Abstract

Background

With growing numbers of adults turning to the internet to get answers for health-related questions, online communities provide platforms with participatory networks to deliver health information and social support. However, to optimize the benefits of these online communities, these platforms must market effectively to attract new members and promote community growth.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the engagement results of Facebook advertisements designed to increase membership in the LungCancer.net online community.

Methods

In the fall of 2017, a series of 5 weeklong Facebook advertisement campaigns were launched targeting adults over the age of 18 years with an interest in lung cancer to increase opt ins to the LungCancer.net community (ie, the number of people who provided their email to join the site).

Results

The advertisements released during this campaign had a sum reach of 91,835 people, and 863 new members opted into the LungCancer.net community by providing their email address. Females aged 55 to 64 years were the largest population reached by the campaign (31,401/91,835; 34.29%), whereas females aged 65 and older were the largest population who opted into the LungCancer.net community (307/863; 35.57%). A total of US $1742 was invested in the Facebook campaigns, and 863 people opted into LungCancer.net, resulting in a cost of US $2.02 per new member.

Conclusions

This research demonstrates the feasibility of using Facebook advertising to promote and grow online health communities. More research is needed to compare the effectiveness of various advertising approaches. Public health professionals should consider Facebook campaigns to effectively connect intended audiences to health information and support.

Keywords: internet, health communication, social media, health promotion, health education

Introduction

Online Community Growth

Currently, 72% of adults seek health information on the Web, and 16% search for peers with similar health concerns [1]. Online communities can effectively extend health education [2,3] and facilitate social support [3,4] and have been linked to improved self-management [2] and enhanced health outcomes [3]. The number of online communities has grown substantially over the past decade, with countless websites increasing traffic from patients and caregivers through user-engaged communities [5]. Patients are motivated to join these communities to access support, advice, and accountability in reaching health goals [5-7]. Online community growth is crucial to meeting these user needs, as it builds communities’ pooled knowledge and increases access to quality informational and social support [5,8-11]. Larger online networks have the power of network effects—where more users increase the usefulness of the community [9]. For those seeking others with shared experiences, larger communities offer a greater number of individuals with the potential for cognitive empathy, particularly from people outside ones’ close network where sharing may cause emotional burden [12]. For staff overseeing these sites, limited evidence is available to guide community growth, which is known to be a time- and resource-intensive task [8].

LungCancer.net

In this study, we reported the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of Facebook advertising to promote online community growth in the context of the LungCancer.net community. LungCancer.net provides patients and caregivers a platform to learn, educate, and connect with peers and health care professionals. The content published by LungCancer.net is written by patients, caregivers, and health professionals and supplemented by editorial content. In August 2017, LungCancer.net catered to 1575 users and sought to expand their community base through a series of social media advertisements. With 69% of US adults on Facebook and 74% of users on the site daily [13,14], Facebook seemed to be an ideal platform to promote community growth. The goal of this study was to assess the engagement results of Facebook advertisements designed to increase the number of opt ins to the LungCancer.net online community (ie, the number of users that provided their email to join the community).

