Abstract

Functional MRI (fMRI) signals are robustly detectable in white matter (WM) but they have been largely ignored in the fMRI literature. Their nature, interpretation, and relevance as potential indicators of brain function remain under explored and even controversial. Blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast has for over 25 years been exploited for detecting localized neural activity in the cortex using fMRI. While BOLD signals have been reliably detected in grey matter (GM) in a very large number of studies, such signals have rarely been reported from WM. However, it is clear from our own and other studies that although BOLD effects are weaker in WM, using appropriate detection and analysis methods they are robustly detectable both in response to stimuli and in a resting state. BOLD fluctuations in a resting state exhibit similar temporal and spectral profiles in both GM and WM, and their relative low frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) signal powers are comparable. They also vary with baseline neural activity e.g. as induced by different levels of anesthesia, and alter in response to a stimulus. In previous work we reported that BOLD signals in WM in a resting state exhibit anisotropic temporal correlations with neighboring voxels. On the basis of these findings, we derived functional correlation tensors that quantify the correlational anisotropy in WM BOLD signals. We found that, along many WM tracts, the directional preferences of these functional correlation tensors in a resting state are grossly consistent with those revealed by diffusion tensors, and that external stimuli tend to enhance visualization of specific and relevant fiber pathways. These findings support the proposition that variations in WM BOLD signals represent tract-specific responses to neural activity. We have more recently shown that sensory stimulations induce explicit BOLD responses along parts of the projection fiber pathways, and that task-related BOLD changes in WM occur synchronously with the temporal pattern of stimuli. WM tracts also show a transient signal response following short stimuli analogous to but different from the hemodynamic response function (HRF) characteristic of GM. Thus there is converging and compelling evidence that WM exhibits both resting state fluctuations and stimulus-evoked BOLD signals very similar (albeit weaker) to those in GM. A number of studies from other laboratories have also reported reliable observations of WM activations. Detection of BOLD signals in WM has been enhanced by using specialized tasks or modified data analysis methods. In this mini-review we report summaries of some of our recent studies that provide evidence that BOLD signals in WM are related to brain functional activity and deserve greater attention by the neuroimaging community.

1. Introduction

Functional MRI based on the BOLD (blood oxygenation level dependent) effect is well established for studies of cortical activity both in a resting state and in response to stimulation, but the occurrence and significance of similar signals in white matter (WM) have received much less attention and even remain controversial. In this mini-review we report summaries of some recent studies of task-evoked and resting state MRI signals in WM that demonstrate that BOLD effects in WM (a) are readily detectable using appropriate methods (b) behave similarly to BOLD signals from cortex but are weaker and of longer latency, and (c) are modulated by neural activity in grey matter (GM) volumes to which they connect. Collectively these results, in combination with reports from others, provide compelling evidence that BOLD signals in WM deserve greater emphasis in attempts to understand the overall functional architecture of the brain, and need to be properly considered in current analyses of functional studies. Further details of the experiments and results summarized below can be found in our recent publications [1–8].

There are substantive reasons to doubt the detectability and significance of BOLD effects in WM. The blood flow and volume in WM are approximately only about 25% as large as in GM [9,10], and the energy requirements for dynamic WM functions are usually considered low compared to those in the cortex [11] so it is not clear whether a significant BOLD response is expected in response to a stimulus. Given the 25+ years of successful fMRI studies, there are remarkably few claims in the literature of positive findings in WM. However, it is our experience that often the appearances of BOLD activations in WM are unreported (see below) or even are deliberately removed by adjustment of detection threshold and cluster sizes to reduce the number of “false-positive” results. Indeed, signals from WM may be deliberately regressed out of data analyses as nuisance variables. It should be noted that although blood flow in WM is much less than in GM, their oxygen extraction fractions are comparable [12]. In addition, WM contains a significantly higher glia-to-neuron ratio than GM [13] so the energy requirements are not simply those needed for the efficient propagation of action potentials [11,14]. One recent report argues that a main use of energy in WM is the maintenance of membrane potentials required for proper functioning of oligodendrocytes [11].

