Abstract

The eastern oyster plays a vital role in estuarine habitats, acting as an ecosystem engineer and improving water quality. Populations of Chesapeake Bay oysters have declined precipitously in recent decades. The fossil record, which preserves 500 000 years of once-thriving reefs, provides a unique opportunity to study pristine reefs to establish a possible baseline for mitigation. For this study, over 900 fossil oysters were examined from three Pleistocene localities in the Chesapeake region. Data on oyster shell lengths, lifespans and population density were assessed. Comparisons to modern Crassostrea virginica, sampled from monitoring surveys of similar environments, reveal that fossil oysters were significantly larger, longer-lived and more abundant than modern oysters from polyhaline salinity zones. This pattern results from the preferential harvesting of larger, reproductively more active females from the modern population. These fossil data, combined with modern estimates of age-based fecundity and mortality, make it possible to estimate ecosystem services in these long-dead reefs, including filtering capacity, which was an order of magnitude greater in the past than today. Conservation palaeobiology can provide us with a picture of not just what the Chesapeake Bay looked like, but how it functioned, before humans.

This article is part of a discussion meeting issue ‘The past is a foreign country: how much can the fossil record actually inform conservation?’

Keywords: oysters, conservation palaeobiology, Chesapeake Bay, Crassostrea virginica, Pleistocene

1. Introduction

The overarching goal of conservation palaeobiology is to use the fossil record to provide a long-term perspective on conservation priorities and restoration efforts. Oyster-based ecosystems are ideal candidates for this approach, because these communities are threatened globally as a direct result of overharvesting, disease and coastal degradation [1–3]. Restoration, of the oysters themselves and the ecosystem services they provide, is hampered by a lack of long-term monitoring data and shifting baselines [4]. A century ago, these ecosystem engineers provided a multitude of ecosystem services such as creating habitat, improving water quality and protecting shorelines. Oysters dominated temperate coastal ecosystems worldwide and played a vital role in benthic–pelagic coupling [5–8]. Despite the long list of ecosystem services that oysters provide, it is their value as a food source for humans that has driven mitigation efforts. In the Chesapeake Bay (USA), these efforts have yielded mixed results, despite millions of dollars and decades of work [9–12]. Oyster mitigation in the bay has focused almost exclusively on management for fishery production and is limited by a lack of knowledge of pre-human conditions. By the time oyster monitoring was established in the 1940s, reefs were demolished, suggesting that oyster managers have never actually observed a healthy reef in the Chesapeake Bay [2,13,14]. The fossil record of the bay stretches back half a million years and provides the only direct data available on the age structure, size range and population density of oysters [2,15,16].

The goal of this study is to reconstruct population demographics in Chesapeake fossil oysters and to use this information, in the context of modern demographics, to estimate ecosystem services, including filtration and carbon cycling. This research represents one of the first attempts to model ecosystem services for an ancient reef ecosystem and demonstrates the value of taking a conservation palaeobiological approach to mitigation.

2. Background

(a). Oysters in the Chesapeake Bay: present

The eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) is a vitally important species, economically and ecologically, in the Chesapeake Bay today. The bay, which is the largest estuary in the continental USA, faces an overwhelming catalogue of threats, including overharvesting, disease, sediment pollution, eutrophication and climate change [17–21]. Oysters in the modern bay are thought to represent less than 1% of their historical abundance, based on oyster harvest statistics [21,22].

The federal and state budget for bay oyster mitigation has topped out at $73 million per year for the fiscal year 2019 [23]. Much of this funding has been funnelled into projects focusing on the early life-history stages of oysters, in particular spreading shell on the bay bottom [24]; broodstock enhancement [25]; rearing disease tolerant strains and monitoring [24,26]. In recent years, reef-building efforts have expanded from two- to three-dimensional approaches and from loose to cemented substrates [11,20,27]. Strategies that specifically target later life-history stages, such as long-term (multi-year) sanctuaries [28–30] or fishing gear bans [31], are less common.

Oyster mitigation in the bay is made considerably more difficult by the destruction and levelling of reef topography associated with dredging, which began in the late 1800s [3,31,32]. Dredging produced a colossal harvest of oysters, which reinforced their economic importance in the mid-Atlantic, at the same time driving a decline in annual accretion rates from 13 mm over the past 10 000 years to less than 1 mm over the past 100 years [33]. Annual harvest rates peaked at 14–20 million bushels of oysters per year in the late 1800s and have plummeted by 98% in recent decades [2,21,32,34].

(b). Population demographics of the eastern oyster

Oysters in the bay today rarely live past 5 years of age and display steeply declining numbers across all size classes [11,35,36]. Oysters, including C. virginica, are thought to exhibit type 3 demographic (or mortality) curves, characterized by precipitously decreasing numbers throughout their life expectancy [37–39]. The mathematical model of such a demographic curve involves a single phase applied uniformly throughout the lifespan of the oyster. This expectation has proved difficult to test in the bay, owing to the almost complete collapse of the fishery. Population density estimates from monitoring data vary from zero to 1500 oysters m−2 [40–42]. An oyster reef in the mid-Atlantic USA is considered a mitigation success once it reaches a population density of 50 living oysters (or recruits) m−2 [43].

(c). Oysters and ecosystem services

Oysters contribute a myriad of ecosystem services to estuarine and shallow coastal environments, including water filtration, three-dimensional habitat, coastal buffering, denitrification and carbon burial [5,6,19,20,44–48]. Quantitative estimates of some of these services, including filtration, can be generated at the population level. Approximations of suspended food (particulate organic carbon as POC or particulate organic nitrogen as PON) and filtration efficiency (retention of particles by size class) can be used to assess trophic transfer of POC or PON from the water column to benthic fauna. In this way, oysters serve as critical agents of benthic–pelagic coupling [22,45,49,50].

The role that shellfish harvesting and aquaculture play in carbon cycling is gaining widespread attention [48,51–54] owing to the growing need to mitigate climate change. Molluscs sequester carbon as calcium carbonate through the process of shell growth [51,55]. The amount of carbon incorporated into calcium carbonate varies between species but is on average 11.7%. The calcification process involves net production of carbon dioxide, which may lead to an increase in pCO2 in surface waters and eventually the atmosphere, especially in shallow well-mixed coastal waters. Therefore, the calcification process is considered by some to be a source of atmospheric CO2 [48]. Other authors argue that the carbon stored in the shell represents a long-term sink. Hickey [51] calculated the amount of carbon sequestered per year in oyster farms, using shell carbon content, oyster weight, grow-out time and stocking density to be between 3.81 and 17.94 t carbon (C) ha−1 yr−1. Higgins et al. [56] created a model based on the results of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen elemental analysis of tissue and shell, which estimated that an oyster bed could remove a total of 13.47 ± 1.00 t C ha−1 yr−1 in a single growing season at a density of 286 oysters m−2. This represents a rate of carbon sequestration that exceeds other forms of blue carbon sequestration [57,58].

(d). Oysters in the Chesapeake Bay: past

Oysters served as a food source for humans in the Chesapeake Bay region long before the advent of commercial harvesting [15,59–62]. Harvesting before the invention of the dredge was accomplished via patent tongs (by the eighteenth century) and hand collection, a painstaking operation that harvested two orders of magnitude fewer oysters per year in the Chesapeake Bay [2,14,59,63]. Commercial harvesting in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was preceded by colonial-era harvesting [33,41,59,64,65], which in turn was preceded by Native American harvesting dating back to earlier than 13 000 years ago [2,15,60]. Several of the threats facing bay oysters today began during the 1700s and 1800s, with localized evidence for overharvesting [59,63], eutrophication [15] and climate change [66] affecting oyster populations. Harvesting rates can be estimated for older time intervals using historical records [65] and archaeological middens [13,67] and suggest that oyster fishing was sustainable until at least the colonial period [14,67].

