Abstract

Acculturating to a host country has a negative impact on immigrant women's breastfeeding practices, particularly when coming from countries where breastfeeding rates are higher than Western countries. Whether this is true of those immigrating to the UK remains to be investigated. The study aimed to explore whether acculturating to the UK had detrimental effects on breastfeeding practices of South Asian women, and to provide explanations as to how acculturation may have exerted its influence.

Twenty South Asian women completed semi‐structured interviews exploring infant feeding experiences. Data were thematically analysed. A bidimensional measure assessed women's acculturation status.

Women displaying low acculturation levels were aware of living in a formula‐feeding culture but this had little influence on breastfeeding intentions/behaviours; drawing upon South Asian cultural teachings of the psychological benefits of breast milk. These women opted to formula‐feed in response to their child's perceived demands or in a bid to resolve conflict; either when receiving information about the best feeding method or between their roles as a mother and daughter‐in‐law. Highly acculturated women also experienced such conflict; their awareness of the formula‐feeding culture governed feeding choice.

The findings provide a picture of how acculturation may affect South Asian women's breastfeeding intentions and behaviours; encouraging health service providers to meet the varying needs of an acculturating population. If breastfeeding is to be encouraged, it is necessary to understand factors influencing feeding choice; with particular attention to the acculturation pathways that may govern such decisions. This paper highlights ways to tailor information for South Asian women depending on levels of acculturation.

Keywords: infant feeding, acculturation, South Asian, breastfeeding, minority ethnic groups

Introduction

The Department of Health policy in England and Wales has been supportive of breastfeeding as the best way of ensuring a healthy start for infants for some years, and is one of the key strategies in tackling inequalities in health (Department of Health 1998, 1999, 2004). The UK has one of the lowest rates of breastfeeding worldwide, especially among families from disadvantaged groups (Dyson et al. 2005). The National Health Services (NHS) Priorities and Planning Framework (2003–2006) has set targets of increasing breastfeeding initiation rates annually by two percentage points particularly among those least likely to breastfeed (Department of Health 2003). This target has been included into local delivery plans to support the public service agreement target on infant mortality for the planning period to 2008 (Jackson 2008).

In spite of policy support and targets, rates of breastfeeding remain low in the UK. For example, in 2005 only 78% of women in the UK initiated breastfeeding (Bolling et al. 2005), with the lowest initiation rates concentrated among South Asian women (Meddings & Porter 2007). This latter point is based upon an unpublished breastfeeding audit conducted in Northern England (Hartley 2003, unpublished audit in Meddings & Porter 2007). The audit revealed that breastfeeding initiation rates were very low among Pakistan women (43%). By the time the women were discharged from hospital, rates had fallen to 35%.

Studies in the United States have gone beyond studying ethnicity as an independent variable and have examined factors such as the women's country of birth in relation to infant feeding choices. There has been recognition that although immigrant women come from countries where breastfeeding rates are high (Rassin et al. 1993), their rates may decrease dramatically upon arrival to a new host country (Bonuck et al. 2005). Evidence suggests that an additional year spent in the United States was associated with a 4% decrease in the odds of breastfeeding (Gibson‐Davis & Brooks‐Gunn 2006). The authors do not provide details of whether this decrease is related to the initiation or duration of breastfeeding. A previous study found an increased likelihood to formula feed in women who had recently immigrated to the United States from Mexico; while those who were less acculturated to the United States were more likely to opt to breastfeed (Scrimshaw et al. 1987). To understand the influence of country of birth on immigrant women's breastfeeding behaviours, it is important to acknowledge that infant feeding practices are embedded in the context of ethnic and cultural beliefs. Upon immigration, it is this context that changes for those who immigrate to a new geographic region and culture where infant feeding practices may be very different (Kannan et al. 1999). Consequently, an individual's beliefs, values and way of life may undergo modification in a bid to adapt to their new environment (Rossiter 1992). The impact of such processes on breastfeeding behaviours may be accounted for by the concept of acculturation (Riordin & Gill‐Hopple 2001);

The extent to which people from one culture adapt to or accommodate their behaviour and thoughts and perceptions of the norm of a second culture (Rassin et al. 1993; p. 29)

The process of acculturating to a new host country has a negative impact on Hispanic women (Gibson et al. 2005), Vietnamese women (Riordin & Gill‐Hopple 2001), Pakistani, Indian and Bangladeshi women (Bowes & Domokos 1998) and Mexican women's breastfeeding practices (Gibson‐Davis & Brooks‐Gunn 2006). The findings mentioned focus upon specific sub‐groups immigrating to the United States from countries with high breastfeeding rates. Whether immigrating incurs detrimental effects on breastfeeding practices in those coming to England from countries with high breastfeeding rates remains to be explored.

The UK Infant Feeding Survey is conducted every 5 years (Bolling et al. 2005). It provides estimates of the incidence, prevalence and duration of breastfeeding and other feeding practices adopted by mothers in the first 8–10 months after their baby is born. However, because this national survey does not differentiate between women born in the UK and those born outside the UK, it may mask the potential detrimental role of acculturation on breastfeeding rates of these women. Data from the sample in England suggest that although South Asian women have a higher incidence of breastfeeding, they exhibit lower rates of breastfeeding at 4 weeks compared with White mothers (Bolling et al. 2005). Given that South Asian communities have increasing rates of immigration to the UK (White 2002) and display the lowest rates of breastfeeding duration, provides a strong impetus to explore the reasons that variation within these ethnic groups occurs. One aspect may be recency of immigration, a factor implied in studies of immigration to the United States. Women who have recently immigrated may bring with them culturally informed beliefs about what facilitates a good pregnancy and its outcome, but when encountering people unfamiliar with their customs they may be tempted to relinquish their traditional ways (Choudhry 1995). Rates of breastfeeding in the UK are lowest among those from socially deprived areas (Bolling et al. 2005), this is in contrast to South Asia where breastfeeding rates are highest among those from lower social classes (Khan 1991). Thus, South Asian women residing or immigrating to the UK may misperceive breastfeeding to be a symbol of social class deprivation in Western societies (Kannan et al. 1999), opting to formula‐feed instead (Bowes & Domokos 1998).

