Abstract

While the literature on parent-child sexual communication among adolescent girls is robust overall, research that is specifically focused on communication between fathers and daughters is more limited. Further, there have been calls for work on parent-child sexual communication to be situated within a multi-factorial conceptual framework that distinguishes between different communication components, such as the communication source, content, frequency, quality, and timing. Using such a framework, this study examined aspects of father-daughter sexual communication as they compare to mother-daughter communication in a diverse sample of 193 girls (Mage =15.62). Results highlighted several gaps between father-daughter and mother-daughter communication. Girls reported covering less content and communicating less frequently about sexual topics with their fathers compared to their mothers. Girls also reported being less comfortable communicating and found their discussions to be less helpful with fathers than mothers. Girls were also less likely to report communicating with fathers about sexual topics before their sexual debut than with mothers. No significant differences were found in communication style (i.e., conversational or like a lecture) between fathers or mothers. Results highlight the importance of understanding the multifaceted process of parent-child communication and signal the need for targeted intervention efforts to improve upon father-daughter communication.

Keywords: parent-child sexual communication, adolescents, sexual health

Rates of poor sexual health outcomes among adolescent girls are concerning. Currently, one in four sexually active girls has a sexually transmitted infection (STI; Forhan et al., 2009) and rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia are dramatically rising among girls ages 15-19 (CDC, 2018). Left untreated, STIs can increase girls’ chances of contracting HIV and pose serious, long-term risks to reproductive health (Kreisel, Torrone, Bernstein, Hong, & Gorwitz, 2017). While adolescent pregnancy rates are declining, nearly 230,000 babies are born to adolescent girls annually (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Driscoll, & Mathews, 2017). These poor outcomes can be attributed, in part, to low rates of condom and contraceptive use: 46% of sexually active adolescent girls report condomless sex and 14% report using no form of contraception (Kann et al., 2018; Lindberg, Santelli, & Desai, 2016).

For girls, assertively pursuing health behaviors like condom use requires resisting gendered sexual norms that dictate girls be passive in their relationships with boys (Gagnon & Simon; Seabrook, Ward, Cortina, Giaccardi, & Lippman, 2017). Additionally, many girls in the rural South face unique barriers to sexual health including restrictive school-based sex education (Guttmacher Institute, 2019), limited access to resources accompanying reduced socioeconomic status and geographic isolation (Penman-Aguilar, Carter, Snead, & Kourtis, 2013), and culture-specific restrictive sexual norms (Swank, Frost, & Fahs, 2012). These factors contribute to sexual health disparities impacting girls in the rural South, especially girls of color (CDC, 2018).

One key factor in improving girls’ sexual health is their sexual communication with their parents. Parent-daughter sexual communication is linked to important forms of risk reduction among adolescent girls, including fewer sexual partners, delayed sexual initiation, and increased condom and contraceptive use (Coakley et al., 2017; Hadley et al., 2009; Sutton, Lasswell, Lanier, & Miller, 2014; Widman, Choukas-Bradley, Noar, Nesi, & Garrett, 2016). A meta-analysis of over 25,000 adolescents demonstrated that parent-child sexual communication had a small but significant and positive effect on condom and contraceptive use—an effect that was significantly stronger for girls than boys, and for communication with mothers compared to fathers (Widman et al., 2016). Additionally, girls who communicate with their parents about sex are more likely to engage in sexual health discussions with their sexual partners (Whitaker, Miller, May, & Levin, 1999; Widman, Choukas-Bradley, Helms, Golin, & Prinstein, 2014), which is an important predictor of contraceptive use (Johnson, Sieving, Pettingell, & McRee, 2015; Widman, Noar, Choukas-Bradley, & Francis, 2014). They also are more likely to apply detailed and accurate contraceptive knowledge to partner interactions (Nadeem, Romo, & Sigman, 2006), and maintain greater self-efficacy to communicate their boundaries with partners (DiClemente et al., 2001). These benefits may be especially salient to girls in the rural South; communicating with parents may provide them with sexual health information not obtained elsewhere, increase their access to sexual health resources (e.g., contraception), and expose them to empowering counter-narratives to norms which undermine girls’ sexual agency.

Although the literature on parent-daughter sexual communication is robust, much of this research has focused on communication with mothers or communication with “parents” without specifying parent gender. For example, only seven of the 52 studies in the Widman and colleagues (2016) meta-analysis included a focus on communication with fathers. As researchers have observed, a relative dearth of literature exists that specifically examines father-daughter sexual communication (e.g., Bennett, Harden, & Anstey, 2018; Hutchinson & Cederbaum, 2011; Santa Maria, Markham, Bluethmann, & Mullen, 2015). The primary focus on sexual communication with mothers may be reflective of a false assumption that fathers do not and need not play as large a role in their daughters’ sexual socialization (Lindsey, 2015; Wright, 2009). In addition to impeding scientific knowledge of father-daughter sexual communication patterns, this emphasis may perpetuate broader cultural norms that center mothers in parenting processes.

The most recent systematic review on father-child sexual communication by Wright (2009) synthesized literature from 1980 to 2008. Of the studies in this review, over half examined communication prevalence and process (e.g., Heisler, 2005; Kim & Ward, 2007; Sprecher, Harris, & Meyers, 2008), whereas few studies examined factors related to the content, quality, or timing of communication (e.g., Miller, Benson, & Galbraith, 2001; Peterson, 2006; Teitelman, Ratcliffe, & Cederbaum, 2008). Importantly, most of these studies did not include daughters, primarily focused on older youth, and generally lacked racially/ethnically-diverse samples.

