Abstract

Studying biofilm dispersal is important to prevent Listeria monocytogenes persistence in food processing plants and to avoid finished product contamination. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates (ROI and RNI, respectively) may trigger cell detachment from many bacterial species biofilms, but their roles in L. monocytogenes biofilms have not been fully investigated. This study reports on ROI and RNI quantification in Listeria monocytogenes biofilms formed on stainless steel and glass surfaces; bacterial culture and microscopy combined with fluorescent staining were employed. Nitric oxide (NO) donor and inhibitor putative effects on L. monocytogenes dispersal from biofilms were evaluated, and transcription of genes (prfA, lmo 0990, lmo 0807, and lmo1485) involved in ROI and RNI stress responses were quantified by real-time PCR (qPCR). Microscopy detected the reactive intermediates NO, peroxynitrite, H2O2, and superoxide in L. monocytogenes biofilms. Neither NO donor nor inhibitors interfered in L. monocytogenes growth and gene expression, except for lmo0990, which was downregulated. In conclusion, ROI and RNI did not exert dispersive effects on L. monocytogenes biofilms, indicating that this pathogen has a tight control for protection against oxidative and nitrosative stresses.

Keywords: Dispersal, Reactive oxygen intermediate, ROI, Reactive nitrogen intermediate, RNI

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes causes a rare, but life-threatening foodborne illness named listeriosis, which has been linked to ready-to-eat food consumption; food contamination usually occurs after heat treatment. Post-processing contamination is a concern for the food industry, especially if we consider that many bacteria can persist in the environment due to biofilm formation [1].

Biofilms are sessile microorganism communities attached to biotic or abiotic surfaces, embedded in a self-produced polymeric matrix. To eradicate this “city of microbes,” it is crucial to understand the steps that lead to its build up and maintenance [2, 3]. In this sense, dispersal is a critical stage in biofilm life cycle because it enables bacterial cells to escape from harsh conditions to reach less hostile environments [1]. This stage depends on numerous regulatory signals, and studying them is important to manage cell dispersal: converting sessile cells back to a planktonic phenotype makes bacterial cells more vulnerable to the action of antimicrobials [2, 4].

Stress caused by exposure to low nitric oxide (NO) concentrations enhances cell dispersal of various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria from biofilms, without posing significant toxicity risks to humans or the environment [2, 4–8]. Despite these findings, NO influence on L. monocytogenes biofilms is not well known. This paper contributes to better understanding of cell dispersal regulation in biofilms formed by this foodborne pathogen.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains

Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115 (serotype 4b) and L. monocytogenes IAL 633 (serotype 1/2a) were acquired from Adolfo Lutz Institute (São Paulo, Brazil) and kept as glycerol stocks in brain heart infusion broth (BHI, Oxoid, UK) at − 80 °C. Working cultures were grown in BHI broth (37 °C, 24 h) as needed.

L. monocytogenes biofilm growth

Two different surfaces were used for L. monocytogenes biofilm growth: system A (stainless steel) and system B (special glass for microscopic observations). For system A, stainless steel coupons (AISI-304, 2.45 cm2) were cleaned and sterilized according to Winkelströter et al. [9], and one coupon was placed per well of a polystyrene microtiter plate (24-wells, Costar®, USA). As described by Silva et al. [10], the wells were filled with 2 mL of overnight L. monocytogenes BHI broth culture (ca. 108 CFU/mL) and incubated without shaking (25 °C, 3 h) to favor bacterial attachment [11]. After adhesion, the coupons were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), to remove non-adherent cells, and transferred to another plate. Then, fresh BHI broth was added to the wells for re-incubation (25 °C, 120 rpm, 4 days). On the fourth day, the procedure was repeated, and the biofilms were re-incubated for up to 8 days.

For system B, aliquots of overnight L. monocytogenes BHI broth culture (0.5 mL) were transferred to a chambered coverglass (Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II 8, Nagle Nunc Int., USA) and statically incubated at 25 °C. After initial adhesion (3 h), loose cells were removed by rinsing the glass surface with PBS, fresh BHI broth was added, and the culture was re-incubated for up to 4 days. The procedure for planktonic cell removal was repeated, and the biofilm culture was further incubated (for up to 8 days). No shaking was applied to this system because, although the glass chamber was appropriate for confocal laser scanning microscopy, it was very delicate and could break with agitation.

