Abstract

Objectives

The lower limb is widely reported as the most commonly injured body part in the field of hockey, more specifically lateral ankle sprains and internal knee injury. Despite this, there remains limited understanding of how the biomechanics of the sport could be adapted to minimise injury. The aim of this study was to propose a foot position during the hockey hit that results in the smallest joint angles and moments, from a total of four different foot positions: 0°, 30°, 60° and 90°, which may correlate to injury risk.

Method

Eighteen players from the local University Ladies Hockey Club participated in this study. Each player was required to perform a hit with their lead foot in four different positions: 0°, 30°, 60° and 90°, where 0° was a lead foot position perpendicular to the direction of motion of the ball. Angles and moments were calculated with the Vicon system using force plates and motion analysis.

Results

Significant differences (p<0.05) were found between the angles and moments of the four foot positions tested, indicating that foot angle can influence the degree of angulation, and moments, produced in the lower limb joints during the hockey hit.

Conclusion

There is a relationship between lead foot position and the angles and moments produced in the lower limb joints during the hockey hit, and this may correlate with injury risk.

Keywords: hockey, biomechanics, ankle, knee, injury

What are the new findings?

Lead foot position influences the angles and moments produced in the lower limb joints during the hockey hit.

Overall, a lead foot position in line with the rest of the body whilst performing the hockey hit, defined as 30° in the present study, produced the lowest angles and moments in the most significant planes of motion.

Foot position may correlate with injury risk to the lower limb during the hockey hit.

Introduction

Field hockey is a fast-paced stick and ball sport played in 132 countries worldwide.1 Players must withstand forces generated from fast running and sharp turns while also using their upper body to control and strike the ball.

Although contact injuries from the stick and ball are more common and can have serious consequences, non-contact mechanisms are significant, particularly among female players.2 The lower limb is of particular interest; Barboza et al3 carried out a systematic review of injury data and found that this was the area of the body most commonly injured during hockey, more specifically the knee and ankle with the literature vague on whether the injuries occur through hitting or running. The complex cutting manoeuvres and high-power swing motions required to distribute the ball create a high risk of overuse injury, particularly to the ligaments of the knee and lateral ankle.4 However, limited literature exists on the biomechanics of the sport and how this relates to non-contact injury mechanisms.

Degree of angulation and magnitude of moments around a joint are factors known to correlate with the risk of injury, as they play a key role in the biomechanics of the joint.5–7 Since the lower limb joints allow limited degrees of angulation, particularly in the coronal and transverse planes,8 a foot position that results in angulation of the foot close to its maximum angle, in the respected plane of motion, will increase the risk of injury. Furthermore, there are a number of factors that influence how the magnitude of a force will affect the joint, such as the strength of surrounding muscles. Therefore, there is not a particular magnitude of moment that can be stated as the threshold for injury, making it difficult to quantify the risk of injury. However, through comparison of the four positions against one another, the one that produced the smallest moments the most often, and largest moments the least often, could be said to carry the smallest risk of injury.

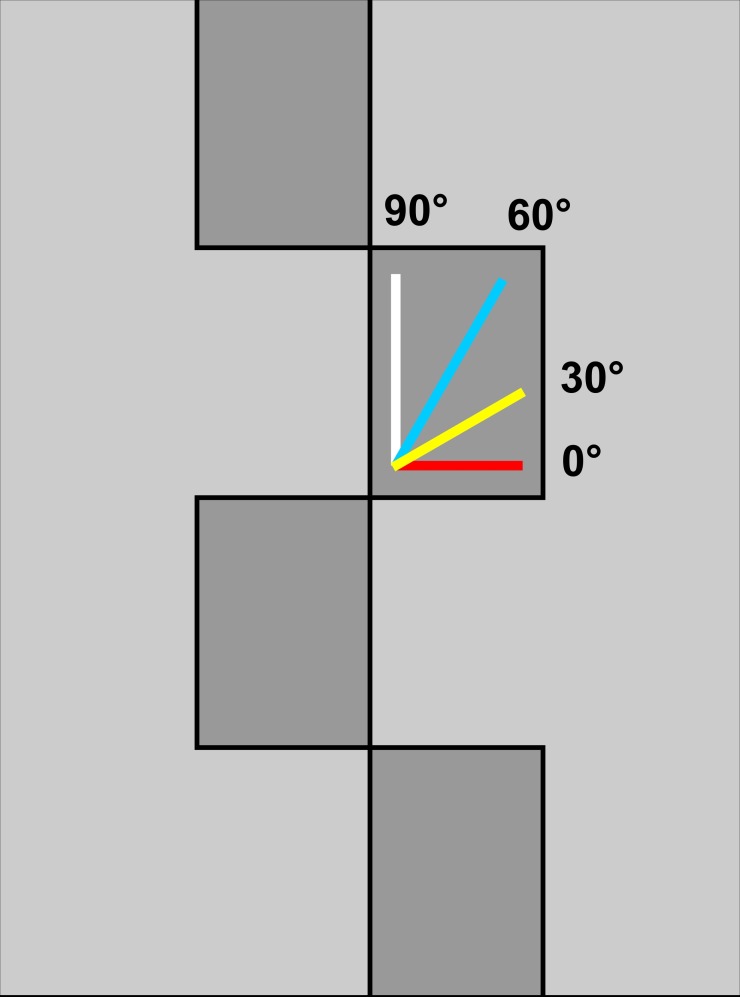

There were four foot positions tested in the present study: 0°, 30°, 60° and 90°, relative to the axes of the force plate used to gather motion analysis data. In hockey, a side on stance is common, with the front foot placed at a diagonal to the line of movement of the ball. In this position, the front-foot faces in a similar direction to the rest of the body, with minimal rotation of the ankle joint relative to the body. In the present study, this foot position was defined as 30°. In order to gather motion analysis data with both a smaller and larger degree of angulation at the ankle, a further three foot positions, defined as 0°, 60° and 90° were also tested.

