Abstract

A common approach when studying inequalities in health is to use a wealth index based on household durable goods as a proxy for socio-economic status. We test this approach for elderly health using data from an aging survey in a rural area of South Africa and find much steeper gradients for health with consumption adjusted for household size than with the wealth index. These results highlight the importance of the measure of socioeconomic status used when measuring health gradients, and the need for direct measures of household consumption or income in ageing studies.

Keywords: Health and Inequality, Ageing, South Africa

1. Introduction

There is strong evidence for the existence of important gradients in health outcomes by socioeconomic status in most countries [1–4]. These inequalities have been remarkably persistent in the face of policy actions that try to reduce inequality [5–7] and there has been a call for improved policies to address and reduce health inequalities [8–10]. In principle, health inequality could be defined as the differences in health across people [11] in much the same way as income inequality is defined as the differences in income across people. However, in social epidemiology, health inequality is usually defined in terms of differences in health across different socio-economic groups, that is, the gradient in health with socioeconomic status [12].

This raises the issue of how to measure socio-economic status and a variety of approaches have been developed in the literature. A natural approach is to use household income as a metric. However measuring household income in surveys from developing countries is difficult. As a consequence, studies concerning child health have relied on a wealth index based on housing characteristics and ownership of consumer durables [13]. The use of this proxy measure has been based on the argument that the wealth index is highly correlated with household income per capita and that child health gradients are similar with both socioeconomic measures. Subsequent studies have confirmed that while the relationship between households ranked by quintiles of wealth and consumption measures is imperfect, child health gradients are similar in both approaches [14]. However more recent studies show that gradients in health care utilization may differ using the two approaches [15] and that the exact composition of the assets used to construct the index matters [16, 17].

The wealth index approach to measuring socioeconomic status has been mainly used in child health studies. However, recent studies have explored adult health gradients using a household wealth index and found either no, or only a very small gradient, in many countries [18–25]. This conclusion has potentially important consequences for how we think about the health of the elderly and health policy. However, unlike the case of child health there has been little evaluation of how the health gradient using the wealth index compares to gradients in household income or consumption for adult and elderly health.

To address this issue, we use data from the first wave of the Health and Aging in Africa: A longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa (HAALSI) that provides data on health outcomes, household consumption, and the household wealth index, to compare health gradients using different measures of socioeconomic status. We model our approach closely on previous work on this population by Gomez-Olive et al. [25] to provide comparability to our results. We construct three different summary measures of health and disability status; each based on a different collection of health variables. We measure socioeconomic status using household consumption adjusted for household size. There is an issue that consumption per capita may not be a good measure of household socioeconomic status if some consumption goods are shared within the family, and there are economies of scale in household consumption. Wagstaff and Watanabe [14] suggest equivalent consumption, defined as consumption divided by the square root of household size, as a better indicator of household wellbeing. We find much stronger health gradients in equivalent consumption than consumption per capita.

While there is evidence of a mortality gradient with the wealth index [26], previous work in Agincourt [25] finds a shallow adult health gradient in the wealth index when not adjusting for the other covariates, and no gradient when adjusting for covariates. From a policy perspective the adjusted gradient is more important. Some of the unadjusted health gradient may be due to the correlation of socioeconomic status with exogenous personal characteristics that affect health, for example, sex, age, marital status, and national origin, which are unlikely to be affected by policies. In our analysis we also adjust the gradient for education status. There may be very long run policies to reduce health inequality in the elderly by equalizing educational opportunities; by controlling for education we rule this out and focus on the potential effect of policies that address inequality in the current generation of elderly whose education levels can be considered fixed. This is the appropriate adjustment to find the potential impact of polices, such as pensions social grants, that redistribute income and consumption to the elderly [27–29].

Our result undermines the use of the wealth index alone as a proxy for household consumption when studying health gradients in adult and elderly health. We find much steeper gradients in health in equivalent consumption, than in the wealth index, suggesting the potential for a much larger health impact for policies that redistribute income. Further, our results emphasize the need for studies that collect detailed household consumption data, as well as recording the asset holdings needed for the wealth index.

2. Methods

In this study we use data on the elderly from the first wave of the Health and Aging in Africa: A longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa (HAALSI) study. HAALSI is a sister study to the Health and Retirement Study that collected data on 5,059 respondents-a 85.9% response rate- aged 40 and older living permanently in the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance Site (DSS). This interdisciplinary survey collected data on household economic conditions, demographics, employment, social conditions, and health, in a face-to-face interview and a detailed description is available in the cohort profile [30].

We construct three summary health measures for individuals in the dataset. These are constructed by aggregating a number of health conditions using principle components analysis (PCA), taking the first principle component to give weights on each condition. Each measure is a weighted average of health conditions where higher values for each condition imply better health, and all the weights are positive. We use this approach to combine different indicators of health into a summary measure that represents the latent health of an individual in line with the ageing literature [31, 32]. The foundation for this approach has been discussed widely in the literature and addresses the differential responses to different health questions due to cultural norms [33]. Furthermore, most studies evaluating health inequalities rely on a latent measure of health to enhance comparability across time and countries [34, 35].

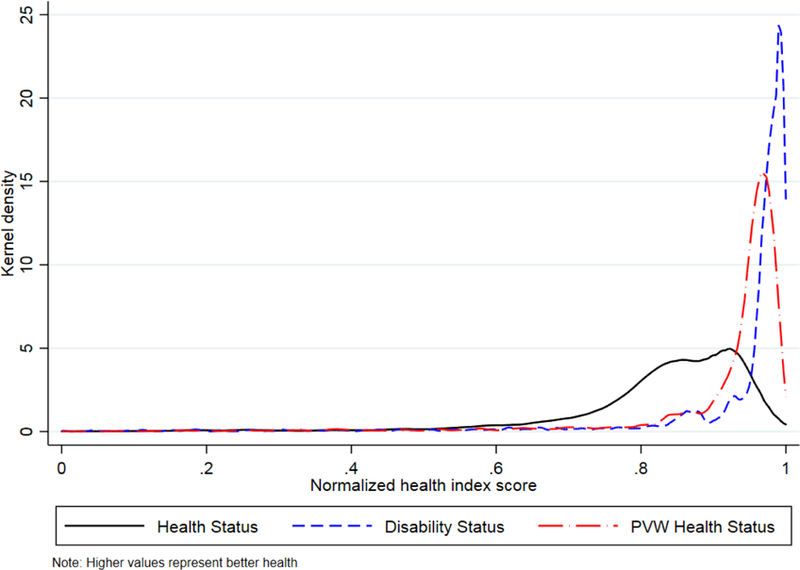

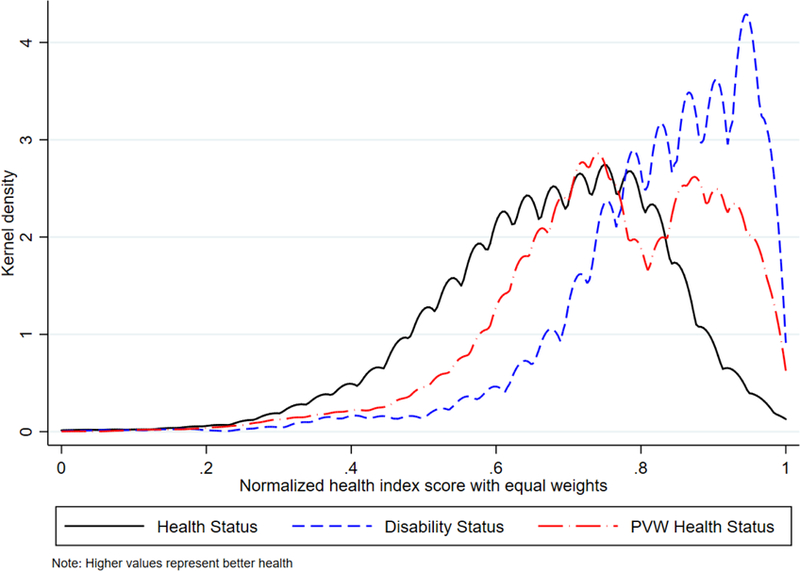

The first health measure, health status, covers the following health domains: mobility, self-care, pain and discomfort, cognition, interpersonal activities, affect, and vision. The construction of this measure is based and replicates that used by a series of studies on elderly health using WHO-SAGE data [18–25]. Our second health index, disability status, is based on the WHO disability assessment schedule [36], and includes information on individual disabilities. Our third health index PVW Health Status is constructed using the health measures proposed by Poterba, Venti and Wise [32] based on self-reported health, mobility, doctor diagnosis, health conditions, and health care utilization. This measure has been widely used in the literature and provides a valuable summary measure of health at older ages [31, 33]. For all three indices, higher index scores indicate better health. Appendix Table 1 provides details of the variables and weights used to construct each of the three health indices. Figure 1 shows the distribution of our three health indicators in the population. The differences observed across the health indices reflect the different variables used to construct each one of them. While our indexes take on a range of values, for our analysis, we follow the approach used by Gomez-Olive et al. [25] and group each health measure into two categories- good and bad health- where the top two quintiles are defined to be good health.

Figure 1.

Distribution of health indices

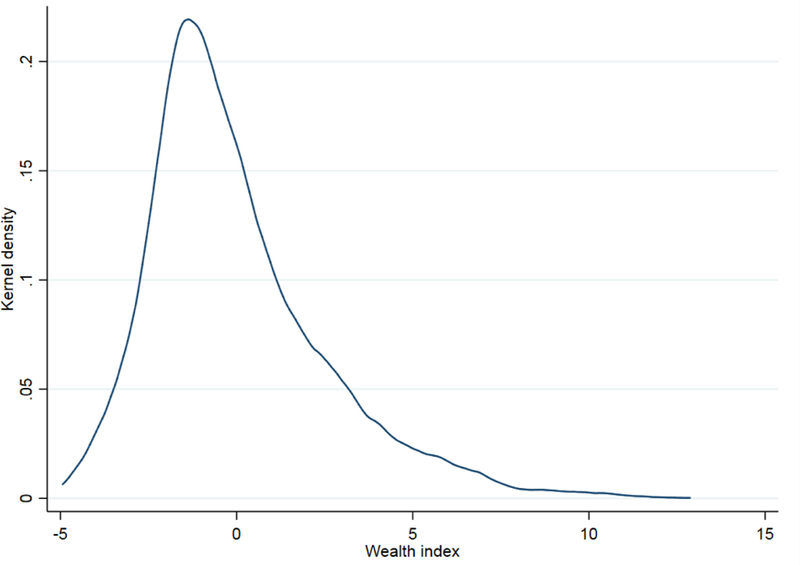

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all the variables used in our study including our health measures, but also socioeconomic status measures, gender, age group, education level, marital status, employment and national origin. To measure socioeconomic status, we use three indicators, a wealth index, household consumption per capita, and household equivalent consumption. To construct the wealth index, we again undertake a principle components analysis on a set of household variables made up of ownership of consumer durables, livestock, and housing characteristics. We use the first principle component to produce weights. We follow the DHS methodology by identifying assets where variation exists across the households, and then estimating the weights for each of the asset categories using PCA [37]. Appendix Table 1 presents the variables used the construction of the wealth index, with their scoring coefficients. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the wealth index in the sample. In the analysis we use the quintiles of this distribution to study health gradients.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of sample

| Number in group | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2714 | 0.536 | 0.499 |

| Male | 2345 | 0.464 | 0.499 |

| Age group | |||

| 40–49 | 918 | 0.181 | 0.385 |

| 50–59 | 1410 | 0.279 | 0.448 |

| 60–69 | 1304 | 0.258 | 0.437 |

| 70–79 | 878 | 0.174 | 0.379 |

| 80+ | 549 | 0.109 | 0.311 |

| Education | |||

| No formal education | 2306 | 0.457 | 0.498 |

| Some primary (1–7 years) | 1614 | 0.320 | 0.467 |

| Some secondary (8–11 years) | 537 | 0.107 | 0.309 |

| Secondary or more (12+ years) | 585 | 0.116 | 0.320 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Never married | 290 | 0.057 | 0.233 |

| Separated / divorced | 650 | 0.129 | 0.335 |

| Widowed | 1540 | 0.305 | 0.460 |

| Currently married | 2575 | 0.509 | 0.500 |

| Occupation status | |||

| Working | 805 | 0.160 | 0.366 |

| Not working | 4240 | 0.840 | 0.366 |

| Born in South Africa | |||

| No | 1526 | 0.302 | 0.459 |

| Yes | 3528 | 0.698 | 0.459 |

| Health indices | |||

| Normalized health status | 0.828 | 0.136 | |

| Normalized disability status | 0.934 | 0.139 | |

| Normalized PVW health status | 0.918 | 0.126 | |

| Socioeconomic measures | |||

| Monthly household consumption per capita (in Rands) | 775.43 | 1086.91 | |

| Equivalent monthly household consumption (in Rands) | 1462.43 | 1920.26 | |

| Wealth index | 0.066 | 2.545 | |

| Observations | 5059 | ||

Figure 2.