Turning to the fossil record, C. virginica dominated mid-Atlantic estuaries for at least 3 Myr. As sea-level rose and fell multiple times throughout the Pleistocene, oysters migrated up and downstream, invading newly formed estuaries and building three-dimensional structures [33,68,69]. Holocene oysters reefs are commonly underlain by hard terrace structures dating back to the Tertiary or Pleistocene [68], suggesting that these structures formed preferentially on hard substrate. Although fossil oyster assemblages do occur in the Chesapeake Bay region, few are accessible for collecting. Reefs that are accessible are metres thick, with thousands of articulated shells preserved in life position [16]. Other sites have been previously sampled, and material has been accessioned in multiple museum collections. The fossil record of Chesapeake Bay oysters makes it possible to reconstruct oyster size, growth rates and population demographics before human alteration of this ecosystem. This approach, which is termed conservation palaeobiology [13,70,71], can yield important insights into baseline populations and ecosystem services that may prove useful for oyster mitigation.

3. Methods

Samples of Pleistocene C. virginica younger than 500 Ka were compiled from three localities in the Chesapeake Bay region (table 1). Holland Point (HP) is still accessible for field collecting, while Cherry Point (CP) and Wailes Bluff (WB) are only accessible from Virginia Museum of Natural History (VMNH) collections (WB: VMNH 71LW93; CP: VMNH 78BB79A, B, VMNH T8TC56). All specimens were collected via bulk sampling, and all left valve hinges (representing all sizes) were counted for population density. Complete right valves longer than 35 mm were measured for maximum dimension (referred to here as shell length) and lifespan (electronic supplementary material, table 1). Lifespan was estimated by bisecting valve hinges using a tile saw and counting major grey growth bands, following Zimmt et al. [72]. For additional site information, including age estimates, palaeotemperature and palaeosalinity reconstructions, see Kusnerik et al. [16]. Unfortunately, nutrient (or productivity) levels could not be estimated for these three fossil sites because HP does not preserve microfossils and WB and CP are no longer available for microfossil sampling.

Table 1.

Location, stratigraphic unit, and geological age of the four major localities sampled for modern and Pleistocene oysters.

| site | state | sample size (greater than or equal to 35 mm) | latitude/longitude | stratigraphic unit | time interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wailes Bluff (WB) | MD | 36 | 38.065560° −76.365280° |

Tabb | Late Pleistocene |

| Cherry Point (CP) | VA | 36 | 37.634184° −76.412830° |

Shirley | Mid-Pleistocene |

| Holland Point (HP) | VA | 898 | 37.512088° −76.432121° |

Shirley | Mid-Pleistocene |

| Brown Shoal (BS) | VA | 947 | 37.013092° −76.469571° |

— | modern |

For modern C. virginica, data on shell length and lifespan were obtained from sites that matched the temperature and salinity reconstructions of the fossil localities. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources (M. Tarnowski 2017, personal communication) provided length-at-age data for six sites from Pocomoke and Tangier Sounds (n = 1176 specimens, grab sample, 2013–2015, 15–25 ppt salinity). Publications from the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences provided length-at-age data for Brown Shoal (BS) in the James River (n = 947, hydraulic patent tong, 2006–2008, 10–23 ppt salinity) [35] and seven sites on the Lynnhaven River (n = 697, quadrat, 2005–2008, 15–30 ppt salinity; table 1) [36]. For additional site information, see Kusnerik et al. [16]. Size-frequency and lifespan distributions for oysters greater than 35 mm were normalized using a Box–Cox transformation then compared across all Pleistocene and modern localities using parametric statistics (t-tests).

Estimates of population density for modern oysters were compiled from VOSARA [73] for 29 sites in the James River, York River, and the main channel of the bay (2002–2014, 15–25 ppt salinity). These estimates were obtained by sampling 1 m2 of bay bottom via hydraulic patent tong (approx. 50 l of sediment and shell per sample) and counting live oysters representing all sizes.

Unfortunately, the only Pleistocene site accessible for collecting data on population density was HP. The exposed oyster deposit at HP is laterally extensive (up to 25 m) and thick (up to 3 m), with the majority of oysters preserved in life position. Population density was estimated for HP by excavating the fossil deposit from above, bulk sampling 15 0.25 m × 0.25 m × 0.05 m chunks of sediment and shell, and counting left valves of all sizes. Volumes of these samples were then extrapolated to 50 l of material, to match the sample volume of modern population density estimates (number of oysters m−2; electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Although the oyster deposit at HP is preserved in life position and shows no evidence of compaction, it is likely to represent a time averaged (i.e. age-mixed) deposit. Time averaging, or the mixing of fossils from different years in a single deposit [74], is difficult to quantify directly for this deposit, because the only dating technique that can be applied to this locality (amino acid racemization) has yielded age estimates of low temporal resolution [16]. As an alternative, ratios of living versus dead (i.e. brown shell) oysters were compiled from VOSARA [73] for the same 29 sites described above (2002–2014, 15–25 ppt salinity). Because data on living oysters were reported as individuals (number of oysters m−2), while data on dead oysters were reported as volume (litres), a conversion factor of 21.25 oysters l−1 [75] was used to calculate the ratio of living versus dead oysters at each site, for each sample. The average of this ratio across samples, sites and years was then used to adjust population density data from HP for potential time averaging (electronic supplementary material, table S2). It should be noted that these ratios are likely to greatly overestimate the number of dead oysters (and therefore underestimate population density) at HP because the majority of the modern sites are harvested (preferentially removing live shell) and shell planted (preferentially adding dead shell). Data on Pleistocene and modern population densities were normalized using a Box–Cox transformation then compared across all Pleistocene and modern localities using parametric statistics (t-tests).

Calculation of ecosystem services relies on estimates of population demographics, including population density and size-frequency distributions. Shell length and population density from HP, the only site that is accessible for collecting, were used to represent Pleistocene localities (electronic supplementary material, table S3). BS, on the James River, was selected to represent modern population demographics because it is one of the few bay reefs growing under similar environmental conditions as HP for which coupled size-frequency and population density data are available [35] (electronic supplementary material, table S3).

Oyster filtration rates were calculated using a minimum estimator (2.5 l g−1 dry tissue weight h−1 [76], based on a long-term mean value that includes periods of low feeding, and a maximum estimator (9.62 l g−1 dry tissue weight h−1) [45]. Both values are estimated at 26°C, assuming a Q10 value of 2.0, or a doubling of rate with a 10°C increase in temperature over a temperature range from approximately 4–6°C (below which filtration ceases) to greater than or equal to 35°C (above which physiological stress approaches a thermal limit). Oyster biomass (dry tissue weight) varies allometrically with length and is described by a y = axb relationship, wherein y is the weight, x is shell length, and both a and b are constants. Note that b (size exponent) can be quite plastic in oysters because of their variable shape [77]. Physiological rate functions such as filtration and respiration scale with weight, and thus the rate versus length description is a similar allometric relationship. Once the values of a and b are defined from population samples, then whole population estimates of filtration per unit area can be generated and scaled appropriately to reef coverage in estuarine or coastal systems (SOM Filtration Calculation).