A foot position of 90°was the highest degree included because this results in the foot pointing in the direction of movement. A fourth angle of 60° was included for a more thorough comparison of foot positions between the two extremes of 0° and 90°.

The effect of foot position during a drag flick, a type of stroke performed in hockey when shooting at goal, was investigated by Wild et al.9 The authors proposed that an externally rotated lead foot position during this stroke increases the force at the ankle joint. The hit, which was analysed in the present study, is relevant to a wider range of hockey players than the drag flick, as it is used in all aspects of the game. Therefore, understanding the biomechanics of this stroke is highly relevant.

It appears that adaptation of foot orientation is possible through appropriate training. A recent study involving a neuromuscular training programme for hockey players classed as having unstable ankles resulted in a positive effect on the participants’ ankle positioning.10

This study aimed to propose a lead foot position during the hockey hit that results in the smallest joint angles and moments, from a total of four different foot positions: 0°, 30°, 60° and 90°. The null hypothesis of this study was that no relationship exists between lead foot position and the angles and moments produced during a hockey hit.

Materials and methods

Patient and public involvement

Twenty female hockey players were recruited from the local University Ladies Hockey Club. Volunteers were recruited through a poster being displayed in the hockey club and were given a participant information sheet prior to the study commencing. Participants were required to have played a minimum of one season of competitive hockey and have no significant injuries that precluded them from playing the year before the study was conducted.

Procedure

Motion analysis data were collected using the Vicon Nexus system V.2.6.1 (using 14 MXF40 cameras and 4 AMTI force plates BP600400). Coloured tape was used to mark the four foot positions on one of the four force plates, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Foot positions.11

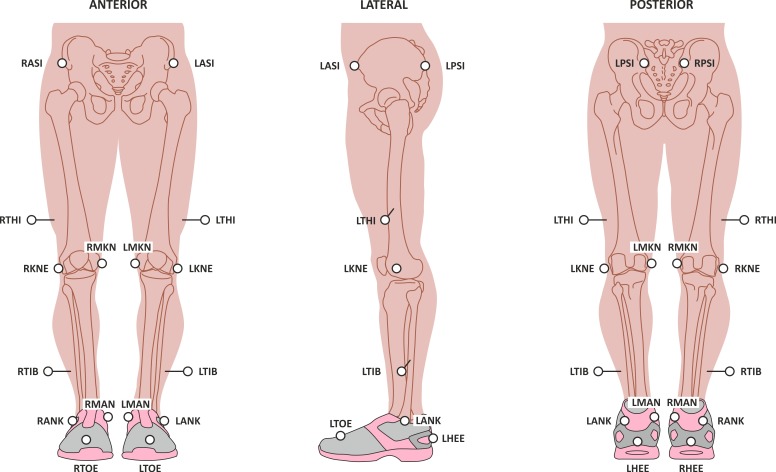

Before collecting data, each participant was provided with a standardised pair of hockey shoes in the appropriate size to minimise any variations that could be attributed to footwear. Anthropometric data were recorded. Sixteen retroreflective markers were then attached at the following bony landmarks: anterior superior iliac spine, sacral dimple, medial and lateral femoral epicondyle, medial and lateral malleoli, posterior calcanei and between the first and second metatarsal heads. A further four wand markers were placed on each lateral thigh and calf (figure 2). Following calibration of the laboratory, participants were provided with a ball and a standard hockey stick that matched their height and asked to practice performing the hit until the participant and lead investigator agreed that they were familiar with the experimental setup. The hit was then performed while stepping onto the force plate. The trial was considered successful if the motion was performed correctly, with their whole foot on the force plate, and at the required angle. Data were collected until five successful trials at all four foot positions were recorded, from each participant.

Figure 2.

Marker placement.12LANK, left ankle (lateral); LASI, left asis; LHEE, left heel; LKNE, left knee (lateral); LMANK, left ankle (medial); LMKNE, left knee (medial); LPSI, left psis; LTHI, left thigh; LTIB, left tibia; LTOE, left toe; RANK, right ankle (lateral); RASI, right asis; RHEE, right heel; RKNE, right knee (lateral); RMANK; right ankle (medial); RMKNE, right ankle (medial); RPSI, right psis; RTHI, right thigh; RTIB, right tibia; RTOE, right toe;

Data analysis

Vicon software was used to label successful trials. Trials were disregarded if any of the markers were missing, if the foot position was not at the required angle, or if the foot was not completely within the boundary of the force plate. This was the case for two participants, so data from eighteen participants was analysed.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS system V.22 was used to analyse the data. Analysis and comparison between foot positions was carried out using the general linear model and pairwise comparisons. Four groups were formed using information from all 18 participants at each foot position. A significant difference was reported if the p value was<0.05.

Results

Of the 18 participants whose data were analysed, the mean age was 20 years (SD 1.0); the mean height was 167 cm (SD 5.2) and the mean mass was 64.2 kg (SD 5.7).

Graphs were created to clearly display the trends of angles and moments between the foot positions.