Previous research provides valuable information as to the kind of effect acculturation has on breastfeeding practices. However, much of the research has been exploratory without having a strong theoretical grounding (Abraido‐Lanza et al. 2006). As a consequence, the findings provide descriptions of the relationship between acculturation and breastfeeding intentions and behaviours rather than explanations as to how or why this relationship occurs. A woman's decision to breast‐ or formula‐feed may be open to social and cultural influences (Swanson & Power 2005); however, the influence of cultural factors has received little attention in relations to ethnicity and breastfeeding (Griffith et al. 2005). The social norm construct of the Theory of Planned Behaviour has been found to play an important role in the choice of baby feeding method at birth (Swanson & Power 2005) and may aid understanding as to how the process of acculturation exerts an influence on attitudes to breastfeeding.

Traditionally, research has explored acculturation status in those that have immigrated to a new country (Rossiter 1992; Gibson et al. 2005). However, acculturation scales may also be used in regions where a number of different cultures come into contact regardless of the individual's immigration status (Rassin et al. 1993; Abraido‐Lanza et al. 2006). Therefore, this opened the possibility of recruiting women both born in the UK as well as those that had immigrated to the UK from South Asia.

The current study aims to fill a significant gap in the UK literature by providing an exploration of how the experience of acculturating to England may affect beliefs about breastfeeding practices in England, their own attitudes to breastfeeding and to breastfeeding behaviours in a specific sub‐sample of South Asian women residing in parts of Birmingham in England. The exploratory nature of the study is such that the aim is not to generalize the findings, but to raise and explore some of the key issues related to acculturation that may have a bearing upon the infant feeding experiences of South Asian women.

Key messages

-

•

Acculturating to a country such as the UK may have detrimental effects on South Asian women's breastfeeding belief and breastfeeding behaviours.

-

•

Exclusive focus on ethnicity as a means of targeting public health interventions fails to take account of religious and cultural differences.

-

•

Women displaying low levels of acculturation require strong encouragement that their feeding practices (if they are breastfeeding or intending to breastfeed) are the most appropriate. While women displaying high levels of acculturation or displaying biculturalism need to be aware that ‘West is not always best’.

Methods

Design

A descriptive qualitative study (using a combination of structured items assessing acculturation status and open‐ended questions forming a semi‐structured interview) was selected. This method was chosen because it allowed an effective exploration of the attitudes and beliefs of the women with regard to their intentions to breastfeed and/or their breastfeeding behaviours (Mulholland and Vanherson 2007).

Procedure

Participants and recruitment

Ethical approval was granted by Coventry University Ethics Committee. Prior to conducting the study, the interview schedule and the structured items assessing acculturation status were piloted with five South Asian mothers of whom three required the questions to be translated into Urdu. This confirmed the tool's suitability in terms of its structure, content and language for the target population.

An opportunistic sample of 20 South Asian women attending one of four Children's Centres across Birmingham was recruited. Inclusion criteria for women was that they were of South Asian origin, users of the Children Centres, were of childbearing age and were either expecting a baby or already with a child under the age of five. The schedule was devised in English. Women who could not understand English but who could communicate in either Urdu, Hindi or Punjabi were also invited to take part in the study. The researcher (KC) was able to deliver the questions in all three languages. Unfortunately, Bangladeshi women unable to speak English had to be excluded from the sample because of the researcher's inability to speak or understand Bengali. Women with major mental illness or cognitive difficulties were also excluded from the sample.

Data collection methods

Details of the Semi‐Structured Interview Schedule; experiences of infant feeding experiences

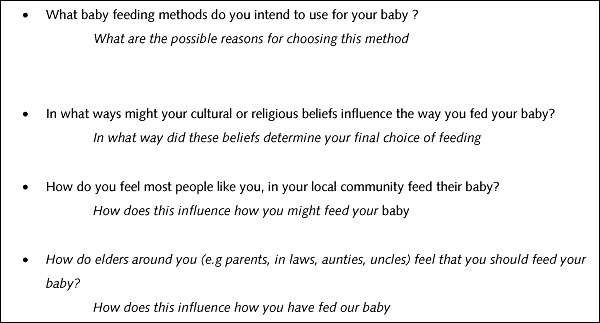

Past research has often quantified acculturation (e.g. Gibson et al. 2005); however, there is a need to assess the extent to which acculturation scores reflect subjective changes (Matsudaira 2006), particularly as acculturation consists of largely qualitative changes (Berry 1997). Semi‐structured interviews can provide detailed descriptions of the acculturation process and elicit ways in which participants perceive various issues and why they respond in the manner that they do (Matsudaira 2006). For this reason, women were asked open‐ended questions to gather information on their experiences of infant feeding and the social and cultural factors that may have influenced their feeding decision (See Box 1).

Figure Box 1. .

Open ended questions asked of the women in the sample (questions were worded accordingly depending on whether women had had their baby, or were still pregnant with their baby).

Research has shown there is potential for researcher bias in ‘loading questions towards the evaluation of the benefits of breastfeeding; failing to take into account the possible negatives in breastfeeding and positives in formula feeding’ (Swanson & Power 2005: p. 273). In recognition of this, the schedule asked women about their ‘chosen method of feeding’ rather than specifically asking about breast or bottle feeding.

Details of the structured items of the schedule – personal descriptive information and acculturation status of women

Structured items were used for personal descriptive information (such as age, country of birth, ethnicity, religious background and acculturation status). Previous research has often employed one‐dimensional items to assess acculturation levels such as generational status of both the individuals and their family members and single language preference items (Carvajal et al. 2002). However, this provides a fragmented picture of the acculturation experience (Cabassa 2004). To fully describe the acculturation process, research should consider multiple facets such as behavioural and subjective elements of culture. In doing so, it allows independent orientation to both original and new cultures to be assessed (Cuellar et al. 1995). Snauwaert et al. (2003) suggest that acculturation can be assessed with simple and straightforward measurement of two acculturation issues. The primary factors thought to represent acculturation are language use and exposure and ethnic interaction (Cuellar et al. 1995). Although acculturation has an impact on all levels of functioning such as behavioural, cognitive and affective factors, previous research has often used behavioural indicators such as language use and ethnic interaction as indices of acculturation and its relation to breastfeeding behaviours and beliefs (for example, Gibson et al. 2005). The current study, therefore, focuses on the two behavioural factors of language use and ethnic interaction as a means to assess acculturation in this sample of women. The bidimensional measure contained eight language use items; four related to the Anglo domain (items included: How often do you . . . . ‘Speak English’, ‘Speak English with your friends’, ‘Watch television programs in English’ and ‘Listen to music or the radio in English’) and four related to the South Asian domain (items included: How often do you . . . ‘Speak a language different than English’, Speak a language different than English with friends', ‘Watch television programs in a language different than English’, ‘Listen to music or the radio in a language different than English’).