Distribution of asset-based wealth index score in HAALSI

Household consumption is constructed from a detailed questionnaire on consumption of a variety of different categories of goods, including the household’s own production and use as well as purchases. Consumption was chosen rather than current household income because it represents the living standard of a household and accounts for inter-temporal cash transfers and can be regarded as a measure of long run or permanent income for the household if it smooths consumption over short run income shocks [38]. In addition, the household income data in HAALSI has missing values in many cases for the labor income of household members who are not the financial respondent, while the consumption data is more complete.

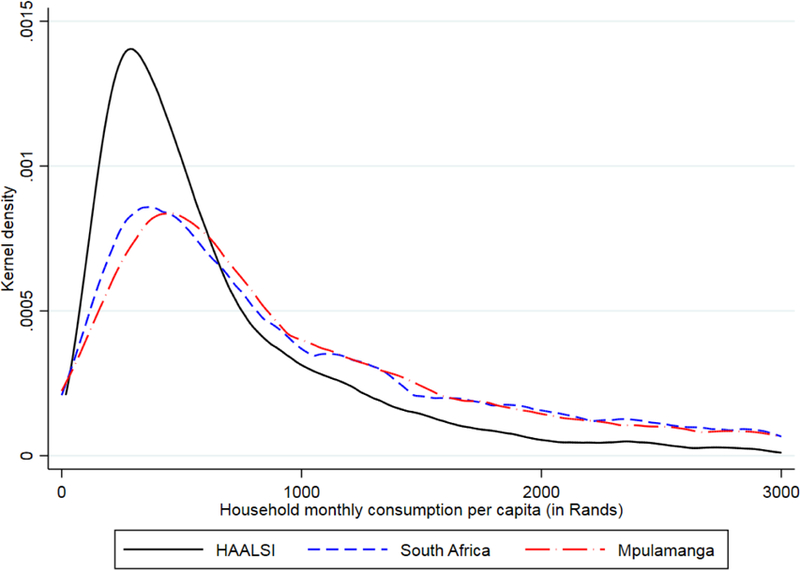

A simple approach is to measure socioeconomic status by household consumption per capita. This assumes no economies of scale within a household [39]. It may well be that some consumption reflects household public goods and adding additional household members does not affect the consumption of these goods by existing members. We also follow Wagstaff and Watanabe [14] and scale household consumption by the square root of household size to give equivalent consumption that adjust for economies of scale. Our two measures are therefore consumption per capita, and equivalent consumption measured as consumption divided by the square root of household size. The distribution of monthly household consumption per capita in the sample is presented in Figure 3, as well as the distribution for the Mpulamanga region in which the Agincourt DSS is located, and for the whole country of South Africa, using data form the 2013 South African General Household Survey [40]. As can be seen in Figure 3, the Agincourt area in which HAALSI is conducted is a poor rural area and consumption per capita is considerably lower in the HAALSI sample than in South Africa or the Mpulamanga region.

Figure 3.

Distribution of consumption per capita in HAALSI and from National Income Dynamics Survey in South Africa

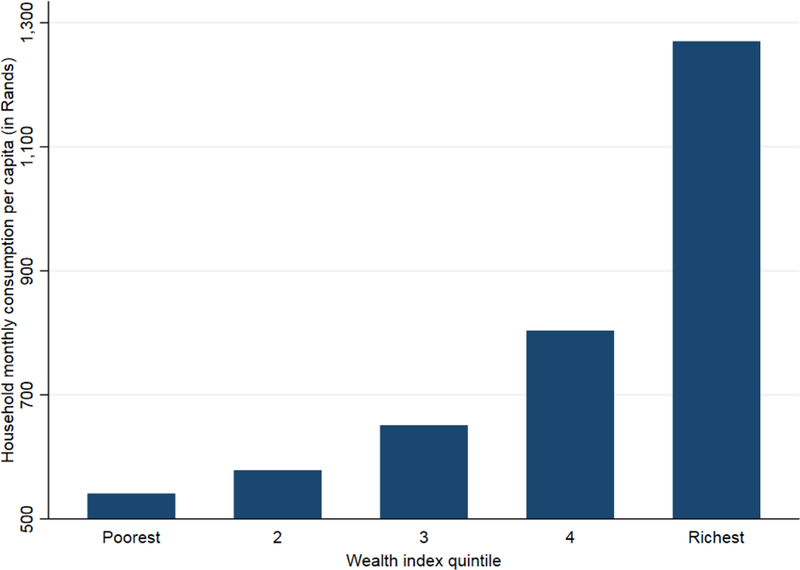

Figure 4 shows the average monthly consumption per capita by wealth index quintile. As expected, households in the higher wealth quintiles have higher average consumption per capita. Appendix Table 3 shows a correlation matrix between our three health indicators and three measures of socioeconomic status. This correlation matrix shows that consumption per capita and equivalent consumption are very highly correlated, a correlation coefficient of 0.909, while their correlation with the wealth index is quite low. Health status and disability status have a correlation coefficient of 0.732 while PVW health status has a weaker correlation with these two. There is quite a low level of correlation between the health indicators and our socioeconomic measures, though for each health indicator the highest correlation is between health and equivalent consumption.

Figure 4.

Relationship between average household monthly consumption per capita and the wealth index quintile

The low correlation between the wealth index and consumption per capita is highlighted in Table 2 which shows the distribution of households in cross tabulation of households by quintile of the wealth index with quintile of consumption per capita. While the wealth index and consumption per capita are correlated, there are many households off the diagonal elements that are ranked differently on the two criteria. Indeed, some households ranked in the lowest quintile on one measure are in the highest on the other. Table 3 shows a similar pattern for quintiles of equivalent consumption and the wealth index.

Table 2.

Consistency in rankings between consumption per capita and wealth index

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (Lowest) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th (Highest) | |

| Wealth index | |||||

| 1st (Lowest) | 5.99 | 4.41 | 3.70 | 3.14 | 1.98 |

| 2nd | 5.24 | 4.45 | 3.66 | 3.83 | 2.57 |

| 3rd | 4.17 | 4.70 | 4.33 | 3.95 | 2.83 |

| 4th | 3.26 | 3.85 | 4.49 | 4.13 | 4.45 |

| 5th (Highest) | 1.98 | 2.77 | 3.97 | 4.29 | 7.87 |

Values represent percentage of total sample.

Table 3.

Consistency in rankings between equivalent consumption and wealth

| Equivalent consumption quintiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (Lowest) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th (Highest) | |

| Wealth index | |||||

| 1st (Lowest) | 7.51 | 5.10 | 3.48 | 2.13 | 1.01 |

| 2nd | 5.59 | 4.29 | 4.21 | 3.93 | 1.78 |

| 3rd | 3.40 | 4.88 | 4.90 | 3.93 | 2.81 |

| 4th | 2.31 | 3.46 | 4.25 | 5.08 | 5.08 |

| 5th (Highest) | 1.11 | 2.25 | 3.00 | 4.82 | 9.67 |

Values represent percentage of total sample

The descriptive statistics reported in Table 1 also show the distribution of our covariates. There are more females than males amongst the respondents, and the largest group is between the ages of 50 and 59. In terms of education, more than half of the sample have less than primary schooling with the largest group of these having no education at all. Furthermore, a significant fraction of the sample was not born in South Africa. Agincourt is close to the border with Mozambique, and during the civil war from 1977 to 1992 many refugees crossed the border and have since settled in the area.

3. Results

Our approach is to examine the gradient of health in socioeconomic status conditional on demographic characteristics given by sex, age, education level, marital status, and country of birth. To allow comparison to previous work in Agincourt [25], we follow the same approach and use a logistic regression to evaluate the association between quintiles of socioeconomic status and being in the top two quintiles of health. In our models, like those in the literature, we control for gender, age, marital status, education level, nationality of origin, and occupational status. This approach replicates the methods used in past SAGE studies to evaluate health inequalities [18–25]. The difference in our approach is that we have data on both consumption and wealth so we can therefore compare the gradients across the different socioeconomic measures. Another difference is that we present results for a model where we combine both socioeconomic measures to evaluate whether the gradients in a socioeconomic measure remain once we have controlled for the other. An alternative approach would be to use concentration indices as in Wagstaff and Watanabe [14], but this approach does not measure the gradient directly.

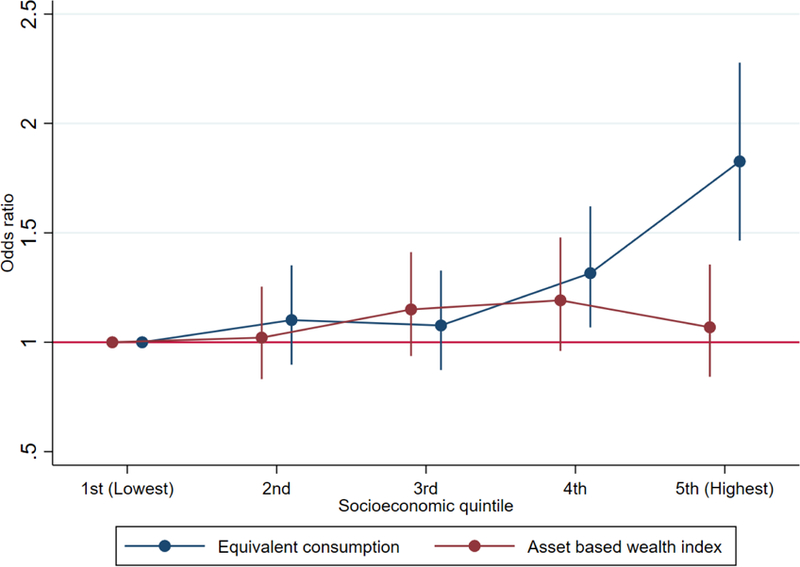

Results comparing the wealth index and equivalent consumption as measures of socioeconomic status are reported in Table 4. For health status, in columns 1 to 3 we find health gradients in both equivalent consumption and the wealth index. As shown in column 1, health status is higher for those with higher equivalent consumption, particularly those in the highest two quintiles of equivalent consumption. Health status also rises with the wealth index, being significantly higher in the third, fourth, and fifth, quintiles relative to the first, poorest, quintile. However, the health gradient is much steeper in equivalent consumption than in the wealth index, with the highest equivalent consumption quintile having an odds ratio of 1.891 of good health status relative the lowest quintile, while the corresponding odds ratio for the wealth index is only 1.346. This means that an individual in the highest equivalent consumption quintile is 89.1% more likely to be in good health than someone in the lowest equivalent consumption quintile, while someone in the highest asset quintile is only 34.6% more likely to be in good health than one in the lowest asset quintile. This shows how steeper the gradient is when measured by equivalent consumption than when measured by the wealth asset index. Column 3 adds both our socioeconomic status variables together, as can be seen the gradient in equivalent consumption remains while that in the wealth index disappears. The results in column 3 of Table 4 are shown graphically in Figure 5 which shows the estimated gradients of health status with the wealth index and equivalent consumption. Following the same interpretation as before, an individual in the highest quintile of equivalent consumption is 82.6% more likely to be in good health than one in the lowest quintile of equivalent consumption, controlling for the wealth assets. While, being in the highest asset index quintile is only 6.8% more likely to be in good health than someone in the lowest asset quintile.

