Abstract

Despite being an important component of Pakistan's primary health care programme, the rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months remain among the lowest in the world. Low levels of literacy in women and deeply held cultural beliefs and practices have been found to contribute to the ineffectiveness of routine counselling delivered universally by community health workers in Pakistan. We aimed to address this by incorporating techniques of cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) into the routine counselling process. We conducted qualitative studies of stakeholders' opinions (mothers, community health workers, their trainers and programme managers) and used this data to develop a psycho‐educational approach that combined education with techniques of CBT that could be integrated into the health workers' routine work. The workers were trained to use this approach and feedback was obtained after implementation. The new intervention was successfully integrated into the community health worker programme and found to be culturally acceptable, feasible and useful. Incorporating techniques of CBT into routine counselling may be useful to promote health behaviours in traditional societies with low literacy rates.

Keywords: breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding promotion, behavior change communication, cognitive behavior techniques, child nutrition, low income countries

Introduction

Exclusive breastfeeding, defined as the practice of feeding only breast milk including expressed breast milk (water, breast milk substitutes, other liquids and solid foods excluded) up to 6 months, and the introduction of complementary foods and continued partial breastfeeding thereafter, has been recommended by experts (World Health Organization 2002b; American Academy of Pediatrics 2011) and endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF (World Health Organization 2003, 2011). The recommendations came in view of the substantial health, social and economic benefits of exclusive breastfeeding including lower infant morbidity and mortality from diarrhoea and other infections (Popkin et al. 1986; Victora et al. 1987; Morrow et al. 1992; Newburgh et al. 1998; World Health Organization 2002a).

Key messages

-

•

Exclusive breastfeeding is a very cost‐effective disease‐prevention practice and a global priority.

-

•

Low rates, even where counselling is available, indicate that a one‐size‐fit‐all strategy for intervention has not been successful.

-

•

Low maternal literacy rates and deep‐rooted cultural beliefs and practices may hinder health education in many populations and cultural awareness in interventions has been advocated.

-

•

However, simply understanding the culture may not be enough. Specialised psycho‐educational techniques such as those derived from cognitive behavioural therapy may provide useful and feasible tools to modify strongly held cultural beliefs that impede the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in many societies.

The promotion of exclusive breastfeeding has become a cornerstone of maternal and child health policy and practice in many countries and a number of effective counselling approaches have been developed (Morrow et al. 1999; Fairbank et al. 2000; Haider et al. 2000; Kramer et al. 2001; Bonuck et al. 2002; Kishore et al. 2007; Gijsbers et al. 2008). In Pakistan, counselling for exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life is an important component of the Primary Care Program, delivered by trained community health workers (CHWs) to women in their homes. Despite the programme being operative for over three decades and achieving success in many health indicators (such as antenatal care in women and immunisation rates in children; Oxford Policy Management 2009), the rates of exclusive breastfeeding in Pakistan remain among the lowest in the world. Only 55% of Pakistani infants are exclusively breastfed in the first month of their lives and this rate drops to 8% at 6 months (Agha et al. 2007; Kishore et al. 2007; National Institute of Population Studies 2007). Two factors have been found to be important contributors: low literacy, and especially in traditional communities, deeply ingrained patterns of cultural beliefs and practices, which conflict with exclusive breastfeeding guidelines (National Institute of Population Studies 2007).

In a previous study in rural Pakistan, we had successfully trained CHWs to use techniques of cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) in an intervention targeting perinatal depression in disadvantaged rural women, aiming to improve their mood and level of infant care (Rahman 2007; Rahman et al. 2008). The intervention was successful in halving the rate of maternal depression and also led to significant improvement in uptake of contraception in the mothers and immunisation in the infants, and the time that both parents spent in play activities with the infant (Rahman et al. 2008). Feedback from the CHWs was that these techniques were very useful in communicating with ‘difficult to engage’ families (Rahman 2007).

Cognitive‐behavioural techniques and their relevance to breastfeeding counselling

CBT is a structured form of dialogue between therapist and client that aims to alter the cycle of unhelpful or non‐healthy thinking (cognitions) and the associated undesirable feelings and actions (behaviour). It has been used for a variety of psychological problems such as anxiety and depression but also more general public health problems such as smoking and obesity (Sykes & Marks 2001; Golay et al. 2004). Our previous work demonstrated that CBT techniques can be taught to non‐specialist health workers to bring about change in specific problem areas in maternal and child health in rural Pakistan. These techniques included:

-

•

Developing a therapeutic relationship – a trusting, safe, therapeutic alliance, not just with the mother but the whole family.

-

•

Collaborating with the family – working with families on an equal partnership, each party bringing something to the relationship. The health worker brings skills and knowledge of health issues, the mother and family bring their own experience and resources.

-

•

Using guided discovery – a style of engagement to both gently probe for the individual and family's health beliefs and problems faced in meeting health care demands, and to stimulate alternative ideas and solutions. It involves exploring and reflecting on styles of reasoning and thinking and possibilities to think and act differently. It makes effective use of ‘imagery’ techniques – culturally appropriate illustrations are used to facilitate work with mothers and families. Using characters depicting mothers, infants and other family members, the illustrations help the CHWs and families discuss deeply held beliefs without alienating them. The images are also helpful with less‐literate women.

-

•

Putting knowledge into practice and behavioural activation – the mother tries things out in between counseling sessions, putting what has been learned into practice. Referred to as homework, this paves the way for a long‐term behaviour change. Diaries are used to record progress or problems. CHWs work with key family members to motivate and encourage mothers to take small steps and then build on these.

