Abstract

Purpose:

To assess pain and anxiety during bone marrow aspiration/biopsy (BMA) among patients versus health-care professionals (HCPs).

Method:

235 adult hematologic patients undergoing BMA were included. BMA was performed by 16 physicians aided by nine registered nurses (RNs). Questionnaires were used to obtain patients and HCPs ratings of patients’ pain and anxiety during BMA. Patterns of ratings for pain and anxiety among patients HCPs were estimated with proportions of agreement P(A), Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ), and single-measure intra-class correlation (ICC). We also explored if associations of ratings were influenced by age, sex, type and duration of BMA.

Results:

The P(A) for occurrence of rated pain during BMA was 73% between patients and RNs, and 70% between patients and physicians, the corresponding κ was graded as fair (0.37 and 0.33). Agreement between patients and HCPs regarding intensity of pain was moderate (ICC = 0.44 and 0.42). Severe pain (VAS > 54) was identified by RNs and physicians in 34% and 35% of cases, respectively. Anxiety about BMA outcome and needle insertion was underestimated by HCPs. P(A) between patients and RNs and patients and physicians regarding anxiety ranged from 53% to 59%. The corresponding κ was slight to fair (0.10–0.21). ICC showed poor agreement between patients and HCPs regarding intensity of anxiety (0.13–0.36).

Conclusions:

We found a better congruence between patients and HCPs in pain ratings than in anxiety ratings, where the agreement was low. RNs and physicians underestimated severe pain as well as anxiety about BMA outcome and needle insertion.

Keywords: Bone marrow aspiration, Pain, Anxiety, Agreement, Health-care professionals, Patient

Introduction

Patients with cancer undergo several different and repeated diagnostic procedures during the disease trajectory. Pain caused by various procedures and situations is defined as procedural pain, i.e. an acute increase or sudden onset of pain with short duration (Heafield, 1999). Among the most painful procedures are those when instruments or devices are inserted into the body, usually by cutting or puncturing the skin (Coutaux et al., 2008). In a recent study, pain was evaluated in cancer patients undergoing different types of invasive examination. The highest pain levels were related to the procedures bone marrow aspiration/biopsy (BMA), lumbar puncture and insertion of central venous catheter (Portnow et al., 2003).

BMA is commonly performed in hematological patients to confirm diagnosis and to evaluate response to therapy. In adult patients, local infiltration anesthesia is routinely applied before BMA (Kuball et al., 2004). Previously, we conducted a prospective longitudinal study on procedure-related pain among adult hematologic patients who underwent BMA (Liden et al., 2009). Similar to prior studies (Dunlop et al., 1999; Vanhelleputte et al., 2003; Kuball et al., 2004; Steedman et al., 2006), we found BMA-related pain to be common: 70% of the patients reported pain during BMA and 35% reported severe-to-worst-possible pain (Liden et al., 2009).

Reasons for not preventing pain related to BMA may depend on health-care professionals’ insufficient knowledge of procedural pain, or on inadequate pain analysis (Field, 1996; Drayer et al., 1999; Sjostrom et al., 1999; Puntillo et al., 2003). Another possible barrier to efficient pain treatment may be poor congruence of the ratings for pain among patients versus health-care professionals (Drayer et al., 1999). Health-care professionals’ estimates of cancer patients’ pain commonly diverge from the patients’ own experience (Grossman et al., 1991; Sneeuw et al., 1999; Kuball et al., 2004; Budischewski et al., 2006). Health-care professionals seem to overestimate mild pain and underestimate severe pain (Grossman et al., 1991; Kuball et al., 2004; Budischewski et al., 2006). Anxiety often co-exists with and exacerbates the perception of pain (Ozalp et al., 2003). A poor correlation between cancer patients’ and health-care professionals’ assessments of anxiety is also reported (Badner et al., 1990; Heikkila et al., 1998; Martensson et al., 2008).

Although poor agreement between patients’ and health-care professionals’ ratings of cancer patients’ pain and anxiety is recognized, to our knowledge, there is limited empirical research focusing on procedures. Procedures are often associated with considerable discomfort and pain (Portnow et al., 2003) why such knowledge would be of value for adequate symptom management. The aim of the present study was to assess ratings for pain and anxiety during BMA among patients versus health-care professionals. Also we explored whether patterns of ratings were influenced by the patients’ age or sex, as well as the type and duration of BMA.

Methods and material

Subjects

Two hundred thirty-five (median age 62 years, range 20–89 years) of 263 (89.4%) consecutive adult patients scheduled for BMA at the outpatient clinic of the Division of Hematology, Karolinska University Hospital, were included (Table 1). Patients could only be enrolled once. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older and with a scheduled BMA. Exclusion criteria were mental disorders and linguistic difficulties, unwillingness to participate, not showing up on time for the BMA, sedative medication, or fainting before BMA. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to study enrollment. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total number, n (%) | 235 | (100) |

| Age, median years (range) | 62 | (20–89) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 109 | (46) |

| Male | 126 | (54) |

| Underlying diagnosis according to BMA, n (%) | ||

| Leukemia | 34 | (14) |

| Multiple myeloma | 39 | (17) |

| Lymphoma | 46 | (19) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 18 | (8) |