Methods

Facebook Advertisement Campaign

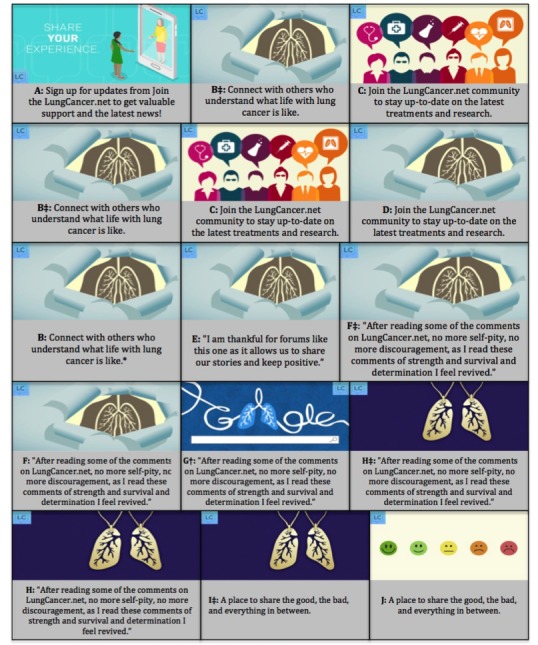

From August to December 2017, 5 weeklong Facebook campaigns were launched with the objective of increasing opt ins to LungCancer.net. Each campaign consisted of 3 unique advertisements that contained an image, a text, and a call to action (Figure 1). The visuals included 6 static images and 1 image in the Graphics Interchange Format (signaled with the “†” symbol in Figure 1). The text included messages crafted by community managers and quotes from members. The target audience was adults (18 years or older) with an interest in lung cancer–related content and/or Facebook pages. No other demographic variables were used to define the audience within the Facebook Ads Manager system. The budget for each advertisement was US $25 per day. Facebook utilizes a bidding cost system, and actual expenditures for each test averaged within 4% of the desired budget, with the exception of 1 outlying test, which was 19% below the budget.

Figure 1.

Facebook advertisement campaign images and text.

Advertisement Performance Measures

The performance of each advertisement was evaluated using metrics rooted in advertisement engagement frameworks [15-17]. According to McGuire’s Model of Persuasion, eliciting action begins with advertisement exposure and moves across a continuum of cognitive and behavioral responses [17]. Exposure in this campaign is operationalized as impressions (number of times the advertisement appears in News Feeds) and reach (number of individuals exposed to the advertisement). Frameworks proposed by Neiger et al [15] and Platt et al [16] were used to define low-to-high behavioral responses. As the goal of this campaign was to increase opt ins to the LungCancer.net community, low user engagement was defined as interacting with the advertisement through clicks (ie, reacting to the post, clicking a post link, or liking the LungCancer.net Facebook page), medium user engagement was defined as sharing or commenting on the advertisement, and high user engagement was defined as opting in or signing up for the LungCancer.net community. After each campaign, metrics (Table 1) were pulled for each advertisement, and advertisements with the lowest opt in cost were run with new advertisements during the next weeklong campaign. Advertisements with the lowest opt in cost during each weeklong campaign are signaled with the “‡” symbol in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Facebook advertisement performance measures.

| Level of performance | Level of engagement | Performance measure | Definition |

| Exposure | —a | Impressions | Number of times the advertisement appeared in News Feeds |

| Exposure | — | Reach | Number of individuals exposed to the Facebook advertisement |

| Engagement | Low | Reactions | Number of times people responded to an advertisement by clicking “like,” “love,” “wow,” “haha,” “sad,” or “angry” |

| Engagement | Low | Link clicks | Number of people who clicked a link on the Facebook advertisement |

| Engagement | Low | Page likes | Number of people who liked the LungCancer.net Facebook page |

| Engagement | Medium | Shares | Number of times people shared the advertisement |

| Engagement | Medium | Comments | Number of times people commented on the Facebook advertisement |

| Engagement | High | Opt ins | Number of people who signed up to join the LungCancer.net community |

aNot applicable.

Results

Audience Demographics

Over the course of the 5 campaigns, the sum reach was 91,835 people, and 863 members opted in to the LungCancer.net community (ie, demonstrated high engagement; Table 2). Females between 55 and 64 years represented the largest population reached by the campaign (31,401/91,835; 34.29%), whereas females aged 65 years and older represented the largest population that opted in to the LungCancer.net community (307/863; 35.57%). Given that US $1742 was invested across the 5 campaigns, approximately US $2.02 was spent per opt in, and just over 1 cent was spent per exposure to the campaign.

Table 2.

Demographic information of those exposed to Facebook advertisements.

| Age (years) | Cumulative campaign reach (N=91,835), n (%) | New members resulting from the campaign (N=863), n (%) | ||||

|

|

Female | Male | Unknown | Female | Male | Unknown |

| 65+ | 24,005 (26.14) | 5766 (6.28) | 163 (0.18) | 307 (35.57) | 66 (7.65) | 3 (0.35) |

| 55-64 | 31,401 (34.29) | 6572 (7.16) | 181 (0.20) | 257 (29.78) | 63 (7.30) | 3 (0.35) |

| 45-54 | 13,289 (14.47) | 2397 (2.61) | 62 (0.07) | 111 (12.86) | 14 (1.62) | 0 (0.00) |

| 35-44 | 4427 (4.82) | 975 (1.06) | 20 (0.02) | 23 (2.67) | 1 (0.12) | 0 (0.00) |

| 25-34 | 138 (1.50) | 404 (0.44) | 12 (0.01) | 7 (0.81) | 2 (0.23) | 0 (0.00) |

| 18-24 | 591 (0.64) | 115 (0.13) | 15 (0.01) | 6 (0.70) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 69 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

