Abstract

Our understanding of the biological role of N 6-methyladenosine (m6A), a ubiquitous non-editing RNA modification, has increased greatly since 2011. More recently, work from several labs revealed that m6A methylation regulates several aspects of mRNA metabolism. The “writer” protein METTL3, known as MT-A70 in humans, DmIme4 in flies, and MTA in plants, has the catalytic site of the METTL3/14/16 subunit of the methyltransferase complex that includes many other proteins. METTL3 is evolutionarily conserved and essential for development in multicellular organisms. However, until recently, no study has been able to provide a mechanism that explains the essentiality of METTL3. The addition of m6A to gene transcripts has been compared with the epigenetic code of histone modifications because of its effects on gene expression and its reversibility, giving birth to the field of epitranscriptomics, the study of the biological role of this and similar RNA modifications. Here, we focus on METTL3 and its likely conserved role in profilin regulation in neurogenesis. However, this and many other subunits of the methyltransferase complex are starting to be identified in several developmental processes and diseases. A recent plethora of studies about the biological role of METTL3 and other components of the methyltransferase complex that erase (FTO) or recognize (YTH proteins) this modification on transcripts revealed that this RNA modification plays a variety of roles in many biological processes like neurogenesis. Our work in Drosophila shows that the ancient and evolutionarily conserved gene profilin (chic in Drosophila) is a target of the m6A writer. Here, we discuss the implications of our study in Drosophila and how it unveils a conserved mechanism in support of the essential function of METTL3 in metazoan development. Profilin (chic) is an essential gene of ancient evolutionary origins, present in sponges (Porifera), the oldest still extant metazoan phylum of the common metazoan ancestor Urmetazoa. We propose that the relationship between profilin and METTL3 is conserved in metazoans and it provides insights into possible regulatory roles of m6A modification of profilin transcripts in processes such as neurogenesis.

Keywords: m6A effector, profiling, IME4, alternative splicing, RNA processing alterations

Introduction

Dozens of RNA modifications have been identified to date. However, the function of these chemical modifications in gene transcripts remains largely elusive (Hsu et al., 2017). One of the best studied is the N 6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification. The m6A modification is the most abundant non-editing internal modification of eukaryotic mRNA (Yue et al., 2015). The m6A modification is added by METTL3/14/16 writer proteins, which are members of the methyltransferase complex (Liu and Pan 2016). METTL3 and its homologs, IME4 (yeast), Dm Ime4 (Drosophila), MTA (Arabidopsis), and MT-A70 (human), have the catalytic structure for Ado-Met binding and subsequent methylation of adenosine residues by the methyltransferase complex (Clancy et al, 2002), while the other components of the complex aid in the recognition of the RNA consensus sequence that contains the adenosine to be methylated, which is frequently found in the context of hairpin configurations (Wang et al., 2016). For simplicity, we will call all these homologs Mettl3 throughout this article. In addition to the Mettl3/14/16 subunit, other proteins are an integral part of the methyltransferase complex. Among these other proteins are Zf3h13, WTAP, Virilizer, Spenito, Hakai, KIAA1429, and RBM15. It is not yet understood whether all the components of the methyltransferase complex are present in every cell of every organism and in every developmental context or whether the composition of the methyltransferase complex is developmentally regulated and varies depending on cell type, organism, and developmental stage. However, the Mettl3 proteins are constant components of this complex and evolutionarily conserved throughout metazoans. The m6A mark on RNA is recognized by readers such as YTH proteins, and it is reversible, as it can be removed by eraser proteins such as FTO (Cao et al., 2016; Liu and Pan 2016; Roundtree et al., 2017; Spychala and Ruther, 2019). m6A can potentially regulate several aspects of RNA metabolism depending on where this mark resides on the RNA molecule (Liu and Pan 2016). The location of the modification on the transcript is thought to regulate specific aspects of RNA metabolism (Liu and Pan 2016; Covelo-Molares et al., 2018). For example, the modification in the 5′UTR results in translation regulation, while the modification in the 3′UTR regulates RNA stability (Wang et al., 2014; Liu and Pan, 2016).

