Abstract

Objective

Text messaging interventions are effective. Despite high utilization of smartphones, few studies evaluate text messaging for cessation in middle-/lower-income countries. Initiating tobacco treatment in hospitals is an effective but underutilized approach for reaching smokers. We evaluated a hybrid phone counseling/text messaging intervention for supporting cessation among hospitalized smokers in Brazil.

Methods

We used an experimental design to assess the feasibility and potential effect size of the intervention. Participants (N = 66) were recruited from a university hospital and randomized in a 2:1 ratio into TXT (one session of telephone counseling plus 2 weeks of text messaging; N = 44) or Standard Care control group (N = 22). Participants lost to follow-up were counted as smokers.

Results

Counselors sent 1186 texts, of which 924 (77.9%) were received by study participants. Participants rated the TXT content as “helpful” (80.4%) and the phone counseling length to be “just right” (95.1%). Although the study was not powered to evaluate abstinence rates, we did observe a higher prevalence of abstinence in the TXT compared to control group at both 1-month follow-up (25.0% vs. 9.1%) and 3-month follow-up (31.8% vs. 9.1%). Carbon monoxide-verified abstinence at month 3 was also higher in TXT (20.5% vs. 4.5%).

Conclusions

This hybrid telephone/text intervention should progress to full-scale effectiveness testing as it achieved favorable outcomes, was acceptable to participants, and was readily implemented. This type of intervention has strong potential for expanding the reach of hospital-initiated tobacco treatment in middle-/lower-income countries.

Implications

This study extends research on hospital-initiated smoking cessation by establishing the feasibility of a novel text-messaging approach for post-discharge follow-up. Text messaging is a low-cost alternative to proactive telephone counseling that could help overcome resource barriers in middle- and lower-income countries. This hybrid texting/counseling intervention identified smokers in hospitals, established rapport through a single telephone follow-up, and expanded acceptability and reach of later support by using text-messaging, which is free of charge in this and other low-income countries. The favorable cessation outcomes achieved by the hybrid intervention provide support for a fully powered effectiveness trial.

Introduction

Brazil is a world leader in comprehensive tobacco control and has achieved a dramatic decline in smoking rates from 34.8% in 1989 to 15% in 2014.1 Regardless, Brazil still has 21.9 million tobacco users,2 and in 2015 was listed among the top 10 countries with the largest number of total smokers.1 Brazil’s public health system provides free medication and behavioral support for cessation3 and has guidelines for hospital-based tobacco treatment. To date, however, only one Brazilian study has evaluated a hospital-initiated tobacco intervention. It compared a 30-minute in-hospital intervention plus seven telephone post-discharge calls versus a single 15-minute in-hospital session and found nonsignificant differences in self-reported quit rates (44.9% vs. 41.7%, respectively).4

Hospital-initiated cessation intervention must continue after discharge in order to be effective.5 Telephone counseling is a common strategy to provide this support.6,7 Communication methods have advanced rapidly since publication of most definitive hospital intervention trials. Recent studies have established text messaging as an effective way to deliver cessation support at a distance.8,9 Text messaging has not yet, however, been evaluated as a way to provide post-discharge support among hospitalized smokers. A multicomponent approach using text messaging in conjunction with phone counseling has good potential for increasing smoking cessation rates.10,11

A hybrid texting/counseling approach is also an attractive option for lower-income countries. It could eliminate access barriers such as cost, time, travel, and scheduling.12 Texting is cost-effective and can tailor messages to user characteristics.9 An initial call can establish rapport and thereafter text messages can provide asynchronous communication with participants and ultimately may be used with large numbers of tobacco users. This approach may be uniquely well suited to hospitals, where tobacco users may be identified, contacted for one post-discharge transition call, and handed over to a tailored text program.

To date, no text messaging interventions have been tested in middle- or low-income countries.9 Most (84%) of Brazil’s 200 million citizens have at least one mobile phone,13 and there is no charge for receiving texts. Our experimental feasibility study14 tested this hybrid phone counseling/text messaging intervention among hospitalized smokers in Brazil.

