Abstract

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1 and PARP-2 regulate the function of various DNA-interacting proteins by transferring ADP-ribose emerging from catalytic cleavage of cellular β-NAD+. Hence, mice lacking PARP-1 or PARP-2 show DNA perturbations ranging from altered DNA integrity to impaired DNA repair. These effects stem from the central role that PARP-1 and PARP-2 have on the cellular response to DNA damage. Failure to mount a proper response culminates in cell death. Accordingly, PARP inhibitors are emerging as promising drugs in cancer therapy. However, the full impact of these inhibitors on immunity, including B-cell antibody production, remains elusive. Given that mice carrying dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency develop early embryonic lethality, we crossed PARP-1-deficient mice with mice carrying a B-cell-conditional PARP-2 gene deletion. We found that the resulting dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice had perturbed bone-marrow B-cell development as well as profound peripheral depletion of transitional and follicular but not marginal zone B-cells. Of note, bone-marrow B-cell progenitors and peripheral mature B-cells were conserved in mice carrying either PARP-1 or PARP-2 deficiency. In dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice, B-cell lymphopenia was associated with increased DNA damage and accentuated death in actively proliferating B-cells. Moreover, dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency impaired antibody responses to T-independent carbohydrate but not to T-dependent protein antigens. Notwithstanding the pivotal role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in DNA repair, combined PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency did not perturb the DNA-editing processes required for the generation of a protective antibody repertoire, including Ig V(D)J gene recombination and IgM-to-IgG class switching. These findings provide key information as to the potential impact of PARP inhibitors on humoral immunity, which will facilitate the development of safer PARP-targeting regimens against cancer.

Subject terms: Immune cell death, Cell biology

Introduction

B-cell development is a highly regulated process that involves bone-marrow differentiation of pluripotent hematopoietic stem-cells into pro-B-cells. These early recombination-activating gene (RAG)-positive B-cell precursors sequentially undergo RAG-dependent immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy-chain gene rearrangements to assemble a VHDJH-Cμ protein that associates with Vpre-B and λ5 surrogate light chain proteins to form a pre-BCR complex. Signaling through the pre-BCR stimulates the progression of RAG-negative pre-B-cells into RAG-positive immature B-cells that undergo RAG-dependent Ig light chain VLJL gene rearrangement. Subsequent association of VLJL with VHDJH-Cμ generates fully functional membrane-bound IgM receptors in immature B-cells, which further differentiate into transitional B-cells that progressively co-express IgM and IgD receptors [1]. These transitional B-cells migrate to peripheral secondary lymphoid organs, where they further progress into mature marginal zone (MZ) or follicular (FO) B-cells [1]. This fate decision requires specific signals from B-cell-receptor and NOTCH-receptor among other signaling pathways [2, 3]. Upon antigen exposure, mature B-cells become activated and enter Bcl-6− extrafollicular or Bcl-6+ germinal center differentiation programs that lead to the formation of short-lived antibody-secreting plasmablasts or long-lived memory B-cells and antibody-secreting plasma cells, respectively [4–6].

Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP)-1 and PARP-2 belong to a family of enzymes that cleave β-NAD+ to transfer ADP-ribose moiety onto residues of proteins [7, 8]. Mice lacking either PARP-1 or PARP-2 show alterations of DNA integrity and repair, which supports the notion that these enzymes share functional properties that are pivotal to DNA repair [9]. Accordingly, combined PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency is embryonically lethal [10], which is likely due to their central role in the DNA damage response (DDR) [7, 9]. Remarkably, PARP-1 and PARP-2 deploy additional functions beyond DDR, including gene transcription, angiogenesis, and cell death [9]. In all these processes, PARP-1 and PARP-2 target distinct acceptor proteins, suggesting that these enzymes have discrete biological roles [11, 12]. For instance, PARP-2 but not PARP-1 regulates hematopoiesis [13, 14], spermatogenesis [15], and T-cell development [16, 17]. More recently, we elucidated a coordinated role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in T-cell homeostasis [18].

In contrast, the function of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in B-cells remains elusive. Importantly, the mature B-cell compartment appears conserved in peripheral lymphoid organs from either PARP-1 or PARP-2-deficient mice [17, 18]. Given the key role of PARP-1 or PARP-2 in DNA repair, these enzymes could regulate DNA-editing processes implicated in the generation of antibody diversity. Yet, the role of PARP-1 or PARP-2 in Ig V(D)J gene recombination remains unclear or unknown [19–21]. Moreover, neither PARP-1 nor PARP-2 seems required for class-switch DNA recombination (CSR) [22].

Here, we bypassed the early embryonic lethality of dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice [10] by crossing PARP-1-deficient mice with Cd19-cre mice carrying a B-cell-conditional PARP-2 deletion. We found that combined but not individual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency impaired B-cell development and function, including antibody responses to T-independent (TI) antigens but not T-dependent (TD) antigens. Despite the crucial role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in DDR, PARP-1 and PARP-2 were dispensable for both Ig V(D)J gene recombination and Ig CSR. By elucidating the role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in B-cells, our findings provide essential information that may impact for the development of PARP-centered therapies.

Results

Generation of PARP-1-deficient mice with B-cell-specific PARP-2 deletion

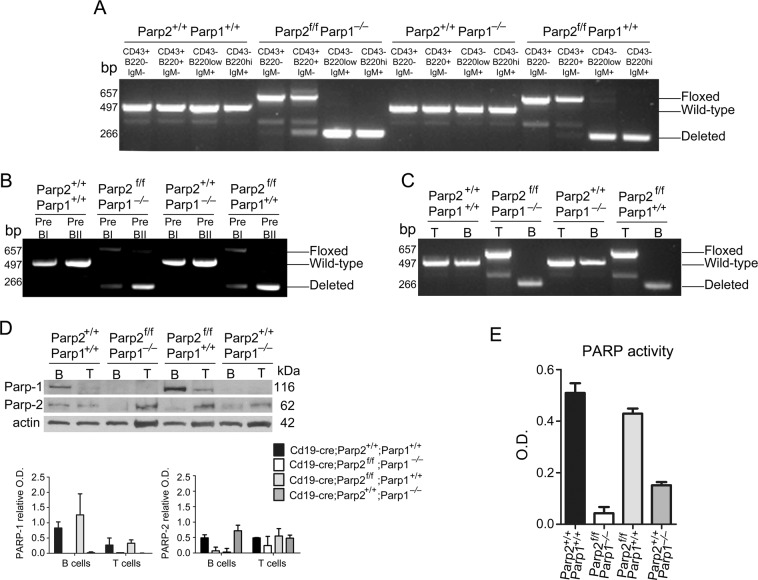

To study the function of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in B-cells, we crossed mice harboring the floxed Parp-2-allele (Parp-2f/f) [18] with mice expressing the Cre-recombinase under the control of the Cd19-promoter (Cd19-cretg/tg) [23]. The resulting Cd19-cretg/+Parp-2f/+ mice were crossed with Parp-1−/− mice to generate heterozygous mice that were backcrossed to give all possible combinations of targeted alleles. Only mice with Cd19-cre in heterozygosis were used in these studies. To check the efficiency of Cre-mediated PARP-2 deletion in Cd19 expressing B-cells, the floxed allele was PCR amplified from FACSorted bone-marrow and spleen cell subsets. Loss of the floxed allele started in CD43+B220+IgM− (fraction A-C′) bone-marrow cells and was complete in later development stages (Fig. 1a). Indeed, a complete loss of the floxed allele takes place at pre-BII stage (Fig. 1b). Similarly, loss of the floxed allele was observed in splenic B but not T cells (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Effectiveness of PARP-2 deletion in Cd19-cre;Parp-2f/f mice. a–c PCR analysis from genomic DNA in sorted bone-marrow (a, b) and splenic (c) B-cell subsets from mice of the indicated genotypes. Pre-BI cells (B220+CD19+IgM−CD25−CD117+); Pre-BII cells (B220+CD19+IgM-CD25+CD117−); T cells (CD3+); B-cells (B220+) d western-blot analysis of PARP-1 and PARP-2 proteins expression in splenic B and T cells from mice of the indicated genotypes. Expression of β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis (optical density) of PARP-1 and PARP-2 bands from western blotting is shown. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM using samples from two different mice of each genotypes. e PARP activity in protein extracts from B-cells upon activation with LPS. Resting B-cells were isolated from spleen, cultured in the presence of LPS (10 µg/ml) for 2.5 days, lysed and PARP activity determined in protein extracts. Results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate

We also analyzed PARP-1 and PARP-2 protein expression in FACSorted splenic B and T cells from control (Cd19-creParp-2+/+Parp-1+/+), single PARP-1-deficient (Cd19-creParp-2+/+Parp-1−/−), single PARP-2-deficient (Cd19-creParp-2f/fParp-1+/+), and dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient (CD19-creParp-2f/fParp-1−/−) mice. We found loss of PARP-2 in B-cells but not T cells from Cd19-creParp-2f/f mice (Fig. 1d). Upon in vitro activation with LPS, PARP activity was only slightly reduced in single PARP-2-deficient B-cells compared to controls, whereas a stronger reduction was observed in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient B-cells. PARP activity was sharply reduced in PARP-1-deficient B-cells but to a lesser extent than in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient B-cells (Fig. 1e). Thus, our strategy efficiently generated mice with combined global PARP-1 deficiency and B-cell-specific PARP-2 deficiency.

PARP-1 and PARP-2 are required for normal B-cell development

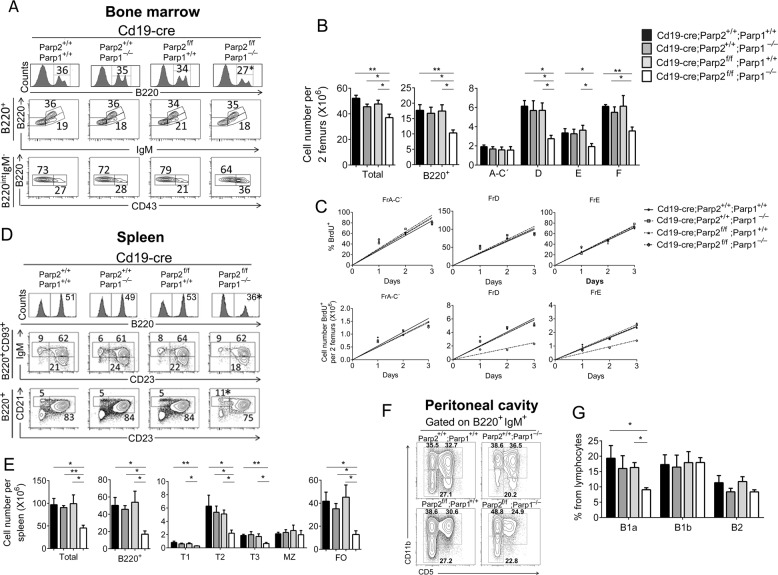

To determine the effects of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in B-cell development, we compared bone-marrow B-cells from single or dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice as well as control mice. Bone-marrow B220+ B-cells were decreased in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice compared with single PARP-1-deficient, single PARP-2-deficient or control mice (Fig. 2a, b). Further analysis of bone-marrow B-cell progenitors revealed that whilst fraction A-C′ was similar in all groups, the number of B-cell progenitors from later development stages (fractions D, E, and F) was significantly decreased in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice compared to single PARP-1-deficient, single PARP-2-deficient or control mice (Fig. 2a, b). To evaluate how dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency affects bone-marrow cell kinetics, we analyzed BrdU-labeling rates. All bone-marrow cell subsets displayed comparable proportional BrdU-labeling in dual or single PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice or controls (Fig. 2c and Table S1). However, dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice elicited a decrease in fractions D and E production compared to single PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice or controls (Fig. 2c and Table S1).

Fig. 2.

B-cell-specific deletion of PARP-2 in a PARP-1-deficient background results in defective B-cell development. Flow cytometry analysis of bone-marrow, spleen and peritoneal cavity cells from 8 to 10-weeks old Cd19-creParp-2+/+Parp-1+/+, Cd19-creParp-2+/+Parp-1−/−, Cd19-creParp-2f/fParp-1+/+, and CD19-creParp-2f/fParp-1−/− mice. a Representative histograms and dot-plots showing bone-marrow cells analyzed for the expression of the indicated markers. Percentage of cells in the individual subpopulations with regard to each gate is indicated in each quadrant. Values represent the mean of at least 8 mice of each genotype. b Graph showing total number of bone-marrow cells (two femours), and absolute number of B220+, CD43+B220intIgM− (Fr A-C′), CD43-B220intIgM−(Fr D), CD43-B220intIgM+ (Fr E), and CD43-B220highIgM+ (Fr F) in bone-marrow. The number of cells in each population was calculated by multiplying the percentage of each population by the total number of bone-marrow cells (two femurs). c Renewal and production rates of bone-marrow cell subsets from the indicated genotypes. Mice were injected with 1 mg BrdU at 12 h intervals and bone-marrow were harvested at the indicated times after the onset of the injections, stained for surface markers and BrdU incorporation and analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of BrdU-labeled cells was calculated by multiplying the percentage BrdU+-cells of each population by the total number of cells in that population. Each point represents an individual mouse. Lines are those determined by linear regression. d Representative dot-plots showing splenocytes stained for expression of the indicated markers. Percentage of cells in the individual subpopulations with regard to each gate is indicated in each quadrant. Values represent the mean of at least 8 mice of each genotype. e Graph showing total number of spleen cells, and the absolute number of B220+, transitional B-cells (B220+CD93+ gated lymphocytes. T1: IgMhighCD23low; T2: IgMhighCD23high; T3: IgMlowCD23high), Marginal Zone (MZ) B-cells (CD21highCD23low), and Follicular (FO) B-cells (CD21lowCD23high). The number of cells in each population was calculated by multiplying the percentage of each population by the total number of splenocytes. Values represent the mean ± SEM of at least 8 mice of each genotype. f Representative dot-plots showing peritoneal cavity cells stained for expression of the indicated markers. Percentage of cells in the individual subpopulations with regard to each gate is indicated in each quadrant. g Graph showing the percentage of B1a (B220+IgM+CD5+CD11b+), B1b (B220+IgM+CD5-CD11b+) and B2 (B220+IgM+CD5−CD11b−) cells among peritoneal lymphocytes. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 5 mice of each genotype. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency also led to a significant decrease in lymph nodes (Fig. S1) and splenic B-cells compared to single PARP-1-deficient, single PARP-2-deficient or control mice (Fig. 2d, e). This reduction was due to depletion of transitional and FO B-cells, whereas MZ B-cells were numerically conserved (Fig. 2d, e) despite loss of the floxed allele (Fig. S2). Dual PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice also display a decrease in peritoneal cavity B1a-cells (Fig. 2f, g). Thus, combined but no single PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency impairs the central development of B-cells as well as peripheral B-cell homeostasis.

PARP-1 and PARP-2 are dispensable for Ig V(D)J gene recombination

Given that PARP-1 and PARP-2 are involved in DDR, we hypothesized that impaired B-lymphoid development stemmed from defective Ig V(D)J recombination in dual PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice. Accordingly, we generated v-abl transformed pro-B-cell lines from wild type (WT), Parp1−/−, Parp2f/f, and Parp1−/−Parp2f/f mice (Table S2). Of note, treatment of v-abl pro-B-cells with the v-abl kinase inhibitor STI571 (ABLki) leads to G1 cell-cycle arrest, rapid induction of RAG1 and RAG2 gene expression and rearrangement of the Igk locus or any recombination substrate, thereby providing a pseudo-physiological model to study Ig V(D)J recombination [24–26].

