Abstract

Ozone has a broad antimicrobial spectrum and each microorganism species has inherent sensitivity to the gas. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of ozone gas on Escherichia coli O157:H7 inoculated on an organic substrate, and the efficacy of ozonated water in controlling the pathogen. For the first experiment, E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC® 43890™) was inoculated in milk with different compositions and in water, which was ozonated at concentrations of 35 and 45 mg L−1 for 0, 5, 15, and 25 min. In the second experiment, water was ozonated at 45 mg L−1 for 15 min. E. coli O157:H7 was exposed for 5 min to the ozonated water immediately after ozonation, and after storage for 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 3.0, and 24 h at 8 °C. The results showed that the composition of the organic substrate interfered with the action of ozone on E. coli O157:H7. In lactose-free homogenized skim milk, reductions of 1.5 log cycles were obtained for ozonation periods of 25 min at the concentrations tested. Ozonated water was effective in inactivating of E. coli O157:H7 in all treatments. The efficiency of ozone on E. coli O157:H7 is influenced by the composition of the organic substrates, reinforcing the need for adequate removal of organic matter before sanitization. Furthermore, refrigerated ozonated water stored for up to 24 h is effective in the control of E. coli O157:H7.

Keywords: Milk, Ozone gas, Ozonated water, Inactivation of microorganisms

Introduction

The ability of microorganisms to survive or multiply depends on a number of factors, including those related to the characteristics of the substrates on which the microorganisms are inserted, called intrinsic factors, such as water activity, and those related to the environment which are called extrinsic factors, such as ambient temperature [1]. One of the major concerns of the food industry is guarantee of the microbiological quality of its products, seeking to reduce losses resulting from deterioration and reducing risks to consumer health [2].

The genus Escherichia belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae and includes E. coli, E. blattae, E. fergusonii, E. hermannii, E. vulneris, E. albertii, and E. senegalensis [3]. It is believed that most E. coli serotypes are devoid of any virulence factor; however, during the evolutionary process, some strains acquired different sets of genes that gave them the ability to cause diseases, a fact that determines the great pathogenic versatility of the species [4]. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) are also called verotoxigenic or verotoxin-producing E. coli (VTEC) and make up an important group of emerging foodborne pathogens [5, 6]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most outbreaks caused by E. coli O157:H7 have mainly been related to the consumption of undercooked ground beef [7]. However, currently, outbreaks involving non-meat foods such as milk and its unpasteurized derivatives, unpasteurized fruit juices, lettuce, spinach, raw vegetables, and seed sprouts have also been reported [8–10].

Among the sanitizers used in the food industry, chlorine and chlorinated compounds predominate [11, 12]. The ease of use, low cost, antimicrobial activity, and complete dissolution in water makes chlorinated agents frequently used as sanitizers in the food industry [13, 14]. However, chlorine is a corrosive substance that can cause skin and respiratory tract irritation [15]. Furthermore, another concern with the use of chlorine is associated with the possibility of hyperchlorination of residual water, which together with the high organic carbon content may result in high concentrations of trihalomethanes and other disinfection byproducts [13, 16].

Considering the importance of the sanitization step, the study of alternative methods and/or agents should receive special attention and ozone is an option that can be used with different objectives. This technology associated with sanitizers allows for a greater reduction of microbial contamination of foods [17, 18]. In 2001, FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) approved the use of ozone as an antimicrobial agent in food, both in the gas phase and dissolved in water [19]. As a sanitizer, ozone first acts on the cell membrane, reacting with glycoproteins, glycolipids, and nucleic acids. Microorganisms are inactivated by disruption of the cell as a result of the action of molecular ozone or free radicals during decomposition of the gas [20–22]. Although ozone inactivates several microorganisms, studies are still needed to elucidate its efficacy on the elimination of E. coli O157:H7, in addition to determination of the most appropriate concentration and form of application. Thus, the aims of this study were (i) to assess the effects of direct application of ozone gas on E. coli O157:H7 inoculated in organic substrates and (ii) to evaluate the efficacy of ozonated water in controlling the pathogen.

