Graphical abstract

Keywords: MET amplification, MET FISH, MET IHC, ddPCR, NanoString, Parallel sequencing

Abstract

In EGFR-treatment naive NSCLC patients, high-level MET amplification is detected in approximately 2–3% and is considered as adverse prognostic factor. Currently, clinical trials with two different inhibitors, capmatinib and tepotinib, are under way both defining different inclusion criteria regarding MET amplification from proven amplification only to defining an exact MET copy number. Here, 45 patient samples, including 10 samples without MET amplification, 5 samples showing a low-level MET amplification, 10 samples with an intermediate-level MET amplification, 10 samples having a high-level MET amplification by a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2.0 and 10 samples showing a high-level MET amplification with GCN ≥6, were evaluated by MET FISH, MET IHC, a ddPCR copy number assay, a NanoString nCounter copy number assay and an amplicon-based parallel sequencing. The MET IHC had the best concordance with MET FISH followed by the NanoString copy number assay, the ddPCR copy number assay and the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays. The concordance was higher in the high-level amplified cohorts than in the low- and intermediate-level amplified cohorts. In summary, currently extraction-based methods cannot replace the MET FISH for the detection of low-level, intermediate-level and high-level MET amplifications, as the number of false negative results is very high. Only for the detection of high-level amplified samples with a gene copy number ≥6 extraction-based methods are a reliable alternative.

1. Introduction

In the past few years, several molecular alterations have been defined as “driver mutations” in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) providing novel treatment options. Besides approved drugs targeting pathologically activated receptors and signaling molecules (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF), other genetic alterations as mutations and gene amplifications of KRAS, ERBB2, and MET, and chromosomal translocations of RET and NTRK are currently under evaluation in clinical trials [1], [2], [3]. This requires the implementation of high-quality molecular diagnostics for the characterization of actionable targets and the control of emerging resistance mechanisms while at the same time taking into account tumor heterogeneity.

The MET gene located on chromosome 7 encodes the receptor tyrosine kinase hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) [4]. MET alterations include copy-number gains, as well as so-called MET exon 14 skipping mutations being single-nucleotide variants or insertions/deletions (indels) in the exon-intron junctions of exon 14 [5], [6]. As this type of mutation confers increased sensitivity to MET inhibitors, clinical studies are under way investigating the role of MET-Inhibitors in MET exon 14 mutated tumors [7], [8]. MET copy number gains are found in the presence and absence of MET exon 14 skipping mutations [6], [9] and can also co-occur with other drivers like EGFR or KRAS mutations [10]. MET amplifications are described in treatment naïve NSCLC patients as well as patients who developed resistance under therapy with either first, second or third generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) [11]. As for the above described MET mutations, different inhibitors are currently tested in clinical studies [12].

Currently, the standard method for the evaluation of MET copy number gains is fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and for NSCLC complex signal patterns are described [10]. For different clinical studies different thresholds for the definition of amplification are used thus it is important to evaluate the most accurate technology to determine MET copy number prior to inclusion of patients. In situ based approaches like FISH and immunohistochemistry (IHC) are hampered by the observer-dependent evaluation but can take into account tumor heterogeneity manifested for example in focal amplification. Methods working with extracted nucleic acids like digital droplet PCR (ddPCR), parallel sequencing or the NanoString nCounter technology are easier to quantify with regard to gene copy number but do not allow morphological correlation.

In this study we compared two in situ based approaches for the analysis of MET amplification with three different assays based on extracted nucleic acids. We used a cohort of well-characterized formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples from patients with NSCLC which was previously characterized by fluorescence in situ hybridization.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Tumor samples and nucleic acid extraction

The registry of the Institute of Pathology of the University Hospital Cologne, Germany, was retrospectively searched for non-small cell lung cancer cases. 45 patient samples were selected with MET FISH results, classified in the following 4 groups: 10 samples without MET amplification, 5 samples showing a low-level MET amplification with ≥40% of tumor cells showing ≥4 MET signals (FISH probes targeting MET), 10 samples with an intermediate-level MET amplification (≥50% of cells containing ≥5 MET signals), 10 samples having a high-level MET amplification by a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2.0 and 10 samples showing a high-level MET amplification with gene copy numbers (GCN) per cell of ≥6, as previously defined [10]. High-level MET amplifications by MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2.0 or by gene copy numbers (GCN) per cell of ≥6 are mutually exclusive in this study.

All samples were routinely formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) according to local practice. 10 µm thick sections were cut from the FFPE tissue blocks and deparaffinized. The tumor areas were macrodissected from unstained slides using a marked hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained slide as a reference.

