Abstract

Optical imaging plays an indispensable role in biology and medicine attributing to its noninvasiveness, high spatiotemporal resolution, and high sensitivity. However, as a conventional optical imaging modality, fluorescence imaging confronts issues of shallow imaging depth due to the need for real-time light excitation which produces tissue autofluorescence. By contrast, self-luminescence imaging eliminates the concurrent light excitation, permitting deeper imaging depth and higher signal-to-background ratio (SBR), which has attracted growing attention. Herein, this review summarizes the progress on the development of near-infrared (NIR) emitting self-luminescence agents in deep-tissue optical imaging with highlighting the design principles including molecular- and nano-engineering approaches. Finally, it discusses current challenges and guidelines to develop more effective self-illuminating agents for biomedical diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: self-luminescence, bioluminescence, chemiluminescence, afterglow, deep-tissue imaging, optical imaging

Introduction

Imaging techniques such as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission computed tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), optical imaging, ultrasound imaging, and photoacoustic (PA) imaging have become powerful tools to detect and monitor the physiological or pathological processes at the molecular, subcellular, cellular, tissue and body levels (Jokerst and Gambhir, 2011; Farzin et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2018; Ni et al., 2018a; Yin et al., 2019). Among the above-mentioned imaging modalities, optical imaging shows tremendous potential in biomedical applications due to its noninvasiveness, high sensitivity, high temporal and spatial resolution (Liu et al., 2007; Weissleder and Pittet, 2008; Choi et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2018). Moreover, optical imaging equipment are relatively low-cost and convenient to operate (Baker, 2010; Badr and Tannous, 2011; Gnaim et al., 2019). However, as a conventional optical imaging, fluorescence imaging has not been extensively utilized in clinical practice. The main reason is the need for concurrent light excitation in imaging process, which produces severe light-tissue interactions (i.e., light scattering, tissue absorption, and autofluorescence), consequently resulting in poor signal-to-background ratio (SBR) and low penetration depth (Shimon et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2017; Miao and Pu, 2018).

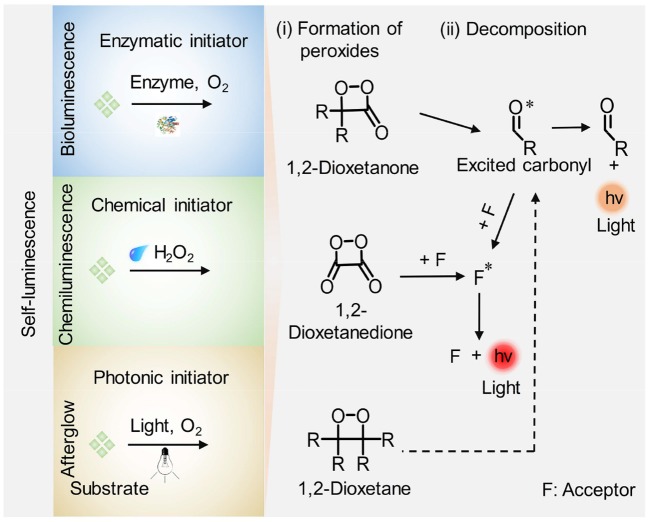

Self-luminescence imaging, which does not rely on real-time light excitation and thus eliminates the tissue autofluorescence and photo-bleaching, has attracted increasing attention in recent years. By virtue of the merits, self-luminescence imaging displays higher imaging sensitivity, higher SBR, and deeper imaging depth relative to fluorescence imaging (Table 1; Chen et al., 2017; Hananya and Shabat, 2017; Yan et al., 2019). To date, three kinds of self-luminescence imaging approaches including bioluminescence, chemiluminescence and afterglow luminescence have been developed and widely applied in biology and medicine. Among the self-luminescence imaging techniques, bioluminescence and chemiluminescence imaging do not need external light source and detect photons from enzymatic- and reactive species-initiated oxidation reaction with their substrates, respectively. By contrast, instead of the combination of enzyme/reactive species with corresponding substrate to generate photons, afterglow luminescence imaging necessitates a pre-irradiation of light to store the energy in agents and then collects the slowly releasing photons from the stored energy after the cessation of light irradiation. The underlying process to generate self-luminescence is summarized in a general way Scheme 1. Bioluminescence, chemiluminescence, and afterglow luminescence rely on respective initiator (enzymes for bioluminescence, H2O2 for chemiluminescence, and light irradiation for afterglow luminescence) to generate high-energy peroxides such as 1,2-dioxetanone, 1,2-dioxetanedione, and 1,2-dioxetane firstly. Then the peroxides dissociate directly or modulating by an acceptor molecule (F) through energy transfer, leading to the production of an excited state (an excited carbonyl or acceptor molecule) and subsequent light emission.

Table 1.

Comparison of the penetration depth and SBR for self-luminescence imaging modalities.

| Imaging modality | Penetration depth (cm) | SBR | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence | 2 | 100 | Xiong et al., 2012 |

| Chemiluminescence | 2.5 | N.A. | Shuhendler et al., 2014 |

| Afterglow | 5 | 2,922 | Jiang et al., 2019 |

N.A., Not applicable.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the general mechanism for generation of self-luminescence including bioluminescence, chemiluminescence, and afterglow luminescence. (i) Formation of high-energy peroxides: enzymes, reactive species (i.e., H2O2), and light irradiation facilitate the formation of high-energy intermediates (cyclic four-membered peroxides such as 1,2-dioxetanone, 1,2-dioxetanedione, and 1,2-dioxetane) in bioluminescence, chemiluminescence, and afterglow luminescence imaging process, respectively. (ii) A chemiexcitation process: the peroxides decompose directly or activated by an acceptor (F) through energy transfer, leading to the formation of an excited state (excited carbonyl or F*) accompanied by light emission.

Near-infrared (NIR) self-luminescence imaging has attracted increasing enthusiasm due to higher tissue penetration depth of NIR light than visible light, which dramatically expands the visualization scope of physiological or pathological processes in living subjects in a noninvasive way (Hasegawa et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016; Zhen et al., 2017). The publications and citations regarding NIR self-illuminating agents are increasing in number, and there are few reviews summarizing the recent development and advances of NIR self-illuminating agents for biomedical applications (Hananya and Shabat, 2017; Weihs and Dacres, 2019). This review will focus on the recent progress on NIR emitting self-luminescence agents for deep-tissue optical imaging, and pinpoint their contemporary molecular- and nano-engineering approaches that have been exploited in this field. As follows, the molecular construction and applications of NIR bioluminescence imaging are first described. Then, NIR chemiluminescence imaging and afterglow luminescence imaging are discussed, respectively, highlighting the strategies for red-shifting and amplifying the luminescence. Finally, it discusses current challenges and guidelines to develop more effective self-illuminating agents for biomedical diagnosis and treatment.

NIR Bioluminescence Imaging

Bioluminescence is the occurrence of light emission generated through oxidation reaction of a substrate catalyzed by an enzyme. The typical enzyme that is used for bioluminescence imaging is luciferase including firefly luciferase (Fluc), Gaussia luciferase (Gluc), Renilla luciferase (Rluc), and Nanoluc (Nluc) (Kaskova et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the naturally occurring bioluminescence is commonly resided in the visible region (Hai et al., 2017; Yao et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). For example, the native substrate for Fluc is D-luciferin with an emission peak at 560–610 nm, the native substrate for Gluc and Rluc is coelenterazine with an emission maximum at 480 nm, and the native substrate for Nluc is furimazine with an emission peak at 460 nm (Hall et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2019b). As a result, the bioluminescence in the visible region suffers from severe tissue attenuation, compromising imaging SBR and imaging depth, which is not appropriate for in vivo deep-tissue imaging. To resolve this, some approaches were adopted to red-shift the light from visible into the NIR region (650–950 nm) to achieve higher imaging depth due to the decreased light scattering and tissue absorption of NIR photons through living tissues relative to that of visible light (Mezzanotte et al., 2017).