Material and methods

Experiment I

The strain used was E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC® 43890™). Prior to each inoculation, the strain that was stored in MRS broth (Oxoid) added to glycerol at 30% at − 20 °C was recovered in Tryptone Soy Broth with 0.6% of Yeast Extract (TSB-YE) (Bacto™) with incubation at 35 °C for 24 h. The strain was plated on Tryptone Soy Agar supplemented with 0.6% of Yeast Extract (TSA-YE) (Kasvi®) where it was again incubated at 35 °C for 24 h.

The organic substrates used were as follows: unhomogenized whole milk (UHWM), homogenized whole milk (HWM), skim milk (SM), lactose-free skim milk (LFSM), and lactose-free whole milk (LFWM), obtained from commercial establishments, which were sterilized by boiling in the laboratory to ensure the elimination of any other microorganisms and cooled before inoculation. Milk was used only as a substrate, considering the differences in fat and lactose contents. All procedures were also conducted in distilled water for comparison.

Colonies developed on TSA-YE were inoculated in 0.85% saline solution until obtaining the degree of turbidity corresponding to tube 1 of the McFarland nephelometric scale (Nefelobac®, Probac do Brasil), containing approximately 3.0 × 108 CFU mL−1. From this inoculum, 9.0 mL was transferred to a volumetric flask containing 91 mL of each substrate, obtaining approximately 106 CFU mL−1; then, 3.0 mL was inoculated in 297 mL of the substrate in order to obtain approximately 104 CFU mL−1 (parent inoculum).

For gas generation, the ozone generator Model O&L 3.0-O2-RM (Ozone & Life, Sao Jose dos Campos, São Paulo, Brazil) was used, with a flow rate of 0.5 L min−1 at the temperature of 20 °C. The ozone concentration was determined as recommended by Clescerl, Greenberg, and Eaton [23]. For ozonation, each sample was initially transferred from the substrates into a glass column, with a 500-mL capacity. Before the ozonation of each sample, the glass column was sanitized with bubbling of the ozone gas itself in water for 5 min. Based on results obtained by Couto et al. [24], the concentrations of ozone gas of 35 and 45 mg L−1 were applied at 0, 5, 15, and 25 min with three repetitions each for the microorganism. The residual ozone concentrations were determined after passage through the glass column containing the different substrates.

Experiment II

E. coli O157:H7 colonies grown on TSA-YE were inoculated in a 0.85% saline solution to obtain the degree of turbidity corresponding to tube 1 of the McFarland nephelometric scale (Nefelobac®, Probac do Brasil), containing approximately 3.0 × 108 CFU mL−1. From this inoculum, 1.0 mL was withdrawn and serial decimal dilutions were performed in the 0.85% saline solution until obtaining the inoculum with approximately 104 CFU mL−1 (parent inoculum).

Ozone gas was obtained as described in the “Experiment I” section. To obtain ozonated water, 2 L of autoclaved distilled water was used. The water was transferred to a glass column and ozonated at a concentration of ozone gas of 45 mg L−1 for 15 min. After ozonation, the water was maintained under refrigeration at 8 ± 1 °C. The storage periods of the ozonated water were 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 3.0, and 24 h. After each storage period, 9.0 mL of ozonated water was pipetted into sterile test tubes. Then, 1.0 mL of the inoculum (104 CFU mL−1) was added. The contact time of the inoculum with the ozonated distilled water was 5 min. It is emphasized that by adding 1 mL of 0.85% saline solution to 9.0 mL of ozonated distilled water, the electrical conductivity of the solution was 1.1 mS cm−1.

Quantification of ozone dissolved in water was performed in a photometer, Model I-2019 (CHEMetrics, Inc., Midland, VA, USA), with a measurement range of 0.2 to 5.0 mg L−1.

Microbiological analyses

The counts of E. coli O157:H7 were performed by plating 0.1 mL on the surface of Violet Red Bile agar (VRB) (Acumedia®), with incubation at 35 °C for 24 h. Results of the counts were converted to log10.