-

•

Problem solving – Problems and barriers in putting new knowledge and skills into practice are analysed. The health workers use peer‐supervision sessions to brainstorm for possible solutions and introduce these to mothers and families.

The aim of this study was to explore the integration of CBTs in the routine breastfeeding counselling practice of CHWs in a traditional, low‐literacy setting in rural Pakistan with low rates of exclusive breastfeeding. We investigated the socio‐cultural and health service delivery context of exclusive breastfeeding and used this data to incorporate CBT techniques to the routine breastfeeding counselling by CHWs. We trained community health workers in using this approach and obtained feedback after they had practised these in the community for some months.

Materials and methods

This study was the formative phase of a cluster‐randomised trial to test the effectiveness of a psycho‐educational intervention in a socio‐economically disadvantaged district in the north‐west of Pakistan (Trial registered ISRCTN45752079).

Setting

The study was conducted in the district of Mansehra located in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwah (formerly North Western Frontier) Province of Pakistan. Mansehra is a typical resource‐poor district with an infant mortality 78/1000 and under‐five mortality of 94/1000 live births. The overall literacy rate is 51% in men and 22% in women (Government of Pakistan 1998). The economy is mainly agrarian with small land holdings cultivated for subsistence crops. The society is deeply conservative, with a very low emphasis on the education of girls, only 50% of girls enrolling for school and 10% completing primary education.

Over 70% of deliveries take place at home. The primary health care system is well established in Mansehra. The first level consists of a basic health unit that covers a population of 12 000–20 000, has 2–5 facility‐based staff, and 15–20 community health care workers called Lady Health Workers (LHWs). LHWs are selected from the local community, have passed at least 8 grades of schooling and deliver basic health and preventive education on a range of issues during their visits to the households. One LHW covers a population of 1000, visits each household once every month and gives special focus to maternal, newborn and child health and family planning. These workers undergo a classroom teaching of 3 months followed by practical training in the field for 12 months. The Lady Health Workers' Programme (LHWP) covers 85% of Mansehra's population. Counselling for exclusive breastfeeding is an important component of the LHWs' training.

Study design

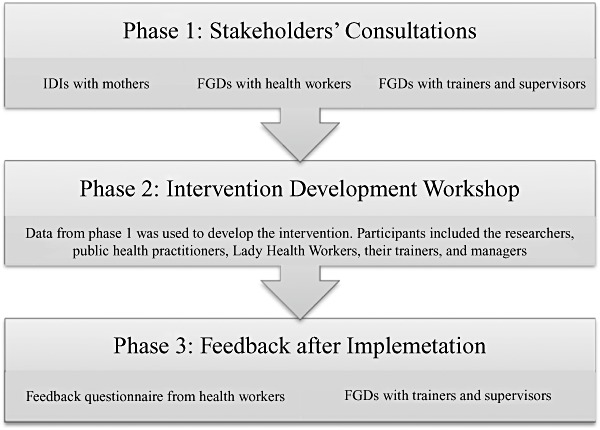

We used a methodology employed previously to integrate CBT techniques into the routine work of LHWs to treat women with perinatal depression (Rahman 2007). It consisted of the following phases: (1) stakeholders consultations, (2) intervention development and (3) implementation and feedback (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phases of the study (FGD, focus group discussion; IDI, in‐depth interview.).

Phase 1: stakeholders consultations

In this phase, we focused on gathering qualitative information from LHWs, their trainers and nursing mothers on existing cultural beliefs and practices about breastfeeding. Our objective was to get an in‐depth understanding of such beliefs and practices, to learn why current counselling was not effective and what was likely to work. The following methodologies were used:

-

1

In‐depth interviews were carried out with 12 mothers with infants up to 6 months of age. The mothers were selected purposively from a disadvantaged area so that they represented a heterogeneous group (in terms of age, parity, education and socio‐economic status). Local health workers, who are required to maintain a list of every pregnant and recently delivered woman in their locality, were consulted to recruit the sample. The health workers live locally and know the women and their families intimately, and were able to provide the information we needed to ensure that our sample represented the range of factors described above. The qualitative interviews were conducted in the women's home. Using a semi‐structured approach, the researcher tried to gain an understanding of social and cultural aspects of breastfeeding and explore beliefs, perceptions, attitudes and practices that prevented them from exclusively breastfeeding their infants. Detailed verbatim notes were made during the interview.

-

2

Focus group discussions (FGDs; n = 4) were conducted with purposively sampled LWHs (n = 30). The LHWs were recruited from four different localities in the district. We consulted the LHWs' supervisors to select LHWs of varying age and experience so that they represented a cross‐section of the LHW workforce in the study district. Most LHWs were themselves mothers and we attempted to understand the issues involved in counselling mothers for exclusive breastfeeding in their areas, focusing on difficulties they faced in accessing families. We attempted to understand the health workers' day‐to‐day activities and assessed how we could integrate our intervention into their routine counselling practice. The groups followed a semi‐structured format and served to guide the discussion while permitting maximum elaboration of participant response. Issues raised in one focus group were used as triggers for further ideas. Special care was taken by the experienced moderator to put LHWs at ease to allow them to communicate freely.

-

3

FGDs (n = 4), using the same themes, with all the district‐level trainers (n = 28) of the LHWs. These trainers were responsible for developing curriculum and organising trainings for LHWs. We also conducted face‐to‐face interviews with the national and deputy national manager of the programme who provided information on administrative and decision‐making processes for adoption of new innovations to the programme.