Errors in the incorporation of this modification onto RNA have detrimental consequences in biological processes, such as angiogenesis, stem cell maintenance, gametogenesis, and development, and can cause cancers (Niu et al., 2013; Miao et al, 2019). Recent investigations suggest brain development is another process that relies on this modification (Angelova et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018; Spychala and Ruther, 2019). Given the function of the brain in learning and memory, two processes that rely on neuronal plasticity, it is not surprising that the epitranscriptome is the key regulatory layer of gene regulation in brain function. Proteins involved in processing the m6A modification are being assigned important roles in neurological development (Shi et al., 2018). Mettl3 and other components of the methyltransferase complex have strong localization in eukaryotic neuronal tissue (Angelova et al., 2018). For example, YTH readers are expressed at high levels in Drosophila and murine brain tissue (Hartmann et al., 1999; Lence et al., 2016). An additional example is the FTO eraser protein, which is expressed at high levels in human and murine hypothalamus (McTaggart et al., 2011; Angelova et al., 2018; Spychala and Ruther, 2019). Besides localization, additional studies suggest a more direct connection of the methyltransferase complex to neurological disorders. For instance, the Zfh13 appears to be a marker for schizophrenia, a neurological disorder (Oldmeadow et al., 2014). Zfh13 was shown to have a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation in schizophrenia patients using genome-wide screening. Interestingly, one of the best characterized members of the methyltransferase complex, the writer protein Mettl3, has also been shown to be required for brain development and function (Visvanathan et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018).

Mettl3, the catalytic subunit of the methyltransferase complex (Clancy et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2018), is encoded by an essential gene in many eukaryotic organisms (Zhong et al., 2008; Hongay and Orr-Weaver 2011; Guela et al., 2015; Rockwell et al., 2019). Since mettl3 is essential, manipulating the gene to determine its function in vivo has been challenging (Rockwell et al., 2019). Therefore, most studies are performed ex vivo, using cell and tissue cultures or in vitro with partial biochemical reconstructions of the complex and its substrates. Consequently, the mechanism of Mettl3 in processes such as brain development in vivo and in the context of a whole organism is not completely understood. To circumvent this challenge, we have manipulated the expression levels of mettl3 via RNAi to bypass its essential requirement for viability and observed the consequences of mettl3 ablation in the non-essential developmental context of spermatogenesis (Rockwell et al., 2019). Using the aforementioned experimental approach, we have found that profilin (chic in Drosophila) transcript and protein levels are affected by reduction of Mettl3. We postulate that Mettl3’s regulation of profilin is conserved in other metazoans and developmental scenarios. Given that profilin is an ancient, evolutionarily conserved, and essential protein required for metazoan development (Müller, 2003; Müller and Müller, 2003), the regulation of profilin by Mettl3 can shed light on Mettl3’s role in evolutionarily conserved and essential biological processes that require profilin function such as brain development.

Mettl3’s Role in Profilin Splicing and Processing

In most eukaryotes, multiple variants of a protein are generated by alternative splicing of the transcripts that are encoded by a gene. Alternative splicing is developmentally regulated, and genes can generate specific protein variants (spliceoforms) according to the developmental stage of the organism and cell type, tissue type, and organ type. Profilin genes can generate different spliceoforms (Witke 2004). The spliceoforms of profilin are often tissue specific (Witke 2004). Unfortunately, the mechanism that determines which spliceoform is generated in certain cells but not others is not completely understood. Our soon to be published studies in Drosophila show that Mettl3 is required for profilin (chic) splicing. Controlled depletion of Mettl3 to bypass its essential function using the Gal4–UAS system resulted in accumulation of unspliced chic transcript. Ours is the first study that postulates a possible mechanism for profilin splicing. Although our work shows this interaction in Drosophila’s spermatogenesis, for this review, we use sequencing data publicly available in the genome browser (described in Kent et al., 2002) to identify Mettl3’s consensus binding sites in silico in mammalian profilin mRNAs to propose that Mettl3 may interact with profilin transcripts in other metazoans, specifically mammals.