Experimental design

In the “Experiment I” section, a completely randomized design was used in a 2 × 6 × 4 factorial scheme, consisting of two ozone concentrations (35 and 45 mg L−1), six substrates (UHWM, HWM, SM, LFSM, LFWM, and water), and four gas exposure periods (0, 5, 15, and 25 min), where three replicates were conducted for each assay. An analysis of variance was performed at 5% probability using the ASSISTAT 7.7 BET software (Federal University of Campina Grande, Brazil). Subsequently, a mean test was performed using the Tukey test at 5% probability or regression analysis. The regression analysis was adopted when the effect of the ozonation period was evaluated. The SigmaPlot v.10 (Systat Software Inc., Germany) was used to obtain the regression equations and to plot the graphs. In the “Experiment II” section, in which the efficacy of ozonated water on the control of E. coli O157:H7 was evaluated, only the ozonated water storage period was varied (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 3.0, and 24 h). Descriptive statistics were used in the presentation and analysis of the data.

Results

There was a significant variation (p < 0.01) in the reduction of E. coli O157:H7 counts as a result of the triple interaction between ozone concentration, substrate, and gas exposure period. Table 1 shows the mean values for the reduction in E. coli O157:H7 counts in log cycles, when different combinations of substrates and ozone exposure periods were evaluated as a function of gas concentration. There was no significant increase (p > 0.05) in the reduction of E. coli O157:H7 counts with the increase in ozone concentration, except in the LFWM substrate combined with the 5-min ozonation period.

Table 1.

Mean values for the reduction in Escherichia coli O157:H7 counts (log N0/N) in different combinations of substrate (S) and exposure period (P) at ozone concentrations (C) of 35 and 45 mg L−1

| S × P (min) | C (mg L−1) | S × P (min) | C (mg L−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 45 | 35 | 45 | ||

| UHWM/5 | 0.24 ± 0.04a | 0.26 ± 0.06a | LFSM/5 | 0.66 ± 0.12a | 0.78 ± 0.09a |

| UHWM /15 | 0.38 ± 0.10a | 0.41 ± 0.11a | LFSM/15 | 0.82 ± 0.23a | 0.86 ± 0.07a |

| UHWM /25 | 0.89 ± 0.17a | 0.96 ± 0.31a | LFSM/25 | 1.53 ± 0.34a | 1.54 ± 0.23a |

| HWM/5 | 0.23 ± 0.02a | 0.23 ± 0.04a | LFWM/5 | 0.27 ± 0.02b | 0.46 ± 0.09a |

| HWM/15 | 0.20 ± 0.04a | 0.30 ± 0.05a | LFWM/15 | 0.44 ± 0.07a | 0.56 ± 0.02a |

| HWM/25 | 0.29 ± 0.06a | 0.38 ± 0.09a | LFWM/25 | 0.65 ± 0.17a | 0.73 ± 0.06a |

| SM/5 | 0.02 ± 0.07a | 0.01 ± 0.01a | DW/5 | 3.98 ± 0.01a | 3.95 ± 0.04a |

| SM/15 | 0.03 ± 0.04a | 0.03 ± 0.02a | DW/15 | 3.98 ± 0.01a | 3.94 ± 0.04a |

| SM/25 | 0.10 ± 0.04a | 0.11 ± 0.05a | DW/25 | 3.97 ± 0.02a | 3.90 ± 0.02a |

Means followed by the lower case letters (a–b) on the line do not statistically differ by the Tukey test at 5% probability

UHWM, unhomogenized whole milk; HWM, homogenized whole milk; SM, skim milk; LFSM, lactose-free skim milk; LFWM, lactose-free whole milk; DW, distilled water.

n = 3 sample replicates

Table 2 presents the mean values of log cycle reductions in the E. coli O157:H7 count for different combinations of ozone concentration and gas exposure periods on different substrates. There was a significant difference (p < 0.05) in all combinations of ozone concentration and gas exposure period as a function of the substrate used. Greater reductions in E. coli O157:H7 counts were obtained when using distilled water and LFSM as substrates, with mean values between 3.90 and 3.98 log cycles and between 0.66 and 1.54 log cycles, respectively. In the HWM and SM substrates, reductions in E. coli O157:H7 counts remained below 0.40 log cycles in all combinations of ozone concentration and gas exposure period.

