Abstract

Background

Smart pump–electronic health record (EHR) interoperability has been demonstrated to reduce adverse events and increase documentation and billing accuracy. However, relatively little is known about the impact of interoperability on infusion therapy billing claims and hospital finances.

Objective

Our objective was to evaluate the association between smart pump–EHR interoperability with auto-documentation and current procedural terminology (CPT®)-coded infusion-therapy billing claims submissions.

Methods

At Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health (Lancaster, PA, USA), infusion-therapy billing data were collected for 158,379 patient days (a visit to the emergency department [ED] or 24 h admission to a non-ED unit) and divided into two groups: 78,241 pre- and 80,138 post-auto-documentation. The count and types of submitted CPT-coded claims were analyzed for ED/non-ED groups, inpatient/outpatient status and non-ED unit where the infusion was administered. Dollar amounts for CPT codes were calculated using Medicare Addendum B 2017. Patient day and CPT code counts were converted to annualized values to facilitate analysis.

Results

Patient days did not increase significantly from pre- to post-auto-documentation, whereas annualized submitted CPT-coded claims increased significantly by 14.5% (p < 0.001). The corresponding billing claim dollar value increased by $US1,147,652 (13.5%). ED patient days increased by 2.0% (p = 0.44), whereas submitted CPT-coded claims increased significantly by 4.0% (p < 0.001) and $US478,980 (7.4%). Non-ED patient days increased by 2.8% (p = 0.2), whereas CPT-coded claims increased significantly by 31.7% (p < 0.001) and $US668,672 (34.0%). The total number of submitted CPT-coded claims increased by 13.4% for inpatients and 12.3% for outpatients.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that auto-documentation of infusion-therapy services may have a positive impact on hospital financial performance, which could help drive adoption of this technology.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| The implementation of smart pump–electronic health record interoperability to auto-document intravenous infusion start and stop times was associated with an increased amount of infusion-related billing claims submitted at a community hospital. |

| Even though the number of patient days showed no significant increase, post-auto-documentation billing claims submissions increased significantly in the overall study population, emergency department (ED) and non-ED units, and for both inpatients and outpatients. |

| The $US1,147,652 increase in billing claims post-auto-documentation comprised $US478,980 for the ED and $US668,672 for the 12 non-ED units studied. |

Introduction

Background/Rationale

Smart pump–electronic health record (EHR) interoperability, also referred to as integration, is the most recent advancement in infusion-therapy safety technology; however, relatively little data have been published on the associated financial impact. The integration of these two systems enables automatic pre-programming of the pump with the physician-ordered, pharmacist-reviewed infusion parameters from the EHR and automatic, time-stamped documentation of infusion-related data in the EHR. Both advanced features increase medication safety and provide complete, accurate, and timely data for clinicians and billing staff. The interoperability safety impact comes from a reduction in the probability of intravenous infusion errors, which involve the administration of medications directly into a patient’s bloodstream and have the greatest potential for patient harm [1–6]. Yet, in 2018, smart pump–EHR interoperability is being used in roughly 200 hospitals, that is, in < 4% of the total hospitals in the USA [7]. As the Emergency Care Research Institute pointed out in its Guidance Article: Infusion Pump Integration, implementing interoperability can be “complex, difficult, and costly” [8]. The cost of interoperability implementation may require significant investments in the wireless infrastructure of the hospital, the EHR system, smart pumps, and safety software (which provides the bi-directional communication interface between the pumps and EHR).

While a growing body of literature documents the safety benefits [1–6] and the long-term commitment required to effectively implement this technology [8], evaluations and estimates of the financial impact have only just begun. A 2009 study of the return on investment of smart pump implementation calculated savings based on the dollars attributed to averted adverse drug events [9]. A 2017 news article reported that Ohio-based Union Hospital estimated an approximately $US2 million improvement in revenue capture from the implementation of smart pump–EHR interoperability, but no data were presented [10]. A recently published journal article from St. Vincent’s Healthcare included a brief report on the financial impact of interoperability but only in the dollars attributed to decreased lost charges and only on outpatient infusions [11]. The data sources and methods used to determine lost-charge amounts were not described, and detailed data were not provided.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between auto-documentation of infusion-therapy start and stop times provided by smart pump–EHR interoperability and the infusion therapy billing claims submissions at a community hospital. We also investigated the current procedural terminology (CPT®) codes [12] submitted for patients treated with infusion therapy before and after the implementation of auto-documentation to determine whether a relationship existed between auto-documentation and CPT-coded submissions.

Methods

Study Design

The data analyzed in this retrospective cohort study were from patients admitted to Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health (LG Health, Lancaster, PA, USA) during the 2016 and 2017 study periods. The data were evaluated to determine the effect of infusion pump–EHR interoperability with auto-documentation of start and stop times on CPT-coded billing claims. The LG Health Institutional Review Board approved this research. All authors accept responsibility for the details and accuracy of this analysis.

Setting

LG Health is a 663-licensed bed, not-for-profit health system that includes Women & Babies Hospital and Lancaster General Hospital, a level II trauma center, and a teaching hospital with a level III neonatal intensive care unit. LG Health is a member of the University of Pennsylvania Health System (Penn Medicine).