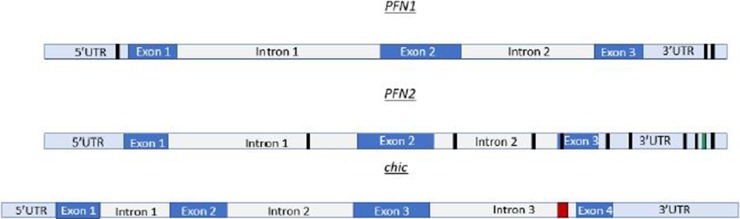

The in silico analysis of profilin transcripts reveals multiple Mettl3 binding sites. For example, mRNA sequencing data in humans show multiple Mettl3 bindings sites on profilin 1 (PFN1) and profilin 2 (PFN2) ( Figure 1 ). In Drosophila, there are a cluster of Mettl3 binding sites in the chic (profilin) transcript ( Figure 1 ). PFN1 is homologous to chic in Drosophila. For our in silico inquiry, we used consensus sequences known to have high affinity for Mettl3 binding. The sequences used in Figure 1 are AAACC (PFN1), AAACA and UGUGGACU (PFN2), and GTTCTTATTTCTCCGCCGCTGA CGGTG (chic). These binding sites are localized on different portions of the transcript. Some of these binding sites are in the 5′UTR and 3′UTR, while others are in the exon and intron regions. PFN2 has many Mettl3 binding sites throughout the transcript, which include the 3′UTR, exon 3, intron 1, and intron 2. There are two known spliceoforms of PFN2 (PFN2a and PFN2b). We propose that recognition and use of these sites by Mettl3 aided by the other components of the methyltransferase complex may vary in different developmental contexts to generate the spliceoforms needed to be synthesized. Conversely, PFN1 only has a few Mettl3 binding sites, two in the 3′UTR and one in the 5′UTR. Taken together, our studies in Drosophila and the in silico identification of Mettl3 binding sites on profilin transcripts ( Figure 1 ) suggest an evolutionarily conserved relationship between the methyltransferase complex and the regulation of the expression of this ancient gene. Interestingly, a similar Mettl3 recognition site is present in PFY1, the profilin gene in budding yeast.

Figure 1.

Profilin transcripts have multiple Mettl3 binding sites. PFN1 mRNA, depicted in cartoon form at the top, has Mettl3 binding sites (AAACC) depicted by black boxes in the 3′UTR and 5′UTR. PFN2 mRNA represented as the transcript in the middle of this figure, has Mettl3 binding sites (AAACA) in the 3′UTR, exon 3, intron 1, and intron 2. PFN2 mRNA has additional binding sites in 3′UTR represented by green box (UGUGGACU). chic (Drosophila profilin), depicted as the bottom cartoon in this figure, has a cluster of METTL3 binding sites (GTTCTTATTTCTCCGCCGCTGACGGTG) in intron 3 represented by red box. This cluster, when run through appropriate algorithms, can generate hairpins for complex recognition.

The Methyltransferase Complex in Neurogenesis

Mettl3 plays a role in neurogenesis in mammals and Drosophila. Mettl3 is essential in mouse, as a complete deletion of this gene results in early embryonic arrest (Geula et al., 2015). In mouse, m6A methylation regulates cortical neurogenesis (Yoon et al., 2017). Depletion of Mettl3 and/or Mettl14 in murine results in decreased m6A levels (Yoon et al., 2017). Knockdown of Mettl3 in mouse using an in vivo short hairpin RNA shRNA technique results in an increase in the length of the cell cycle and defects in maintenance of radial glial cells (Yoon et al., 2017). Mettl14 conditional knockout using the Nestin–Cre system in mouse embryos also results in a prolonged cell cycle and longer cortical neurogenesis (Yoon et al., 2017). Besides the cortical neurogenesis investigation, other studies also found defects in m6A modification impacted normal neuronal capabilities. For example, Mettl14 deletion in two striatum subgroups resulted in decrease in m6A levels (Koranda et al., 2018). This decrease in m6A levels coincided with increase neuronal excitability and impaired striatum function, likely due to mRNA levels encoding synapse specific proteins being downregulation (Koranda et al., 2018). Another study that examined the impact of m6A in synapses found this modification is likely required for proper synapse function (Merkurjev et al., 2018). Additionally, depletion of METTL3 using Lox-Cre in mouse results in an altered epitranscriptome and abnormal behavioral defects (Engel et al., 2018). The altered epitranscriptome is likely affecting proteins needed for proper brain function such as profilin. Similarly, in Drosophila, depletion of the Mettl3 results in abnormal behavioral defects, a flightless phenotype, and aberrant neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) (Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016). The locomotion and flightless defects are likely related and possibly due to defects in NMJ characterized by a “held-out wing” phenotype (Haussmann et al., 2016; Lence et al., 2016), the basis of which has yet to be determined. Here, we propose that the common thread of these neurological defects, which have been described but not molecularly analyzed, may be profilin.