Methods

Design

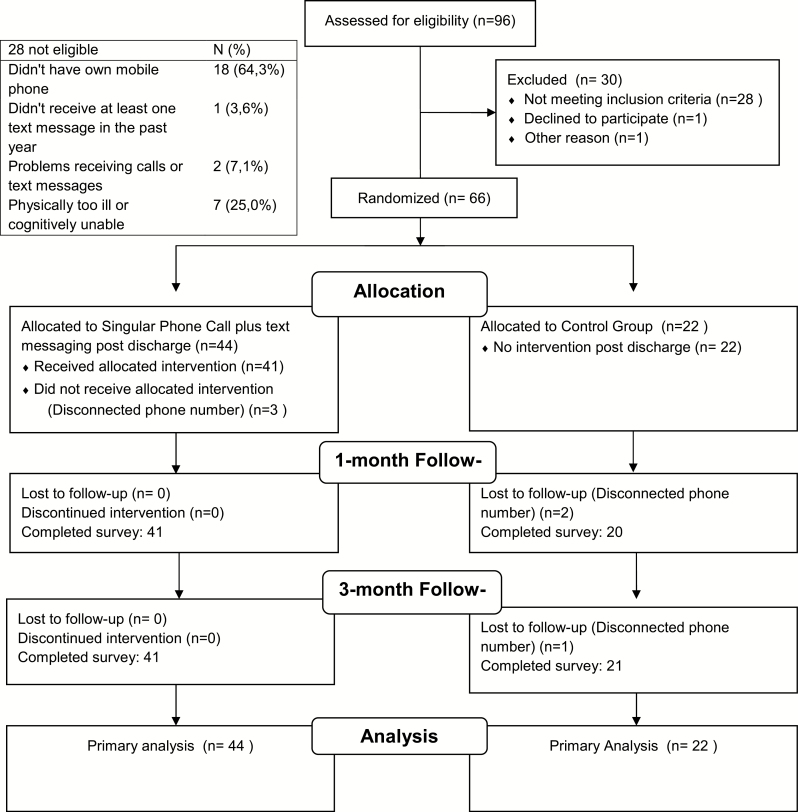

This study was a two-arm randomized trial of a post-discharge treatment program among 66 hospitalized smokers (Figure 1). Participants were recruited during their hospitalization and contacted at 1 and 3 months for follow-up. During hospitalization, all patients received standard care, including (1) screening, (2) brief counseling, and (3) access to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Post-discharge, eligible patients were randomly assigned to one of two follow-up conditions: phone counseling plus text message (TXT) versus standard care (control). The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee Review Board/process number 1.460.247 and enrolled in the Clinical Trials Registry (NCT02571244).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Setting

Patients were recruited from a 140-bed public university hospital serving 294 inpatients monthly. The hospital’s smoking prevalence is 16.2%.15 The hospital serves mainly a low-income population. The hospital has an electronic medical record system and a tobacco-free campus. The Interdisciplinary Center of Research and Intervention in Tobacco (CIPIT) provides inpatient tobacco treatment that follows the Brazilian National Institute of Cancer (INCA) guidelines.3 These interventions are delivered by graduate students enrolled in a multi-professional residence program and overseen by a hospital pulmonologist (MD).

Participants, Screening, and Randomization

The study population consisted of patients aged ≥18 years admitted to the hospital who had smoked cigarettes within the past 30 days, had their own mobile phone, had received at least one text message in the past year and were able to provide informed consent. Participants were excluded if they were admitted to an intensive care unit, in isolation, physically or cognitively unable to participate, or currently incarcerated.

Study staff screened potential participants using electronic medical record data, and then completed in-person screening and consent at the bedside. Figure 1 describes recruitment and retention of study participants. To maximize data collected on intervention feasibility, we randomized eligible participants to groups in a 2:1 intervention/control ratio.