Samples were digested overnight using proteinase K and DNA was isolated with the Maxwell 16 FFPE Plus Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) on the Maxwell 16 (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions.

2.2. Fluorescence in-situ hybridization

MET FISH analysis was performed on 4 µm thick FFPE slides cut and mounted on Microscope KP-PLUS slides (Klinipath, Duiven, The Netherlands). Tissue slides were hybridized overnight with the Zyto-Light SPEC MET/CEN7 Dual Color Probe (ZytoVision, Bremerhaven, Germany) as previously described [10]. Twenty contiguous tumor cell nuclei from three areas, resulting in a total of 60 nuclei, were individually evaluated. MET/CEN7 ratio, the percentage of tumor cells and the average MET copy number per cell were calculated FISH results were classified in the following 4 groups: High-level amplification was defined in tumors with a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2.0 or an average MET GCN per cell of ≥6.0. Intermediate-level of GCN gain being defined as ≥50% of cells containing ≥5 MET signals. Low-level of GCN gain was defined as ≥40% of tumor cells showing ≥4 MET signals. All other tumors were classified as negative.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

MET IHC was performed on 1–2 µm thick FFPE slides cut and mounted on X-tra Adhesive Slides (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) using a Ventana Benchmark Ultra automated immunostainer and the clone SP44 (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) as previously described [13]. Each sample was assessed using the following scoring criteria for staining intensity: 0 = no staining or <50% of tumor cells with any intensity; 1+ = ≥50% of tumor cells with weak staining but <50% with moderate or higher intensity, 2+ = ≥50% of tumor cells with moderate or higher staining but <50% with strong intensity and 3+ = ≥50% of tumor cells were stained with strong intensity. Score 2+ and 3+ were defined as positive and score 0 and 1+ as negative.

2.4. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) copy number assay

MET ddPCR was performed with the ddPCR probe assay designed for copy number variation analysis: MET, Human (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). EIF2C1 was used as non amplified reference gene. 10 ng of DNA were used for droplet generation and amplification according to the ddPCR CNV Assay protocol including a no template control (BIO-RAD). Amplified droplets were counted with the QX 200 droplet reader and analyzed with the QuantaSoft software (BIO-RAD). Based on previous validation studies, the gene was considered to be a single copy if the average copy number was below 1.4, two copies if between 1.5 and 2.4, three copies if between 2.5 and 3.4 and continued. A GNC ≥2.5 was considered positive, to minimize the number of false positive results.

2.5. NanoString copy number assay

All samples were analyzed for copy-number alterations of MET using the NanoString nCounter platform (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA). Copy number analysis was performed as previously described [13], [14] using 200–600 ng of genomic DNA. Based on the manufacturer’s protocol, published literature [13], [14] and validation studies the gene was considered to be a single copy if the average copy number was below 1.4, two copies if between 1.5 and 2.4, three copies if between 2.5 and 3.4 and continued. A GNC ≥2.5 was considered positive, to minimize the number of false positive results.

2.6. Custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays

For parallel sequencing, the DNA content was measured using a quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) kit (GoTaq qPCR Master Mix; Promega). Isolated DNA was amplified with customized GeneRead DNAseq Targeted Panel V2 containing MET (LUN4, LUN5 – 5 amplicons covering MET) (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the GeneRead DNAseq Panel PCR Kit V2 (Qiagen) or an Ion AmpliSeq Custom DNA Panel containing MET (LUN3 – 1 amplicon covering MET) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and the Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were constructed using the Gene Read DNA Library I Core Kit and the Gene Read DNA I Amp Kit (Qiagen). After end-repair and adenylation, NEXTflex DNA Barcodes were ligated (Bio Scientific, Austin, TX, USA). Barcoded libraries were amplified, and final library products were quantified, diluted, and pooled in equal amounts. Finally, 12 pmol of the constructed libraries was sequenced on the MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with a MiSeq reagent kit V2 (300 cycles) (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Data were exported as FASTQ files.

For copy number detection, mapping was performed by BWA-MEM (BWA Ver. 0.7.17-r1188 [15]) to the reference genome hg19 using the default parameters. Read counts for samples and negative controls were created by GATK Ver. 4.1 CollectReadCounts. Subsequently the negative controls were used for creating the panel of normals (LUN3 n = 9, LUN4 n = 10, LUN5 n = 10) with GATK Ver. 4.1 CreateReadCountPanelOfNormals for each panel. Negative controls were selected from previous sequenced cases with a negative MET amplification status. The read counts of the samples were denoised using GATK Ver. 4.1 DenoiseReadCounts and the average log2 fold change of the MET amplicons was used for further comparison [16]. Samples with a log2 fold ≥0.5 were classified as MET amplified, to minimize the number of false positive results.

