Abstract

Objective

The aetiology of thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) is largely unknown, but inflammation is likely to play a central role in the pathogenesis. In this present study, we aim to investigate the complement receptors in TAA.

Methods

Aortic tissue and blood from 31 patients with non-syndromic TAA undergoing thoracic aortic repair surgery were collected. Aortic tissue and blood from 36 patients with atherosclerosis undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery or aortic valve replacement were collected and served as control material. The expression of the complement anaphylatoxin receptors C3aR1, C5aR1 and C5aR2 in aortic tissue were examined by quantitative RT-PCR and C5aR2 protein by immunohistochemistry. Colocalisation of C5aR2 to different cell types was analysed by immunofluorescence. Complement activation products C3bc and sC5b-9 were measured in plasma.

Results

Compared with controls, TAA patients had substantial (73%) downregulated gene expression of C5aR2 as seen both at the mRNA (p=0.005) level and protein (p=0.03) level. In contrast, there were no differences in the expression of C3aR1 and C5aR1 between the two groups. Immunofluorescence examination showed that C5aR2 was colocalised to macrophages and T cells in the aortic media. There were no differences in the degree of systemic complement activation between the two groups.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest downregulation of the C5aR2, regarded to act mainly anti-inflammatory, in electively operated TAA as compared with non-aneurysmatic aortas of patients with aortic stenosis and/or coronary artery disease. This may tip the balance towards a relative increase in the inflammatory responses induced by C5aR1 and thus enhance the inflammatory processes in TAA.

Keywords: aorta, great vessels and trauma; inflammation; aortic disease; aortic valve disease

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) is characterised by progressive degradation of the aortic wall, increasing aortic diameter and increasing risk of lethal complications such as rupture and dissection.

The aetiology of TAA is largely unknown, but inflammation is likely to play central role in the pathogenesis.

What does this study add?

The present study showed a marked highly specific downregulation of the anti-inflammatory C5aR2 in TAA patients both at the mRNA level and as protein immunostaining, without any changes in C3aR1 and C5aR1, compared with atherosclerotic non-aneurysmatic controls.

C5aR2 colocalised with T cells and macrophages in the media of patients with TAA. Protein immunostaining data suggest that the downregulation of C5aR2 in TAA does not merely reflect downregulation of the C5aR2 expressingT cells or macrophages.

No systemic complement system activation in patients with TAA.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

C5aR2 downregulation may tip the balance towards a relative increase in the inflammatory responses induced by C5aR1 and thus enhance the inflammatory processes in TAA.

These data have implications for understanding the pathophysiology of TAA, and probably pave the way for future prevention and treatment of this serious condition.

Introduction

Thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) is characterised by progressive degradation of the aortic wall, increasing aortic diameter and increasing risk of lethal complications such as rupture and dissection, but the causes of TAA dilation are at present not fully understood.1 Genetic factors are definitively of importance in syndromic aortic aneurysmatic disease (eg, Loeys-Dietz and Marphan syndrome) and can also contribute to non-syndromic TAA.2 Atherosclerosis is a well-established risk factor of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), but only a small proportion of patients with aortic atherosclerosis develop aneurysm, pointing towards overlapping as well as specific mechanisms in these two conditions.3 Moreover, whereas atherosclerosis has been established as a risk factor in the development of AAA, its role in TAA is unclear.4 5

The complement system is a part of the innate immune system, and serves as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity, as well as between inflammation and coagulation,6 a cross-talk termed thromboinflammation.7 Whereas the complement system is important in tissue homostasis and immune surveillance,8 overwhelming or persistent activation of complement may contribute to tissue destruction and chronic inflammation. Indeed, the complement system seems to play a pathogenic role in various inflammatory conditions such as sepsis9 10 and various autoimmune diseases.11 Enhanced complement activation seems also to play a pathogenic role in several cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis.12

C3a and C5a are small activation products of the complement cascade, frequently called anaphylatoxins, released when C3 and C5 are activated. They contribute to the regulation of local inflammatory responses, mainly by inflammatory effects, but seem also to have anti-inflammatory properties. Their effects are mainly mediated through activation of complement receptors, a group of G protein-coupled receptors,13 14 termed C3aR, C5aR1 and C5aR2. The complement receptor C5aR2, previously called C5L2, was discovered much later than the others. Thus, the function of this receptor is not fully elucidated and there has been controversies regarding its main function from being a scavenger receptor neutralising C5a to recent evidence suggesting that C5a/C5aR2 is signalling through mechanisms different from C5aR1.15 16 It has in fact gradually become evident that the C5aR2 is mainly an anti-inflammatory receptor.17 18

Although there is some data on complement expression in human AAA,19 data on the complement system in TAA is scarce. To elucidate a possible role for complement activation in the pathogenesis of TAA, we examined the expression of the complement anaphylatoxin receptors in the aorta of atherosclerotic patients with and without TAA.