Table 2.

Mean values for the reduction in Escherichia coli O157:H7 counts (log N0/N) in different combinations of gas concentration (C) and exposure period (P) on different substrates (S)

| C(mg L−1)/P(min) | S | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHWM | HWM | SM | LFSM | LFWM | DW | |

| 35/5 | 0.24 ± 0.04 cd | 0.23 ± 0.02 cd | 0.02 ± 0.07d | 0.66 ± 0.12b | 0.27 ± 0.02c | 3.98 ± 0.01a |

| 35/15 | 0.38 ± 0.10 cd | 0.20 ± 0.04de | 0.03 ± 0.04e | 0.82 ± 0.23b | 0.44 ± 0.07c | 3.98 ± 0.01a |

| 35/25 | 0.89 ± 0.17c | 0.29 ± 0.06d | 0.10 ± 0.04d | 1.53 ± 0.34b | 0.65 ± 0.17c | 3.97 ± 0.02a |

| 45/5 | 0.26 ± 0.06c | 0.28 ± 0.04c | 0.01 ± 0.01d | 0.78 ± 0.07b | 0.46 ± 0.09c | 3.95 ± 0.04a |

| 45/15 | 0.41 ± 0.11 cd | 0.30 ± 0.05d | 0.03 ± 0.02e | 0.86 ± 0.23b | 0.56 ± 0.02c | 3.94 ± 0.04a |

| 45/25 | 0.96 ± 0.31c | 0.38 ± 0.09d | 0.11 ± 0.05e | 1.54 ± 0.09b | 0.73 ± 0.06c | 3.90 ± 0.02a |

Means followed by the lower case letters (a–e) on the line do not statistically differ by the Tukey test at 5% probability

UHWM, unhomogenized whole milk; HWM, homogenized whole milk; SM, skim milk; LFSM, lactose-free skim milk; LFWM, lactose-free whole milk; DW, distilled water

n = 3 sample replicates

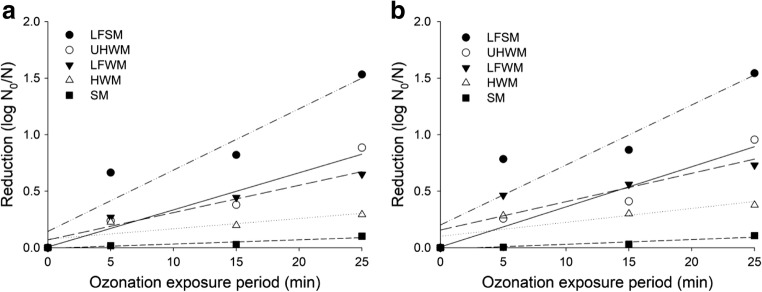

Table 3 and Fig. 1 show the regression curves referring to the reduction in E. coli O157:H7 as a result of ozonation, in the different substrates and at the concentrations of 35 and 45 mg L−1, as a function of the ozonation period. The reduction was more pronounced as the ozone exposure period increased when water was used as the substrate. It is important to note that when the ozonated substrate was water (DW), independent of the ozone concentration, a maximum detectable reduction was obtained in the E. coli O157:H7 count with 5 min of gas exposure, considering the initial inoculum. In the substrates containing organic matter, this behavior was more accentuated in the LFSM substrate. In the HWM and SM substrates, the reductions were less than 0.4 log cycles.

Table 3.

Adjusted regression equations and respective coefficients of determination (R2) to the reduction in E. coli O157:H7 (log N0/N) count as a function of the ozone exposure period (x) in different substrates (S) and in the concentrations (C) of 35 and 45 mg L−1

| C (mg L−1) | S | Adjusted equation | R 2 | SEE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | UHWM | y⌢ = 0.007 + 0.033 x | 0.95 | 0.10 |

| HWM | 0.64 | 0.09 | ||

| SM | 0.88 | 0.02 | ||

| LFSM | 0.91 | 0.23 | ||

| LFWM | 0.95 | 0.08 | ||

| DW | 0.99 | 0.01 | ||

| 45 | UHWM | y⌢ = 0.007 + 0.036x | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| HWM | 0.68 | 0.11 | ||