| Chronic myeloproliferative disorder | 31 | (13) |

| Other hematologic disease | 42 | (18) |

| Non-hematologic disease | 25 | (11) |

| Previous BMA, n (%) | ||

| No previous BMA | 100 | (43) |

| 1–2 times | 76 | (32) |

| 3–5 times | 27 | (11) |

| >5 times | 32 | (14) |

| Site of BMA, n (%) | ||

| Posterior iliac crest | 230 | (98) |

| Sternum | 5 | (2) |

| Type of BMA, n (%) | ||

| Bone marrow aspiration | 67 | (28) |

| Bone marrow biopsy | 88 | (37) |

| Both aspiration and biopsy | 80 | (35) |

The BMAs were performed by nine attending hematologists and seven hematology fellows (female n = 10, male n = 6). Twenty-six percent of the BMAs were performed by attending hematologists and 74% by hematology fellows. Seven out of nine attending hematologists and six out of seven hematology fellows had performed more than 100 BMAs previously. Nine RNs assisted the physicians during the BMAs. All the RNs were female with a median of four years (range 1–19 years) of professional experience.

Bone marrow aspiration/biopsy

As pain relief, a local anesthetic (Lidocaine 1% 10–20 ml) was given subcutaneously as well as with periostal infiltration. After local anesthesia, BMA was carried out using a 15 gauge × 2.7 inch aspiration needle and/or 11 gauge × 4 inch biopsy needle (Medical Device Technologies, Inc).

Data collection

Self-administered questionnaires were used to obtain information about pain and anxiety from the patients (Liden et al., 2009) and to assess physicians’ and RNs impressions of patients’ experience of pain and anxiety.

Questionnaires to patients

Prior to the BMA, the patients answered a study-specific questionnaire including questions concerning anxiety about BMA needle insertion and BMA outcome. First, the presence or absence of anxiety was recorded. Thereafter the intensity of anxiety was scored on Visual Analog Scales (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100 mm anchored 0 mm = no anxiety and 100 mm = worst possible anxiety. The participants were requested to mark the point on each line that best agreed with their experience of anxiety.

Ten minutes after the BMA, a second study-specific questionnaire about pain during the procedure was completed by the patients. First, presence or absences of pain was recorded. Then, the intensity of pain was scored on VAS with 0 mm = no pain and 100 mm = worst possible pain. Intensity > 30 mm on VAS was considered to represent moderate pain and VAS > 54 mm severe pain (Collins et al., 1997).

Questionnaires to physicians and registered nurses

The physicians performing the BMAs and the assisting RNs individually filled out a questionnaire immediately after completion of each BMA. They recorded their assessments of the patient’s pain during the BMA, anxiety about the needle insertion and anxiety about the outcome (presence or absence and intensity on VAS), without knowing the patients’ responses in the patient questionnaires. Using a standardized data-entry form, physicians and RNs also recorded their own gender, and the number of years working in hematology. Physicians also recorded the estimated number of BMAs they had carried out, as well as clinical information regarding the patient.

Statistics

Associations of ratings for occurrence of pain and anxiety during BMA among patients versus health-care professionals were assessed using proportions of agreement P(A) and Cohen’s unweighted kappa coefficient (κ), correcting for the eventuality that agreement could occur by chance alone. In accord with Landis and Koch (1977), the magnitude of the κ values was graded as follows: κ ≤0 = poor; κ 0.01–0.20 = slight; 0.21–0.40 = fair; 0.41–0.60 = moderate; 0.61–0.80 = substantial; and 0.81–1.0 = almost perfect agreement. Using the McNemar test we tested for marginal homogeneity between ratings of occurrence of pain and anxiety among patients versus health-care professionals (McNemar, 1947; Maxwell, 1970). A significant value implies that the health-care professionals either under- or overestimated the patients rating. Agreement between the patients’ and the health-care professionals’ scoring of intensity of pain and anxiety by using VAS was evaluated with single-measure intra-class correlation (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979). Based on the literature, ICC values were graded as follows: <0.4 = poor agreement; 0.4–0.74 = moderate agreement; ≥0.75–1 = good agreement (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979; Fleiss, 1986). We further explored associations of ratings for pain and anxiety during BMA among patients versus health-care professionals, by age of the patient (below/above 60 years), sex (female/male), type of BMA (bone marrow aspiration, bone marrow biopsy, or both), and duration of BMA (below/above 15 min). The level of all statistical tests was set at 0.05. The statistical calculations were done with the Stat View 5.0.1 and SPSS 14.0 software.

Results

Agreement of occurrence and intensity of pain, between patients and health-care professionals

The P(A) for rated occurrence of pain during BMA among patients versus RNs was 73%; and among patients versus physicians the P(A) was 70%. The corresponding κ-values were 0.37 and 0.33, respectively; these were both graded as fair (Table 2). For cases where the BMA took more than 15 min, the κ-value for the rated occurrence was graded as moderate (Table 2).

Table 2.

