Abstract

Diet is a key issue for UK health policies, particularly in relation to poorer socio‐economic groups. From a public health perspective, the government's role is to help low‐income families to make healthy food choices, and to create the conditions to enable them to make healthy decisions. Arguably, however, current policy on nutrition and health is influenced by individualist and behavioural perspectives, which fail to take into account the full impact of structural factors on food choices. This paper draws on a systematic review of qualitative studies that prioritize low‐income mothers’ accounts of ‘managing’ in poverty, synthesizing a subset of studies that focus on diet, nutrition and health in poor families. Synthesis findings are explored in the context of dominant discourses concerning individual responsibility for health and gendered societal values concerning ‘good’ mothering. The paper concludes that a shift in emphasis in health policies, affording a higher priority to enabling measures that tackle the underlying determinants of health, would be advantageous in reducing nutritional inequities for low‐income mothers and their children.

Keywords: nutrition, health, low‐income, systematic review

Introduction

The food we eat has an enormous impact on our health. Our vision is of better health for everyone. We are especially concerned to see improvements that will benefit the groups of people who are most at risk from poor health caused by diet, including people on low incomes, pregnant women and children in the early years of life. (Hazel Blears, Public Health Minister, DEFRA News Release, December 12, 2002.)

Poor nutrition, especially amongst families from poorer socio‐economic groups, is of particular concern for public health (Acheson, 1998; Gregory et al., 2000; Henderson et al., 2002; Department of Health, 2004a). An unhealthy diet, defined as one which is high in fat, sugar and salt, and low in fruit and vegetables, can have long‐term negative health consequences, especially for children, and makes a major contribution to health inequalities (Department of Health, 2002). A recent survey by the National Children's Home (2004) found that there had been no substantial improvement in the diets of children in low‐income households since 1991. One‐fifth of the families surveyed said they did not have enough money for food, and more than a quarter of the children never ate green vegetables or salad. The size of the population ‘at risk’ of poor nutrition remains substantial. Despite a considerable reduction in child poverty levels since 1997, in 2002/2003 some 28% of children lived in low‐income households (using a threshold of 60% of median household income after housing costs) (Department for Work and Pensions, 2004).

The UK government has introduced numerous initiatives aimed at improving diets in poor households and encouraging ‘healthy choices’ of food. From a public health perspective, the government's role is to help people ‘make informed decisions within health friendly environments’ (Department of Health, 2004b, p. 7). But evidence suggests that interventions aimed at modifying behaviour are generally less effective amongst lower socio‐economic groups who are their prime target (Lynch, 1996; Emmons, 2000). Furthermore, research has identified barriers to a healthy diet for those on low income, including affordability and access to fresh food (Lobstein, 1997; National Children's Home, 2004). Policy documents acknowledge constraints on low‐income families’ food choices, for example ‘food deserts’ (that is restricted access to good quality foodstuffs in poor areas) and high prices for fresh fruit and vegetables in deprived districts (Department of Health, 1996, , 1999). However, this apparent government acceptance of structural limitations on ‘choice’ for poor families is set alongside the perceived need for individuals to take responsibility for their own health.

The prime responsibility for improving the health of the public does not rest with the NHS nor with the Government, but with the public themselves. (John Reid, Secretary of State for Health, 3 February 2004, Department of Health, 2004b, p. 7)

Individualist approaches to social inequalities in health stress the effects of ‘risky’ and health damaging behaviours, such as eating an ‘unhealthy’ diet, on the health of lower socio‐economic groups (cf. Whitehead, 1988 and Townsend, 1990 for a discussion). However, as long ago as 1980, the Black Report made a convincing case for the primary role of material deprivation in determining health differences between social classes (Townsend & Davidson, 1982). More recently, the Acheson Inquiry (1998) reached similar conclusions.

Following a wide‐ranging consultation, a public health white paper entitled Choosing Health: Making Healthier Choices Easier was published recently (Department of Health, 2004c). This document emphasizes the benefits of achieving a society more fully engaged in protecting and promoting personal health. Similarly, Derek Wanless's (2004) second report for the Treasury, Securing Good Health for the Whole Population, argues that:

Individuals are ultimately responsible for their own and their children's health and it is the aggregate actions of individuals, which will ultimately be responsible for whether or not such an optimistic scenario as ‘fully engaged’ unfolds. (Wanless, 2004, Summary, p. 4)

The Wanless report notes a tendency for lower‐income groups to discount future health benefits from behavioural change (in other words, living for the moment), coupled with failures in ‘social context’, that is negative influences on health in the family and social environment. It acknowledges the direct impact of income inequalities on the material resources (including time constraints) available to individuals to protect health. Furthermore, the report stresses the role of government and other stakeholders in supporting the context for individual change. Brief mention is made of interventions to tackle market failure and promote greater equity in society, although no detailed proposals are provided. The ideology underpinning the report is primarily one of free choice and behavioural responsibility, therefore (Lynch et al., 1997), an approach which downplays the influence of social and economic circumstances on poorer groups (Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999; Kneipp & Drevdahl, 2003).

