Abstract

The International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005) are an essential vehicle for addressing global health security. Here, we report the IHR capacities in the WHO African from independent joint external evaluation (JEE). The JEE is a voluntary component of the IHR monitoring and evaluation framework. It evaluates IHR capacities in 19 technical areas in four broad themes: ‘Prevent’ (7 technical areas, 15 indicators); ‘Detect’ (4 technical areas, 13 indicators); ‘Respond’ (5 technical areas, 14 indicators), points of entry (PoE) and other IHR hazards (chemical and radiation) (3 technical areas, 6 indicators). The IHR capacity scores are graded from level 1 (no capacity) to level 5 (sustainable capacity). From February 2016 to March 2019, 40 of 47 WHO African region countries (81% coverage) evaluated their IHR capacities using the JEE tool. No country had the required IHR capacities. Under the theme ‘Prevent’, no country scored level 5 for 12 of 15 indicators. Over 80% of them scored level 1 or 2 for most indicators. For ‘Detect’, none scored level 5 for 12 of 13 indicators. However, many scored level 3 or 4 for several indicators. For ‘Respond’, none scored level 5 for 13 of 14 indicators, and less than 10% had a national multihazard public health emergency preparedness and response plan. For PoE and other IHR hazards, most countries scored level 1 or 2 and none scored level 5. Countries in the WHO African region are commended for embracing the JEE to assess their IHR capacities. However, major gaps have been identified. Urgent collective action is needed now to protect the WHO African region from health security threats.

Keywords: Africa, acute public health event, health security, health emergencies, integrated disease surveillance and response, international health regulations, outbreaks, world health organisation

Summary box.

The International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005) are an essential vehicle for addressing global health security. Previously, countries have been self-reporting their IHR capacities. Here, we report the IHR capacities in the WHO African region from independent joint external evaluation.

No country had all the required IHR capacities. The immunisation technical area was a common strength for many countries. No country had ‘no capacity’ (level 1), and seven countries (18%) had demonstrated (level 4) or sustainable (level 5) capacity. Similarly, no country had ‘no capacity’ (level 1) for real-time surveillance and one country had sustainable (level 5) capacity.

Major gaps were observed in the following technical areas: antimicrobial resistance, biosafety and biosecurity, preparedness, emergency response operations, medical countermeasures and personnel deployment, PoE, chemical events and radiation emergencies.

Moving forward, decisive action is needed now to ensure that people in the WHO African region are better protected from epidemics and other public health emergencies. All countries in the WHO African region should urgently establish robust national public health capabilities, infrastructure and processes. The latter should be assessed regularly through an objective and transparent process.

Introduction

Outbreaks and other acute public health emergencies continue to affect the WHO African region. An acute public health event (PHE) is reported every 3–4 days, which is more than 150 acute PHEs annually.1 The entire WHO African region is at risk of health security threats.1 2 Of particular concern are emerging and re-emerging pathogens. For instance, the Ebola and Marburg Virus Disease outbreaks, which were previously rare, have recently caused devastating outbreaks in the region.3–12 The top three causes of infectious disease outbreaks in 2017 were cholera, viral haemorrhagic diseases and measles.1 Further, several outbreaks of meningococcal meningitis have recently occurred outside the meningitis belt, suggesting that the latter may be expanding.13 Moreover, humanitarian crises continue to disrupt livelihoods, and the economy of the countries at risk.14 Further, rapid population growth, unplanned rapid urbanisation and the effects of climate change continue to impact negatively on the region.15 16

The IHR (2005) constitute the essential vehicle for addressing global health security.17 The IHR (2005) aim at protecting global health security while avoiding unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.17 Under the IHR, countries are obliged to develop and maintain the required capacities for surveillance and response, to detect, assess, notify and respond to any public health emergency of potential international concern.17 In accordance with the IHR, countries must report their IHR implementation status annually to the World Health Assembly (WHA) and the WHO Executive Board.17 18

In the WHO African region, the implementation of the IHR has previously been facilitated by the implementation of the integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) and the disaster risk management strategies.19–29 However, the Ebola virus disease outbreak of 2013–2016 in West Africa highlighted major gaps in IHR implementation.30–33 According to the self-assessment reports, by 2016, no country in the WHO African region had all the required IHR capacities.34 The latter is attributed to inadequate health systems in most countries.35

