.

When conducting analyses to determine the impact of father presence on children's nutritional status, we considered a number of Young Lives variables including marital status (collinear with paternal presence), consumer durables and housing quality (collinear with wealth index) and maternal education (also collinear with wealth index). We felt that in most instances, the amount of formal education a mother received had been established before marriage and was not necessarily influenced by the father's presence in the home. In numerous instances, we used composite measures (e.g. hygiene environment) rather than a single variable such as the use of soap because composite measures are often better at capturing broad constructs such as socio‐economic status and hygiene. Other measures we included in our analyses were a 20‐item scale of maternal mental health, whether the father played frequently with his child and whether the mother received alimony. However, none of these variables was associated with nutritional status.

With respect to the measure of paternal presence, in R1 and in R2, respondents (usually the mother of the index child) were asked, ‘how often does the biological father see his child’? We considered ‘daily or weekly contact during both rounds’ as the group of children who were least at risk for undernutrition and ‘did not see their father daily or weekly either round’ as those who were at most risk. Children who saw their fathers ‘daily or weekly R1, not R2’ and ‘daily or weekly R2, not R1’ were thought to be at moderate risk of chronic undernutrition. As noted previously, there are a variety of reasons fathers may not see their children including migration, marital disruption and death, and these may affect children's nutritional status in different ways. However, the Young Lives database does not contain information about why fathers did not see their children.

HAZ at 5 years of age was used as the outcome indicator because it reflects the long‐term impact of poor diet and infection and is more prevalent than other indices of undernutrition in Latin America (Lamb et al. 1988; Johnson & Rogers 1993; Frongillo et al. 1997; Hwang & Lamb 1997; Joshi et al. 1999; Clarke et al. 2000; Kurz & Johnson‐Welch 2000; Lang & Zagorsky 2001; Chopra 2003; Cespeda et al. 2004; Frank & Wildsmith 2005; Madhavan & Townsend 2007; Crookston et al. 2010). When considering determinants of resiliency, we created a binary variable (stunting) from the continuous variable HAZ. Stunting was defined as HAZ less than −2.0 standard deviations below the mean of the international reference standard. Anthropometric indicators were calculated using the latest World Health Organization International Growth Reference standard (World Health Organization 2006). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The conceptual framework for this study guided our analyses. Namely, we examined the relationship between paternal presence and children's nutritional status. Our intent was to determine if paternal presence was associated with nutritional status after adjusting for context, environment, diet and disease. We used mixed effects regression models (MIXED and GLIMMIX procedures in SAS) to account for the effects of cluster sampling. Variables were retained or dropped from the model based on P‐values (<0.1). Model estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for retained variables. We also examined how resources and individual, family and community context might explain why some children from father‐absent homes were not stunted (‘resilient children’). For these analyses, we treated the outcome (nutritional status) in a binary fashion (stunted vs. not stunted). We calculated odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs for retained variables. We evaluated models for interaction as well as compliance with statistical assumptions associated with mixed effects procedures. No interaction terms were retained based on P‐values of <0.1, whereas our results indicated that there was a strong association between partner status (married, permanent union, divorced, separated, single, widowed) and paternal presence. We found no association between partner status and nutrition; hence, it was not included in our final regression model.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

On average, mothers in this sample had 7.8 years of schooling. While households were generally poor (scoring 43 out of 100 on the wealth index), on the whole, they were not extremely impoverished. Nearly two thirds of study participants lived in urban areas.

Family structure

Four in five children saw their fathers on a daily/weekly basis in both R1 and R2 (Table 1). Of the 20% who did not, 7.8% saw their fathers daily/weekly in R1 (but not R2), 4.3% saw them daily/weekly in R2 (but not R1) and 7.5% did not see them daily/weekly in either round. With respect to nutritional status, on average, children were slightly more than mildly stunted at R1 (HAZ = −1.3). Stunting at R2 was more pronounced (HAZ = −1.5).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants as well as father presence and nutritional status

| Independent variable* | n | % mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Child's sex (male) † | 925 | 50.1% |

