Abstract

Reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke significantly reduces lung cancer risk. We used family communication patterns theory and the theory of planned behavior to examine whether perceived norms and lung cancer worry more strongly influenced intentions to avoid environmental tobacco smoke in families higher in conformity and conversation orientations. Results from 52 individuals in 17 high-risk lung cancer families showed injunctive norms were positively related to intentions when families conformed and conversed more. Lung cancer worry was positively related to intentions in high conformity families and negatively related to intentions in low conformity families. Findings can benefit interventions to reduce environmental tobacco smoke exposure.

Keywords: cancer, family, high-risk families, second-hand smoke, smoking, smoking cessation, theory of planned behavior

The direct association of tobacco smoking with lung disease and lung cancer (LC) risk is well established—approximately 90 percent of LC in men and 80 percent in women are directly attributable to smoking (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). However, environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure and familial aggregation of LC have garnered significant attention as additional important LC risk factors. Specifically, evidence indicates that exposure to ETS (i.e. second-hand smoke) is an additional independent LC risk factor (Asomaning et al., 2008; Besaratinia and Pfeifer, 2008; Dockery and Trichopoulos, 1997; Fontham et al., 1994; Lo et al., 2013; Oberg et al., 2011; Vineis et al., 2007). Evidence also indicates that first-degree relatives of individuals with LC are themselves at increased risk of LC (Coté et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2009; Lo et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 1996, 2007). Since ETS exposure may be an independent risk factor when controlling for familial aggregation of LC (Lo et al., 2013), avoiding exposure to ETS among individuals from “high-risk” families could significantly reduce their LC risk, and also reduce morbidity and mortality from other causes (Hagstad et al., 2013; Oberg et al., 2011). The purpose of this exploratory study is to examine the extent to which perceptions of behavioral norms and communication patterns among high-risk LC families influence their behavioral decision-making when it comes to avoiding exposure to ETS.

An individual’s health behaviors can be directly influenced by the norms, beliefs, and values shared by that individual’s family. Research shows that families influence individuals’ health behavior directly through modeling of healthy and unhealthy behaviors (Engels and Willemsen, 2004; Fearnow et al., 1998; Lau et al., 1990) and indirectly through shared health beliefs, values, and behavioral norms (Manne et al., 2012; Quadrel and Lau, 1990). These familial influences hold true for smoking behaviors too, in that smoking tends to be concordant within families. For example, spouses influence each other’s smoking behaviors (Franks et al., 2002), and parents’ smoking behaviors influence the smoking behaviors of their children (Kandel and Wu, 1995; Wickrama et al., 1999). It is likely that similar familial influences exist for behaviors related to avoiding ETS as well, especially among high-risk families for whom issues related to tobacco smoke and LC may be more salient. However, the extent to which families’ norms and beliefs influence individuals’ ETS behavioral decision-making could be determined, in part, by how family members interact with and relate to each other.

The family communication patterns theory (FCPT; Koerner and Fitzpatrick, 2006; Ritchie and Fitzpatrick, 1990) addresses how family members communicate with each other to create a shared social reality that facilitates family functioning. The theory places beliefs about and perceptions of family relations at the heart of interpersonal communication and information processing in the family context. FCPT posits that relational interactions occur within families along two dimensions: conversation and conformity orientation. Families high in conversation orientation encourage each other to communicate frequently and discuss a wide range of topics, whereas families low in conversation orientation interact less frequently and discuss a narrower range of topics. Prior studies indicate that conversations with parents can be a protective factor against smoking among adolescents (Miller-Day, 2002; White, 2012), but that more frequent and ineffective conversations about smoking can be associated with more smoking among adolescents (De Leeuw et al., 2010). For individuals from high-risk LC families that are higher in conversation orientation, we would expect more frequent discussions to clarify shared norms and beliefs related to avoiding ETS. Therefore, compared to individuals from low conversation orientation families, these norms and beliefs should be more salient among individuals from high conversation orientation families and thus have a stronger influence on relevant behavioral decision-making (Ajzen, 1991). Families high in conformity orientation encourage homogeneity of attitudes and beliefs, whereas families low in conformity orientation encourage more individuality and variability in attitudes and beliefs. Since attitudes and beliefs are ultimately related to behaviors (Ajzen, 1991, 2011), we expect behaviors to also be more concordant in high conformity families. Hence, data showing that adolescents whose parents smoke are more likely to overestimate smoking prevalence, which directly contributes to their own smoking (Otten et al., 2009), individuals are likely to report supportive family environments that helped to initiate their smoking behaviors (Alexander et al., 1999), and that when parents smoke, their children are more likely to smoke regardless of parental disapproval (Musick et al., 2008). For high-risk LC families who are higher in conformity, we would expect that family members have greater awareness of and adherence to family norms and beliefs related to avoiding ETS; therefore, we expect norms and values to have stronger influences on behavioral decision-making among individuals from high conformity families compared to individuals from low conformity families. We test these hypotheses by incorporating measures of families’ conversation and conformity orientation in a model of behavioral decision-making regarding avoiding ETS.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991, 2011) is a cognitive-process model that relates behavior-relevant beliefs to actual behavioral engagement via attitudinal, normative and control perceptions, and behavioral intentions. Using this well-validated behavioral decision-making model allows a parsimonious examination of our hypotheses while accounting for acknowledged theoretically important predictors of behaviors and behavioral intentions. The TPB proposes that behavioral intentions are the most proximal predictors of behavioral engagement. Behavioral intentions in turn are a function of attitude toward the behavior, normative behavioral perceptions, and perceptions of behavioral control. In short, more favorable attitudes, normative perceptions, and perceptions of control lead to more favorable intentions to engage in a particular behavior, which in turn increase the probability of eventual behavioral engagement.