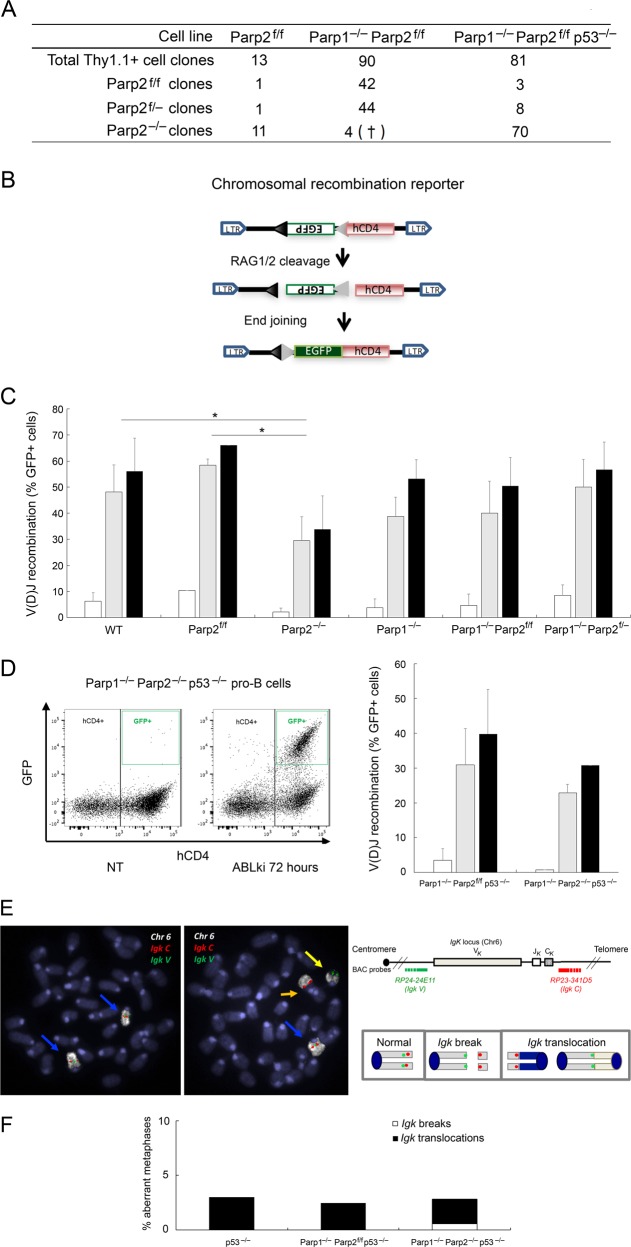

To delete Parp2 in Parp2f/f pro-B-cell lines, we infected Parp2f/f and Parp1−/−Parp2f/f pro-B-cells with an MSCV-CreE-IRES-Thy1.1 retroviral vector [27], which allows simultaneous expression of the Cre-recombinase and surface Thy1.1 expression. To ascertain the induction of complete Parp2 deletion, we PCR amplified Parp2 floxed alleles in single FACSorted Thy1.1+-pro-B-cells (Fig. 3a and Fig. S3). As expected, loss of Parp2 floxed alleles was observed in a majority of Thy1.1+-Parp2f/f pro-B-cell clones (11 out of 13 clones; 84.6%). In sharp contrast, 42 of 90 Thy1.1+-Parp1−/−Parp2f/f pro-B-cell clones analyzed (46.7%) were Parp2f/f, whereas 44 (48.9%) had lost one Parp2 floxed allele, and only 4 (4.4%) had lost both Parp2 floxed alleles (Fig. 3a). These clones died during the course of the analysis (data not shown). Thus, loss of both PARP-1 and PARP-2 appears to be synthetically lethal in v-abl pro-B-cells.

Fig. 3.

PARP1 and PARP2 are dispensable for V(D)J recombination. a Parp2 genotyping of v-abl pro-B-cell clones after pMSCV-CRE-IRES-Thy1.1 infection and single cell sorting. Number of cell clones genotyped is indicated. See also Fig. S3. † indicates that the clone died during cell expansion. b Schematic of pMX-INV recombination substrate. The 12-recombination signal sequence (RSS-12; black triangle), GFP cDNA, 23-recombination signal sequence (RSS-23; gray triangle), IRES - human CD4 cDNA (hCD4) and LTRs are indicated. c, d pMX-INV v-abl pro-B-cell lines untreated (white bars) or treated for 72 h (gray bars) and 96 h (black bars) with ABLki were assayed for pMX-INV rearrangement by flow cytometry, with the percentage of GFP expressing cells among total hCD4 positive cells indicated. Data represent the means ± SEMs of at least two independent experiments using wild type (WT), Parp2f/f, Parp2−/−, Parp1−/−, Parp1−/− Parp2f/f, Parp1−/− Parp2f/−, Parp1−/− Parp2f/f p53−/− and Parp1−/− Parp2−/− p53−/− cell lines described in Table S2. *P < 0.05. d, left panel Representative FACS plots of pMX-INV rearrangement before treatment (not treated, NT) and after 72 h of ABLki treatment (ABLki). e, f Genomic instability at the Igk locus in v-abl pro-B-cell lines. e Schematics of the Igk locus and chromosome 6, with positions of the BACs used for generation of DNA-FISH probes indicated. Representative metaphases from Parp1−/− Parp2−/− p53−/− v-abl pro-B-cells using the Igk C BAC probe (red) combined with Igk V BAC probe (green) and chromosome 6 paint (white). Blue arrowheads point to normal chromosome 6, yellow arrowhead point to broken and orange arrowhead to translocated chromosome 6. f Percentage of aberrant metaphases from v-abl pro-B-cell lines of the indicated genotype harboring chromosomes breaks (white) or translocations (black) involving the Igk locus. (See also Table S4)

To determine whether removal of the pro-apoptotic p53 gene enables survival of dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient v-abl pro-B-cell clones, we generated v-abl pro-B-cell lines from Parp1−/−Parp2f/fp53−/− mice and infected these cells with MSCV-CRE-IRES-Thy1.1. Unlike p53-sufficient Thy1.1+-Parp1−/−Parp2f/f pro-B-cell clones, p53-deficient Thy1.1+-Parp1−/−Parp2f/fp53−/− pro-B-cell clones showed homozygous deletion of Parp2 floxed alleles (70 out of 81 clones; 86.4%) (Fig. 3a and Fig. S3). Thus, loss of p53 rescues viability in v-abl-transformed pro-B-cells lacking both PARP-1 and PARP-2.

To measure Ig V(D)J recombination defects, we transduced pro-B-cell lines from each genotype with the pMX-RSS-GFP/IRES-hCD4 retroviral recombination substrate (pMX-INV), which allows GFP expression upon RAG-mediated recombination [24–26] (Fig. 3b). Flow cytometry showed robust pMX-INV rearrangement in ABLki-treated WT and Parp2f/f pro-B-cells (Fig. 3c). In agreement with in vivo data, PARP-1 deficiency did not significantly alter Ig V(D)J recombination in Parp1−/− or Parp1−/− Parp2f/f pro-B-cells as compared to WT cells (Fig. 3c). Similarly, pMX-INV rearrangement was not markedly affected in Parp2−/− pro-B-cells, although it was significantly diminished as compared to WT or Parp2f/f controls (Fig. 3c).

We also detected robust pMX-INV rearrangement in Parp1−/−Parp2f/− pro-B-cells (Fig. 3c), which indicates that Parp2 is haplosufficient in the context of PARP-1 deficiency with respect to Ig V(D)J recombination (Fig. 3c). Remarkably, flow cytometry also revealed robust inversional rearrangement in both ABLki-treated Parp1−/−Parp2f/fp53−/− and Parp1−/−Parp2−/−p53−/− pro-B-cells (Fig. 3d), which indicates that PARP-1 and PARP-2 are dispensable for RAG-mediated Ig V(D)J rearrangement in pro-B-cells. Consistent with this, analysis of endogenous Igk recombination products revealed robust RAG-induced recombination at these loci in the absence of PARP-1 and PARP-2 (Fig. S4).

