Abstract

The invasion of mammalian cytoplasm by microbial DNA from infectious pathogens or by self DNA from the nucleus or mitochondria represents a danger signal that alerts the host immune system1. Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase is a sensor of cytoplasmic DNA that activates the type-I interferon pathway2. Upon binding to DNA, cyclic GMP–AMP synthase is activated to catalyse the synthesis of cyclic GMP–AMP (cGAMP) from GTP and ATP3. cGAMP functions as a second messenger that binds to and activates stimulator of interferon genes (STING)3–9. STING then recruits and activates tank-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which phosphorylates STING and the transcription factor IRF3 to induce type-I interferons and other cytokines10,11. However, how cGAMP-bound STING activates TBK1 and IRF3 is not understood. Here we present the cryo-electron microscopy structure of human TBK1 in complex with cGAMP-bound, full-length chicken STING. The structure reveals that the C-terminal tail of STING adopts a β-strand-like conformation and inserts into a groove between the kinase domain of one TBK1 subunit and the scaffold and dimerization domain of the second subunit in the TBK1 dimer. In this binding mode, the phosphorylation site Ser366 in the STING tail cannot reach the kinase-domain active site of bound TBK1, which suggests that STING phosphorylation by TBK1 requires the oligomerization of both proteins. Mutational analyses validate the interaction mode between TBK1 and STING and support a model in which high-order oligomerization of STING and TBK1, induced by cGAMP, leads to STING phosphorylation by TBK1.

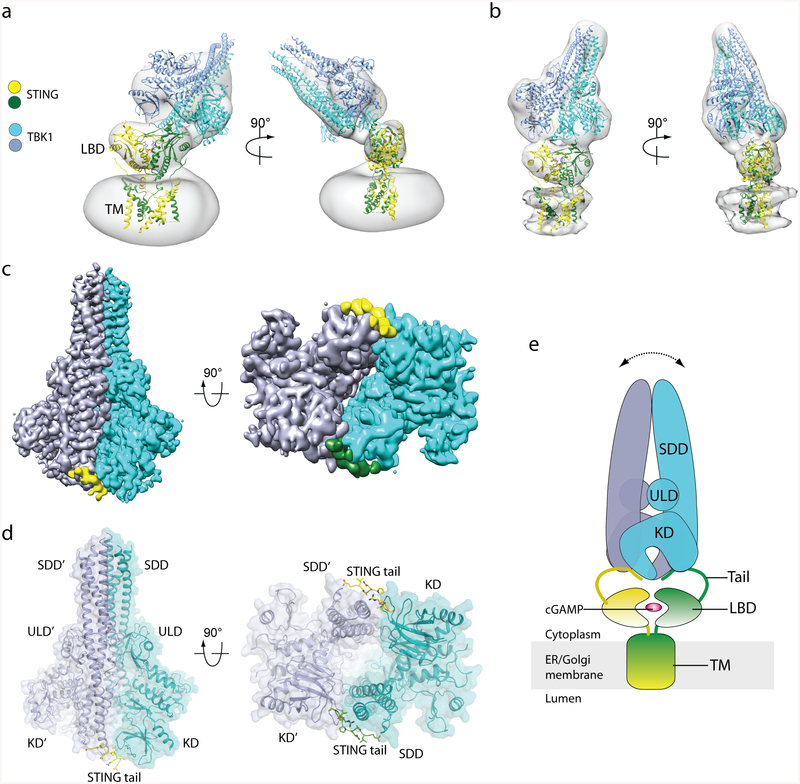

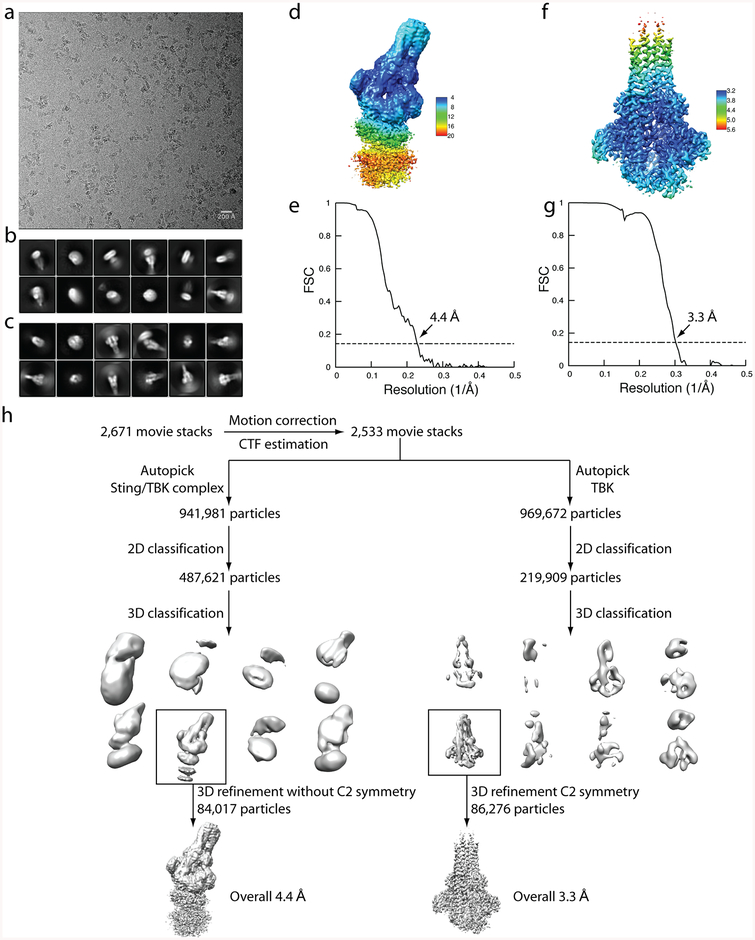

To understand how STING recruits TBK1, we reconstituted a complex between human TBK1 and chicken STING for cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) analysis (Extended Data Fig. 1, Supplementary Information). The STING–TBK1 complex could clearly be identified in the 2D class averages, although the relative orientation between STING and TBK1 was highly variable, which suggests that the binding between the two proteins is flexible (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). The reconstruction of the complex from one of the 3D classes reached an overall resolution of 4.4 Å, with secondary structures of TBK1 resolved (Extended Data Fig. 2d, e, h). Local resolution of the density for STING is lower, although the overall shape fits well with the structure of full-length STING (described in the accompanying paper12). The results of 3D classification demonstrate that the relative orientation between the two proteins also varies substantially (Fig. 1a, b). Despite this variability, in general the TBK1 dimer engages STING from the top of the cytosolic ligand-binding domain dimer, whereas the transmembrane domain of STING is apparently not involved in the interaction with TBK1.