Some qualitative research has elucidated the dynamics of father-daughter sexual communication. Collectively, this research suggests that the occurrence and perceived value of discussions with fathers about sex vary widely among girls. While some studies highlight a complete lack of father-daughter sexual communication or describe the scare-tactic messages fathers employ to deter daughters from sex (Averett, Benson, & Vaillancourt, 2008), others suggest that—for some girls—communication with fathers offers unique and valuable attributes. For example, some emerging adult women commented on the direct and non-judgmental quality of discussions about sex with their fathers (Nielsen, Latty, & Angera, 2013; Wisnieski, Sieving, & Garwick, 2015). Similarly, fathers more often than mothers report valuing approaching their children’s questions about sex honestly and directly (Wilson, Dalberth, Koo, & Gard, 2010). In another study, some women reported obtaining beneficial insight from their fathers into relationships with men (Hutchinson & Cederbaum, 2011). They felt their fathers could help to demystify other men’s perspectives. Additionally, despite commenting on the deficits of their communication with fathers, most of these women reported a desire for more father involvement throughout their sexual development. Importantly, fathers’ increased caring and involvement is associated with girls’ decreased sexual risk-taking (Sentino, Thompson, Nugent, & Freeman, 2018). As a whole, this research suggests that father-daughter sexual communication may be uniquely valuable and worthy of additional understanding.

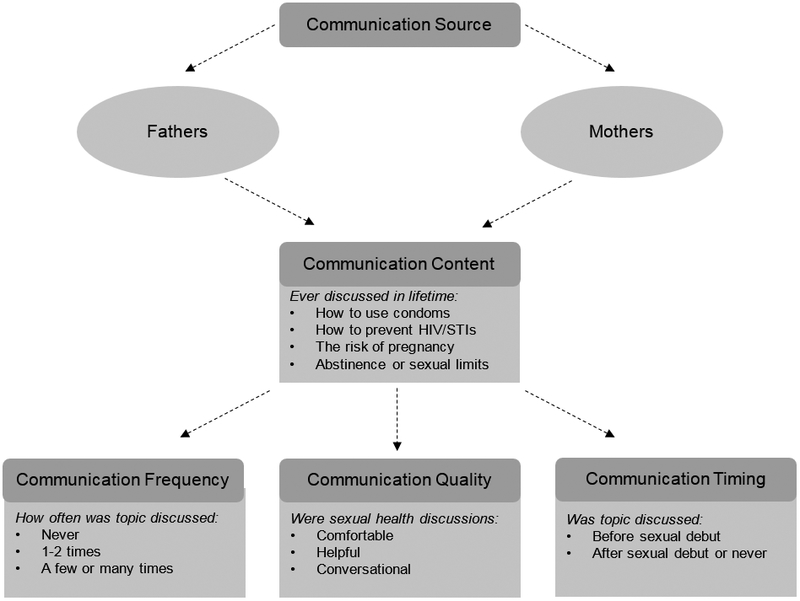

While previous studies on father-daughter sexual communication have provided important insight on various aspects of communication, most studies have lacked a clear conceptual framework to situate their study measures. Moreover, various inconsistencies throughout this body of literature have been attributed to the inadequate measurement of father-daughter communication (Langley, 2016). To address these issues, Jaccard, Dodge, & Dittus (2002) proposed a multifactorial conceptual communication framework for research on communication between parents and youth. Not only does this framework distinguish between whether adolescents communicate with mothers or fathers (i.e., communication source), but it also accounts for other key communication components including: 1) the sexual topics parents and adolescents cover (i.e., communication content), 2) how often communication occurs (i.e., communication frequency), 3) the perceived comfort, helpfulness, and style of these discussions (i.e., communication quality), and 4) when these talks occur in relation to the adolescent’s sexual debut (i.e., communication timing). Each of these components are included in the communication framework due to their evidenced potential to both independently and interactively impact adolescents’ sexual behavior (Guzmán et al., 2003; Hadley et al., 2009; Rogers, Ha, Stormshak, & Dishion, 2015). By examining these core communication facets in tandem, this multifactorial framework promotes a more holistic account of the process of parent-daughter sexual communication.

Few studies to date have incorporated such a comprehensive view of the communication process (for discussion, see Guilamo-Ramos, Lee, & Jaccard, 2016; Lefkowitz, 2002). Instead, researchers have commonly focused on one or two individual factors, such as measuring the content or frequency of communication (e.g., Kapungu et al., 2010; Whitaker & Miller, 2000; Widman et al., 2014), without also capturing the source, quality, or timing of these conversations. In fact, we are not aware of any studies that have simultaneously assessed the source, content, frequency, quality, and timing of parent-daughter sexual communication. Further, few studies have compared sexual communication with fathers versus mothers across several communication components using the same dataset. Thus, there remains a need for a timely, multifactorial investigation of father-daughter sexual communication juxtaposed with mother-daughter sexual communication.

Study Purpose

The present study sought to fill several gaps in the parent-child sexual communication literature by focusing on an understudied area: sexual communication between adolescent girls and their fathers. We applied a multifactorial communication framework (Jaccard et al., 2002; see Figure 1) to examine four components of the communication process: the content of these conversations, the frequency with which the communication occurred, the quality of these conversations, and their timing in relationship to girls’ sexual debut. Additionally, we aimed to understand the ways in which these four communication components differed when adolescent girls communicated with their fathers compared to their mothers (i.e., communication source). Importantly, we examined our research questions in a racially/ethnically-diverse sample of middle adolescent girls. On the basis of the existing literature, the following research question and hypotheses were investigated:

Figure 1.

