Abstract

Background

Oral toxicities, such as mucositis and stomatitis, are some of the most significant and unavoidable side effects associated with anticancer therapies. In past decades, research has focused on newer targeted agents with the aim of decreasing the rates of side effects on healthy cells. Unfortunately, even targeted anticancer therapies show significant rates of toxicity on healthy tissue. mTOR inhibitors display some adverse events, such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypophosphatemia, hematologic toxicities, and mucocutaneous eruption, but the most important are still stomatitis and skin rash, which are often dose-limiting side effects.

Aim

This review was performed to answer the question “What is the incidence of stomatitis in patients treated with everolimus?”

Methods

We conducted a systematic search on the PubMed and Medline online databases using a combination of MESH terms and free text: “everolimus” (MESH) AND “side effects” OR “toxicities” OR “adverse events”. Only studies fulfilling the following inclusion criteria were considered eligible for inclusion in this study: performed on human subjects, reporting on the use of everolimus (even if in combination with other drugs or ionizing radiation), written in the English language, and reporting the incidence of side effects.

Results

The analysis of literature revealed that the overall incidence of stomatitis after treatment with everolimus was 42.6% (3,493) and that of stomatitis grade G1/2 84.02% (2,935), while G3/4 was 15.97% (558).

Conclusion

Results of the analysis showed that the incidence of stomatitis of grade 1 or 2 is higher than grade 3 or 4. However, it must be taken into account that it is not possible to say if side effects are entirely due to everolimus therapy or combinations with other drugs.

Keywords: stomatitis, everolimus, mucositis, targeted therapy, oral medicine, oral pathology

Introduction

Conventional anticancer therapy does not distinguish between normal and cancer cells. The damage inflicted on normal tissue have thus hampered this therapy.1 The introduction of targeted-therapy molecules targeting specific enzymes, growth-factor receptors, and signal transducers has lowered the incidence of side effects,2 significantly influencing patient quality of life and survival rates.2mTOR is a therapeutic target for both solid and hematologic malignancies. It is part of a pathway that regulates protein biosynthesis, cell growth, and cell-cycle progression. Moreover, mTOR is the downstream effector of the PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway, which regulates cell growth and metabolism and is involved in multiple processes.1,3–5

Rapamycin and its analogues form the first generation of mTOR inhibitors. The action of these molecules is targeting a 289 kDa serine/threonine-protein kinase that is a component of the big family of PI3Ks. Rapamycin and its analogues work by inhibiting the activity of mTORC1 through binding to FKBP12 and the establishment of a ternary complex with mTOR.6Actually, there are three available mTOR inhibitors: everolimus, temsirolimus, and ridaforolimus. Everolimus is currently used for the treatment of advanced hormone receptor–positive HER2-negative breast cancer together with exemestane, renal-cell carcinoma after failure of therapies based on sunitinib or sorafenib, progressive neuroendocrine tumors of pancreatic origin, in combination with exemestane, and subependymal giant-cell astrocytoma.

These drugs have a different spectrum of side effects compared to conventional chemotherapy. Common side effects are anemia, fatigue, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, stomatitis, rash, and thrombocytopenia.5,7 The terms “oral mucositis” and “stomatitis” are both used to describe inflammation and ulceration of the oral mucosal lining due to chemotherapy or ionizing radiation. However, stomatitis associated with mTOR inhibitors should be considered a separate entity this often being designated as mTOR inhibitor–associated stomatitis (mIAS).8,9 Mouth lesions present as superficial, ovoid, well-demarcated singular or multiple ulcers with a grayish white pseudomembrane. Their size often does not exceed 0.5 cm in diameter. Lesions typically involve the nonkeratinized mucosa, like the inner aspect of the lips, the ventral and lateral surfaces of the tongue, and the soft palate. Ulcers generally develop in 5 days and usually heal spontaneously in 1 week, most frequently in the first cycle of mTOR-inhibitor therapy.10

Methods

This review was performed to answer to the question “Which is the rate of incidence of stomatitis in patients treated with everolimus?” A systematic search on the online databases PubMed and Medline was conducted using a combination of MESH terms and free-text words: “everolimus” (MESH) AND “side effects” OR “toxicities” OR “adverse events”. The authors included in this study only reports that fulfilled certain criteria: performed on human subjects, everolimus alone or in combination with other drugs/ionizing radiation, written in the English language, and providing incidence of side effects. No restrictions were applied on year of publication. Reviews, case reports, and studies in vitro or performed on animal models were excluded. Information collected comprised name of first author, year, title, number of patients enrolled, and number and grade of events recorded. In addition, data were independently extracted by two authors (CA and LLM) and checked in a joint session.

