Abstract

This review addresses the association between restrictive feeding practices by parents and the development of overweight in children. To date, only one parent feeding domain – feeding restriction – has been consistently linked to variations in child eating patterns or weight status. Despite challenges to unravelling causal pathways, the most current data suggest that restrictive feeding practices are elicited by child characteristics (e.g. weight status or obesity risk) and depend on parent characteristics as well. Restriction, in turn, may maintain or exacerbate child overweight. There remain important questions to be addressed in this literature, pertinent both to the development of childhood overweight and clinically to overweight prevention. Two areas of importance are the roles of cultural differences, as well as genes that confer risk for overweight, on the relationship between restriction and child weight status.

Keywords: childhood obesity, restriction, gene‐environment interaction, parenting, behaviour genetics

Which feeding domains are related to child weight status?

Childhood overweight is one of the most daunting public health disorders confronting society. With a prevalence in the United States of 15.3% among 6–11 years‐olds (Ogden et al., 2002), it is associated with numerous medical complications including risk factors for type 2 diabetes and psychosocial complications (Cooperberg & Faith, 2004). Thus, identification of the causes of childhood overweight is critical in order to develop more effective prevention strategies.

Childhood overweight is a family disorder in that parents transmit genes and construct environments that permit some children to gain weight more easily than others. Parental feeding styles may be one specific pathway by which parents promote overeating and thereby overweight in children. Indeed, common sense suggests that the ways in which parents feed their children should contribute to a child's weight status. Curiously, data to support this claim have been limited. In a comprehensive review, we found that most parental feeding domains did not show significant associations with child eating or weight status outcomes (Faith et al., 2004). Examples of feeding styles that did not show associations were maternal tendencies to feed on schedule, use of food to calm infants, social interactions during feeding, emotional feeding and instrumental feeding (Baughcum et al., 2001; Wardle et al., 2002). The only feeding domain that did show consistent associations with child outcomes was restriction of child eating.

The Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) is a self‐report questionnaire comprised of 31 items that assess parental child feeding attitudes and practices on seven dimensions including parental restriction (Birch et al., 2001). All items are measured using a five‐point Likert scale. As measured by the CFQ, restriction refers to caregiver efforts to control or limit child food choices or how much she/he eats. Sample items that assess restriction from the CFQ are: ‘I have to be sure that my child does not eat too many high‐fat foods’; ‘I intentionally keep some foods out of my child's reach’; and ‘If I did not guide or regulate my child's eating, s/he would eat too much of his/her favorite foods’. A high score on the restriction scale indicates a high level of parental restriction. An association between feeding restriction and child outcomes has been reported in a study with infants (Fisher et al., 2000), as well as in cross‐sectional (Fisher & Birch, 1999a; Birch & Fisher, 2000) and prospective studies with children (Birch et al., 2003; Faith et al., in press). Hence, restriction – more than any other domain – has been linked to child eating and weight status to date. The question then becomes what are the causal pathways underlying this association?

Restriction may influence child eating behaviour

To the extent that restriction promotes the development of overweight in children, what mechanisms might account for this effect? Restricting access to highly palatable, energy‐dense snack foods has been shown to increase children's preferences and requests for such forbidden foods in laboratory feeding studies (Fisher & Birch, 1999a, 1999b). Thus, excessive parental efforts to restrict access to foods that children desire might have the counter‐productive effect of increasing children's preferences for those foods, at least in the short run.

Restriction also has been linked to increased ‘eating in the absence of hunger’ by children (Fisher & Birch, 1999a). Eating in the absence of hunger is similar to the behavioural trait of disinhibited eating, a dimension of disordered eating in adults. Eating in the absence of hunger is measured in an experimental laboratory setting, during which children have free access to eat as much palatable snack food as desired despite the fact that they have recently completed lunch and indicated that they were full. In one prospective study, Fisher & Birch (2002) reported that for each incremental unit of maternal feeding restriction on the CFQ at daughter age 5 years, daughters were subsequently 2.1 times more likely to score high on eating in the absence of hunger at age 7 years (95% CI: 1.2–3.8, P < 0.05). Thus, restriction may promote overweight in children by discouraging the development of healthy eating patterns (e.g. by attending to internal appetite) and, instead, by training certain children to eat in response to external cues.

Restriction is elicited by child characteristics

Traditional models of child development posited a unidirectional model that emphasized how children are influenced by their parents. Parents were conceptualized as influencing child behaviour, with less attention to the ways in which children influence parents (Rowe, 1994). However, there is now ample evidence from developmental genetic studies that parent–child interactions are usually a dynamic process in which children elicit reactions from their parents (Lytton, 1980; Reiss et al., 2000). In other domains of child development, child traits have been shown to have a quantifiable genetic influence to which parents are likely responding (Neiderhiser et al., 1999). These data cast in new light a probable bidirectional parent–child feeding dynamic.

