Abstract

The anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) antibody Cetuximab (CTX) has demonstrated limited anti-cancer efficacy in cells overexpressing EGFR due to activating mutations in RAS in solid tumours, such as pancreatic cancer. The utilisation of antibodies as targeting components of antibody-drug conjugates, such as trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla), demonstrates that antibodies may be repurposed to direct therapeutic agents to antibody-resistant cancers. Here we investigated the use of CTX as a targeting agent for camptothecin (CPT)-loaded polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) directed against KRAS mutant CTX-resistant cancer cells. CPT was encapsulated within poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs using the solvent evaporation method. CTX conjugation improved NP binding and delivery of CPT to CTX-resistant cancer cell lines. CTX successfully targeted CPT-loaded NPs to mutant KRAS PANC-1 tumours in vivo and reduced tumour growth. This study highlights that CTX can be repurposed as a targeting agent against CTX-resistant cancers and that antibody repositioning may be applicable to other antibodies restricted by resistance.

Keywords: Cetuximab, camptothecin, PLGA, nanoparticles, pancreatic cancer, KRAS

Background

The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is a cell surface receptor normally expressed in many different cell types, including fibroblast, epithelial and mesenchymal cells. EGF, the natural ligand for EGFR, binds to the receptor, resulting in the activation of survival and cell proliferation pathways, one of which is the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway. EGFR overexpression is linked to progression of many different cancer types, such as colorectal, lung and pancreatic cancers1. Additionally, both receptor and downstream signalling proteins are susceptible to mutations that lead to dysregulation of EGFR signalling pathways and result in aggressive cancer types that have a poor prognosis2.

The anti-proliferative monoclonal antibody Cetuximab (CTX) is used clinically to inhibit EGFR signalling by blocking binding of EGFR ligands to the receptor3,4. CTX can be used for the treatment of numerous EGFR-positive tumours, including colorectal and lung cancers. CTX response in these cancer types can be predicted based upon expression or mutational status of biomarker proteins downstream of EGFR, such as BRAF5 and proteins within the RAS family such as Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS)6. In patients inflicted with tumours expressing wild-type KRAS, CTX can exert an anti-cancer effect alone or in combination with chemotherapies7. However, tumours that express mutated KRAS, which account for up to 45 % of colorectal cancers8, 25 % of non-small cell lung cancers9 and 95 % of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC)10, are resistant to CTX therapy11,12.

An emerging strategy is to repurpose antibodies as selective targeting agents for delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to antigen-expressing cancers that exhibit antibody resistance. For example, T-DM1 (Kadcyla), a Herceptin-conjugated maytansinoid, is an FDA-approved antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for Her2-positive refractory metastatic breast cancer. In clinical trials, T-DM1 has also demonstrated efficacy in patients with tumours that have acquired resistance to Herceptin13,14,15, demonstrating the potential for antibody targeting of drug payloads. However, ADCs possess several drawbacks, including toxicity to non-cancer tissues, and bystander toxicity resulting from systemic or extracellular release of the exceptionally toxic drugs employed. Antibody-conjugated nanoparticles (NPs) may provide an exciting alternative that circumvents certain ADC limitations. For example, NPs can encapsulate and protect the drug from metabolic degradation and immune clearance by encapsulation. They also have a higher cargo capacity than ADCs which increases the amount of drug delivered to the tumour, and achieve much higher drug-to-antibody ratios (DARs), thus allowing drugs with lower potency to be administered which reduces toxicities to non-cancerous cells16,17.

Here, we demonstrate that CTX can be repurposed as the targeting component of an antibody-nanoparticle conjugate in order to enhance the delivery of camptothecin (CPT)-loaded NPs to CTX-resistant pancreatic cancer cells which express mutated K-Ras. In addition, the efficacy of this nanoformulation is demonstrated in mutant K-Ras colorectal and lung cancer cell lines. This comprehensive study involving different CTX-resistant cancer types highlights a generalizable approach that can be employed across different cancers which exhibit antibody resistance.

Methods

Preparation and characterisation of NPs.

NPs were synthesised using the single emulsion solvent evaporation method described previously18 using 15 mg PLGA 502H (Sigma Aldrich) and 5 mg PEG-PLGA-NHS (Akina Polyscitech AI064; MW ~ 17000:3000 Da) in a 75 %: 25 % ratio. For cytotoxicity studies, 100 μg of CPT was added to 1 mL dichloromethane (DCM), whereas 666 μg CPT was added for drug release studies or in vivo studies. For NP binding assays, CPT was replaced by 100 μg of rhodamine 6G. Alternatively, as a control formulation, blank NPs contained neither drug nor fluorophore. 50 μg/mL of CTX per mg polymer was added to the NP formulation in MES buffer. NPs were stirred at 80 rpm at room temperature for 2 hours to allow protein conjugation, and unbound antibody was removed by centrifugation at 15000 rcf for 15 minutes, followed by resuspension in PBS. CTX conjugation to NPs was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Scientific, UK), using CTX as a protein standard in solution containing blank-NPs to account for polymer interference. CPT encapsulation was assessed in the NP pellet by measurement of CPT fluorescence at 330Ex/460Em. A CPT standard curve was used which contained blank-NPs to account for polymer interference. NP physical characteristics were analyzed in deionised water by dynamic light scattering using the NanoBrook Omni Particle Sizer and Zeta Potential Analyser, and by Scanning Electron Micrography using a FEI quanta FEG environmental scanning electron microscope.

In vitro CPT release was assessed in Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes having a 7 kDa pore size (Thermo Scientific, UK). 15 mg CPT-loaded polymer in 1 mL PBS were dialyzed against 29 mL of PBS/ 2 % Tween-80 (v/v) while shaking (180 rpm) at 37 °C. At the indicated time points, 1 mL of release medium was collected and analysed for CPT content, and concentrations were determined by comparison to a CPT standard by measuring fluorescence at 330Ex/460Em.

SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis.

1 mg non-conjugated or CTX-conjugated NPs were boiled in 10x Laemmli buffer for 5 minutes before electrophoretic separation on a reducing pre-cast Novex WedgeWell 4–20 % Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen, UK).

Cell culture.

HCT116 (donated by the Volgelstein laboratory), A549 (ATCC), HKH-2 (donated by the Sasazuki laboratory where the cell line was generated19), HCC827 (ATCC) and PANC-1 (ATCC) cell lines were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS) (Life Technologies, UK), and BxPC-3 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10 % FCS.

Cell surface EGFR expression.

To measure EGFR cell surface expression, cells were stained with either 1 μg FITC-conjugated anti-EGFR antibody (Santa Cruz sc: 120) or 1 μg FITC-conjugated IgG2a Isotype control (Santa Cruz sc: 2856) for 45 minutes at 4 °C in PBS/ 5 % FCS. Cells were washed twice in 5 mL of PBS / 5% FCS and then once in 5 mL of PBS. Samples were resuspended in 300 μl of PBS and analysed by FACS using either BD LSRII or BD Accuri C6 Plus flow cytometers (BD, UK).

Measurement of NP binding to the cell surface.