Methods

Study population

Patients undergoing elective TAA repair surgery at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway were included. Biopsies from 31 aneurysmal and 36 non-aneurysmal atherosclerotic aortas (controls) were collected intraoperatively (table 1). Non-aneurysmal aortic samples were collected from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or aortic valve replacement (AVR) surgery at the same department. The mean aortic diameters of aneurysmal aortas were 5.6±0.8 cm compared with 3.4±0.6 in controls. Both patients with tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves were included. Patients with aneurysms secondary to known genetic disease (e.g. Marfan syndrome), due to other causes (e.g. aortitis), and patients with malignant disease were excluded.

Table 1.

Characteristics of controls and patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA)†

| Controls (n=36) |

TAA patients (n=31) |

||

| Aortic diameter (cm)‡ | 3.4±0.6 | 5.6±0.8 | *** |

| EARD§ | 3.6±0.2 | 3.6±0.2 | ns |

| Men / Women | 75 % / 25% | 77 % / 23% | ns |

| Age, y | 67.4±9.1 | 62.8±11.6 | ns |

| Weight, kg | 84.0±16.0 | 88.3±18.1 | ns |

| Height, cm | 175±7 | 179±9 | ns |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Diabetes type 1/type 2 | 6 % / 22% | 0 % / 6% | ns |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 31% | 13% | ns |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 136±18 | 135±12 | ns |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 76±10 | 75±12 | ns |

| Medical history | |||

| Heart failure | 14% | 13% | ns |

| Aortic stenosis | 33% | 39% | ns |

| Coronary artery disease | 81% | 10% | *** |

| Atherosclerosis of carotid arteries | 11% | 3% | ns |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 8% | 0% | ns |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6% | 16% | ns |

| Kidney disease (Creatinine >100) | 14% | 6% | ns |

| Clinical chemistry (preoperative) | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/100 mL) | 13.6±1.7 | 14.1±2.7 | ns |

| Thrombocytes (×10⁹/L) | 240±49 | 243±73 | ns |

| Leucocytes (×10⁹/L) | 7.4±2.2 | 7.2±1.9 | ns |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 6.93±10.6 | 3.5±3.9 | ns |

| Medication (preoperative) | |||

| ACE inhibitors | 17% | 26% | ns |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 25% | 29% | ns |

| Beta-blockers | 67% | 39% | * |

| Statins | 72% | 23% | *** |

| Aspirin | 83% | 29% | *** |

*p<0.05 versus non-aneurysmal aorta, ***p<0.0001 versus non-aneurysmal aorta.

†Data are mean±SD or % of total.

‡Aortic diameters were not available for 10/36 control patients.

§Estimated aortic root dimension (EARD) based on height, formula adapted from Devereux etal: 1.519+(age [yrs]*0.010)+(ht [cm]*0.010)−(sex [1=M, 2=F]*0.247) SEE = EARD.39

Tissue and blood sampling

Full thickness wall biopsies were collected, one part frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA analysis, and the other part kept on 4% formalin for immunohistochemistry. Owing to shortage of tissue materials, not all analyses were performed in all individuals. Preoperative arterial blood samples were collected in sterile EDTA tubes, placed on melting ice, centrifuged within 30 min at 2000×g for 20 min to obtain platelet-poor plasma, before storing in multiple aliquots at −80°C. Samples for complement analyses were thawed only once.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded 5 µm thick sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated, blocked with 3% H2O2, followed by high-temperature epitope retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6). Sections were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) two times and blocked with PBS/0.5% bovine serum albumin/0.1% Tween 20, before 1-hour incubation with primary antibody at room temperature. Slides were stained with the following primary antibodies; mouse anti-human smooth muscle α-actin (1:200, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), mouse anti-human CD68 (1:200, DAKO), rabbit anti-human CD3 (1:50, DAKO) and rabbit anti-human C5aR2 (1:50, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (online supplementary material table S1). After washing in PBS, slides were incubated for 1 hour with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (online supplementary material table S2), both from ImmPRESS (Burlingame, CA). 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit (SK-4100, ImmPRESS) was used for visualisation. To ensure specific staining, a staining without primary antibody was carried out and served as a negative control. Stained sections were scanned and uploaded to z9.nird.sigma2.no, an in-house made application for evaluation and quantitative examination of histological sections. Areal positive staining for smooth muscle α-actin, CD3, CD68 and C5aR2 in the aortic media was quantified relative to total tissue area, based on colorimetric thresholding of the DAB staining in the HSV colour space.