Following Kneipp and Drevdahl (2003), this paper will argue that if health policies are to be effective they must take full account of the ‘socio‐political backdrop that shapes life circumstances’ (p. 167). Gender is central to the discussion, as it is women who are the primary ‘managers of poverty’ within households (Hanmer & Hearn, 1999, p. 119); moreover, the majority of the studies included in this review focus for the most part on low‐income mothers. There is a rich vein of research on how individual responsibility for providing ‘healthy choices’ of food for children is experienced by mothers in poor families. As yet, this is largely untapped. The qualitative systematic review described in this paper provided a vehicle for exploring this research and identifying recurring concepts across studies that characterize women's experiences. While the systematic review took a broad approach to the topic of parenting in disadvantage, the process of cross‐study comparison identified food and nutrition as important facets of ‘managing’ poverty for low‐income mothers. The evidence in this paper is therefore drawn from a subset of studies, which explore the ways in which mothers’ coping strategies in poverty shape the place of food in households. The paper also highlights the particular challenges faced by low‐income lone mothers.

Research design

Systematic review methods were used to locate, critically appraise and synthesize qualitative studies undertaken in the UK since 1987, which prioritized low‐income mothers’ accounts of parenting in poverty. The advantage of carrying out a systematic review, in comparison with a traditional literature review, is that systematic reviews use explicit criteria to locate, appraise and synthesize studies (Petticrew, 2001; Hawker et al., 2002). Reviews of primary research can be used to produce a map of the ‘bigger picture’, to facilitate understanding of a topic, identify common threads across studies or develop theory (Kearney, 2001; Hammersley, 2002).

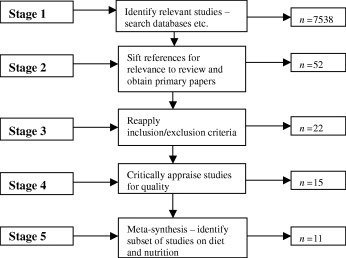

The systematic review protocol broadly followed the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2001) guidelines. The main stages of the review are outlined in Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1.

Main of the systematic review process.

In stage 1 of the review, literature was sought through a mixture of electronic database searching, contacts with experts, website and citation searching. Drawing on earlier experience of locating qualitative studies, a limited number of databases were searched, with particular emphasis placed on contacts with key informants and citation searching. At stage 2, titles and abstracts were sifted for relevance to the research questions and ‘fit’ with the inclusion criteria for the review. Two experienced researchers double‐checked 500 references (7% of total) for relevance, with a high level of agreement. Primary papers were then obtained and further scrutinized against the inclusion criteria (stage 3).

Studies were then appraised for quality (stage 4), using a checklist based on earlier models of assessing qualitative research (Popay et al., 1998; Seale, 1999; Mays & Pope, 2000; NHS CASP, 2001; Spencer et al., 2003). This was divided into 10 main sections – research background, aims and objectives, study context, appropriateness of design, sampling, data collection, data analysis, reflexivity, contribution to knowledge and research ethics – with specific questions asked of studies in each section. Two experienced qualitative researchers graded the studies for quality on a scale from A to D, initially independently, then meeting for discussion. Studies graded A to C were included in the main meta‐synthesis; those graded D were excluded. In the initial stage of the analysis, studies graded A and B were scrutinized to identify the main ideas, concepts and interpretations. When an analytical framework was established, data from grade C studies were introduced, to flesh out the conceptual categories. The evidence presented in this paper therefore is based only on research where there is a high level of confidence attached to the findings.

A meta‐synthesis of data was then carried out (stage 5) (cf. Britten et al., 2002; Arai et al., 2003; Campbell et al., 2003; Harden et al., 2003). The term meta‐synthesis is used in its broadest sense to represent ‘a family of methodological approaches to developing new knowledge based on rigorous analysis of existing qualitative research findings’ (Thorne et al., 2004, p. 1343). Noblit and Hare's (1988) guidelines for conducting a meta‐ethnographic synthesis were used to structure the analysis. Meta‐ethnography provides an alternative to aggregative methods of synthesizing qualitative research, in which authors’ interpretations and explanations of primary data are treated as data and are translated across several studies (Britten et al., 2002; Campbell et al., 2003). The analytic steps carried out were as follows:

-

1

Reading the studies – checking for relevant metaphors, ideas, concepts and interpretations.

-

2

Identifying the relationship between studies, using lists of key metaphors, ideas and concepts arranged in matrix form.

-

3

Interpretation and translation – that is, assessing whether some concepts, metaphors and interpretations are able to encompass those of other accounts (while maintaining the integrity of individual studies).

-

4

Writing the synthesis.

(Adapted and simplified from McCormick et al., 2003, p. 939).

The process of translation entails ‘examining the key concepts in relation to others in the original study, and across studies, and is analagous to the method of constant comparison used in qualitative data analysis’ (Campbell et al., 2003, p. 673). Although the method is described in linear terms, in practice it consists of a series of overlapping stages of reading and rereading, comparing similarities and differences across studies, interpreting, recording and synthesizing findings (McCormick et al., 2003). It was at this interpretive stage of the review that diet and nutrition emerged as key themes. The evidence in this paper is therefore drawn from the following subset of studies that address the topic of food in poor families (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies included in the systematic review

| Name of study | Aims | Methods | Sample | Main topics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bostock (1998) | To provide a comprehensive picture of caring for children in poverty | Semi‐structured interviews, 24 h diaries | 30 lone and partnered mothers with pre‐school children, on low income. Majority in receipt Income Support (IS). | Nature of caring (routine); household finances; social relationships in disadvantaged circumstances; mothers’ health. |

| Cohen et al. (1991; 1992) | To consider the effects of social security benefits for people living on IS | Interviews | 45 IS claimants (single parents and couples with children) (38 reinterviews) | Quality of life; dealings with social services; community organizations; budgeting on benefit; well‐being; effect of lack of money on family relationships. |