| SM | y⌢ = − 0.012 + 0.004x | 0.89 | 0.02 | |

| LFSM | y⌢ = 0.201 + 0.053x | 0.87 | 0.28 | |

| LFWM | 0.79 | 0.17 | ||

| DW | 0.99 | 0.01 |

UHWM, unhomogenized whole milk; HWM, homogenized whole milk; SM, skim milk; LFSM, lactose-free skim milk; LFWM, lactose-free whole milk; DW, distilled water; SEE, standard error of estimate

n = 3 sample replicates

Fig. 1.

Reduction in the Escherichia coli O157:H7 count (log N0/N) on different substrates in the concentrations of 35 mg L−1 (a) and 45 mg L−1 (b) in function of the ozone exposure period. LFSM, lactose-free skim milk; UHWM, unhomogenized whole milk; LFWM, lactose-free whole milk; HWM, homogenized whole milk; SM, skim milk

Also observed was a variation in the residual concentration of ozone gas after passage through the column containing the different substrates. The presence of organic matter caused a reduction in the residual ozone gas concentration. Highlighted were the results obtained when the substrates were unhomogenized whole milk (UHWM), homogenized whole milk (HWM), and lactose-free skim milk (LFSM). Residual concentrations of gaseous ozone at the initial concentration of 45 mg L−1 after 25 min were equivalent to approximately 36.0, 40.5, and 31.50 mg L−1 when the substrates used were UHWM, LFSM, and HWM, respectively.

Table 4 shows the values of ozone concentration dissolved in water stored at 8 °C for up to 24 h. Also presented are the water temperatures at the time of each ozone concentration measurement. The residual ozone concentration remained in the range of 1.97 to 0.82 mg L−1 during the ozonated water storage period at 8 °C. It should be noted that there was a change in temperature of the ozonated water during storage. This variation can be justified by the fact that water ozonation was carried out in an environment with a temperature of approximately 20 °C. Therefore, during this process, the water temperature increased to 14 °C. It should be noted that the temperature of the water prior to ozonation was 8 °C.

Table 4.

Mean values of dissolved ozone concentration and temperature in water stored at 8 °C for 24 h

| Variables | Stored period (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 24 | |

| Concentration (mg L−1) | 1.45 | 1.97 | 1.71 | 1.78 | 1.67 | 0.82 |

| Temperature (°C) | 14 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 8.0 |

The count of E. coli O157:H7 prior to ozonation was equivalent to 4.50 log CFU mL−1. On the other hand, the presence of the pathogen was not detected after exposure to ozonated water. This result was obtained for all ozonated water storage periods at a temperature of 8 ± 1 °C, with concentrations of dissolved ozone in the range of 0.82 to 1.97 mg L−1 (Table 4).

Discussion

Ozone has a broad antimicrobial spectrum [25] and each microorganism species has inherent sensitivity to the gas [21]. Ozonation has been tested for the control of fungi, Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, and viruses [26–28]. The inactivation of microorganisms by ozone is a process that occurs due to rupture of the cellular envelope and subsequent dispersion of the cytoplasmic constituents, since this gas has a high oxidative potential. Ozone is able to react with cellular constituents including proteins, unsaturated fatty acids, cell wall peptidoglycans, enzymes, and nucleic acids [25]. In aqueous media, the inactivation of microorganisms is attributed to molecular ozone and the hydroxyl, hydroperoxyl, and superoxide radicals, generated from their decomposition, according to Manousaridis et al. [29]