Fig. 1 |. Structure of the complex of chicken STING and human TBK1.

a, b, Three-dimensional reconstructions of two 3D classes of the complex. The atomic models of dimeric full-length chicken STING bound to cGAMP (from ref.12) and the human TBK1 dimer (RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 4IM0) were fit into the maps (grey) through rigid-body docking. The extra density that surrounds the transmembrane (TM) domain of STING in a is from the detergent micelle. The protein density in b is stronger and therefore shown at a higher threshold, which led to partial cut-off of the detergent micelle density. LBD, ligand-binding domain. c, High-resolution 3D reconstruction from focused refinement on TBK1 with C2 symmetry. The densities for the two protomers of the TBK1 dimer are coloured either cyan or blue. The densities for the two STING tails are coloured either yellow or green. d, Atomic model of TBK1 bound to the C-terminal tail of STING. The colour scheme is the same as that of the atomic models in a. KD, kinase domain; ULD, ubiquitin-like domain. e, Cartoon model of the STING–TBK1 complex. The double-headed arrow indicates the wobble between TBK1 and STING, owing to flexibility in the STING tail. ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

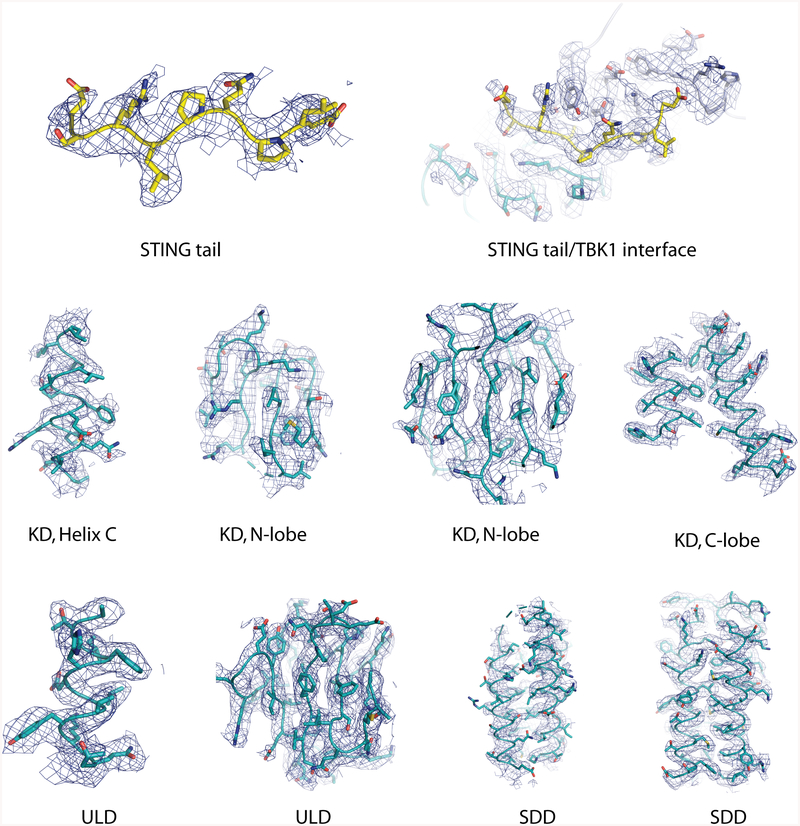

We then carried out focused refinement for TBK1, which led to a substantially improved reconstruction with an overall resolution of 3.3 Å (ref.13) (Extended Data Fig. 2c, f–h). The side chains are clearly resolved for the majority of the residues in TBK1 (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 3). The kinase domain, a ubiquitin-like domain, and the scaffold and dimerization domain (SDD) together form the elongated dimer of TBK1, which is very similar to previously reported14–16 crystal structures of TBK1 (root mean square deviation < 1 Å) (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 4). The kinase domain, which adopts the typical bilobed kinase fold, uses its N-terminal lobe to interact with the SDD from the dimer partner. At this junction between the kinase domain and the SDD, a prominent segment of density is present in the cryo-EM map, which is not accounted for by residues from TBK1 (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 3). The high quality of the density allowed us to assign it, on the basis of the shape and size of side chains, to a segment (residues 369–377; corresponding to the same residue numbers in human STING) of the C-terminal tail of chicken STING (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 3). We therefore define this segment as the TBK1-binding motif (TBM). A complete model of the STING–TBK1 complex, based on the structures of the TBK1–STING–TBM complex as well as full-length STING, suggests that the TBK1 dimer is tethered to the two C-terminal TBMs from the STING dimer, whereas the ligand-binding domain of STING makes little or no contact with TBK1 (Fig. 1e). The approximately 20-residue linker between the TBM and the final helix in the ligand-binding domain of STING is disordered in both the crystal structures and the cryo-EM maps of STING, which explains the flexibility between STING and TBK1.

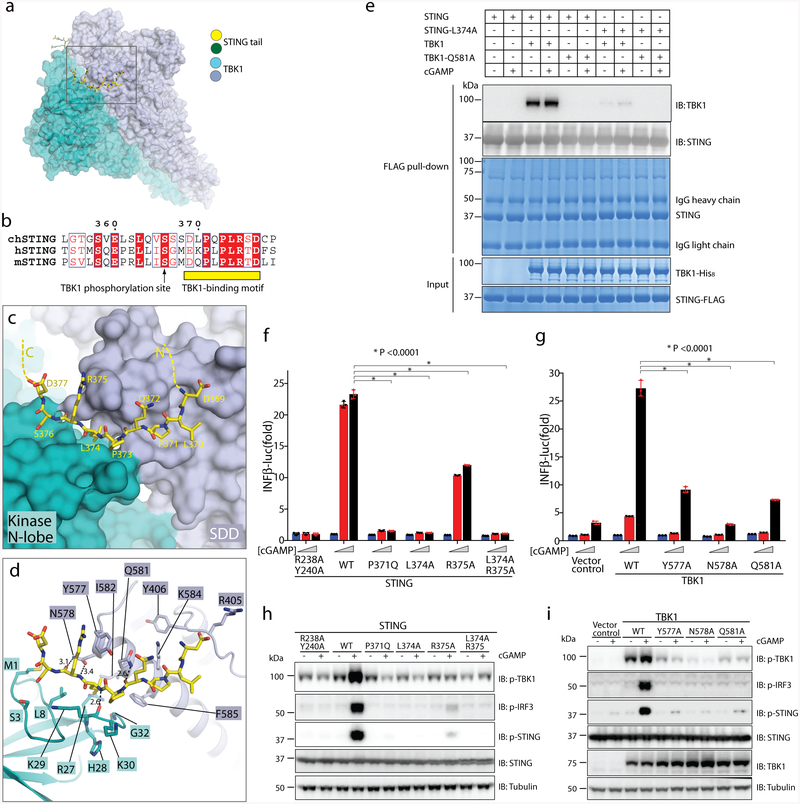

The TBM in STING adopts an extended conformation that is similar to a β-strand, and makes numerous interactions with TBK1 (Fig. 2a–c, Supplementary Video 1). Residues 373–376 in the binding motif are wedged into a groove between the kinase domain from one subunit and the SDD from the second subunit in the same TBK1 dimer. One side of the groove is formed by the N-terminal extension (residues 1–12) and the loop that connects strands β2 and β3 (residues 28–33) in the kinase domain of TBK1; the other side of the groove is lined by the N-terminal end of the third helix in the SDD (residues 577–585) (Fig. 2d). The side chain of Leu374 in STING sticks into a deep hydrophobic pocket in the middle of the groove. The hydrophobic pocket is formed by Ile582 and Phe585 from the SDD, and Leu8, Arg27 and Gly32 from the kinase domain. This interaction probably makes a major contribution to the binding affinity between STING and TBK1. The two proline residues in the TBM of STING, Pro371 and Pro373, also make hydrophobic interactions with TBK1, by packing with Phe585 in the SDD and Lys30 in the kinase domain, respectively. Arg375 in the STING TBM forms a cation–π interaction with Tyr577 in the SDD. Asp377 in the TBM is located close to Arg375 and may stabilize the side chain conformation of Arg375. At the other end of the TBM, Asp369 is likely to contribute to the binding by forming electrostatic interactions with Arg405 from the SDD. In addition, the backbone of STING TBM forms several hydrogen bonds with residues in the groove in TBK1, including the side chains of Asn578 and Gln581 in the SDD and the carbonyl oxygen of Lys29 in the kinase domain (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2 |. Binding interface between human TBK1 and the chicken STING C-terminal tail.