Experimentally, it is clearly possible to produce BOLD effects in WM by inducing vasodilation and reducing the level of deoxyhemoglobin in tissue. For example, Fig. 1 shows the effects of a simple hypercapnia challenge on a human subject from which it is seen that the resultant BOLD effect in WM is about 54% that of GM and takes somewhat longer to develop. Even smaller differences in BOLD signal changes (WM ≈ 61%GM) were reported by Iranmahboob et al. [15]. From this it may be inferred that a process that induces increased perfusion with oxygenated blood will alter the MRI signal from WM just as in GM. Moreover, in a resting state, there are significant measurable fluctuations of BOLD signal in WM in the low frequency range 0.01–0.1 Hz characteristic of the signals used to infer functional connectivity in cortex. Fig. 2 shows that the fractional power of variations in the low frequency band in WM varies with echo time and is largely comparable to that in GM, suggesting they share a similar physiological origin and (potentially) significance. Finally there have been several reports that functional tasks reliably induce activations in certain WM regions, especially in recent years [16,17].

Fig. 1.

BOLD responses to a hypercapnia challenge in GM (left) and WM (right) on a normal human subject performed at 3 T. Effect in WM is lower than that of GM and takes longer to develop.

Fig. 2.

Variations of fractional power of low frequency fluctuations in BOLD signals with echo time in GM (red) and WM (blue). Reproduced with permission from [2]. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

An example of the prevailing view of BOLD effects in WM is shown in Fig. 3 taken from an informative and valuable teaching review article in AJNR [18]. The authors illustrate the principles and applications of resting state fMRI by showing those voxels strongly correlated with left Broca’s area, thereby depicting areas engaged in the circuit subserving expressive language in a resting state. The corresponding right side cortical inferior frontal region is part of this circuit and therefore appears as connected as expected, but what is not mentioned in the paper is the clear, central, crescent-shaped area of highly correlated voxels deep within the corpus callosum. This resting state connectivity within WM is often overlooked because such findings are not considered as relevant compared to the main cortical circuits under discussion, or which are the goals of conventional resting state studies. Close examination of numerous other studies in the literature reveals a similar disregard for voxels within WM that pass the threshold criteria for positive findings.

Fig. 3.

Identification of language areas based on seed points in left Broca’s area using resting state fMRI. Reproduced with permission from [17].

2. Resting state correlations in WM

A challenge to this prevailing view was proposed by Ding et al. in 2013 who studied the magnitudes and other characteristics of low frequency signal fluctuations from both GM and WM in a steady state [1]. Fig. 4 shows maps, taken from that report, of temporal correlations in a resting state to seed points in WM for two subjects. It can be seen that the optic radiations of both hemispheres tend to show much higher temporal correlations to the seeds in left optic radiation than the vast majority of other WM or GM voxels. Meanwhile, voxels in the corpus callosum of both hemispheres tend to show much higher temporal correlations to the seed in right corpus callosum than the vast majority of other WM voxels. These high correlations appear to extend over long distances but are confined to specific structures, signifying there are synchronized temporal variations within only these structures. Similar findings were reported by Marussich et al. [19] and Peer et al. [20] who identified segregated components of homogenous WM voxels by using independent component analysis (ICA) and K-means clustering respectively. These components exhibit similar spatial distributions to those of WM tracts. This suggests that WM tracts that provide structural connectivity may also exhibit synchronized BOLD activity in a resting state. By application of these findings, Jiang et al. [21] observed decreased amplitudes of low-frequency spontaneous oscillations in specific WM components in patients with schizophrenia.

Fig. 4.