Six items assessed ethnic interaction; three related to the Anglo domain (items included: How often do you . . . ‘talk with friends who are a different group than you’, ‘spend time with people who are a different group than you’ and ‘associate with people who are a different group than you’) and three related to the South Asian domain (items included: How often do you . . . ‘talk with friends who are the same group (or groups) as you’, ‘spend time with people who are the same group as you’ and ‘associate with people who are the same group as you’).

The bidimensional nature of the measure allowed the possibility for the women to keep characteristics of both their new culture and their culture of origin (Carvajal et al. 2002). Combining the scores on both domains provided an overall acculturation score for the women. Content validity of the measure was assessed by the researchers (LW and KC) and two health professionals working within the Children's Centres.

Reliability of the acculturation measure

The acculturation scale used in the current study has been adapted from the work of Carvajal et al. (2002) and has been used widely with various populations residing in the United States. Carvajal et al.'s (2002) acculturation scale has been shown to have high internal consistency for both language and ethnic interaction‐related items. It has been reported to have and has been reported to be reliable and valid with various populations (Carvajal et al. 2002).

Scoring the acculturation scale

Questions assessing the levels of acculturation (e.g. ‘How often do you speak English?’) were rated on a four‐point scale ‘Always, Often, Sometimes or Never’. Each participant has two scores one for the South Asian domain and one for the Anglo domain. Acculturation levels were derived by averaging the scores women gave to the seven items for both domains (Anglo domain and South Asian domain). These two scores are taken to be an indication of their orientation towards the two domains; one score for the South Asian domain and one for the Anglo domain (Christenson 2006). Levels of acculturation can be determined by using a cut‐off point of 2.5 to indicate high or low levels of adherence to each domain (Marin & Gamba 1996), with scores of 2.5 in both domains indicating biculturalism (Marin & Gamba 1996). Table 1 provides a description of what scores derived from the acculturation scale indicate (Carvajal et al. 2002).

Table 1.

Method for assessing levels of acculturation among the group of South Asian women using a bidimensional measure

| Score on acculturation measure | Interpretation of acculturation score |

|---|---|

| Above 2.5 on Anglo domain and lower than 2.5 on South Asian domain | Highly acculturated to the UK |

| Lower than 2.5 on the Anglo domain and above 2.5 on the South Asian domain | Low levels of acculturation to the UK (and high levels of orientation towards culture of origin) |

| Above 2.5 on the Anglo domain and above 2.5 on the South Asian domain | Bicultural (highly acculturated to the UK and high orientation towards culture of origin) |

Analysis of data – exploring women's experiences of feeding

Thematic analysis was used to explore the women's narrative accounts of infant feeding experiences. This form of analysis allowed certain themes to emerge from within the data (Burnard 1991) that could be linked to the South Asian women's breastfeeding attitudes and practices. The methods of analysis were informed by the work of Braun & Clarke (2006). A theme was thought to be important if it captured something important in relation to the overall research aims rather than quantifying its occurrence within the entire data set (Braun & Clarke 2006).

Given that previous findings have suggested that acculturation has an impact on women's choice of infant feeding (Abraido‐Lanza et al. 2006), experiences of infant feeding and beliefs about UK infant feeding practices were explored by differentiating between the three acculturation groups (Low, High and Bicultural).

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 23 South Asian women were invited to take part in the current study, of whom 20 women took part; 11 were born in the UK and nine were born outside the UK. Seven of the women were married to men born in the UK. It was anticipated that the majority of the sample would be immigrants from South Asia; however, one of the workers of the children's centres suggested that they access the services of the Children's Centres less than those born in the UK The sample consisted mainly of women of Pakistani ethnicity (n = 17/20). Although the children centres were situated in areas of Birmingham densely populated with South Asian populations (e.g. Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani), the majority of the sample was Pakistani. This was thought to reflect the balance in the local population served by the Children's Centres. Seventeen of the 20 women were Muslim, while the remainder were followers of Sikhism.

The majority of the women could be classified as either bicultural (n = 7), or as having low levels of acculturation to the UK (n = 9). Four women were highly acculturated to the UK. Table 2 presents detailed information for each participant, including parity, feeding experiences, country of birth and levels of acculturation. In terms of the defining methods of infant feeding, breastfeeding in the current study was used to refer to all babies whose mothers put them to the breast, even if this was for one occasion only (Bolling et al. 2005). Exclusive breastfeeding refers to the proportion of babies who have only ever been given breast milk who have never been fed formula milk, solid foods or any other liquids (Bolling et al. 2005). Formula feeding was defined as providing the infant with prepared/powdered baby milk instead of breast milk.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics of women; parity and feeding experiences

| Parity | Feeding experiences | Acculturation level | UK born or not? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Second child | Exclusively breastfed | Bicultural | UK born |

| Participant 2 | Expecting first child | Intending to breastfeed | Low | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

| Participant 3 | Expecting first baby | Intending to formula feed | Bicultural | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

| Participant 4 | Expecting second baby | Formula fed first child, Intending to formula feed second child | Low | UK born |

| Participant 5 | Recently had second child | Breastfed for 5 months | Low | UK born |

| Participant 6 | Recently had first child | Breastfed for 2 months | Low | UK born |

| Participant 7 | Second baby | Breastfed for 2–3 weeks | Bicultural | UK born |

| Participant 8 | Second baby | Breastfed | Bicultural | UK born |

| Participant 9 | First child | Breastfed for 2 months | Low | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

| Participant 10 | Second child | Breastfed | Bicultural | Non‐ UK |

| Participant 11 | Second child | Breastfed | Bicultural | UK born |

| Participant 12 | Second baby | Formula fed | Low | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

| Participant 13 | Second baby | Breast fed for 2 months | High | UK born |

| Participant 14 | First baby | Breast fed for 4 months | High | UK born |

| Participant 16 | First baby | Breastfed for a month | Bicultural | UK born |

| Participant 17 | First baby | Bottle fed | Low | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

| Participant 18 | First baby | Breast fed for a day | Low | Non‐UK (India) |

| Participant 19 | Second baby | Breastfed | High | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

| Participant 20 | First baby | Breastfed | Low | UK born |

| Participant 21 | First baby | Bottle fed | High | Non‐UK (Pakistan) |

Women's beliefs about UK infant feeding practices and personal attitudes and experiences on infant feeding