2.7. Statistics

Overall percentage agreement (OPA), negative percentage agreement (NPA) and positive percentage agreement (PPA) were calculated between FISH as reference to IHC, NanoString, ddPCR and parallel sequencing.

3. Results

45 samples analyzed by MET FISH were evaluated by MET IHC, the ddPCR copy number assay including MET, the NanoString copy number assay including MET and custom parallel sequencing assays. The 45 samples were divided into 4 cohorts: 10 samples without MET amplification, 5 samples showing a low-level MET amplification with ≥40% of tumor cells showing ≥4 MET signals, 10 samples with an intermediate-level MET amplification (≥50% of cells containing ≥15 MET signals), 10 samples having a high-level MET amplification by a MET/CEN7 ration ≥2.0 and 10 samples showing a high-level MET amplification with GCN per cell of ≥6.

3.1. Immunohistochemistry

All 45 cases were evaluated by MET IHC. In all cohorts MET IHC showed heterogeneous results in comparison to FISH (Table 1). In the cohort without MET amplification 8 cases (80%) had a score of 0–1+ and were classified as negative. Sample 7 had a score of 3+ and sample 1 a score of 2+, both samples were defined as positive. In the MET low-level amplified cohort all 5 samples had a positivity in MET IHC. Only samples 12–14 had scores of ≥2+ and were defined as positive (60%). In the MET intermediate-level amplified cohort 8 of 10 samples had a MET IHC score of 2+ to 3+ and were defined as positive (80%). Two samples, sample 20 and 23 had a MET IHC score of 0. In the high-level amplified cohort with a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2 all samples had a MET IHC score of 2+ to 3+ (100%) and were defined as positive and in the high level amplified cohort with a MET GCN ≥6 9 of 10 samples had a MET IHC score of 2+ to 3+ (90%) and were defined as positive. Sample 36 was negative for MET IHC with a score of 0. In the MET high-level amplified cohorts the concordance between FISH and IHC was higher with 95% compared to the other cohorts were only 19 of 25 samples concurred (76%) (Table 2, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Results of 45 samples analyzed with MET FISH, MET IHC, ddPCR copy number assay, NanoString copy number assay and custom parallel sequencing assays. MET amplified/positive samples are highlighted in grey.

|

|

TCC: Tumor cell content, GCN: Gene copy number.

Table 2.

Concordance between MET FISH and MET IHC, NanoString copy number assay, ddPCR copy number assay and custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays.

|

MET FISH |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MET without amplification | MET low-level amplification | MET intermediate-level amplification | MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2high-level amplification | MET GCN ≥6 high-level amplification | |

| MET IHC | 8/10 (80%) | 3/5 (60%) | 8/10 (80%) | 10/10 (100%) | 9/10 (90%) |

| ddPCR | 8/10 (80%) | 4/5 (80%) | 5/10 (50%) | 5/10 (50%) | 6/10 (60%) |

| NanoString | 9/10 (90%) | 2/5 (40%) | 5/10 (50%) | 7/10 (70%) | 9/10 (90%) |

| Parallel sequencing | 10/10 (100%) | 0/5 (0%) | 4/10 (40%) | 4/10 (40%) | 5/10 (50%) |