Participants

Convenience sampling was performed and all patients who attended the emergency department (ED) and non-ED units during the study periods were included in the analysis. The study evaluated patient days (admission to the ED or 1 day to a non-ED unit) assigned to two groups: those who received care pre-auto-documentation and those who received care post-auto-documentation. The number of ED days was determined by totaling the number of patient admissions to the ED during the study periods. The total number of days in the non-ED units was calculated by adding the total number of days patients spent in non-ED units to the total number of days in observation. Observation days were calculated by dividing the total number of observation hours by 24.

If patients attended the ED or were admitted to a non-ED unit, they were included in the patient day count but had to have a properly documented infusion for the encounter to be included in the billed therapy count. There were no patient exclusion criteria as the analysis focused on the number of patient days and the number of applicable CPT codes rather than specific patient characteristics. The non-ED hospital units included oncology, neuroscience, medical–surgical, cardiac telemetry, orthopedics, vascular surgery, observation unit, special care unit, triage, children’s health center, couplet care center, and women’s health center. Demographic and disease state information was not available or included in this analysis. Patients were categorized into groups based on department identification and outpatient versus inpatient status.

The ED and non-ED units were separated during analysis as they are considered to be independent of each other because of the differing services provided. The ED accepts patients without pre-scheduling, preparation, or known diagnosis, which may result in unpredictable workloads. The patient volume, emergency cases, and time constraints may lead to patient care prioritization over tasks such as billing documentation. Conversely, the care delivery workflow may be more predictable in non-ED units, potentially enabling increased prioritization of documentation-related tasks.

Variables

Study Intervention/Exposure

The study intervention was defined as the use of smart pump–EHR interoperability to auto-document infusion-therapy start and stop times. Interoperability was implemented in the study units between the Epic® EHR and ICU Medical Plum A+® infusion pumps and ICU Medical MedNet® safety software. The pre-auto-documentation group had auto-documentation of start time only; the post-auto-documentation group had auto-documentation of both start and stop times. Auto-documentation of start time was enabled through Epic-MedNet–Plum A+ interoperability at the time of infusion start in both groups. The processes to document infusion-therapy stop-time data differed between groups as follows:

Pre-auto-documentation: October 2015 to January 2016 (ED) and April 2016 to June 2016 (non-ED units)

When a patient status change triggered an admission, discharge, or transfer message, the clinician encountered a “hard stop” to complete documentation of infusion data. The infusion stop-time data were manually documented in the EHR before the patient was discharged. The pump-provided stop-time data were present on the MedNet server, but this group did not have a tool that enabled consistent access to that data to align the recorded stop time with the duration of the infusion or to identify the data source. Without an identified source or with a questionable duration, the data were not consistently judged to be sufficient for billing purposes. When an infusion record was incomplete, it was not submitted for infusion-therapy billing claims.

Post-auto-documentation: October 2016 to January 2017 (ED) and April 2017 to June 2017 (non-ED units)

Auto-documentation of stop time was enabled by transmission of Plum A+ infusion pump data from the MedNet server to the EHR through the use of the Epic Pump Rate Verify tool. Once data were transmitted to the EHR, auto-documentation required clinician review, data verification, and an active step to accept the data for chart entry. The transmitted data included clinical infusion details, stop times, and identification of the pump as the data source. With the combination of auto-documented infusion-therapy start and stop times, billing claims were supported for each infusion delivered.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of the study was the total count of all CPT codes submitted. The CPT code count was analyzed pre- and post-auto-documentation for the overall study population and for the ED, non-ED units, and individual non-ED units. The CPT coded count of intravenous infusions and injections during the study periods were identified from billing data. The CPT code count is interpreted with an understanding that an individual patient may have a CPT code count less than, equal to, or more than their total number of patient days. This variation in count is expected because of variations in therapeutic course and documentation practice. Additional details on infusion-therapy CPT codes are presented in “Appendix 1”.

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes included the individual CPT code count submitted and the corresponding Medicare Addendum B 2017 $US amounts [13], which were converted to annualized values. The comparison between groups was completed for the overall population, ED, non-ED, and individual non-ED unit patient populations. An additional analysis included identification of the CPT codes that increased and decreased to the greatest degree by ED and non-ED, inpatient and outpatient status, and unit where the infusion was administered. Demographic and disease state details are not included in the data set, so a comparison by these characteristics was not undertaken, which represents a limitation of this study. Additional details on Medicare Addendum B 2017 infusion-therapy rates are presented in “Appendix 2”.

Data Sources/Measurement

Reports were generated from the EPSi Decision Support System using Business Objects and Excel Power Pivot by submitting queries related to individual CPT codes used during the study period in the ED and non-ED units. These reports were analyzed to identify the number of patient days, number and type of submitted CPT code billings, type of visit (inpatient or outpatient), and unit where the infusion was administered. The sampling was performed without bias.