Distributions of temporal correlations to seed points in left optic radiation (left) and corpus callosum (right) for two normal subjects. The correlations are clearly strongest in the tracts of the optic radiations when the seed point is in the left optic radiation. Voxels in the corpus callosum of both hemispheres tend to show much higher temporal correlations to the seed in right corpus callosum than the vast majority of other WM voxels. This finding suggests that analysis of signals within segmented tracts may increase detection of BOLD signals. Reproduced from [1]; use permitted under the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Ding et al. also calculated the correlations of resting state signals between neighboring WM voxels and found they are measurably anisotropic [2]. For a voxel at the center of a 3 × 3 × 3 volume there are 26 nearest neighbors so that in a resting state there are 26 direction-dependent correlation coefficients. These were found to be unequal in WM but they could be fit to a 3 × 3 tensor in much the same manner as diffusion coefficients for different gradient directions may be reduced to a diffusion tensor (DTI) [22]. The resultant Functional Correlation Tensor (FCT) from resting state BOLD signals may then be treated in similar fashion as DTI tensors - for example, their principal eigenvalues define dominant directions, and quantities analogous to the fractional anisotropy (FA) are readily derived. Wang et al. have observed that the average FA of resting-state correlations along WM tracts in sensorimotor system is significantly correlated with clinical scores in patients with pontine strokes [23]. Chen et al. [24] have expanded the FCT to a dynamic FCT (dFCT). A quantitative measurement derived from the dFCT, namely, dynamic FA, was demonstrated to be an effective feature in recognizing mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The FCTs may be used for tractography. In general the FCT-defined tracts follow WM tracts defined by DTI. Fig. 5 shows a direct comparison of DTI and FCT results for a single brain slice, while Fig. 6 shows the directional ellipsoids for single voxels in the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum and the cingulum. FCT tensor-derived ellipsoids in GM appear isotropic whereas those in WM have a clear, prolonged appearance.

Fig. 5.

The top row was obtained without any diffusion weighting, using only correlations in resting state fluctuations - functional correlation tensors, at four different TEs. The bottom row shows functional correlation tensors constructed from M0 and R2* images, diffusion tensors and a derived FA map. Reproduced with permission from [2].

Fig. 6.

Spatio-temporal functional correlation tensors (FCTs) and diffusion tensors in the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum and the cingulum. From left to right columns are T1-weighted images, FCTs in the boxed region of the left column, and diffusion tensors in the same region. Top to bottom rows are the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum and the cingulum respectively. The pathways formed by the FCTs were grossly consistent with those revealed by diffusion tensors (red arrows). Reproduced with permission from [2]. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Although FCTs appear to align with DTI data, they also have several limitations. The use of only nearest-neighbor voxels makes FCTs sensitive to noise. Furthermore, adjacent voxels tend to have higher correlations than diagonal voxels, resulting in orientation-related biases. Finally, the tensor model restricts functional correlations to an ellipsoidal bipolar-symmetric shape, and precludes the ability to detect more complex functional orientation distributions (FODs). In light of these limitations, Schilling et al. introduced High-Angular-Resolution Functional-correlation Imaging (HARFI) to address these issues [3]. In the same way that high-angular-resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI) techniques provide more information than diffusion tensors, they showed that the HARFI model is capable of characterizing complex FODs expected to be present in WM. They demonstrated that a more complete radial and angular sampling strategy eliminates orientation biases present in tensor models, that HARFI FODs are able to reconstruct known WM pathways, and that they allow asymmetric “bending” and “fanning” distributions of tracts. Their results suggest the HARFI model could be a robust, new way to evaluate anisotropic BOLD signal changes in WM, and that other analytic approaches are also worth investigation.

3. Task-induced BOLD activations in WM

The lack of successful reports of reliable detection of task-related WM BOLD activations suggests that conventional methods used to analyze functional images that are optimized for GM may not be appropriate for WM. To that end, we have considered modifications to analyses that significantly improve the rate of detection of BOLD signal changes in WM. First, in conventional analyses of BOLD data, it is usual to identify a volume of interest or voxel cluster over which to average the MRI signal in order to maximize signal to noise ratio (SNR). Usually the voxel cluster is a spherical or cubic volume centered around a voxel of maximal change during a task. Isotropic smoothing producers a similar increase in SNR. In GM such a volume may be appropriate, but in WM we instead opted to integrate the MRI signal from individual WM tracts segmented from diffusion tensor images. The assumption of any clustering technique is that the voxels combined in a cluster exhibit a common response to stimuli, and we hypothesized that each WM tract contains 100s or 1000s of voxels which share the same function. The WM tracts can be obtained by segmentation of high resolution DTI images. A result is shown in Fig. 7 taken from Wu et al. [4] in which the BOLD responses of both a cortical volume and associated WM tract are both shown to exhibit a clear periodic response that parallels the modulation of the stimulus (in this case a simple stimulation of the palm).