Cycling of carbon was determined using the model of carbon flux developed by Fodrie et al. [48]. Fodrie et al. [48] estimated both inorganic and organic carbon cycling in oyster reefs, and how it varies according to live oyster density, based on experimental and natural oyster assemblages from North Carolina. Assessment of the relationship between carbon flux (CF, Mg C ha−1 yr−1) and population density (D, per 0.25 m2) is given as

Inorganic carbon (IC, Mg C ha−1 yr−1) and organic carbon (OC, Mg C ha−1 yr−1) are related to population density (D, per 0.25 m2) as follows:

and

4. Results

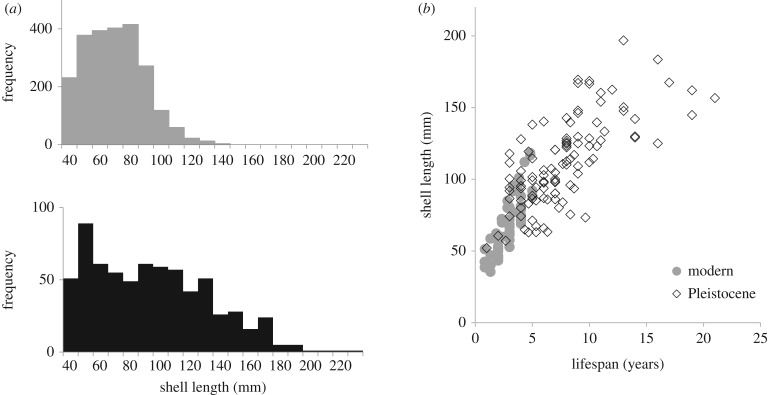

Pleistocene oysters in the Chesapeake Bay grew to significantly larger sizes (figure 1a; t683,2307 = 14.99, p < 0.0001), and longer lifespans (figure 1b; t106,56 = 12.46, p < 0.0001), than modern C. virginica growing under the same temperature and salinity regimes. Modern oysters are, on average, 30% smaller than Pleistocene oysters, and display truncated size-frequency distributions. Maximum shell length in modern oysters rarely exceeds 120 mm, while Pleistocene oysters can reach lengths in excess of 250 mm. This difference is size does not result from faster growth rates in Pleistocene oysters. In fact, growth rates in modern oysters (15.72 mm yr−1) are twice as fast as Pleistocene oysters (7.82 mm yr−1) (when modelled linearly for oysters less than or equal to 5 years of age). Instead, this pattern results from the fact that Pleistocene oysters lived an average of 5 years longer than modern oysters, which is more than double (2.75×) the average lifespan of the latter.

Figure 1.

Comparison of shell size and growth rates in modern and Pleistocene oysters from Chesapeake Bay. (a) Size distributions (mm) of modern (grey, above) versus Pleistocene (black, below) oysters in the bay. Pleistocene oysters are significantly larger than modern ones, owing to the preferential harvest and disease-related die-off of larger oysters in the bay today. (b) Relationship between lifespan (years) and shell length (mm) in modern (grey) versus Pleistocene (black) oysters. Pleistocene oysters had significantly longer lifespans than modern oysters, although there is no significant difference in growth rates (i.e. slope).

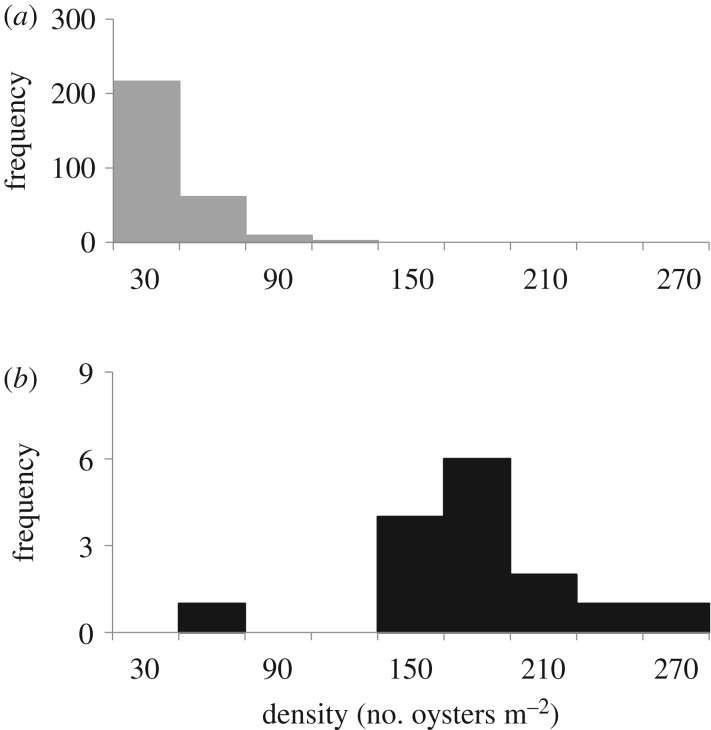

Based on the single site available for sampling, Pleistocene oysters in the Chesapeake region reached significantly higher population densities than their modern counterparts (figure 2; t15,302 = 11.13, p < 0.0001), growing under the same temperature and salinity conditions. Although it is impossible to quantify nutrient levels at the Pleistocene sites, density (number of oysters m−2) is almost an order of magnitude higher in these fossil reefs, despite the fact that nutrient levels are almost certainly higher in the modern bay. This suggests that many of the modern populations undergoing monitoring in the James River, York River and main stem of the bay are operating well below their original carrying capacity. The highest population densities recorded in the polyhaline salinity range (15–30 ppt) in the modern bay occur at Johnson's Rock in the main channel [73], which has recorded densities ranging from 18.9 (2012) to 99.8 (2007) oysters m−2. Mean density at this reef (44.4 oysters m−2) is still 73% lower than mean density in the Pleistocene (160 oysters m−2).

Figure 2.

Frequency distributions of population density (number of oysters per square metre) estimates for modern (a) and Pleistocene (b, adjusted for time averaging) oysters from the Chesapeake Bay. Pleistocene assemblages display significantly higher population density than modern reefs, despite the conservative nature of the fossil population estimate. Modern populations reaching 50 oysters m−2 are considered fully recovered by Chesapeake Bay standards.

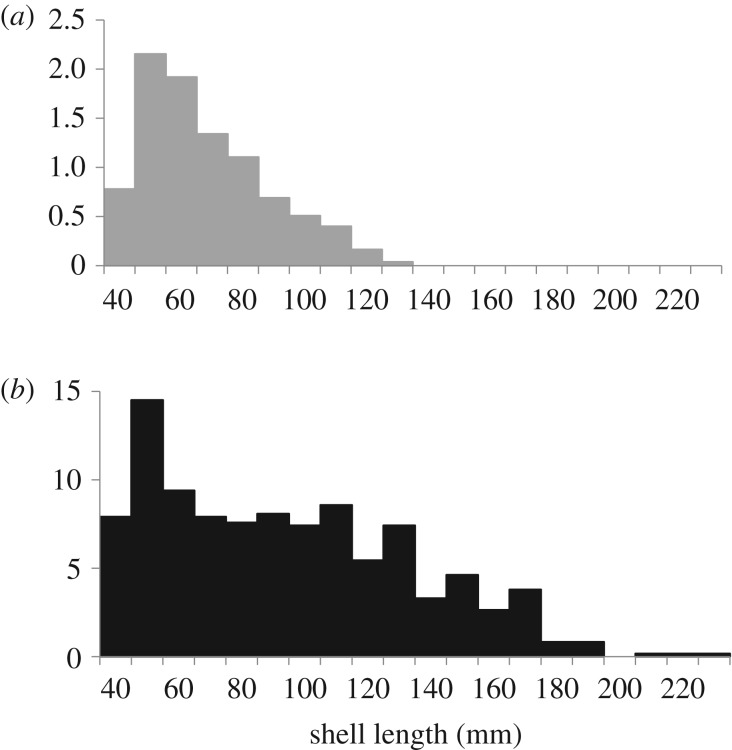

The demographics of Pleistocene oysters, as exemplified by the HP site, differ significantly from the modern demographic observed at BS on the James River (figure 3). The latter (figure 3a) exhibits a typical type 3 demographic curve with a steep decline in numbers across all size classes (reaching a maximum shell length of 130 mm). The former (figure 3b) records a plateau or very gradual decline in numbers spanning the 60–130 mm size classes (reaching a maximum length of 258 mm). The modern population, originating in the James River and still subject to both harvest and disease pressures, truncates rapidly above 90 mm and is poorly represented in the mid-phase of growth when mortality rates are lowest.

Figure 3.

Comparison of population demographics between modern (a) and Pleistocene (b) bay oyster assemblages. Demographic curves, standardized to population density per square metre, are provided for one modern site (a), BS, versus one fossil site (b), HP, with similar temperature and salinity conditions. The demographic curve for BS decreases steeply across all size classes to reach a maximum shell size of 130 mm. By contrast, the curve for HP plateaus in abundance across the 60–130 mm size classes, before decreasing steeply to reach a maximum shell size of 258 mm. This fundamental difference in population structure has important implications for ecosystem services, including filtration.

