Abstract

Background

Patients' views of the services they receive in a healthcare service help identify critical areas that may need improvement. This survey set out to determine patients' satisfaction with quality of general services and specifically with staff attitude and the hospital environment, while on admission at a teaching hospital in Enugu, south-east Nigeria.

Methods

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study using a structured self-administered questionnaire on 170 patients (54% females and 46% males, aged between 20 and 65 years), post admission, selected by multistage sampling.

Results

Less than half (47.3%) of the patients were satisfied with care received on admission. More than half of them (51.8%) were satisfied with the cleanliness of the hospital environment and how power supply was maintained in the hospital (62.4%). Doctors (90%), nurses (64.1%) and records staff (60.6%) were considered courteous and professional. Most patients were satisfied with the level of privacy given to them in their course of hospital stay (67.6%) and with the cost of laboratory investigations (51.8%).

Conclusion

Despite more than half of the surveyed patients being satisfied with some specific aspects of services given while on admission, those satisfied with the overall experience were less than half. Therefore, periodic patient satisfaction surveys should be institutionalized in this facility to provide feedback for continuous quality improvement.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, tertiary facility, healthcare, Nigeria

Introduction

Health, according to the World Health Organization, is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity1,2. Thus, a health facility should be a place that strives to help patients return to health as defined. Patient satisfaction has gained recognition as a measure of the quality of service delivery3,4,5. This recognition is not lost on the health sector as the necessity for constant enhancement of quality and safety in the delivery of patient care in healthcare facilities has become an accepted concept6–9. The observation and determination of patient satisfaction offers an indicator of the quality of care that considers the patients' perspectives10–13. Patients and their relatives have been recognized as the best source of information on the dignity and respect with which they are being treated14,15. Patient encounters often disclose how well a hospital system is working, offering insight into areas that need changes and providing useful information that assists management to close gaps between the way things are being run and the way things should be run15.

Patient satisfaction is the degree to which the patient's desired expectations, goals and or preferences are met by the health care provider and or service9,11,16. Such a report from an individual patient on the quality of medical care received from physicians, nurses and other relevant sources in a health care facility is posited to represent the level of the patients' satisfaction with the care received, even though evidence suggests that the survey data generated can be underutilized by staff17–21. Poor patient satisfaction has been related to some undesirable details as stated in a recent article; that a patient who complains means that 20 more may have been silent though unhappy and their grievances may never be known; 70 percent of dissatisfied patients may never return; 75 percent of dissatisfied patients will discourage up to 9 family members or friends22. Such figures should make a hospital's management uncomfortable. The aim of this survey was to determine patients' overall satisfaction with quality of general services and specifically with staff attitude and hospital environment while on admission to a teaching hospital in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria.

Methods

The study was conducted at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH), located between Ituku and Ozalla towns of Enugu, south-east Nigeria, between September and December 2015. It is a 500-bed facility having outpatient clinics and wards that cover most clinical specialties of medicine while being a noted cardiothoracic centre of excellence. It serves as a referral center for tertiary care to over 3 million citizens of the state and more from other states in the south-east region of the country.

The sample size was determined using the Cochran's formula n0=(z2 pq)/e2 (Where no is the sample size, Z2 is the abscissa of the normal curve that cuts off an area α at the tails; (1 — α) equals the desired confidence level, 95%; e is the desired level of precision, 0.05; p is an estimated proportion of patients satisfied with clinical services from a previous study in this population22, 0.94; and q is 1-p). The value for Z is as found in statistical tables which contain the area under the normal curve, here Z = 1.96 for 95 % level of confidence. To the resulting sample size of 86.6, 10% was added to take care of possible nonresponse giving 95.7. However, 239 questionnaires were prepared with 170 filled; a 71.1% response rate. Utilizing a descriptive cross-sectional study design and by multistage sampling (first a simple random sample of hospital departments, followed by a proportionate sampling of patients discharged from male and female wards of the selected departments), an estimated sample of 239 adult patients was given a self-administered structured questionnaire. This questionnaire had been developed by the authors using information obtained during literature review. A pilot test was conducted in the nearby state-owned teaching hospital. It obtained information on patients' socio-demographic data, satisfaction with the hospital environment, admission processes and services received from the staff at different service points related to admission (clinic, records, laboratory, pharmacy and the ward) and satisfaction with their overall experience while on admission. Ethical clearance was obtained from the hospital's ethical review committee, while verbal and written consent was sought and obtained from each patient after a detailed explanation of the purpose of the study was given. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 23 was used to analyze the data collected, presented in tables as frequencies and percentages with one chart showing the proportion of patients that were generally satisfied with the care they had received.