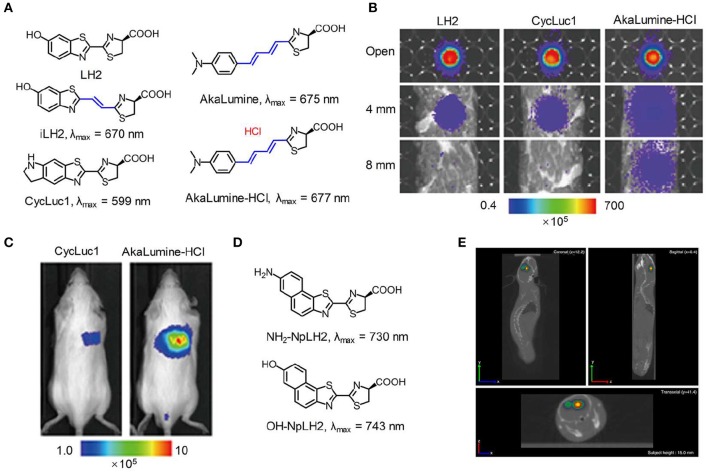

A general strategy for constructing NIR emitting bioluminescence is to elongate the π-conjugation of luciferase substrate (Miura et al., 2013). To explore the substrate with an emission wavelength in the NIR region, Pule et al. synthesized a luciferin analog (iLH2) by inserting a carbon-carbon double bond between the thiazole group and benzothiazole group of luciferin (LH2). The substrate iLH2 produced light in the NIR range (λmax = 670 nm) in presence of a native Fluc (Figure 1A) and showed an enhanced penetration depth through blood relative to luciferin (Jathoul et al., 2014). The in vivo imaging ability of iLH2 was investigated by establishing different tumor models in mice. The results revealed that the iLH2 had less tissue attenuation and showed more imaging definition for systemic lymphoma and metastatic tumor in mice compared to LH2. Using a similar strategy, Iwano et al. synthesized another luciferin analog, Akalumine, and utilized it for tumor imaging (λmax = 675 nm) (Iwano et al., 2013). However, Akalumine had poor water solubility, hampering its efficient accumulation to the targeted site. To resolve this, the same group reported a substituent, AkaLumine hydrochloride (AkaLumine-HCl), which had better water-solubility and emitted NIR light (λmax = 677 nm) in the presence of luciferase (Kuchimaru et al., 2016). After penetrating 4- or 8-mm-thick tissue, the bioluminescense intensity of AkaLumine-HCl was 5- and 8.3-fold higher than that of D-luciferin, and 3.7- and 6.7-fold higher than that of CycLuc1, respectively (Figure 1B). As expected, Akalumine-HCl performed imaging of lung metastases with higher sensitivity relative to CycLuc1 (Figure 1C). To further red-shift the bioluminescence, Mezzanotte developed two kinds of naphthyl-based luciferin analogs (i.e., NH2-NpLH2 and OH-NpLH2) that were matched with a mutant luciferase (CBR2), generating NIR bioluminescence (730 nm for NH2-NpLH2 and 743 nm for OH-NpLH2) (Hall et al., 2018; Figure 1D). In addition, the mutant enzyme/substrate (CBR2opt/NH2-NpLH2) system enabled stable and highly resolved NIR bioluminescence imaging of the migration of cells in the brain (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

NIR bioluminescence imaging. (A) Chemical structures of LH2, iLH2, CycLuc1, AkaLumine, and AkaLumine-HCl. (B) Bioluminescence imaging of LH2, CycLuc1, or AkaLumine-HCl through biological tissues with different thickness (0, 4, and 8 mm). The penetration efficiency was calculated according to the relative bioluminescence imaging intensities. (C) Representative bioluminescence imaging of lung metastasis in living mice after intraperitoneal injection of substrates (5 mM, 100 μL) (reproduced with permission from Kuchimaru et al., 2016). (D) Chemical structures of NH2-NpLH2 and OH-NpLH2. (E) Co-registered CT and bioluminescence tomography imaging of mice brain using the bioluminescence agent CBR2opt/NH2-NpLH2. Migration of cells could be clearly observed at day 5 after cell transplantation (reproduced with permission from Hall et al., 2018).

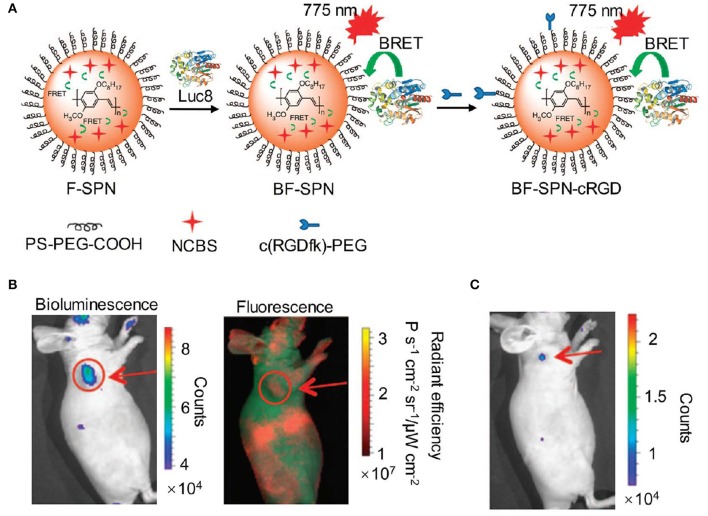

To avoid the time-consuming synthetic work, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) is an alternative approach to red-shift the light emission from visible into the NIR region. To achieve this, a NIR-emitting dye or nanoparticle was commonly selected to covalently conjugate with the natural bioluminescence system as an acceptor to allow for efficient energy transfer (Weihs and Dacres, 2019). Rao et al. developed a series of BRET-based NIR bioluminescence inorganic systems, in which a Renilla reniformis luciferase (Luc8) served as an energy donor and quantum dots (QDs) acted as an energy acceptor (So et al., 2006a,b; Yao et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2010). Such QDs-based BRET systems engineering with emissions ranging from visible to the NIR were utilized for in vivo imaging and enzyme activity detection with high sensitivity. Except for inorganic BRET systems, Rao et al. also tried to introduce organic systems for constructing BRET-based NIR bioluminescence. For instance, self-luminescent semiconducting polymer nanoparticles (BF-SPN) were developed for in vivo NIR bioluminescence imaging by combining BRET and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (Xiong et al., 2012). The nanoparticles (BF-SPNs) were designed to comprise three components: Luc8, poly [2-methoxy-5-((2-ethylhexyl)oxy)-p-phenylenevinylene] (MEHPPV) and silicon 2,3-naphthalocyanine bis(trihexylsilyloxide) (NCBS) serving as the BRET donor, the BRET acceptor (and the FRET donor) and the FRET acceptor, respectively. Such BRET-FRET system produced multiple energy transfer from Luc8 to MEHPPV and then to NCBS, resulting in final NIR bioluminescence centered at 780 nm. In order to improve the targeted ability toward tumor, the cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic (cRGD) peptides were attached to the surface of SPN to obtain BF-SPN-cRGD (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, the tumor could be clearly delineated by BF-SPN-cRGD with bioluminescence imaging while it could not be achieved with NIR fluorescence imaging, attributing to negligible background of bioluminescence in living tissue. In addition, the bioluminescence imaging of BF-SPN-cRGD could detect smaller tumors (2–3 mm in diameter) with SBR over 100, which was 30-fold higher than that of fluorescence imaging (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

NIR bioluminescence imaging. (A) Illustration of the fabrication of NIR self-luminescence nanoparticle BF-SPN-cRGD by a BRET-FRET strategy. (B) Bioluminescence (left) and fluorescence (right) imaging of U87MG tumor in living mice at t = 5 min post-injection of BF-SPN-cRGD. (C) Bioluminescence imaging of U87MG tumor (2 mm) at t = 2 h post-injection of BF-SPN-cRGD (reproduced with permission from Xiong et al., 2012).

