Abstract

Background:

Depression causes significant burden both to the individual and to society, and its treatment by antidepressants has various disadvantages. There is preliminary evidence that adds on yoga therapy improves depression by impacting the neurotransmitters involved in the regulation of mood, motivation, and pleasure. Our study aimed to find the effect of adjunctive yoga therapy on outcome of depression and comorbid anxiety.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized controlled study involving patients with major depressive disorder (n = 80) were allocated to two groups, one received standard therapy (antidepressants and counseling) and the other received adjunct yoga therapy along with standard therapy. Ratings of depression and anxiety were done using Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at baseline, 10th and 30th day. Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale was applied at baseline and 30th day to view the severity of illness and clinical improvement.

Results:

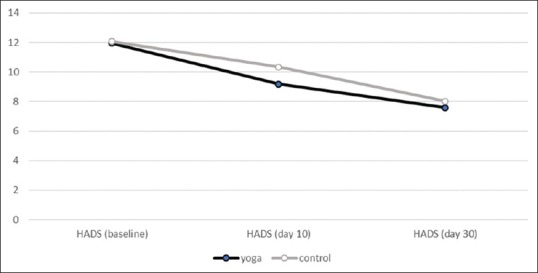

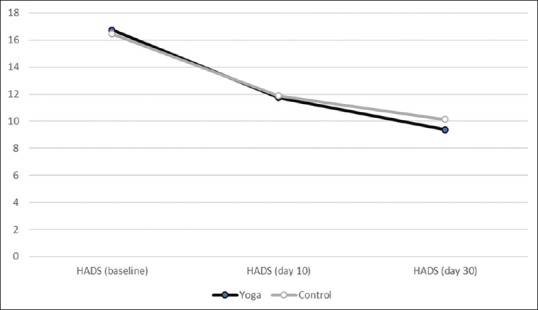

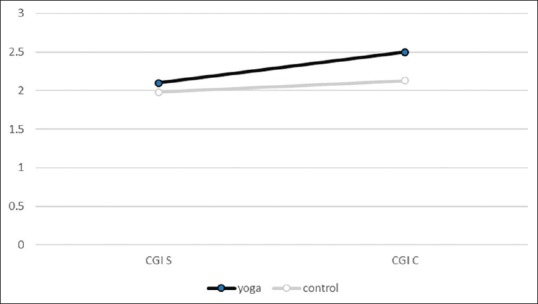

By the 30th day, individuals in the yoga group had significantly lower scores of depression, anxiety, and CGI scores, in comparison to the control group. The individuals in the yoga group had a significant fall in depression scores and significant clinical improvement, compared to the control group, from baseline to 30th day and 10th to 30th day. In addition, the individuals in the yoga group had a significant fall in anxiety scores from baseline to 10th day.

Conclusion:

Anxiety starts to improve with short-term yoga sessions, while long-term yoga therapy is likely to be beneficial in the treatment of depression.

Keywords: Anxiety, clinical improvement, depression, yoga

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent, chronic and disabling disorder, associated with reduced social functioning, impaired quality of life, increased mortality and is currently one of the leading causes of the global burden of disease.[1] It has an estimated prevalence of 6%–20% worldwide with 20% in women and 12% in men during their lifetime, respectively.[2,3] MDD is defined as a period of 2 weeks or longer in which the mood is predominantly low/sad and at least four other symptoms involving changes in weight/appetite, sleep, activity level, energy, concentration, or suicidality. Most individuals with depressive disorders also have comorbid anxiety symptoms.[4]

The role of yoga in health aspects of an individual and the society is multidimensional, as suggested by the emerging evidence of the beneficial effects of yoga therapy in various physical and mental illnesses.[5] Yoga is a practice that is spread across the world, among various cultures and religions. Yoga involves three components: gentle stretching, breath control exercises, and meditation. The origin of yoga dated thousands of years back and was considered as one of the earliest and most effective methods for providing peace and tranquillity of mind. Achievement of the optimum level of self-awareness is believed to be an inherent part of yoga practices.[6] Yoga practices have been shown to have some beneficial changes in neuro-transmitter systems such as serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine, the neuroendocrine system (Hypothalamic Pituitary Axis), changes in neuroplasticity, and the immune system.[7,8] These systems are implicated in the pathophysiology of depression and the anxiety secondary to it.[9] Thus, yoga may be a useful adjunctive treatment for depression. There is a dearth of Indian literature, especially in terms of randomized controlled trials showing the influence of yoga in reducing the severity of depression. Hence, we conducted a randomized control trial to find the effectiveness of adjunct yoga therapy in depressive disorders and its accompanied anxiety symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