Profilin Molecular Function and Neuronal Expression Pattern

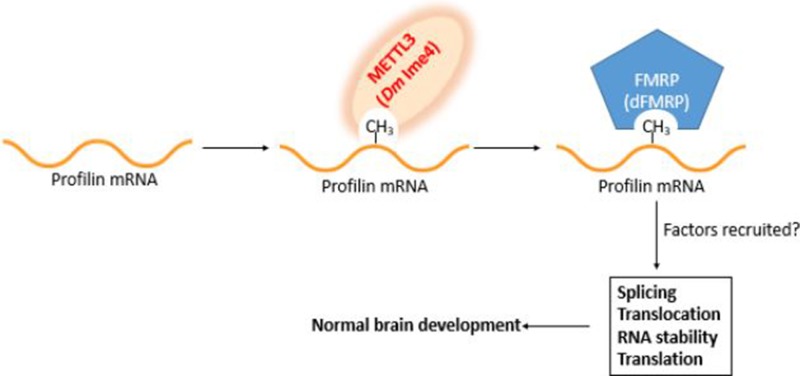

Profilin is an essential gene in development (Witke 2004; Geula et al., 2015). Profilin has several proposed roles in the cell ( Figure 2 ). The best characterized function is as actin binding protein required for F-actin polymerization, a housekeeping role, and as such, mammalian PFN1 is ubiquitously expressed. Conversely, profilin 2a (PFN2a and PFN2b) is not a housekeeping gene, and it is only expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), primarily in brain tissue (Witke 2004). PFN1 has a strong affinity for actin and poly--proline, and it typically binds ligands that range from 45 to 190 kDa. PFN2a is like PFN1, as it also has a high affinity for actin and poly--proline (Dinardo et al., 2000). Interestingly, PFN2b does not bind actin and has a lower affinity for poly--proline (Dinardo et al., 2000). PFN2b has a strong affinity for tubulin. In Drosophila, there are several annotated profilin spliceoforms that generate from chic (Kent et al., 2002). However, only ovary-specific and constitutive spliceoforms have been identified (Verheyen et al., 1994). There are still spliceoforms that need to be characterized. It is possible that epitranscriptome modifications are required for the processing of these spliceoforms in a tissue-specific manner, and future studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Working model for profilin regulation in the brain. Profilin pre-mRNA is methylated by Mettl3 upon binding site recognition aided by Mettl14/16 and other components of the methyltransferase complex. The m6A mark is recognized by the m6A reader FMRP (dFMRP). The marking and its recognition are required for the recruitment of splicing and processing factors. Failure to properly mark and recognize profilin pre-mRNA has deleterious consequences in brain development.

PFN1 in Neurogenesis

Many proteins are required to regulate neurogenesis. PFN1, a protein that is vital for a glial cell’s function, is one of these. In Schwann cells (SCs), PFN1 is required for lamellipodia formation, a key requirement for myelination (Montani et al., 2014). It was found that when shRNA was used to knockdown PFN1 in SC cultures, the knockdown resulted in reduced formation of axial and radial lamellipodia (Montani et al., 2014). Myelination is important for the propagation of action potentials and normal functioning nervous system. PFN1 regulates cytoskeletal remodeling, which is necessary for lamellipodia formation. PFN1 may play other important roles in neurons. PFN1 is present at the neuronal synapse and colocalizes with the synapse protein synaptophysin (Neuhoff et al., 2005). This suggests a role of profilin and ultimately actin in synapse function. The regulation of PFN1 in the brain is critical for normal neurological function, as defects in PFN1 regulation can result in mental abnormalities (Michaelsen-Preussea et al., 2006). Therefore, the identification of proteins that regulate PFN1 will have important implications in testing and perhaps devising treatments for mental abnormalities. One such protein linked to PFN1 regulation in the brain is the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (Michaelsen-Preussea et al., 2006).