| Child's age (months) † | 1846 | 12.0 (3.5) |

| Mother's age (years) † | 1843 | 27.1 (6.8) |

| Mother's education (years) | 1840 | 7.8 (4.5) |

| Wealth Index (0–100) ‡ | 1845 | 43.0 (14.0) |

| Site (rural) | 639 | 34.6% |

| Father present § | ||

| Daily/weekly both rounds | 1464 | 80.4% |

| Daily/weekly round 1, not round 2 | 142 | 7.8% |

| Daily/weekly round 2, not round 1 | 78 | 4.3% |

| Did not see father daily/weekly either round | 137 | 7.5% |

| HAZ round 1 † | 1825 | −1.3 (1.3) |

| HAZ round 2 | 1836 | −1.5 (1.1) |

Unless otherwise noted, data come from round 2 when children were 5 years of age.

Data come from round 1 when children were 1 year of age.

‡ Wealth index is a composite measure of 19 variables: four that measure housing quality, 11 that measure possession of consumer durables and four that measure access to services including electricity, water, sanitation and cooking fuel. The higher the value of the wealth index, the greater the wealth is.

Data come from both round 1 and round 2. HAZ, height‐for‐age z‐score; SD, standard deviation.

In almost all households (95.4%) where fathers saw their children daily or weekly (both rounds), parents were either married or in permanent union (results not shown). In urban areas, more than three quarters of parents from homes where fathers did not see their children daily or weekly in either round, were either divorced/separated (38.5%) or single/widowed (38.5%). Grandparents were more likely to reside in the home if the father did not see his child on a daily or weekly basis (results not shown). It was not possible to determine whether grandparents moved into the household because fathers were frequently absent or whether grandparents moved in prior to paternal departure. In rural areas, more than 90% of parents whose fathers did not see their children daily or weekly in either round were either divorced/separated (59.3%) or single/widowed (32.2%). In rural areas, there was a dose‐response relationship between paternal presence and grandparents living in the home – grandparents were most likely to live with the child if the child did not see his or her biological father on a daily/weekly basis in either round. There were large differences in numbers of older siblings. Children whose fathers saw them regularly in infancy and childhood had, on average, 2.6 siblings, whereas children who did not see fathers regularly at either time period had only one sibling (P < 0.0001).

Child support

The amount of child support fathers provided differed depending on father absence. Those who saw their children on a regular basis during infancy (but not childhood) were the most likely to provide child support (results not presented). Failure to provide child support was high – according to mothers' reports, more than four in five fathers who did not see their children on a daily/weekly basis in either round failed to provide support. Even so, frequent contact during infancy (but not childhood) doubled the likelihood that households received child support (28.7% vs. 14.3%).

Paternal presence and nutritional status

The mixed linear regression model (Table 2) tests for an independent effect of paternal presence on nutritional status (HAZ) after accounting for the impact of other contextual factors that could influence nutritional status. In this model, HAZ at age 5 is treated as a continuous variable. As hypothesised, paternal presence was associated with nutritional status. When compared with children who saw their fathers on a daily or weekly basis during infancy (1 year of age) and childhood (5 years of age), children who did not see their fathers regularly at either round had significantly lower HAZ (P = 0.0094). Results also suggest that children who saw their fathers during childhood (but not infancy) had better HAZ scores than children who saw their fathers in infancy and childhood (0.23 z‐score, P = 0.0388).

Table 2.

Estimates from mixed linear regression model for predictors of height‐for‐age z‐score at age 5 among Peruvian children (n = 1672)

| Independent variable* | Estimate | P‐value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.59 | – | – |

| Context | |||

| Child's age (months) † | 0.01 | 0.0698 | 0.00, 0.02 |

| Mother's age (years) † | 0.01 | 0.0008 | 0.01, 0.02 |

| Wealth index in quintiles | |||

| 1 (wealthiest) | 0.33 | 0.0004 | 0.15, 0.51 |

| 2 | 0.27 | 0.0020 | 0.10, 0.44 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.0382 | 0.01, 0.34 |