Advertisement Engagement Results

Table 3 displays engagement results. During the first campaign (August 24-30), advertisement B attracted the greatest level of engagement, including the greatest reach (10,556 people), number of impressions (12,569), reactions (221), link clicks (131), page likes (11), and opt ins (81 new community members) and the lowest opt in per cost rate (US $1.99 per opt in). This advertisement featured an image of lungs with the text “connect with others who understand what life with lung cancer is like.” Advertisements B and C were then used in the second campaign (August 31-September 6) alongside 1 new advertisement. In week 2, advertisement B again outperformed other advertisements and was subsequently implemented in week 3 (October 5-11).

Table 3.

Facebook advertisement engagement results.

| Ad | Exposure, n | Engagement, n | Cost/opt in rate (US $) | ||||||

| Reach | Impressions | Low | Medium | High (opt ins) | |||||

|

|

|

Reactions | Link clicks | Page likes | Shares | Comments |

|

||

| A | 7206 | 8972 | 83 | 81 | 6 | 16 | 9 | 34 | 5.10 |

| Ba | 10,556 | 12,569 | 221 | 131 | 11 | 44 | 6 | 81 | 1.99 |

| C | 8494 | 10,788 | 219 | 102 | 10 | 51 | 8 | 72 | 2.23 |

| Ba | 10,546 | 12,965 | 170 | 164 | 9 | 34 | 15 | 78 | 1.85 |

| C | 9326 | 11,944 | 173 | 113 | 10 | 37 | 13 | 55 | 2.64 |

| D | 6484 | 9235 | 238 | 121 | 10 | 35 | 8 | 61 | 1.86 |

| B | 6078 | 8091 | 94 | 116 | 3 | 35 | 13 | 48 | 1.89 |

| E | 4018 | 6293 | 195 | 126 | 10 | 22 | 5 | 60 | 1.51 |

| Fa | 4778 | 7262 | 194 | 176 | 9 | 26 | 19 | 82 | 1.10 |

| F | 4711 | 6313 | 151 | 134 | 10 | 33 | 11 | 60 | 1.73 |

| G | 3468 | 4530 | 141 | 75 | 7 | 23 | 5 | 35 | 2.53 |

| Ha | 3952 | 5519 | 179 | 138 | 14 | 31 | 9 | 60 | 1.47 |

| H | 4671 | 5987 | 189 | 110 | 14 | 25 | 13 | 43 | 2.45 |

| Ia | 4146 | 5472 | 171 | 114 | 22 | 23 | 8 | 50 | 1.89 |

| J | 3401 | 5067 | 184 | 88 | 4 | 17 | 15 | 44 | 2.12 |

| Total | 91,835 | 121,007 | 2602 | 1789 | 149 | 452 | 157 | 863 | 2.02 |

aSignals the highest performing ad (generated the most opt ins/cost) that was subsequently used in the next ad campaign.

During the third campaign, advertisement F, featuring the same image as advertisement B with new text “After reading some of the comments on LungCancer.net, no more self-pity, no more discouragement, as I read these comments of strength and survival and determination I feel revived” attracted the greatest number of reactions (194), comments (19), link clicks (176), and opt ins (82) at the lowest cost (US $1.10 per opt in). In the fourth campaign (November 9-15), advertisement H, with the same text as advertisement F but a simpler lung image, attracted the greatest engagement including 179 reactions, 14 page likes, and 60 opt ins at US $1.47 per opt in. In the fifth campaign (December 7-17), advertisement H was outperformed by an advertisement featuring the same image with the text, “A place to share the good, the bad, and everything in between” (advertisement I). Advertisement I attracted 114 link clicks, 22 page likes, and 50 opt ins at US $1.89 per opt in.