In situ detection of ROI and RNI in biofilms of L. monocytogenes

To detect ROI stress markers in biofilms, the chemicals hydroethidine (HEt), and 5-(6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) were used to stain superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide, respectively. Regarding RNI stress markers, NO was detected with 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′difluorescein diacetate (DAFFM-DA), and peroxynitrite was stained with dihydrorhodamine 1,2,3 (DHR). All fluorescent reagents were acquired from Molecular Probes (USA), and the staining procedure was conducted according to Barraud et al. [5].

Stained L. monocytogenes biofilms (systems A and B) were observed under the microscope. Biofilms on stainless steel coupons (system A) were observed under an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon model 80i, Japan) equipped with filters B-2A (450–490 nm) and G-2A (510–560 nm), and images were treated with the software NIS-Elements AR 3.2. Biofilms on glass chambers (system B) were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP5-AOBS) equipped with argon (488 nm) and helium (543 nm) lasers, coupled to the image documentation software Leica LAS AF version 2.6.0 build 7266 (Germany).

NO donor and inhibitor putative effects on L. monocytogenes biofilms

To evaluate the possible impact of NO supply or limitation on biofilms of L. monocytogenes, the classical NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was chosen; the NO inhibitors Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME) and 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide potassium salt (c-PTIO) were also employed. All these reagents were all supplied by Sigma (USA), and the selected concentrations were based on minimum inhibitory concentration tests [12] and literature data available for other bacteria [13].

L. monocytogenes biofilms grown on coupons (system A) were harvested (days 4 and 8) and treated (at 25 °C, for 1 h) with SNP (100 μg mL−1 or 2000 μg mL−1), L-NAME (100 μM), or c-PTIO (100 μM) solution. L. monocytogenes sessile populations from the coupons were enumerated by drop plating [11] on BHI agar (CFU cm−2) according to Leriche and Carpentier [14]. Free-floating L. monocytogenes cells remaining from system A were also treated with SNP (2000 μg mL−1), L-NAME (100 μM), or c-PTIO (100 μM) solutions at 25 °C for 1 h and used for quantitative gene transcription evaluation, as described in the next section.

Effect of NO donors and inhibitors on key gene transcription in L. monocytogenes

For system A, treated free-floating L. monocytogenes cell viability was checked by enumeration on BHI agar plates and the results were recorded as colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU mL−1). Moreover, total RNA was extracted from these cells, to evaluate putative changes in gene transcription.

RNA was extracted with Tri-Reagent® (Zymo Research, USA), and extracts were treated with the kit DNase I, RNase-free (Thermo Scientific, UK) combined with phenol-chloroform extraction to eliminate DNA contamination [15, 16]. The RNA extracts were quantified, checked for purity (Nanodrop® 2000 spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific, USA), and used as templates for cDNA synthesis (High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit containing RNase inhibitor, Applied Biosystems, USA).

RNA transcripts were quantified by real-time PCR (qPCR) by using the primers listed in Table 1, all acquired from Invitrogen (USA). The qPCR reaction (10 μl) included 2 μL of cDNA extract, 5 μL of iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA), 2 μL of molecular biology-grade water, and 0.5 μL of each primer solution (0.5 μM). PCR was amplified and amplicons were detected with thermocycler Mini-Opticon® (Bio-Rad, EUA); the detection threshold was set at 0.014. For all the tested genes (Table 1), there was an initial denaturation step (95 °C, 15 min) followed by 40 denaturation (95 °C, 15 s), annealing (59 °C, 30 s), and extension (72 °C, 30 s) cycles. The exception was lmo1485, which required annealing at 56 °C for 30 s.

Table 1.