In mouse, FMRP binds directly to PFN1 through a novel RNA binding motif (Michaelsen-Preussea et al., 2006). It is unknown whether the motif recognized by FMRP is a target of the methyltransferase complex. The relationship between PFN1 and is conserved in Drosophila as well. As mentioned previously, PFN1 is homologous to profilin in Drosophila. In Drosophila, FMRP is called dFMRP, and it has been shown to bind to the chic transcript (Reeve et al., 2005). The interaction between dFMRP and chic was examined in an immunoprecipitation experiment using an anti-dFMRP antibody. dFMRP is needed for proper neuronal development and circadian rhythm (Reeve et al., 2005). In Drosophila, dFMRP mutants have defects in cytoskeleton dynamics, which eventually manifest into behavioral abnormalities (Reeve et al., 2005). In humans and mouse, defective FMRP results in fragile X syndrome and other intellectual disorders (IDs) (Michaelsen-Preussea et al., 2006). FMRP knockout mice have low levels of PFN1, which affect translation in dendrites (Michaelsen-Preussea et al., 2006). FMRP has been shown to be critical for normal brain development (Angelova et al., 2018). Interestingly, studies suggest that FMRP is a m6A reader (Angelova et al., 2018). Future studies are needed to investigate the relationship between FMRP and Mettl3, as they may reveal important features of the subunit composition of the methyltransferase complex as a function of cell type specificity. Ex vivo and in vitro, all m6A readers can recognize and bind to transcripts that contain the methylation of N 6 residues on adenosine (Cao et al., 2016; Liu and Pan 2016; Yang et al., 2018). However, it is unknown whether this is true in vivo. We propose that m6A recognition is much more specific in vivo and depends on when and where m6A is added to the target transcript by Mettl3.

PFN2 in Neurogenesis

PFN2 is expressed specifically in brains consistent with PFN2’s requirement for neurogenesis. In mouse, PFN2 is needed for axon and dendritic processes (Witke et al., 1998). PFN2a is required for neuritogenesis, the first step of neuronal differentiation, a process critical for neurogenesis in the developing brain (Da Silva et al., 2003). PFN2a regulates neuritogenesis by regulating actin stability as determined using cultured mouse hippocampal neurons. Reduction of PFN2a levels in hippocampal neurons using a morpholino techniques resulted in neurite branching overgrowth, which is atypical in neuritogenesis. The mechanism that ensures specific expression of the PFN2a isoform in brain is not understood. Based on our in silico analysis ( Figure 1 ), we propose that Mettl3 is required for m6A marking of PFN2 to generate specifically the PFN2a spliceoform in brain tissue during neurogenesis.