| 4 | −0.03 | 0.6750 | −0.11, 0.17 |

| 5 (poorest) | – | – | – |

| Number of siblings † | −0.14 | <0.0001 | −0.18, −0.10 |

| Father present ‡ | |||

| Daily/weekly both rounds | – | – | – |

| Daily/weekly round 1, not round 2 | 0.02 | 0.8285 | −0.15, 0.19 |

| Daily weekly round 2, not round 1 | 0.23 | 0.0388 | 0.01, 0.46 |

| Did not see father daily/weekly either round | −0.23 | 0.0094 | −0.41, −0.06 |

| Site † | |||

| Rural | – | – | – |

| Urban | 0.22 | 0.0080 | 0.06, 0.39 |

| Health and hygiene environment | |||

| Self‐reported health of child † | |||

| Same as other children | 0.15 | 0.0466 | 0.00, 0.29 |

| Better than other children | 0.30 | <0.0001 | 0.16, 0.45 |

| Worse than other children | – | – | – |

| Hygiene environment (0–8 score, 0 = very clean) | −0.09 | <0.0001 | −0.12, −0.06 |

Variables considered but not retained in the model include the following: child's sex, mother's mental health, grandparents in home, father plays frequently with child, mother received alimony, food secure and monthly household per capita food consumption. Food security is a composite of 18 variables derived from standardised questions from the Food Insecurity and Hunger Module, adapted for Peru (Vargas & Penny 2010). *Unless otherwise noted, data come from round 2 when children were 5 years of age. †Data come from round 1 when children were 1 year of age. ‡Data come from both round 1 and round 2. CI, confidence interval.

Other significant predictors of HAZ were wealth, mother's age, number of siblings, site, hygiene environment and self‐reported health of the child (Table 2). Each of these operated in the expected direction. Wealthier, urban children whose mothers were older, who had fewer siblings, whose ambient conditions were clean, and whose health was the same as or better than other children their age had higher z‐scores.

Resources and context explain resiliency

In Table 3, we present results of our analyses for a subset of the overall sample, namely, children who did not see their fathers at either round but who were not stunted at 5 years of age (i.e. HAZ > −2). A child's chances of not being stunted in spite of paternal absence at 1 and 5 years of age were considerably greater if he or she lived in an urban area (OR = 9.3), was from the wealthiest quintile (OR = 8.7) and lived in a food secure environment (OR = 3.8). Compared with children from the two wealthiest quintiles, children who came from the middle, poor and poorest quintiles were considerably more likely to be stunted. We hypothesised that other factors were associated with the likelihood of having a HAZ greater than −2. These included child's age, mother's mental health, presence of grandparents in the home, number of siblings, father's play with his children, alimony support, hygiene environment, monthly household food consumption and self‐reported health of child. However, none of these factors was important in explaining good nutritional status among children who did not see their father daily/weekly during infancy and childhood.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from logistic regression model for not stunted (1 = yes, 0 = no) among Peruvian children who did not see their father at both age 1 and age 5 (n = 137)

| Independent variable* | Odds ratio | P‐value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context | |||

| Site † | |||

| Rural | – | – | – |

| Urban | 9.32 | 0.0002 | 2.91, 29.88 |

| Wealth index in quintiles ‡ | |||

| 1 (wealthiest) | 8.73 | 0.0223 | 1.37, 55.63 |

| 2 | 2.88 | 0.2143 | 0.54, 15.48 |

| 3 | 0.49 | 0.3584 | 0.10, 2.28 |

| 4 | 0.60 | 0.3973 | 0.18, 1.98 |

| 5 (poorest) | – | – | – |

| Food security § | |||

| Food secure | |||

| Yes | 3.79 | 0.0369 | 1.09, 13.21 |

| No | – | – | – |

Variables considered but not retained in the model include the following: child's age, child's sex, mother's age, mother's mental health, grandparents in home, number of siblings, father plays frequently with child, mother received alimony, hygiene environment, monthly household per capita food consumption, self‐reported health of child. *Unless otherwise noted, data come from round 2 when children were 5 years of age. †Data come from round 1 when children were 1 year of age. ‡Wealth index is a composite measure of 19 variables: four that measure housing quality, 11 that measure possession of consumer durables and four that measure access to services including electricity, water, sanitation and cooking fuel. The higher the value of the wealth index, the greater the wealth is. §Food security is a composite of 18 variables derived from standardised questions from the Food Insecurity and Hunger Module, adapted for Peru (Vargas & Penny 2010). CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

We tested two hypotheses: (1) paternal presence is associated with better nutritional status (HAZ) after accounting for the impact of other factors that may influence nutritional status such as resources and individual, family and community context, and (2) resources and individual, family and community context explain why resilient children are not stunted.