Among the factors that affect the action of ozone on microorganisms, highlighted are pH, temperature, and composition of the medium. In addition, organic compounds can compete with microorganisms for ozone [25]. This justifies the greater efficiency of microorganism inactivation by ozone in substrates with less organic matter. In organic substrates, the greatest E. coli O157:H7 inactivation efficiency was obtained in the substrate LFSM, characterized by its reduced fat and lactose contents. In this substrate, the maximum reductions in E. coli O157:H7 counts were 1.53 and 1.54 log cycles when adopting the concentrations of 35 and 45 mg L−1 for 25 min, respectfully. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Restaino et al. [30], who evaluated the efficacy of ozone for inactivating Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, yeasts, and fungi in water with or without starch and bovine serum albumin. Güzel-Seydim et al. [31] studied the effect of the presence of fat, proteins, and carbohydrates on the inactivation of Bacillus stearothermophilus, E. coli, and S. aureus by ozone. The constituents presenting the greatest protective effect on the microorganisms were cream of milk and caseinate. Similar results were obtained by Choi et al. [32] for apple juice with different soluble solids contents. Ozone was able to inactivate E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes, but the efficacy of ozonation was dependent on the soluble solids content in apple juice.

Another factor that affects the efficiency of ozone on microorganisms is the effect of organic compounds present on decomposition of the gas. Ozone is noted for being unstable both in the gas phase and when dissolved in water [29]. In distilled water, the half-life of ozone at 20 °C is in the range of 20 to 30 min [25]. In media rich in organic matter, faster decomposition of the ozone and consequently reduced effectiveness of microorganism inactivation are expected. Beltrán [33] affirmed that initially in an aqueous medium containing organic matter, there is a rapid consumption of ozone. As degradation of organic compounds occurs, ozone decomposition becomes slower. In the present work, the rapid decomposition of ozone in substrates rich in organic matter justifies the reduced efficacy of the gas for inactivation of microorganisms.

A significant difference was observed in inactivation of E. coli O157:H7 when comparing the effect of ozone on the UHWM and HWM substrates, at concentrations of 35 and 45 mg L−1 and 25 min exposure period. In the UHWM substrate, reductions equivalent to 0.86 and 0.96 log cycle were obtained, for concentrations of 35 and 45 mg L−1, respectively, while in the HWM substrate, the reductions were 0.29 and 0.39 log cycle for concentrations of 35 and 45 mg L−1, respectively. These differences may be attributed to the size difference of fat globules in the substrates. The HWM substrate is equivalent to homogenized milk, which results in the reduction of fat globule size and consequently an increase in the surface area [34]. The UHWM substrate that was not homogenized presents larger fat globules [35]. It is therefore possible that the greater surface area of the fat globules in the HWM substrate caused a more rapid degradation of the dissolved ozone, which justifies the less effective inactivation of E. coli O157:H7. Highlighted are the observed results regarding ozone concentration after passage through the column containing the substrates. When HWM was used, a lower residual concentration was obtained when compared to UHWM. A lower residual concentration is directly related to greater reactivity of the medium.

The ozonated water used in the control of E. coli O157:H7 demonstrated a high efficiency of microorganism inactivation, even after storage for 24 h at a temperature of 8 °C ± 1. Several studies have been found in literature that indicate the effectiveness of ozonated water for control of important microorganisms with regard to food conservation and safety. Mari et al. [36] observed in their study with pears that spore germination of the deteriorating fungi Penicillium expansum, Botrytis cinerea, and Mucor piriformis was inhibited by treatment with ozonated water at the concentrations of 0.99 to 0.4 mg L−1 for 5 min at 20 °C. Beltrán et al. [37] evaluated the effect of ozonated water on maintaining lettuce quality and indicated that ozone may be an alternative to chlorine for product conservation. Inatsu et al. [38] tested ozonated water as an antimicrobial agent for the in vitro control of several bacterial species, including E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The authors obtained a reduction of 7.4 log cycles in the counts of E. coli O157:H7 for an exposure time of 3.0 min and a concentration of dissolved ozone in water of 5.44 mg L−1, at a temperature of 25 °C. Cavalcante et al. [19] tested ozonated water for the control of E. coli O157:H7 and B. subtilis, and observed reductions of 6.6 and 5.3 log cycles, respectively, for the ozone concentration of 1.0 mg L−1 and 1.0-min contact time. A study carried out by Tachikawa et al. [39] in which ozonated water was tested with concentrations between 0.9 and 3.2 mg L−1 and contact time between 1 and 20 min, for the disinfection and removal of biofilm from P. fluorescence and P. aeruginosa, reported that the survival rate of biofilms was 1.0% for ozone concentrations in water between 0.9 and 1.4 mg L−1 and exposure period of 5 min; however, when the dissolved ozone concentration in water increased to 3.2 mg L−1, the survival rates were 0.01 and 0.00002% for exposure periods of 5 and 20 min, respectively.