Statistical Methods

The statistical data analysis was carried out without bias after validation of raw data CPT codes, counts, and corresponding dollar amounts associated with the respective analyses. The number of billings and patient days were expressed as counts and converted to annualized figures to facilitate analysis. The ED study periods were 4 months in length and were annualized by multiplying by 3. The non-ED study periods were 3 months long and were annualized by multiplying by 4. The number of billings was compared across the two time periods by CPT code and type of visit (inpatient vs. outpatient) for both the ED and the non-ED units. Comparisons using descriptive statistics were also made based on the type of medical unit where the infusion was ordered. We used the Chi squared test to determine the associations between the variables, and used the z-test to test proportions. Data were managed in Microsoft® Excel, and all the analyses were performed in R (v. 3.4.1).

Results

Participants

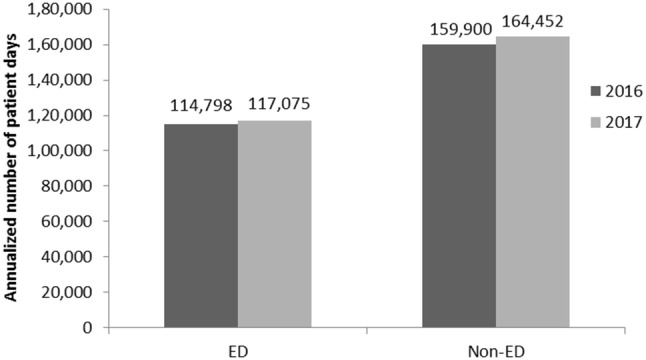

The study periods included a total of 158,379 patient days (78,241 pre- and 80,138 post-auto-documentation), all of which were eligible for inclusion. Annualized patient counts for ED (2%) and non-ED (2.8%) increased from 2016 to 2017, but the difference did not reach significance (p > 0.05 for both; Fig. 1). Demographic details of the patients were not available so are not included. Data were sampled from closed hospital admission records without a longitudinal component.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of annualized 2016 and 2017 overall patient days for ED and non-ED groups ED Emergency Department

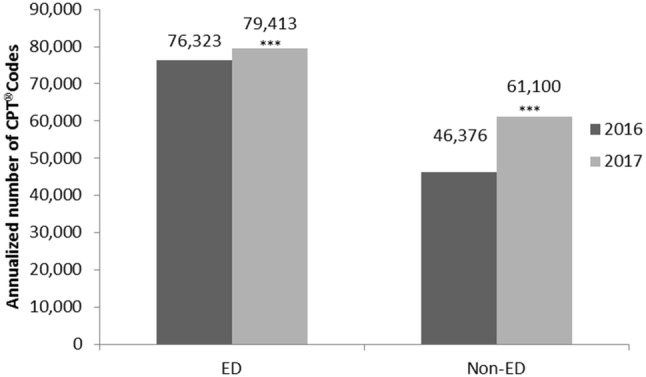

Primary Outcome: Quantity of Submitted Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Codes

As shown in Fig. 2, the implementation of auto-documentation was associated with increased annualized overall submitted CPT counts in both study groups. The quantity of submitted CPT codes increased in the overall population from 122,699 to 140,513, a 14.5% increase (p < 0.001). The ED population showed an increase in annualized CPT codes from 76,323 to 79,413, a 4.0% increase (p < 0.001). In the non-ED units, annualized CPT codes increased from 46,376 to 61,100, a 31.7% increase (p < 0.001). Similar results were obtained on comparing the annualized CPT code count/patient day ratios (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of 2016 and 2017 annualized billed therapies for ED and non-ED groups. CPT current procedural terminology, ED emergency department. ***p < 0.001

Table 1.

Comparison of 2016 and 2017 CPT® codes/patient day by department

| Annualized proportion of CPT® codes/patient day | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | No. of CPT codes (2016) | No. of CPT codes (2017) | No. of patient days (2016) | No. of patient days (2017) | Proportion 1 (2016) | Proportion 2 (2017) | % change | p value |

| ED | 76,323 | 79,413 | 114,798 | 117,075 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 2.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Non-ED | 46,376 | 61,100 | 159,900 | 164,452 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 28.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Total | 122,699 | 140,513 | 274,698 | 281,527 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 11.7 | < 0.0001 |

CPT current procedural terminology, ED emergency department

Other Analyses: Secondary Outcomes

Overall population: Quantity and Corresponding Dollar Value of Individual CPT Changes

The implementation of auto-documentation was associated with variable changes to individual CPT codes (Table 2). In the overall population, seven of ten infusion-therapy CPT codes showed significant increases from 2016 to 2017. The greatest increase in count was observed with CPT code 96361 (hydration, additional), which accounted for 13,587 submissions pre-auto-documentation and 15,433 post-auto-documentation, an increase of 15% or 1846 submissions (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of 2016 and 2017 billed therapies by department and current procedural terminology code

| CPT® code count analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Description | CPT code | ED (4 months) | Non-ED (3 months) | Total | |||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | |||

| Hydration | Initial | 96360 | 1296 | 1504*** | 211 | 275** | 1507 | 1779*** |

| Additional | 96361 | 5895 | 5789 | 7692 | 9644*** | 13,587 | 15,433*** | |

| IV infusion | Initial | 96365 | 2484 | 3135*** | 246 | 404*** | 2730 | 3539*** |