Table 4.

Logistic regression odds ratios for the health indices comparing equivalent consumption and the asset-based wealth index

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 1.146* | 1.171* | 1.158* | 1.041 | 1.061 | 1.047 | 1.097 | 1.105 | 1.091 |

| (1.009–1.302) | (1.031–1.331) | (1.018–1.316) | (0.915–1.184) | (0.932–1.207) | (0.920–1.193) | (0.965–1.248) | (0.972–1.256) | (0.959–1.241) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | 0.577*** | 0.571*** | 0.573*** | 0.724*** | 0.712*** | 0.721*** | 0.585*** | 0.588*** | 0.592*** |

| (0.482–0.690) | (0.477–0.683) | (0.478–0.686) | (0.606–0.864) | (0.596–0.850) | (0.603–0.861) | (0.489–0.699) | (0.493–0.703) | (0.495–0.708) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | 0.500*** | 0.502*** | 0.495*** | 0.560*** | 0.572*** | 0.558*** | 0.507*** | 0.526*** | 0.518*** |

| (0.409–0.610) | (0.411–0.613) | (0.405–0.604) | (0.459–0.684) | (0.468–0.699) | (0.456–0.682) | (0.415–0.618) | (0.431–0.642) | (0.423–0.633) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | 0.355*** | 0.355*** | 0.351*** | 0.412*** | 0.420*** | 0.412*** | 0.359*** | 0.370*** | 0.366*** |

| (0.282–0.446) | (0.282–0.446) | (0.279–0.441) | (0.327–0.520) | (0.333–0.530) | (0.327–0.520) | (0.286–0.451) | (0.295–0.465) | (0.291–0.460) | |

| Age group: 80+ | 0.197*** | 0.199*** | 0.195*** | 0.217*** | 0.223*** | 0.216*** | 0.183*** | 0.189*** | 0.185*** |

| (0.147–0.264) | (0.148–0.267) | (0.145–0.262) | (0.159–0.295) | (0.164–0.302) | (0.159–0.293) | (0.136–0.246) | (0.140–0.254) | (0.137–0.248) | |

| Education: Some primary | 1.131 | 1.131 | 1.118 | 1.200* | 1.218* | 1.195* | 1.121 | 1.153 | 1.136 |

| (0.972–1.317) | (0.970–1.318) | (0.959–1.304) | (1.027–1.404) | (1.042–1.425) | (1.021–1.400) | (0.960–1.308) | (0.987–1.347) | (0.972–1.329) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 1.203 | 1.214 | 1.186 | 1.332* | 1.379** | 1.337* | 1.392** | 1.466*** | 1.429** |

| (0.961–1.505) | (0.968–1.522) | (0.946–1.487) | (1.063–1.670) | (1.099–1.729) | (1.064–1.679) | (1.114–1.738) | (1.172–1.833) | (1.141–1.790) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 1.012 | 1.088 | 1.004 | 1.097 | 1.211 | 1.112 | 0.977 | 1.128 | 1.032 |

| (0.804–1.274) | (0.862–1.374) | (0.793–1.270) | (0.870–1.382) | (0.960–1.529) | (0.878–1.407) | (0.775–1.231) | (0.892–1.426) | (0.815–1.307) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 1.124 | 1.154 | 1.129 | 1.273 | 1.305 | 1.278 | 1.148 | 1.166 | 1.135 |

| (0.833–1.516) | (0.858–1.553) | (0.836–1.524) | (0.939–1.727) | (0.964–1.767) | (0.942–1.734) | (0.850–1.550) | (0.864–1.571) | (0.840–1.534) | |

| Marital Status: Widowed | 1.052 | 1.057 | 1.040 | 1.185 | 1.191 | 1.178 | 1.109 | 1.134 | 1.112 |

| (0.785–1.409) | (0.791–1.412) | (0.775–1.394) | (0.880–1.595) | (0.886–1.601) | (0.875–1.587) | (0.830–1.483) | (0.849–1.514) | (0.831–1.489) | |

| Marital Status: Currently married | 1.481** | 1.463** | 1.451** | 1.528** | 1.528** | 1.521** | 1.400* | 1.453** | 1.434** |

| (1.136–1.931) | (1.124–1.906) | (1.110–1.896) | (1.167–1.999) | (1.166–2.002) | (1.159–1.996) | (1.075–1.822) | (1.116–1.893) | (1.098–1.871) | |

| Working | 1.560*** | 1.617*** | 1.559*** | 1.388*** | 1.450*** | 1.389*** | 1.772*** | 1.846*** | 1.781*** |

| (1.314–1.852) | (1.363–1.919) | (1.313–1.851) | (1.172–1.644) | (1.224–1.717) | (1.172–1.646) | (1.491–2.106) | (1.554–2.192) | (1.498–2.117) | |

| Born in South Africa | 1.059 | 1.065 | 1.045 | 0.950 | 0.971 | 0.943 | 0.809** | 0.838* | 0.821* |

| (0.910–1.232) | (0.915–1.240) | (0.897–1.217) | (0.814–1.108) | (0.832–1.132) | (0.807–1.102) | (0.697–0.940) | (0.721–0.973) | (0.707–0.955) | |

| Equivalent consumption quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.124 | 1.101 | 1.454*** | 1.439*** | 1.196 | 1.206 | |||

| (0.919–1.376) | (0.897–1.351) | (1.179–1.793) | (1.164–1.779) | (0.981–1.459) | (0.987–1.474) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.108 | 1.077 | 1.380** | 1.357** | 1.210 | 1.225 | |||

| (0.903–1.360) | (0.873–1.328) | (1.115–1.708) | (1.092–1.686) | (0.990–1.478) | (0.998–1.503) | ||||

| 4th | 1.360** | 1.316* | 1.788*** | 1.754*** | 1.237* | 1.275* | |||

| (1.113–1.661) | (1.068–1.621) | (1.454–2.198) | (1.415–2.173) | (1.016–1.505) | (1.039–1.563) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.891*** | 1.826*** | 2.294*** | 2.272*** | 1.830*** | 1.971*** | |||

| (1.542–2.318) | (1.464–2.278) | (1.861–2.829) | (1.812–2.850) | (1.496–2.239) | (1.585–2.450) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.058 | 1.021 | 1.045 | 0.985 | 1.106 | 1.068 | |||

| (0.863–1.298) | (0.831–1.254) | (0.849–1.286) | (0.799–1.215) | (0.908–1.347) | (0.876–1.302) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.234* | 1.150 | 1.148 | 1.019 | 1.134 | 1.046 | |||

| (1.010–1.508) | (0.937–1.412) | (0.936–1.409) | (0.827–1.256) | (0.931–1.382) | (0.856–1.279) | ||||

| 4th | 1.370** | 1.192 | 1.480*** | 1.215 | 1.166 | 1.009 | |||

| (1.115–1.685) | (0.960–1.479) | (1.200–1.824) | (0.976–1.511) | (0.952–1.430) | (0.817–1.246) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.346** | 1.068 | 1.283* | 0.954 | 1.048 | 0.825 | |||

| (1.082–1.674) | (0.842–1.355) | (1.029–1.600) | (0.751–1.213) | (0.849–1.294) | (0.657–1.037) | ||||

| Constant | 0.607** | 0.626** | 0.592** | 0.381*** | 0.465*** | 0.376*** | 0.760 | 0.793 | 0.719* |

| (0.444–0.830) | (0.462–0.849) | (0.429–0.817) | (0.277–0.524) | (0.340–0.637) | (0.270–0.523) | (0.559–1.034) | (0.586–1.073) | (0.523–0.988) | |

| Observations | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.072 | 0.066 | 0.073 | 0.065 | 0.056 | 0.066 | 0.072 | 0.066 | 0.073 |

Results presented are odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The best health status was defined as those in the two highest quintiles of the index score, while the worst health status was defined as those in the three lower quintiles of the index score. The 1st wealth quintile and equivalent consumption quintile are the reference categories.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Figure 5.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for equivalent consumption and asset index on health status

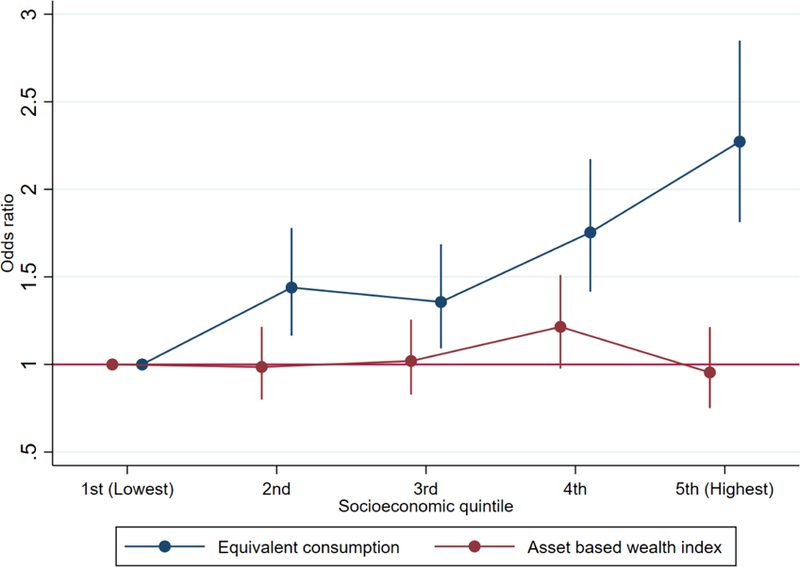

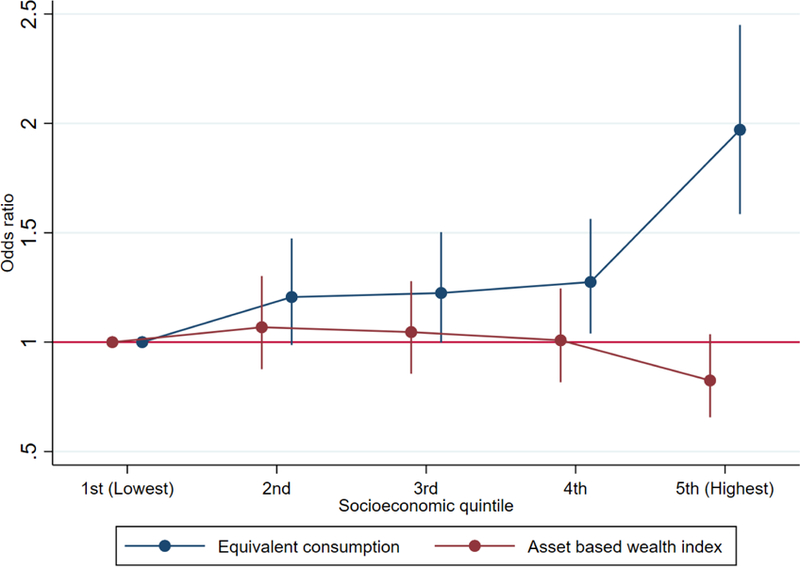

When we turn to disability status, in columns 4 to 6 of Table 4, the results are very similar. We see a steeper gradient in equivalent consumption in column 4 than in the wealth index in column 5, and when we include both measures in column 6 the steep gradient in equivalent consumption remains while the gradient in wealth disappears. As before, an individual in the highest quintile of equivalent consumption is 127.2% more likely to be in good health as defined by the disability status than an individual in the lowest quintile of equivalent consumption. In the case of the wealth asset index, an individual in the highest asset quintile has a lower likelihood of being in good health than someone in the lowest quintile of asset but it is not significant. Figure 6 shows the gradient of disability status with our two socioeconomic indicators based on the results in column 6 of Table 4. The results for PVW health status in columns 7 to 9 show again a steep gradient in equivalent consumption, but in this case, there does not seem to be a relation to the wealth index even when not including equivalent consumption. Similar to the figures above, Figure 7 shows the health gradients for PVW health. Similar to before, being in the highest equivalent consumption quintile is associated with a 97.1% higher likelihood of being in good health compared to individuals in the lowest equivalent consumption quintile. In contrast, the likelihood of being in good health is not significantly higher for those in the highest asset quintile than those in the lowest one. Additionally, Table 4 shows that not only is the gradient steeper when measured by equivalent consumption, but the pseudo r-squared shows that equivalent consumption explains a larger share of the variation when compared to the wealth index.