a, Overview of the binding interface. The rectangle denotes the region shown in detail in c and d. b, Sequence alignment of the C-terminal tail of STING from chicken, human and mouse (denote by ch-, h- and m-prefixes, respectively). c, d, Detailed views of the binding interface. Potential hydrogen bonds are indicated with dotted lines. Numbers are inter-atom distances. N-lobe, N-terminal lobe. e, Mutants of interface residues in either STING or TBK1 abolish the STING/TBK1 interaction in vitro. Data are representative of two independent biological experiments. f, Mutants of interface residues in human STING abolish cGAMP-stimulated IFNβ expression. HEK293T cells that stably express IFNβ–luciferase (IFNβ–luc) were transfected with the STING–Flag wild type (WT) or mutants. The R238A/Y240A mutant (which does not bind cGAMP) served as a negative control. Cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of cGAMP (0, 0.3 and 1.4 μM). Data are mean ± s.d. n = 3. g, Mutants of interface residues in human TBK1 abolish cGAMP-stimulated IFNβ expression. HEK293T TBK1-null cells that stably express human STING–Flag were reconstituted with the TBK1 wild type or mutants, using lentiviral infection. Cells were transiently transfected with the IFNβ–luciferase reporter and stimulated with increasing concentrations of cGAMP (0, 0.3 and 1.4 μM). Luciferase activity was determined 24 h after transfection. Data are mean ± s.d. h, i, Mutants of interface residues in either STING (h) or TBK1 (i) abolish cGAMP-stimulated phosphorylation (p) of TBK1, STING and IRF3. Cells used in h and i are similar to those in f and g, respectively, except the cells in h and i do not have the IFNβ–luciferase reporter. Cells were treated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 3 h, and subjected to immunoblotting analyses. Data in f–i are representative of three independent biological replicates.

The residues in the TBM are conserved among STING from different species, and constitute a sequence motif of (D/E)XPXPLR(S/T)D (in which “/” and “X” denote “or” and “any amino acid”, respectively) (Fig. 2b). The side chains of the two non-conserved residues, Leu370 and Gln372 in chicken STING, point away from TBK1 and do not contribute to the binding interface. Residues that form the STING-binding groove in TBK1 are identical between human and chicken TBK1 (Extended Data Fig. 5).

We used a pull-down assay with purified STING and TBK1 proteins to verify the binding mode seen in the structure. The results showed that both the L374A mutant of human STING and the Q581A mutant of human TBK1 abolished the STING–TBK1 interaction in vitro, which appeared to be largely independent of cGAMP (Fig. 2e). Further interface mutants of human STING (P371Q, L374A, R375A and L374A/R375A) were tested in a cell-based functional assay (Fig. 2f). cGAMP treatment led to robust expression of IFNβ in the cells that express wild-type STING, but not in cells that expressed each of the mutants (Fig. 2f). Consistently, cGAMP-induced phosphorylation of TBK1, STING and IRF3 in these cells was abrogated by the interface mutants of STING (Fig. 2h). We also tested substitutions of interface residues in TBK1 (Y577A, N578A and Q581A) with a similar assay. Cells that express each of the interface mutants of TBK1 showed lower levels of cGAMP-induced expression of IFNβ, as compared with cells that express the wild-type protein (Fig. 2g). Similarly, cGAMP-induced phosphorylation of TBK1, STING and IRF3 was reduced by the interface mutations in TBK1 (Fig. 2i). These results demonstrate that the interface residues on both STING and TBK1 are essential for their signalling functions.

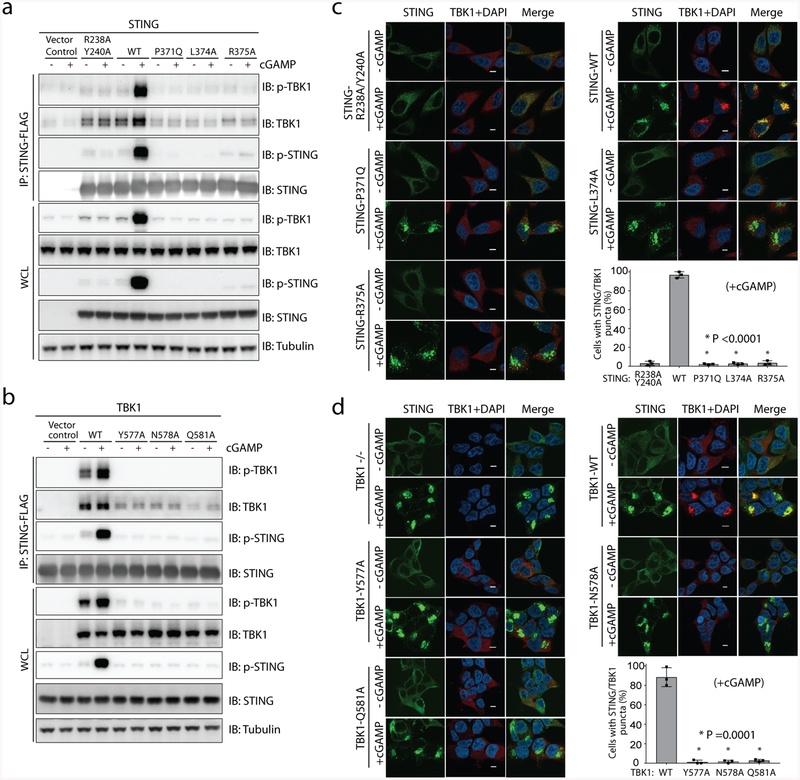

We next examined the binding between STING and TBK1 by co-immunoprecipitation from cells. The results showed that there is a constitutive interaction between STING and TBK1 in the absence of cGAMP (Fig. 3a, b). Indeed, even the STING(R238A/Y240A) mutant that is incapable of binding to cGAMP could bind TBK1. cGAMP stimulation led to phosphorylation of TBK1 and STING, and also enhanced the binding between TBK1 and STING (Fig. 3a, b). The interface mutants of either STING or TBK1 diminished the binding between the two proteins. To examine the binding in intact cells, we performed immunostaining of transiently expressed STING in HeLa cells that are deficient in cyclic GMP–AMP synthase. As has previously been shown6, cGAMP stimulates puncta formation of STING at the perinuclear region, which indicates oligomerization of STING and its translocation from the endoplasmic reticulum to a perinuclear compartment (Fig. 3c). TBK1 colocalized with these STING puncta, presumably through cGAMP-induced interaction with STING. As expected, STING puncta were not affected by the interface mutants of STING (Fig. 3c). However, the recruitment of TBK1 to STING puncta was not observed in cells that express the interface mutants of STING. We also tested interface mutants of TBK1 by co-expressing them with STING in HEK293T TBK1-null cells. Co-localization with STING puncta was detected with the TBK1 wild type, but not with the mutants (Fig. 3d). These results further verify the binding interface between STING and TBK1, as seen in our structure. Notably, the results here show that the interaction between STING and TBK1 is enhanced by cGAMP, in contrast to our in vitro binding assays that showed that this interaction is independent of cGAMP (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 1a). This discrepancy suggests that cGAMP regulates the STING–TBK1 interaction in cells through an indirect mechanism.