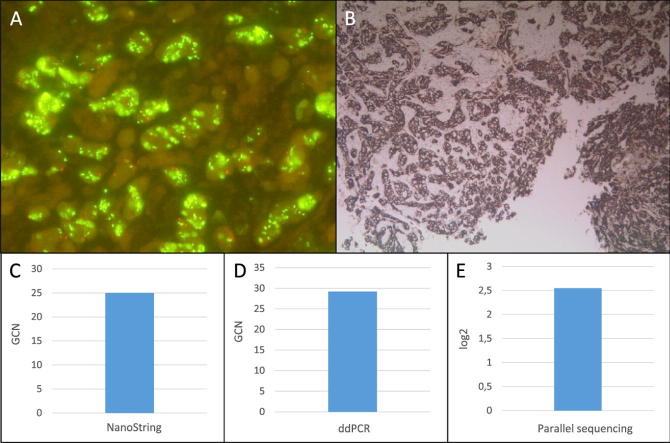

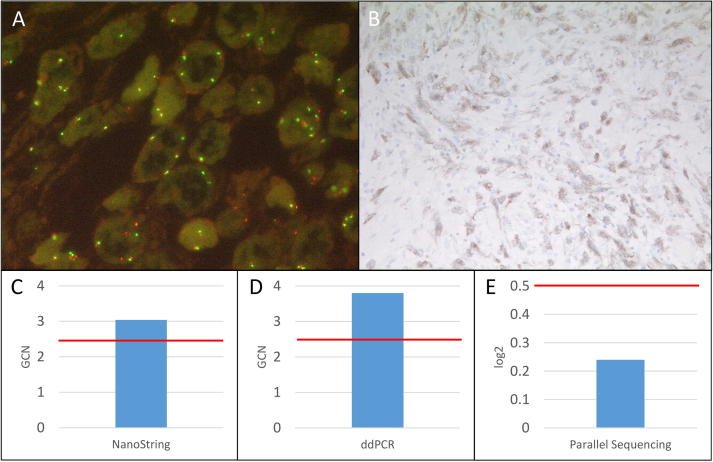

Fig. 1.

Summary of MET high-level amplified sample 45. A: MET FISH high-level (GCN: 29.22) amplification at a magnification of 63x. B: Positive MET IHC (3+) at a magnification of 10x. C: MET amplification detected with the NanoString copy number assay (GCN: 25). D: MET amplification detected with the ddPCR copy number assay (GCN: 29.2). E: MET amplification detected with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assay (log2: 2.55). GCN: Gene copy number. Red bar: Cut-off positivity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

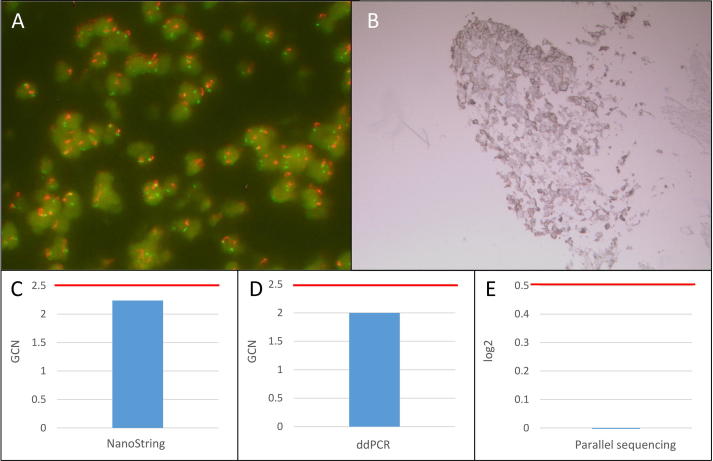

Fig. 2.

Summary of MET FISH high-level amplified sample 41. A: MET FISH high-level (GCN: 6.38) amplification at a magnification of 63x. B: Positive MET IHC (2+) at a magnification of 10x. C: No MET amplification detected with the NanoString copy number assay (GCN: 2.24). D: No MET amplification detected with the ddPCR copy number assay (GCN: 2.00). E: No MET amplification detected with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assay (log2: −0.08). GCN: Gene copy number. Red bar: Cut-off positivity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

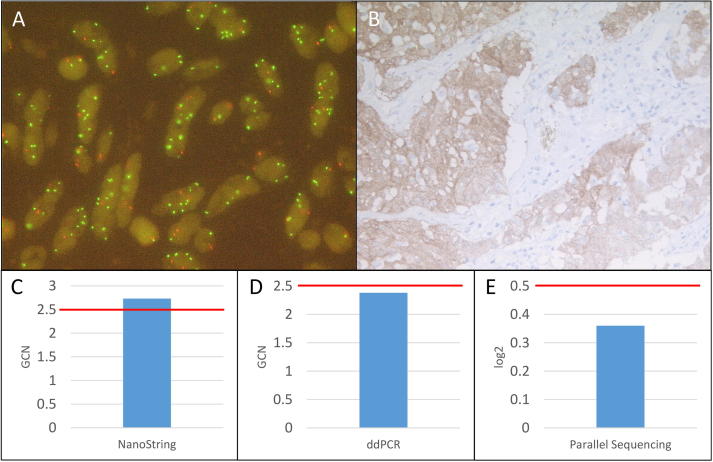

Fig. 3.

Summary of MET FISH high-level amplified sample 32. A: MET FISH high-level (Ratio: 2.77) amplification at a magnification of 63x. B: Positive MET IHC (3+) at a magnification of 10x. C: MET amplification detected with the NanoString copy number assay (GCN: 2.73). D: No MET amplification detected with the ddPCR copy number assay (GCN: 2.38). E: No MET amplification detected with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assay (log2: 0.36). GCN: Gene copy number. Red bar: Cut-off positivity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