Figure 6.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for equivalent consumption and asset index on disability status

Figure 7.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for equivalent consumption and asset index on PVW health status

It is important to note that the differences we find in the association between each socioeconomic measure and the three health indicators is due to the fact that each health indicator consists on different indicators of health (Appendix Table 1) and therefore capture different dimensions of health. As a consequence we find that there is a gradient in wealth for Health Status but not for PVW Health Status. However, the relevance of these results is that for each of the health measures we find that the gradients across socioeconomic measures different in a way that gradients for equivalent consumption are considerably larger than those of the wealth asset index.

To verify the robustness of our results we evaluate the models presented in Table 4 by using a linear probability regression (Appendix Table 4), a Probit regression (Appendix Table 5), and a multinomial logistic regression (Appendix Table 6). In all of them we obtain similar findings to the main results. In particular, the multinomial logistic regression shows that the gradient is more pronounced in consumption than in the asset index for being in the top quintile of health. Additionally, we also test the robustness of dichotomization by removing individuals in the third quintile from the sample who could have been categorized as good or bad health. Appendix Table 7 shows that the results remain the same despite this exclusion further confirming the robustness of our results.

Results comparing consumption per capita with the wealth index are reported in Appendix Table 8. The results show a similar pattern of a steeper slope in consumption per capita than the wealth index for each health indicator but the results are less clear than for equivalent consumption and in some cases where we include both measures the middle quintiles of the wealth index seem to have better health than the highest and lowest quintiles. In addition, if we compare equivalent consumption the consumption per capita it is equivalent consumption rather than consumption per capita that seems to drive health differentials as shown in Appendix Table 9. Finally, to verify the robustness of our results with regards to the PCA weights used to construct the health indices we replicate our results using equal weights for the variables in each index. Appendix Figure 1 shows the distribution of the health indices and while it is different from the main figure, the results presented in Appendix Table 10 show that the conclusions do not change. That is, using equal weights across the health variables provide similar results than those obtained in the main results when using PCA estimated weights.

4. Conclusion

The objective of this paper was to evaluate whether the choice of welfare measure makes a difference in the estimation of health gradients for the elderly in South Africa. Using data from an ageing survey in Agincourt, we show that health gradients in three different health indices are much steeper in equivalent consumption compared to the wealth index. Our results finding a shallow gradient in the wealth index are in line with several SAGE studies in recent years [18–25]. However, the contrast in gradients between equivalent consumption and wealth highlight the important of the socioeconomic measure when evaluating inequalities. The results found in this paper contrast some of the previous evidence focusing in younger populations which shows that while the consumption based and wealth index measures rank households very differently, the choice of socioeconomic measure does not affect the estimated health gradient [4, 14, 41]. While many surveys in developing countries collect only asset-based wealth index measures, due to the difficulty of collecting income and consumption data, our results show that it may be value to have such data to get a clearer picture of socioeconomic inequalities in the health of older people.

Overall, our results highlight the importance of choice of socio economic indicator when measuring inequalities in adult health. Policy makers could reach substantially different conclusions regarding health inequalities when using different measures of socioeconomic status. Our results suggest that there are substantial gradients in adult health with equivalent consumption and that policies that reduce consumption inequality have the potential to mitigate these health inequalities.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging at the National Institute of Health (1P01AG041710-01A1, HAALSI – Health and Aging in Africa: Longitudinal Studies of INDEPTH Communities). The Agincourt HDSS was supported by the Welcome Trust, UK (058893/Z/99/A, 069683/Z/02/Z, 085477/Z/08/Z and 085477/B/08/Z), the University of the Witwatersrand and South African Medical Research Council.

Appendix Tables

Appendix Table 1.

Variables included in each of the health indices and their scoring coefficients

| Items | Health Status | Disability Status | PVW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | |||

| No difficulty crossing a room | 0.034 | 0.375 | 0.361 |

| Completed normal walk | 0.382 | 0.259 | 0.251 |

| Completed semi tandem | 0.407 | 0.267 | 0.265 |

| Self-care | |||

| No difficulties dressing | 0.416 | 0.385 | 0.362 |

| No difficulties bathing | 0.422 | 0.397 | 0.374 |

| No difficulties eating | 0.263 | 0.246 | |

| No difficulties getting out of bed | 0.401 | 0.380 | |

| No difficulties using toilet | 0.400 | 0.381 | |

| Health | |||

| Categorical self-reported health (1 Poor-5 Excellent) | 0.188 | ||

| No back problems | 0.021 | ||

| No heart problems | 0.031 | ||

| Never suffered stroke | 0.151 | ||

| Does not suffer from hypertension (measured and reported) | 0.053 | ||

| No respiratory problems | 0.026 | ||

| Does not suffer from diabetes (measured and reported) | 0.079 | ||

| Normal BMI | 0.052 | ||

| Health care use | |||

| No hospital stays in last 12 months | 0.079 | ||

| No doctor visits in last 3 months | 0.066 | ||

| Pain and discomfort | |||

| No reported physical pain yesterday | 0.241 | ||

| Cognition | |||

| No difficulties concentrating | 0.285 | 0.102 | 0.103 |

| No difficulties learning new things | 0.265 | 0.085 | 0.085 |

| Sleep/Energy | |||

| Never had difficulties sleeping in past 4 weeks | 0.177 | ||

| Affect | |||

| Never felt sad or depressed in last two weeks | 0.180 | 0.090 | |

| Vision | |||

| No reported visual difficulties | 0.249 | ||

| Work | |||

| Health does not limit work | 0.121 |

Appendix Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of assets included in the wealth asset index

| Means | SD | Scoring coefficients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household ownership | 0.897 | 0.298 | 0.010 |

| Durables | |||

| Number of cars | 0.317 | 0.766 | 0.236 |

| Number of bicycles | 0.054 | 0.281 | 0.042 |

| Number of refrigerators | 1.116 | 0.630 | 0.240 |

| Number of washing machines | 0.091 | 0.291 | 0.194 |

| Number of sewing machines | 0.074 | 0.315 | 0.099 |

| Number of tube televisions | 0.885 | 0.720 | 0.115 |

| Number of flat screen televisions | 0.117 | 0.375 | 0.188 |

| Number of video recorders | 0.547 | 0.614 | 0.172 |

| Number of satellites for television | 0.203 | 0.406 | 0.254 |

| Number of radios | 0.355 | 1.171 | 0.027 |

| Number of computers | 0.089 | 0.349 | 0.174 |

| Number of regular cellphones | 1.765 | 1.496 | 0.036 |

| Number of smartphones | 1.504 | 1.714 | 0.208 |

| Number of clocks | 0.228 | 0.533 | 0.153 |

| Number of pressure cookers | 0.245 | 0.822 | 0.023 |

| Number of beds | 1.195 | 1.710 | 0.194 |

| Number of cots | 2.960 | 1.791 | 0.227 |

| Number of tables | 1.040 | 0.881 | 0.200 |

| Number of electric fans | 0.725 | 1.005 | 0.243 |

| Number of stoves | 0.886 | 0.581 | 0.190 |

| Livestock | |||

| Number of cows | 1.587 | 5.128 | 0.098 |

| Number of goats | 0.529 | 2.012 | 0.022 |

| Number of chickens | 3.767 | 7.020 | 0.042 |

| Number of pigs | 0.100 | 1.037 | 0.033 |

| Household conditions | |||

| Domestic help | 0.145 | 0.353 | 0.085 |

| Wall material: Brick | 0.052 | 0.215 | 0.042 |

| Wall material: Cement | 0.932 | 0.244 | −0.016 |

| Roof material: Tiles | 0.146 | 0.341 | 0.235 |

| Roof material: Corrugated iron | 0.847 | 0.348 | −0.226 |

| Floor material: Tiles | 0.135 | 0.330 | 0.244 |

| Floor material: Cement | 0.859 | 0.336 | −0.235 |

| Toilet location: Yard | 0.867 | 0.328 | 0.089 |

| Toilet location: Other (Not in house) | 0.078 | 0.259 | −0.124 |

| Toilet type: VIP | 0.085 | 0.270 | −0.003 |

| Toilet type: Pit latrine | 0.791 | 0.393 | 0.072 |

| Toilet type: None | 0.099 | 0.289 | −0.148 |

| Water source: Tap in yard | 0.377 | 0.468 | 0.108 |

| Water source: Tap in street | 0.539 | 0.482 | −0.125 |

| Water source: Truck | 0.067 | 0.242 | 0.023 |

| Cooking fuel: Electricity | 0.393 | 0.471 | 0.155 |

| Cooking fuel: Wood | 0.602 | 0.472 | −0.158 |

Appendix Table 3.

Correlation matrix of SES measures and health indices

| Health status |

Disability Status |

PVW Health Status |

Consumption per capita |

Wealth index |

Equivalent consumption |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | 1 | |||||

| Disability status | 0.722*** | 1 | ||||

| PVW Health status | 0.575*** | 0.546*** | 1 | |||

| Consumption per capita | 0.0688*** | 0.0767*** | 0.0668*** | 1 | ||

| Wealth index | 0.0897*** | 0.0836*** | 0.0379** | 0.286*** | 1 | |

| Equivalent consumption | 0.0887*** | 0.106*** | 0.0880*** | 0.909*** | 0.356*** | 1 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 4.

Linear probability models for the health indices comparing equivalent consumption and the asset-based wealth index

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 0.028 | 0.033* | 0.030* | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.018 |

| (−0.000–0.057) | (0.005–0.062) | (0.002–0.059) | (−0.021–0.035) | (−0.017–0.039) | (−0.020–0.036) | (−0.009–0.048) | (−0.008–0.050) | (−0.011–0.047) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | −0.131*** | −0.135*** | −0.133*** | −0.078*** | −0.082*** | −0.078*** | −0.128*** | −0.128*** | −0.125*** |

| (−0.174--0.089) | (−0.177--0.092) | (−0.175--0.090) | (−0.120--0.036) | (−0.125--0.039) | (−0.121--0.036) | (−0.170--0.087) | (−0.170--0.086) | (−0.167--0.083) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | −0.165*** | −0.164*** | −0.166*** | −0.135*** | −0.132*** | −0.135*** | −0.163*** | −0.155*** | −0.157*** |

| (−0.211--0.118) | (−0.211--0.118) | (−0.213--0.120) | (−0.181--0.089) | (−0.179--0.085) | (−0.182--0.089) | (−0.209--0.116) | (−0.202--0.108) | (−0.204--0.110) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | −0.238*** | −0.239*** | −0.240*** | −0.197*** | −0.194*** | −0.196*** | −0.238*** | −0.233*** | −0.233*** |

| (−0.289--0.188) | (−0.290--0.188) | (−0.291--0.189) | (−0.247--0.147) | (−0.245--0.144) | (−0.247--0.146) | (−0.289--0.187) | (−0.284--0.181) | (−0.284--0.182) | |

| Age group: 80+ | −0.331*** | −0.331*** | −0.333*** | −0.290*** | −0.287*** | −0.290*** | −0.349*** | −0.344*** | −0.347*** |

| (−0.385--0.278) | (−0.385--0.277) | (−0.387--0.279) | (−0.342--0.237) | (−0.339--0.234) | (−0.342--0.238) | (−0.403--0.295) | (−0.399--0.290) | (−0.401--0.292) | |

| Education: Some primary | 0.027 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.037* | 0.042* | 0.036* | 0.024 | 0.031 | 0.027 |

| (−0.007–0.060) | (−0.006–0.061) | (−0.009–0.058) | (0.004–0.070) | (0.008–0.075) | (0.003–0.070) | (−0.010–0.058) | (−0.003–0.065) | (−0.007–0.061) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 0.043 | 0.047 | 0.041 | 0.064* | 0.073** | 0.065* | 0.075** | 0.088*** | 0.081** |