Operationalization of Multifactorial Sexual Communication Framework

How do the content, frequency, quality, and timing of sexual communication with fathers and daughters compare to that with mothers and daughters? Consistent with past research (DiIorio, Kelley, & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999; Feldman & Rosenthal, 2000; Jerman & Constantine, 2010; Kapungu et al., 2010; Wyckoff et al., 2008), we hypothesize that fewer girls will report ever communicating about four sexual topics—condom use, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, abstinence/sexual limits—with their fathers compared to their mothers. Additionally, we hypothesize that girls will report less frequent communication with their fathers than their mothers. Also consistent with past research (Collins, Angera, & Latty, 2008; DiIorio et al., 1999; Feldman & Rosenthal, 2000), we expect girls will report lower quality (i.e., less comfortable, helpful, and conversational) communication with fathers than mothers. As we are unaware of any studies comparing fathers and mothers on the timing of sexual communication, we take an exploratory approach in examining if girls will be less likely to report discussing sexual topics before their sexual debut with their fathers versus their mothers.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were part of an evaluation study of a brief, web-based sexual health intervention (reference removed for masked review). Tenth grade girls were recruited from four rural, low-income high schools in the southeastern U.S. using active parental consent and student assent. Of the 371 girls who were recruited, 229 received parental consent for the study and 222 assented. Those 222 girls completed a baseline survey, either a sexual health intervention or control program focused on academic achievement, and a post-test. Finally, 211 participants completed a follow-up survey 4 months later (95% retention).

Data for the current analyses come from the 4-month follow-up time point. Of note, the intervention did not focus specifically on parent communication, and there were no significant differences between intervention and control groups on any of the parental sexual communication outcomes of interest,1 so data from the two study arms were combined. Of the 211 participants at this time point, 18 were excluded because their reports on the content and timing measures were inconsistent (for example, reporting they never discussed condoms but also reporting they discussed condoms before sexual debut) resulting in a final sample of 193 girls. Participants were between the ages of 14–17 (Mage=15.62, SD=0.56). The sample was racially/ethnically-diverse (37% White, 25% African American/Black, 31% Hispanic/Latinx, 7% other/mixed).2 Approximately 40% and 48% of girls reported that their fathers and mothers, respectively, had at least some college education.3 Further, 79% of participants identified their sexual orientation as heterosexual, with the remaining participants identifying as lesbian/gay (5%), bisexual (14%), or pansexual/other (3%). Twenty-two percent of participants indicated that they had engaged in penis-in-vagina sex.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board. To maximize the validity of self-reported sexual behavior, participants completed confidential surveys using computer-assisted self-interviews (CASI) in a small-group classroom setting. CASI procedures have been shown to increase the validity of self-report data when collecting sensitive data from youth (Turner et al., 1998). Additionally, we arranged seating so that there was at least one open seat between participants, provided participants with folders to position as added privacy barriers, and instructed them to focus on their own screens. The survey took approximately 45 minutes to complete and participants were compensated with a $10 gift card.

Measures

Demographics.

All participants reported their age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and sexual activity status. In the current study, sexual activity status was operationalized as ever experiencing penis-in-vagina sex.

Parent-child sexual communication.

Participants separately indicated if they had a father (or father-figure) and/or a mother (or mother-figure) currently in their life. We refer to these parental figures more generally as fathers and mothers throughout this manuscript. Altogether, 163 girls reported having both a father and a mother, 5 girls reported only having a father, and 25 girls reported only having a mother. Girls responded to all measures of parent-child sexual communication frequency, content, quality, and timing separately for each parent. We focused on four topics that directly pertain to preventing negative sexual health outcomes among adolescent girls: 1) how to use condoms, 2) how to prevent HIV/STIs, 3) the risk of pregnancy, and 4) abstinence or sexual limits (DiClemente et al., 2001; Sales et al., 2012; Widman et al., 2014).

Communication frequency.

For both their father and their mother separately, participants reported on their lifetime frequency of communication for each of the four sexual topics: condoms, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, and abstinence/sexual limits. Participants reported how often they discussed each topic on a three-point Likert scale from 0=“never,” 1=“1-2 times,” to 2=“a few or many times.” Items were summed to create a total frequency score. Reliability was good for communication frequency with fathers (α=.90) and mothers (α=.84).

Communication content.

To assess base percentages of communication that ever occurred about each topic (i.e., condoms, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, and abstinence/limits), the four frequency items described above were dichotomized into a score of 0=“never discussed that item” or 1=“discussed that item 1 time or more.”

Communication quality.

If participants indicated that they had communicated about at least one of the four topics, they were further prompted to report on three key aspects of the quality of communication about sexual topics with that parent: comfort, helpfulness, and style (Guzmán et al., 2003; Rogers et al., 2015). Girls responded to three items on a 4-point continuous scale to indicate how comfortable they felt having the communication (1=very uncomfortable to 4=very comfortable), how helpful they found the communication (1=very unhelpful to 4=very helpful), and the nature of the communication style (1=very much like a lecture to 4=very much like a conversation).

Communication timing.