Fig. 3 |. The interface between TBK1 and the STING C-terminal tail is required for TBK1 binding and colocalization with STING in cells.

a, b, Mutations of interface residues in either STING (a) or TBK1 (b) abolish cGAMP-induced interaction between STING and TBK1, as well as the phosphorylation of both proteins, as shown by immunoblotting. Cells used in a, b are the same as those used in Fig. 2h, i, respectively. After cGAMP stimulation, immunoprecipitation was carried out to examine the interaction between STING and TBK1. Data are representative of three independent biological replicates. WCL, whole-cell lysate. c, Mutants of interface residues in STING diminish colocalization of TBK1 with cGAMP-induced puncta of STING in cells. HeLa cells deficient in cyclic GMP–AMP synthase and expressing the wild type or mutant constructs of STING were stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h, and then subjected to immunostaining for STING (green, 488 nm), TBK1 (red, 568 nm) and DAPI. Representative confocal images of cells with or without cGAMP stimulation are shown. Scale bars, 5 μm. d, Mutants of interface residues in TBK1 diminish colocalization of TBK1 with cGAMP-induced puncta of STING in cells. HEK293T cell lines that stably express wild-type or mutant TBK1 (as in b) were stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h and subjected to immunostaining (as in c). Scale bars, 5 μm. In both c, d, the percentage of cells with STING and TBK1 colocalization was quantified from at least 150 cells for each group. Data are mean ± s.d. and representative of three independent biological replicates.

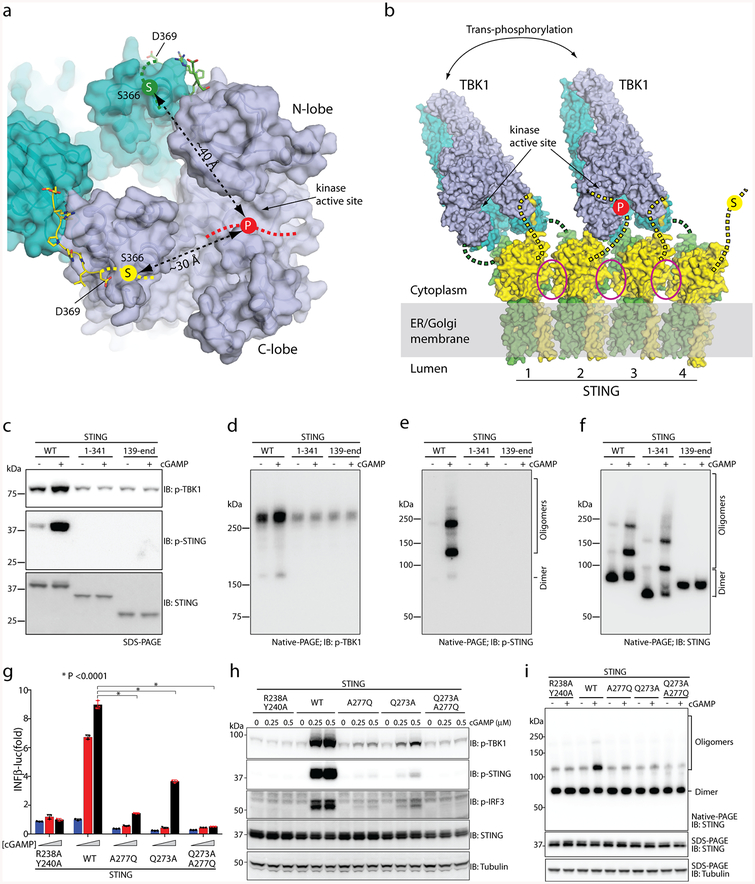

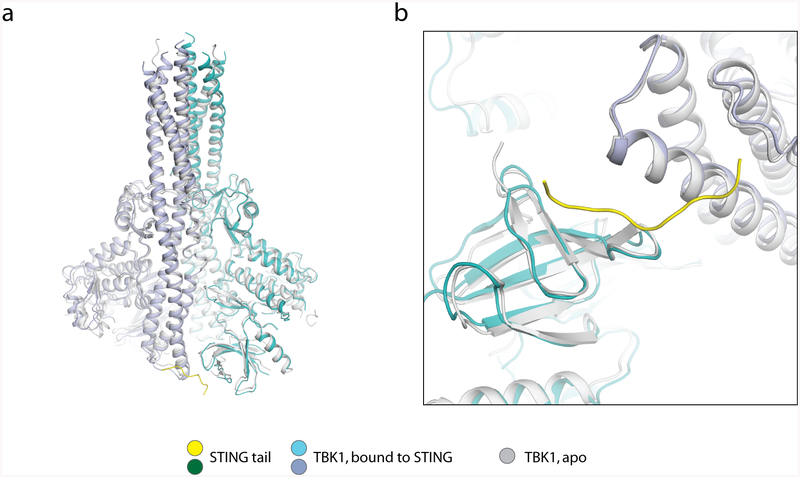

The structure of TBK1 in complex with STING is nearly identical to the apo TBK1 structures, which indicates that STING does not activate TBK1 by inducing a conformational change in the kinase domain. The activity of TBK1 is regulated by the phosphorylation of a serine residue (Ser172) in the activation loop14–16. Owing to geometric constraints, the kinase domain normally cannot phosphorylate the activation loop in cis. In addition, the two kinase domains in the TBK1 dimer face away from one another, and therefore cannot phosphorylate Ser172 for each other. One way to achieve activation of TBK1 is through higher-order oligomerization, which brings multiple TBK1 dimers together for trans-autophosphorylation of the activation loop14. In the accompanying paper12, we find that full-length STING bound to cGAMP forms a side-by-side tetramer that could grow further into larger oligomers. Therefore, the binding of TBK1 to STING oligomers provides a mechanism for inducing clustering and trans-autophosphorylation of TBK1 (Fig. 4b). cGAMP-induced STING oligomerization also provides a model for STING phosphorylation by TBK1. The major phosphorylation site in both human and chicken STING is Ser366 (ref.11) (Fig. 2b), which is not resolved in the cryo-EM map; however, the position of this serine is restrained because it is located only three residues upstream of the TBM (Figs. 2b, 4a). On the basis of our analysis, Ser366 is estimated to be over 30 Å away from the active sites of the two kinase domains in the TBK1 dimer (Fig. 4a). Therefore, the tail of STING that is bound to TBK1 cannot be phosphorylated by the same TBK1 dimer to which it is bound. However, in large oligomers of STING, the TBK1 that is tethered to the two C-terminal tails of one STING dimer can phosphorylate the Ser366 residues of neighbouring STING proteins that are not bound to TBK1 (Fig. 4b). The approximately 20-residue linker between the ligand-binding domain and Ser366 can span over a distance of 60 Å, which is sufficient for Ser366 to reach the active site of TBK1 bound to a neighbouring STING.