Level of agreement for ratings of occurrence and intensity of pain between patients, registered nurses and physicians (n = 235).

| Variable | n | P(A)a | Kappab | McNemarc | VAS, n | Patient VAS, median (range) | Nurse/physician, median (range) | ICCd | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain during BMA | |||||||||

| Nurse, total | 234 | 73% | 0.37 | 0.614 | 185 | 30 (1–100) | 20 (1–100) | 0.44 | (0.27–0.58) |

| Patients age | |||||||||

| ≤60 years | 108 | 78% | 0.34 | 0.540 | 90 | 30 (2–100) | 25 (3–100) | 0.58 | (0.41–0.71) |

| >60 years | 126 | 69% | 0.35 | 0.200 | 95 | 27 (1–100) | 20 (3–100) | 0.28 | (0.07–0.46) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 109 | 70% | 0.10 | 0.296 | 88 | 36 (1–100) | 22 (2–100) | 0.39 | (0.17–0.57) |

| Male | 125 | 76% | 0.46 | 0.855 | 97 | 27 (2–100) | 19 (1–95) | 0.50 | (0.31–0.65) |

| Type of BMA | |||||||||

| Biopsy | 88 | 73% | 0.39 | 0.838 | 67 | 20 (3–100) | 18 (2–95) | 0.46 | (0.25–0.63) |

| Aspiration | 66 | 64% | 0.16 | 0.540 | 52 | 38 (3–100) | 20 (1–90) | 0.26 | (−.002 to 0.49) |

| Biopsy and aspiration | 80 | 81% | 0.51 | 0.606 | 66 | 31 (1–100) | 25 (3–100) | 0.58 | (0.36–0.73) |

| BMA duration | |||||||||

| ≤15 min | 181 | 69% | 0.31 | 0.350 | 41 | 25 (2–100) | 18 (1–90) | 0.40 | (0.20–0.56) |

| >15 min | 50 | 86% | 0.55 | 0.453 | 142 | 45 (1–99) | 36 (6–1009 | 0.45 | (0.18–0.66) |

| Pain during BMA | |||||||||

| Physician, total | 234 | 70% | 0.33 | 0.073 | 156 | 36 (2–100) | 21 (2–100) | 0.42 | (0.23–0.56) |

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤60 years | 107 | 70% | 0.25 | 0.216 | 78 | 37 (2–1009 | 27 (2–100) | 0.60 | (0.41–0.73) |

| >60 years | 127 | 70% | 0.37 | 0.256 | 78 | 36 (3–100) | 16 (2–92) | 0.19 | (0.19–0.38) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 109 | 72% | 0.35 | 0.012 | 74 | 40 (4–100) | 22 (2–100) | 0.35 | (0.09–0.55) |

| Male | 125 | 69% | 0.32 | 0.873 | 82 | 28 (2–100) | 20 (2–90) | 0.50 | (0.31–0.65) |

| Type of BMA | |||||||||

| Bone marrow biopsy | 87 | 68% | 0.31 | 0.850 | 55 | 25 (3–100) | 20 (2–85) | 0.52 | (0.29–0.69) |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 67 | 72% | 0.37 | 0.359 | 45 | 43 (3–100) | 15 (2–90) | 0.16 | (−.09 to 0.40) |

| Biopsy and aspiration | 80 | 71% | 0.32 | 0.095 | 56 | 37 (2–100) | 26 (2–100) | 0.50 | (0.24–0.69) |

| BMA duration | |||||||||

| ≤15 min | 182 | 68% | 0.30 | 0.118 | 120 | 27 (3–100) | 18 (2–90) | 0.37 | (0.17–0.53) |

| >15 min | 50 | 78% | 0.42 | 0.274 | 35 | 56 (2–99) | 34 (4–100) | 0.42 | (0.19–0.65) |

Proportions of agreement P(A).

Kappa, corrects for the eventuality that agreement could occur by chance alone.

Test marginal homogeneity between ratings of occurrence of pain among patients versus health-care professionals.

Agreement between the patients’ and the health-care professionals’ scoring of intensity of pain by using VAS was evaluated with single-measure intra-class correlation (ICC).

Agreement on rated intensity of pain was graded moderate between patients and RNs (ICC = 0.44) and patients and physicians (ICC = 0.42), respectively (Table 2). Agreement regarding rated intensity of pain was moderate among RNs and physicians for patients with an age of 60 years or younger, for male patients, when bone marrow biopsy was performed alone or together with aspiration, and when BMA took > 15 min (0.42–0.60) (Table 2).