Finally, girls were prompted to report on the timing of communication in relation to their sexual debut. For each of the four sexual topics (i.e., condoms, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, abstinence/sexual limits), sexually active girls (n=43) were asked to separately report for each parent whether they had 1) discussed the topic before they had sex, 2) discussed the topic after they had sex, or 3) never discussed the topic. All participants (n=193) were then categorized into 1 of 2 mutually exclusive categories: (1) talked before sexual debut or (2) talked after sexual debut or never. The category, talked before sexual debut, included those cases in which the topic had been discussed but sex had not yet occurred. The category, talked after sexual debut or never, included cases in which the topic was first discussed after sexual debut, cases in which sex had occurred but the topic had not been discussed, and cases in which the topic had not been discussed and sex had not yet occurred. Although girls in the second category who had not yet had sex could technically communicate with a parent at some point in the future, such communication would be occurring late in this critical developmental period (for similar coding and rationale, see Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003).

Analysis Plan

First, for both fathers and mothers, we conducted descriptive analyses to determine the percentage of girls who ever discussed each topic; the mean frequency of communication for each topic; the mean communication quality as measured by comfort, helpfulness, and style; and the percentage of girls who reported discussing each topic before sexual debut. We then conducted chi square tests (for the content and timing analyses), Wilcoxin signed-rank tests (for the frequency analyses), and paired-sample t tests (for the quality analyses) to determine if these communication patterns differed between fathers and mothers among the 163 girls reporting data for two parents. For all comparisons, we used a Bonferroni correction to maintain a family-wise Type I error rate of p < .05 (Keppel & Wickens, 2004).

Results

Differences in Communication Content and Timing Between Mothers and Fathers

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive and comparative analyses of daughters’ communication with fathers compared to mothers according to communication content, frequency, quality, and timing. As predicted, girls reported a lesser likelihood of communicating about each of the four sexual topics with their fathers compared to their mothers. Upon examination of the specific communication content, pregnancy was discussed by the most girls (39% with fathers, 80% with mothers), while condoms were discussed by the fewest girls (17% with fathers, 47% with mothers). Over half of girls (59%) reported they had never discussed any of the four sexual topics with their father, while relatively few girls (14%) reported never having these conversations with their mother. With regard to timing, across all four sexual topics, a significantly smaller percentage of girls reported communicating with their father before their sexual debut compared to with their mother. However, it should be noted that over 90% of girls who reported talking about a sexual topic with either parent reported doing so before their sexual debut. For example, among the 29 girls who reported discussing condoms with their father, 27 of them reported doing so before their sexual debut.

Table 1.

Father-Daughter Compared to Mother-Daughter Sexual Communication Content, Frequency, Quality, and Timing

| Communication Factors | Fathers | Mothers | Paired Group Comparisons a,b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (ever discussed)c | n | (%) | n | (%) | χ2 | p |

| How to use condoms | 29 | (17.3) | 88 | (46.8) | 25.49 | < .001 |

| How to prevent HIV/STIs | 35 | (20.8) | 115 | (61.2) | 16.69 | < .001 |

| The risk of pregnancy | 66 | (39.3) | 150 | (79.8) | 12.45 | < .001 |

| Abstinence or sexual limits | 51 | (30.4) | 139 | (73.9) | 21.30 | < .001 |

| Discussed all 4 topics | 27 | (16.1) | 81 | (43.1) | 24.61 | < .001 |

| Did not discuss any topics | 99 | (58.9) | 27 | (14.4) | 12.01 | < .001 |

| Frequency (lifetime) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | Z | p |

| How to use condoms | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.76 | −6.05 | < .001 |

| How to prevent HIV/STIs | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 0.83 | −7.62 | < .001 |

| The risk of pregnancy | 0.55 | 0.75 | 1.38 | 0.80 | −8.84 | < .001 |

| Abstinence or sexual limits | 0.44 | 0.71 | 1.18 | 0.82 | −8.82 | < .001 |

| Quality | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | t | p |

| Comfort | 2.09 | (0.89) | 2.49 | (0.93) | 5.65 | < .001 |

| Helpfulness | 3.03 | (0.79) | 3.18 | (0.82) | 3.60 | < .001 |

| Style | 2.61 | (1.05) | 2.61 | (1.04) | 1.34 | .184 |

| Timing (before sexual debut) | n | (%) | n | (%) | χ2 | p |

| Discussed condoms | 27 | (50.0) | 84 | (77.1) | 24.61 | < .001 |

| Discussed HIV/STIs | 33 | (55.0) | 112 | (84.2) | 16.56 | < .001 |

| Discussed pregnancy | 63 | (71.6) | 144 | (89.4) | 14.21 | < .001 |

| Discussed abstinence/limits | 48 | (64.9) | 135 | (87.1) | 22.20 | < .001 |

n = 163 girls with data for both their mother and father included in all communication variable comparisons except communication quality; the quality comparison includes girls who reported having some sexual communication with both their mother and father and therefore could report on the quality of that communication (n = 66).

Results of the timing comparisons reveal similar patterns when removing girls who report never having sex and never communicating about condoms, χ2(1, n = 51) = 20.05, p < .001, HIV/STIs χ2(1, n = 56) = 24.59, p < .001, pregnancy, χ2(1, n = 83) = 30.14, p < .001, and abstinence/sexual limits, χ2(1, n = 72) = 34.64, p < .001.

