Abstract

Objective

To evaluate real-world use and outcomes of apatinib treatment in platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Methods

This is an observational study. Patients with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer initiating apatinib treatment from January 2016 to December 2018 were included. The primary end point was progression-free survival. Other end points included overall survival, objective response rate, disease control rate, and toxicity.

Results

A total of 28 platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer patients were enrolled in this study. Thirteen cases received apatinib as maintenance therapy following chemotherapy with a median progression-free survival of 6.0 months and a medium overall survival of 11.0 months. Four patients received apatinib as palliative following chemotherapy with 2 cases in progressive disease and 2 cases in stable disease. Eleven cases received apatinib alone as salvage therapy with a disease control rate of 81.8% and a median progression-free survival of 3.0 months. The most common adverse effects were hand-foot syndrome (53.57%), secondary hypertension (46.43%) and fatigue (14.29%). Five patients discontinued treatment due to grade 3 toxicities and 4 patients required dose reduction because of adverse effects.

Conclusion

Apatinib produced moderate improvements in progression-free survival in patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer both as maintenance therapy following chemotherapy and as single-agent salvage therapy. Our study suggests that apatinib may be effective for women with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, apatinib, ovarian cancer, platinum-resistant, maintenance therapy

Introduction

Throughout the world, there are approximately 238,700 new cases of ovarian cancer each year and 151,900 deaths.1 Cytoreductive surgical debulking accompanied by platinum-based chemotherapy has been established as the standard treatment for the epithelial ovarian cancer.2 Unfortunately, approximately 20–30% of patients will relapse or progress within 6 months of completing chemotherapy. These patients were defined as platinum-resistant and were associated with a poor median survival of 12–18 months.3 Clinically, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients have poor responses to alternative single-agent chemotherapy, thus, it is urgent to discover novel active drugs against this recurrent disease.

Apatinib is an oral, highly potent tyrosine-kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2).4 Previous phase II clinical trials have shown its efficacy and safety in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.5 Besides, the combination of apatinib with oral etoposide was reported promising efficacy and manageable toxicities among patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ovarian cancer in phase II, single-arm, prospective study.6 However, the effective treatment of apatinib among platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer in the real world is still unclear. This observation study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of apatinib among patients with platinum-resistant disease in the real world to get more clinical evidence.

Methods

Patients

Detailed clinicopathological information and follow-up records were collected from platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer patients who received apatinib treatment between January 2015 and November 2018 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Only patients who had finished at least one cycle (four weeks) apatinib therapy and evaluated the efficacy were included in this study. Totally, there were 28 patients enrolled in this study. All the 28 patients were pathologically confirmed as ovarian cancer. The last following-up date was March 2019. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Informed consents were obtained from each patient before the initiation of the study. The patient consent was written informed consent.

Treatment

Apatinib was provided as tablets and administered orally at 250 or 500mg daily. The dosage of the apatinib was determined by the attending physician based on the patients’ age, body weight, general status and tolerance. Performance status, blood pressure, complete blood count, urine, liver and kidney function were monitored during the treatment. Four weeks were defined as one cycle.

Efficacy And Safety Assessments

Treatment responses were assessed by investigators using the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST)7 or CA-125 levels according to modified Rustin criteria,8 including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). According to modified Rustin criteria, complete response was defined as normalization of CA-125 levels from an elevated level. Partial response was defined as a 50% reduction in CA-125. Progressive disease was defined as a doubling of CA-125 within eight weeks of starting therapy. Stable disease was any of the conditions that did not meet the above criteria. Objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the proportion of eligible patients who achieved a confirmed complete response or partial response. Disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved complete response, partial response and stable disease for at least 8 weeks. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from initiation of apatinib to the date of disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from initiation of apatinib to death or the last follow-up visit.

Apatinib-related toxicities were evaluated and graded according to the National Cancer Institute. Toxicities were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).9

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS version 24.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL). Continuous data were expressed as the median (range) and categorical variables were presented as percentages. Median progression-free survival and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 28 patients with epithelia ovarian cancer were included in this observation study. Patient characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis of recurrence was 59 years (range=43–75 years). All the 28 patients were pathologically confirmed as epithelial ovarian cancer. Documented recurrence was further confirmed, and, all the included cases had platinum-resistant recurrent disease. All patients were diagnosed with advanced-stage disease (stage III: n=18; stage IV: n=10). The majority of women were grade III (n = 22, 78.6%), followed by grade II (n = 5, 17.9%). The median number of previous regimens was 3.5 (range = 2–7), in particular, 78.6% of patients had received ≥3 previous lines, and 21.4% of patients had received ≥5 prior treatments before apatinib was administered.