Randomization occurred post-discharge to ensure that patients received the same care inside the hospital. Hospital counselors sent the names of potential participants and their eligibility screening results, but not baseline data, to the PI, who assigned patients to study arm using a random sequence list generated by the study biostatistician (Colugnati) using blockrand in R. The PI assigned patients in the order in which they were received to the next available spot on the randomization list.

Interventions

Standard Care

This included educational materials, brief intervention (BI) and access to NRT (adhesive patch and gum) for eligible patients. In accordance with the Brazilian National Treatment Guideline,3 patients with a Fagerstrom score ≥5 were eligible for free medication in the hospital and 1 month post-discharge. The brief intervention lasted 5–20 minutes, and followed the Five A’s.3 Counselors related the patients’ diagnosis to their smoking and discussed the importance of quitting. Patients were encouraged to remain abstinent after discharge and given a brochure, information about local cessation resources, and NRT. The study PI, who completed tobacco treatment specialist (TTS) training in the United States, gave inpatient providers a 4-hour training, supervised counselor delivery of the intervention until adherence to the protocol was met, and provided weekly refresher trainings and case discussion sessions.

Experimental Intervention

Patients randomized to TXT received a single telephone call from study staff during the first week following discharge, plus multiple text messages post-discharge. Telephone counseling lasted approximately 15 to 30 minutes. All patients were asked during the call if they were ready to quit in the next 30 days. Smokers motivated to quit in this period were invited to complete a quit plan and those who were abstinent to complete a cessation maintenance plan. Smokers unwilling to set a quit date received counseling designed to increase motivation to quit. The counseling approach addressed behavioral and cognitive issues, including motivation, confidence, quitting history, environmental factors, trigger situations, coping strategies, medication use, relapse prevention, and setting a quit date. The protocol was adapted from US quitline protocols6 and other outpatient counseling studies.7

Text Message Content Development

Text message themes were adapted from Naughton’s matrices, which tailor messages to tobacco users’ progress in quitting (Supplementary Appendix A in Portuguese and Appendix B in English).16 A questionnaire administered by counselors during the post-discharge call identified participants’ specific concerns and reasons for quitting, which guided development of participant-specific messages. Because confidence/ self-efficacy for quitting is a predictor of success,17 and in particular appears to mediate the effect of NRT,18,19 the research team used Bandura’s self-efficacy theory20 to design the content of text messages. For instance, participants’ perceived benefits from quitting or strategies used in previous quit attempts were sent to that participant as text messages to build his/her self-efficacy for quitting.

Message Scheduling and Quality Control

Each patient in TXT received up to 30 text messages for 8–15 days after discharge. The frequency and content of the messages varied depending on the participants’ motivation to quit. Patients abstinent or preparing to quit in the next 30 days received two messages/day over the course of 15 days. Patients not ready to quit received two messages/day over the course of 8 days. Messages were sent using a mobile phone that registered the time the message was delivered and whether the message was received. The text message protocol used in this study was unidirectional—participants could not respond to texts. The choice for two daily texts was based on a meta-analysis indicating that fixed-schedule messages performed better than decreasing or variable schedules.8 In this study, text messages were sent manually via a mobile phone which limited the extent of message tailoring, length and frequency.

Measures

Baseline data were collected from the electronic medical record and in-person surveys, and follow-up data were collected by phone. Measures included demographic and tobacco use characteristics (Table 1). Feasibility focused on acceptability, implementation, and limited-effectiveness testing.14 To address acceptability, we assessed satisfaction with, and perceived usefulness of, the intervention. Implementation measures included adherence to medications, number of messages sent/received, counseling length, and cell phone status. We assessed whether participants used NRT since hospitalization (Yes/No) and the type of NRT used.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic, Tobacco-Related, and Psychosocial Characteristics of Sample by Study Condition