Of the five girls without a mother/mother-figure, one girl reported communicating about all four topics with her father, whereas the other four girls reported no communication. Of the 25 girls without a father/father-figure, the majority (n = 21) reported communicating with their mother about at least one topic and nine girls communicated about all four topics.

Differences in Communication Frequency and Quality Between Mothers and Fathers

Table 1 summarizes differences in communication frequency on all four topics and differences in quality as measured by comfort, helpfulness, and style of sexual communication between fathers and mothers. Across all four topics, girls reported less frequent communication with fathers compared to mothers. In addition, girls reported communication with fathers to be of significantly lower quality than communication with mothers in two domains: girls were less comfortable communicating with fathers than with mothers, and felt it was less helpful with fathers than with mothers. However, no significant differences were reported in how girls rated the communication style (i.e., more conversational versus more like a lecture) between fathers and mothers.

Discussion

The current study applied a multifactorial sexual communication framework (Jaccard et al., 2002) to examine key components of father-daughter communication compared to mother-daughter communication. Results highlight several gaps between girls’ communication with their fathers compared to their communication with their mothers across most components. Specifically, girls were less likely to report discussing condoms, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, and abstinence/sexual limits with their fathers compared to their mothers (for similar findings, see DiIorio et al., 1999; Feldman & Rosenthal, 2000; Kapungu et al., 2010; Wyckoff et al., 2008). Girls also talked less frequently about each topic, felt the communication was less comfortable and helpful, and reported that the communication was less likely to have occurred with their fathers before their sexual debut compared to their mothers. Results of the current study clearly signal that fathers’ communication with daughters lags behind mothers’, and targeted intervention efforts to improve upon father-daughter communication are needed. Such efforts could help to increase the likelihood that girls engage in sexual communication with at least one parent and, ideally, with both parents. This study also underscores the importance of understanding parent-child communication as a multifaceted process and emphasizes the need for researchers to differentiate the communication source. Studies that fail to distinguish between mothers and fathers provide an inadequate view of this communication process.

This study makes several contributions to the literature on parent-daughter sexual communication. First, compared to what is known about communication between daughters and mothers, relatively little is known about girls’ communication with their fathers. In particular, few studies have looked at the timing of father-daughter communication about sexual health topics in relation to girls’ sexual debut. Additionally, no studies to our knowledge have situated father-daughter communication within a communication framework that considers multiple components of the communication process. This multifactorial sexual communication framework enabled us to obtain a broader view of the ways in which girls’ sexual communication with fathers is distinct from their communication with mothers (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2016; Jaccard et al., 2002).

Importantly, this study also provides an examination of parent-child sexual communication among a racially/ethnically-diverse sample of girls from a rural, low-income area in the southeast U.S. Statistically, these girls are at heightened and increasing risk for negative sexual health outcomes (CDC, 2018) and are in need of all available strategies to ease the disproportionate sexual health burden that they carry. However, parents and daughters from rural, southern U.S. locations may be more reticent to discuss sexual issues than those from urban, northern locations. Rural, southern communities are often characterized by an emphasis on religiosity, conservatism, and traditional values and gender roles (Swank et al., 2012) which may inhibit frank communication about sex. The extent to which the regional sexual health disparities align with regional differences in parent-daughter sexual communication should be an inquiry of future research.

Despite the relative strengths of mothers’ communication patterns compared to fathers’ patterns, it is important to note that there is room for improvement in the sexual communication practices of parents of both genders. Nearly 60% of fathers and 15% of mothers did not discuss any of the four sexual topics. Among those that did have some communication, both fathers and mothers were more likely to discuss sexual risks and avoiding sex (i.e., pregnancy, HIV/STIs, abstinence) in notably larger percentages compared to communicating about safe sex. Fewer than one-fifth of fathers and less than half of mothers discussed how to use condoms. These low base rates of discussions about the protective role of condoms are in line with previous findings that—particularly with daughters—parents tend to focus on the potential negative consequences of sex (e.g., pregnancy, HIV/STIs; Guttmacher Institute, 2017). Thus, broadening the range of sexual topics parents cover with their daughters should be a focus of interventions.

It is likely that safe-sex content is key to the protective effects of parent-child sexual communication as per the pathways outlined in the Integrative Model of Behavior Change (i.e., perceived norms, self-efficacy, and attitudes; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). For example, discussions that focus on abstinence may impart parental disapproval about sex, thus shaping girls’ perceived norms; conversely, conversations that emphasize condom use may help to boost girls’ self-efficacy (Rogers, 2016). Moreover, girls’ average ratings of fathers’ and mothers’ communication styles suggest that parents are conveying conflicting messages by talking about sex with their daughters but doing so with a disapproving tone. It is critical that parents not only have open conversations about the negative outcomes that can be incurred from unprotected sex but also how girls can be empowered to take an active role in creating safe and positive sexual experiences (Schalet, 2011). Such discussions could counter dominant sociocultural narratives which undermine girls’ sexual agency. Additionally, results of this study suggest that, regardless of which parent they talk to, in general, girls are uncomfortable communicating with their parents about sex. Only 18% and 9% of girls reported feeling very comfortable talking about sex with their mothers and fathers, respectively. However, parents should not be deterred by this experience as, on average, girls also report that the communication with both mothers and fathers is helpful. These findings suggest that even when these conversations are awkward, parents can be important sexual health educators for their daughters.