Table 1.

The Baseline Patients’ Characteristics

| Characteristics | Results (n) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59 (43–75) |

| FIGO Stage | |

| IIIA | 2 |

| IIIB | 1 |

| IIIC | 15 |

| IV | 10 |

| Differentiation | |

| I | 1 |

| II | 5 |

| III | 22 |

| Cytoreductive surgery | |

| Optimal | 11 |

| Suboptimal | 15 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens | |

| 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 8 |

| ≥3 | 14 |

| Dose reduction | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 24 |

Abbreviation: n, number of patients.

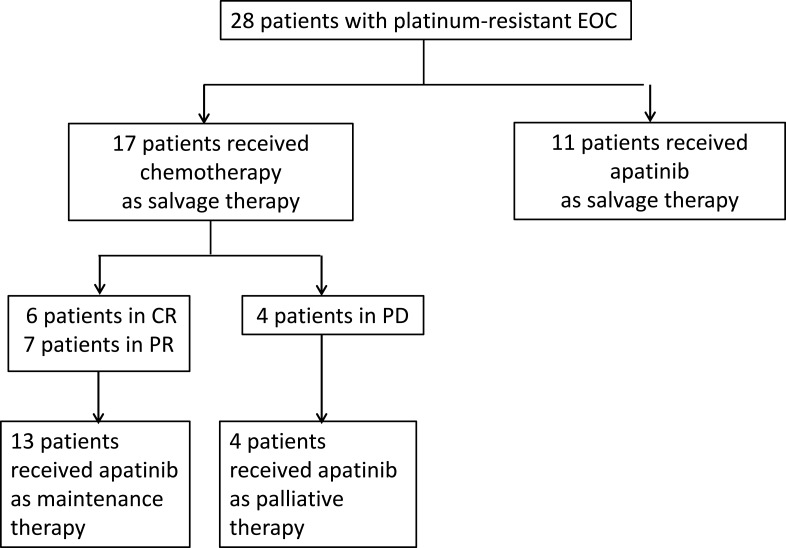

Initially, 17 patients received chemotherapy as salvage therapy as a diagnosis of recurrent ovarian cancer. Of which, 13 cases were in objective response (either complete response or partial response) and then administrated apatinib as maintenance therapy following chemotherapy. Another 4 cases were in progressive disease after chemotherapy, and then administrated apatinib as palliative therapy. In addition, there are 11 cases who rejected any kind of chemotherapy and administrated apatinib alone as salvage therapy as the diagnosis of recurrent ovarian cancer. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Abbreviations: EOC, epithelial ovarian cancer; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease.

Briefly, 13 cases received apatinib as maintenance following chemotherapy, 4 patients received apatinib as palliative following chemotherapy, and 11 cases received apatinib as salvage without chemotherapy. None of the patients received other anti-epidermal growth factor receptor drugs and radiotherapy.

Safety

All patients experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse event, with 5 patients (17.9%) experiencing adverse events of grade 3–4 (Table 2). Eight patients (28.6%) started from 500 mg daily, in which 4 patients experienced dose reduction to 250mg because of intolerable toxicity, and the other 20 patients (71.4%) started from a dose of 250mg daily. Five (17.9%) of the 28 patients discontinued because of intolerable adverse events, including hypertension (2 cases;7.1%), thrombocytopenia (3 cases; 10.7%).

Table 2.

Treatment-Related Toxicities

| Adverse Event | Grade1 n | Grade2 n | Grade3 n | Grade4 n | Total n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand and foot syndrome | 9 | 6 | 53.57 | ||

| Secondary hypertension | 8 | 3 | 2 | 46.43 | |

| Fatigue | 2 | 2 | 14.29 | ||

| Anorexia | 1 | 3.57 | |||

| Neutropenia | 2 | 7.14 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 10.71 | |||

| Diarrhea | 3 | 10.71 | |||

| Liver dysfunction | 1 | 3.57 | |||

| Nausea | 1 | 3.57 |

Abbreviation: n, number of patients.