Due to lateral ankle sprains and internal knee injury being the most common injuries in hockey, particular focus was paid to the planes of motion in which these could occur. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were found between the angles and moments of all four foot positions tested.

The effect size, CIs and p values for all comparisons made are shown in tables 1 and 2, for ankle and knee data, respectively.

Table 1.

Ankle data

| Event type | Mean difference | SE | P value | 95% CI for difference | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

|

Plantarflexion angles (degrees) |

0 | 30 | 1.381 | 2.162 | 0.526 | 5.718 | 2.956 |

| 60 | 3.288 | 1.970 | 0.101 | 0.663 | 7.238 | ||

| 90 | 0.919 | 1.736 | 0.599 | 2.563 | 4.401 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 1.381 | 2.162 | 0.526 | 2.956 | 5.718 | |

| 60 | 4.669* | 1.607 | 0.005 | 1.445 | 7.893 | ||

| 90 | 2.300 | 1.647 | 0.168 | 1.003 | 5.603 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 3.288 | 1.970 | 0.101 | 7.238 | 0.663 | |

| 30 | 4.669* | 1.607 | 0.005 | 7.893 | 1.445 | ||

| 90 | 2.369 | 1.364 | 0.088 | 5.105 | 0.367 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 0.919 | 1.736 | 0.599 | 4.401 | 2.563 | |

| 30 | 2.300 | 1.647 | 0.168 | 5.603 | 1.003 | ||

| 60 | 2.369 | 1.364 | 0.088 | 0.367 | 5.105 | ||

|

Plantarflexion moments (Nmm/kg) |

0 | 30 | 151.735* | 27.226 | 0.000 | 97.127 | 206.344 |

| 60 | 148.726* | 28.901 | 0.000 | 90.757 | 206.694 | ||

| 90 | 133.799* | 29.298 | 0.000 | 75.035 | 192.562 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 151.735* | 27.226 | 0.000 | 206.344 | 97.127 | |

| 60 | 3.009 | 18.310 | 0.870 | 39.735 | 33.716 | ||

| 90 | 17.936 | 13.642 | 0.194 | 45.299 | 9.427 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 148.726* | 28.901 | 0.000 | 206.694 | 90.757 | |

| 30 | 3.009 | 18.310 | 0.870 | 33.716 | 39.735 | ||

| 90 | 14.927 | 14.173 | 0.297 | 43.354 | 13.500 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 133.799* | 29.298 | 0.000 | 192.562 | 75.035 | |

| 30 | 17.936 | 13.642 | 0.194 | 9.427 | 45.299 | ||

| 60 | 14.927 | 14.173 | 0.297 | 13.500 | 43.354 | ||

|

Inversion angles (degrees) |

0 | 30 | 0.329 | 0.665 | 0.623 | 1.663 | 1.006 |

| 60 | 3.260* | 0.609 | 0.000 | 4.480 | 2.039 | ||

| 90 | 3.718* | 0.621 | 0.000 | 4.964 | 2.472 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 0.329 | 0.665 | 0.623 | 1.006 | 1.663 | |

| 60 | 2.931* | 0.499 | 0.000 | 3.932 | 1.930 | ||

| 90 | 3.389* | 0.473 | 0.000 | 4.339 | 2.440 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 3.260* | 0.609 | 0.000 | 2.039 | 4.480 | |

| 30 | 2.931* | 0.499 | 0.000 | 1.930 | 3.932 | ||

| 90 | 0.458 | 0.370 | 0.221 | 1.202 | 0.285 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 3.718* | 0.621 | 0.000 | 2.472 | 4.964 | |

| 30 | 3.389* | 0.473 | 0.000 | 2.440 | 4.339 | ||

| 60 | 0.458 | 0.370 | 0.221 | 0.285 | 1.202 | ||

|

Inversion moments (Nmm/kg) |

0 | 30 | 13.662 | 9.341 | 0.149 | 5.074 | 32.398 |

| 60 | 7.296 | 11.515 | 0.529 | 15.800 | 30.392 | ||

| 90 | 35.935* | 10.993 | 0.002 | 57.984 | 13.885 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 13.662 | 9.341 | 0.149 | 32.398 | 5.074 | |

| 60 | 6.366 | 9.668 | 0.513 | 25.757 | 13.026 | ||

| 90 | 49.597* | 9.965 | 0.000 | 69.584 | 29.609 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 7.296 | 11.515 | 0.529 | 30.392 | 15.800 | |

| 30 | 6.366 | 9.668 | 0.513 | 13.026 | 25.757 | ||

| 90 | 43.231* | 8.481 | 0.000 | 60.242 | 26.220 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 35.935* | 10.993 | 0.002 | 13.885 | 57.984 | |

| 30 | 49.597* | 9.965 | 0.000 | 29.609 | 69.584 | ||

| 60 | 43.231* | 8.481 | 0.000 | 26.220 | 60.242 | ||

|

Internal rotation angles (degrees) |

0 | 30 | 1.543 | 1.587 | 0.335 | 1.641 | 4.726 |

| 60 | 10.446* | 1.944 | 0.000 | 6.548 | 14.345 | ||

| 90 | 19.196* | 2.235 | 0.000 | 14.713 | 23.680 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 1.543 | 1.587 | 0.335 | 4.726 | 1.641 | |

| 60 | 8.904* | 2.197 | 0.000 | 4.497 | 13.310 | ||

| 90 | 17.654* | 2.245 | 0.000 | 13.152 | 22.156 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 10.446* | 1.944 | 0.000 | 14.345 | 6.548 | |