A final point worth noting is that nearly all girls who reported communicating about any topic with either parent did so before their sexual debut. For example, 93% of girls who discussed condoms with their fathers and 95% of girls who discussed condoms with their mothers did so before sexual debut. So, although fathers were generally less likely to report communicating about a topic before their daughter’s sexual debut than mothers, the fathers who did talk with their daughters had these conversations at an ideal time in girls’ sexual development (Beckett et al., 2010; Miller, Levin, Whitaker, & Xu, 1998). Interestingly, an earlier study of college-aged adolescents (Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003) found that fewer than 40% of participants who reported sexual communication with their father had this communication prior to their sexual debut. It is possible that the later timing of father communication in this earlier study may be attributable to the larger window of time between the communication and retrospective participant reports; however, it is also possible that the results of the current study reflect evolving ideas about fathers as influential figures of daughters’ sexual socialization. Thus, more fathers may be invested in their role as sex educators than fathers of previous generations. Future work should investigate this possibility.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several study limitations are worth consideration. First, this study used girls’ self-reports to examine communication processes with their parents. An important next step in this line of work would be to examine these multifactorial sexual communication processes with both father-daughter and mother-daughter dyads in the same study (Beckett et al., 2010). Next, although this sample provides needed data on sexual communication among girls from the rural South, results of this study may not generalize to girls in other geographic locations. Future research should attend to this and other cultural factors including nationality, religion, and socioeconomic status which may contribute to variability in communication. This study also centered on parent communication with daughters; however, it will also be important in the future to understand the multifaceted dynamics of parent communication with sons. Previous research has found a general trend that parents tend to communicate with their children of the same gender (Flores & Barroso, 2017), and qualitative, retrospective studies suggest that daughters may receive more risk-focused communication than sons (Goldfarb, Lieberman, Kwiatkowski, & Santos, 2015). Studies examining these dynamics would be greatly enriched by the application of a multifactorial communication framework, which would yield a more nuanced picture of the differences between parent-child communication by parent and child gender.

However, despite the strength of our use of the multifactorial communication framework, our methods have limitations. First, while we examined sexual communication timing in a manner similar to previous research and labeled this communication as “on time” versus “late” (e.g., Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003), we do not mean to imply that there can be no positive effects of late communication. Late discussions, even those conversations started after adolescents have had sex, may have a positive influence in terms of adolescent sexual behaviors, though early sexual communication is optimal (Pariera, 2016; Wyckoff et al., 2008). Also, our measure of communication content generally lacked specificity. For example, our item assessing communication about abstinence/sexual limits may conflate two qualitatively distinct conversations. It is possible that girls who received dogmatic abstinence-only messages from their parents responded to this item in a similar manner as those who have had more nuanced discussions with their parents about negotiating sexual limits, such as a boundary that sex must include a condom. Future studies should incorporate these distinctions in their measures. Relatedly, given the push toward a sexual health (versus a sexual risk) paradigm (see Fortenberry, 2013), future research should account for a wider range of sexual topics that parents and teens may discuss, including sexual pleasure, consent, and sexual orientation (Mastro & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2015).

We also did not have data on other influential components of the communication process, such as the ordering and level of detail of communication content as well as the type of argument appeal (see Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2016; Jaccard et al., 2002). In addition to examining these communication components, research should examine broader factors including the physical or situational context in which father-daughter sexual communication takes place. For example, the CDC (2014) advises parents to consider initiating communication while driving so girls can listen without making eye contact. Parent-daughter sexual communication patterns may also vary according to factors such as the overall relationship quality girls have with each parent or their specific family household arrangement (e.g., single- versus dual-parent household); future multifactorial research in this area should consider these dynamics.

As parents, fathers are uniquely positioned in their ability to instill the knowledge, values, and boundaries that accompany healthy sexuality throughout the course of daughters’ lives (Crosby & Miller, 2002). In contrast to mothers, fathers can also offer a man’s perspective which many girls value in conversations about sex (Brown, Rosnick, Webb-Bradley, & Kirner, 2014; Hutchinson & Cederbaum, 2011; Wisnieski et al., 2015). Many girls may also benefit from having a key male figure in their lives model healthy sexual communication practices (Bowling & Werner-Wilson, 2000). The current study demonstrated that many fathers are not having these important conversations with their daughters as often as mothers, perhaps due to factors such as low self-efficacy, not valuing the communication, or believing their daughter is too young (Pariera, 2016). Interventions targeting father-daughter sexual communication should help fathers to view sexual communication as an ongoing process with potentially far-reaching positive impacts on the lives of their daughters.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (R00 HD075654, K24 HD069204); NC State College of Humanities and Social Sciences Research Office; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410).

Footnotes

Results showed no significant differences between intervention and control groups in: (1) the frequency of communication about condoms, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, abstinence/sexual limits with mothers (ts(186) = −0.58–1.37, ps = .17–.80) or fathers (ts(166) = −0.28–0.55, ps = .58–.97); (2) the comfort, helpfulness, or style of communication with mothers (ts(159) = 0.18–0.76, ps = .45–.86) or fathers (ts(159) = −1.03–1.12, ps = .27–.56); or (3) the timing of communication about condoms, HIV/STIs, pregnancy, or abstinence/limits with mothers (χ2s(1) = 0.05–0.49, ps = .48–.82) or fathers (χ2s(1) = 0.001–0.30, ps = .56–.98

Results showed no significant differences by race in frequency, quality, and timing of communication with mothers and fathers.