| Additional | 96366 | 574 | 670** | 1399 | 1916*** | 1973 | 2586*** | |

| New drug | 96367 | 411 | 571*** | 66 | 96* | 477 | 667*** | |

| Concurrent | 96368 | 37 | 34 | 16 | 11 | 53 | 45 | |

| Injection | SC/IM | 96372 | 0 | 0 | 448 | 774*** | 448 | 774*** |

| Initial push | 96374 | 5596 | 5566 | 261 | 355*** | 5857 | 5921 | |

| Initial push, new drug | 96375 | 6666 | 6732 | 476 | 619*** | 7142 | 7351 | |

| Additional push, same drug | 96376 | 2482 | 2470 | 779 | 1181*** | 3261 | 3651*** | |

| Non-annualized total | 25,441 | 26,471*** | 11,594 | 15,275*** | 37,035 | 41,746*** | ||

| Non-annualized percent change | – | 4.0 | – | 31.7 | – | 12.7 | ||

| Annualized total | 76,323 | 79,413*** | 46,376 | 61,100*** | 122,699 | 140,513*** | ||

| Annualized percent change | – | 4.0 | – | 31.7 | – | 14.5 | ||

The 2017 counts are compared with the corresponding 2016 count

CPT current procedural terminology, ED emergency department, IM intramuscular, SC subcutaneous

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Individual CPT codes were used to estimate financial impact. The dollar value of the corresponding CPT codes was calculated by multiplying the annualized count of the CPT code increase (or decrease) with the corresponding Medicare Addendum B 2017 rate (Table 3). In the overall population, the largest financial increase was associated with CPT code 96365 (intravenous infusion, initial) at $US465,300. Additional codes associated with significant increases were 96360 (hydration, initial) and 96361 (hydration, additional). The increase in billing claims for the overall study population totaled $US1,147,652.

Table 3.

Emergency department vs. non-emergency department: Medicare Addendum B 2017 corresponding dollar amount ($US) change by current procedural terminology code

| Annualized Medicare Addendum B corresponding dollar amounts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Description | CPT® code | ED | Non-ED | Total |

| Hydration | Initial | 96360 | 112,320 | 46,080 | 158,400 |

| Additional | 96361 | <11,130> | 273,280 | 262,150 | |

| IV infusion | Initial | 96365 | 351,540 | 113,760 | 465,300 |

| Additional | 96366 | 10,080 | 72,380 | 82,460 | |

| New drug | 96367 | 25,440 | 6630 | 31,800 | |

| Concurrent | 96368 | – | – | – | |

| Injection | SQ/IM | 96372 | – | 69,112 | 69,112 |

| Initial push | 96374 | <16,200> | 67,680 | 51,480 | |

| Initial push, new drug | 96375 | 6930 | 20,020 | 26,950 | |

| Additional push, same drug | 96376 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 478,980 | 668,672 | 1,147,652 | ||

| Percentage change | 7.4 | 34.0 | 13.5 | ||

CPT current procedural terminology, ED emergency department, IM intramuscular, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous

Brackets around the number denote a decrease

When viewed independently, the ED and non-ED populations differed in the proportion of CPT codes used and the change after interoperability.

Emergency Department (ED) Population: CPT Codes

In the ED, the most prevalent group of CPT codes used were those in the “injection” category, which includes codes 96374, 96375, and 96376 (intravenous push, intravenous push new drug, additional intravenous push same drug), where interoperability with auto-documentation did not show a significant association (Table 2). Significant CPT count increases were seen for therapy delivered by infusion pump, including 96360 (hydration, initial) and all three intravenous infusion codes 96365, 96366, and 96367 (initial, additional, and new drug). CPT code 96372 (subcutaneous/intramuscular injection) was not used in the dataset of either group.

Non-ED Group: CPT Codes

In non-ED units, the distribution of CPT codes was weighted toward the hydration (96360 and 96361) and intravenous infusion (96365, 96366, 96367, and 96368) code groups (Table 2). Interoperability was associated with significant increases in all hydration and intravenous infusion codes, with the exception of 96368 (intravenous infusion, concurrent), which was less used and decreased in count from 16 to 11. The most prevalent CPT code by count was 96361 (hydration, additional), which was submitted 9644 times in the post-auto-documentation group, an increase of 1952 or 25% (p < 0.001).

Financial Impacts

When study period CPT code submissions were converted to annualized billing increases, the corresponding dollar amounts of Medicare Addendum B 2017 rates were $US668,672 for non-ED units and $US478,980 for the ED, for an estimated total of $US1,147,652 (Table 3). Billing claims and potential revenue do not represent the actual financial impact to the billing facility, as reimbursement may vary by payer contract, including by payment bundles and treatment scenarios.

In the ED, the greatest increases in billed therapies were related to CPT codes 96365 (intravenous infusion, initial; $US351,540), 96360 (hydration, initial; $US112,320), and 96367 (intravenous infusion, new drug; $US25,440). In non-ED units, the greatest increases in billed therapies were related to CPT codes 96361 (hydration, additional; $US273,280), 96365 (intravenous infusion, initial; $US113,760), and 96366 (intravenous infusion, additional; $US72,380). The largest decrease was observed in the ED, with code 96374 (injection, initial push; − $US16,200) and 96361 (hydration, additional; − $US11,130 ). No decreases were observed in the non-ED group.