Before 2015, countries were self-reporting their IHR implementation status, annually to the WHA.17 However, several IHR review committees and various experts’ panels have recommended, in addition to mandatory annual reporting, three voluntary components. These include After Action Reviews, Simulations and Exercises and importantly, voluntary joint external evaluation (JEE).33 36 37 Consequently, in 2015, WHO and partners developed the JEE tool based on existing tools,38 such as the WHO IHR self-assessment questionnaire,26 the Global Health Security Agenda assessment tool,39 and the Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Performance of Veterinary Services pathway tool.40 The JEE among others provides an objective basis for the evidence-led formulation of national action plans for health security (NAPHS).37 41

Here, we present the baseline status of the IHR (2005) capacities in the WHO African region generated from the JEEs conducted between February 2016 and March 2019. Further, we share the challenges, best practices and lessons learnt. We believe that the experiences and lessons learnt from the WHO African region could motivate other WHO regions that are yet to embrace and scale up the JEEs, as part of evidence-led NAPHS.

The JEE process and core capacity grading

The JEE tool is a data gathering instrument designed to evaluate the IHR (2005) capacities in 19 technical areas, using 48 indicators categorised under four broad themes: prevent, detect, respond and other IHR hazards and PoE (table 1).38

Table 1.

JEE technical areas and number of indicators

| Technical areas | Number of indicators |

| Prevent | |

| National legislation, policy and financing | 2 |

| IHR coordination, communication and advocacy | 1 |

| Antimicrobial resistance | 4 |

| Zoonotic disease | 3 |

| Food safety | 1 |

| Biosafety and biosecurity | 2 |

| Immunisation | 2 |

| Detect | |

| National laboratory systems | 4 |

| Real-time surveillance | 4 |

| Reporting | 2 |

| Work force development | 3 |

| Respond | |

| Emergency preparedness | 2 |

| Emergency response operations | 4 |

| Linking public health with security authorities | 1 |

| Medical countermeasures and personnel deployment | 2 |

| Risk communication | 5 |

| Other IHR hazards and points of entry | |

| Points of entry | 2 |

| Chemical events | 2 |

| Radiation emergencies | 2 |

| Total | 48 |

IHR, International Health Regulations; JEE, joint external evaluation.

The JEE tool and process has been widely accepted among the majority of WHO member states and national and international agencies because it was developed through international collaboration with Member States, subject matter experts, international organisations and existing initiatives. Scores for each of the 19 technical areas represent the arithmetic mean of the scores for the indicators of that technical area. Each indicator is scored on a 5-point ordinal scale. A score of 1 reflects no pertinent capacity, 2 is limited capacity, 3 is developed capacity, 4 connotes demonstrated capacity and a score of 5 reflects sustainable capacity (table 2).

Table 2.

The JEE grading and scoring

| Capacity grading, colour code and score | Attribute description |

| No capacity—score 1 (red) | Attributes of a capacity are not in place |

| Limited capacity—score 2 (yellow) | Attributes of a capacity are in the development stage (some are achieved, and some are undergoing; however, the implementation has started) |

| Developed capacity—score 3 (yellow) | Attributes of a capacity are in place; however, there is the issue of sustainability and measured by lack of inclusion in the operational plan in National Health Sector Planning (NHSP) and/or secure funding |

| Demonstrated capacity—score 4 (green) | Attributes are in place, sustainable for a few more years and can be measured by the inclusion of attributes or IHR (2005) core capacities in the national health sector plan-green |

| Sustainable capacity—score 5 (green) | Attributes are functional, sustainable and the country is supporting other countries in its implementation. This is the highest level of the achievement of implementation of IHR (2005) core capacities |

IHR, International Health Regulation; JEE, joint external evaluation.

The JEE is an evaluation and not research. It, therefore, does not require protocol approvals. Further, it is voluntary and emphasises a multisectoral approach for both the external team and the host country. It is an open, collaborative process for assessing a country’s IHR capabilities. It is a peer-to-peer evaluation and encourages transparency and openness of data and information sharing, and the public release of reports. Therefore, there are no ethical issues on the secondary analysis of JEE data as the JEE reports are available in the public domain.