Results showed no significant differences by parent education in frequency, quality, and timing of communication with mothers and fathers, with two exceptions. Compared to girls with mothers with high school or less education, girls with mothers with at least some college education had a greater likelihood of reporting communicating a few or many times about how to prevent HIV/STIs, χ2(1) = 7.15, p = .008, and abstinence/sexual limits, χ2(1) = 8.04, p = .005.

References

- Averett P, Benson M, & Vaillancourt K (2008). Young women’s struggle for sexual agency: The role of parental messages. Journal of Gender Studies, 17, 331–344. doi: 10.1080/09589230802420003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Martino S, Kanouse DE, Corona R, Klein DJ, & Schuster MA (2010). Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children’s sexual behaviors. Pediatrics, 125, 34–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C, Harden J, & Anstey S (2018). Fathers as sexuality educators: Aspirations and realities. An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Sex Education, 18, 74–89. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2017.1390449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling SW, & Werner-Wilson RJ (2000). Father-daughter relationships and adolescent female sexuality. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children, 3, 5–28. doi: 10.1300/J129v03n04_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, Rosnick CB, Webb-Bradley T, & Kirner J (2014). Does daddy know best? Exploring the relationship between paternal sexual communication and safe sex practices among African-American women. Sex Education, 14, 241–256. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2013.868800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Talking with your teens about sex: Going beyond “the talk”. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/pdf/talking_teens.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). STDs in adolescents and young adults. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/adolescents.htm

- Clawson CL, & Reese-Weber M (2003). The amount and timing of parent‐adolescent sexual communication as predictors of late adolescent sexual risk‐taking behaviors. The Journal of Sex Research, 40, 256–265. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coakley TM, Randolph S, Shears J, Beamon ER, Collins P, & Sides T (2017). Parent-youth communication to reduce at-risk sexual behavior: A systematic literature review. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27, 609–624. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2017.1313149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CL, Angera JL, & Latty CR (2008). College aged females’ perceptions of their fathers as sexuality educators. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 2, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, & Miller KS (2002). Family influences on adolescent females’ sexual health In Handbook of women’s sexual and reproductive health (pp. 113–127). Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, & Davies SL (2001). Parent-adolescent communication and sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescent females. The Journal of Pediatrics, 139, 407–412. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diiorio C, Kelley M, & Hockenberry-Eaton M (1999). Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24, 181–189. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00115-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SS, & Rosenthal DA (2000). The effect of communication characteristics on family members’ perceptions of parents as sex educators. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10(2), 119–150. doi: 10.1207/SJRA1002_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Flores D, & Barroso J (2017). 21st Century Parent-Child Sex Communication in the United States: A Process Review. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 532–548. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1267693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, … Markowitz LE (2009). Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics, 124, 1505–1512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD (2013). The evolving sexual health paradigm: Transforming definitions into sexual health practices. AIDS, 27 Suppl 1, S127–133. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon J, & Simon W 2005. Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality (Vol. 2). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb E, Lieberman L, Kwiatkowski S, & Santos P (2015). Silence and censure: A qualitative analysis of young adults’ reflections on communication with parents prior to first sex. Journal of Family Issues, 39, 28–54. doi: 10.1177/0192513X15593576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Lee JJ, & Jaccard J (2016). Parent-adolescent communication about contraception and condom use. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 14–16. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. (2017). American adolescents’ sources of sexual health information. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/facts-american-teens-sources-information-about-sex.pdf

- Guttmacher Institute. (2019). Sex and HIV education. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education

