Abstract

The promotion of breastfeeding has been established as a global public health issue. Despite this global agenda, breastfeeding initiation and duration rates remain low in many countries. The lack of provision of adequate support to the breastfeeding mother is an important contributory factor to shorter duration of breastfeeding. Health professionals and voluntary breastfeeding supporters are in a prime position to work collaboratively to provide comprehensive support to the breastfeeding mother. However, a comparative evaluation of the breastfeeding support skills of voluntary breastfeeding supporters and health professionals has never been conducted. This study aimed to assess the breastfeeding support skills of midwives and Breastfeeding Network (BfN) supporters. Breastfeeding support skills were assessed using a between‐subjects design conducted with 15 midwives and 15 BfN supporters in the north‐west of England. Support skills were measured using the prevalidated Breastfeeding Support Skills Tool (BeSST), a questionnaire and video tool. Total scores on the BeSST were significantly higher in the BfN group (mean = 42.5 ± 6.4 SD) than in the midwife group (mean = 30.7 ± 8.2 SD) [t (26.5) = 4.4, P < 0.0001]. The BfN group has the breastfeeding support skills necessary to provide adequate assistance for breastfeeding mothers. An interagency and interdisciplinary collaborative model is crucial to developing a coherent and cohesive approach to the support infrastructure for breastfeeding women.

Keywords: breastfeeding, midwife, voluntary, lay, support

Introduction

The promotion of breastfeeding has been established as a global public health issue (WHO, 2002). Despite this global agenda, breastfeeding initiation and duration rates remain low in many countries. For example, the latest UK National Infant Feeding Survey reported that 69% of all mothers commenced breastfeeding. By 6 weeks, 42% of all mothers were still breastfeeding and by 4 months, less than a third of all mothers (28%) continued to breastfeed their babies. Ninety percent of women who stopped breastfeeding within 6 weeks stated that they would have liked to breastfeed for longer (Hamlyn et al., 2002). There are several factors thought to influence the initiation and sustainability of breastfeeding. A major reason for early cessation is the mothers’ perceived difficulty with breastfeeding rather than maternal choice (Dennis, 2002). A recent study found that women who believed they did not receive sufficient information about breastfeeding and those who perceived they had problems establishing breastfeeding were less likely to still exclusively breastfeed at 6–10 weeks postpartum (McLeod et al., 2002). The lack of provision of support for breastfeeding mothers is an important contributory factor to shorter duration of breastfeeding (Dykes & Williams, 1999; Bernaix, 2000). It seems clear therefore that, with appropriate support, mothers could be enabled to breastfeed for longer.

The term ‘support’ is utilized widely, often with a lack of clarity as to its meaning. This paper uses Sarafino's schema (Sarafino, 1994) to clarify the complex nature of support. The five components of support defined by Sarafino are:

-

•

emotional support: ‘the expression of empathy, caring and concern toward the person’;

-

•

esteem support: ‘positive regard for the person, encouragement and agreement with the individual's ideas or feelings’;

-

•

instrumental support: practical assistance;

-

•

informational support: provision of information;

-

•

network support: ‘providing a feeling of membership in a group of people who share interests and social activities’ (Sarafino, 1994, p. 103).

The health professional is in a prime position to provide support to the breastfeeding mother. However, although health professionals may positively influence breastfeeding women (Humenick et al., 1998; Kuan et al., 1999), they can also be a negative source of support when they provide women with inconsistent, inaccurate, and/or inadequate information and recommendations (Coreil et al., 1995; Patton et al. 1996; Humenick et al., 1998). Many studies have identified a significant knowledge deficit about breastfeeding amongst health professionals (Anderson & Geden, 1991; Becker, 1992; Lewinski, 1992; Freed et al., 1996; Bernaix, 2000; Fraser & Cullen, 2003). This evidence is alarming as it has been found that the best predictor of supportive behaviour amongst health professionals was their knowledge of breastfeeding (Patton et al., 1996; Bernaix, 2000; Cantrill et al., 2003).