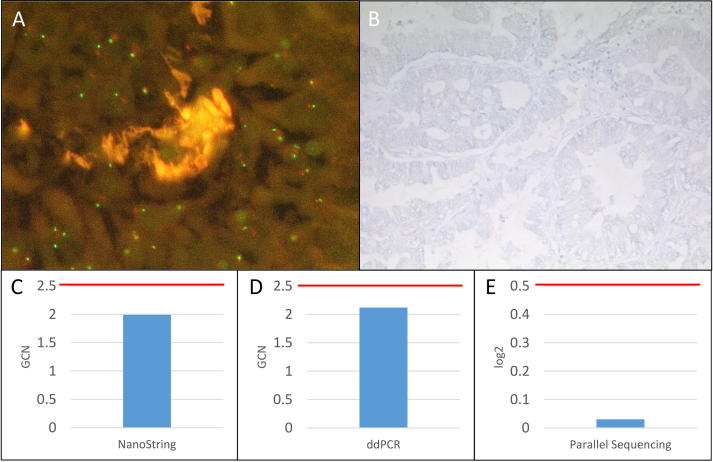

Fig. 4.

Summary of MET FISH not amplified sample 4. A: No MET FISH amplification at a magnification of 63x. B: Negative MET IHC (0) at a magnification of 10x. C: No MET amplification detected with the NanoString copy number assay (GCN: 1.99). D: No MET amplification detected with the ddPCR copy number assay (GCN: 2.12). E: No MET amplification detected with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assay (log2: −0.03). GCN: Gene copy number. Red bar: Cut-off positivity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

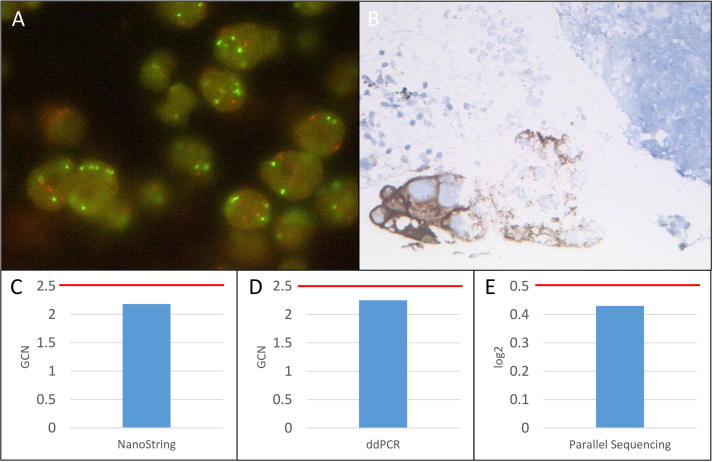

Fig. 5.

Summary of MET FISH low-level amplified sample 12. A: MET FISH low-level (41.67%≥4 MET signals) amplification at a magnification of 63x. B: Positive MET IHC (2+) at a magnification of 10x. C: MET amplification detected with the NanoString copy number assay (GCN: 3.04). D: MET amplification detected with the ddPCR copy number assay (GCN: 3.80). E: No MET amplification detected with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assay (log2: 0.24). GCN: Gene copy number. Red bar: Cut-off positivity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 6.

Summary of MET FISH high-level amplified sample 21. A: MET FISH intermediate-level (71.67%≥5 MET signals) amplification at a magnification of 63x. B: Positive MET IHC (3+) at a magnification of 10x. C: No MET amplification detected with the NanoString copy number assay (GCN: 2.18). D: No MET amplification detected with the ddPCR copy number assay (GCN: 2.25). E: No MET amplification detected with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assay (log2: 0.43). GCN: Gene copy number. Red bar: Cut-off positivity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Droplet digital PCR copy number assay

The results of the ddPCR copy number assay are depicted in Table 1. For all samples the ddPCR copy number assay was performed. In the cohort without MET amplification 8 of 10 (80%) samples had a copy number below 2.5 and were classified as negative. Samples 1 and 6 were positive by the ddPCR copy number assay. In the MET low-level amplified cohort 4 of 5 samples (80%) had a GCN higher than 2.5 and in the MET intermediate-level amplified cohort 5 of 10 samples (50%) had a GCN higher than 2.5 and were classified as positive. In the high-level amplified cohort with a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2 5 of 10 samples (50%) were positive with a GCN higher than 2.5 and in the high level amplified cohort with a MET GCN ≥6 6 of 10 samples (60%) were positive with a GCN ≥2.5. Sample 43 was negative in the ddPCR copy number assay although the GCN determined by FISH was very high with 22.8. This sample had a tumor cell content of only 30%. In summary, in the MET high-level amplified cohorts there were only 11 of 20 samples with matching results comparing MET FISH and the ddPCR copy number assay (55%) whereas in the other three cohorts 17 of 25 samples concurred (68%) (Table 2, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