Primers used to quantify gene transcription in Listeria monocytogenes related to tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stresses

| Gene | Function | Primers | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S-rRNA | Endogenous control for PCR reactions | F: GATGCATAGCCGACCTGAGA | Werbrouck et al. [17] |

| R: TGCTCCGTCAGACTTTCGTC | |||

| PrfA | Transcriptional activator factor | F: CAATGGGATCCACAAGAATATTGTAT | Werbrouck et al. [17] |

| R: GATGGTCCCGTTCTCICTAA | |||

| lmo0807 | Tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stresses | F: CACTATGAAGTAGGTTGTATCG | Mraheil et al. [18] |

| R: ATCGAATTCTTCCTCCGTTTC | |||

| lmo0990 | Tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stresses | F: TTATTGTGCTCTTGCTTTCGAG | Mraheil et al. [18] |

| R: CAGTCCTGTAAATCCACTGAAA | |||

| lmo1485 | Tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stresses | F: CGCATTTAGAACCAAATGG | Mraheil et al. [18] |

| R: CGATGGAGTGTGGATGTT |

To calculate relative gene transcription levels, normalization was performed with 16S rRNA as the reference gene, according to the 2-∆∆CT method described by Livak and Schmittgen [19]. Results are expressed as arbitrary units.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of variance of the results obtained during culture and qPCR experiments were accomplished by one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post-test. For significant differences, a value of P < 0.05 was considered. The software GraphPad Prism 5 (USA) was used for statistics.

Results

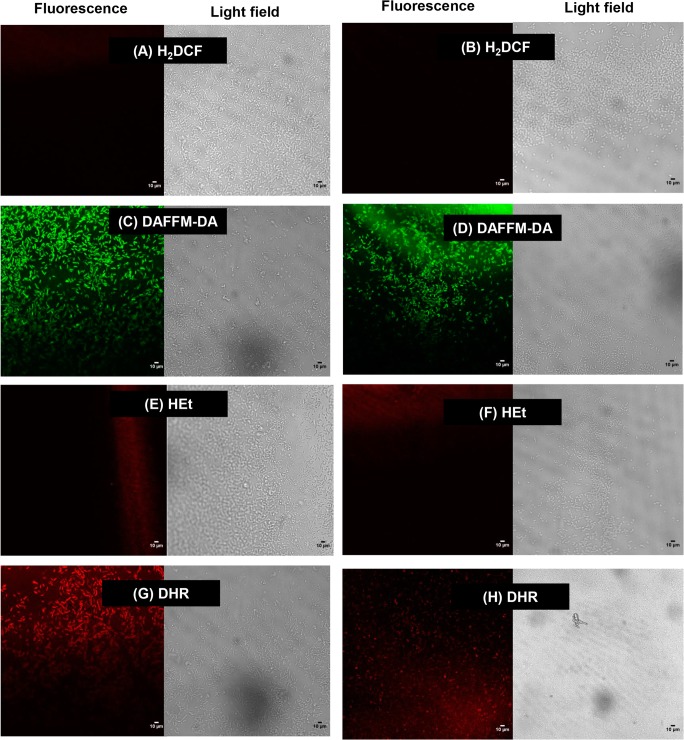

Reactive oxygen intermediates were present in biofilms grown on stainless steel coupons—system A, according to results of fluorescence microscopy observations (data not shown). However, ROI were not detected in biofilms grown on glass—system B, according to CLSM results from Fig. 1, which show there was no fluorescence for hydrogen peroxide staining (a and b), and the staining for superoxide radicals (e and f) was fading. Reactive nitrogen intermediates were naturally present in biofilm cultures of both L. monocytogenes strains tested on stainless steel coupons (system A), as indicated by specific staining combined with fluorescence microscopy observations (data not shown). CLSM results from system B (glass chamber) confirmed that NO and peroxynitrite were present in L. monocytogenes biofilms, as illustrated in Fig. 1c, d, g, h. In bright field, cell density was high. Also, there were green and red fluorescent cells, which indicated the presence of NO and peroxynitrite, respectively.