Fig. 7.

Temporal variations of BOLD signals in S1, along the WM tract connecting thalamus and S1, along the tract connecting thalamus and pons, and background, averaged across twelve subjects. Red: task blocks. Blue: BOLD responses. Reproduced with permission from [4]. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

A second essential strategy is based on the observation that WM hemodynamic changes may lag and take longer than cortical responses so that the conventional hemodynamic response function (HRF) used in e.g. general linear models for analyzing fMRI data may not be appropriate. Rather than assume such a function, for a periodic block design task it is logical to postulate that the BOLD response will also be periodic with a strong component at the fundamental task frequency irrespective of other components. A simple Fourier transform of the time varying signal can thus be used to produce a response activation map based on the signal amplitude at the fundamental frequency. Fig. 8 and Fig. 9 show time series of BOLD signals and their Fourier spectra along with a map of the voxels showing a strong component at the fundamental frequency in response to a simple alternating visual stimulus [5]. This approach does not need to assume any particular form for the HRF other than it is relatively short compared to the period of the task.

Fig. 8.

Time series of BOLD signals (top and middle rows) and their Fourier spectrua (bottom rows) in response to a simple alternating visual stimulus. Reproduced with permission from [5].

Fig. 9.

Distributions of the magnitude at the stimulus frequency in BOLD signals in WM and GM in response to a simple alternating visual stimulus. The MSF is thresholded at 0.4 MMSF for both WM and GM. Reproduced with permission from [5].

4. Hemodynamic response function in WM

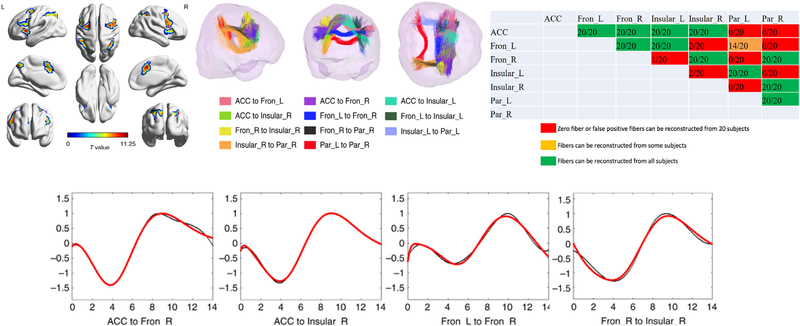

Event-related designs are another important class of fMRI experiments in which the HRF plays a central role as the effective impulse response of the brain. The HRF may in principle be derived from appropriate event-related studies. Li et al. [6] implemented a paradigm to identify areas of the brain activated by an event-related version of the Stroop word-color interference task [25]. Their goal was to use the Stroop task to robustly activate multiple, distributed brain sites as first shown by Leung et al. in 2000 [26]. Performance of the Stroop specifically activated 7 main regions - the anterior cingulate (ACC), insular, inferior and middle frontal regions (FRON), and parietal gyri (PAR) as shown in Fig. 10. From DTI, WM tracts that could be reliably traced in all of 20 subjects between the 7 activated GM regions (11 of 21 possible connections were analyzed) as shown in Fig. 10, were identified, and the event-related BOLD waveforms in each of those were then analyzed. While several tracts showed responses with continuous increases to a single peak similar to a stretched version of the GM response, other areas showed a distinct biphasic waveform with a pronounced negative dip followed by a positive peak. In cortex a negative dip in BOLD waveforms has been difficult to reliably detect though it is postulated to represent a temporary increase in deoxyhemoglobin from increased oxygen usage prior to the arrival of increased arterial blood. In WM, where the vascular response is smaller and slower, there appear to be larger negative dips, and the HRF is variable across tracts. The difference between the WM HRF and that assumed in most analyses of fMRI studies explains some of the lack of sensitivity to WM activations in many previous studies.