| Characteristic | Randomized (66) | Intervention (44) | Control (22) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 47.7 (11.5) | 47.5 (12.7) | 48.2 (8.9) | .83 |

| Male, n (%) | 34 (51.5) | 24 (54.5) | 10 (45.5) | .48 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, n (%) | 44 (66.7) | 27 (61.4) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Black, n (%) | 8 (12.1) | 6 (13.6) | 2 (9.1) | .49 |

| Grayish-brown/indigenous(%) | 14 (21.2) | 11 (25.0) | 3 (13.6) | |

| Married, n (%) | 28 (42.4) | 18 (40.9) | 10 (45.5) | .95 |

| High school or less education, n (%) | 59 (89.3) | 37 (84.1) | 22 (100) | .08 |

| Current depressive symptomsa, n (%) | 19 (28.8) | 13 (29.5) | 6 (27.3) | .84 |

| Alcohol abuseb ≥ 4, n (%) | 32 (48.5) | 21 (47.7) | 11 (50.0) | .86 |

| Days smoked cigarettes in past 30 days, mean (SD) | 25.4 (7.8) | 24.6 (8.6) | 27.1(5.4) | .30 |

| Cigarettes/day, mean (SD) | 14.6 (10.7) | 15.0 (11.3) | 13.8 (9.7) | .67 |

| Nicotine dependencec, mean (SD) | 4.1 (2.3) | 3.9 (2.2) | 4.4 (2.5) | .44 |

| Use other tobacco products, n (%) | 10 (15.4) | 5 (11.6) | 5 (22.7) | .28 |

| Living with other smoker, n (%) | 24(36.4) | 15 (34.1) | 9 (40.9) | .85 |

| Age at initiation in years, mean (SD) | 16.3 (4.3) | 16.3 (4.0) | 16.2 (4.9) | .90 |

| Withdrawal score (0–4), mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.6) | 25 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.6) | .13 |

| Commitment to quittingd, n (%) | 48 (72.7) | 32 (72.7) | 16 (72.7) | 1.00 |

| Quit attempts in past 12 months, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.41) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.8(1.2) | .75 |

| Importance of quitting (0–10), mean (SD) | 9.0 (2.2) | 9.0 (2.1) | 9.0 (2.3) | .71 |

| Confidence to quit (0–10), mean (SD) | 7.0 (3.0) | 7.2 (3.0) | 6.7 (3.1) | .55 |

| Life use quit medication, n (%) | 11 (16.7) | 7 (15.9) | 4 (18.2) | 1.00 |

| Nicotine replacement therapy during hospitalization, n (%) | 20 (30.3) | 12 (27.3) | 8 (36.4) | .44 |

| Mobile phone numbers, mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Rural area residence, n (%) | 7 (10.6) | 6 (13.6) | 1 (4.5) | .40 |

| Excellent mobile phone signal most of the time, n (%) | 48 (72.7) | 34 (77.3) | 14 (63.6) | .20 |

| Sometimes I have problems with my mobile phone signal, n (%) | 17 (25.8) | 10 (22.7) | 8 (36.4) | .20 |

The p values were generated from independent-samples t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. No parametric variables were compared using Mann–Whitney test.

aPatient Health Questionnaire-2 Item (PHQ-2).26

bAlcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT C).27

cFagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.28

dContemplation Ladder item:”What is your smoking cessation plan after discharge?” (1 = “I’m planning to remain abstinent after discharge”; 2 = “I’m planning try to quit after discharge”).

Limited-effectiveness measures included abstinence and other outcomes. The main outcome measure for the study was self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 1 month post-randomization. Secondary outcomes included self-reported and biochemically verified abstinence at 3 months post-randomization. Exhaled carbon monoxide of ≤10 ppm was the cutoff for verification of abstinence.21 Among continuing smokers we assessed the number of cigarettes smoked per day.

