Abstract

Ergosterol, a unique component of fungal cells, is not only important for fungal growth and stress responses but also holds great economic value. Limited studies have been performed on ergosterol biosynthesis in Aspergillus oryzae, a safe filamentous fungus that has been used for the manufacture of oriental fermented foods. This study revealed that the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway is conserved between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and A. oryzae 3.042 by treatment with ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors and bioinformatics analysis. However, the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in A. oryzae 3.042 is more complicated than that in S. cerevisiae as there are multiple paralogs encoding the same biosynthetic enzymes. Using RNA-seq, this study identified 138 and 104 differentially expressed genes (DEG) in response to the ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors tebuconazole and terbinafine, respectively. The results showed that the most common DEGs were transport- and metabolism-related genes. There were only 17 DEGs regulated by both tebuconazole and terbinafine treatments and there were 256 DEGs between tebuconazole and terbinafine treatments. These results provide new information on A. oryzae ergosterol biosynthesis and regulation mechanisms, which may lay the foundation for genetic modification of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in A. oryzae.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s42770-018-0026-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aspergillus oryzae, Ergosterol biosynthesis, Inhibitors, Transcriptome

Introduction

Sterols, a large group of natural macromolecule alcohol compounds, are key components of the cell membrane of animals, plants, and fungi [1, 2]. Ergosterol is specific for fungal cell membranes and has been widely used as a marker to assess fungal biomass [3]. As ergosterol is an important cell membrane component that affects fluidity and permeability, and it plays important roles in fungal growth, reproduction, and stress tolerance [4]. Furthermore, ergosterol is also a very important pharmaceutical raw material, which can be used for cortisone and progesterone production, and can be used as a precursor of vitamin D2 synthesis [5]. Recently, new functions of steroid drugs have been revealed, for example tetrahydroxosterol has a significant anti-tumor activity, and some anti-HIV compounds have similar structures to ergosterol [6]. Steroids have important physiological activities, have been widely used in clinical practice, and are the second most widely used drugs after antibiotics [5].

Research on yeast and other fungi has provided great progress in understanding the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. This pathway is a complex process, which involves about 18 reactions and 24 enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the detailed process of ergosterol biosynthesis pathway has been researched and reviewed in detail [7–10]. As ergosterol is a unique component of fungal cells, several studies have reported a range of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors. On one hand, these inhibitors can be used as fungicides in agriculture and medicine [11]. On the other hand, these inhibitors provide a very important tool for the study of ergosterol synthesis, metabolism, and regulation. Currently, most antifungal agents are inhibitors of essential enzymes in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, which can inhibit the biosynthesis of ergosterol by competitively binding to key enzymes, resulting in destruction of the cell membrane and inhibition of fungal growth and reproduction [12]. Ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors are of four main types. The first type is C-14α-demethylase inhibitors, most commonly used in fungicides and these compounds are mainly imidazoles (azoles) that inhibit the activity of ERG11 (CYP51), blocking ergosterol biosynthesis [13]. The second type includes Δ8 → Δ7 isomerase or Δ [14] reductase inhibitors, including morpholines and fenpropimorphs, which can competitively inhibit the activities of these two enzymes and thereby inhibit ergosterol synthesis. The main target of these drugs is ERG24 [13]. The third type includes squalene cyclooxygenase (ERG1) inhibitors, including acrylamide compounds [14]. On one hand, these inhibitors can cause fungal ergosterol deficiency, but on the other hand, they can cause squalene accumulation in the plasma membrane, leading to increased fragility of the plasma membrane and resulting in the destruction of cell membrane structure and function [15]. The last type includes Δ5(6) desaturase inhibitors, which can competitively bind to oxidized sterol intermediates to inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis [14]. This inhibition can cause accumulation of Δ7,22E-ergosterol precursors, resulting in a decrease in cell membrane stability. A lack of ergosterol can cause cells to synthesize ergosterol de novo by a negative feedback mechanism, generating large amounts of Δ7, 22E-ergosterol precursors that further inhibit cell growth [16].

Aspergillus oryzae (koji mold) is a safe filamentous fungus that has been used in the manufacture of oriental fermented foods such as sauce, miso, and sake for thousands of years. It is also commercially used for valuable enzyme production. The first sequenced genome of A. oryzae is of the starin RIB40, which is mainly used in Japan [17], and the sequencing of the A. oryzae 3.042 (mainly used in China) genome has also been completed [18]. Although the genome sequence of A. oryzae has been completed, functional genomics research has progressed slowly, due to its multinucleate conidia and its lack of a sexual life cycle. Until now, there have been on a few studies on ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae. In this study, we used bioinformatics to analyze ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae 3.042. Moreover, we also used RNA-seq to analyze the gene transcription profile of A. oryzae 3.042 treated with different ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, aiming to identify genes that are regulated after treatment with drugs that interfere with the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway. Previous studies have shown that the modification of ergosterol biosynthesis genes alters doubling time, response to stress agents, and drug susceptibility in S. cerevisiae [19]. Therefore, identification of these genes may provide some information about the usefulness of modifying the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway to improve the growth and stress tolerance, as well as for ergosterol production in A. oryzae.