Results

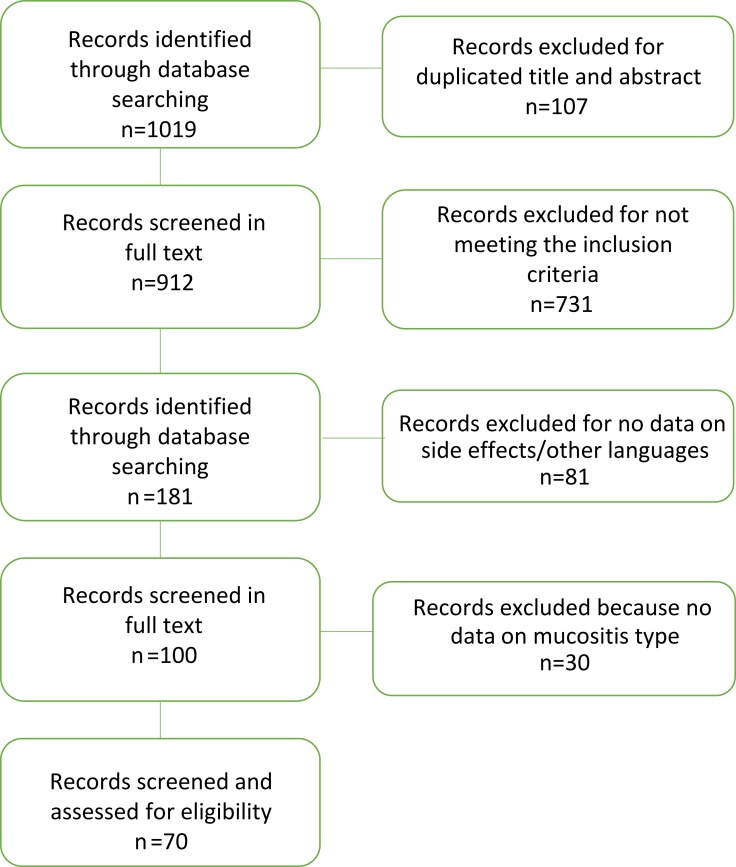

Our literature search yielded 1,019 potentially relevant studies. After elimination of duplicates, titles and abstracts of 912 potentially relevant studies were screened. Of these, 731 were not considered because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 181 studies were read in full text. Of these, only 100 reported on stomatitis or oral mucositis, and 30 were excluded due to lack of data (Figure 1). Results howed that the overall incidence of stomatitis after treatment with everolimus was 42.6% (3,493), stomatitis grade G12 84.02% (2,935), and G34 15.97% (558, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the process of paper selection used in this review.

Table 1.

Papers About Everolimus And Stomatitis

| Study | Year | Title | Therapy | Patients, n | Stomatitis, n (%) | G1/2, n (%) | G3/4, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amato et al27 | 2009 | A phase 2 study with a daily regimen of the oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer | Everolimus at a dose of 10 mg daily orally without interruption (28-day cycle), with dose modifications for toxicity (graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0). Patients were evaluated every two cycles (8 weeks) using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) | 39 | 12 (30.8) | G1 4 (10.3) G2 8 (20.5) |

|

| Andre et al28 | 2014 | Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial | In this randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial, authors recruited women with HER2-positive, trastuzumab-resistant advanced breast carcinoma who had previously received taxane therapy. Eligible patients were randomly assigned (1:1) using a central patient-screening and -randomization system to daily everolimus (5 mg/day) plus weekly trastuzumab (2 mg/kg) and vinorelbine (25 mg/m2) or to placebo plus trastuzumab plus vinorelbine, in 3-week cycles, stratified by previous lapatinib use | 280 | 175 (62) | 138 (49) | G3 37 (13) |

| Angelousi et al29 | 2017 | Sequential everolimus and sunitinib treatment in pancreatic metastatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours resistant to prior treatments | A: 20 1st-line everolimus B: 11 2nd-line everolimus |

A: 20 B: 11 |

A: 2 (10) B: 1 (9) |

A: 2 (10) B: 1 (9) |

|

| Armstrong et al30 | 2016 | Everolimus versus sunitinib for patients with metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ASPEN — a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2 trial) | Everolimus orally at 10 mg once daily | 52 | 27 (48) | 22 (39) | G3 5 (9) |

| Bajetta et al31 | 2014 | Everolimus in combination with octreotide long-acting repeatable in a first-line setting for patients with neuroendocrine tumors | Treatment-naïve patients with advanced well-differentiated NETs of gastroenteropancreatic tract and lung origin received everolimus 10 mg daily in combination with octreotide LAR 30 mg every 28 days | 50 | 31 | 26 (52) | G3 4 (8) G4 1 (2) |

| Baselga et al32 | 2012 | Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer | Double-blind phase III study, patients randomly assigned to treatment with oral everolimus or matching placebo (10 mg daily) in conjunction with exemestane (25 mg daily) | 482 | 56 (11.61) | 48 (9.95) | G3 8 |

| Baselga et al33 | 2009 | Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimusplus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole inpatients with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer | 270 postmenopausal women with operable ER-positive breast cancer were randomly assigned to receive 4 months of neoadjuvant treatment with letrozole (2.5 mg/day) and either everolimus (10 mg/day) or placebo | 137 | 50 (36.5) | 47 (34.3) | 3 (2.2) |

| Bergmann et al34 | 2015 | Everolimus in metastatic renal cell carcinoma after failure of initial anti–VEGF therapy: final results of a noninterventional study |

Patients received everolimus 10 mg once daily until disease progression or unacceptable | 334 | 22 (7) | 18 (81) | 4 (18) |

| Besse et al35 | 2014 | Phase II study of everolimus–erlotinib in previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer | Everolimus 5 mg/day + erlotinib 150 mg/day | 66 | 48 (72.6) | G1 11 (16.7) G2 16 (24.2) | G3 21 (31.8) |

| Campone et al36 | 2009 | Safety and pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in advanced solid tumours | Everolimus was dose-escalated from 15 to 30 mg and administered with paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 5 (31.25) | G3 1 (6.25) |

| Castellano et al37 | 2013 | Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable in patients with colorectal neuroendocrine tumors: a subgroup analysis of the phase III RADIANT-2 study | Everolimus plus octreotide | 19 | 11 (57.9) | ||

| Chan et al38 | 2013 | A prospective, phase 1/2 study of everolimus and temozolomide in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | Patients treated with temozolomide 150 mg/m2 per day on days 1–7 and 15–21 in combination with everolimus daily in each 28-day cycle. In cohort 1, temozolo mide was administered together with everolimus at 5 mg daily. Following demonstration of safety in this cohort, subsequent patients in cohort 2 were treated with temozolomide plus everolimus at 10 mg daily | 43 | 27 | G1 22 (51) G2 4 (9) |