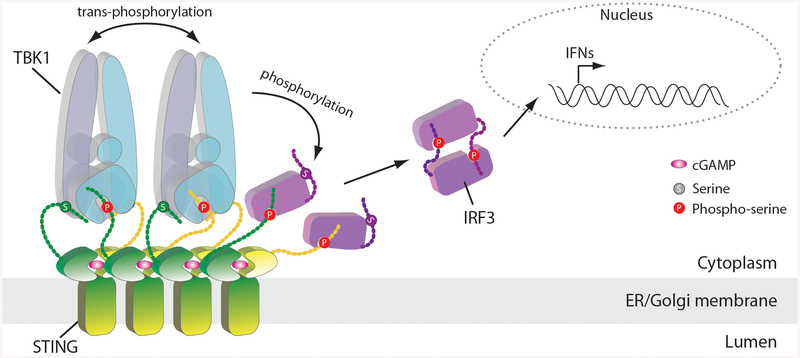

Fig. 4 |. TBK1 activation and STING phosphorylation depend on STING oligomerization.

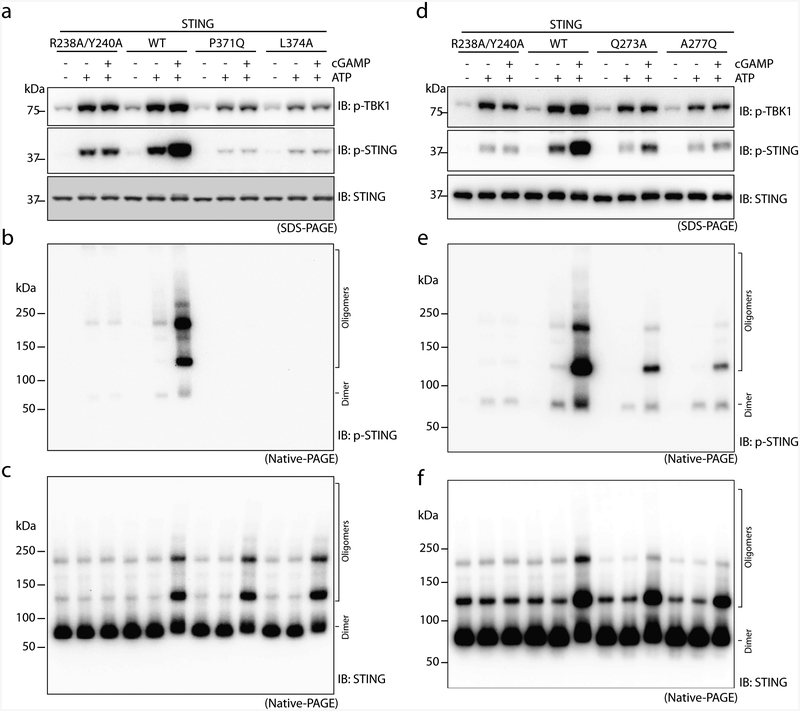

a, The STING C-terminal tail bound to TBK1 cannot reach the kinase active site for phosphorylation of Ser366 (‘S’ in yellow circle). ‘P’ on the red dotted line indicates the location of the TBK1 kinase active site, at which phosphorylation occurs. b, Model of TBK1 activation and STING phosphorylation upon STING oligomerization on the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi membrane. The C-terminal tails in STING dimers 1 and 3 are bound to TBK1, whereas the tails in STING dimers 2 and 4 could enter the active site of TBK1 for phosphorylation. The two TBK1 dimers could activate one another by trans-autophosphorylation. Magenta ovals highlight the oligomer interface mediated by the STING ligand-binding domain, which in human STING involves Gln273 and Ala277. c, Phosphorylation of both TBK1 and STING requires the C-terminal tail and transmembrane region of STING. The S1 post-nuclear supernatant from HEK293T cells that express either the STING wild type or mutants was stimulated with cGAMP in the presence of ATP, resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and subjected to immunoblotting analyses for pTBK1, pSTING and STING. d–f, Effects of the STING truncations on the phosphorylation and oligomerization of TBK1 and STING. The same samples as in c were resolved by native PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting to assess both oligomerization and phosphorylation of STING. g, Effects of mutations in the tetramer interface of human STING on cGAMP-stimulated IFNβ expression. The assays were conducted as in Fig. 2f. Data are mean ± s.d. and representative of three independent biological replicates. h, Effects of STING mutations on phosphorylation of STING, TBK1 and IRF3. HeLa cells that stably express either STING wild type or mutants were stimulated with cGAMP for 2 h and subjected to immunoblot analyses. i, Effects of the mutations in the tetramer interface on cGAMP-induced STING oligomerization. Lysates from cells stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h were resolved by native PAGE or SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. The immunoblotting results are representative of three independent biological replicates.

To test this model of TBK1 activation and STING phosphorylation, we established an in vitro phosphorylation assay in which the post-nuclear S1 fraction of HEK293T cells that contains STING and TBK1 was incubated with ATP and cGAMP. The results showed that cGAMP induced the oligomerization of STING, and phosphorylation of both TBK1 and STING (Fig. 4c–f). As expected, STING(1–341)—which lacks the TBK1-binding tail—formed higher-order oligomers but failed to trigger phosphorylation of TBK1 and STING (Fig. 4c–f). The P371Q and L374A mutants of STING, which cannot bind TBK1, also could not stimulate phosphorylation of TBK1 or STING (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). STING(139–end), which lacks the transmembrane domain, did not oligomerize or induce TBK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 4c–f).

In the accompanying paper12, we identify the ligand-binding domain α2–α3 loops in each STING dimer that form the tetramer interface. Single or double mutants of two of the tetramer interface residues (Q273A, A277Q and Q273A/A277Q) greatly reduced cGAMP-induced phosphorylation of TBK1, STING and IRF3, as well as the induction of IFNβ (Fig. 4g, h). In addition, native gel electrophoresis (native PAGE) revealed that the mutants reduced the formation of higher-order STING oligomers (Fig. 4i). Similar results were also obtained using the in vitro assay in which cGAMP was added to lysates from HEK293T cells that express wild-type STING or the interface mutants (Extended Data Fig. 6d–f). Notably, the higher-order oligomers of STING were phosphorylated more efficiently than the dimer (compare Extended Data Fig. 6e, f). Collectively, these results support a model in which the oligomerization of STING is critical for TBK1 activation and STING phosphorylation.

Our analyses suggest a model in which cGAMP-induced, high-order oligomerization of STING provides a signalling platform for recruiting and activating TBK1 (Extended Data Fig. 7). In the STING oligomer, some of the C-terminal tails recruit TBK1, which phosphorylates the tails from neighbouring STING molecules. The phosphorylated 363LXIS366 motif in STING constitutes an IRF3-binding motif, which recruits IRF3 for phosphorylation by TBK111,17. The phosphorylated tail of STING may engage TBK1 and IRF3 simultaneously, thereby delivering IRF3 to TBK1 for phosphorylation.