NIR Chemiluminescence Imaging

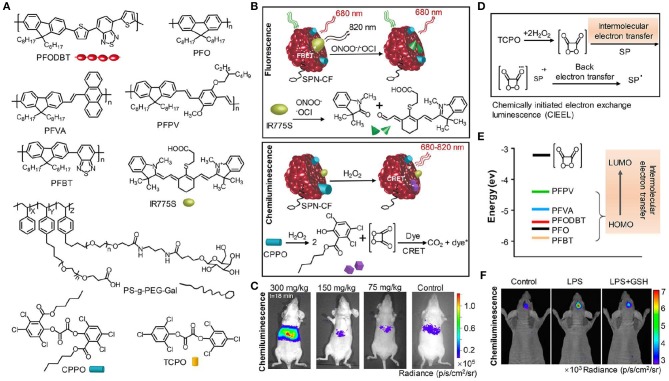

Compared with bioluminescence imaging, chemiluminescence imaging does not need an enzyme and detects light emission from the reaction of a substrate with reactive oxygen species (ROS), which performs a great deal of versatility and flexibility in experimental systems (Augusto et al., 2013; Ryan and Lippert, 2018; Vacher et al., 2018). The reaction commonly contains two sequential processes: oxidation of a substrate by ROS leads to the formation of a high energy intermediate and subsequently the high energy intermediate decomposes along with the generation of light. Chemiluminescence assays have been widely used in various biological and chemical applications due to their excellent sensitivity and high SBR (Suzuki and Nagai, 2017; Sun et al., 2018; Tiwari and Dhoble, 2018; Son et al., 2019). These advantages accelerate the development of novel chemiluminescent probes. To obtain NIR chemiluminescence which is more suitable for in vivo imaging (Green et al., 2017a; Lippert, 2017), strategies including chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer (CRET) and chemical modifications of the chemiluminescent substrate have been utilized to achieve bright and NIR chemiluminescence probes, enabling deep-tissue imaging (Lim et al., 2010; Hananya and Shabat, 2019; Nishihara et al., 2019). Oxalate esters and luminol are the typical H2O2-activated chemiluminescent compounds, which have been applied to visualize H2O2-related biological situations. To improve deep-tissue imaging ability of oxalate esters and luminol, the CRET is a facile way to shift their visible chemiluminescence into the NIR region. For instance, Rao et al. exploited an organic semiconducting polymer nanoparticle-based NIR chemiluminescence probe (SPN-CF) by integrating CRET and FRET for detecting peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Shuhendler et al., 2014). In SPN-CF, bis-(2,4,5-trichloro-6-(pentyloxycarbonyl)phenyl) oxalate (CPPO) served as the chemiluminescent substrate for reaction with H2O2 and poly(2,7-(9,9′-dioctylfluorene)-alt-4,7-bis(thiophen-2-yl)benzo-2,1,3-thiadiazole) (PFODBT, 680 nm) acted as both the CRET acceptor and the FRET donor. A cyanine dye (IR775S, 820 nm) was embedded into the nanoparticles to serve as the FRET acceptor, inducing the NIR chemiluminescence. SPN-CF was anchored with galactose-attached copolymer (PS-g-PEG-Gal) favoring hepatocytes-targeting (Hu et al., 2013; Figure 3A). In vitro experiment confirmed that the SPN-CF could detect H2O2 and ONOO− with a limit of detection (LOD) of 5 and 10 nM, respectively (Figure 3B). The SPN-CF was further explored to detect hepatotoxicity induced by the anti-pyretic acetaminophen (APAP) (McGill and Jaeschke, 2013). Dose-dependent ROS/reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in the liver could be detected by the SPN-CF within minutes of APAP challenge (Figure 3C), antedating histological changes in drug-damaged tissue. This study proved that the SPN-CF could be developed for early detection of hepatotoxicity in vivo.

Figure 3.

NIR chemiluminescence imaging. (A) Chemical structures of PFODBT, PFO, PFVA, PFPV, PFBT, IR775S, PS-g-PEG-Gal, CPPO, and TCPO. (B) Illustration of the detection mechanism for H2O2 and ONOO− or −OCl using NIR chemiluminescence probe SPN-CF. (C) Representative chemiluminescence images of mice after treatment with different APAP dosages, from left to right (300, 150, 75 mg/kg, or saline), followed by injection of 0.8 mg SPN-CF (reproduced with permission from Shuhendler et al., 2014). (D) Schematic for the mechanism of CIEEL from TCPO to SPNs. (E) The HOMO levels of SPs and the LUMO level of 1,2-dioxetanedione. (F) Representative chemiluminescence imaging of mice brain after treatment with saline, LPS (10 mg/mL, 2 μL) or LPS with GSH (500 mg/mL, 1 μL), followed by an intracerebral injection of SPN-PFPV (10 mg/mL, 2 μL) at t = 4 h later (reproduced with permission from Zhen et al., 2016).

To further enhance the chemiluminescence efficacy, Pu group reported the screening of five polyfluorene derivatives-based luminescent reporters (PFO, PFVA, PFPV, PFPT, and PFODBT) to pair with the substrate bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) oxalate (TCPO) (Zhen et al., 2016), as shown in Figure 3A. Among all the SPNs, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of PFPV was closest to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of 1,2-dioxetanedione (Figure 3E), which led to the fastest intermolecular electron transfer between them and thereby created the highest chemiluminescence intensity based on the chemically initiated electron exchange luminescence (CIEEL) mechanism (Figure 3D). The optimized system (SPN-PFPV) showed a quantum yield (QY) of 2.3 × 10−2 einsteins/mol, superior to the previously reported probes (Lim et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Augusto et al., 2013). Furthermore, the PFPV-SPN had a high sensitivity to detect H2O2 with LOD as low as 5 nM. To endow this probe with NIR chemiluminescence for in vivo imaging, a NIR dye (NCBS) as an energy acceptor was doped into SPN-PFPV to obtain SPN-PFPV-NIR with 778 nm emission by CRET. The SPN-PFPV-NIR allowed the ultrasensitive detection of H2O2 in vivo in both peritonitis and neuroinflammation models (Figure 3F).

Recently, the NIR self-illuminating nanomaterials based on luminol system were developed for inflammation imaging (Liu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019). Zhang synthesized a biodegradable polymer nanoparticle conjugating chlorin e6 (Ce6) and luminol (CLP) (Xu et al., 2019). In the presence of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and ROS, luminol emitted luminescence at 440 nm, which was shifted to the Ce6 emission (675 nm) via energy transfer. The ROS-induced oxidation of luminol and efficient energy transfer endowed the self-illuminating CLP nanoparticle with an outstanding in vivo imaging capability to detect inflammation in various animal models.

Different from above-mentioned chemiluminescent compounds which require both sequential oxidation and decomposition steps in imaging process, dioxetane-based chemiluminescent agent is an oxidized high-energy species, which eliminates the ROS-oxidation step and directly generates light emission after substrate decomposition. The dioxetane can remain stable at room temperature until phenol-protecting group was removed to initiate the decomposing process, which is an ideal scaffold for designing stimulus-responsive chemiluminescent probes. To date, dioxetane-based chemiluminescent probes have been well developed for detecting enzymes and other analytes (Cao et al., 2016; Ryan and Lippert, 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Hananya and Shabat, 2019). To construct NIR dioxetane agents, Shabat et al. recently reported a “turn-on” NIR fluorophore-tethered dioxetane chemiluminescence probe for β-galactosidase imaging (Hananya et al., 2016). In the presence β-galactosidase, the protecting group of dioxetane as the CRET donor was removed to form the electronically excited benzoate and then the energy was transferred to NIR fluorophore (QCy) acting as the CRET acceptor, which resulted in efficient and bright NIR chemiluminescence (714 nm). The chemiluminescence intensity of the probe was enhanced by 100-fold compared to the probe without tethering NIR fluorophore. Moreover, after incubation with β-galactosidase, the NIR fluorophore-tethered dioxetane probe was then injected into living mice and obtained clear chemiluminescence imaging with 6-fold increase in signal intensity than that obtained by green fluorophore-tethered dioxetane probe.