Fig. 10.

Top Left: Cortical areas activated by event-related Stroop test detected using standard GLM. Top middle: Major tracts traced between ROIs in activation map using DTI. Top right: Matrix of 7 regions identified along with indicators (colors) of regions between which WM fibers could be tracked in 20 subjects. Lower: the time courses averaged over multiple epochs of BOLD signals in 4 WM tracts from 20 subjects. Red line shows fit to double gamma variate function. Control WM tracts showed no significant changes and flat responses. Reproduced from [6]; use permitted under the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

5. Relationship of WM BOLD effects and neural activity

Given the evidence that both task-evoked and resting state BOLD signals can be detected in WM, a natural question is whether, by analogy to GM, resting state signals are related to neural activity or information processing within the brain. Evidence for this may be adduced from the fact that in anesthetized monkey brains, the power of WM resting state signal fluctuations varies with the level of anesthesia in identical manner to the BOLD signals from cortical areas. In studies of anesthetized squirrel monkeys, Wu et al. [7] reported that the fractional power (0.01–0.08 Hz) of BOLD signal fluctuations in WM was between 60 and 75% of the level in GM, and that as levels of isoflurane increased from 0.5% to 1.25%, the power in both GM and WM low frequencies decreased monotonically in very similar manner. Furthermore, the distribution of fractional anisotropy values of the functional tensors in WM were significantly higher than those in GM and the functional tensor eigenvalues decreased with increasing level of anesthesia. These results suggest that as anesthesia level changes baseline neural activity, WM signal fluctuations behave similarly to those in GM, and functional tensors in WM are affected in parallel.

A demonstration of the relationship between activity in GM cortical regions and WM tracts was reported in Wu et al. [4] who studied the correlations in resting state BOLD signals between WM tracts and GM volumes known to be engaged in specific motor or sensory responses. For example, a group of subjects performed conventional block activation studies with subject finger tapping to identify GM primary motor cortices. Then, DTI was used to identify WM tracts between those regions and the thalamus. Subsequently, resting state acquisitions of whole brain were acquired. Wu et al. then examined the values of the resting state correlations between the GM motor cortices and the WM thalamo-cortical tracts and compared them to correlations of GM motor cortices to all other WM regions both at rest and during continuous finger tapping. The correlations were much larger between GM and the thalamo-cortical WM tracts than any other WM regions, they increased with task demand, and were much greater on the contralateral side of the brain. These results were consistent with the postulate that WM BOLD signals are related to the “driving” cortical activity to which they connect both in a resting state and during a stimulus.

6. WM BOLD increases with task parameters parallel to GM BOLD

Further evidence that WM BOLD signals reflect neural activity is provided by tasks that modulate the BOLD signals in GM in parametric fashion, and in which there are corresponding changes in WM. Fig. 11 shows the results of a preliminary study in which images were acquired during simple visual stimulations with a flickering checker board in a block design protocol (20 s blocks). On successive runs the flickering rate of the checker board was varied from 2 to 14 Hz. Previous studies have shown that primary visual areas show a graded BOLD response with changing frequencies that typically peaks around 8 Hz [27]. Fig. 11 shows the average magnitude of the fMRI signal changes at the block frequency in GM and WM, obtained by Fourier transform of their time-varying signals, as well as the variation with flicker frequency of the signal in GM and WM areas. Clearly the WM response follows the GM neuronal sensitivity to flicker frequency, consistent with the WM signal being strongly coupled to GM activity. It should be emphasized that this correspondence is unlikely to be caused by drainage effects from the GM because cortical drainage occurs largely outwards while the WM veins drain inwards and there is no vascular communication between them [28].

Fig. 11.