| 30 | 8.904* | 2.197 | 0.000 | 13.310 | 4.497 | ||

| 90 | 8.750* | 2.070 | 0.000 | 4.598 | 12.902 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 19.196* | 2.235 | 0.000 | 23.680 | 14.713 | |

| 30 | 17.654* | 2.245 | 0.000 | 22.156 | 13.152 | ||

| 60 | 8.750* | 2.070 | 0.000 | 12.902 | 4.598 | ||

|

Internal rotation moments (Nmm/kg) |

0 | 30 | 4.677 | 12.595 | 0.712 | 29.939 | 20.584 |

| 60 | 29.925* | 12.834 | 0.024 | 55.665 | 4.184 | ||

| 90 | 25.776 | 14.033 | 0.072 | 53.923 | 2.371 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 4.677 | 12.595 | 0.712 | 20.584 | 29.939 | |

| 60 | 25.247 | 13.000 | 0.057 | 51.322 | 0.828 | ||

| 90 | 21.099 | 14.327 | 0.147 | 49.835 | 7.638 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 29.925* | 12.834 | 0.024 | 4.184 | 55.665 | |

| 30 | 25.247 | 13.000 | 0.057 | 0.828 | 51.322 | ||

| 90 | 4.148 | 12.844 | 0.748 | 21.614 | 29.911 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 25.776 | 14.033 | 0.072 | 2.371 | 53.923 | |

| 30 | 21.099 | 14.327 | 0.147 | 7.638 | 49.835 | ||

| 60 | 4.148 | 12.844 | 0.748 | 29.911 | 21.614 | ||

*Highlights data: p<0.05.

Table 2.

Knee data

| Event type | Mean difference | SE | P value | 95% CI for difference | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Flexion angles (degrees) | 0 | 30 | 0.445 | 1.053 | 0.674 | 2.556 | 1.667 |

| 60 | 4.027* | 1.124 | 0.001 | 6.282 | 1.772 | ||

| 90 | 6.149* | 1.390 | 0.000 | 8.937 | 3.360 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 0.445 | 1.053 | 0.674 | 1.667 | 2.556 | |

| 60 | 3.582* | 1.150 | 0.003 | 5.889 | 1.276 | ||

| 90 | 5.704* | 1.147 | 0.000 | 8.005 | 3.403 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 4.027* | 1.124 | 0.001 | 1.772 | 6.282 | |

| 30 | 3.582* | 1.150 | 0.003 | 1.276 | 5.889 | ||

| 90 | 2.122* | 1.020 | 0.042 | 4.167 | 0.076 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 6.149* | 1.390 | 0.000 | 3.360 | 8.937 | |

| 30 | 5.704* | 1.147 | 0.000 | 3.403 | 8.005 | ||

| 60 | 2.122* | 1.020 | 0.042 | 0.076 | 4.167 | ||

| Flexion moments (Nmm/kg) | 0 | 30 | 37.741 | 43.019 | 0.384 | 48.545 | 124.027 |

| 60 | 98.725 | 55.467 | 0.081 | 12.527 | 209.977 | ||

| 90 | 196.787* | 53.372 | 0.001 | 89.736 | 303.838 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 37.741 | 43.019 | 0.384 | 124.027 | 48.545 | |

| 60 | 60.984 | 45.334 | 0.184 | 29.944 | 151.913 | ||

| 90 | 159.046* | 42.688 | 0.000 | 73.424 | 244.668 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 98.725 | 55.467 | 0.081 | 209.977 | 12.527 | |

| 30 | 60.984 | 45.334 | 0.184 | 151.913 | 29.944 | ||

| 90 | 98.062* | 46.029 | 0.038 | 5.740 | 190.384 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 196.787* | 53.372 | 0.001 | 303.838 | 89.736 | |

| 30 | 159.046* | 42.688 | 0.000 | 244.668 | 73.424 | ||

| 60 | 98.062* | 46.029 | 0.038 | 190.384 | 5.740 | ||

| Extension moments (Nmm/kg) | 0 | 30 | 98.843* | 33.914 | 0.005 | 30.822 | 166.865 |

| 60 | 254.436* | 44.212 | 0.000 | 165.759 | 343.114 | ||

| 90 | 323.881* | 46.311 | 0.000 | 230.993 | 416.769 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 98.843* | 33.914 | 0.005 | 166.865 | 30.822 | |

| 60 | 155.593* | 37.923 | 0.000 | 79.529 | 231.657 | ||

| 90 | 225.037* | 46.053 | 0.000 | 132.666 | 317.409 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 254.436* | 44.212 | 0.000 | 343.114 | 165.759 | |

| 30 | 155.593* | 37.923 | 0.000 | 231.657 | 79.529 | ||

| 90 | 69.445 | 43.330 | 0.115 | 17.464 | 156.353 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 323.881* | 46.311 | 0.000 | 416.769 | 230.993 | |

| 30 | 225.037* | 46.053 | 0.000 | 317.409 | 132.666 | ||

| 60 | 69.445 | 43.330 | 0.115 | 156.353 | 17.464 | ||

| Adduction angles (degrees) | 0 | 30 | 3.888* | 0.759 | 0.000 | 5.409 | 2.366 |

| 60 | 8.088* | 0.727 | 0.000 | 9.547 | 6.630 | ||

| 90 | 10.787* | 0.784 | 0.000 | 12.360 | 9.214 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 3.888* | 0.759 | 0.000 | 2.366 | 5.409 | |

