Abstract

Background

The associations between the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and dementias are as yet to be studied in Taiwan. The aim of this study is to clarify as to whether HIV infections are associated with the risk of dementia.

Methods

A total of 1,261 HIV-infected patients and 3,783 controls (1:3) matched for age and sex were selected between January 1 and December 31, 2000 from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Fine and Gray’s survival analysis (competing with mortality) analyzed the risk of dementias during the 15-year follow up. The association between the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and dementia was analyzed by stratifying the HAART status among the HIV subjects.

Results

During the follow-up period, 25 in the HIV group (N= 1,261) and 227 in the control group (N= 3,783) developed dementia (656.25 vs 913.15 per 100,000 person-years). Fine and Gray’s survival analysis revealed that the HIV patients were not associated with an increased risk of dementia, with the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) as 0.852 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.189–2.886, p=0.415) after adjusting for sex, age, comorbidities, geographical region, and the urbanization level of residence. There was no significant difference between the two groups of HIV-infected patients with or without HAART in the risk of dementia.

Conclusion

This study found that HIV infections, either with or without HAART, were not associated with increased diagnoses of neurodegenerative dementias in patients older than 50 in Taiwan.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, highly active antiretroviral therapy, dementia, National Health Insurance Research Database, cohort study

Introduction

In Taiwan, 4.97% of those older than 65 years had dementia,1 which is a heavy burden to carry for the family members of patients with dementia and their caregivers and community, and the society as a whole.2–5 Previous studies had found that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections were associated with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND)6 and HIV-associated dementia (HAD).7 Many HIV patients developed HAD in the early years of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic.8 While HAD decreased in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era during these decades,9 HAND, with mild and fluctuating symptoms, rather than being constantly progressive as seen in dementias, such as Alzheimer Disease (AD). A large proportion of HAND is unrecognized by the HIV patients, or the asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI).10

In the HIV patients on HAART, a near-normal lifespan today was found. It is a challenge to distinguish neurodegenerative dementias from HAND and investigate the association between HIV and dementia.11,12 Turner et al reported of a patient with common pathology of HAD and AD.13 Green at al suggested an association between HIV and amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulations in the brain.14 Intra-neuronal accumulation of Aβ could cause the damage and cognitive impairment.15,16 Moreover, in a study of 80 HIV-infected individuals, microglia activation due to the HIV replication in the brain could cause an accumulation of amyloid-beta.17 Furthermore, the HAART could not only reduce the HIV in the brain, but also potentially neurotoxic drugs, which could contribute to the secondary declines in the cognitive function.18 The HIV-infected patients in Taiwan could receive free HAART, paid by the budget provided by Taiwan’s Center for Diseases Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, once the diagnosis has been confirmed. However, there were 28.9% of patients with HIV infections (5173 in 17,903) and 7.4% of patients with AIDS (120 in 1629) who have not been receiving HARRT in a 15-year cohort study.19,20 Therefore, whether HIV infections and HARRT are associated with dementia is an important topic. Investigation on the association between HIV infections and the risk of dementia among older patients living with HIV is therefore needed.

This study aimed to investigate the association between HIV and neurodegenerative dementias in the modern HAART era, as well as the relationship with the HAART among older patients living with HIV. We hypothesize that we could assess the incidence of dementia diagnosis in the HIV patients aged ≥ 50 years, by using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), a claims database retrieved from the whole population of Taiwan.

Methods

Data Sources

The National health insurance (NHI) Program, a mandatory and universal health insurance program in Taiwan, has been launched since 1995, which covered contracts with 97% of the medical providers with approximately 23 million beneficiaries or more than 99% of the population.21 The details of this program were documented in several previous studies.22–24 The NHIRD contains comprehensive and detailed data regarding the total outpatient and a subset of the NHIRD, as a two million Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID), with individual diagnoses coded by the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Several previous studies have confirmed the accuracy and validity of the diagnoses as myocardial infarction,25 diabetes,26 oral cancer,27 and stroke,28 in the NHIRD.

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study and waived the need of individual consents since all the identification data were encrypted in the NHIRD (IRB: 1-106-05-055).

Study Design And Sampled Participants

This is a retrospective matched-cohort research using the LHID between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2015. Subjects aged 50 years or older with a diagnosis as HIV (ICD-9-CM codes of 042, 043, 044, and V08) were selected. Each HIV-infected patient was required to receive a diagnosis in an inpatient setting or at three or more outpatient visits in a consecutive year, who had undergone the examinations for HIV viral loads or CD4+ counts identified by the NHI order codes in the NHI system (12071A, 12071B, 12073A, 12073B, 12074A, 12074B, 14074B, and 26017A) within the first one-year study period. A 1:3 sex-, age-, and index year-matched controls were randomly selected for each HIV patient. The exclusion criteria for the cohorts were unknown sex, subjects diagnosed with dementia or HIV before the index date, or <50 years old during the study period. The index date was defined as the time when the individuals were first diagnosed with an HIV infection within the one-year study period. Whether the HIV patients received HAART therapy after diagnosis during the follow-up period was identified using the antiretroviral medicine order code and the prescription dates from the inpatient and outpatient claim data.