Five themes emerged across the three groups of women that were thought to capture the women's experiences of infant feeding in their locality. There was some overlap between the themes that emerged; suggesting some commonalities in their experiences despite their levels of acculturation or orientation towards their culture of origin. Table 3 presents an overview of the themes that emerged and the presence of each theme across the three groups of women.

Table 3.

Themes underlying women's narrative accounts exploring their beliefs about UK infant feeding practices and personal attitudes and experiences on infant feeding

| Theme | Low acculturation group | High acculturation group | Bicultural group |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Maa Kaa Dood’ (The mother's milk) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| The most convenient method for me | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Formula feeding as a way of fulfilling the baby's demands | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Breast isn't always best – women's experience of information and role conflict | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Learning by observation – the formula feeding culture | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

‘ “Maa ka Dood”– the mother's milk’

Although the women experienced times where breastfeeding was said to be inappropriate in their culture (particularly in front of people), the women also experienced cultural teachings about the importance of the ‘mother's milk’ (Maa ka dood). All women regardless of whether they conducted the interview in English or in another language made reference to this South Asian theme, i.e. ‘Maa ka Dood’. This was interesting as the women communicated the theme as if it had a well‐known, universal meaning, that everyone in the South Asian culture is aware of. The theme was used to describe the psychological benefits (rather than the physical benefits) of the mother's milk;

Culturally it's a way of having a good effect on the child, and people often link what they see in the child to reasons such as ‘oh he/she's like that because he had the mother's milk’ . . . such as the way he develops his personality or intelligence (Participant 8, Bicultural)

I was always told by mum that you can always tell the children who have had their mother's milk because they develop stronger characters and personalities than those that don't have breast milk from their mother (Participant 11, Bicultural)

. . . through our culture we're told its something good you can do for your baby, it delivers goodness and makes the baby grow up to be a good person (Participant 18, Low acculturation)

Thus, women experienced varying cultural teachings about breastfeeding as a method of choice for feeding their child. Often, these teachings were in contrast to one another. For these women, it was difficult to accommodate breastfeeding into their lives because of various cultural issues such as embarrassment in front of other family members, and the overriding demands placed on them as a daughter in law.

‘The most convenient method for me’

All women regardless of level of acculturation opted for a ‘convenient’ method of feeding. However, convenience held different meanings across the three groups of women. Women classified as showing low levels of acculturation experienced difficulties in breastfeeding; thus, bottle feeding was a better option for them as it allowed them to overcome such difficulties.

I initially breastfed but I found it really difficult and when I expressed these difficulties I was encouraged to formula feed instead to make it easier. Formula feeding seemed to be an easy option (Participant, 9, Low levels of acculturation)

I fed my baby 1 day on breast milk but it's very painful, so I went to the formula, this was much easier for me (Participant 18, low acculturation)

For other women, formula feeding was chosen over breastfeeding because it was a way of sharing the responsibility of feeding the child, and allowed them to overcome the embarrassment associated with breastfeeding;

Religion teaches breastfeeding best but in culture taught that formula feeding is the most convenient, because there is less embarrassment for the mum (Participant 9, Low acculturation)

Thus, women classified as having low levels of acculturation opted to bottle‐feed in response to difficulties or embarrassment that they had experienced, while highly acculturated women and those classified as bicultural bottle fed as it was perceived to be an easier option than breastfeeding and it enabled them to share the experience of feeding the child with other members of the family.

I bottle fed my baby it was a good experience because it was quick and easy . . . My mother‐in‐law encouraged bottle feeding for my own benefit i was able to share the feeding with her which was good for me (Participant 22, Highly acculturated)

The fact that i was living with my parents meant that they could bottle feed my child whilst i had some rest, I think this was the main reason for me changing from breast to bottle (Participant 14, Highly acculturated);

‘Fulfilling the baby's needs’

Women classified as having low levels of acculturation and those classified as bicultural who formula fed or intended to formula feed did so in response to their child's perceived demands.

I don't think the baby would get full up with a small amount of milk from breast . . . by giving them formula feed you know you will fill them up (Participant 17, Low acculturation)

There was a perception that formula feeding was meeting the child's nutritional demands and the baby was more content with this form of feeding rather than breastfeeding.

I felt that my baby wasn't happy with me breastfeeding so switched to formula‐feeding. After giving formula my baby was much happier (Participant 7, Bicultural)

The perceptions of the nutritional adequacy of formula milk were strengthened by other family members.

I didn't get much encouragement from my family . . . they said that my milk might not be good enough for the child and might not be providing it with the things the baby needs to properly develop (Participant 11, Bicultural)

None of my cousins breastfed . . . they told me that breast milk is very thin and less nutritious for the child (Participant 12, Low acculturation)

‘Breast is not always best’; experiences of information and role conflict

All women (regardless of their acculturation status) experienced conflict between whether to breast feed or to bottle feed. Women from these groups experienced ‘mixed messages’ (Participant one, Bicultural) about breastfeeding. To better understand this experience, the original theme of ‘conflict’ has been further divided into information conflict and role conflict to reflect areas that conflict stemmed from.

Information conflict

Women experienced conflicting advice about breastfeeding as a method for feeding their child. This was a pertinent issue for Pakistani women in the sample, who experienced this in terms of their religion (Islam) teaching them ‘breast is best’ but many cultural factors affected their abilities to follow such religious teachings.