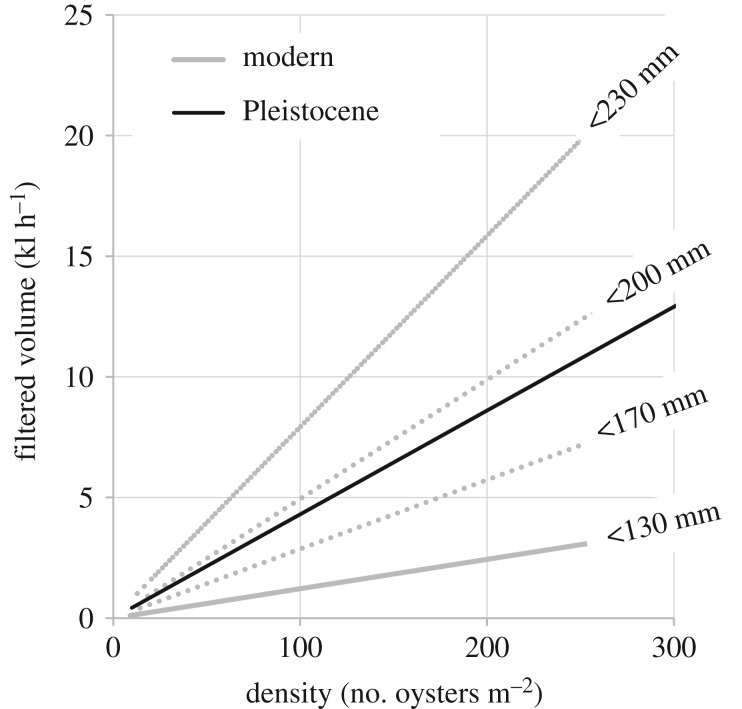

The changes in lifespan and shape of the demographic curve from Pleistocene to modern oyster populations have a disproportionate effect on ecosystem services, such as filtration. Filtration estimates for the Pleistocene reef (HP), which exhibits an average population density of 160 oysters m−2 and a size range of 0–258 mm, range from 1.89–7.27 kl h−1, depending on the filtration estimator used. The modern reef (BS), with an average population density of 9.08 oysters m−2 and a size range of 0–130 mm, yields filtration estimates an order of magnitude lower, ranging from 0.03 to 0.11 kl h−1. To determine to what extent these massive differences in filtration stem from differences in population density versus differences in the shape of the demographic curves, we modelled filtration rates for the modern and Pleistocene assemblages, holding the shape of the demographic curves constant, while varying population density (figure 4). Even at the same population density, filtration rates are significantly faster in the Pleistocene reef, presumably because filtration rates are allometrically related to body size in oysters. Because filtration capacity increases more steeply in the Pleistocene than the modern reef with increased population density (figure 4), this difference is maximized at higher population densities.

Figure 4.

Results of filtration model for modern and Pleistocene population demographics. Filtered volume (kilolitre per hour) increases linearly with population density (number of oysters per square metre), for both modern (solid grey line) and Pleistocene (solid black line) populations. Slope of the line increases with the length of the plateau in population demographics (dotted lines), varying from no plateau (reaching a maximum size of 130 mm) to a plateau spanning the 70–170 mm size classes (reaching a maximum size of 230 mm). At the same population density of 100 oysters m−2, the Pleistocene population, with its larger oysters, would filter almost four times as much water per hour as the modern reef.

Relatively small changes in the shape of the demographic curve can produce large increases in filtration capacity. To assess the effect of a plateau in the demographic curve, we modelled the BS population without a plateau (max shell length = 130 mm), then with an increasingly longer plateau. To model the increase in plateau length, we started by adding a plateau for a single size class (at 60 mm) then expanding the duration of that plateau iteratively to include progressively more size classes (max shell length 230 mm; figure 4). The Pleistocene assemblage displays a plateau spanning the 60–130 mm size classes, equivalent to a maximum shell length of 190–200 mm when modelled using the BS demographic curve. This emphasizes the fact that mitigation with the goal of increasing the lifespan or size of oysters will have a significantly higher effect on filtration than simply increasing population density.

According to the Fodrie et al. [48] model of carbon cycling, IC will experience net burial for both the modern and fossil reefs. BS (population density = 9 oysters m−2 = 2.25 0.25 m−2) produces approximately −19.39 Mg IC ha−1 yr−1, while HP (population density = 160 oysters m−2 = 40 0.25 m−2) produces closer to −3.45 Mg ha−1 yr−1. Organic carbon undergoes net burial for the modern reef (−1.09 Mg ha−1 yr−1) versus net production (+0.233 Mg ha−1 yr−1) for the Pleistocene reef. At average population densities, carbon flux predicts net burial for both the modern and fossil reefs (−12.6 Mg ha−1 yr−1 for BS, −3.45 Mg ha−1 yr−1 for HP). Under the Fodrie et al. [48] model, which is entirely based on population density rather than oyster size, oyster reefs are modelled as carbon sinks until they reach a population density of 500 oysters m−2. Population densities in the fossil reef are considerably closer to this threshold than modern reefs.

5. Discussion

(a). Shifting baselines of oyster populations

The Pleistocene data suggest that C. virginica can live up to 21 years of age, a figure that is slightly older than previous, qualitative estimates (10–15 years) [78,79]. This is in sharp contrast to bay oysters today, which rarely survive past 5 years [40]. Age truncation in extant populations is driven by size-selective harvest, disease epizootics or both [17,18,21]. Although the effects of disease became evident in the bay in the late 1940s, oyster and disease monitoring were begun at effectively the same time [64,80], preventing the establishment of a true baseline for the bay. This leaves open the possibility that oyster diseases such as Dermo, along with other non-human forms of predation, have been affecting these populations longer than previously recognized.

Although Chesapeake Bay oysters lived substantially longer in the past than today, modern oysters show higher growth rates than their Pleistocene counterparts. This pattern of elevated growth rates mirrors a pattern documented by Kirby & Miller [15] for oysters from mid to late eighteenth century sites along the St Mary's and Patuxent Rivers in Maryland. Kirby & Miller [15] suggested that eutrophication increased levels of phytoplankton, which in turn enhanced growth of C. virginica between 1760 and 1860. The lack of available microfossil material from HP, WB and CP make it difficult to directly test this hypothesis for the Pleistocene material.

The demographic curve for Pleistocene oysters must be viewed with caution because it is sourced from a single available site (HP). Population demographics for HP differ markedly from the hundreds of demographic curves available from modern sites with similar environmental conditions (29 sites sampled annually in the James River, York River and the main channel of the bay, 2002–2014, 15–25 ppt salinity, [73]). The HP curve does, however, show surprising parallels with demographic curves from invasive populations of Crassostrea gigas in the Oesterschelde, The Netherlands [81], in addition to natural C. virginica reefs in South Carolina [82]. Like the Pleistocene assemblages, the Oesterschelde oysters are not harvested and display a complex demographic curve with a steeply declining initial section from recruitment to attaining a refuge size from most benthic predators at greater than 60 mm (see, for example, discussions in [81]). Walles et al. [81] identified a plateau in the Oesterschelde demographic curve spanning the 60–150 mm size classes (varies by site), then declining steeply to reach a maximum length of 200 mm. The Pleistocene assemblage, by comparison, exhibits a plateau spanning the 60–130 mm size classes, then declining steeply to reach a maximum length of 258 mm. The mathematical description of this more complex demographic curve would include a minimum of three distinct phases, as opposed to the single phase observed in modern bay oysters. This variation in the shape of demographic curves challenges the long-held type 3 dogma [39] and emphasizes the potential importance of longer-lived, larger-sized oysters in these populations.