Method and materials

Strain and culture conditions

The A. oryzae 3.042 (CICC 40092) was used in this study. To prepare the A. oryzae spores, wild-type A. oryzae 3.042 was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Solarbio, China) medium at 30 °C for 3 days. Then, spores were harvested by scraping the agar surface with a sterile glass spreader under a laminar flow hood and suspending the spores in sterile water with 0.05% Tween-80. The concentration of spores was determined using a hemocytometer.

Bioinformatics analysis of ergosterol biosynthesis genes in A. oryzae 3.042

The ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in S. cerevisiae was obtained from a review article [7]. The protein sequences of the enzymes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae were set as the reference sequences to identify homologous proteins in A. oryzae 3.042 using NCBI BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). As the genomic sequence of A. oryzae 3.042 was not completely assembled, we also used the protein sequences of A. oryzae RIB40 to identify ergosterol biosynthesis enzymes in A. oryzae 3.042.

Tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment of A. oryzae

A fresh A. oryzae 3.042 spore suspension (about 1 × 107 spores/ml) was cultured for 2 days on PDA medium. A mycelial plug (5 mm in diameter) was then taken from the medium and placed on PDA plates with different concentrations of inhibitors and without any inhibitor as a control. After incubation at 30 °C for 3 days, the diameter of each colony was measured in two perpendicular directions. For each plate, the average of the colony diameters was used to calculate the inhibition of mycelial growth (IMG). The IMG was calculated by the following formula: IMG = 100 × (C − N)/(C − 0.5), where C is the diameter of the control colony and N is the diameter of inhibitor-treated colonies. The experiment was performed three times. For RNA-seq, a fresh A. oryzae 3.042 spore suspension (about 1 × 107 spores/ml) was cultured for 2 days on PDA medium covered by cellophane (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and the cellophane with mycelia was transferred onto another plate with tebuconazole (Shanghai Agricultural Chemical Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) or terbinafine (Sigma) for 8 h. Then, the mycelia were collected for RNA-seq. Two biological replicates were performed for each treatment and the control.

Preparation of cDNA libraries and RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from 0.5 g mycelia using a fungal RNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the addition of a RNase-free DNase I treatment (Omega). RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), and RNA integrity was analyzed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). For cDNA library construction, each pooled RNA sample was prepared from an equal quantity of RNA from three individual cultures to ensure reliability and reproducibility. After enrichment from pooled total RNA using oligo (dT) magnetic beads, the mRNA was then digested into short pieces in fragmentation buffer at 94 °C for 5 min. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer-primers with the mRNA fragments as templates. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized by DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. Following end-repair and adaptor ligation, the products were amplified by PCR and purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) to create a cDNA library. The constructed libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina, USA) at Biomarker Technologies Co., generating 125-bp paired-end reads. Sequencing data were deposited in the NCBI/SRA database (Bioproject: PRJNA407274; BioSample: SAMN07637347).

Mapping reads to the reference genome and normalized gene expressions

Clean-read datasets of high quality were obtained from the raw data by removing low-quality reads, adaptor sequences, and reads with N’s (uncertain bases) exceeding 10%. The clean-reads were aligned to the A. oryzae genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/526?genome_assembly_id=29881) using Tophat (v2.0.7) software. As the genome of A. oryzae 3.042 was not completely assembled, some reads were mapped to A. oryzae RIB40. Meanwhile, the Q20, Q30, GC content, and sequence duplication rate of the clean data were also calculated. To identify differentially expressed genes between samples, transcript abundances were normalized by the RPKM metric (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads). The false discovery rate (FDR) within 0.05 and log2 (fold change) over 1 was set as the threshold for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [20, 21]. Furthermore, all DEGs were annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) classification and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses.

Results

Identification of ergosterol biosynthesis genes in A. oryzae 3.042

In S. cerevisiae, the genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis have been identified [7]. In order to investigate ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae 3.042, we used a bioinformatics approach to identify genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae 3.042. Therefore, we used the protein sequences of ergosterol biosynthesis enzymes from S. cerevisiae as the reference sequences to identify homologous proteins in A. oryzae 3.042. The results showed that the complete ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in A. oryzae 3.042 encodes homologs of all S. cerevisiae ergosterol biosynthesis genes (Table 1). However, these genes are very different from those in S. cerevisiae. Firstly, most of the ergosterol biosynthesis genes in S. cerevisiae appear as a single copy in the genome (expect HMG1/2), while A. oryzae 3.042 contains multiple paralogous genes. For example, six paralogues of ERG10 are present in the A. oryzae 3.042 genome, which we named as AoERG10-A to AoERG10-F, respectively. Secondly, although all of the genes homologous to those in S. cerevisiae can be found in A. oryzae 3.042, the identity ranged from 23 to 60% (Table 1). Therefore, bioinformatics analysis showed that the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway is conserved between S. cerevisiae and A. oryzae 3.042, but the ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae 3.042 appears to be more complex than in S. cerevisiae.