Outcomes

All of the HIV participants and controls were followed from the index date until the onset of dementia, death, withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2015. Patients diagnosed with dementia were identified by ICD-9-CM codes with Alzheimer's dementia (AD, ICD-9-CM 331.0), vascular dementia (VaD, ICD-9-CM 290.41–290.43), and other dementia (ICD-9-CM 290.0, 290.10–290.13, 290.20–290.21, 290.3, and 290.8–290.9).

In Taiwan, the clinical diagnosis of dementia must conform to the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV), or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), with a history of decline in the cognitive function and activities of daily living for more than six months. The blood tests including the venereal disease research laboratory, thyroid function, complete blood count, fasting sugar, glutamic–oxaloacetic transaminase, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum B12 and folic acid levels, cognitive function tests, such as Mini-Mental status examination (MMSE), and neuro-image studies, with either brain computerized tomography or magnetic resonance image, were conducted to differentiate the etiology of dementia. The diagnostic work-up must be performed and confirmed by a certificated neurologist or psychiatrist.29

Covariates

The covariates include sociodemographic and comorbidities. Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, education, monthly income, urbanization level, and regions of residence. The monthly income has been divided into three categories in New Taiwan Dollars [NT$]: <18,000, 18,000–34,999, ≥35,000. The urbanization level was defined by population and certain indicators of the city’s level of development. Level 1 urbanization was defined as having a population greater than 1,250,000 people and a specific status of political, economic, cultural and metropolitan development. Level 2 urbanization was defined as having a population between 500,000 and 1,250,000 and an important role in the Taiwanese political system, economy and culture. Urbanization levels 3 and 4 were defined as having a population between 150,000 and 500,000 and less than 150,000, respectively.30

Comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 250), hypertension (401.1, 401.9, 402.10, 402.90, 404.10, 404.90, 405.1, and 405.9), hyperlipidemia (272.x), coronary artery disease (410–414), obesity (278), all cancers (140–208), depressive disorders (296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4, and 311), bipolar disorder (296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x, and 296.9x), anxiety disorders (300, except 300.4), alcohol use disorders (303 and 305.00–305.03), substance use disorders (304 and 305), and insomnia (307.4 and 780.5).

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) is one of the most widely used comorbidity index.31,32 CCI consists of 22 conditions,33 including diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and hemiplegia (stroke),34 which were mostly associated with AD.

Statistical Analysis

The SPSS software version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used to conduct the statistical analyses. The Pearson chi-square test was used for the analysis of categorical data. Continuous variables presented as the mean (± SD) were analyzed using the two-sample t-test. To investigate the risk of AD, VaD, and other dementia for patients with and without HIV, a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, and comorbidities. The Fine and Gray’s model was used to conduct competing risk analysis for the association between HIV, dementia, and death. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to determine the difference in the risk of dementia for the HIV patients and control groups using the log rank test. The effect of HAART on the incidence of dementia by stratifying the HAART status among the HIV subjects was also analyzed. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample Characteristics

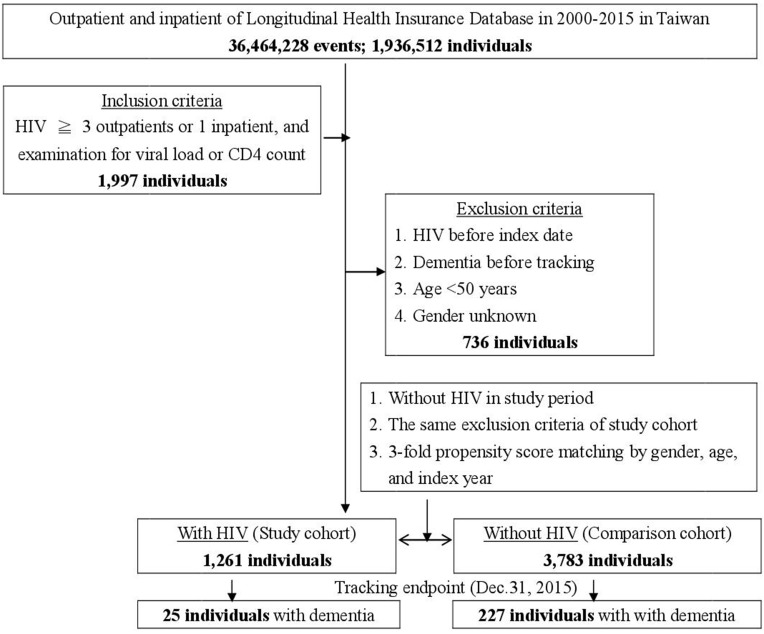

A total of 1,261 HIV-infected patients and 3,783 controls matched for age, sex, and comorbidity were included from the study period (Figure 1). At the baseline for this study, the mean age (±SD) of the HIV patients was 59.37±8.33 years and 86.28% were male. The demographic characteristics and covariates of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age group, sex, education, and monthly insurance premiums between the HIV patients and the controls. When compared with the controls, the HIV patients tended to have higher proportions of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, depression, and substance use disorder. In addition, the HIV patients tended to have lower CCI-R scores and higher rates living in level 1 or 2 urbanization region, and in the north of Taiwan. The HIV group tended to seek medical care from the medical centers and regional hospitals.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of study sample selection from National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan.

