Abstract

Humans are exposed to antimicrobial agent triclosan (TCS) through use of TCS-containing products. Exposed tissues contain mast cells, which are involved in numerous biological functions and diseases by secreting various chemical mediators through a process termed degranulation. We previously demonstrated that TCS inhibits both Ca2+ influx into antigen (Ag)-stimulated mast cells and subsequent degranulation. In order to determine the mechanism linking triclosan’s cytosolic Ca2+ depression to inhibited degranulation, we investigated TCS effects on crucial signaling enzymes activated downstream of Ca2+ rise: protein kinase C (PKC; activated by Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species, ROS) and phospholipase D (PLD). We found that TCS strongly inhibits PLD activity within 15 min post-Ag, a key mechanism of TCS mast cell inhibition. Also, experiments using fluorescent constructs and confocal microscopy indicate that TCS delays Ag-induced translocations of PKCβII, PKCδ, and PKC substrate MARCKS. Surprisingly, TCS does not inhibit PKC activity or overall ability to translocate, and TCS actually increases PKC activity by 45 min post-Ag; these results are explained by the timing of both TCS inhibition of cytosolic Ca2+ (~15+ min post-Ag) and TCS stimulation of ROS (~45 min post-Ag). These results demonstrate that it is incorrect to assume that all Ca2+-dependent processes will be synchronously inhibited when cytosolic Ca2+ is inhibited by a toxicant or drug. These results offer molecular predictions of triclosan’s effects on other mammalian cell types which share these crucial signal transduction elements and provide biochemical information that may underlie recent epidemiological findings implicating TCS in human health problems.

Keywords: triclosan, mast cell, protein kinase C, phospholipase D, calcium, degranulation

Short Abstract:

Mast cells are involved in numerous biological functions and diseases by secreting various chemical mediators through a process termed degranulation. Protein kinase C and phospholipase D are enzymes crucial to this process. Antimicrobial triclosan inhibits mast cell degranulation via phospholipase D inhibition. Triclosan does not affect protein kinase C activity but delays its movement. Ca2+-dependent biomolecules are not always inhibited when Ca2+ is inhibited by drug. Triclosan modes of action predict other cellular effects.

Introduction

Triclosan (TCS) is a synthetic antimicrobial agent that was recently banned by the FDA from both consumer (Kux, 2016) and hospital soap products (Fischer, 2017). However, TCS still remains, at high concentrations, in other consumer products (e.g., toys, kitchenware, etc.). TCS is readily absorbed when applied to human tissues. The resulting human tissue levels are comparable to exposure levels used in this current cell study (Weatherly et al., 2017). Additionally, micromolar levels of TCS have been found in human body fluids in several studies (reviewed in (Weatherly & Gosse, 2017)).

Clinically, TCS has been used primarily as an antimicrobial (Daoud et al., 2014), including for treatment of the gingiva (Rover et al., 2014), and there have also been some potentially positive findings of TCS treatment of atopic dermatitis (Tan et al., 2010), which may be due to triclosan’s ability to inhibit mast cell function (Palmer et al., 2012). However, numerous recent epidemiological studies report detrimental TCS effects on human health, including problems with thyroid function (Wang et al., 2017), reproduction (Hua et al., 2017), immune function, development (Wei et al., 2017) (reviewed in (Weatherly & Gosse, 2017)). Additional recent epidemiological studies have also revealed increased risks of gestational diabetes (Ouyang et al., 2018), abnormalities of sperm morphology (Jurewicz et al., 2018), and lowered cognitive test scores in children (Jackson-Browne et al., 2018), due to triclosan exposure. The cellular, molecular, and biochemical reasons for these health effects of TCS are not completely understood but include mitochondrial toxicity (Ajao et al., 2015; Shim et al., 2016; Weatherly et al., 2016), reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (Lv et al., 2016), interference with cellular calcium dynamics (Ahn et al., 2008; Cherednichenko et al., 2012; Weatherly et al., 2018), endocrine disruption (Ruszkiewicz et al., 2017), and modulation of cytokine gene expression (Marshall et al., 2015; Yueh et al., 2014).

As noted above, TCS inhibits mast cell (MC) function (Palmer et al., 2012; Weatherly et al., 2013). MCs are found in nearly every human body tissue and in numerous other species (Kuby, 1997). MCs are key players in many physiological and pathological processes including allergy, asthma, autoimmunity, infectious disease, cancer, and even many central nervous system disorders such as autism, anxiety, and multiple sclerosis (Galli et al., 2005; Girolamo et al., 2017; Metcalfe et al., 1997; Silver et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2000). Therefore, inhibition of MC function has many potential consequences on human health. Many of the biochemical events crucial to MC function (such as cytoskeletal involvement, calcium signaling, protein kinase C, etc.) are also essential to signaling in numerous distinct cell types, including neurons and T cells. Thus, discovery of the biochemical mechanisms underlying TCS disruption of MCs leads to predictions of TCS effects in disparate cell types that share common signal transduction elements.

Mast cells are activated by binding of multivalent antigen (Ag) to immunoglobulin E (IgE)-bound cell surface FcεRI receptors (Kinet et al., 1983), resulting in degranulation: secretion of cytoplasmic granules which contain mediators such as histamine, tryptase, β-hexosaminidase, serotonin, cytokines, chemokines, and lipid mediators (Schwartz et al., 1980). FcεRI crosslinking by Ag leads to a tyrosine phosphorylation cascade that activates phospholipase C (PLC) γ, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to yield diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5- trisphosphate (IP3). While DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC) (Steinberg, 2008), IP3 binds to its receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) causes an efflux of Ca2+ from the ER (Berridge, 1993), into the cytosol and also into mitochondria (Furuno et al., 2015; Takekawa et al., 2012). Next, calcium release-activated calcium (CRAC) channels in the plasma membrane are activated, resulting in a flood of calcium into the cytosol (Putney et al., 2001).

Within the cytosol, this elevated Ca2+, along with DAG and ROS (Swindle et al., 2004), binds to and activates the Ser/Thr family of protein kinase C (PKC) (Ozawa, Yamada, et al., 1993; Steinberg, 2008). PKC isozymes are categorized into three subfamilies (classical [cPKC], novel [nPKC], and atypical [aPKC]), according to their biochemical and structural properties, such as their binding to DAG and/or Ca2+ (Newton, 1995, 2001; Ozawa, Yamada, et al., 1993). Of particular importance in mast cells are certain cPKC isoforms (PKC α, βI, βII, and γ), which have conserved C1 domains (which bind DAG) (Newton, 2001) and C2 domains (which bind Ca2+ and acidic phospholipids). Also important to mast cell function are certain nPKC isoforms (PKC δ, ε, θ, and η), which are activated by DAG by binding to the C1 domain but which are lacking functional C2 domains and, thus, are lacking Ca2+ responsiveness (Newton, 1995). In addition to DAG, activators of PKC δ include various agents such as phorbol esters, UV or ionizing radiation, growth factors, and ROS (H. G. Lee et al., 2010; Yoshida, 2007). PKC β and δ, which belong to cPKC and nPKC, respectively, are particularly important in IgE–mediated mast cell degranulation (Cho et al., 2004; Nechushtan et al., 2000; Ozawa, Szallasi, et al., 1993; Wolfe et al., 1996; Yanase et al., 2011). Stimulation of RBL-2H3 cells with either Ag or Ca2+ ionophore causes a rapid translocation of PKC δ from the cytosol to the plasma membrane (Cho et al., 2004). Also, PKC δ translocation and degranulation are both activated by ROS generation in mast cells (Cho et al., 2004).

Activation of PKC causes its translocation from the cytosol to the plasma membrane, serving as a hallmark for PKC activation (Kraft et al., 1983). Inactive PKC is located in the cytosol and autoinhibited by a pseudosubstrate (G. C. Brown et al., 1999; Nishizuka, 1995). When Ca2+ binds to cytosolic PKC and alters its electrostatics and, hence, membrane lipid affinity (Codazzi et al., 2001), it can then bind DAG in the plasma membrane, leading to full activation of PKC by removal of pseudosubstrate from the active site. In other cases, DAG alone can recruit cytosolic PKC to the plasma membrane and induce conformational changes to activate PKC (Jaken et al., 2000; Nishizuka, 1995). Once PKC is translocated and active, it phosphorylates substrates in its proximity in or near the plasma membrane. One PKC substrate is myosin, the phosphorylation of which is important for actin cytoskeletal rearrangements (“membrane ruffling”) and degranulation (O. H. Choi et al., 1994; Ludowyke et al., 1989).

Another of PKC’s substrates is myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) (Aderem, 1992). In unstimulated cells, MARCKS tightly binds to PIP2 at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (Heo et al., 2006). When phosphorylated by activated/translocated PKC, MARCKS dissociates from the plasma membrane and enters the cytosol, thus exposing PIP2 to be accessible to other proteins (such as PLCγ) for signaling (Gadi et al., 2011). In addition, along with Ca2+, PIP2 is involved in the soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE)-mediated exocytotic machinery required for degranulation (Tadokoro et al., 2015).