(b). Filtration rates

Estimates of filtration rates for the Pleistocene oyster population must also be viewed with caution, until additional fossil sites can be identified and sampled. It must be noted that, even with the extremely conservative estimate of HP population density used here, Pleistocene filtration rates are an order of magnitude greater than those of modern populations growing in similar temperature and salinity conditions. At rates ranging from 1.89 to 7.27 kl h−1, Pleistocene reefs would have been capable of filtering accessible bay water in a day. The substantial decrease in filtration estimates seen in modern reefs is driven not simply by a decrease in population density, but also by the truncations in modern oyster size and lifespan. Although oysters larger than 60 mm represent less than one-quarter of the Pleistocene assemblage numerically, they are the vast majority of the biomass for a very substantial portion of the life expectancy of individuals in the population. Because ecosystem services, like filtration, are allometrically related to body size, these larger oysters play a significant role in reef function.

In the filtration model applied here, the allometric relationship between C. virginica length and weight is described as y = axb, with b ranging from 2 to 3 (R. Mann and M. Southworth 2019, unpublished data for Virginia Chesapeake Bay populations) [77]. Applying this equation to individual oysters of lengths 50, 75, 100, 125, 150 and 200 mm (with a b exponent of 2.24 taken from an extant James River, VA population) at 26°C (using the estimator of [45]) yields dry tissue weights of 23, 57, 109, 179, 270 and 514 g, respectively. Filtration scales with dry tissue weight at the individual oyster level. A demographic including a single oyster at each of 50 and 75 mm length, similar to what we see in the modern bay population (figure 3), yields a biomass of 80 g. A demographic including one of each of the six sizes listed above generates a biomass of 1132 g, which is 14 times larger than the truncated modern population.

Both fossil and modern populations show high recruitment, accompanied by high mortality in the first year post recruitment (growth to approx. 55–60 mm shell length). The disparity in mortality of larger oysters (greater than 60 mm) drives order of magnitude differences in ecosystem services provided by the modern versus fossil populations. Although this calculation focuses on the filtration aspect of ecological services, it is a precursor to considering other services provided by oyster reefs. These reefs generate benthic structural complexity in mid-latitude soft-bottom estuaries that generally lack complex biogenic carbonate structures. They also produce an abundance of biogenic carbonate, which acts as an alkalinity ‘bank’ to moderate temporal environmental stressors [52,83,84], and a potential sink for carbon in shallow estuarine and coastal systems.

(c). Carbon source or sink

Carbon from both terrestrial and atmospheric sources exhibits net transport to burial in marine sediments [85,86]. Molluscs, and particularly bivalve shells, are part of this process. The details of shell dissolution, physical disintegration, burial, periodic exhumation and fossilization are important in both the biology of the sediment–water interface and the formation of structure underlying reefs in estuarine habitats [10,87]. The success of the oyster form in biogenic carbonate production is illustrated by its long-term presence in the fossil record with comparatively modest morphological change over a wide biogeographic range [8,88]. The longevity of the oyster form may also relate to its successful invasion of intertidal habitats. Although an intertidal life habit has allowed oysters to evade predation, it has come at the cost of evolving physiological tolerance to associated respiratory challenges and thermal stressors [79,89].

The Fodrie et al. [48] model, which is based solely on population density, suggests that, if Pleistocene reefs in the Chesapeake Bay reached population densities of 500 oysters m−2, they would have acted as a source, as opposed to a sink, of carbon. This model, because it is ground-truthed using oyster assemblages in North Carolina, suggests that carbon burial does not correlate positively with vertical oyster accretion. While this may be true for the natural and experimental oyster reefs examined in North Carolina, it is somewhat difficult to apply to Pleistocene Chesapeake Bay reefs. The reefs in North Carolina were distributed across three habitats: intertidal sandflats, shallow subtidal sandflats or fringing the seaward edge of saltmarsh, none of which closely resemble past Chesapeake Bay conditions. Both the modern and fossil reefs examined in this study are classified as subtidal reefs preserved within a finer-grained (sandy silt), as opposed to sandflat, substrate. When the Fodrie et al. [48] data are subdivided by habitat, only the intertidal reefs acted as carbon sources—in part because both the inorganic and organic carbon produced in these reefs resist burial in these wave-swept environments. The finer-grained substrates in which the Pleistocene fossil assemblages are preserved suggest a much quieter, less dynamic system, in which burial might have been possible. As the Fodrie et al. [48] model is applied to a wider swathe of oyster ecosystems, it should be feasible to determine the threshold at which oyster ecosystems act as carbon sources versus sinks. It may even be possible to directly measure carbon sequestration in these ancient sediments, enabling us to analyse ecosystem services over much longer timescales.

(d). Ecosystem engineering

Bivalves, in particular oysters, are among the pioneer invaders of newly formed estuaries as sea-level rises [33,90]. The complex structure of oyster reefs facilitates fertilization in species employing mass spawning of gametes into the water column [91–93], encourages recruitment of settling pre-metamorphic stages [8] and provides protection for newly recruited juveniles from predators [94,95]. Thus, the role of biogenic carbonate reefs is crucial in ecosystems that lack other hard complex habitat above the sediment–water interface, including the majority of temperate and subtropical estuaries, which generally form in sedimentary basins [96,97]. Oyster shell resources accumulate naturally over tens to hundreds of thousands of years but have been destroyed by human activity in fewer than 10 years [20].

What limits the rate of biogenic carbonate shell production in estuaries, and therefore its ultimate burial? The current study suggests that, at summer temperatures, Pleistocene reefs were capable of filtering the Chesapeake Bay water column in a matter of hours or days. This rate is commensurate with phytoplankton production, suggesting that oysters in the Pleistocene were capable of regulating phytoplankton standing stock and growth rates may have been food-limited. Growth of biomass in bivalves is accompanied by an increase in shell carbonate. The evolution of estuarine bivalve populations occurred over millennia in the absence of recent anthropogenic impacts including increased sediment and nutrient input, harvest of shellfish and general environmental degradation [32,33].

The depleted modern populations of the bay arguably cannot provide the ecosystem engineering that Pleistocene populations did. Nevertheless, records exist that have allowed estimation of both current shell reservoirs for mid-Atlantic oysters [83] and shell production in extant populations. Powell et al. [87] and Powell & Klinck [98] discussed the half-life of oyster shells with respect to the estuarine salinity gradient, while comparisons in Mann & Powell [10] emphasize the differing dynamics of shell production versus shell loss, which is driven by physical, chemical and biological components of the taphonomic process [99].

Simulations suggest that modern mid-Atlantic reefs accrete only when populations approach carrying capacity, with limited additional opportunity to support harvesting [100]. By contrast, Gulf of Mexico reefs, and presumably Pleistocene reefs, may have been able to both accrete and support a minor fishery. Powell et al. [100] used simulations to argue that reefs have an inherent protective mechanism, which limits volumetric shell content in the taphonomically active zone, and ensures that erosion of the underlying reef framework does not occur. According to Powell et al. [100, p. 543], reef recession only occurs in periods of ‘an inordinately unbalanced shell carbonate budget’. Indeed, many formerly productive reefs in the Chesapeake Bay, their resident population annihilated by harvesting and disease, remain as somewhat intact footprints that are slowly being subsumed by sedimentation.

The current combination of eutrophication, commercial exploitation and acidification has resulted in major reductions in the alkalinity reservoir in the Maryland Chesapeake Bay [83]. This same situation is reflected worldwide in other estuaries with long exploited shellfish populations. Borges & Gypensb [101] noted that carbonate chemistry in the coastal zone responds more strongly to eutrophication than to ocean acidification. Modern efforts in intensive oyster aquaculture, often pursued to carrying capacity of local embayments and estuaries, provide no contribution to the maintenance of alkalinity reservoirs or carbon burial. All biogenic carbonate is harvested while the accumulated biodeposits create challenges for both benthic eutrophication and shellfish farm management [102,103].