Table 1.

Characteristics Of Study At The Baseline

| HIV Infections | Total | With | Without | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 5,044 | 1,261 | 25.00 | 3,783 | 75.00 | |||

| Gender | 0.999 | ||||||

| Male | 4,352 | 86.28 | 1,088 | 86.28 | 3,264 | 86.28 | |

| Female | 692 | 13.72 | 173 | 13.72 | 519 | 13.72 | |

| Age (years) | 56.68±8.06 | 59.37±8.33 | 59.78±7.97 | 0.118 | |||

| Age group (years) | 0.999 | ||||||

| 50–64 | 3,852 | 76.37 | 963 | 76.37 | 2,889 | 76.37 | |

| ≥65 | 1,192 | 23.63 | 298 | 23.63 | 894 | 23.63 | |

| Education (years) | 0.519 | ||||||

| <12 | 2,979 | 59.06 | 735 | 58.29 | 2,244 | 59.32 | |

| ≥12 | 2,065 | 40.94 | 526 | 41.71 | 1,539 | 40.68 | |

| Insured premium (NT$) | 0.447 | ||||||

| <18,000 | 4,579 | 90.78 | 1,140 | 90.40 | 3,439 | 90.91 | |

| 18,000–34,999 | 319 | 6.32 | 88 | 6.98 | 231 | 6.11 | |

| ≥35,000 | 146 | 2.89 | 33 | 2.62 | 113 | 2.99 | |

| DM | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 4,345 | 86.14 | 1,124 | 89.14 | 3,221 | 85.14 | |

| With | 699 | 13.86 | 137 | 10.86 | 562 | 14.86 | |

| HTN | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 4,318 | 85.61 | 1,117 | 88.58 | 3,201 | 84.62 | |

| With | 726 | 14.39 | 144 | 11.42 | 582 | 15.38 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.002 | ||||||

| Without | 4,879 | 96.73 | 1,236 | 98.02 | 3,643 | 96.30 | |

| With | 165 | 3.27 | 25 | 1.98 | 140 | 3.70 | |

| CAD | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 4,580 | 90.80 | 1,198 | 95.00 | 3,382 | 89.40 | |

| With | 464 | 9.20 | 63 | 5.00 | 401 | 10.60 | |

| Obesity | 0.414 | ||||||

| Without | 5,042 | 99.96 | 1,261 | 100.00 | 3,781 | 99.95 | |

| With | 2 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| All cancers | 0.193 | ||||||

| Without | 4,587 | 90.94 | 1,135 | 90.01 | 3,452 | 91.25 | |

| With | 457 | 9.06 | 126 | 9.99 | 331 | 8.75 | |

| Depression | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 5,013 | 99.39 | 1,237 | 98.10 | 3,776 | 99.81 | |

| With | 31 | 0.61 | 24 | 1.90 | 7 | 0.19 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.414 | ||||||

| Without | 5,042 | 99.96 | 1,261 | 100.00 | 3,781 | 99.95 | |

| With | 2 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| Anxiety | 0.192 | ||||||

| Without | 5,016 | 99.44 | 1,251 | 99.21 | 3,765 | 99.52 | |

| With | 28 | 0.56 | 10 | 0.79 | 18 | 0.48 | |

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.228 | ||||||

| Without | 5,029 | 99.70 | 1,255 | 99.52 | 3,774 | 99.76 | |

| With | 15 | 0.30 | 6 | 0.48 | 9 | 0.24 | |

| Substance use disorders | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 5,009 | 99.31 | 1,229 | 97.46 | 3,780 | 99.92 | |

| With | 35 | 0.69 | 32 | 2.54 | 3 | 0.08 | |

| Insomnia | 0.595 | ||||||

| Without | 5,025 | 99.62 | 1,255 | 99.52 | 3,770 | 99.66 | |

| With | 19 | 0.38 | 6 | 0.48 | 13 | 0.34 | |

| CCI_R | 0.42±0.74 | 0.23±0.54 | 0.49±0.79 | <0.001 | |||

| Location | <0.001 | ||||||

| Northern Taiwan | 2,057 | 40.78 | 614 | 48.69 | 1,443 | 38.14 | |

| Middle Taiwan | 1,360 | 26.96 | 303 | 24.03 | 1,057 | 27.94 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 1,341 | 26.59 | 322 | 25.54 | 1,019 | 26.94 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 266 | 5.27 | 20 | 1.59 | 246 | 6.50 | |

| Outlets islands | 20 | 0.40 | 2 | 0.16 | 18 | 0.48 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 1,837 | 36.42 | 574 | 45.52 | 1,263 | 33.39 | |

| 2 | 2,103 | 41.69 | 544 | 43.14 | 1,559 | 41.21 | |

| 3 | 323 | 6.40 | 46 | 3.65 | 277 | 7.32 | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 781 | 15.48 | 97 | 7.69 | 684 | 18.08 | |

| Level of care | <0.001 | ||||||

| Medical center | 1,995 | 39.55 | 789 | 62.57 | 1,206 | 31.88 | |

| Regional hospital | 1,504 | 29.82 | 394 | 31.25 | 1,110 | 29.34 | |

| Local hospital | 1,545 | 30.63 | 78 | 6.19 | 1,467 | 38.78 | |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NT$, New Taiwan Dollars; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease, CCI-R, Charlson Comorbidity Index, dementia removed; P, Chi-square/Fisher exact test on category variables and independent-samples Student’s t-test on continue variables.