Cells were seeded at 4 × 104 cells per well in a black 96-well plate or 2 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate. Prior to NP treatment, cells were incubated in serum-free media, chilled to 4 °C, and treated with 25 μg/mL fluorescent rhodamine-6G -loaded NPs for different time periods. Cells were then washed three times with ice-cold PBS. For measuring total fluorescence, cells were lysed in 50 μl of 0.2 M NaOH / 0.05 % Triton X-100, and fluorescence was measured at 525Ex/555Em using a plate reader. Fluorescence was also measured by FACS using a BD Accuri C6 plus instrument.

Assessing cell viability.

For free drug treatments, viability was measured by MTT assay. For NP treatments, viability was measured using the Cell Titre-Glo assay (Promega) or by staining with 0.4 % crystal violet and measuring absorbance at 590 nm. Viability was calculated as a percentage cell growth relative to the untreated control.

Assessing colony formation by clonogenic assay.

Cells were seeded at 2.5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. After 1 hour of treatment, the cells were re-seeded at 250 cells per well in triplicate in 6-well plates and were incubated for 11–13 days (cell line-dependent) to allow colonies to form. The cells were then stained with 1 mL of 0.4 % crystal violet for 10 minutes. Colonies of 50 cells or more were counted to assess changes in colony formation.

Cell cycle progression.

Cells were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. After the treatment period, live cells were detached using 1 mL of PBS/ 0.1 % EDTA, combined with detached or dead cells harvested by centrifugation from the supernatant media, and fixed using 1 mL of PBS/ 1 % FCS and 4 mL of ice-cold ethanol for 24 hours. RNase A (Qiagen) digestion was carried out, and then cells were stained with PI and analyzed by FACS using a BD LSR II instrument.

Assessing apoptotic cell death.

Caspase activation was measured using the Caspase-glo 3/7 assay (Promega). Caspase-3/−7 activity was calculated as a fold change relative to untreated controls. Apoptotic cell death after 72 hours was measured by Annexin V and PI staining followed by FACS analysis (BD Accuri C6).

PANC-1 xenograft study.

All in vivo experiments were carried out in accordance with the UK Home Office and approved by Queen’s University Belfast Ethical Review Committee. 5×106 PANC-1 cells were implanted subcutaneously onto both flanks of 9 week old female severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (Envigo, UK) using matrigel (Corning, UK) at a 1:1 ratio of cells to matrigel. When the xenografts reached an average volume of 100 mm3, treatment was initiated with intravenous (iv) injections of 2 mg (100 mg/kg) of NPs or controls per mouse (corresponding to 1.9mg/kg CPT and 3.57 mg/kg CTX per mouse). Mice received five iv treatments throughout the study and were euthanized when tumour volumes reached 1200 mm3.

H&E staining.

The tumours from the xenograft study were excised and fixed in 10 % formalin prior to paraffin-embedding. Tumour sections (6 μm) were stained with Harris H&E (Fisher Scientific). Images were taken using an Olympus BH2 microscope equipped with DP25 camera and × 10 objective lens.

Data analyses.

Data was plotted and statistical analyses were carried out using Prism 8 software (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The one way or two way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to analyse statistical significance between several groups respectively. Significant differences are denoted with *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. FACS data analysed using FlowJo 10 software (FlowJo LLC, USA).

Results

Synthesis and characterization of antibody-targeted PEGylated PLGA NPs.

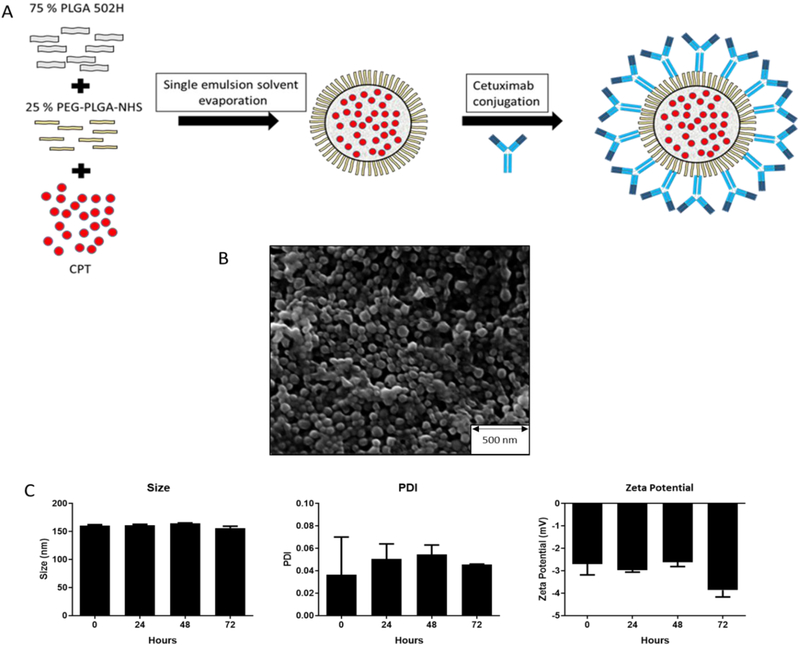

We formulated CPT-loaded PLGA NPs and functionalized them with CTX by reacting amine moieties within the antibody with surface-exposed NHS groups on the PEG corona of the NPs (Fig 1A). CPT, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, was selected as the model drug in this study because it is readily entrapped within polymeric nanoparticulates20 and topoisomerase inhibitors are clinically relevant for pancreatic21 and other cancers. The physical characteristics of the nanospheres formulated by this approach were analysed (Table 1); the monodisperse particles were approximately 200 nm, consistent with particle formulations that we have previously developed to facilitate passive tumour targeting20,22. CPT was entrapped because of its inherent hydrophobicity, and CTX was successfully conjugated to the NP corona (Table 1). Covalent attachment of CTX to the NPs was confirmed by gel electrophoresis comparing conjugation to PEG-PLGA-NHS NP over non-NHS functionalised control NPs. After incubation with CTX, the isolated NPs were subjected to denaturing SDS-PAGE. When CTX was incubated with the NHS functionalised NPs, the co-purified antibody chains observed on the gel appeared in a smear-like pattern, consistent with conjugation with the PEG-PLGA-NHS polymer, retarding its migration on the gel. This effect was not observed with in the absence of NHS, indicating no covalent attachment (Fig S1). NP size was also confirmed by SEM analysis (Fig 1B). The particles were analysed for stability over 72 hours in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FCS, and showed no significant changes in size, polydispersity or surface corona charge (zeta charge) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Synthesis and characterization of antibody-targeted PEGylated PLGA NPs.

(A) Schematic overview of the development of CTX-CPT-NPs. (B) SEM image of PLGA-NPs. (C) Stability analysis of PLGA-NPs incubated at 37 °C in DMEM over 72 hours; mean ± s.e.m (n=2).

Table 1. Characterisation of PLGA NPs with or without CPT loading, before and after CTX conjugation, for in vitro validation.