In religion need to do it for 2 years, but elders tell me to breastfeed in private it's not really good to do it in front of people but then it's a mix message (Participant 9, Low acculturation)

Religion teaches to breastfeed, but my decision not to do I was because of cultural things like it's not nice to do it in front of people (Participant 22, Highly acculturated)

Islamically, we're told that it's good for the baby to be breastfed. But in our culture we have so many other things to think about, for example we live in extended families and its said not to be appropriate to be doing that especially when there are people always around your house (Participant 6, Low acculturation)

Therefore, cultural messages about breastfeeding countered the pro‐breastfeeding teachings that Islam taught them.

Conflict was also experienced between the information they received from both their mothers and their mothers in law. Often, the women' mothers encouraged the women to breastfeed while the mothers in law suggested that formula feeding would be a better option for them. This may be a function of whether these older relatives have been resident in the UK for many years.

When I lived in Pakistan my mum always encouraged me to breastfeed my baby but after I got married and came here I was told something different by my mother in law (Participant 9, Low acculturation)

I had contrasting opinions from my mother in law and mother because I was told by my mother to breastfeed but told by my mother in law to formula feed (Participant 6, Low acculturation)

My mother in law encouraged breastfeeding for my own benefit, i was able to share the feeding with her which was good for me (Participant 22, Highly acculturated)

Religious and cultural teachings (Shaikh & Ahmed 2006) and the advice of elders such as mother's and mothers in laws are said to be valuable sources of information that help to promote breastfeeding in this sub‐group of women (Ingram et al. 2002). However, for the women in the sample, these sources of information were inconsistent with one another. The conflict between the different types of information that the women received had an overall detrimental effect on women's decisions to breastfeed.

Elders told me to breastfeed in private because it's not really good to do it in front of people. . . . But then it's a mix message because of this I just thought it would be easier to formula feed (Participant 1, Bicultural)

Role conflict

Women perceived themselves to have two competing roles; as a mother and a daughter in law. Breastfeeding was seen to be incompatible with the latter role. Formula feeding allowed the women to resolve the conflicts experienced between the two roles.

I only breastfed for a while, because when I started I realised that my mother in law was right, I wasn't able to cope with everything myself. Formula‐feeding meant that whilst I was doing other work, my mother in law was able to help out and feed my baby. (Participant 9, Low acculturation)

. . . parents advised that I should breastfeed but found it really hard to fit into my life and the things that I have to do around the house, like housework and looking after my mother in law (Participant 5, Low acculturation)

. . . also there's no time to feed the baby because you have to attend to the guests that come so in that sense it has influenced my choice because I've had to {choose} what feeding method fits into my life as well (Participant 16, Bicultural)

Formula feeding was a way of coping with the demands placed on them as a daughter in law.

Culture played a major role I think, especially a lot to do with the daughter in law's role in the house. We need to cater to guests and cook so my mother in law suggested that it would be better if I just formula fed (Participant 4, Low acculturation)

‘Formula feeding culture – learning by observation’

Across all three groups, there was an awareness of living in a formula‐feeding culture. The extent to which this awareness had an impact on the women's own infant feeding decisions varied by level of acculturation. Highly acculturated and bicultural women used the formula feeding culture as a point of reference to guide their own choice of feeding;

In our local community (reference to South Asian peers), there seems to be a competition and people want to compete with one another, its an attitude of ‘oh if she's doing it then I've got to do it’ I've heard a lot of that in our community they see one woman bottle feeding then they have to do it too (Participant 8, Bicultural)

I can see how mothers might be influenced by seeing other mothers and how they feed their baby, ‘cos if you're told to breastfeed but then you see every other mother (reference to peers from Anglo culture) bottle feed why would you want to go through all the hassle? (Participant 13, Highly acculturated)

There was a need for these women to fit into the ‘norm’ rather than engage in a form of feeding that was thought to deviate from such a norm.

You get an idea of what's right from the people around you don't you, you don't want to be doing something that you see no one else doing(reference Anglo culture) (Participant 22, Highly acculturated)

I think when it comes to feeding your baby the first thing you think of is formula feeding because everyone seems to do it (reference to Anglo culture), you very rarely see women, especially in our community (peer from the South Asian culture), breastfeeding (Participant number 7, highly acculturated)

I thought if they're (Peers from the Anglo culture) doing it and there's no harm then there's no need for me to go through the pain of trying to breastfeed when I could give them the formula (Participant 18, low acculturation)

When I was back home everyone breastfed their baby, here I don't see it as much (referring to the Anglo culture) . . . you don't know what people might think of you when they see you doing it. I felt as if they might judge me or something because its something we do at home and its no that much common here I don't think (Participant 19, Highly acculturated)

Women displaying low levels of acculturation were also aware of living in a formula‐feeding culture; but this awareness did not have a large influence on their choice of feeding.

In Pakistan most people would breastfeed but here (referring to the Anglo Culture) everyone bottle feeds . . . but final decision to bottle feed was mine (Participant 17, low acculturation)

. . . I've heard a lot of that in our community (South Asian Culture) they see one woman bottle feeding then they have to do it too just because they've seen the lady down the road doing it . . . People around my area don't respect breastfeeding like they should and don't understand it's a gift you can give the child (Participant 5, Low acculturation)

Discussion

Given that infant feeding choices are embedded in the context of ethnic and cultural beliefs (Kannan et al. 1999), it is important to understand the influence of such beliefs on women's infant feeding decisions. This is one of the first studies to place beliefs about breastfeeding or breastfeeding behaviours of a sample of South Asian women within an acculturation framework in England.

What follows is a summary of the findings obtained, they are not intended to be generalized to the South Asian population as a whole, but to document the experiences of the women in the sample. Although the majority of the sample did not continue to exclusively breastfeed, the findings are of interest in exploring women's beliefs about breastfeeding rather than how acculturation may have had an influence on their actual breastfeeding behaviour.