Another major target of PKC is phospholipase D (PLD). Increases in intracellular Ca2+ and PKC translocation work in tandem to activate PLD in mast cells (Lin et al., 1992). Although there are many studies in other cell types showing that intracellular Ca2+ activates PLD activity (Exton, 1999; Qin et al., 2009), the mechanisms of PLD activation by Ca2+ remain to be elucidated. Structural analyses have shown that mammalian PLD does not contain a Ca2+ binding domain but does contain lipid (PIP3 and PIP2) -binding domains and a PKC-binding domain (Henage et al., 2006; Selvy et al., 2011). While a study showed that mammalian PLD activity is insensitive to changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in vitro (Hammond et al., 1997), Ca2+ and PIP2 act as essential cofactors for mammalian PLD activation within cells (Henage et al., 2006; Sciorra et al., 2002; Selvy et al., 2011). PLD activation involves Ca2+-dependent PKC isoforms (Qin et al., 2009; Wakelam et al., 1997). A study using RBL-2H3 mast cells showed that PKC inhibitors decrease PLD activity and, subsequently, inhibit degranulation, suggesting a close relationship between PKC/PLD activation and degranulation in mast cells (Chahdi et al., 2002).

PLD hydrolyzes phosphatidylcholine, creating phosphatidic acid (PA), an important second messenger (Cockcroft, 2001; O’Luanaigh et al., 2002; Wakelam et al., 1997; Zeniou-Meyer et al., 2007). PA stimulates PLCγ (Nishizuka, 1995) and also can be converted directly into DAG by PA phosphohydrolase—leading to a secondary rise in intracellular DAG levels (Nakashima et al., 1991). These increases in DAG are involved in activation of the DAG-dependent PKC isoforms (Baldassare et al., 1992; Nishizuka, 1995; Z. Peng et al., 2005), suggesting that PKC-PLD activation is closely regulated in a complementary manner between the two enzymes in mast cells. Additionally, PA plays a critical role in regulating mast cell morphology (C. M. M. Marchini-Alves et al., 2012). Continual activity of PLD2 is required for membrane ruffling in mast cells (O’Luanaigh et al., 2002).

Two mammalian isoforms, PLD1 and 2, are expressed in mast cells. PLD1 localizes to cytoplasmic granules and has low basal activity whereas PLD2 is constitutively expressed at a high level and is located at the plasma membrane (W. S. Choi et al., 2002; J. H. Lee et al., 2006). Stimulation of mast cells activates both PLD isoforms, but only PLD1 undergoes translocation to the plasma membrane and drastic upregulation of its activity (F. D. Brown et al., 1998). Even though many studies have agreed on the location and expression of PLD isoforms in mast cells, there have been controversial and conflicting data regarding the functions of these isoforms. Several studies have reported positive roles of both PLD isoforms in mast cell degranulation (F. D. Brown et al., 1998; Chahdi et al., 2002; J. H. Lee et al., 2006; Z. Peng & Beaven, 2005), with PLD1 involved in granule translocation and with PLD2 involved in membrane fusion of these granules (W. S. Choi et al., 2002). However, one intriguing recent study using PLD1- and PLD2-knockout mice found that PLD1 positively regulates degranulation, while PLD2 is a negative regulator (PLD2 deficiency enhanced microtubule formation) (Zhu et al., 2015).

Microtubule polymerization is another essential player: granules are mobilized to the plasma membrane along microtubules for degranulation (Smith et al., 2003). Agents that inhibit microtubule polymerization inhibit degranulation (Marti-Verdeaux et al., 2003; Tasaka et al., 1991; Urata et al., 1985). Once granules are moved to the plasma membrane, they dock and fuse with the help of PLD and SNAREs in a Ca2+-dependent process (Baram et al., 1999; Blank et al., 2002; Z. H. Guo et al., 1998; Paumet et al., 2000; Woska et al., 2012), resulting in degranulation.

Previously, we discovered that non-cytotoxic doses of TCS (5–20 μM), within 1 hour (15 min-1 hour) cause strong, dose-dependent inhibition of degranulation (in either the rat mast cell model RBL-2H3 or the human mast cell line HMC-1) (Palmer et al., 2012; Weatherly et al., 2013; Weatherly et al., 2016), and here we have sought to determine the underlying molecular mechanisms. Recently, we discovered that TCS drastically interferes with mast cell Ca2+ dynamics, at the ER, mitochondria, and cytosolic influx across the plasma membrane (Weatherly et al., 2018). Therefore, we hypothesized that the cellular translocation and activity of Ca2+-activated PKC and PLD enzymes, as well as the translocation of PKC substrate MARCKS, would be inhibited by TCS exposure. For these studies, we have utilized RBL-2H3 cells, which contain biochemical signaling machinery closely similar to that of primary human and rodent mast cells (Abramson et al., 2007; Fewtrell, 1979; J. Lee et al., 2012; Metcalfe et al., 1997; Metzger et al., 1986; Seldin et al., 1985). Biochemically and functionally, RBL-2H3 cells respond to exogenous agents in a fashion similar to that of primary bone marrow-derived mast cells (including upon exposure to parasite infection (Thrasher et al., 2013), silver nanoparticles (Alsaleh et al., 2016), endocrine disruptors (Zaitsu et al., 2007)).

Here, we report that the effects of TCS on PKC, MARCKS, and PLD localization and activity in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells using biochemical assays and live-cell/real-time confocal microscopy. We have discovered that TCS delays translocation of PKC βII and δ to the plasma membrane and subsequently delays MARCKS dissociation from the plasma membrane, even while, surprisingly, overall PKC activity is uninhibited by TCS. Furthermore, we found that PLD activity in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells is decreased, a key mechanism underlying TCS inhibition of degranulation. Together with our earlier published findings, these results paint a mechanistic picture of triclosan’s mode of action on mast cells and pinpoint the timing of TCS-induced defects in the mast cell signaling pathway.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

TCS (99%; Sigma-Aldrich) was freshly prepared each day in aqueous Tyrodes buffer as described in (Weatherly et al., 2013) and was used at non-cytotoxic doses (Palmer et al., 2012). 5-Fluoro-2-indolyl des-chlorohalopemide (FIPI)(Calbiochem) was dissolved in 100% DMSO to obtain 1 mM stock. Further dilutions were made in bovine serum albumin (BSA)-Tyrodes (BT) buffer to make 75nM (0.0075% DMSO) and 150 nM (0.015% DMSO). Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma) was dissolved in 100% ethanol to be 200 mM and was stored at −20 °C.

Cell culture

RBL-2H3 (“RBL”) mast cells were cultured as in (Hutchinson et al., 2011) and (Weatherly et al., 2013).

Protein kinase C activity assay (ELISA)

A PKC Kinase activity kit (Enzo Life Science) was used to simultaneously measure the activity of multiple PKC isoforms (PKC α, βI, βII, γ, δ, ε, η, and θ). RBL-2H3 cells were plated in 10 cm2 tissue culture-treated sterile dishes (Greiner Bio-One) (1.14 × 107 cells per dish, in 6.5 mL media) and were incubated overnight (12–16 h) at 37 °C/5% CO2. The following day, cells were sensitized with 0.1 μg/mL monoclonal anti-dinitrophenol (DNP) mouse immunoglobulin E (IgE; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at 37 °C/5% CO2 in RBL media. After IgE sensitization, spent IgE media was discarded, and cells were washed with warm BT to remove excess IgE. Next, cells were exposed to either BT (control) or multivalent DNP–BSA antigen (Ag) in BT ± 10μM TCS for 10 to 45 minutes at 37 °C. Cell lysis buffer (1X; Cell Signaling Technology) was prepared from 10X stock, via dilution in PBS. Immediately before use, PMSF was added to this 1X cell lysis buffer for a final concentration of 1mM PMSF. After incubation, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, then incubated for 1.5 minutes on ice with 400μL of ice-cold 1X cell lysis buffer containing 1mM PMSF. Next, cells were harvested by cell scraper (Falcon) and were placed into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes and further lysed using a sonicator (Branson sonifier, Branson Ultrasonics Corporation; set at output control 5 Watts, duty cycle of 30, 1 sec duration per sonication pulse, with a 5 sec break on ice in between sonications). Finally, the sonicated cells were centrifuged at 14,400xg for 10 minutes at 4°C, and lysate supernatants (technical duplicates, 30 μL per ELISA well, from each cell lysate) were used in the ELISA following the manufacturer’s protocol (except 1x lysis buffer was used as a background in place of the kinase assay dilution buffer included in the kit). PKC activity was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy 2; Biotek). During the 90 min primary antibody incubation step of the PKC ELISA, a 25 μL aliquot of the remaining of cell supernatant of each sample was diverted for use in total protein concentration determination. The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay was performed, using Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Raw absorbance ELISA data were processed by first subtracting average background values (kit reagents in 1X lysis buffer with no cell supernatant) from each sample, and the background-subtracted duplicates were then averaged. These values were then divided by the total protein concentration of that particular sample, and finally were normalized to the unstimulated (no Ag) control for each experimental day. The percent increase of PKC activity over control was determined by subtracting the normalized control value from the normalized Ag or Ag + TCS values and dividing this number by the control value.