| (−0.009–0.095) | (−0.006–0.099) | (−0.011–0.093) | (0.012–0.115) | (0.021–0.125) | (0.013–0.117) | (0.024–0.126) | (0.036–0.140) | (0.029–0.133) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.044 | 0.024 | −0.006 | 0.026 | 0.006 |

| (−0.049–0.056) | (−0.032–0.075) | (−0.051–0.056) | (−0.032–0.073) | (−0.009–0.097) | (−0.029–0.077) | (−0.059–0.046) | (−0.027–0.080) | (−0.048–0.060) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 0.026 | 0.033 | 0.027 | 0.054 | 0.060 | 0.055 | 0.032 | 0.035 | 0.029 |

| (−0.041–0.094) | (−0.035–0.100) | (−0.041–0.095) | (−0.012–0.120) | (−0.006–0.126) | (−0.011–0.121) | (−0.036–0.100) | (−0.033–0.104) | (−0.039–0.097) | |

| Marital Status: Widowed | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.041 | 0.026 | 0.032 | 0.027 |

| (−0.050–0.081) | (−0.047–0.083) | (−0.052–0.078) | (−0.021–0.105) | (−0.019–0.108) | (−0.022–0.104) | (−0.039–0.091) | (−0.033–0.097) | (−0.038–0.091) | |

| Marital Status: Currently married | 0.089** | 0.088** | 0.085** | 0.095** | 0.097** | 0.094** | 0.077* | 0.086** | 0.082** |

| (0.029–0.149) | (0.028–0.149) | (0.024–0.146) | (0.037–0.154) | (0.037–0.156) | (0.035–0.153) | (0.017–0.137) | (0.026–0.147) | (0.022–0.142) | |

| Working | 0.107*** | 0.116*** | 0.107*** | 0.080*** | 0.090*** | 0.080*** | 0.137*** | 0.148*** | 0.138*** |

| (0.066–0.147) | (0.075–0.157) | (0.066–0.147) | (0.039–0.120) | (0.050–0.131) | (0.040–0.120) | (0.096–0.178) | (0.107–0.188) | (0.097–0.178) | |

| Born in South Africa | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.010 | −0.010 | −0.005 | −0.011 | −0.045** | −0.037* | −0.042* |

| (−0.019–0.044) | (−0.018–0.047) | (−0.022–0.042) | (−0.041–0.021) | (−0.036–0.027) | (−0.042–0.020) | (−0.077--0.013) | (−0.070--0.005) | (−0.074--0.009) | |

| Equivalent consumption quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.073*** | 0.071*** | 0.038 | 0.040 | |||

| (−0.018–0.067) | (−0.022–0.064) | (0.032–0.114) | (0.030–0.113) | (−0.004–0.081) | (−0.002–0.083) | ||||

| 3rd | 0.022 | 0.017 | 0.063** | 0.060** | 0.041 | 0.044* | |||

| (−0.021–0.064) | (−0.027–0.060) | (0.021–0.104) | (0.018–0.102) | (−0.002–0.083) | (0.001–0.087) | ||||

| 4th | 0.066** | 0.060** | 0.117*** | 0.114*** | 0.045* | 0.052* | |||

| (0.023–0.109) | (0.015–0.105) | (0.076–0.159) | (0.071–0.157) | (0.003–0.087) | (0.009–0.096) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 0.142*** | 0.136*** | 0.177*** | 0.176*** | 0.135*** | 0.152*** | |||

| (0.098–0.187) | (0.088–0.185) | (0.133–0.220) | (0.129–0.223) | (0.090–0.179) | (0.104–0.199) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.003 | −0.005 | 0.006 | −0.007 | 0.022 | 0.014 | |||

| (−0.039–0.046) | (−0.047–0.038) | (−0.035–0.048) | (−0.049–0.034) | (−0.021–0.064) | (−0.029–0.056) | ||||

| 3rd | 0.038 | 0.022 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.009 | |||

| (−0.005–0.080) | (−0.021–0.065) | (−0.016–0.067) | (−0.042–0.042) | (−0.016–0.069) | (−0.034–0.052) | ||||

| 4th | 0.063** | 0.032 | 0.081*** | 0.039 | 0.031 | −0.001 | |||

| (0.019–0.108) | (−0.014–0.078) | (0.037–0.125) | (−0.007–0.084) | (−0.014–0.075) | (−0.047–0.044) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 0.058* | 0.006 | 0.049* | −0.015 | 0.009 | −0.044 | |||

| (0.011–0.106) | (−0.045–0.058) | (0.002–0.096) | (−0.065–0.035) | (−0.037–0.055) | (−0.094–0.005) | ||||

| Constant | 0.391*** | 0.401*** | 0.389*** | 0.291*** | 0.329*** | 0.290*** | 0.440*** | 0.449*** | 0.428*** |

| (0.320–0.462) | (0.332–0.470) | (0.317–0.462) | (0.222–0.359) | (0.261–0.398) | (0.220–0.360) | (0.370–0.510) | (0.379–0.518) | (0.356–0.500) | |

| Observations | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 |

Results presented are odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The best health status was defined as those in the two highest quintiles of the index score, while the worst health status was defined as those in the three lower quintiles of the index score.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 5.

Probit coefficients for the health indices comparing equivalent consumption and the asset-based wealth index

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 0.083* | 0.096* | 0.089* | 0.024 | 0.037 | 0.028 | 0.058 | 0.062 | 0.054 |

| (0.005–0.161) | (0.018–0.174) | (0.010–0.167) | (−0.054–0.103) | (−0.042–0.116) | (−0.051–0.107) | (−0.021–0.136) | (−0.016–0.141) | (−0.024–0.133) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | −0.341*** | −0.348*** | −0.345*** | −0.200*** | −0.211*** | −0.202*** | −0.332*** | −0.330*** | −0.324*** |

| (−0.452--0.230) | (−0.459--0.237) | (−0.457--0.234) | (−0.310--0.090) | (−0.321--0.101) | (−0.313--0.092) | (−0.442--0.222) | (−0.439--0.220) | (−0.435--0.214) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | −0.429*** | −0.427*** | −0.435*** | −0.355*** | −0.346*** | −0.358*** | −0.421*** | −0.399*** | −0.408*** |

| (−0.551--0.306) | (−0.550--0.304) | (−0.558--0.311) | (−0.478--0.233) | (−0.469--0.222) | (−0.482--0.234) | (−0.544--0.298) | (−0.523--0.276) | (−0.532--0.284) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | −0.637*** | −0.638*** | −0.643*** | −0.539*** | −0.530*** | −0.540*** | −0.630*** | −0.612*** | −0.618*** |

| (−0.776--0.498) | (−0.777--0.498) | (−0.783--0.503) | (−0.680--0.399) | (−0.671--0.389) | (−0.681--0.399) | (−0.769--0.491) | (−0.752--0.473) | (−0.757--0.478) | |

| Age group: 80+ | −0.975*** | −0.971*** | −0.981*** | −0.905*** | −0.892*** | −0.909*** | −1.023*** | −1.003*** | −1.017*** |

| (−1.146--0.804) | (−1.142--0.800) | (−1.152--0.810) | (−1.080--0.729) | (−1.067--0.718) | (−1.084--0.734) | (−1.196--0.851) | (−1.176--0.831) | (−1.190--0.844) | |

| Education: Some primary | 0.075 | 0.077 | 0.069 | 0.111* | 0.121* | 0.109* | 0.071 | 0.090 | 0.080 |

| (−0.017–0.168) | (−0.017–0.170) | (−0.025–0.162) | (0.017–0.206) | (0.026–0.216) | (0.014–0.204) | (−0.023–0.165) | (−0.005–0.184) | (−0.015–0.175) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 0.115 | 0.122 | 0.108 | 0.179* | 0.199** | 0.181* | 0.204** | 0.236*** | 0.219** |

| (−0.023–0.253) | (−0.018–0.261) | (−0.032–0.247) | (0.040–0.318) | (0.060–0.338) | (0.041–0.321) | (0.066–0.341) | (0.098–0.374) | (0.081–0.358) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 0.008 | 0.055 | 0.003 | 0.059 | 0.120 | 0.067 | −0.013 | 0.076 | 0.020 |

| (−0.133–0.149) | (−0.088–0.198) | (−0.141–0.147) | (−0.082–0.200) | (−0.023–0.262) | (−0.077–0.211) | (−0.155–0.129) | (−0.068–0.220) | (−0.125–0.165) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 0.068 | 0.086 | 0.070 | 0.148 | 0.164 | 0.151 | 0.081 | 0.091 | 0.074 |

| (−0.116–0.251) | (−0.096–0.268) | (−0.113–0.253) | (−0.038–0.334) | (−0.021–0.349) | (−0.035–0.337) | (−0.102–0.265) | (−0.092–0.274) | (−0.110–0.258) | |

| Marital Status: Widowed | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.025 | 0.107 | 0.112 | 0.105 | 0.065 | 0.080 | 0.067 |

| (−0.147–0.209) | (−0.141–0.213) | (−0.154–0.203) | (−0.073–0.288) | (−0.068–0.291) | (−0.076–0.285) | (−0.112–0.242) | (−0.096–0.257) | (−0.110–0.244) | |

| Marital Status: Currently married | 0.239** | 0.235** | 0.227** | 0.261** | 0.263** | 0.258** | 0.205* | 0.230** | 0.219** |

| (0.076–0.402) | (0.073–0.398) | (0.064–0.391) | (0.096–0.425) | (0.098–0.428) | (0.092–0.424) | (0.043–0.366) | (0.067–0.392) | (0.056–0.383) | |

| Working | 0.276*** | 0.298*** | 0.275*** | 0.204*** | 0.231*** | 0.204*** | 0.354*** | 0.381*** | 0.357*** |

| (0.170–0.382) | (0.192–0.404) | (0.169–0.381) | (0.099–0.309) | (0.126–0.336) | (0.099–0.310) | (0.247–0.461) | (0.274–0.487) | (0.250–0.464) | |

| Born in South Africa | 0.033 | 0.039 | 0.026 | −0.036 | −0.022 | −0.040 | −0.129** | −0.108* | −0.119* |

| (−0.058–0.124) | (−0.053–0.131) | (−0.066–0.118) | (−0.128–0.057) | (−0.114–0.071) | (−0.134–0.053) | (−0.220--0.038) | (−0.199--0.016) | (−0.211--0.028) | |

| Equivalent consumption quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.071 | 0.060 | 0.222*** | 0.216*** | 0.107 | 0.113 | |||

| (−0.051–0.192) | (−0.063–0.183) | (0.097–0.346) | (0.090–0.342) | (−0.013–0.227) | (−0.009–0.234) | ||||

| 3rd | 0.058 | 0.043 | 0.190** | 0.180** | 0.111 | 0.120 | |||

| (−0.065–0.182) | (−0.083–0.169) | (0.063–0.317) | (0.051–0.309) | (−0.010–0.232) | (−0.004–0.243) | ||||

| 4th | 0.183** | 0.165* | 0.344*** | 0.333*** | 0.124* | 0.143* | |||

| (0.061–0.305) | (0.039–0.292) | (0.221–0.468) | (0.205–0.461) | (0.005–0.244) | (0.019–0.267) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 0.387*** | 0.368*** | 0.502*** | 0.495*** | 0.367*** | 0.413*** | |||

| (0.263–0.511) | (0.234–0.502) | (0.376–0.628) | (0.359–0.630) | (0.244–0.490) | (0.281–0.545) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.011 | −0.011 | 0.016 | −0.021 | 0.060 | 0.039 | |||

| (−0.112–0.135) | (−0.136–0.113) | (−0.109–0.141) | (−0.147–0.105) | (−0.059–0.180) | (−0.082–0.159) | ||||

| 3rd | 0.107 | 0.065 | 0.075 | 0.005 | 0.072 | 0.024 | |||

| (−0.015–0.230) | (−0.060–0.190) | (−0.048–0.199) | (−0.121–0.130) | (−0.049–0.193) | (−0.099–0.147) | ||||

| 4th | 0.181** | 0.097 | 0.235*** | 0.118 | 0.085 | −0.003 | |||

| (0.056–0.306) | (−0.033–0.228) | (0.109–0.362) | (−0.013–0.250) | (−0.039–0.208) | (−0.131–0.125) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 0.165* | 0.027 | 0.145* | −0.030 | 0.025 | −0.119 | |||

| (0.032–0.298) | (−0.117–0.171) | (0.012–0.279) | (−0.175–0.115) | (−0.103–0.154) | (−0.257–0.020) | ||||

| Constant | −0.299** | −0.274** | −0.305** | −0.586*** | −0.465*** | −0.589*** | −0.165 | −0.140 | −0.197* |

| (−0.491--0.108) | (−0.461--0.087) | (−0.502--0.108) | (−0.780--0.391) | (−0.657--0.274) | (−0.790--0.388) | (−0.354–0.024) | (−0.327–0.046) | (−0.392--0.002) | |

| Observations | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 |

Results presented are Probit coefficients and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The best health status was defined as those in the two highest quintiles of the index score, while the worst health status was defined as those in the three lower quintiles of the index score.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 6.