Table 1.

The Identification of ergosterol biosynthesis genes in A. oryzae 3.042

| Gene | S. cerevisiae | A. oryzae 3.042 | Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paralogous | Protein ID | Identify | |||

| AoERG10 | NP_015297.1 | 6 | EIT73661.1 | 60% | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| EIT73496.1 | 48% | ||||

| EIT79671.1 | 34% | ||||

| EIT78121.1 | 36% | ||||

| EIT78942.1 | 36% | ||||

| EIT80840.1 | 35% | ||||

| AoERG13 | NP_013580.1 | 2 | EIT76569.1 | 61% | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase |

| EIT75784.1 | 56% | ||||

| AoHMG1/2 | NP_013636.1/ NP_013555.1 | 5 | EIT73568.1 | 40% | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase |

| EIT78580.1 | 61% | ||||

| EIT81748.1 | 34% | ||||

| EIT83470.1 | 31% | ||||

| EIT73603.1 | 32% | ||||

| AoERG12 | NP_013935.1 | 1 | EIT78374.1 | 40% | Mevalonate kinase |

| AoERG8 | NP_013947.1 | 1 | EIT75656.1 | 33% | Phosphomevalonate kinase |

| AoERG19 | NP_014441.1 | 1 | EIT78501.1 | 58% | Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase |

| AoIDI1 | NP_015208.1 | 2 | EIT75013.1 | 52% | Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase |

| EIT75157.1 | 40% | ||||

| AoERG20 | NP_012368.1 | 5 | EIT77142.1 | 59% | Bifunctional (2E,6E)-farnesyl diphosphate synthase/ dimethylallyltranstransferase |

| EIT82866.1 | 27% | ||||

| EIT78828.1 | 26% | ||||

| EIT74365.1 | 24% | ||||

| EIT77275.1 | 23% | ||||

| AoEGR9 | NP_012060.1 | 1 | EIT75610.1 | 45% | Squalene synthetase |

| AoERG1 | NP_011691.1 | 1 | EIT81755.1 | 38% | Squalene epoxidase |

| AoERG7 | NP_011939.2 | 3 | EIT83324.1 | 45% | Lanosterol synthase |

| EIT77904.1 | 42% | ||||

| EIT79966.1 | 37% | ||||

| AoERG11 | NP_011871.1 | 3 | EIT83124.1 | 51% | Sterol 14-demethylase |

| EIT73378.1 | 52% | ||||

| EIT72345.1 | 49% | ||||

| AoERG24 | NP_014119.1 | 2 | EIT78405.1 | 39% | Sterol C-14 reductase |

| EIT72491.1 | 38% | ||||

| AoERG25 | NP_011574.3 | 2 | EIT77737.1 | 57% | Sterol C-4 methyloxidases |

| EIT75499.1 | 52% | ||||

| AoERG26 | NP_011514.1 | 2 | EIT79126.1 | 27% | Sterol C-4 decarboxylases |

| EIT82518.1 | 32% | ||||

| AoERG27 | NP_013201.1 | 1 | EIT80831.1 | 28% | Sterol 3-keto reductases |

| AoERG6 | NP_013706.1 | 2 | EIT83284.1 | 54% | Sterol C-24 methyltransferases |

| EIT80311.1 | 51% | ||||

| AoERG2 | NP_013929.1 | 1 | EIT81783.1 | 52% | Sterol C-8 isomerases |

| AoERG3 | NP_013157.1 | 3 | EIT79919.1 | 48% | Sterol C-5 desaturases |

| EIT80397.1 | 46% | ||||

| EIT73679.1 | 44% | ||||

| AoERG5 | NP_013728.1 | 2 | EIT82696.1 | 51% | Sterol C-22 desaturases |

| EIT73398.1 | 50% | ||||

| AoERG4 | NP_011503.1 | 3 | EIT80299.1 | 55% | Sterol C-24 reductases |

| EIT77041.1 | 50% | ||||

| EIT74004.1 | 38% | ||||

The effect of tebuconazole or terbinafine treatment on the growth of A. oryzae 3.042

