Abstract

Campylobacter species are among the leading cause of bacterial foodborne and waterborne infections. In addition, Campylobacter is one of the major causative agent of bacterial gastrointestinal infections and the rise in the incidence of Campylobacter infections have been reported worldwide. Also, the emergence of some Campylobacter species as one of the main causative agent of diarrhea and the propensity of these bacteria species to resist the actions of antimicrobial agents; position them as a serious threat to the public health. This paper reviews Campylobacter pathogenicity, infections, isolation and diagnosis, their reservoirs, transmission pathways, epidemiology of Campylobacter outbreaks, prevention and treatment option, antibiotics resistance and control of antibiotics use.

Keywords: Campylobacter, Gastrointestinal, Pathogenesis, Infection, Toxins, Resistance, Microbiology

Campylobacter; Gastrointestinal; Pathogenesis; Infection; Toxins

1. Introduction

Campylobacter belong to a distinct group of specialized bacteria designated rRNA superfamily VI of Class Proteobacteria (Allos, 2011). Campylobacter species are slender Gram-negative rod-shaped, spiral-shaped with single or pair of flagella. Some Campylobacter species have multiple flagella such as C. showae while some species are non-motile like C. gracilis (Acke, 2018). Campylobacter species are indole negative, oxidase positive, hippurate positive, catalase positive, nitrate positive and glucose utilization negative (Pal, 2017). Campylobacter species are closely related group of bacteria that principally colonise the gastrointestinal tracts of different animals (El-Gendy et al., 2013). Campylobacter species are enormous significance due to the increase in number of species implicated in animals and human's infections (Jamshidi et al., 2008; Kaakoush et al., 2015). Since its first identification, the number of pathogenic Campylobacter species that causes animal and human infections are largely classified through phylogenetic means with few as 500–800 bacteria ingestion dose resulting to human disease (Frirdich et al., 2017; Kaakoush et al., 2009). Nonetheless, report has shown that Campylobacter doses of 100 cells or less have been linked with human infections (Tribble et al., 2010). The major infection caused by Campylobacter is mainly acute diarrhea (Allos et al., 2013; Blaser, 2008) and since 1977, Campylobacter species have been known as the major causative agent of acute diarrhea (Skirrow, 1977). Campylobacter species have also been reported to be implicated in various human systemic infections including septic thrombophlebitis, endocarditis, neonatal sepsis, pneumonia (Alnimr, 2014), bloodstream infections (BSIs) (Morishita et al., 2013), acute colitis of inflammatory bowel disease and acute appendicitis (Lagler et al., 2016). Other major post-infections that significantly add to Campylobacter disease burden include severe demyelinating neuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) (Scallan et al., 2015), sequelae and Miller-Fisher syndrome (MFS) (Skarp et al., 2016). Campylobacter species are also associated with series of gastrointestinal infections like colorectal cancer and Barrett's esophagus (Man, 2011). In small group of patients, Campylobacter species have also been reported to be associated with extragastrointestinal infections such as brain abscesses, meningitis, lung infections, bacteremia and reactive arthritis (Man, 2011).

Campylobacter is a significant zoonotic causes of bacterial food-borne infection (Hsieh and Sulaiman, 2018) and farm animals are the major reservoir of Campylobacter species and the major cause of campylobacteriosis (Grant et al., 2018). Worldwide, farm animals are also the major cause of both bacteria food poisoning (Del Collo et al., 2017) and Campylobacter foodborne gastrointestinal infections (Seguino et al., 2018). Campylobacter foodborne infection is a problem and an economic burden to human population which caused about 8.4% of the global diarrhea cases (Connerton and Connerton, 2017). Campylobacter foodborne infection is a global concern because of the emerging Campylobacter species involved in both human infections and Campylobacter foodborne outbreaks (CDC, 2014). Campylobacter foodborne outbreak is defined as Campylobacter infection that involve more than two or more persons as a result of consumption of Campylobacter contaminated foods (Mungai et al., 2015). Majority of campylobacteriosis cases are not recognized as outbreaks rather as sporadic episode involving a single family group (Del Collo et al., 2017). Campylobacteriosis is a collective name of infections caused by pathogenic Campylobacter species and is characterized by fever, vomiting, watery or bloody diarrhea (Scallan et al., 2015). In general, Campylobacter infections are predominantly common in certain age group such as children (below 4) and the aged (above 75) (Lévesque et al., 2013). Other group of people at high risk of Campylobacter infections are immunocompromised individuals, hemoglobinopathies patients and those suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (Kennedy et al., 2004). In addition, the risks of Campylobacter infections are higher in high income nations than in low income nations (Platts-Mills and Kosek, 2014). In low income nations, a number of environmental sources pose a high risks of human Campylobacter infections (Lee et al., 2013); and most outbreaks are caused by consumption of poultry meats and poultry products (Taylor et al., 2013). Poultry meats include meats from laying hens, turkeys, ostriches, ducks and broilers (Epps et al., 2013), and poultry meats and it product cause about 60–80% of the global campylobacteriosis cases (EFSA, 2015).

2. Main text

2.1. Campylobacter species

Campylobacter species are divided into Lior serotypes and penner serotypes and over 100 Lior serotypes and 600 penner serotypes have been reported. Among these Lior serotypes and penner serotypes, only the thermotolerant Campylobacter species have been reported to have clinical significance (Garcia and Heredia, 2013).

2.1.1. Pathogenic Campylobacter species

Worldwide, pathogenic Campylobacter species are responsible for the cause of over 400–500 million infections cases each year. Pathogenic Campylobacter species known to be implicated in human infections includes C. jejuni, C. concisus, C. rectus, C. hyointestinalis, C. insulaenigrae, C. sputorum, C. helveticus, C. lari, C. fetus, C. mucosalis, C. coli, C. upsaliensis and C. ureolyticus (Heredia and García, 2018). These pathogenic Campylobacter species are grouped into major human enteric pathogens (C. jejuni, C. jejuni subsp. jejuni (Cjj), C. jejuni subsp. doyley (Cjd), C. coli and C. fetus); minor pathogens (C. concisus, C. upsaliensis, C. lari and C. hyointestinalis) and major veterinary pathogens (C. fetus subsp. venerealis (Cfv) and C. fetus subsp. fetus (Cff)) (Rollins and Joseph, 2000).

2.1.2. C. jejuni

C. jejuni is a motile, microaerophilic, zoonotic, thermophilic bacterial considered as the leading cause of worldwide foodborne bacterial gastroenteritis (Taheri et al., 2019). It's a member of the genus Campylobacter with polar flagella and helical morphology that is used for movement through viscous solutions including the mucus layer of the gastrointestinal tract (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011). C. jejuni is the major enteric pathogen that displays significant strain-to-strain dissimilarities in their pathogenicity patterns (Hofreuter et al., 2006). C. jejuni is the major species that caused infections than other pathogenic Campylobacter species (Liu et al., 2017) and also the major Campylobacter species that regularly cause diarrhea in human (Epps et al., 2013). Infections caused by C. jejuni can develop into diverse severities such as mild and self-limiting diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis and sometimes to meningitis and bacteremia (Burnham and Hendrixson, 2018; Dasti et al., 2010). C. jejuni infections are also associated with many secondary complications such as autoimmune neuropathy (Liu et al., 2018), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Drenthen et al., 2011; Loshaj-Shala et al., 2015). C. jejuni is the major Campylobacter species that cause disease in young people (Haddock et al., 2010). C. jejuni infections can occur via various routes such as through direct contact with companion and farm animals or through waterborne or foodborne transmission (Domingues et al., 2012). C. jejuni is a commensal bacterial of chickens which inhabit the chicken intestines at a level >106–108 CFU/g of chicken faeces (Oh et al., 2018) and chickens are the main vector for human campylobacteriosis (Hartley-Tassell et al., 2018). C. jejuni consist of two subspecies; C. jejuni subsp. jejuni (Cjj) and C. jejuni subsp. doyley (Cjd) (Man, 2011). The main phenotypic feature generally used to differentiate Cjj from Cjd strain is the inability of C. jejuni subsp. doyley to reduce nitrate and also, Cjd is also associated with high susceptibility to cephalothin. Clinically, Cjd strain causes both enteritis and gastritis (Parker et al., 2007). C. jejuni subsp. jejuni (Cjj) is the main bacterial cause of enteroinvasive diarrhea (Pacanowski et al., 2008) and the major symptoms of C. jejuni infections include severe enteritis, severe abdominal cramps, fever and bloody diarrhea with mucus (Biswas et al., 2011). In addition, C. jejuni has also been reported to be associated with immunoreactive complications like Miller-Fisher syndromes (Dingle et al., 2001).