Results

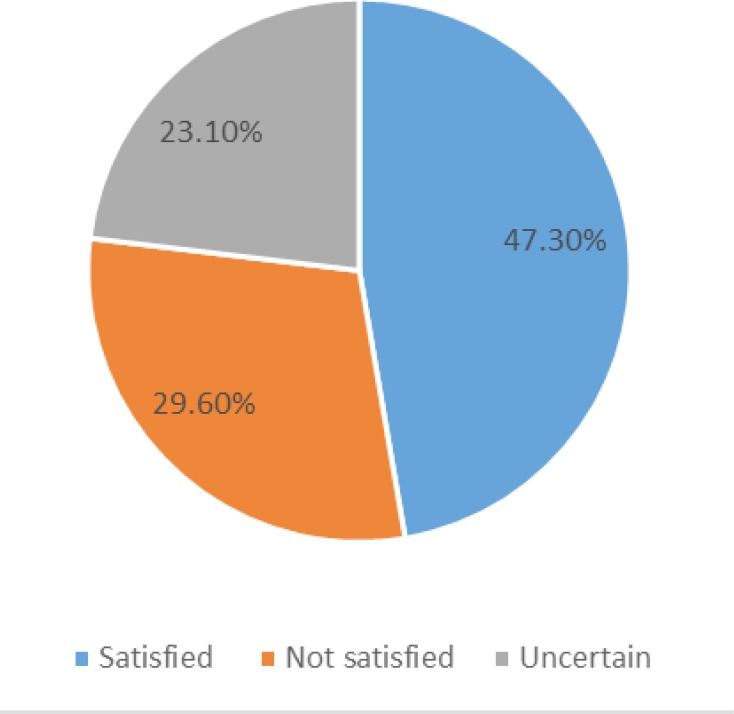

The patients interviewed were adult patients between the ages of 20 and 65 years. There were 170 respondents who consented, out of the 239 exit interviews initiated, a response rate of 71%. There were 54.1% females and 45.9% males in all that participated in the study. They were mostly civil servants (47.6%), those engaged in business/trading (27.1%) and unemployed/students (25.3%). Most of the respondents were educated to the tertiary level (48.3%). All were incidentally Christians and mostly from the Igbo tribe (94.7%), Table 1. For overall care, fewer than half (47.3%) of the respondents expressed satisfaction with the care they received while on admission, 29.6% were not satisfied and 23.1% of them were uncertain. (Figure 1) More than half of the respondents agreed that the hospital environment was clean (51.8%) and that there was a fairly constant power supply in the hospital (62.4%). Less than half of the respondents, expressed satisfaction with other aspects of the hospital environment, like availability of potable water (18.8%), cleanliness of bathrooms and toilets (14.7%), availability of good and affordable food (32.9%) and comforts provided to accommodate their relatives (14.1%). (Table 2) Doctors were considered courteous and professional by a good number of the respondents (90%). Doctors always listened to their complaints (90.6%) and always explained the reasons for the tests they ordered (74.1%). More than half of the respondents considered the nurses (64.1%) and the records department staff (60.6%) courteous and professional as well. A similar number of respondents was also satisfied with the level of privacy provided in the course of their stay in the hospital (67.6%). Fewer respondents, however, expressed satisfaction with the pharmacy (41.8%) and the medical laboratory staff (43.5%). (Table 2)

Table 1.