Analyses

The data were entered into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). SPSS/version 15.0 was used for all analyses. Descriptive statistics (means and SDs for continuous variables and totals/percentages for categorical variables) were used to summarize demographic and feasibility measures by group. We used chi-square tests, Independent Samples t-tests, and the Mann–Whitney test for nonparametric continuous variables, as appropriate. We used OpenEpi22 to estimate the number needed for a definitive trial, based on the effects of the pilot study.

Missing data were minimal (29/2732 data points—1.06%). Subjects lost to follow-up were counted as smokers. Follow-up data for number of cigarettes smoked in the past 30 days were imputed by calculating the average values of other participant responses in the same variable and group (control/intervention). Missing categorical data points for cell phone status and text message reading were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Participants were recruited from February 2015 to March 2016 (Figure 1). Randomization led to similar groups for all baseline characteristics (Table 1). Participants were male (51.5%), with a mean age of 47.7% and 89.3% had a high school or lower education level.

Feasibility at 1-Month Follow-up

Counseling calls lasted 15 minutes on average. In total, 1186 messages were sent to 41 patients; of these, 924 (77.9%) were received by patients. Most (75.6%) participants described their cell phone status as “charged almost all the time” and 97.6% maintained the same phone number. Six patients (13.6%) in TXT used NRT compared to one patient (4.5%) in the control group.

Acceptability

Most TXT participants (80.4%) reported that the text message content was “helpful.” Similarly, most (80.5%) reported that the number of text messages received was “enough.” Nearly all (95.1%) found calls to be “just the right length.”

Limited-Effectiveness Outcomes

Eleven patients (25%) self-reported abstinence in TXT at 1 month post-randomization and two (9.1%) in the control group (p = .13). At 3 months post-randomization 14 patients (31.8%) quit in TXT and two (9.1%) reported abstinence in the control group (p = .04). Of those 16 patients that self-reported abstinence at the 3-month assessment, 10 had CO-verified smoking abstinence. The biochemically-verified quit rates for TXT was 20.5% and for the control group was 4.5% (p = .09). Among continuing smokers, the number of cigarettes smoked per day at 1-month follow-up was lower in TXT compared to the control group (mean/SD: 10.6 [6.6] vs. 12.6 [4.4], p = .25) and also at 3-month follow-up (mean/SD: 12.9 [5.2] vs. 14.6 [5.5], p = .29). With an effect size of 25% versus 9.1%, a definitive study would require a sample size of 198 to detect differences with 80% power.

Discussion

This study suggests that, in Brazil, a hybrid phone counseling/text messaging approach is a feasible and acceptable intervention for post-discharge cessation support. Most participants had adequate mobile phone coverage to participate, and nearly 80% of intervention group patients successfully received text messages. The intervention frequency and length were highly acceptable and follow-up data collection yielded overall retention rates exceeding 90%. Although not significant, more participants were abstinent at follow-up in the TXT group, compared to the control group. The quit rate achieved by our intervention group was comparable to quit rates of studies employing more intensive follow-up,5 even though most prior studies included only patients motivated to quit.

The study has some limitations. Texts were sent manually using a mobile phone by study staff, which limited the extent of message tailoring, length, and frequency. Participants not ready to quit received fewer text messages than other intervention participants. Follow-up was limited to 3 months, and the study lacked power to definitively test the interventions.

A fully-powered trial to explore the effects of a hybrid phone counseling/text messaging intervention on cessation is warranted. In advanced economy countries, pragmatic studies could evaluate this approach in collaboration with existing telephone quitlines, as some quitlines provide parallel counseling and text messaging services.10 Our participants were very satisfied with the duration and intensity of the text messaging intervention as it was designed, but we know from Public Health Service Guidelines23 and hospital trial meta-analyses5 that more support would possibly be even more effective. Future studies could prompt participants to either opt in or opt out of more texts after 15 days, or include study arms that compare longer-duration versus shorter-duration text message conditions.