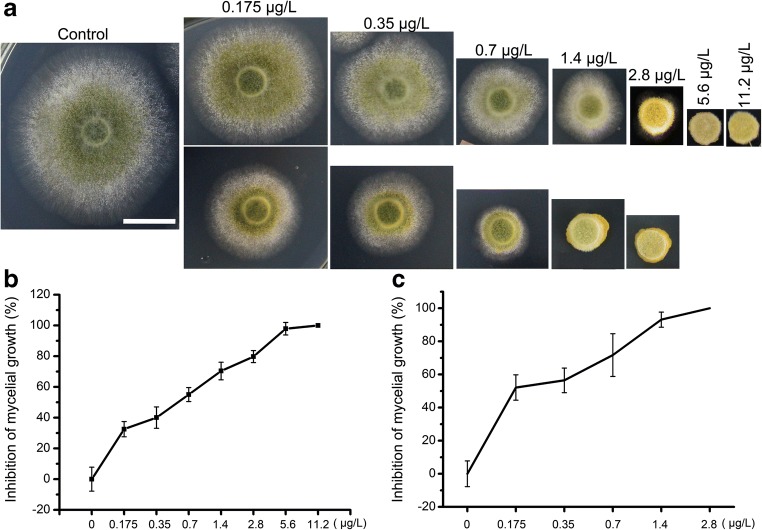

Through research on the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in yeast and other fungi, many ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors have been found [11]. We selected triazolone, tebuconazole, and terbinafine (the target site of triazolone and tebuconazole is ERG11, and the target site of terbinafine is ERG1) to treat A. oryzae 3.042. As shown in Fig.S1, all three drugs inhibited the growth of S. cerevisiae; however, only tebuconazole and terbinafine inhibited the germination and growth of A. oryzae 3.042, while A. oryzae 3.042 appears to be resistant to triazolone. Tebuconazole and terbinafine were used to calculate the IMG (Fig. 1a). Different concentrations of both inhibitors were added into PDA media. By measuring the diameter of colonies treated with inhibitors, we found that terbinafine is more active than tebuconazole as the IMG 50% concentration of tebuconazole was 0.7 μg/L, and that of terbinafine was 0.35 μg/L. Therefore, treatments with the inhibitors further proved that ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae 3.042 was conserved but more complex than in S. cerevisiae.

Fig. 1.

The effects of different concentrations tebuconazole and terbinafine on the growth of A. oryzae 3.042. a Growth inhibition of A. oryzae 3.042 by tebuconazole (top figure) and terbinafine treatment (bottom figure). b and c The inhibition rate of different concentrations tebuconazole (b) and terbinafine (c) treatment. (Bars = 1 cm)

Transcriptome overview

In order to identify target genes regulated by ergosterol in A. oryzae 3.042 and investigate the function of ergosterol in A. oryzae 3.042, we took advantage of RNA-seq to analyze gene expression in A. oryzae 3.042 following treatment with the ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors tebuconazole or terbinafine. The IMG 50% concentrations of each inhibitor listed above were chosen for the treatment for RNA-seq. Two biological replicates were performed for each treatment and control. The numbers of total reads for non-treated, tebuconazole or terbinafine treatments were greater than 43,200,200. Among those reads, the mapped reads ranged from 71.02 to 73.86%, and more than 70% were unique mapped reads. The % ≥ Q30 was greater than 86% and the GC content for all treatments was about 52%. The Pearson correlation coefficient between two repeats of each treatment was greater than 0.827, which indicates that the RNA-seq results of each treatment were repeatable and reliable. A summary of the RNA-seq results is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of RNA-seq results

| Tag classification | WT | Tebuconazole treatment | Terbinafine treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total reads | 43,268,556 | 43,621,230 | 43,762,690 | 43,265,164 | 43,984,152 | 44,658,384 |

| Percentage of identified reads | 71.02% | 71.12% | 73.86% | 73.59% | 73.77% | 73.51% |

| Percentage of unique reads | 70.88% | 70.97% | 73.68% | 73.40% | 73.60% | 73.35% |

| % ≥ Q30 | 86.12% | 86.41% | 86.87% | 86.84% | 87.19% | 87.09% |

| GC content | 52.51% | 52.51% | 52.71% | 52.63% | 52.66% | 52.67% |

| Pearson’s correlation coefficient | 0.843 | 0.925 | 0.827 | |||

Differentially expressed genes in response to treatment with inhibitors

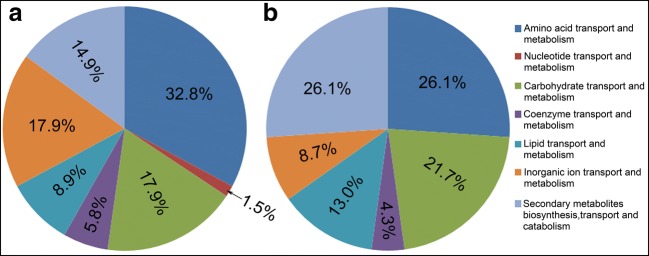

To identify genes that had their expression levels altered by treatment with ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, we quantified the overall transcription levels of genes using the RPKM method [22]. The number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for non-treated vs tebuconazole, non-treated vs terbinafine, and tebuconazole vs terbinafine were 138, 104, and 256, respectively. The summary of the DEGs from different inhibitor treatments is shown in Table 3. The 20 most upregulated and downregulated genes for non-treated vs tebuconazole, non-treated vs terbinafine, and tebuconazole vs terbinafine are shown in Supplementary Tables 1 to 4. To obtain greater information on the functional categories of the DEGs, the DEGs were analyzed by COG (cluster of orthologous groups of proteins) functional classification. As shown in Table 4, the COGs mapped to DEG gene function can be divided into six classes, including energy production and conversion, transport and metabolism, cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, general function prediction only, function unknown, and defense mechanisms. The most common were transport- and metabolism-related genes, which accounted for 61.6 and 66% of the DEGs for tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment, respectively. These transport- and metabolism-related genes can be divided into seven classes (Fig. 2). Among these seven classes, the most common for tebuconazole treated cells were amino acid, carbohydrate, and inorganic ion transporters (Fig. 2a), and the most common for terbinafine treated cells were lipid, amino acid, and carbohydrate transporters (Fig. 2b). The 10 most upregulated and downregulated transport- and metabolism-related genes for non-treated vs tebuconazole, non-treated vs terbinafine, and tebuconazole vs terbinafine are shown in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Table 3.