Conclusions

The direct and indirect application of ozone produced significant reductions in the counts of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (ATCC® 43890™), proving its efficiency in controlling this pathogen. The effectiveness of ozonated water confirmed in this study, where the maximum reduction was obtained under the conditions evaluated, allows for recommending its use in the cleaning processes of equipment and utensils in the food industry, as an interesting alternative to traditional sanitizers. On the other hand, the efficiency of gaseous ozone in reducing and eliminating E. coli O157:H7 is influenced by the presence of organic substrates. This behavior reinforces the need for efficient removal of organic matter in cleaning processes, prior to the use of ozone.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Franco BD, Landgraf M. Microbiologia dos alimentos. 2. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson PM, Branen AL. Food antimicrobials – an introduction. In: Davidson PM, Sofos JN, Branen AL, editors. Antimicrobials in food. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos LC, Trabulsi LR. Escherichia. In: Trabulsi LR, Alterthum F, Gompertz OF, Candeias JAN, editors. Microbiologia. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2002. pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernaki-Leffer AM, Biesdorf SM, Almeida LM, Leffer EV, Vigne F. Isolamento de enterobactérias em Alphitobius diaperinus e na cama de aviários no oeste do estado do Paraná, Brasil. Rev Bras Cienc Avic. 2002;4:243–247. doi: 10.1590/S1516-635X2002000300009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco M, Blanco JE, Mora A, Rey J, Alonso JM, Hermoso M, Hermoso J, Alonso MP, Dahbi G, Gonzalez EA, Bernardez MI, Blanco J. Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from healthy sheep in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1351–1356. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1351-1356.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pianciola L, Chinen I, Mazzeo M, Miliwebsky E, González G, Muller C. Genotypic characterization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains that cause diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome in Neuquén, Argentina. J Med Microbiol. 2014;304:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Multistate outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections linked to ground beef (final update). http://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2014/O157H7-05-14/index.html/. Accessed 20 Dec 2015

- 8.Lund BM, O'Brien SJ. Microbiological safety of food in hospitals and other healthcare settings. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng P, Weagant SD, Jinneman K (2011) BAM: diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/ucm070080.htm/. Accessed 10 Nov 2015

- 10.Liu Y, Gill A, McMullen L, Ganzle MG. Variation in heat and pressure resistance of verotoxigenic and nontoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Food Prot. 2015;78:111–120. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nascimento MS, Silva N, Catanozi MP, Silva KC. Effects of different disinfection treatments on the natural microbiota of lettuce. J Food Prot. 2003;66:1697–1700. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-66.9.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Wang H, Xu Y, Wu J, Xiao G. Effect of treatment with dimethyl dicarbonate on microorganisms and quality of chinese cabbage. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2013;76:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selma MV, Ibaneza AM, Allende A, Cantwella M, Suslow T. Effect of gaseous ozone and hot water on microbial and sensory quality of cantaloupe and potential transference of Escherichia coli O157:H7 during cutting. Food Microbiol. 2008;25:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen C, Luo Y, Nan X, et al. Enhanced inactivation of Salmonella and Pseudomonas biofilms on stainless steel by use of t-128, a fresh-produce washing aid, in chlorinated wash solutions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:6789–6798. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01094-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvaro JE, Moreno S, Dianez F, Santos M, Carrasco G, Urrestarazu M. Effects of peracetic acid disinfectant on the postharvest of some fresh vegetables. J Food Eng. 2009;95:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman SM, Jin YG, Oh DH. Combination treatment of alkaline electrolyzed water and citric acid with mild heat to ensure microbial safety, shelf-life and sensory quality of shredded carrots. Food Microbiol. 2011;28:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavalcante DA, Leite Júnior BR, Tribst AA, Cristianini M. Inativação de Escherichia coli O157:H7 e Bacillus subtilis por água ozonizada. B Cent Pesqui Proc. 2014;32:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavalcante DA, Leite Júnior BR, Tribst AA, Cristianini M. Vida de prateleira de alface americana tratada com água ozonizada. Cienc Rural. 2015;45:2089–2096. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20130952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FDA - Food and Drug Administration (2001) Secondary direct food additives permitted in food for human consumption. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2001-06-26/html/01-15963.htm/. Accessed 20 June 2018