A randomized controlled trial was done at the department of psychiatry in a tertiary care hospital from March 2017 to April 2018; all consecutive adult inpatients aged 18 years and above, admitted to the department of psychiatry, with a current depressive disorder (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]-5 criteria) were considered for inclusion into the study, irrespective of the current medication status. Individuals with psychosis, severe cognitive impairment, intellectual disability, requiring electroconvulsive therapy, and those not willing for in-patient care and yoga therapy were excluded. The study period was 30 days during which all the study individuals were admitted and monitored closely for any adverse events. The study was approved by the institutional human ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the study.

Participants fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria were taken up for the study. They were allocated into one of two groups, i.e., yoga group or control group, based on randomization which was done using computer-generated random numbers. The participants randomized to the yoga group received standard therapy/treatment as usual in addition with routine yoga therapy which included minimum 20 supervised yoga sessions, five sessions per week; each lasting 45 min. The yoga sessions were provided by a certified yoga therapist in a separate yoga therapy room. The control group received standard therapy/treatment as usual (antidepressants and psychological intervention). The patient care given was the standard practice for depressive disorder patients. No specific changes were made for the purpose of this particular study other than including adjunct yoga therapy for one group. Participants in both the groups were assessed periodically by the principal investigator and blinding was not done.

Tools

A semi-structured proforma was used to collect information pertaining to sociodemographic details such as age, gender, marital status, area of domicile, socioeconomic status and clinical variables like DSM-5 psychiatric diagnosis, total duration of illness, duration of the current episode, episode number, and treatment history. Ratings of depression and anxiety were done using Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)[10] and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[11] at baseline, day 10 and day 30 in both the groups. The Clinical Global Impression (CGI)[12] scale was used at baseline and on day 30 in both groups to measure the severity of illness and clinical improvement.

The sample size was estimated prior to the study using the standard formula for sample size calculation. Ninety-five patients were screened with reference to the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eight were excluded from the study, based on exclusion criteria. Subsequently, seven patients (4 from yoga group and 3 from control group) were excluded during the study as they got discharged earlier. Hence, the final analysis was done on 80 individuals (40 in each group), who completed the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was done to show the distribution of variables. Independent t-test was used for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables to study the difference between the two groups in terms of sociodemographic and clinical variables. Fall in the scores of MADRS and HADS at 10th day (baseline to 10th day) and 30th day (baseline to 30th day) were calculated. Independent t-test was applied to assess for significant difference between groups in terms of fall in MADRS and HADS scores at 10th day and 30th day. Group difference in the fall of MADRS and HADS scores from 10th day to 30th day was also analyzed. Change in CGI score in both the groups was studied using independent t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 was used for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

The mean age of the total sample was 38.19 ± 11.73 years. The mean age in yoga group was 36.90 ± 10.17 years and in control group was 39.48 ± 13.29 years. Majority of patients in both the groups were married (87.5% in yoga group and 77.5% in control group), belonging to lower and middle class (97.5% in yoga group and 90.0% in control group) and hailing from rural areas (77.5% in yoga group; 60.0% in control group). Majority of the patients in both the groups had MDD (42.5%) followed by Bipolar I disorder current or most recent episode depressed (35.0%) and the least had MDD recurrent episode (2.5%). Majority of the patients in both the groups were treatment-naive (52.5%). The result shows that there is no significant difference in age, gender, socioeconomic status, marital status, area of domicile, total duration of illness, episode number among the yoga and control groups [Table 1]. There is a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding fall in MADRS and HADS depression subscale score on 30th day (P < 0.05) but not on the 10th day (P > 0.05) [Table 2 and Figure 1]. However, there is a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding fall in HADS anxiety score on both 10th day and 30th day (P < 0.05), respectively [Figure 2]. The improvement in CGI scores at 30th day was significantly higher in the yoga group than in the control group [Figure 3].