| Dearlove (1999) | To explore women's perceptions and experiences as lone mothers in receipt of IS, and what ‘support’ means to them as carers of pre‐school children. | Focus groups; in‐depth interviews | Focus groups – 33 women; 37 interviews. Lone mothers – living alone with pre‐school child. | Differences in level of resources available to lone mothers – material, childcare, social. |

| Dobson et al. (1994) | To focus on the food related ideas, preferences, priorities and choices of those experiencing poverty. | Semi‐structured interviews, focus groups, food consumption diaries. | 48 households: lone parents and couples, new and long‐term claimants IS | Purchasing patterns; food consumption patterns; coping and managing; food information; factors which influence food priorities |

| Ghate and Hazel (2002) | To explore parents’ perceptions of life in a poor environment | Survey and in‐depth interviews | 40 parents (9 ‘index situation’ groups) | Social support – informal, semiformal, formal; stress factors – individual, family, community and neighbourhood; coping/not coping – safety, accommodation, financial (budgeting), behavioural. |

| Graham (1985, 1987) | To understand how lone mothers experience and seek to contain their poverty. To explore informal health care in households with pre‐school children. | Interviews, diaries, self‐administered questionnaires | 102 families (38 one‐parent; 64 two‐ parent) with pre‐school child. Low and average income. | Organization of money; feeding the family; family networks (support); friendship networks; coping with caring (smoking); caring for family health. |

| Kempson et al. (1994) | To explore families’ managing strategies on low income. | Interviews | 74 families with children living on low incomes (receiving IS or Family credit, or on margins of eligibility for Family Credit). | Maximizing income; budget management; consumer credit; making ends meet. |

| Malseed (1990) | To understand, in partnership with families on low incomes, the mechanisms underlying social inequalities in food consumption. | Interviews | 15 families with children living on SB (later IS) (16 affluent families –‘control’) | Social inequalities in food consumption; domestic budget management and household food intake; food availability and accessibility; myths about low income group spending; cultural perspectives. |

| McKendrick et al. (2003) | To explore the views and experiences of people living in poverty, perceptions of the causes and effects of poverty, responses and approaches to managing poverty | Focus groups | 18 groups – 99 participants: experience of work; demographic characteristics; experience of poverty (duration and intensity); minority status; geographical location; family background. | Nature of low‐income living with respect to shortage, management and stress; meeting children's needs; changes in circumstances and status; attempts to maintain quality of life. Hidden costs and support; debt. |

| Owens (1997) | To survey women on low incomes to find out what are the key factors working against their efforts to give children a healthy balanced diet. | Interviews | 45 women on low income | Price of poverty; social and cultural pressures; making ends meet; barriers to healthy eating; expenses of poverty; buying food on benefits; the transport trap; debt. |

| Ritchie (1990) | To research the living standards of unemployed people and their families. | In‐depth interviews | 30 unemployed male householders with families; 26 partners (22 males reinterviewed and 14 partners) | Employment histories; concept of ‘living standards’; changes in living standards; patterns of management; adaptations in expenditure; the use of other resources; psychological and social consequences. |

The synthesized studies range across different family structures, family size, geographical areas and ethnic groups, although the majority of women are drawn from the white population. In those samples that are ethnically diverse, however, there are striking similarities in women's accounts of caring for children in poverty. A particular strength of meta‐ethnographic methods is that the process of comparing concepts and interpretations across a number of studies enables researchers to produce a more detailed explanation of a phenomenon than any individual study (Suri, 1999; Finfgeld, 2003; Varcoe et al., 2003).

Results of the systematic review

Exploring the similarities in women's accounts across studies identified three overarching concepts concerning low‐income mothers’‘management’ of poverty that exert an influence on diet and nutrition: strategic adjustment, resigned adjustment and maternal sacrifice. The first concept, ‘strategic adjustment’, appears in McKendrick et al.'s (2003) study of low‐income families in Scotland, in the context of families’ adaptation to impoverished circumstances. The term captures a related set of concepts and metaphors explicit or implicit in other studies, relating to material strategies adopted by mothers in coping with poverty. ‘Resigned adjustment’, the second concept explored in this paper, refers to the ways in which, over time, ‘managing’ poverty and the lifestyle changes this entails can become routine for low‐income mothers. However, women's coping strategies in poor circumstances are also affected by social and cultural values concerning what constitutes ‘good’ mothering, in other words, what discourses they draw upon to make sense of their situations (Duncan & Edwards, 1999). The final concept, ‘maternal sacrifice’, encompasses those aspects of women's accounts relating to social ideals of the ‘good mother’, and how these shape diet and nutrition in low‐income families.

Strategic adjustment to poverty

‘Strategic adjustment’ serves as a starting point to explore mothers’ management of low income in poor households, in particular as it shapes families’ food consumption. The concept implies an element of choice in the control of household resources. For example, mothers in the majority of synthesized studies ‘strategically adjusted’ to poverty by prioritizing the purchase of collective necessities, such as food, rent and fuel (Graham, 1987; Cohen et al., 1992; Kempson et al., 1994; L. Bostock, unpublished PhD thesis; McKendrick et al., 2003). Many ‘juggled’ bills to pay the most urgent first (Malseed, 1990; Dobson et al., 1994; Kempson et al., 1994; J.P. Dearlove, unpublished PhD thesis; Ghate & Hazel, 2002). The following examples illustrate the complexity of this period of ‘adjustment’ for families.