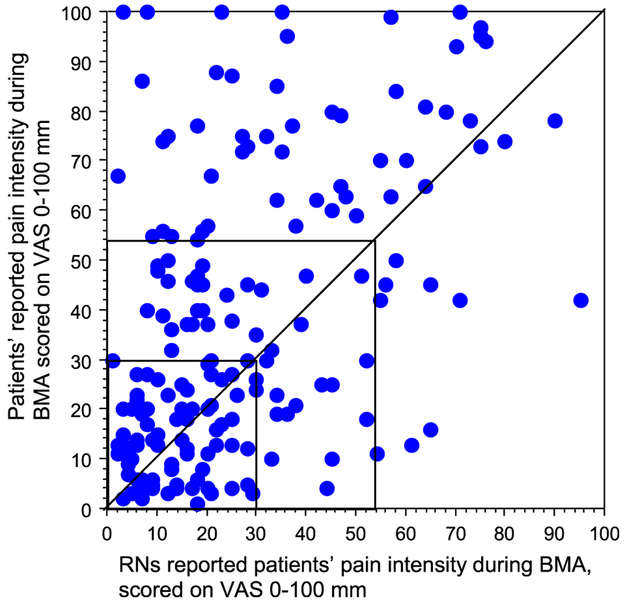

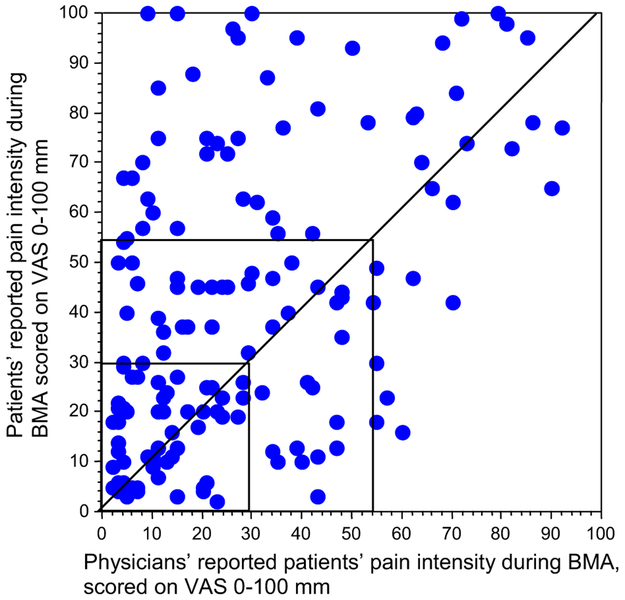

Severe pain (VAS > 54) reported by patients was identified by RNs and physicians in 34% and 35% of cases, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2). Two patients scored worst possible pain, without being observed by an RN in one case or a physician in the other. Moderate pain (VAS >30 to ≤54) reported by patients was identified to 18% by RNs and 26% by physicians (Figs. 1 and 2). Mild pain (VAS ≤ 30) reported by patients was identified to 78% by RNs and 58% by physicians. Six RNs and ten physicians scored an intensity of pain (median VAS 16 (range 3–56), VAS 20 (range 3–69), respectively) in patients who did not report occurrence of pain.

Fig. 1.

Intensity of pain during BMA. Data of 185 patients/185 RNs ratings who both reported that patient experienced pain during BMA. Intra-Class Correlation (ICC) 0.44 and 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.27–0.58.

Fig. 2.

Intensity of pain during BMA. Data of 156 patients/156 physicians’ ratings who both reported that patient experienced pain during BMA. Intra-Class Correlation (ICC) 0.42 and 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.23–0.56.

Agreement between patients and health-care professionals on occurrence and intensity of anxiety for BMA outcome

The P(A)s for occurrence of anxiety for BMA outcome between patients and RNs and patients and physicians were 56% and 55%, respectively. The corresponding κ was graded as slight (0.19 and 0.14). κ appeared fair between patients and RNs when both biopsy and aspiration was performed and when BMA took more than 15 min (0.29 and 0.33) and between patient and physicians when bone marrow aspiration was performed (0.28). κ was slight for the remaining variables (0.02–0.17) (Table 3). RNs and physicians significantly (p < 0.01) underestimated anxiety about BMA outcome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Agreement on occurrence and intensity of anxiety about BMA outcome between patients and registered nurses and physicians (n = 235).

| Variable | n | P(A)a | Kappab | McNemarc | VAS, n | Patient VAS, median (range) | Nurse/physician, median (range) | ICCd | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety about BMA outcome | |||||||||

| Nurse, total | 227 | 56% | 0.19 | 0.009 | 147 | 50 (1–100) | 18 (1–100) | 0.13 | (−0.03 to 0.28) |

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤60 years | 104 | 63% | 0.09 | 0.045 | 80 | 54 (1–100) | 22 (2–100) | 0.22 | (−.01 to 0.42) |

| >60 years | 123 | 54% | 0.08 | 0.111 | 67 | 37 (2–100) | 15 (1–85) | −.01 | (−.16 to 0.16) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 108 | 58% | 0.13 | 0.007 | 76 | 60 (2–1009 | 18 (2–100) | 0.08 | (−.08 to 0.26) |

| Male | 119 | 55% | 0.10 | 0.341 | 71 | 34 (1–100) | 20 (1–74) | 0.09 | (−.09 to 0.26) |

| Type of BMA | |||||||||

| Bone marrow biopsy | 87 | 52% | 0.02 | 0.165 | 57 | 48 (1–100) | 18 (2–1009 | 0.11 | (−.10 to 0.33) |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 64 | 53% | 0.07 | 0.018 | 46 | 50 (3–100) | 20 (1.87) | 0.07 | (−.11 to 0.28) |

| Both biopsy and aspiration | 76 | 64% | 0.29 | 0.700 | 44 | 51 (2–100) | 18 (2–83) | 0.22 | (−.06 to 0.48) |

| BMA duration | |||||||||

| ≤15 min | 176 | 53% | 0.06 | 0.020 | 113 | 50 (1–100) | 18 (1–95) | 0.12 | (−.04 to 0.29) |

| >15 min | 48 | 67% | 0.33 | 0.453 | 32 | 46 (2–100) | 22 (2–100) | 0.14 | (−.16 to 0.44) |

| Anxiety about BMA outcome | |||||||||

| Physician, total | 234 | 55% | 0.14 | 0.000 | 98 | 50 (1–100) | 23 (2–100) | 0.30 | (0.06–0.50) |