The most common adverse events were hand and foot syndrome (n=15; 53.6%), secondary hypertension (n=13; 46.4%), fatigue (n=4; 14.3%), thrombocytopenia (n=3; 10.7%) and diarrhea (n=3; 10.7%). Other rare side effects were anorexia, neutropenia, nausea, and liver dysfunction, mainly as grade 1 to 2. (Table 2)

Efficacy

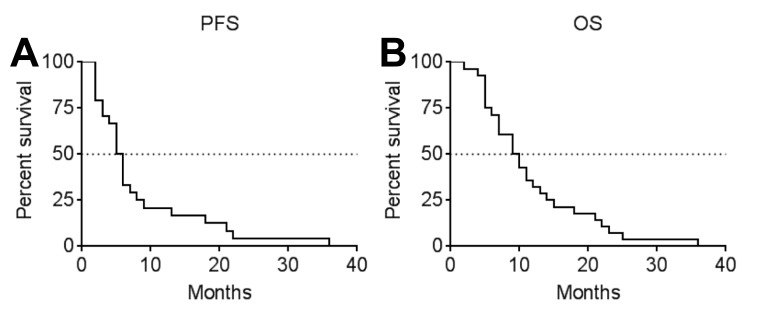

Median follow-up time was 9.5 months (range, 3.0 to 36.0 months) and 13 of 28 patients were dead. Median progression-free survival and overall survival were 5.0 (range=2.0–36.0) and 9.5 (range=3.0–36.0) months, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS (A) and OS (B) of 28 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer after apatinib treatment.

Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; OS, Overall survival.

Apatinib As Maintenance Therapy Following Chemotherapy

Totally, 13 cases administrated apatinib as maintenance therapy following chemotherapy. The median follow-up for progression-free survival was 6.0(2.0–22.0) months and overall survival was 11.0(5.0–25.0) months.

Apatinib As Palliative Therapy Following Chemotherapy

Four cases were in progressive disease after received chemotherapy as salvage therapy. Then, these four patients administrated apatinib as palliative therapy. Clinical response rates to palliative apatinib were as follows: 2 cases in progressive disease, and 2 cases in stable disease with a progression-free survival of 2.0 months and 5.0 months, respectively.

Apatinib Alone As Salvage Therapy Without Chemotherapy

There were 11 cases who rejected any kind of chemotherapy and administrated apatinib alone as salvage therapy. The median progression-free survival was 3.0 (2.0–36.0) months and the median overall survival was 10.0 (3.0–36.0) months.

Among these 11 patients, 2 cases were a partial response but none of the complete response had been registered. In addition, seven patients had stable disease (63.6%) and 2 had progressive disease (18.2%). Thus, the overall response rate (complete response plus partial response) was 18.2%, and the disease control rate (complete response plus partial response plus stable disease) was 81.8%. Additionally, median disease control duration was 3.0 months (range=2.0–36.0). Notably, one patient was in stable disease with a progression-free survival of 36.0 months.

Discussion

Angiogenesis plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of ovarian cancer via ascites formation and metastatic spread.10 Thus, anti-angiogenesis represents a promising approach for patients with ovarian cancer. Bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor (VEGF), was the first and the only anti-angiogenesis agent in routine clinical practice.11 This targeted agent has become an important agent in conjunction with chemotherapy and as a single agent for primary or recurrent ovarian disease.10 The AURELIA (Avastin Use in Platinum-Resistant Epithelial Ovarian Cancer) trial, a Phase III data providing the most meaningful statistical bar, demonstrated an increase of 3.3 months in progression-free survival and 15.5% in objective response rate with the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy alone in a platinum-resistant population.12 Unfortunately, the associated toxicity, intravenous administration and the cost-effectiveness of bevacizumab have created much controversy. Other antiangiogenics, such as cediranib or sorafenib, have been evaluated in ovarian cancer, however, all with modest-to-moderate activity in progression-free survival.13,14

Apatinib is an oral, highly potent tyrosine-kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2(VEGFR-2).4 A recent pre-clinical study demonstrated that apatinib significantly inhibited ovarian tumor growth via inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a mouse xenograft model.15 Previous clinical trials have reported that the combination of apatinib with oral etoposide showed a significant improvement in progression-free survival (8.1 months) in patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ovarian cancer.6 In the current study, we retrospectively evaluated the effectiveness of apatinib among 28 women with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer in the real world. Our results showed that orally-taken apatinib may compare favorably to bevacizumab with a median progression-free survival of 5.0 months and overall survival of 9.5 months among platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer.