No Association Between HIV And The Risk Of Dementia

During the 15-year follow-up period, 25 in the HIV cohort (N= 1,261) and 227 in the control group (N= 3,783) developed dementia (656.25 vs 913.15 per 100,000 person-years). Table 2 depicts the results of the analysis on the association between the HIV infections and the risk of developing dementia, which were analyzed by the Fine and Gray’s competing analysis model. The adjusted HR of the HIV cohort in the development of dementia was 0.852 (95% CI: 0.189–2.886, p =0.415) after adjusting for sex, age, CCI scores, comorbidities, geographical region, and the urbanization level of residence, level of care, and monthly income. However, patients with depression (p =0.001), alcohol use disorders (p =0.006), and higher CCI scores (p <0.001) were associated with an increased risk of dementia. Subjects with the comorbidity of cancer were associated with a lower risk of dementia (p <0.001). Patients who lived in the residence of Urbanization level 3 were associated with a marginally lower risk of dementia (p =0.050). Patients who were treated in medical centers (p =0.003) and regional hospitals (p =0.011) also had a lower risk.

Table 2.

Factors Of Dementia By Using Cox Regression And Fine & Gray’s Competing Risk Model

| Competing Risk In The Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Crude HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

| HIV | ||||||||

| With | 0.682 | 0.109 | 2.576 | 0.572 | 0.852 | 0.189 | 2.886 | 0.415 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1.443 | 0.968 | 2.151 | 0.072 | 1.483 | 0.993 | 2.214 | 0.054 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| ≥65 | 0.903 | 0.678 | 1.202 | 0.484 | 0.943 | 0.704 | 1.264 | 0.696 |

| Education (years) | ||||||||

| ≥12 | 0.997 | 0.588 | 1.596 | 0.703 | 1.012 | 0.699 | 2.045 | 0.752 |

| Insured premium (NT$) | ||||||||

| <18,000 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 18,000–34,999 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.941 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.931 |

| ≥35,000 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.983 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.980 |

| DM | ||||||||

| With | 1.094 | 0.818 | 1.483 | 0.543 | 1.028 | 0.764 | 1.382 | 0.856 |

| HTN | ||||||||

| With | 0.839 | 0.635 | 1.110 | 0.219 | 0.813 | 0.609 | 1.086 | 0.161 |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||||||

| With | 0.650 | 0.289 | 1.462 | 0.297 | 0.756 | 0.331 | 1.726 | 0.506 |

| CAD | ||||||||

| With | 0.725 | 0.488 | 1.123 | 0.150 | 0.736 | 0.470 | 1.154 | 0.162 |

| Obesity | ||||||||

| With | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| All cancers | ||||||||

| With | 0.288 | 0.161 | 0.514 | <0.001 | 0.312 | 0.173 | 0.561 | <0.001 |

| Depression | ||||||||

| With | 3.240 | 1.868 | 6.262 | <0.001 | 2.975 | 1.538 | 5.753 | 0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||||||

| With | 0.000 | – | – | 0.946 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.981 |

| Anxiety | ||||||||

| With | 2.585 | 0.828 | 8.073 | 0.102 | 1.278 | 0.357 | 4.571 | 0.706 |

| Alcohol use disorders | ||||||||

| With | 6.622 | 1.645 | 26.657 | 0.008 | 7.243 | 1.752 | 29.948 | 0.006 |

| Substance use disorders | ||||||||

| With | 3.928 | 0.551 | 28.034 | 0.172 | 2.521 | 0.316 | 20.086 | 0.383 |

| Insomnia | ||||||||

| With | 2.298 | 1.022 | 5.167 | 0.044 | 1.846 | 0.799 | 4.264 | 0.151 |

| CCI_R | 1.368 | 1.208 | 1.549 | <0.001 | 1.353 | 1.202 | 1.545 | <0.001 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Northern Taiwan | Reference | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | ||||||

| Middle Taiwan | 1.120 | 0.826 | 1.517 | 0.466 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Southern Taiwan | 0.891 | 0.839 | 1.244 | 0.498 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Eastern Taiwan | 1.695 | 1.096 | 2.622 | 0.018 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Outlets islands | 2.556 | 0.628 | 10.383 | 0.189 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Urbanization level | ||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 0.651 | 0.468 | 0.907 | 0.011 | 0.852 | 0.582 | 1.248 | 0.412 |

| 2 | 0.594 | 0.434 | 0.912 | 0.001 | 0.736 | 0.528 | 1.030 | 0.074 |

| 3 | 0.566 | 0.318 | 1.007 | 0.053 | 0.559 | 0.313 | 1.000 | 0.050 |

| 4 (The lowest) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Level of care | ||||||||

| Medical center | 0.519 | 0.376 | 0.716 | <0.001 | 0.562 | 0.386 | 0.818 | 0.003 |

| Regional hospital | 0.642 | 0.476 | 0.865 | 0.004 | 0.673 | 0.496 | 0.914 | 0.011 |

| Local hospital | Reference | Reference | ||||||

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NT$, New Taiwan Dollars; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease, CCI-R, Charlson Comorbidity Index, dementia removed; HR, hazard ratio, CI, confidence interval, P, Chi-square/Fisher exact test on category variables and t-test on continue variables; adjusted HR, adjusted variables listed in this table.