Multinomial logit odds ratios for the health indices comparing consumption per capita and equivalent consumption

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Panel A) Health quintile 1 (Lowest) | |||||||||

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.235 | 1.230 | 1.097 | 1.113 | 1.231 | 1.264 | |||

| (0.938–1.625) | (0.934–1.620) | (0.827–1.454) | (0.838–1.479) | (0.929–1.632) | (0.952–1.678) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.174 | 1.174 | 1.135 | 1.167 | 1.376* | 1.438* | |||

| (0.894–1.541) | (0.891–1.546) | (0.862–1.494) | (0.883–1.543) | (1.040–1.821) | (1.082–1.912) | ||||

| 4th | 1.241 | 1.248 | 1.162 | 1.212 | 1.635*** | 1.749*** | |||

| (0.937–1.643) | (0.936–1.665) | (0.875–1.541) | (0.904–1.626) | (1.229–2.175) | (1.306–2.343) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.131 | 1.143 | 0.937 | 0.987 | 1.719*** | 1.870*** | |||

| (0.836–1.531) | (0.829–1.574) | (0.693–1.266) | (0.717–1.360) | (1.260–2.346) | (1.348–2.596) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.926 | 0.910 | 0.782 | 0.770 | 0.820 | 0.771 | |||

| (0.702–1.220) | (0.690–1.202) | (0.593–1.032) | (0.582–1.018) | (0.614–1.095) | (0.575–1.033) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.105 | 1.068 | 0.861 | 0.842 | 0.916 | 0.822 | |||

| (0.835–1.464) | (0.802–1.423) | (0.648–1.143) | (0.630–1.126) | (0.684–1.226) | (0.611–1.107) | ||||

| 4th | 0.969 | 0.930 | 0.851 | 0.836 | 0.902 | 0.759 | |||

| (0.723–1.299) | (0.689–1.257) | (0.632–1.146) | (0.614–1.139) | (0.665–1.223) | (0.554–1.040) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.005 | 0.962 | 0.789 | 0.789 | 0.954 | 0.748 | |||

| (0.744–1.358) | (0.700–1.323) | (0.581–1.072) | (0.570–1.092) | (0.696–1.309) | (0.538–1.041) | ||||

| Panel B) Health quintile 2 | |||||||||

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.232 | 1.248 | 0.974 | 0.976 | 1.206 | 1.225 | |||

| (0.944–1.608) | (0.956–1.630) | (0.754–1.258) | (0.755–1.262) | (0.918–1.584) | (0.931–1.614) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.089 | 1.107 | 0.890 | 0.896 | 1.245 | 1.276 | |||

| (0.830–1.429) | (0.841–1.455) | (0.687–1.154) | (0.689–1.166) | (0.942–1.644) | (0.960–1.695) | ||||

| 4th | 1.178 | 1.204 | 0.898 | 0.906 | 1.538** | 1.594** | |||

| (0.894–1.552) | (0.909–1.594) | (0.689–1.171) | (0.689–1.191) | (1.163–2.034) | (1.195–2.128) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 0.962 | 1.004 | 0.551*** | 0.555*** | 1.494** | 1.566** | |||

| (0.713–1.298) | (0.734–1.373) | (0.415–0.732) | (0.412–0.750) | (1.107–2.017) | (1.135–2.161) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.004 | 0.997 | 0.846 | 0.863 | 0.916 | 0.875 | |||

| (0.767–1.314) | (0.760–1.306) | (0.649–1.102) | (0.661–1.127) | (0.685–1.223) | (0.653–1.171) | ||||

| 3rd | 0.910 | 0.891 | 0.878 | 0.924 | 0.942 | 0.867 | |||

| (0.685–1.208) | (0.669–1.186) | (0.670–1.151) | (0.702–1.216) | (0.701–1.265) | (0.642–1.172) | ||||

| 4th | 1.028 | 1.014 | 0.874 | 0.970 | 1.017 | 0.891 | |||

| (0.771–1.372) | (0.756–1.360) | (0.660–1.158) | (0.727–1.296) | (0.753–1.372) | (0.655–1.212) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 0.865 | 0.866 | 0.746* | 0.906 | 1.005 | 0.837 | |||

| (0.638–1.173) | (0.630–1.190) | (0.558–0.998) | (0.666–1.233) | (0.738–1.367) | (0.603–1.163) | ||||

| Panel C) Health quintile 4 | |||||||||

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.142 | 1.123 | 1.342 | 1.325 | 1.261 | 1.268 | |||

| (0.867–1.504) | (0.851–1.482) | (0.998–1.804) | (0.982–1.787) | (0.963–1.650) | (0.966–1.664) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.000 | 0.984 | 1.047 | 1.033 | 1.420* | 1.432* | |||

| (0.757–1.321) | (0.741–1.306) | (0.770–1.424) | (0.756–1.412) | (1.081–1.865) | (1.083–1.892) | ||||

| 4th | 1.122 | 1.103 | 1.375* | 1.353 | 1.363* | 1.401* | |||

| (0.844–1.491) | (0.822–1.481) | (1.016–1.861) | (0.985–1.858) | (1.029–1.806) | (1.049–1.873) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.265 | 1.231 | 1.300 | 1.272 | 1.977*** | 2.128*** | |||

| (0.946–1.692) | (0.896–1.690) | (0.957–1.765) | (0.911–1.776) | (1.484–2.635) | (1.560–2.903) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.007 | 1.000 | 0.808 | 0.792 | 1.172 | 1.118 | |||

| (0.757–1.340) | (0.750–1.332) | (0.592–1.103) | (0.579–1.082) | (0.881–1.559) | (0.840–1.489) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.211 | 1.185 | 0.998 | 0.956 | 1.220 | 1.103 | |||

| (0.904–1.621) | (0.881–1.595) | (0.733–1.358) | (0.698–1.310) | (0.911–1.635) | (0.819–1.485) | ||||

| 4th | 1.012 | 0.974 | 1.181 | 1.109 | 1.243 | 1.049 | |||

| (0.750–1.365) | (0.714–1.328) | (0.863–1.615) | (0.798–1.541) | (0.923–1.673) | (0.771–1.427) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.194 | 1.114 | 0.989 | 0.910 | 1.107 | 0.850 | |||

| (0.877–1.627) | (0.796–1.558) | (0.715–1.368) | (0.639–1.297) | (0.816–1.502) | (0.612–1.179) | ||||

| Panel D) Health quintile 5 (Highest) | |||||||||

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.553** | 1.530** | 1.642** | 1.646** | 1.488* | 1.555** | |||

| (1.132–2.130) | (1.110–2.107) | (1.194–2.258) | (1.193–2.272) | (1.099–2.015) | (1.145–2.113) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.560** | 1.518* | 1.772*** | 1.772*** | 1.431* | 1.541** | |||

| (1.137–2.141) | (1.099–2.096) | (1.290–2.434) | (1.281–2.450) | (1.046–1.959) | (1.118–2.125) | ||||

| 4th | 2.298*** | 2.235*** | 2.307*** | 2.320*** | 2.108*** | 2.368*** | |||

| (1.693–3.119) | (1.627–3.071) | (1.690–3.149) | (1.679–3.206) | (1.554–2.861) | (1.723–3.254) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 3.167*** | 3.171*** | 2.493*** | 2.582*** | 3.188*** | 3.812*** | |||

| (2.330–4.304) | (2.274–4.421) | (1.832–3.393) | (1.852–3.599) | (2.333–4.356) | (2.720–5.344) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.106 | 1.015 | 1.058 | 0.971 | 0.868 | 0.786 | |||

| (0.812–1.506) | (0.742–1.387) | (0.783–1.429) | (0.714–1.319) | (0.640–1.177) | (0.577–1.070) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.265 | 1.068 | 1.110 | 0.946 | 0.938 | 0.772 | |||

| (0.931–1.720) | (0.780–1.462) | (0.818–1.508) | (0.692–1.293) | (0.692–1.271) | (0.566–1.054) | ||||

| 4th | 1.823*** | 1.359 | 1.501** | 1.164 | 1.004 | 0.714* | |||

| (1.344–2.474) | (0.986–1.874) | (1.103–2.042) | (0.842–1.608) | (0.733–1.375) | (0.513–0.994) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.401* | 0.904 | 1.172 | 0.831 | 0.949 | 0.568** | |||

| (1.019–1.926) | (0.639–1.280) | (0.850–1.617) | (0.587–1.178) | (0.689–1.306) | (0.402–0.804) | ||||

Results presented are odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The health reference category is the third quintile. The models control for age group, gender, education, marital status, occupation, and country of origin.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 7.

Logistic regression odds ratios for the health indices comparing equivalent consumption and the asset-based wealth index excluding the third health quintile

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 1.094 | 1.120 | 1.106 | 1.008 | 1.040 | 1.014 | 1.149 | 1.162* | 1.148 |

| (0.947–1.263) | (0.970–1.292) | (0.958–1.278) | (0.872–1.166) | (0.900–1.202) | (0.876–1.174) | (0.993–1.331) | (1.003–1.345) | (0.991–1.331) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | 0.577*** | 0.572*** | 0.572*** | 0.646*** | 0.630*** | 0.643*** | 0.530*** | 0.536*** | 0.535*** |

| (0.468–0.713) | (0.464–0.706) | (0.463–0.706) | (0.526–0.794) | (0.513–0.773) | (0.523–0.790) | (0.428–0.657) | (0.432–0.663) | (0.432–0.664) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | 0.486*** | 0.482*** | 0.477*** | 0.501*** | 0.506*** | 0.498*** | 0.450*** | 0.464*** | 0.456*** |

| (0.387–0.610) | (0.384–0.605) | (0.380–0.601) | (0.399–0.629) | (0.403–0.635) | (0.396–0.626) | (0.356–0.568) | (0.367–0.586) | (0.360–0.577) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | 0.320*** | 0.316*** | 0.314*** | 0.358*** | 0.358*** | 0.356*** | 0.288*** | 0.294*** | 0.291*** |

| (0.247–0.413) | (0.245–0.409) | (0.242–0.406) | (0.276–0.464) | (0.277–0.464) | (0.274–0.462) | (0.222–0.374) | (0.227–0.382) | (0.224–0.379) | |

| Age group: 80+ | 0.156*** | 0.156*** | 0.154*** | 0.158*** | 0.161*** | 0.157*** | 0.125*** | 0.127*** | 0.125*** |

| (0.114–0.214) | (0.114–0.214) | (0.112–0.211) | (0.114–0.220) | (0.116–0.224) | (0.113–0.218) | (0.091–0.172) | (0.092–0.176) | (0.091–0.173) | |

| Education: Some primary | 1.133 | 1.121 | 1.117 | 1.211* | 1.220* | 1.207* | 1.222* | 1.245* | 1.234* |

| (0.959–1.340) | (0.947–1.326) | (0.943–1.322) | (1.021–1.437) | (1.029–1.448) | (1.016–1.433) | (1.031–1.448) | (1.049–1.476) | (1.040–1.465) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 1.292 | 1.299* | 1.266 | 1.311* | 1.341* | 1.309* | 1.461** | 1.529** | 1.491** |