Paternal presence and nutritional status

Findings from this research indicate that paternal presence when children were 1 and 5 years old was associated with HAZ at 5 years of age. These results are similar to findings from previous research that demonstrate that children from single‐parent homes or cohabiting households are at higher risk of undernutrition after adjusting for income (Sahn & Alderman 1997; Bronte‐Tinkew & DeJong 2004). A study from South Africa reports that children who saw their fathers less than weekly had higher rates of malnutrition than children who saw them more frequently (Chopra 2003). A recent study from Mexico showed that father absence was related to illness in children (Schmeer 2009).

Our results show that in addition to paternal presence, maternal age and wealth were significant predictors of HAZ. These findings are consistent with previous research (Frongillo et al. 1997; Sahn & Alderman 1997; Begin et al. 1999; Ashiabi & O'Neal 2007; Semba et al. 2008). For example, Ashiabi & O'Neal (2007) found that American adults' quality of parenting was positively associated with the overall health status of adolescents. Semba et al. (2008) report that for both Indonesia and Bangladesh, increased maternal age was associated with increased prevalence of stunting among children less than 5 years of age – a finding that differs from our own. They also report that in both countries, decreases in weekly per head household expenditures contributed to an increased prevalence of stunting. Frongillo et al. (1997) found that in Latin American countries, higher health expenditures reduced stunting but in Africa and Asia, the reverse was true. Furthermore, Peruvian children in this study who grew up with more siblings were at increased risk of lower HAZ, a finding that has been substantiated by others (Bradley et al. 1994; Bronte‐Tinkew & DeJong 2004). Adjusting for known predictors of poor nutritional status strengthens our conclusion that the association between paternal presence and HAZ is not spurious.

Children in this study who lived in urban areas had HAZ scores that were a quarter of a point higher than children in rural settings, even after adjusting for potentially confounding demographic characteristics. A number of factors may help explain this divide, including greater professional opportunities for parents in urban areas, increased income, better access to health care, more egalitarian workforce composition and more equitable responsibility for childcare. Additionally, as Jankowiak (1992) notes, expectations about how fathers should contribute to childrearing likely vary between urban settings and rural settings. Fathers in urban areas may place new importance on intimate relations between themselves and their children or may be expected to assume a more nurturing, less authoritarian role at home.

With respect to timing of paternal absence, it is not clear whether absence early or late in the child's life has the most damaging effect on children's nutritional status. There is considerable evidence that absence during infancy is especially detrimental. In England, Ermisch & Francesconi (2001) found that children who experienced disruptions before the age of 5 were at greater risk of low academic achievement, reduced economic productivity and smoking than children who experienced later disruption. Studies from the industrialised world have shown that when fathers play a major role in their children's lives at birth, children score higher on intelligence tests and have fewer behavioural problems (Russell‐Brown et al. 1992). Birth may represent the time when fathers' expectations for their offspring are the highest; thus, fathers may be most motivated to become involved in their children's lives during infancy. Furthermore, as Sigle‐Rushton & McLanahan (2006) have argued, many of the developmental and social processes that are critical to children's health and overall development occur when children are very young. Children who are deprived of critical resources during this period may be at particularly high risk and fathers' active involvement in infant care may reduce some of the disadvantages that accompany the first few years of life.

In contrast to the findings reported above, our results suggest that infrequent contact in childhood is a more important determinant of HAZ than infrequent contact during infancy. A number of studies lend credence to the notion that paternal presence during childhood is more closely linked to a variety of outcomes than presence in infancy. In many societies, fathers have little to do with very young children (Lewis & Lamb 2004), especially when men's roles are limited to breadwinning rather than nurturing. Some psychosocial development literature indicates that infants may not become attached to their fathers in the first year of life, regardless of how much time infants spend with them (Cox et al. 1992). Even so, there is limited evidence that paternal absence during childhood is more (or less) important than absence in infancy (Sigle‐Rushton & McLanahan 2006).