2.1.3. C. coli

Campylobacter coli is an S-shaped curved cell measuring about 0.2–0.5 micrometers long with a single flagellum. It's very similar to C. jejuni; and both bacteria cause inflammation of the intestine and diarrhea in humans (Prescott et al., 2005). C. coli is the second most regularly reported Campylobacter species that causes human infections (Crim et al., 2015). C. coli is grouped into 3 clades (clade 1, 2 and 3). C. coli clade 1 includes most C. coli isolated from humans and farm animals. C. coli clade 1 causes most of human infections whereas infections cause by C. coli clade 2 and 3 are rare (Johansson et al., 2018). In high income countries, report has shown that C. coli is the second most regular cause of campylobacteriosis (Beier et al., 2018). Also in high income countries, C. coli infections are usually sporadic and it show seasonal drifts with majority of the infections occurring in early fall or late summer (Allos and Blaser, 2009). The clinical manifestations of C. coli infections include watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, inflammatory enterocolitis, malaise and nausea (Fitzgerald and Nachamkin, 2007).

2.1.4. C. fetus

C. fetus is a curved cell, fastidious motile bacterial that majorly cause septic abortion in farm animals. C. fetus can cause infection in human and its infection can be acquired through direct contact with animals, through consumption of undercooked contaminated meat or through ingesting food or water contaminated by animal faeces (Koneman et al., 1997). C. fetus is grouped into 3 subsp. which includes: C. fetus subsp. venerealis (Cfv), C. fetus subsp. testudinum (Cft) and C. fetus subsp. fetus (Cff) (Iraola et al., 2017). Cfv and Cff are associated with farm animal infections (Wagenaar et al., 2014); while Cft has also been reported to be associated with human infection such as bacteremia (Fitzgerald et al., 2014). Cff and Cfv are categorized on the basis of their clinical manifestations and mechanisms of transmission (Iraola et al., 2016). Cff caused abortion in infected sheep and cattle (On, 2013) and it's an opportunistic human pathogen that largely infects immunecompromised patients (Wagenaar et al., 2014). Cfv is reported to be cattle-restricted pathogen (Mshelia et al., 2010), but this species has been isolated from humans and most human infection caused by C. fetus strain is majorly caused by Cff (Patrick et al., 2013). Some of the major reported symptoms of C. fetus infections include endocarditis, meningitis, septicemia, septic arthritis, peritonitis and cellulitis (Hur et al., 2018). C. fetus is sometimes responsible for human systemic infections like bloodstream infection in immunosuppressed and immunocompromised individuals (Morishita et al., 2013), but infections are rare (Kienesberger et al., 2014).

2.1.5. C. lari

Campylobacter lari was previously called Campylobacter laridis and is part of the thermotolerant Campylobacter species. C. lari is grouped into a genotypically and phenotypically diverse Campylobacter group that encompasses of the nalidixic-acid susceptible (NASC) group, nalidixic acid-resistant thermophilic Campylobacter, the urease-positive thermophilic Campylobacter and the urease-producing NASC. These aforementioned groups are all identified as variants of C. lari group (Duim et al., 2004). This C. lari group is made up of five Campylobacter species (C. subantarcticus, C. insulaenigrae, C. volucris, C. lari and C. peloridis) with other group of strains called UPTC and C. lari-like strains (Miller et al., 2014). Though, some of these strains formally identified as C. lari group were later classified as novel taxa such as C. volucris (Debruyne et al., 2010) and C. peloridis (Debruyne et al., 2009). C. lari is a species within the genus Campylobacter and is grouped into two novel subsp. namely; C. lari subspe. concheus (Clc) and C. lari subsp. lari (Cll) (Miller et al., 2014). In 1984, C. lari was first reported in immunocompromised patient and since then sporadic cases including water-borne C. lari outbreaks have been reported (Martinot et al., 2001). C. lari has also been reported to be associated with enteritis, purulent pleurisy, bacteremia, urinary tract infection (Werno et al., 2002), reactive arthritis and prosthetic joint infection (Duim et al., 2004).

2.1.6. C. upsaliensis

Campylobacter upsaliensis is among the thermotolerant Campylobacter species and is mostly found in dogs and cats, regardless of whether the animal is sick or healthy (Jaime et al., 2002). C. upsaliensis is the third most Campylobacter species after C. jejuni and C. coli. C. upsaliensis was named after the city it was first described and thereafter, reports have emerged globally associating this species as a human bacterial enteropathogen (Bourke et al., 1998). C. upsaliensis is a well-known Campylobacter species that cause diarrhea in felines and canines (Steinhauserova et al., 2000). C. upsaliensis is well recognized as a clinically important emerging diarrhea pathogen in both pediatric and immunocompromised persons (Couturier et al., 2012). It is one of the emerging Campylobacter species that is associated with human infections including Crohn's disease, neonatal infection, bacteremia, abscesses, meningitis and abortion (Wilkinson et al., 2018). C. upsaliensis has also been reported to cause acute or chronic diarrhea in human and diarrhea in dogs (Cecil et al., 2012) though genetic studies have shown that Campylobacter strains isolated from dogs and human strains are different (Damborg et al., 2008). In many nations, C. upsaliensis is the second reported Campylobacter species that cause infections in human after C. jejuni (Premarathne et al., 2017).

2.1.7. Other pathogenic Campylobacter species

Other pathogenic Campylobacter species implicated in human infections includes C. mucosalis, C. curvus, C. insulaenigrae, C. doylei, C. concisus, C. helveticus and C. rectus (Cecil et al., 2012). Beside the well-known pathogenic species, other emerging species such as C. sputorum biovar sputorum, C. gracilis, C. ureolyticus, C. peloridis and C. showae, have also been reported to be implicated in causing human infections with some life-threatening complications in hospitalized patients (Nishiguchi et al., 2017). Some of these emerging Campylobacter species have also been isolated and detected in samples from the axillary nerve, soft tissue lesions, hepatic, lung, bone infections, the cerebrospinal, peritoneal fluid, genitalia, brain abscesses and thoracic empyema of hospitalized patients (Magana et al., 2017). In addition to these life-threatening complications caused by these emerging pathogens, there is a huge gap in tracing the connection between infection and source of human infection (Man, 2011). Furthermore, even with the global incidence of Campylobacter species in causing infections, the knowledge of the epidemiology and pathogenesis are still incomplete (Nielsen et al., 2006).

3. Pathogenicity of Campylobacter species

Campylobacter species are of economic importance as they constantly cause foodborne infections due to diverse genes involved in its pathogenicity (Bolton, 2015). Campylobacter pathogenicity is based on the virulence factors (Larson et al., 2008) and these virulence factors are multi-factorial in nature and the ability of these bacteria to survival and resist physiological stress also contributes to its pathogenicity (Casabonne et al., 2016; Ketley, 1995). The various virulence related mechanisms displayed by Campylobacter species includes invasive properties, oxidative stress defence, toxin production, iron acquisition and its ability to remain viable but non-culturable state (Bhavsar and Kapadnis, 2006). Campylobacter invasion, adherence and colonization also add to the pathogenicity of these groups of bacteria (Backert et al., 2013). Other virulence factors of Campylobacter include; secretion of some sets of proteins, translocation capabilities and flagella-mediated motility (Biswas et al., 2011).

3.1. Motility and flagella

Motility is important for Campylobacter survival under diverse chemotactic conditions it comes across in the gastrointestinal tract (Jagannathan and Penn, 2005). In some Campylobacter species, the motility system with the flagella involves a chemosensory system that steers flagella movement depending on the environmental conditions where these bacteria are found. Campylobacter chemotaxis and flagellin are the two important virulence factors that help lead these bacteria to its colonization site and also help in invading the host cell (van Vliet and Ketley, 2001). Some of these Campylobacter motility virulence factors and their encoding genes are σ54 promoter regulates gene (flaB) and σ28 promoter regulates gene (flaA) (Hendrixson, 2006). The flaA gene appears to be significant for invasion, colonization of the host epithelial cells and adherence to the host gastrointestinal tracts (Jain et al., 2008). The flagellum is composed of structural extracellular filamentous components and a hook-basal body. The hook-basal body comprises of the following: (a) the surface localized hook, (b) the periplasmic rod and associated ring structures and (c) a base embedded in the cytoplasm and inner membrane of the cell (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011). The hook-basal body is a complex component that is made up of a number of diverse proteins such as FliO, FlhA, FliG, FlhB, FliP, FliF, FliQ, FliR, FliY, FliM and FliN (Carrillo et al., 2004), FlgI, FlgH, FlgE, FliK, FlgE and FliK (Bolton, 2015). The extracellular filament of the flagella is composed of multimers of the protein including flagellin protein (FlaA and FlaB), FlaA (coded by flaA gene), and FlaB (coded by flaB gene) which is the minor flagellin protein (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011).