Compilation, analysis and presentation of the JEE findings

Presently, there is no standardised weighting scheme to generate composite JEE indices from the 19 technical areas. Moreover, the benefit of presenting a single composite JEE index is also a subject for scientific debate. In view of the latter, we have elected to present the non-weighted arithmetic mean scores for each of the 19 technical areas and the number of countries within each score level. For visualisation purposes, we graphically present the data using a 5-category colour-coding to represent different score levels, specifically score 1=20%, no capacity (red), score 2=21%–40%, limited capacity (brown), score 3=41%–60%, developed capacity (yellow), score 4=61%–80%, demonstrated capacity (light green) and score 5=80% and above, sustainable capacity (dark green). While this analysis looks basic, it presents a non-biased baseline status of the IHR capacities in the WHO African region.

Current status of the International Health Regulation capacities in the WHO African region

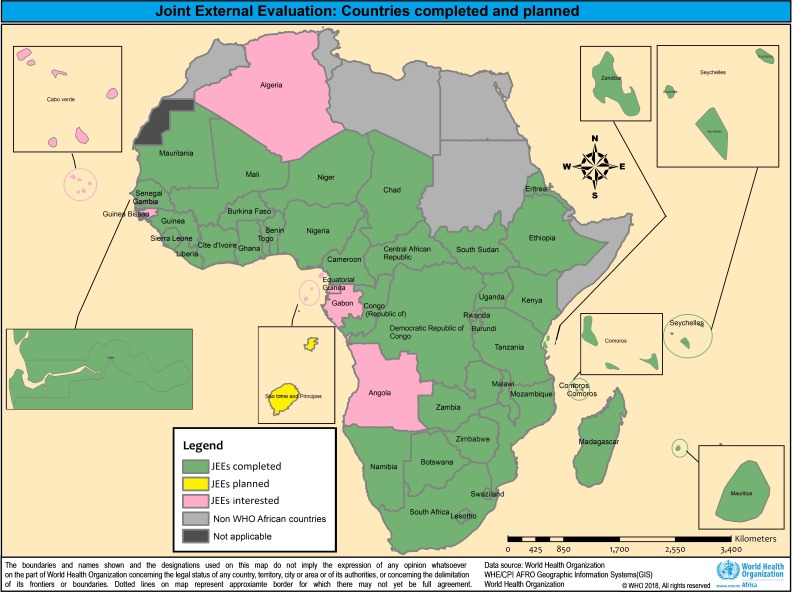

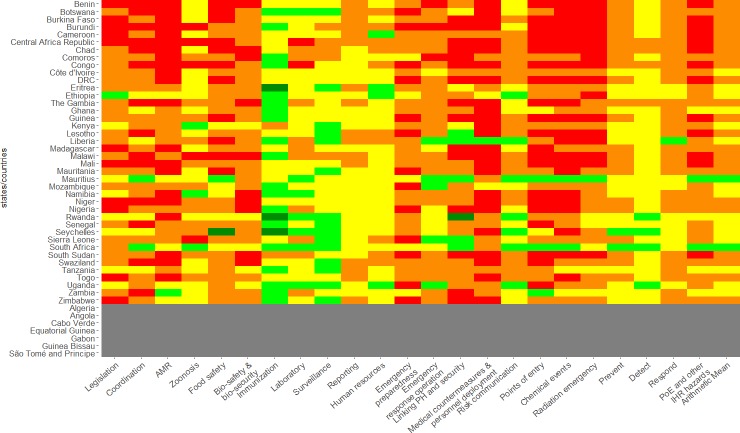

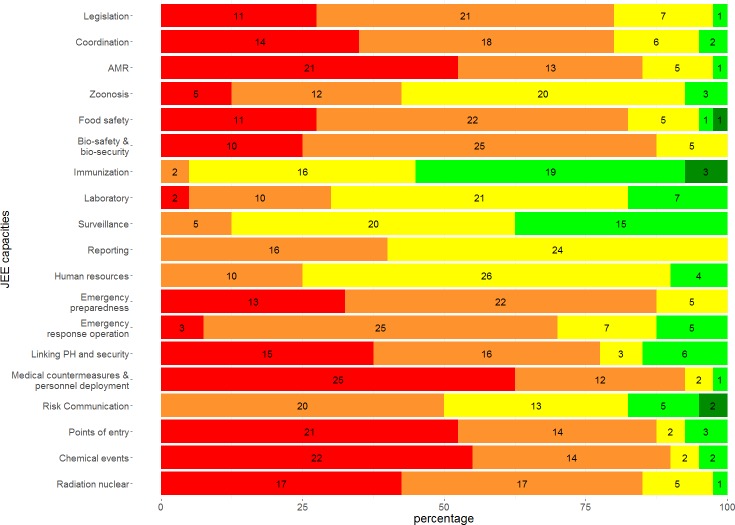

Between, February 2016 and March 2019, 40 of 47 countries in the WHO African region (over 80% coverage) conducted a JEE (figure 1). A separate JEE was conducted for the island of Zanzibar. The WHO African region is the leading region, with over 42% (40 of 95) of the JEE conducted globally. The JEEs have demonstrated that no African country has all the required IHR capacities (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Map of Africa showing countries that have completed the JEE (green), have JEE in the pipeline (yellow) and have not volunteered for a JEE (red). JEE, joint external evaluation.

Figure 2.

WHO African region JEE scorecard for the 19 JEE technical area (N=40), arithmetic means for prevent, detect, respond, PoE and other IHR hazards and for all 19 technical areas, AMR, antimicrobial resistance, IHR, International Health Regulations; JEE Joint External Evaluation; PH public health, PoE points of entry.

Figure 3.

The number of African countries in each IHR capacity score level for each of the 19 JEE technical areas (N=40), AMR, antimicrobial resistance, IHR, International Health Regulations; JEE Joint External Evaluation; PH public health, PoE points of entry.