Our study documents a clear relationship between paternal presence and HAZ. However, findings are somewhat unusual because children who saw their fathers on a daily/weekly basis during childhood (but not infancy) had higher HAZ than children who saw their fathers daily/weekly during both rounds of data collection. It may be that always‐present fathers – including fathers who are on hand during infancy – divert resources away from children. In contrast, mothers whose partners are absent, some or most of the time, may exert greater control over household finances. There is mounting evidence that father‐led homes funnel economic resources toward expenditures that are detrimental to health, including alcohol and tobacco, whereas mother‐led homes favour children's nutritional needs (Onyango et al. 1994; Kurz & Johnson‐Welch 2000). Indeed, several authors (Johnson & Rogers 1993; Rogers 1996) have shown that children in households headed by mothers experience less malnutrition compared with households headed by fathers, largely because of women's tendency to focus greater financial resources on children. In our study, grandparents were much more likely to reside in homes where fathers did not see their children on a daily/weekly basis. It may be that children who grow up in father‐absent, grandparent‐present homes benefit from extra, more favourable attention that leads to improved health. Even so, in our multivariate analyses, grandparental presence was not significantly associated with HAZ when children were 5 years old.

Resources, context and resiliency

We found that resilient children were more likely to live in urban areas, come from the wealthiest quintile and benefit from a food secure environment. None of these findings is particularly surprising. As noted previously, urban areas often provide greater professional opportunities for parents and children, increased income, better access to health care and potentially more equitable responsibility for raising children. Likewise, greater access to resources can lead to greater food security, which in turn contributes to nutritional status. In short, hypotheses 1 and 2 support our conceptual framework – paternal presence is associated with nutritional status but individual, family and community context have a direct effect on nutritional status as well.

This study has several limitations. Perhaps most importantly, we do not know why fathers were absent; therefore, we cannot determine whether children whose fathers were absent because of marital conflict fared worse nutritionally than children whose fathers' work kept them from seeing them. Previous research suggests that children from father‐absent homes fared better if the reason for absence was work, not domestic tension (Santrock 1972, 1977). Relative to non‐working fathers (whether absent or present), fathers who are employed away from home may be better equipped to support their children through remittances for shelter, food, clothing and education (Madhavan & Townsend 2007; Schmeer 2009). In Brazil, Carvalhaes et al. (2005) found that partner absence was associated with higher rates of malnutrition and that this relationship persisted even after adjusting for parents' financial contributions. Clearly, a more nuanced measure of paternal absence is needed. The R3 questionnaire includes information about why fathers were absent and will be reported in subsequent papers once these data are available for analysis. A second limitation is the lack of more comprehensive measures of fathers' accessibility as well as involvement with their children (Lamb et al. 1988; Hwang & Lamb 1997). Third, information on diet is limited to monthly, household food consumption, not the daily food consumption patterns of individual children such as can be obtained using a 24‐hour recall. However, these data have been collected in R3 and will be reported in subsequent analyses. Fourth, 95% CIs for our resiliency analyses are wide owing to the small number of children who did not see their fathers at either round but whose HAZ > −2. Even so, given the lack of resiliency analysis in the literature on paternal presence, our findings are important.

Our findings suggest several directions for future research including development of a more nuanced measure of paternal involvement and support for additional longitudinal studies on the impact of paternal absence during infancy, childhood and adolescence – especially from less‐industrialised countries where there is a paucity of information about the impact of fathers on the health of infants and children. In addition, the literature would benefit from additional research on resilient children – what can be learned from father‐absent families where children demonstrate favourable outcomes? Such outcomes might extend beyond nutrition to include health and educational achievement. Research of this nature can provide insight into how ‘at‐risk’ families achieve positive outcomes for their children.

This research suggests several avenues for reducing the deleterious effects of paternal absence on children's nutritional status. First, government and non‐governmental efforts to improve health should focus on actively involving fathers. Gender stereotypes often cast fathers as uninvolved, unsympathetic and incapable of providing care. Further, programs designed to improve caregiving often target mothers, even when fathers are present. In the developing world, malnutrition, and in particular, stunting, remains a significant public health challenge, especially for children from single‐parent households. If programs and policies are to successfully improve the care children receive, they must be built on a fuller understanding of paternal absence and how this interacts with the variety of other factors – biological, social and otherwise that put children at risk.