3.2. Chemotaxis

Chemotaxis is a method or system by which motile bacteria sense and move to the direction of more favourable conditions and several pathogenic bacteria uses this practice to invade their hosts (Chang and Miller, 2006). Campylobacter chemotaxis virulence factors involve in human infections includes chemotaxis proteins; Che A, B, R, V, W and Z encoded by cheA, cheB, cheR, cheV, cheW and cheZ genes (Hamer et al., 2010), Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins encoded by tlp4, tlp and tlp1 genes (Marchant et al., 2002), the CheY response regulator that is responsible for controlling flagella rotation encoded by cheY gene (Hermans et al., 2011) and Campylobacter energy taxis system proteins CetB (Aer2) and CetA (Tlp9) encoded by cetB and cetA gene (Golden and Acheson, 2002).

3.3. Adhesion

Campylobacter adherence to epithelial cells of the host gastrointestinal tract is a precondition for its colonisation mediated by some adhesins on the bacterial surface (Jin et al., 2001). Campylobacter adhesion virulence factors includes outer membrane protein encoded by cadF gene, Campylobacter adhesion protein A encoded by capA gene, phospholipase A encoded by pldA gene, lipoprotein encoded by jlpA gene, periplasmic binding protein encoded by peb1A gene, fibronectin-like protein A encoded by flpA and Type IV secretion system encoded by virB11 gene (Bolton, 2015). Campylobacter adhering to fibronectin F is another important Campylobacter virulence factor that enables these bacteria to bind to fibronectin which promotes the bacterium-host cell interactions and colonization (Konkel et al., 2010). Other virulence genes in Campylobacter species reported to be linked with human infections responsible for expression of colonization and adherence include racR, dnaJ, docA and racR genes (Datta et al., 2003).

3.4. Toxin production

Campylobacter produce different type of cytotoxins and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) is one of these toxins (Schulze et al., 1998). CDT is a tripartite toxin that is made up of three subunits encoded by the cdtA, cdtB and cdtC genes. Cytolethal distending toxin activity is determined by these three cdt cluster genes (Martinez et al., 2006). These three cdt cluster genes are all needed for these toxins to be active (Asakura et al., 2008). The cdtA and C genes are heterodimeric toxin subunits responsible for toxin binding and internalization of the host cell while cdtB is the subunit which encodes for the toxic/active components of the toxin (Abuoun et al., 2005). Cytolethal distending toxins induce diarrhea in both humans and animals by intrusive with the division of cells in the intestinal crypts (Carvalho et al., 2013).

3.5. Invasion

Invasion is another virulence mechanism in Campylobacter that is carried out by the flagella which also function as an export apparatus in the secretion of non-flagella proteins during host invasion (Poly and Guerry, 2008). There are many virulence genes that are involved in Campylobacter invasion mechanism and the products of these genes including flagellin C (flaC) and invasion antigens (cia) genes. These genes are transported into the host cell's cytoplasm with the aid of flagella secretion system which is vital for invasion and colonisation (Konkel et al., 2004). The secretion of invasion antigens and invasion protein B (ciaB) are also important virulence proteins synthesized by Campylobacter species which help in the epithelial cells invasion and adhesion of the host gastrointestinal tract (Casabonne et al., 2016). Other important virulence genes and proteins synthesized by Campylobacter species including the 73-kDa protein involved in adhesion, the invasion antigen C protein involved in full invasion of INT-407 cells, invasion associated protein gene (iamA) implicated in invasion and virulence, the periplasmic protein HtrA responsible for full binding to the epithelial cells, the HtrA chaperone implicated in full folding of out outer membrane protein, the CiaI gene implicated in intracellular survival (Bolton, 2015) and pldA and hcp genes responsible for the expression of invasion (Iglesias-Torrens et al., 2018).

3.6. Other virulence mechanism in Campylobacter species

Other virulence mechanism that adds to Campylobacter pathogenicity is the ability to obtain the necessary nutrient iron needed for its growth from the host body fluids and tissues (van Vliet and Ketley, 2001). Sialyltransferases (cstII) activity also add to Campylobacter pathogenicity by providing lipooligosaccharide with a defensive barricade that help facilitates in the disruption of the epithelial cells which mimic the action of human ganglioside inducing diarrhea (Pérez-Boto et al., 2010). The wlaN gene is implicated in lipopolysaccharide production (Wieczorek et al., 2018). The spot gene is responsible for extreme control (Gaynor et al., 2005), the Kat A (catalase) responsible to convert H2O2 to H2O and O2 (Bingham-Ramos and Hendrixson, 2008), the cj0012c and cj1371 proteins genes implicated to protect against reactive oxygen species (Garenaux et al., 2008). The Peb4 chaperone is another virulence mechanism in Campylobacter that play a significant role in the exporting of proteins to the outer membrane (Kale et al., 2011). Other virulence genes responsible for stress response genes includes the cosR, cj1556, spoT, ppk1, csrA, nuoK and cprS and the cell surface modifications genes (waaF, pgp1 and peb4) (García-Sánchez et al., 2019). All these aforementioned Campylobacter virulence-associated genes have all been reported to be implicated in human infections (Hansson et al., 2018).

4. Campylobacter infections

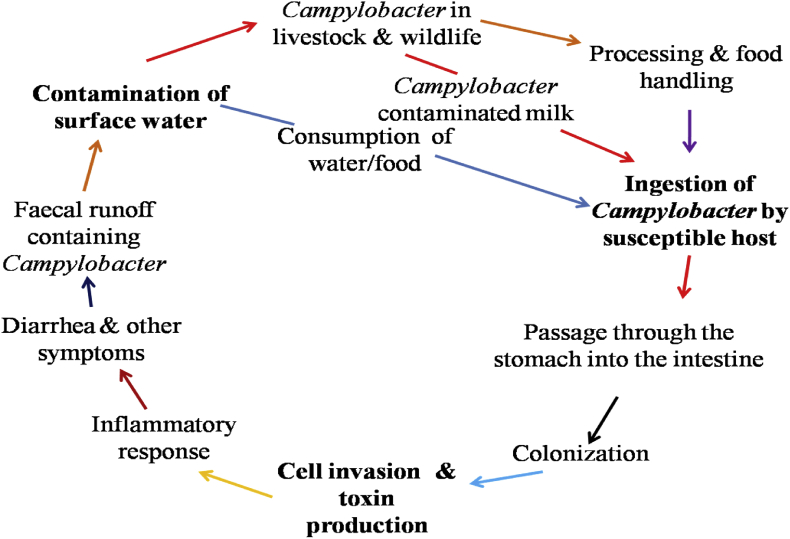

Campylobacters are types of bacteria that majorly cause infections in the gastrointestinal tract. Campylobacter infections may be acquired through different means including consumption of unpasteurized milk, non-chlorinated/contaminated surface water and consumption of undercooked poultry or red meat. Campylobacter infections can also be acquired through direct contact with infected pets within the family environment (Shane, 2000). The clinical manifestations of Campylobacter infections are oftentimes impossible to differentiate from infections caused by Shigella and Salmonella (Hansson et al., 2018). Campylobacter mechanisms of survival and infection is poorly understood but when colonized the ileum, jejunum and colon, it sometimes causes infection with or without symptoms. Fig. 1 is a schematic representation of the transmission cycle involve in Campylobacter infection.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the transmission cycle involve in Campylobacter infections.

4.1. Classification of Campylobacter infections

Campylobacter infection is a bacterial infection that commonly causes human gastroenteritis but infection can also occur outside the intestines. Campylobacter infections are classified into two categories namely; (i): Gastrointestinal infection (GI) and (ii): Extragastrointestinal infection.

4.1.1. Gastrointestinal infections

Gastrointestinal infection (GI) is the inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract involving both the small intestine and stomach (Walsh et al., 2011). GI is generally characterized by diarrhea (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Campylobacter is 1 of the 4 key global bacterial cause of gastrointestinal infections (WHO, 2018). It's also the major and regular cause of traveller's diarrhea (Bullman et al., 2011) and children diarrhea (Liu et al., 2016). Besides diarrhea, other gastrointestinal infections associated with different Campylobacter species are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Campylobacter species associated with human gastroenteritis.

| Campylobacter species | Gastrointestinal infections |

|---|---|

| C. coli | Gastroenteritis and acute cholecystitis |

| C. concisus | Gastroenteritis and Barrett esophagitis |

| C. curvus | Liver abscess, Barrett esophagitis and gastroenteritis |

| C. fetus | Gastroenteritis |

| C. helveticus | Diarrhea |

| C. hominis | Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease |

| C. hyointestinalis | Diarrhea and gastroenteritis |

| C. jejuni | Acute cholecystitis and celiac disease |

| C. insulaenigrae | Abdominal pain, diarrhea and gastroenteritis |

| C. lari | Gastroenteritis and septicaemia |

| C. mucosalis | Gastroenteritis |

| C. rectus | Ulcerative colitis, gastroenteritis and Crohn's disease |

| C. showae | Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease |

| C. sputorum | Gastroenteritis |

| C. upsaliensis | Gastroenteritis |

| C. ureolyticus | Gastroenteritis, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis |

4.1.2. Extragastrointestinal infections

Extragastrointestinal infections (EI) are infections outside the intestines but symptoms are associated with a problem within the intestine (Hernandez and Green, 2006). Extragastrointestinal infections reported to be associated with Campylobacter infections includes reactive arthritis, GBS (Kuwabara and Yuki, 2013), bacteremia, septicaemia (Man, 2011), septic arthritis, endocarditis, neonatal sepsis, osteomyelitis, and meningitis (Allos, 2001). In small number of cases, other extragastrointestinal post-infections associated with Campylobacter infections include severe neurological dysfunction, neurological disorders and a polio-like form of paralysis (WHO, 2018). Some Campylobacter species associated with extragastrointestinal infections are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Campylobacter species associated with human extragastrointestinal infections.

| Campylobacter species | Extragastrointestinal infections |

|---|---|

| C. coli | Bacteremia, sepsis, meningitis and spontaneous abortion |

| C. concisus | Brain abscess, reactive arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis |

| C. curvus | Bronchial abscess and bacteremia |

| C. fetus | Meningitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, brain abscess, cellulitis, septic abortion and bacteremia, |

| C. hominis | Bacteremia |

| C. hyointestinalis | Fatal septicaemia |

| C. jejuni | Sequelae such as bacteremia, urinary tract infection, GBS, reactive arthritis, MFS, sepsis, meningitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| C. insulaenigrae | Septicemia |

| C. lari | Bacteremia |

| C. rectus | Necrotizing soft tissue infection and empyema thoracis |

| C. showae | Intraorbital abscess |

| C. sputorum | Axillary abscess and bacteremia |

| C. ureolyticus | Reactive arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis |

| C. upsaliensis | Breast abscess, bacteremia and spontaneous abortion |

4.2. Isolation and diognosis of Campylobacter infection

Isolation of Campylobacter species relied on culture-based methods which have helped to strongly ascertain its part in human infections (Moore et al., 2005). Campylobacter isolation involves a medium that uses antibiotics as selective agents. These antibiotics used differs from a single antibiotic including cefoperazone or cefazolin in modified CDA medium to a “cocktail” of polymixin B, trimethroprin and vancomycin found in Skirrow's medium (Thomas, 2005). Campylobacter sensitivity to oxidizing radicals and O2 has led to the development of a number of selective media and selective agents for its isolation (Silva et al., 2011). Before the development of these culture media for Campylobacter isolation and detection, non-selective medium was previously used but the medium was less proper for isolation of campylobacters from environmental and animal samples. Owing to this problem, Bolton and Robertson in 1977 developed a selective Preston medium suitable for Campylobacter isolation from environmental and food samples (Bolton and Robertson, 1982). Several other selective broths and media latter developed for Campylobacter isolation includes Bolton broth, Preston broth and Campylobacter enrichment broth (Baylis et al., 2000), modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCDA) (Wei et al., 2018), CampyFood agar (CFA) and broth, RAPID’Campylobacter agar (Seliwiorstow et al., 2014), Campylobacter agar base (CAB) and Campylobacter Cefex agar (Kashappanavar et al., 2018). Campylobacter species are microaerobic, fastidious bacteria capable of growing in a temperature between 37 °C and 42 °C (Davis and DiRita, 2017). Despite Campylobacter sensitivity to high temperature and low oxygen concentration, the actual procedures used by clinical laboratories in its isolation from human faecal specimens may vary in different countries (Hurd et al., 2012). However, laboratory diagnosis of campylobacteriosis is usually carried out by culture-base technique or by rapid detection of Campylobacter antigen (Enzyme Immunoassay) in stool samples, body tissue or fluids of infected person to identify the genetic materials of this bacterial strain that shows similar symptoms with other bacteria pathogens (Adedayo and Kirkpatrick, 2008; do Nascimento et al., 2016).

Other method use for Campylobacter identification includes growth morphology, biochemical tests (Prouzet-Mauléon et al., 2006) and some of these identification methods used are not unreliable (On, 2001). However, other molecular techniques have been designed as alternative and better diagnostic methods for identification (Kuijper et al., 2003). In 1992, application of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was first used for specific detection of C. coli and C. jejuni (Oyofo et al., 1992), and PCR is widely used in the detection and identification of this bacterial to species level (Shawky et al., 2015). In addition to PCR techniques, other molecular methods used for identification or detection of Campylobacter species include random amplified polymorphic DNA (da Silva et al., 2016), whole-genome sequencing (Hasman et al., 2014; Schürch et al., 2018), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) (Patel, 2019; Singhal et al., 2015). Some of the challenges involved in Campylobacter isolation and identification includes difficult procedures for isolation and identification (Llarena et al., 2017), suboptimal storage and loss of isolates during extensive freeze-thaw cycles which has raised concerns to the scientific community (Maziero and de Oliveira, 2010). Likewise, the presence of the “protective guard” in a community of multispecies biofilm could hide a wide range of emerging pathogenic Campylobacter species which can successfully “escape” adverse environments and regain its ability to cause infection when found in optimal conditions may lead to wrong results in the diagnosis process (Wood et al., 2013). Another serious challenge for public health concern in campylobacters identification and diagnosis is its ability to remain viable but nonculturable but retain its physiology and virulence ability (Ayrapetyan and Oliver, 2016; Li et al., 2014). Lasstly, the laboratory diagnosis of Campylobacter infections caused by other pathogenic Campylobacter species except C. coli and C. jejuni is complex due to the challenging growth and identification processes of the several subsets of Campylobacter species (Magana et al., 2017).

4.3. Transmission routes of Campylobacter infection

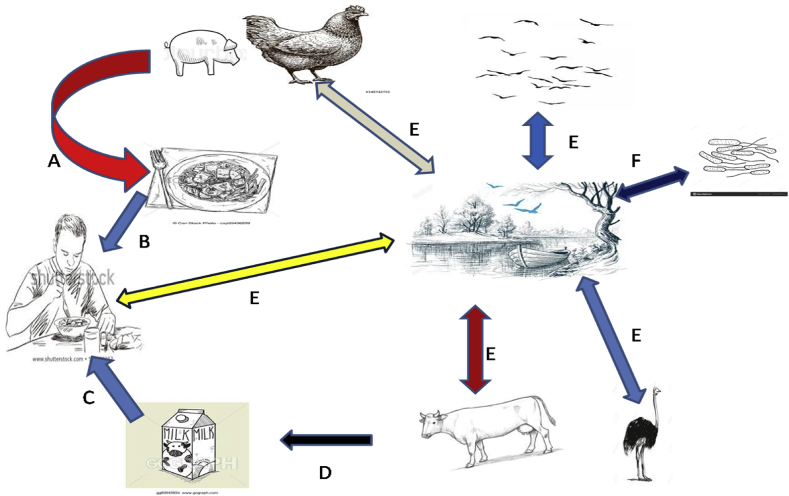

Campylobacter species majorly colonized the intestine of poultry, European blackbirds, cattle, sheep, ostriches, cats, dogs and pigs (Dearlove et al., 2016). These bacteria are shed in the faeces of these animals into the environment (Goni et al., 2017). Campylobacter can also spread to person by direct contact to animals such as pets (ESR, 2016; Westermarck, 2016), with dog owners at high risk of Campylobacter infection (Gras et al., 2013). Beside pets, other domestic animals such as cattle are also regularly colonized by Campylobacter species and persons working with these animals are also at high risk of Campylobacter infection (Hansson et al., 2018). Other sets of people at high risk of campylobacteriosis include farms and abattoirs workers who sometimes do not practice hand-washing and food safety habits (Aung et al., 2015). However, identification and understanding the transmission routes of Campylobacter infections is crucial for its prevention and control (Newell et al., 2017). The common and major route/pathways of campylobacteriosis includes through faecal-oral routes (Rosner et al., 2017), through consumption of contaminated undercooked meats or through consumption of contaminated food/water (Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk et al., 2013). Fig. 2 is a schematic illustration of overview of the transmission routes of Campylobacter infection.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the transmission routes of Campylobacter infection.