The HIV infections were not associated with an increased risk of either types of dementia, such as AD (p =0.365), VaD (p =0.964), or other dementia (p =0.409), when compared to the control group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Of Dementia Subgroup By Using Cox Regression And Fine & Gray’s Competing Risk Model

| HIV | Non-UIV | Competing Risk In The Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia Subgroups | Event | PYs | Rate (Per 105 PYs) | Event | PYs | Rate(Per 105 PYs) | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

| Total | 25 | 3,809.55 | 656.25 | 227 | 24,859.12 | 913.15 | 0.852 | 0.189 | 2.886 | 0.415 |

| AD | 1 | 3,809.55 | 26.25 | 9 | 24,859.12 | 36.20 | 0.860 | 0.191 | 2.921 | 0.365 |

| VaD | 0 | 3,809.55 | 0.00 | 20 | 24,859.12 | 80.45 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.964 |

| Other dementia | 24 | 3,809.55 | 630.00 | 198 | 24,859.12 | 796.49 | 0.938 | 0.208 | 3.785 | 0.409 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AD, Alzheimer's dementia; VaD, vascular dementia; PYs, person-years; adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio: adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1; CI, confidence interval.

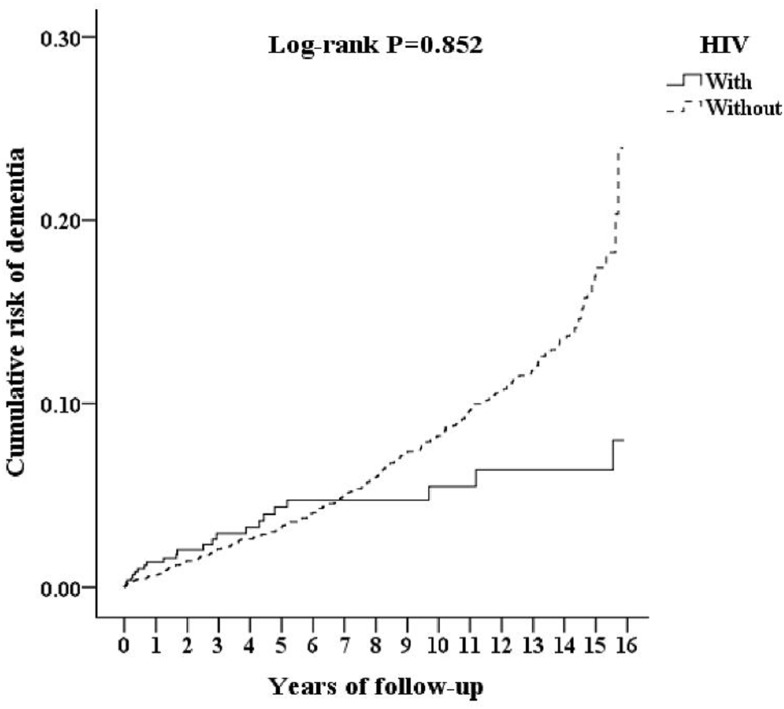

Kaplan–Meier Model For The Cumulative Incidence Of Dementia

The Kaplan–Meier analysis for the cumulative incidence of dementia revealed no differences between the HIV-infected individuals and the control group (log rank test P=0.852, Figure 2) as being statistically significant in AD, VaD, and other dementia.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier for cumulative incidence of dementia aged 50 and over stratified by HIV with log rank test.

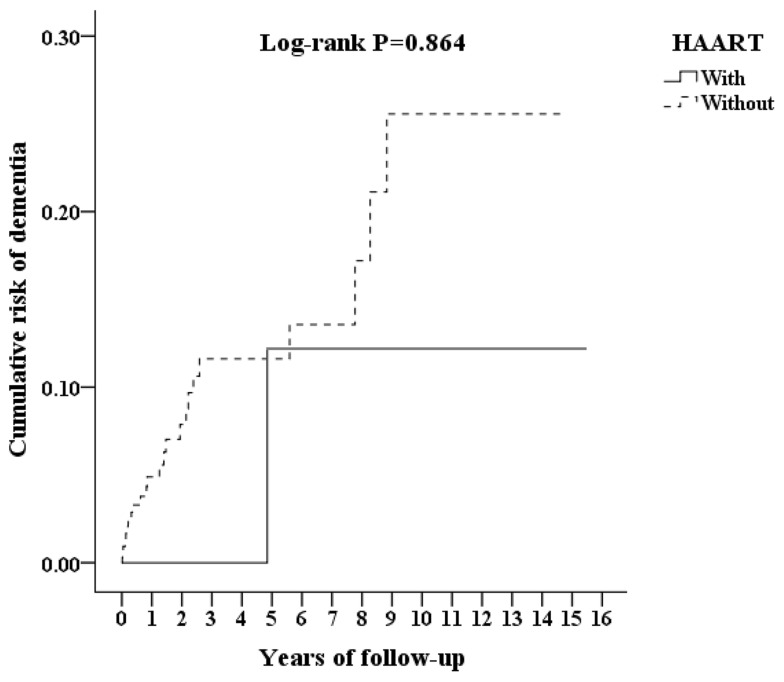

The HR Of Overall Dementia, AD, VAD, And Other Dementia In The HIV-Infected Patients With Or Without The Usage Of HAART