Confocal imaging

RBL-2H3 cells were transfected via electroporation using Amaxa Nucleofector kit T (Lonza) as described in (Weatherly et al., 2018). Constructs used were YFP-PKCβII-YFP (a gift from Alexandra Newton; Addgene plasmid #14866; “PKCβII”; (Violin et al., 2003)), GFP-PKCδ -C1(2) (a gift from Tobias Meyer; Addgene plasmid # 21216; (Codazzi et al., 2001)), mRFP-MARCKS-ED (generously provided by Dr. Barbara Baird and Dr. David Holowka, Cornell University; “MARCKS”; (Gadi et al., 2011)), or PLD1-EGFP construct (generously provided by Dr. Michael Frohman of Stony Brook University and Dr. Shamshad Cockcroft of University College London; (Du et al., 2003; O’Luanaigh et al., 2002)). Regarding GFP-PKCδ-C1(2) (sometimes referred to herein as “PKCδ”), this short form of PKCδ, which only contains C1 (2) domains, has previously been employed to effectively investigate PKCδ translocation (Codazzi et al., 2001; Mogami et al., 2003). Both PKC constructs were cloned from R. norvegicus (rat) (Codazzi et al., 2001; Violin et al., 2003), and MARCKS-ED and PLD1 DNA were from human (Du et al., 2003; Gadi et al., 2011). The percent identities of PKCβ, PKCδ, ED domain of MARCKS, and PLD1, between human and rat, from pairwise alignments using NIH Blast, are 98%, 90%, 96%, and 87%, respectively.

Following electroporation, cells were plated (100,000 or 125,000 cells/well in 8-well ibidi plates) for overnight incubation in phenol red-free media (recipe is found in (Weatherly et al., 2018)), then sensitized with IgE, stimulated with Ag, and imaged via confocal microscopy as detailed in (Weatherly et al., 2018). For YFP-PKCβII-YFP, GFP-PKCδ-C1(2), and PLD1-EGFP, a 30 milliwatt multi-argon laser (515nm excitation for YFP and 488 nm excitation for GFP and EGFP, emission 505–605 nm bandpass filter) was used. For mRFP-MARCKS-ED, a 1 milliwatt HeNe-Green laser (543 nm excitation, 560–660 nm emission filter) was used. Image acquisition speed was 10 μs/pixel.

Images were then analyzed using NIH Fiji ImageJ software to examine individual transfected cells from each experiment. Only cells that appeared healthy (in DIC images), in focus, and fluorescent above background (autofluorescence) levels were utilized for analysis. To determine the “percentage translocation of transfected cells,” each transfected cell with movement of the fluorescent construct to (or, for mRFP-MARCKS-ED, away from) the plasma membrane at any time point during the 10 min post-Ag exposure video acquisition was noted, and the total percentage of transfected cells that underwent this movement was calculated. For only transfected cells that underwent translocation, the “time to first translocation” was defined as the time stamp of first image frame in which PKC moved to the plasma membrane, exhibiting a clear complete ring formation around the plasma membrane (in the case of mRFP-MARCKS-ED, the time stamp utilized was that of the first image frame showing movement of the construct away from the plasma membrane). As a control to verify triclosan’s ability to inhibit mast cell function under these experimental conditions, the percentage of membrane ruffling, of transfected cells only, was calculated: differential interference contrast images were collected along with fluorescence images, and construct-transfected cells undergoing classical membrane ruffling (Palmer et al., 2012) post Ag exposure were noted, as a percentage of all transfected cells, ± TCS.

Phospholipase D Activity Assay

To examine PLD activity, the Amplex® Red phospholipase D assay kit (Molecular Probes) (which measures activity of both isoforms PLD1 and PLD2 simultaneously) was utilized. The kit reagents were prepared as described in the manufacturer’s protocol with the exception of using Tyrode’s buffer in place of 1X Reaction Buffer.

RBL-2H3 cells (1.5 × 106 per well) were plated in tissue culture-treated, sterile 6-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) and incubated overnight (12–16 h) at 37 °C/5% CO2. On the second day, cells were sensitized with IgE, then washed with BT as described in the “Protein kinase C activity assay (ELISA)” section above. Cell samples were then exposed to either BT or Ag (0.1 or 0.001 μg/ mL), ± TCS or FIPI for 15 min at 37 °C. Immediately following this exposure, cells were placed on ice and washed with ice-cold PBS buffer. Triton-X 100 (Surfact-Amps X-100, 10%, low carbonyl and peroxide; Thermo; “TX”) was diluted to 0.2% TX in PBS (Lonza). After removing all traces of the wash buffer, this 0.2% Triton-X (TX) buffer was added to the cells (300 μL/well). Next, cells were harvested by cell scraper (Falcon) into microcentrifuge tubes on ice, thoroughly vortexed and underwent a freeze-thaw cycle using liquid nitrogen immersion for 30 seconds, followed by room temperature thawing. Lysed cells were then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,400xg at 4°C. Each sample’s supernatant (100 μL/well) was then transferred to a well within a black-side, clear-bottom, sterile 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One), in technical duplicates. Background fluorescence was measured by preparing control samples with 0.2% TX in PBS. The remaining steps were carried out according to the manufacturer’s directions. PLD activity was determined by measuring fluorescence intensity by microplate reader (Synergy 2; Biotek) at 530/25 nm excitation and 590/35 nm emission.

Raw data were processed by subtracting average background fluorescence (substrate and kit reagents in 0.2% TX-PBS with no cell supernatant) from each sample, and the background-subtracted duplicates were then averaged. These values were then normalized to the unstimulated (no Ag) control for each experimental day. The percent increase of PLD activity over control was determined by subtracting the normalized control value from the normalized Ag or Ag + TCS values and dividing this number by the control value.

The effect of TCS on the activity of purified PLD from Arachis hypogaea and Streptomyces chromofuscus was measured as described above, except these purified PLD preparations were used in place of supernatant from the cell lysates. Purified PLD from Streptomyces chromofuscus (Sigma), purchased as a glycerol stock (50,000 units/mL), was diluted to be 0.125 units/mL in 0.2% TX-PBS before being used in the assay. Purified PLD from Arachis hypogaea (Sigma) was purchased as a lyophilized powder and first reconstituted in Tyrode’s buffer to 500 units/mL and then further diluted in 0.2% TX-PBS to a final concentration to be 2.5 units/mL. Because the optimal temperature for Arachis hypogaea PLD is at 30°C, experiments with this PLD, which were carried out at 37°C in order to match the cellular experiments, were performed with extended exposure time with TCS: 1 hour, instead of 15 min.

Degranulation Assay

Degranulation was assayed via detection of β-hexosaminidase, a granule marker, as described in (Weatherly et al., 2013).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were done in Graphpad Prism. Numbers of technical replicates and independent days of experiments are noted each figure legend. Significance levels were assessed via one-tailed t-tests or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Results

We previously showed that, within a 60 minute co-exposure to TCS and antigen (Ag), non-cytotoxic TCS doses (5 μM and higher) inhibit RBL-2H3 mast cell degranulation elicited by a wide range of Ag doses (Palmer et al., 2012), including doses that elicit either minimal or maximal degranulation responses. Additionally, modest amounts of degranulation (~7% absolute degranulation) elicited by short 15 min exposures to low Ag doses are inhibited by TCS during as few as 15 min of co-exposure (Palmer et al., 2012). However, the higher levels of degranulation (~35% absolute degranulation) elicited by high Ag doses (0.005 and 0.1 μg/mL, used throughout much of this current manuscript) are not inhibited within the first 10 to 15 min of TCS exposure (data not shown) –even as degranulation is eventually and robustly inhibited by TCS within the full hour of co-exposure (Palmer et al., 2012). In this study, we have examined TCS effects on several of the biochemical events that lead to full degranulation within 60 min of Ag exposure in order to pinpoint the timing of the molecular mechanisms leading to TCS inhibition of mast cell degranulation.

Triclosan increases protein kinase C activity in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells.

PKC is a key signaling enzyme involved in mast cell degranulation (Gadi et al., 2011; Ludowyke et al., 1989; Ozawa, Szallasi, et al., 1993), and is activated by Ca2+ (Kang et al., 2007; Land et al., 2017; van Rossum et al., 2009) and by diacylglycerol (Ozawa, Yamada, et al., 1993; Steinberg, 2008). Because TCS decreases cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization (Weatherly et al., 2018), we hypothesized that TCS inhibits PKC activity, thereby inhibiting degranulation in mast cells. To probe this hypothesis, we utilized a PKC activity ELISA (Enzo life science) that measures the activity of eight PKC isoforms (α, βI, βII, γ, δ, ε, η, and θ) simultaneously. RBL-2H3 (RBL) mast cells were stimulated by 0.1μg/mL DNP-BSA Ag for 10 min, or by 0.005 μg/mL DNP-BSA Ag for 15, 30, and 45 minutes, with and without 10 μM TCS. A control (no Ag stimulation) was also prepared. The lysates from each of the cell samples were used in the PKC activity ELISA. These data were normalized by the total protein concentration values. Exposure of RBL cells to 0.1μg/ml Ag for 10 minutes causes a robust (~67%) increase in PKC activity over controls, as expected (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, TCS has no effect on the ability of Ag to stimulate PKC activity at this 10 min timepoint (Fig.1A). Because cytosolic Ca2+ levels are only inhibited by ~10% by TCS within the first 10 min of Ag co-exposure, next we hypothesized that later time points would reveal TCS inhibition of PKC activity due to the greater reduction in cytosolic Ca2+ (compared to Ag-only control) caused by TCS at 15 min (~20% inhibition) and 60 min (~50% inhibition) post-Ag stimulation (Weatherly et al., 2018). However, similar results were found in 15 and 30 min exposure experiments (Fig. S1), which showed robust Ag-stimulated increases in PKC activity that are, again, unaffected by TCS (Fig. S1A–B). Interestingly, there is a significant TCS-induced increase in Ag-stimulated PKC activity at the 45 min time point (Fig 1B).