G3 1 (2) |

| Choueiri et al39 | 2015 | Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma | Everolimus at a dose of 10 mg daily | 322 | 77 (24) | 70 (21.7) | 7 (2.2) |

| Chow et al40 | 2016 | A phase 2 clinical trial of everolimus plus bicalutamide for castration-resistant prostate cancer | Oral bicalutamide 50 mg and oral everolimus 10 mg, both once daily, with a cycle defined as 4 weeks | 24 | 14 (58.3) | 10 (41.6) | G3 4 |

| Chung et al41 | 2016 | Phase Ib trial of mFOLFOX6 and everolimus (NSC-733,504) in patients with metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma | Six patients were accrued to the first dose level of 2.5 mg everolimus daily with mFOLFOX6 | A: 6 | 4 (66) | G1 2 (33) | G3 2 (33) |

| Ciruelos et al42 | 2017 | Safety of everolimus plus exemestane in patients with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: results of phase IIIb BALLET trial in Spain | Eligible patients started study treatment on day 1 with daily doses of everolimus (2/5/9 mg or 1/9/10 mg) and exemestane (25 mg) and continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity | 429 | 272 (63) | 232 (54) | G3 40 (9) |

| Ciunci et al43 | 2014 | Phase 1 and pharmacodynamic trial of everolimus in combination with cetuximab in patients with advanced cancer | Not reported | 29 | 4 (13.8) | G2 4 (13.8) | |

| Colon-Otero et al44 | 2017 | Phase 2 trial of everolimus and letrozole in relapsed estrogen receptor-positive high-grade ovarian cancer | Patients received oral everolimus 10 mg daily and letrozole 2.5 mg daily | 19 | 2 (10.5) | G3 2 (10.5) | |

| Courtney et al45 | 2015 | A phase I study of everolimus and docetaxel in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer | Patients received everolimus 10 mg daily for 2 weeks and underwent a restaging FDG- PET/computed tomography scan. Patient cohorts were subsequently treated at three dose levels of everolimus with docetaxel: 5–60 mg/m2, 10–60 mg/m2, and 10–70 mg/m2. The primary end point was the safety and tolerability of combination therapy. | 18 | 5 (27.7) | 5 (27.7) | |

| Deenen et al46 | 2012 | Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of capecitabine and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid malignancies | Fixed-dose everolimus 10 mg/day continuously plus capecitabine twice daily for 14 days in 3-weekly cycles | 18 | 9 (50) | 9 (50) | |

| Doi et al47 | 2010 | Multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with previously treated metastatic gastric cancer | Everolimus 10 mg orally daily | A: 53 | 3 (5.7) | ||

| Elmadani et al48 | 2017 | EVESOR, a model-based, multiparameter, phase I trial to optimize the benefit/toxicity ratio of everolimus and sorafenib | Everolimus + sorafenib | 26 | 6 (23.1) | 6 (23.1) | |

| Escudier at al.49 | 2016 | Open-label phase 2 trial of first-line everolimus monotherapy in patients with papillary metastatic renal cell carcinoma: RAPTOR final analysis | Oral everolimus 10 mg once daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity | 92 | 23 (25) | 23 (25) | |

| Fazio et al50 | 2013 | Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable in patients with advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors: analysis of the phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled RADIANT-2 study |

Everolimus + octreotide | 33 | 3 (9.1) | ||

| Ferolla et al51 | 2017 | Efficacy and safety of long-acting pasireotide or everolimus alone or in combination in patients with advanced carcinoids of the lung and thymus (LUNA): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial | A: everolimus B: everolimus + pasireotide |

A: 42 B: 41 |

Total A: 30 (72) Total B: 15 (37) |

A: 26 (62) B: 13 (32) |

A: G3 4 (10) B: G3 2 (5) |

| Finn et al52 | 2013 | Phase I study investigating everolimus combined with sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma | A: sorafenib + everolimus 2.5 mg once daily B: sorafenib + everolimus 5 mg once daily |

A: 16 B: 14 |

A: 6 (37.5) B: 6 (42.9) Ulcers total 6 (37.5) |

A: 6 (37.5) B: 5 (35.8) |

A: 0 B: 1 (7.1) |

| Fury et al53 | 2012 | A phase I study of daily everolimus plus low-dose weekly cisplatin for patients with advanced solid tumors | Not reported | 30 | 11 (39) | 11 (39) | |

| Ghobrial et al54 | 2010 | Phase II trial of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in relapsed or refractory Waldenström macroglobulinemia | Everolimus 10 mg daily for two cycles | 50 | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | |

| Goldberg et al55 | 2015 | Everolimus for the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a phase II study | Not reported | 24 | 18 (75) | ||

| Gong et al56 | 2017 | Efficacy and safety of everolimus in Chinese metastatic HR positive, HER2 negative breast cancer patients: a real-world retrospective study | Everolimus was usually initiated at 10 mg or in some instances 5 mg daily, according to patients’ tolerance and request | 70 | 40 (57.1) | 34 (47.8) | G3 6 (9.3) |

| Grignani et al57 | 2015 | Sorafenib and everolimus for patients with unresectable high-grade osteosarcoma progressing after standard treatment: a non-randomised phase 2 clinical trial | A: patients took 400 mg sorafenib twice a day together with 5 mg everolimus once a day | 38 | 20 | G1 11 (29) G2 7 (18) |