The Kaplan–Meier analysis for the cumulative incidence of dementia revealed no differences between the HAART users and the non-users (log rank test p=0.864, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier for cumulative incidence of dementia aged 50 and over stratified by HAART users and non-users with log rank test.

Table 4 shows that the HIV patients with HAART (N=746) were compared to those without (N=515). The mean proportion of days covered by HAART within the study period was 88.4±18.7 in the HIV subjects with HAART. While only one subject (0.13%) developed dementia in the subgroup with HAART, 24 (4.6%) developed dementia in those without HAART within the follow-up period. The HAART was not associated with the risk of dementia when compared to the group without HAART (adjusted HR =0.030 [95% CI: 0.001−168.45, p= 0.885]).

Table 4.

Factors Of Dementia Subgroup Among HIV Cohort By Using Cox Regression And Fine & Gray’s Competing Risk Model

| HAART | With | Without | Competing Risk In The Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia subgroups | Event | Rate (Per 105 PYs) | Event | Rate (Per 105 PYs) | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

| Overall | 1 | 42.62 | 24 | 1,640.15 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 168.45 | 0.885 |

| AD | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 68.34 | 0.000 | – | – | – |

| VaD | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Other dementia | 1 | 42.62 | 23 | 1,571.81 | 0.035 | 0.007 | 233.12 | 0.872 |

Abbreviations: PYs, person-years; HARRT, highly active antiretroviral therapy; adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio: adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

No Association Between HIV Infection And The Risk Of Dementia

In this nationwide cohort study, we identified HIV patients aged older than 50 and found that HIV was not associated with the increased risk of dementia diagnoses in comparison to the control group. The cumulative incidence rates of dementia were 1.9% in the HIV group, which were close to two previous studies35,36 of the prevalence of HAD in the HIV patients with rates of 1–2%, as a result of the effect of HAART. Therefore, this is a representative sample in the general population.

The evolution of the HIV virulence in response to the antiretroviral therapy on a widespread scale was also elicited in the modern HAART era. Although empirical evidence remains scarce, several studies have predicted the evolutionary trends towards a low level of virulence, and attenuation of the HIV with the simulation model,37,38 postulating the trade-off theory which described an adaptive balance between transmission and virulence.39,40 One study in Uganda reports that the set-point viral load, which is the most common measure of virulence, has declined over the last 20 years.41 However, the reason why HIV infections were not associated with the risk of dementia, contrary to the findings in two previous cross-sectional studies,36,42 needs further research.

Comparison To Previous Literature

One previous nationwide retrospective study in Taiwan reported a higher risk of psychiatric disorders among the HIV patients, including anxiety, depressive disorder, substance and alcohol use disorder, but the risk of dementia was not analyzed.43 About half of the HIV-infected individuals on HAART in the US sustained from a mild neurocognitive deficit instead of HAD.44,45 Previous cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that old age in an HIV patient is associated with a higher risk of dementia.36,42 One previous cohort study, using data from a geographically based program for the neurocognitive impairment in the HIV patients, found a high incidence of several neurologic disorders, such as distal sensory polyneuropathy, HAND, epilepsy, and other minor neurocognitive disorders.46 A retrospective study using the NHIRD found the risk of several neurological disorders, such as central nervous system infections, cognitive disorders, and neuropathy in the HIV patients with HAART, and the increased risk was found between old age at the HIV diagnosis and cognitive disorders.47 In the present study, we examined the association between an HIV cohort aged ≥ 50 and the risk of dementia, instead of a wider range of cognitive disorders in all age groups.