Mean ± s.e.m. (n=3); measured in deionised water (dH2O). PDI = polydispersity index

| NP formulation | Size (nm) | PDI | Zeta potential (mV) | CPT loading (μg/mg) | CTX conjugation (μg/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank-NP | 170.7 ± 13.6 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | −13.6 ± 2.25 | NA | NA |

| CPT-NP | 202.6 ± 24 | 0.064 ± 0.03 | −11.89 ± 2.3 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | NA |

| CTX-NP | 192 ± 4.3 | 0.055 ± 0.03 | −11.0 ± 2.66 | NA | 30.2 ± 3.92 |

| CTX-CPT-NP | 210 ± 21.9 | 0.083 ± 0.02 | −9.4 ± 1.98 | 1.19 ± 0.13 | 11.05 ± 4.4 |

Evaluation of EGFR-positive cell lines for sensitivity to CTX.

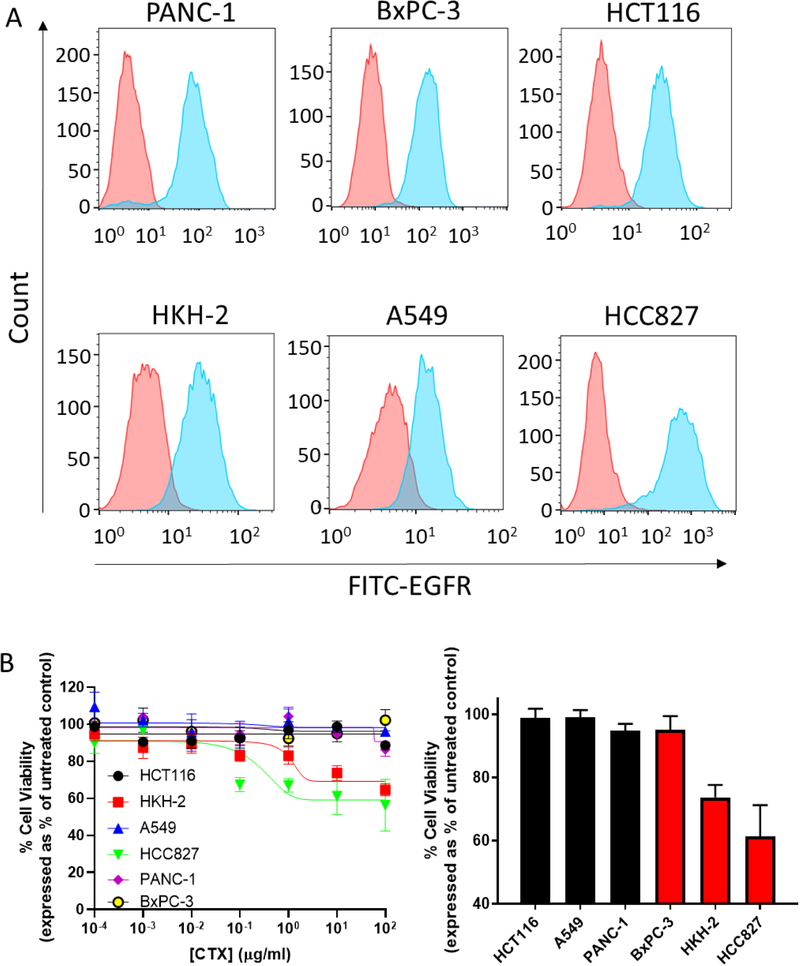

Having successfully developed EGFR-targeted nanoparticles loaded with CPT, we next selected a panel of cell line models in which to validate this nanoformulation. A range of tumour cell lines having differential KRAS mutational status (Table S1) were examined for their expression of EGFR. We selected three mutant KRAS cell lines (PANC-1 cells [pancreas]23, HCT116 cells24 [colon] and A549 cells [lung]25) and three wild-type KRAS cell lines from the same tumour sites (BxPC-3 cells [pancreas]26, HKH-2 cells [colon]27 and HCC827 cells [lung]28), and analysed surface expression of EGFR by FACS. All cell lines tested were positive for EGFR (Figure 2A), indicating the potential to target these cell lines with the CTX-conjugated nanoformulation.

Figure 2. Evaluation of EGFR-positive cell lines for sensitivity to CTX.

(A) EGFR cell surface expression of cancer cell lines. Red histogram signifies antibody-stained isotype control cells; blue histogram signifies EGFR antibody-stained cells. Data are representative of three individual experiments. Data were analysed using FlowJo 10 software. (B) Left graph: CTX concentration-response curves after 72 hours using the MTT assay. Right graph: cell viability after 72 hour exposure to 10 μg/mL CTX. Black bars represent mutant KRAS cell lines and red bars represent wild-type KRAS cell lines. Mean ± s.e.m. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

It is well-established that mutations within the EGFR signalling pathway can affect the sensitivity of tumour cells to treatment with antibody-based EGFR inhibitors2. Therefore, we analysed the viability of the cell lines over 72 hours in response to increasing concentrations of CTX. For wild-type KRAS HKH-2 and HCC827 cells, a concentration-dependent reduction in viability was observed following treatment with CTX. In contrast, CTX did not affect the growth of mutant KRAS cell lines PANC-1, HCT116 and A549 at the concentrations examined (Figure 2B). These KRAS-dependent effects were also observed in a time course study employing a fixed concentration of CTX (Fig S2). Taken together, these findings indicate that KRAS contributes to CTX resistance. Clear demonstration of the role of KRAS is revealed in the comparison of HCT116 and HKH-2, which are isogenically paired cell lines; the former possessing the mutant KRAS allele and the latter has this allele deleted from its genome19. Interestingly, BxPC-3, which also expresses wild-type KRAS, exhibited a CTX-resistant phenotype. Because of their inherent resistance to CTX and high expression of the target protein EGFR, PANC-1, HCT116, A549 and BxPC-3 (despite expressing wild-type KRAS) cells were selected for subsequent studies with the EGFR-targeted nanoparticles.

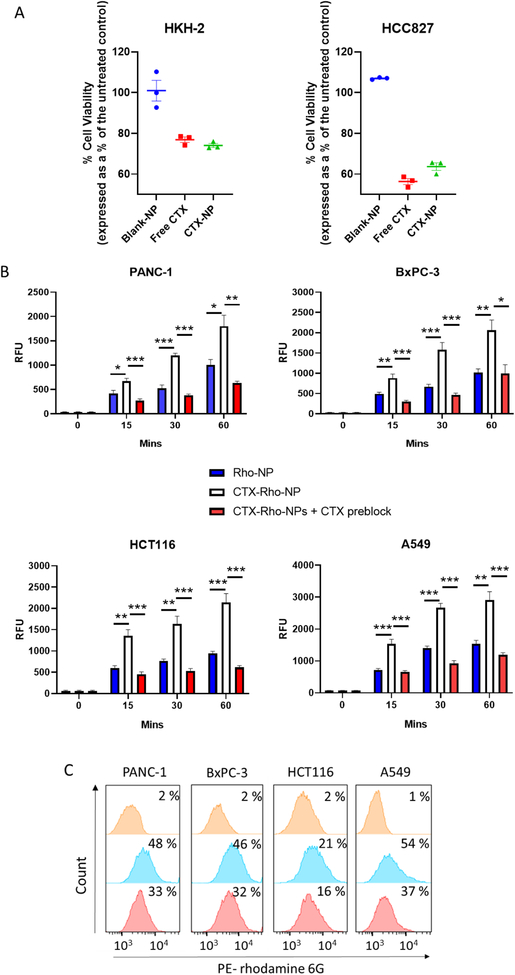

CTX nanoconjugation enhances NP targeting to the cell surface through EGFR interaction.