Conclusion

It is now widely accepted that modifications to RNA have vital roles in regulating normal cell function. The current work on the m6A modification further supports the importance of RNA modifications in processes such as neurological development. This makes finding targets of the methyltransferase complex that contribute to neurological development significant for advancing translational venues in human health. Here, we describe the profilin transcript as one target that can be methylated and recognized by the methyltransferase complex. Our in silico identification of Mettl3 consensus binding sites along the profilin transcripts show that these sites are located on different parts of the mRNA. Future studies will be needed to discern which of these sites are bound or targeted for methylation by the methyltransferase complex. It is possible that some of the sites are not recognized or that they are only recognized in a cell-type-specific manner, while other sites may act constitutively. Although the composition of the methyltransferase complex has been elucidated, it is still unknown whether the composition of this multi-subunit enzymatic complex is the same in all cells or whether it varies according to cell type, organism, and/or developmental stage. Arguing against ubiquitous marking and recognition of adenosines that are found within the consensus sequence in pre-mRNA is the fact that not every adenosine residue gets methylated. The consensus site needs to be sterically presented in hairpin configurations, and there is steric hindrance provided by the catalytic pockets formed in the Mettl3/14/16 subunits of the methyltransferase complex. Other recognition restrictions can occur by the positioning of other components of the complex. Studying recognition, methylation, and complex composition in the context of profilin m6A marking for mRNA processing can prove a valuable strategy to answer outstanding questions in the field of epitranscriptomics. Mettl3 was the first component of the methyltransferase complex to be identified, and it has been linked to several debilitating neurological conditions that are challenging to diagnose and treat. Further investigation of Mettl3 could open new therapeutic venues and help treat certain neurological conditions. Although this review has focused on profilin as a target, other transcripts remain to be identified and studied. For example, in glioblastoma cells, ADAM19 is an oncogene that promotes tumor progression. Mettl3 normally methylates ADAM19 mRNA, resulting in the degradation of ADAM19 required for tumor suppression (Deng et al., 2018). In glioblastoma cells, Mettl3 is downregulated, leading to upregulation of ADAM19. It is undeniable that, thanks to the recent technological advances, the field of epitranscriptomics is in an accelerated phase of discovery. The role of m6A mRNA as a gene expression regulatory mark will enrich our understanding of gene expression regulation the same way the discovery of the histone modifications did over 30 years ago.

Author Contributions

ALR wrote the fiirst draft and CFH (corresponding author) edited and prepared the review submitted for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by NIH awards 1R15GM1131-01 and PA-12-149 to CH.The authors thank the Genome Education Partnership for providing the tools to perform the in silico search described in this review.