openhrt-2019-001098supp001.pdf (49.7KB, pdf)

Immunofluorescence

Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded 5 µm thick sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated, blocked with BLOXALL (SP-6000, Vector labs, Burlingame, California, USA) and treated with citrate buffer (pH 6) to retrieve epitopes. Sections were rinsed in tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) two times, blocked with 2.5% normal goat serum plus 2.5% normal horse serum (S-1012 and S-2012, Vector labs), and incubated with the following primary antibodies; rat anti-mouse/human Mac-2 (1:600, Cedarlane, Burlington, Canada), rabbit anti-human αSMA (1:200, Abcam) and rabbit anti-human CD3 (1:50, Abcam) at room temperature for 1 hour. Rat-on-mouse AP-Polymer (RT518H, Biocare Medical, Pacheco, California, USA) was used for sections stained with anti-Mac-2, according to manufacturer’s recommendations. ImmPRESS AP reagent kit (anti-rabbit, MP-5401) was used for sections stained with anti-αSMA and anti-CD3, according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

For visualisation, ImmPACT Vector Red-kit (SK-5105, Vector labs) was used, according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Sections were further treated with citrate buffer for 10 min, blocked with 2.5% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature and incubated with rabbit anti-human C5aR2 (1:20, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Sections were rinsed in three changes of PBS and incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies (1:500, Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon, USA) at room temperature for 1 hour. To ensure specific staining, staining without primary antibody was carried out and served as a negative control. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in a mounting solution (P36931 ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI, Invitrogen). To assess which cell types C5aR2 colocalised with, sections were evaluated in a qualitative manner by a blinded observer. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope (63×1.4 plan-apochromat objective, single plane) (Oberkochen, Germany). Images were analysed by Zeiss software.

mRNA quantification

Total RNA was extracted from aortic tissue using RNeasy Mini Columns (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA by using the qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA). Reverse transcription of RNA was performed with GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster By, California, USA), and cDNA was stored at –20°C. Quantification of gene expression was performed in duplicate by quantitative real-time PCR using Taqman probes (See online supplementary material table S3). Gene expression was normalised against EIF2β1, a gene highly suitable for TAA materials,20 and relative gene expression calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt-method.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA used to quantify C3bc and soluble terminal complement complex (TCC/C5b-9) in plasma was performed as described by Bergseth et al.21

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism V.7.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) was used for data analysis. Comparison between two groups of individuals was performed using Mann-Whitney U test to compare ranks. ROUT outlier test, which is a robust test for defining and excluding outlieres,22 (Q=0.1%) was used to remove definite outliers. Patient characteristics were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.24 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). t-Test was used for comparisons of continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for statistical analysis of categorical variables. Data are shown in graphs as mean±SEM. A p value below 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistical significant.

Results

Gene expression of C5aR2 is downregulated in thoracic aortic aneurysms

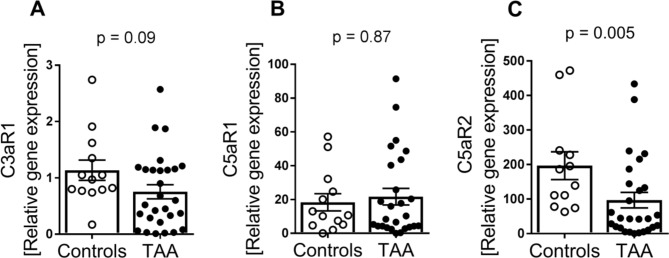

We first investigated the gene expression of the three complement anaphylatoxin receptors, C3aR1, C5aR1 and C5aR2, in patients with ascending TAA (n=28) compared with controls (n=13). Whereas there was no difference in mRNA levels of C5aR1 (p=0.87) or C3aR (p=0.09) between the two patient groups (figure 1A,B), mRNA levels of C5aR2 was markedly decreased in TAA compared with controls (figure 1C, 73% decrease, p=0.005).