TPB has been successfully utilized to examine various health behaviors (Albarracin et al., 2001; Conner et al., 2002; Povey et al., 2000; Sheeran et al., 2001; Sheeran and Taylor, 1999). Research shows that the model accounts for significant variance in intentions and behaviors related to smoking (McMillan and Conner, 2003; McMillan et al., 2005; O’Callaghan et al., 1999) and smoking cessation (Moan and Rise, 2005, 2006); in each of those studies, normative perceptions were significant predictors of behavioral intentions. In this study, we use the TPB to examine how family communication influences the relationship between norms and intentions to avoid ETS. We chose to apply TPB in this context given that we can assess the unique effects of normative perceptions of avoiding ETS, and the proposed moderations by conformity and conversation orientation, while controlling for the theoretically important effects of attitudes and perceptions of control related to avoiding ETS.

We also examine the association between LC worry and intentions to avoid ETS. Evidence indicates that when relatives of LC patients worried more, they were more likely to consider quitting smoking (McBride et al., 2003). While we did not find any direct evidence in the literature regarding LC worry and avoiding ETS, we conjecture that the association would be similar. To the extent that an individual’s LC worry influences her or his LC prevention behaviors, the extent to which a family worries about LC will have an additional effect on LC prevention behaviors, especially among high LC risk families. In other words, when controlling for people’s individual LC worry, the extent to which their families worry about LC as a unit will uniquely influence their individual intentions to avoid ETS. We further propose that the influence of families’ LC worry will be moderated by each family’s communication patterns. Among families with more conversation, family-level LC worry has more opportunities (ostensibly via more conversations) to influence individuals’ ETS intentions compared to families with less conversation. Among families with higher conformity, commonalities in behavioral intentions to avoid ETS would likely be related to family-level LC worry, whereas for families with lower conformity, less commonality in behavioral intentions should yield less robust relationships with family-level LC worry.

For the current exploratory study, we used the TPB framework to examine how norms and LC worry predict individuals’ intentions to avoid ETS among families at high risk for LC (i.e. those with first-degree relatives with LC). We examined whether normative perceptions had a stronger influence on behavioral intentions when families were higher in conversation orientation and, separately, when families were higher in conformity orientation. We also examined whether the unique effect of family-level LC worry on individuals’ behavioral intentions was stronger among families higher in conversation orientation and, separately, among families higher in conformity orientation when controlling for individual-level LC worry.

Method

Participants

We initially mailed invitations to 139 potential participants who had previously taken part in a Genetic Epidemiology of Lung Cancer (GELC) study and who provided permission to be contacted for future research projects. Participants were recruited to the GELC study if they had a family history of at least two biologically related individuals with LC. The letter invited participants to take part in a 30-minute online survey about their attitudes and their families’ attitudes about health and preventing LC. In all, 58 individuals (49%) consented to participate. There were no significant differences in age, race, or gender between those who participated and those who declined. Survey participants were asked to provide contact information for up to 15 family members who could be recruited into the study. We garnered contact information for 130 individuals, 17 (13%) of who consented to participate—as we had no data on invitees who declined to participate, we were precluded from testing whether there were any significant demographic differences. As an incentive, all respondents received a US$15 gift card for their time. In all, 75 individuals responded—one individual’s data were not used as it could not be matched to a family; one individual neglected to respond to planned behavior items, but responded to all other items and was retained for analysis. Of those 74 individuals, we used 52 responses from related individuals (i.e. >1 person from the same family completed survey) for analyses. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Measures

Theory of planned behavior.

We assessed participants’ intentions to avoid ETS with responses to two items: participants indicated how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the statement “I definitely plan to avoid second-hand smoke over the next month” on a scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree), and they indicated how likely or unlikely they were to avoid second-hand smoke over the next month on a scale from 1 (Extremely unlikely) to 7 (Very likely). To assess affective attitudes participants responded to the item, “For me to avoid second-hand smoke over the next month is …” from 1 (Extremely good) to 7 (Extremely bad). To assess instrumental attitudes, participants responded to the same item on a scale from 1 (Extremely worthwhile) to 7 (Not at all worthwhile). We assessed injunctive norms with the responses to the items: “Most people who are important to me think I should avoid second-hand smoke over the next month” and “Most people who are important to me would support me avoiding second-hand smoke over the next month.” We assessed descriptive norms with responses to the items “Most people who I care about would avoid second-hand smoke over the next month,” and “Most people who are important to me would avoid second-hand smoke over the next month.” We assessed perceived behavioral control (PBC) with responses to the item, “For me to avoid second-hand smoke over the next month would be …” from 1 (Extremely possible) to 7 (Extremely impossible).

Family communication patterns.