METHODS

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Protein expression and purification

The expression and purification of both human and chicken STING proteins are described in the accompanying paper12. Human TBK1 fused to T6SS secreted immunity protein 3 (Tsi3) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa at the C terminus was expressed and purified, as described for Tsi3-tagged STING in the accompanying paper12. The first step of the purification was based on the high-affinity interaction between the Tsi3-tag and the T6SS effector protein Tse3 conjugated to sepharose 4B resin18. Human TBK1 with a C-terminal Flag-tag (TBK1–Flag) in the pTY-TBK1 D135N-Flag-puro vector for cryo-EM analyses was expressed in Expi293F cells (Gibco by Life Technologies), cultured in Expi293 expression medium at 37 °C under 8% CO2 in an incubator shaker (Eppendorf). These cells and other cells used in the study were assumed to be authentic as from the commercial sources and therefore not independently authenticated. Cells were routinely checked to ensure no mycoplasma contamination by using methods such as DAPI staining and the e-Myco Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Bulldog Bio). When the cell density reached 2.5 × 106 cells/ml with >95% viability, the TBK1 plasmid was transfected into the cells. For 1 litre of cell culture, 1 mg of plasmid was gently mixed with 2.7 ml of polyethylenimine (PEI, 1 μg/μl) (Polyscience, 25 kDa, linear) in 50 ml Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium for 20 min before transfection. Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were collected and resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche). After sonication on ice, the suspension was centrifuged at 1,000g. The supernatant was supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM, Anagrade), incubated at 4 °C for 1 h and then centrifuged at 21,000g for 20 min. The TBK1–Flag protein in the supernatant was captured by anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) and eluted with Flag peptide (Sigma) at 200 μg/ml in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 300 mM NaCl. The protein was further purified by Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare). To reconstitute the TBK1–STING complex, TBK1, STING and cGAMP at a 1:3:3 molar ratio were mixed in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.03% DDM/CHS solution (Anagrade) and incubated on ice overnight. The complex was purified on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare). Peak fractions were concentrated and kept at −80 °C for cryo-EM studies.

Cryo-EM data collection

The STING–TBK1 complex samples at 4.5 mg/ml were applied to a glow-discharged Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 300-mesh gold holey carbon grid (Quantifoil, Micro Tools). Grids were blotted under 100% humidity at 4 °C and plunged into liquid ethane using a Mark IV Vitrobot (FEI). Initial screening showed that particles of the hybrid complex between human TBK1 and chicken STING were much more homogenous than the complex of human TBK1 and human STING. The hybrid complex was therefore chosen for automated micrograph acquisition using the EPU software (FEI) on a Titan Krios microscope (FEI) operated at 300 kV. The K2 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan) was set to the super-resolution counting mode, with the super-resolution pixel size of 0.535 Å. The GIF-Quantum energy filter was set to a slit width of 20 eV. Micrographs were dose-fractioned into 30 frames with a total exposure dose of 48 e− per pixel.

Image processing and 3D reconstruction

Motion correction with twofold binning (1.07 Å per pixel), and dose-weighting and CTF correction were conducted using the Motioncorr2 and Gctf programs, respectively19,20. Relion 2.0 was used for all the following image processing steps21. Approximately 1,000 particles picked from several micrographs were subjected to 2D classification, which were chosen as templates for automated particle-picking from the entire dataset of 2,671 micrographs. Particles were extracted and binned fourfold, which resulted in a pixel size of 4.28 Å. Two-dimensional classification of particles clearly showed that the relative orientation between STING and TBK1 was highly variable. Particles belonging to good 2D classes were chosen for 3D classification using an initial model generated from a subset of the particles. Three of the total eight 3D classes were identified as the STING–TBK1 complex. Owing to the substantial differences in the relative orientation between the two proteins in these 3D classes, only one class showing high-resolution features was selected for subsequent 3D refinement. Particles from this class were re-extracted to the original pixel size of 1.07 Å. Three-dimensional refinement and post-processing led to a reconstruction at an overall resolution of 4.4 Å. Density for TBK1 in the reconstruction was of relatively high resolution, whereas that for STING was of low resolution.

A focused reconstruction for TBK was carried out on the basis of the reconstruction of the STING–TBK1 complex. Particles were re-picked on the basis of the references with TBK1 density centred in the middle of the box. One class that showed clear secondary structural features of TBK1 was selected after 3D classification. Subsequent 3D refinement and post-processing with C2 symmetry imposed led to a reconstruction at a resolution of 3.3 Å. The map was of high quality and used for model building.

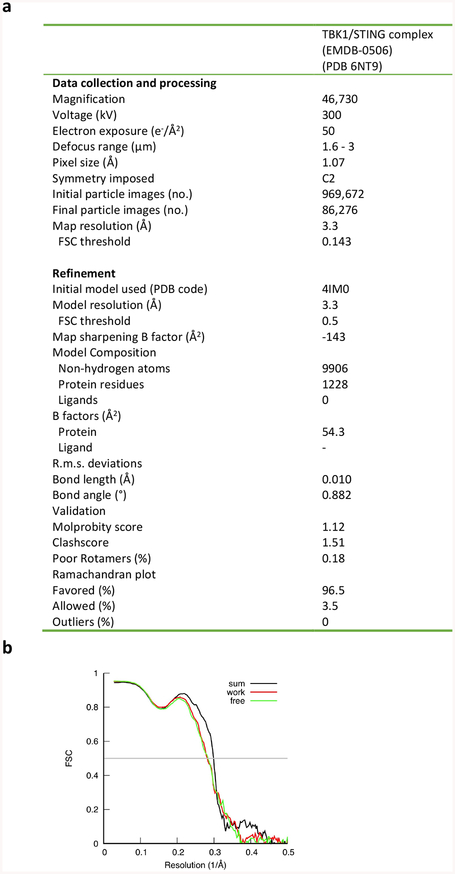

Model building, refinement and validation

Owing to the poor resolution, no manual model building was conducted on the basis of the reconstruction of the full STING–TBK1 complex. The structures of human TBK1 and chicken STING were fit into the density by rigid-body docking using Chimera and Coot. Atomic model building of the TBK1-focused reconstruction was initiated by docking the TBK1 structure (PDB code 4IM0) and subsequent manual building in Coot22. In principle, the sample might contain a mixture of the TBK1 dimer bound to zero, one or two STING tails, which could not be distinguished in the refined map owing to the C2 symmetry imposed in 3D refinement. If this was the case, the density for the STING TBM would be expected to be weaker than the surrounding residues in TBK1. However, Extended Data Fig. 3 shows that the densities for the STING TBM and the surrounding TBK1 residues are similar, which suggests that—at least in the subset of the particles used for the focused refinement—both of the binding sites in the TBK1 dimer are occupied by the STING TBM. Real-space refinement was carried out using Phenix, with secondary structure restraints and non-crystallographic symmetry restraints23. Model geometries were assessed with MolProbity as a part of the Phenix validation tools24 (Extended Data Fig. 8). When modelling building for TBK1 was finished, two pieces of strong density remained unaccounted for; these were assigned to two copies of the C-terminal-tail segments (residues 369–377) from chicken STING after careful inspection of the map, and consideration of the sequence and structure of STING. The final model contains the STING C-terminal and most residues in TBK1. The activation loop (residues 160–174), the C-terminal region (residues 659–729) and as well as a few other loops in TBK1 were not included in the atomic model owing to poor density. Overfitting was tested by refining the model with coordinates randomly shifted by 0.2 Å against one of the half maps calculated from half of the dataset in Relion (half-map 1). Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curves were calculated for the model in relation to half-map 1 and half-map 2, and then compared with the FSC for the summed map. The good agreement between the three curves indicates that there was no overfitting (Extended Data Fig. 8). Structures and maps in the figures were rendered with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, v.2.0, Schrödinger), Coot or Chimera22,25. The sequence-alignment figure was generated with ESPript26.

Constructs for cell-based assays

For transient transfection, STING–Flag and TBK1–Flag were generated by cloning the coding sequences into the p-CMV-Flag-N2 and pTY-Flag-puromycin vector, respectively. For generating stable cell lines, STING was cloned into the gateway cloning vector CSII-EF-DEST-IRES-blasticidin or CSII-EF-DEST-IRES-hygromycin, both of which are lentiviral expression vectors. STING was also cloned into the pCDH-CMV-MCS-IRES-puro lentivirus vector. TBK1 was cloned into the pCDH-CMV-MCS-IRES-neo lentivirus vector. Mutations were introduced by Quikchange mutagenesis (Agilent).