I don’t pay nothing until I’ve got food in ma press [cupboard]. I don’t care if ah’ve got nae money left to pay debt or anything. Nothing gets paid until ma messages [food items] are bought, not a damn thing . . . no’ even Council Tax gets paid unless my messages are in the hoose. Ah even make sure I’ve got gas and electric. Nae money left efter that, though! (Focus group participant from peripheral housing estate, small de‐industrialising town in rural area) (McKendrick et al., 2003, p. 12)

But it's just with bills to pay, the gas bill, you know, I pay about 10 pounds per week, and I try and save the telephone stamps each week. I buy two each week, so that's four pounds. Then there's the electric to buy each week, we have the cards to put them in the meter . . . water rates each week and that's before I’ve even thought about food. So that's twenty, 25 pounds gone before I’ve even bought food. (Long‐term Income Support, lone parent, one child) (Dobson et al., 1994, p. 23)

While some low‐income mothers prioritized buying food, for others it was a part of the budget where spending was flexible and cutbacks could be made. For many, debt repayments made ‘juggling’ their finances more complex (Malseed, 1990; Owens, 1997; L. Bostock, unpublished PhD thesis; Ghate & Hazel, 2002). Parents borrowed both to fulfil basic needs and to enable them to participate in special occasions. For Asian families in one study, for example, food was often bought from local shops ‘on tick’[credit] (Cohen et al., 1992). Typically, mail order catalogues were used to spread the costs of clothes and household items (Ritchie, 1990; Cohen et al., 1992; Dobson et al., 1994).

Linked to the concept of strategic adjustment is Kempson et al.'s (1994) concept of ‘minimizing expenditure by resourceful purchasing’, for example by restricting spending on certain foodstuffs. For some mothers this could mean cutting back on the purchase of ‘healthy’ foods such as fruit and vegetables.

My son likes expensive things like oranges and grapefruit, and I just can’t afford them very often. (Mother in low‐income household) (Kempson et al., 1994, p. 107)

You see people with trolleys, throwing things in, and there I am with my basket hunting for all the cheapest things. (parent, subsistence group) (Malseed, 1990, p. 33)

Dobson et al.'s (1994) research indicates that lone parent and couple families use food priorities and choices as one way of adapting to the ‘discipline of poverty’. Mothers in this study aspired to provide ‘mainstream diets’ and ‘proper meals’ for their children, rather than snacks or ‘quick and cheap’ meals. However, the constraints of low income meant that this was not always possible.

We try to eat ‘proper meals’ like meat and veg. and that but there just isn’t the money to do it all the time. So we eat properly maybe once or twice a week depending on the money and the rest of the time we make do with things like sausages, pies, potatoes and things like beans. The meals aren’t as good but they do the job, they’ll fill them [children] up and stop them from being hungry, it's the best I can do. (Long‐term Income Support recipient, couple, more than one child) (Dobson et al., 1994, p. 17)

Similarly,

I used to cook a big evening meal every night. Now I get slices of bread to cover breakfast and sandwiches, almost exactly. I budget to the last slice of bread now. (Lone mother living on a low income) (Graham, 1987, p. 71)

‘Focused shopping’ was another way in which families in McKendrick and colleagues’ study minimized household expenditure; typically this meant buying a week's food in advance, to avoid impulse purchases (cf. Owens, 1997; McKendrick et al., 2003).

You get your money and make a shopping list of everything we’re going to eat between that day and the next day you get money. You go to the shop and you buy all that. (Focus group participant, peripheral housing estate, large rural town) (McKendrick et al., 2003, p. 12)

However, ‘shopping around’ for the best food bargains was a more common means of eking out household budgets (Graham, 1987; Ritchie, 1990; Cohen et al., 1992; Dobson et al., 1994; Ghate & Hazel, 2002; McKendrick et al., 2003). For mothers, this usually meant expending time and effort, searching for cheaper goods than were available in their local areas. For example:

I get the Asda cornflakes because they’re quite cheap and I get the big 750 gram [packet] . . . and I get my milk from down there. I’m always looking around for bargains, because you can’t always afford the expensive stuff. You have to go around and look . . . (Mother, bad accommodation, low income, poor health) (Ghate & Hazel, 2002, p. 209)

Across the synthesized studies, lone mothers’ opportunities to manage poverty differed somewhat from those of women in couple families. Typically, as the sole adult in a household, they were able to exert a greater degree of control over both household finances and their diet. In Graham's (1987) study, for example, over half the lone mothers regarded themselves as financially better off living independently than living with a partner. Their opportunities to ‘strategically adjust’ to the stringencies of low‐income living, such as cutting back on food save money, were therefore increased. This could be an advantage, in terms of increased independence, but also a potential cost to health. Dobson et al. (1994) found, for example, that lone mothers were less likely to cook ‘proper’ meals for themselves.

. . . very rarely do I cook a ‘proper meal’. I’ll cook a ‘proper meal’ on Sundays and probably Saturdays, but the rest of the time, he [child] just snacks and then . . . he’ll have a pizza . . . I live on toast. I don’t go in for fancy meals, they are a waste of time and money . . . (Income Support recipient, lone parent, one child) (Dobson et al., 1994, p. 18)

A significant minority of lone mothers in Dobson and colleagues’ study had lost interest in food; the stress involved in coping on a restricted budget meant that it was no longer a source of pleasure. Graham (1987) and Cohen et al. (1992) found that lone mothers had the poorest diets, both in terms of quality and quantity. Although lone parenthood allows women greater flexibility in strategically adjusting to and managing poverty, this takes place in the context of material constraint, and may undermine maternal health.