Figure 1.

Gene expression of C3aR1, C5aR1 and C5aR2 in TAA compared with controls. Gene expression of (A) C3aR (controls, n=13; TAA, n=28), (B) C5aR1 (controls, n=13; TAA, n=26) and (C) C5aR2 (controls, n=12; TAA, n=27) in aortic tissue from controls versus TAA. Gene expression was normalised to the reference gene EIFβ2. Data are shown as individual measurements with mean (horizontal line) and SEM (error bars). P values were determined by Mann-Whitney U test. TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Lower aortic protein levels of C5aR2 in patients with TAA

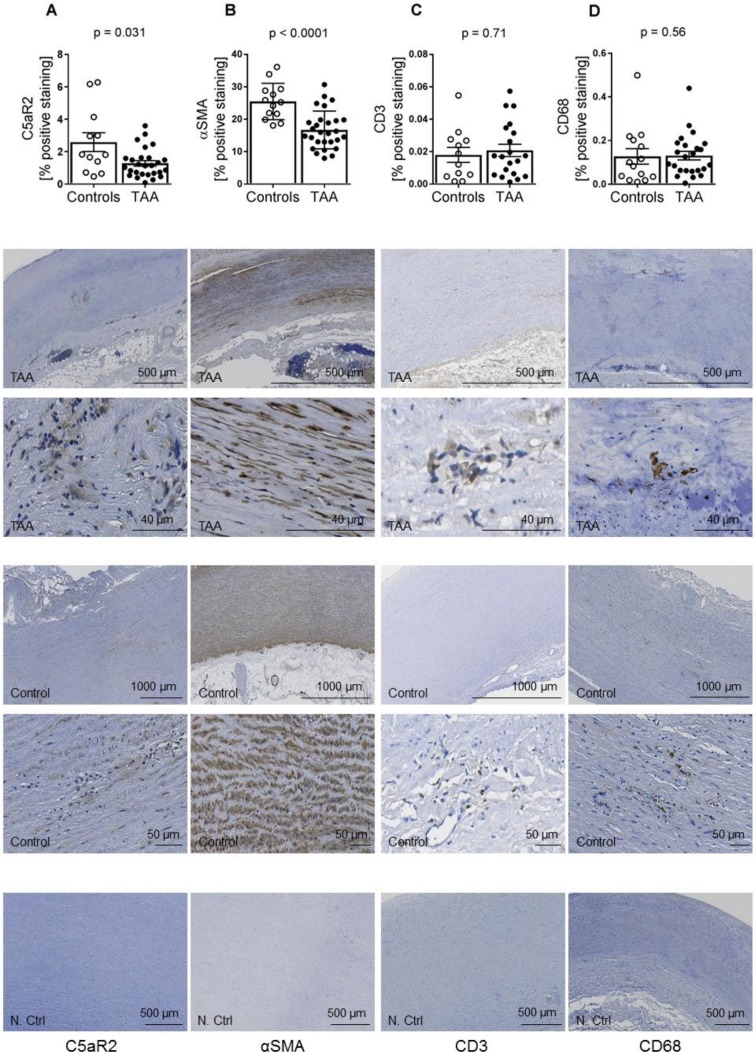

Immunostaining revealed C5aR2 staining in the aortic media, aortic adventitia and aortic plaques, with lower levels of C5aR2 in TAA, as compared with controls (figure 2A, p=0.031). Also, levels of αSMA expressing cells in the aortic media of TAA patients were lower compared with controls (figure 2B, p<0.001). In contrast, although there were large inter-individual differences, there were no differences between the two groups in relation to amount of T-cells (CD3-expressing cells) or macrophages (CD68 expressing cells) in the aortic media (figure 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Immunostaining of C5aR2, αSMA, CD3 and CD68 in aortic media of TAA patients compared with controls. Amount of positive immunostaining of (A) C5aR2 (controls, n=12; TAA, n=27), (B) αSMA (controls, n=13; TAA, n=28), (C) CD3 (controls, n=12; TAA, n=20) and (D) CD68 (controls, n=14; TAA, n=24) in aortic media of controls versus TAA. Data are shown as individual measurements with mean (horizontal line) and SEM (error bars). Representative images of different sections from TAA are shown in the lower panels. TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