In the broad thematic area of ‘prevent’, no country has capacity level 5 for 12 of 15 indicators. Capacity level 5 was recorded for three indicators: ‘surveillance systems for priority zoonotic diseases’ in one country, ‘vaccine coverage (measles) as part of the national programme in one country’ and ‘national vaccine access and delivery system in two countries’. For three technical areas (legislation, policy and financing, IHR coordination, communication and advocacy and antimicrobial resistance)>80% of the countries had either no capacity (score 1) or limited capacity (score 2). For two other technical areas (food safety and biosafety and biosecurity), >70% of the countries had either no capacity or limited capacity. The technical area with relatively higher IHR capacity scores was immunisation (figures 2 and 3). In the thematic area of ‘detect’, no country had capacity level 5 for 12 of the 13 indicators. Capacity level 5 was recorded for only one indicator ‘laboratory testing for priority diseases in one country’.

In contrast to prevent, many countries had a capacity level 3 or 4 for several indicators: 70% for ‘laboratory testing for detection of priority diseases’ and ‘efficient reporting to FAO, OIE and WHO’, 80% for ‘indicator or event-based surveillance systems’ and ‘field epidemiology training programmes’ and over 80% for ‘integration and data analysis’. Except for a few countries, workforce capacity had very low scores (figures 2 and 3). In the thematic area of ‘respond’, no country had capacity level 5 for 13 of 14 indicators. Less than 10% of the countries had a national multihazard public health emergency preparedness and response plan, and hardly 7% had mapped priority risks and resources. Over two-thirds of the countries had either no capacity or limited capacity to activate emergency operations and close to 80% of them had neither a public health emergency operation centre nor an emergency operations programme. Over 80% of them did not have linkages between public health and security authorities nor did they have mechanisms for receiving or sending medical personnel and medical countermeasures. The technical area in which one-third of the countries had either capacity level score 3 or 4 was risk communication. For the PoE and other IHR hazards (chemical events and radiation emergencies), no country had capacity level 5; a few had IHR capacity levels at score 3 or 4. Most countries (>80%) had an IHR capacity level at score 1 or 2 (figures 2 and 3). Finally, for illustration purposes, we present the arithmetic mean indices for the four major themes of the JEE tool (prevent, detect, respond, PoE and other IHR hazards) and the arithmetic mean for the 19 technical areas to demonstrate that a single JEE index, even without weighting, masks differences across the 19 technical areas (figure 3).