Variation of BOLD signal with flicker frequency. Upper left shows BOLD responses to flickering checker board (average of 12 subjects) in visual cortex. Upper right shows signal variation in WM and GM at different block presentation frequencies. Lower shows relative time series of signal changes in WM for different frequencies.

7. Functional connectivity matrices

To further test the hypothesis that BOLD signals in WM tracts are directly related to neural activity within cortical regions with which they share a functional role, Ding et al. [8] acquired and analyzed diffusion tensor and BOLD images from a group of healthy human subjects in a resting state at 3T. They then looked for correlations between specific parcellated GM volumes and segmented WM tracts. The images were spatially normalized into the common MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) space [29]. 48 WM bundles were defined via DTI using the Johns Hopkins atlases [30], and 84 Brodman’s areas (BA) were defined in GM using the PickAtlas tool [31]. Pearson correlation coefficients were then calculated for MRI signals between each pair of WM bundle and BA, which produced a functional correlation matrix (FCM) showing their resting state relationships. The average temporal correlations in a resting state between BOLD signals in 48 WM bundles and 84 GM regions are shown in Fig. 12, in which each element is the correlation coefficient (CC) between a pair of WM and GM regions averaged across 12 subjects. It is quite apparent that the variations of correlations are not random, but rather manifest as patterns of horizontal stripes, suggesting that certain WM bundles exhibit overall greater temporal correlations with GM. There were also negative correlations between some of the WM bundles and GM regions. Most notably, the left tapetum (TAP) had quite pronounced negative correlations with most of the GM regions (mean CC < −0.3) (consistent with a 180 degree shift in their temporal response waveforms in a block design). The patterns of horizontal stripes suggest the existence of synchronous BOLD responses within segmented WM and GM volumes in the human brain in a resting state.

Fig. 12.

Matrix of temporal correlations between BOLD signals in WM bundles (vertical axis) and GM regions (horizontal axis) averaged over 12 young adults. The data were thresholded at mean CC > 0.3. Reproduced from [8] (PNAS authors need not obtain permission for using their original figures or tables in their future works).

Ding et al. further analyzed 3T resting state fMRI data from 172 subjects in the Young Adult Study in the Human Connectome Project [32]. GM region masks were obtained from the preprocessed ROIs, including 68 sulci and gyri, which were automatically segmented on structural images in native space and then transformed to MNI space. Meanwhile, WM region masks were created from the JHU ICBM-DTI-81 WM atlas, including 48 deep WM bundles. Resting state fMRI signals were averaged across each of the GM and WM regions to produce a mean time series, which was used to calculate pairwise temporal CCs between GM regions and WM bundles. The CC maps across all 172 subjects were averaged and thresholded at 0.3 (Fig. 13). These data reproduced the earlier, smaller study and suggest strongly that comparisons of the functional correlation matrices from different groups would be worthwhile. For example, it is reasonable to hypothesize that patterns of GM-WM correlations will be altered during brain development or degeneration, and may provide a novel way to characterize brain functional changes with different disorders. A similar example was reported by Ji et al. [33] where a functional network was modeled by pair-wise correlation between WM ROIs and yielded topological measurements that were correlated to dysfunction of patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Fig. 13.

Matrix of correlations>0.3 for 48 WM bundles (vertical axis) vs 68 cortical regions (horizontal axis) averaged over 172 young adults.

8. Conclusions

The studies summarized above, in combination with other reports, suggest strongly that task-evoked and resting state signals in WM appear to be BOLD effects that reflect hemodynamic changes associated with neural activity within WM and/or adjacent cortical areas. In a resting state, WM signal fluctuations behave in similar fashion as those from GM as anesthesia increases and baseline neural activity decreases. WM tracts show a smaller and slower hemodynamic response to a stimulus than GM areas. Conventional methods for detecting activity in WM in block or event-related studies are insensitive partly because they employ inappropriate ROIs for clustering voxels and an inappropriate HRF.