4.3.1. Milk as a route of Campylobacter transmission

Worldwide, there is a rise in the consumption of unpasteurized milk as a result of its health benefits compared to pasteurized milk (Sugrue et al., 2019). Despites the health benefits in the consumption of unpasteurized milk, there is a great concern to the health risk its pose to human (Baars et al., 2019). Milk is a white liquid and a nutrient-rich food produced in the mammary glands of mammals. It's a source of protein, dietary fats and minerals (calcium and magnesium) for growth particularly in children (O'Callaghan et al., 2019). Milk is consumed either unpasteurized or pasteurized and mammals that produced milk for human consumption includes sheep, buffalo, goats, cows, yak and camel and the highest proportions of commercially produced milks are from cows (Quigley et al., 2013). Milk is considered germ-free when secreted in the alveoli of the udder (Vacheyrou et al., 2011). Fresh milk drawn from animals naturally possess a short lived antibacterial system that display ‘germicidal’ or ‘bacteriostatic’ properties but bacterial growth is inevitable after sometimes except it undergoes heat treatment or freezing (Sarkar, 2016). Milk is a good substrate for bacteria growth (Hudson et al., 2014) and it's reported to be among the major transmission routes for Campylobacter to humans (El-Zamkan and Hameed, 2016). Milk is natural foods that has no protection against external contamination and can easily be contaminated when separated from it source (Neeta et al., 2014). Milk contamination generally occurs from environmental sources such as water, grass, milking equipments, feed, air, teat apex, soil and other sources (Coorevits et al., 2008). It's believed that the occurrence of Campylobacter species in raw milk samples is from faecal contamination (Oliver et al., 2005). Campylobacter species have been detected in cow milk (Del Collo et al., 2017 et al., 2017), and different Campylobacter species that have been detected in milk samples from different mammals including C. Jejuni detected in buffalo and cow milk (Modi et al., 2015) and C. coli identified in cow milk (Rahimi et al., 2013). Campylobacter species have also been detected in bulk tank milk where these milks are stored (Bianchini et al., 2014), and Campylobacter species reported to have been detected from milk samples from the bulk tank include C. lari, C. jejuni and C. coli (Del Collo et al., 2017). Globally, several cases of illness and deaths have been reported to occur via consumption of contaminated raw milk and its products (Hati et al., 2018), and in many countries, milk-borne pathogens are of public health concern (Amenu et al., 2019).

4.3.2. Meat as a route of Camplobacter transmission

Worldwide, consumption of meats is steadily increasing and meats are sometimes contaminated with microorganisms but bacteria contaminations may sometimes occur from animal microbiota, equipment surfaces and water (Vihavainen et al., 2007). The bacteria from animal's microbiota that majorly contaminate meats include pathogenic Salmonella and Campylobacter species and these two bacteria species are majorly responsible for human gastroenteritis as a result of consumption of contaminated undercooked meat (Rouger et al., 2017). Campylobacter contamination remains the major cause of bacterial food-borne infection and the major reservoir of these bacteria species are poultry (Wieczorek et al., 2015). Infections caused by poultry consumption represents about 50–70% of the global Campylobacter infections cases (Seliwiorstow et al., 2015), and poultry is define as meats from chicken, turkey, duck and goose (Szosland-Fałtyn et al., 2018). Beside poultry, Campylobacter species have also been detected in other meat typss such as pork and beef (Hussain et al., 2007; Korsak et al., 2015), mutton (Nisar et al., 2018) and in camel, lamb and chevon (Rahimi et al., 2010). Campylobacter species that have been isolated and detected in meat samples include C. coli and C. jejuni identified in poultry meat (Mezher et al., 2016), C. coli, C. lari, C. jejuni and C. fetus detected in mutton samples (Sharma et al., 2016), and C. jejuni and C. coli detected in pork, beef and lamb (Wong et al., 2007). Isolation and detection of these bacteria species from meats samples position them as one of the major transmission route (Duarte et al., 2014).

4.3.3. Water as a route of Campylobacter transmission

Worldwide, access to safe drinking water is one of the targets goals, but report from regular analysis of water samples have showed that unsafe drinking water remain the number eight leading risk factor for human disease (Khan and Bakar, 2019). Studies have also showed that improved water sources including public taps/standpipes, protected dug wells, boreholes and protected springs are not automatically free of faecal contamination (Bain et al., 2014). In high income countries, water is sometimes contaminated through faulty pumps and pipes while in low income countries, majority of the people rely mostly on streams, lakes and other surface water sources for food preparation, washing clothes, drinking and these water are usually contaminated by human and animal faeces exacerbating the possibility of waterborne infections (Thompson and Monis, 2012). Though, some environmental sources used for recreational purposes are often overlooked as a route of disease transmission (Henry et al., 2015). Water is an important route of Campylobacter transmission to humans resulting to waterborne infections (Mossong et al., 2016) and waterborne infections can involve several persons (Pitkänen, 2013). Besides, Campylobacter infection via consumption of contaminated food/tap water (Irena et al., 2008), other water sources including dug well water have been reported to be implicated in Campylobacter outbreaks (Guzman-Herrador et al., 2015). Some of the reported pathogenic Campylobacter species detected in water samples from beach and river include C. coli, C. jejuni and C. lari (Khan et al., 2013). Other water sources where these bacteria have also been isolated includes ponds, streams, lakes (Sails et al., 2002), children's paddling pool (Gölz et al., 2018), groundwater and seawater (Kemp et al., 2005).

4.4. Epidemiological information of Campylobacter outbreaks

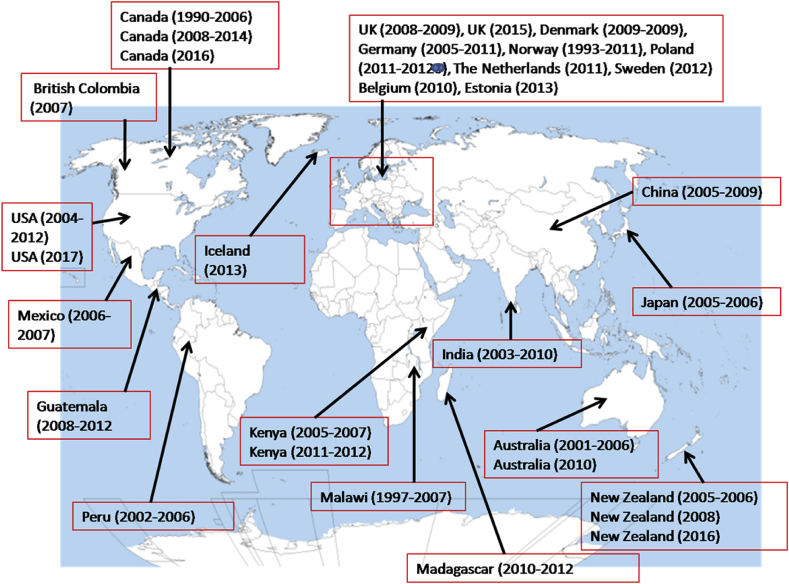

The reports in the incidences of Campylobacter outbreaks differs among countries and the true nature of the global occurrence rate is largely unknown (WHO, 2013). The reasons for lack of true incidences rate of Campylobacter outbreaks includes underreporting of Campylobacter infection cases, differences in the reporting systems, difficulties with diagnosis and differences in surveillance in case of outbreaks (Hansson et al., 2018). Campylobacter outbreaks are usually either from waterborne or foodborne infection involving several persons (Frost et al., 2002), and majority of Campylobacter outbreaks are usually from animal origin (Wilson et al., 2008). Although, in low income countries, Campylobacter outbreaks are majorly from environmental sources such as streams and river where many people depend on these water bodies as their major drinking water source (Clark et al., 2003; Platts-Mills and Kosek, 2014). Beside involvement of water sources in human infection in low income countries, water sources have also been reported to be implicated in Campylobacter outbreaks in high income countries such as Norway (Jakopanec et al., 2008), New Zealand (Bartholomew et al., 2014), Canada (Clark et al., 2003), Finland (Kuusi et al., 2004) and Denmark (Kuhn et al., 2017). Campylobacter milk borne infection and outbreaks have also been reported in several high and low income countries (García-Sánchez et al., 2017). Some of the countries with records of campylobacteriosis outbreaks including the Netherlands (Bouwknegt et al., 2013), Israel (Weinberger et al., 2013), China (Chen et al., 2011), Japan (Kubota et al., 2011), India (Mukherjee et al., 2013), Sweden (Lahti et al., 2017), Mexico (Zaidi et al., 2012) and the United States (Geissler et al., 2017; Gilliss et al., 2013). Also, other nations where there have been records of Campylobacter outbreaks includes Canada (Keegan et al., 2009; Ravel et al., 2016), British Columbia (Stuart et al., 2010), Australia (Kaakoush et al., 2015; Unicomb et al., 2009), the United Kingdom (Tam et al., 2012), Belgium (Braeye et al., 2015), Denmark (Nielsen et al., 2013), Germany (Hauri et al., 2013), Norway (Steens et al., 2014), Poland (Sadkowska-Todys and Kucharczyk, 2014), New Zealand (Berger, 2012; Sears et al., 2011), Madagascar (Randremanana et al., 2014), Malawi (Mason et al., 2013), Kenya (O'Reilly et al., 2012; Swierczewski et al., 2013), Iceland and Estonia (Skarp et al., 2016), Guatemala (Benoit et al., 2014) and Peru (Lee et al., 2013). Fig. 3 is a map showing records of some reported cases of Campylobacter outbreaks in some countries of the world.

Fig. 3.

List of some countries with records of campylobacteriosis outbreaks.