| 60 | 4.201* | 0.536 | 0.000 | 5.277 | 3.125 | ||

| 90 | 6.899* | 0.669 | 0.000 | 8.241 | 5.558 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 8.088* | 0.727 | 0.000 | 6.630 | 9.547 | |

| 30 | 4.201* | 0.536 | 0.000 | 3.125 | 5.277 | ||

| 90 | 2.699* | 0.560 | 0.000 | 3.821 | 1.576 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 10.787* | 0.784 | 0.000 | 9.214 | 12.360 | |

| 30 | 6.899* | 0.669 | 0.000 | 5.558 | 8.241 | ||

| 60 | 2.699* | 0.560 | 0.000 | 1.576 | 3.821 | ||

| Adduction moments (Nmm/kg) | 0 | 30 | 163.446* | 32.442 | 0.000 | 228.516 | 98.376 |

| 60 | 389.585* | 33.304 | 0.000 | 456.385 | 322.786 | ||

| 90 | 499.924* | 45.099 | 0.000 | 590.381 | 409.466 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 163.446* | 32.442 | 0.000 | 98.376 | 228.516 | |

| 60 | 226.139* | 28.605 | 0.000 | 283.513 | 168.766 | ||

| 90 | 336.478* | 37.265 | 0.000 | 411.222 | 261.733 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 389.585* | 33.304 | 0.000 | 322.786 | 456.385 | |

| 30 | 226.139* | 28.605 | 0.000 | 168.766 | 283.513 | ||

| 90 | 110.338* | 33.314 | 0.002 | 177.158 | 43.518 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 499.924* | 45.099 | 0.000 | 409.466 | 590.381 | |

| 30 | 336.478* | 37.265 | 0.000 | 261.733 | 411.222 | ||

| 60 | 110.338* | 33.314 | 0.002 | 43.518 | 177.158 | ||

| Abduction angles (degrees) | 0 | 30 | 2.527* | 0.543 | 0.000 | 3.616 | 1.438 |

| 60 | 4.398* | 0.760 | 0.000 | 5.923 | 2.873 | ||

| 90 | 5.317* | 0.702 | 0.000 | 6.725 | 3.910 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 2.527* | 0.543 | 0.000 | 1.438 | 3.616 | |

| 60 | 1.871* | 0.536 | 0.001 | 2.946 | 0.796 | ||

| 90 | 2.790* | 0.528 | 0.000 | 3.850 | 1.730 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 4.398* | 0.760 | 0.000 | 2.873 | 5.923 | |

| 30 | 1.871* | 0.536 | 0.001 | 0.796 | 2.946 | ||

| 90 | .919* | 0.432 | 0.038 | 1.786 | 0.053 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 5.317* | 0.702 | 0.000 | 3.910 | 6.725 | |

| 30 | 2.790* | 0.528 | 0.000 | 1.730 | 3.850 | ||

| 60 | .919* | 0.432 | 0.038 | 0.053 | 1.786 | ||

| Abduction moments (Nmm/kg) | 0 | 30 | 101.129* | 34.395 | 0.005 | 170.117 | 32.141 |

| 60 | 203.261* | 35.802 | 0.000 | 275.071 | 131.450 | ||

| 90 | 329.079* | 33.256 | 0.000 | 395.782 | 262.376 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 101.129* | 34.395 | 0.005 | 32.141 | 170.117 | |

| 60 | 102.131* | 37.945 | 0.009 | 178.240 | 26.023 | ||

| 90 | 227.950* | 31.780 | 0.000 | 291.692 | 164.207 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 203.261* | 35.802 | 0.000 | 131.450 | 275.071 | |

| 30 | 102.131* | 37.945 | 0.009 | 26.023 | 178.240 | ||

| 90 | 125.819* | 35.845 | 0.001 | 197.714 | 53.923 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 329.079* | 33.256 | 0.000 | 262.376 | 395.782 | |

| 30 | 227.950* | 31.780 | 0.000 | 164.207 | 291.692 | ||

| 60 | 125.819* | 35.845 | 0.001 | 53.923 | 197.714 | ||

| Internal rotation angles (degrees) | 0 | 30 | 1.570* | 0.547 | 0.006 | 0.473 | 2.667 |

| 60 | 2.038* | 0.801 | 0.014 | 0.431 | 3.645 | ||

| 90 | 4.184* | 0.862 | 0.000 | 2.455 | 5.912 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 1.570* | 0.547 | 0.006 | 2.667 | 0.473 | |

| 60 | 0.468 | 0.595 | 0.435 | 0.726 | 1.662 | ||

| 90 | 2.613* | 0.694 | 0.000 | 1.222 | 4.005 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 2.038* | 0.801 | 0.014 | 3.645 | 0.431 | |

| 30 | 0.468 | 0.595 | 0.435 | 1.662 | 0.726 | ||

| 90 | 2.146* | 0.639 | 0.001 | 0.864 | 3.427 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 4.184* | 0.862 | 0.000 | 5.912 | 2.455 | |

| 30 | 2.613* | 0.694 | 0.000 | 4.005 | 1.222 | ||

| 60 | 2.146* | 0.639 | 0.001 | 3.427 | 0.864 | ||

| Internal rotation moments (Nmm/kg) | 0 | 30 | 17.640 | 9.194 | 0.060 | 36.081 | 0.800 |

| 60 | 61.764* | 10.622 | 0.000 | 83.068 | 40.459 | ||

| 90 | 71.546* | 11.499 | 0.000 | 94.610 | 48.482 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 17.640 | 9.194 | 0.060 | 0.800 | 36.081 | |