G3 2 (5) |

| Hainsworth et al58 | 2010 | Phase II trial of bevacizumab and everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma | All patients received bevacizumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks and everolimus 10 mg orally daily | 80 | 48 | 36 (45) | G3 12 (15) |

| Hatano et al59 | 2016 | Outcomes of everolimus treatment for renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: a single institution experience in Japan |

Everolimus set at 10 mg once a day for adults | 47 | 43 (91) | 42 (97.6) | 1 (2.3) |

| Hatano et al60 | 2017 | Intermittent everolimus administration for renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex | Everolimus set at 10 mg once a day | 26 | 23 (88) | 22 | 1 |

| Hurvitz et al61 | 2013 | A phase 2 study of everolimus combined with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in patients with HER2-overexpressing advanced breast cancer that progressed during prior trastuzumab and taxane therapy | Everolimus 10 mg/day in combination with paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks) and trastuzumab (4 mg/kg loading dose followed by 2 mg/kg weekly), administered in 28-day cycles | 55 | 42 (76.3) | G1 13 (23.6)G2 18 (32.7) | G3 11 (20) |

| Jerusalem et al62 | 2016 | Safety of everolimus plus exemestane in patients with hormone-receptor–positive, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer progressing on prior non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors: primary results of a phase IIIb, open-label, single-arm, expanded-access multicenter trial (BALLET) | Not reported | 2,131 | 1,126 (52.8) | 926 (43.4) | G3 198 (9.3) G4 2 (0.1) |

| Jovanovic et al63 | 2017 | A randomized phase II neoadjuvant study of cisplatin, paclitaxel with or without everolimus in patients with stage II/III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): responses and long-term outcome correlated with increased frequency of DNA damage response gene mutations, TNBC subtype, AR status and Ki67 | Not reported | 96 | 37 (39) | 37 (39) | |

| Jozwiak et al64 | 2016 | Safety of everolimus in patients younger than 3 years of age: results from EXIST-1, a randomized, controlled clinical trial | Everolimus initiated at 4.5 mg/m2/day and titrated to blood trough levels of 5–15 ng/mL | 18 | 12 (66.7) | ||

| Kato et al65 | 2014 | Efficacy of everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to VEGFR-TKIs and safety compared with prior VEGFR-TKI treatment | Not reported | 19 | 7 (37) | 6 (32) | 1 (5) |

| Kim et al66 | 2014 | A multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with progressive unresectable adenoid cystic carcinoma | Everolimus given at 10 mg daily until progression or occurrence of unacceptable toxicities | 34 | 27 (79.4) | 26 (96.2) | 1 (2.9) |

| Kim et al67 | 2018 | Clinical outcomes of the sequential use of pazopanib followed by everolimus for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a multicentre study in Korea |

Everolimus | 36 | 15 (41.7) | 14 (38.9) | 1 (2.8) |

| Koutsoukos et al68 | 2017 | Real-world experience of everolimus as second-line treatment in metastatic renal cell cancer after failure of pazopanib | Not reported | 31 | 8 (26) | G1 4 (13) G2 1 (3) |

G3 3 (10) |

| Kulke et al69 | 2017 | A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of everolimus in combination with pasireotide LAR or everolimus alone in advanced, well-differentiated, progressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: COOPERATE-2 trial | A: everolimus + pasireotide LAR B: everolimus |

A: 78 B: 81 |

A: 46 (59) B: 51 (63) |

A: 39 (50) B: 44 (54.4) |

A: 7 (9) B: 7 (8.6) |

| Kumano et al70 | 2013 | Sequential use of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma following failure of tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

Everolimus | 57 | 17 (29.8) | 14 (82.35) | 3 (5.3) |

| Moscetti et al71 | 2016 | Safety analysis, association with response and previous treatments of everolimus and exemestane in 181 metastatic breast cancer patients: a multicenter Italian experience | Not reported | 181 | 115 (63.5) | G1 54 (29.8) G2 46 (25.4) | G3 15 (8.3) |

| Motzer et al72 | 2016 | Phase II trial of second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RECORD-4)† | Not reported | 133 | 7 (5.26) | ||

| Motzer et al73 | 2014 | Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line everolimus and second-line sunitinib versus first-line sunitinib and second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Everolimus | 238 | 53 (22.26) | 47 (19.74) | G3 6 (2.52) |

| Motzer et al17 | 2008 | Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial |

Everolimus 10 mg once daily | 269 | 107 (40) | 98 (36.43) | G3 9 (3.34) |

| Motzer et al74 | 2015 | Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial | Everolimus 10 mg day | 50 | 21 (42) | 20 (40) | G3 1 (2) |

| Oh et al75 | 2012 | Phase 2 study of everolimus monotherapy in patients with nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors or pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas | Everolimus was administered daily at a dose of 10 mg for 4 weeks. | 34 | 6 (17.6) | 4 (11.7) | 2 (5.9) |

| Ohtsu et al76 | 2013 | Everolimus for previously treated advanced gastric cancer: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III GRANITE-1 study | Everolimus 10 mg/day + BSC | 437 | 174 (40) | 154 (35) | 20 (5) |

| Ohyama et al77 | 2017 | Efficacy and safety of sequential use of everolimus in Japanese patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma after failure of first-line treatment with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: a multicenter phase II clinical trial |

Not reported | A :53 | 26 (49.1) | 22 (41.6) | 4 (7.5) |

| Panzuto et al78 | 2014 | Real-world study of everolimus in advanced progressive neuroendocrine tumors | Everolimus | 169 | 37 (21.9) | 33 (19.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Park et al79 | 2014 | Efficacy and safety of everolimus in Korean patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma following treatment failure with a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