Antibodies

Rabbit antibodies used in immunoblotting—including anti-STING, pSTING (S366), TBK1, pTBK1 (Ser172), pIRF3 (S396) and GAPDH antibodies—were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Mouse anti-His6 antibody was also from Cell Signaling Technology. Mouse antibody against human TBK1 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-Flag antibody (M2), anti-tubulin antibody and M2 affinity gel were purchased from Sigma.

In vitro binding assays for STING and TBK1

Tsi3-tagged TBK immobilized on Tse3-conjudated Sepharose 4B resin as mentioned above was used to pull down full-length STING or STING(1–343) (that is, STING lacking the C-terminal tail), with or without cGAMP bound, in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT and 0.02% DDM. His6-tagged Tsi3 protein on the same resin was used as a negative control. Resin was washed three times with the same buffer. Proteins that remained on the resin were analysed by western blot. For co-immunoprecipitation experiments with Flag-tagged STING and His8-tagged TBK1 (TBK1–His8) (Fig. 2e), TBK1 contains a D135N substitution at the kinase active site to render it catalytically dead. The STING–Flag protein was first captured on anti-Flag M2 resin in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% DDM/CHS (10:1) and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche). The resin was washed 3 times using a wash buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.25% DDM/CHS (10:1). TBK1–His8 was purified with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) using a strategy similar to that for TBK1–Flag purification, except for the elution procedure. TBK1–His8 protein was incubated with STING bound to anti-Flag M2 affinity resin for 3 h at 4 °C and washed three times. The resin was boiled in SDS-loading buffer and analysed by Coomassie blue staining and immunoblotting.

Cell culture, transfection and reagent treatment

HEK293T and HeLa cells were from ATCC. HEK293T cells that lack TBK1 and HeLa cells that lack cyclic GMP–AMP synthase were generated by CRISPR–Cas9. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), penicillin and streptomycin (100 IU/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively, Gibco by Life Technologies) and 1× nonessential amino acids (Gibco by Life Technologies). Endogenous STING expression is undetectable in these cells. Cell lines that stably express various forms of STING or TBK1 through lentivirus transduction were selected with 8 μg/ml blasticidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 μg/ml hygromycin (Alexis Biochemicals) or 2 μg/ml puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the corresponding selection markers of the constructs. Expi293F cells for TBK1 overexpression were growing in Expi293 expression medium (Gibco by Life Technologies).

IFNβ–luciferase reporter assay

For expression of the STING wild type and mutant constructs, HEK293T cells that stably express the IFNβ–luciferase–puromycin reporter were transiently transfected with STING plasmids. For expression of TBK1 in HEK293T TBK1-knockout cells, the cells were first transfected with STING lentivirus, followed by transfection with TBK1 wild type and mutant lentivirus. The stable cell lines were transiently transfected with IFNB-luciferase plasmid DNA and stimulated with indicated doses of cGAMP. Cells were stimulated with indicated doses of cGAMP 10 h after transfection. After an additional 14-h incubation, the luciferase assay was performed following the standard protocol (Promega, E1501).

Analyses of the STING–TBK1 interaction by immunoprecipitation

To determine STING–TBK1 complex formation in cells, STING–Flag wild type or mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells. After cGAMP (1 μM) stimulation for 1 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared in a lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1mM Na3VO4 and Roche protease inhibitor set). Cleared supernatants were incubated with anti-Flag (M2) agarose beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 2 h. Agarose beads were washed three times with the lysis buffer, and co-precipitated proteins were detected by immunoblotting. Alternatively, HEK293T TBK1-null cells that stably express STING–Flag were transfected with the TBK1 wild type or mutants, using lentivirus. Cells that stably express STING and TBK1 were stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h. The same immunoprecipitation process as described above was performed to determine the interaction of the STING wild type with the TBK1 wild type or mutants.

In vitro phosphorylation assay

HEK293T cells that express the STING wild type or mutants were collected and resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche). After micro-sonication, the suspension was centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min to generate the S1 post-nuclear supernatant. Phosphorylation reactions were carried out by incubating the S1 fraction in 20 μl 1× kinase reaction buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 2mM ATP and 2 μM cGAMP) at 30 °C for 30 min. The samples were then subjected to SDS–PAGE or native PAGE. STING, pSTING and pTBK1 were visualized by immunoblotting with specific antibodies.

Analyses of STING oligomerization by native gels

For analysing the STING oligomers in the cell-based assay, HeLa cells that stably express human STING wild type or mutants were treated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h. Cells were then resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche) and sonicated. Lysates were centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min to generate the S1 supernatant. The supernatant in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1% NP40, 5% glycerol, 80 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor (Roche) was subjected to native PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against STING. For analysing the STING oligomers in the in vitro phosphorylation assay, HEK293 cells that transiently express STING wild type or mutants, resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche), were sonicated and centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min. The S1 supernatant in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM DTT was mixed with ATP and cGAMP. After the reaction, the samples were extracted with 1% NP40 and subjected to native PAGE, and immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against STING or pSTING.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

For high-resolution imaging, indicated HeLa and HEK293T cells with STING and TBK1 expression were growing on cover glasses or four-well glass-bottom chambers (Laboratory-Tek). HeLa cells deficient in cyclic GMP–AMP synthase were transfected with the STING wild type or mutants, and stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h. HEK293T TBK1-null cells were stably transfected with the STING wild type, and then with the TBK1 wild type or mutants. These cells were also stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) for 1 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscope Sciences) for 15 min. For immunofluorescence microscopy, fixed cells were incubated with anti-rabbit STING and anti-mouse TBK1 antibodies, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 nm and 568 nm, respectively (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Confocal images were acquired on a Nikon A1R Confocal microscope using a 60× (NA 1.45) objective.

Extended Data

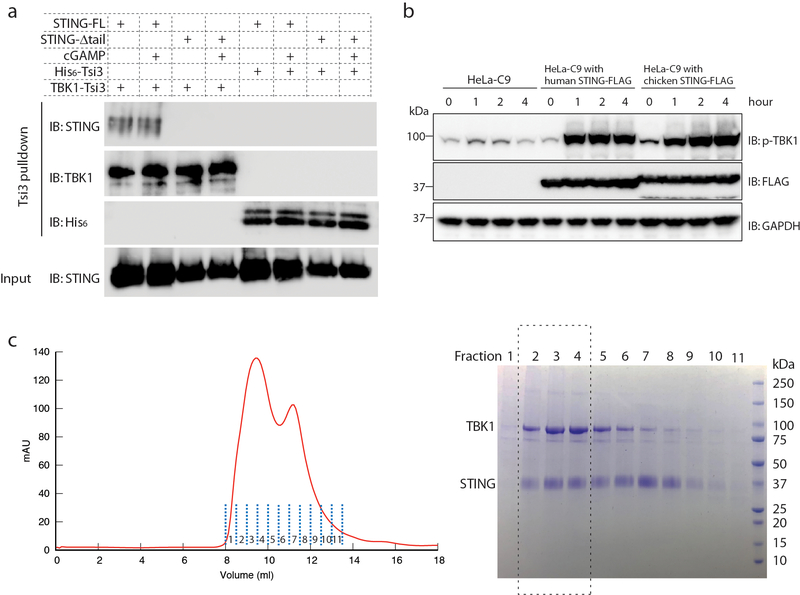

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Purification of STING and TBK1, and characterization of their interaction.