Sources of funding

Young Lives is core‐funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. Substudies are funded by the Bernard van Leer Foundation, the Inter‐American Development Bank (in Peru), the International Development Research Centre (in Ethiopia), and the Oak Foundation. The views expressed here are those of the authors. They are not necessarily those of the Young Lives project, the University of Oxford, DFID or other sources of funds. Additional funding for this research came from Boston University, the University of Utah, the University of California San Diego and Brigham Young University.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

KD conceptualised and designed the research, interpreted data and was the primary author on all drafts of the manuscript. BC conceptualised the analyses and analysed data. HM and JW conducted literature reviews. MP and SC assisted with the design of data analysis and provided context for results. All authors interpreted data and assisted in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Crookston's work on this paper was carried out while he was an Assistant Professor at the University of Utah, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine.

References

- Agarwal D.K., Upadhyay S.K. & Agarwal K.N. (1989) Influence of malnutrition on cognitive development assessed by Piagetian tasks. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 78, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiabi G.S. & O'Neal K.K. (2007) Is household food insecurity predictive of health status in early adolescence? A structural analysis using the 2002 NSAF data set. Californian Journal of Health Promotion 5, 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Begin F., Frongillo E.A. & Delisle H. (1999) Caregiver behaviors and resources influence child height‐for‐age in rural Chad. Journal of Nutrition 129, 680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R.E., Allen L.H., Bhutta Z.A., Caulfield L.E., de Onis M., Ezzati M. et al (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 371, 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R.H., Whiteside L., Mundfrom D.J., Casey P.H., Kelleher K.J. & Pope S.K. (1994) Early indications of resilience and their relation to experiences in the home environments of low birthweight, premature children living in poverty. Child Development 65, 346–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte‐Tinkew J. & DeJong G. (2004) Children's nutrition in Jamaica: do household structure and household economic resources matter? Social Science & Medicine 58, 499–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhaes M., Benicio M.H.D. & Barros A.J.D. (2005) Social support and infant malnutrition: a case‐control study in an urban area of Southeastern Brazil. British Journal of Nutrition 94, 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cespeda R., Davila E., Fort A., Ulloa L. & Castro Z. (2004) Perú: encuesta demográfica y de salud familiar. (ed Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática). Dirección Nacional de Censos y Encuestas. Dirección de Técnica de Demografía e Indicadores Sociales, Lima, Perú.

- Chopra M. (2003) Risk factors for undernutrition of young children in a rural area of South Africa. Public Health Nutrition 6, 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L., Joshi H. & Di Salvo P. (2000) Children's family change: reports and records of mothers, fathers and children compared. Population Trends 102, 24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M., Owen M., Henderson V. & Margand N. (1992) Prediction of infant‐father and infant‐mother attachment. Developmental Psychology 28, 474–483. [Google Scholar]

- Crookston B.T., Dearden K.A., Alder S.C., Porucznik C.A., Stanford J.B., Merrill R.M. et al (2010) Impact of early and concurrent stunting on cognition. Journal of Maternal and Child Nutrition doi:10.1111/j.1740‐8709.2010.00255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle P.L., Black M.M., Behrman J.R., Cabral de Mello M., Gertler P.J., Kapiriri L. et al (2007) Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet 369, 229–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch J. & Francesconi M. (2001) Family structure and children's achievements. Journal of Population Economics 14, 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D. & Pritchett L. (2001) Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data or tears: an application to educational enrolments in states of India. Demography 38, 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank R. & Wildsmith E. (2005) The grass widows of Mexico: migration and union dissolution in a binational context. Social Forces 83, 919–947. [Google Scholar]

- Frongillo E.A., de Onis M. & Hanson K.M.P. (1997) Socioeconomic and demographic factors are associated with worldwide patterns of stunting and wasting of children. Journal of Nutrition 127, 2302–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glewwe P. & King E. (2001) The impact of early childhood nutritional status on cognitive development: does the timing of malnutrition matter? World Bank Economic Review 15, 81–113. [Google Scholar]