CPT Code Change and Financial Impact, Inpatient vs. Outpatient: Overall Population

The increase in CPT code count was similar for inpatients and outpatients. In the overall population, the count of CPT submissions increased by 13.4% for inpatients (p < 0.001), 12.3% for outpatients (p < 0.001), and 12.7% for the overall population (non-annualized, p < 0.001; Table 4). The associated annualized financial impact was also similar, with $US536,940 of additional claims submitted for inpatients and $US610,712 for outpatients (Table 4). In the ED, the gains were focused on inpatients, with 99% of the financial impact coming from the inpatient population. In non-ED units, 90% of the financial gain came from outpatients (Table 5).

Table 4.

Overall impact of billed therapies between 2016 and 2017 (emergency and non-emergency department) for inpatients and outpatients

| Visit type | No. of billed therapies | % change in billed therapies | p value | Annualized financial change ($US) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | ||||

| Inpatient | 14,605 | 16,566 | 13.4 | < 0.001 | 536,940 |

| Outpatient | 22,430 | 25,180 | 12.3 | < 0.001 | 610,712 |

| Total | 37,035 | 41,746 | 12.7 | < 0.001 | 1,147,652 |

Table 5.

Cross-comparison of submitted CPT®-coded claims increases, 2016–2017, $US

| Department | Inpatient | Outpatient | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ED | 64,824 | 603,848 | 668,672 |

| ED | 472,116 | 6,864 | 478,980 |

| Total | 536,940 | 610,712 | 1,147,652 |

ED emergency department

Non-ED Units Comparison by Unit

CPT code count and financial impact varied by individual non-ED units (Table 6). CPT code count increased in 7 of 11 units. The largest increase in count was observed in the cardiac telemetry unit, with an increase from 95 to 1739 (1644 count increase, 1731%; p < 0.001). The dollar amount of submitted CPT codes increased in 8 of 11 units, with the cardiac telemetry unit again reporting the highest increase in claims ($US279,356).

Table 6.

Non-emergency department: comparison of number of billed therapies, 2016 vs. 2017

| Unit | No. of billed therapies | % change in billed therapies | p value | Annualized financial change ($US) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | ||||

| Cardiac telemetry | 95 | 1739 | 1730.5 | < 0.001 | 279,356 |

| Children’s health | 1460 | 1303 | <10.8> | – | <27,040> |

| Neuroscience | 91 | 701 | 670.3 | < 0.001 | 95,164 |

| Medical-surgical | 241 | 2153 | 793.4 | < 0.001 | 267,764 |

| OB & GYN | 365 | 340 | <6.8> | 0.969 | 5240 |

| Observation unit | 8503 | 7283 | <4.3> | – | <141,776> |

| Oncology | 0 | 347 | – | < 0.001 | 53,912 |

| Orthopedics | 4 | 359 | 8875 | < 0.001 | 55,004 |

| Special care | 572 | 224 | <60.8> | – | <56,004> |

| Triage | 249 | 477 | 91.6 | – | 88,812 |

| Vascular surgery | 14 | 349 | 2392.9 | < 0.001 | 48,240 |

ED emergency department, OB & GYN obstetrics and gynecology

Brackets around the number denote a decrease

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, a higher CPT code submission count was observed when infusion therapy was administered with auto-documentation of infusion start and stop times enabled by smart pump–EHR interoperability. The increase in CPT count was present in each studied population group (overall, ED, and non-ED) and was associated with increased corresponding dollar amounts of billing claims calculated from Medicare Addendum B 2017 rates. It is notable that the number of patient days exceeded the number of submitted CPT codes. This may partly be because patients may receive no infusion therapy and some may experience a number of therapies less than, equal to, or more than the number of patient days. It is also possible that delivered therapies may not have been properly documented and thus not have been entered into the billing database with an associated CPT code.

The count of CPT codes increased significantly, whereas patient volumes did not show significant growth. This finding was present in raw data counts and in the ratio of CPT codes to patient days. Although the disease state and demographic data of the patient population were unknown, no information was identified that suggested a significant shift in comorbidities or administrative procedures accounted for the difference in delivered therapies. Alternatively, CPT code count increases may be related to auto-documentation of stop times. Before auto-documentation of stop times, clinicians recorded times manually during care, transfers, or discharges. Like all manual practices, the clinician data entry procedure was at risk of error and omission. The resulting documentation, if judged inadequate by coders may have led to reduced billing submissions. Auto-documenting precise stop times by transferring data directly from the server ensured accuracy and enabled identification of the pump as the data source. It is important to note that auto-documentation required clinician review, data verification, and an active step to accept the data for chart entry. As a result, auto-documentation requires its own steps to be adopted and accountability to ensure consistent implementation.

Interoperability was associated with variable CPT code impact on the overall population. We expected that interoperability would positively impact CPT codes associated with infusion pump-delivered therapies (hydration, intravenous infusion) more than it would those medications delivered by injection (intravenous push, subcutaneous, or intramuscular). The data support this hypothesis by demonstrating significant increases in both hydration codes (initial 96360, additional 96361) and three of four intravenous infusion codes (initial 96365, additional 96366, new drug 96367). The intravenous infusion code that showed a decrease in count was concurrent delivery (96368), which made up a small portion of delivered infusions. The decrease in the use of code 96368 did not reach significance, and the small associated counts precluded analysis. In the injection category, 96372 (subcutaneous/intramuscular injection) increased, as did 96376 (additional intravenous push, same drug); however, these changes were driven entirely by changes in non-ED units, which is discussed in the following and may not be a direct result of interoperability.