These deficits have, in part, been tackled by the introduction of the global World Health Organization (WHO)/United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). Research has shown that midwives in the UK have improved breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes and support skills after attending the 20‐hour WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding Management Course (Dinwoodie et al., 2000; Hall Moran et al., 2000; Wissett et al., 2000). Similar findings have been reported in Brazil (Rea et al., 1999), Italy (Cattaneo & Buzzetti, 2001) and Africa (Owoaje et al., 2002). The modest improvements in breastfeeding continuation rates seen in recent years may reflect, in part, the improved support given to breastfeeding women as a result of these initiatives (Dykes & Griffiths, 1998). Indeed, the implementation of the BFHI has been associated with significant increases in breastfeeding initiation and duration rates in maternity hospitals (Prasad & Costello, 1995; Cattaneo & Buzzetti, 2001; Kramer et al., 2001; Philipp et al., 2001; Philipp et al., 2003), and more specifically in neonatal intensive care unit settings (Merewood et al., 2003). Despite these positive influences of the BFHI, other barriers to health professionals providing effective support remain. For example, in a US study of 230 maternity nurses at 20 Midwestern hospitals it was reported that providing breastfeeding support was too time‐consuming, particularly with shortened hospital stays (Patton et al., 1996).

It has been suggested that, in view of the public health importance of breastfeeding, there is a need to develop some form of supplementary support strategy as part of routine health service provision (Sikorski et al., 2003). In recent years, a number of studies have investigated the effectiveness of a variety of breastfeeding support initiatives (e.g. Morrow et al., 1999; Dennis et al., 2002; Alexander et al., 2003; Graffy et al., 2004). In a systematic review of the literature, trials involving lay breastfeeding supporters were shown to have a significant effect in reducing the cessation of exclusive breastfeeding (RR 0.66 [95% CI 0.49, 0.89]; five trials, 2530 women), but the effect on any breastfeeding did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.84 [95% CI 0.69,1.02]; five trials, 2224 women) (Sikorski et al., 2003). However, the results of this review are somewhat ambiguous because of the lack of clarity regarding the term ‘lay’ as it may include both ‘peer’ supporters and ‘voluntary breastfeeding supporters’ (sometimes referred to as ‘breastfeeding counsellors’), terms that in themselves require definition.

There are four voluntary organizations providing support to breastfeeding women in the UK, each with its own particular philosophy and aims. These are the Association of Breastfeeding Mothers, the Breastfeeding Network (BfN), La Leche League and the National Childbirth Trust. One of the main differences between these voluntary organizations and peer supporters relates to the amount of training they receive. Peer supporters commonly receive approximately 20–30 hours of education, whereas voluntary breastfeeding supporters/counsellors receive 1–2 years of intensive education. The term ‘voluntary breastfeeding supporter’ will be used in this study when referring to the BfN supporters.

All BfN supporters are required to have breastfed a baby themselves and complete the programme of education as devised by their training body. The syllabus includes training in breastfeeding support with particular emphasis on listening and counselling skills and working in groups. It aims to increase self‐awareness and provides opportunities for reflection on personal experiences and attitudes. Trainees learn how to work with women both face to face and on the phone. They are assessed with a series of assignments, including a taped role‐play that assesses the ability to listen and use counselling skills naturally and appropriately. When trainees qualify they become BfN registered probationary supporters and for the next year receive supervision and guidance from their tutor as they take up the role of breastfeeding supporter. During this probationary year formal supervision takes place every 6 weeks and informally as required. All BfN registered breastfeeding supporters have ongoing training requirements and regular supervision. They work to a Code of Conduct and abide by their Guidance Document. BfN is a member of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy, committing supporters to following the Ethical Framework for Good Practice in Counselling and Psychotherapy, and is also an associate member of the Telephone Helplines Association working within their Guidelines for Good Practice.

To date the BfN has established 15 breastfeeding support centres across the UK that are coordinated by qualified BfN supporters. In addition the BfN offers the ‘Supporterline’, a telephone service that offers a confidential service to breastfeeding women who want to access a BfN supporter. Women may also request a home visit or discuss their concerns over the phone (Broadfoot et al., 1999).

To our knowledge there are no studies that have conducted a comparative evaluation of the breastfeeding support skills of voluntary breastfeeding supporters and health professionals. The aim of this study was to assess the breastfeeding support skills of midwives and BfN supporters using the prevalidated Breastfeeding Support Skills Tool (BeSST).

Method

Data collection tool

The BeSST is a 30‐item questionnaire (20 open and 10 closed questions examining knowledge and practical skills) based on four video clips. The video clips illustrate the following key aspects of breastfeeding: positioning, attachment, suckling and breast pathology. Each clip lasts between 25 and 90 s. The full details of the validation process of the BeSST are reported in Hall Moran et al. (1999).