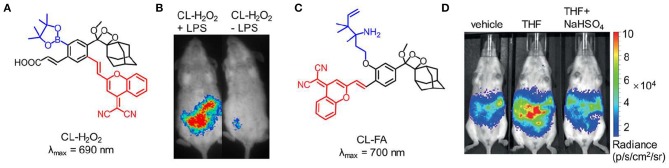

Although the NIR chemiluminescent probes based on dioxetane can be easily obtained by CRET, the chemiluminescence intensity is limited by the energy-transfer efficiency. An alternative strategy is to develop NIR chemiluminescence probe with a direct emission mode through structural modification. Recently, Shabat et al. put forward a design strategy to generate NIR chemiluminescence by extending π-conjugation length of the chemical substrate. Based on the design, a NIR-emitting phenoxy-dioxetane luminophore (690 nm) with dicyanomethylene-4H-chromene (DCMC) as an electron acceptor was synthesized (Green et al., 2017b). To achieve the ability to detect H2O2, the phenol group of this luminophore was masked with aryl-boronate that can react with H2O2 to generate the active phenolate-dioxetane (Figure 4A). This probe was investigated to monitor H2O2 in living mice and the inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Figure 4B shows that the inflammation for LPS-treated mice was clearly visualized with stronger chemiluminescence signal compared with that of non-LPS-treated mice. In 2018, another NIR-emitting phenoxy-dioxetane luminophore with a 2-aza-Cope FA-reactive trigger was reported for monitoring formaldehyde (FA) (Figure 4C; Bruemmer et al., 2018). With NIR chemiluminescence at 700 nm, the luminophore was evaluated for in vivo FA imaging in mice, which confirmed that this probe could detect clearly endogenous FA released from the folate metabolism (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

NIR chemiluminescence imaging. (A) Chemical structure of probe CL-H2O2. (B) Representative chemiluminescence images of living mice treated with LPS (0.1 mg/mL, 1 mL) (left) or PBS buffer (1 mL, pH 7.4) (right), followed by t = 4 h post-injection of probe CL-H2O2 (reproduced with permission from Green et al., 2017b). (C) Chemical structure of probe CL-FA. (D) Representative chemiluminescence imaging of endogenous FA produced through tetrahydrofolate (THF) metabolism (reproduced with permission from Bruemmer et al., 2018).

NIR Afterglow Imaging

Bioluminescence and chemiluminescence require respective enzyme or ROS to oxidize their substrate to generate luminescence, and thus the imaging signal was easily disturbed by cellular environment and substrate availability. Different from bioluminescence and chemiluminescence imaging, afterglow imaging detects slow release of photons from the chemical or energy defects stored by light pre-irradiation (Xu et al., 2016; Zhen et al., 2018; Lyu et al., 2019). The separation of light irradiation and signal collection circumvent the autofluorescence, inducing remarkable improvement of imaging sensitivity and SBR. Afterglow luminescence possesses extremely long lifetime, up to minutes to hours, which is long enough to implement time-resolved bioimaging without additional instrument. To achieve deep-tissue imaging, some afterglow nanoagents including inorganic and organic nanoparticles with NIR luminescence have been reported (Maldiney et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013).

Inorganic persistent luminescence nanoparticles containing rare-earth metal ions have been explored as afterglow nanoagents for a long time. In the past 10 years, some advances have been made to prepare NIR emitting inorganic afterglow nanoparticles as highly sensitive tools for real-time bioimaging in living animals (Abdukayum et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Maldiney et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2015; Lécuyer et al., 2016; Ai et al., 2018). For instance, Han et al. employed an aqueous-phase reaction procedure to synthesize a water-soluble inorganic nanoparticle ZnGa2O4Cr0.004 with sub-10 nm in size and high NIR persistent luminescence intensity (Li et al., 2015). In vivo imaging result confirmed that afterglow nanoparticles had outstanding imaging ability with a SBR of 275. In addition, under the simulated deep-tissue environment created by covering a 1-cm-thick pork slab on living mouse, the renewable afterglow luminescence signal of the nanoparticle could be clearly observed. Imaging in NIR-II window (1,000–1,700 nm) possesses less light-tissue interactions (i.e., reduced light scattering) than those in NIR-I window, permitting imaging with higher SBR and sensitivity (Hong et al., 2014; Antaris et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2019a; Tian et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Thus, to explore NIR-II afterglow agents, Zhang et al. synthesized a novel multifunctional nanoparticle mSiO2@Gd3Ga5O12:Cr3+,Nd3+ (mSiO2@GGO) (Shi et al., 2018). These mSiO2@GGO nanoparticles showed excellent afterglow luminescence in the first NIR window (745 nm) and second NIR window (1,067 nm). The NIR-I luminescence of the mSiO2@GGO could penetrate through the 2 cm-thickness tissue with a SBR of 5.5. To evaluate the NIR–II imaging ability of the mSiO2@GGO, the nanoparticles were subcutaneously injected into the abdomens of mice and a bright NIR–II luminescent signal was observed at the injection site. The result indicated that the mSiO2@GGO could be employed for deep-tissue imaging in NIR–II region.