3.3. NanoString copy number assay

The NanoString copy number assay was performed for all 45 samples (Table 1). In the cohort without MET amplification 9 of 10 samples (90%) had a GCN of less than 2.5 and were classified as negative. Only sample 8 was borderline positive with a GCN of 2.8. In the MET low-level amplified cohort 2 of 5 samples (40%) and in the MET intermediate-level amplified cohort 5 of 10 samples (50%) were positive with a GCN of ≥2.5. In the high-level amplified cohort with a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2 7 of 10 samples (70%) were positive with a GCN higher than 2.5 and in the high level amplified cohort with a MET GCN ≥6 9 of 10 samples (90%) were positive with a GCN ≥2.5. In the latter cohort only sample 41 was negative with a GCN of 2.2, but this sample was flagged by the NanoString copy number assay as not having enough DNA for the assay and the sample was also negative by the ddPCR copy number assay and the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays. In summary, in the MET high-level amplified cohorts 16 of 20 samples (80%) showed consistent results with the MET FISH whereas in the other cohorts only 16 of 25 samples had matching results (64%) (Table 2, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

3.4. Custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays

The results of the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays are depicted in Table 1. For all samples parallel sequencing was performed. In the cohort without MET amplification 10 of 10 samples (100%) had a log2 less than 0.5 and were classified as negative. In the MET low-level amplified cohort 0 of 5 samples (0%) had a log2 higher than 0.5 and in the MET intermediate-level amplified cohort 4 of 10 samples (40%) had a log2 higher than 0.5 and were classified as positive. In the high-level amplified cohort with a MET/CEN7 ratio ≥2 4 of 10 samples (40%) were positive with a log 2 higher than 0.5 and in the high level amplified cohort with a MET GCN ≥6 5 of 10 (50%) were positive with a log2 ≥0.5. In summary, the MET high-level amplified cohorts showed a concordance of 45% (9 of 20 samples) with the MET FISH. The other cohorts had matching results in 14 of 25 samples (56%) (Table 2, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Comparing the different panels used, LUN3 had a total concordance of 62.5% (5 of 8 samples), LUN4 of 44.8% (13 of 29 samples) and LUN5 of 62.5% (5 of 8 samples). With LUN4 the most samples were analyzed.

In summary, the MET IHC had the best agreement with FISH followed by NanoString copy number assay, ddPCR copy number assay and the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays (Table 2, Table 3). The performance of immunohistochemistry testing as well as the extraction-based methods is also described by calculating positive percent agreement (PPA), negative percent agreement (NPA), and overall percent agreement (OPA) (Table 3). Compared to FISH the number of false positives for all methods is low but especially for the extraction-based methods there is a high number of false negatives.

Table 3.

Estimation of agreement between FISH and alternative testing methods. Positive percent agreement (PPA), negative percent agreement (NPA), and overall percent agreement (OPA) for each comparison was calculated using the definition of positive and negative results as described.

| IHC | NanoString | ddPCR | Parallel sequencing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPA | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| PPA | 0.94 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| NPA | 0.62 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.31 |

| Kappa | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

4. Discussion

In EGFR-treatment naive NSCLC patients, high-level MET amplification is detected in approximately 2–3% and is considered as adverse prognostic factor [17]. Only few data on treatment of these patients with MET inhibitors are available [18] and two previous clinical studies where patients had been selected based on MET immunohistochemical expression failed [19], [20]. A technical comparison on MET expression analysis by immunohistochemistry also showed a high interlaboratory variability and highlighted the need for harmonization of MET IHC [21]. Nevertheless, in other studies MET IHC positivity was significantly (P < 0.001, χ2 test) associated with MET high-level amplification and MET high-level amplified samples can be selected by high MET IHC scores, which is in concordance with our study [13], [22].

Currently, clinical trials with two different inhibitors, capmatinib and tepotinib, are under way [12], [23], [24] both defining different inclusion criteria regarding MET amplification from proven amplification only to defining an exact MET copy number.

This highlights the need for an accurate predictive biomarker test prior to MET directed treatment to evaluate the true prevalence of MET overexpression and amplification. In this study, conventional slide-based approaches FISH and IHC were compared with the results of three extraction-based methods, ddPCR, the NanoString nCounter technology and amplicon-based parallel sequencing for the detection of MET amplifications. The use of extraction-based methods is not subjected to interobserver variability because a well defined cut-off value by extensive validation studies can be applied. Further, laborious evaluation by a trained pathologist can be avoided.

Depending on the inclusion criteria of clinical studies different extraction-based technologies can be used instead of MET FISH or MET IHC. For clinical studies including only MET high-level amplified samples with a high gene copy number the NanoString copy number assay gave the best results in comparison to the MET FISH. However, this technology is hampered by the large amount of DNA needed for analysis, which is not available for most lung cancer biopsies.