Resigned adjustment to poverty

Next, we turn to McKendrick et al.'s (2003) concept of ‘resigned adjustment’, which relates to both material and psychological aspects of life in low‐income households. This concept is characterized by a sense that, over time, poor families must adjust to prevailing circumstances, in the absence of realistic alternatives. Ritchie (1990) suggests that there is an ‘adaptation period’ of adjustment to poverty that some households negotiate (although families’ circumstances and reactions to them may fluctuate). In time, further lifestyle changes become impractical or impossible. Dobson et al. (1994) study found that modification to purchasing and consumption patterns in low‐income families eventually became a ‘taken for granted’ part of life; for example:

You get used to watching what you spend and thinking to yourself, can I buy that cheaper from somewhere else, it gets to the point where you don’t realise that you’re doing it anymore. (Long‐term Income Support recipient, lone parent, more than one child) (Dobson et al., 1994, p. 24)

Similarly, Graham (1987) suggests that economizing can become a ‘way of life’ for mothers in poverty, especially if the experience is prolonged, while Ghate & Hazel (2002) describe parents in disadvantaged circumstances facing up to household poverty as a reality they ‘just had to deal with’ (p. 210).

You get a bill, you just deal with things. It might be hard, and I know I’m in debt and I’ve got catalogues, but you just deal with it. There's nothing I’d like more than for me to say [to the children], ‘Right, I’ll give you better things . . . and (let) you know a better life’. But that’ll never happen. (Mother, lone parent, difficult child, low income) (Ghate & Hazel, 2002, p. 210)

Over time, the psychological impact of poverty became increasingly apparent. For example, a number of mothers in Malseed's (1990) study perceived their situations as hopeless. For example:

It's the whole psychological thing. We’ve got no reason to bother, to save or anything, because we know things won’t change. You begin not to expect anything. You live from day to day. (Mother, subsistence group) (Malseed, 1990, p. 35)

Across studies, the concepts of strategic and resigned adjustment are interpreted as ways of surviving poverty, rather than as means of escaping impoverished circumstances. However, such strategies may entail health costs for the individual, both physically and emotionally. As this paper goes on to demonstrate, ‘managing’ poverty for low‐income mothers (especially lone mothers) can mean compromising their own nutritional needs for those of their children.

Maternal sacrifice: the ‘good’ mother

The concept of ‘maternal sacrifice’ appears in various guises in the synthesized studies – suggesting that mothers frequently prioritized their children's needs over their own. Self‐denial for women on low‐income, according to Dobson et al. (1994), can be seen as the ‘price’ of successful mothering. This idea recurs across studies, for example:

Participant 1: There is always this odd thing you know you really want to get your kid. You know you really can’t afford it. You end up starving for a week but oh you are going to get it anyway.

Participant 2: You give up a load of home comforts really. So even if you just had a load of indulgent stuff for like your bath or just a nice long soak you give all of that up. I think mums generally give up anything so that their child would have everything. (Young adults, rural town in northern Scotland) (McKendrick et al., 2003, pp. 17–18)

Although maternal sacrifice cuts across all aspects of providing for children, food consumption is the area where hardship is most keenly felt. Because, in the main, it is women who organize shopping and cooking within households, it is relatively simple for them to prioritize their children's food intake at the expense of their own. Women's accounts illustrate that going without food or ‘making do’ in order to feed children was common (Malseed, 1990; Owen, 1997; J.P. Dearlove, unpublished PhD thesis). Indeed, mothers sometimes felt it was their duty to go without to protect their children (Cohen et al., 1992). In Kempson et al.'s (1994) research with low‐income families, for example, it was mothers who sacrificed their own food intake to protect their children.

I don’t cut down, as I say, with the kids. I try to make sure they get, but like I cook a meal and as long as there's plenty for them, I make do with a piece of toast. (Low‐income mother) (Kempson et al., 1994, p. 283)

Graham (1985) also describes how women practised ‘individualized consumption’ within families; it was children's needs that came first, if money was tight. For example:

Oh yes, I cut down myself. Sometimes if we’re running out the back end of the second week and there's not really a lot for us to eat, I’ll sort of give the kids it first and then see what's left, and we’ll have what's left. (Mother in low income, two‐parent family) (Graham, 1985, p. 144)

For a number of lone mothers, an awareness of the negative and stigmatizing discourses around lone motherhood (cf. Roseneil & Mann, 1996; Silva, 1996; Duncan & Edwards, 1999) meant that being seen to put their children's welfare first was particularly important. Dearlove (1999) explains, for example, that low‐income lone mothers attempted to have children who were ‘not poor’, often at the expense of their own needs.

. . . I don’t buy nothing for myself any more. It's a luxury to buy myself something . . . it's all for [son] now. (Collette, lone mother, two children aged under 3) (J.P. Dearlove, unpublished PhD thesis, p. 202)

Dearlove (1999) interprets this desire on the part of lone mothers to be seen to be managing, despite impoverishment, as ‘a faultline in women's understanding of inadequacy’; in other words, they blamed themselves rather than any shortcomings in welfare support, if they struggled to provide for their children. Lone mothers in her study were anxious to demonstrate that they could be ‘good’ mothers. For many low‐income women, an inability to provide adequate nutrition for their children struck at the core of their perceived responsibilities, as a lone parent in another study explained:

I just get the kids together and say, well, I’m sorry, but this has happened, I’m afraid there’ll be no dinners this week. I try to supplement it [sandwiches] with soup or something to make it more like a meal. But there again, you see, I’m sort of getting used to doing that now, but I still feel, God, you know, I’m not fulfilling my role as a mother properly here. (lone parent) (Cohen, 1991, p. 31)