These studies underscore the challenge for ecosystem engineering in modern populations when truncation in oyster age and size leads to rapid turnover of exposed carbonate. In an evolutionary context, reef-building oysters can thrive even with rapid turnover rates of carbonate, as long as accretion accommodates sea-level rise [33,40,81]. In current degraded systems, rapid rebuilding to pre-colonial status may not be within the evolutionary scope of C. virginica [10]. These differences between past and present accretion dynamics highlight the fragile situation throughout the modern mid-Atlantic where reefs that accumulated over thousands of years have been depleted catastrophically in decades.

(e). Is the past a foreign country?

When viewed at human timescales, Chesapeake Bay oysters face seemingly overwhelming challenges that were effectively non-existent prior to colonial settlement of the mid-Atlantic region. Overharvesting, combined with disease, nutrient pollution and increased sedimentation rates, have obliterated these ecosystems, making it difficult to understand how populations can recover.

When considered over geological timescales, oyster habitats are ephemeral, appearing and disappearing as sea-level rises and falls over periods of tens to hundreds of thousands of years. Despite the fleeting nature of their environment, the oyster lineage stretches back millions of years, weathering multiple episodes of climate change, ocean acidification and even bolide impacts. The fossil record contains a wealth of information on how oysters have responded to a variety of stressors in the past, which can help us predict how they will respond in the future.

Using a conservation palaeobiological approach, we have demonstrated that Chesapeake Bay oysters are capable of growing to significantly larger sizes, longer lifespans and more abundant populations than previously recognized. These estimates of oyster size and abundance are substantially higher than current mitigation goals, suggesting that the latter are significantly affected by shifting baselines. Shifts in oyster population demographics have fundamental implications for ecosystem services, including filtration capacity and carbon burial. While Pleistocene oyster assemblages were capable of filtering and building three-dimensional habitat significantly faster and more effectively than modern oysters, their role in carbon cycling is still unclear.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our many colleagues at Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC), and Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MDDNR) notably Melissa Southworth, Mark Luckenbach, Lisa Kellogg, James Wesson, and Mitch Tarnowski, for their efforts in data collection, archiving and management. This research could not have been accomplished without the fieldwork and data collection of several W&M students, including Amanda Grant, Kris Kusnerik, Samantha Bonanni, Eric Dale, Josh Zimmt, Maggie Irwin, Caroline Abbott and Maddie Gaetano. Thanks to the Roane family, for providing generous access to the Holland Point field site; Buck Ward and Alex Hastings for access to the VMNH collections; and Rick Berquist, Kelvin Ramsey and Woody Hobbs for lengthy discussions on bay geology. This manuscript was greatly improved by revisions suggested by Sam Turvey, Greg Dietl and an anonymous reviewer.

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article are uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S3.

Authors' contributions

R.L. and R.M. conceived and designed the study, collected and compiled data, carried out the statistical analyses, wrote and revised the manuscript. Both authors gave final approval for publication and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Field data collection was supported by funds from the Commonwealth of Virginia to both VIMS and VMRC, additional support was provided by the Virginia Oyster Reef Heritage Foundation, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration award nos. NA66FU0487, NA07FU0539, NA17FU288 and NA11NMF4570226, Chesapeake Bay Trust contract number 14577, and Plumeri Awards for Faculty Excellence from the College of William and Mary to R.M. and R.L.

References

- 1.Jackson J, et al. 2001. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 293, 629–637. ( 10.1126/science.1059199) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirby MX. 2004. Fishing down the coast: historical expansion and collapse of oyster fisheries along continental margins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13 096–13 099. ( 10.1073/pnas.0405150101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck MW, et al. 2011. Oyster reefs at risk and recommendations for conservation, restoration, and management. Bioscience 61, 107–116. ( 10.1525/bio.2011.61.2.5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauly D. 1995. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10, 430 ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)89171-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coen L, Brumbaugh R, Bushek D, Grizzle R, Luckenbach M, Posey M, Powers S, Tolley S. 2007. Ecosystem services related to oyster restoration. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 341, 303–307. ( 10.3354/meps341303) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grabowski J.H., Brumbaugh RD, Conrad RF, Keeler AG, Opaluch JJ, Peterson CH, Piehler MF, Powers SP, Smyth AR. 2012. Economic valuation of ecosystem services provided by oyster reefs. Bioscience 62, 900–909. ( 10.1525/bio.2012.62.10.10) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.zu Ermgassen PSE, Spalding MD, Grizzle RE, Brumbaugh RD. 2013. Quantifying the loss of a marine ecosystem service: filtration by the eastern oyster in US estuaries. Estuaries Coasts 36, 36–43. ( 10.1007/s12237-012-9559-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy VS, Newell RIE, Eble AF. 1996. The eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Sea Grant Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann R. 2000. Restoring the oyster reef communities in the Chesapeake Bay: a commentary. J. Shellfish Res. 19, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann R, Powell EN. 2007. Why oyster restoration goals in the Chesapeake Bay are not and probably cannot be achieved. J. Shellfish Res. 26, 905–918. ( 10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26[905:WORGIT]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulte DM, Burke RP, Lipcius RN. 2009. Unprecedented restoration of a native oyster metapopulation. Science 325, 1124–1128. ( 10.1126/science.1176516) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy VS, et al. 2011. Lessons learned from efforts to restore oyster populations in Maryland and Virginia, 1990 to 2007. J. Shellfish Res. 30, 719–731. ( 10.2983/035.030.0312) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rick TC, Lockwood R. 2013. Integrating paleobiology, archeology, and history to inform biological conservation. Conserv. Biol. 27, 45–54. ( 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01920.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rick TC, et al. 2016. Millennial-scale sustainability of the Chesapeake Bay Native American oyster fishery. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 6568–6573. ( 10.1073/pnas.1600019113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirby MX, Miller HM. 2005. Response of a benthic suspension feeder (Crassostrea virginica Gmelin) to three centuries of anthropogenic eutrophication in Chesapeake Bay. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 62, 679–689. ( 10.1016/j.ecss.2004.10.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusnerik KM, Lockwood R, Grant AN. 2018. Using the fossil record to establish a baseline and recommendations for oyster mitigation in the mid-Atlantic U.S. In Marine conservation paleobiology (eds Tyler CL, Schneider CL), pp. 75–103. Berlin, Germany: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrews JD. 1996. History of Perkinsus marinus, a pathogen of oysters in Chesapeake Bay 1950–1984. J. Shellfish Res. 15, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burreson EM, Ragone Calvo LM. 1996. Epizootiology of Perkinsus marinus disease of oysters in Chesapeake Bay, with emphasis on data since 1985. J. Shellfish Res. 15, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson J, et al. 2004. Nonnative oysters in the chesapeake Bay. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hargis WJ, Haven DS. 1999. Chesapeake oyster reefs, their importance, destruction and guidelines for restoring them. In Oyster reef habitat restoration: a synopsis and synthesis of approaches (eds Luckenbach MW, Mann R, Wesson JA), pp. 329–358. Gloucester Point, VA: Virginia Institute of Marine Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilberg M, Livings M, Barkman J, Morris B, Robinson J. 2011. Overfishing, disease, habitat loss, and potential extirpation of oysters in upper Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 436, 131–144. ( 10.3354/meps09161) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newell RIE. 1988. Ecological changes in the Chesapeake Bay: are they the result of overharvesting the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica? Underst. Estuary Adv. Chesap. Bay Res. 129, 536–546. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesapeake Bay Foundation. 2019. Federal funding for the Chesapeake Bay Program. See https://www.cbf.org/about-cbf/locations/washington-dc/issues/federal-funding-for-the-chesapeake-bay-program.html (accessed on 31 March 2019).