Apropos to parent–child feeding relationships, recent studies suggest that restriction of child eating is partially elicited by child weight status. Preliminary evidence came from Birch & Fisher's (2000) path analytic study that tested the relations among maternal restriction of daughters’ eating, their ability to regulate food intake, their 3‐day food intake and their relative weight. Results of this cross‐sectional analysis of 197 mother–daughter dyads indicated that maternal restriction of daughters’ eating was partially elicited by increased daughter body weight. That is, mothers were more likely to restrict the eating of heavier than thinner children, which in turn perpetuated the daughters’ overeating and overweight.

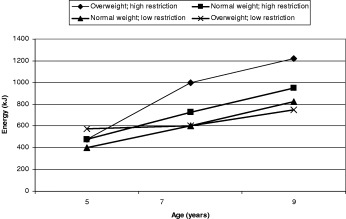

Birch et al. (2003) recently tested the developmental trajectories of eating in the absence of hunger among girls evaluated at 5, 7 and 9 years of age. As shown in Fig. 1, eating in the absence of hunger showed the greatest increase among daughters who had the most restrictive mothers and who were overweight at the initial year 5 assessment. Thus, the apparent effects of restriction on eating in the absence of hunger were dependent on daughters’ initial body weight, with the most ‘detrimental’ effects for children who were initially the heaviest. Thus, parental restriction may have been partially responsive to child overweight status.

Figure 1.

Maternal restriction and child overweight status at 5 years of age predict the development of child eating in the absence of hunger (EAH) at child ages 5–9 years. The figure presents 4‐year trajectories for changes in eating in the absence of hunger levels, which are expressed as total energy intake (kJ) during laboratory protocol meals. Trajectories are displayed for the following four groups of daughters, based on daughter overweight status and degree of maternal feeding restriction at 5 years of age: overweight + high restriction (◆); overweight + low restriction (×); normal weight + high restriction (▪); normal weight + low restriction (s). EAH levels increased between 5 and 9 years of age for all groups, however, this increase was most pronounced for girls who were overweight and whose eating was restricted at age 5 years.

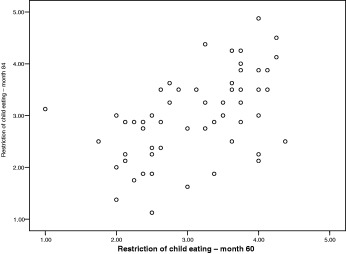

We recently conducted a prospective study of prepubertal children who were born at high risk or low risk for overweight on the basis of maternal prepregnancy body weight (Faith et al., in press). Children were evaluated at ages 5–7 years with respect to weight and height, at which time parental restriction of child eating was also measured by the CFQ. Results revealed that parental restriction of child eating was relatively stable over the 2 years (Fig. 2), although the association was statistically moderate in size (Pearson's r = 0.54, P < 0.001). At the same time, child weight status was also stable over the 2 years. These findings suggest the possibility that parental restriction of child eating and child weight status may be substantially ‘intertwined’ in their dynamic. Second, restriction of child eating at year 5 predicted increased child BMI z score at year 7 among children born at high risk for obesity but not among children born at low risk for obesity. This suggests that the association between parental restriction of child eating and excess child weight gain depends on the child's genetic vulnerability to become overweight. Moreover, when we controlled for prior child growth trajectories (by statistically controlling for child weight status at age 3), the prospective effect of feeding restriction on child BMI score was attenuated. This finding suggests that parental restriction of child eating is partially responsive to a child's increased weight status.

Figure 2.

Association between parental restriction of child eating behaviour at child ages 5 and 7 years. Restriction was measured by the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ), which has a range of 1–5 with higher scores representing greater parental restriction of child eating.

Restriction and ethnicity differences

There have been surprisingly few studies testing race or ethnicity differences in restrictive feeding practices by parents, despite discussions of the impact of culture on food choices (Rozin, 1996). In a study of 120 families residing in Alabama, African American mothers reported significantly greater restriction of eating towards their children than did Caucasian mothers (2002a, 2002b). In a population‐based study of 1083 mothers residing across the United States and participating in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Caucasian mothers reported allotting significantly greater child food choice during breakfast or lunch than African American or Hispanic mothers (Faith et al., 2003).

Among 22 studies testing the association between parental feeding style and child eating and weight status (Faith et al., 2004), 77% of the samples were Caucasian on average. Among these studies, 27% included only Caucasian families, 5% included only African American families, 14% included Caucasians plus one ethnic minority group, 32% included Caucasians plus two ethnic minority groups, and 24% did not report data on ethnicity. However, most studies were underpowered to test for ethnicity differences in the relationship between parental feeding styles and child weight status. Among the 22 studies reviewed, 70% collapsed ethnicity in analyses, 20% statistically controlled for the effects of ethnicity in analyses, and 10% conducted ethnicity specific analyses. Thus, the role of ethnicity, race and culture in parental feeding restriction, and its putative effect on child weight status, remains a largely unanswered research question.