Discussion

This systematic review illustrates the ways in which disadvantaged mothers ‘manage’ poverty, strategically adjusting to living on low income by adopting a number of coping strategies. Lone mothers’ ability to ‘manage’ poverty is further influenced by having sole responsibility for their children's well‐being: typically they enjoy no second income to cushion financial hardship, nor do they have a partner on hand to share child care responsibilities. Their accounts highlight the additional control that they are able to exercise over household resources, but situate this within a context of scarcity. Moreover, they suggest that lone mothers attempt to maximize their children's welfare in a moral atmosphere that lays the blame for any shortcomings in behaviour and lifestyle firmly at the door of the individual. While the concept of strategic adjustment implies a degree of choice, it is choice experienced within externally imposed limitations, which restricts its utility for poor mothers. Over time, the constraints associated with poverty, such as cutting back and making do, can become second nature, despite potential costs to physical and emotional well‐being.

This review also emphasizes the moral dimensions of ‘managing’ in poverty, reflected in societal values concerning mothering, and demonstrated by the centrality to women's accounts of providing adequate, nutritional food for their children. In the context of poverty, their self‐worth as mothers is often expressed through their ability to maintain ‘mainstream’ diets for their children, despite costs to their personal health and well‐being. McKeever & Miller (2004) argue that children who are physically healthy can be seen as evidence of the efficacy of their upbringing, and thus as a source of ‘symbolic capital’ for mothers (Bourdieu, 1984). For poor women, whose alternative sources of capital and ways of legitimizing their roles in society are few, this is especially important.

There are certain limitations to this systematic review which limit its generalizability; for example, studies draw on different populations, such as Income Support recipients, women on low income, unemployed families and those with varied experiences of poverty, in different social contexts, making comparative analysis problematic. Although the majority of studies include two‐parent and lone parent families, some authors fail to differentiate between family types in their analyses. It is often difficult therefore to identify similarities and differences between parents living in diverse family circumstances. Nor is it always possible to relate aspects of mothers’ accounts directly to low‐income or family structure. As Margaret Kearney cautions, the conditionality and partiality of small‐study qualitative findings should be acknowledged and care should be taken in generalizing from research undertaken in unique contexts (Thorne et al., 2004). Some commentators suggest that combining the findings from qualitative studies that use different epistemological, philosophical and methodological approaches runs contrary to the fundamentally interpretive and contextual nature of qualitative inquiry (Estabrooks et al., 1994; Jensen & Allen, 1996; Sandelowski et al., 1997; Dixon‐Woods et al., 2001; Morse, 2001). Arguably, however, decisions to include studies in syntheses are most usefully based on their relevance to research questions rather than identical methodological perspectives (Booth, 2001; Doyle, 2003). Moreover, some researchers advocate synthesizing findings from diverse but complementary theoretical traditions as a means of enhancing the credibility of reviews and enriching analyses (Knafl & Breitmayer, 1991; Field & Marck, 1994; Finfgeld, 2003).

Much of the synthesized research is silent (or muted) on the subject of gender. While a number of studies include male respondents (e.g. Ritchie, 1990), there is little analysis of the ways in which disadvantage impacts differently on men and women; parenting on low income is largely presented as gender‐neutral. This is in contrast to feminist research that focuses on women in couple families, or lone mothers (Graham, 1987; L. Bostock, unpublished PhD thesis; J.P. Dearlove, unpublished PhD thesis), in which the gendered social organization of child care is a key factor. Lone fathers’ accounts of parenting are particularly lacking. Gender‐sensitive research with low‐income lone parents of both genders is therefore needed to fill this gap in the evidence base.

Conclusions

This systematic review has identified some of the ways in which low‐income mothers attempt to ‘manage’ poverty, and the potential effects on their health and, in particular, their nutritional needs. A survey of public attitudes to public health policy, commissioned by the King's Fund (with support from the Health Development Agency and the Department of Health), found that the majority of people agree that individuals are responsible for their own health and that of their families (King's Fund, 2004). However, over 40% of the sample surveyed also said that there are too many factors beyond the control of the individual to hold them wholly responsible for their health. Other commentators have noted that research on public attitudes to health tends to produce individualized responses rather than structural explanations, because health is seen as central to social identity.

In the face of the moral imperative in Western society to be healthy, however, it is understandable that it is those who are most exposed to ‘unequal’ health who will be least likely to talk readily about their risk status . . . taking responsibility for ‘health’ . . . is accounting for one's social identity. (Blaxter, quoted in Bolam et al., 2004, p. 1357)

The King's Fund survey found social class differences in attitudes to health. Notably, a higher proportion of people in socio‐economic groups D and E said that health was beyond individual control, while those in higher socio‐economic groups were more likely to embrace the notion of lifestyle changes to protect health (King's Fund, 2004). These findings support Cockerham et al.'s (1997) theory that ideas about ‘healthy lifestyles’ and the need to exert personal control over one's health are fundamentally middle class concepts. Drawing on Bourdieu & Wacquant (1992), they argue that lifestyle choices are not merely constrained but shaped by life chances. For the poor, therefore:

Unrealistic choices are not likely to be achieved or maintained. Realistic choices are based on what is (structurally) possible and are more likely to be operationalised, made routine, and can be changed when circumstances permit. (Cockerham et al., 1997, p. 325)