Before assessing NP binding by CTX, it was important to confirm that conjugation to NPs did not affect the bioactivity of the antibody. The anti-proliferative activity of CTX-NPs was compared to that of free CTX on KRAS wild-type cell lines HKH-2 and HCC827. The cells were exposed to an equal concentration of CTX either conjugated to NPs or as free antibody and an equivalent concentration of blank-NPs. After 72 hours, it was observed that CTX-NPs reduced viability to approximately the same extent as free CTX, highlighting that the bioactivity of the antibody remained intact (Fig 3A). Next, the ability of the antibody-nanoparticle conjugate to bind to CTX-resistant cell lines was examined using fluorescent nanoparticles containing rhodamine 6G to quantify nanoparticle binding to cells. Physical characterisation of CTX-conjugated rhodamine NPs (CTX-Rho-NPs) revealed characteristics similar to the drug-containing NPs of Table 1, with a monodisperse formulation having diameters slightly larger than 200 nm, and a negative surface charge (Table S2). CTX conjugation to the NP surface was also comparable to that of CTX-CPT-NPs. NP binding experiments at three different time points revealed that cell lines treated with CTX-conjugated NPs (CTX-Rho-NPs) exhibited higher fluorescence than cells treated with non-targeted NPs (Rho-NPs), indicating increased NP binding (Fig 3B). Simultaneously, in order to investigate the antibody-dependence of nanoparticle binding, cells were treated with free CTX for 15 minutes prior to addition of CTX-Rho-NPs. Pre-treatment with free CTX reduced the binding of CTX-Rho-NPs to all cell lines tested, as evidenced by a significant decrease in fluorescence compared to that obtained in the absence of free antibody. The residual binding of CTX-Rho-NPs in the presence of competing free antibody was approximately the same as the binding observed for non-targeted Rho-NPs. The effects of pre-incubation with free CTX were corroborated by FACS analysis, in which both the fluorescence intensity and percentage of rhodamine-positive cells were reduced when incubation with CTX-Rho-NPs was preceded by incubation with the competing antibody (Fig 3C). These data suggest that free CTX blocked EGFR, thereby preventing binding of the targeted NPs to the cell surface. This finding supports the role of CTX interaction with EGFR as the mechanism for increased cell binding of CTX-NPs.

Figure 3. CTX nanoconjugation enhances NP targeting to the cell surface via EGFR interactions.

(A) HKH-2 and HCC827 were treated with 10 μg/ml of CTX either conjugated to NPs or as free antibody and an equivalent concentration of blank-NPs. After 72 hours, viability was measured by crystal violet staining. Mean ± s.e.m. Data representative of three independent experiments. (B) CTX-resistant ells were pre-incubated in serum-free media to eliminate competition by serum EGF, and subsequently treated with 25 μg/mL Rho-NPs or CTX-Rho-NPs in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL CTX at 4 °C. NPs were washed off at the indicated time points and the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine 6G was measured using a plate reader. Mean ± s.e.m (n=3); statistical significance was established using the two way ANOVA test with Tukey’s post hoc test. (C) Competition of free CTX with cellular binding of CTX-Rho-NPs. CTX-resistant cells were treated for 15 minutes with 25 μg/mL CTX-Rho-NPs in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL free CTX at 4 °C, washed, and subjected to FACS analysis. Inset in each graph shows percentage of rhodamine 6G-positive cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Data analysed using FlowJo 10 software.

To further confirm the EGFR targeting specificity of the NPs, we performed a receptor accessibility assay where PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells were pre-treated with CTX-NPs or control blank-NPs for 20 minutes at 4°C prior to staining with a FITC-labelled EGFR antibody. Both untreated cells and cells pre-treated with blank-NPs showed high EGFR staining, indicating that EGFR was accessible to the EGFR antibody. However, pre-treatment of cells with CTX-NP resulted in nearly complete reduction in EGFR accessibility to the EGFR antibody as evidenced by reduced staining (Fig S3), further demonstrating targeting specificity. Collectively, these findings confirm that cellular binding of the CTX-NPs in CTX-resistant cell lines is mediated through EGFR.

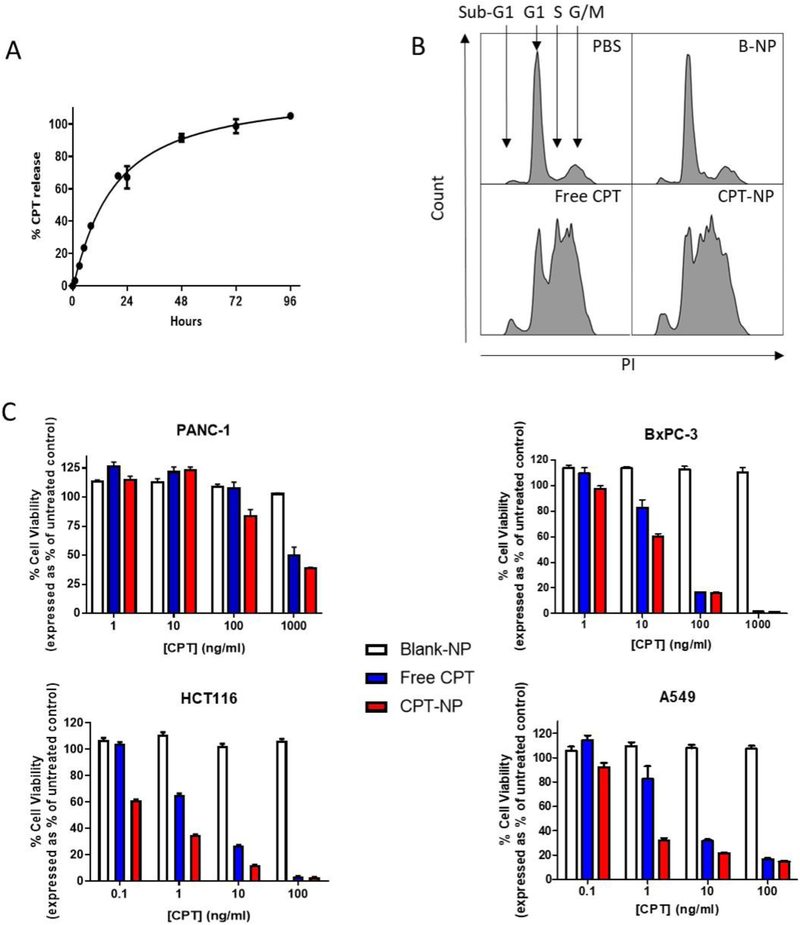

CPT activity is not compromised by nanoencapsulation.