- Grantham‐McGregor S., Pollitt E., Wachs T., Meisels S. & Scott K. (1999) Summary of the scientific evidence on the nature and determinants of child development and their implications for programmatic interventions with young children. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 20, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C.P. & Lamb M.E. (1997) Father involvement in Sweden: a longitudinal study of its stability and correlates. International Journal of Behavioral Development 21, 621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowiak W. (1992) Father‐child relations in urban China In: Father‐child Relations: Cultural and Biosocial Contexts (ed. Hewlett B.S.), pp 345–363. De Gruyter: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson F.C. & Rogers B.L. (1993) Children's nutritional‐status in female‐headed households in the Dominican‐Republic. Social Science & Medicine 37, 1293–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi H., Cooksey E., Wiggins R., McCulloch A., Verropoulou G. & Clarke L. (1999) Diverse family living situations and child development: a multi‐level analysis comparing longitudinal evidence from Britain and the United States. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 13, 292–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kurz K. & Johnson‐Welch C. (2000) Enhancing Nutrition Results: The Case for a Women's Resources Approach. International Center for Research on Women: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M.E., Hwang C.P., Broberg A., Bookstein F.L., Hult G. & Frodi M. (1988) The determinants of paternal involvement in primiparous Swedish families. International Journal of Behavioral Development 11, 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Lang K. & Zagorsky J.L. (2001) Does growing up with a parent absent really hurt? Journal of Human Resources 36, 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. & Lamb M. (2004) Fathers: the research perspective In: Supporting Fathers: Contributions from the International Fatherhood Summit 2003 (ed. Lemieux D.), pp 44–77. Bernard van Leer Foundation: The Hague, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan S. & Townsend N. (2007) The social context of children's nutritional status in rural South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 35, 107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyango A., Tucker K. & Eisemon T. (1994) Household headship and child nutrition: a case study in Western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine 39, 1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer J., Rogers S. & Rahman A. (2004) The epidemiology of good nutritional status among children from a population with a high prevalence of malnutrition. Public Health Nutrition 7, 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayhan M., Khan S.H. & Shahidullah M. (2007) Impacts of bio‐social factors on morbidity among children aged under‐5 in Bangladesh Asia‐Pacific Population Journal 22, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers B.L. (1996) The implications of female household headship for food consumption and nutritional status in the Dominican Republic. World Development 24, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Russell‐Brown P., Engle P. & Townsend J. (1992) The Effects of Early Childbearing on Women's Status in Barbados. International Center for Research on Women: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Sahn D.E. & Alderman H. (1997) On the determinants of nutrition in Mozambique: the importance of age‐specific effects. World Development 25, 577–588. [Google Scholar]

- Santrock J.W. (1972) Relation of type and onset of father absence to cognitive development. Child Development 43, 455–469. [Google Scholar]

- Santrock J.W. (1977) Effects of father absence on sex‐typed behaviors in male children: reason for absence and age of onset of absence. Journal of Genetic Psychology 130, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeer K. (2009) Father absence due to migration and child illness in rural Mexico. Social Science & Medicine 69, 1281–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba R., de Pee S., Sun K., Sari M., Akhter N. & Bloem M. (2008) Effect of parental formal education on risk of child stunting in Indonesia and Bangladesh: a cross‐sectional study. Lancet 371, 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigle‐Rushton W. & McLanahan S. (2006) Father absence and child well‐being: a critical review In: The Future of the Family (eds Moynihan D., Smeeding T. & Rainwater L.), pp 116–158. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas S. & Penny M.E. (2010) Measuring food insecurity and hunger in Peru: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of an adapted version of the USDA's Food Insecurity and Hunger Module. Public Health Nutrition 13, 1488–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora C.G., Adair L., Fall C., Halla P.C., Martorell R., Richter L. et al (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 371, 340–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson I., Huttly S.R.A. & Fenn B. (2006) A case study of sample design for longitudinal research. Young Lives International Journal of Social Research Methodology 9, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2006) Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatrica 450 (Suppl), 76–85. 16817681 [Google Scholar]