Putting the current IHR capacities status into context and perspectives for the future

Countries in the WHO African region are commended because over 80% of them have overwhelmingly embraced the JEE. Given the high burden of outbreaks and other public health emergencies, it is important that African countries use robust evidence to revise or develop their NAPHS.41 42 At the time of writing, of 40 countries that had completed a JEE, 24 had completed the revision/formulation and costing of their NAPHS, nine were in the process and five were planned. This rapid turnaround is attributed to learning lessons from the first country (ie, Tanzania) that conducted a JEE and subsequently revised their national action plan.43

There have been a few analyses of JEE data from the WHO African region.44 45 However, our paper is the most extensive documentation of the IHR (2005) capacities, covering over 80% of the countries.

Overall, these JEE findings are ‘a red flag’ about the inadequate public health emergency preparedness and response capacities in the WHO African region. This is a clarion call for the collective resolve of countries and their partners to build and sustain stronger national public health capabilities, infrastructure and processes as required under the IHR.33 Progress in IHR implementation should be monitored regularly and evaluated based on all components of the IHR monitoring and evaluation framework, including a repeat JEE every 4–5 years.37

It is clear that real-time surveillance and immunisation are the technical areas with the highest IHR capacity scores. This is not a random observation. These two programmes have been in place since the 1980s and the late 1990s for the expanded programme for immunisation and the IDSR, respectively. The IDSR strategy was adopted by the WHO African region in 1998 and has contributed to the strengthening of real-time surveillance (indicator and event-based) in human health.19–29 However, in several countries, major disparities were observed between the human and animal health sectors. Moving forward, there is a need to implement the ‘One Health Approach’.46

This analysis has revealed major gaps. First, most countries had not updated their public and animal health acts to take into consideration the broad scope of IHR (2005). Second, there was inadequate and untimely access to financial resources for the implementation of IHR (2005). Even in countries where financing was available, funds were often not accessed and distributed promptly. A third gap was the lack of resilient health systems.47 Resilient national health systems are essential for countries to prevent, detect, respond to and recover from PHEs and emergencies. Countries need to build health system resilience through the collective efforts of all relevant policymakers, stakeholders, practitioners and communities over a sustained period. A fourth major gap was inadequate multisectoral collaboration. Multisectoral and multidisciplinary coordination mechanisms are needed to facilitate efficient, alert and responsive systems for effective implementation of the IHR. This requires a functioning national IHR focal point (NFP) that is a national centre and not an individual.17 This is a key obligation of the IHR. All countries should strengthen their IHR NFP and should establish/strengthen multisectoral and multidisciplinary coordination mechanisms that integrate relevant sectors. A couple of countries are already establishing national public health institutes to play this role.

To address the above health security gaps, all countries in the WHO African region should urgently mobilise resources to support the implementation of their NAPHS. Addressing health security should be embedded into strategies for addressing universal health coverege.48 Establishing critical public health functions is a sovereign responsibility of countries, but the means to fulfil that responsibility are global. The IHR (2005) constitute the essential vehicle for that action. For long-term sustainability, funding for IHR implementation should be from domestic resources. The cost of conducting a single JEE in a country is approximately US$50 000. Therefore, the estimated cost of conducting JEEs in all 47 countries every 4–5 years in the WHO African region is US$2–3 million.

Based on cost estimates for pandemic preparedness from 24 national action plans for health security, we estimate, approximately US$ 9–10 billion is needed over the next 3 years for the whole of the WHO African region. This translates into US$ 2.50–3.50 per person per year—making the investment case for pandemic preparedness an affordable public health good. These investment needs are consistent with a 2016 global estimate of US$ 4.5 billion per year that was made by a US National Academy of Medicine commission on the global health risk framework for the future.33

Lessons learnt

The JEE is a new type of evaluation built on transparency and trust. Some of the lessons learnt during the conduct of these 41 JEEs are the following. The JEEs have been instrumental in bringing together several stakeholders from different sectors. In some countries, staff from the human and animal sectors were brought together for the first time because of the JEE. Further, security authorities were also brought on board for the first time because of the JEE.49 The JEE is helping to break down silos among human, plant, animal health, the environmental sectors and security and port authorities in ways not witnessed before. At the regional and global levels, the JEEs in the WHO African region are galvanising multiple stakeholders to work together on health security.