Having demonstrated that CTX can perform as a targeting ligand to enhance NP binding to EGFR-expressing cancer cells, the effect of nanoencapsulation upon CPT release and activity was investigated to ensure that encapsulation did not compromise its cytotoxic effect. Firstly, the release of nanoencapsulated CPT was investigated over a period of 96 hours. A bi-phasic release profile was observed, with an initial burst release of 60 % of the drug within 48 hours, followed by a slower release rate of the remaining 40 % by 96 hours (Fig 4A). To assess whether drug efficacy was retained upon nanoencapsulation, CPT effects upon HCT116 cell cycle progression were investigated following treatment with free CPT or CPT-NPs. Equal concentrations of CPT were added to cells either as free drug or encapsulated within NPs. Blank-NPs were added to cells at an identical polymer concentration as a control. Both free CPT and CPT-NPs induced cell cycle arrest in S phase and decreased the number of cells in G1 phase. A concomitant increase in the sub-G1 phase was also observed, indicative of cells undergoing CPT-induced apoptosis (Fig 4B). This data confirmed that CPT activity was not compromised by nanoencapsulation. Moreover, no cell cycle alteration was seen in response to blank-NPs, thus verifying the biocompatibility of PLGA.

Figure 4. CPT activity is retained upon nanoencapsulation.

(A) Release profile of CPT from NPs into PBS/ 2 % Tween 80 using Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes at 37 °C. Mean ± s.e.m (n=2) (B) Cell cycle analysis of HCT116 cells after a 24 hour incubation with 40 ng/mL CPT, either as a free drug or encapsulated within NPs; an equivalent concentration of blank-NP was used as a control. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Data analysed using FlowJo 10 software. (C) Viability of cell lines after treatment with increasing concentrations of CPT, either as a free drug or within NPs, with an equivalent concentration of blank-NPs as a control. After 72 hours, viability was measured by Celltiter Glo assay. Mean ± s.e.m. Data representative of three independent repeats.

In further studies, PANC-1, BxPC-3, HCT116 and A549 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of free- or nanoencapsulated CPT and cell viability was assessed using the Cell Titer-Glo assay after 72 hours. All cell lines responded to CPT exposure albeit with different sensitivity profiles. PANC-1 cells were notably more resistant compared to the other cell lines. When compared to free CPT, cell viability was reduced to a greater extent by CPT-NPs (Fig 4C). These findings demonstrate enhanced uptake of CPT when formulated within CTX-targeted nanoparticles and suggest that drug activity is not only preserved, but also enhanced following nanoencapsulation.

CTX nanoconjugation increases CPT delivery to cells in vitro.

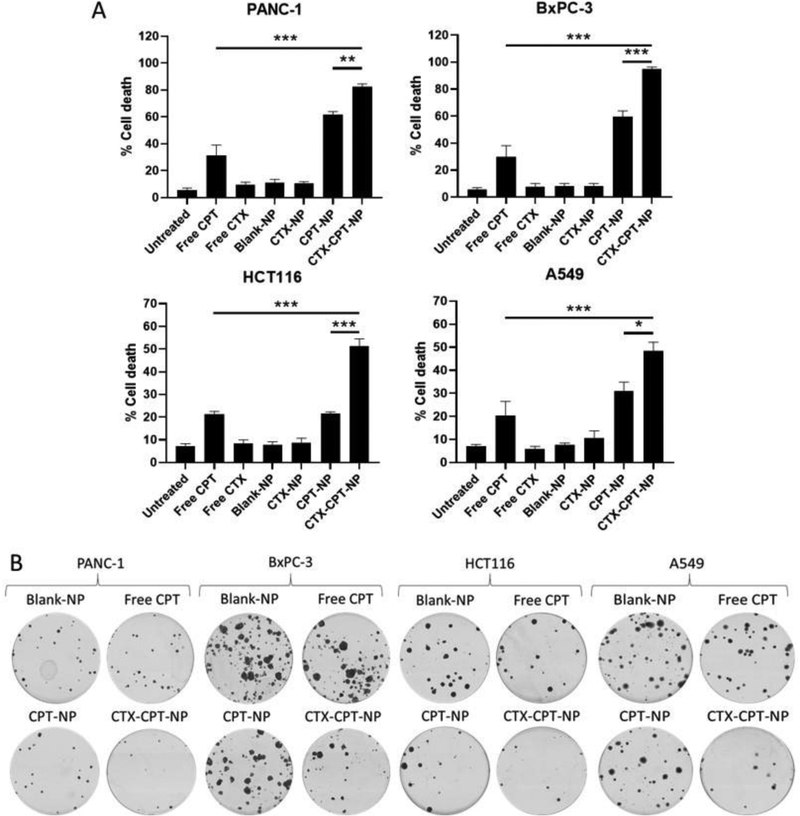

The contribution of CTX to the targeting of CPT-NPs to the CTX-resistant cells was assessed by analysis of apoptosis induction using an annexin V/PI assay. Cells were treated with 100 ng/mL CPT (or 250 ng/mL CPT for less-sensitive PANC-1 cells) either as a free drug treatment or within non-conjugated or CTX-conjugated NPs along with relevant controls. The exposure of cells to NPs and controls was limited to one hour only in order to demonstrate superior delivery of CPT within a targeted formulation. Apoptosis was most pronounced following treatment with CTX-CPT-NPs, which mediated significant increases in cell death compared to the non-targeted CPT-NPs and other controls in all cell lines examined (Fig 5A). Furthermore, clonogenic assays examining the long term effect of CTX-CPT-NPs compared to non-targeted CPT-NPs revealed similar trends, with CTX-CPT-NPs reducing colony formation to a greater extent than did non-targeted NPs (Fig 5B). To confirm that CTX nanoconjugation enhanced CPT-induced cytotoxicity, caspase-3/−7 activity levels were measured as a readout of apoptosis induction in the cell lines after 24 hours of treatment with CTX-conjugated CPT-entrapped NPs (CTX-CPT-NPs) or the relevant controls. Cells treated with CTX-CPT-NPs showed the highest caspase-3/−7 levels, suggesting that they were undergoing apoptosis to a greater extent than all other groups that contained equal concentrations of the drug (Fig S4).

Figure 5. CTX nanoconjugation increases CPT delivery to cells in vitro.

(A) Annexin V/PI staining of cells after 1 hour of treatment at 4 °C with 100 ng/mL CPT (or 250 ng/mL for PANC-1 cells) either as free drug or encapsulated in NPs, followed by a 72 hour incubation at 37 °C. Relevant controls included blank-NPs and a no-drug control. Mean ± s.e.m (n=3); statistical significance established using the one way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. (B) Representative images of colony formations 11–13 days after a 1 hour treatment 4 °C with 100 ng/mL CPT (or 250 ng/mL for PANC-1 cells) in NPs or as a free drug (along with relevant controls), followed by re-plating at 250 cells per dish and incubation at 37 °C for an additional 11–13 days. Data representative of three independent experiments.