Discussion

Principal Findings

Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of utilizing Facebook advertising as a cost-efficient tool to grow online health communities. Across the 5 campaigns, 863 new members opted in to the LungCancer.net community, yielding an opt in rate (opt ins/reach) of 0.94% (863/91,835) and a cost/opt in rate of US $2.02. Although the cost-effectiveness of Facebook advertisements varies widely in recruitment literature [18-24], our cost is but slightly higher than the average cost per click of US $1.32 for health care advertisements on Facebook [25]. Although Facebook advertisements were a cost-efficient community growth tool in this study, other research provides mixed results regarding the effectiveness of Facebook advertising [18,19,26,27]. Some agree that Facebook is an efficient way to draw diverse audiences to health promotion interventions [19,26,27]. Others have found Facebook to be a useful tool to increase advertisement reach, yet the actual rate of results per reach remains low [18,26]. This may indicate that Facebook advertisements are more efficient than traditional approaches (eg, physician referral, direct mail, and email) for online community growth outside research recruitment, where strict eligibility criteria often narrow the target audience [18]. Additional research is needed to test this hypothesis and optimize strategies to grow online health communities. Although these findings do not provide for specific design recommendations to increase engagement, we found some support for promising features of advertisements that match suggestions in previous literature: use of direct quotes/testimonials [28,29]; explicit reference to social support available in the community [6]; and simple lung images that are likely to be easily interpreted as relevant [30] to those seeking lung cancer communities.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this research provides foundational knowledge regarding the feasibility of Facebook advertisements to grow the LungCancer.net community, the findings are limited to the advertisement images and text used. Additional research is needed to systematically compare engagement with different images, texts, channels, and times of year to identify strategies associated with optimal community growth. Research is also needed to identify the impact that community growth through Facebook advertisements has on community engagement. Users who respond to a Facebook advertisement already demonstrate online engagement and may be more likely to contribute to an online health community than members recruited through other traditional strategies. Finally, given suggestions that Facebook advertising can effectively engage hardly reached populations in health education and intervention [15,18-20,27,31,32], additional research is needed to identify the sociodemographic characteristics of those engaged. Data presented here demonstrate a campaign that engaged primarily ageing female populations, representative of the current LungCancer.net site visitors (61% female and 55 years and above).

Conclusions

This study provides a foundation for research to optimize the reach of online health communities. Facebook was a feasible, cost-effective recruitment channel for this online community, and evaluation of other advertisement designs may provide further evidence for promising engagement strategies. Online communities are vital to health promotion efforts as multiple populations seek low-cost, easily accessible health resources. Focusing on expanding the reach of such communities could have major implications for the health of future populations.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA128582.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: AB and SH are employees of Health Union, LLC.

References

- 1.Fox S. Pew Research Center. 2014. [2019-09-17]. The Social Life of Health Information http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/15/the-social-life-of-health-information/

- 2.Willis E. The making of expert patients: the role of online health communities in arthritis self-management. J Health Psychol. 2014 Dec;19(12):1613–25. doi: 10.1177/1359105313496446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright KB. Communication in health-related online social support groups/communities: a review of research on predictors of participation, applications of social support theory, and health outcomes. Rev Commun Res. 2016;4:65–87. doi: 10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2016.04.01.010. doi: 10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2016.04.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moon TJ, Chih MY, Shah DV, Yoo W, Gustafson DH. Breast cancer survivors’ contribution to psychosocial adjustment of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in a computer-mediated social support group. Journalism Mass Commun Q. 2017 Jan 19;94(2):486–514. doi: 10.1177/1077699016687724. http://paperpile.com/b/M3TsPr/KJNd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malanga E, Malanga V, Latham S. Websites, online communities and digital channels as a medium to effectively educate, engage and empower patients. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018 Oct 17;5(4):334–7. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.5.4.2018.0158. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.5.4.2018.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solberg LB. The benefits of online health communities. Virtual Mentor. 2014 Apr 1;16(4):270–4. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.04.stas1-1404. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/benefits-online-health-communities/2014-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman MW, Lauterbach D, Munson SA, Resnick P, Morris ME. It's Not That I Don't Have Problems, I'm Just Not Putting Them on Facebook: Challenges and Opportunities in Using Online Social Networks for Health. Proceedings of the ACM 2011 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work; CSCW'11; March 19-23, 2011; Proceedings of the Acm 2011 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. 2011. pp. 341–50. https://tinyurl.com/y6trecr2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young C. Community management that works: how to build and sustain a thriving online health community. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Jun 11;15(6):e119. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2501. https://www.jmir.org/2013/6/e119/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin KY, Lu HP. Why people use social networking sites: an empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Comput Hum Behav. 2011 May;27(3):1152–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akar E, Mardikyan S. User roles and contribution patterns in online communities: a managerial perspective. Sage Open. 2018 Aug 22;8(3):215824401879477. doi: 10.1177/2158244018794773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler BS. Membership size, communication activity, and sustainability: a resource-based model of online social structures. Inf Syst Res. 2001 Dec;12(4):346–62. doi: 10.1287/isre.12.4.346.9703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Small ML. Weak ties and the core discussion network: why people regularly discuss important matters with unimportant alters. Social Networks. 2013 Jul;35(3):470–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2013.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pew Research Center. 2019. [2019-09-17]. Social Media Fact Sheet https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/