Low acculturation levels are said to have a protective effect on rates of breastfeeding, in the context of living in a country with a low breastfeeding rate (Gibson et al. 2005). Findings from this exploratory study may be used to better understand why this may be the case. Although women displaying low levels of acculturation in the sample were aware of living in a formula‐feeding culture in the UK, it had little influence on their beliefs about breastfeeding and breastfeeding intentions. This finding is in contrast to previous research where living in a bottle‐feeding culture has often been cited as a reason for women opting to formula feed their child (Scott & Mostyn 2003). This sub‐group of women drew upon South Asian cultural teachings about the psychological benefits of breastfeeding which helped inform their decision to breastfeed. Breastfeeding for these women was perceived to be more appropriate than formula feeding. When these women did opt to formula feed their child, it was in response to conflict they experienced either between the information they received about the best form of feeding (breastfeeding vs. formula feeding) or between their roles as a mother and daughter in law. Opting to formula feed acted to resolve the conflict experienced.

In contrast, highly acculturated and bicultural women experienced a need to merge their feeding decision with the perceived formula feeding norm of the UK. These women also experienced information conflict and role conflict; however, an awareness of the perceived UK culture of formula feeding governed their final feeding decision. Therefore, the influence of social norms could be distinguished depending on the women's level of acculturation. Highly acculturated and bicultural women did not want to be seen to be deviating from the perceived feeding norm of the UK, particularly as there was a belief that formula feeding is the ‘way in the UK’. Women displaying low levels of acculturation were less inclined to fit into this norm even though they were aware that they may ‘get funny looks’ when breastfeeding. Anticipated negative consequences of them breastfeeding did not deter them from planning to engage in and engaging in breastfeeding.

Prenatal and postnatal support for these women might usefully focus on a family‐orientated intervention to support the mother in her nutritional role relative to her social duties as a daughter in law.

Research reviewed above provides a confusing picture of how acculturation affects people trying to adapt to a new environment (Cabassa 2004). This is in part because of a reliance on proxy measures of acculturation such as country of birth and length of residency in a new country (Landrine & Klonoff 2004). The present study utilized a bidimensional measure of acculturation which makes a distinction between mere exposure to a culture and the psychological changes that are brought about by the actual involvement in a new culture (Matsudaira 2006). Further, it allowed the possibility of two orthogonal behavioural changes in the women to be explored, that is, the maintenance of their culture of origin and the adherence to the dominant or host culture (Berry 1997). Women could therefore be classified as ‘bicultural’ (i.e. showing high degree of orientation towards the culture of the UK as well as their culture of origin) rather than classifying their orientation towards their culture of origin or the culture of the UK (which is the case when proxy one‐dimensional measures are adopted). We suggest that this simple measure can be used in research as well as forming a means for practitioners to determine how best to tailor their interventions for infant feeding.

There is an assumption that individuals born within the host country display higher levels of acculturation than those born outside the host country as such individuals experience a greater period of exposure and have greater opportunity to adopt Western values (Abraido‐Lanza et al. 2006). However, there were some instances in the current study where women born in the UK displayed low levels of acculturation. This finding reinforces the idea that mere exposure to a culture does not suggest the same as psychological changes brought about by actual involvement in a culture (Matsudaira 2006).

Limitations of the current study

Given the exploratory nature of the study, convenience sampling was employed. It is acknowledged that using this form of recruitment, the sample is less likely to be representative of the total population than when using random sampling methods (Christenson 2006). Within this study,the majority of the sample comprised of women of Pakistani origin (n = 17/20). Given that there is heterogeneity between sub‐groups of the South Asian population (Bhopal 2002), it would be of interest to explore whether women from Indian and Bangladeshi communities perceive breastfeeding intentions and behaviours in similar ways (depending on their level of acculturation).

A limitation of the current study is the sample size. In total, 23 South Asian women were approached, of which 20 were willing to participate in the study. It is acknowledged that when employing qualitative research methodology, sampling should continue until data saturation is reached (Sandelowski 1995). However, because of pragmatic reasons, this was not possible, thus resulting in the small sample size. However, because of the study's exploratory nature, the findings were not intended to be directly generalizable to the South Asian population, but aimed to highlight the influence the acculturation process may have on women's beliefs about infant feeding choices and/or infant feeding choices. Future studies should ensure that larger and more culturally diverse samples of South Asian women are recruited.

Much of the work on acculturation and the development of acculturation scales derive from studies of Hispanic or Latino immigrant populations in the United States (Salant & Lauderdale 2003; Hunt et al. 2004). Although the scale used in this study has been reported to high reliability and validity (Cuellar et al. 1995; Carvajal et al. 2002), this may not be generalized to populations residing in the UK. Future research would benefit from assessing the reliability and validity of this adapted measure in South Asian populations residing in the UK.

Although previous research has tended to rely on behavioural indices within scales to assess associations between acculturation status and infant feeding, future research should seek to explore the role of cognitive and affective indices in relation to the acculturation experience of women and their infant‐feeding choices. This would help provide a deeper understanding of how factors such as perceived social norms may influence the choice of infant feeding in an acculturating population.

Future research would also benefit from exploring differences among the women's mothers and mothers in law. For example, exploring country of birth (if possible acculturation levels) would lend insight to why mothers and mothers in law had sometimes conflicting view point in terms of the method of infant feeding that the woman should adopt. This could further extend to exploring the husband's views on infant feeding and how this may influence the women's infant‐feeding decision. These aspects are important to consider because it may be possible that even those women classified as having low levels of acculturation may have referents (e.g. mother, mother in law or husband) that are highly acculturated to the westernized norms of the UK.

Practical implications

Acculturation, rather than simply ethnicity, is a key variable in health research (Landrine & Klonoff 2004). This distinction has practical implications for research and practice in relation to infant feeding. Further, attention needs to be paid to the meaning breastfeeding or formula feeding holds for these women, as such meanings have a significant impact on how they perceive that particular method and whether they decide to initiate breastfeeding.

There may be a perception among health professionals that South Asian women breastfeed more often whil White women tend to bottle feed (Shaw et al. 2003). However, the current findings may help to challenge these misconceptions and strongly encourage health service providers to meet the needs of an acculturating population. For example, women displaying low levels of acculturation require strong encouragement to support choices that favour breastfeeding. Particular support should be targeted on these women as they are more vulnerable to social influences favouring formula feeding within the cultures that they have become acculturated towards (Abraido‐Lanza et al. 2006). In contrast, women displaying high levels of acculturation or displaying biculturalism need to be aware that ‘West is not always best’. The use of role models from the Anglo Culture may help to correct misconceptions that ‘formula feeding is the way in the United Kingdom’. Observing peers, or highly valued role models from the Anglo culture successfully engaging in breastfeeding, may allow women from South Asian sub‐groups to appreciate the role of breastfeeding in a Western culture such as the UK.