We next quantified the presence of DNA damage-associated 53BP1 foci in G1-arrested pro-B-cells [28, 29] (Fig. S5). Pro-B-cells lacking double-strand break (DSB) repair capacity harbor 53BP1 foci in the vast majority of ABLki-treated pro-B-cells due to accumulation of unrepaired RAG-induced DSBs [28, 29]. As shown previously in DNA repair proficient pro-B cells [28], we found that only 15.9% of p53−/− pro-B-cells showed intense 53BP1 foci, the majority of which contained a single distinct spot, although cells were occasionally found to contain two foci (Fig. S5 and Table S3). Similarly, we found that an average of 17.1% Parp1−/−Parp2f/fp53−/− and 25.1% of Parp1−/−Parp2−/−p53−/− ABLki-treated pro-B-cells harbored 53BP1 foci, the majority consisted of a single focus (Fig. S5 and Table S3), which indicates that RAG-induced DSB response and repair is not severely impaired in the absence of both PARP-1 and PARP-2.

Although Ig V(D)J recombination and RAG-induced DDR seemed relatively normal in dual PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient pro-B-cells, we tested whether low levels of unrepaired RAG-induced DNA breaks persisted in these cells. Such breaks would lead to chromosomal instability upon re-entry into the cell cycle, as previously reported in the context of end-joining deficiency [28]. To address this possibility, we performed DNA-FISH analysis on chromosome spreads prepared from untreated cycling cells and G1-arrested cells that were released back into cell-cycle upon removal of ABLki (Fig. 3e, f and Table S4). Using probes centromeric (Igk V) and telomeric (Igk C) to the Igk locus together with paint specific for chromosome 6 (Fig. 3e), we quantified the frequency of Igk chromosome breaks and translocations (Fig. 3f and Table S4). Since DNA breaks induce strong p53-dependent G1/S checkpoint in these cells [28], we used Parp1−/−Parp2f/fp53−/− and Parp1−/−Parp2−/−p53−/− pro-B-cells to perform these experiments (Fig. 3f and Table S4). As a control, we used a previously published p53-deficient pro-B-cell line that harbors low levels of Igk-associated chromosomal instability upon RAG-mediated VJ gene recombination [28].

In agreement with results from experiments measuring pMX-INV rearrangement, Igk rearrangement and 53BP1 foci formation, metaphases prepared from ABLki-released Parp1−/−Parp2f/fp53−/− and Parp1−/−Parp2−/−p53−/− pro-B-cells showed low levels of genomic instability, most notably translocations (2.4% and 3%, respectively; n = 205 or 499) similar to p53−/− pro-B-cells (3%; n = 101) (Fig. 3f and Table S4). Altogether, these results indicate that PARP-1 and PARP-2 are dispensable for RAG-induced Ig V(D)J recombination in G1-arrested pro-B-cells.

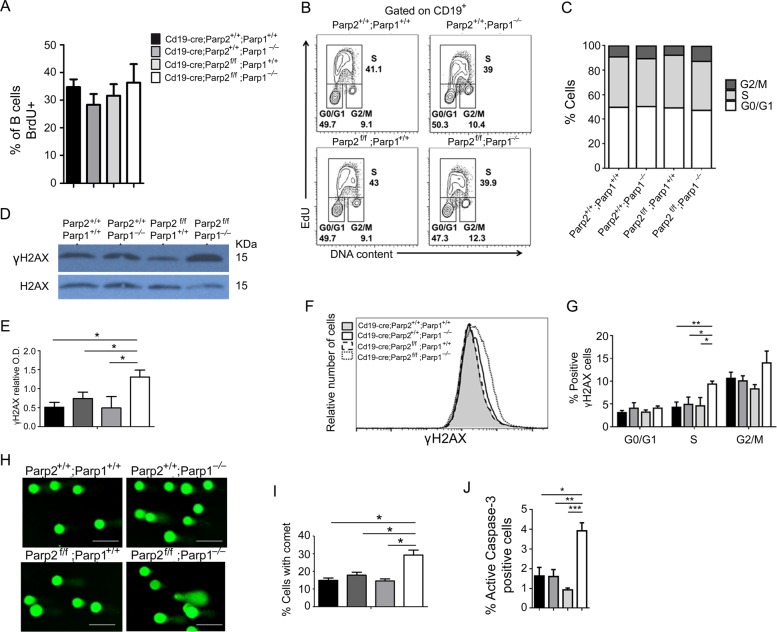

PARP-1 and PARP-2 attenuate B-cell death

B-cell depletion in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice could stem from an impairment of B-cell proliferation, B-cell survival or both. Proliferating BrdU+ B-cells from the bone-marrow of dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice were comparable to the other three genotypes (Figs. 2c and 4a). These data indicate that bone-marrow B-cells with dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 insufficiency can normally initiate DNA synthesis. Accordingly, splenic B-cells from dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice showed no alteration of the cell-cycle profiles upon exposure to LPS compared to control as well as single PARP-1 or PARP-2-deficient B-cells (Fig. 4b, c).

Fig. 4.

Cell-cycle profiles, DNA damage and apoptosis in PARP-1/PARP-2-doubly deficient splenic B-cells. a In vivo proliferation of bone-marrow B-cells was determined by intraperitoneal injection of 6–8-weeks-old mice of the indicated genotypes with BrdU (1 mg) at 12 h intervals. Bone-marrow was harvested at 24 h after the onset of injection and BrdU incorporation on B cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Bars represent the mean ± SEM values of the percentage of BrdU+ B-cells obtained from 6 mice per genotype. b, c B-cells from spleen of mice of the indicated genotype were culture in the presence of LPS (10 µg/ml). After 36 h in cultured, cells were pulsed with EdU for 60 min. Click-iT EdU kit from ThermoFisher was used to detect replicating cells and DAPI was used to determine DNA content. b Representative cell-cycle profiles from three independent experiments. c Percentage of cells that are in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases of cell-cycle. Bars represent the mean ± SEM obtained from 6 mice per genotype. d B-cells from spleen of mice of the indicated genotype were culture in the presence of LPS (10 µg/ml). After 36 h in cultured, cells were collected and protein extracts were prepared. A representative western-blot of γ-H2AX and H2AX protein expression. e Densitometry analysis (optical density) of γ-H2AX bands from western blotting. f Representative flow cytometry histograms showing γ-H2AX protein levels (on the basis of mean fluorescence intensity) in B-cells from spleen of mice of the indicated genotype after culture for 36 h in the presence of LPS (10 µg/ml). g Graph showing the percentage of γ-H2AX-positive cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases of cell-cycle in B-cells from spleen of mice of the indicated genotype after culture for 36 h in the presence of LPS (10 µg/ml). h Representative images showing DNA damage in B-cells after stimulation for 36 h with LPS, visualized by alkaline-comet assay. i Graph showing the percentage of cells with comet. An average of 100 cells was scored from each mouse. j Bars represent the percentage of B-cells positive for active caspase-3 after 36 h of culture in the presence of LPS. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

LPS-activated splenic B-cells from dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice exhibited increased phosphorylation of histone H2AX (Fig. 4d–f), a hallmark of DNA damage. This increase on γH2AX was limited to S/G2 cells (Fig. 4g), which indicates replicative-stress [30, 31]. We next subjected LPS-activated B-cells to an alkaline-comet assay. We observed a significant increase of dual PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient B-cells exhibiting comet shape compared to control and single PARP-1 or PARP-2-deficient B-cells (Fig. 4h, i). In agreement with these results, a significant increase in apoptotic cells was observed in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient B-cells compared to control and single PARP-1 or PARP-2-deficient B-cells (Fig. 4j). Thus, B-cells with combined PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficiency proliferated in response to the lymphopenic environment, but accumulated DNA damage that caused cell death at a faster rate.