| (0.999–1.671) | (1.004–1.680) | (0.977–1.641) | (1.018–1.690) | (1.041–1.729) | (1.013–1.692) | (1.131–1.887) | (1.183–1.977) | (1.151–1.931) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 1.200 | 1.274 | 1.179 | 0.957 | 1.055 | 0.965 | 1.139 | 1.286 | 1.192 |

| (0.920–1.566) | (0.974–1.667) | (0.899–1.546) | (0.738–1.241) | (0.812–1.370) | (0.741–1.258) | (0.872–1.489) | (0.980–1.688) | (0.907–1.567) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 1.148 | 1.189 | 1.156 | 1.335 | 1.370 | 1.352 | 1.320 | 1.348 | 1.312 |

| (0.822–1.603) | (0.854–1.656) | (0.827–1.616) | (0.949–1.879) | (0.977–1.921) | (0.960–1.904) | (0.942–1.850) | (0.963–1.888) | (0.936–1.840) | |

| Marital Status: Widowed | 1.074 | 1.081 | 1.060 | 1.205 | 1.214 | 1.201 | 1.283 | 1.311 | 1.279 |

| (0.777–1.486) | (0.784–1.490) | (0.765–1.468) | (0.864–1.681) | (0.873–1.687) | (0.860–1.678) | (0.925–1.779) | (0.947–1.815) | (0.921–1.776) | |

| Marital Status: Currently married | 1.578** | 1.557** | 1.535** | 1.650** | 1.640** | 1.642** | 1.680*** | 1.731*** | 1.698*** |

| (1.172–2.123) | (1.158–2.092) | (1.137–2.072) | (1.218–2.236) | (1.211–2.219) | (1.208–2.232) | (1.248–2.260) | (1.285–2.330) | (1.258–2.292) | |

| Working | 1.655*** | 1.712*** | 1.653*** | 1.766*** | 1.876*** | 1.768*** | 2.124*** | 2.189*** | 2.137*** |

| (1.351–2.027) | (1.398–2.097) | (1.349–2.025) | (1.442–2.162) | (1.533–2.296) | (1.443–2.167) | (1.720–2.622) | (1.773–2.703) | (1.730–2.639) | |

| Born in South Africa | 1.044 | 1.048 | 1.026 | 0.937 | 0.967 | 0.927 | 0.825* | 0.837* | 0.828* |

| (0.885–1.232) | (0.888–1.237) | (0.869–1.212) | (0.791–1.110) | (0.817–1.144) | (0.782–1.099) | (0.700–0.972) | (0.709–0.988) | (0.701–0.978) | |

| Equivalent consumption quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.066 | 1.042 | 1.426** | 1.408** | 1.119 | 1.116 | |||

| (0.854–1.331) | (0.833–1.304) | (1.136–1.788) | (1.119–1.770) | (0.894–1.400) | (0.889–1.399) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.059 | 1.024 | 1.397** | 1.366** | 1.121 | 1.118 | |||

| (0.844–1.328) | (0.813–1.289) | (1.108–1.760) | (1.079–1.730) | (0.896–1.402) | (0.890–1.405) | ||||

| 4th | 1.239 | 1.189 | 1.772*** | 1.728*** | 1.041 | 1.046 | |||

| (0.991–1.548) | (0.944–1.498) | (1.416–2.216) | (1.367–2.185) | (0.836–1.297) | (0.834–1.312) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.854*** | 1.765*** | 2.582*** | 2.532*** | 1.583*** | 1.661*** | |||

| (1.473–2.334) | (1.380–2.259) | (2.047–3.259) | (1.969–3.257) | (1.261–1.988) | (1.302–2.120) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | 1.140 | ||||||||

| 2nd | 1.086 | 1.057 | 1.094 | 1.027 | 1.159 | (0.912–1.425) | |||

| (0.868–1.358) | (0.843–1.324) | (0.874–1.369) | (0.819–1.287) | (0.928–1.448) | 1.118 | ||||

| 3rd | 1.264* | 1.186 | 1.216 | 1.066 | 1.175 | (0.894–1.398) | |||

| (1.014–1.576) | (0.947–1.486) | (0.974–1.519) | (0.850–1.337) | (0.943–1.463) | 1.123 | ||||

| 4th | 1.390** | 1.232 | 1.559*** | 1.251 | 1.225 | (0.889–1.420) | |||

| (1.106–1.747) | (0.972–1.562) | (1.241–1.958) | (0.986–1.588) | (0.976–1.537) | 0.886 | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.402** | 1.125 | 1.388** | 0.992 | 1.048 | (0.686–1.143) | |||

| (1.100–1.786) | (0.865–1.463) | (1.091–1.765) | (0.762–1.290) | 1.156 | (0.827–1.330) | 1.065 | |||

| Constant | 1.002 | 0.979 | 0.964 | 0.622** | 0.737 | 0.600** | (0.814–1.643) | 1.104 | (0.741–1.532) |

| (0.705–1.422) | (0.695–1.379) | (0.672–1.384) | (0.434–0.891) | (0.520–1.045) | (0.415–0.869) | 1.119 | (0.783–1.555) | 1.116 | |

| Observations | 3973 | 3973 | 3973 | 3937 | 3937 | 3937 | 3973 | 3973 | 3973 |

Results presented are odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The best health status was defined as those in the two highest quintiles of the index score, while the worst health status was defined as those in the three lower quintiles of the index score. The 1st wealth quintile and equivalent consumption quintile are the reference categories.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 8.

Logistic regression odds ratios for the health indices comparing consumption per capita and the asset-based wealth index

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 1.122 | 1.171* | 1.143* | 1.015 | 1.061 | 1.031 | 1.076 | 1.105 | 1.076 |

| (0.988–1.273) | (1.031–1.331) | (1.006–1.299) | (0.893–1.154) | (0.932–1.207) | (0.906–1.174) | (0.947–1.223) | (0.972–1.256) | (0.946–1.224) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | 0.580*** | 0.571*** | 0.572*** | 0.729*** | 0.712*** | 0.719*** | 0.588*** | 0.588*** | 0.591*** |

| (0.485–0.694) | (0.477–0.683) | (0.477–0.685) | (0.611–0.870) | (0.596–0.850) | (0.602–0.860) | (0.492–0.702) | (0.493–0.703) | (0.495–0.707) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | 0.508*** | 0.502*** | 0.494*** | 0.571*** | 0.572*** | 0.558*** | 0.513*** | 0.526*** | 0.518*** |

| (0.417–0.619) | (0.411–0.613) | (0.404–0.603) | (0.468–0.697) | (0.468–0.699) | (0.456–0.682) | (0.420–0.626) | (0.431–0.642) | (0.424–0.632) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | 0.355*** | 0.355*** | 0.345*** | 0.411*** | 0.420*** | 0.403*** | 0.358*** | 0.370*** | 0.360*** |

| (0.283–0.446) | (0.282–0.446) | (0.275–0.435) | (0.326–0.518) | (0.333–0.530) | (0.320–0.509) | (0.285–0.449) | (0.295–0.465) | (0.286–0.452) | |

| Age group: 80+ | 0.195*** | 0.199*** | 0.191*** | 0.213*** | 0.223*** | 0.209*** | 0.180*** | 0.189*** | 0.181*** |

| (0.145–0.262) | (0.148–0.267) | (0.142–0.257) | (0.156–0.290) | (0.164–0.302) | (0.154–0.285) | (0.134–0.243) | (0.140–0.254) | (0.134–0.243) | |

| Education: Some primary | 1.153 | 1.131 | 1.124 | 1.218* | 1.218* | 1.194* | 1.139 | 1.153 | 1.142 |

| (0.991–1.342) | (0.970–1.318) | (0.964–1.310) | (1.042–1.424) | (1.042–1.425) | (1.020–1.397) | (0.976–1.329) | (0.987–1.347) | (0.977–1.335) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 1.225 | 1.214 | 1.182 | 1.347** | 1.379** | 1.319* | 1.414** | 1.466*** | 1.427** |

| (0.979–1.532) | (0.968–1.522) | (0.943–1.482) | (1.076–1.688) | (1.099–1.729) | (1.050–1.657) | (1.132–1.765) | (1.172–1.833) | (1.140–1.787) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 1.053 | 1.088 | 1.008 | 1.135 | 1.211 | 1.107 | 1.013 | 1.128 | 1.045 |

| (0.838–1.325) | (0.862–1.374) | (0.798–1.275) | (0.902–1.428) | (0.960–1.529) | (0.875–1.401) | (0.804–1.276) | (0.892–1.426) | (0.825–1.323) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 1.120 | 1.154 | 1.135 | 1.262 | 1.305 | 1.280 | 1.151 | 1.166 | 1.147 |

| (0.832–1.507) | (0.858–1.553) | (0.842–1.529) | (0.933–1.708) | (0.964–1.767) | (0.945–1.734) | (0.854–1.552) | (0.864–1.571) | (0.850–1.547) | |

| Marital Status: Widowed | 1.087 | 1.057 | 1.066 | 1.234 | 1.191 | 1.216 | 1.150 | 1.134 | 1.148 |

| (0.813–1.454) | (0.791–1.412) | (0.796–1.426) | (0.919–1.657) | (0.886–1.601) | (0.904–1.634) | (0.862–1.534) | (0.849–1.514) | (0.860–1.534) | |

| Marital Status: Currently married | 1.597*** | 1.463** | 1.524** | 1.675*** | 1.528** | 1.621*** | 1.513** | 1.453** | 1.528** |

| (1.227–2.078) | (1.124–1.906) | (1.167–1.990) | (1.282–2.189) | (1.166–2.002) | (1.236–2.126) | (1.165–1.966) | (1.116–1.893) | (1.172–1.993) | |

| Working | 1.579*** | 1.617*** | 1.572*** | 1.405*** | 1.450*** | 1.401*** | 1.789*** | 1.846*** | 1.794*** |

| (1.330–1.875) | (1.363–1.919) | (1.324–1.867) | (1.187–1.664) | (1.224–1.717) | (1.182–1.659) | (1.506–2.126) | (1.554–2.192) | (1.510–2.132) | |

| Born in South Africa | 1.064 | 1.065 | 1.033 | 0.957 | 0.971 | 0.932 | 0.806** | 0.838* | 0.807** |

| (0.914–1.238) | (0.915–1.240) | (0.886–1.204) | (0.820–1.117) | (0.832–1.132) | (0.798–1.089) | (0.694–0.936) | (0.721–0.973) | (0.694–0.939) | |

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.884 | 0.868 | 1.178 | 1.161 | 0.977 | 0.977 | |||

| (0.724–1.080) | (0.711–1.061) | (0.958–1.449) | (0.943–1.427) | (0.804–1.189) | (0.803–1.189) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.171 | 1.138 | 1.519*** | 1.481*** | 1.133 | 1.139 | |||

| (0.962–1.426) | (0.933–1.389) | (1.240–1.861) | (1.207–1.818) | (0.932–1.377) | (0.935–1.387) | ||||

| 4th | 1.124 | 1.089 | 1.479*** | 1.441*** | 1.249* | 1.259* | |||

| (0.919–1.374) | (0.888–1.335) | (1.205–1.814) | (1.172–1.773) | (1.028–1.517) | (1.033–1.534) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.525*** | 1.456*** | 1.885*** | 1.820*** | 1.523*** | 1.564*** | |||

| (1.247–1.865) | (1.183–1.793) | (1.534–2.316) | (1.471–2.252) | (1.246–1.861) | (1.272–1.924) | ||||

| Wealth index quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.058 | 1.050 | 1.045 | 1.028 | 1.106 | 1.092 | |||

| (0.863–1.298) | (0.856–1.288) | (0.849–1.286) | (0.835–1.265) | (0.908–1.347) | (0.897–1.330) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.234* | 1.214 | 1.148 | 1.104 | 1.134 | 1.105 | |||

| (1.010–1.508) | (0.993–1.484) | (0.936–1.409) | (0.900–1.355) | (0.931–1.382) | (0.907–1.347) | ||||

| 4th | 1.370** | 1.303* | 1.480*** | 1.364** | 1.166 | 1.098 | |||

| (1.115–1.685) | (1.058–1.606) | (1.200–1.824) | (1.104–1.686) | (0.952–1.430) | (0.894–1.348) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.346** | 1.216 | 1.283* | 1.113 | 1.048 | 0.932 | |||

| (1.082–1.674) | (0.970–1.525) | (1.029–1.600) | (0.885–1.399) | (0.849–1.294) | (0.749–1.159) | ||||

| Constant | 0.646** | 0.626** | 0.619** | 0.397*** | 0.465*** | 0.383*** | 0.790 | 0.793 | 0.740 |

| (0.474–0.881) | (0.462–0.849) | (0.448–0.855) | (0.289–0.545) | (0.340–0.637) | (0.276–0.533) | (0.580–1.076) | (0.586–1.073) | (0.537–1.019) | |

| Observations | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 |

Results presented are odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The best health status was defined as those in the two highest quintiles of the index score, while the worst health status was defined as those in the three lower quintiles of the index score.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 9.