4.5. Prevention and treatment of Campylobacter infections

Prevention of Campylobacter infections can be directly applied to humans by different ways including sewage sanitary conditions, provision of portable water, vaccine usage, public awareness concerning the significance of pasteurization of milk, proper cooking of food from animal origins and the use of therapeutics in case of infections (Hansson et al., 2018). Prevention of Campylobacter infections can also be directed on animals by phage treatment (Borie et al., 2014), probiotics, prebiotics, and by improved biosecurity such as the provision of good water quality at farm level and also by monitoring the regular use of antibiotics in animal husbandry. Another vital preventive measure that will help lower the level of these bacteria is the withholding of feed from poultry for about 12 h before slaughter (Hansson et al., 2018). Campylobacter infections are sometimes self-limiting but in most cases fluid and electrolyte replacement are major supportive measures for the treatment of this infection (Guarino et al., 2014). Beside fluid and electrolyte replacement, antibiotics are used when symptoms pesist and antibiotics treatments are most effective when started within three days after onset of illness. Nonetheless, antibiotics are regularly used in Campylobacter infected patients with diarrhea, high fever or patients with other severe illness like weakened immune systems, AIDS, thalassemia, and hypogammaglobulinemia (CDC, 2016). Antibiotics drugs of choice for the treatment of campylobacteriosis includes fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, macrolides, betalactams (Bolton, 2015) and erythromycin (Bardon et al., 2009). Other useful alternative antibiotics drugs of choice include ciprofloxacin, vancomycin (Bruzzese et al., 2018) and quinolones (Gilber and Moellering, 2007).

4.6. Antibiotic resistance

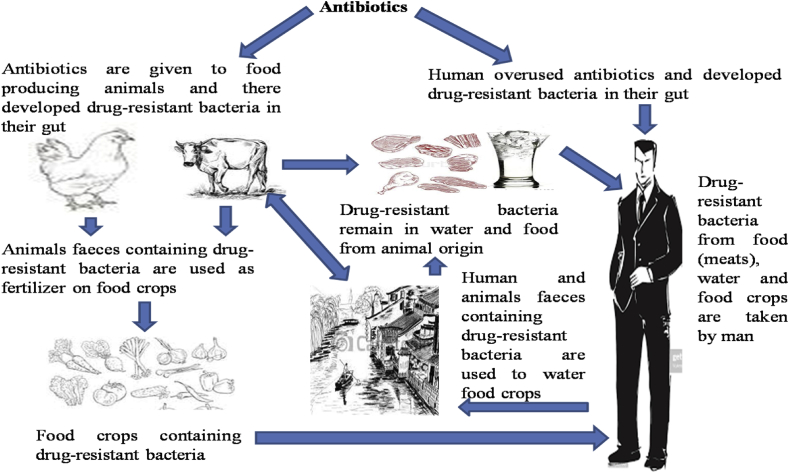

Antibiotics use for the treatment of campylobacteriosis is significant for patients with prolonged or severe infections (Reddy and Zishiri, 2017). Campylobacter resistance to vital antibiotics used in the treatments of Campylobacter infections is an emerging global burden and Campylobacter resistance to drugs of choice may limit the treatment options (De Vries et al., 2018). The global spread of antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter strains is a contineous process due to the regular use of antibiotics in animal husbandary and this is a problem of public health concern (Silva et al., 2011). Other problems that add to the spread of Campylobacter resistance includes inability to completely remove these antibiotic-resistant bacteria during wastewater treatment process, inproper dumping of humans and animals waste into waterbodies and inappropriate preparation of food from animal origin (Founou et al., 2016). Antibiotic resistant bacteria is a global problem assocaited with increased healthcare cost, prolonged infections with a greater risk of hospitalization and high mortality risk and rate (Founou et al., 2017). Molecular detection of antibiotic resistance genes in Campylobacter species have helped in determining the resistance genes in Campylobacter species from animals and environmental origin (Moyane et al., 2013). Molecular detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in Campylobacter originating from foods and water samples is a major public health concern of global importance (Elhadidy et al., 2018). Some of the resistance genes detected in Campylobacter species includes quinolone resistance-genes (gyrA, gyrB and parC) (Piddock et al., 2003), FQ-resistant (parE) (Luangtongkum et al., 2009), β-lactamase (blaOXA-61 and blaOX-184), tetracycline resistance genes (tetA, tetB, tetM, tetO and tetS) (Reddy and Zishri, 2017), aminoglycoside resistance genes (aphA and aadE) (García-Sánchez et al., 2019) and erythromycin resistance gene (ermB) (Wang et al., 2014). Antibiotics resistance genes in Campylobacter are either acquired by spontaneous mutations or through horizontal gene transfer via transduction, conjugation and transformation (Kumar et al., 2016). Other resistance mechanisms developed by Campylobacter against antimicrobials include genetic mutation (Reddy and Zishiri, 2017), point mutation (Luangtongkum et al., 2009), decreased in membrane permeability due to MOMP (García-Sánchez et al., 2019) and rRNA methylases (Wang et al., 2014). Resistance-nodulation-cell division efflux system, modification of ribosomal target sites and weakening of the interaction of the macrocyclic ring and the tunnel wall of the ribosome are also essential resistance mechanism developed in Campylobacter (Wei, and Kang, 2018). Fig. 4 is a schematic illustration of the patterns implicated in the spread of antibiotic resistance genes.

Fig. 4.

A schematic process involved in the spread of antibiotic resistance bacteria.

4.7. Control of antibiotic use

The emergence of antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter strains has rise markedly in both developing and developed countries suggesting the use of antibiotics in animal husbandry as the source of the accelerating trend (Wieczorek and Osek, 2013). Several countries have policy in the control of antibiotics use in animal production (Maron et al., 2013). However, multiples countries do not have policy in the control of antibiotics use for animal production. In addition, grain-based feeds and water are mostly supplemented with antibiotics and other drugs for animal production (Sapkota et al., 2007). In some countries that practise indiscriminate use of antimicrobial in animal production, new regulatory policy should be place on the use of antibiotic in animal husbandry for non-therapeutic reasons such as promoting weight gains of birds or improving feed efficiency (Rahman et al., 2018). Owing to the increase in antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter strains, vaccine development is important and vaccination of birds against Campylobacter could help eradicate Campylobacter from birds and reduce the rate of incidence of human infections (Avci, 2016). Vaccine would also help to reduce high cost of post-harvest treatments (Johnson et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the cost of Campylobacter infections treatment to public health systems is high thus the main motivation towards developing a Campylobacter vaccine would be to reduce the high costs of treatment associated with campylobacteriosis, enhance food safety and reduce potential human health risks (Lund and Jensen, 2016). Presently, there are no vaccines approved by any global governing authority to prevent Campylobacter infections (Riddle and Guerry, 2016). Vaccine approaches against Campylobacter infections are restricted by lacking in comprehension of its association with post-infectious syndromes, antigenic diversity, protective epitopes and its pathogenesis (Riddle and Guerry, 2016).

5. Conclusions

Worldwide, outbreaks of campylobacteriosis have been increasing and the major routes of transmission of these bacteria to human is generally believed to be through consumption of contaminated foods. The development of rapid Kits for Campylobacter detection and quantification in foods from animal origin will be essential for the prevention of Campylobacter infections. Campylobacter infections are majorly treated with antibiotics and the actions of these antibiotics have been compromised and this call for the development of new vaccines that will help to control the regular use of antibiotics in animal husbandry. In addition, regular domestic hygiene will also help to prevent Campylobacter infections. The production of new and effective antibiotic for better treatment of campylobacteriosis will as well help in the reduction of antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter strain and the spread of antibiotics resistant genes.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the South African Medical Research Council.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abuoun M., Manning G., Cawthraw S.A., Ridley A., Ahmed I.H., Wassenaar T.M., Newell D.G. Cytolethal distending toxin (CDT)-negative Campylobacter jejuni strains and anti-CDT neutralizing antibodies are induced during human infection but not during colonization in chickens. Infect. Immun. 2005;73(5):3053–3062. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3053-3062.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adedayo O., Kirkpatrick B.D. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on presentation, diagnosis, and management. Clin. Rev. 2008;7:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Acke E. Campylobacteriosis in dogs and cats: a review. N. Z. Vet. J. 2018;66(5):221–228. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2018.1475268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allos B.M. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32(8):1201–1206. doi: 10.1086/319760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allos B.M., Blaser M.J. seventh ed. (c) Churchill Livingston, New York; USA: 2009. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- Allos B.M. 2011. Microbiology, Pathogenesis, and Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. [Google Scholar]

- Allos B.M., Calderwood S.B., Baron E.L. UpToDate; Waltham, MA: 2013. Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Campylobacter Infection. [Google Scholar]

- Alnimr A.M. A case of bacteremia caused by Campylobacter fetus: an unusual presentation in an infant. Infect. Drug Resist. 2014;7:37–40. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S58645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amenu K., Wieland B., Szonyi B., Grace D. Milk handling practices and consumption behavior among Borana pastoralists in southern Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2019;38(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s41043-019-0163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura M., Samosornsuk W., Hinenoya A., Misawa N., Nishimura K., Matsuhisa A., Yamasaki S. Development of a cytolethal distending toxin (cdt) gene-based species-specific multiplex PCR assay for the detection and identification of Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter fetus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008;52:260–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung W.W., Saleha A.A., Zunita Z., Murugaiyah M., Aliyu A.B., Goni D.M., Mohamed A.M. Occurrence of Campylobacter in dairy and beef cattle and their farm environment in Malaysia. Pakistan Vet. J. 2015;35(4):470–473. [Google Scholar]