Table 1.

Comparison of sociodemographic variables across two groups (n=40 each group)

| Variables | Yoga | Control | χ2/t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 36.90±10.17 | 39.48±13.29 | −0.97 | 0.33 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 17 (42.5) | 23 (57.5) | 1.80 | 0.26 |

| Female | 23 (57.5) | 17 (42.5) | ||

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | ||||

| Lower | 19 (47.5) | 20 (50.0) | 1.27 | 0.82 |

| Middle | 19 (47.5) | 17 (42.5) | ||

| Upper | 2 (5.0) | 3 (7.5) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 5 (12.5) | 9 (22.5) | 1.38 | 0.37 |

| Married | 35 (87.5) | 31 (77.5) | ||

| Area of domicile, n (%) | ||||

| Urban | 9 (22.5) | 16 (40.0) | 2.85 | 0.14 |

| Rural | 31 (77.5) | 24 (60.0) | ||

| Total duration of illness (months), mean±SD | 31.48±46.84 | 34.06±54.25 | 0.22 | 0.82 |

| Current duration of illness (months), mean±SD | 1.83±1.62 | 1.86±1.17 | 0.11 | 0.90 |

| Episode number, mean±SD | 2.30±2.12 | 2.55±3.41 | 0.39 | 0.69 |

SD – Standard deviation

Table 2.

Comparison of fall in depression scores as measured by Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale across two groups (n=40 each group)

| Fall in MADRS | Group | Mean±SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to day 10 | Yoga | 12.98±5.28 | 0.765 |

| Control | 12.60±5.87 | ||

| Day 10 to day 30 | Yoga | 11.45±6.08 | 0.047* |

| Control | 9.10±4.08 | ||

| Baseline to day 30 | Yoga | 24.43±7.78 | 0.042* |

| Control | 21.70±7.35 |

*P<0.05. MADRS – Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; SD – Standard deviation

Figure 1.

Comparison of fall in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety scores across two groups at baseline, 10th day, and 30th day (n = 40 each group)

Figure 2.

Comparison of fall in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression Scores across two groups at baseline, 10th day, and 30th day (n = 40 each group)

Figure 3.

Improvement in the Clinical Global Impression across two groups at baseline and 30th day (n = 40 each group)

DISCUSSION

This is a longitudinal observational randomized study conducted in a tertiary care center to find the effect of adjunct yoga therapy in patients diagnosed with MDD, according to DSM-5.

The study by Naveen et al.[13] on antidepressant and cortisol effects of yoga divided individuals into three groups, yoga therapy, yoga along with antidepressants, and antidepressant alone, based on the patient preferences and not by randomization methods like in our study.

The study on the effect of yoga therapy in individuals with MDD[14] included a yoga group and a control group which were nonrandomized. They have also used DSM-IV as the inclusion criteria for MDD unlike our study which uses DSM-5, a more revised and currently widely used version, as the criteria for including patients with depressive disorders.

In a randomized study on the influence of exercise and yoga in depression for 12 weeks,[15] MADRS was applied at the baseline and the end of the study. The results showing a significant fall in MADRS score at the 12th week in the yoga group were similar in comparison to our study which also had a significant fall in depressive scores at the 30th day. Our study shows improvement after 30 days and not on 10th day which implies that adjunct yoga is required for a longer period for improvement of depressive symptoms which is also similar to this study where a 12-week period has produced an improvement. This focuses on the fact that short-term yoga therapy might not help in alleviating depression and the necessity for a longer duration of yoga therapy in depressive disorders. Although the MADRS is widely used as a rating scale for depression, it was applied only in a limited amount of studies involving yoga and depression. We used both rating scales for depression, i.e., HADS and MADRS and this study brought out the concordance of MADRS scores with HADS.