Everolimus | 100 | 42 (44) | 36 (38) | 6 (6) |

| Pavel et al80 | 2016 | Safety and QOL in patients with advanced NET in a phase 3b expanded access study of everolimus | Not reported | 123 | 29 (23.6) | 23 (18.7) | G3 6 (4.9) |

| Quek et al81 | 2011 | Combination mTOR and IGF-1R inhibition: phase I trial of everolimus and figitumumab in patients with advanced sarcomas and other solid tumors |

Figitumumab (20 mg/kg IV every 21 days) with full-dose everolimus (10 mg orally once daily) | 21 | 21 (100) | G1 11 (52.4) G2 7 (33.3) |

G3 3 (14.3) |

| Safra et al82 | 2018 | Everolimus plus letrozole for treatment of patients with HR+, HER2–advanced breast cancer progressing on endocrine therapy: an open-label, phase II trial | Everolimus 10 mg daily and letrozole 2.5 mg daily | 72 | 39 (54.2) | 18 (45.9) | G3 21 (8.3) |

| Salazar et al83 | 2017 | Phase II study of BEZ235 versus everolimus in patients with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor-naïve advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors |

Everolimus 10 mg once daily | 31 | 20 (64.5) | 18 (58) | 2 (6.5) |

| Sarkaria et al84 | 2011 | NCCTG phase I trial N057K of everolimus (RAD001) and temozolomide in combination with radiation therapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme patients | All patients received weekly oral RAD001 in combination with standard chemoradiotherapy, followed by RAD001 in combination with standard adjuvant temozolomide | 18 | 11 (61.1) | G2 11 (61.1) | |

| Strickler et al85 | 2012 | Phase I study of bevacizumab, everolimus, and panobinostat (LBH-589) in advanced solid tumors | 10 mg panobinostat three times weekly, 5 or 10 mg everolimus daily, and bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks | 12 | 4 (33) | 3 (25) | 1 (8) |

| Sun et al86 | 2013 | A phase 1b study of everolimus plus paclitaxel in patients with small-cell lung cancer |

A: everolimus 2.5 mg 6 B: everolimus 5 mg 11 C: everolimus 10 mg 3 |

20 | 8 (40) | A 2 10) B 5 (25) C 1 (5) |

|

| Takahashi et al87 | 2013 | Efficacy and safety of concentration-controlled everolimus with reduced-dose cyclosporine in Japanese de novo renal transplant patients: 12-month results | Everolimus 1.5 mg/day starting dose (target trough 3–8 ng/mL) + reduced-dose cyclosporine | 61 | 14 (23) | ||

| Tobinai et al88 | 2010 | Phase I study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma everolimus 5 or 10 mg orally once daily |

Not reported | 13 | 7 (53.7) | G1 3 (23.7) G2 4 (30.7) |

|

| Vlahovic et al89 | 2012 | A phase I study of bevacizumab, everolimus and panitumumab in advanced solid tumors | Everolimus and flat dosing of panitumumab at 4.8 mg/kg and bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks | 32 | 24 (76) | 20 (63) | 4 (13) |

| Wang et al90 | 2014 | Everolimus for patients with mantle cell lymphoma refractory to or intolerant of bortezomib: multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study | Not reported | 58 | 12 (20.7) | 11 (19) | G3 1 (1.7) |

| Werner et al91 | 2013 | Phase I study of everolimus and mitomycin C for patients with metastatic esophagogastric adenocarcinoma | Oral everolimus (5, 7.5, and 10 mg/day) in combination with intravenous MMC 5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. | 16 | 9 (56.25) | G1 8 (50) | G3 1 (6.25) |

| Wolpin et al92 | 2009 | Oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer | Everolimus 10 mg daily | 33 | 10 (30) | G1 8 (24) G2 1 (3) |

G3 1 (3) |

| Yao et al93 | 2008 | Efficacy of everolimus and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrinetumors: results of a phase II study

|

RAD001 5 mg/day or 10 mg/day and octreotide LAR 30 mg every 28 days | 64 | Aphtous ulcers 5 (8) Dysgeusia 1 (2) |

||

| Yao et al94 | 2011 | Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | 10 mg once daily | 204 | 131 (64) | 117 (57) | 14 (7) |

| Yee et al95 | 2006 | Phase I/II study of everolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies | Not reported | 27 | 10 (37) | 10 (37) | |

| Total over all | 8,201 | 3,490 (42.55) | |||||

| Total with grade | 7,796 | 3,347 (42.93) | 2,839 (36.41) | 508 (6.51) | |||

Discussion

Targeted therapy includes those drugs that selectively inhibit a target that is mutated in malignant tissue, aiming to achieve preferential localization in the region of disease and thus an increase in local concentration. In particular, mTOR inhibitors work as signal-transduction inhibitors. Rapamycin, also named sirolimus, was the first mTOR inhibitor approved. It is an antiungal agent produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus with immunosuppressive properties.11 However, sirolimus has been show to have poor pharmacokinetic characteristics, and research has focused on the synthesis of analogues of rapamycin more suitable to therapy, such as everolimus, temsirolimus, and ridaforolimus. These molecules differ from sirolimus in their C-40-O positions, resulting in disparate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles.12 This class of drugs is typically used for the treatment of solid tumors, such as renal-cell carcinoma, breast cancer, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and tuberous sclerosis complex.13–17