PARP-1 and PARP-2 are required for antibody responses to TI but not TD antigens

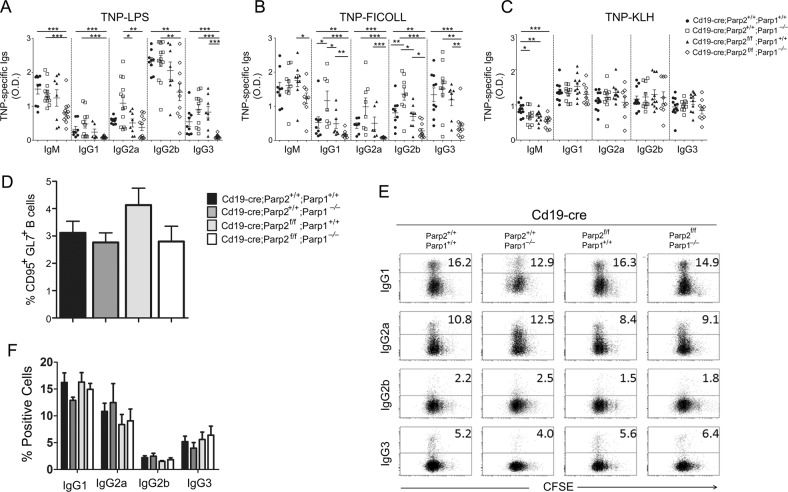

To determine the role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in B-cell antibody production under steady-state conditions, we measured the serum concentration of immunoglobulins in non-immunized control, single PARP-1-deficient, single PARP-2-deficient and dual PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice. We found that serum IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 were comparable in mice from the four groups (Fig. S6). Next, we determined whether B-cell-specific deletion of PARP-2 in PARP-1-sufficient or PARP-1-deficient mice altered antibody responses to TI or TD antigens. Compared to single PARP-1-deficient or single PARP-2-deficient mice and control mice, dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice showed decreased TNP-specific IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 responses upon immunization with TNP-LPS (Fig. 5a), which is a type-I TI antigen. Similarly, dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice showed reduced TNP-specific responses upon immunization with TNP-Ficoll (Fig. 5b), which is a type-II TI antigen. Conversely, single PARP-1-deficient mice showed increased TNP-specific IgG1, and IgG2b responses to TNP-Ficoll (Fig. 5b). Unlike TI antigens, the TD-antigen TNP-KLH elicited comparable TNP-specific antibody responses and similar percentage of germinal centers B-cells in dual or single PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice or controls (Fig. 5c, d). Of note, similar percentage of germinal centers B-cells was also observed in Peyer’s patches from all genotypes (Fig. S7).

Fig. 5.

PARP-1/PARP-2 doubly deficiency in B-cells causes faulty T-independent but not T-dependent immune responses. 8–10-weeks-old mice of the indicated genotypes were immunized i.p. with a type-I T cell-independent (TNP-LPS), b type-II T cell independent (TNP-Ficoll), or c T cell-dependent (TNP-KLH) antigens. Fourteen days after immunization, TNP-specific IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 were evaluated in the sera by ELISA. Dots represent individual mice from two independent immunization experiments and horizontal lines represent median values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. d Fourteen days after TNP-KLH immunization, spleen was analyzed for the presence of germinal center (CD95+GL7+) B cells. Bars represent the percentage of germinal center B lymphocytes for the indicated genotype. Values represent the mean ± SEM of at least 4 mice of each genotype. e Representative dot-blot showing the surface expression of IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and CFSE dilution analyzed by flow cytometry in B-cells from the indicated genotypes, stimulated for 72 h with either LPS + IL-4 (CSR to IgG1) or LPS (CSR to IgG2b and IgG3) or LPS + IFN-γ (CSR to IgG2a). The percentage of switched cells is indicated. f Bars represent the percentage of B lymphocytes positive for the indicated Ig isotype. Data are representative of four independent experiments

To assess the role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in B-cell class switching, we stimulated purified splenic resting B-cells with LPS with or without IL-4 or INF-γ during 3 days. We found that B-cells with dual PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficiency underwent class switching at a frequency comparable to that of B-cells with single PARP-1 or PARP-2 deficiency (Fig. 5e, f). Thus, PARP-1 and PARP-2 are required for class-switched IgG responses to some but not all antigens as a result of their essential role in B-cell development and homeostasis but not as a result of their B-cell-intrinsic CSR-inducing activity.

Discussion

Here, we have found that combined expression of the DNA repair enzymes PARP-1 and PARP-2 promotes central B-cell development and sustains peripheral B-cell homeostasis, including antibody responses to TI antigens but not TD antigens. Despite the crucial role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in DDR, these enzymes were dispensable for both Ig V(D)J gene recombination and CSR. Indeed, PARP inhibitors are a rapidly evolving class of drugs that prevent cancer cells from repairing damaged DNA thereby causing them to die [32]. Hence, a better understanding of the function of PARP1 and PARP2 in proliferating immune cells such as B-lymphocytes is becoming a pressing need to design better PARP-targeting agents devoid of harmful off-target effects on the humoral arm of the immune system.

A key finding of our study is that mice with dual but not individual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency showed loss of B-cells in the bone-marrow, which started at pre-B cell stage. Considering that PARP deficiency could cause central B-cell death by preventing the repair of double-strand DNA lesions brought about by RAG-mediated Ig gene V(D)J recombination, one possible explanation of our finding is that PARP-1 and PARP-2 can compensate for the lack of one or the other during Ig V(D)J recombination. Our data rule out any major role of either PARP-1 or PARP-2 in Ig V(D)J recombination. Moreover, our findings show that B-cells with combined PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency remain proficient in the execution of Ig V(D)J recombination. Considering that RAG-mediated repair of DSBs is restricted to the G1 phase of the cell-cycle, we propose that the DNA repair activity of PARP-1 and PARP-2 is very limited in non-cycling B-cells.

An alternative explanation for the B-cell lymphopenia in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice could relate to a shift in the balance between proliferation and survival during B-cell development, with homeostatic expansion aimed at replenishing the B-cell niche [33, 34]. Indeed, our data show that peripheral B-cells from mice with dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency normally enter the S phase of the cell-cycle upon receiving a polyclonal proliferation-inducing stimulus. However, these activated B-cells show increased death.

Consistent with the important role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in maintaining genomic stability [7], we found that these DNA repair enzymes function in a redundant manner in actively proliferating B-cells and may do so to prevent the accumulation of toxic levels of unrepaired DNA damage. Indeed, this damage could cause death during homeostatic or antigen-induced B-cell proliferation. This interpretation is consistent with recent results showing that dual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency causes accumulation of replication-derived DNA damage owing to the cell’s inability to stabilize Rad51 at damaged DNA-replication forks and thereafter prevent uncontrolled DNA resection [35].

According to the principle of synthetic lethality, which posits that combined but not isolated lesions of two distinct genes result in cell death [36], PARP-1 and PARP-2 may regulate two independent but functionally linked processes. In particular, they may promote base excision repair directly while stabilizing replication forks that encounter base excision repair intermediates [35]. Such mechanism could explain the PARP-1 and PARP-2 synthetic lethality that we observed in the context of v-abl transformed pro-B-cells. As previously demonstrated by our group [18], PARP-1 and PARP-2 would exerts a similar function in T cells, raising the possibility that there is a master mechanism that allows the PARP system to maintain genomic stability during the proliferation of the lymphoid compartment.

Remarkably, the impaired central B-cell development detected in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice did not yield comparable consequences in FO and MZ B-cells, as combined PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency dampened the size of FO but not MZ B-cell pools. This finding raises the possibility that PARP-1 and PARP-2 deploy important but somewhat redundant functions in the development and/or homeostatic maintenance of the FO but not MZ B-cell compartments. Accordingly, several genes are essential for maintaining FO but not MZ B-cells, including c-myb [37], Akirin2 [38], Flt3-ligand [39], and DKK3 [40]. An explanation for the observed dichotomy of FO and MZ B-cell fate in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient could relate to the longer lifespan and self-renewal capability of MZ compared to FO B-cells [2].

The peripheral B-cell lymphopenia detected in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice was associated with an impairment of antibody responses to TI but not TD antigens. This finding was somewhat unexpected, as TI and TD antigens mainly induce antibody production by stimulating MZ and FO B-cells [3], which are conserved and depleted in dually PARP-deficient mice, respectively. However, a normal MZ B-cell number does not necessarily correlate with a conserved functionality. For instance, Sh3bp2−/− and Hipk1−/− [41, 42] mice show an increased MZ B-cell compartment but poor antibody responses to TI antigens. Conversely, these responses can be normal in mice with a depleted MZ B-cell compartment [43].