Socio demographic characteristics of respondents

| Age | Frequency N = 170 |

Percent |

| 20–30 years | 65 | 38.2 |

| 31–40 | 50 | 29.4 |

| >40 | 55 | 32.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 78 | 45.9 |

| Female | 92 | 54.1 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed/students | 43 | 25.3 |

| Business/traders | 46 | 27.1 |

| Civil servants | 81 | 47.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 107 | 62.9 |

| Single | 63 | 37.1 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| First school leaving certificate | 23 | 13.5 |

| WASSCE | 44 | 25.9 |

| B.sc/ HND | 82 | 48.3 |

| Others | 19 | 11.2 |

| No response | 2 | 1.2 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 170 | 100 |

| Tribe | ||

| Igbo | 161 | 94.7 |

| Yoruba | 6 | 3.5 |

| Others | 3 | 1.8 |

Figure 1.

Overall patient satisfaction

Table 2.

Patient's overall satisfaction and with hospital environment, health worker attitude and services

| Aspect | Frequency (%) N = 170 |

||

| Hospital Environment | Satisfied | Not Satisfied | Uncertain |

| The hospital environment is clean | 88 (51.8) | 53 (31.2) | 29 (17.1) |

| Potable water is readily available | 32 (18.8) | 86 (50.6) | 52 (30.6) |

| The bathrooms and toilets are clean | 25 (14.7) | 83 (48.8) | 62 (36.5) |

| There is affordable and good food | 56 (32.9) | 47 (27.6) | 67 (39.4) |

| There is fairly constant power supply | 106 (62.4) | 29 (17.1) | 35 (20.6) |

| Patients relatives are comfortable | 24 (14.1) | 87 (51.2) | 59 (34.7) |

| Health Worker Attitude | |||

| Doctors are courteous and professional |

153 (90) | 3 (1.8) | 14 (8.2) |

| Doctors always listen to complaints | 154 (90.6) | 5 (2.9) | 11 (6.5) |

| Doctors always explain reasons for tests |

126 (74.1) | 26 (15.3) | 18 (10.6) |

| Patient satisfied with level of privacy given |

115 (67.6) | 44 (25.9) | 11 (6.5) |

| Nurses are courteous and professional |

109 (64.1) | 39 (22.9) | 22 (12.9) |

| Pharmacists are courteous and professional |

71 (41.8) | 37 (21.8) | 62 (36.5) |

| Laboratory scientists are courteous and professional |

74 (43.5) | 55 (32.4) | 41 (24.1) |

| Record department staff are courteous and professional |

103 (60.6) | 30 (17.6) | 37 (21.8) |

| Hospital Services | |||

| Hospital admission processes are not stressful |

46 (27.1) | 80 (47.1) | 44 (25.9) |

| Clinic waiting time is fair | 76 (44.7) | 58 (34.1) | 36 (21.2) |

| Equipment are available and functional |

50 (29.4) | 76 (44.7) | 44 (25.9) |

| Laboratory waiting time is fair | 54 (31.8) | 62 (36.5) | 54 (31.8) |

| Laboratory results are promptly available |

69 (40.6) | 61 (35.9) | 40 (23.5) |

About half of the respondents were satisfied with the cost of laboratory investigations (51.8%), while fewer expressed satisfaction with other aspects of hospital services; admission process (27.1%), clinic waiting time (44.7%), availability and functionality of equipment (29.4%), laboratory waiting time (31.8%), promptness of laboratory results (40.6%), in-stock status of drugs (45.9%) and pharmacy waiting time (42.9%).

Discussion

This descriptive cross-sectional study in a teaching hospital assessed, using a questionnaire, patient satisfaction with general services received and specifically with the hospital environment and with staff attitude. In case of general services, less than half of the patients were satisfied. More than half were satisfied with the cleanliness of the hospital environment and with power supply. Doctors, nurses, and records staff were considered courteous and professional. Most were also satisfied with the level of privacy given and with the cost of laboratory investigations. Patient satisfaction with hospital services is a concept initially thought to be difficult to measure24–26. The process provides information on problems or successes with service areas, exposing them for improvement or continuity10,11,27. There is no single universal method for measuring this concept28,29,30,31 as a myriad of tools to measure it have been developed and utilized. However, like has been utilized in this study, the tool most frequently cited in literature to measure patient satisfaction is a survey32–37 using questionnaires16,38–42.