Whitehead (1988) suggests that while materialist and individual/behavioural approaches to explaining health inequalities both offer partial explanations for health inequalities between social classes, these are interrelated, rather than mutually exclusive. Thus parents in poor circumstances are able to make choices, but their environment, available income and other variables affect these choices. For example:

Diet is profoundly influenced by cultural and local social customs, informal and formal education, the availability as well as the price of goods in local markets, advertising, recipes and fashions recommended by the media, and decisions taken by farmers and the manufacturers of food products as well as by government. (Townsend, 1990, p. 383)

Therefore, interventions that aim to encourage individual changes in lifestyle must also be multifaceted and include measures to improve families’ socio‐economic circumstances. The authors of the King's Fund report (2004) offer a useful distinction between initiatives that encourage individual change in health practices, such as the provision of advice about health risks, and those which enable, for example, through structural interventions that tackle wider economic, social and environmental disadvantage. This systematic review suggests that low‐income mothers’ efforts to ‘manage’ poverty are contradictory in their effects on health. A shift in emphasis in health policy therefore affording a higher priority to enabling measures that tackle the underlying determinants of health would be advantageous for reducing nutritional inequities for low‐income mothers and their children.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Department of Health National Co‐ordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development, postdoctoral training fellowship number RDO/35/21. I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Hilary Graham of Lancaster University, Professor Margaret Whitehead of Liverpool University, and my coresearch fellow Beth Milton of Liverpool University, for their support and advice. I would also like to acknowledge members of my research advisory group at Lancaster University, for their help in discussing methodological and conceptual issues associated with this paper.

References

- Acheson D. (1998) Independent Inquiry Into Inequalities in Health Report. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Arai K., Popay J., Roen K. & Roberts H. (2003) Preventing Accidents in Children – How Can We Improve Our Understanding of What Really Works? Exploring Methodological and Practical Issues in the Systematic Review of Factors Affecting the Implementation of Child Prevention Initiatives. Health Development Agency: London. [Google Scholar]

- Bolam B., Murphy S. & Gleeson K. (2004) Individualisation and inequalities in health: a qualitative study of class identity and health. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 1355–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A. (2001) Cochrane or Cock‐eyed? How Should We Conduct Systematic Reviews of Qualitative Research? Paper presented at the Qualitative Evidence‐based Practice Conference. Taking a Critical Stance. Coventry University, 14–16 May 2001.

- Bourdieu P. (1984) Translated by Richard Nice Distinction. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. & Wacquant L.J.D. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. University of Chicago Press: Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Britten N., Campbell R., Pope C., Donovan J. & Morgan M. (2002) Using meta ethnography to synthesis qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of Health Service Research and Policy, 7, 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Pound P., Pope C., Britten N., Pill R., Morgan M. et al. (2003) Evaluating meta‐ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham W.C., Rutten A. & Abel T. (1997) Conceptualizing contemporary health lifestyles: moving beyond Weber. Sociological Quarterly, 38, 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R. (1991) If you have everything secondhand, you feel secondhand: bringing up children on income support. FSU Quarterly, 46, 25– 41. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R., Coxall J., Craig G. & Sadiq‐Sangster A. (1992) Hardship Britain: Being Poor in the 1990s. Child Poverty Action Group: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Work and Pensions . (2004) Households below average income, 2002/03. Department of Work and Pensions: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (1996) Low Income, Food, Nutrition and Health: Report from the Nutrition Task Force. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (1999) Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2002) Five‐a‐day Community Pilot Initiatives: Key Findings. Department of Health: London. Available at: http://www.doh.gov.uk/fiveaday [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2004a) Choosing Health? Choosing a Better Diet. A Consultation on Priorities for Food and Health Action Plan. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2004b) Choosing Health? Resource Pack. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2004c) Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. Department of Health: London. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon‐Woods M., Fitzpatrick R. & Roberts K. (2001) Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: opportunities and problems. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 7, 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson B., Beardsworth A., Keil T. & Walker R. (1994) Diet, Choice and Poverty. Family Policy Studies Centre: London. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L.H. (2003) Synthesis through meta‐ethnography: paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qualitative Research, 3, 321–344. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S. & Edwards R. (1999) Lone Mothers, Paid Work and Gendered Moral Rationalities. Macmillan: Basingstoke. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K.M. (2000) Health behaviours in a social context In: Social Epidemiology (eds Berkman & L.F. I. Kawachi), pp. 242–266. Oxford University Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks C.A., Field P.A. & Morse J.M. (1994) Aggregating qualitative findings: an approach to theory development. Qualitative Health Research, 4, 503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Field P.A. & Marck P.B. (1994) Uncertain Motherhood: Negotiating the Risks of the Childbearing Years. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld D. (2003) Metasynthesis: the state of the art – so far. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghate D. & Hazel N. (2002) Parenting in Poor Environments: Stress and Coping. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London. [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. (1985) Caring for the Family: the Report of a Study of the Organization of Health Resources and Responsibilities in 102 Families with Pre‐school Children. Health Education Council: London. [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. (1987) Being poor: perceptions and coping strategies of lone mothers In: Give and Take in Families: Studies in Resource Distribution (eds Brannen & J. G. Wilson), pp. 56–74. Allen & Unwin: London. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory J., Lowe S., Bates C.J., Prentice A., Jackson L.V., Smithers G. et al. (2000) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Young People Aged 4 to 18 Years. Vol. 1: Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M. (2002) Systematic or Unsystematic, Is That the Question? Some Reflections on the Science, Art, and Politics or Reviewing Research Evidence. Talk given to the Public Health Steering Group of the Health Development Agency, October 2002.