Clearly, further studies are needed to determine how PARP-1 and PARP-2 preserve the functionality of MZ B-cells as they respond to a TI antigen. This response has innate-like properties that ultimately lead to an explosive extrafollicular differentiation and expansion of antibody-secreting plasmablasts [3]. One possibility is that PARP-1 and PARP-2 deploy coordinated signals to specifically control the proliferation of these plasmablasts instead of their MZ B-cell precursors. Remarkably, MZ B-cells can be also recruited into antibody responses to TD antigens [3], which could explain why these responses were normal in dually PARP-1 and PARP-2-deficient mice, despite their overt depletion of FO B-cells. Alternatively, the surviving FO B-cells from these mice may have a compensatory increase of their proliferation, survival, and/or differentiation properties, including plasmablast-associated antibody secretion, which could make up for their depletion.

In summary, we found that central B-cell development and peripheral B-cell homeostasis are impaired in mice with combined but not individual PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency. In the periphery, this impairment mainly features depletion of FO but not MZ B-cells as well as impaired antibody responses to TI but not to TD antigens. Notwithstanding the pivotal role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 in DNA repair, combined PARP-1 and PARP-2 deficiency did not perturb Ig V(D)J recombination and IgM-to-IgG CSR. These findings may facilitate the development of safer PARP-targeting regimens against cancer with reduced off-target effects on the immune system.

Materials and methods

Mice

Parp-2flox/flox (Parp-2f/f), Parp-1−/− and transgenic mice for Cre-recombinase driven by the Cd19 promoter (Cd19-cre) have been described [18, 23, 44]. p53−/− mice were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis using tail DNA. Parp-2flox, Parp-1, and p53 genotyping has been described [16, 18, 45]. Cd19-cre was genotyped using the following primers: CD19f_22B5 AGGGAGGCAATGTTGTGCT; CD19r_22B6 TGCCAGACCAAAGAACTTCCTC; CreR_6B3 GTTCGAACGCTAGAGCCTGTTT. All mice had C57BL/6J background and were reared under pathogen-free conditions. The PRBB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the studies and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Parp-2 deletion on genomic DNA was confirmed by PCR analysis on FACSorted bone-marrow and spleen populations.

PARP activity

Protein extracts were prepared from purified B-cells upon LPS stimulation (10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2.5 days as previously described [46]. PARP activity was determined by using 10 μg of total protein and the HT Universal Colorimetric PARP Assay Kit with Histone-Coated Strip Wells (Trevigen) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Western-blot

Cell lysates were prepared homogenizing PBS-washed cells in SDS-sample buffer (67 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 0.01% (w/v) Bromophenol blue, 10% (v/v) glycerol). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by standard western blotting techniques, using the following antibodies: PARP-1 (clone A6.4.12), in-house generated affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against PARP-2 residues 1–69 fused to GST, and β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, clone AC-15). Primary antibody binding was detected using peroxidase-coupled rabbit anti-mouse (GE Healthcare) or goat-anti-rabbit Ig antibodies (Dako) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cell suspensions were recovered from bone-marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches and peritoneal cavity of mice, washed in PBS, resuspended in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and incubated with antibodies on ice for 30 min. Incubation with biotin-labeled antibodies was followed by incubation with streptavidin conjugates. For intracellular staining, cells were stained for cell-surface markers, fixed and made permeable by using an intracellular staining buffer set (BD Biosciences), and then stained with specific antibody or isotype control. Red Blood Cells (RBC) were lysed using ACK lysis buffer (BioWhitaker). The following antibodies were used: APC-Cy7-conjugated CD3 (17A2; BD Biosciences), PerCP- and APC-conjugated CD45R (B220) (RA3-6B2; BD Biosciences), PE-, FITC, and APC-Cy7-conjugated IgM (R6-60.2; BD Biosciences), APC-Cy7-conjugated CD43 (S7; BD Biosciences), APC and FITC-conjugated CD21 (7G6; BD Biosciences), FITC and PE-conjugated CD23 (B3B4; BD Biosciences), PerCP/Cy5.5-conjugated CD93 (AA4.1; BioLegend), PE-conjugated CD25 (3C7; BioLegend), APC-Cy7-conjugated CD117 (2B8; BioLegend), PE-Cy5-conjugated CD5 (53–7.3; BioLegend), FITC-conjugated GL-7 (GL7; BioLegend), PE-conjugated CD95 (Jo2; BD Biosciences), FITC-conjugated CD11b (M1/70; BioLegend), Alexa Fluor-555-conjugated phospho-H2AX (S139) (JPW301; Millipore), FITC-conjugated active caspase-3 (rabbit polyclonal antibody; BD Biosciences), biotin-conjugated IgM (R60.2; BD Biosciences), biotin-conjugated IgG1 (A85-1; BD Biosciences), biotin-conjugated IgG2a (R19-15; BD Biosciences), biotin-conjugated IgG2b (R12-3; BD Biosciences), biotin-conjugated IgG3 (R40-82; BD Biosciences), APC-conjugated streptavidin (BD Biosciences). Cell doublets were excluded from all analyses and dead cells were excluded by the use of DAPI. Samples were acquired with a Fortessa cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the data analyzed with the DIVA (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo (TreeStar) softwares. Cell sorting was performed in a FACS AriaIISORP (BD Biosciences).

BrdU incorporation

Mice received intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (BD Biosciences; 1 mg per mouse) every 12 h and were sacrificed at 24, 48, and 72 h. Bone-marrow cells were surface-stained, fixed, permeabilized, and intracellularly stained using a BrdU Flow kit (BD Biosciences).

Cell-cycle, DNA damage, and apoptosis

Untouched purified B-cells from spleen were cultured for 36 h in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS in the presence of LPS (10 μg/ml). Cells were then pulsed with 10 µM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 60 min at 37 °C, and then processed with the Click-iT flow cytometry kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and analyzed by flow cytometry. For detection of active caspase-3 and γ-H2AX, cells were harvested at 36 h after stimulation with LPS (10 μg/ml), stained for cell-surface markers, fixed, and made permeable by using an intracellular staining buffer set (BD Biosciences), and then stained with specific antibody or isotype control, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Alkaline-comet assay on LPS-activated B-cells was performed with CometAssay kit (Trevigen) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Class-switching assays

Untouched B-cells were isolated from spleens of 8–12-weeks-old mice by magnetic depletion of non-B-cells using a MACS Pan-B-cell isolation kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity was assessed by flow cytometry analysis using antibodies against B220 and all preparations were more than 98% pure B-cells. Cells were resuspended in RPMI media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), seeded in 96-well plates (2 × 105 cells per well). For in vitro class-switching analysis, B-cells were harvested at day 3 after stimulation with LPS (10 µg/ml), LPS + IL-4 (50 ng/ml; Peprotech), or LPS + IFN-γ (10 ng/ml; Peprotech), stained for surface expression of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG3, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunizations

To test T cell-dependent responses, 8–12-weeks-old animals were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg/mouse of trinitro-phenyl-conjugated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (TNP-KLH) (Biosearch Technologies) in Sigma Adjuvant System (Sigma-Aldrich). For T cell-independent responses, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with either 20 μg/mouse of TNP-LPS (Type I; Sigma-Aldrich) or 40 μg/mouse of TNP-Ficoll (Type II; Biosearch Technologies). Serum was collected from tail vein before injection and 14 days after immunization.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

To determine the concentration of basal serum immunoglobulins, 96-well plates (BD Biosciences) were coated with antibody (IgM (II/41), IgG1 (A85-3), IgG2a (R11-89, IgG2b (R9-91), and IgG3 (R2-38), (all from BD Biosciences) in PBS/Tris-HCl 0.1 M at 5 μg/ml overnight at 4 °C. Isotype standards Abs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. TNP-BSA (Biosearch Technologies) was used to coat plates for detecting TNP-specific Ig in the sera of immunized mice. After blocking with PBS and 1% BSA, dilutions of mouse serum were added, and again plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, biotinylated anti-mouse IgM (R60.2), IgG1 (A85.1), IgG2a (R19-15), IgG2b (R12-3), and IgG3 (R40-82) secondary antibodies (BD Biosciences) were added and plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the plates were incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Dako) for 1 h at room temperature. Following washing, 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and the plates were read at 655 nm.