In order to confirm that the increased cytotoxicity of the targeted nanoformulation was the result of enhanced drug delivery via EGFR targeting by CTX nanoconjugation, the impact of free CTX addition during CPT exposure of cells was investigated. Combined treatment of mutant KRAS cell lines with both free CPT and free CTX showed no greater cytotoxic effect than CPT alone, confirming a lack of additive or synergistic effects between the two agents in their free form (Fig S5). In addition, the anti-proliferative effect of CTX-NPs was assessed in CTX-resistant cell lines to determine whether a receptor clustering effect, mediated by binding of the multivalent NPs to the EGFR, reduced proliferation. HCT116 cells were exposed to CTX-NPs having the same concentration of free CTX as on CTX-CPT-NPs, and no reduction in proliferation was observed (Fig S6A). To investigate whether any concentration of CTX on NPs could induce an anti-proliferative effect on both mutant KRAS cell lines, increasing concentrations of CTX-NPs was added to PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells (Fig S6B). Similar to Fig S6A, no reduction in viability was seen. Taken together, these results suggest that the greater cytotoxic effect of CTX-CPT-NPs to these CTX-resistant cell lines is the result of binding of the CTX-CPT-NPs to EGFR, followed by preferential cellular uptake and intracellular release of CPT, rather than the result of combined cytotoxicity of CPT and CTX working together, or an anti-proliferative effect induced by receptor clustering that is mediated by CTX nanoconjugation.

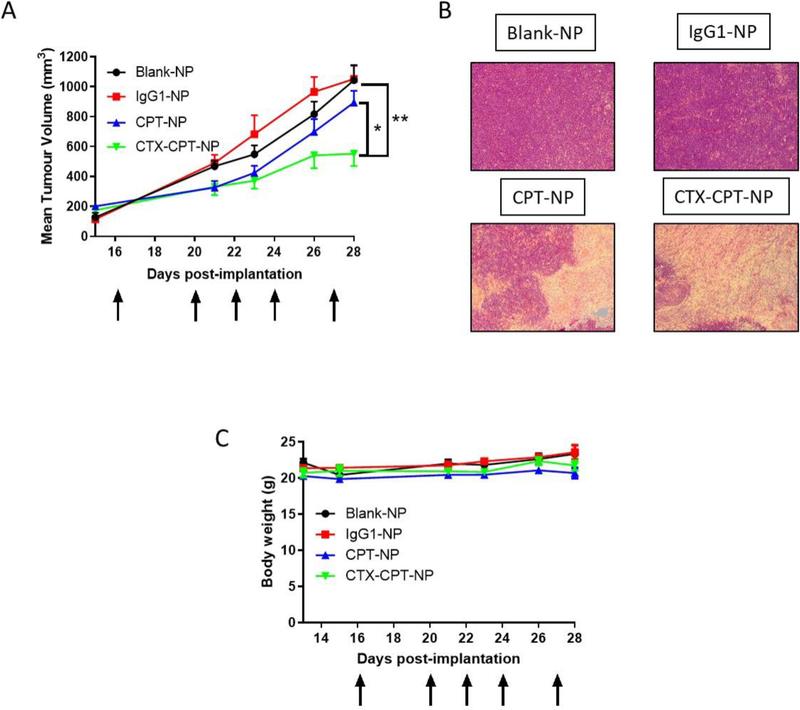

CTX nanoconjugation improves growth-inhibitory effects in PANC-1 xenograft model via increased CPT targeting to cells.

To assess whether NP surface functionalisation with CTX would lead to enhanced tumour targeting in vivo, the anti-tumour efficacy of CTX-CPT-NPs was investigated in a PANC-1 PDAC xenograft model. To achieve therapeutic drug doses for in vivo application whilst minimising the amount of polymer administered to each mouse, NP formulations having a higher CPT loading were prepared and characterised using the same optimised formulation method, with blank-NPs and isotype control antibody-conjugated NPs (IgG1-NPs) as control formulations (Table 2). The resultant CPT-NPs and CTX-CPT-NPs had similar diameters to those investigated in vitro, with negative surface charges. Surface conjugation of CTX was also comparable to that achieved with previous formulations, although the PDIs were somewhat larger. Mice received five iv doses of CTX-CPT-NPs, CPT-NPs and control formulations at a polymer concentration of 100 mg/kg which corresponded to 1.9mg/kg CPT and 3.57 mg/kg CTX per mouse. Free CTX was not administered to mice as a control due to resistance being seen previously in the same xenograft model exposed to 10 mg/kg CTX29. Additionally, free CPT was also not administered because we previously reported that iv delivery of free CPT caused damage to the microvilli in the jejunum and this was effect was reduced by nanoencapsulation20. Tumour volume measurements revealed that the cytotoxic effect of nanoformulated CPT became apparent within a short duration following treatment initiation (Fig 7A). However, after the third treatment, CTX-CPT-NPs were shown to confer a distinct therapeutic advantage over the non-targeted formulation. At day 28, significant differences were observed between treatment arms, with an approximate 50 % difference in tumour volume between CTX-CPT-NPs and blank-NPs and IgG1-NPs and an approximate 30 % difference seen between CTX-CPT-NPs and CPT-NPs (Fig 6A). H&E staining confirmed the presence of dead tumour tissue in mice receiving CTX-CPT-NPs and CPT-NPs as evidenced by an absence of staining in tumour sections compared to tumour sections taken from mice receiving either blank-NPs or IgG1-NPs which were stained purple indicative of viable tumour cells (Fig 6B). This suggested that the reductions in tumour sizes seen in mice receiving CPT-containing formulations is due to the cytotoxic effect of the drug. Moreover, body weights remained consistent throughout the course of the experiment, highlighting the protective effect of nanoencapsulation to reduce adverse effects of CPT (Fig 6C). Collectively, these results indicate that CTX-conjugated nanoparticles can effectively target a CTX-resistant cancer cell line xenograft without compromising the health of the mice.

Table 2. Characterisation of PLGA NPs for in vivo validation.

Mean ± s.e.m (n=3); measured in deionised water (dH2O).

| NP formulation | Size (nm) | PDI | Zeta potential (mV) | CPT loading (μg/mg) | CTX conjugation (μg/mg) | IgG conjugation (μg/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank-NP | 204.76 ±6.3 | 0.12 ±0.025 | −25.8 ±3.78 | NA | NA | NA |

| IgG1-NP | 240.8 ±5.93 | 0.132 ±0.04 | −26.01 ±0.07 | NA | NA | 26.1 ±2.3 |

| CPT-NP | 208.4 ±4.96 | 0.135 ±0.02 | −19.68 ±1.31 | 19.8 ±1.5 | NA | NA |

| CTX-CPT-NP | 214.91 ±4.96 | 0.157 ±0.02 | −21.18 ±0.55 | 19.4 ±1 | 35.7 ±6.0 | NA |

Figure 6. CTX nanoconjugation improves growth-inhibitory effects in PANC-1 xenograft model through increasing CPT targeting to cells.