The benefits of restriction?

For children who are overweight (i.e. body mass index ≥95th age‐ and sex‐specific percentile) and for whom prevention of weight gain is desirable, ‘restricting’ access to energy‐dense, high‐sugar foods may be desirable. Parental involvement appears to be a key component of successful weight loss for overweight children and, for these families, a reduction in total daily energy intake is typically prescribed (Faith et al., 2001). A key question in this field therefore is whether or not any detrimental effects of feeding restriction depend on a child's initial overweight status. It may be the case that restriction may be more detrimental among younger child who are not overweight and are still developing eating patterns compared with older children or adolescents who are already overweight and would benefit from weight loss.

Conclusions

To date, restriction of child eating is the only parental feeding domain that has been consistently associated with variation in child eating behaviour or weight status. Parental feeding patterns are not random and, in this light, restriction is most likely elicited in part by child eating patterns or perceived excess body weight. The ways in which excessive restriction may have residual detrimental effects on child development remains an important question. The roles of genetic vulnerability to obesity, broader cultural attitudes and ethnic differences, and global parenting styles warrant additional research, as do the potential ways in which feeding styles might aid the prevention and treatment of childhood overweight.

References

- Baughcum A.E., Powers S.W., Johnson S.B., Chamberlin L.A., Deeks C.M., Jain A. et al. (2001) Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 22, 391– 408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch L.L. & Fisher J.O. (2000) Mothers’ child‐feeding practices influence daughters’ eating and weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 71, 1054 –1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch L.L., Fisher J.O., Grimm‐Thomas K., Markey C.N., Sawyer R. & Johnson S.L. (2001) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite, 36, 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch L.L., Davison K.K. & Fisher J.O. (2003) Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78, 215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperberg J. & Faith M.S. (2004) Treatment of obesity II: childhood and adolescent obesity In: Handbook of Eating Disorders and Obesity (ed. Thompson J.K.), pp. 443–460. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken. [Google Scholar]

- Faith M.S., Berkowitz R.I., Stallings V.A., Kerns J., Story M. & Stunkard A.J. (2004) Parental feeding styles and child body mass index: prospective analysis of a gene‐environment interaction. Pediatrics, 114, e429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith M.S., Saelens B.E., Wilfley D.E. & Allison D.B. (2001) Behavioral treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity: current status, challenges, and future directions In: Body Image, Eating Disorders & Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Theory Assessment Treatment and Prevention (eds Thompson J.K. & Smolak L.), pp. 313–340. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Faith M.S., Heshka S., Keller K.L., Sherry B., Matz P.E., Pietrobelli A. et al. (2003) Maternal‐child feeding patterns and child body weight: findings from a population‐based sample. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 157, 926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith M.S., Scanlon K.S., Birch L.L., Francis L. & Sherry B.L. (2004) Parent‐child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obesity Research, 12, 1711–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.O. & Birch L.L. (1999a) Restricting access to foods and children's eating. Appetite, 32, 405–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.O. & Birch L.L. (1999b) Restricting access to palatable foods affects children's behavioral response, food selection, and intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69, 1264 –1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.O. & Birch L.L. (2002) Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 year of age. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76, 226–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.O., Birch L.L., Smiciklas‐Wright H. & Picciano M.F. (2000) Breast‐feeding through the first year predicts maternal control in feeding and subsequent toddler energy intakes. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100, 641–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. (1980) Parent–Child Interaction: The Socialization Process Observed in Twin and Singleton Families. Plenum Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser J.M., Reiss D., Hetherington E.M. & Plomin R. (1999) Relationships between parenting and adolescent adjustment over time: genetic and environmental contributions. Developmental Psychology, 35, 680–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C.L., Flegal K.M., Carroll M.D. & Johnson C.L. (2002) Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 1728–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D., Neiderhiser J.M., Hetherington E.M. & Plomin R. (2000) The Relationship Code: Deciphering Genetic and Social Influences on Adolescent Development. Harvard University Press: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe D.C. (1994) The Limits of Family Influence: Genes, Experience, and Behavior. Guilford Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P. (1996) The socio‐cultural context of eating and food choice In: Food Choice Acceptance and Consumption (eds Meiselman H.L. & MacFie H.J.H.), 1st edn, pp. 83–104. Chapman. & Hall: London. [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt‐Metz D., Lindquist C.H., Birch L.L., Fisher J.O. & Goran M.I. (2002a) Relation between mothers’ child‐feeding practices and children's adiposity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 75, 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt‐Metz D., Lindquist C.H., Birch L.L., Fisher J.O. & Goran M.I. (2002b) Erratum. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 75, 1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J., Sanderson S., Guthrie C.A., Rapoport L. & Plomin R. (2002) Parental feeding style and the inter‐generational transmission of obesity risk. Obesity Research, 10, 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]