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤60 years | 107 | 51% | 0.05 | 0.001 | 59 | 50 (1–100) | 26 (2–100) | 0.46 | (0.17–0.66) |

| >60 years | 127 | 57% | 0.16 | 0.0002 | 39 | 50 (2–100) | 20 (3–85) | 0.07 | (−.14 to 0.31) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 109 | 54% | 0.11 | 0.000 | 51 | 63 (1–100) | 27 (4–100) | 0.18 | (−.05 to 0.42) |

| Male | 125 | 55% | 0.12 | 0.002 | 47 | 34 (1–100) | 18 (2–799 | 0.36 | (0.06–0.60) |

| Type of BMA | |||||||||

| Bone marrow biopsy | 87 | 51% | 0.05 | 0.006 | 37 | 49 (1–100) | 21 (2–100) | 0.27 | (−.02 to 0.54) |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 67 | 61% | 0.28 | 0.000 | 31 | 60 (4–100) | 26 (4–79) | 0.38 | (−.06 to 0.68) |

| Both biopsy and aspiration | 80 | 54% | 0.10 | 0.049 | 30 | 51 (2–100) | 22 (3–100) | 0.28 | (−.04 to 0.56) |

| BMA duration | |||||||||

| ≤15 min | 182 | 52% | 0.12 | 0.000 | 73 | 52 (1–100) | 21 (2–100) | 0.32 | (0.01–0.56) |

| >15 min | 50 | 60% | 0.17 | 0.500 | 25 | 45 (2–100) | 35 (5–100) | 0.24 | (−.15 to 0.57) |

Proportions of agreement P(A).

Kappa corrects for the eventuality that agreement could occur by chance alone.

Test marginal homogeneity between ratings of occurrence of anxiety among patients versus health-care professionals.

Agreement between the patients’ and the health-care professionals’ scoring of intensity of anxiety by using VAS was evaluated with single-measure intra-class correlation (ICC).

The ICC showed poor agreement of rated intensity of anxiety for BMA outcome between patients and health-care professionals. ICC demonstrated moderate agreement among physicians and patients with an age of 60 years or younger (0.46). In all other analyzes regarding age, sex, type of BMA and BMA duration the ICC was in the poor range (−.01 to 0.38) (Table 3).

Agreement between patients and health-care professionals on occurrence and intensity of anxiety about needle insertion

The P(A)s between patients and RNs and patients and physicians for rated occurrence of anxiety about needle insertion were 53% and 59% respectively. The corresponding κ was graded as slight and fair. Between patients and RNs, κ appeared fair when both biopsy and aspiration were performed (0.23). Between patients and physicians, the following variables were fair; patients’ age > 60 years, when bone marrow aspiration was performed, when bone marrow biopsy was performed, and when the BMA took more than 15 min (0.22–0.23). κ was slight for the remaining variables (Table 4). Health-care professionals significantly (p < 0.001) underestimated patients’ anxiety regarding needle insertion (Table 4).

Table 4.

Agreement on occurrence and intensity of anxiety about needle insertion between patient and registered nurse and physicians (n = 235).

| Variable | n | P(A)a | Kappab | McNemarc | VAS, n | Patient VAS, median (range) | Nurse/physician, median (range) | ICCd | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety about needle insertion | |||||||||

| Nurse, total | 233 | 53% | 0.10 | 0.0000 | 132 | 48 (1–100) | 10 (1–100) | 0.24 | (−.05 to 0.47) |

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤60 years | 107 | 51% | 0.10 | 0.0000 | 71 | 50 (1–100) | 13 (1–100) | 0.31 | (−.06 to 0.59) |

| >60 years | 126 | 55% | 0.05 | 0.0002 | 61 | 44 (2–1009 | 10 (1–83) | 0.15 | (−.07 to 0.36) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 109 | 50% | 0.07 | 0.0001 | 67 | 64 (1–100) | 14 (1–100) | 0.26 | (−.06 to 0.53) |

| Male | 124 | 56% | 0.09 | 0.0006 | 65 | 44 (1–98) | 9 (1–83) | 0.11 | (−.07 to 0.31) |

| Type of BMA | |||||||||

| Bone marrow biopsy | 87 | 52% | 0.06 | 0.0004 | 47 | 44 (1–100) | 10 (1–78) | 0.23 | (−.07 to 0.50) |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 66 | 44% | 0.05 | 0.0000 | 45 | 50 (4–100) | 9 (1–78) | 0.20 | (−.09 to 0.48) |

| Both biopsy and aspiration | 80 | 62% | 0.23 | 0.361 | 40 | 46 (1–1009 | 14 (1–100) | 0.30 | (−.02 to 0.57) |

| BMA duration | |||||||||

| ≤15 min | 180 | 52% | 0.06 | 0.000 | 97 | 47 (1–100) | 9 (1–83) | 0.19 | (−.06 to 0.43) |

| >15 min | 50 | 58% | 0.20 | 0.029 | 33 | 64 (1–100) | 16 (1–100) | 0.29 | (−.05 to 0.58) |

| Anxiety about needle insertion | |||||||||

| Physician total | 234 | 59% | 0.21 | 0.0000 | 81 | 50 (81–100) | 17 (1–100) | 0.36 | (0.00–0.60) |