Fig. 1.

a–h Confocal laser scanning micrographs of 8-day-old biofilms of L. monocytogenes IAL633 and L. monocytogenes ATCC19115 grown on glass chamber—system B. Images were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5-AOBS microscope, equipped with argon (488 nm) and helium (543 nm) lasers. Results were documented with the software Leica LAS AF version 2.6.0 build 7266. Bright light micrographs were included to show that bacterial cells were present in the fields selected, regardless of specific stainings. Staining for hydrogen peroxide was done with H2DCF (red fluorescence would indicate positive results); nitric oxide was detected with DAFFM-DA (green fluorescence would indicate positive results); staining for superoxide radicals was done with HEt (red fluorescence would indicate positive results); and peroxynitrite was detected with DHR (red fluorescence would indicate positive results). Scale bar = 10 μm

Experiments done in system A to investigate the putative effects of RNI on Listeria monocytogenes (8-day-old biofilms and free-floating cells) viability revealed similar bacterial counts (ca. 10 [5]–106 CFU/cm2 for sessile population and ca. 109 CFU/mL for free-floating cells) irrespective of external NO donor (SNP) and NO inhibitor (L-NAME and C-PTIO) supply.

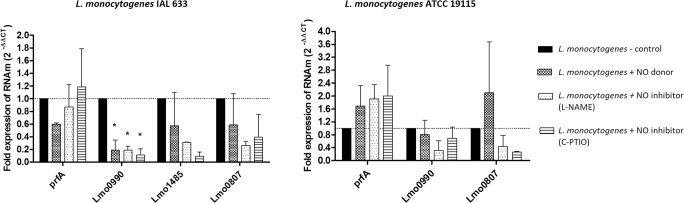

With regard to investigation into the transcription levels of genes previously reported to underlie bacterial tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stresses, external NO donor and NO inhibitor supply did not affect any of the studied L. monocytogenes strains (Fig. 2). The exception was gene lmo0990, which was downregulated in all the tested conditions as compared to untreated control.

Fig. 2.

Relative gene transcription levels normalized with reference to 16S rRNA (arbitrary units) for free-floating L. monocytogenes cells detached from biofilms (system A—stainless steel coupon, brain heart infusion broth, 8 days of incubation, 25 °C). Treatments were done for 1 h at 25 °C: NO donor (SNP at 2000 μg ml−1) or NO inhibitors (L-NAME and c-PTIO, each one at 100 μM). Dotted lines indicate the expression rate of 1 (no change in comparison with the untreated control) and P < 0.05 was considered for evaluation of statistically significant difference

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, possible ROI and RNI effects on L. monocytogenes biofilms have not been reported yet. However, these molecules have been detected in biofilms formed by other bacterial genera [5, 8]. Here, ROI was only present in L. monocytogenes biofilms grown on stainless steel (Fig. 1). This divergence could at least be partially explained by different aeration in systems A and B: for practical reasons, only the stainless steel coupons were agitated; the appropriate glass chamber for CLSM was too fragile for agitation. Nevertheless, mild oxidative stress might not have affected L. monocytogenes because catalase, a H2O2-degrading enzyme, can be produced by this bacterium [20].

On the other hand, RNI were detected in L. monocytogenes biofilms formed under all the tested conditions, as demonstrated by microscopy observations with specific staining for NO and peroxynitrite (Fig. 1). By comparing the images obtained under different light sources, it was possible to conclude that NO and peroxynitrite were not evenly distributed in the biofilms, which presented honeycomb-like structures with strongly fluorescent cells at the hollow border. This indicated the potential for cell dispersal from these microstructures. This kind of structural biofilm arrangement has been related to improved mechanical stability and nutrient flow, conferring fitness advantages to cells [1, 21].

Nitric oxide is generally produced by bacterial metabolism through the enzyme NO synthase (NOS), which occurs in several Gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus. For these bacteria, NOS activity has been shown to influence antibiotic resistance patterns and virulence factor expression and to favor escape from host immune system oxidative burst. [13, 22]

Notwithstanding the NOS importance for bacterial survival and virulence, there are no literature data on the presence of NO synthase or NO production in L. monocytogenes. However, even in the absence of NOS activity, bacterial cells have been demonstrated to produce NO by alternative pathways by using arginine as precursor [23, 24]. Although this was not investigated in the present study, it is plausible to suppose that L. monocytogenes has NO synthase-independent ability to generate NO. In fact, Joseph and Goebel [25] reported that L. monocytogenes contains the enzyme arginine deiminase, which catalyzes arginine degradation to the possible NO precursors ammonia and citrulline.