(A) Tumour volumes in SCID mice 28 days after five iv treatment with 100 mg/kg of either Blank-NPs, IgG1-NPs, CPT-NPs or CTX-CPT-NPS. Mean ± s.e.m (n=6–9 tumours); statistical significance established using the one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. (B) H&E staining of PANC-1 tumour sections (C) Body weight. Mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

KRAS mutations are prevalent in a wide range of cancers, and underlie mechanistically the significant challenges in treatment of patients whose tumours harbour these mutations, owing to their role in promotion of tumour growth and treatment resistance. In PDAC, one of the most lethal of the top-four causes of cancer deaths, KRAS mutations affect approximately 95% of patents. Despite the high frequency of up-regulation of growth factor receptors in PDAC and other EGFR-overexpressing cancers, blockade of growth factor signalling by therapeutic antibodies has shown little efficacy in KRAS-mutated cancers12,30. Here, we have developed a polymeric chemotherapeutic drug-loaded NP formulation that incorporates the anti-EGFR antibody CTX to mediate targeting of EGFR-overexpressing cancer cells that exhibit intrinsic resistance to this antibody. We selected four different CTX-resistant cancer cell lines from three different cancer types (pancreatic, colon and lung cancer) to demonstrate that this concept of antibody repurposing is applicable to different cancers which exhibit resistance to this antibody. The therapeutic effectiveness of this system was validated in vitro and in vivo in a KRAS mutant PDAC xenograft model, demonstrating the potential to repurpose CTX, an otherwise failed therapeutic agent for KRAS-mutated cancers.

A range of cancer cell lines with recognised KRAS mutations were chosen, along with wild-type KRAS cell lines, to permit comparisons of KRAS status with CTX resistance. We observed that the KRAS G13D (HCT116), G12S (A549) and G12D (PANC-1) mutations correlated with failure of CTX to reduce cell proliferation or viability. In contrast, their wild-type KRAS counterparts were sensitive (HKH-2, HCC827) to treatment. This finding is consistent with research and clinical trials demonstrating that the activity of CTX is dependent on the mutational status of KRAS, and that CTX efficacy is confined to cancer cells expressing wild-type KRAS10–13. The only exception to this relationship was the CTX resistance observed in wild-type KRAS BxPC-3 cells. This has been reported previously and it was thought that CTX cannot prevent EGF-induced RAS pathway activation because of alterations in EGFR dimerisation patterns in this cell line31.

Stable NPs were formulated onto which CTX was conjugated using carbodiimide chemistry. The NHS groups on the polymer, which was shown to covalently attach CTX to the NPs, was a necessary component for conjugation of the antibody as PLGA 502H alone lacks activated carboxylic acid groups to facilitate conjugation. Crucially we then showed that the covalent attachment of CTX to the surface of NPs did not affect the activity of the antibody as evidenced by a reduction in cell growth in CTX-sensitive cell lines. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that upon conjugation of CTX to the surface of NPs NP binding was enhanced selectively and specifically via EGFR interaction. The data suggest that binding of the NPs is followed by EGFR-mediated endocytosis, leading to enhanced cytotoxicity of the nanoencapsulated CPT. Previous studies have shown that the conjugation of multiple antibody molecules to a single NP increases the cooperativity of binding to the target receptor, and greatly enhances their overall avidity of binding. It is probable that via such cooperative binding, a single targeted NP particle can promote receptor clustering and subsequent internalisation18,32. Previous research supports the concept that antibody nanoconjugation can enhance antibody function through receptor crosslinking. Qian et al suggested that the binding of CTX-gold nanoconjugates to EGFR-positive lung cancer cells improved the anti-proliferative effect of CTX33. Here we investigated whether CTX nanoconjugation might facilitate EGFR crosslinking and thereby enhance the anti-proliferative effect of CTX in the CTX-resistant cancer cell lines. However, as shown in Fig S6, no greater reduction in proliferation was mediated by NP-conjugated CTX, indicating that cooperative EGFR binding by CTX-conjugated NPs is sufficient to improve efficacy of NP targeting, but not by invoking an anti-proliferative function of CTX in CTX-resistant cells.

Despite severe toxicities and poor stability in an aqueous environment, CPT was selected as the model topoisomerase I drug in this study instead of FDA-approved CPT derivatives such as Irinotecan. CPT is less water soluble than irinotecan34,35, which favours a higher entrapment efficiency within polymeric NPs. Irinotecan has less potency in comparison to parental CPT and can still cause unwanted toxicities. It is also a prodrug which requires activation by conversion into an active compound called SN-3836,37. Additionally, CPT is valued as a better model drug and has been researched in advanced formulations such as the cyclodextrin-based nanoparticle-drug conjugate CRLX101 which is in Phase II clinical trials38. As previously shown, CPT is readily entrapped in NPs, reducing toxicities and damage to the jejunum and white blood cells whilst maintaining potency towards cancer cells20. In this study, CPT efficacy was improved upon nanoconjugation reducing cell viability in all CTX-resistant cell lines to a greater extent than free CPT. CTX nanoconjugation improved NP targeting and enhanced CPT-induced apoptosis in vitro. This effect was notably greater than for non-targeted CPT-NPs, and it is assumed that a higher intracellular concentration of CPT in the cytosol resulted from preferential uptake of CTX-CPT-NPs. In vivo, the advantage of targeting required some time to be seen. Initially, CPT-NPs demonstrated strong anti-tumour effects. The delay in observing the superior effect of CTX nanoconjugation may be due to the initial overwhelming cytotoxicity of both CPT-containing formulations within the tumour microenvironment masking the therapeutic benefit of EGFR targeting with CTX. However, with sequential CTX-CPT-NPs, CTX targeting of the NPs to the cells would gradually promote a greater intracellular concentration of CPT allowing the benefit of CTX conjugation of the NPs to be seen. This highlights the ability of CTX to localise CPT-NPs to the tumour microenvironment. CTX targeting of the NPs to tumour cells would promote localization of CPT-NPs to the tumour microenvironment, leading to greater internalization and intracellular concentrations of CPT, resulting in a significant reduction in tumour growth compared to non-targeted CPT-NPs. Our data are consistent with previous studies that employed CTX as a targeting agent for chemotherapeutic drugs such as gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer39, docetaxel for gastric cancer40 and celecoxib for colorectal cancer41. In those studies, CTX enhanced drug delivery, leading to enhanced cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. A previous study used CTX-conjugated CPT-loaded NPs in lung and breast cancer cells and successfully demonstrated a targeting effect in vitro only42. In this study, we have demonstrated that a CTX-conjugated nanoformulation has superior efficacy in vivo using a pancreatic cancer xenograft model that exhibits CTX resistance. Crucially, by employing models resistant to CTX as an independent therapy, our data reveal the clear potential of using the antibody simply as a targeting agent.