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤60 year | 107 | 54% | 0.18 | 0.0000 | 43 | 61 (3–100) | 17 (2–100) | 0.31 | (−.07 to 0.60) |

| >60 year | 127 | 63% | 0.23 | 0.0013 | 38 | 45 (1–100) | 17 (1–100) | 0.41 | (0.06–0.66) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 109 | 56% | 0.18 | 0.0000 | 45 | 74 (3–100) | 17 (1–100) | 0.30 | (−.05 to 0.58) |

| Male | 125 | 62% | 0.19 | 0.0000 | 36 | 40 (1–98) | 17 (2–100) | 0.38 | (0.01–0.65) |

| Type of BMA | |||||||||

| Bone marrow biopsy | 87 | 61% | 0.24 | 0.004 | 25 | 64 (7–100) | 23 (1–74) | 0.10 | (−.16 to 0.41) |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 67 | 57% | 0.22 | 0.0000 | 34 | 46 (1–100) | 16 (3–71) | 0.40 | (−.08 to 0.71) |

| Both biopsy and aspiration | 80 | 59% | 0.14 | 0.082 | 22 | 75 (3–100) | 15 (2–100) | 0.50 | (0.06–0.77) |

| BMA duration | |||||||||

| ≤15 min | 182 | 58% | 0.19 | 0.0000 | 57 | 47 (1–100) | 13 (1–100) | 0.31 | (−.06 to 0.59) |

| >15 min | 50 | 60% | 0.23 | 0.0442 | 24 | 70 (4–100) | 34 (3–100) | 0.41 | (0.03–0.69) |

Proportions of agreement P(A).

Kappa corrects for the eventuality that agreement could occur by chance alone.

Test marginal homogeneity between ratings of occurrence of anxiety among patients versus health-care professionals.

Agreement between the patients’ and the health-care professionals’ scoring of intensity of anxiety by using VAS was evaluated with single-measure intra-class correlation (ICC).

ICC demonstrated poor agreement between patients and health-care professionals regarding intensity of anxiety about needle insertion. ICC demonstrated moderate agreement between physicians and patients with an age >60 years, when both biopsy and aspiration were performed and when BMA took >15 min (0.41–0.50). In all other analyses regarding age, sex, type of BMA and BMA duration the ICC was in the poor range (0.10–0.40).

Discussion

Overall we found a discrepancy in ratings of occurrence of pain between patients and health-care professionals. Furthermore, our results showed low agreement on rated anxiety about the BMA outcome and needle insertion; and that both RNs and physicians underestimated patients’ pain and anxiety. These finding are novel and of major importance because incongruence in ratings and in particular underestimation of patients’ experience of pain and anxiety during BMA may lead to unnecessary suffering for patients.

In our study, the level of agreement for rated pain by patients and health-care professionals during BMA was graded as fair. In a prior study by Kuball et al. (2004) the level of agreement between patients and physicians was graded as moderate. We were unable to further assess underlying causes of these discrepancies and we have speculated that they may be due to differences in patient populations and/or health-care professionals. The rating for intensity of pain during BMA among patients versus health-care professionals was graded moderate. Importantly, in accord with the literature (Grossman et al., 1991; Harrison, 1991; Curtiss, 2001; Kuball et al., 2004), the occurrence of severe pain (>54 mm on VAS), present in 32% of the patients, was recognized by the RNs and physicians only in one third of the affected patients. Indeed, underestimation of severe pain, including procedural pain, appears to be common in a variety of patient care settings (Grossman et al., 1991; Harrison, 1991; Curtiss, 2001; Kuball et al., 2004). Prior studies have suggested that underestimation of severe pain could depend on RNs’ and physicians’ working experience, where those with longer experience have been found to underestimate the pain more frequently than do those with less experience (Choiniere et al., 1990; Marquie et al., 2003). As pointed out previously, a difference with regard to ratings of pain among patients and health-care professionals might depend on that the two groups relate to different experience when scoring pain (Gollop, 1986; Levin et al., 1998). For example, while the patient refers to his/her personal prior pain experience, a health-care professional relates both to his/her personal prior pain experience as well as the range of pain among prior patients (Gollop, 1986; Levin et al., 1998). We found better agreement for the rated occurrence of pain between patients and health-care professionals when, e.g., the BMA took more than 15 min, suggesting that staff might expect a longer BMA to be more painful since such BMAs may often be associated with procedure-related problems. Another proposed factor that influences the evaluation of rated pain among patients and health-care professionals is that health-care professionals sometimes believe some patients to exaggerate the severity of their pain (Drayer et al., 1999) while they sometimes believe that other patients act as they have to endure some pain (Idvall, 2002) and therefore ignore its intensity.

The diagnosis of cancer causes the patient anxiety and stress, which are due to the patients’ perception of cancer, its manifestations, and treatment (Ozalp et al., 2003; Degen et al., 2010). Indications for BMA include the diagnosis, staging and therapeutic monitoring of the disease. Most patients with hematological malignancies must undergo repeated BMAs (Bain, 2001; Degen et al., 2010). Anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of the BMA increases the patients’ experience of pain during BMA (Liden et al., 2009). To our knowledge, our study is the first systematic investigation of rated anxiety by BMA outcome conducted by patients, RNs and physicians. We found that patients expressed anxiety about the BMA outcome more frequently and much more intensely than the RNs and physicians were able to identify. Previous studies on anxiety and depression in hospitalized patients with cancer have also reported poor-to-slight agreement between cancer patients’ and staff’s ratings of anxiety (Lampic et al., 1996). Some studies observe that staff tends to overestimate anxiety and emotional distress (Faller et al., 1995; Lampic et al., 1996; Heikkila et al., 1998; Lampic and Sjoden, 2000; Martensson et al., 2008) whilst others have found that this is not the case (Badner et al., 1990; von Essen, 2004). It has been suggested that poor skill in identifying patients’ anxiety may be because staff lack the time to discern the patients’ emotional distress; but also that patients do not express their anxiety (Radwin, 1996; Kruijver et al., 2006).