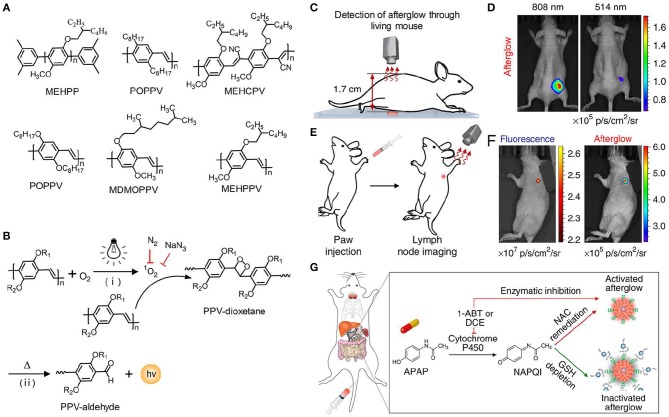

Although significant achievements in deep-tissue imaging have been made, inorganic afterglow nanoparticles may suffer from potential toxicity due to the existence of heavy metal ions (Toppari et al., 1996). Furthermore, the surface of inorganic nanoparticles is difficult to modify, thereby leading to the finite targeting ability. As an alternative, organic afterglow nanoparticles have attracted increasing interest due to their high biological safety, optical tunability, facile processability, and easy functionalization (An et al., 2015; Su et al., 2018). In 2015, Rao et al. reported the semiconducting polymer nanoparticles (SPNs) with afterglow luminescence that can last for an hour (Palner et al., 2015). However, the underlying mechanism of the afterglow phenomenon remained unrevealed. To resolve it, Pu et al. screened a series of semiconducting polymers and discovered that only phenylenevinylene (PPV)-based SPNs such as BOPPV, MDMOPPV, and MEHPPV had distinct afterglow luminescence, implying its essential role in the production of afterglow luminescence (Figure 5A; Miao et al., 2017). According to series of characterizations and analyses, the probable mechanism of afterglow luminescence for PPV-based SPNs was proposed as follows: the singlet oxygen (1O2) was generated by the light irradiation of PPVs and then oxidized the vinylene bond to form an unstable PPV-dioxetane intermediate, which could spontaneously decompose into PPV-aldehyde fragments along with photonic efflux (Figure 5B). To amplify the afterglow of SPNs and red-shift it into NIR region, NCBS, a NIR dye (778 nm) and 1O2 photosensitizer, was doped into SPN-MEHPPV to yield SPN-NCBS. The afterglow of SPN-NCBS could be increased by 11-fold under pre-irradiation at 808 nm compared to 514 nm due to the higher 1O2 generation ability of NCBS vs. MEHPPV. Due to the amplified brightness and lower background noise, the afterglow signal of SPN-NCBS could penetrate through a living mouse with a SBR of 237, which was 120 times higher than that of NIR fluorescence (Figures 5C,D). Then the SPN-NCBS was used for afterglow imaging of lymph nodes and tumors in living mice (Figure 5E). The afterglow of SPN-NCBS permitted more efficient and high-contrast imaging of lymph nodes and tumor relative to NIR fluorescence imaging, demonstrating its potential in guiding intraoperative surgical resection (Figure 5F). An overdose of drugs, take acetaminophen as an example, will induce oxidative stress after metabolization and in turn deplete antioxidants (i.e., biothiols) in body. Thus, imaging of biothiol levels can be a feasible way to evaluate drug-induced hepatotoxicity. To achieve this, a biothiol-activated afterglow probe was prepared for detecting drug-induced hepatotoxicity by introducing an electron-withdrawing quencher (2,4-dinitrophenylsulfonyl, DNBS) onto the surface of SPN-NCBS (Figure 5G). In the presence of biothiols, such as Cys, Hcy and GSH, DNBS was removed from the nanoprobe and then the electron transfer between the quencher and the afterglow moiety was restrained, leading to an activated afterglow. In vivo data proved that the probe permitted real-time afterglow imaging of drug-caused hepatotoxicity with an excellent SBR that is 25-fold higher than that of NIR fluorescence imaging.

Figure 5.

NIR afterglow luminescence imaging. (A) Chemical structures of MEHPP, POPPV, MEHCPV, BOPPV, MDMOPPV, and MEHPPV. (B) Illustration of the probable afterglow luminescence mechanism for PPV-based afterglow nanoparticles. (C) Illustration of tissue penetration experiment of SPN-NCBS through a living mouse (1.7 cm). (D) Representative afterglow images of SPN-NCBS solution through a living mouse with pre-irradiation of 808 or 514 nm laser. (E) Illustration of afterglow imaging experiment of a lymph node in living mice, after pre-irradiation with 808 nm laser for 1 min, the SPN-NCBS solution was stored in −20°C for 1 day and then was directly applied for lymph node imaging. (F) Representative afterglow (right) and fluorescence (left) images of lymph node in living mice. (G) Schematic illustration of SPN-NCBS with DNBS for detecting APAP-caused hepatotoxicity. The formation of N-acetylparaquinonimine (NAPQI) by metabolism of APAP with Cytochrome P450 can deplete GSH, leading to an inactivated afterglow. The antioxidant drug (N-acetyl-L-cysteine, NAC) and enzyme inhibitors (DCE or 1-ABT) remediate hepatotoxicity, causing an active afterglow (Reproduced with permission from Miao et al., 2017).

Strong hydrophobic polymer required amphiphilic polymer to form a water-soluble nanoparticle by co-precipitation, thus leading to large size (34 nm) that could be unfavorable for efficient accumulation in tumor. To solve it, Pu et al. prepared an amphiphilic PPV polymer with grafted poly(ethylene glycol) that could self-assemble into smaller nanoparticles (24 nm) in aqueous solution (Xie et al., 2018). The nanoparticles were further doped with NCBS to form SPPVN-NCBS. Compared with SPN-NCBS, SPPVN-NCBS had smaller size, stronger NIR afterglow luminescence and higher accumulation in tumor. The NIR afterglow of SPPVN-NCBS could clearly detect 1 mm3 xenografted tumors and invisible peritoneal metastatic tumors.

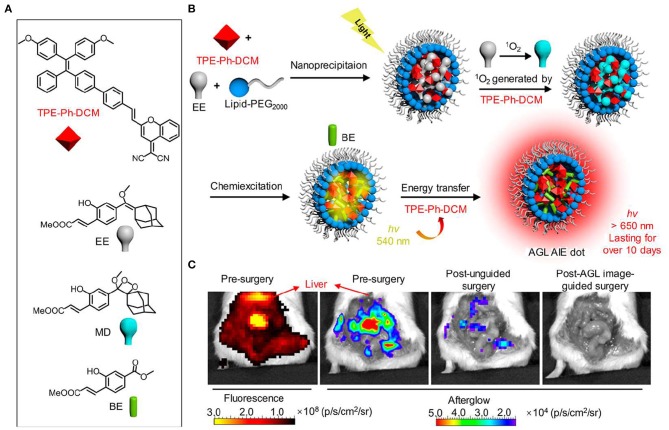

In a subsequent work, Pu et al. prepared a new library of afterglow luminescence agents by a generic approach that utilized an intraparticle cascade photoreaction of three main components (afterglow initiator, afterglow substrate and afterglow relay unit) (Jiang et al., 2019). By tuning the components, the afterglow emission could be adjusted from visible to NIR region. The representative NIR afterglow agents showed great imaging depth up to 5 cm, and permitted rapid detection of tumor in living mice with ultrahigh SBR (2,922 ± 121). Recently, Ding et al. reported the first aggregation-induced emission (AIE)-based NIR afterglow probe (AGL AIE dot) that could persist over 10 days (Figure 6; Ni et al., 2018b). This afterglow probe exhibited deep tissue penetration, high SBR, and ultrahigh signal ratios of tumor-to-reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs, thereby having the capability of image-guided cancer surgery in living mice. As shown in Figure 6C, the NIR afterglow imaging of AGL AIE dot could clearly differentiate the microtumors in peritoneal carcinomatosis-bearing mice, but the fluorescence imaging failed to do it. Moreover, under the guidance of the afterglow imaging, all the tiny tumor nodules could be nearly removed by surgery.

Figure 6.

NIR AIE-based afterglow luminescence imaging. (A) Chemical structures of compound TPE-Ph-DCM, compound EE, MD, and BE. (B) Schematic illustration for NIR afterglow luminescence mechanism of AQL AIE dot. Under the white light pre-irradiation, TPE-Ph-DCM produced 1O2 that can oxidize compound EE to obtain compound MD. The slow degradation of compound MD leads to the formation of compound BE, and then the energy is transferred back to TPE-Ph-DCM to induce the NIR afterglow emission. (C) Fluorescence and afterglow images of the abdominal cavity of living mice with peritoneal carcinomatosis. The abdomen of mice was opened at 2 h after intravenous injection of AGL AIE dots (reproduced with permission from Ni et al., 2018b).

Summary and Outlook

Self-luminescence including bioluminescence, chemiluminescence and afterglow have permitted imaging with higher sensitivity and deeper penetration depth than that obtained by fluorescence because it avoids the requirement of real-time light excitation and eliminates tissue autofluorescence. As NIR light possesses improved penetration depth than that obtained by visible light, many strategies via molecular- and nano-engineering approaches have been adopted to develop NIR self-luminescence. Stimulated by the merits, NIR self-luminescence imaging has been applied for in vivo detection of biological and pathological processes in living systems. With the development of new self-luminescence agents, the selectivity and sensitivity of bioluminescence, chemiluminescence and afterglow imaging tools have been dramatically improved.