This study assessed patient satisfaction with services in general within the study teaching hospital and less than half of the respondents were satisfied with overall services received while on admission. This finding agrees with that of an earlier study in the same hospital22 that focused on eye care services where it was found that, like in this study, fewer than half (45.6%) of the respondents would recommend the hospitals services to another. Another assessment in the same year of pediatric services in this same hospital43 elicited an overall assessment of satisfaction from more than half of respondents, (51.2%). It is interesting to note that the average of the proportions of patients from these two studies that examined individual departments of the same hospital is similar (<50%) to the finding in this study which examined a sample of all the departments. One other study 44 revealed overall patient satisfaction among 56.4% of respondents for services received at a Federal Medical Centre in Makurdi, Benue State. In India Sreenivas45, observed that few patients were satisfied with the services received from three hospitals studied simultaneously. Iliyasu et al46, in Kano Nigeria, observed patient satisfaction overall with teaching hospital services from a good number (83%) of patients. In Anambra state, Nigeria, Emelumadu et al47 also observed satisfaction overall with services in the general outpatient department of the Nnewi teaching hospital from a good number (79%) of patients. Patient satisfaction surveys of hospital services, in general, can go either way, thus this should be carried out intermittently as a management tool to assess patients' perception of quality of services. The result of this study should thus call the attention of the hospital's management to issues around patient care examined here.

Looking at specific aspects of care, for the environment, a good number of the respondents in this study were satisfied with the level of cleanliness of the hospital environment. The study by Ezegwui et al22 also observed satisfaction with the cleanliness of the eye clinic in UNTH among patients. This is similar to figures reported by Adeniyi et al in Lagos 48 and Sreenivas et al in India45. Satisfaction, however, did not extend to other and more critical aspects of the hospital environment, for concerning the availability of potable water for drinking and washing up, not up to half of the patients were satisfied while others were either not satisfied or undecided. Concerning cleanliness of bathrooms and toilets, this study found that not much may have changed in the year preceding the study which focused on eye care services22. This is a finding similar to results observed by Seetesh et al in India49.

Patients, while on admission, are usually served with food and are made as comfortable as possible. However, this was not the case for patients' relatives. The number of respondents satisfied with the availability of good and affordable food (for relatives) was low, and it was the same with availability of facilities to accommodate patients' relatives. Patients' relatives provide physical and emotional support while on admission, thus this finding underscores the observation by Adamson et al that to ensure patients have emotional support is to improve patient satisfaction with hospital services50. They went ahead to suggest that organizational effort at understanding components of emotional support in hospital care will lead to actions that ensure that basic comforts are provided for patient's relatives which will potentially improve patient satisfaction scores and, in turn, the overall perception of quality of patient care. A good number of the respondents in this study also expressed satisfaction with the fairly constant power supply while on admission. These findings indicate that beyond services, aspects of the hospital environment contribute to the overall perception of satisfaction with hospital services.

It has been noted in the literature that even though patients expect competence, they will only give a neutral satisfaction rating in response to competence. Competence and courtesy will get a satisfactory rating, while in the presence of competence, courtesy, and compassion, patients will be very satisfied21. The attitude of the clinical staff (doctors and nurses) and the records staff was satisfactory to a good number of respondents in this study, more than could be said for laboratory and pharmacy staff. Other studies have also reported varying levels of overall satisfaction with staff attitudes and thus the services they provide. Ilyasu et al46, Yadav et al51 and Seetesh et al49 have reported satisfaction with clinical staff while Ezegwui et al22, Eke et al43 and Emelumadu et al47 observed dissatisfaction with other staff also. Conversely, Jeremiah et al52 and Yawson et al53 in Ghana reported dissatisfaction with clinical staff and in Benin Oparah et al reported dissatisfaction with pharmacists and pharmacy services54. These findings may draw attention to the issue of patient satisfaction in relation to health worker attitude in developing countries. An observed trend of satisfaction with clinical staff and contrasting dissatisfaction with attitude and treatment by non-clinical staff may imply that this cadre of health workers may present a weak link in the perception of quality of health care delivery in this and other hospitals in the study country.