Regarding anxiety over needle insertion, we found poor-to-slight agreement between patient and health-care professionals. Both RNs and physicians strongly underestimated patients’ anxiety here. In the literature, needle anxiety is well known among patients with diabetes, those undergoing dental procedures and those on intravenous chemotherapy (Hamilton, 1995; Mollema et al., 2001; Kettwich et al., 2007). Needle anxiety can be traced back to an adverse experience with needles in health-care. A bad experience can lead to a generalized, learned, negative response to different needle procedure (Marks, 1988). Most patients with blood cancer undergo intensive chemotherapy, venepunctures, lumbar punctures and repeated BMAs. Their attitude should be assessed, as the development of needle anxiety may cause delay or avoidance of appropriate medical care.

The main methodological strengths of the present study are the large sample size and the high response rate. Further, the physicians and RNs were blinded to the patients’ ratings of pain and anxiety. However, one limitation is that we compared small staff samples with a larger patient sample. Differences between individual RNs and physicians such as personal characteristics may thus have influenced the results. On the other hand, the intention was to investigate the overall agreement between patients, RNs and physicians, not how individual RNs and physicians assess patients’ pain and anxiety during BMA. Further, the timing when our questionnaires regarding anxiety were completed diverged between patients, RNs and physicians. Thus, all the patients answered the anxiety questions prior to the BMA while the staff responded to these items immediately after each. This could have influenced the congruence regarding anxiety. However, only this method of distributing the questionnaires was considered feasible, since the staff member’s first meeting with the patient was in the consulting room where the BMA was performed.

The discrepancy between the patients’ perception of pain and the health-care professionals’ assessment can be a predictor of poor pain management (Curtiss, 2001). Pre-existing pain and anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA or needle insertion have been found to be independent risk factors for increased pain experience during BMA (Liden et al., 2009). It is therefore of major interest to take account of the patient’s self-assessment of pain and anxiety. Today, we know that procedure-related pain may have other consequences than patients’ acute pain (Wincent et al., 2003). There is growing evidence that unrelieved acute pain can generate chronic pain (Kehlet et al., 2006), and pain perception can be intensified if accompanied by anxiety (Kain et al., 2000; Ozalp et al., 2003). Thus, it is urgent to develop staff knowledge regarding pain and anxiety assessment, conduct analyzes and document patients’ pain and anxiety related to BMAs.

In conclusion, we found a discrepancy between patients and health-care professionals ratings of occurrence and intensity of pain during BMA. In ratings of anxiety the agreement was even lower. A slightly better congruence between patients and health-care professionals was observed when the BMA included a biopsy or when the BMA took more than 15 min. Our results also show that both RNs and physicians underestimated severe pain reported by the patients. Moreover, the health-care professionals underestimated the anxiety for needle insertion and BMA outcome patients experienced. Results from this study emphasize the need for adequate symptom assessment. As pain and anxiety are subjective, patients’ own reports are the most valid measures of the experience. They can easily be obtained by asking patients to quantify their pain and anxiety before and after undergoing a procedure.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any financial or personal relationship with other persons or organizations that could inappropriately influence the work reported here.