References

- Angelova M. T., Dimitrova D. G., Dinges N., Lence T., Worpenberg L., Carré C., et al. (2018). The emerging field of epitranscriptomics in neurodevelopmental and neuronal disorders. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6 (46), 1–15. 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G., Li H. B., Yin Z., Flavell R. A. (2016). Recent advances in dynamic m6A RNA modification. Open Biol. 6 (4), 16003. 10.1098/rsob.160003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandola U., Das R., Panda B. (2015). Role of the N 6-methyladenosine RNA mark in gene regulation and its implications on development and disease. Brief Funct. Genomics 14 (3), 169–179. 10.1093/bfgp/elu039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy M. J., Shambaugh M. E., Timpte C. S., Bokar J. A. (2002). Induction of sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to the formation of N 6-methyladenosine in mRNA: a potential mechanism for the activity of the IME4 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 (20), 4509–4518. 10.1093/nar/gkf573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covelo-Molares H., Bartosovic M., Vanacova S. (2018). RNA methylation in nuclear pre-mRNA processing. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 9 (6), e1489. 10.1002/wrna.1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva S. J., Medina M., Zuliani C., DiNardo A., Witke W., et al. (2003). RhoA/ROCK regulation of neuritogenesis via profilin IIa-mediated control of actin stability. J. Cell Biol. 162 (7), 1267–1279. 10.1083/jcb.200304021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Su R., Feng X., Wei M., Chen J. (2018). Role of N 6-methyladenosine modification in cancer. Genet. Dev. 48, 1–7. 10.1016/j.gde.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinardo A. D., Gareus R., Kwiatkowski D., Witke W. (2000). Alternative splicing of the mouse profilin II gene generates functionally different profilin isoforms. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3795–3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel M., Eggert C., Kaplick P. M., Eder M., Roh S., Tietze L., et al. (2018). The role of m6A/m-RNA methylation in stress response regulation. Neuron 99 (2), 389–403. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula S., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Dominissini D., Mansour A. A., Kol N., Salmon-Divon M., et al. (2015). m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science 347 (6225), 1002–1006. 10.1126/science.1261417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A. M., Nayler O., Schwaiger F. W., Obermeier A., Stamm S. (1999). The interaction and colocalization of Sam68 with the splicing associated factor YT521-B in nuclear dots is regulated by the Src family kinase p59fyn . Mol. Biol. Cell 10 (11), 3909–3926. 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussmann I. U., Bodi Z., Sanchez-Moran E., Morgan N. P., Archer N., Fray R. G., et al. (2016). m6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature. 540 (7632), 301–304. 10.1038/nature20577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongay C. F., Orr-Weaver T. L. (2011). Drosophila inducer of MEiosis 4 (IME4) is required for Notch signaling during oogenesis. PNAS 108, 14855–14860. 10.1073/pnas.1111577108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. J., Shi H., He C. (2017). Epitranscriptomic influences on development and disease. Genome Biol. 18, 197. 10.1186/s13059-017-1336-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan L., Grozhik A. V., Vedanayagam J., Patil D. P., Pang N., Lim K. S., et al. (2017). The m6A pathway facilitates sex determination in Drosophila . Nat. Commun. 8, 1–16. 10.1038/ncomms15737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W. J., Sugnet C. W., Furey T. S., Roskin K. M., Pringle T. H., Zahler A. M. (2002). Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12 (6), 996–1006. 10.1101/gr.229102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koranda J. L., Dore L., Shi H., Chi W., He C., Zhuang X. (2018). Mettl14 is essential for epitranscriptomic regulation of striatal function and learning. Neuron 99 (2), 283–292. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan K., Moens P. D. J. (2009). Structure and functions of profilins. Biophys. Rev. 1 (2), 71–81. 10.1007/s12551-009-0010-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lence T., Akhtar M., Bayer M., Schmid K., Spindler L., Cheuk H. H., et al. (2016). m6A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila . Nature 540 (7632), 305–318. 10.1038/nature20568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lence T., Soller M., Roignant J. Y. (2017). A fly view on the roles and mechanisms of the m6A mRNA modification and its players. RNA Biol. 14 (9), 1232–1240. 10.1080/15476286.2017.1307484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Pan T. (2016). N 6-Methyladenosine-encoded epitranscriptomics. Nat. Struct. Biol. 23, 98–102. 10.1038/nsmb.3162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart J. S., Lee S., Iberl M., Church C., Cox R. D., Ashcroft F. M. (2011). FTO is expressed in neurones throughout the brain and its expression is unaltered by fasting. PLoS One 6 (11), 1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkurjev D., Hong W. T., Iida K., Oomoto I., Goldie B. J., Yamaguti H., et al. (2018). Synaptic N 6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome reveals functional partitioning of localized transcripts. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1004–1014. 10.1038/s41593-018-0173-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. D., Saletore Y., Zumbo P., Elemento O., Mason C. E., Jaffrey S. R. (2012). Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 149, 1635–1646. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsen-Preussea K., Zessina S., Grigoryana G., Scharkowskia F., Feugea J., Remusa A., et al. (2006). Neuronal profilins in health and disease: relevance for spine plasticity and fragile X syndrome 113, 12, 3365–3370. 10.1073/pnas.1516697113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montani L., Buerki-Thurnherr T., de Faria J. P., Pereira J. A., Dias N. G., Fernandes R., et al. (2014). Profilin 1 is required for peripheral nervous system myelination. Development 141, 7, 1553–1561. 