Breastfeeding promotion efforts targeted at women from the Pakistani community already make use of religious teachings as a means of tailoring the information to this sub‐sample of the population. Slogans such as ‘Islam encourages breastfeeding’ (Heart of Birmingham NHS Trust, NHS poster) are used in efforts to increase breastfeeding rates in this sub‐group. However, the findings of this study are relevant to the design of health promotion and infant feeding support to South Asian women. All the women were aware of the religious basis for breastfeeding, but this did not govern their feeding decision. Women experienced conflict between religious and cultural teachings about infant feeding, but it was often the cultural consequences of a particular method that governed their decision rather than religious teachings. For example, women often felt that the cultural meaning of being a daughter in law and the demands that came with this role meant that it was difficult to accommodate breastfeeding as a form of feeding their child. Cultural meanings, such as this, that surround a particular form of feeding in this type of population are often interpreted by health professionals as misunderstandings or misconceptions (Kwok et al. 2006). However, they are meaningful to the women, and provide logical reasons as to why they are unable to engage in breastfeeding. Health promotion efforts are unlikely to be successful if the cultural consequences related to breastfeeding in these women are not addressed.

We recommend that significant others in a women's life, particularly the mothers in law, are included in any effort to promote breastfeeding, as this ensures that women are receiving the right messages about the benefits of breastfeeding rather than ‘mix messages’ (Participant one) about the suitability of it as a method of feeding their child. Beliefs of mothers in law have been the focus of health promotion research and interventions (Ingram et al. 2002). There is an indication from the findings of our study that highly acculturated women use generalized social norms about infant feeding practices to inform their own choice of feeding. Therefore these women may benefit from initiatives that expose them to peers who are engaging in successful breastfeeding. It is suggested that women would learn behaviours from role models that they perceive to be similar to themselves, for example, from within the South Asian population (Hoddinott & Pill 1999). However, the women in this sample may also possibly benefit from observing peers from the Anglo culture breastfeeding as well as the South Asian culture. All women regardless of their levels of acculturation had observed the bottle‐feeding culture of the UK, not only in their community, but also generally in a wider context. Observing Anglo peers breastfeeding would highlight that not ‘everyone’ in the UK bottle‐feeds their babies, and that breastfeeding is also observed in the Anglo culture (see pp. 19–20). Many of the women in the study lived in areas where there was a dense South Asian population, therefore the few encounters they had with the dominant cultural values in British Society was when visiting the Children's Centres. This point is also supported by Bowler (1993). Pre‐ and post‐natal support for these women might usefully include challenging perceptions of the relative social value of feeding choices as well as interventions relevant to the majority White population. Observing peers from the Anglo culture successfully engaging in breastfeeding may allow these women to appreciate the role of breastfeeding in a Western culture, and help to correct misconceptions held that formula feeding is the norm in the UK.

Conclusion

There is a belief that breastfeeding promotion and maternity services display a lack of connectedness with their population and fail to address the environments in which mothers make decisions about breastfeeding (Bailey et al. 2004). It is hoped that this study provides valuable information and increases the ‘connectedness’ between maternity services and the South Asian target population, by exploring the impact of acculturation on breastfeeding attitudes and experiences. An awareness of the social and cultural environments that may act upon the women's willingness to breastfeed is needed before any health promotion efforts are to be successful. It is well established that the South Asian population is a heterogeneous population (Bhopal 2002) on a number of variables such as language, religion and cultural beliefs. This heterogeneity is more obvious when the level of acculturation is explored. This variable needs to be considered when promoting health services, as the findings indicate that the information needs to be tailored depending on a women's level of acculturation. For example, the breastfeeding behaviours and the positive beliefs that women displaying low levels of acculturation hold need to be protected by ensuring they are made aware of the importance of breastfeeding and the decision to breastfeed being the optimal form of feeding for their child. This will ensure that the detrimental effects that accompany the progressions from low to high acculturation (Abraido‐Lanza et al. 2006) are not experienced

It is acknowledged, however, that individuals may be motivated to become acculturated to Western beliefs (Kim 2001). For this reason, it may also be useful to ensure that women are exposed to positive ‘westernised’ norms or attitudes towards breastfeeding as there may be potential for women to reject their pre‐existing positive beliefs of breastfeeding as being' old‐fashioned'.

Breastfeeding is believed to be beneficial and a gift from God in South Asia, hence its widespread use (Choudhry 1995), but such beliefs may change because of the effects of acculturation (Meleis 1991). There is therefore a strong need to preserve these previously practised healthy behaviours and educate women, such as those from the South Asian populations that formula feeding is not always a valued aspect of living in Western cultures (Bowes & Domokos 1998). Given the important health benefits of breastfeeding, failing to engage in this health behaviour presents a public health issue (Lutter 2000). Healthcare commissioners and healthcare practitioners may be basing policies and professional practices on ethnicity alone, which could lead to an incomplete understanding of the needs of substantial proportions of the population they serve. There is increasing recognition that there needs to be a better understanding of the deep‐rooted processes underpinning the infant feeding decisions of these women (Bailey et al. 2004); therefore, it is hoped that the present study moves beyond description and offers explanations as to how the process of acculturation to a host country, in this case England, exerts largely detrimental influences on the breastfeeding practices of this sample of South Asian women.

Source of funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the staff and users of the Children's Centres in South Birmingham and Central Birmingham who participated in the interviews. Without their invaluable contribution, this project would not have been possible.