Phase 2: intervention development

This was carried out in a workshop that was attended by the researchers, public health practitioners, lady health workers, their trainers and managers. The data from different sources was compared and the main themes were corroborated and discussed. This allowed the participants to achieve an in‐depth understanding of the issues involved in exclusive breastfeeding practice and the current strategies to promote it. This information was used to develop and integrate the CBT techniques into the existing breastfeeding promotion materials used by the workers and their trainers and supervisors. A training of trainers guide, training manual and pictorial cue cards for the LHWs were developed. All material was scrutinised by the workshop participants to ensure that it was culturally and linguistically suitable and simple enough to be understood by LHWs and the mothers.

We involved the LHW programme trainers, administrators and managers in addition to experts in the intervention development process. This was important for two reasons: Firstly, to ensure that any modifications to existing practice incorporated their views and gained from their experience and knowledge. Secondly, to ensure that there was joint ‘ownership’ of the new intervention – this would facilitate the uptake of the new intervention by the programme.

Phase 3: implementation and feedback

As we wanted the intervention to be sustainable, we trained the existing LHW trainers to deliver the training to the LHWs. No extra training sessions were designed; the programme was integrated into the routine on‐the‐job training of the LHWs. Two hundred and thirty‐six LHWs working in 20 randomly selected Union Councils of District Mansehra received the training.

Following the training, and after they had had 3 months or more experience in the field, a random group of LHWs (n = 40) were assessed using a simple feedback questionnaire we had developed in our previous study. Their trainers (n = 28) were invited to attend FGDs (n = 4) while the managers were interviewed by the research team. The themes explored were (1) if the training succeeded in giving the LHWs new skills which they found useful in their work; (2) if it was culturally feasible to deliver these to the mothers under their care; (3) if the new skills developed helped in other areas of their work, and (4) if the intervention had the potential to be scaled up nationally. Both quantitative and qualitative feedback was obtained by independent assessors and the questionnaires were anonymous.

Data analysis

Tape‐recorded interviews and FGDs in Urdu were transcribed and the transcripts were read and coded by members of the research team. The note taker summarised notes on the same day of the discussion in the form of a table. Coded information from transcripts was compared with tables developed by the note taker, occasional discrepancies discussed with both members of the field team and a consensus opinion developed. The analysis of qualitative data was based on combination of inductive as well as a priori theory. Inductive analysis (Pope et al. 2000; Taylor‐Powell and Renner 2011) was performed on data from first phase by (1) becoming familiar with the data that included reading the notes, transcribing the FGDs; (2) initial categorisation of data by developing tables on themes emerging from the discussions; notes taken during the discussions as well as the transcripts were consulted for developing these categories to eliminate discrepancies; and (3) identifying patterns and connections within and between categories with the help of these tables.

Ethical approval was obtained from a local Institutional Review Board of the Human Development Research Foundation. The study conformed to good practice and to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was completed in 10 months from January to October 2009.

Results

Phase 1: stakeholders consultations

In‐depth interviews with mothers

Twelve mothers were interviewed; their ages ranged from 19–34 years, education in years, 0–12 years and number of children 1–6. The average time for each interview was 45 min. The data analysis yielded the following themes:

-

•

Lack of knowledge and reliance on traditional beliefs: While most women had been informed about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding by their LHW, almost all said that they believed more firmly in the traditional ‘wisdom’ handed down through generations. For example, it was common practice to give the newborn ghutti, a concoction containing honey, mixed with butter or ghee and often diluted with water or even saliva. Ghutti was most commonly given as prelacteal feed and may be given for the first several days. Honey was believed to have special powers to protect the baby against disease and to give it strength and ghutti was thought to be essential to clean the intestines. The women did not make a possible connection between infection, such as diarrhoea and this practice. Instead, they had a separate belief system to explain the diarrhoea (e.g. weak intestines or even bad breast milk). Another common practice was to discard the colostrums, believed to be harmful, before giving the infant its first feed. Another commonly reported belief was that around 3–4 months when the baby became more active, it needed more energy, which could only come from solid foods. This led to earlier weaning than recommended. It was evident that the women placed a lot of faith in these beliefs. These were often reinforced by the more experienced women in the clan.

Ghutti is essential to cleanse the newborn's stomach and protect him from illness. It is the tradition of our ancestors and is also part of our religion. (Mother from Kathai)

Bolhi (colostrums) is stagnant milk which is in the breasts since 9 months. It will be harmful for the baby just like stagnant water. (Mother from Bhirkund)

-

•

Perceptions of the mother and others about the insufficiency of breast milk: Many mothers attributed a host of signs to the perception that their breast milk was insufficient. For example, infant illnesses such as acute respiratory infection or diarrhoea were attributed to either an insufficiency of the breast milk or a ‘lack of strength’ of the breast milk. Irritability, crying or difficulty in latching was also perceived to be signs that the breast milk was insufficient. If their baby looked leaner compared to other babies (many of whom were bottle‐fed), this was again perceived to reflect insufficiency or lack of quality of breast milk.

When my baby keeps crying even after a feed, I think my milk is not sufficient to satisfy him. (Mother from Kallar)

My breasts don't feel heavy; therefore I know my milk is not sufficient for the baby. (Mother from Bhirkund)

I am a mother, and I can tell when my child is not sated, and is becoming weak. (Mother from Kathai)

A number of traditional remedies were practiced to enhance the quantity and quality of breast milk, e.g. adding cumin seed and its extract or cooked goat intestines to the woman's diet.