A cross-sectional study on the impact of yoga in depressive and anxiety scores in patients with chronic illness was conducted for 7 days and was rated by HADS-A and HADS-D at baseline and end of the study. The results showed that short sessions of yoga have caused a reduction in anxiety scores while long-term yoga therapy was able to produce a reduction in depressive scores. Our findings correspond with this study results which also had a reduction in anxiety scores at shorter sessions of yoga than the depressive scores which required longer term yoga therapy.[16] This improvement in anxiety is noticed early presumably because the practice of yoga is essentially targeted at calming the nerves and mind which ultimately helps in stress reduction. It is also known for correcting and regulating imbalances of the autonomic nervous system associated with sympathetic hyperactivity. This may explain why yoga practices, even for shorter duration might help in the reduction of anxiety. Meanwhile, in depression, due to the synaptic level changes the reduction in the depression scores with adjunct yoga therapy may take a longer duration.[17]

Our study included individuals who were admitted as in-patients, by which a close observation was ensured and was provided bedside yoga sessions under the constant supervision of a certified yoga therapist. Patients who were discharged before the end of the study period were trained and emphasized to continue yoga sessions at home which were periodically checked using personal log entries, along with mandatory two supervised yoga sessions in a week on an outpatient basis. This helped in ensuring a prospective follow-up study design.

A randomized controlled study on Iyengar yoga in depression also had longer yoga sessions (12 weeks), but the supervised yoga sessions were less and the focus was more on home-based training.[17] These nonsupervised sessions in such studies might have the possibility of the individuals not conforming to the appropriate postures/techniques resulting in reduced efficiency and the adherence to the daily yoga practice was also not monitored during the follow-up. In this aspect, our study ensured increased adherence to yoga sessions during the study, and hence, the results may be considered more reliable.

The individuals receiving yoga sessions were not confined to a particular type of yoga and were personalized according to every subject based on their preferences, limitations, and also after careful assessment by the certified yoga therapist. Participants practiced a yoga therapy protocol that was specially designed for patients of depression, keeping in mind their general health status, and various physical limitations. This included simple warm-up and breath body movement coordination practices (jathis and kriyas), static stretching postures (asanas), breathing techniques (pranayamas), and relaxation. The postures included tala asana (a vertical spinal stretch done from standing), ardhakati chakra asana (a lateral spinal stretch done from standing), and kati chakra asana (torso twist to right and left) done in tune with the breathing rate of 6–8/min and one to three rounds on each side depending on their ability. Sitting postures included vakra asana (seated spinal twist), paschimottana asana (posterior stretch done by bending forward from sitting with hands clasping extended feet), and purvottana asana (anterior stretch from sitting with arms behind the back and feet extended forward). All of these were done with breath-body synchronization and the extent of the effort in the practice was determined by the ability of the individual. The key element was to make their best effort but not focus on trying to be “perfect” in the postures. Breath awareness was done in each session and pranayamas (energy-enhancing breathing techniques) included nadi shuddhi (alternate nostril breathing), vyagraha pranayama (slow deep breathing done on all fours with gentle spinal extension and flexion), and pranava pranayama (deep breathing with production of audible sounds of AAA, UUU, MMM, and AUM on the prolonged exhalation). Each session ended with relaxation for 10 min in the supine shava asana with mindful relaxation of the body parts from toes to top of the head.[13] However, the core practice of yoga used for all patients in the active group is generally similar but with some adaptations suitable for the individual.

There are some studies which involve only a particular type of yoga, like the study on the effectiveness of Kirtan Kriya in depressive disorders among the caregivers of dementia patients,[18] the study on the influence of Iyengar yoga in depressive symptoms among young adults.[19] A study on the effectiveness of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga in melancholic depression,[20] a critical review of the role of hatha yoga in depression,[21] the effect of Sahaj yoga and Shavasana in MDD respectively.[22,23] Similarly, study on the effect of laughter yoga and serum cortisol levels[24] and role of Kundalini yoga as an adjunct treatment in depression and anxiety in Indian studies.[25,26] Our study is unique in personalizing the type of yoga therapy tailored to the individual's requirements and not generalizing a single type of yoga as being done in other similar studies.