Fig. 1.

TCS effects on PKC activity in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Cells were stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml Ag ± 10 μM TCS for 10 min (A) or with 0.005 μg/ml Ag ± 10 μM TCS for 45 min (B) in BT. After exposure, PKC activity was measured via ELISA, and absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Raw data were processed as described in the Methods section to normalize to both total protein concentration and to unstimulated controls, in order to calculate percentage increase of PKC activity over unstimulated control. Data presented are means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments; duplicates per treatment per experiment. Statistically significant results, comparing Ag-stimulated cells ± TCS exposure, are represented by * p < 0.05, determined by one-tailed t-test.

Triclosan delays PKCβII and PKCδ translocation to plasma membrane in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells

Because the ELISA assay of PKC activation simultaneously measures eight PKC isoforms (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that potential TCS inhibition of key isoforms essential for degranulation may be masked by that measurement method. Previous studies have reported that PKC β and PKC δ isoforms are particularly important for mast cell degranulation (Cho et al., 2004; Nechushtan et al., 2000), so we investigated the activation of those individual key isoforms by monitoring their translocation using confocal microscopy. PKC translocation, to the plasma membrane, is known to be a hallmark of its activation (Mochly-Rosen et al., 1990). Thus, we utilized YFP-PKC βII-YFP and PKC δ C1 (2)-EGFP plasmids and transfected them via electroporation into RBL-2H3 mast cells, for transient expression. The translocation of PKC in real time in live cells over the course of 10 minutes was imaged by confocal microscopy.

In unstimulated RBL mast cells, the majority of PKC βII and PKC δ are located in the cytosol (as shown in representative still frame images from the videos; “Control [No Ag]” columns in Fig. 2A, 3A). Antigen (0.005μg/mL) stimulation causes both PKC isoforms to translocate rapidly to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A, 2C, 3A, 3C). While addition of Ag+10 μM TCS does not affect the overall spatial translocation to the plasma membrane compared to Ag-alone (Fig. 2A–B, 3A–B), temporal translocations of both PKC βII and PKC δ are delayed significantly by TCS (Fig. 2C, 3C, Table 1). Analyses of individual cells revealed that about two-thirds of transfected cells expressing PKC βII and nearly all cells expressing PKC δ undergo PKC translocation to the plasma membrane within 10 min of Ag stimulation, regardless of TCS exposure (Fig. 2B, 3B). Also in both PKC βII- and PKC δ-transfected cells, following the first rapid translocation to the plasma membrane, periodic oscillations of PKC translocation between the plasma membrane and the cytosol were observed in Ag-stimulated cells, and were unaffected by TCS exposure (data not shown); these oscillations were previously documented for PKC βI in RBL cells (Gadi et al., 2011). However, the average time for PKC to translocate to the plasma membrane for the first time is increased significantly by TCS: a delay of about 80 sec for both PKC βII and PKC δ) (Fig. 2C, 3C, Table 1).

Fig. 2.

TCS effects on PKC βII translocation to the plasma membrane in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. RBL cells were transfected with the YFP-PKC βII-YFP plasmid. Live cell time-lapse images were taken for 10 min immediately after addition of 0.005 μg/ml Ag or 0.005 μg/ml Ag + 10 μM TCS in the cells by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Representative images per group, pre-exposure and post-exposure, immediately following first translocation (at ~170–250 sec post-Ag), are shown in (A). Scale bar, 10 μm. As described in Methods, the percentage of transfected cells with PKC βII that translocated from the cytosol to the plasma membrane within 10 min post addition of Ag ± 10 μM TCS are plotted in (B); first time of this translocation is plotted in (C). As a control showing cellular inhibition by TCS, the percentage of transfected cells undergoing membrane ruffling within 10 min (D) was calculated using Fiji image J. For (B-D), values presented are derived from analysis of N= 43 for Ag-only cells and N=50 for Ag + 10 μM TCS cells. Percentage translocation and percentage ruffling values in (B) and (D) are from six independent days of imaging, ± SEM. Translocation time values in (C) are averages over the 43 (Ag) and 50 (Ag + 10 μM TCS) cells, ± SEM. Statistically significant results, , comparing Ag-stimulated cells ± TCS exposure, are represented by * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, determined by one-tailed t-test.

Fig. 3.

TCS effects on PKC δ C1 (2) translocation to the plasma membrane in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. RBL cells were transfected with the PKC δ C1 (2)-EGFP plasmid. Live cell time-lapse images were taken for 10 min immediately after addition of 0.005 μg/ml Ag or 0.005 μg/ml Ag + 10 μM TCS in the cells by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Representative images per group, pre-exposure and post-exposure, immediately following first translocation (at ~170–250 sec post-Ag), are shown in (A). Scale bar, 5 μm. As described in Methods, the percentage of transfected cells with PKC δ C1 (2) that translocated from the cytosol to the plasma membrane within 10 min post addition of Ag ± 10 μM TCS are plotted in (B); first time of this translocation is plotted in (C). As a control showing cellular inhibition by TCS, the percentage of transfected cells undergoing membrane ruffling within 10 min (D) was calculated using Fiji image J. For (B-D), values presented are derived from analysis of N= 29 for Ag-only cells and N=47 for Ag + 10 μM TCS cells. Percentage translocation and percentage ruffling values in (B) and (D) are from five independent days of imaging, ± SEM. Translocation time values in (C) are averages over the 29 (Ag) and 47 (Ag + 10 μM TCS) cells, ± SEM. Statistically significant results, comparing Ag-stimulated cells ± TCS exposure, are represented by ** p<0.01, determined by one-tailed t-test.

Table 1.

Average time of first translocation of transfected cells

| Sample | Ag exposure (sec) | # of cells (N) | Ag+ 10μM TCS exposure (sec) | # of cells (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKC βII-YFP | 170 ± 20 | 43 | 250 ± 20 | 50 |

| PKC δ (C1)-EGFP | 160 ± 20 | 29 | 240 ± 20 | 47 |

| mRFP-MARCKS-ED | 170 ± 20 | 80 | 240 ± 30 | 45 |

To verify that TCS does, indeed, inhibit mast cell function under these experimental conditions (10 min of imaging of individual PKC-transfected, Ag-stimulated RBLs), we utilized the previously-shown TCS inhibitory effect on mast cell ruffling (Palmer et al., 2012). We analyzed the percentage PKC-transfected cells that underwent cytoskeleton ruffling within 10 min of Ag addition, ± TCS, which showed both the expected robust stimulation of membrane ruffling by Ag and triclosan’s inhibition (Fig. 2D, 3D). This ruffling analysis (Fig. 2D, 3D) also serves as a control showing that overexpression of the PKC constructs does not interfere with triclosan’s ability to inhibit mast cell signaling. Additionally, to further rule out unwanted effects of overexpression of PKC by transfection in RBLs, we measured the degranulation as described in (Weatherly et al., 2013), of PKC-transfected, Ag-stimulated RBLs, ± TCS. Exogenous overexpression of either PKC βII or PKC δ did not affect levels of mast cell degranulation compared to untransfected cells, and TCS inhibition of degranulation was, likewise, unaffected in these transfected cells (data not shown). Together, these controls confirm the validity of these transfection/confocal experiments for assessing TCS toxicity in mast cells.

Triclosan delays MARCKS translocation to the cytosol in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells

In order to directly assess whether PKC activity is affected by TCS in individual, living RBL cells, we assessed TCS effects on MARCKS. MARCKS is one of the most abundant substrates for PKC in mast cells (Blackshear, 1993; Gadi et al., 2011). In resting cells, MARCKS is held at the plasma membrane via specific electrostatic interactions with membrane phospholipids at its basic effector domain (ED) domain. Upon Ag stimulation, serine residues within the ED domain are phosphorylated by translocated PKC, resulting in MARCKS dissociation from the plasma membrane (Graff et al., 1989; Graff et al., 1989b). Thus, to determine whether TCS affects PKC kinase activity on its MARCKS substrate, we transfected the fluorescent construct mRFP-MARCKS-ED into RBL mast cells and monitored its translocation by confocal microscopy.

Upon Ag (0.005μg/mL) stimulation, mRFP-MARCKS-ED dissociates from the plasma membrane and moves into the cytoplasm (Fig. 4A). TCS (10μM) does not affect the overall ability of mRFP-MARCKS-ED to translocate to the cytosol (Fig 4A, 4B). Thus, these results indicate that overall PKC kinase activity is not hindered by TCS, in agreement with Fig. 1A and Fig. S1. Also, oscillatory behavior in which mRFP-MARCKS-ED dissociates from and re-associates with the plasma membrane in Ag-stimulated mast cells (Gadi et al., 2011) was observed, and the periodicity of mRFP-MARCKS-ED oscillations is not altered by TCS exposure (data not shown). We analyzed the percentage MARCKS-transfected cells that underwent cytoskeleton ruffling within 10 min of Ag addition, ± TCS, which showed both the expected robust stimulation of membrane ruffling by Ag and triclosan’s inhibition (Fig. 4D). This ruffling analysis (Fig. 4D) also serves as a control showing that overexpression of the MARCKS constructs does not interfere with triclosan’s ability to inhibit mast cell signaling.