Setting

The research was conducted in the north‐west of England between September 2001 and October 2002. Data were collected from midwife participants at their place of work in one UK maternity hospital. The BfN supporters were recruited at three different locations. The first group completed the BeSST at a national conference held by the BfN, a second group participated in a BfN trainer's home and a third group participated in the home of a BfN supporter.

Sample

A power calculation was conducted to determine the required sample size. An effect of 10 points on the BeSST was deemed clinically relevant and using the standard deviation of 9.4, found in previous similar research (Hall Moran et al., 2000), led to the power calculation being based on an effect size of 1.06. To provide 80% power of detecting a significant effect size with a two‐tailed test at P < 0.05, a minimum of 15 participants were required in each group.

Midwife participants

Permission to access midwives and use the hospital setting was obtained from the Head of Midwifery at the participating National Health Service maternity hospital. Prior to commencement, a meeting was held with the Head of Midwifery and key members of staff. The midwives were briefed about the study and made aware that they were under no obligation to take part. Midwives working solely on delivery wards or antenatal wards were excluded from the study because of their limited contact with postnatal women. The midwives who participated in this study worked in teams that crossed the hospital–community interface.

Fifty midwives were selected at random, using a random number table, and invited to participate in the study. Reminder letters were distributed 2 weeks after the initial invitation, after which 15 midwives consented to take part. A letter was sent to the midwives who did not reply to the invitation to ascertain the reasons why they did not wish to take part in the study. Eighteen midwives returned this letter. Reasons given for nonparticipation included: too busy at work (n = 7) or home (n = 4); misplaced the study information (n = 7); off work with long‐term sickness (n = 3); and other reasons, such as bereavement, maternity leave or starting a new job (n = 6).

BfN supporters

BfN supporters were contacted through a BfN trainer. As it was impossible to take a random sample because of the limited numbers of BfN supporters in the north‐west region, a convenience sample of 18 supporters were invited to participate. Of these, 15 gave their consent to take part in the study. The three BfN supporters who did not reply to the invitation to participate in the study were sent a letter to ascertain why they did not respond. One supporter returned the letter, stating that she was too busy at work to participate.

Procedure

Midwives and BfN supporters completed the BeSST in the presence of the researchers. At each sitting, no more than two midwives or seven BfN supporters completed the BeSST at once. This reflected the difficulties the midwives had in making themselves available as a result of on‐ and off‐duty commitments.

Before starting the BeSST, participants were asked to select a precoded paper from an envelope. They were given the BeSST questionnaire and a form requesting demographic data. Participants were instructed to write their code numbers on both forms. This procedure was carried out in the interest of anonymity.

Participants were shown four video clips, each illustrating a different breastfeeding interaction. Each clip was repeated immediately after it was shown. Participants were given 7 min after each repeated clip in which to write their responses. The researcher alerted participants when there was 1 min of writing time remaining to allow them to complete their responses and prepare to view the next clip.

Ethical issues

Midwives and BfN supporters were provided with written information about the study and a consent form to complete if they wished to take part. They were given 2 weeks to decide if they wished to participate. All documentation was kept in a locked filing cabinet in a locked office within the University to ensure confidentiality of data. Midwives and BfN supporters were assured of anonymity at all times and coding was used to achieve this. Ethics approval was granted by the relevant Local Research Ethics Committee and University Departmental Research Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

Differences in BeSST scores between midwives and BfN supporters were tested using an independent samples t‐test (unequal variances estimate). This inferential statistic tests whether the difference between two means (here, the mean scores of midwives and BfN participants), proportional to the standard error of the difference in means, is statistically significant. The unequal variance estimate of t used here corrects for possible differences in the standard deviations of the two samples, and may therefore be considered a more conservative choice. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (version 11.01).