On hospital services in general, a good number of respondents in this study expressed satisfaction with the costs of laboratory investigations, while few were satisfied with admission processes, clinic, laboratory and pharmacy waiting times, drugs not being in stock and the unavailability or poor functioning of hospital equipment. Iliyasu et al46 in Kano indicated dissatisfaction with waiting time and cost of treatment. Yadav et al51 observed satisfaction with diagnostic services among patients in a multi-specialist tertiary hospital in northern India. Seetesh et al in India49 observed patients satisfied with the admission process and with the beds provided. For another study in India, it was low patient satisfaction with the outpatient services in a hospital and research center55. As it has been shown here, other studies also show that in a hospital, patient satisfaction can vary for different components of care as well as with the overall measure of patient satisfaction for services37,55, at different times.

Conclusion

Despite the satisfactory rating for certain separate aspects of services given by more of the patients in the survey, the overall experience while on admission did not get this satisfactory rating from the most. Aspects of service that need to be maintained are the cleanliness of the hospital environment and provision of power and aspects needing improvement are the cleanliness of bathrooms and toilets, availability of potable water, decent/affordable food and provision of facilities to accommodate relatives. Effect of staff attitude on satisfaction is varied; while the attitude of doctors, nurses, and records staff was commended, the attitude of pharmacy and medical laboratory staff needed to be addressed at the time of the study. Admission processes, clinic, laboratory and pharmacy waiting times, promptness of laboratory results and availability of functional equipment and drugs also need, as a feedback from the survey, to be reviewed.

Recommendation

The utility of patient satisfaction surveys in examining the quality of services in a hospital is recognized here, thus the findings of this survey will be used for advocacy to the hospital's medical advisory committee in favor of the institution of such surveys periodically as a quality improvement tool.

Limitations

Patient interviews (one-on-one or as group interviews) may have provided a deeper understanding of the patient's perspectives on hospital services than the self-administered structured questionnaire utilized.

The authors also recognize that, despite the pilot testing of the questionnaire, patients could still have misunderstood some of the questions or been reluctant to answer honestly without ample opportunity for clarification with the study instrument used.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was made possible through the assistance of four fifth-year medical students of the institution. We would like to acknowledge the following persons who participated in the data collection exercise: Chisomebi W. Eze, Izuchukwu S. Eze, Kingsley C. Eze and Emmanuel O. Igata. The authors would like to kindly acknowledge the patients for granting us permission to seek further information from them even after being discharged. This study did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, author. Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity; International Health Conference; New York. 1946. pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kühn S, Rieger UM. Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely absence of disease or infirmity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):887. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortenberry JL, Jr, McGoldrick PJ. Internal marketing: A pathway for healthcare facilities to improve the patient experience. Int J Healthc Manag. 2016;9(1):28–33. doi: 10.1179/2047971915Y.0000000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonard DJ. Exploring Customer Service through Hospital Management Strategies [Doctoral dissertation] Walden University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu HC, Li T, Li MY. A study of behavioral intentions, patient satisfaction, perceived value, patient trust and experiential quality for medical tourists. J Qual Ass Hosp Tour. 2016;17(2):114–150. doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2015.1042621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carayon P. Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in healthcare and patient safety. 2nd ed. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press; 2016. Apr 19, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mossialos E, Courtin E, Naci H, Benrimoj S, Bouvy M, Farris K, et al. From “retailers” to health care providers: transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy. 2015;119(5):628–639. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozenblum R, Miller P, Pearson D, Marielli A. Patient-centered healthcare, patient engagement, and health information technology: the perfect storm. In: Grando MA, Rozenblum R, Bates D, editors. Information technology for patient empowerment in healthcare. Germany: De Gruyter; 2015. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debono D, Travaglia J. (University of New South Wales). Complaints and patient satisfaction: a comprehensive review of the literature. Report. Sydney Australia: Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kieft RA, de Brouwer BB, Francke AL, Delnoij DM. How nurses and their work environment affect patient experiences of the quality of care: a qualitative study. BMC health serv res. 2014;14(1):249. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boquiren VM, Hack TF, Beaver K, Williamson S. What do measures of patient satisfaction with the doctor tell us? Patient Educ and Couns. 2015;98(12):1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Averbeck BM, Hayek AM, Schmitt KG, Lindquist TC, et al. Can patient safety be measured by surveys of patient experiences? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(5):266–274. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, Epstein AM, David-Kasdan J, Feibelmann S, et al. Comparing patient-reported adverse events with medical record review: Do patients know something that hospitals do not? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(2):100–108. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beach MC, Forbes L, Branyon E, Aboumatar H, Carrese J, Sugarman J, et al. Patient and family perspectives on respect and dignity in the intensive care unit. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2015;5(1A):15A–25A. doi: 10.1353/nib.2015.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleary PD. A hospitalization from hell: a patient's perspective on quality. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):33–39. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Abri R, Al-Balushi A. Patient satisfaction survey as a tool towards quality improvement. Oman Med Jour. 2014;29(1):3–7. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harnett MJ, Correll DJ, Hurwitz S, Bader AM, Hepner DL. Improving efficiency and patient satisfaction in a tertiary teaching hospital preoperative clinic. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(1):66–72. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c617cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bah S, Alharthi H, El Mahalli AA, Jabali A, Al-Qahtani M, Al-kahtani N. Annual survey on the level and extent of usage of electronic health records in government-related hospitals in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2011;8:1b. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyer L, Francois P, Doutre E, Weil G, Labarere J. Perception and use of the results of patient satisfaction surveys by care providers in a French Teaching Hospital. Intern Journ Qual Health Care. 2006;18(5):359–364. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draper M, Cohen P, Buchan H. Seeking consumer views: what use are results of hospital patient satisfaction surveys? Intern Journ Qual Health Care. 2001;13(6):463–468. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.6.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medical Executive Council, author. Schumacher Clinical Partners. 2016. [Online]. [cited January 9, 2017]. Available from: http://www.schumacherclinical.com/health-care-insights/2016/1/the-role-of-customer-satisfaction-in-patient-care.