Moreover, to corroborate the absence of NO inhibitory effect on L. monocytogenes, Cole et al. [26] studied intracellular L. monocytogenes survival in vivo, to find that the NO produced by macrophages increased pathogenic bacterium escape from phagolysosomes, thereby promoting systemic infection.

With regard to peroxynitrite, no data was found on its production by L. monocytogenes but it has been reported as a bacterial metabolite synthesized via NO oxidation in the presence of ROI [7]. Our present findings regarding peroxynitrite detection in bacterial biofilms are also supported by the paper of Barraud et al. [5], who detected peroxynitrite in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms.

In this research, experiments supplying NO donor and inhibitors were carried out to elucidate whether RNI interfered in L. monocytogenes growth and biofilm formation. The classical NO donor SNP was used. Two NO inhibitors that act through distinct mechanisms were chosen: L-NAME, a NO synthase inhibitor, and c-PTIO, a NO scavenger [22, 27].

The NO donor (SNP) did not influence L. monocytogenes populations or biofilm structure. This contradicted literature reports on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Clostridium sporogenes biofilms, which are likely inhibited by the nitrosyl agent action on the bacterial cell wall. [27, 28] Additionally, many authors examined NO effects on other bacterial biofilms, to find that different NO donors increased cell dispersal and/or reduced biofilm formation even after exposure for a short time (1 h) [2, 5–7, 22]. Here, L. monocytogenes treatment with L-NAME or c-PTIO, which are NO inhibitors, did not affect bacterial cell viability.

Overall, neither NO donor nor NO inhibitors impacted transcription of selected genes in any of the studied L. monocytogenes strains. The exception was lmo0990, which was downregulated in L. monocytogenes IAL 633 (Fig. 2). The evaluated genes are considered key to counterbalancing oxidative and nitrosative stresses: lmo0990 codifies a product similar to a multidrug efflux pump; lmo0807 is homologous to the ABC complex transporter; and lmo 1485 participates in DNA methylation [24]. Taken together, our results are intriguing because they suggest that NO concentration does not directly impact L. monocytogenes biofilm formation or dispersal, which indicates that this foodborne pathogen has fine metabolic tuning to tolerate nitrosative and oxidative stress conditions.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: FBRT, NC, and LPS. Data analysis and interpretation: ECPDM. Manuscript drafting: FBRT, VFA, and ECPDM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: VFA and ECPDM.

Funding information

FBR received a Ph.D. fellowship from São Paulo Research Foundation (Process 2010/10051-3). The authors are grateful to São Paulo Research Foundation for a Research Grant (Process 2011/07062-6) to ECPDM and to the Multiuser Laboratory of Confocal Microscopy - FMRP-USP (Process 2004/08868-0). This study was partially funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Codes 001.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Silva EP, De Martinis ECP. Current knowledge and perspectives on biofilm formation: the case of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:957–968. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4611-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barraud N, Storey MV, Moore ZP, Webb JS, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Nitric oxide-mediated dispersal in single- and multi-species biofilms of clinically and industrially relevant microorganisms. Microb Biotechnol. 2009;2:370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watnick P, Kolter R. Biofilm, city of microbes. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(10):2675–2679. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2675-2679.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougald D, Rice SA, Barraud N, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. Should we stay or should we go: mechanisms and ecological consequences for biofilm dispersal. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:39–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barraud N, Hassett DJ, Hwang SH, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S, Webb JS. Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7344–7353. doi: 10.1128/JB.00779-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barraud N, Schleheck D, Klebensberger J, Webb JS, Hassett DJ, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Nitric oxide signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms mediates phosphodiesterase activity, decreased cyclic Di-GMP levels, and enhanced dispersal. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7333–7342. doi: 10.1128/JB.00975-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marvasi M, Chen C, Carrazana M, Durie IA, Teplitski M. Systematic analysis of the ability of nitric oxide donors to dislodge biofilms formed by Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157:H7. AMB Express. 2014;4:42. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb JS, Givskov M, Kjelleberg S. Bacterial biofilms: prokaryotic adventures in multicellularity. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkelströter LK, Gomes BC, Thomaz MRS, Souza VM, De Martinis ECP. Lactobacillus sakei 1 and its bacteriocin influence adhesion of Listeria monocytogenes on stainless steel surface. Food Control. 2011;22:1404–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva S, Teixeira P, Oliveira R, Azeredo J. Adhesion to and viability of Listeria monocytogenes on food contact surfaces. J Food Prot. 2008;71:1379–1385. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-71.7.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chae MS, Schraft H. Comparative evaluation of adhesion and biofilm formation of different Listeria monocytogenes strains. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;62:103–111. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.[CLSI] Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved Standard – 6th Edition. 2003. http://www.anvisa.gov.br/servicosaude/manuais/clsi/clsi_OPASM7_A6.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2014