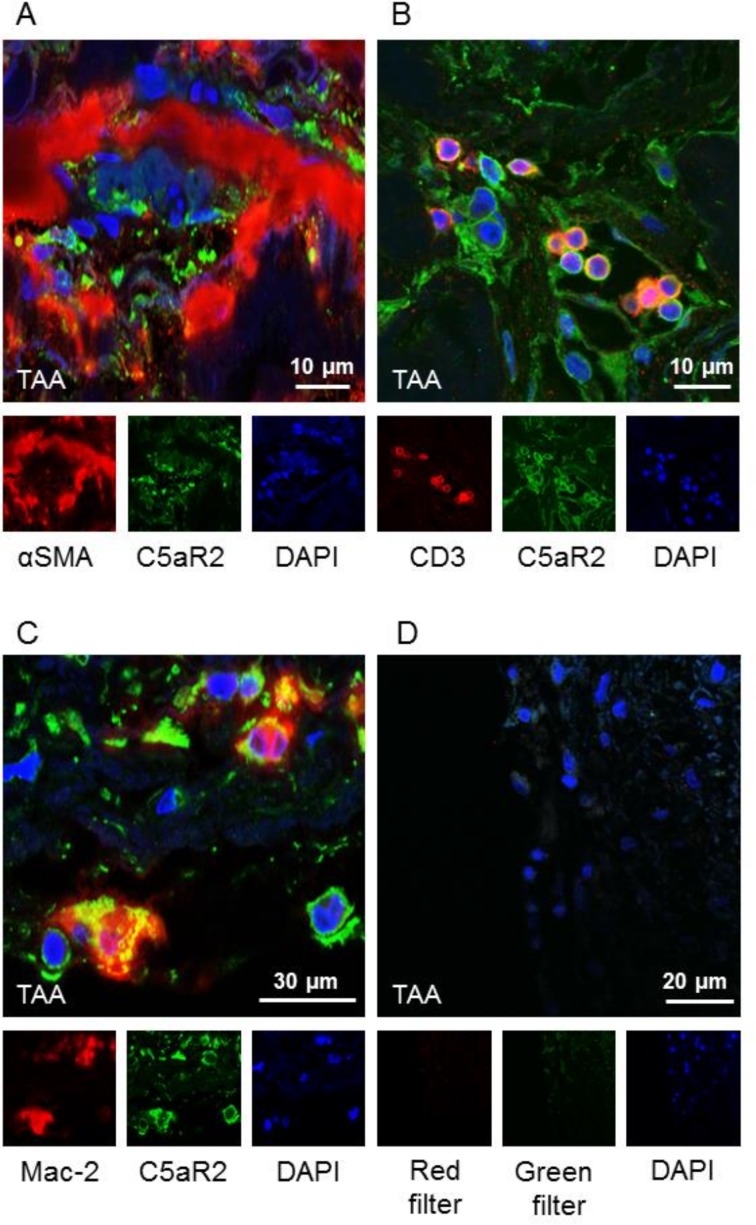

C5aR2 colocalised with T cells and macrophages in the media of patients with TAA

We selected sections from five TAA patients and five controls for immunofluorescence staining, to visualise to which cells C5aR2 colocalised in the aortic wall. C5aR2 showed a clear intracellular colocalisation with macrophages (Mac-2) and T cells (CD3) within the aortic wall of TAA patients and controls (figure 3).

Figure 3.

C5aR2 colocalised with T cells and macrophages in the media of patients with TAA. Immunofluorescence staining of (A) C5aR2 and αSMA, (B) C5aR2 and CD3, (C) C5aR2 and Mac-2. C5aR2 showed a clear intracellular colocalisation with (B) T cells (CD3) within the aortic wall and (C) macrophages (Mac-2). There was no colocalisation with (A) smooth muscle cells. Representative images of immunofluorescence different sections from aortic wall are shown. TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