To assess how family members perceived communication within their own family, we adapted the 26-item Revised Family Communication Patterns Scale (Ritchie and Fitzpatrick, 1990). We framed the items so that participants responded regarding perceptions of family members. For example, one item used to assess conformity orientation was “I really enjoy talking with my family members, even when we disagree” (in contrast to the original item, “I really enjoy talking with my parents, even when we disagree”). Examples of items used to assess conversation orientation include “My family members encourage me to express my feelings” and “I can tell my family members almost anything.” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree) for all items. Scale reliabilities for both conformity (α = 0.80) and conversation orientations (α = 0.93) were high.

LC worry.

The extent to which participants worry about LC was measured by a single item: “How often do you worry about lung cancer?” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Almost all the time).

Demographic data.

We assessed each participant’s age, gender, racial group membership, household income, and education level with close-ended/forced choice items (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample demographic description.

| M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.98 | 13.73 | 21 | 78 |

| Number of family members | 3.46 | 1.28 | 2 | 6 |

| Categories | Frequency | Percentagea |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| African American | 3 | 5.8 |

| Caucasian American | 49 | 94.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13 | 36.1 |

| Female | 23 | 63.9 |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 7 | 13.5 |

| Business or trade school | 4 | 7.7 |

| Some college | 12 | 23.1 |

| College degree | 12 | 23.1 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 17 | 32.7 |

| Household income | ||

| Less than US$9999 | 3 | 5.9 |

| US$10,000–US$19,999 | 3 | 5.9 |

| US$20,000–US$29,999 | 2 | 3.9 |

| US$30,000–US$39,999 | 6 | 11.8 |

| US$40,000–US$49,999 | 2 | 3.9 |

| US$50,000–US$59,999 | 5 | 9.8 |

| US$60,000–US$69,999 | 3 | 5.9 |

| US$70,000–US$79,999 | 4 | 7.8 |

| US$80,000–US$89,999 | 3 | 5.9 |

| US$90,000–US$99,999 | 4 | 7.8 |

| More than US$100,000 | 16 | 31.4 |

SD: standard deviation; GED: general education development.

Valid percentages given 16 and 1 participant non-response for gender and household income, respectively.

Data analysis

Family-level scores.

We modeled family-level conversation, conformity and LC worry, orientations using multilevel models (MLM) fit with hierarchical linear model (HLM) 7.0 (Raudenbush et al., 2010) under restricted maximum likelihood (RML). Individuals (N = 52) were nested within families (N = 17). Models were specified such that each outcome, Yij, was predicted by a sample mean γ00, family-level deviation from the mean u0j, and individual-level measurement error, rij (i.e. Yij = γ00 + u0j + rij). A family’s score for each outcome can be estimated as the sum of the sample mean and each family’s deviation from the sample mean (i.e. γ00 + u0j).

Family communication and normative perceptions.

To test whether family-level scores for conversation and conformity orientations influenced the associations between injunctive and descriptive norms and intentions, we fit an MLM under RML with intentions as the outcome predicted by the theoretical TPB variables at the individual level and conversation and conformity orientations at the family level. We included cross-level interactions between both injunctive and descriptive norms with conversation and conformity orientations. The individual-level (i.e. level 1) model had the following form

At the family level (i.e. level 2), we included main effects of conversation orientation and conformity orientation and included conversation and conformity orientations as predictors of the coefficients relating injunctive and descriptive norms to the outcome, thus specifying the cross-level interactions between normative perceptions and family communication patterns (FCPs). Based on preliminary analyses, we also specified unexplained variance in the PBC coefficient at the family level (u2j). The level-2 models had the following forms

Family communication and LC worry.

We tested whether family-level LC worry directly predicted intentions with an MLM fit under RML with intentions as the outcome. We controlled for planned behavior predictors of intentions and individual LC worry at the individual level (level 1). The level-1 model had the following form

We introduced main effects of LC worry, conversation orientation, and conformity orientation and interactions between LC worry and conversation, and LC worry and conformity at the family level (level 2) as predictors of the model intercept. We controlled for any moderating effect of FCPs on the relationship between individuals’ LC worry and intentions by including conversation and conformity orientations as cross-level predictors of the level-1 LC worry coefficient. To address multicollinearity between main effects and product terms, and to facilitate interpretation of interaction effects, variables at the family level were standardized before creating the product interaction terms. Based on preliminary analyses, we specified unexplained variance in the LC worry effect at the family level (u1j). The level-2 models took the following forms

Results

Our sample consisted of 35 women and 17 men with ages ranging from 21 to 78 years. The sample was overwhelmingly well-educated female Caucasian Americans with mean household income between US$60,000 and US$69,999 (mode was >US$100,000). Descriptive sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Examinations using t tests indicated that there were no significant differences for any of the study variables (i.e. TPB variables, FCP variables, and LC worry) between individuals who were included for analyses and those who were excluded. Means, standard deviation (SD), and zero-order correlations for planned behavior variables, FCP variables, and LC worry for the sample used for analyses are presented in Table 2. Overall, participants had favorable attitudes, normative perceptions, PBC, and intentions to avoid ETS. As expected, all TPB variables were positively correlated with each other (with the exception of PBC and descriptive norms), and all the TPB predictors were positively associated with intentions. Mean FCP conformity and conversation orientations were close to the midpoint of the scale, suggesting moderate levels of conformity and conversation; consistent with other studies (Koerner and Fitzpatrick, 2002), they were negatively correlated (r = −.36, p < .05). LC worry was significantly correlated with injunctive norms (r = .30, p < .05).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affective attitude | 6.47 | 1.29 | – | |||||||