In Brazil and other lower-/middle-income countries, proactive, multi-call telephone counseling24 is often not freely available.25 The pilot procedures should readily scale up to a full trial as they were designed to fit within clinical practice, and Federal University hospitals are all managed under the same authority. Our method of manually tailoring and sending messages seemed effective. Automating this process is feasible because many smokers share similar concerns (such as developing cancer) that could be included in a comprehensive message library.

Funding

The authors thank the students from CREPEIA and CIPIT for their participation in the data collection and assistance in delivering the trial. This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01 HL105232-01) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) of Brazil and the Research Support Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the government of Brazil. The study sponsor had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. None of the authors have institutional or corporate affiliations that conflict with this study, and no financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Collaborators GT. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde, 2013.Percepção do estado de saúde, estilo de vida e doenças crônicas. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: IBGE; 2014;205 ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/PNS/2013/pns2013.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer - INCA. Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância (CONPREV). Abordagem e Tratamento do Fumante - Consenso 2001. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: INCA; 2001:38 http://portal.saude.sp.gov.br/resources/ses/perfil/profissional-da-saude/homepage//tratamento_fumo_consenso.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azevedo RCS, Mauro MLF, Lima DD, Gaspar KC, da Silva VF, Botega NJ. General hospital admission as an opportunity for smoking-cessation strategies: a clinical trial in Brazil. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(6):599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rigotti NA, Clair C, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD001837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richter PK, Shireman IT, Ellerbeck FE, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sherman SE, Link AR, Rogers ES, et al. Smoking-Cessation interventions for urban hospital patients: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):566–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spohr SA, Nandy R, Gandhiraj D, Vemulapalli A, Anne S, Walters ST. Efficacy of SMS text message interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Rodgers A, Gu Y. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD006611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boal AL, Abroms LC, Simmens S, Graham AL, Carpenter KM. Combined quitline counseling and text messaging for smoking cessation: a quasi-experimental evaluation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernstein SL, Rosner J, Toll B. A Multicomponent intervention including texting to promote tobacco abstinence in emergency department smokers: a pilot study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(7):803–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gollust SE, Schroeder SA, Warner KE. Helping smokers quit: understanding the barriers to utilization of smoking cessation services. Milbank Q. 2008;86(4):601–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barbosa AF. Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Brazil. ICT Households and Enterprises 2015. São Paulo, Brazil: Brazilian Internet Steering Committee; 2016:424 http://cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/TIC_Dom_2015_LIVRO_ELETRONICO.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cruvinel E. Mensagens de texto e aconselhamento por telefone como suporte à cessação tabágica entre fumantes em alta hospitalar: um estudo clínico de viabilidade [PhD thesis]. Juiz de Fora, Brazil: Federal Univesity of Juiz de Fora; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Naughton F, Jamison J, Boase S, et al. Randomized controlled trial to assess the short-term effectiveness of tailored web- and text-based facilitation of smoking cessation in primary care (iQuit in practice). Addiction. 2014;109(7):1184–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Abroms LC. How do text-messaging smoking cessation interventions confer benefit? A multiple mediation analysis of Text2Quit. Addiction. 2017;112(4):673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Livingston AE, Callas PW, Peters EN. A randomized, controlled trial of NRT-aided gradual vs. abrupt cessation in smokers actively trying to quit. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111(1–2):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stanton CA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Papandonatos GD, de Dios MA, Niaura R. Mediators of the relationship between nicotine replacement therapy and smoking abstinence among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3 Suppl):65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Versão www.OpenEpi.com. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 23. The Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update: A U.S. Public Health Service Report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD002850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perez C, Pinheiro C, Bialous S, Cunha V, Cavalcante T. Tobacco quitline in Brazil: an additional information source to the population. Braz J Cancerol. 2011;57(3):337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gaya CDM. Estudo de validação de instrumentos de rastreamento para transtornos depressivos, abuso e dependência de álcool e tabaco. [Master Degree Dissertation]. São Paulo, Brazil: Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo/USP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12(2):159–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.