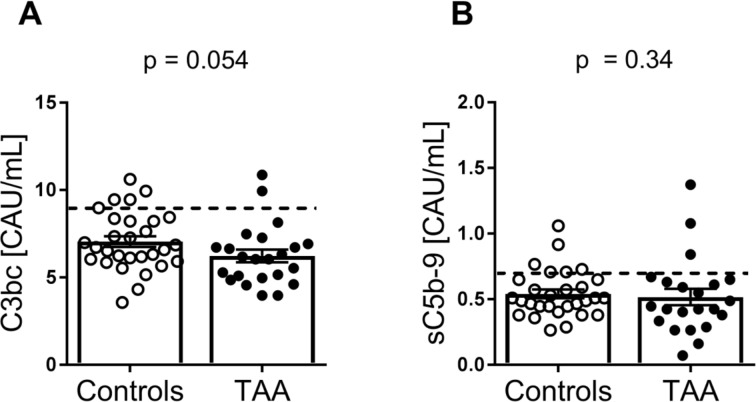

No systemic complement system activation in patients with TAA

Finally, we examined systemic complement activation by measuring C3bc and sC5b-9 in the two groups (controls n=29, TAA n=23). There were no differences in systemic complement activation in the two groups, C3bc (p=0.054) and sC5b-9 levels (p=0.34), and most of the values were within normal limits (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Plasma levels of complement activation products C3bc and sC5b-9 in patients with TAA patients compared with controls. Amount of (A) C3bc (controls, n=29; TAA, n=23) and (B) sC5b-9 (controls, n=29; TAA, n=22) in plasma in controls versus TAA. Data show individual measurements with mean (horizontal line) and SEM (error bars). P values were determined by Mann-Whitney U test. The dotted line represents the upper normal threshold values, C3bc: 9 CAU/mL, sC5b-9: 0.7 CAU/mL.21 TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Discussion

In the present study we observed a strikingly specific and substantial reduction in the expression of the complement receptor C5aR2, known to signal mainly anti-inflammatory,17 18 in the aortic wall of TAA. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first time an imbalance in the expression of the complement receptors has been documented in TAA. Given that C5a is important in the pathogenesis of TAA, the reduced expression of C5aR2 combined with a fully preserved C5aR1 expression, might diverge the response into an enhanced inflammatory state, since the C5a-C5aR1 axis is a very potent proinflammatory signalling system.

It is not fully understood what causes dilatation of the thoracic aorta, but there is increasing evidence for the role of chronic inflammation in TAA.23 The complement system is an important arm of the innate immune system, and is capable of producing both local and systemic inflammation. A role of complement in AAA has been suggested in various studies,19 24 whereas the impact of complement in TAA is not clear. In this study we investigated the expression of complement anaphylatoxin receptors in human TAA. We found a markedly decreased gene and protein expression of C5aR2 in TAA as compared with non-aneurysmatic atherosclerotic aortas, without any differences in C3aR and C5aR1 between the two groups. This highly specific C5aR2 reduction is clearly of interest. Although the function of C5aR2 is still controversial and the functional consequences of downregulation of this receptor in human TAA are at present not clear, there are increasing evidence that C5aR2 is mainly an anti-inflammatory signalling receptor.17 18 Our data could therefore indicate an increased inflammatory load in TAA involving complement activation as potential mediator.

There are a few other studies on complement receptors in thoracic aortic dilatation and dissection. Ren et al has reported systemic complement activation and upregulation of C3aR in human TAA suggesting that the C3a-C3aR1 axis promotes TAA rupture.25 However, their control groups consisted of plasma from healthy volunteers and aortic tissue from patients undergoing heart transplantation without any additional information on the presence of atherosclerosis. Moreover, the samples were taken during dissection just prior to rupture. It is not inconceivable that the complement system is more activated during dissection as compared with the chronic phase of aortic dilatation.

The role of the C5a-C5aR2 axis in TAA has not previously described. As mentioned, the role of C5aR2 is still controversial. In experimental models of allergic contact dermatitis and LPS and immune complex induced lung injury, C5aR2 deficiency exacerbates inflammation and tissue injury,26 27 whereas an opposite pattern is seen in experimental allergic asthma, acute colitis and sepsis, where depletion of C5aR2 alleviates the pathological symptoms and inflammation.28–30 In atherosclerosis, however, C5aR2 seems to have inflammatory properties. Vijayan et al has shown that in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques high expression of C5aR2 correlates with high levels of inflammatory cytokines.31 In apolipoprotein E-deficient mice Selle et al has demonstrated an atheroprotective role of C5aR2 deficiency.32 Given the differences between AAA and TAA, and not least between atherosclerosis and TAA, these data should be interpreted with great caution with respect to their relevance for the pathophysiology of TAA.