| 60 | 44.123* | 10.839 | 0.000 | 65.863 | 22.384 | ||

| 90 | 53.906* | 11.606 | 0.000 | 77.185 | 30.626 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 61.764* | 10.622 | 0.000 | 40.459 | 83.068 | |

| 30 | 44.123* | 10.839 | 0.000 | 22.384 | 65.863 | ||

| 90 | 9.783 | 12.459 | 0.436 | 34.773 | 15.207 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 71.546* | 11.499 | 0.000 | 48.482 | 94.610 | |

| 30 | 53.906* | 11.606 | 0.000 | 30.626 | 77.185 | ||

| 60 | 9.783 | 12.459 | 0.436 | 15.207 | 34.773 | ||

| External rotation angles (degrees) | 0 | 30 | 4.151* | 1.243 | 0.002 | 1.658 | 6.644 |

| 60 | 8.640* | 1.222 | 0.000 | 6.188 | 11.091 | ||

| 90 | 10.109* | 1.295 | 0.000 | 7.511 | 12.707 | ||

| 30 | 0 | 4.151* | 1.243 | 0.002 | 6.644 | 1.658 | |

| 60 | 4.489* | 1.121 | 0.000 | 2.239 | 6.738 | ||

| 90 | 5.958* | 1.209 | 0.000 | 3.534 | 8.383 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 8.640* | 1.222 | 0.000 | 11.091 | 6.188 | |

| 30 | 4.489* | 1.121 | 0.000 | 6.738 | 2.239 | ||

| 90 | 1.470 | 1.116 | 0.194 | 0.769 | 3.709 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 10.109* | 1.295 | 0.000 | 12.707 | 7.511 | |

| 30 | 5.958* | 1.209 | 0.000 | 8.383 | 3.534 | ||

| 60 | 1.470 | 1.116 | 0.194 | 3.709 | 0.769 | ||

| External rotation moments (Nmm/kg) | 0 | 30 | 1.964 | 14.036 | 0.889 | −26.188 | 30.117 |

| 60 | −12.391 | 15.724 | 0.434 | −43.930 | 19.148 | ||

| 90 | −15.810 | 12.942 | 0.227 | −41.769 | 10.149 | ||

| 30 | 0 | −1.964 | 14.036 | 0.889 | −30.117 | 26.188 | |

| 60 | −14.355 | 12.183 | 0.244 | −38.791 | 10.080 | ||

| 90 | −17.774 | 11.806 | 0.138 | −41.455 | 5.907 | ||

| 60 | 0 | 12.391 | 15.724 | 0.434 | −19.148 | 43.930 | |

| 30 | 14.355 | 12.183 | 0.244 | −10.080 | 38.791 | ||

| 90 | −3.419 | 12.410 | 0.784 | −28.311 | 21.473 | ||

| 90 | 0 | 15.810 | 12.942 | 0.227 | −10.149 | 41.769 | |

| 30 | 17.774 | 11.806 | 0.138 | −5.907 | 41.455 | ||

| 60 | 3.419 | 12.410 | 0.784 | −21.473 | 28.311 | ||

*statistically significant (p <0.05)

Ankle

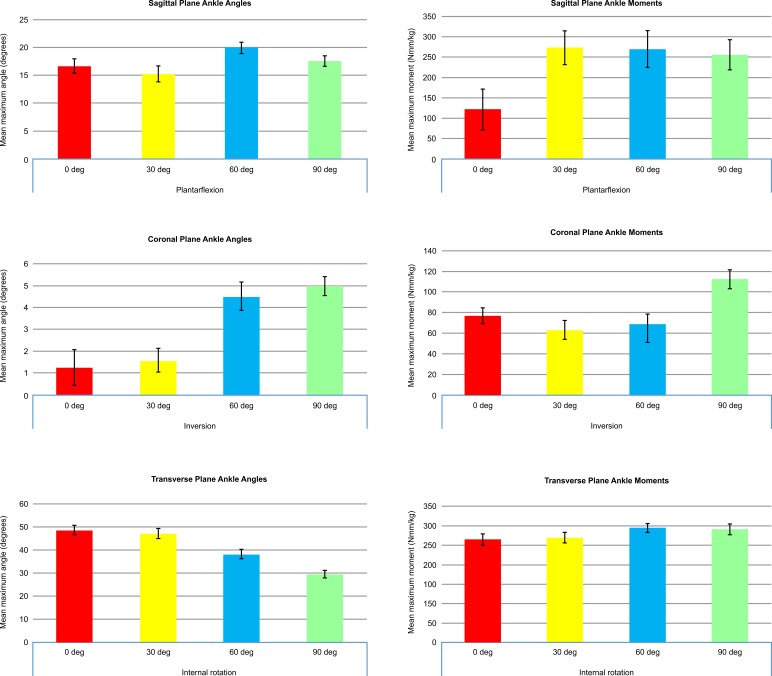

Plantarflexion

Angles

The maximum plantarflexion angles were lowest at a foot position of 30° with a mean of 15.3°, and highest at 60° with a mean of 20°. The only significant difference was between 30° and 60° (p<0.05).

Moments

Angle 0° produced the lowest maximum plantarflexion moment of the four foot positions (121 Nmm/kg), and this degree was significantly different (p<0.001) from the other three, of which 30° produced the highest result (273 Nmm/kg). There were no significant differences between 30°, 60° or 90°.