Unlike results obtained from reviews about mucositis caused by conventional chemotherapy, in which mucositis is often severe and the most debilitating effect for patients,18 our analysis showed that the incidence of stomatitis of grade 1 or 2 is higher than that of grade 3 or 4. These results are consistent with our previous work.19 However, it must be taken into account that it is not possible to say if side effects are entirely due to everolimus therapy or combination with other drugs. Moreover, not all the papers included in this review specified the exact therapeutic regimen. mIAS generally sets in within a few weeks of initiating everolimus therapy. Grade 3 or 4 lesions may lead to dose interruption or reduction. Interfering with patientfood intake and diminishing quality of life, this kind of toxicity may cause treatment discontinuation or interruption.20

mIAS is often evaluated using common scales employed in the evaluation of conventional oral mucositis (OMAS, 1999; NCI-CTCAE 2006, 2010). However, its clinical appearance tends to differ from conventional mucositis. A more specific mIAS scale was set by Boers-Doets and Lalla. According to this scale, lesions are evaluated depending on their duration, eg, a grade 3 lesion is an ulceration lasting >7 days.21 Management of mIAS is still widely based on education of patients on oral hygiene measures, diet modifications, and pain management.9,22 Treatments used are often based on “magic” mouthwash, composed of lidocaine gel 2% × 30 g, doxycycline suspension 50 mg/5mL × 60 mL, and sucralfate oral suspension 1,000 mg/5 mL dissolved in sodium chloride 0.9% × 2,000 mL used for 3–15 days,23 a sodium bicarbonate–based mouthwash combined with oral fluconazole,24 or a combination of dexamethasone solution 0.5 mg/mL and miconazole 2% gel.25 Another treatment is based on a combination of topical anesthetics, a magic mouthwash (composed of lidocaine, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide, dimethicone suspension, diphenhydramine, equal parts) clobetasol gel 0.05%, dexamethasone 0.1 mg/mL, triamcinolone paste, intralesional triamcinolone, and systemic prednisone (1 mg/kg for 7 days). Management of mIAS nowadays is based on education of patients on oral hygiene measures, diet modifications, and pain management.9 Rugo et al showed evidence of the efficacy of a prophylactic use of dexamethasone mouthwash in patients treated with everolimus plus exemestane for advanced or metastatic breast cancer.26 The mouthwash was administered in combination with a prophylactic topical antifungal agent to prevent potential fungal infection.26 It still cannot be determined which lesions will self-limit and which will reduce quality of life, leading to malnutrition and dose reduction in medically necessary treatment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