Summary of the DEG genes by different inhibitor treatments

| DEG set | DEG number | Upregulated | Downregulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wt vs tebuconazole | 138 | 22 | 82 |

| Wt vs terbinafine | 104 | 74 | 64 |

| Tebuconazole vs terbinafine | 256 | 215 | 41 |

Table 4.

COG function classification of genes regulated by inhibitors treatment

| Function classes | Tebuconazole treatment | Terbinafine treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Up | Down | Total | Up | Down | |

| Energy production and conversion | 5 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Transport and metabolism | 45 | 4 | 41 | 32 | 19 | 13 |

| Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| General function prediction only | 15 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 13 | 3 |

| Function unknown | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Defense mechanisms | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Fig. 2.

The classification of transport- and metabolism-related DEGs. a and b The classification of transport- and metabolism-related DEGs for tebuconazole and terbinafine treatments

Differentially expressed genes involved in lipid biosynthesis and transportation

Since ergosterol belongs to lipid, we investigated the DEGs related to lipid biosynthesis and transportation. All DEGs for tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment are shown in Table 5. For tebuconazole treatment, there were 12 DEGs related to lipid biosynthesis and transportation, including five downregulated and seven upregulated genes. Among these genes, the most upregulated gene was acyl-CoA synthetase (EIT77624.1), and the most downregulated gene was hypothetical protein with fatty acid elongase domain (EIT74279.1). For terbinafine treatment, there were 11 DEGs related to lipid biosynthesis and transportation, including 10 downregulated genes and only one upregulated gene. However, the most downregulated gene was an acyl-CoA synthetase (EIT80216.1). As the inhibitors block ergosterol biosynthesis, we also analyzed the ergosterol biosynthesis genes in detail (Table 6). For tebuconazole treatment, two DEGs involved in ergosterol biosynthesis were identified, the one is ergosterol biosynthesis ERG4/ERG24 family protein (EIT77602.1), the other is delta(14)-sterol reductase (AoERG24-B, EIT72491.1). For the terbinafine treatment, only C-4 methylsterol oxidase (AoERG25-B, EIT75499.1) was identified.

Table 5.

Effects of inhibitors treatment on the genes involved lipid biosynthesis and transportation

| Accession number | Putative production encoded by the gene | Fold changes in gene expression |

|---|---|---|

| Tebuconazole treatment | ||

| EIT74279.1 | Hypothetical protein with fatty acid elongase domain | − 4.1 |

| EIT77602.1 | Ergosterol biosynthesis ERG4/ERG24 family protein | − 3.0 |

| EIT74308.1 | Acetylcholinesterase/butyrylcholinesterase | − 2.8 |

| EIT81567.1 | Leucine rich repeat protein with phospholipid binding domain | − 2.8 |

| EIT75089.1 | Long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase | − 2.1 |

| EIT72491.1 | Delta(14)-sterol reductase (AoERG24-B) | 1.6 |

| EIT75885.1 | Putative dienelactone hydrolase | 1.9 |

| EIT79617.1 | Gluconate 5-dehydrogenase | 2.2 |

| EIT81441.1 | Fatty acid synthetase | 2.4 |

| EIT80791.1 | Esterase/lipase | 2.8 |

| EIT74373.1 | Carboxylesterase family protein | 3.8 |

| EIT77624.1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase | Inf |

| Terbinafine treatment | ||

| EIT80216.1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase | –Inf |

| CEJ94122.1 | Hypothetical protein with cytochrome P450 domain | − 5.1 |

| EIT76912.1 | Flavin oxidoreductase/12-oxophytodienoate reductase | − 4.8 |

| EIT78275.1 | Hypothetical protein which may involves in alcohol sensor | − 3.2 |

| EIT80997.1 | Acyl-CoA synthetases (AMP-forming)/AMP-acid ligases II | − 2.4 |

| EIT77697.1 | Lipase | − 2.4 |

| EIT76480.1 | Benzoate 4-monooxygenase cytochrome P450 | − 2.3 |

| EIT80068.1 | 1-acyldihydroxyacetone-phosphate reductase | − 2.3 |

| EIT80560.1 | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase | − 1.9 |

| EIT75499.1 | C-4 methylsterol oxidase (AoERG25-B) | − 1.8 |

| EIT78007.1 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1.7 |

Inf means infinite and –inf means minus infinity

Table 6.