Findings

Sample

The demographic characteristics of the 15 midwives and 15 BfN supporters are illustrated in Table 1. The age range of the two groups was broadly similar and the majority of participants (n = 24) had worked as a midwife or BfN supporter for longer than 2 years. All participants had attended a breastfeeding training course of some description, the most common of which were the BfN training course (n = 15, BfN participants), the 20‐hour WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding Management Course (n = 8, midwife participants) and University run breastfeeding courses (n = 4, midwife participants). BfN participants held a variety of additional roles related to working with mothers and babies. For example, BfN group participants included a midwife, health visitor, general practitioner and nursery nurse, and six others had previous experience of breastfeeding counselling work with other voluntary organizations.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Midwives (n = 15) | BfN supporters (n = 15) | Total (n = 30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | |||

| 20–29 years | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 30–39 years | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| 40–49 years | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| 50–59 years | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Years working as a midwife/BfN supporter | |||

| <2 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 2–5 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| >5 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Other experience working with mothers and babies | |||

| Midwife | 15 | 1 | 16 |

| Health visitor | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| General practitioner | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nursery nurse | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| National Childbirth Trust counsellor | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Stillbirth support | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| None | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Breastfeeding training courses attended | |||

| Hospital in‐service training | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 20‐hour WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding Management Course | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| University breastfeeding module/course | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| BfN training course | 0 | 15 | 15 |

BfN, Breastfeeding Network.

Reliability of the BeSST

Internal reliability

Internal reliability demonstrates that items on the tool are all related to the same underlying construct. The internal reliability of the BeSST for this sample was tested using Cronbach's alpha (Cronbach, 1990). In the validation study, the BeSST demonstrated excellent internal reliability (α = 0.89) (Hall Moran et al., 1999). When tested again using the study sample, alpha remained high at 0.79.

Inter‐rater reliability

Inter‐rater reliability relates to the degree to which two independent observers agreed on the scoring of questions. Two research assistants independently scored the BeSST using a previously validated scoring sheet (Hall Moran et al., 1999). Previous evaluation showed that the BeSST gave good inter‐rater reliability (Hall Moran et al., 2000). This was confirmed in the present study. The inter‐rater reliability of the total scores based on the two scorers was very high (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.96), suggesting that the findings are unlikely to depend on the rater used.

Comparison of midwife and BfN participants

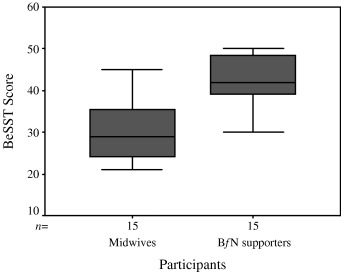

Total scores on the BeSST were significantly higher in the BfN group (mean = 42.5 ± 6.4 SD) than in the midwife group (mean = 30.7 ± 8.2 SD) [t (26.5) = 4.4, P < 0.0001]. The differences between the two groups and the range of scores within groups are best illustrated by a box and whisker plot (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A comparison of Breastfeeding Support Skills Tool (BeSST) scores for midwives and Breastfeeding Network (BfN) supporters. Box represents interquartile range containing 50% of values; whiskers extend from box to highest and lowest value; line across box indicates median value.

Discussion

Scores on the BeSST, which demonstrate breastfeeding support skills, were significantly higher in the BfN group than the midwife group. A previous study, which evaluated the skills of midwives 2 weeks after attending the 20‐hour WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding Management Course, demonstrated that BeSST scores were significantly higher in the postcourse group (mean = 29.9 ± 11.2 SD) than in the precourse group (mean = 19.8 ± 6.7 SD) (P < 0.01) (Hall Moran et al., 2000). It is interesting to note that both midwives and BfN supporters in the present study scored at least as highly as the postcourse sample included in the previous study. Around half the midwives (8 out of 15) in the present study had attended the 20‐hour WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding Management course (as described by Lang & Dykes, 1998) between 1996 and 1997. These findings appear to suggest that the WHO/UNICEF course is effective at improving and sustaining the breastfeeding support skills of midwives. It may also be suggested that the BfN training course is particularly effective at providing supporters with skills necessary to support breastfeeding mothers. These findings may reflect, at least in part, the in‐depth training programme undertaken by the BfN supporters and their specific focus on breastfeeding in contrast to the broader aspects of midwives’ roles.

A qualitative exploration of breastfeeding support needs conducted by the same research group, using Sarafino's support schema (Sarafino, 1994), suggested that breastfeeding mothers need a synergistic combination of emotional, esteem, instrumental, informational and network support, and that these forms of support are most effective when provided within a trusting relationship (Dykes et al., 2003). The BeSST predominantly assesses two components of breastfeeding support skills, i.e. instrumental and informational support. It is clear that the BfN participants possessed high levels of these particular support skills. Further research is underway to assess the emotional and esteem support skills of midwives and BfN supporters. It is likely that voluntary breastfeeding groups, such as the BfN, provide the required ‘network support’ both through their breastfeeding support centres and via the phone, by putting a mother in contact with someone who had been or is a breastfeeding mother.