In this study, the total annualized increase in the value of the corresponding Medicare Addendum B 2017 rates was $US1,147,652. When divided by study groups, the increase was $US478,980 for the ED and $US668,672 for non-ED units. The net hospital revenue associated with these codes is subject to a highly complex analysis of payer mix, reimbursement contracts, etc. and is beyond the scope of this study. To determine the potential return on investment with this technology, hospitals also need to account for the significant potential investments associated with the wireless infrastructure of the hospital, the EHR system, smart pumps, and safety software.

Evaluation of CPT codes and financial impact in the ED led to several important observations. The 7.4% increase in submitted charges is greater than the 4% increase in CPT count, which suggests that the post-auto-documentation CPT codes shifted to those with higher reimbursement rates. For example, submission of CPT code 96365 (intravenous infusion, initial; Medicare Addendum B 2017 rate $US179.77) increased by 26%, and CPT code 96360 (hydration, initial; Medicare Addendum B 2017 rate $US179.77) increased by 17%. The combination of 96365 and 96360 accounted for $US463,860 of the total $US478,980 of increased claims. The CPT codes associated with non-infusion pump injections (96374, 96375, and 96376) showed minimal change.

The unchanged count of CPT code 96374 (intravenous push, initial) was somewhat unexpected, as we hypothesized that hydration and intravenous infusions with incomplete data may be “down-coded” to intravenous pushes at the time of billing submission because of a lack of documented support for a completed infusion. In this study, it appears that down-coding was not prevalent with billing records from the ED. An alternative explanation for the gains in initial hydration and infusion with no change in intravenous push is that hydration and intravenous infusions with incomplete documentation were not submitted for billing charges at all and that intravenous pushes were documented consistently in both groups. If the prevalent practice is not submitting rather than down-coding incomplete records, the financial implications may be considerable. A down-code may not lead to a substantial change in revenue as “intravenous push, initial” is also valued at $US179.77 by Medicare Addendum B 2017. Conversely, not billing leads to a total loss. It is also noted that CPT 96372 (subcutaneous/intramuscular injection) was not submitted in the ED, which suggests this route of administration was rarely, if ever, used. Billing practices and automation should also be scrutinized for potential for “up-coding,” but evidence thus far suggests up-coding is not a significant phenomenon in the healthcare industry [14–17].

In non-ED units, auto-documentation of stop times led to a 31.7% increase in the count of CPT codes submitted and a 34.0% increase in submitted charges. The increase in charge percentage exceeds the CPT count growth, which suggests that the submitted codes contribute to the revenue by increased count and a shift toward codes with higher reimbursement. The greatest change was seen with CPT 96361 (hydration, additional), which increased by 25% and corresponded to a $US273,280 increase by Medicare Addendum B 2017 rates. Additional significant growth was seen in “hydration, initial”, three of four intravenous infusion codes, and all injection codes. The broad-based growth in CPT count in the non-ED group suggests that interoperability was associated with a significant shift in billing practices and that many treatments were not being submitted before auto-documentation. The growth of the hydration and infusion codes is readily explained by auto-documentation but the growth of the injection codes is not. It may be that an emphasis on billing practices with the roll-out of auto-documentation also carried over into improved billing of non-infusion pump injection medications. Alternative explanations may include improved billing documentation training, new staff, and increased managerial scrutiny of billing practices.

The data captured by auto-documentation shine a light on areas that may have previously gone unrecognized. In this study, the largest increases in billing claims were from ED inpatients and non-ED outpatients. ED inpatients accounted for $US472,116 of additional charges, whereas outpatients accounted for $US6864 of charge growth; in non-ED units, outpatients accounted for $US603,848 of the $US610,712 increase. One possible explanation for increases in the ED is that pre-auto-documentation, inpatients who were transferred out of the ED with running infusions may have had incomplete charting associated with transition of care processes, resulting in lost billing opportunities. Post-auto-documentation, a running infusion could be documented properly using the infusion data recorded in the server before or after the patient transfer between units. This change may explain the growth in the number of CPT 96360 (hydration, initial) and 96365 (intravenous infusion, initial) codes observed in the post-auto-documentation group. In non-ED units, most CPT count increases occurred with outpatients. Further research is required to evaluate these results.

When the non-ED group was viewed by unit, significant changes were evident. CPT code submission increased by significant amounts in orthopedics, cardiac telemetry, medical–surgical, neuroscience, and oncology. The magnitude of change in these individual units exceeds the change in the overall group, suggesting that the implementation of auto-documentation in these units overcame significant hurdles related to proper documentation of infusion stop times. It is also possible that the emphasis on proper documentation with interoperability facilitated broad changes in billing practice that led to the capture of the additional injection category CPT codes.