-

•

Lack of support from significant others and psychosocial distress: While many women felt they were well supported by family members during the 40‐day traditional confinement following childbirth (the Chilla period), most reported that they had to return to their duties immediately afterwards. Many women reported that they were overburdened with domestic as well as farm work, and did not have the time or energy to nurse the baby. Many reported that they felt tired and feared that breastfeeding would make them even weaker. Some reported vague symptoms such as body aches and pains or vaginal discharge, which convinced them that they were not fit to breastfeed. From our previous work with maternal depression, we suspected that a number of women with such symptoms would be suffering from psychological distress or even depression.

I started to bottle‐feed the baby after my chilla because there was lot of work to do and if I kept sitting and feeding the baby, who would do the work? (Mother from Baffa)

My mother stayed with me for the Chilla (40 days) but when she left I had to attend to my chores, and I found it difficult to feed the baby. I was often too tired. (Mother from Kallar)

Focus group discussions with stakeholders

The above themes were confirmed by the service providers to be the most relevant to women who did not respond to routine counselling. In addition, the following themes, from a service delivery perspective, emerged which were felt to hinder the counselling process:

-

•

Literacy level of the clientele: The LHWs felt that it was difficult to counsel women who were not literate. Such women were less receptive to the health education and did not engage well with counselling. The providers felt that women who were non‐literate generally came from poorer backgrounds, and these were the families most likely to adhere strongly to traditional ways of thinking that were resistant to change. The LHWs often felt frustrated working with such families. It was felt that counselling alone was not sufficient to engage with them and the need to incorporate other strategies into the routine counselling practice was stressed.

Our workers are doing their best . . . perhaps they need more powerful messages to convince the old‐fashioned mothers and families. (Senior trainer LHWP)

-

•

Conflicting advice from other practitioners: It was reported by a number of the service providers that other medical practitioners, especially private practitioners and sometimes even primary care physicians, were advising mothers to initiate formula preparations, without any valid medical reason. Because the status of these medical practitioners was perceived to be higher than that of a LHW, their advice was often taken more seriously.

We have observed that many doctors prescribe formula or other top‐up feed. People would not believe in LHW if their doctor gave a conflicting advice. (Manager LHWP)

-

•

Concerns about the workload of LHWs: There were concerns about the heavy workload of the LHWs and it was voiced that there would be little space in the schedule, and the training programme, for any additional activity. It was felt that integrating any additional material into the existing programme would be important for its uptake as well as longer term sustainability.

Phase 2: intervention development

The workshop participants were presented with the themes emerging from the data and this new information was triangulated with existing knowledge and theory to develop key recommendations that would guide modifications to the counselling process. The following recommendations and modifications emerged from this process:

Deliver key messages at critical time points

The data identified four critical time points at which key messages needed to be delivered: (1) before birth – in the existing counselling, very little discussion on exclusive breastfeeding took place with the mother or other family members before childbirth; (2) immediately after birth when the incapacitated mother was often not in control, and other key family members took decisions on her behalf; (3) the period after the first month when family support through the traditional Chilla diminished; and (4) three to four months (traditionally the time to add semi‐solids because the baby perceived to need more energy).

Reinforce key messages and behaviours

The data identified some key behaviours that were not being impacted by routine counselling. These included, for example, the addition of traditional supplements to the infant's diet, inappropriate weaning and erroneous perceptions of insufficiency or quality of breast milk. Current counselling techniques were too didactic and gave general advice rather than addressing these specific issues. The CBT technique of guided discovery – gently challenging specific beliefs and replacing these with alternatives, backed up by culturally and scientifically valid arguments supporting the alternative explanations, was agreed by the stakeholders to be a useful method to challenge such beliefs without antagonising family members.

The technique of guided discovery was simplified for use by LHWs and involved a three‐step approach we had used successfully in our previous research. The first step helped the LHW to work with the families, using a set of pre‐prepared illustrations and vignettes, to identify unhelpful beliefs and practices related to exclusive breastfeeding. Identifying such unhelpful beliefs and practices enabled mothers and families to examine these more carefully. The second step was learning to replace such beliefs and practices with equally powerful alternative ones, again pre‐prepared through the formative research. In the third step, the LHWs suggested activities and ‘homework’ to help mothers to practise optimal breastfeeding. Mothers would therefore not become passive recipients of advice but actively participate in seeking and practising breastfeeding and other supporting activities suggested by the LHW. Through their monthly supervision, the LHWs would be able to continuously discuss and modify the alternative explanations, adapting those that worked well and discarding those that did not.

Involve other key household members

It was clear from the data that individual counselling was insufficient to change practice because some key family members, especially the more experienced and influential women in the household were involved in the decision making and actively reinforcing traditional practices. The counselling process needed to involve them, in addition to the mother. Techniques that we had used successfully in our previous work were incorporated into the current counselling. These included engaging and preparing key family members before initiating the counselling; valuing the knowledge and experience of the older women; making the newborn's optimal development as the common agenda and making family members feel a part of the team to achieve it. Shared goals would also help remove any potential misgivings of family members about the programme, e.g. ‘they are brain washing our womenfolk away from our traditional way of life’.

The data showed that many mothers needed practical support during the exclusive breastfeeding period, so that they found the time and energy for this crucial activity for the child's optimal development. CBT techniques of problem solving, which allowed the LHW to work with the mother and family members to deal with such practical issues such as organising the mother's activity so that she had time to rest, nurse and even play with the infant, were incorporated into the counselling process.

Support ‘psychologically distressed’ mothers

Our previous epidemiological studies and the current data indicated that many women are psychologically distressed and this has a bearing on their abilities to breastfeed. An overly critical approach would more likely damage the already poor confidence in their abilities to care for the infants. The new counselling process required that the LHWs identified such women and developed a safe and trusting relationship with them. LHWs should be trained in the skills of active listening so that such women felt understood and listened to. Praise and encouragement for even the small steps undertaken successfully would help reinforce positive changes in behaviour.