| 2 | Instrumental attitude | 6.41 | 1.37 | 0.86** | – | ||||||

| 3 | Injunctive norms | 5.73 | 1.75 | 0.44** | 0.47** | – | |||||

| 4 | Descriptive norms | 5.39 | 1.65 | 0.37** | 0.47** | 0.50** | – | ||||

| 5 | PBC | 5.35 | 2.19 | 0.39** | 0.36* | 0.54** | 0.25 | – | |||

| 6 | Intention | 5.38 | 1.92 | 0.44** | 0.51** | 0.52** | 0.52** | 0.60** | – | ||

| 7 | LC worry | 2.48 | 1.09 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.30* | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.03 | – | |

| 8 | Conversation orientation | 4.77 | 1.19 | 0.24† | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.08 | – |

| 9 | Conformity orientation | 4.02 | 1.09 | 0.13 | 0.12 | −0.12 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.18 | −0.36** |

PBC: perceived behavioral control; LC: lung cancer; SD: standard deviation.

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .10.

Family-level score

Family-level scores for LC worry, conversation, and conformity orientations are presented in Table 3. The results indicated that the mean for each score (fixed effects: γ00) was roughly at the midpoint of the respective scales, and there was significant variance (random effects: u0) across families in each of the outcomes.

Table 3.

Fixed and random effects for mean-only models predicting LC worry, conversation orientation, and conformity orientation.

| Fixed effect | Random effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ00 | T | uo | χ2(16) | R | |

| LC worry | 2.43 | 12.73*** | 0.32 | 34.49** | 0.87 |

| Conversation orientation | 4.78 | 24.22*** | 0.26 | 26.35* | 1.17 |

| Conformity orientation | 3.95 | 20.10*** | 0.36 | 36.25** | 0.85 |

LC: lung cancer.

df for t tests and χ2 = 16.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Influence of family communication on the effects of normative perceptions

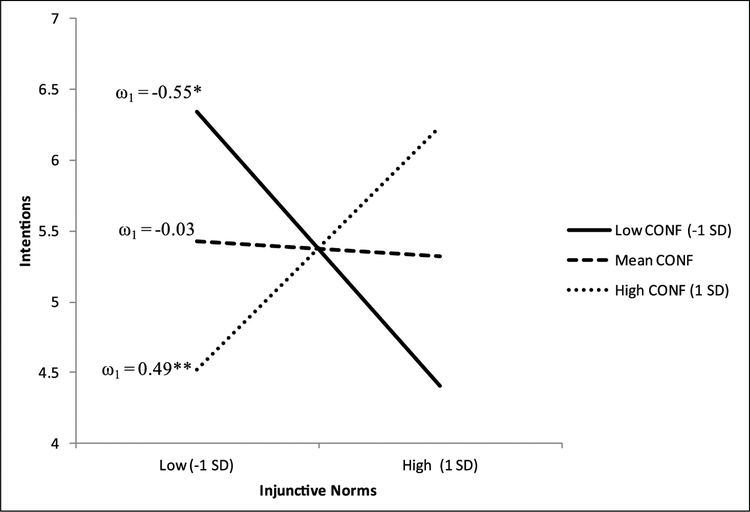

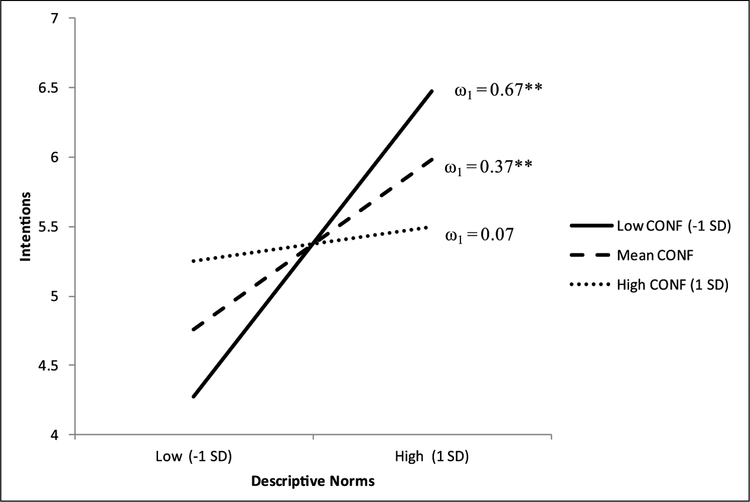

We hypothesized that the relations between injunctive and descriptive norms and intentions would be stronger among families higher in conformity and lower in conversation. Model estimates of fixed and random effects coefficients are presented in Table 4. The results indicated significant main effects of PBC (γ20 = 0.28, t16 = 2.18, p < .05) and of descriptive norms (γ50 = 0.37, t9 = 3.21, p < .05) on intentions. Conformity orientation had a significant cross-level interaction with injunctive norms (γ41 = 1.19, t9 = 3.49, p < .01) and marginally significant cross-level interactions with descriptive norms (γ51 = −0.68, t9 = −2.09, p < .10). Conversation orientation had a marginally significant cross-level interaction with injunctive norms (γ42 = 0.72, t9 = 2.22, p < .10). We probed both the significant and marginal interactions with methods outlined by Preacher et al. (2006), and identified regions for the moderating variable within which the simple slope for the substantive relationships were significant. Consistent with our hypotheses, results indicated a statistically significantly and positive simple slope for the association between injunctive norms and intentions for families whose conformity was 0.57 SD above mean conformity; results also indicated that the relationship between injunctive norms and intentions was significantly negative for families 0.72 SD below mean conformity (Figure 1). Contrary to our hypothesis, the simple slope for the association between descriptive norms and intentions became statistically non-significant for families whose conformity was above 0.52 SD above mean conformity, whereas it was significantly positive for those below 0.52 SD mean conformity (Figure 2). Finally, as hypothesized, the simple slope for the association between injunctive norms and intentions was significantly positive for families greater than 2.56 SD above mean conversation orientation and was significantly negative for families less than 2.62 SD below mean conversation orientation (Figure 3), indicating significant associations between injunctive norms and intentions at the relatively extremes of conversation orientation.