10.1242/dev.101840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W., Chen J., Jia L., Ma J., Song D. (2019). The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes osteosarcoma progression by regulating the m6A level of LEF1 . Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 516 (3), 719–725. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller W. E. G. (2003). The origin of metazoan complexity: porifera as integrated animals. Int. Comp. Biol. 43 (1), 3–10. 10.1093/icb/43.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller W., Müller I. (2003). Origin of the metazoan immune system: identification of the molecules and their functions in sponges. Integr. Comp. Biol. 43 (2), 281–292. 10.1093/icb/43.2.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhoff H., Sassoe-Pognetto M., Panzanelli P., Maas C., Witke W., Kneussel M. (2005). The actin-binding protein profilin I is localized at synaptic sites in an activity-regulated manner. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21 (1), 15–25. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y., Zhao X., Wu Y. S., Yang Y. G. (2013). N 6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: an old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 11, 8–17. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldmeadow C., Mossman D., Evans T. J., Holiday E. G., Tooney P. A., et al. (2014). Combined analysis of exon splicing and genome wide polymorphism data predict schizophrenia risk loci. J. Psychiatric Res. 52, 44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve S. P., Bassetto L., Genova G. K., Kleyner Y., Leyssen M., Jackson F. R., et al. (2005). The Drosophila fragile X mental retardation protein controls actin dynamics by directly regulating profilin in the brain. Curr. Biol. 15, 1156–1163. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell A. L., Beaver I., Hongay C. F. (2019). A direct and simple method to assess Drosophila melanogaster's viability from embryo to adult. J. Vis. Exp. (150), e59996. 10.3791/59996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree I. A., Evans M. E., Pan T., He C. (2017). Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 169 (7), 1187–1200. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree I. A., Luo G. Z., Zhang Z., Wang X., Zhou T., Cui Y., et al. (2017). YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife 6, e31311. 10.7554/eLife.31311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Zhang X., Weng Y. L., Lu Z., Liu Y., Lu Z., et al. (2018). m(6)A facilitates hippocampus-dependent learning and memory through YTHDF1. Nature 563 (7730), 249–253. 10.1038/s41586-018-0666-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spychala A., Ruther U. (2019). FTO affects hippocampal function by regulation of BDNF processing. PLoS One 14 (2), e0211937. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheyen E. M., Cooley L. (1994). Profilin mutations disrupt multiple actin-dependent processes during Drosophila development. Development 120 (4), 717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvanathan A., Patil V., Arora A., Hegde A. S., Arivazhagan A., Santosh V., et al. (2018). Essential role of METTL3-mediated m(6)A modification in glioma stem-like cells maintenance and radioresistance. Oncogene 37 (4), 522–533. 10.1038/onc.2017.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Doxtader K. A., Nam Y. (2016). Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol. Cell 63 (2), 306–317. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. X., Cui G. S., Liu X., Xu K., Wang M., Zhang X. X., et al. (2018). METTL3-mediated m6A modification is required for cerebellar development. PLoS Biol. 16 (6), e2004880. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G. C., Yue Y., Han D., et al. (2014). N 6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505 (7481), 117–120. 10.1038/nature12730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng Y. L., Wang X., An R., Cassin J., Vissers C., Liu Y., et al. (2018). Epitranscriptomic m(6)A regulation of axon regeneration in the adult mammalian nervous system. Neuron 97, 313–325. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witke W. (2004). The role of profilin complexes in cell motility and other cellular processes. Trends Cell Biol. 14 (8), 461–469. 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witke W., Podtelejnikov V., DiNardo A., Sutherland J. D., Gurniak C. B., Dotti C., et al. (1998). In mouse brain profilin I and profilin II associate with regulators of the endocytic pathway and actin assembly. EMBO J. 17 (4), 967–976. 10.1093/emboj/17.4.967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Wang X., Liu K., Roundtree I. A., Tempel W., Li Y., et al. (2014). Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10 (11), 927–929. 10.1038/nchembio.1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Hsu P. J., Chen Y. S., Yang Y. G. (2018). Dynamic transcriptomic m6 A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 28, 616–624. 10.1038/s41422-018-0040-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K. J., Ming G. L., Song H. (2018). Epitranscriptomes in the adult mammalian brain: dynamic changes regulate behavior. Neuron 99 (2), 243–245. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K. J., Vissers C., Jacob F., Pokrass M., Su Y., Song H., et al. (2017). Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m6A methylation. Cell 171 (4), 877–889. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y., Liu J., He C. (2015). RNA N 6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Gene Dev. 29 (13), 1343–1355. 10.1101/gad.262766.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. S., Nachtergaele S., Roundtree I. A., He C. (2018). Our views of dynamic N(6)-methyladenosine RNA methylation. RNA 24 (3), 268–272. 10.1261/rna.064295.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., He C. (2017). Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18 (1), 31–34. 10.1038/nrm.2016.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Li H., Bodi Z., Button J., Vespa L., Herzoq M., et al. (2008). MTA Is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell 5, 1278–1288. 10.1105/tpc.108.058883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]