- Avci F.Y. A chicken vaccine to protect humans from diarrheal disease. Glycobiology. 2016;26:1137–1139. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cww097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrapetyan M., Oliver J.D. The viable but non-culturable state and its relevance in food safety. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016;8:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Baars T., Berge C., Garssen J., Verster J. The impact of raw milk consumption on gastrointestinal bowel and skin complaints in immune depressed adults. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29:226. [Google Scholar]

- Backert S., Boehm M., Wessler S., Tegtmeyer N. Transmigration route of Campylobacter jejuni across polarized intestinal epithelial cells: paracellular, transcellular or both? Cell Commun. Signal. 2013;11(1):72. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain R., Cronk R., Wright J., Yang H., Slaymaker T., Bartram J. Fecal contamination of drinking-water in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(5):1001644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardon J., Kolar M., Cekanova L., Hejnar P., Koukalova D. Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni and its resistance to antibiotics in poultry in the Czech Republic. Zoonoses Pub. Health. 2009;56(3):111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew N., Brunton C., Mitchell P., Williamson J., Gilpin B. A waterborne outbreak of campylobacteriosis in the South Island of New Zealand due to a failure to implement a multi-barrier approach. J. Water Health. 2014;12(3):555–563. doi: 10.2166/wh.2014.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis C.L., MacPhee S., Martin K.W., Humphrey T.J., Betts R.P. Comparison of three enrichment media for the isolation of Campylobacter spp. from foods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;89(5):884–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier R.C., Harvey R.B., Hernandez C.A., Hume M.E., Andrews K., Droleskey R.E., Davidson M.K., Bodeis-Jones S., Young S., Duke S.E., Anderson R.C. Interactions of organic acids with Campylobacter coli from swine. PLoS One. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit S.R., Lopez B., Arvelo W., Henao O., Parsons M.B., Reyes L., Moir J.C., Lindblade K. Burden of laboratory-confirmed Campylobacter infections in Guatemala 2008–2012: results from a facility-based surveillance system. J. Epidemiol. Global Health. 2014;4(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S.A. 2012. Infectious Diseases of New Zealand. Gideon E-Books 413. [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar S., Kapadnis B. Virulence factors of Campylobacter. Internet J. Microbiol. 2006;3(2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini V., Borella L., Benedetti V., Parisi A., Miccolupo A., Santoro E., Recordati C., Luini M. Prevalence in bulk tank milk and epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni in dairy herds in Northern Italy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80(6):1832–1837. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03784-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham-Ramos L.K., Hendrixson D.R. Characterization of two putative cytochrome peroxidases of Campylobacter jejuni involved in promoting commensal colonization of poultry. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:1105–1114. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01430-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D., Hannon S.H., Townsend G.G.H., Potter A., Allan B.J. Genes coding for virulence determinants of Campylobacter jejuni in human clinical and cattle isolates from Alberta, Canada, and their potential role in colonization of poultry. Int. Microbiol. 2011;14(1):25–32. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser M.J. Infections due to Campylobacter and related species. Principles of Harrison's Internal Med. 2008:965–968. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton F.J., Robertson L. A selective medium for isolating Campylobacter jejuni/coli. J. Clin. Pathol. 1982;35(4):462–467. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton D.J. Campylobacter virulence and survival factors. Food Microbiol. 2015;48:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borie C., Robeson J., Galarce N. Lytic bacteriophages in Veterinary Medicine: a therapeutic option against bacterial pathogens? Arch. Med. Vet. 2014;46(2) [Google Scholar]