Cystic medial degeneration with loss of smooth muscle cells is a histological hallmark of TAA which is also seen in the present study.33 He et al described the inflammatory infiltrate in aneurysmal thoracic aorta, which contains CD3+ and CD68+ cells,34 and a similar pattern was also found in the media of TAA patients in our material. However, the immune cell infiltration did not differ from samples obtained from non-aneurysmatic atherosclerotic thoracic aortas, underscoring the need for appropriate controls when studying non-syndromic TAA. Interestingly, however, C5aR2 in media of TAA patients were colocalised with T cells and macrophages showing intracellular localisation in both cell types, as also have been reported by others in others in various tissues.35 Verghese et al have recently reported that C5aR2 augment the activation of regulatory T cells promoting cardiac allograft survival in an experimental mouse model, supporting an anti-inflammatory role of C5aR2 also within the T cell population.36 Finally, and most importantly, our colocalisation data suggest that the downregulation of C5aR2 in TAA does not merely reflect downregulation of the C5aR2 expressing cells (i.e. T cells and macrophages).

We have included patients from the largest department of cardiothoracic surgery in Norway, and the population is a relevant TAA-group regarding gender, age and important aortic size determinants such as weight and height in comparison to other TAA cohorts.37 However, there are some important limitations of the current study. Our study population was relatively small and all patients were selected from a patient population that was electively operated at the lower, recommended aortic diameter.38 The data could therefore not without limitations be interpreted as representative for more advanced TAA including those undergoing dissection and rupture.

In conclusion, our findings document downregulation of C5aR2 in electively operated TAA as compared with non-aneurysmatic aortas, from patients undergoing AVR and/or CABG. Although the function of C5aR2 is still under debate, the recent data pointing to this receptor as an anti-inflammatory receptor indicate that the functional consequences of C5aR2 downregulation in TAA may enhance the inflammatory effects induced by C5aR1, which was preserved in the TAA lesion.

Footnotes

MCL and TR contributed equally.

Contributors: MH, PHN, TEM, PA, AY, TR: conception and design of research. MH, BES, PRW: material collection. MH, PHN, MBO, TR: performed experiments. MH, JØ, MBO, PHN, PA, TEM, AY, MCL, TR: analysis and interpretation. MH, MCL, TR: prepared figures. MFH, JØ, PRW, J-PEK, AY, PA, TEM, PHN, MCL, TR: drafted manuscript. MH, PA, MCL, TR: edited and revised manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by research grants from The Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Disease and The Odd Fellow Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Informed written consents for participation were received from all individuals.