Interpretation, Generalizability

As hospitals operate on increasingly narrow margins, “financial stewardship” is a growing part of infusion management responsibilities, with regard to both medications and medication safety technologies. Compliance with the use of medication safety technology needs to be monitored and improved as part of medication safety efforts. The results of this study point to another need, that is, improvement in financial performance. Previous publications have reported dollars from averted errors and reductions in lost income [9–11], which may be difficult to equate to a specific dollar amount. However, the improved data that come from using medication safety technology may be associated with gains of specific dollar amounts, as in this study. Although the actual revenue to the hospital was out of scope, this analysis demonstrates that the increase in billing amounts observed after the implementation of auto-documentation was substantial and provides detailed evidence of the potential financial benefits of smart pump–EHR interoperability.

This is the first study to use CPT codes as the basis for gathering and analyzing data to evaluate the association between smart pump–EHR interoperability with auto-documentation and the count and type of submitted intravenous infusion billing claims. Smart pump–EHR interoperability and auto-documentation of start and stop times provides the complete, credible data required to capture revenues through accurate documentation of reimbursement claims. The results suggest that smart pump–EHR interoperability auto-documentation may be associated with an estimated $US1.14 million of increased billing claims. While billing claims do not equal actual reimbursement, the volume of the increase suggests that auto-documentation-related billing claims effects are significant, definitely noteworthy, and may have a positive impact on hospital financial performance. Furthermore, the findings of such increases in multiple unique care units supports the generalizability of these results to other healthcare settings. It should also be noted that valid concerns have been raised about higher reimbursements through technology and documentation cascading into higher insurance costs for patients. However, Howley et al. [16] suggested that greater reimbursement is a result of “better care” being administered to patients. Indeed, studies in Canada [18] and the USA [19] have demonstrated a higher quality of care. Moreover, hospitals with comprehensive EHR coverage reported moderately lower costs of care than hospitals without EHR [20], which ties in to potential savings for patients.

Limitations

Although data from the two study groups were matched by month of year, data were not matched by demographic or treatment characteristics, which may affect submitted billing claims. The cross-sectional nature of the data means that causal inferences cannot be made from the study results. Further, it is possible that extending the data analysis period might yield different results. The CPT-code count may not represent the number of infusion therapies actually delivered during the study periods since it is possible that an admitted patient received an infusion that was not documented properly. Billing claims and potential revenue do not represent the actual financial impact to the billing facility, as reimbursement may vary by payer contract, including by payment bundles and treatment scenarios.

Conclusion

The process to implement interoperability is complex and costly and requires significant resources for introduction and maintenance over time. A potential limitation to the adoption of this technology is the lack of data on its potential financial benefits. The current study addresses this gap by generating evidence supporting the value of smart pump–EHR interoperability in improving hospital financial performance through its association with charge capture and billing compliance. We demonstrate, at the individual CPT-code level, the effect of interoperability and auto-documentation of infusion data, including accurate, time-stamped start and stop times, on the submission of complete and accurate billing claims. These results from a community hospital may help drive adoption of this technology by adding financial benefits to the recognized safety impact of smart pump–EHR interoperability. Additional long-term studies will be required to confirm these results.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ramu Periyasamy (Indegene, Pvt. Ltd.) for manuscript editing and statistical analysis and Sally Graver (Sally Graver Productions) for writing support. We also thank Linda Massey (Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health) for expert contributions on infusion therapy billing requirements. The interpretation of the data and the conclusions of this article are those of the authors alone.

Appendix 1: Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Codes Used [12]

| CPT® code | Description |

|---|---|

| Initial CPT codes | |

| 96360 | IV infusion, hydration; initial, 31 min to 1 h |

| 96365 | IV infusion, for therapy, prophylaxis, or diagnosis (specify substance or drug); initial, up to 1 h |

| 96372 | Therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic injection (specify substance or drug); subcutaneous or intramuscular |

| 96374 | Therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic injection (specify substance or drug); IV push, single or initial substance/drug |

| Additional CPT codes | |

| +96361 | IV infusion, hydration; each additional hour (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

| +96366 | IV infusion, for therapy, prophylaxis, or diagnosis (specify substance or drug); each additional hour (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

| +96367 | IV infusion, for therapy, prophylaxis, or diagnosis (specify substance or drug); additional sequential infusion of a new drug/substance, up to 1 h (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

| +96368 | IV infusion, for therapy, prophylaxis, or diagnosis (specify substance or drug); concurrent infusion (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

| +96375 | Therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic injection (specify substance or drug); each additional sequential IV push of a new substance/drug (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

| +96376 | Therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic injection (specify substance or drug); each additional sequential IV push of the same substance/drug provided in a facility (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

To meet Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requirements for reimbursement, an intravenous infusion therapy claim must be submitted with a CPT code and precise start and stop times. Without these, a claim might be downgraded to a lower reimbursement rate or not submitted. Infusion therapy CPT codes are of three categories: hydration, intravenous infusion, and injection. For billing coders, “poor documentation” is any documentation that lacks the specific information needed to assign accurate diagnosis and procedure codes such as CPT codes