Because bioluminescence, chemiluminescence and afterglow agents for deep-tissue optical imaging in living system is in the infancy, some challenges still need to be addressed. Firstly, the luminescence intensity of NIR self-luminescent agents is relatively low due to the limited efficiency to red-shift luminescence emission from visible to NIR window. Thus, it is necessary to explore new agents with evolving molecular- or nano-engineering strategy to obtain brighter luminescence. Secondly, compared with NIR-I light, NIR-II light has substantially lower light scattering, and thus increases the imaging sensitivity and tissue penetration depth (Jiang and Pu, 2018; Kenry et al., 2018). However, the second NIR (NIR-II, 1,000–1,700 nm) emitting self-luminescent agents have not been reported yet. We envision that new approaches will be developed to red-shift the emission of self-luminescent agent from NIR-I to NIR-II for advances of deep-tissue optical imaging. Thirdly, the majority of the reported NIR self-luminescent nanoagents have large size and are likely to retain in living organism for a long time, hence the long-term biosafety keeps unclear. To address this challenge, the nanoagents should be endowed with biodegradability and easily being cleared out by body. With the emergence of self-luminescent agents with high performance, it is confident that self-luminescence imaging will become a powerful tool in biology and clinical diagnosis of diseases.

Author Contributions

QM and MG conceived this manuscript. QL, QM, JZ, and MG wrote and edited this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SBR

signal-to-background ratio

- NIR

near-infrared

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography

- PET

positron emission tomography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CT

computed tomography

- PA

photoacoustic

- Fluc

firefly luciferase

- Gluc

Gaussia luciferase

- Rluc

Renilla luciferase

- Nluc

Nanoluc

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- QDs

quantum dots

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- MEHPPV

poly [2-methoxy-5-((2-ethylhexyl)oxy)-p-phenylenevinylene]

- NCBS

silicon 2,3-naphthalocyanine bis(trihexylsilyloxide)

- cRGD

cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- CRET

chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- CPPO

Bis-(2,4,5-trichloro-6-(pentyloxycarbonyl)phenyl) oxalate

- PFODBT

poly(2,7-(9,9′-dioctylfluorene)-alt-4,7-bis(thiophen-2-yl)benzo-2,1,3-thiadiazole)

- APAP

acetaminophen

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- TCPO

bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) oxalate

- HOMO

highest occupied molecular orbital

- LUMO

lowest unoccupied molecular orbital

- CIEEL

chemically initiated electron exchange luminescence

- QY

quantum yield

- Ce6

chlorin e6

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- DCMC

dicyanomethylene-4H-chromene

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- FA

formaldehyde

- SPNs

semiconducting polymer nanoparticles

- PPV

phenylenevinylene

- 1O2

singlet oxygen

- DNBS

2,4-dinitrophenylsulfonyl

- NAPQI

N-acetylparaquinonimine

- AIE

aggregation-induced emission

- RES

reticuloendothelial system.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Key Research Program of China (2018YFA0208800), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81901803, 21503141), Jiangsu Specially Appointed Professorship, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20191418, BK20190811, BK20190830), and Soochow University (Start-up grant: GJ12800119 and Q412800119).