Ethics approval: The collection of human tissue and blood was approved by Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC nr: 2014/906) and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: a report of the American College of cardiology Foundation/American heart association Task force on practice guidelines, American association for thoracic surgery, American College of radiology, American stroke association, society of cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, society of interventional radiology, society of thoracic surgeons, and Society for vascular medicine. Circulation 2010;121:e266–369. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d4739e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownstein A, Kostiuk V, Ziganshin B, et al. Genes associated with thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: 2018 update and clinical implications. AORTA 2018;06:013–20. 10.1055/s-0038-1639612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palazzuoli A, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008;4:877–83. 10.2147/VHRM.S1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toghill BJ, Saratzis A, Bown MJ, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm—an independent disease to atherosclerosis? Cardiovascular Pathology 2017;27:71–5. 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito S, Akutsu K, Tamori Y, et al. Differences in atherosclerotic profiles between patients with thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:696–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkelberger JR, Song W-C. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res 2010;20:34–50. 10.1038/cr.2009.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekdahl KN, Teramura Y, Hamad OA, et al. Dangerous liaisons: complement, coagulation, and kallikrein/kinin cross-talk act as a linchpin in the events leading to thromboinflammation. Immunol Rev 2016;274:245–69. 10.1111/imr.12471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, et al. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol 2010;11:785–97. 10.1038/ni.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward PA, Gao H, Sepsis GH. Sepsis, complement and the dysregulated inflammatory response. J Cell Mol Med 2009;13:4154–60. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00893.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skjeflo EW, Sagatun C, Dybwik K, et al. Combined inhibition of complement and CD14 improved outcome in porcine polymicrobial sepsis. Crit Care 2015;19 10.1186/s13054-015-1129-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen M, Daha MR, Kallenberg CGM. The complement system in systemic autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun 2010;34:J276–86. 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lappegård KT, Garred P, Jonasson L, et al. A vital role for complement in heart disease. Mol Immunol 2014;61:126–34. 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarma JV, Ward PA. New developments in C5a receptor signaling. Cell Health Cytoskelet 2012;4:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng Q, Li K, Sacks S, et al. The role of anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2009;8:236–46. 10.2174/187152809788681038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemper C. Targeting the dark horse of complement: the first generation of functionally selective C5aR2 ligands. Immunol Cell Biol 2016;94:717–8. 10.1038/icb.2016.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li R, Coulthard LG, Wu MCL, et al. C5L2: a controversial receptor of complement anaphylatoxin, C5a. The FASEB Journal 2013;27:855–64. 10.1096/fj.12-220509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croker DE, Monk PN, Halai R, et al. Discovery of functionally selective C5aR2 ligands: novel modulators of C5a signalling. Immunol Cell Biol 2016;94:787–95. 10.1038/icb.2016.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbore G, West EE, Spolski R, et al. T helper 1 immunity requires complement-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activity in CD4+ T cells. Science 2016;352:aad1210 10.1126/science.aad1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinterseher I, Erdman R, Donoso LA, et al. Role of complement cascade in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31:1653–60. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henn D, Bandner-Risch D, Perttunen H, et al. Identification of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR in ascending aortic aneurysms. PLoS One 2013;8:e54132 10.1371/journal.pone.0054132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergseth G, Ludviksen JK, Kirschfink M, et al. An international serum standard for application in assays to detect human complement activation products. Mol Immunol 2013;56:232–9. 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.05.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC Bioinformatics 2006;7:123 10.1186/1471-2105-7-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisano C, Balistreri CR, Ricasoli A, et al. Cardiovascular disease in ageing: an overview on thoracic aortic aneurysm as an emerging inflammatory disease. Mediators Inflamm 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/1274034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez-García C-E, Burillo E, Lindholt JS, et al. Association of ficolin-3 with abdominal aortic aneurysm presence and progression. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15:575–85. 10.1111/jth.13608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren W, Liu Y, Wang X, et al. The Complement C3a-C3aR Axis Promotes Development of Thoracic Aortic Dissection via Regulation of MMP2 Expression. J Immunol 2018;200:ji1601386–38. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang R, Lu B, Gerard C, et al. Disruption of the complement anaphylatoxin receptor C5L2 exacerbates inflammation in allergic contact dermatitis. J.i. 2013;191:4001–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Lu B, Gerard C, et al. C5L2, the second C5a anaphylatoxin receptor, suppresses LPS-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016;55:657–66. 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0067OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Nadeau BA, et al. Functional roles for C5a receptors in sepsis. Nat Med 2008;14:551–7. 10.1038/nm1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu W-C, Yang F-C, Lin C-H, et al. C5L2 is required for C5a-triggered receptor internalization and ERK signaling. Cell Signal 2014;26:1409–19. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Schmudde I, Laumonnier Y, et al. A critical role for C5L2 in the pathogenesis of experimental allergic asthma. J.i. 2010;185:6741–52. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vijayan S, Asare Y, Grommes J, et al. High expression of C5L2 correlates with high proinflammatory cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol 2014;184:2123–33. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selle J, Asare Y, Köhncke J, et al. Atheroprotective role of C5ar2 deficiency in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Thromb Haemost 2015;114:848–58. 10.1160/TH14-12-1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu D, Ren P, Zheng Y, et al. NLRP3 (Nucleotide Oligomerization Domain-Like Receptor Family, Pyrin Domain Containing 3)-Caspase-1 Inflammasome Degrades Contractile Proteins: Implications for Aortic Biomechanical Dysfunction and Aneurysm and Dissection Formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:694–706. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He R, Guo D-C, Sun W, et al. Characterization of the inflammatory cells in ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms in patients with Marfan syndrome, familial thoracic aortic aneurysms, and sporadic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;136:922–9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichhardt MP, Meri S. Intracellular complement activation—An alarm raising mechanism? Semin Immunol 2018;38:54–62. 10.1016/j.smim.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.A Verghese D, Demir M, Chun N, et al. T Cell Expression of C5a Receptor 2 Augments Murine Regulatory T Cell (TREG) Generation and TREG-Dependent Cardiac Allograft Survival. J Immunol 2018;200:2186–98. 10.4049/jimmunol.1701638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung K, Boodhwani M, Chan Kwan‐Leung, et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysm growth: role of sex and aneurysm etiology. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6 10.1161/JAHA.116.003792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, et al. What is the appropriate size criterion for resection of thoracic aortic aneurysms? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;113:476–91. 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70360-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devereux RB, de Simone G, Arnett DK, et al. Normal limits in relation to age, body size and gender of two-dimensional echocardiographic aortic root dimensions in persons ≥15 years of age. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1189–94. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2019-001098supp001.pdf (49.7KB, pdf)