Fig. 4.

TCS effects on MARCKS translocation to the cytosol in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. RBL cells were transfected with the mRFP-MARCKS-ED plasmid. Live cell time-lapse images were taken for 10 min immediately after addition of 0.005 μg/ml Ag or 0.005 μg/ml Ag + 10 μM TCS in the cells by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Representative images per group, pre-exposure and post-exposure, immediately following first translocation (at ~170–250 sec post-Ag), are shown in (A). Scale bar, 5 μm. As described in Methods, the percentage of transfected cells with MARCKS that translocated to the cytosol within 10 min post addition of Ag ± 10 μM TCS are plotted in (B); first time of this translocation is plotted in (C). As a control showing cellular inhibition by TCS, the percentage of transfected cells undergoing membrane ruffling within 10 min (D) was calculated using Fiji image J. For (B-D), values presented are derived from analysis of N= 80 for Ag-only cells and N=45 for Ag + 10 μM TCS cells. Percentage translocation and percentage ruffling values in (B) and (D) are from three independent days of imaging, ± SEM. Translocation time values in (C) are averages over the 80 (Ag) and 45 (Ag + 10 μM TCS) cells, ± SEM. Statistically significant results, comparing Ag-stimulated cells ± TCS exposure, are represented by ** p<0.01, determined by one-tailed t-test.

Further analyses of individual MARCKS-transfected, Ag-stimulated RBL cells revealed that TCS causes a defect in MARCKS signaling by delaying MARCKS dissociation from the plasma membrane (by about 70 sec) (Fig 4C, Table 1).

Triclosan and FIPI, a PLD inhibitor, decrease PLD activity in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells

Cytosolic Ca2+ and PKC translocation work in tandem to activate phospholipase D (PLD) (Lin & Gilfillan, 1992), which is another key player in the mast cell signaling pathway leading to degranulation (Chahdi et al., 2002). To examine whether TCS affects PLD activity, we utilized the fluorescence-based Amplex® Red phospholipase D assay kit, which measures the activity of both PLD1 and PLD2 isoforms at the same time. First, we performed Ag-dose response assays measuring PLD activity by the Amplex® kit (data not shown). From these dose responses, we chose two Ag doses, 0.1μg/mL and 0.001μg/mL, which both produced robust activation of PLD activity, for further cellular PLD activity experiments with TCS exposure.

With 0.1μg/mL Ag stimulation for 15 min, PLD activity is increased ~30% over the basal level in unstimulated control cells (Fig. 5A). This Ag-stimulated PLD activity is inhibited (decrease by ~50%) by 10μM TCS (Fig. 5A). A similar level of PLD inhibition was observed in cells stimulated by 0.001μg/mL Ag (data not shown). These inhibitory effects of TCS on PLD activity were only observed in Ag-stimulated mast cells, not in resting RBL cells (data not shown). As a control, degranulation was also measured under the same experimental conditions used for these cellular PLD assays: modest degranulation responses were stimulated by Ag (0.1μg/mL and 0.001μg/mL) and were inhibited by TCS within the 15 min timeframe of these experiments (data not shown). We also confirmed that triclosan’s inhibition of PLD activity is a true cellular effect and is not due to TCS interference with the components of the Amplex® kit (Fig. S2).

Fig. 5.

TCS effects on PLD activity in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Cells were stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml Ag ± 10 μM TCS for 15 min (A) or with 0.1 μg/ml Ag ± 75 nM FIPI for 15 min (B) in BT. After exposure, PLD activity was measured via Amplex® Red kit, and fluorescence was read using a microplate reader. Raw data were processed as described in the Methods section to normalize to unstimulated controls, in order to calculate percentage increase of PLD activity over unstimulated control. Data presented are means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments; triplicates per treatment per experiment. Statistically significant results, comparing Ag-stimulated cells ± TCS or FIPI exposure, are represented by * p < 0.05, determined by one-tailed t-test. (C) Degranulation was measured described in (Weatherly et al., 2013) after cells were exposed to 0.1μg/ml Ag ± FIPI, for 1 hour. Spontaneous represents control cells that are not exposed to either antigen or FIPI. Values were then normalized to 0.1μg/ml Ag+ 0 nM FIPI. Data presented are means ±SEM of five independent experiments; three replicates per experiment. No significance among FIPI exposures was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

In another control experiment, we employed a known direct PLD inhibitor, FIPI, which irreversibly binds to the HKD (histidine, lysine, aspartic acid) domain in the catalytic site of PLD and inhibits both the PLD1 and the PLD2 isoforms (Su, Yeku, et al., 2009). As expected, Ag-stimulated PLD activity is strongly inhibited by 75 nM FIPI (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, inhibition of PLD activity by 75 nM FIPI, and even higher doses of FIPI at 150 nM, did not lead to inhibition of degranulation (Fig. 5C), in agreement with a study done by Yanase et al. (Yanase et al., 2009).

Triclosan does not significantly affect PLD1 translocation to the plasma membrane in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells

Previous studies have shown that the PLD1 isoform, not PLD2, translocates toward the plasma membrane upon activation (F. D. Brown et al., 1998). Also, while activity of both PLD isoforms is measured simultaneously by the Amplex® kit, recent literature suggests that only the PLD1 isoform is positive regulator of degranulation (Zhu et al., 2015). Thus, we next performed real-time fluorescence imaging of PLD1-EGFP translocation to detect the spatiotemporal changes of PLD1 after co-exposure of Ag and TCS.

Upon Ag (0.1 μg/mL) stimulation, PLD1-EGFP translocates gradually to the plasma membrane, with variable onset times of ~2 to 10 minutes following Ag addition (Fig. 6A)—in contrast to the rapid and complete translocation patterns exhibited in the PKCβII, PKCδ, and MARCKS translocations. Further analyses showed that even though co-exposure of Ag with TCS appears to modestly decrease PLD1 translocation toward the plasma membrane, the effect is not statistically significant (Fig. 6A–B). No oscillatory behavior of PLD1-EGFP movement was displayed: PLD1 stayed at or near the plasma membrane once translocated, at least within the 10–15 min imaging period. As in Figures 2–4, we again analyzed the percentage PLD1-EGFP-transfected cells that underwent cytoskeleton ruffling within 10 min of Ag addition, ± TCS, which showed both the expected robust stimulation of membrane ruffling by Ag and triclosan’s inhibition of it (Fig. 6C). This ruffling analysis (Fig. 6C) shows that overexpression of the PLD1-EGFP construct does not interfere with triclosan’s ability to inhibit mast cell signaling.

Fig. 6.

TCS effects on PLD1 translocation toward the plasma membrane in Ag-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. RBL cells were transfected with the EGFP- PLD1 construct. Live cell time-lapse images were taken for 10 min immediately after addition of 0.1μg/ml Ag or 0.1μg/ml Ag + 10 μM TCS in the cells by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Representative images per group, pre-exposure and at ~8 min post-exposure are shown in (A). Scale bar, 5 μm. As described in Methods, the percentage of transfected cells with PLD1 that translocated toward the plasma membrane within 10 min post addition of Ag ± 10 μM TCS are plotted in (B). As a control showing cellular inhibition by TCS, the percentage of transfected cells undergoing membrane ruffling within 10 min (C) was calculated using Fiji image J. For (B and C), values presented are derived from analysis of four independent days of imaging, with 4–13 cells analyzed per treatment per day, with error shown as SEM. Statistically significant results, comparing Ag-stimulated cells ± TCS exposure, are represented by ** p<0.05, determined by one-tailed t-test.

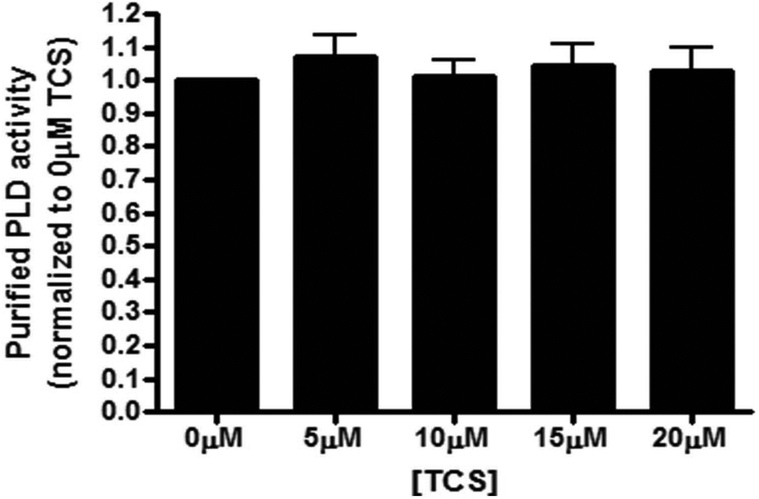

TCS does not directly inhibit PLD activity

To determine whether TCS directly binds to and inhibits PLD activity, we used purified PLD from Arachis hypogaea (peanut), which contains two HKD domains, similar to those found in mammalian PLD isoforms (B. Z. Guo et al., 2006). Purified PLD was prepared in buffer conditions that mimic our cell-based PLD activity assays and then was exposed to varying concentrations of TCS (0 – 20 μM). There was no effect of TCS on PLD from Arachis hypogaea (Fig. 7), suggesting the triclosan’s inhibition of mammalian PLD activity (Fig. 5A) may not be due to direct binding of TCS to PLD. Various experiments testing different incubation temperatures (30°C, optimal for Arachis hypogaea PLD or 37°C, as used in mast cell experiments) and times (30 min or 1 hour) and 0–20 μM TCS all yielded robust Arachis hypogaea PLD activity, unaffected by TCS (data not shown). A similar lack of direct TCS effect on PLD activity was found in experiments using a different purified PLD, from Streptomyces chromofuscus (Fig. S3).