- Hanmer J. & Hearn J. (1999) Gender and welfare research In: Welfare Research: A Critical Review (eds Williams F., Popay & J. A. Oakley), pp. 106–130. UCL Press Ltd: London. [Google Scholar]

- Harden A., Oliver S., Rees R., Shepherd J., Brunton G., Garcia J. et al. (2003) A New Framework for Synthesising the Findings of Different Types of Research for Public Policy. Paper presented at the 3rd Campbell Collaboration, Stockholm, February 2003.

- Hawker S., Payne S., Kerr C., Hardey M. & Powell J. (2002) Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qualitative Health Research, 12, 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L., Gregory J. & Swan G. (2002) The National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Adults Aged 19–64 Years. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L.A. & Allen M.N. (1996) Meta‐synthesis of qualitative findings. Qualitative Health Research, 6, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney M.H. (2001) Enduring love: a grounded formal theory of women's experience of domestic violence. Research in Nursing and Health, 24, 270–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempson E., Bryson A. & Rowlingson K. (1994) Hard Times. Policy Studies Institute: London. [Google Scholar]

- King's Fund (2004) Public Attitudes to Public Health Policy. King's Fund: London. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/pdf/publicattitudesreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K.A. & Breitmayer B.J. (1991) Triangulation in qualitative research: issues of conceptual clarity and purpose In: Qualitative Nursing Research: a Contemporary Dialogue, Revised Edition (ed. Morse J.M.), pp. 226–239. Sage: Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp S.M. & Drevdahl D.J. (2003) Problems with parsimony in research on socioeconomic determinants of health. Advances in Nursing Science, 26 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobstein T. (1997) If They Don’t Eat a Healthy Diet It's Their Own Fault! Myths About Food and Low Income. National Food; Alliance: London. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J.W. (1996) Social position and health. Annals of Epidemiology, 6, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J.W., Kaplan G.A. & Salonen J.T. (1997) Why do poor people behave poorly? Variation in adult health behaviours and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the economic lifecourse. Social Science and Medicine, 44, 809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick J., Rodney P. & Varcoe C. (2003) Reinterpretation across studies: an approach to meta‐analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeever P. & Miller K.L. (2004) Mothering children who have disabilities: a Bourdieusian interpretation of maternal practices. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 1177–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendrick J.H., Cunningham‐Burley S. & Backett‐Milburn K. (2003) Life in Low Income Families in Scotland: Research Report. Scottish Executive Social Research: Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Malseed J. (1990) Bread Without Dough: Understanding Food Poverty . PhD Thesis. University of Lancaster. Horton Publishing Ltd.: Bradford.

- Marmot M. & Wilkinson R.G. (1999) Social Determinants of Health. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Mays N. & Pope C. (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 330, 50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. (2001) Qualitative verification: building evidence by extending basic findings In: The Nature of Qualitative Evidence (eds Morse J, Swanson J. & Kuzel A.), pp. 203–220. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- National Children's Home . (2004) Going Hungry: The Struggle to Eat Healthily on a Low Income. NCH: London. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . (2001) Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s Guidance for Those Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews. NHS CRD: York. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (CASP ) (2001) Appraisal Tools for Qualitative Research. Available at: http://www.phru.org.uk~casp/resources/index.htm

- Noblit G.W. & Hare R.D. (1988) Meta‐ethnography: Synthesisng Qualitative Studies. Sage Publications: London. [Google Scholar]

- Owens B. (1997) Out of the Frying Pan: the True Cost of Feeding a Family on a Low Income. Save the Children: London. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M. (2001) Systematic reviews from astronomy to zoology: myths and misconceptions. British Medical Journal, 322, 98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Rogers A. & Williams G. (1998) Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qualitative Health Research, 8, 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J. (1990) Thirty Families: Their Living Standards in Unemployment. DSS Report no. 1. HMSO: London. [Google Scholar]

- Roseneil S. & Mann K. (1996) Unpalatable choices and inadequate families: lone mothers and the underclass debate In: Good Enough Mothering?: Feminist Perspectives on Lone Motherhood (ed. Silva E.B.), pp. 191–210. Routledge: London. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M., Docherty S. & Emden C. (1997) Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Research in Nursing and Health, 20, 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. (1999) The Quality of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications: London. [Google Scholar]

- Silva E.B. (ed.) (1996) Good Enough Mothering?: Feminist Perspectives on Lone Motherhood. Routledge: London. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L., Ritchie J., Lewis J. & Dillon L. (2003) Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. Cabinet Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Suri H. (1999) The Process of Synthesizing Qualitative Research: A Case Study. Paper presented at the ‘Issues of Rigour in Qualitative Research’ Annual Conference of the Association for Qualitative Research, Melbourne, 6–10 July 1999.

- Thorne S., Jensen L., Kearney M.H., Noblit G. & Sandelowski M. (2004) Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qualitative Health Research, 14, 1342–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend P. (1990) Individual or social responsibility for premature death? Current controversies in the British debate about health. International Journal of Health Services, 20, 373–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend P. & Davidson N. (eds) (1982) Inequalities in Health: the Black Report. Penguin Books: Harmondsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Varcoe C., Rodney P. & McCormick J. (2003) Health care relationships in context: an analysis of three ethnographies. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 957–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanless D. (2004) Securing Good Health for the Whole Population: Final Report. HMSO: London. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M. (1988) The Health Divide. Penguin Books: London. [Google Scholar]