Our study was more focused on the change in the psychopathology of the individuals and was rated with MADRS, HADS, and CGI scale. In our study, in addition to the MADRS and HADS, the CGI scale was also applied at baseline and at the 30th day to assess the clinical change in the individuals with adjunct yoga therapy.

Limitations

The time spent by the therapist with the yoga group was clearly more than the other groups, and this is a confounding variable possibly (though unlikely in view of the previous studies and observations which have pointed to the benefits of yoga over placebo) responsible for the benefits. In addition, we did not anticipate this while designing the study. Furthermore, we do not have a strict yoga protocol for depression, and thus, there is a lack of standardization of the treatment received in the yoga group.

CONCLUSION

In our randomized controlled study to find the effect of adjunctive yoga therapy in the treatment of depressive disorders, we found that the individuals in the yoga group had a significantly higher fall in depression and anxiety scores, compared to the control group. They also showed a significant clinical improvement (based on the CGI), compared to control group, at 30th day. It implies that long-term yoga therapy is likely to be beneficial in the treatment of depression, while comorbid anxiety starts to improve with shorter sessions. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution, in view of the short follow-up period, lack of blinding, and a small sample size. Further research is needed to study the effect of adjunctive yoga therapy in the outcome of depressive disorders with a larger sample and longer follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Dr. G. Ezumalai, Senior Statistician, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College, and Research Institute, for his help in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association, editors. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. p. 947. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Depression and other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. World Health Organization; 2017. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 05]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belmaker RH, Agam G. Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:55–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P, Lange S, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ. Yoga for improving health-related quality of life, mental health and cancer-related symptoms in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD010802. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010802.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. Yoga for depression: The research evidence. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer S, Macare C, Cleare AJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis functioning as predictor of antidepressant response-meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:200–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayaram N, Varambally S, Behere RV, Venkatasubramanian G, Arasappa R, Christopher R, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on plasma oxytocin and facial emotion recognition deficits in patients of schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:S409–13. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.116318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalsa SB, Cohen L, McCall T, Telles S. The principles and practice of yoga in health care. Int J Yoga. 2018;11:86–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naveen GH, Rao MG, Vishal V, Thirthalli J, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN, et al. Development and feasibility of yoga therapy module for out-patients with depression in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:S350–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.116305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naveen GH, Varambally S, Thirthalli J, Rao M, Christopher R, Gangadhar BN. Serum cortisol and BDNF in patients with major depression-effect of yoga. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:273–8. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2016.1175419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helgadóttir B, Hallgren M, Ekblom Ö, Forsell Y. Training fast or slow. Exercise for depression: A randomized controlled trial? Prev Med. 2016;91:123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Telles S, Pathak S, Kumar A, Mishra P, Balkrishna A. Influence of intensity and duration of yoga on anxiety and depression scores associated with chronic illness. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5:260–5. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.160182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satyapriya M, Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V. Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104:218–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavretsky H, Epel ES, Siddarth P, Nazarian N, Cyr NS, Khalsa DS, et al. A pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: Effects on mental health, cognition, and telomerase activity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:57–65. doi: 10.1002/gps.3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolery A, Myers H, Sternlieb B, Zeltzer L. A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:60–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN, Naga Venkatesha Murthy PJ, Harish MG, Subbakrishna DK, Vedamurthachar A. Antidepressant efficacy of sudarshan kriya yoga (SKY) in melancholia: A randomized comparison with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and imipramine. J Affect Disord. 2000;57:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uebelacker LA, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Tremont G, Battle CL, Miller IW. Hatha yoga for depression: Critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16:22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma VK, Das S, Mondal S, Goswampi U, Gandhi A. Effect of Sahaj yoga on depressive disorders. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;49:462–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khumar SS, Kaur P, Kaur S. Effectiveness of Shavasana on depression among university students. Indian J Clin Psychol. 1993;20:82–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujisawa A, Ota A, Matsunaga M, Li Y, Kakizaki M, Naito H, et al. Effect of laughter yoga on salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone among healthy university students: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;32:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devi SK, Chansauria JP, Udupa KN. Mental depression and Kundalini yoga. Anc Sci Life. 1986;6:112–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Tuffrey V, Richardson J, Pilkington K. Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review of the research evidence. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:884–91. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]