CPT® is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association

CPT current procedural terminology, IV intravenous

Appendix 2: Medicare Addendum B 2017 Infusion-Therapy Rates [13]

| HCPCS code | Short descriptor | Payment rate ($US) |

|---|---|---|

| 96360 | Hydration IV infusion unit | 179.77 |

| 96361 | Hydrate IV infusion add-on | 34.78 |

| 96365 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic IV infusion unit | 179.77 |

| 96366 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic IV infusion add-on | 34.78 |

| 96367 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic additional sequence IV infusion | 53.17 |

| 96368a | Therapeutic/diagnostic concurrent infusion | |

| 96369 | SC therapeutic infusion up to 1 h | 179.77 |

| 96370 | SC therapeutic infusion additional h | 34.78 |

| 96371 | SC therapeutic infusion reset pump | 53.17 |

| 96372 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic injection SC/IM | 53.17 |

| 96373 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic injection IA | 179.77 |

| 96374 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic injection IV push | 179.77 |

| 96375 | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic injection new drug add-on | 34.78 |

| 96376a | Therapeutic/prophylactic/diagnostic injection same drug add-on |

CPT® codes align with HCPCS codes and are associated with variable corresponding dollar amounts

HCPCS healthcare common procedure coding system, IM intramuscular, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous, IA intra-arterial

aCodes 96368 and 96376 are not reimbursed

Author Contributions

TMS and JWB contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript drafting. MR and ME contributed to the critical appraisal of the manuscript content. KP acquired and analyzed the study data and provided input on the manuscript content. LJPT contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript drafting.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

Funding for statistical analysis and editorial support for this study was provided by ICU Medical, Inc.

Conflict of interest

John Beard is an employee and shareholder of ICU Medical Inc. Tina Suess, Michael Ripchinski, Matthew Eberts, and Kevin Patrick have not received personal compensation for their roles in this study. Leo J.P. Tharappel is an employee of Indegene, Inc. which was contracted to perform statistical analysis for this study. LG Health provided marketing and consulting services to ICU Medical pursuant to a professional services and consulting agreement.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of LG Health institutional policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval and informed consent were not required for this study.

References

- 1.Williams C, Maddox RR. Implementation of an i.v. medication safety system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:530–536. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.5.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskew JA, Jacobi J, Buss W, Warhurst HM, Debord CL. Using innovative technologies to set new safety standards for the infusion of intravenous medications. Hosp Pharm. 2002;37:1179–1189. doi: 10.1177/001857870203701112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatcher I, Sullivan M, Hutchinson J, Thurman S, Gaffney FA. An intravenous medication safety system: preventing high-risk medication errors at the point of care. J Nurs Admin. 2004;34:437–439. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson K, Sullivan M. Preventing medication errors with smart infusion technology. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:177–183. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fields M, Peterman J. IV medication safety system averts high-risk medication errors and provides actionable data. Nurs Admin Quart. 2005;29:77–86. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200501000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohashi K, Dalleur O, Dykes PC, Bates DW. Benefits and risks of using smart pumps to reduce medication error rates: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2014;37:1011–1020. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul H, Paul W. Smart pump/EMR interoperability 2017: first look at interoperability performance. 2017. KLAS. https://klasresearch.com/report/smart-pump-emr-interoperability-2017/1197. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

- 8.ECRI Institute Infusion pump integration. Health Dev. 2013;42(7):210–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danello SH, Maddox RR, Schaack GJ. Intravenous infusion safety technology: return on investment. Hosp Pharm. 2009;44(680–7):96. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miliard M. How smart pump EHR integration could save a community hospital $2 million. August 31, 2017. Available at: https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/how-smart-pump-ehrintegration-could-save-community-hospital-2-million. Accessed 22 Feb 2019.

- 11.Biltoft J, Finneman L. Clinical and financial effects of smart pump-electronic medical record interoperability at a hospital in a regional health system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1064–1068. doi: 10.2146/ajhp161058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Medical Association. CPT® (Current Procedural Terminology). Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt-current-procedural-terminology. Accessed 31 Aug 2018.

- 13.Medicare Addendum B 2017. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/apps/ama/license.asp?file=/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospitaloutpatientpps/Downloads/2017-April-Addendum-B.zip. Accessed 31 Aug 2018.

- 14.Adler-Milstein J, Jha AK. No evidence found that hospitals are using new electronic health records to increase Medicare reimbursements. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1271–1277. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowrisankaran G, Joiner K, Lin J. Does hospital electronic medical record adoption lead to upcoding or more accurate coding? 2016. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5345/4f90fe0248ccabbae1d005484678cff7515a.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2018.

- 16.Howley MJ, Chou EY, Hansen N, Dalrymple PW. The long-term financial impact of electronic health record implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:443–452. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb ML, Bohl DD, Fischer JM, et al. Electronic health record implementation is associated with a negligible change in outpatient volume and billing. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2017;46:E172–E176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collier R. National Physician Survey: EMR use at 75% CMAJ. 2015;187:E17–E18. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kern LM, Barron Y, Dhopeshwarkar RV, Edwards A, Kaushal R, HITEC Investigators Electronic health records and ambulatory quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:496–503. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen J, Epane J, Weech-Maldonado R, Shan G, Liu L. EHR adoption and cost of care—evidence from patient safety indicators. J Health Care Finance. 2015;41(4):1–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of LG Health institutional policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.