This research is the first of its kind to assess the specific breastfeeding support skills of a voluntary breastfeeding support group. With the large number of voluntary groups available to support breastfeeding mothers, it is clearly of value to explore their relative effectiveness at providing support, as well as measuring any subsequent effect on breastfeeding rates.

The BeSST has provided a reliable measure of the breastfeeding support skills of midwives and voluntary breastfeeding supporters. The tool underwent a developmental process that generated a pool of questionnaire items and subjected them to a series of rigorous tests for reliability and validity, which resulted in an objective and innovative tool for measuring clinically relevant skills (Hall Moran et al., 1999). It has the advantage of practicability and reproducibility and, in the absence of an alternative method to measure skills, is a useful indicator of the application of knowledge to particular breastfeeding scenarios.

Certain characteristics of the study design and method limit the application of these findings. Most notably, the sample size in this study, although adequate to give a meaningful result, was nevertheless small and cannot be considered truly representative of the diversity of all the midwives and BfN supporters working in the UK. Additionally, in quasi‐experimental designs such as this, there is a potential for bias in the selection of participants. Although a random sample of 50 midwives was taken, only 15 agreed to participate. It may be that only those midwives who had a particular interest in the research and felt confident with their breastfeeding support skills volunteered for the research. This may lead to an overestimation of the skills of the midwives who work at this particular hospital maternity unit.

There is a need for further quantitative research to assess the effectiveness of breastfeeding support skills of other voluntary breastfeeding organizations available to help breastfeeding mothers. This research should be carried out in a variety of settings, particularly in those communities with low breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates. There should be more exploration of the effectiveness of different training programmes used by these groups and the cost‐effectiveness of such programmes. Qualitative research should be conducted to explore different elements of breastfeeding support strategies and the mechanisms by which they operate (Sikorski et al., 2003).

Most importantly, quantitative and qualitative research is urgently required to determine the impact that voluntary breastfeeding organizations, such as the BfN, have on breastfeeding rates and how their assistance is perceived by breastfeeding mothers. Further work should explore the most effective ways in which peer supporters, voluntary breastfeeding supporters/counsellors and health professionals may work in collaboration to provide breastfeeding support. The interagency and interdisciplinary collaborative model is crucial to developing a coherent and cohesive approach to education for those supporting breastfeeding women and to the general support infrastructure for breastfeeding women.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this 1‐year project was received from the UK Government, Department of Health. Additional funds were provided by the University of Central Lancashire. The authors would like to thank the participants who took part in this study and the members of the steering group.

Video footage for the BeSST was supplied by Mark‐It Television Productions and Dr Andrew Spencer, Liz Jones and Anne Woods, authors of the (MATRIX) ‘Breastfeeding’ CD‐ROM.