- 20.Guzel-Seydim Z, Greene AK, Seydim AC. Use of ozone in the food industry. Food Sci Technol. 2004;37:453–460. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen PJ, Tiwari BK, O'Donnell CP, Muthukumarappan K. Modelling approaches to ozone processing of liquid foods. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2009;20:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2009.01.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Yousef AE, Dave S. Application of ozone for enhancing the microbiological safety and quality of foods: a review. J Food Prot. 1999;62:1071–1087. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-62.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clescerl LS, Greenberg AE, Eaton AD. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 20. Denver: American Water Works Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Couto EP, Alencar ER, Gonçalves VSP, Santos AJ, Ribeiro JL, Ferreira M. Effect of ozonation on the Staphylococcus aureus innoculated in milk. Semina Cienc Agrar. 2016;37:1911–1918. doi: 10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n4p1911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khadre M, Yousef AE, Kim J. Microbiological aspects of ozone applications in food: a review. J Food Sci. 2001;66:1242–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2001.tb15196.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alwi NA, Ali A. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157, Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium populations on fresh-cut bell pepper using gaseous ozone. Food Control. 2014;46:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung HJ, Song WJ, Kim KP, Ryu S, Kang DH. Combination effect of ozone and heat treatments for the inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes in apple juice. J Food Microbiol. 2014;171:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez BA, Alencar ER, Pineli LL, Ferreira WF, Roberto MA. Tracing interactions among column height, exposure time and gas concentration to dimension peanut antifungal ozonation. Food Sci Technol. 2016;65:668–675. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manousaridis G, Nerantzaki A, Paleologos EK, Tsiotsias A, Savvaidis IN, Kontominas MG. Effect of ozone on microbial, chemical and sensory attributes of shucked mussels. Food Microbiol. 2005;22:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2004.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Restaino L, Frampton E, Hemphill J, Palnikar P. Efficacy of ozonated water against various food-related microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3471–3475. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3471-3475.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Güzel-Seydim Z, Bever PI, Greene AK. Efficacy of ozone to reduce bacterial populations in the presence of food components. Food Microbiol. 2004;21:475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2003.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi MR, Liu Q, Lee SY, Jin JH, Ryu S, Kang DH. Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes in apple juice with gaseous ozone. Food Microbiol. 2012;32:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beltrán FJ. Ozone reaction kinetics for water and wastewater systems. 1. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berton A, Rouvellac S, Robert B, Rousseau F, Lopez C, Cremon I. Effect of the size and interface composition of milk fat globules on their in vitro digestion by the human pancreatic lipase: native versus homogenized milk fat globules. Food Hydrocoll. 2012;29:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graves E, Beaulieu A, Drackley J. Factors affecting the concentration of sphingomyelin in bovine milk. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:706–715. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(07)71554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mari M, Bertolini P, Pratella G. Non-conventional methods for the control of post-harvest pear diseases. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94:761–766. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beltrán D, Selma MV, Alicia M, Gil MI. Ozonated water extends the shelf life of fresh-cut lettuce. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5654–5663. doi: 10.1021/jf050359c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inatsu Y, Kitagawa T, Nakamura N, Kawasaki S (2013) Effectiveness of stable ozone microbubble containing water on reducing bacteria load on selected leafy vegetables. Acta Hortic (989):161–166

- 39.Tachikawa M, Yamanaka K, Nakamuro K. Studies on the disinfection and removal of biofilms by ozone water using an artificial microbial biofilm system. Ozone Sci Eng. 2009;31:3–9. doi: 10.1080/01919510802586566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]