The DEG genes involved in steroid biosynthesis

| Function classes | Fold changes in gene expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wt vs tebuconazole | Wt vs terbinafine | Tebuconazole vs terbinafine | |

| ERG4/ERG24 family protein (EIT77602.1) | − 3.0 | ND | ND |

| AoERG24 (EIT72491.1) | ND | 1.59 | 1.71 |

| AoERG25(EIT75499.1) | − 1.75 | ND | 2.75 |

| AoERG6(BAE59581.1) | ND | ND | 2.39 |

| AoERG3A(EIT79919.1) | ND | ND | 1.59 |

| AoERG3B(EIT73679.1) | ND | ND | − 1.92 |

ND represents not detected

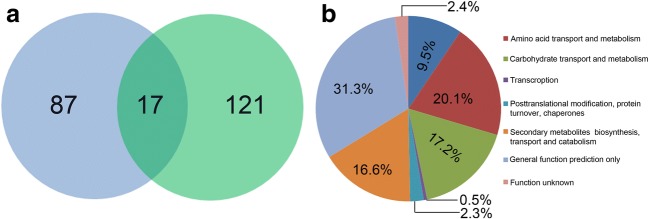

Comparison of gene expression profiles following tebuconazole or terbinafine treatments

In order to investigate the target genes regulated by ergosterol, the genes regulated by both tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment were identified. There were 17 genes identified as DEGs and the most common genes were classified as amino acid and carbohydrate transport, metabolism and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, and transport- and catabolism-related genes (Fig. 3). A detailed list of genes is shown in Table 7. Among the 17 DEGs, only one gene was upregulated and the other genes were all downregulated. Most of the DEGs encode hypothetical proteins with unknown functions. The only upregulated gene encodes a hypothetical protein located in the extracellular region. The remaining DEGs encode cell membrane and cell wall-related proteins, including glycosyl transferase, glucan synthases, cellulase, and cell membrane-anchored family protein. We also analyzed DEGs between tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment, and the 20 most upregulated and downregulated genes are shown in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8. As the identified DEGs involved in ergosterol biosynthesis are very different between the tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment groups, we also identified DEGs for tebuconazole vs terbinafine treatment involved in ergosterol biosynthesis. Six ergosterol biosynthesis genes were identified including ERG4/ERG24, AoERG24, AoERG25, AoERG6, AoERG3A, and AoERG3B. It is interesting that AoERG3A and AoERG3B showed different expression pattern in response to tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment (Table 6).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of DEGs between tebuconazole treatment and terbinafine treatment. a Venn diagram of genes regulated by both tebuconazole (right) treatment and terbinafine (left) treatment. b The classification of DEGs regulated by both tebuconazole treatment and terbinafine treatment

Table 7.

Genes regulated by both tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment

| Accession number | Putative production encoded by the gene | Fold changes in gene expression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tebuconazole treatment | Terbinafine treatment | ||

| EIT80584.1 | Glycosyl transferase | − 2.57 | − 3.22 |

| EIT78077.1 | Alpha-1,3 glucan synthases | − 2.74 | − 3.19 |

| EIT80342.1 | GPI anchored serine-threonine rich protein | − 2.79 | − 2.75 |

| EIT83128.1 | Carboxylic ester hydrolase activity | − 2.91 | − 3.31 |

| EIT80508.1 | Conserved hypothetical protein related to polysaccharide catabolic process with cellulase activity | − 2.43 | − 3.21 |

| EIT73411.1 | Conserved threonine rich protein, Ser-Thr-rich glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol-anchored membrane family | − 2.30 | − 2.34 |

| EIT81688.1 | Methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase | − 2.05 | − 2.12 |

| XP_002372960.1 | Hypothetical protein AFLA_080430 | − 2.70 | − 3.44 |

| XP_002382615.1 | Hypothetical protein AFLA_004140 | − 1.92 | − 2.78 |

| XP_002383654.1 | Hypothetical protein AFLA_097810 | − 3.28 | − 3.40 |

| EIT76225.1 | Hypothetical protein with monooxygenase activity and oxidation-reduction process | − 2.71 | − 1.76 |

| EIT82292.1 | Hypothetical protein with hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds | − 3.60 | − 2.91 |

| EIT83050.1 | Hypothetical protein with DNA binding located in nucleus | − 2.51 | − 3.43 |

| XP_001727223.1 | Hypothetical protein with sequence-specific DNA binding RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity | − 2.38 | − 3.97 |

| XP_003190202.1 | Hypothetical protein AOR_1_1158134 | − 2.55 | − 2.77 |

| XP_001727223.1 | Hypothetical protein AOR_1_284194 | − 2.87 | − 3.93 |

| XP_001825558.1 | Hypothetical protein AOR_1_66064, located in extracellular region | 3.84 | 2.56 |

Discussion

Ergosterol as well as intermediates of ergosterol pathway, such as lanosterol and zymosterol, is of great economic value. For example, lanosterol and zymosterol can be used as emulsifiers for cosmetics and precursors for the production of cholesterol lowering substances [23]. Therefore, it is of great value to study ergosterol biosynthesis. However, there has only been limited research on ergosterol biosynthesis in A. oryzae. In this study, we used bioinformatics and transcriptome analysis to identify genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis and those regulated after treatment with ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors.