References

- Abdukayum A., Chen J.-T., Zhao Q., Yan X.-P. (2013). Functional near infrared-emitting Cr3+/Pr3+ co-doped zinc gallogermanate persistent luminescent nanoparticles with superlong afterglow for in vivo targeted bioimaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14125–14133. 10.1021/ja404243v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai T., Shang W., Yan H., Zeng C., Wang K., Gao Y., et al. (2018). Near infrared-emitting persistent luminescent nanoparticles for hepatocellular carcinoma imaging and luminescence-guided surgery. Biomaterials 167, 216–225. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Z., Zheng C., Tao Y., Chen R., Shi H., Chen T., et al. (2015). Stabilizing triplet excited states for ultralong organic phosphorescence. Nat. Mater. 14, 685–690. 10.1038/nmat4259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antaris A. L., Chen H., Cheng K., Sun Y., Hong G., Qu C., et al. (2015). A small-molecule dye for nir-ii imaging. Nat. Mater. 15, 235–242. 10.1038/nmat4476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto F. A., de Souza G. A., de Souza Junior S. P., Khalid M., Baader W. J. (2013). Efficiency of electron transfer initiated chemiluminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. 89, 1299–1317. 10.1111/php.12102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr C. E., Tannous B. A. (2011). Bioluminescence imaging: progress and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 29, 624–633. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. (2010). Whole-animal imaging: the whole picture. Nature 463, 977–980. 10.1038/463977a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruemmer K. J., Green O., Su T. A., Shabat D., Chang C. J. (2018). Chemiluminescent probes for activity-based sensing of formaldehyde released from folate degradation in living mice. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7508–7512. 10.1002/anie.201802143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Campbell J., Liu L., Mason R. P., Lippert A. R. (2016). In vivo chemiluminescent imaging agents for nitroreductase and tissue oxygenation. Anal. Chem. 88, 4995–5002. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Zheng Z., Zhu Y., Dong Y., Wang F., Liang G. (2017). Bioluminescent turn-on probe for sensing hypochlorite in vitro and in tumors. Anal. Chem. 89, 5693–5696. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. S., Gibbs S. L., Lee J. H., Kim S. H., Ashitate Y., Liu F., et al. (2013). Targeted zwitterionic near-infrared fluorophores for improved optical imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 148–153. 10.1038/nbt.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin L., Sheibani S., Moassesi M. E., Shamsipur M. (2018). An overview of nanoscale radionuclides and radiolabeled nanomaterials commonly used for nuclear molecular imaging and therapeutic functions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 107A, 251–285. 10.1002/jbm.a.36550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnaim S., Scomparin A., Eldar-Boock A., Bauer C. R., Satchi-Fainaro R., Shabat D. (2019). Light emission enhancement by supramolecular complexation of chemiluminescence probes designed for bioimaging. Chem. Sci. 10, 2945–2955. 10.1039/C8SC05174G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green O., Eilon T., Hananya N., Gutkin S., Bauer C. R., Shabat D. (2017a). Opening a gateway for chemiluminescence cell imaging: distinctive methodology for design of bright chemiluminescent dioxetane probes. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 349–358. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green O., Gnaim S., Blau R., Eldar-Boock A., Satchi-Fainaro R., Shabat D. (2017b). Near-infrared dioxetane luminophores with direct chemiluminescence emission mode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13243–13248. 10.1021/jacs.7b08446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai Z., Wu J., Wang L., Xu J., Zhang H., Liang G. (2017). Bioluminescence sensing of γ-glutamyltranspeptidase activity in vitro and in vivo. Anal. Chem. 89, 7017–7021. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. P., Unch J., Binkowski B. F., Valley M. P., Butler B. L., Wood M. G., et al. (2012). Engineered luciferase reporter from a deep sea shrimp utilizing a novel imidazopyrazinone substrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 20127111848–20127111857. 10.1021/cb3002478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. P., Woodroofe C. C., Wood M. G., Que I., van't Root M., Ridwan Y., et al. (2018). Click beetle luciferase mutant and near infrared naphthyl-luciferins for improved bioluminescence imaging. Nat. Commun. 9:132. 10.1038/s41467-017-02542-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hananya N., Eldar Boock A., Bauer C. R., Satchi-Fainaro R., Shabat D. (2016). Remarkable enhancement of chemiluminescent signal by dioxetane–fluorophore conjugates: turn-on chemiluminescence probes with color modulation for sensing and imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13438–13446. 10.1021/jacs.6b09173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hananya N., Shabat D. (2017). A glowing trajectory between bio- and chemiluminescence: from luciferin-based probes to triggerable dioxetanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 16454–16463. 10.1002/anie.201706969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hananya N., Shabat D. (2019). Recent advances and challenges in luminescent imaging: bright outlook for chemiluminescence of dioxetanes in water. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 949–959. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M., Tsukasaki Y., Ohyanagi T., Jin T. (2013). Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer coupled near-infrared quantum dots using gst-tagged luciferase for in vivo imaging. Chem. Commun. 49, 228–230. 10.1039/C2CC36870F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G., Zou Y., Antaris A. L., Diao S., Wu D., Cheng K., et al. (2014). Ultrafast fluorescence imaging in vivo with conjugated polymer fluorophores in the second near-infrared window. Nat. Commun. 5:4206. 10.1038/ncomms5206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Haynes M. T., Wang Y., Liu F., Huang L. (2013). A highly efficient synthetic vector: nonhydrodynamic delivery of DNA to hepatocyte nuclei in vivo. ACS Nano 7, 5376–5384. 10.1021/nn4012384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Lin S., Wang Q., Zhang Y., Li C., Ji R., et al. (2019). An nir-ii fluorescence/dual bioluminescence multiplexed imaging for in vivo visualizing the location, survival, and differentiation of transplanted stem cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29:1806546 10.1002/adfm.201806546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwano S., Obata R., Miura C., Kiyama M., Hama K., Nakamura M., et al. (2013). Development of simple firefly luciferin analogs emitting blue, green, red, and near-infrared biological window light. Tetrahedron 69, 3847–3856. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.03.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jathoul A. P., Grounds H., Anderson J. C., Pule M. A. (2014). A dual-color far-red to near-infrared firefly luciferin analogue designed for multiparametric bioluminescence imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 13059–13063. 10.1002/anie.201405955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Huang J., Zhen X., Zeng Z., Li J., Xie C., et al. (2019). A generic approach towards afterglow luminescent nanoparticles for ultrasensitive in vivo imaging. Nat. Commun. 10:2064. 10.1038/s41467-019-10119-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Pu K. (2018). Molecular fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging in the second near-infrared optical window using organic contrast agents. Adv. Biosyst. 2:1700262 10.1002/adbi.201700262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokerst J. V., Gambhir S. S. (2011). Molecular imaging with theranostic nanoparticles. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 1050–1060. 10.1021/ar200106e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. A., Porterfield W. B., Rathbun C. M., McCutcheon D. C., Paley M. A., Prescher J. A. (2017). Orthogonal luciferase-luciferin pairs for bioluminescence imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2351–2358. 10.1021/jacs.6b11737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskova Z. M., Tsarkova A. S., Yampolsky I. V. (2016). 1001 lights: luciferins, luciferases, their mechanisms of action and applications in chemical analysis, biology and medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6048–6077. 10.1039/C6CS00296J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenry, Duan Y., Liu B. (2018). Recent advances of optical imaging in the second near-infrared window. Adv. Mater. 30:1802394. 10.1002/adma.201802394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchimaru T., Iwano S., Kiyama M., Mitsumata S., Kadonosono T., Niwa H., et al. (2016). A luciferin analogue generating near-infrared bioluminescence achieves highly sensitive deep-tissue imaging. Nat. Commun. 7:11856. 10.1038/ncomms11856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lécuyer T., Teston E., Ramirez-Garcia G., Maldiney T., Viana B., Seguin J., et al. (2016). Chemically engineered persistent luminescence nanoprobes for bioimaging. Theranostics 6, 2488–2524. 10.7150/thno.16589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. D., Lim C.-K., Singh A., Koh J., Kim J., Kwon I. C., et al. (2012). Dye/peroxalate aggregated nanoparticles with enhanced and tunable chemiluminescence for biomedical imaging of hydrogen peroxide. ACS Nano 6, 6759–6766. 10.1021/nn3014905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wang C., Shi J., Li P., Yu Z., Zhang H. (2018). Porous GdAlO3: Cr3+, Sm3+ drug carrier for real-time long afterglow and magnetic resonance dual-mode imaging. J. Luminescence 199, 363–371. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.03.071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Liu L., Xiao H., Zhang W., Wang L., Tang B. (2016). A new polymer nanoprobe based on chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer for ultrasensitive imaging of intrinsic superoxide anion in mice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2893–2896. 10.1021/jacs.5b11784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhou S., Li Y., Sharafudeen K., Ma Z., Dong G., et al. (2014). Long persistent and photo-stimulated luminescence in Cr3+-doped Zn–Ga–Sn–O phosphors for deep and reproducible tissue imaging. J. Mater. Chem. C 2:2657 10.1039/c4tc00014e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Zhang Y., Wu X., Huang L., Li D., Fan W., et al. (2015). Direct aqueous-phase synthesis of sub-10 nm “luminous pearls” with enhanced in vivo renewable near-infrared persistent luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5304–5307. 10.1021/jacs.5b00872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. K., Lee Y. D., Na J., Oh J. M., Her S., Kim K., et al. (2010). Chemiluminescence-generating nanoreactor formulation for near-infrared imaging of hydrogen peroxide and glucose level in vivo. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 2644–2648. 10.1002/adfm.201000780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert A. R. (2017). Unlocking the potential of chemiluminescence imaging. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 269–271. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Yan W., Chuang Y.-J., Zhen Z., Xie J., Pan Z. (2013). Photostimulated near-infrared persistent luminescence as a new optical read-out from Cr3+-doped liga5o8. Sci. Rep. 3:1554 10.1038/srep01554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Tang J., Xu Y., Dai Z. (2019). Bioluminescence imaging of inflammation in vivo based on bioluminescence and fluorescence resonance energy transfer using nanobubble ultrasound contrast agent. ACS Nano 13, 5124–5132. 10.1021/acsnano.8b08359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Cai W., He L., Nakayama N., Chen K., Sun X., et al. (2007). In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 47–52. 10.1038/nnano.2006.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Y., Cui D., Huang J., Fan W., Miao Y., Pu K. (2019). Near-infrared afterglow semiconducting nano-polycomplexes for the multiplex differentiation of cancer exosomes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 4983–4987. 