The Role Of HAART And The Risk Of Dementia

Either with or without the usage of HAART was not associated with the risk of dementia in the present study. Whilst the advent of therapy against HIV is drastically protective against the most severe forms of HAND, there has still prevailed a large proportion of cognitive impairment in the modern era.35 Several previous studies found the cognitive deficit of the HIV patients also revealed evidence for a change in the form of neurocognitive impairment associated with HIV.35,48,49 A 30-year longitudinal study for neurological symptoms among 80 HIV patients of a median age of 57, with a systematic neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment, showed that polyneuropathy, fatigue and mild depression were common diagnoses in the HIV patients undergoing HAART, and the brain images revealed mild age-related atrophic changes rather than HAND or HAD.50 Although the mixed results of the protective effect of HAART against neurological disorders were found,35,51 Tsai et al reported that a higher adherence of HAART significantly decreased the risk of neurological deficits.47 The present study found that depression, alcohol use disorder, and higher CCI scores were associated with an increased risk of dementia for the HIV cohort. This might well serve as a reminder for the clinicians to recognize the underlying neuropsychiatric symptoms and comorbidities in order to decrease the risk for any delayed diagnosis of the different types of dementia in the setting of geriatric HIV.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be considered. First, the diagnoses of dementia identified using LHID may be less accurate than those made in a prospective clinical study. Data on dementia on severity, stage, and care burdens were not available. The fact that no detailed information to assess neurocognitive domains, which were a fundamental aspect of HAND criteria,51 along with the types of dementia only identified from the ICD codes, may warrant consideration of misdiagnosis error, especially between HAD and AD. Second, older participants with dementia in other medical condition (ICD 294) were excluded from the outcome variables, which may reduce the information bias described above. However, relatively small sample sizes for the HIV subjects older than 50 from the NHIRD might have resulted in underpowered issues, which was revealed by the wide confidence interval for the HRs. Third, most of the types of dementia in the present study were other types of dementia rather than AD, which is the most common type of dementia (40–60% in all dementias), followed by VaD (20–30% in all dementias), and mixed or other dementias (7–15%) in Taiwan.52–54 The likely explanation rests in the nature of the frequently overlapping clinical features between the Alzheimer’s type and the other types of dementia, resulting in the difficulties in accurately differentiating the Alzheimer’s type from the other types of dementia, which may include a large proportion of AD patients in the clinical setting. In addition, the potential under-detection and the non-difference for the clinical diagnosis of dementia between the HAART users and non-users might exist. However, the impact of under-detection on the non-difference might have influenced both the HAART users and non-users.

Conclusion

This study found that HIV infections were not associated with an increased diagnosis of dementias in patients older than 50, either with or without HAART, in Taiwan. Further research with a prospective design is required to clarify as to whether HIV infections were associated with the risk of dementia and the role of HAART.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation under the grants from the Medical Affairs Bureau, the Ministry of Defense of Taiwan (grant no. MAB-107-084), and the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation (TSGH-C105-130, TSGH-C106-002, TSGH-C106-106, TSGH-C107-004, TSGH-C108-003, and TSGH-C108-151). These funding agencies did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Taiwan Alzheimer`s Disease Association. 2015-2056 expected dementia population report in Taiwan; 2013; Available from: http://www.tada2002.org.tw/tada_know_02.html#01 Accessed September, 10, 2014.

- 2.Lin SJ, Kuo SC, Yang YH. Appeals system and its outcomes in national health insurance in Taiwan. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(3):506–511. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzeng NS, Chang CW, Hsu JY, Chou YC, Chang HA, Kao YC. Caregiver burden for patients with dementia with or without hiring foreign health aides: a cross-sectional study in a northern taiwan memory clinic. J Med Sci. 2015;35(6):239–247. doi: 10.4103/1011-4564.172999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzeng NS, Chiang WS, Chen SY, et al. The impact of pharmacological treatments on cognitive function and severity of behavioral symptoms in geriatric elder patients with dementia. Taiwanese J Psychiatry. 2017;31(1):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang HY, Chen JH, Huang SY, et al. Forensic evaluations for offenders with dementia in Taiwan’s criminal courts. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2018;46(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zayyad Z, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis of HIV: from initial neuroinvasion to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(1):16–24. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0255-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price RW, Spudich SS, Peterson J, et al. Evolving character of chronic central nervous system HIV infection. Semin Neurol. 2014;34(1):7–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schouten J, Cinque P, Gisslen M, Reiss P, Portegies P. HIV-1 infection and cognitive impairment in the cART era: a review. AIDS. 2011;25(5):561–575. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437f9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmussen LD, May MT, Kronborg G, et al. Time trends for risk of severe age-related diseases in individuals with and without HIV infection in Denmark: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Lancet HIV 2015;2(7):e288–e298. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00077-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiao S, Rosen HJ, Nicolas K, et al. Deficits in self-awareness impact the diagnosis of asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment in HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(6):949–956. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guaraldi G, Prakash M, Moecklinghoff C, Stellbrink H-J-JAR. Morbidity in older HIV-infected patients: impact of long-term antiretroviral use. AIDS Rev. 2014;16(2):75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills EJ, Barnighausen T, Negin J. HIV and aging–preparing for the challenges ahead. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1270–1273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner RS, Chadwick M, Horton WA, Simon GL, Jiang X, Esposito G. An individual with human immunodeficiency virus, dementia, and central nervous system amyloid deposition. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;4:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DA, Masliah E, Vinters HV, Beizai P, Moore DJ, Achim CL. Brain deposition of beta-amyloid is a common pathologic feature in HIV positive patients. AIDS. 2005;19(4):407–411. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161770.06158.5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Achim CL, Adame A, Dumaop W, Everall IP, Masliah E. Increased accumulation of intraneuronal amyloid beta in HIV-infected patients. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4(2):190–199. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9152-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Ikezu T. The comorbidity of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease: a foreseeable medical challenge in post-HAART era. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4(2):200–212. doi: 10.1007/s11481-008-9136-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine AJ, Soontornniyomkij V, Achim CL, et al. Multilevel analysis of neuropathogenesis of neurocognitive impairment in HIV. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(4):431–441. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0410-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Underwood J, Robertson KR, Winston AJA. Could antiretroviral neurotoxicity play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in treated HIV disease? AIDS. 2015;29(3):253–261. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CY, Jen IA, Lan YC, et al. AIDS incidence trends at presentation and during follow-up among HIV-at-risk populations: a 15-year nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):589. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5500-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taiwan Center for Diseases Control. HIV/AIDS; 2014. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Category/ListContent/bg0g_VU_Ysrgkes_KRUDgQ?uaid=CqNo313w78G1fWhz429xDA Accessed September, 11, 2019.