Use imagery to facilitate work with non‐literate mothers

Using culturally appropriate illustrations and vignettes, the intervention could use imagery techniques to facilitate work with less‐literate mothers and families. Using characters depicting mothers, infants and other family members, the illustrations could help the LHW talk about existing practices and their possible consequences in a non‐confrontational fashion. Alternate sets of illustrations would allow them to present new ideas in a culturally appropriate manner, avoiding conflict with women and their families.

Integrate with other health education

Breastfeeding counselling should be delivered in a holistic manner, well integrated with other key health messages, which have a bearing on maternal and child health. Thus, maternal nutrition, birth preparedness, appropriate post‐partum care and growth monitoring are all activities that would have a bearing on breastfeeding practice and vice versa. One health message cannot be emphasised at the expense of another.

The resultant approach is summarised in Table 1. The training module for this approach consisted of a manual for health workers, a manual for trainers of the LHWP and a set of counselling cards to be used by the worker while having discussion with the mother and family. These tools can be viewed on the website http://www.hdrf.edu.pk

Table 1.

Key components of the psycho‐educational approach

| Item | Key features |

|---|---|

| Theoretical framework | Uses techniques of cognitive behaviour therapy including active listening, guided discovery, problem solving and imagery. Involves family members and is participatory. |

| Delivery agent | Community‐based health workers called Lady Health Workers (LHWs) |

| Sessions | Seven sessions delivered at home to mother and family; first in the third trimester of pregnancy; second immediately after birth; five monthly sessions thereafter. Sessions integrated into the routine visits of the LHWs. |

| Tools | Training manual for health workers with step‐wise instructions for every visit; pictorial counseling cards to use during home visits; TOT manual for trainers. |

| Training | Two‐day training workshop including lectures, discussions and role plays followed by half‐day refresher training. |

| Supervision | Monthly half‐day sessions in groups of 10–15 conducted by LHWP's own supervisors trained by the intervention team. |

| Other features | Integrated with routine monthly training and supervision programme; compatible with existing district‐level administrative structures. |

LWH, Lady Health Workers; LHWP, Lady Health Workers' Programme; TOT, training of trainers.

Phase 3: implementation and feedback

In a 2‐day training workshop, the research team trained the trainers of the LHWP. After a gap of 2 weeks, these trainers imparted the 2‐day training to the LHWs. A participatory approach was adopted, with PowerPoint presentations, lecture notes and role plays to complement the training. LHWs were provided the opportunity to practice simplified principles of CBT during the role plays. Following training, the LHWs implemented the counselling in their routine practice. Feedback obtained from the LHWs and their trainers/supervisors following implementation is reported below.

Post‐training qualitative feedback

New skills learned

The LHWs felt that the training improved their counselling skills. The intervention gave them a framework to engage families, and to modify their clients' beliefs and practices in a structured, non‐confrontational and interesting way.

We never knew it would be so useful to engage the whole family before the baby is born. We can prime them of the importance of breastfeeding so they are better prepared when the baby arrives. Previously, we talked to them about breastfeeding after the baby's birth. (A trainer from Garlaat)

Communication is about being confident, and new skills like active listening, better ability to identify barriers and respond to questions, and effective use of pictures has enhanced the LHW's confidence. (A trainer from Garlaat)

Although their routine training equipped them with the facts about optimal breastfeeding practices, they shared the culture and beliefs of their clients, and therefore, frequently found it difficult to provide a rationale for the messages. The cognitive techniques helped the LHWs explain their messages in culturally appropriate ways.

Even we believed that it was common for the mother to produce insufficient milk for the baby's need. Only after this training, our misperception was corrected. (An LHW from Bheerkund)

We have been preaching that infant should be exclusively breastfed for six months instead of four but when family members asked us why, we did not have a good answer. (An LHW from Sandaysar)

This approach delivers key messages at key time points. This makes much more sense to the mothers and families, as it addresses concerns they have at that particular time‐point. (A trainer from Sandaysar)

Feasibility of delivery

The LHWs and their trainers reported that the new intervention was accepted by the mothers and their families. The new approach was not perceived to be alien or threatening. The LHWs felt that they were giving the same messages they did before, but with more confidence and conviction. The tools such as the counselling cards and the illustrations were found to be very helpful by the mothers.

They (LHWs) already knew these messages and had been giving these to the mothers but the previous method presented us with more problems because we would give messages and sometimes these clashed with the traditional ways of thinking and we would get into arguments with the families. Now we can explain things in a much better way using the 3 steps we have learned, and we find that the families listen to us. (A supervisor from Kathai)

Previously we used to give a lecture about the benefits of breastfeeding. Many women did not remember what we had told them. Now in each visit we use the counselling cards which have a specific message relevant to that visit and the women are much more interested. (An LHW from Bheerkund)

Effect on other areas of work

The LHWs felt that they were initially spending more time with all the families and the mothers, but as they became more experienced, they did not have to do so with all the families. Only some families required a more detailed discussion, and similarly, only some women needed extra support. The LHWs and their supervisors all strongly felt that they derived more satisfaction from their work as they engaged more effectively with the families. Many LHWs reported that the new skills they learned helped them in other aspects of their work, e.g. immunisation and uptake of contraception.

We feel that the techniques are interesting and can help in communicating about other health issues also. (An LHWs from Bheerkund)

Potential for scaling up

The LHWs, their supervisors and managers all agreed that the intervention could be scaled up to cover the entire national programme.