Conclusion

The efficacy of CTX has been dependent on the mutational status of tumour KRAS. Only those patients having tumours that express wild-type KRAS can benefit from CTX, and those having a mutant KRAS phenotype, who are in the vast majority for some cancers, such as PDAC, are relegated other treatment modalities. Our results suggest that CTX can still be administered to patients, regardless of clinical KRAS mutational status, by incorporating it as part of a nanoconjugate system targeting mutant KRAS tumours. Furthermore, this concept of antibody repurposing may be applicable to other antibodies whose clinical application is impeded by tumour resistance, providing these antibodies with an alternative function as components of drug delivery systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC grant 1598124). It was also partially funded through a US-Ireland R&D Partnership grant awarded by HSCNI (STL/5010/14, MRC grant MC_PC_15013) and by the NIH/NCI grants (R21CA168454).

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADC

antibody-drug conjugate

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CPT

camptothecin

- CTX

Cetuximab

- DAR

drug to antibody ratios

- DCM

dichloromethane

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- KRAS

Kirsten rat sarcoma

- NaOH

sodium hydroxide

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- MWM

molecular weight marker

- NPs

nanoparticles

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PDI

polydispersity index

- PI

propidium iodide

- PLGA

poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- Rho

rhodamine 6G

- SEM

scanning electron micrography

- s.e.m.

standard error mean

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- T-DM1

Trastuzumab emtansine

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: All in vivo experiments were carried out in accordance with the UK Home Office and approved by Queen’s University Belfast Ethical Review Committee.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brand TM, Iida M & Wheeler DL Molecular mechanisms of resistance to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Cancer Biol. Ther 11, 777–792 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Normanno N et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene 366, 2–16 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masui H et al. Growth Inhibition of Human Tumor Cells in Athymic Mice by Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies. Cancer Res. 44, 1002–1007 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell 7, 301–311 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Nicolantonio F et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol (2008). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lièvre A et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 3992–3995 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stintzing S et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a post-hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild-type subgroup of this randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 17, 1426–1434 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan C & Du X KRAS mutation testing in metastatic colorectal cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology (2012). doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Román M et al. KRAS oncogene in non-small cell lung cancer: Clinical perspectives on the treatment of an old target. Molecular Cancer (2018). doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0789-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waddell N et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature (2015). doi: 10.1038/nature14169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Houdt WJ et al. Oncogenic KRAS desensitizes colorectal tumor cells to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition and activation. Neoplasia 12, 443–452 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misale S et al. Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature (2012). doi: 10.1038/nature11156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichert JM Antibody-based therapeutics to watch in 2011. MAbs 3, 76–99 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krop IE et al. A phase II study of trastuzumab emtansine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer who were previously treated with trastuzumab, lapatinib, an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. J. Clin. Oncol 30, 3234–3241 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavilio D, Galluzzi L & Lugli E Novel multifunctional antibody approved for the treatment of breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2, 5–7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fay F & Scott CJ Antibody-targeted nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Immunotherapy 3, 381–394 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston MC & Scott CJ Antibody conjugated nanoparticles as a novel form of antibody drug conjugate chemotherapy. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid D et al. Efficient drug delivery and induction of apoptosis in colorectal tumors using a death receptor 5-targeted nanomedicine. Mol. Ther 22, 2083–2092 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirasawa S, Furuse M, Yokoyama N & Sasazuki T Altered growth of human colon cancer cell lines disrupted at activated Ki-ras. Science (80-.). (1993). doi: 10.1126/science.8465203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmid D et al. Nanoencapsulation of ABT-737 and camptothecin enhances their clinical potential through synergistic antitumor effects and reduction of systemic toxicity. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1454–11 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passero FC, Grapsa D, Syrigos KN & Saif MW The safety and efficacy of Onivyde (irinotecan liposome injection) for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer following gemcitabine-based therapy. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther (2016). doi: 10.1080/14737140.2016.1192471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarron PA et al. Antibody targeting of camptothecin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles to tumor cells. Bioconjug. Chem 19, 1561–1569 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gradiz R, Silva HC, Carvalho L, Botelho MF & Mota-Pinto A MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 - Pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines with neuroendocrine differentiation and somatostatin receptors. Sci. Rep (2016). doi: 10.1038/srep21648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed D et al. Epigenetic and genetic features of 24 colon cancer cell lines. Oncogenesis (2013). doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2013.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh A et al. A Gene Expression Signature Associated with ‘K-Ras Addiction’ Reveals Regulators of EMT and Tumor Cell Survival. Cancer Cell (2009). doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deer EL et al. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas (2010). doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c15963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toda K et al. Metabolic Alterations Caused by KRAS Mutations in Colorectal Cancer Contribute to Cell Adaptation to Glutamine Depletion by Upregulation of Asparagine Synthetase. Neoplasia (United States) (2016). doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakrabarti G Mutant KRAS associated malic enzyme 1 expression is a predictive marker for radiation therapy response in non-small cell lung cancer. Radiat. Oncol (2015). doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0457-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YJ, Jung K, Baek DS, Hong SS & Kim YS Co-targeting of EGF receptor and neuropilin-1 overcomes cetuximab resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with integrin β1-driven Src-Akt bypass signaling. Oncogene (2017). doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waters AM & Der CJ KRAS: The critical driver and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med (2018). doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang ZQ et al. Differential responses by pancreatic carcinoma cell lines to prolonged exposure to Erbitux (IMC-C225) anti-EGFR antibody. J. Surg. Res 111, 274–283 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Miguel D, Gallego-Lleyda A, Anel A & Martinez-Lostao L Liposome-bound TRAIL induces superior DR5 clustering and enhanced DISC recruitment in histiocytic lymphoma U937 cells. Leuk. Res (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian Y et al. Enhanced cytotoxic activity of cetuximab in EGFR-positive lung cancer by conjugating with gold nanoparticles. Sci. Rep 4, 1–8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pizzolato JF & Saltz LB The camptothecins. Lancet (2003). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13780-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pommier Y Topoisomerase I inhibitors: Camptothecins and beyond. in Nature Reviews Cancer (2006). doi: 10.1038/nrc1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slatter JG et al. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and excretion of irinotecan (CPT-11) following i.v. infusion of [14C]CPT-11 in cancer patients. Drug Metab. Dispos (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anthony L Irinotecan toxicity. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss GJ et al. First-in-human phase 1/2a trial of CRLX101, a cyclodextrin-containing polymer-camptothecin nanopharmaceutical in patients with advanced solid tumor malignancies. Invest. New Drugs (2013). doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9921-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patra CR et al. Targeted delivery of gemcitabine to pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cetuximab as a targeting agent. Cancer Res (2008). doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sreeranganathan M et al. In vivo evaluation of cetuximab-conjugated poly(γ-glutamic acid)-docetaxel nanomedicines in EGFR-overexpressing gastric cancer xenografts. Int. J. Nanomedicine 12, 7165–7182 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Limasale YDP, Tezcaner A, Özen C, Keskin D & Banerjee S Epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted immunoliposomes for delivery of celecoxib to cancer cells. Int. J. Pharm 479, 364–373 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deepagan VG et al. In vitro targeted imaging and delivery of camptothecin using cetuximab-conjugated multifunctional PLGA-ZnS nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 7, 507–519 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.