- Bourke B., Chan V.L., Sherman P. Campylobacter upsaliensis: waiting in the wings. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998;11:440. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwknegt M., van Pelt W., Havelaar A.H. Scoping the impact of changes in population age-structure on the future burden of foodborne disease in The Netherlands, 2020–2060. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10(7):2888–2896. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10072888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braeye T., De Schrijver K., Wollants E., Van Ranst M., Verhaegen J. A large community outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with consumption of drinking water contaminated by river water, Belgium, 2010. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015;143(4):711–719. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzese E., Giannattasio A., Guarino A. Antibiotic treatment of acute gastroenteritis in children. F1000 Res. 2018;7(193) doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12328.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullman S., Corcoran D., O’Leary J., Lucey B., Byrne D., Sleator R.D. Campylobacter ureolyticus: an emerging gastrointestinal pathogen?. Campylobacter ureolyticus: an emerging gastrointestinal pathogen? FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011;61(2):228–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham P.M., Hendrixson D.R. Campylobacter jejuni: collective components promoting a successful enteric lifestyle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;11:018–0037. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C.D., Taboada E., Nash J.H., Lanthier P., Kelly J., Lau P.C., Verhulp R., Mykytczuk O., Sy J., Findlay W.A., Amoako K. Genome-wide expression analyses of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 reveals coordinate regulation of motility and virulence by flhA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20327–20338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A.F.D., Silva D.M.D., Azevedo S.S., Piatti R.M., Genovez M.E., Scarcelli E. Detection of CDT toxin genes in Campylobacter spp. strains isolated from broiler carcasses and vegetables in São Paulo, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013;44(3):693–699. doi: 10.1590/s1517-83822013000300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casabonne C., Gonzalez A., Aquili V., Subils T., Balague C. Prevalence of seven virulence genes of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from patients with diarrhea in Rosario, Argentina. Int. J. Infect. 2016;3(4):1–6. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil R.L.F., Goldman L., Schafer A.I. Vol. 24. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. Goldman's cecil medicine, expert consult premium edition--enhanced online features and print. (Goldman's Cecil Medicine). [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases; 2014. Campylobacter. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . 2016. Infectious Disease Campylobacter Clinical Foodborne Illnesses.WWW.cdc.gov [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Miller J.F. Campylobacter jejuni colonization of mice with limited enteric flora. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:5261–5271. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01094-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Sun X.T., Zeng Z., Yu Y.Y. Campylobacter enteritis in adult patients with acute diarrhea from 2005 to 2009 in Beijing, China. Chin. Med. J. 2011;124(10):1508–1512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.G., Price L., Ahmed R., Woodward D.L., Melito P.L., Rodgers F.G., Jamieson F., Ciebin B., Li A., Ellis A. Characterization of waterborne outbreak–associated Campylobacter jejuni, Walkerton, Ontario. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9(10):1232–1241. doi: 10.3201/eid0910.020584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connerton I.F., Connerton P.L. third ed. Foodborne Diseases; 2017. Campylobacter Foodborne Disease; pp. 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Coorevits A., De Jonghe V., Vandroemme J., Reekmans R., Heyrman J., Messens W., De Vos P., Heyndrickx M. Comparative analysis of the diversity of aerobic spore-forming bacteria in raw milk from organic and conventional dairy farms. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;31:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier B.A., Hale D.C., Couturier M.R. Association of Campylobacter upsaliensis with persistent bloody diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;1807 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01807-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crim S.M., Griffin P.M., Tauxe R., Marder E.P., Gilliss D., Cronquist A.B., Cartter M., Tobin-D’Angelo M. Centers for disease control and prevention. Preliminary incidence and trends of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2006–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015;64:495–499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damborg P., Guardabassi L., Pedersen K., Kokotovic B. Comparative analysis of human and canine Campylobacter upsaliensis isolates by amplified fragment length polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46(4):1504–1506. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00079-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva D.T., Tejada T.S., Blum-Menezes D., Dias P.A., Timm C.D. Campylobacter species isolated from poultry and humans, and their analysis using PFGE in southern Brazil. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016;217:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasti J.I., Tareen A.M., Lugert R., Zautner A.E., Gross B.U. Campylobacter jejuni; A brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease mediated mechanisms. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010;300:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S., Niwa H., Itoh K. Prevalence of 11 pathogenic genes of Campylobacter jejuni by PCR in strains isolated from humans, poultry meat and broiler and bovine faeces. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;52(4):345–348. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L., DiRita V. Growth and laboratory maintenance of Campylobacter jejuni. Current Protoc. Microbiol. 2017;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc08a01s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearlove B.L., Cody A.J., Pascoe B., Méric G., Wilson D.J., Sheppard S.K. Rapid host switching in generalist Campylobacter strains erodes the signal for tracing human infections. ISME J. 2016;10:721–729. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne L., On S.L., De Brandt E., Vandamme P. Novel Campylobacter lari-like bacteria from humans and molluscs: description of Campylobacter peloridis sp. nov., Campylobacter lari subsp. concheus subsp. nov. and Campylobacter lari subsp. lari subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009;59(5):1126–1132. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne L., Broman T., Bergström S., Olsen B., On S.L., Vandamme P. Campylobacter volucris species nov., isolated from black-headed gulls (Larus ridibundus) Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010;60(8):1870–1875. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.013748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Collo L.P., Karns J.S., Biswas D., Lombard J.E., Haley B.J., Kristensen R.C., Kopral C.A., Fossler C.P., Van Kessel J.A.S. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and molecular characterization of Campylobacter spp. in bulk tank milk and milk filters from US dairies. J. Dairy Sci. 2017;100(5):3470–3479. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries S.P., Vurayai M., Holmes M., Gupta S., Bateman M., Goldfarb D., Maskell D.J., Matsheka M.I., Grant A.J. Phylogenetic analyses and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Campylobacter spp. from diarrhoea patients and chickens in Botswana. PLoS One. 2018;13(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle K.E., Van Den Braak N., Colles F.M., Price L.J., Woodward D.L., Rodgers F.G., Endtz H.P., Van Belkum A., Maiden M.C.J. Sequence typing confirms that Campylobacter jejuni strains associated with Guillain-Barre and Miller-Fisher syndromes are of diverse genetic lineage, serotype, and flagella type. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39(9):3346–3349. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3346-3349.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues A.R., Pires S.M., Halasa T., Hald T. Source attribution of human campylobacteriosis using a meta-analysis of case-control studies of sporadic infections. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012;140:970–981. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811002676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento V.H., da Silva Q.J., Lima I.F.N., Rodrigues T.S., Havt A., Rey L.C., Mota R.M.S., Soares A.M., Singhal M., Weigl B., Guerrant R. Combination of different methods for detection of Campylobacter spp. in young children with moderate to severe diarrhea. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2016;128:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenthen J., Yuki N., Meulstee J., Maathuis E.M., van Doorn P.A., Visser G.H., Blok J.H., Jacobs B.C. Guillain–Barré syndrome subtypes related to Campylobacter infection. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2011;82(3):300–305. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.226639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte A., Santos A., Manageiro V., Martins A., Fraqueza M.J., Caniça M., Domingues F.C., Oleastro M. Human, food and animal Campylobacter spp. isolated in Portugal: high genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance rates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2014;44(4):306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duim B., Wagenaar J.A., Dijkstra J.R., Goris J., Endtz H.P., Vandamme P.A. Identification of distinct Campylobacter lari genogroups by amplified fragment length polymorphism and protein electrophoretic profiles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70(1):18–24. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.18-24.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gendy A.M., Wasfy M.O., Mansour A.M., Oyofo B., Yousry M.M., Klena J.D. Heterogeneity of Campylobacter species isolated from serial stool specimens of Egyptian children using pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Afri. J. Lab. Med. 2013;2(1) doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v2i1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadidy M., Miller W., Arguello H., Álvarez-Ordóñez A., Duarte A., Dierick K., Botteldoorn N. Genetic basis and clonal population structure of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from broiler carcasses in Belgium. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1014. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Zamkan M.A., Hameed K.G.A. Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in raw milk and some dairy products. Vet. World. 2016;9(10):1147–1151. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2016.1147-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps S.V., Harvey R.B., Hume M.E., Phillips T.D., Anderson R.C., Nisbet D.J. Foodborne Campylobacter: infections, metabolism, pathogenesis and reservoirs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10(12):6292–6304. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESR . ISSN; 2016. The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. Notifiable diseases New Zealand: annual report 2015. Porirua, New Zealand; pp. 1179–3058. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and ECDC Scientific Report The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2013. EFSA J. 2015;13:3991. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald C., Nachamkin I. Campylobacter and arcobacter. In: Murray P.R., Baron E.J., Jorgensen J.H., Landry M.L., Pfaller M.A., editors. Manual of Microbiology. ninth ed. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2007. pp. 933–946. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald C., chao Tu Z., Patrick M., Stiles T., Lawson A.J., Santovenia M., Gilbert M.J., Van Bergen M., Joyce K., Pruckler J., Stroika S. Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum subsp. nov., isolated from humans and reptiles. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64(9):2944–2948. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.057778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Founou L.L., Founou R.C., Essack S.Y. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: a developing country-perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frirdich E., Biboy J., Huynh S., Parker C.T., Vollmer W., Gaynor E.C. Morphology heterogeneity within a Campylobacter jejuni helical population: the use of calcofluor white to generate rod-shaped C. jejuni 81-176 clones and the genetic determinants responsible for differences in morphology within 11168 strains. Mol. Microbiol. 2017;104(6):948–971. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost J.A., Gillespie I.A., O’Brien S.J. Public health implications of Campylobacter outbreaks in England and Wales, 1995-1999: epidemiological and microbiological investigations. Epidemiol. Infect. 2002;128(2):111–118. doi: 10.1017/s0950268802006799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Founou R.C., Founou L.L., Essack S.Y. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garenaux A., Jugiau F., Rama F., Jonge R., Denis M., Federighi M., Ritz M. Survival of Campylobacter jejuni strains from different origins under oxidative stress conditions: effect of temperature. Curr. Microbiol. 2008;56:293–297. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S., Heredia N.L. 2013. 11 Campylobacter. Guide to Foodborne Path; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez L., Melero B., Jaime I., Hänninen M.L., Rossi M., Rovira J. Campylobacter jejuni survival in a poultry processing plant environment. Food Microbiol. 2017;65:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez L., Melero B., Jaime I., Rossi M., Ortega I., Rovira J. Biofilm formation, virulence and antimicrobial resistance of different Campylobacter jejuni isolates from a poultry slaughterhouse. Food Microbiol. 2019;83:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor E.C., Wells D.H., MacKichan J.K., Falkow S. The Campylobacter jejuni stringent response controls specific stress survival and virulence-associated phenotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56(1):8–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler A.L., Bustos C.F., Swanson K., Patrick M.E., Fullerton K.E., Bennett C., Barrett K., Mahon B.E. Increasing Campylobacter infections, outbreaks, and antimicrobial resistance in the United States, 2004–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;65(10):1624–1631. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilber D.N., Moellering R.C. 37th ed. 2007. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. Antimicrobial Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliss D., Cronquist A.B., Cartter M., Tobin-D’Angelo M., Blythe D., Smith K., Lathrop S., Zansky S., Cieslak P.R., Dunn J., Holt K.G., Lance S., Crim S.M., Henao O.L., Patrick M., Griffin P.M., Tauxe R.V. Incidence and trends of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food-foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 10 U.S. sites, 1996–2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013;62:283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gölz G., Kittler S., Malakauskas M., Alter T. Survival of Campylobacter in the food chain and the environment. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2018;1–9 [Google Scholar]

- Golden N.J., Acheson D.W. Identification of motility and autoagglutination Campylobacter jejuni mutants by random transposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:1761–1771. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1761-1771.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni M.D., Muhammad J., Goje M., Abatcha M.G., Bitrus A.A., Abbas M.A. Campylobacter in dogs and cats; its detection and public health significance: a Review. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2017;5(6):239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Gras L.M., Smid J.H., Wagenaar J.A., Koene M.G.J., Havelaar A.H., Friesema I.H.M., French N.P., Flemming C., Galson J.D., Graziani C., Busani L. Increased risk for Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli infection of pet origin in dog owners and evidence for genetic association between strains causing infection in humans and their pets. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013;141(12):2526–2535. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A.J., Maskell D.J., Holmes M.A. 2018. Phylogenetic Analyses and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Campylobacter Spp. From Diarrhoea Patients and Chickens in Botswana. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U., Kalita B., Flak-Wancerz A., Jasielska M., Więcek S., Wojcieszyn M., Horowska-Ziaja S., Chlebowczyk W., Woś H. Clinical course of Campylobacter infections in children. Pediatr. Pol. 2013;88(4):329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino A., Ashkenazi S., Gendrel D., Vecchio A.L., Shamir R., Szajewska H. European society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition/European society for pediatric infectious diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014;59(1):132–152. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Herrador B., Carlander A., Ethelberg S., de Blasio B.F., Kuusi M., Lund V., Löfdahl M., MacDonald E., Nichols G., Schönning C., Sudre B. Waterborne outbreaks in the Nordic countries, 1998 to 2012. Eurosurveillance. 2015;20(24):21160. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.24.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock G., Mullin M., MacCallum A., Sherry A., Tetley L., Watson E., Dagleish M., Smith D.G., Everest P. Campylobacter jejuni 81-176 forms distinct microcolonies on in vitro-infected human small intestinal tissue prior to biofilm formation. Microbiology. 2010;156(10):3079–3084. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.039867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson I., Sandberg M., Habib I., Lowman R., Olsson E.E. Knowledge gaps in control of Campylobacter for prevention of campylobacteriosis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:30–48. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer R., Chen P.Y., Armitage J.P., Reinert G., Deane C.M. Deciphering chemotaxis pathways using cross species comparisons. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]