- 22.Ezegwui IR, Aghaji AE, Okoye O, Oguego N. Patient's satisfaction with eye care services in a Nigerian Teaching hospital. Nigerian Jour Clin Pract. 2014;17(5):585–588. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.141423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IBM Corp., author IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; Released 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins K, O'Cathain A. The continuum of patient satisfaction—from satisfied to very satisfied. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(12):2465–2470. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camgöz-Akdağ H, Zineldin M. The quality of health care and patient satisfaction: an exploratory investigation of the 5Qs model at some Egyptian and Jordanian medical clinics. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2006;19(1):60–92. doi: 10.1108/09526860610642609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamps PL, Finkelstein JB. Statistical analysis of an attitude scale to measure patient satisfaction with medical care. Med Care. 1981;19(11):1108–1135. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escobar-Koch T, Banker JD, Crow S, Cullis J, Ringwood S, Smith G, et al. Service users' views of eating disorder services: an international comparison. Int Jour Eat Disord. 2010;43(6):549–559. doi: 10.1002/eat.20741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saila T, Mattila E, Kaila M, Aalto P, Kaunonen M. Measuring patient's assessments of the quality of outpatient care: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chanthong P, Abrishami A, Wong J, Herrera F, Chung F. Systematic review of questionnaires measuring patient satisfaction in ambulatory anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(5):1061–1067. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819db079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oermann CM, Swank PR, Sockrider M. Validation of an instrument measuring patient satisfaction with chest physiotherapy techniques in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2000;118(1):92–97. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han CH, Connolly PM, Canham D. Measuring patient satisfaction as an outcome of nursing care at a teaching hospital of southern Taiwan. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18(2):143–150. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis BA, Kiesel CK, McFarland J, Collard A, Coston K, Keeton A. Evaluating instruments for quality: testing convergent validity of the consumer emergency care satisfaction scale. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(4):364–368. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200510000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persse DE, Jarvis JL, Corpening J, Harris B. Customer satisfaction in a large fire department emergency medical services system. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):106–110. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greco M, Sweeney K, Brownlea A, McGovern J. The practice accreditation and improvement survey [PAIS]: what patients think. Aus Fam Physician. 2001;30(11):1096–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hargraves JL, Wilson IB, Zaslavsky A, James C, Walker JD, Rogers G, et al. Adjusting for patient characteristics when analyzing reports from patients about hospital care. Med Care. 2001;39(6):635–641. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curry A, Stark S. Quality of service in nursing homes. Health Serv Mgt Res. 2000;13(4):205–215. doi: 10.1177/095148480001300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris LE, Swindle RW, Mungai SM, Weinberger M, Tierney WM. Measuring patient satisfaction for quality improvement. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1207–1213. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yueh JH, Slavin SA, Adesiyun T, Nyame TT, Gautam S, Morris DJ, et al. Patient satisfaction in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction: a comparative evaluation of DIEP, TRAM, latissimus flap, and implant techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(6):1585–1595. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181cb6351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis S, Byers S, Walsh F. Measuring person-centered care in a sub-acute healthcare setting. Aus Health Rev. 2008;32(3):496–504. doi: 10.1071/AH080496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potiriadis M, Chondros P, Gilchrist G, Hegarty K, Blashki G, Gunn JM. How do Australian patients rate their general practitioner? A descriptive study using the General Practice Assessment Questionnaire. Med J Aust. 2008;189(4):215–219. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gasquet I, Villeminot S, Estaquio C, Durieux P, Ravaud P, Falissard B. Construction of a questionnaire measuring outpatients' opinion of the quality of hospital consultation departments. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swaine BR, Dutil E, Demers L, Gervais M. Evaluating clients' perceptions of the quality of head injury rehabilitation services: development and validation of a questionnaire. Brain Inj. 2003;17(7):575–587. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000088568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eke BC, Ibekwe RC, Muoneke VU, et al. End-user's perception of quality of care of children attending children's outpatient clinics of University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):800. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onwujekwe A, Etiaba E, Uche AM. Patient satisfaction with health care services, a case study of the Federal Medical Centre, Makurdi, Nigeria. Int Jour Med Health Dev. 2013;18(1):125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sreenivas T, Babu NS. A study on patient satisfaction in hospitals: (A Study on Three Urban Hospitals in Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh) Int J Mgmt Res & Bus Strat. 2012;1(1):101–108. Available from: http://www.ijmrbs.org/ijmrbsadmin/upload/IJMRBS_506d13fb1f2c3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Abubakar S, Lawan UM, Gajida AU. Patient's satisfaction with services obtained from Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano. Nig Jour of Clin Prac. 2010;13(4):371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emelumadu OF, Ndulue CN. Patients characteristics and perception of quality of care in a teaching hospital in Anambra State, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2012;21(1):16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adeniyi AA, Adegbite KO, Braimoh MO, Ogunbanjo BO. Factors affecting patient satisfaction at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital Dental Clinic. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2013;42(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seetesh G, Videk S. Patient satisfaction with medical services: a hospital-based study. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2011;34(4):232–242. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adamson K, Bains J, Pantea L, Tyrhwitt J, Tolomiczenko G, Mitchell T. Understanding the patients perspective of emotional support to significantly improve overall patient satisfaction. Healthc Q. 2012;15(4):63–69. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2012.23193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yadav P, Mangwana S. Analysis of patient satisfaction survey in a multi-specialty tertiary care hospital in Northern India. Int Jour Basic Appl Med Sci. 2014;4(3):33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeremiah I, Kasso T, Oriji VK. Patients' perception of antenatal care at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Niger J Med. 2012;21(1):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yawson AE, Hesse Afua AJ, Amoo PK, Reindorf AC, Seneadza HN, Baddoo AN. In the eyes of the beholder: assessment by clients on the health care delivery in a large teaching hospital in Ghana. West Afr J Med. 2013;32(1):31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oparah AC, Enato FO, Akoria OA. An assessment of patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical services in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Int J Pharm Pract. 2004;12(1):7–12. doi: 10.1211/0022357023204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Madhavi M, Deepa V, Sumedha J, Aasawari N. A study of patient satisfaction towards outpatient department services of a hospital using exit interviews. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2013;44:1–2. [Google Scholar]