References

- Badner NH, Nielson WR, Munk S, Kwiatkowska C, Gelb AW, 1990. Preoperative anxiety: detection and contributing factors. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 37 (4 Pt 1), 444–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain BJ, 2001. Bone marrow aspiration. Journal of Clinical Pathology 54 (9), 657–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budischewski KM, de la Fuente F, Nierhoff CF, Mose S, 2006. The burden of pain of inpatients undergoing radiotherapy – discrepancies in the ratings of physicians and nurses. Onkologie 29 (10), 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choiniere M, Melzack R, McQuay HJ, 1990. Comparisons between patients’ and nurses’ assessment of pain and medication efficacy in severe burn injuries. Pain 40 (2), 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ, 1997. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain 72 (1–2), 95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutaux A, Salomon L, Rosenheim M, Baccard AS, Quiertant C, Papy E, Blanchon T, Collins E, Cesselin F, Binhas M, Bourgeois P, 2008. Care related pain in hospitalized patients: a cross-sectional study. European Journal of Pain 12 (1), 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss CP, 2001. JCAHO: meeting the standards for pain management. Orthopedic Nursing 20 (2), 27–30. 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen C, Christen S, Rovo A, Gratwohl A, 2010. Bone marrow examination: a prospective survey on factors associated with pain. Annals of Hematology 89 (6), 619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayer RA, Henderson J, Reidenberg M, 1999. Barriers to better pain control in hospitalized patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 17 (6), 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop TJ, Deen C, Lind S, Voyle RJ, Prichard JG, 1999. Use of combined oral narcotic and benzodiazepine for control of pain associated with bone marrow examination. Southern Medical Journal 92 (5), 477–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller H, Lang H, Schillings S, 1995. Emotional distress and hope in lung cancer patients, as perceived by patients, relatives, physicians, nurses and interviewers. Psycho-Oncology 4, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Field L, 1996. Are nurses still underestimating patients’ pain postoperatively? British Journal of Nursing 5 (13), 778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss J, 1986. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. Wiley Inc, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gollop S, 1986. Pain: a summary. Nursing (London) 3 (10), 382–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SA, Sheidler VR, Swedeen K, Mucenski J, Piantadosi S, 1991. Correlation of patient and caregiver ratings of cancer pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 6 (2), 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JG, 1995. Needle phobia: a neglected diagnosis. Journal of Family Practice 41 (2), 169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, 1991. Assessing patients’ pain: identifying reasons for error. Journal of Advanced Nursing 16 (9), 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heafield RH, 1999. The management of procedural pain. The Professional Nurse 15 (2), 127–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila J, Paunonen M, Laippala P, Virtanen V, 1998. Nurses’ ability to perceive patients’ fears related to coronary arteriography. Journal of Advanced Nursing 28 (6), 1225–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idvall E, 2002. Post-operative patients in severe pain but satisfied with pain relief. Journal of Clinical Nursing 11 (6), 841–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Alexander GM, Pincus S, Mayes LC, 2000. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing hysterectomy. A repeated-measures design. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 49 (6), 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ, 2006. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 367 (9522), 1618–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettwich SC, Sibbitt WL, Brandt JR, Johnson CR, Wong CS, Bankhurst AD, 2007. Needle phobia and stress-reducing medical devices in pediatric and adult chemotherapy patients. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 24 (1), 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruijver IP, Garssen B, Visser AP, Kuiper AJ, 2006. Signalising psychosocial problems in cancer care: the structural use of a short psychosocial checklist during medical or nursing visits. Patient Education and Counseling 62 (2), 163–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuball J, Schutz, Gamm H, Weber M, 2004. Bone marrow puncture and pain. Acute Pain 6, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lampic C, Sjoden PO, 2000. Patient and staff perceptions of cancer patients’ psychological concerns and needs. Acta Oncologica 39 (1), 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampic C, von Essen L, Peterson VW, Larsson G, Sjoden PO, 1996. Anxiety and depression in hospitalized patients with cancer: agreement in patient–staff dyads. Cancer Nursing 19 (6), 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG, 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33 (1), 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ML, Berry JI, Leiter J, 1998. Management of pain in terminally ill patients: physician reports of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 15 (1), 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liden Y, Landgren O, Arner S, Sjolund KF, Johansson E, 2009. Procedure-related pain among adult patients with hematologic malignancies. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 53 (3), 354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks I, 1988. Blood-injury phobia: a review. The American Journal of Psychiatry 145 (10), 1207–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquie L, Raufaste E, Lauque D, Ecoiffier M, Sorum P, 2003. Pain rating by patients and physicians: evidence of systematic pain miscalibration. Pain 102 (3), 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson G, Carlsson M, Lampic C, 2008. Do nurses and cancer patients agree on cancer patients’ coping resources, emotional distress and quality of life? European Journal of Cancer Care 17 (4), 350–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A, 1970. Comparing the classification of subjects by two independent judges. British Journal of Psychiatry 116, 651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNemar Q, 1947. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 12, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollema ED, Snoek FJ, Haine RJ, van der Ploeg HM, 2001. Phobia of self-injecting and self-testing in insulin-treated diabetes patients: opportunities for screening. Diabetic Medicine 18 (8), 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozalp G, Sarioglu R, Tuncel G, Aslan K, Kadiogullari N, 2003. Preoperative emotional states in patients with breast cancer and postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 47 (1), 26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnow J, Lim C, Grossman SA, 2003. Assessment of pain caused by invasive procedures in cancer patients. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 1 (3), 435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntillo K, Neighbor M, O’Neil N, Nixon R, 2003. Accuracy of emergency nurses in assessment of patients’ pain. Pain Management Nursing 4 (4), 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwin LE, 1996. Knowing the patient: a review of research on an emerging concept. Journal of Advanced Nursing 23 (6), 1142–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL, 1979. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin 86 (2), 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom B, Dahlgren LO, Haljamae H, 1999. Strategies in postoperative pain assessment: validation study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 15 (5), 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, Detmar SB, Wever LD, Schornagel JH, 1999. Evaluating the quality of life of cancer patients: assessments by patients, significant others, physicians and nurses. British Journal of Cancer 81 (1), 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steedman B, Watson J, Ali S, Schields ML, Patmore RD, Allsup DJ, 2006. Inhaled nitrous oxide (Entonox) as a short acting sedative during bone marrow examination. Clinical and Laboratory Haematology 28 (5), 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhelleputte P, Nijs K, Delforge M, Evers G, Vanderschueren S, 2003. Pain during bone marrow aspiration: prevalence and prevention. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 26 (3), 860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Essen L, 2004. Proxy ratings of patient quality of life-factors related to patient–proxy agreement. Acta Oncologica 43 (3), 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincent A, Liden Y, Arner S, 2003. Pain questionnaires in the analysis of long lasting (chronic) pain conditions. European Journal of Pain 7 (4), 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]