Logistic regression odds ratios for the health indices comparing consumption per capita and equivalent consumption

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 1.122 | 1.146* | 1.162* | 1.015 | 1.041 | 1.052 | 1.076 | 1.097 | 1.097 |

| (0.988–1.273) | (1.009–1.302) | (1.022–1.322) | (0.893–1.154) | (0.915–1.184) | (0.923–1.197) | (0.947–1.223) | (0.965–1.248) | (0.964–1.248) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | 0.580*** | 0.577*** | 0.574*** | 0.729*** | 0.724*** | 0.721*** | 0.588*** | 0.585*** | 0.584*** |

| (0.485–0.694) | (0.482–0.690) | (0.479–0.687) | (0.611–0.870) | (0.606–0.864) | (0.604–0.861) | (0.492–0.702) | (0.489–0.699) | (0.489–0.698) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | 0.508*** | 0.500*** | 0.496*** | 0.571*** | 0.560*** | 0.558*** | 0.513*** | 0.507*** | 0.505*** |

| (0.417–0.619) | (0.409–0.610) | (0.407–0.606) | (0.468–0.697) | (0.459–0.684) | (0.457–0.681) | (0.420–0.626) | (0.415–0.618) | (0.414–0.617) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | 0.355*** | 0.355*** | 0.357*** | 0.411*** | 0.412*** | 0.413*** | 0.358*** | 0.359*** | 0.359*** |

| (0.283–0.446) | (0.282–0.446) | (0.284–0.448) | (0.326–0.518) | (0.327–0.520) | (0.328–0.521) | (0.285–0.449) | (0.286–0.451) | (0.286–0.451) | |

| Age group: 80+ | 0.195*** | 0.197*** | 0.199*** | 0.213*** | 0.217*** | 0.218*** | 0.180*** | 0.183*** | 0.183*** |

| (0.145–0.262) | (0.147–0.264) | (0.148–0.268) | (0.156–0.290) | (0.159–0.295) | (0.160–0.296) | (0.134–0.243) | (0.136–0.246) | (0.136–0.246) | |

| Education: Some primary | 1.153 | 1.131 | 1.132 | 1.218* | 1.200* | 1.196* | 1.139 | 1.121 | 1.124 |

| (0.991–1.342) | (0.972–1.317) | (0.971–1.318) | (1.042–1.424) | (1.027–1.404) | (1.023–1.399) | (0.976–1.329) | (0.960–1.308) | (0.963–1.313) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 1.225 | 1.203 | 1.199 | 1.347** | 1.332* | 1.324* | 1.414** | 1.392** | 1.392** |

| (0.979–1.532) | (0.961–1.505) | (0.958–1.501) | (1.076–1.688) | (1.063–1.670) | (1.056–1.660) | (1.132–1.765) | (1.114–1.738) | (1.114–1.739) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 1.053 | 1.012 | 1.004 | 1.135 | 1.097 | 1.090 | 1.013 | 0.977 | 0.975 |

| (0.838–1.325) | (0.804–1.274) | (0.798–1.264) | (0.902–1.428) | (0.870–1.382) | (0.865–1.373) | (0.804–1.276) | (0.775–1.231) | (0.774–1.230) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 1.120 | 1.124 | 1.129 | 1.262 | 1.273 | 1.274 | 1.151 | 1.148 | 1.148 |

| (0.832–1.507) | (0.833–1.516) | (0.835–1.526) | (0.933–1.708) | (0.939–1.727) | (0.939–1.730) | (0.854–1.552) | (0.850–1.550) | (0.851–1.550) | |

| Marital Status: Widowed | 1.087 | 1.052 | 1.028 | 1.234 | 1.185 | 1.171 | 1.150 | 1.109 | 1.105 |

| (0.813–1.454) | (0.785–1.409) | (0.765–1.380) | (0.919–1.657) | (0.880–1.595) | (0.868–1.578) | (0.862–1.534) | (0.830–1.483) | (0.826–1.478) | |

| Marital Status: Currently married | 1.597*** | 1.481** | 1.404* | 1.675*** | 1.528** | 1.477** | 1.513** | 1.400* | 1.391* |

| (1.227–2.078) | (1.136–1.931) | (1.071–1.841) | (1.282–2.189) | (1.167–1.999) | (1.123–1.941) | (1.165–1.966) | (1.075–1.822) | (1.065–1.819) | |

| Working | 1.579*** | 1.560*** | 1.560*** | 1.405*** | 1.388*** | 1.387*** | 1.789*** | 1.772*** | 1.773*** |

| (1.330–1.875) | (1.314–1.852) | (1.314–1.853) | (1.187–1.664) | (1.172–1.644) | (1.171–1.643) | (1.506–2.126) | (1.491–2.106) | (1.492–2.109) | |

| Born in South Africa | 1.064 | 1.059 | 1.066 | 0.957 | 0.950 | 0.957 | 0.806** | 0.809** | 0.808** |

| (0.914–1.238) | (0.910–1.232) | (0.915–1.242) | (0.820–1.117) | (0.814–1.108) | (0.820–1.118) | (0.694–0.936) | (0.697–0.940) | (0.696–0.939) | |

| Consumption per capita quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 0.884 | 0.723* | 1.178 | 0.921 | 0.977 | 0.831 | |||

| (0.724–1.080) | (0.564–0.926) | (0.958–1.449) | (0.714–1.187) | (0.804–1.189) | (0.651–1.060) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.171 | 0.836 | 1.519*** | 1.047 | 1.133 | 0.929 | |||

| (0.962–1.426) | (0.629–1.111) | (1.240–1.861) | (0.782–1.401) | (0.932–1.377) | (0.701–1.232) | ||||

| 4th | 1.124 | 0.637** | 1.479*** | 0.810 | 1.249* | 0.911 | |||

| (0.919–1.374) | (0.460–0.884) | (1.205–1.814) | (0.581–1.130) | (1.028–1.517) | (0.662–1.253) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.525*** | 0.653* | 1.885*** | 0.804 | 1.523*** | 0.899 | |||

| (1.247–1.865) | (0.446–0.955) | (1.534–2.316) | (0.546–1.185) | (1.246–1.861) | (0.617–1.308) | ||||

| Equivalent consumption quintiles | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.124 | 1.338* | 1.454*** | 1.517** | 1.196 | 1.298* | |||

| (0.919–1.376) | (1.050–1.707) | (1.179–1.793) | (1.183–1.945) | (0.981–1.459) | (1.021–1.649) | ||||

| 3rd | 1.108 | 1.392* | 1.380** | 1.440* | 1.210 | 1.316 | |||

| (0.903–1.360) | (1.042–1.859) | (1.115–1.708) | (1.069–1.942) | (0.990–1.478) | (0.990–1.749) | ||||

| 4th | 1.360** | 1.824*** | 1.788*** | 1.995*** | 1.237* | 1.315 | |||

| (1.113–1.661) | (1.322–2.515) | (1.454–2.198) | (1.437–2.769) | (1.016–1.505) | (0.958–1.806) | ||||

| 5th (Highest) | 1.891*** | 2.759*** | 2.294*** | 2.821*** | 1.830*** | 1.969*** | |||

| (1.542–2.318) | (1.879–4.052) | (1.861–2.829) | (1.909–4.167) | (1.496–2.239) | (1.352–2.868) | ||||

| Constant | 0.646** | 0.607** | 0.657** | 0.397*** | 0.381*** | 0.390*** | 0.790 | 0.760 | 0.788 |

| (0.474–0.881) | (0.444–0.830) | (0.478–0.904) | (0.289–0.545) | (0.277–0.524) | (0.282–0.540) | (0.580–1.076) | (0.559–1.034) | (0.576–1.078) | |

| Observations | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 | 5025 |

Results presented are odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis with standard errors clustered at household level. The best health status was defined as those in the two highest quintiles of the index score, while the worst health status was defined as those in the three lower quintiles of the index score.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix Table 10.

Logistic regression odds ratios for the health indices with equal weighting

| Health Status | Disability Status | PVW Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Male | 1.224** | 1.252*** | 1.239** | 1.075 | 1.098 | 1.085 | 1.145* | 1.153* | 1.138 |

| (1.077–1.390) | (1.102–1.422) | (1.090–1.408) | (0.943–1.225) | (0.963–1.252) | (0.951–1.237) | (1.007–1.301) | (1.014–1.311) | (1.000–1.294) | |

| Age group: 50–59 | 0.567*** | 0.562*** | 0.563*** | 0.673*** | 0.659*** | 0.668*** | 0.556*** | 0.560*** | 0.563*** |

| (0.474–0.678) | (0.470–0.672) | (0.470–0.674) | (0.563–0.805) | (0.551–0.789) | (0.558–0.799) | (0.465–0.665) | (0.469–0.669) | (0.471–0.674) | |

| Age group: 60–69 | 0.495*** | 0.495*** | 0.489*** | 0.524*** | 0.532*** | 0.519*** | 0.485*** | 0.506*** | 0.497*** |

| (0.406–0.604) | (0.405–0.604) | (0.400–0.598) | (0.428–0.643) | (0.434–0.653) | (0.422–0.637) | (0.397–0.593) | (0.414–0.618) | (0.406–0.608) | |

| Age group: 70–79 | 0.330*** | 0.328*** | 0.325*** | 0.377*** | 0.382*** | 0.374*** | 0.351*** | 0.363*** | 0.359*** |

| (0.262–0.417) | (0.260–0.415) | (0.257–0.411) | (0.298–0.478) | (0.301–0.485) | (0.294–0.475) | (0.280–0.441) | (0.290–0.456) | (0.285–0.451) | |

| Age group: 80+ | 0.183*** | 0.184*** | 0.181*** | 0.233*** | 0.238*** | 0.230*** | 0.186*** | 0.193*** | 0.188*** |

| (0.136–0.247) | (0.137–0.248) | (0.134–0.244) | (0.172–0.315) | (0.176–0.322) | (0.170–0.312) | (0.139–0.249) | (0.144–0.258) | (0.140–0.252) | |

| Education: Some primary | 1.022 | 1.016 | 1.007 | 1.181* | 1.196* | 1.170 | 1.118 | 1.153 | 1.135 |

| (0.877–1.191) | (0.871–1.185) | (0.863–1.176) | (1.007–1.386) | (1.019–1.404) | (0.996–1.375) | (0.957–1.306) | (0.987–1.348) | (0.971–1.328) | |

| Education: Some secondary | 1.221 | 1.222 | 1.199 | 1.278* | 1.316* | 1.272* | 1.416** | 1.497*** | 1.458** |

| (0.977–1.526) | (0.976–1.530) | (0.957–1.501) | (1.016–1.607) | (1.045–1.658) | (1.009–1.604) | (1.132–1.770) | (1.196–1.873) | (1.163–1.828) | |

| Education: Secondary or more | 1.071 | 1.140 | 1.058 | 1.112 | 1.213 | 1.113 | 0.984 | 1.148 | 1.044 |

| (0.853–1.343) | (0.907–1.433) | (0.839–1.334) | (0.879–1.406) | (0.958–1.536) | (0.877–1.414) | (0.781–1.239) | (0.908–1.450) | (0.825–1.322) | |

| Marital status: Separated / divorced | 1.011 | 1.039 | 1.018 | 1.399* | 1.437* | 1.411* | 1.204 | 1.222 | 1.190 |