Ergosterol biosynthesis genes in A. oryzae 3.042

The ergosterol biosynthesis pathway was found to be conserved in A. oryzae; however, multiple paralogues exist for almost all the biosynthesis genes: a situation that is not observed in S. cerevisiae. For example, AoERG10 has six paralogues, and AoHMG and AoERG20 have five paralogues each. Moreover, the amino acid sequences are not well conserved. Treatment with inhibitors showed that A. oryzae 3.042 was also sensitive to terbinafine (target site is ERG1) and tebuconazole (target site is ERG11), which further indicates that the functions of AoERG1 and AoERG11 were conserved. Therefore, our results indicate that the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in A. oryzae is conserved, but the biosynthesis enzymes and regulation mechanisms may be more complicated.

Effects of inhibitor treatment on gene transcription in A. oryzae 3.042

We identified 138 and 104 DEGs for non-treated vs tebuconazole and non-treated vs terbinafine, respectively. Compared with other transcriptome analyses, the number of DEGs appears to be smaller. This may be because RNA-seq was performed only 8 h after treatment with the inhibitors. However, the advantage of this is that these DEGs are more likely to be the direct target genes regulated by these inhibitors. It is interesting that among the DEGs, about half of these belong to transport- and metabolism-related genes, and the most common are those involved in amino acid and carbohydrate transport. This may be because ergosterol is an important component of the cell membrane and most transporters are located in the cell membrane. Therefore, these genes are those that respond quickly and directly to the inhibitors. As ergosterol and lipid metabolism are closely related, we also analyzed the effects of inhibitor treatment on genes involved in lipid biosynthesis and metabolism and identified 12 and 11 DEGs that were involved in lipid biosynthesis and metabolism for non-treated vs tebuconazole and non-treated vs terbinafine, respectively, including ergosterol biosynthesis genes.

Comparison of gene expression profiles following tebuconazole or terbinafine treatments

In this study, the gene expression profiles after tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment were investigated. The target site and the mechanism of action of two inhibitors are different. When the ERG11 was inhibited by tebuconazole, ergosterol biosynthesis was blocked. However, when the ERG1 was inhibited by terbinafine, it not only caused a decrease in ergosterol production in A. oryzae but also caused squalene accumulation in the plasma membrane, leading to increased fragility of the plasma membrane and resulting in the destruction of the structure and function of cell membrane [15]. The results of DEGs for non-treated vs tebuconazole and non-treated vs terbinafine further proved the different mechanisms. For example, among the DEGs for non-treated vs tebuconazole and non-treated vs terbinafine, there were only 17 genes that were regulated by both tebuconazole and terbinafine treatment. These 17 DEGs (16 downregulated and one upregulated genes) are likely to be the target genes directly regulated by ergosterol. The most frequently downregulated genes are classified as cell membrane and cell wall-related genes (Table 7). The possible reason is that blocking ergosterol biosynthesis changes the composition of the cell membrane, resulting in feedback regulation of cell membrane-related gene expression. It has been reported that ergosterol can act as a signaling molecule to activate the expression of defense-related genes in tobacco plants [24]. Thus, the downregulation of cell wall-related genes may be attributed to the use of ergosterol as a signaling molecule that mediates communication between the cell membrane and cell wall, and these cell wall-related genes are the target genes directly regulated by ergosterol. We also analyzed the DEGs between terbinafine and tebuconazole and found 256 DEGs, which was far more than that for non-treated vs tebuconazole and non-treated vs terbinafine, which further proves the different expression profiles of two treatments. On the one hand, these DEGs may be regulated by squalene accumulation caused by terbinafine treatment. However, on the other hand, the intermediates between EGR1 and ERG11, such as lanosterol, also play important roles in regulating A. oryzae gene expression, and these DEGs may be regulated by the intermediates.

In summary, the present study identified several genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis and the response of A. oryzae to ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors. These results provide new information on A. oryzae ergosterol biosynthesis and regulation, which may lay the foundation for the genetic modification of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, as ergosterol is not only important for the fungal growth, reproduction, and stress tolerance, but also of great economic value.