- 24.Southworth M, Harding J, Mann R. 2000. The status of Virginia's public oyster resource 1999. Virginia Mar. Resour. Rep. 2, 45 ( 10.21220/V5PW29) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Southworth M, Mann R. 1998. Oyster reef broodstock enhancement in the Great Wicomico River, Virginia. J. Shellfish Res. 17, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann R, Evans D. 1998. Estimation of oyster, Crassostrea virginica, standing stock, larval production, and advective loss in relation to observed recruitment in the James River, Virginia. J. Shellfish Res. 17, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartol IK, Mann R, Luckenbach M. 1999. Growth and mortality of oysters (Crassostrea virginica) on constructed intertidal reefs: effects of tidal height and substrate level. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 237, 157–184. ( 10.1016/S0022-0981(98)00175-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson C, Grabowski J, Powers S. 2003. Estimated enhancement of fish production resulting from restoring oyster reef habitat: quantitative valuation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 264, 249–264. ( 10.3354/meps264249) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers S, Peterson C, Grabowski J, Lenihan H. 2009. Success of constructed oyster reefs in no-harvest sanctuaries: implications for restoration. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 389, 159–170. ( 10.3354/meps08164) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mroch RM, Eggleston DB, Puckett BJ. 2012. Spatiotemporal variation in oyster fecundity and reproductive output in a network of no-take reserves. J. Shellfish Res. 31, 1091–1101. ( 10.2983/035.031.0420) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenihan HS, Peterson CH. 2002. Conserving oyster reef habitat by switching from dredging and tonging to diver-harvesting. Fish. Bull. 102, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothschild B, Ault J, Goulletquer P, Héral M. 1994. Decline of the Chesapeake Bay oyster population: a century of habitat destruction and overfishing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 111, 29–39. ( 10.3354/meps111029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann R, Harding JM, Southworth MJ. 2009. Reconstructing pre-colonial oyster demographics in the Chesapeake Bay, USA. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 85, 217–222. ( 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.08.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy VS, Breisch LL. 1983. Sixteen decades of political management of the oyster fishery in Maryland's Chesapeake Bay. J. Environ. Manage. 164, 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harding JM, Mann R, Southworth MJ. 2008. Shell length-at-age relationships in James River, Virginia, oysters (Crassostrea virginica) collected four centuries apart. J. Shellfish Res. 27, 1109–1115. ( 10.2983/0730-8000-27.5.1109) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sisson M, Kellogg L, Luckenbach M, Lipcius R, Colden A, Cornwell J, Fowens MV. 2011. Assessment of oyster reefs in Lynnhaven River as a Chesapeake Bay TMDL best management practice. Spec. Reports Appl. Mar. Sci. Ocean Eng. 429, 66 ( 10.21220/V52R0K) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford SE, Cummings MJ, Powell EN. 2006. Estimating mortality in natural assemblages of oysters. Estuaries Coasts 29, 361–374. ( 10.1007/BF02784986) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puckett BJ, Eggleston DB. 2012. Oyster demographics in a network of no-take reserves: recruitment, growth, survival, and density dependence. Mar. Coast. Fish. 4, 605–627. ( 10.1080/19425120.2012.713892) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plough LV, Shin G, Hedgecock D. 2016. Genetic inviability is a major driver of type III survivorship in experimental families of a highly fecund marine bivalve. Mol. Ecol. 25, 895–910. ( 10.1111/mec.13524) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mann R, Southworth M, Harding JM, Wesson JA. 2009. Population studies of the native eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, (Gmelin, 1791) in the James River, Virginia, USA. J. Shellfish Res. 28, 193–220. ( 10.2983/035.028.0203) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harding JM, Mann R, Southworth MJ, Wesson JA. 2010. Management of the Piankatank River, Virginia, in support of oyster (Crassostrea virginica, Gmelin 1791) fishery repletion. J. Shellfish Res. 29, 867–888. ( 10.2983/035.029.0421) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Southworth M, Harding JM, Wesson JA, Mann R. 2010. Oyster (Crassostrea virginica, Gmelin 1791) population dynamics on public reefs in the Great Wicomico River, Virginia, USA. J. Shellfish Res. 29, 271–290. ( 10.2983/035.029.0202) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oyster Metrics Workgroup. 2011. Restoration goals, quantitative metrics and assessment protocols for evaluating success on restored oyster reef sanctuaries. Report to the Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team. Chesapeake Bay Program, Annapolis, Maryland.

- 44.Lenihan HS, Peterson CH. 1998. How habitat degradation through fishery disturbance enhances impacts of hypoxia on oyster reefs. Ecol. Appl. 8, 128–140. ( 10.2307/2641316) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newell RIE, Koch EW. 2004. Modeling seagrass density and distribution in response to changes in turbidity stemming from bivalve filtration and seagrass sediment stabilization. Estuaries 27, 793–806. ( 10.1007/BF02912041) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grabowski JH, Peterson CH. 2007. Restoring oyster reefs to recover ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Eng. Plants Protists 4, 281–298. ( 10.1016/S1875-306X(07)80017-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipcius RN, Burke RP, McCulloch DN, Schreiber SJ, Schulte DM, Seitz RD, Shen J. 2015. Overcoming restoration paradigms: value of the historical record and metapopulation dynamics in native oyster restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 65 ( 10.3389/fmars.2015.00065) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fodrie FJ, Rodriguez AB, Gittman RK, Grabowski JH, Lindquist NL, Peterson CH, Piehler MF, Ridge JT. 2017. Oyster reefs as carbon sources and sinks. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170891 ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0891) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Officer C, Smayda T, Mann R. 1982. Benthic filter feeding: a natural eutrophication control. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 9, 203–210. ( 10.3354/meps009203) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulanowicz RE, Tuttle JH. 1992. The trophic consequences of oyster stock rehabilitation in Chesapeake Bay. Estuaries 15, 298–306. ( 10.2307/1352778) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hickey JP. 2009. Carbon sequestration potential of shellfish. See https://thefishsite.com/articles/carbon-sequestration-potential-of-shellfish (accessed on 31 March 2019).