Also for ddPCR, previous studies showed a very strong correlation of the ddPCR copy number assay and MET FISH high-level amplification (MET/CEN7 ratio of ≥2), but this is in contrast to our study where only 50% of samples matched [25].

In the extraction-based technologies, however, intratumoral heterogeneity in the signal pattern of the MET FISH can result in a lower MET copy numbers and thus in false negative results. Partly, this has been reported previously [13]. It was also shown in gastric-/esophageal adenocarcinoma that MET amplification was markedly higher in tumor specimens with a heterogeneous signal distribution [26], which might be problematic for the detection by extraction-based technologies. Further, in our study FFPE material with varying DNA quality was used, therefore after extensive validation, literature research [13], [14] and manufactures instruction the cut-offs were set quite high to a gene copy number ≥2.5 and a log2 ≥0.5 to decrease the number of false positives by elevated background noise.

For future analysis, MET copy number detection by parallel sequencing is the most promising technology as small variants as well as gene copy number changes of many genes and samples can be detected at the same time. However, in our study parallel sequencing data was the least reliable method. In our study, notably a tumor cell content below 50% led to false negative results, as the detection limit was set relatively high to minimize false positive results. In general, gene copy number detection with the custom amplicon-based parallel sequencing assays is very sensitive to tumor complexity like tumor purity and heterogeneity as previously described [27], [28], [29].

Further, an amplicon-based parallel sequencing approach without unique molecular identifier were used and the panel of normals consisted of negative samples and not normal tissue, which might have influenced the analysis. In previous studies was shown, that the detection limit increases with a decreasing tumor cell content. Here, amplification calling on calls of more than one amplicon can increase the sensitivity and lower the detection limit [30]. In our study, no differences between the panels using only one amplicon or five amplicons were seen. However, our sample numbers are too small to draw a final conclusion and more research is needed.

In conclusion, our study showed that currently extraction-based methods cannot replace the MET FISH for the detection of low-level, intermediate-level and high-level MET amplifications, as the number of false negative results is very high. Currently, clinical trials with different MET inhibitors are ongoing but the role for MET amplification as predictive biomarker is still ambiguous [31]. This can at least in part be attributed to the inappropriate definition of MET amplification. The outcome of these clinical trials will show the clinical relevance of the different groups of MET amplification status determined by FISH, as the published MET FISH amplification criteria [10] are only descriptive and are not based on clinical screening programs. Extraction-based methods are only able to replace the MET FISH reliably for the detection of high-level amplified samples with a GCN ≥10.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

We thank Elke Binot and Christian Reinboth for technical support.

Contributor Information

Carina Heydt, Email: carina.heydt@uk-koeln.de.

Svenja Wagener-Ryczek, Email: svenja.wagener-ryczek@uk-koeln.de.

Markus Ball, Email: markus.ball@uk-koeln.de.

Anne M. Schultheis, Email: anne.schultheis@uk-koeln.de.

Simon Schallenberg, Email: simon.schallenberg@charite.de.

Vanessa Rüsseler, Email: vanessa.ruesseler@uk-koeln.de.

Reinhard Büttner, Email: reinhard.buettner@uk-koeln.de.

Sabine Merkelbach-Bruse, Email: sabine.merkelbach-bruse@uk-koeln.de.