Fig. 7.

TCS effects on purified PLD from Arachis hypogaea. PLD activity was measured using the Amplex® Red PLD assay kit after incubating purified Arachis hypogaea PLD with 0 to 20 μM TCS for 1 hour. Values were normalized to the control (0μM TCS) and presented as means ± SEM of three independent days of experiments; with triplicates per treatment per experiment. No significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Comparison of triclosan’s and sucralose’s effects on mast cell degranulation

We assayed degranulation upon co-exposure of Ag with sucralose (main ingredient in Splenda®) which bears some structural similarity to TCS (Fig. S4). We found that sucralose, at doses relevant to human exposure, does not affect degranulation, at least during the one hour time frame assessed (Fig. S4).

Discussion

In this investigation of the biochemical mechanisms underlying triclosan disruption of mast cell signaling, we have revealed triclosan’s effects on activity and on spatial and temporal subcellular localization of crucial signaling molecules. We have found that a key mechanism by which TCS inhibits mast cell degranulation is triclosan’s inhibition of PLD activity. Surprisingly, TCS does not dampen PKC activity (measured either via ELISA or via PKC substrate MARCKS translocation). This PKC result is an important red flag for the field of predictive toxicology because it makes clear that enzymes and other signaling molecules that depend on cytosolic Ca2+ are not necessary inhibited when cytosolic Ca2+ levels are decreased by a toxicant or drug.

This study also reveals the importance of timing when chemical effects are assayed on a signal transduction pathway. We found that, although TCS surprisingly does not inhibit Ag-stimulated PKC activity, TCS delays the translocations of PKC isoforms βII and δ to the plasma membrane and dissociation of the PKC substrate MARCKS from the plasma membrane (events which occur during the 10 min period following Ag stimulation). However, these PKC isoforms and substrate do (eventually) translocate and display oscillatory movement in the presence of TCS, suggesting that their activity is not the major target of TCS in its inhibition of mast cell function. Conversely, TCS inhibits Ag-stimulated PLD activity by 15 min post Ag stimulation but does not grossly hinder translocation of PLD1 toward the plasma membrane, movement which largely occurs within the first 10 min post Ag. Of interest, a previous study also found that inhibition of PLD activity (via primary alcohol treatment) suppresses mast cell degranulation but does not affect translocation of PLD1 (F. D. Brown et al., 1998).

An overarching finding of this mechanistic investigation of TCS degranulation suppression is that, during the first ~10 min following Ag stimulation, several of the major early biochemical events are not significantly inhibited by TCS (Figs. 1, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4A, 4B), despite strong TCS inhibition of degranulation within 1 hour (Weatherly et al., 2013). Originally, we had hypothesized that PKC activity (measured by ELISA, Fig. 1 and by translocation of its substrate MARCKS, Fig. 4) would be inhibited because TCS reduces the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration following Ag stimulation (Weatherly et al., 2018). A PKC isoform key to mast cell degranulation (Yanase et al., 2011), βII, contains a C2 domain (Blobe et al., 1996) responsible for modulating Ca2+-responsive activation of the enzyme. However, a previous study showed that TCS actually increases efflux of Ca2+ out of the endoplasmic reticulum (and into the cytosol) within the first 3 min post-Ag and increases influx of Ca2+ into the mitochondria within the first 4 min post-Ag (Weatherly et al., 2018): changes that promote degranulation. Additionally, we previously showed that intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are enhanced by TCS by 45 min post Ag exposure (Weatherly et al., 2018) — another TCS effect that is actually supportive of degranulation because ROS activates degranulation (Swindle et al., 2004). Reduction in the level of Ca2+ within the cytosol (the cellular compartment that contains PKC) does not occur until at least 10 min post Ag exposure (Weatherly et al., 2018) and does not reach ~20% inhibition (area under the curve) until 15 min (and ~50% inhibition until 1 hour) (Weatherly et al., 2018). Thus, even though PKC activity is robustly stimulated by Ag within 10 min, it is unaffected by TCS (Fig. 1A), likely both due to the longer time frame required (>10 min) for TCS to robustly inhibit cytosolic Ca2+ (Weatherly et al., 2018) and due to triclosan’s stimulation of ROS (Weatherly et al., 2018) leading actually to stimulation of ROS-activated PKC isoforms such as PKCδ (Cho et al., 2004; H. G. Lee & Yang, 2010; Yoshida, 2007) (Fig. 1B). Table 2 summarizes TCS effects on biochemical events in the mast cell degranulation pathway and their timing.

Table 2.

Triclosan effects on mast cell degranulation pathway: Time to first signaling defect, following co-exposure to Ag+ TCS

| Signaling Event* | TCS Effect on this event** | Time of first defect caused by TCS*** | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux of Ca2+ from ER | 3 min | (Weatherly et al., 2018) | |

| Influx of Ca2+ into mitochondria | 4 min | (Weatherly et al., 2018) | |

| Mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations | 10 min | (Weatherly et al., 2018) | |

| Influx of Ca2+ into cytosol | 10 min (~10% 15 min (~20% 1 hr (~50% |

(Weatherly et al., 2018) | |

| PKC βII and PKCδ translocation | Delay | Delayed from ~2.7 min (-TCS, + Ag) to ~4.2 min (+ TCS, +Ag) | Fig. 2C & 3C |

| PKC activity | 45 min | Fig. 1B | |

| MARCKS translocation | Delay | Delayed from ~2.8 min (-TCS, + Ag) to ~4 min (+ TCS, +Ag) | Fig. 4C |

| Actin cytoskeleton ruffling | 10 min | Fig. 2D, 3D, 4D, & 6C | |

| PLD1 translocation | Slight inhibition | 10 min | Fig. 6 |

| PLD activity | 15 min | Fig. 5A | |

| Microtubule polymerization | 15 min | (Weatherly et al., 2018) | |

| ROS formation | ~45 min | (Weatherly et al., 2018) |

Ag concentration used: 0.005 −0.1μg/mL. These doses caused roughly maximal degranulation in absence of TCS.

Items in red indicate mechanisms of TCS inhibition of degranulation.

TCS concentration used: 10–20μM

These data support the conclusion that PKC can still do its job (translocate to the plasma membrane, oscillate between the cytosol and plasma membrane, actively process its substrate MARCKS) during the first ~10 min of Ag and TCS co-exposure—even while the delays in PKC (from ~2.7 to 4.2 min) and MARCKS (from ~2.8 to 4 min) movement are early indicators of problems to come. The major disruptive events caused by TCS do not commence until ~15 min, including ~20% decrease in integrated cytosolic Ca2+ level (Weatherly et al., 2018), significantly inhibited PLD activity (Fig. 5A), and disruption in microtubule formation (Weatherly et al., 2018): defects which are key to inhibiting degranulation. Even though PLD activity is inhibited by TCS by 15 min post Ag, translocation of PLD1 is not grossly hindered, likely because its movement toward the plasma membrane begins within ~2 min post-Ag and has occurred to a large degree with the first 10 min. However, after PLD has been largely re-located to or near the plasma membrane, its activity is inhibited (Fig. 5A). Taken together, these PKC and PLD studies strongly suggest that a significant accumulated decrease in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which does not occur until ~15 min post-Ag (Weatherly et al., 2018), along with PLD inhibition (Fig. 5A), are the key events leading to inhibition of degranulation. Below we discuss how dampened cytosolic Ca2+ could cause the inhibitory events cited in Table 2 (red arrows: translocation delays, decreased PLD activity, and inhibited microtubule polymerization).

Sucralose, the active ingredient in artificial sweetener Splenda®, is another chemical comprised of two carbon rings combined in ether linkage and decorated with a total of three chlorines. However, unlike TCS, sucralose does not affect degranulation, indicating that presence of the three chlorines on the two ether-linked rings is insufficient to affect mast cell function, at least during the one hour time frame assessed (Fig. S4). This result lends further support to the hypothesis that the proton ionophore nature of TCS is the key structural determinant of its modulation of mast cells (Weatherly et al., 2016).