Table 4.

Fixed and random effects for multilevel regression examining the moderation effect of family communication on the relationship between perceived norms and intentions.

| Fixed effect | γ | t | df |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model intercept | |||

| Intercept | 5.37 | 24.16** | 14 |

| Conformity orientation | 0.00 | 0.00 | 14 |

| Conversation orientation | −0.78 | −1.36 | 14 |

| Affective attitude Intercept | 0.17 | 0.62 | 9 |

| PBC Intercept | 0.28 | 2.18* | 16 |

| Instrumental attitude Intercept | 0.36 | 1.36 | 9 |

| Injunctive norms Intercept | −0.03 | −0.22** | 9 |

| Conformity orientation | 1.19 | 3.49 | 9 |

| Conversation orientation | 0.72 | 2.22f | 9 |

| Descriptive norms Intercept | 0.37 | 3.21* | 9 |

| Conformity orientation | −0.68 | −2.09† | 9 |

| Conversation orientation | 0.03 | 0.08 | 9 |

| Random effect | Variance | χ2 | df |

| Model intercept, u0 | 0.48 | 33.22** | 14 |

| PBC, u2 | 0.08 | 28.56** | 16 |

| R | 0.88 |

PBC: perceived behavioral control.

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .10.

Figure 1.

Injunctive norms by conformity orientation interaction.

ω1: simple slope; CONF: conformity orientation.

*p < .05 and **p < .01.

Figure 2.

Descriptive norms by conformity orientation interaction.

ω1: simple slope; CONF: conformity orientation.

*p < .05 and **p < .01.

Figure 3.

Injunctive norms by conversation orientation interaction.

ω1: simple slope; CONV: conversation orientation.

*p < .05.

Influence of family communication on the effects of family-level LC worry

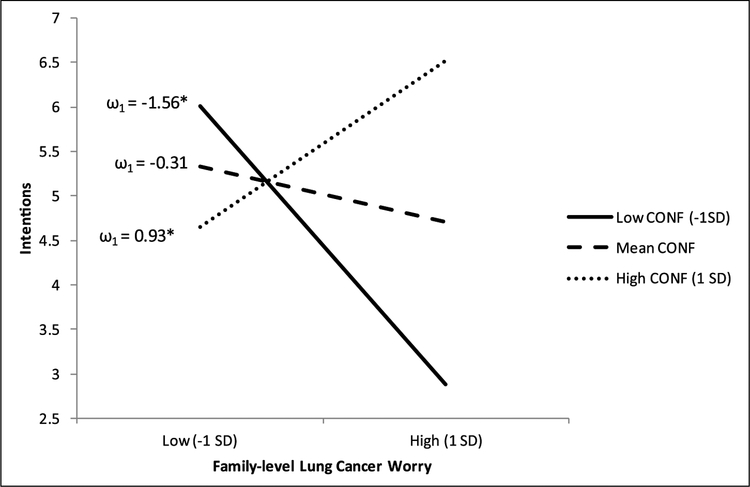

We hypothesized that family-level LC worry would be directly related to individuals’ intentions to avoid ETS, and further, that the magnitude of that association will depend on FCPs. Fixed and random effects coefficients are presented in Table 5. Results indicated significant main effects of PBC (γ30 = 0.32, t12 = 3.86, p < .01) and descriptive norms (γ60 = 0.35, t12 = 2.74, p < .05) on intentions. There was no significant main effect of family-level LC worry on intentions (γ03 = −0.31, t11 = −0.79, ns); however, in partial support of our hypothesis, there was a significant interaction between LC worry and conformity at the family level (γ04 = 1.25, t11 = 2.75, p < .05). We probed the interaction with methods outlined by Preacher et al. (2006). Results indicated that the relationship between family-level LC worry and intentions was significantly negative among families whose conformity was below 0.86 SD mean conformity and was significantly positive among those families whose conformity was above 0.77 mean conformity (Figure 4). In other words, among high-risk LC families, individuals from high conformity families who worried more had stronger intentions to avoid ETS, whereas individuals from low conformity families who worried more had weaker intentions to avoid ETS.

Table 5.