This is not a new task for LHWs. They have been doing this before, so they will not be over‐burdened by the new technique. (A trainer from Garlaat)

This intervention can become part of the National Programme and will make the LHWs more effective. (A trainer from Kathai)

The participants felt that to make it more effective, other staff of the primary care programme – the physicians and health visitors – also needed to support the programme and give the same messages. They suggested that the intervention ought to include a community awareness component, which could be disseminated through the print and electronic media. Private practitioners such as private general practitioners and traditional birth attendants also needed to be educated. Such an integrated approach would create the greatest impact, rather than the LHW working in isolation.

We think LHW will be able to integrate this intervention into her everyday practice; however, the success of the programme will also depend on educating the family and community in general; involving our medical officers and health visitors, and the health committees (consisting of influential villagers) to support the work. (A trainer from Kathai)

Post‐implementation quantitative feedback

The post‐implementation quantitative feedback from the LHWs is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lady Health Workers (LHWs) feedback on intervention after implementation (n = 40)

| Statement | Response (n/%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely true | Somewhat true | Not sure | Not true | Definitely not true | |

| The new intervention is relevant to my day‐to‐day work | 27 (67) | 9 (23) | 4 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| The new intervention is an extra burden in my day‐to‐day work | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (36) | 25 (64) |

| I am able to understand the techniques explained in my training | 29 (73) | 11 (27) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I am able to use these techniques in my day‐to‐day work with mothers | 25 (63) | 11 (27) | 4 (10) | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

This formative research shows that the incorporation of CBT techniques into the routine counselling for exclusive breastfeeding in a low‐literacy traditional population in a backward district of Pakistan is useful, feasible and culturally acceptable. It is especially relevant in the context of resource‐poor countries where maternal education levels are low and traditional practices deeply embedded. The community‐based approach is also relevant in settings where the majority of childbirth takes place at home and institutional approaches such as baby‐friendly hospitals cannot help in early initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Based on psychotherapeutic principles, it enables health worker to deliver counselling in an individualised way, addressing specific cultural barriers. The approach is based on current knowledge on breastfeeding promotion along with data derived from qualitative discussions with mothers, health workers and trainers of these workers, and advice of the programme managers.

While the cognitive behaviour techniques used in our intervention are derived from the psychotherapy field, they have features in common with other behaviour‐change techniques (BCTs). For example, Abraham & Michie (2008) have developed a taxonomy of 26 BCTs derived from a number of theories such as information‐motivation‐behavioural skills model, theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behaviour, social‐cognitive theory, control theory and operant conditioning theory (Abraham & Michie 2008). Techniques such as those focusing on behaviour‐health and behaviour‐consequences links, barrier identification, setting of graded tasks and provision of contingent rewards overlap with our intervention. However, the psychotherapeutic approach places the mother at the centre of the intervention, recognising that her well‐being is an essential prerequisite to intervention delivery. We feel that addressing these needs creates the necessary emotional and cognitive space in which behaviour‐change issues can be introduced. This approach is especially relevant in underdeveloped areas where rates of psychosocial distress in women of childbearing age are very high (Rahman et al. 2008b). Further process evaluation during the trial phase will allow us to tease out individual techniques that have the greatest impact on the outcome.

This preliminary study indicates that the approach might have many advantages. First, as suggested above, it is maternal focused. Second, it fills the knowledge gaps on exclusive breastfeeding among the target audience. Third, it uses strategic time points and demonstrable changes in child's health (gain in weight) and development (achievement of milestones) as an incentive for the mother to continue exclusive breastfeeding. Fourth, it is integrated and holistic, enabling the health worker to identify early those infants who do not achieve normal growth despite exclusive breastfeeding. The worker is taught how to explain this situation to the family and refer the infant to a health facility as recommended. Fifth, it enables the worker to listen first, rather than tell, and then analyse the family's beliefs and practices, and gently challenges these with alternative concepts, supported by culturally appropriate and logical explanations. Finally, in addition to mother, the technique also includes other key family members to support the mother and her infant in this critical period.

The evidence for interventions that increase the prevalence of breastfeeding in high‐income settings has been summarised in two Cochrane reviews (Dyson et al. 2005). These show that one to one professional or lay support increases the duration of any breastfeeding up to 6 months, with a greater effect for exclusive breastfeeding. However, studies from low‐income countries are rare. A recent systematic review of community‐based interventions that promote exclusive breastfeeding in low‐income settings identified four randomised trials, which measured the outcome at 4–6 months (Hall 2011). Bashour et al. (2008) evaluated the impact of registered midwives with special training making home visits to support women in the post‐natal period rural and urban areas of Syria. The intervention consisted of one to four counselling sessions delivered at home. Bhandari et al. (2003) studied rural communities in India and assessed the effect of a range of lay and professional health workers incorporating information about breastfeeding into routine community‐based services as well as providing community education sessions. The interventions were extensive and involved over 20 face‐to‐face contacts. Bhutta et al. (2008) conducted a pilot randomised controlled trial in rural southern Pakistan. LHWs and traditional birth attendants were given extra training on perinatal care, and provided seven home visits and quarterly community education sessions to women under their care. Lastly, Haider et al. (2000) trained peer counsellors in Dhaka, Bangladesh to support women to breastfeed exclusively through a series of 15 antenatal and post‐natal visits. All the interventions showed a significant improvement in the rate of exclusive breastfeeding with a pooled odds ratio of 5.90 (95% confidence interval 1.81–18.6) on random effects meta‐analysis. The Pakistani study was of special relevance to our work because it provided extra training to LHWs to deliver an enhanced form of counselling compared to the routine counselling. The trial, conducted on over 750 mothers, showed that the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the control arm was 31%, compared to 48% in the intervention arm. While significant, it indicates that even after receiving the enhanced intervention, over half the women were still not exclusively breastfeeding. This indicates that the additional measures, such as the ones we propose in our intervention, may be useful to target women who are resistant to routine counselling. We deliberately conducted our study in a very conservative backward district in Northern Pakistan where the rates of exclusive breastfeeding are among the lowest in the country.