- Guzmán BL, Schlehofer-Sutton MM, Villanueva CM, Stritto MED, Casad BJ, & Feria A (2003). Let’s talk about sex: How comfortable discussions about sex impact teen sexual behavior. Journal of Health Communication, 8, 583–598. doi: 10.1080/716100416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley W, Brown LK, Lescano CM, Kell H, Spalding K, DiClemente R, & Donenberg G (2009). Parent-adolescent sexual communication: Associations of condom use with condom discussions. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 997–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9468-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler JM (2005). Family communication about sex: Parents and college-aged offspring recall ciscussion topics, satisfaction, and parental involvement. Journal of Family Communication, 5, 295–312. doi: 10.1207/s15327698jfc0504_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, & Cederbaum JA (2011). Talking to daddy’s little girl about sex: Daughters’ reports of sexual communication and support from fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 550–572. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dodge T, & Dittus P (2002). Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: A conceptual framework. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2002, 9–42. doi: 10.1002/cd.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerman P, & Constantine NA (2010). Demographic and psychological predictors of parent-adolescent communication about sex: A representative statewide analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1164–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9546-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AZ, Sieving RE, Pettingell SL, & McRee A-L (2015). The roles of partner communication and relationship status in adolescent contraceptive use. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 29, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, … Ethier KA (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002), 67, 1–114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapungu CT, Baptiste D, Holmbeck G, McBride C, Robinson-Brown M, Sturdivant A, … Paikoff R (2010). Beyond the “birds and the bees”: Gender differences in sex-related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Family Process, 49, 251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G, & Wickens T (2004). Simultaneous comparisons and the control of type I errors In Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook (4th ed., pp. 111–130). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JL, & Ward LM (2007). Silence speaks volumes: Parental sexual communication among Asian American emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 3–31. doi: 10.1177/0743558406294916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel K, Torrone E, Bernstein K, Hong J, & Gorwitz R (2017). Prevalence of pelvic inflammatory disease in sexually experienced women of reproductive age - United States, 2013-2014. MMWR, 66, 80–83. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6603a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley C (2016). Father knows best: Paternal presence and sexual debut in African‐American adolescents living in poverty. Family Process, 55, 155–170. doi:doi: 10.1111/famp.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES (2002). Beyond the yes-no question: Measuring parent-adolescent communication about sex. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2002, 43–56. doi: 10.1002/cd.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg L, Santelli J, & Desai S (2016). Understanding the decline in adolescent fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59, 577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey LL (2015). Gender roles: A sociological perspective. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, & Mathews TJ (2017). Births: Final data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports, 66, 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastro S, & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2015). Let’s talk openly about sex: Sexual communication, self-esteem and efficacy as correlates of sexual well-being. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 579–598. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2015.1054373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Benson B, & Galbraith KA (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review, 21, 1–38. doi: 10.1006/drev.2000.0513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, & Xu X (1998). Patterns of condom use among adolescents: The impact of mother-adolescent communication. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1542–1544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Romo LF, & Sigman M (2006). Knowledge about condoms among low-income pregnant Latina adolescents in relation to explicit maternal discussion of contraceptives. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 119.e119–119.e115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SK, Latty CR, & Angera JJ (2013). Factors that contribute to fathers being percieved as good or poor sexuality educators for their daughters. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice About Men as Fathers, 11, 52–70. doi: 10.3149/fth.1101.52 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pariera KL (2016). Barriers and prompts to parent-child sexual communication. Journal of Family Communication, 16, 277–283. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2016.1181068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penman-Aguilar A, Carter M, Snead MC, & Kourtis AP (2013). Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. Public Health Reports, 128, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/00333549131282S102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SH (2006). The importance of fathers. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 13, 67–83. doi: 10.1300/J137v13n03_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AA (2016). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescents’ sexual behaviors: A conceptual model and systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 2, 293–313. doi: 10.1007/s40894-016-0049-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AA, Ha T, Stormshak EA, & Dishion TJ (2015). Quality of parent-adolescent conversations about sex and adolescent sexual behavior: An observational study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57, 174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Lang DL, DiClemente RJ, Latham TP, Wingood GM, Hardin JW, & Rose ES (2012). The mediating role of partner communication frequency on condom use among African American adolescent females participating in an HIV prevention intervention. Health Psychology, 31, 63–69. doi: 10.1037/a0025073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Maria D, Markham C, Bluethmann S, & Mullen PD (2015). Parent-based adolescent sexual health interventions and effect on communication outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Perspect Sex Reprod Health, 47, 37–50. doi: 10.1363/47e2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalet AT (2011). Beyond abstinence and risk: A new paradigm for adolescent sexual health. Womens Health Issues, 21, S5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook RC, Ward LM, Cortina LM, Giaccardi S, & Lippman JR (2017). Girl power or powerless girl? Television, sexual scripts, and sexual agency in sexually active young women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41, 240–253. doi: 10.1177/0361684316677028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sentino P, Thompson PL, Nugent WR, & Freeman D (2018). Adolescent daughters’ perceptions of their fathers’ levels of communication and care: How these variables influence female adolescent sexual behaviors. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28, 632–646. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2018.1449693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Harris G, & Meyers A (2008). Perceptions of sources of sex education and targets of sex communication: Sociodemographic and cohort effects. The Journal of Sex Research, 45, 17–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490701629522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MY, Lasswell SM, Lanier Y, & Miller KS (2014). Impact of parent-child communication interventions on sex behaviors and cognitive outcomes for Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino Youth: A systematic review, 1988–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank E, Frost DM, & Fahs B (2012). Rural location and exposure to minority stress among sexual minorities in the United States. Psychology & Sexuality, 3, 226–243. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2012.700026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Ratcliffe SJ, & Cederbaum JA (2008). Parent-adolescent communication about sexual pressure, maternal norms about relationship power, and STI/HIV protective behaviors of minority urban girls. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14, 50–60. doi: 10.1177/1078390307311770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, & Sonenstein FL (1998). Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science, 280, 867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, & Miller KS (2000). Parent-adolescent discussions about sex and condoms: Impact on peer influences of sexual risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 251–273. doi: 10.1177/0743558400152004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, May DC, & Levin ML (1999). Teenage partners’ communication about sexual risk and condom use: The importance of parent-teenager discussions. Family Planning Perspectives, 31, 117–121. doi: 10.2307/2991693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Golin CE, & Prinstein MJ (2014). Sexual communication between early adolescents and their dating partners, parents, and best friends. The Journal of Sex Research, 51, 731–741. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.843148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM, Nesi J, & Garrett K (2016). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 52–61. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Noar SM, Choukas-Bradley S, & Francis DB (2014). Adolescent sexual health communication and condom use: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 33, 1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/hea0000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EK, Dalberth BT, Koo HP, & Gard JC (2010). Parents’ perspectives on talking to preteenage children about sex. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42, 56–63. doi: 10.1363/4205610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisnieski D, Sieving R, & Garwick A (2015). Parent and family influences on young women’s romantic and sexual decisions. Sex Education, 15, 144–157. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2014.986798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PJ (2009). Father-child sexual communication in the United States: A review and synthesis. Journal of Family Communication, 9, 233–250. doi: 10.1080/15267430903221880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff SC, Miller KS, Forehand R, Bau JJ, Fasula A, Long N, & Armistead L (2008). Patterns of sexuality communication between preadolescents and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 649–662. doi: 10.1007/s10826-007-9179-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]