Fixed and random effects for multilevel regression examining the moderation effect of family communication on the relationship between family-level LC worry and intentions.

| Fixed effect | γ | t | df |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model intercept | |||

| Intercept | 5.02 | 17.81** | 11 |

| Conformity orientation | 0.57 | 1.80 | 11 |

| Conversation orientation | 0.04 | 0.17 | 11 |

| Family LC worry | −0.31 | −0.79 | 11 |

| Conformity × Fam LC worry | 1.25 | 2.75* | 11 |

| Conversation × Fam LC worry | 0.37 | 1.33 | 11 |

| LC worry Intercept | −0.35 | −1.13 | 14 |

| Conformity orientation | 0.02 | 0.06 | 14 |

| Conversation orientation | 0.32 | 1.12 | 14 |

| Affective attitude Intercept | 0.21 | 0.72 | 12 |

| PBC Intercept | 0.32 | 3.86** | 12 |

| Instrumental attitude Intercept | 0.1 1 | 0.38 | 12 |

| Injunctive norms Intercept | 0.08 | 0.58 | 12 |

| Descriptive norms Intercept | 0.35 | 2.74* | 12 |

| Random effect | Variance | χ2 | df |

| Model intercept, u0 | 0.38 | 18.64* | 8 |

| LC worry, u1 | 0.63 | 25.79** | 11 |

| r | 0.92 |

PBC: perceived behavioral control; LC: lung cancer.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .10.

Figure 4.

Family-level lung cancer worry by conformity orientation interaction.

ω1: simple slope; CONF: conformity orientation.

*p < .05.

Discussion

We used a TPB and FCPT framework to examine family conversation and conformity orientation patterns as potential moderators of (1) normative perceptions and intention to avoid ETS, and (2) family-level LC worry and intention to avoid ETS. We predicted that normative perceptions would have a stronger influence on intentions to avoid ETS in families that are high in conversation orientation (i.e. communicate frequently and discuss a wide range of topics) compared to families with low conversation orientation. Similarly, we predicted that normative perceptions would have a stronger influence in families that are high in conformity (i.e. encourage homogeneity of attitudes and beliefs) compared to families with low conformity orientation. Lastly, we predicted that when controlling for individual-level LC worry, family-level LC worry would have a stronger influence on intention to avoid ETS when families are high in conversation orientation and, separately, high in conformity orientation.

Family communication patterns and subjective norms

Overall, our findings were consistent with our hypotheses. Specifically, we found that injunctive norms were positively related to intentions to avoid ETS in families that were high in conformity and in families that were high in conversation orientations. Interestingly, however, this was not the case for descriptive norms—we found a positive association between descriptive norms and intentions to avoid ETS in low conformity families and no relationship in high conformity families. Additionally, we found that conversation orientation did not influence the relationship between descriptive norms and intentions. It is not surprising that the effects of conformity and conversation orientations on the relationships between normative perceptions and intentions are distinct between injunctive and descriptive norms. Much previous research has indicated that injunctive and descriptive norms are distinct constructs (Lapinski and Rimal, 2005; Manning, 2009, 2011a, 2011b; Norman et al., 2005; Reno et al., 1993), and compelling research suggests that the magnitude of the effects of normative perceptions depends on the type of norm that is salient (Cialdini et al., 1990; Mollen et al., 2013). However, our current data reveal some additional interesting effects of family communication on the joint effects of normative perceptions on intentions. In addition to the positive relationship between injunctive norms and intentions when conversation and conformity orientations were high, there was an inverse relationship indicated by a negative regression coefficient for the relationship between injunctive norms and intentions when conversation and conformity orientations were low. However, there were no negative coefficients for the relationship between injunctive norms and intentions, or its cross-level interactions, when descriptive norms were excluded from the model. This pattern of change from positive to negative regression coefficients when additional variables are introduced can be taken as evidence of a suppressor effect of injunctive norms among families low in conformity and conversation orientations (Darlington, 1968; Maassen and Bakker, 2001).

Prior work has identified similar suppressor effects when examining the joint influence of injunctive and descriptive norms (Manning, 2009, 2011b). In the current ETS avoidance context, our speculative interpretation is that when families have less conformity, descriptive norms share a stronger relationship with intentions when there are not simultaneously strong injunctive norms. In other words, two individuals from families that are lower in conformity (e.g. greater variability in attitudes and beliefs) may have descriptive normative perceptions of equal magnitude; however, the descriptive norms will have a stronger effect on intentions for the person with weaker injunctive normative perceptions. Although there were similar effects for conversation orientation, results indicated that conversation orientation had to be very low (i.e. almost 3 SD below the mean) for the effects to be significant. The suppressor effect may be most evident among low conformity and low conversation families because behavioral injunctions in high-risk LC families who typically value individuality and heterogeneity of beliefs and who interact less frequently and around a narrower range of topics may be so atypically salient for healthy non-smoking-related behaviors that they reduce the influence of other types of normative perceptions. When behavioral injunctions are less salient, descriptive norms maintain their influence on intentions to avoid ETS. Future research may continue to probe this hypothesis.

Among families higher in conformity and conversation orientations, injunctive norms are likely salient sources of information when it comes to behavioral decision-making; hence, the relationship between injunctive norms and intentions is stronger. We did not find a stronger relationship between descriptive norms and intentions among families higher in conformity and conversation orientations. Injunctive norms may be so influential in families higher in conformity and conversation that perceptions of what others do are less salient sources of information for behavioral decision-making. Considering some evidence that normative perceptions of family members’ behaviors are more influential for health-related behaviors than injunctive normative perceptions (Pedersen et al., 2015), and in light of studies showing that contextual factors (Cialdini et al., 1990; Kallgren et al., 2000; Reno et al., 1993) and behavioral factors (Manning, 2011a, 2011b) moderate the influence of injunctive and descriptive norms on intentions and behaviors, future studies should probe why “do as I say” may hold more weight than “do as I do” among high-risk LC families when it comes to avoiding ETS.