Resting state correlations between voxels in WM are detectable and anisotropic and can be described by a 3 × 3 tensor or other means. Functional Correlation Tensors represent a functional connectivity within white matter that is similar to the structural connectivity provided by DTI but is obtainable without using diffusion gradients. Signals from specific WM tracts correlate most with signals from cortical regions to which they are connected, and those correlations increase during a task. Functional Correlation Matrices can be constructed for a whole brain which relate resting state signals in different WM tracts to specific GM cortical volumes.

The brain is known to be organized in multiple levels, from single neurons to ensembles, columns and layers, circuits, modules and systems. Different types of function emerge from these different levels of structure, so an understanding of how structure and function are related and integrated is likely to provide greater insight into important aspects of how the brain performs. The precise biophysical basis of the BOLD changes seen in WM is presently not understood. BOLD signals in WM may represent vascular responses to the demands of signal transduction intrinsic to WM, or they may potentially be induced by a physical coupling to vascular changes in cortex. In addition, the interpretations of WM correlations are not clear. However, similar concerns regarding BOLD effects in GM remain largely valid despite 25 years of acceptance and widespread use of fMRI. While evidence has accumulated that BOLD evoked responses usually correspond to increased neural activity as measured by e.g. electrophysiology, not all changes in BOLD signals are readily correlated with corresponding electrical signals and vice versa, while their quantitative relationships to specific levels of neurotransmission and metabolism have received scant attention. There are also fundamental uncertainties still about the interpretation of functional connectivity derived from BOLD correlations, and how these reflect activity in neural circuits in a resting state. While further investigations of these underlying phenomena are worthwhile, it seems inconsistent to accept uncertainties about the origins and meaning of GM BOLD signals while dismissing the potential value of WM signals because of similar uncertainties. From the evidence above we suggest BOLD signals in WM warrant greater scrutiny from the neuroimaging community.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 NS093669 (J.C.G).