Generation of v-abl transformed pro-B-cell lines

Total bone-marrow from 4–8-weeks old mice of each genotype (i.e., wild type; Parp1−/−; Parp2flox/flox; Parp1−/− Parp2flox/flox; Parp1−/− Parp2flox/flox p53−/−) were used to generate viral-Abelson kinase (v-abl) immortalized pro-B-cell lines [24, 47]. v-abl transformed pro-B-cell lines were transduced with pMSCV-Bcl2-puro retrovirus to protect them from ABL kinase inhibitor-induced cell death [24, 28]. v-abl Parp2 floxed pro-B-cell lines were subsequently transduced with pMSCV-CRE-IRES-Thy1.1 retrovirus [27]. The next day, single cells expressing Thy1.1 were sorted using a BD FACSAriaTM cell sorter into 96-well plates and, after ~2 weeks of culture, cell clones were genotyped using the following primers: Parp2 floxed allele forward: CTCGAGTGTTTCACTGTGAGGGAG; Parp2 floxed allele reverse: CCCCAAACCAGAGTCCCATCC, Parp1 wild-type allele: GGCCAGATGCGCCTGTCCAAGAAG, Parp1 wild type and null alleles: CTTGATGGCCGGGAGCTGCTTCTTC, Parp1 null allele: GGCGAGGATCTCGTCGTGACCCATG.

Ig V(D)J gene recombination assay

The pMX-INV substrate was introduced in pro-B-cell lines or clones through retroviral infection and cells that had integrated the recombination substrate were enriched based on hCD4 expression [24]. For V(D)J recombination assay, v-abl transformed pMX-INV infected pro-B-cells (106/ml) were treated with 3 μM of the ABL kinase inhibitor (ABLki) STI571 (Novartis) and assayed for rearrangement by FACS analysis of GFP expression at 0, 72, or 96 h. V(D)J recombination efficiency was scored as the percentage of GFP positive cells among hCD4 positive cells. For ABLki release experiments (i.e., analysis of RAG-induced genetic instability in pro-B-cells), cells were collected, washed, and cultured without ABLki for 3–4 days before metaphases preparation.

Metaphase preparation

Metaphases were prepared using standard procedures [24]. Briefly, cells were incubated with colcemid (0.03 μg/ml, Life technologies, KaryoMAX Colcemid Solution) for 3–4 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were collected and incubated in 0.075 M KCl for 10 min at 37 °C, fixed in fixative solution (75% methanol/25% acetic acid) and washed three times in the fixative. Cell suspension was dropped onto humid slides and air-dried for further analysis.

DNA-FISH probes

BAC probes RP24-243E11 (5′ Igk V) and RP23-341D5 (3′ Igk C) were directly labeled by nick translation with ChromaTide Alexa Fluor 488- and 594-5-dUTP (Life technologies), as previously described [48]. Nick translation reaction was optimized to get a DNA smear between 100 bp and 600 bp. Labeled BAC probes were purified using Illustra MicroSpin G-50 Columns (GE Healthcare). 600 ng of each locus specific BAC probes were pooled and precipitated with mouse Cot1 DNA and Salmon Sperm DNA (Life Technologies). Probes were then resuspended in hybridization buffer (10% dextran sulfate, 5X Denharts solution, 50% formamide), denatured for 5 min at 95 °C and pre-annealed for 30–45 min at 37 °C. XCyting Mouse Chromosome 6 (Orange) paint from MetaSystems were denatured for 5 min at 95 °C and mixed with BAC probes just before hybridization.

DNA-FISH on metaphase spreads

Slides were treated with RNase A for 40 min, dehydrated in 70%, 90 and 100% ethanol for 3 min each, denatured in 70% formamide/2× SSC for 3 min at 77 °C, dehydrated again in cold ethanol series, and hybridized with probes o/n at 37 °C in a humid chamber. The next day, slides were washed three times in 50% formamide/0.5× SSC for 5 min each at 37 °C and twice in 0.5× SSC for 10 min each at 37 °C. Finally, slides were mounted in ProLong Gold (Life Technologies) containing 49,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to counterstain total DNA. Metaphases were imaged using a ZEISS AxioImager.Z2 microscope and the Metafer automated capture system (MetaSystems), and counted manually.

53BP1 immunofluorescence on interphase nuclei

After 65 h treatment with ABLki, pro-B-cell lines were adhered to poly-l lysine-coated coverslips and stained as previously described [29, 48]. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and permeabilized for 5 min with 0.4% Triton/PBS on ice. Immunofluorescence was performed after 30 min blocking in 2.5% BSA/10% Goat Serum/0.1% Tween-20/PBS, with a primary antibody against 53BP1 (NB100-304SS, 1:1000 dilution, Novus Biologicals) and a secondary goat-anti-rabbit antibody (Alexa Fluor 594, 1:1000 dilution; Life Technologies) in blocking solution, for 1 h each at RT. Cells were washed three times with 0.5% BSA/0.1% Tween-20/PBS after both primary and secondary antibody incubations. Finally, slides were mounted in ProLong Gold (Life Technologies) containing DAPI to counterstain total DNA. Cells were imaged in 3D (9 Z stacks of 0.5 μm) using a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 microscope and the Metacyte automated capture system (Metasystems). 53BP1 foci were counted using a custom Metacyte classifier. >2500 nuclei were counted for each genotype (see Supplementary Table for details).

PCR analysis of V(D)J recombination products

Vk6-23/Jk1 coding joints were amplified as previously described [25, 28]. 500 ng of genomic DNA was amplified using pkJa2 (GCCACAGACATAGACAACGGAA) and pκ6d (GAAATACATCAGACCAGCATGG) primers. 2 μl of this reaction was amplified using pkJa2 and pk6c (GTTGCTGTGGTTGTCTGGTG) primers. Vk10-95/Jk4 coding joints were amplified using JK4-pa (CGCTCAGCTTTCACACTGACT) and V10-95-pa (TTCCTTGGTCTCCTGTTGCT) primers for the first PCR and using JK4-pb (CAGGTTGCCAGGAATGGCTC) and V10-95-pb (TCTTGTTGACTGGCGTTTTG) primers for the second PCR. Il-2 gene was amplified using IMR42 (CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT) and IMR43 (GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATGATGC) primers and was used as loading control.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean values ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were carried out by using a Mann–Whitney test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Moreno and M. Juan for assistance with mice. The Deriano lab members for help with pro-B-cell lines experiments. O. Fornes for cell sorting and flow cytometry assistance. The Yélamos’s lab is funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (grant SAF2017-83565-R) and The Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AECC). The Deriano’s lab is funded by the Institut Pasteur, the Institut National du Cancer (# PLBIO16-181) and the European Research Council under the ERC (starting grant agreement #310917). The Dantzer’s lab is supported by LABEX ANR-10-LABX-0034_Medalis, Strasbourg University, CNRS. The Cerutti’s lab is supported by the European Research Council (European Advanced Grant ERC-2011-ADG-20110310) and by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (grant SAF2014-52483-R). MAG-C is supported by CONACyT.

Author contributions

MAG-C contributed to the generation of the mouse models and the characterization of B-cells in those animal models. MBF generated v-abl pro-B-cell lines and carried out V(D)J recombination and genetic instability experiments. CL performed 53BP1 immunofluorescence experiments. FD engineered the Parp-2f/f mouse model. LM-L, JF, and CA contributed to mouse models generation and flow cytometry studies. JM-C and CM contributed to mice immunization. AC and PA contributed to planned and designed experiments. JY and LD planned and designed experiments and performed experiments. JY, AC, and LD wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by A. Villunger

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ludovic Deriano, José Yélamos

Contributor Information

Ludovic Deriano, Phone: +33 (0)1 44 38 93 55, Email: ludovic.deriano@pasteur.fr.