10.1002/anie.201900092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N., Marshall A. F., Rao J. (2010). Near-infrared light emitting luciferase via biomineralization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6884–6885. 10.1021/ja101378g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Hou Y., Zeng J., Liu C., Zhang P., Jing L., et al. (2018). Dual-ratiometric target-triggered fluorescent probe for simultaneous quantitative visualization of tumor microenvironment protease activity and ph in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 211–218. 10.1021/jacs.7b08900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldiney T., Bessière A., Seguin J., Teston E., Sharma S. K., Viana B., et al. (2014). The in vivo activation of persistent nanophosphors for optical imaging of vascularization, tumours and grafted cells. Nat. Mater. 13, 418–426. 10.1038/nmat3908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldiney T., Lecointre A., Viana B., Bessière A., Bessodes M., Gourier D., et al. (2011). Controlling electron trap depth to enhance optical properties of persistent luminescence nanoparticles for in vivo imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11810–11815. 10.1021/ja204504w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M. R., Jaeschke H. (2013). Metabolism and disposition of acetaminophen: recent advances in relation to hepatotoxicity and diagnosis. Pharm. Res. 30, 2174–2187. 10.1007/s11095-013-1007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzanotte L., van ‘t Root M., Karatas H., Goun E. A., Löwik C. W. G. M. (2017). In vivo molecular bioluminescence imaging: New tools and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 35, 640–652. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Q., Pu K. (2018). Organic semiconducting agents for deep-tissue molecular imaging: second near-infrared fluorescence, self-luminescence, and photoacoustics. Adv. Mater. 30:1801778. 10.1002/adma.201801778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Q., Xie C., Zhen X., Lyu Y., Duan H., Liu X., et al. (2017). Molecular afterglow imaging with bright, biodegradable polymer nanoparticles. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1102–1110. 10.1038/nbt.3987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura C., Kiyama M., Iwano S., Ito K., Obata R., Hirano T., et al. (2013). Synthesis and luminescence properties of biphenyl-type firefly luciferin analogs with a new, near-infrared light-emitting bioluminophore. Tetrahedron 69, 9726–9734. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.09.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni D., Ehlerding E. B., Cai W. (2018a). Multimodality imaging agents with pet as the fundamental pillar. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2570–2579. 10.1002/anie.201806853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Zhang X., Duan X., Zheng H.-L., Xue X.-S., Ding D. (2018b). Near-infrared afterglow luminescent aggregation-induced emission dots with ultrahigh tumor-to-liver signal ratio for promoted image-guided cancer surgery. Nano Lett. 19, 318–330. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara R., Paulmurugan R., Nakajima T., Yamamoto E., Natarajan A., Afjei R., et al. (2019). Highly bright and stable nir-bret with blue-shifted coelenterazine derivatives for deep-tissue imaging of molecular events in vivo. Theranostics 9, 2646–2661. 10.7150/thno.32219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palner M., Pu K., Shao S., Rao J. (2015). Semiconducting polymer nanoparticles with persistent near-infrared luminescence for in vivo optical imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 11477–11480. 10.1002/anie.201502736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L. S., Lippert A. R. (2018). Ultrasensitivechemiluminescent detection ofcathepsin b: insights into the newfrontier of chemiluminescent imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 622–624. 10.1002/anie.201711228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Sun X., Li J., Man H., Shen J., Yu Y., et al. (2015). Multifunctional near infrared-emitting long-persistence luminescent nanoprobes for drug delivery and targeted tumor imaging. Biomaterials 37, 260–270. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Sun X., Zheng S., Li J., Fu X., Zhang H. (2018). A new near-infrared persistent luminescence nanoparticle as a multifunctional nanoplatform for multimodal imaging and cancer therapy. Biomaterials 152, 15–23. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimon G., Gammon S. T., Moss B. L., Rauch D., Harding J., Heinecke J. W., et al. (2009). Bioluminescence imaging of myeloperoxidase activity in vivo. Nat. Med. 15, 455–461. 10.1038/nm.1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuhendler A. J., Pu K., Cui L., Uetrecht J. P., Rao J. (2014). Real-time imaging of oxidative and nitrosative stress in the liver of live animals for drug-toxicity testing. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 373–380. 10.1038/nbt.2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So M.-K., Loening A. M., Gambhir S. S., Rao J. (2006a). Creating self-illuminating quantum dot conjugates. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1160–1164. 10.1038/nprot.2006.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So M.-K., Xu C., Loening A. M., Gambhir S. S., Rao J. (2006b). Self-illuminating quantum dot conjugates for in vivo imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 339–343. 10.1038/nbt1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S., Won M., Green O., Hananya N., Sharma A., Jeon Y., et al. (2019). Chemiluminescent probe for the in vitro and in vivo imaging of cancers over-expressing nqo1. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1739–1743. 10.1002/anie.201813032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Phua S. Z. F., Li Y., Zhou X., Jana D., Liu G., et al. (2018). Ultralong room temperature phosphorescence from amorphous organic materials toward confidential information encryption and decryption. Sci. Adv. 4:eaas9732. 10.1126/sciadv.aas9732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Hu Z., Wang R., Zhang S., Zhang X. (2018). A highly sensitive chemiluminescent probe for detecting nitroreductase and imaging in living animals. Anal. Chem. 91, 1384–1390. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Ding M., Zeng X., Xiao Y., Wu H., Zhou H., et al. (2017). Novel bright-emission small-molecule nir-ii fluorophores for in vivo tumor imaging and image-guided surgery. Chem. Sci. 8, 3489–3493. 10.1039/C7SC00251C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Nagai T. (2017). Recent progress in expanding the chemiluminescent toolbox for bioimaging. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 48, 135–141. 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Li Y., Lu X., Hu X., Zhao H., Hu W., et al. (2019a). Bio-erasable intermolecular donor-acceptor interaction of organic semiconducting nanoprobes for activatable nir-ii fluorescence imaging. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29:1807376 10.1002/adfm.201807376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Parag-Sharma K., Amelio A. L., Cao Y. (2019b). A bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-based approach for determining antibody-receptor occupancy in vivo. iScience 15, 439–451. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R., Ma H., Yang Q., Wan H., Zhu S., Chandra S., et al. (2019). Rational design of a super-contrast nir-ii fluorophore affords high-performance nir-ii molecular imaging guided microsurgery. Chem. Sci. 10, 326–332. 10.1039/C8SC03751E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Dhoble S. J. (2018). Recent advances and developments on integrating nanotechnology with chemiluminescence assays. Talanta 180, 1–11. 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppari J., Larsen J. C., Christiansen P., Giwercman A., Grandjean P., Guillette L. J. J., et al. (1996). Supplement 4 || male reproductive health and environmental xenoestrogens. Environ. Health Perspect. 104, 741–803. 10.2307/3432709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher M., Galván F. I., Ding B.-W., Schramm S., Berraud-Pache R., Naumov P., et al. (2018). Chemi- and bioluminescence of cyclic peroxides. Chem. Rev. 118, 6927–6974. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Fan Y., Li D., Sun C., Lei Z., Lu L., et al. (2019). Anti-quenching nir-ii molecular fluorophores for in vivo high-contrast imaging and ph sensing. Nat. Commun. 10:1058. 10.1038/s41467-019-09043-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihs F., Dacres H. (2019). Red-shifted bioluminescence resonance energy transfer: Improved tools and materials for analytical in vivo approaches. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 116, 61–73. 10.1016/j.trac.2019.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R., Pittet M. J. (2008). Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature 452, 580–589. 10.1038/nature06917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C., Zhen X., Miao Q., Lyu Y., Pu K. (2018). Self-assembled semiconducting polymer nanoparticles for ultrasensitive near-infrared afterglow imaging of metastatic tumors. Adv. Mater. 30:1801331. 10.1002/adma.201801331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L., Shuhendler A. J., Rao J. (2012). Self-luminescing bret-fret near-infrared dots for in vivo lymph-node mapping and tumour imaging. Nat. Commun. 3:1193. 10.1038/ncomms2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Chen R., Zheng C., Huang W. (2016). Excited state modulation for organic afterglow: materials and applications. Adv. Mater. 28, 9920–9940. 10.1002/adma.201602604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., An H., Zhang D., Tao H., Dou Y., Li X., et al. (2019). A self-illuminating nanoparticle for inflammation imaging and cancer therapy. Sci. Adv. 5:eaat2953. 10.1126/sciadv.aat2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Shi P., Song W., Bi S. (2019). Chemiluminescence and bioluminescence imaging for biosensing and therapy: in vitro and in vivo perspectives. Theranostics 9, 4047–4065. 10.7150/thno.33228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Zhang Y., Xiao F., Xia Z., Rao J. (2007). Quantum dot/bioluminescence resonance energy transfer based highly sensitive detection of proteases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 4346–4349. 10.1002/anie.200700280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z., Zhang B. S., Prescher J. A. (2018). Advances in bioluminescence imaging: new probes from old recipes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 45, 148–156. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Sun H., Zhang H., He L., Qiu L., Lin J., et al. (2019). Quantitatively visualizing tumor-related protease activity in vivo using a ratiometric photoacoustic probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3265–3273. 10.1021/jacs.8b13628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Wang L., Zhao Y., Wang F., Wu J., Liang G. (2018). Using bioluminescence turn-on to detect cysteine in vitro and in vivo. Anal. Chem. 90, 4951–4954. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X., Tao Y., An Z., Chen P., Xu C., Chen R., et al. (2017). Ultralong phosphorescence of water-soluble organic nanoparticles for in vivo afterglow imaging. Adv. Mater. 29:1606665. 10.1002/adma.201606665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X., Xie C., Pu K. (2018). Temperature-correlated afterglow of a semiconducting polymer nanococktail for imaging-guided photothermal therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3938–3942. 10.1002/anie.201712550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X., Zhang C., Xie C., Miao Q., Lim K. L., Pu K. (2016). Intraparticle energy level alignment of semiconducting polymer nanoparticles to amplify chemiluminescence for ultrasensitive in vivo imaging of reactive oxygen species. ACS Nano 10, 6400–6409. 10.1021/acsnano.6b02908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Tang W., Ren Y., Duan X. (2018). Chemiluminescence of conjugated-polymer nanoparticles by direct oxidation with hypochlorite. Anal. Chem. 90, 13714–13722. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]