Family communication patterns and LC worry

Regarding family-level LC worry, the data were partially consistent with our predictions. The more that high conformity families worried about LC, the stronger their intentions to avoid ETS. The more that low conformity families worried about LC, the weaker their intentions to avoid ETS. Conversation orientation failed to exhibit similar effects on the relationship between family-level worry and intentions. It is somewhat inarguable that worrying about LC is warranted among these high-risk families, and individuals from families that conform may all recognize this justifiable worry when it is present, and thus have stronger intentions. The findings for families low in conformity are more perplexing. Perhaps motivations to be non-conformist may be associated with motivations to behave counter to perceived family norms, and thus despite the high risk associated with ETS, perceptions of family-level worries weakened intentions to engage in what would be considered normative ETS avoidance behaviors. Future studies may probe this hypothesis among low conformity families by examining whether perceptions of one’s traditionally individualistic family members coalescing around a particular worry leads one to distance himself or herself from contextually related behaviors.

Limitations and future directions

This study has some limitations that must be considered. First, although the sample size was appropriate for this exploratory study, it did not allow for more nuanced analyses of the relationships among the variables. For example, a larger sample might have afforded us the power to test all hypotheses simultaneously with one model. Second, the outcome variable is limited to intent to avoid ETS. While intentions have been shown to predict behavior (Ajzen, 1991, 2011), future studies should examine whether our findings have a meaningful impact on actual ETS avoidance behaviors. A related issue is that intentions to avoid other behaviors that may lead to LC, such as smoking, were not assessed. We cannot assume our findings regarding norms, family-level worry, and conversation and conformity orientations would apply to other LC-relevant behaviors. Relatedly, the frequency of smoking was very low among the individuals from high-risk LC families; however, these families may not be representative of the population of high-risk LC families due to the fact that they were recruited from a population that has some interest in research (as evidenced by their initial involvement in the GELC study). Inasmuch as this criticism may be levied against any family unit that chooses to be involved with family-relevant health research, attempts to examine these relationships among naïve families may provide additional information. Future research would benefit from assessing normative (descriptive and injunctive) influence on other LC-relevant behaviors (e.g. quitting smoking, encouraging family members to quit smoking) in addition to actual ETS avoidance behavior. Future research may also examine the benefit of including support from family members in ETS avoidance and smoking cessation interventions (e.g. soliciting family members for smoking cessation support via moderated telephone conversations).

Conclusion

Exposure to ETS (i.e. second-hand smoke) is an independent LC risk factor over and above smoking. This study advances our understanding of predictors of intentions to avoid ETS and, specifically, provides novel information about the role of family worry, FCPs, and the unique contributions of descriptive and injunctive norms on these intentions. Reducing exposure to ETS among individuals from “high-risk” (and potentially “smoking”) families can significantly reduce their risk for LC as well as morbidity and mortality from other smoking-related diseases. Knowledge about the role of the family and norms in reducing exposure to second-hand smoke can also benefit smoking cessation interventions that feature reduction of ETS as a target behavior.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is part of a larger investigation of family communication about lung cancer risk behaviors funded by a Strategic Research Initiative Grant from Karmanos Cancer Institute (PI: F. Harper). Portions of this research were presented at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (2011) The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health 26: 1113–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, et al. (2001) Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 127: 142–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CS, Allen P, Crawford MA, et al. (1999) Taking a first puff: Cigarette smoking experiences among ethnically diverse adolescents. Ethnicity & Health 4: 245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asomaning K, Miller DP, Liu G, et al. (2008) Second hand smoke, age of exposure and lung cancer risk. Lung Cancer 61: 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besaratinia A and Pfeifer GP (2008) Second-hand smoke and human lung cancer. The Lancet Oncology 9: 657–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR and Kallgren CA (1990) A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58: 1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Norman P and Bell R (2002) The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychology 21: 194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coté ML, Liu M, Bonassi S, et al. (2012) Increased risk of lung cancer in individuals with a family history of the disease: A pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. European Journal of Cancer 48: 1957–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington RB (1968) Multiple regression in psychological research and practice. Psychological Bulletin 69: 161–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw RNH, Scholte RHJ, Sargent JD, et al. (2010) Do interactions between personality and social-environmental factors explain smoking development in adolescence? Journal of Family Psychology 24: 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW and Trichopoulos D (1997) Risk of lung cancer from environmental exposures to tobacco smoke. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC 8: 333–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME and Willemsen M (2004) Communication about smoking in Dutch families: Associations between anti-smoking socialization and adolescent smoking-related cognitions. Health Education Research 19: 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnow M, Chassin L, Presson CC, et al. (1998) Determinants of parental attempts to deter their children’s cigarette smoking. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 19: 453–468. [Google Scholar]