Electronic supplementary material

(PNG 1.88 mb)

(DOCX 16.9 kb)

(DOCX 16.8 kb)

(DOCX 17.1 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 16.4 kb)

(DOCX 16.8 kb)

(DOCX 17.1 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant nos. 31700068 and 31460447), International S&T Cooperation Project of Jiangxi Provincial (Grant no. 20142BDH80003), General Science and Technology Project of Nanchang City (Grant no. 3000035402), “555 Talent Project” of Jiangxi Province, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (Grant nos. 20181BAB214001 and 20171BAB214004), and the Open Foundation of Hubei Key Laboratory of Edible Wild Plants Conservation and Utilization (Grant no. EWPL201705).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhihong Hu and Ganghua Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Wollam J, Antebi A. Sterol regulation of metabolism, homeostasis and development. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:885–916. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-081308-165917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad R, Shah AH, Antifungals RMK. Mechanism of action and drug resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;892:327–349. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-25304-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beni A, Soki E, Lajtha K, Fekete I. An optimized HPLC method for soil fungal biomass determination and its application to a detritus manipulation study. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;103(4):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kodedova M, Sychrova H. Changes in the sterol composition of the plasma membrane affect membrane potential, salt tolerance and the activity of multidrug resistance pumps in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0139306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Görög S. Advances in the analysis of steroid hormone drugs in pharmaceuticals and environmental samples (2004–2010) J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2011;55(4):728–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiteman MK, Jeng G, Samarina A, Akatova N, Martirosyan M, Kissin DM, Curtis KM, Marchbanks PA, Hillis SD, Mandel MG, Jamieson DJ. Associations of hormonal contraceptive use with measures of HIV disease progression and antiretroviral therapy effectiveness. Contraception. 2016;93(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Z, He B, Ma L, Sun Y, Niu Y, Zeng B (2017) Recent advances in ergosterol biosynthesis and regulation mechanisms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Hayakawa H, Sobue F, Motoyama K, Yoshimura T, Hemmi H. Identification of enzymes involved in the mevalonate pathway of Flavobacterium johnsoniae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487(3):702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klug L, Daum G. Yeast lipid metabolism at a glance. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014;14(3):369–388. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Raboune S, Walker JM, Bradshaw HB. Distribution of endogenous farnesyl pyrophosphate and four species of lysophosphatidic acid in rodent brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(10):3965–3976. doi: 10.3390/ijms11103965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad A, Khan A, Manzoor N, Khan LA. Evolution of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors as fungicidal against Candida. Microb Pathog. 2010;48(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller C, Staudacher V, Krauss J, Giera M, Bracher F. A convenient cellular assay for the identification of the molecular target of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors and quantification of their effects on total ergosterol biosynthesis. Steroids. 2013;78(5):483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristan K, Rizner TL. Steroid-transforming enzymes in fungi. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;129(1–2):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer EI. Inhibitors of sterol biosynthesis and their applications. Prog Lipid Res. 1993;32(4):357–416. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(93)90016-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryder NS. Terbinafine: mode of action and properties of the squalene epoxidase inhibition. Br J Dermatol. 2010;126(s39):2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein AS, Frye LL. Synthesis and bioevaluation of delta 7-5-desaturase inhibitors, an enzyme late in the biosynthesis of the fungal sterol ergosterol. J Med Chem. 1996;39(26):5092–5099. doi: 10.1021/jm9605851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machida M, Asai K, Sano M, Tanaka T, Kumagai T, Terai G, Kusumoto KI, Arima T, Akita O, Kashiwagi Y, Abe K, Gomi K, Horiuchi H, Kitamoto K, Kobayashi T, Takeuchi M, Denning DW, Galagan JE, Nierman WC, Yu J, Archer DB, Bennett JW, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Fedorova ND, Gotoh O, Horikawa H, Hosoyama A, Ichinomiya M, Igarashi R, Iwashita K, Juvvadi PR, Kato M, Kato Y, Kin T, Kokubun A, Maeda H, Maeyama N, Maruyama JI, Nagasaki H, Nakajima T, Oda K, Okada K, Paulsen I, Sakamoto K, Sawano T, Takahashi M, Takase K, Terabayashi Y, Wortman JR, Yamada O, Yamagata Y, Anazawa H, Hata Y, Koide Y, Komori T, Koyama Y, Minetoki T, Suharnan S, Tanaka A, Isono K, Kuhara S, Ogasawara N, Kikuchi H. Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao G, Yao Y, Chen W, Comparison CX. Analysis of the genomes of two Aspergillus oryzae strains. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(32):7805–7809. doi: 10.1021/jf400080g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacharya S, Esquivel BD, White TC (2018) Overexpression or deletion of ergosterol biosynthesis genes alters doubling time, response to stress agents and drug susceptibility in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mBio 9(4):e01291–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Long M, Li ZQ, Lei B, et al. Identification and comparative study of chemosensory genes related to host selection by legs transcriptome analysis in the tea geometrid Ectropis obliqua. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7(10):986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanc G, Gallot-Lavallée L, Maumus F. Provirophages in the Bigelowiella genome bear testimony to past encounters with giant viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(38):5318–5326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506469112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wriessnegger T, Pichler H. Yeast metabolic engineering – targeting sterol metabolism and terpenoid formation. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52(3):277–293. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikeš V, Lochman J, Kašparovský T (2006) Ergosterol is a signal molecule that leads to the expression of defence-related genes in tobacco [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PNG 1.88 mb)

(DOCX 16.9 kb)

(DOCX 16.8 kb)

(DOCX 17.1 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 16.4 kb)

(DOCX 16.8 kb)

(DOCX 17.1 kb)