References

- [1].Ding Z, Newton AT, Xu R, Anderson AW, Morgan VL, Gore JC. Spatio-temporal correlation tensors reveal functional structure in human brain. PLoS One 2013;8:e82107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ding Z, Xu R, Bailey SK, Wu T-L, Morgan VL, Cutting LE, et al. Visualizing functional pathways in the human brain using correlation tensors and magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2016;34:8–17. 10.1016/j.mri.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schilling KG, Gao Y, Li M, Wu T-L, Blaber J, Landman BA, et al. Functional tractography of white matter by high angular resolution functional-correlation imaging (HARFI). Magn Reson Med 2019;81:2011–24. 10.1002/mrm.27512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wu X, Yang Z, Bailey SK, Zhou J, Cutting LE, Gore JC, et al. Functional connectivity and activity of white matter in somatosensory pathways under tactile stimulations. Neuroimage 2017;152:371–80. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Huang Y, Bailey SK, Wang P, Cutting LE, Gore JC, Ding Z. Voxel-wise detection of functional networks in white matter. Neuroimage 2018;183:544–52. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li M, Newton AT, Anderson AW, Ding Z, Gore JC. Characterization of the hemodynamic response function in white matter tracts for event-related fMRI. Nat Commun 2019;10:1140. 10.1038/s41467-019-09076-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wu T-L, Wang F, Anderson AW, Chen LM, Ding Z, Gore JC. Effects of anesthesia on resting state BOLD signals in white matter of non-human primates. Magn Reson Imaging 2016;34:1235–41. 10.1016/j.mri.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ding Z, Huang Y, Bailey SK, Gao Y, Cutting LE, Rogers BP, et al. Detection of synchronous brain activity in white matter tracts at rest and under functional loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2018;115:595 LP–600. 10.1073/pnas.1711567115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Helenius J, Perkiö J, Soinne L, Østergaard L, Carano RAD, Salonen O, et al. Cerebral hemodynamics in a healthy population measured by dynamic susceptibility contrast Mr imaging. Acta Radiol 2003;44:538–46. 10.1034/j.1600-0455.2003.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rostrup E, Law I, Blinkenberg M, Larsson HBW, Born AP, Holm S, et al. Regional differences in the CBF and BOLD responses to hypercapnia: a combined PET and fMRI study. Neuroimage 2000;11:87–97. 10.1006/nimg.1999.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Harris JJ, Attwell D. The energetics of CNS white matter. J Neurosci 2012;32:356 LP–371. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3430-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:676–82. 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hofmann K, Rodriguez-Rodriguez R, Gaebler A, Casals N, Scheller A, Kuerschner L. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in grey and white matter regions of the brain metabolize fatty acids. Sci Rep 2017;7:10779. 10.1038/s41598-017-11103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Engl E, Attwell D. Non-signalling energy use in the brain. J Physiol 2015;593:3417–29. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Iranmahboob A, Peck KK, Brennan NP, Karimi S, Fisicaro R, Hou B, et al. Vascular reactivity maps in patients with gliomas using breath-holding BOLD fMRI. J Neuroimaging 2016;26:232–9. 10.1111/jon.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mazerolle EL, Gawryluk JR, Dillen KNH, Patterson SA, Feindel KW, Beyea SD, et al. Sensitivity to white matter fMRI activation increases with field strength. PLoS One 2013;8:e58130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gawryluk JR, Brewer KD, Beyea SD, D’Arcy RCN. Optimizing the detection of white matter fMRI using asymmetric spin echo spiral. Neuroimage 2009;45:83–8. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lee MH, Smyser CD, Shimony JS. Resting-state fMRI: a review of methods and clinical applications. Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:1866 LP–1872. 10.3174/ajnr.A3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marussich L, Lu K-H, Wen H, Liu Z. Mapping white-matter functional organization at rest and during naturalistic visual perception. Neuroimage 2017;146:1128–41. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Peer M, Nitzan M, Bick AS, Levin N, Arzy S. Evidence for functional networks within the human Brain’s white matter. J Neurosci 2017;37:6394–407. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3872-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jiang Y, Luo C, Li X, Li Y, Yang H, Li J, et al. White-matter functional networks changes in patients with schizophrenia. Neuroimage 2018. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J 1994;66:259–67. 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang J, Yang Z, Zhang M, Shan Y, Rong D, Ma Q, et al. Disrupted functional connectivity and activity in the white matter of the sensorimotor system in patients with pontine strokes. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49:478–86. 10.1002/jmri.26214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen X, Zhang H, Zhang L, Shen C, Lee S-W, Shen D. Extraction of dynamic functional connectivity from brain grey matter and white matter for MCI classification. Hum Brain Mapp 2017;38:5019–34. 10.1002/hbm.23711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 1935;18:643–62. 10.1037/h0054651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Leung H-C, Skudlarski P, Gatenby JC, Peterson BS, Gore JC. An event-related functional MRI study of the stroop color word interference task. Cereb Cortex 2000;10:552–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Thomas CG, Menon RS. Amplitude response and stimulus presentation frequency response of human primary visual cortex using BOLD EPI at 4 T. Magn Reson Med 1998;40:203–9. 10.1002/mrm.1910400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Milla DS. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies: current concepts. 2009. p. 271–83. 10.1002/ana.21754. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [29].Evans AC, Collins DL, Mills SR, Brown ED, Kelly RL, Peters TM. 3D statistical neuroanatomical models from 305 MRI volumes. 1993 IEEE Conf. Rec. Nucl. Sci. Symp. Med. Imaging Conf vol.3 1993. p. 1813–7. 10.1109/NSSMIC.1993.373602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Oishi K, Faria A, Jiang H, Li X, Akhter K, Zhang J, et al. Atlas-based whole brain white matter analysis using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping: application to normal elderly and Alzheimer’s disease participants. Neuroimage 2009;46:486–99. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage 2003;19:1233–9. 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Van Essen DC, Ugurbil K, Auerbach E, Barch D, Behrens TEJ, Bucholz R, et al. The human connectome project: a data acquisition perspective. Neuroimage 2012;62:2222–31. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ji G-J, Ren C, Li Y, Sun J, Liu T, Gao Y, et al. Regional and network properties of white matter function in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2019;40:1253–63. 10.1002/hbm.24444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]