a, Binding between purified human STING and TBK1. Tsi3-tagged TBK1 was captured by Tse3-conjugated beads. Pull down of STING by TBK1 was assessed by western blot. STING-Δtail, STING(1–343). b, Both human and chicken STING are able to induce phosphorylation of human TBK1 in cells. HeLa-C9 cells with undetectable endogenous STING were used to generate cell lines that stably express human STING–Flag or chicken STING–Flag. Cells were stimulated with cGAMP (1 μM) and analysed for TBK1 phosphorylation by immunoblotting. c, Gel filtration chromatography of the hybrid complex between chicken STING and human TBK1. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 2 |. Flow chart of cryo-EM image processing for the complex between chicken STING and human TBK1.

a, Representative micrograph. b, Representative 2D classes of the intact complex. c, Representative 2D classes from TBK1-focused image processing. n > 3. d, f, Final reconstructions of the intact STING–TBK1 complex (d) and from the TBK1-focused refinement (f), with colours based on local resolution. e, g, Gold-standard FSC curves of the final 3D reconstructions of the intact complex and from the TBK1-focused refinement. h, Image processing procedure.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Sample density maps.

Sample density maps are shown for the C-terminal tail of chicken STING and various parts of human TBK1.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Structural comparison of apo TBK1 and TBK1 bound to STING.

The structure of apo TBK1 is from PDB code 4IM0.

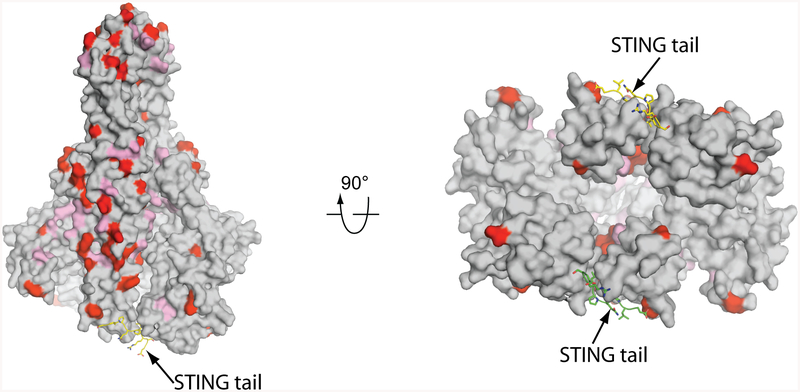

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Sequence conservation of TBK1 from human and chicken.

Residues that are identical in the TBK1 of both species are coloured grey. Non-conserved residues are coloured red; non-identical, but similar, residues are coloured pink.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. The binding and phosphorylation of STING by TBK1 relies on the interface between TBK1 and the STING C-terminal tail, and on the oligomerization of STING.

a, Mutations of TBK1-binding residues in the STING tail diminish cGAMP-induced phosphorylation of both TBK1 and STING. The S1 post-nuclear supernatant from HEK293T cells that express either the STING wild type or mutants was incubated with ATP in the presence or absence of cGAMP, and subjected to immunoblotting analyses for pTBK1, pSTING and STING. b, c, Mutations of TBK1-binding residues in the STING tail diminish cGAMP-induced STING phosphorylation (b) but not STING oligomerization (c). The same samples as in a were resolved by native gels, and analysed by immunoblotting. d–f, Mutations at the oligomerization interface of STING reduce cGAMP-induced oligomerization of STING, as well as phosphorylation of TBK1 and STING. The mutants are based on the accompanying paper on the structures of full-length STING12. The analyses in d, e and f were conducted in the same manner as in a, b and c, respectively. Data shown here are representative of at least three independent biological replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Cartoon model of STING-mediated activation of TBK1 and the downstream signalling pathway.

The cGAMP-induced oligomerization of STING leads to TBK1 clustering and trans-autophosphorylation. Activated TBK1 phosphorylates STING C-terminal tails that are not bound to the SDD–kinase domain groove in TBK1. Phosphorylated tails of STING recruit IRF3, which is phosphorylated by TBK1. Phosphorylated IRF3 forms a dimer and translocates to the nucleus to initiate the transcription of IFN genes.

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Data collection and model statistics.

a, Data collection and model refinement statistics. b, FSC curves between the maps and model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Cryo-EM data were collected at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) Cryo-Electron Microscopy Facility, which is funded by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Core Facility Support Award RP170644. We thank D. Nicastro for facility access and data acquisition. This work is supported in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (Z.J.C.), grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM088197 and R35GM130289 to X.Z), grants from the Welch foundation (I-1389 to Z.J.C.; I-1702 to X.Z; I-1944 to X.-c.B) and grants from CPRIT (RP150498 to Z.J.C.; RP160082 to X.-c.B.). X.-c.B. and X.Z. are Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholars in Medical Research at UTSW. Z.J.C. is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

The cryo-EM map of the TBK1–STING tail complex has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under the accession number EMD-0506. The atomic coordinates of the complex have been deposited in the PDB under the accession number 6NT9.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reviewer information Nature thanks Andrea Ablasser, Philip Kranzusch and Osamu Nureki for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Li T & Chen ZJ The cGAS–cGAMP–STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J. Exp. Med 215, 1287–1299 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X & Chen ZJ Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339, 786–791 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J et al. Cyclic GMP–AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science 339, 826–830 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishikawa H & Barber GN STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature 455, 674–678 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong B et al. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity 29, 538–550 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saitoh T et al. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20842–20846 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin L et al. MPYS, a novel membrane tetraspanner, is associated with major histocompatibility complex class II and mediates transduction of apoptotic signals. Mol. Cell. Biol 28, 5014–5026 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdette DL et al. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature 478, 515–518 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X et al. Cyclic GMP–AMP containing mixed phosphodiester linkages is an endogenous high-affinity ligand for STING. Mol. Cell 51, 226–235 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai X, Chiu YH & Chen ZJ The cGAS–cGAMP–STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol. Cell 54, 289–296 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S et al. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science 347, aaa2630(2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shang G et al. Cryo-EM structures of STING reveal its mechanism of activation by cyclic GMP–AMP. Nature (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai XC, Rajendra E, Yang G, Shi Y & Scheres SH Sampling the conformational space of the catalytic subunit of human γ-secretase. eLife 4, e11182(2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larabi A et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of activation of TANK-binding kinase 1. Cell Reports 3, 734–746 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu D et al. Structure and ubiquitination-dependent activation of TANK-binding kinase 1. Cell Reports 3, 747–758 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shu C et al. Structural insights into the functions of TBK1 in innate antimicrobial immunity. Structure 21, 1137–1148 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao B et al. Structural basis for concerted recruitment and activation of IRF-3 by innate immune adaptor proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E3403–E3412 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu D et al. Structural insights into the T6SS effector protein Tse3 and the Tse3-Tsi3 complex from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveal a calcium-dependent membrane-binding mechanism. Mol. Microbiol 92, 1092–1112 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng SQ et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K Gctf: real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheres SH RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol 180, 519–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen VB et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersen EF et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI & Metoz F ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 15, 305–308 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.