One potential mechanism underlying TCS inhibition of cytosolic Ca2+ is that TCS could inhibit the early phosphorylation cascade that leads to PLCγ activation. PLCγ inhibition would lead to decreases in both DAG and IP3 generation, which would subsequently result in hindered IP3-mediated ER Ca2+ release. However, TCS does the opposite: Ag-stimulated ER Ca2+ release is actually enhanced by TCS with Ag (Weatherly et al., 2018), and this result strongly suggests that biochemical events upstream of ER Ca2+ mobilization are uninhibited by TCS—hence our focus on effectors of Ca2+ influx, PKC and PLD, in this study.

Delays in PKC translocation caused by TCS may be due to attenuation of microtubule polymerization by TCS (Weatherly et al., 2018) at early time points after Ag stimulation. In CHO cells, microtubule integrity is required for translocation of PKC δ, in a complex with cytoskeletal protein Annexin V (Kheifets et al., 2006). Though drastic TCS inhibition of microtubule polymerization was documented at 15 min post Ag in (Weatherly et al., 2018), and that time point was chosen for its unambiguous TCS effects, defects in microtubule formation may potentially begin to accumulate at earlier time points and may thereby explain slowed PKC translocation. TCS may inhibit microtubule polymerization via its depression of cytosolic Ca2+: Ag-stimulated elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels stimulates the association of the positive regulator protein GIT1 with tubulin, in turn leading to enhanced microtubule polymerization and degranulation (Sulimenko et al., 2015).

PKC βII phosphorylates myosin and also binds actin in mast cells (Ludowyke et al., 2006). Myosin phosphorylation is thought important for degranulation (O. H. Choi et al., 1994; Ludowyke et al., 1989). Moreover, the C2-like domain of PKC δ binds to F-actin to regulate actin redistribution in neutrophils (Lopez-Lluch et al., 2001) as well as in airway epithelial cells (Smallwood et al., 2005). Thus, TCS inhibition of actin polymerization (Palmer et al., 2012), as shown by inhibition of membrane ruffling (Figs. 2D, 3D, 4D, and 6C), could be another explanation of triclosan’s delay of PKC movement to the plasma membrane.

PLD plays important roles in mast cell degranulation (F. D. Brown et al., 1998; Cissel et al., 1998; Way et al., 2000), and its Ag-stimulated activity is inhibited by TCS (Fig. 5A). Transient expression PLD experiments in RBL-2H3 cells show both isoforms are activated by Ag stimulation (Chahdi et al., 2002; O’Luanaigh et al., 2002). In mast cells, PLD1 is associated with granule membranes while PLD2 with the plasma membrane (F. D. Brown et al., 1998; W. S. Choi et al., 2002). PLD1 has low basal activity, and its activation requires interactions with PKC and/or small GTPases such as ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) and Rho family members (Liscovitch et al., 2000; X. Peng et al., 2012). PLD1 is stimulated in vitro and in vivo directly by Ca2+-dependent cPKC isoforms (PKCα and β) (Hammond et al., 1997; Kim et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1999) in a PIP2-dependent manner (Bae et al., 1998; Hammond et al., 1995; Rumenapp et al., 1995). In contrast, PLD2 is constitutively active and is more dependent on the presence of PIP2 than other activators (Lopez et al., 1998; Sung et al., 1999). Background studies of basal PLD activity showed that TCS has no effect on constitutive PLD activity (data not shown), even as TCS strongly inhibits Ag-stimulated PLD activity (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that constitutively-active PLD2 is less of a target of TCS than is PLD1, due to PLD1’s low basal activity and high activation potential.

FIPI, a potent dual inhibitor for PLD1 and 2, was employed in our study as a comparison to triclosan’s inhibitory action on PLD activity and on degranulation. FIPI irreversibly binds to a serine residue within the HKD (histidine, lysine, aspartic acid) domain in the catalytic site of PLD, preventing the cleavage of phosphatidylcholine, thus blocking PA production (Su, Yeku, et al., 2009). While we observed decreased PLD activity by FIPI (Fig. 5B), to our surprise, FIPI’s inhibition of both PLD isoforms had no effect on overall degranulation in Ag-stimulated mast cells (Fig. 5C). Currently there is some controversy about the role of PLD1 and 2 in mast cells. It has been long believed that both PLD1 and 2 play a positive role in mast cell degranulation, in that PLD1 is involved in the granule transport to the plasma membrane (Chahdi et al., 2002; Hitomi et al., 2004; Z. Peng & Beaven, 2005) and PLD2 is a fusogenic protein for granule’s docking and fusion to the plasma membrane (Chahdi et al., 2002; W. S. Choi et al., 2002; J. H. Lee et al., 2006; C. M. Marchini-Alves et al., 2012). However, an intriguing recent study using PLD1- and PLD2- knockout mice found that PLD1 positively regulates degranulation, while PLD2 is a negative regulator (Zhu et al., 2015). RhoA, which is directly affected by Ca2+ (though does not directly bind Ca2+), interacts with PLD2 to play a negative role in microtubule formation. The authors also showed that mast cells isolated from double knockout mice (PLD1−/− and PLD2−/−) exhibited normal degranulation compared to the control (Zhu et al., 2015), suggesting that PLD1 (positive) and PLD2 (negative) may effectively cancel out each other’s roles in regulating degranulation. Another recent study from this group demonstrates the importance of PLD1, but not PLD2, in T cell activation (Zhu et al., 2018). Thus, our study using FIPI agrees with this finding that equally impeding the two PLD isoforms simultaneously yields no change in degranulation. Taken together with our results showing a lack of TCS effect on basal PLD activity, these findings provide further credence to the idea that triclosan’s inhibitory action on PLD activity is targeted to PLD1, which is a positive regulator in degranulation--such that decreased PLD activity by TCS results in decreased degranulation.

Our study with purified PLD protein in vitro suggests that TCS does not directly bind to and inhibit activity of PLD (Fig. 7); thus, PLD activity is more likely indirectly inhibited by TCS-induced decreases in cytosolic Ca2+ level. The PLD used in this study was derived from Arachis hypogaea and has an HKD domain which contains a serine residue and which is highly homologous to the HKD domains found in rat and human PLD1 and PLD2 proteins. Even though PLD does not directly interact with Ca2+, the activities of its activation cofactors, such as small GTPase proteins, PKC, and PIP2, are dependent on Ca2+ signaling (Wakelam et al., 1997). Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that degranulation requires activation of PLD accompanied by sustained cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Chahdi et al., 2002; Cissel et al., 1998; Lin & Gilfillan, 1992; Ozawa, Szallasi, et al., 1993). Thus, the data suggest that PLD activity and, hence, degranulation, is inhibited by triclosan’s inhibition of Ca2+ influx into the cytosol.

The role of PLD has been implicated in various essential cellular functions in various cell types: signal transduction in embryonic kidney cells (Fang et al., 2001), cell migration in breast cancer cells (Hui et al., 2006), membrane vesicular trafficking (Du et al., 2003) and cytoskeletal reorganization (Colley et al., 1997) in fibroblasts, autophagy (Dall’Armi et al., 2010) in cervical cancer cells, and viral infections (Oguin et al., 2014) in alveolar basal epithelial cells. Due to these diverse roles of PLD in biology, PLD is involved in numerous physiological and disease states, including cancer (Su, Chen, et al., 2009), neurodegenerative disorders (Cai et al., 2006), cardiovascular problems (Chiang, 1994), and infectious diseases (Taylor et al., 2015). Therefore, inhibition of PLD by TCS might affect these different health problems.

In conclusion, we have elucidated biochemical mechanisms underlying inhibition of mast cell function by TCS, at dosages relevant to human exposure, by interrogating the activity and localization of key signaling enzymes. Combined with our previous findings on triclosan’s effects on calcium mobilization and microtubules, these results provide the temporal details of TCS-induced defects in PKC and PLD signaling steps, which lead to degranulation inhibition. In addition to TCS inhibition of mast cells, any cell type that depends on PLD function may be inhibited by TCS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Drs. David Holowka and Barbara Baird for the RBL-2H3 cells, mRFP-MARCKS-ED construct, and very helpful discussions; Dr. Michael Frohman and Yelena Altshuller at Stony Brook University and Dr. Shamshad Cockcroft at University College London for the PLD1-EGFP construct; Dr. Carol Kim for use of the Amaxa Nucleofector equipment; Dr. Robert Wheeler and Allison Scherer for use of the ibidi heating system; Saige McGinnis for contributions to the purified PLD activity studies; and Bailey West, Grace Bagley, and Bridget Konitzer for help with laboratory equipment and maintenance.

Disclaimer: This research was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institute of Health under the Award Number R15ES24593. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Funding information: This research was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH), Award Number R15ES24593, by the Radke Research Fellowship (University of Maine), and by an Institutional Developmental Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH) under grant number P20GM103423. J.K.S. and L.M.W. were supported in part by the Michael J. Eckardt Dissertation Fellowship (University of Maine).