Notwithstanding the challenges of conducting research in such settings, our intervention is in line with recommendations for developing new interventions, arising from the existing breastfeeding literature. It has been recommended that interventions should be culturally appropriate, capable of addressing socio‐economic context and tailored to individual needs (Dyson et al. 2005). New approaches that could focus on the initial days after birth address complex psychological and health organisation factors, and address health inequalities have been emphasised (Hoddinott et al. 2008). Breastfeeding self‐efficacy – the mother's confidence in her ability to breastfeed her infant (Dennis & Faux 1999) – is an important predictor of breastfeeding duration and pattern (Blyth et al. 2002), and the importance of approaches that could improve this efficacy have been highlighted (Noel‐Weiss et al. 2006). Formative research to gain an in‐depth understanding of communities has been called an essential step prior to investment in scaling up large programmes (Bhandari et al. 2008).

Our CBT‐based communication developed in partnership with the implementing programme ensures participation, engages all stakeholders of infant's health into a meaningful dialogue to explore options and identify the best course. In addition, it improves communication capacity of health workers, especially enhancing their capability to identify and address barriers, provides them with appropriate job‐aides, and emphasises on using role plays during training; something that has been highlighted in the past research (Haq et al. 2008; Haq & Hafeez 2009).

The approach is integrated with the pre‐existing policy of breastfeeding promotion and employs existing health workers for its delivery. It does not require addition of expensive new cadre of health worker or separate communication channels. To facilitate the incorporation of psycho‐educational approach to the existing curriculum of the LHW, the programme's training unit was involved at every step of development of this approach. The incorporation of updated knowledge into curricula of nurses has been described as key to successful promotion of breastfeeding (Peterson et al. 2002; Spatz and Pugh 2007). All efforts were made to keep the costs low so that integration of this new psycho‐educational approach to the existing curriculum of LHWs remained feasible. The trainings for health workers were provided by their own facility‐level trainers. This fostering of institutional changes by conducting research in partnership with the public sector so that efficacious interventions are readily integrated and become sustainable has been advocated by experts (Peterson et al. 2002).

Some limitations of this formative research must be kept in mind. The sample of LHWs, mothers and staff of LHWP was purposive and their responses cannot be generalised across the country. Cultural beliefs and practices may differ from region to region and the study may need to be repeated in other settings. However, the underlying principles identified would remain the same. Another possible limitation is that the research team had a bias towards the usefulness of CBT techniques as some of them had been involved in earlier trials that used CBT‐based counselling to address perinatal depression (Rahman et al. 2008). The enthusiasm of the researchers for their intervention may have infected the LHWs and their trainers, leading to a ‘Hawthorne effect’ (positive results reported as a result of the mere presence of an enthusiastic researcher). More systematic and longer term evaluation will be required to assess the effectiveness and sustainability of the approach, and to determine which techniques were most effective in creating change. A cluster‐randomised trial currently being undertaken in Mansehra district that will provide further evidence about the effectiveness of this approach.

Source of funding

The study was supported by PRIDE (Primary Health Care Revitalisation, Integration and Decentralisation in Earthquake affected Areas); a project funded by US Agency for International Development.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

AR, ZH, SS and AH conceptualised and designed this study. IA and MA carried out the data collection. ZH and SS conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. ZH developed the first draft. AR wrote the final draft with contributions from all the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all mother–infant pairs, their families, the Lady Health Workers, their supervisors and trainers from the National Programme who participated in the study and helped us to develop the intervention. We thank the National Programme for Family Planning and Primary Health Care for being a facilitating partner and Human Development Research Foundation, Islamabad, for implementing the research. This publication was made possible through the support provided by the Office of Reconstruction Bureau for Pakistan, US Agency for International Development. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the US Agency for International Development.

References

- Abraham C. & Michie S. (2008) A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology 27, 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agha A., White F., Younus M., Kadir M.M., Ali S. & Fatmi Z. (2007) Eight key household practices of Integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) amongst mothers of children 6 to 59 months in Gambat, Sindh, Pakistan. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 57, 288–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2011) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk: section on breastfeeding. American Academy of Pediatrics, Pediatrics. 115, 496–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bashour H.N., Kharouf M.H., Abdulsalam A.A., El Asmar K., Tabbaa M.A. & Cheika S.A. (2008) Effect of postnatal home visits on maternal/infant outcomes in Syria: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nursing 25, 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari N., Bahl R., Mazumbar S. et al (2003) Effect of community‐based promotion of exclusive breastfeeding on diarrhoeal illness and growth: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 361, 1418–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari N., Kabir A.K. & Salam M.A. (2008) Mainstreaming nutrition into maternal and child health programmes: scaling up of exclusive breastfeeding. Maternal and Child Nutrition 4, 5–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Z.A., Memon Z.A., Soofi S., Salat M.S., Cousens S. & Martines J. (2008) Implementing community‐based perinatal care: results from a pilot study in rural Pakistan. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86, 452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth R., Creedy D., Moyle W., Pratt J. & Devries S. (2002) Effect of maternal confidence on breastfeeding duration: an application of breastfeeding self‐efficacy theory. Birth 29, 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K., Arno P.S., Memmott M.M., Freeman K., Gold M. & Mckee D. (2002) Breastfeeding promotion interventions: good public health and economic sense. Journal of Perinatology 2002, 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C. & Faux S. (1999) Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale. Research in Nursing and Health 1999, 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L., McCormick F. & Renfrew M.J. (2005) Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD001688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank L., Meara S.O., Renfrew M.J., Woolridge M., Sowden A.J. & Lister‐Sharp D. (2000) A systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to promote the initiation of breastfeeding. Health Technology Assessment 4, 48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsbers B., Mesters I., Knottnerus A.J. & Schayck C. (2008) Factors associated with the duration of exclusive breast‐feeding in asthmatic families. Health Education Research 23, 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golay A., Buclin S., Ybarra J., Toti F., Pichard C., Picco N. et al (2004) New interdisciplinary cognitive‐behavioural‐nutritional approach to obesity treatment: a 5‐year follow‐up study. Eating and Weight Disorders 9, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Pakistan (1998) District Census Report, Mansehra. Government of Pakistan: Islamabad. [Google Scholar]