- 21.Ho Chan WS. Taiwan’s healthcare report 2010. Epma J. 2010;1(4):563–585. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0056-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Yeh CB, et al. Are chronic periodontitis and gingivitis associated with dementia? A nationwide, retrospective, matched-cohort study in Taiwan. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;47(2):82–93. doi: 10.1159/000449166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Liu FC, et al. Fibromyalgia and risk of dementia-a nationwide, population-based, cohort study. Am J Med Sci. 2018;355(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, et al. Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections-a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Neurother. 2018;15(2):417–429. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng CL, Chien HC, Lee CH, Lin SJ, Yang YH. Validity of in-hospital mortality data among patients with acute myocardial infarction or stroke in National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin CC, Lai MS, Syu CY, Chang SC, Tseng FY. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(3):157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li-Ting C, Chung-Ho C, Yi-Hsin Y, Pei-Shan H. The development and validation of oral cancer staging using administrative health data. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:380. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, Lee CH, Lai ML. Validation of the National Health Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(3):236–242. doi: 10.1002/pds.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Lai MS, Lu CJ, Chen RC. How long can patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s dementia maintain both the cognition and the therapy of cholinesterase inhibitors: a national population-based study. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(3):278–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CY, Chen WL, Liou YF, et al. Increased risk of major depression in the three years following a femoral neck fracture–a national population-based follow-up study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity. a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00585-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:8. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr., et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinai E, Komatsu K, Sakamoto M, et al. Association of age and time of disease with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: a Japanese nationwide multicenter study. J Neurovirol. 2017;23(6):864–874. doi: 10.1007/s13365-017-0580-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanquart F, Grabowski MK, Herbeck J, et al. A transmission-virulence evolutionary trade-off explains attenuation of HIV-1 in Uganda. Elife 2016;5:e20492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraser C, Hollingsworth TD, Chapman R, de Wolf F, Hanage WP. Variation in HIV-1 set-point viral load: epidemiological analysis and an evolutionary hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(44):17441–17446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708559104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theys K, Libin P, Pineda-Pena AC, Nowe A, Vandamme AM, Abecasis AB. The impact of HIV-1 within-host evolution on transmission dynamics. Curr Opin Virol. 2018;28:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vrancken B, Baele G, Vandamme AM, van Laethem K, Suchard MA, Lemey P. Disentangling the impact of within-host evolution and transmission dynamics on the tempo of HIV-1 evolution. AIDS. 2015;29(12):1549–1556. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Van Baalen M. Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. J Evol Biol. 2009;22(2):245–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii aging with HIV-1 cohort. Neurology. 2004;63(5):822–827. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134665.58343.8d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen MH, Su TP, Chen TJ, Cheng JY, Wei HT, Bai YM. Identification of psychiatric disorders among human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals in Taiwan, a nine-year nationwide population-based study. AIDS Care. 2012;24(12):1543–1549. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.672716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakradhar S. A tale of two diseases: aging HIV patients inspire a closer look at Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2018;24(4):376–377. doi: 10.1038/nm0418-376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, et al. Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;75(13):1150–1158. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d5bb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai YT, Chen YC, Hsieh CY, Ko WC, Ko NY. Incidence of neurological disorders among HIV-infected individuals with universal health care in Taiwan from 2000 to 2010. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(5):509–516. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carvalhal A, Gill MJ, Letendre SL, et al. Central nervous system penetration effectiveness of antiretroviral drugs and neuropsychological impairment in the Ontario HIV treatment network cohort study. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(3):349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sacktor N, Skolasky RL, Seaberg E, et al. Prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Neurology. 2016;86(4):334–340. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heikinheimo T, Poutiainen E, Salonen O, Elovaara I, Ristola M. Three-decade neurological and neurocognitive follow-up of HIV-1-infected patients on best-available antiretroviral therapy in Finland. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e007986. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu HC, Lin KN, Teng EL, et al. Prevalence and subtypes of dementia in Taiwan: a community survey of 5297 individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(2):144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu CK, Lai CL, Tai CT, Lin RT, Yen YY, Howng SL. Incidence and subtypes of dementia in southern Taiwan: impact of socio-demographic factors. Neurology. 1998;50(6):1572–1579. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin RT, Lai CL, Tai CT, Liu CK, Yen YY, Howng SL. Prevalence and subtypes of dementia in southern Taiwan: impact of age, sex, education, and urbanization. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00225-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Taiwan Center for Diseases Control. HIV/AIDS; 2014. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Category/ListContent/bg0g_VU_Ysrgkes_KRUDgQ?uaid=CqNo313w78G1fWhz429xDA Accessed September, 11, 2019.