The JEE stimulates participatory, open debate both during the internal self-assessment and during the JEE. Because the JEE is a peer-to-peer assessment, it is essential that the JEE external team leadership ensures that all external subject matter experts especially those participating in a JEE for the first time understand this basic tenet of the JEE.

In some JEEs, participants tended to focus on a few shortcomings of the JEE tool. Like most assessment tools, the JEE tool is not perfect. The experience of the WHO African region using version 1 of the JEE tool was shared and utilised to revise the tool. Another common observation was stakeholders with ongoing projects in a given technical area tended to overscore themselves for accountability purposes, while those with projects that were winding up or projects that were not well funded tended to underscore themselves to lobby for funding. To limit these biases, it is essential for the external validation team to emphasise the need for openness and transparency in reflecting a country’s IHR capacity as truthfully as possible.

Challenges

Several challenges were observed: some related to the JEE process and others related to the tool. There are also challenges concerning the analysis and presentation of aggregate JEE indices. One of the challenges was getting the countries to conduct a JEE amidst other priorities. In some countries, there were inadequate human resources to conduct the self-assessment without external assistance.

Further, some national counterparts had inadequate understanding of the JEE process. In many instances, the JEE calendar had to be abruptly amended leading to setbacks in constituting multidisciplinary teams. However, this was eased as the rooster of JEE subject matter experts increased. Further, in some settings, instability and conflicts posed major challenges and necessitated innovative ways of conducting the validation field visits.

The JEE tool is global, and there have been situations where certain aspects of the assessment are not applicable to small states or are very challenging in countries with a federal system of government. A recent WHO technical meeting has provided recommendations on how to address these challenges without affecting the integrity of the tool.

With respect to analysis and presentation of the JEE findings, specifically, the computation of aggregate JEE indices, we believe standardisation and some form of weighting is required, depending on the hazard context. For instance, real-time surveillance has four indicators: zoonotic disease has three indicators and radiation emergencies has two indicators. Further, the hazard burden varies depending on the context. Therefore, aggregating technical area scores to generate a single or thematic JEE indices could benefit from a robust weighting scheme that is based on a ‘theory of change’ from experts in health security to avoid subjective and biased JEE indices. We plan to investigate further with experts how to standardise the computation of JEE indices. We will also explore the benefits of single or thematic aggregate JEE indices.

Conclusions

Countries in the WHO African region have shown high-level commitment to assess their IHR capacities. However, major gaps have been observed. Moving forward, all countries should harness this coalition of partners and tap into the current momentum to develop cost and implement national action plans for health security to address the gaps identified. Such plans should be implemented in synergy and alignment with broader health systems strengthening strategies. This requires the highest level of advocacy and political commitment to mobilise adequate financing. Collective action is urgently needed now to protect the people in the WHO African region from epidemics and other public health emergencies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the active participation of national experts from all the volunteering countries, the members of the international roster of experts-over 1000 of them, and the invaluable partnerships with governments including the governments of Finland, Germany and the United States; with other Intergovernmental organisations, particularly the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); many public health institutions such as the United States Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (US CDC), the Africa Centres for Disease Prevention and Control (Africa CDC), Resolve to Save Lives, the European Centres for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), the World Bank and Public Health England (PHE); private entities such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and many other partners, including the members of the Global Health Security Agenda and of the joint external evaluation (JEE) Alliance. We would like to acknowledge the continuing support and commitment of all of these to the implementation and principles of the International Health Regulations (2005). Finally, we thank the Member States for their ownership and leadership in volunteering to conduct the JEE.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: AT, AAY, SCR, MS, AO, AM, ABD, EOM, DY, FMB, RKW, NAR, RS, NK, AMR, LLB, QH, SC, ZY, ISF planned, coordinated or participated in several JEEs. AT, RKW and NK analysed that data, AT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are available with WHO and reports are available online.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa The Work of WHO in the African Region - Report of the Regional Director: 2017-2018. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273743/AFR-RC68-2-eng.pdf [Accessed 29 Aug 2018].

- 2.World Health Organisation, Regional Office for Africa . Mapping risks and the distribution of epidemics in the WHO African region, 2016; a technical report; 2016.