References

- 1.Halliday P.R., Blakely C.M., Bivona T.G. Emerging targeted therapies for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Current Oncol Rep. 2019;21:21. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M., Rabe K.F. Precision diagnosis and treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:849–861. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanton C., Govindan R. Clinical implications of genomic discoveries in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1864–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1504688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seki T., Hagiya M., Shimonishi M., Nakamura T., Shimizu S. Organization of the human hepatocyte growth factor-encoding gene. Gene. 1991;102:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90080-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappuzzo F., Janne P.A., Skokan M., Finocchiaro G., Rossi E., Ligorio C. MET increased gene copy number and primary resistance to gefitinib therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:298–304. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onozato R., Kosaka T., Kuwano H., Sekido Y., Yatabe Y., Mitsudomi T. Activation of MET by gene amplification or by splice mutations deleting the juxtamembrane domain in primary resected lung cancers. J Thoracic Oncol. 2009;4:5–11. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181913e0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frampton G.M., Ali S.M., Rosenzweig M., Chmielecki J., Lu X., Bauer T.M. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer Disc. 2015;5:850–859. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf J., Orlov S.V., Smit E.F., Souquet P.-J., Vansteenkiste J.F., Robeva A. LBA52Results of the GEOMETRY mono-1 phase II study for evaluation of the MET inhibitor capmatinib (INC280) in patients (pts) with METΔex14 mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Ann Oncol. 2018;29:viii741. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Awad M.M., Oxnard G.R., Jackman D.M., Savukoski D.O., Hall D., Shivdasani P. MET exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer are associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic amplification and c-Met overexpression. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:721–730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schildhaus H.U., Schultheis A.M., Ruschoff J., Binot E., Merkelbach-Bruse S., Fassunke J. MET amplification status in therapy-naive adeno- and squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:907–915. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michels S., Heydt C., Bv V., Deschler-Baier B., Pardo N., Monkhorst K. Genomic profiling identifies outcome-relevant mechanisms of innate and acquired resistance to third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in lung cancer. JCO Prec Oncol. 2019:1–14. doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paik P., Sakai H., Bruns R., Scheele J., Straub J., Felip E. 546TiPTepotinib in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with MET-exon 14 skipping mutations (METex14+) and MET amplification (METamp); A phase II trial in progress. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:ix169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castiglione R., Alidousty C., Holz B., Wagener S., Baar T., Heydt C. Comparison of the genomic background of MET-altered carcinomas of the lung: biological differences and analogies. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:627–638. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alidousty C., Baar T., Martelotto L.G., Heydt C., Wagener S., Fassunke J. Genetic instability and recurrent MYC amplification in ALK-translocated NSCLC: a central role of TP53 mutations. J Pathol. 2018;246:67–76. doi: 10.1002/path.5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.arXiv CU. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM, https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (15.04.2019, date last accessed). 2019 [cited 2019].

- 16.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuda K., Sasaki H., Yukiue H., Yano M., Fujii Y. Met gene copy number predicts the prognosis for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2280–2285. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ou S.H., Kwak E.L., Siwak-Tapp C., Dy J., Bergethon K., Clark J.W. Activity of crizotinib (PF02341066), a dual mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor, in a non-small cell lung cancer patient with de novo MET amplification. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:942–946. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821528d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scagliotti G.V., Novello S., Schiller J.H., Hirsh V., Sequist L.V., Soria J.C. Rationale and design of MARQUEE: a phase III, randomized, double-blind study of tivantinib plus erlotinib versus placebo plus erlotinib in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic, nonsquamous, non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spigel D.R., Edelman M.J., Mok T., O'Byrne K., Paz-Ares L., Yu W. Treatment rationale study design for the MetLung trial: a randomized, double-blind phase III study of onartuzumab (MetMAb) in combination with erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in patients who have received standard chemotherapy for stage IIIB or IV met-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bubendorf L., Dafni U., Schobel M., Finn S.P., Tischler V., Sejda A. Prevalence and clinical association of MET gene overexpression and amplification in patients with NSCLC: Results from the European Thoracic Oncology Platform (ETOP) Lungscape project. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S., Koh J., Kim D.W., Kim M., Keam B., Kim T.M. MET amplification, protein expression, and mutations in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2015;90:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauer T.M., Schuler M., Berardi R., Lim W.-T., Van Geel R., De Jonge M. MINI01.03: Phase (Ph) I study of the safety and efficacy of the cMET inhibitor capmatinib (INC280) in patients with advanced cMET+ NSCLC: topic: medical oncology. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11 pp. S257-S8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (15.04.2019, date last accessed).

- 25.Zhang Y., Tang E.T., Du Z. Detection of MET gene copy number in cancer samples using the droplet digital PCR method. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorgensen J.T., Nielsen K.B., Mollerup J., Jepsen A., Go N. Detection of MET amplification in gastroesophageal tumor specimens using IQFISH. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:458. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.09.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bao L., Pu M., Messer K. AbsCN-seq: a statistical method to estimate tumor purity, ploidy and absolute copy numbers from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1056–1063. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zare F., Dow M., Monteleone N., Hosny A., Nabavi S. An evaluation of copy number variation detection tools for cancer using whole exome sequencing data. BMC Bioinf. 2017;18:286. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1705-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao M., Wang Q., Wang Q., Jia P., Zhao Z. Computational tools for copy number variation (CNV) detection using next-generation sequencing data: features and perspectives. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14(Suppl 11):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S11-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Budczies J., Pfarr N., Stenzinger A., Treue D., Endris V., Ismaeel F. Ioncopy: a novel method for calling copy number alterations in amplicon sequencing data including significance assessment. Oncotarget. 2016;7:13236–13247. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vansteenkiste J.F., Van De Kerkhove C., Wauters E., Van Mol P. Capmatinib for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19:659–671. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1643239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]