- 52.Waldbusser GG, Steenson RA, Green MA. 2011. Oyster shell dissolution rates in estuarine waters: effects of pH and shell legacy. J. Shellfish Res. 30, 659–669. ( 10.2983/035.030.0308) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Filgueira R, et al. 2015. An integrated ecosystem approach for assessing the potential role of cultivated bivalve shells as part of the carbon trading system. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 518, 281–287. ( 10.3354/meps11048) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang Q, Zhang J, Fang J. 2011. Shellfish and seaweed mariculture increase atmospheric CO2 absorption by coastal ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 424, 97–104. ( 10.3354/meps08979) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peterson C, Lipcius R, Powers S. 2003. Conceptual progress towards predicting quantitative ecosystem benefits of ecological restorations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 264, 297–307. ( 10.3354/meps264297) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins CB, Stephenson K, Brown BL. 2011. Nutrient bioassimilation capacity of aquacultured oysters: quantification of an ecosystem service. J. Environ. Qual. 40, 271–277. ( 10.2134/jeq2010.0203) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ridge JT, Rodriguez AB, Fodrie FJ. 2017. Salt marsh and fringing oyster reef transgression in a shallow temperate estuary: implications for restoration, conservation and blue carbon. Estuaries Coasts 40, 1013–1027. ( 10.1007/s12237-016-0196-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Der Schatte Olivier A, Jones L, Le Vay L, Christie M, Wilson J, Malham SK.. 2018. A global review of the ecosystem services provided by bivalve aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 1–23. ( 10.1111/raq.12301) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller H. 1986. Transforming a ‘splendid and delightsome land’: colonists and ecological change in the Chesapeake 1607–1820. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 76, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller HM. 2001. Living along the ‘great shellfish bay’: the relationship between prehistoric peoples and the Chesapeake. In Discovering the Chesapeake: the history of an ecosystem (eds Curtin PD, Brush GS, Fisher GW), p. 10 Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lotze HK, Lenihan HS, Bourque BJ, Bradbury RH, Cooke RG, Kay MC, Kidwell SM, Kirby MX, Peterson C. 2006. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science 312, 1806–1809. ( 10.1126/science.1128035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lotze HK. 2010. Historical reconstruction of human induced changes in US estuaries. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 48, 265–336. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kent BW. 1992. Making dead oysters talk: techniques for analyzing oysters from archaeological sites. Crownsville, MD: Maryland Historical & Cultural Publications for Maryland Historical Trust, Historic St. Mary's City, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schulte DM. 2017. History of the Virginia oyster fishery, Chesapeake Bay, USA. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 127 ( 10.3389/fmars.2017.00127) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wharton J. 1957. The bounty of the Chesapeake: fishing in colonial virginia. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harding JM, Spero HJ, Mann R, Herbert GS, Sliko JL. 2010. Reconstructing early 17th century estuarine drought conditions from Jamestown oysters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10 549–10 554. ( 10.1073/pnas.1001052107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waselkov GA. 1982. Shellfish gathering and shell midden archaeology. Chapel Hill, CA: University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith G., Roach E., Bruce D. 2003. The location, composition, and origin of oyster bars in mesohaline Chesapeake Bay. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 56, 391–409. ( 10.1016/S0272-7714(02)00191-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hobbs CH. 2004. Geological history of Chesapeake Bay, USA. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 641–661. ( 10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2003.08.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dietl GP, Flessa KW. 2011. Conservation paleobiology: putting the dead to work. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 30–37. ( 10.1016/J.TREE.2010.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dietl GP. 2016. Brave new world of conservation paleobiology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 4, 21 ( 10.3389/fevo.2016.00021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zimmt JB, Lockwood R, Andrus CFT, Herbert GS. 2019. Sclerochronological basis for growth band counting: a reliable technique for life-span determination of Crassostrea virginica from the mid-Atlantic United States. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 516, 54–63. ( 10.1016/J.PALAEO.2018.11.029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Virginia Institute of Marine Science. 2019. VOSARA: Virginia Oyster Stock Assessment and Replenishment Archive. See http://cmap2.vims.edu/VOSARA/viewer/VOSARA.html (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- 74.Kidwell SM. 1997. Time-averaging in the marine fossil record: overview of strategies and uncertainties. Geobios 30, 977–995. ( 10.1016/S0016-6995(97)80219-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mann R, Southworth M, Harding JM, Wesson J. 2004. A comparison of dredge and patent tongs for estimation of oyster populations. J. Shellfish Res. 23, 387–391. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Powell EN, Hofmann EE, Klinck JM, Ray SM. 1992. Modeling oyster populations: I. A commentary on filtration rate. Is faster always better? J. Shellfish Res. 11, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Powell EN, Mann R, Ashton-Alcox KA, Kim Y, Bushek D. 2016. The allometry of oysters: spatial and temporal variation in the length–biomass relationships for Crassostrea virginica. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 96, 1127–1144. ( 10.1017/S0025315415000703) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Powell EN, Cummins H. 1985. Are molluscan maximum life spans determined by long-term cycles in benthic communities? Oecologia 67, 177–182. ( 10.1007/BF00384281) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kirby MX. 2000. Paleoecological differences between Tertiary and Quaternary Crassostrea oysters, as revealed by stable isotope sclerochronology. Palaios 15, 132–141. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Virginia Fisheries Laboratory. 1949–1959 Report of the Virginia Fisheries Laboratory, biennial reports; 1951, 1953, 1955, 1957, 1959, Gloucester, VA. See https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsannualrpt/.

- 81.Walles B, Mann R, Ysebaert T, Troost K, Herman PMJ, Smaal AC. 2015. Demography of the ecosystem engineer Crassostrea gigas, related to vertical reef accretion and reef persistence. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 154, 224–233. ( 10.1016/J.ECSS.2015.01.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luckenbach MW, Coen LD, Ross P, Stephen JA. 2005. Oyster reef habitat restoration: relationships between oyster abundance and community development based on two studies in Virginia and South Carolina. J. Coast. Res. 40, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Waldbusser GG, Powell EN, Mann R. 2013. Ecosystem effects of shell aggregations and cycling in coastal waters: an example of Chesapeake Bay oyster reefs. Ecology 94, 895–903. ( 10.1890/12-1179.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cai W-J, et al. 2017. Redox reactions and weak buffering capacity lead to acidification in the Chesapeake Bay. Nat. Commun. 8, 369 ( 10.1038/s41467-017-00417-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Duarte CM, Middelburg JJ, Caraco N. 2004. Major role of marine vegetation on the oceanic carbon cycle. Biogeosciences 2, 1–8. ( 10.5194/bg-2-1-2005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nellemann C, Corcoran E, Duarte CM, Valdes L, DeYoung C, Fonseca L, Grimsditch GD. 2009. Blue carbon: the role of healthy oceans in binding carbon. UN Environment, GRID-Arendal.

- 87.Powell EN, Kraeuter JN, Ashton-Alcox KA. 2006. How long does oyster shell last on an oyster reef? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 69, 531–542. ( 10.1016/j.ecss.2006.05.014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stenzel HB. 1971. Oysters. In Treatise on invertebrate paleontology, pt. N, vol. 3, mollusca 6, bivalvia (ed. Moore R.), pp. 953–1224. Lawrence, KS: Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kirby MX. 2001. Differences in growth rate and environment between Tertiary and Quaternary Crassostrea oysters. Paleobiology 27, 84–103. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rodriguez AB, et al. 2014. Oyster reefs can outpace sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 493–497. ( 10.1038/nclimate2216) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Levitan DR. 1991. Influence of body size and population density on fertilization success and reproductive output in a free-spawning invertebrate. Biol. Bull. 181, 261–268. ( 10.2307/1542097) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levitan DR, Sewell MA, Chia F-S. 1992. How distribution and abundance influence fertilization success in the sea urchin Strongylocentotus franciscanus. Ecology 73, 248–254. ( 10.2307/1938736) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levitan DR, Young CM. 1995. Reproductive success in large populations: empirical measures and theoretical predictions of fertilization in the sea biscuit Clypeaster rosaceus. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 190, 221–241. ( 10.1016/0022-0981(95)00039-T) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Seliger HH, Boggs JA, Biggley WH. 1985. Catastrophic anoxia in the Chesapeake Bay in 1984. Science 228, 70–73. ( 10.1126/science.228.4695.70) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seed R, Suchanek T. 1992. Population and community ecology of Mytilus. In The mussel mytilus: ecology, physiology, genetics and culture (ed. Gosling E.), pp. 87–170. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eggleston DB, Elis WE, Etherington LL, Dahlgren CP, Posey MH. 1999. Organism responses to habitat fragmentation and diversity: habitat colonization by estuarine macrofauna. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 236, 107–132. ( 10.1016/S0022-0981(98)00192-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schröder-Adams C. 2006. Estuaries of the past and present: a biofacies perspective. Sediment. Geol. 190, 289–298. ( 10.1016/J.SEDGEO.2006.05.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Powell EN, Klinck JM. 2007. Is oyster shell a sustainable estuarine resource? J. Shellfish Res. 26, 181–194. ( 10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26[181:IOSASE]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Davies DJ, Powell EN, Stanton RJ Jr. 1989. Relative rates of shell dissolution and net sediment accumulation—a commentary: can shell beds form by the gradual accumulation of biogenic debris on the sea floor? Lethaia 22, 207–212. ( 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1989.tb01683.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Powell EN, Klinck JM, Ashton-Alcox K, Hofmann EE, Morson J. 2012. The rise and fall of Crassostrea virginica oyster reefs: the role of disease and fishing in their demise and a vignette on their management. J. Mar. Res. 70, 505–558. ( 10.1357/002224012802851878) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Borgesa AV, Gypensb N. 2010. Carbonate chemistry in the coastal zone responds more strongly to eutrophication than ocean acidification. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 346–353. ( 10.4319/lo.2010.55.1.0346) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tenore K, et al. 1982. Coastal upwelling in the Rias Bajas, NW Spain: contrasting the benthic regimes of the Rias de Arosa and de Muros. J. Mar. Res. 40, 701–772. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Grant J, Hatcher A, Scott DB, Pocklington P, Schafer CT, Winters GV. 1995. A multidisciplinary approach to evaluating impacts of shellfish aquaculture on benthic communities. Estuaries 18, 124–144. ( 10.2307/1352288) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article are uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S3.