Initially, we evaluated the role of apatinib as maintenance therapy following chemotherapy among 13 platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer patients. Actually, the use of anti-VEGF as maintenance following salvage therapy among patients with ovarian cancer has been reported by others in both prospective and retrospective studies. In the OCEANS trial, a Phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer, gemcitabine and carboplatin plus bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab maintenance until progression resulted in a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (12.4 vs 8.4 months) compared with chemotherapy alone.16 Similar results were reported in ICON 7 and GOG 218, both trials demonstrated significant improvements in progression-free survival in the intent-to-treat ovarian cancer populations with concurrent and maintenance bevacizumab.17,18 In GOG 218 trail, the use of bevacizumab during and up to 10.0 months after carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy prolongs the median progression-free survival by about 4.0 months in patients with advanced ovarian cancer.18 However, a primary disadvantage to bevacizumab as maintenance therapy is its intravenous administration. More recently, Jin et al reported one case with platinum-resistant advanced ovarian cancer took apatinib orally as maintenance therapy following apatinib plus epirubicin.19 The treatment of apatinib plus epirubicin lasted for 6.0 months, and then continued using aptinib as maintenance therapy for 6.6 months.19 In the current study, oral apatinib as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer led to a moderate median progression-free survival of 6.0 months.

Additionally, this study reports the clinical outcomes for 11 patients with platinum-resistant relapsed ovarian cancer who received apatinib alone. We found that single-agent apatinib was active (disease control) up to 81.8% of the individuals. The median progression-free survival and overall survival after single apatinib therapy were 3.0 and 10.0 months, respectively. The pivotal study that assessed the role of single-agent bevacizumab in recurrent ovarian cancer patients is the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) protocol 170-D.20 In GOG 170-D, overall clinical response rates and disease control rates were documented in 13 patients (21.0%) and 25 patients (40.3%) respectively with a median progression-free survival of 4.7 months and a medium overall survival of 17 months.20 Another clinical trial reported a median progression-free survival of 4.4 months and a median overall survival of 10.7 months by single-agent bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer.21 With respect to apatinib, there is only one study evaluated single-agent apatinib in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer. Tang et al5 reported a disease control rate of 68.9%, a median progression-free survival of 5.1 months, and a median overall survival of 14.5 months among 29 patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant, pre-treated ovarian cancer who failed available standard chemotherapy. This finding, which is in line with results from our study, suggests that single-agent apatinib orally taken was compared favorably to bevacizumab intravenous administration in treating patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Finally, our study observed four cases administrated apatinib as palliative therapy who presented progressive disease on chemotherapy salvage therapy. However, the result was disappointing and the majority of cases showed progressive diseases.

Hypertension, proteinuria, and hand-foot syndrome are reported to the most common adverse events related to anti-angiogenic agents.22 Consistent with the safety profile of apatinib-containing therapy in previously reported trials in ovarian cancer and other tumor types, our current study showed the most frequently observed side effects were the hand-foot syndrome, hypertension and fatigue.5,23 In addition, no new safety concerns were observed in this patient population with recurrent ovarian cancer. Overall, in the current study, apatinib by a dosage of 250–500 mg daily is tolerable.

Overall, apatinib showed moderate improvements in progression-free survival in patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer both as maintenance therapy following chemotherapy and as single-agent salvage therapy. Thus, apatinib, an oral and economic novel anti-EFGR agent, may be effective for women with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation (LY19H160021), Zhejiang Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Plan (2019ZA074) and Technology Development Funds of Wenzhou City (Y20180014).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943–953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer: evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019. doi: 10.3322/caac.21559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding J, Chen X, Gao Z, et al. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of novel selective vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibitor apatinib in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:1195–1210. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.050310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miao M, Deng G, Luo S, et al. A phase II study of apatinib in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lan CY, Wang Y, Xiong Y, et al. Apatinib combined with oral etoposide in patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ovarian cancer (AEROC): a phase 2, single-arm, prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30349-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guppy AE, Rustin GJ. CA125 response: can it replace the traditional response criteria in ovarian cancer? Oncologist. 2002;7:437–443. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-5-437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monk BJ, Minion LE, Coleman RL. Anti-angiogenic agents in ovarian cancer: past, present, and future. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl 1):i33–i9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Shen Z, Luo H, et al. The benefits and side effects of bevacizumab for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18:1125–1131. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666160502150237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: the AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1302–1308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodnar L, Gornas M, Szczylik C. Sorafenib as a third line therapy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: a phase II study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orbegoso C, Marquina G, George A, et al. The role of Cediranib in ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:1637–1648. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1383384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding J, Cheng XY, Liu S, et al. Apatinib exerts anti-tumour effects on ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2039–2045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin M, Cai J, Wang X, et al. Successful maintenance therapy with apatinib inplatinum-resistant advanced ovarian cancer and literature review. Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burger RA, Sill MW, Monk BJ, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5165–5171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannistra SA, Matulonis UA, Penson RT, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer or peritoneal serous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5180–5186. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidinger M. Understanding and managing toxicities of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors. EJC Suppl. 2013;11:172–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu X, Cao J, Hu W, et al. Multicenter phase II study of apatinib in non-triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:820. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]