- 14.Smith A, Anderson M. Pew Research Center. 2018. [2019-09-17]. Social Media Use in 2018 https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/

- 15.Neiger BL, Thackeray R, van Wagenen SA, Hanson CL, West JH, Barnes MD, Fagen MC. Use of social media in health promotion: purposes, key performance indicators, and evaluation metrics. Health Promot Pract. 2012 Mar;13(2):159–64. doi: 10.1177/1524839911433467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Platt T, Platt J, Thiel DB, Kardia SL. Facebook advertising across an engagement spectrum: a case example for public health communication. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016 May 30;2(1):e27. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5623. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2016/1/e27/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuire WJ. Theoretical foundations of campaigns. In: Rice RE, Atkin CK, editors. Public Communication Campaigns. Second Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1989. pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frandsen M, Thow M, Ferguson SG. The effectiveness of social media (Facebook) compared with more traditional advertising methods for recruiting eligible participants to health research studies: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016 Aug 10;5(3):e161. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5747. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2016/3/e161/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane TS, Armin J, Gordon JS. Online recruitment methods for web-based and mobile health studies: a review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Jul 22;17(7):e183. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4359. https://www.jmir.org/2015/7/e183/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung SY, Hacker ED, Rawl S, Ellis R, Bakas T, Jones J, Welch J. Using Facebook in recruiting kidney transplant recipients for a REDCap study. West J Nurs Res. 2019 Mar 5;:-. doi: 10.1177/0193945919832600. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guthrie KA, Caan B, Diem S, Ensrud KE, Greaves SR, Larson JC, Newton KM, Reed SD, LaCroix AZ. Facebook advertising for recruitment of midlife women with bothersome vaginal symptoms: a pilot study. Clin Trials. 2019 Oct;16(5):476–80. doi: 10.1177/1740774519846862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, Jayasinghe Y, Fletcher A, Tabrizi SN, Gunasekaran B, Wark JD. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012 Feb 1;14(1):e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1978. https://www.jmir.org/2012/1/e20/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akard TF, Wray S, Gilmer MJ. Facebook advertisements recruit parents of children with cancer for an online survey of web-based research preferences. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(2):155–61. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000146. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24945264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornton LK, Harris K, Baker AL, Johnson M, Kay-Lambkin FJ. Recruiting for addiction research via Facebook. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016 Jul;35(4):494–502. doi: 10.1111/dar.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irvine M. WordStream: Online Advertising Made Easy. 2019. [2019-09-17]. Facebook Ad Benchmarks for Your Industry https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2017/02/28/facebook-advertising-benchmarks.

- 26.Topolovec-Vranic J, Natarajan K. The use of social media in recruitment for medical research studies: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Nov 7;18(11):e286. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5698. https://www.jmir.org/2016/11/e286/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen ER, Kurz J. Using Facebook for health-related research study recruitment and program delivery. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016 May;9:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.011. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26726313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis KC, Nonnemaker JM, Farrelly MC, Niederdeppe J. Exploring differences in smokers' perceptions of the effectiveness of cessation media messages. Tob Control. 2011 Jan;20(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.035568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wit JBF, Das E, Vet R. What works best: objective statistics or a personal testimonial? An assessment of the persuasive effects of different types of message evidence on risk perception. Health Psychol. 2008 Jan;27(1):110–5. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, Schumann D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: the moderating role of involvement. J Consum Res. 1983 Sep;10(2):135. doi: 10.1086/208954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha K, Weber I, Birnbaum ML, de Choudhury M. Characterizing awareness of schizophrenia among Facebook users by leveraging Facebook advertisement estimates. J Med Internet Res. 2017 May 8;19(5):e156. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6815. https://www.jmir.org/2017/5/e156/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn PH, Woo BK. Facebook recruitment of Chinese-speaking participants for hypertension education. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018 Sep;12(9):690–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]