References

- Alexander J., Anderson T., Grant M., Sanghera J. & Jackson D. (2003) An evaluation of a support group for breast‐feeding women in Salisbury, UK. Midwifery, 19, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. & Geden E. (1991) Nurses’ knowledge of breastfeeding. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 20, 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker E.G. (1992) Breastfeeding knowledge of hospital staff in rural maternity units in Ireland. Journal of Human Lactation, 8, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaix L.W. (2000) Nurses’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural intentions toward support of breastfeeding mothers. Journal of Human Lactation, 16, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadfoot M., Britten J. & Sachs M. (1999) The Breastfeeding Network ‘Supporterline’. British Journal of Midwifery, 7, 320–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrill R., Creedy D. & Cooke M. (2003) Midwives’ knowledge of breastfeeding: an Australian study. Midwifery, 19, 310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo A. & Buzzetti R. (2001) Effect on rates of breast feeding of training for the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. British Medical Journal, 323, 1358–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coreil J., Bryant C., Westover B. & Bailey D. (1995) Health professionals and breastfeeding counselling: client ad provider views. Journal of Human Lactation, 11, 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L.J. (1990) Essentials of Psychological Testing, 5th edn Harper & Row: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C. (2002) Breastfeeding initiation and duration: a 1990–2000 literature review. Journal of Obstetric and Gynecologic Neonatal Nursing, 31, 12–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C., Hodnett E., Gallop R. & Chalmers B. (2002) The effect of peer support on breast‐feeding duration among primiparous women: a randomised controlled trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 166, 21–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwoodie K., Bramwell R., Dykes F., Lang S. & Runcieman A. (2000) The Baby Friendly Breastfeeding Management Course. British Journal of Midwifery, 8, 362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F. & Griffiths H. (1998) Societal influences upon initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. British Journal of Midwifery, 6, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F., Hall Moran V., Burt S. & Edwards J. (2003) Adolescent mothers and breastfeeding: experiences and support needs. An exploratory study. Journal of Human Lactation, 19, 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F. & Williams C. (1999) ‘Falling by the wayside’. A phenomenological exploration of perceived breast milk inadequacy in lactating women. Midwifery, 15, 232–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D.M. & Cullen L. (2003) Post‐natal management and breastfeeding. Current Obstetrics and Gynecology, 13, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Freed G., Clark S., Harris B. & Lowdermilk D. (1996) Methods and outcomes of breastfeeding instruction for nursing students. Journal of Human Lactation, 12, 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffy J., Taylor J., Williams A. & Eldridge S. (2004) Randomised controlled trial of support from volunteer counsellors for mothers considering breast feeding. British Medical Journal, 328, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Moran V., Bramwell R., Dykes F. & Dinwoodie K. (2000) An evaluation of skills acquisition on the WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding course using the pre‐validated Breastfeeding Support Skills Tool (BeSST). Midwifery, 16, 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Moran V., Dinwoodie K., Bramwell R., Dykes F. & Foley P. (1999) The development and validation of the Breastfeeding Support Skills Tool (BeSST). Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 3, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlyn B., Brooker S., Oleinikova K. & Wands S. (2002) Infant Feeding 2000. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Humenick S., Hill P. & Spiegelberg R. (1998) Breastfeeding and health professional encouragement. Journal of Human Lactation, 14, 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S., Chalmers B., Hodnett E.D., et al. (2001) Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomised trial in the Republic of Belarus. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan L., Britto M., Decologon J., Schoettker P., Atherton H. & Kotagal U. (1999) Health system factors contributing to breastfeeding success. Pediatrics, 104, 552–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang S. & Dykes F. (1998) WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative. Educating for success. British Journal of Midwifery, 6, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinski A.C. (1992) Nurses’ knowledge of breastfeeding in a clinical setting. Journal of Human Lactation, 8, 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod D., Pullon S. & Cookson T. (2002) Factors influencing continuation of breastfeeding in a cohort of women. Journal of Human Lactation, 18, 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merewood A., Philipp B.L., Chawla B.A. & Cimo S. (2003) The Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative increases breastfeeding rates in a US neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Human Lactation, 19, 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow A.L., Lourdes Guerrero M., Shults J., et al. (1999) Efficacy of home‐based peer counselling to promote exclusive breastfeeding: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 353, 1226–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owoaje E.T., Oyemade A. & Kolude O.O. (2002) Previous BFHI training and nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding exclusive breastfeeding. African Journal of Medical Science, 31, 137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton C.B., Beaman M., Czar N. & Lewinski C. (1996) The attitudes of nurses toward the promotion of breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation, 12, 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp B.L., Malone K.L., Cimo S. & Merewood A. (2003) Sustained breastfeeding rates at a US Baby‐Friendly Hospital. Pediatrics, 112, e234–e236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp B.L., Merewood A., Miller L.W., et al. (2001) Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative improves breastfeeding initiation rates in a US hospital setting. Pediatrics, 108, 677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad B. & Costello A.M. (1995) Impact and sustainability of a ‘baby friendly’ health education intervention at a district hospital in Bihar, India. British Medical Journal, 310, 621–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea M.F., Venancio S.I., Martines J.C. & Savage F. (1999) Counselling on breastfeeding: assessing knowledge and skills. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 77, 492–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarafino E.P. (1994) Health Psychology. Biopsychosocial Interactions. John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski J., Renfrew M.J., Pindoria S. & Wade A. (2003) Support for breastfeeding mothers (Cochrane Review) In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Update Software: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Wissett L., Dykes F. & Bramwell R. (2000) Evaluating the WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding course. British Journal of Midwifery, 8, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2002) Infant and Young Child Nutrition. Global Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding. Fifty‐Fifth World Health Assembly: Geneva. [Google Scholar]