Inversion

Angles

As seen in figure 3, the two foot positions that produced the lowest maximum inversion angles were 0° and 30°, between which no significant difference was found. Foot positions of 90° and 60° produce the highest inversion angles and no significant difference was found between them. However, significant differences were found between 0° and both 60° and 90°, and 30° and both 60° and 90° (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Ankle graphs.

Moments

Figure 3 shows that 30° and 60° produced the smallest inversion moments of the four positions and were not significantly different from each other. The maximum moment at 90° (113 Nmm/kg), which was the highest of the four positions, was significantly different from 0° (p<0.05) and of greater significant difference from 30° and 60° (p<0.001). No significant differences were found between 0°, 30° and 60°.

Internal rotation

Angles

In the transverse plane, internal rotation angles decreased from a foot position of 0° to that of 90°, with mean angles of 48.7° and 29.5°, respectively. Significant differences were found between all four foot angles (p<0.001) except between 0° and 30°, which produced the highest degrees of internal rotation and were not statistically significant from each other.

Moments

Furthermore, 60° produced the highest internal rotation moments (295 Nmm/kg) and this result was significantly different from that of 0° (p<0.05), which produced the lowest (265 Nmm/kg). However, there are no significant differences between any of the other positions.

Knee

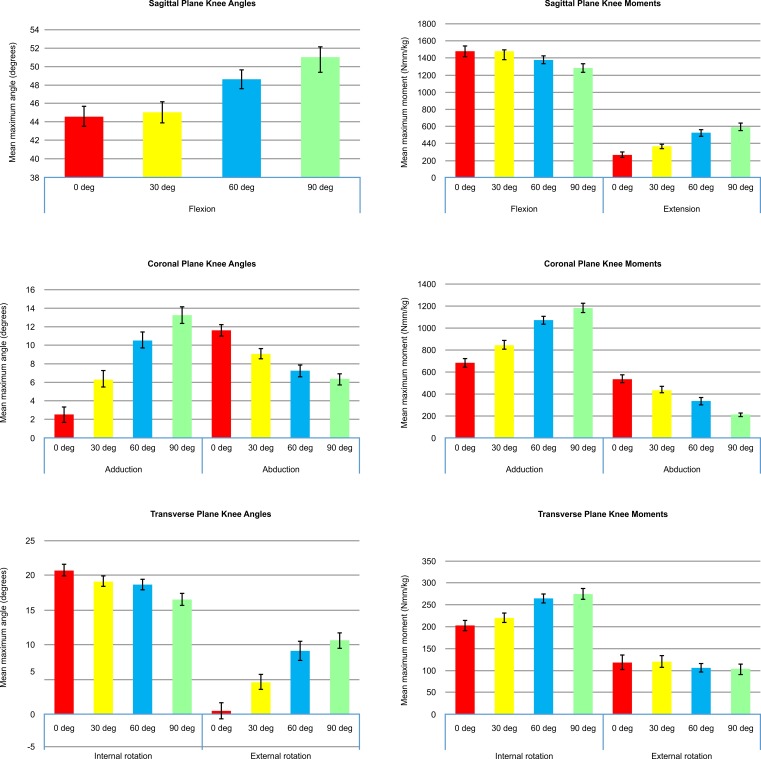

Flexion

Angles

For flexion at the knee, 0° and 30°produced the lowest angulation (44.6° of angulation for 0° foot position), and there was no significant difference between them. The highest mean flexion was recorded from 90° with a mean angle of 50.7°. Very significant differences were found between 90° with both 0° and 30° and also with 60° and 0° (p<0.001). Significant differences were also found between 60° and both 30° and 90° (p<0.05).

Moments

For flexion at the knee, a foot position of 90° produced the lowest maximum flexion moments with a mean of 1282 Nmm/kg, while 0° produced the highest with a mean of 1479 Nmm/kg. The result for 90° was significantly different to that of 60° (p<0.05) and of greater significant difference to 0° and 30° (p<0.001).

Extension

Angles

No knee extension angles were recorded.

Moments

For extension at the knee, a foot position of 90° produced the highest maximum extension moments, with a mean of 591 Nmm/kg. This result was significantly different from the maximum moments produced at foot positions of both 0° and 30°, of which the mean extension moments were 267 Nmm/kg and 366 Nmm/kg, respectively (p<0.001).

Adduction

Angles

Very significant differences were found between adduction angles of all foot positions (p<0.001), the lowest resulting from 0° and the highest from 90°.

Moments

A foot position of 0° produced the lowest adduction moments (683 Nmm/kg) and 90° produced the highest (1183 Nmm/kg). A significant difference was found between 60° and 90° (p<0.05) and greater significant differences were found between all other foot positions (p<0.001).

Abduction

Angles

For abduction, 90° produced the lowest angulation of 6.3° and 0° produced the highest of 11.6°. A significant difference was found between 60° and 90° (p<0.05) and very significant differences were found between all other foot positions (p<0.001).

Moments

For abduction, the trend followed the opposite direction, with the highest moments at 0° (539 Nmm/kg). Significant differences were found between 30° and both 0° and 60° (p<0.05). Even greater significant differences were found between 60° and both 0° and 90°, and between 90° and both 0° and 30° (p<0.001).

Internal rotation

Angles

Figure 4 displays a trend of decreasing internal rotation angles from 0° to 90°. For internal rotation angles, very significant differences were found between 90° and both 0° and 30° (p<0.001). Significant differences were also found between 0° and 30° and also 60° with both 0° and 90° (p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Knee graphs.