References

- 1.Gomez-Pinillos A, Ferrari AC. mTOR signaling pathway and mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26(3):483–505, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keefe DM, Bateman EH. Tumor control versus adverse events with targeted anticancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;9(2):98–109. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khokhar NZ, Altman JK, Platanias LC. Emerging roles for mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in the treatment of solid tumors and hematological malignancies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23(6):578–586. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834b892d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabney R, Devine R, Sein N, George B. New agents in renal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2014;9(3):183–193. doi: 10.1007/s11523-013-0303-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan R, Kay A, Berg WJ, Lebwohl D. Targeting tumorigenesis: development and use of mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng LH, Zheng XF. Toward rapamycin analog (rapalog)-based precision cancer therapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(10):1163–1169. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martins F, de Oliveira MA, Wang Q, et al. A review of oral toxicity associated with mTOR inhibitor therapy in cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(4):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonis S, Treister N, Chawla S, Demetri G, Haluska F. Preliminary characterization of oral lesions associated with inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin in cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116(1):210–215. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boers-Doets CB, Raber-Durlacher JE, Treister NS, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor-associated stomatitis. Future Oncol. 2013;9(12):1883–1892. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson DE, O’Shaughnessy JA, Rugo HS, et al. Oral mucosal injury caused by mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors: emerging perspectives on pathobiology and impact on clinical practice. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):1897–1907. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2016.5.issue-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal SN, Baker H, Rapamycin VC. (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1975;28(10):727–732. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q, Thoreen C, Wang J, Sabatini D, Gray NS. mTOR mediated anti-cancer drug discovery. Drug Discov Today Ther Strateg. 2009;6(2):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ddstr.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awada A, Cardoso F, Fontaine C, et al. The oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in combination with letrozole in patients with advanced breast cancer: results of a phase I study with pharmacokinetics. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boers-Sonderen MJ, de Geus-Oei LF, Desar IM, et al. Temsirolimus and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) combination therapy in breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer: phase Ib results and prediction of clinical outcome with FDG-PET/CT. Target Oncol. 2014;9(4):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s11523-014-0309-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudes GR, Berkenblit A, Feingold J, Atkins MB, Rini BI, Dutcher J. Clinical trial experience with temsirolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(Suppl 3):S26–S36. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borbasi S, Cameron K, Quested B, Olver I, To B, Evans D. More than a sore mouth: patients’ experience of oral mucositis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(7):1051–1057. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.1051-1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo Muzio L, Arena C, Troiano G, Villa A. Oral stomatitis and mTOR inhibitors: a review of current evidence in 20,915 patients. Oral Dis. 2018;24(1–2):144–171. doi: 10.1111/odi.12795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rugo HS, Pritchard KI, Gnant M, et al. Incidence and time course of everolimus-related adverse events in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer: insights from BOLERO-2. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(4):808–815. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boers-Doets C, Lalla RV. The mIAS scale: a scale to measure mTOR inhibitor-associated stomatitis. Supp Care Cancer. 2013;21(Suppl):1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji YD, Aboalela A, Villa A. Everolimus-associated stomatitis in a patient who had renal transplant. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalogirou EM, Tosios KI, Piperi EP, Sklavounou A. mTOR inhibitor-associated stomatitis (mIAS) in three patients with cancer treated with everolimus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(1):e13–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferte C, Soria JC, Penel N. Dose-levels and first signs of efficacy in contemporary oncology phase 1 clinical trials. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e16633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolatou-Galitis O, Nikolaidi A, Athanassiadis I, Papadopoulou E, Sonis S. Oral ulcers in patients with advanced breast cancer receiving everolimus: a case series report on clinical presentation and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116(2):e110–e116. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rugo HS, Seneviratne L, Beck JT, et al.Prevention of everolimus-related stomatitis in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer using dexamethasone mouthwash (SWISH): a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;(18):654–662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30109-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amato RJ, Jac J, Giessinger S, Saxena S, Willis JP. A phase 2 study with a daily regimen of the oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2438–2446. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v115:11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andre F, O’Regan R, Ozguroglu M, et al. Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):580–591. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70138-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angelousi A, Kamp K, Kaltsatou M, O’Toole D, Kaltsas G, de Herder W. Sequential everolimus and sunitinib treatment in pancreatic metastatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours resistant to prior treatments. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(4):394–402. doi: 10.1159/000456035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong AJ, Halabi S, Eisen T, et al. Everolimus versus sunitinib for patients with metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ASPEN): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(3):378–388. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00515-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bajetta E, Catena L, Fazio N, et al. Everolimus in combination with octreotide long-acting repeatable in a first-line setting for patients with neuroendocrine tumors: an ITMO group study. Cancer. 2014;120(16):2457–2463. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, et al. Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(16):2630–2637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergmann L, Kube U, Doehn C, et al. Everolimus in metastatic renal cell carcinoma after failure of initial anti-VEGF therapy: final results of a noninterventional study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:303. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1309-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besse B, Leighl N, Bennouna J, et al. Phase II study of everolimus-erlotinib in previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(2):409–415. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campone M, Levy V, Bourbouloux E, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(2):315–321. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castellano D, Bajetta E, Panneerselvam A, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable in patients with colorectal neuroendocrine tumors: a subgroup analysis of the phase III RADIANT-2 study. Oncologist. 2013;18(1):46–53. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan JA, Blaszkowsky L, Stuart K, et al. A prospective, phase 1/2 study of everolimus and temozolomide in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Cancer. 2013;119(17):3212–3218. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1814–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow H, Ghosh PM, deVere White R, et al. A phase 2 clinical trial of everolimus plus bicalutamide for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(12):1897–1904. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung V, Frankel P, Lim D, et al. Phase Ib trial of mFOLFOX6 and everolimus (NSC-733504) in patients with metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Oncology. 2016;90(6):307–312. doi: 10.1159/000445297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciruelos E, Vidal M, Martinez de Duenas E, et al. Safety of everolimus plus exemestane in patients with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: results of phase IIIb BALLET trial in Spain. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciunci CA, Perini RF, Avadhani AN, et al. Phase 1 and pharmacodynamic trial of everolimus in combination with cetuximab in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(1):77–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colon-Otero G, Weroha SJ, Foster NR, et al. Phase 2 trial of everolimus and letrozole in relapsed estrogen receptor-positive high-grade ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(1):64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Courtney KD, Manola JB, Elfiky AA, et al. A phase I study of everolimus and docetaxel in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deenen MJ, Klumpen HJ, Richel DJ, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of capecitabine and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30(4):1557–1565. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9723-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doi T, Muro K, Boku N, et al. Multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with previously treated metastatic gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1904–1910. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Madani M, Colomban O, Tod M, et al. EVESOR, a model-based, multiparameter, Phase I trial to optimize the benefit/toxicity ratio of everolimus and sorafenib. Future Oncol. 2017;13(8):679–693. doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Escudier B, Molinie V, Bracarda S, et al. Open-label phase 2 trial of first-line everolimus monotherapy in patients with papillary metastatic renal cell carcinoma: RAPTOR final analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fazio N, Granberg D, Grossman A, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable in patients with advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors: analysis of the phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled RADIANT-2 study. Chest. 2013;143(4):955–962. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferolla P, Brizzi MP, Meyer T, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting pasireotide or everolimus alone or in combination in patients with advanced carcinoids of the lung and thymus (LUNA): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):1652–1664. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30681-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finn RS, Poon RT, Yau T, et al. Phase I study investigating everolimus combined with sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2013;59(6):1271–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fury MG, Sherman E, Haque S, et al. A phase I study of daily everolimus plus low-dose weekly cisplatin for patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69(3):591–598. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1734-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghobrial IM, Gertz M, Laplant B, et al. Phase II trial of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in relapsed or refractory Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(8):1408–1414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldberg HJ, Harari S, Cottin V, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a phase II study. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(3):783–794. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00210714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gong C, Zhao Y, Wang B, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus in Chinese metastatic HR positive, HER2 negative breast cancer patients: a real-world retrospective study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):59810–59822. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.v8i35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grignani G, Palmerini E, Ferraresi V, et al. Sorafenib and everolimus for patients with unresectable high-grade osteosarcoma progressing after standard treatment: a non-randomised phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):98–107. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71136-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Burris HA 3rd, Waterhouse D, Clark BL, Whorf R. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2131–2136. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hatano T, Chikaraishi K, Inaba H, Endo K, Egawa S. Outcomes of everolimus treatment for renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: A single institution experience in Japan. Int J Urol. 2016;23(10):833–838. doi: 10.1111/iju.2016.23.issue-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hatano T, Atsuta M, Inaba H, Endo K, Egawa S. Effect of everolimus treatment for renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: an evaluation based on tumor density. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hurvitz SA, Dalenc F, Campone M, et al. A phase 2 study of everolimus combined with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in patients with HER2-overexpressing advanced breast cancer that progressed during prior trastuzumab and taxane therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(3):437–446. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2689-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jerusalem G, Mariani G, Ciruelos EM, et al. Safety of everolimus plus exemestane in patients with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer progressing on prior non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors: primary results of a phase IIIb, open-label, single-arm, expanded-access multicenter trial (BALLET). Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1719–1725. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jovanovic B, Mayer IA, Mayer EL, et al. A randomized Phase II neoadjuvant study of cisplatin, paclitaxel with or without everolimus in patients with stage II/III Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC): responses and long-term outcome correlated with increased frequency of DNA damage response gene mutations, TNBC subtype, AR status, and Ki67. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(15):4035–4045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jozwiak S, Kotulska K, Berkowitz N, Brechenmacher T, Franz DN. Safety of everolimus in patients younger than 3 years of age: results from EXIST-1, a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2016;172:151–155 e151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kato R, Obara W, Matsuura T, Kato Y, Iwasaki K, Fujioka T. Efficacy of everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to VEGFR-TKIs and safety compared with prior VEGFR-TKI treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(5):479–485. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim DW, Oh DY, Shin SH, et al. A multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with progressive unresectable adenoid cystic carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:795. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim JH, Lee W, Kim TN, Nam JK, Kim TH, Lee KS. Clinical outcomes of the sequential use of pazopanib followed by everolimus for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A multicentre study in Korea. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018;12(1):E15–E20. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koutsoukos K, Bamias A, Tzannis K, et al. Real-world experience of everolimus as second-line treatment in metastatic renal cell cancer after failure of pazopanib. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:4885–4893. doi: 10.2147/OTT [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kulke MH, Ruszniewski P, Van Cutsem E, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of everolimus in combination with pasireotide LAR or everolimus alone in advanced, well-differentiated, progressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: COOPERATE-2 trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(6):1309–1315. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumano M, Miyake H, Harada K, Fujisawa M. Sequential use of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma following failure of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Med Oncol. 2013;30(4):745. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0745-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moscetti L, Vici P, Gamucci T, et al. Safety analysis, association with response and previous treatments of everolimus and exemestane in 181 metastatic breast cancer patients: a multicenter Italian experience. Breast. 2016;29:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Motzer RJ, Alyasova A, Ye D, et al. Phase II trial of second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RECORD-4). Ann Oncol. 2016;27(3):441–448. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Motzer RJ, Barrios CH, Kim TM, et al. Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line everolimus and second-line sunitinib versus first-line sunitinib and second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(25):2765–2772. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.6911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Glen H, et al. Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(15):1473–1482. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00290-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oh DY, Kim TW, Park YS, et al. Phase 2 study of everolimus monotherapy in patients with nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors or pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6162–6170. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ohtsu A, Ajani JA, Bai YX, et al. Everolimus for previously treated advanced gastric cancer: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III GRANITE-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3935–3943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohyama K, Matsumoto Y, Amamizu H, et al. Association of coronary perivascular adipose tissue inflammation and drug-eluting stent-induced coronary hyperconstricting responses in pigs: (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(9):1757–1764. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Panzuto F, Rinzivillo M, Fazio N, et al. Real-world study of everolimus in advanced progressive neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2014;19(9):966–974. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park K, Lee JL, Ahn JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus in korean patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma following treatment failure with a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46(4):339–347. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pavel M, Unger N, Borbath I, et al. Safety and QOL in patients with advanced NET in a Phase 3b expanded access study of everolimus. Target Oncol. 2016;11(5):667–675. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0440-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quek R, Wang Q, Morgan JA, et al. Combination mTOR and IGF-1R inhibition: phase I trial of everolimus and figitumumab in patients with advanced sarcomas and other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(4):871–879. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Safra T, Kaufman B, Kadouri L, et al. Everolimus plus letrozole for treatment of patients with HR(+), HER2(-) advanced breast cancer progressing on endocrine therapy: an open-label, Phase II trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Salazar R, Garcia-Carbonero R, Libutti SK, et al. Phase II study of BEZ235 versus Everolimus in patients with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor-naive advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sarkaria JN, Galanis E, Wu W, et al. North Central Cancer Treatment Group Phase I trial N057K of everolimus (RAD001) and temozolomide in combination with radiation therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(2):468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strickler JH, Starodub AN, Jia J, et al. Phase I study of bevacizumab, everolimus, and panobinostat (LBH-589) in advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70(2):251–258. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1911-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun JM, Kim JR, Do IG, et al. A phase-1b study of everolimus plus paclitaxel in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1482–1487. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takahashi K, Uchida K, Yoshimura N, et al. Efficacy and safety of concentration-controlled everolimus with reduced-dose cyclosporine in Japanese de novo renal transplant patients: 12-month results. Transplant Res. 2013;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2047-1440-2-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tobinai K, Ogura M, Maruyama D, et al. Phase I study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2010;92(4):563–570. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0707-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vlahovic G, Meadows KL, Uronis HE, et al. A phase I study of bevacizumab, everolimus and panitumumab in advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70(1):95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1889-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang M, Popplewell LL, Collins RH Jr., et al. Everolimus for patients with mantle cell lymphoma refractory to or intolerant of bortezomib: multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(4):510–518. doi: 10.1111/bjh.2014.165.issue-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Werner D, Atmaca A, Pauligk C, Pustowka A, Jager E, Al-Batran SE. Phase I study of everolimus and mitomycin C for patients with metastatic esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2013;2(3):325–333. doi: 10.1002/cam4.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wolpin BM, Hezel AF, Abrams T, et al. Oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(2):193–198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, et al. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4311–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yee KW, Zeng Z, Konopleva M, et al. Phase I/II study of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(17):5165–5173. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]