References

- Abraido‐Lanza A.F., Armbrister A.N., Florez R.K. & Aguirre A.N. (2006) Toward a theory driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health 96, 1342–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C., Pain H.R. & Aarvold E.J. (2004) A ‘give it a go’ breastfeeding culture and early cessation among low income mothers. Midwifery 20, 240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W. (1997) Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review 46, 5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal S.R. (2002) Heterogeneity among Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis is key to racial inequalities. British Medical Journal 325, 903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolling K., Grant C., Hamlyn B. & Thornton A. (2005) Infant Feeding Survey 2005 – A Survey Conducted on Behalf of The Information Centre for Health and Social Care and the UK Health Departments by BMRB Social Research. National Health Service: London. [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K.A., Freeman K. & Trombley M. (2005) Country of origin and race/ethnicity: impact on breastfeeding intentions. Journal of Human Lactation 21, 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes A. & Domokos T.M. (1998) Negotiating breastfeeding: Pakistani and White women, and their experiences in hospital and at home. Sociological Research Online. Available at: http://www.socresonline.orh.uk/3/3/5.html. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler I. (1993) ‘They're not the same as us’: midwives stereotypes of South Asian descent maternity patients. Sociology of Health and Illness 15, 158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. & Clarke V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard P. (1991) A method of analysis: interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nursing Education Today 11, 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa L.J. (2004) Measuring acculturation: where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioural Sciences 25, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal S.C., Hanson C.E., Romero A.J. & Coyle K.K. (2002) Behavioural risk factors and protective factors in adolescents: a comparison of Latinos and Non Latino whites. Ethnicity and Health 7, 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry U.K. (1995) Traditional practices of women from India: pregnancy, childbirth and newborn care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 26, 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson O.D. (2006) Family acculturation, family involvement, and family functioning among Mexican‐Americans. Journal of Leisure Research 38, 475–495. Fourth Quarter. Available at: http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3702/is_4_38/ai_n29309809/. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I., Arnold B. & Maldonado R. (1995) Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans‐II: a revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioural Sciences 17, 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (1998) Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health: Report. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (1999) Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2003) Priorities and Planning Framework 2003–2006. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2004) Choosing Health: Making Healthier Choices Easier. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L., Renfrew M., McFadden A., McCormick F., Herbert G. & Thomas J. (2005) Promotion of breastfeeding initiation and duration: evidence into practice briefing. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/EAB_Breastfeeding_final_version.pdf.

- Gibson M.N., Diaz V.A., Manous A.G. & Geesey M.E. (2005) Prevalence of breastfeeding and acculturation in Hispanics: results from NHANES 1999–2000 study. Birth 32, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson‐Davis C.M. & Brooks‐Gunn J. (2006) Couples immigration status and ethnicity as determinants of breastfeeding. American Journal of Public Health 96, 641–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith L.J., Tate A.R. & Dezateux C. (2005) The contribution of parental and community ethnicity to breastfeeding practices: evidence from the millennium cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology 34, 1378–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P. & Pill R. (1999) Qualitative study of decisions about infant feeding among women in East end of London. British Medical Journal 318, 30–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L.M., Schneider S. & Comer B. (2004) Should ‘acculturation’ be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science and Medicine 59, 973–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J., Johnson D. & Hamid N. (2002) South Asian grandmothers' influence on breast feeding in Bristol. Midwifery 19, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. (2008) Infant Feeding Survey 2005: A Commentary on Infant Feeding Practices in the UK – Position Statement by the Scientific Advisory Committee. The Stationary Office: London. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/EAB_Breastfeeding_final_version.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S., Carruth B.R. & Skinner J. (1999) Neonatal feeding practices of Anglo‐American mothers and Asian Indian mothers in the United States and India. Journal of Nutrition, Education and Behaviour 36, 315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z. (1991) Are breastfeeding patterns in Pakistan changing? Pakistan Development Review 30, 297–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.Y. (2001) Becoming intercultural: An integrated theory of communication and cross‐cultural adaptation. Sage: Thousand Oaks, California. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok C., Sullivan G. & Cant R. (2006) The role of culture in breast health practices among Chinese‐Australian women. Patient Education and Counseling 64, 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H. & Klonoff E.A. (2004) Culture change and ethnic‐minority health behaviour: an operant theory of acculturation. Journal of Behavioural Medicine 27, 527–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter C. (2000) Length of exclusive breastfeeding: linking biology and scientific evidence to public health recommendations. Issues and Opinions in Nutrition 130, 1335–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G. & Gamba R.J. (1996) A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hispanic Journal of Behavioural Sciences 18, 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira T. (2006) Measures of psychological acculturation: a review. Transcultural Psychiatry 43, 462–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddings F.S. & Porter J. (2007) Pakistani women: feeding decisions. Midwives 10, 328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis H.I. (1991) Between two cultures: identity, roles and health. Health Care for Women International 12, 365–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland E. & Vanwerson A.V. (2007) Stigma, sexually transmitted infections and attendance at GUM clinics. Journal of Health Psychology 12, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassin D.K., Markides K.S., Banowski T., Richardson C.J., Mikrut W.D. & Bee D.E. (1993) Acculturation and breastfeeding on the United States‐Mexico border. American Journal of Medical Science 306, 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordin J. & Gill‐Hopple K. (2001) Breastfeeding care in multicultural populations: clinical issues. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 30, 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter J.C. (1992) Attitudes of Vietnamese women to baby feeding practices before and after immigration to Sydney, Australia. Midwifery 8, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salant S. & Lauderdale D.S. (2003) Measuring culture: A critical view of acculturation and health in Asian immigrant populations. Social Science & Medicine 57, 71–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (1995) Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health 18, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J.A. & Mostyn T. (2003) Women's experiences of breastfeeding in a formula feeding culture. Journal of Human Lactation 19, 270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrimshaw S.C., Engle D.L., Arnold L. & Haynes K. (1987) Factors affecting breastfeeding among women of Mexican origin or descents in Los Angeles. American Journal of Public Health 77, 467–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh U. & Ahmed O. (2006) Islam and infant feeding. Breastfeeding Medicine 1, 164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R.L., Wallace L.M. & Bansal M. (2003) Is breast best? Perceptions of infant feeding. Community Practitioner 76, 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Snauwaert B., Soenens B., Vanbeselaere N. & Boen F. (2003) When integration does not necessarily imply integration. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 34, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson V. & Power K.G. (2005) Initiation and continuation of breastfeeding: theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Advanced Nursing 50, 272–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. (2002) Social Focus in Brief: Ethnicity 2002. Office for National Statistics: London. [Google Scholar]