- 3.Changula K, Kajihara M, Mweene AS, et al. . Ebola and Marburg virus diseases in Africa: increased risk of outbreaks in previously unaffected areas? Microbiol Immunol 2014;58:483–91. 10.1111/1348-0421.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mbonye A, Wamala J, Winyi- Kaboyo, et al. . Repeated outbreaks of viral hemorrhagic fevers in Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2012;12:579–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry A, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Ali Ahmed Y, et al. . Outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, April-May, 2018: an epidemiological study. Lancet 2018;392:213–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31387-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piot P, From SJ. To 2018: reflections on early investigations into the Ebola virus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1976;2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dokubo EK, Wendland A, Mate SE, et al. . Persistence of Ebola virus after the end of widespread transmission in Liberia: an outbreak report. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:1015–24. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30417-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L, et al. . Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in guinea. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1418–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1404505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The World Bank Summary on the Ebola recovery plan: Sierra Leone, 2018. Available: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ebola/brief/summary-on-the-ebola-recovery-plan-sierra-leone [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 10.The World Bank Summary on the Ebola recovery plan: guinea, 2015. Available: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ebola/brief/summary-on-the-ebola-recovery-plan-guinea [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 11.The World Bank Summary on the Ebola recovery plan: Liberia – economic stabilization and recovery plan (ESRP), 2015. Available: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ebola/brief/summary-on-the-ebola-recovery-plan-liberia-economic-stabilization-and-recovery-plan-esrp [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 12.World Health Organisation Ebola situation reports: Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2018. Available: http://www.who.int/ebola/situation-reports/drc-2018/en/ [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 13.World Health Organisation Meningitis outbreak response in sub-Saharan Africa, who 2014; WHO/HSE/PED/CED/14.5 (WHO/HSE/PED/CED/14.5. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/144727/WHO_HSE_PED_CED_14.5_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 14.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Global humanitarian overview, 2018. Available: https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/GHO2018.PDF [Accessed 29 Aug 2018].

- 15.Satterthwaite D, Sverdlik A, Brown D. Revealing and responding to multiple health risks in informal settlements in sub-Saharan African cities. J Urban Health 2019;96:112–22. 10.1007/s11524-018-0264-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello A, Maslin M, Montgomery H, et al. . Global health and climate change: moving from denial and catastrophic fatalism to positive action. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2011;369:1866–82. 10.1098/rsta.2011.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organisation International health regulations. Third Edition, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Implementation of the international health regulations (2005): report of the review Committee on second extensions for establishing national public health capacities and on IHR implementation. Geneva: who, 2015. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/251717/1/B136_22Add1-en.pdf [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 19.World Health Organisation,, African region . Technical guidelines for integrated disease surveillance and response in the African region, 2002. Available: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/technical-guidelines-integrated-disease-surveillance-and-response-african-region-0 [Accessed 28 Aug 2018].

- 20.Nsubuga P, Brown WG, Groseclose SL, et al. . Implementing integrated disease surveillance and response: four African countries' experience, 1998-2005. Glob Public Health 2010;5:364–80. 10.1080/17441690903334943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kihembo C, Masiira B, Nakiire L, et al. . The design and implementation of the re-vitalised integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) in Uganda, 2013-2016. BMC Public Health 2018;18 10.1186/s12889-018-5755-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randriamiarana R, Raminosoa G, Vonjitsara N, et al. . Evaluation of the reinforced integrated disease surveillance and response strategy using short message service data transmission in two southern regions of Madagascar, 2014-15. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18 10.1186/s12913-018-3081-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandyata CB, Olowski LK, Mutale W. Challenges of implementing the integrated disease surveillance and response strategy in Zambia: a health worker perspective. BMC Public Health 2017;17 10.1186/s12889-017-4791-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frimpong JA, Park MM, Amo-Addae MP, et al. . Detecting, reporting, and analysis of priority diseases for routine public health surveillance in Liberia. Pan Afr Med J 2017;27 10.11604/pamj.supp.2017.27.1.12570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashbaugh HR, Kuang B, Gadoth A, et al. . Detecting Ebola with limited laboratory access in the Democratic Republic of Congo: evaluation of a clinical passive surveillance reporting system. Trop Med Int Health 2017;22:1141–53. 10.1111/tmi.12917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyatanyi T, Wilkes M, McDermott H, et al. . Implementing one health as an integrated approach to health in Rwanda. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000121 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mwengee W, Okeibunor J, Poy A, et al. . Polio eradication Initiative: contribution to improved communicable diseases surveillance in WHO African region. Vaccine 2016;34:5170–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mwatondo AJ, Ng’ang’a Z, Maina C, et al. . Factors associated with adequate Weekly reporting for disease surveillance data among health facilities in Nairobi County, Kenya, 2013. Pan Afr Med J 2016;23 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.165.8758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olu O, Usman A, Manga L, et al. . Strengthening health disaster risk management in Africa: multi-sectoral and people-centred approaches are required in the post-Hyogo framework of action era. BMC Public Health 2016;16 10.1186/s12889-016-3390-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organisation Report of the interim assessment panel, Geneva, 2015. Available: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/report-by-panel.pdf [Accessed 29 Aug 2018].