- Fontham ET, Correa P, Reynolds P, et al. (1994) Environmental tobacco smoke and lung cancer in nonsmoking women A multicenter study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association; 271: 1752–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks MM, Pienta AM and Wray LA (2002) It takes two: Marriage and smoking cessation in the middle years. Journal of Aging and Health 14: 336–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Goldstein AM, Consonni D, et al. (2009) Family history of cancer and nonmalignant lung diseases as risk factors for lung cancer. International Journal of Cancer: Journal International du Cancer 125: 146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstad S, Bjerg A, Ekerljung L, et al. (2013) Passive smoking exposure is associated with increased risk of COPD in never-smokers. Chest 145(6): 1298–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallgren CA, Reno RR and Cialdini RB (2000) A focus theory of normative conduct: When norms do and do not affect behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26: 1002–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB and Wu P (1995) The contributions of mothers and fathers to the intergenerational transmission of cigarette smoking in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence 5: 225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner AF and Fitzpatrick MA (2002) Understanding family communication patterns and family functioning: The roles of conversation orientation and conformity orientation In: Gudykunst WB (ed.) Communication Yearbook 26 Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 36–68. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner AF and Fitzpatrick MA (2006) Family communication patterns theory: A social cognitive approach In: Braithwaite DO and Baxter LA(eds) Engaging Theories in Family Communication: Multiple Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski MK and Rimal RN (2005) An explication of social norms. Communication Theory 15: 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lau RR, Quadrel MJ and Hartman KA (1990) Development and change of young adults’ preventive health beliefs and behavior: Influence from parents and peers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 31: 240–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y-L, Hsiao C-F, Chang G-C, et al. (2013) Risk factors for primary lung cancer among never smokers by gender in a matched case-control study. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC 24: 567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maassen GH and Bakker AB (2001) Suppressor variables in path models: Definitions and interpretations. Sociological Methods & Research 30: 241–270. [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Pollak KI, Garst J, et al. (2003) Distress and motivation for smoking cessation among lung cancer patients’ relatives who smoke. Journal of Cancer Education 18: 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan B and Conner M (2003) Using the theory of planned behaviour to understand alcohol and tobacco use in students. Psychology, Health & Medicine 8: 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan B, Higgins AR and Conner M (2005) Using an extended theory of planned behaviour to understand smoking amongst schoolchildren. Addiction Research & Theory 13: 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Kashy D, Weinberg DS, et al. (2012) Using the interdependence model to understand spousal influence on colorectal cancer screening intentions: A structural equation model. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 43: 320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M (2009) The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology 48: 649–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M (2011a) When normative perceptions lead to actions: Behavior-level attributes influence the non-deliberative effects of subjective norms on behavior. Social Influence 6: 212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Manning M (2011b) When we do what we see: The moderating role of social motivation on the relation between subjective norms and behavior in the theory of planned behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 33: 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Day MA (2002) Parent-adolescent communication about alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. Journal of Adolescent Research 17: 604–616. [Google Scholar]

- Moan IS and Rise J (2005) Quitting smoking: Applying an extended version of the theory of planned behavior to predict intention and behavior. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research 10: 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Moan IS and Rise J (2006) Predicting smoking reduction among adolescents using an extended version of the theory of planned behaviour. Psychology & Health 21: 717–738. [Google Scholar]

- Mollen S, Rimal RN, Ruiter RAC, et al. (2013) Healthy and unhealthy social norms and food selection: Findings from a field-experiment. Appetite 65: 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, Seltzer JA and Schwartz CR (2008) Neighborhood norms and substance use among teens. Social Science Research 37: 138–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Clark T and Walker G (2005) The theory of planned behavior, descriptive norms, and the moderating role of group identification. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35: 1008–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, et al. (2011) Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: A retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. The Lancet 377: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan FV, Callan VJ and Baglioni A (1999) Cigarette use by adolescents: Attitude-behavior relationships. Substance Use & Misuse 34: 455–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten R, Engels RCME and Prinstein MJ (2009) A prospective study of perception in adolescent smoking. The Journal of Adolescent Health 44: 478–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Grønhøj A and Thøgersen J (2015) Following family or friends: Social norms in adolescent healthy eating. Appetite 86: 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povey R, Conner M, Sparks P, et al. (2000) The theory of planned behaviour and healthy eating: Examining additive and moderating effects of social influence variables. Psychology & Health 14: 991–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ and Bauer DJ (2006) Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 31: 437. [Google Scholar]

- Quadrel MJ and Lau RR (1990) A multivariate analysis of adolescents’ orientations toward physician use. Health Psychology 9: 750–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS and Congdon R (2010) HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. 7.01 ed Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reno RR, Cialdini RB and Kallgren CA (1993) The transsituational influence of social norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64: 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie LD and Fitzpatrick MA (1990) Family communication patterns: Measuring intrapersonal perceptions of interpersonal relationships. Communication Research 17: 523–544. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AG, Prysak GM, Bock CH, et al. (2007) The molecular epidemiology of lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 28: 507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AG, Yang P and Swanson GM (1996) Familial risk of lung cancer among nonsmokers and their relatives. American Journal of Epidemiology 144: 554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P and Taylor S (1999) Predicting intentions to use condoms: A meta-analysis and comparison of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29: 1624–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Conner M and Norman P (2001) Can the theory of planned behavior explain patterns of health behavior change? Health Psychology 20: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Vineis P, Hoek G, Krzyzanowski M, et al. (2007) Lung cancers attributable to environmental tobacco smoke and air pollution in non-smokers in different European countries: A prospective study. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 6: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J (2012) The contribution of parent–child interactions to smoking experimentation in adolescence: Implications for prevention. Health Education Research 27: 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KA, Conger RD, Wallace LE, et al. (1999) The intergenerational transmission of health-risk behaviors: Adolescent lifestyles and gender moderating effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40: 258–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]