- 13.Shatalin K, Gusarov I, Avetissova E, Shatalina Y, McQuade LE, Lippard SJ, Nudler E. Bacillus anthracis-derived nitric oxide is essential for pathogen virulence and survival in macrophages. PNAS. 2008;105:1009–1013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710950105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leriche V, Carpentier B. Viable but nonculturable Salmonella typhimurium in single- and binary-species biofilms in response to chlorine treatment. J Food Prot. 1995;58:1186–1191. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.11.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol:chloroform. CSH Protoc. 2006;2006:pdb.prot4455. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sue D, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. σB-dependent expression patterns of compatible solute transporter genes opuCA and lmo1421 and the conjugated bile salt hydrolase gene bsh in Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiol. 2003;149:3247–3256. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26526-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werbrouck H, Vermeulen A, Coillie EV, Messens W, Herman L, Devlieghere F, Uyttendaele M. Influence of acid stress on survival, expression of virulence genes and invasion capacity into Caco-2 cells of Listeria monocytogenes strains of different origins. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;134:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mraheil MA, Billion A, Mohamed W, Rawool D, Hain T, Chakraborty T. Adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes to oxidative and nitrosative stress in IFN-γ-activated macrophages. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert KC, Foster SJ. Starvation survival in Listeria monocytogenes: characterization of the response and the role of known and novel components. Microbiol. 2001;147:2275–2284. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reis-Teixeira FBD, Alves VF, De Martinis ECP. Growth, viability and architecture of biofilms of Listeria monocytogenes formed on abiotic surfaces. Braz J Microbiol. 2017;48(3):587–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber F, Beutler M, Enning D, Lamprecht-Grandio M, Zafra O, González-Pastor JE, de Beer D. The role of nitric-oxide-synthase-derived nitric oxide in multicellular traits of Bacillus subtilis 3610: biofilm formation, swarming, and dispersal. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:111–121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudhamsu J, Crane BR. Bacterial nitric oxide synthase: what are they good for? Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei Y, Zhou H, Sun Y, He Y, Luo Y. Insight into the catalytic mechanism of arginine deiminase: functional studies on the crucial sites. Proteins: Struct Func Bioinf. 2007;66:740–750. doi: 10.1002/prot.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph B, Goebel W. Life of Listeria monocytogenes in the host cells’ cytosol. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole C, Thomas S, Filak H, Henson PM, Lenz LL. Nitric oxide increases susceptibility of toll-like receptor-activated macrophages to spreading Listeria monocytogenes. Immunity. 2012;36:807–820. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaitseva J, Granik V, Belik A, Koksharova O, Khmel I. Effect of nitrofurans and NO generators on biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and Burkholderia cenocepacia 370. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joannou CL, Cui XY, Rogers N, Vielotte N, Martinez CLT, Vugman NV, Hughes MN, Cammack R. Characterization of the bactericidal effects of sodium nitroprusside and other pentacyanonitrosyl complexes on the food spoilage bacterium Clostridium sporogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3195–3201. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3195-3201.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]