Glossary of abbreviations

- Ag

antigen

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- BT

Tyrodes-bovine serum albumin

- CRAC

Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- DNP

2,4-dinitrophenol

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FIPI

5-Fluoro-2-indolyl des-chlorohalopemide

- IgE

immunoglobulin E

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- MARCKS

myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate

- Mast cell

MC

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PLD

phospholipase D

- RBL

rat basophilic leukemia cells, clone 2H3

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SERCA

sarco/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase

- SOCE

store-operated calcium entry

- TCS

triclosan

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abramson J, & Pecht I (2007). Regulation of the mast cell response to the type 1 Fc epsilon receptor. Immunological reviews, 217, 231–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderem A (1992). The MARCKS brothers: a family of protein kinase C substrates. Cell, 71(5), 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn KC, Zhao B, Chen J, Cherednichenko G, Sanmarti E, Denison MS, … Hammock BD (2008). In vitro biologic activities of the antimicrobials triclocarban, its analogs, and triclosan in bioassay screens: receptor-based bioassay screens. Environ Health Perspect, 116(9), 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajao C, Andersson MA, Teplova VV, Nagy S, Gahmberg CG, Andersson LC, … Salkinoja-Salonen M (2015). Mitochondrial toxicity of triclosan on mammalian cells. Toxicol Rep, 2, 624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaleh NB, Persaud I, & Brown JM (2016). Silver Nanoparticle-Directed Mast Cell Degranulation Is Mediated through Calcium and PI3K Signaling Independent of the High Affinity IgE Receptor. PLoS One, 11(12), e0167366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae CD, Min DS, Fleming IN, & Exton JH (1998). Determination of interaction sites on the small G protein RhoA for phospholipase D. J Biol Chem, 273(19), 11596–11604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassare JJ, Henderson PA, Burns D, Loomis C, & Fisher GJ (1992). Translocation of protein kinase C isozymes in thrombin-stimulated human platelets. Correlation with 1,2-diacylglycerol levels. J Biol Chem, 267(22), 15585–15590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baram D, Adachi R, Medalia O, Tuvim M, Dickey BF, Mekori YA, & Sagi-Eisenberg R (1999). Synaptotagmin II negatively regulates Ca2+-triggered exocytosis of lysosomes in mast cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 189(10), 1649–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ (1993). Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature, 361(6410), 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshear PJ (1993). The MARCKS family of cellular protein kinase C substrates. J Biol Chem, 268(3), 1501–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank U, Cyprien B, Martin-Verdeaux S, Paumet F, Pombo I, Rivera J, … Varin-Blank N (2002). SNAREs and associated regulators in the control of exocytosis in the RBL-2H3 mast cell line. Molecular Immunology, 38(16–18), 1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00085-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobe GC, Stribling DS, Fabbro D, Stabel S, & Hannun YA (1996). Protein kinase C beta II specifically binds to and is activated by F-actin. J Biol Chem, 271(26), 15823–15830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown FD, Thompson N, Saqib KM, Clark JM, Powner D, Thompson NT, … Wakelam MJ (1998). Phospholipase D1 localises to secretory granules and lysosomes and is plasma-membrane translocated on cellular stimulation. Curr Biol, 8(14), 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC, & Kholodenko BN (1999). Spatial gradients of cellular phospho-proteins. FEBS Lett, 457(3), 452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Zhong M, Wang R, Netzer WJ, Shields D, Zheng H, … Greengard P (2006). Phospholipase D1 corrects impaired betaAPP trafficking and neurite outgrowth in familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin-1 mutant neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103(6), 1936–1940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510710103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahdi A, Choi WS, Kim YM, Fraundorfer PF, & Beaven MA (2002). Serine/threonine protein kinases synergistically regulate phospholipase D1 and 2 and secretion in RBL-2H3 mast cells. Mol Immunol, 38(16–18), 1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherednichenko G, Zhang R, Bannister RA, Timofeyev V, Li N, Fritsch EB, … Pessah IN (2012). Triclosan impairs excitation-contraction coupling and Ca2+ dynamics in striated muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109(35), 14158–14163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang TM (1994). Activation of phospholipase D in human platelets by collagen and thrombin and its relationship to platelet aggregation. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1224(1), 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Woo CH, Yoon SB, & Kim JH (2004). Protein kinase Cdelta functions downstream of Ca2+ mobilization in FcepsilonRI signaling to degranulation in mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 114(5), 1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi OH, Adelstein RS, & Beaven MA (1994). Secretion from rat basophilic RBL-2H3 cells is associated with diphosphorylation of myosin light chains by myosin light chain kinase as well as phosphorylation by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem, 269(1), 536–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Kim YM, Combs C, Frohman MA, & Beaven MA (2002). Phospholipases D1 and D2 regulate different phases of exocytosis in mast cells. J Immunol, 168(11), 5682–5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cissel DS, Fraundorfer PF, & Beaven MA (1998). Thapsigargin-induced secretion is dependent on activation of a cholera toxin-sensitive and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-regulated phospholipase D in a mast cell line. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 285(1), 110–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft S (2001). Signalling roles of mammalian phospholipase D1 and D2. Cell Mol Life Sci, 58(11), 1674–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codazzi F, Teruel MN, & Meyer T (2001). Control of astrocyte Ca(2+) oscillations and waves by oscillating translocation and activation of protein kinase C. Curr Biol, 11(14), 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley WC, Sung TC, Roll R, Jenco J, Hammond SM, Altshuller Y, … Frohman MA (1997). Phospholipase D2, a distinct phospholipase D isoform with novel regulatory properties that provokes cytoskeletal reorganization. Curr Biol, 7(3), 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Armi C, Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Tian H, Morel E, Nezu A, Chan RB, … Di Paolo G (2010). The phospholipase D1 pathway modulates macroautophagy. Nat Commun, 1, 142. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud FC, Edmiston CE Jr., & Leaper D (2014). Meta-analysis of prevention of surgical site infections following incision closure with triclosan-coated sutures: robustness to new evidence. Surg Infect (Larchmt), 15(3), 165–181. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G, Altshuller YM, Vitale N, Huang P, Chasserot-Golaz S, Morris AJ, … Frohman MA (2003). Regulation of phospholipase D1 subcellular cycling through coordination of multiple membrane association motifs. J Cell Biol, 162(2), 305–315. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exton JH (1999). Regulation of phospholipase D. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1439(2), 121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, & Chen J (2001). Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science, 294(5548), 1942–1945. doi: 10.1126/science.1066015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fewtrell C, Kessler A, Metzger H,. (1979). Comparative aspects of secretion from tumor and normal mast cells. Advances in Inflammmation Reserach, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A (2017). FDA in Brief. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/FDAInBrief/ucm589474.htm.

- Furuno T, Shinkai N, Inoh Y, & Nakanishi M (2015). Impaired expression of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter suppresses mast cell degranulation. Mol Cell Biochem, 410(1–2), 215–221. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2554-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadi D, Wagenknecht-Wiesner A, Holowka D, & Baird B (2011). Sequestration of phosphoinositides by mutated MARCKS effector domain inhibits stimulated Ca(2+) mobilization and degranulation in mast cells. Mol Biol Cell, 22(24), 4908–4917. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-07-0614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli SJ, Kalesnikoff J, Grimbaldeston MA, Piliponsky AM, Williams CM, & Tsai M (2005). Mast cells as “tunable” effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu Rev Immunol, 23, 749–786. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girolamo F, Coppola C, & Ribatti D (2017). Immunoregulatory effect of mast cells influenced by microbes in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Behav Immun, 65, 68–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JM, Gordon JI, & Blackshear PJ (1989). Myristoylated and nonmyristoylated forms of a protein are phosphorylated by protein kinase C. Science, 246(4929), 503–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JM, Stumpo DJ, & Blackshear PJ (1989b). Characterization of the phosphorylation sites in the chicken and bovine myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate protein, a prominent cellular substrate for protein kinase C. J Biol Chem, 264(20), 11912–11919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo BZ, Xu G, Cao YG, Holbrook CC, & Lynch RE (2006). Identification and characterization of phospholipase D and its association with drought susceptibilities in peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Planta, 223(3), 512–520. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo ZH, Turner C, & Castle D (1998). Relocation of the t-SNARE SNAP-23 from lamellipodia-like cell surface projections regulates compound exocytosis in mast cells. Cell, 94(4), 537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81594-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Altshuller YM, Sung TC, Rudge SA, Rose K, Engebrecht J, … Frohman MA (1995). Human ADP-ribosylation factor-activated phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase D defines a new and highly conserved gene family. J Biol Chem, 270(50), 29640–29643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Jenco JM, Nakashima S, Cadwallader K, Gu Q, Cook S, … Morris AJ (1997). Characterization of two alternately spliced forms of phospholipase D1. Activation of the purified enzymes by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, ADP-ribosylation factor, and Rho family monomeric GTP-binding proteins and protein kinase C-alpha. J Biol Chem, 272(6), 3860–3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henage LG, Exton JH, & Brown HA (2006). Kinetic analysis of a mammalian phospholipase D: allosteric modulation by monomeric GTPases, protein kinase C, and polyphosphoinositides. J Biol Chem, 281(6), 3408–3417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508800200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo WD, Inoue T, Park WS, Kim ML, Park BO, Wandless TJ, & Meyer T (2006). PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science, 314(5804), 1458–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi T, Zhang J, Nicoletti LM, Grodzki AC, Jamur MC, Oliver C, & Siraganian RP (2004). Phospholipase D1 regulates high-affinity IgE receptor-induced mast cell degranulation. Blood, 104(13), 4122–4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua R, Zhou Y, Wu B, Huang Z, Zhu Y, Song Y, … Quan S (2017). Urinary triclosan concentrations and early outcomes of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Reproduction, 153(3), 319–325. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]