José Yélamos, Phone: +34-933160411, Email: jyelamos@imim.es.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-019-0326-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. B cell development pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:595–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillai S, Cariappa A. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:767–77. doi: 10.1038/nri2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:118–32. doi: 10.1038/nri3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia dV, O’Leary P, Sze DM, Toellner KM, MacLennan IC. T-independent type 2 antigens induce B cell proliferation in multiple splenic sites, but exponential growth is confined to extrafollicular foci. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1314–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199904)29:04<1314::AID-IMMU1314>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue T, Moran I, Shinnakasu R, Phan TG, Kurosaki T. Generation of memory B cells and their reactivation. Immunol Rev. 2018;283:138–49. doi: 10.1111/imr.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tas JM, Mesin L, Pasqual G, Targ S, Jacobsen JT, Mano YM, et al. Visualizing antibody affinity maturation in germinal centers. Science. 2016;351:1048–54. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yelamos J, Farres J, Llacuna L, Ampurdanes C, Martin-Caballero J. PARP-1 and PARP-2: new players in tumour development. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:328–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels CM, Ong SE, Leung AK. The promise of proteomics for the study of ADP-ribosylation. Mol Cell. 2015;58:911–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai P. Biology of poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerases: the factotums of cell maintenance. Mol Cell. 2015;58:947–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menissier de MJ, Ricoul M, Tartier L, Niedergang C, Huber A, Dantzer F, et al. Functional interaction between PARP-1 and PARP-2 in chromosome stability and embryonic development in mouse. EMBO J. 2003;22:2255–63. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson BA, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Hussey KM, Shrimp JH, Lin H, et al. Chemical genetic discovery of PARP targets reveals a role for PARP-1 in transcription elongation. Science. 2016;353:45–50. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali SO, Khan FA, Galindo-Campos MA, Yelamos J. Understanding specific functions of PARP-2: new lessons for cancer therapy. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:1842–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farres J, Martin-Caballero J, Martinez C, Lozano JJ, Llacuna L, Ampurdanes C, et al. Parp-2 is required to maintain hematopoiesis following sublethal gamma-irradiation in mice. Blood. 2013;122:44–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-472845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farres J, Llacuna L, Martin-Caballero J, Martinez C, Lozano JJ, Ampurdanes C, et al. PARP-2 sustains erythropoiesis in mice by limiting replicative stress in erythroid progenitors. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1144–57. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dantzer F, Mark M, Quenet D, Scherthan H, Huber A, Liebe B, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 contributes to the fidelity of male meiosis I and spermiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14854–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604252103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolas L, Martinez C, Baro C, Rodriguez M, Baroja-Mazo A, Sole F, et al. Loss of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 leads to rapid development of spontaneous T-cell lymphomas in p53-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2010;29:2877–83. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yelamos J, Monreal Y, Saenz L, Aguado E, Schreiber V, Mota R, et al. PARP-2 deficiency affects the survival of CD4 + CD8 + double-positive thymocytes. EMBO J. 2006;25:4350–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navarro J, Gozalbo-Lopez B, Mendez AC, Dantzer F, Schreiber V, Martinez C, et al. PARP-1/PARP-2 double deficiency in mouse T cells results in faulty immune responses and T lymphomas. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41962. doi: 10.1038/srep41962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZQ, Stingl L, Morrison C, Jantsch M, Los M, Schulze-Osthoff K, et al. PARP is important for genomic stability but dispensable in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2347–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison C, Smith GC, Stingl L, Jackson SP, Wagner EF, Wang ZQ. Genetic interaction between PARP and DNA-PK in V(D)J recombination and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 1997;17:479–82. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown ML, Franco D, Burkle A, Chang Y. Role of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in DNA-PKcs- independent V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4532–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072495299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robert I, Dantzer F, Reina-San-Martin B. Parp1 facilitates alternative NHEJ, whereas Parp2 suppresses IgH/c-myc translocations during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1047–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1317–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenden HH, Lescale C, Bianchi JJ, Yu W, Bedora-Faure M, Deriano L. Generation and CRISPR/Cas9 editing of transformed progenitor B cells as a pseudo-physiological system to study DNA repair gene function in V(D)J recombination. J Immunol Methods. 2017;451:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bredemeyer AL, Sharma GG, Huang CY, Helmink BA, Walker LM, Khor KC, et al. ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2006;442:466–70. doi: 10.1038/nature04866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muljo SA, Schlissel MS. A small molecule Abl kinase inhibitor induces differentiation of Abelson virus-transformed pre-B cell lines. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:31–37. doi: 10.1038/ni870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deriano L, Stracker TH, Baker A, Petrini JH, Roth DB. Roles for NBS1 in alternative nonhomologous end-joining of V(D)J recombination intermediates. Mol Cell. 2009;34:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lescale C, Abramowski V, Bedora-Faure M, Murigneux V, Vera G, Roth DB, et al. RAG2 and XLF/Cernunnos interplay reveals a novel role for the RAG complex in DNA repair. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10529. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lescale C, Lenden HH, Blackford AN, Balmus G, Bianchi JJ, Yu W, et al. Specific roles of XRCC4 paralogs PAXX and XLF during V(D)J recombination. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2967–79. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toledo LI, Murga M, Zur R, Soria R, Rodriguez A, Martinez S, et al. A cell-based screen identifies ATR inhibitors with synthetic lethal properties for cancer-associated mutations. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:721–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syljuasen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, Fugger K, Lundin C, Johansson F, et al. Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3553–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3553-3562.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashworth A, Lord CJ. Synthetic lethal therapies for cancer: what’s next after PARP inhibitors? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:564–76. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardy RR, Kincade PW, Dorshkind K. The protean nature of cells in the B lymphocyte lineage. Immunity. 2007;26:703–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allman D, Pillai S. Peripheral B cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronson GE, Piberger AL, Higgs MR, Olsen AL, Stewart GS, McHugh PJ, et al. PARP1 and PARP2 stabilise replication forks at base excision repair intermediates through Fbh1-dependent Rad51 regulation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:746. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03159-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartwell LH, Szankasi P, Roberts CJ, Murray AW, Friend SH. Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science. 1997;278:1064–8. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas MD, Kremer CS, Ravichandran KS, Rajewsky K, Bender TP. c-Myb is critical for B cell development and maintenance of follicular B cells. Immunity. 2005;23:275–86. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tartey S, Matsushita K, Imamura T, Wakabayashi A, Ori D, Mino T, et al. Essential function for the nuclear protein Akirin2 in B cell activation and humoral immune responses. J Immunol. 2015;195:519–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolence JJ, Gwin KA, Shapiro MB, Hsu FC, Shapiro VS, Medina KL. Cell extrinsic alterations in splenic B cell maturation in Flt3-ligand knockout mice. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2015;3:103–17. doi: 10.1002/iid3.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ludwig J, Federico G, Prokosch S, Kublbeck G, Schmitt S, Klevenz A, et al. Dickkopf-3 acts as a modulator of B cell fate and function. J Immunol. 2015;194:2624–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balazs M, Martin F, Zhou T, Kearney J. Blood dendritic cells interact with splenic marginal zone B cells to initiate T-independent immune responses. Immunity. 2002;17:341–52. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guerra FM, Gommerman JL, Corfe SA, Paige CJ, Rottapel R. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase (HIPK)-1 is required for splenic B cell homeostasis and optimal T-independent type 2 humoral response. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu H, Awasthi A, White GC, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Malarkannan S. Rap1b regulates B cell development, homing, and T cell-dependent humoral immunity. J Immunol. 2008;181:3373–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Murcia JM, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Ricoul M, Dutrillaux B, Mark M, et al. Requirement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in recovery from DNA damage in mice and in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7303–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corral J, Yelamos J, Hernandez-Espinosa D, Monreal Y, Mota R, Arcas I, et al. Role of lipopolysaccharide and cecal ligation and puncture on blood coagulation and inflammation in sensitive and resistant mice models. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1089–98. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masson M, Niedergang C, Schreiber V, Muller S, Menissier-de MJ, de Murcia G. XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3563–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg N, Baltimore D, Scher CD. In vitro transformation of lymphoid cells by Abelson murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1932–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaumeil J, Micsinai M, Skok JA. Combined immunofluorescence and DNA FISH on 3D-preserved interphase nuclei to study changes in 3D nuclear organization. J Vis Exp. 2013;72:e50087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.