- 31.Heymann DL, Chen L, Takemi K, et al. . Global health security: the wider lessons from the West African Ebola virus disease epidemic. The Lancet 2015;385:1884–901. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60858-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon S, Sridhar D, Pate MA, et al. . Will Ebola change the game? ten essential reforms before the next pandemic. the report of the Harvard-LSHTM independent panel on the global response to Ebola. Lancet 2015;386:2204–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00946-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Academy of Health Sciences The neglected dimension of global security: a framework to counter infectious disease crises, consensus study report,; 2016. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/21891/the-neglected-dimension-of-global-security-a-framework-to-counter [PubMed]

- 34.World Health Organization Implementation of the international health regulations (2005): responding to public health emergencies. Report by the director general, document A68/22; 2018. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_22-en.pdf

- 35.Kieny MP, Dovlo D. Beyond Ebola: a new agenda for resilient health systems. The Lancet 2015;385:91–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62479-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organisation Report of the review Committee on the functioning of the international health regulations (2005) in relation to pandemic (H1N1) 2009, report by the director general, A64/10, 2011; 2018. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/wha64/a64_10-en.pdf

- 37.World Health Organisation IHR monitoring and evaluation framework. Geneva, 2018. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276651/WHO-WHE-CPI-2018.51-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 29 Dec 2018].

- 38.World Health Organisation Joint external evaluation tool: international health regulations, 2005. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204368 [Accessed 29 Aug 2018].

- 39.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Global health security Agenda/Action packages, 2014. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/pdf/ghsa-action-packages_24-september-2014.pdfl [Accessed 29 Aug 2018].

- 40.De La Rocque S, Tagliaro E, Belot G, et al. . Strengthening good governance: exploiting synergies between the performance of veterinary services pathway and the international health regulations (2005). Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE 2017;36:711–20. 10.20506/rst.36.2.2688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organisation Strategic partnership portal. country planning for health security. Available: https://extranet.who.int/spp/country-planning [Accessed 14 Aug 2018].

- 42.World Health Organisation Regional strategy for health security and emergencies 2016–2020. document AFR/RC66/6, 2016. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252834 [Accessed 29 Aug 2018].

- 43.Mghamba JM, Talisuna AO, Suryantoro L, et al. . Developing a multisectoral National Action Plan for health security (NAPHS) to implement the international health regulations (IHR 2005) in Tanzania. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000600 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta V, Kraemer JD, Katz R, et al. . Analysis of results from the joint external evaluation: examining its strength and assessing for trends among participating countries. J Glob Health 2018;8 10.7189/jogh.08.020416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oppenheim B, Gallivan M, Madhav NK, et al. . Assessing global preparedness for the next pandemic: development and application of an epidemic preparedness index. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001157 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee K, Brumme ZL. Operationalizing the one health approach: the global governance challenges. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:778–85. 10.1093/heapol/czs127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, et al. . What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. The Lancet 2015;385:1910–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erondu NA, Martin J, Marten R, et al. . Building the case for embedding global health security into universal health coverage: a proposal for a unified health system that includes public health. The Lancet 2018;392:1482–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32332-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kandel N, Sreedharan R, Chungong S, et al. . Joint external evaluation process: bringing multiple sectors together for global health security. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e857–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30264-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]