Moments

The foot positions that produced the lowest internal rotation moments were 0° and 30°, with no significant difference between them. The lowest was 0° with a mean moment of 202 Nmm/kg. The highest internal rotation moments were produced at 60° and 90°, with no significant difference between them. The highest was 90° with a mean moment of 274 Nmm/kg. Significant differences were found between both 0° and 30° with both 60° and 90° (p<0.001).

External rotation

Angles

The lowest external rotation angle was found to be at 0° with a mean of 0.5°, and the highest angle was found at 90° with a mean of 10.6°. A significant difference was found between 0° and 30° (p<0.05). Very significant differences were found between all other foot positions (p<0.001), except between 60° and 90°, where there was no significant difference.

Moments

No significant differences were found for external rotation moments between any of the four foot positions.

Discussion

This study investigated which foot position (0°, 30°, 60° or 90°) produced the smallest and largest degrees of angulation and moments, in the lead ankle and knee joints, during the hockey hit.

Ankle summary

Ankle injury in hockey most commonly involves the lateral ligaments3 which usually occurs when the foot is inverted, internally rotated and plantarflexed.5 The highest degrees of ankle inversion were found at foot positions of 0° and 90° and that of internal rotation was found at a foot position of 0°. Although 0° consistently produced the highest angulation, 90° caused the most significantly high moments. Therefore, rather than one particular foot position, it seems that the extremes of foot position collectively lead to larger degrees of angulation and magnitudes of moment. In contrast, 30° was the foot position that most consistently produced the lowest degrees of angulation and moments.

Knee summary

For the knee, moments in the coronal plane were significantly higher at foot positions of 0° and 90° compared with 30° (p<0.001), and moments in the transverse plane were significantly higher at both 60° and 90° than 0° and 30° (p<0.001).

Limitations

This study is an exploratory study to aid future research and hence the relatively low number of participants. While the surface on which the hit was performed did not replicate normal playing conditions, the key focus of the study was to propose the best foot position from the four positions investigated. As such, the surface was constant throughout the study, hence the four foot positions could be directly compared against one another. Furthermore, the proposed foot position of 30° may not be the most appropriate for all hockey players and it is not expected that a player would be able to consistently implement this into their play. However, alignment of the lower limb could become a more prominent aspect of hockey coaching and could be of particular relevance to players with a history of injury.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was fulfilled, indicating that lead foot position is related to the angles and moments produced in the lower limb joints during the hockey hit, and the null hypothesis can, therefore, be rejected. A lead foot position of 30° resulted in the smallest degrees of angulation, and magnitude of moment, the most often, and the largest the least often. This correlates to a lead foot that is in line with the rest of the body, while carrying out the hockey hit. The idea that this may be correlated with injury risk would require testing via either an intervention or epidemiological study, and if this idea was confirmed, a specific intervention associated with foot position during the hockey hit may decrease the risk of injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ian Christie for his valuable assistance in the production of bespoke images.

Footnotes

Contributors: FEF: planning the study, conducting the study, analysing the data, reporting the study, generating the draft write-up—responsible for overall content as guarantor. GPA: data collection for study and Vicon markers repeatability. SN: data collection for study and Vicon software reliability. WWW: statistical analysis of data. RA: reporting the study, revising the original and revision manuscript critically for intellectual content, submitting the study—responsible for overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded internally by the department.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Medical School Research Ethics Committee—ID: SMED REC 069/17.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Theilen T-M, Mueller-Eising W, Wefers Bettink P, et al. Injury data of major international field hockey tournaments. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:657–60. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston T, Brown S, Kaliarntas K, et al. Non-Contact injury incidence and warm up observation in hockey in Scotland. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:e4.10–e4. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096952.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barboza SD, van Mechelen W, Verhagen E. Monitoring field hockey injuries: the first step for prevention. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:312.1–312. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097372.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ncaa.org The National collegiate athletic association, 2009. Available: https://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/NCAA_FieldHockey_Injuries_HiRes.pdf [Accessed 6 Jan 2018].

- 5.Kerr R, Arnold GP, Drew TS, et al. Shoes influence lower limb muscle activity and may predispose the wearer to lateral ankle ligament injury. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2009;27:318–24. 10.1002/jor.20744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramanathan AK, Parish EJ, Arnold GP, et al. The influence of shoe sole's varying thickness on lower limb muscle activity. Foot and Ankle Surgery 2011;17:218–23. 10.1016/j.fas.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramanathan AK, Wallace DT, Arnold GP, et al. The effect of varying footwear configurations on the peroneus longus muscle function following inversion. Foot 2011;21:31–6. 10.1016/j.foot.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brockett CL, Chapman GJ. Biomechanics of the ankle. Orthop Trauma 2016;30:232–8. 10.1016/j.mporth.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wild C, Rosalie S, Sherry D, et al. The relationship between front foot position and lower limb and lumbar kinetics during a DraG flick in specialist hockey players. J Sci Med Sport 2017;20:e26 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.12.063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim T, Kim E, Choi H. Effects of a 6-week neuromuscular rehabilitation program on Ankle-Evertor strength and postural stability in elite women field hockey players with chronic ankle instability. J Sport Rehabil 2017;26:269–80. 10.1123/jsr.2016-0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie IS. Force_plates_plan_view.jpg. [Art] (Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, University of Dundee) 2018.

- 12.Christie IS. Lower_limb_marker_placement.jpg [custom image] ©. [Art] (Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, University of Dundee) 2018.