- Haider R., Ashworth A., Kabir I. & Huttly S.R. (2000) Effect of community‐based peer counsellors on exclusive breastfeeding practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 356, 1643–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. (2011) Effective community‐based interventions to improve exclusive breast feeding at four to six months in low‐ and low‐middle‐income countries: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Midwifery 4, 297–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq Z. & Hafeez A. (2009) Knowledge and communication needs assessment of community health workers in a developing country: a qualitative study. Human Resources for Health 7, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq Z., Iqbal Z. & Rahman A. (2008) Job stress among community health workers: a multi‐method study from Pakistan. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P., Tappin D. & Wright C. (2008) Breast feeding. British Medical Journal 336, 881–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore S.M., Kumar P. & Aggarwal K.A. (2007) Breastfeeding knowledge and practices amongst mothers in a rural population of north India: a community‐based study. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 55, 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S., Chalmers B., Hodnett E.D., Sevkovskaya Z., Dzikovich I., Shapiro S. et al (2001) Promotion of breastfeeding intervention trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. The Journal of the American Medical Association 2001, 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow A.L., Reves R.R., West M.S., Guerrero M.L., Ruiz‐Palacios G.M. & Pickering L.K. (1992) Protection against infection with Giardia lamlia by breastfeeding in a cohort of Mexican infants. The Journal of Pediatrics 121, 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow A.L., Guerrero M.L., Shults J., Calva J.J., Lutter C., Bravo J. et al (1999) Efficacy of home‐based peer counselling to promote exclusive breastfeeding: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 353, 1226–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Studies (2007) Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006–07, Preliminary Report, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad.

- Newburgh D.S., Peterson J.A., Ruiz‐Palacios G.M., Matson D.O., Morrow A.L., Shults J. et al (1998) Role of human‐milk lactadherin in protection against symptomatic rota virus infection. Lancet 351, 1160–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel‐Weiss J., Rupp A., Cragg B., Bassett V. & Woodend A. (2006) Randomized controlled trial to determine the effects of prenatal breastfeeding workshop on maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy and breastfeeding duration. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 35, 616–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Policy Management (2009). Lady Health Worker Programme: Third Party Evaluation of Performance. 1‐6‐2011.

- Peterson K.E., Sorensen G., Pearson M., Hebert J.R., Gottlieb B.R. & McCormick M.C. (2002) Design of an intervention addressing multiple levels of influence on dietary and activity patterns of low‐income, postpartum women. Health Education Research 17, 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Zieblan S. & Mays N. (2000) Qualitative research in health care: analyzing qualitative data. British Medical Journal 320, 114–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin B.M., Adair L., Atkin J.S., Black R., Briscoe J. & Fleiger W. (1986) Breastfeeding and diarrhoeal morbidity. Pediatrics 86, 874–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A. (2007) Challenges and opportunities in developing a psychological intervention for perinatal depression in rural Pakistan – a multi‐method study. Archives of Women's Mental Health 10, 211–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A., Malik A., Sikander S., Roberts C. & Creed F. (2008a) Cognitive behaviour therapy‐based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 372, 902–909. Available from: PM:18790313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A., Patel V., Maselko J. & Kirkwood B. (2008b) The neglected ‘m’ in MCH programmes – why mental health of mothers is important for child nutrition. Tropical Medicine and International Health 13, 579–583. Available from: PM:18318697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz D. & Pugh L. (2007) The integration of the use of human milk and breastfeeding in baccalaureate nursing curricula. Nursing Outlook 55, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes C.M. & Marks D.F. (2001) Effectiveness of a cognitive behavior therapy self‐help programme for smokers in London, UK. Health Promotion International 16, 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor‐Powell E. & Renner M. (2011) Analyzing Qualitative Data. University of Wisconsin – Extension Program Development & Evaluation: Madison, WI. Available at: http://learningstore.uwex.edu/assets/pdfs/G3658-12.pdf (last accessed: 31 August 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Victora C.G., Vaughan J.P., Lombardi C., Fuchs S., Giante L., Smith P.G. et al (1987) Evidence for protection by breastfeeding against infant deaths from infectious diseases in Brazil. Lancet ii, 319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2002a) The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding: A Systemic Review. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2002b) Nutrient Adequacy of Exclusive Breastfeeding for the Term Infant during the First Six Months of Life. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2011) World Health Assembly. 54.2 and A54/INF.DOC.4.