Abstract

Background

Children are believed to be the most vulnerable group to leprosy. Childhood leprosy reflects disease transmission in the community as well as the efficiency of ongoing disease control programmes. In Cuba, leprosy is not a national health problem; however, new childhood leprosy cases are diagnosed every year.

Objective

We summarise the experience of Cuba on childhood leprosy control over the past two decades.

Results

Between 2000 and 2017, a total of 103 children in Cuba have been diagnosed with leprosy, showing that active transmission of cases remains in 13 of 15 provinces of Cuba. The majority of cases were multibacillary (66%), and 34% were paucibacillary cases. Clinically 60% of children have more than five lesions all over their body. Voluntary reporting was the principal method of case detection. The presence of familial and extrafamilial contact with leprosy cases may be a cause of concern, as it implies continuing transmission of the disease. Only four children had disabilities (one with grade 2 disabilities and three with grade 1 disabilities). A set of national investigations have been developed to intervene in a timely manner. Intervention strategies that combine clinical surveillance and laboratory test could be an option for early detection of childhood leprosy.

Conclusions

Early detection of cases due to effective health education campaigns, regular and complete treatment with MDT, and contact tracing may be important in reducing the burden of leprosy in the community.

Keywords: dermatology, tropical infectious disease

Introduction

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. It affects the skin, mucous membranes and peripheral nerves.1 It is associated with significant morbidity, and alongside neurological damage it causes social, psychological and economic problems to the patient.2 3

Leprosy has been a major public health problem in many developing countries for centuries. The WHO reports that in 2017, 210 671 new cases were diagnosed.4 The number of new cases in the Americas (29 101) (13.8% of the global burden) is surpassed only by South-East Asia.4 5

The household contacts of a baciliferous patient can show a variable response to the infection. Some acquire the disease in its benign form, others do so in its most serious form, while others resist entry and multiplication of the bacillus.6 In children, any of the clinical forms of leprosy may occur,7 and they appear to be the most vulnerable group to M. leprae infection.8 The number of new cases detected in children under 15 years of age continues to be high. In 2017 children constituted 8.1% of new cases worldwide, with 16 979 children diagnosed and 238 children with grade 2 disabilities (see table 1).4 The diagnosis of a new case in children and adolescents shows the active transmission of the bacillus. It also indicates the magnitude of the transmission of the disease, which is directly related to the proportion of sources of infection (multibacillary forms) without treatment and the efficacy of the control programmes.9

Table 1.

WHO leprosy disability grading system

| Disability grading | Extremities | Eyes |

| 0 | Patients with no functional impairment. | No eye problem due to leprosy, no evidence of leprosy-related vision loss. |

| 1 | Loss of sensitivity (anaesthesia) in the hands or feet, but no visible deformity or damage. | Some vision impairment, but not severe (vision 6/60 or better; patients can count fingers from 2 to 6 m away). |

| 2 | Cases with both anaesthesia and complications such as trophic ulcers, claw deformities and bone resorption in the extremities. | Involves severe vision impairment (vision worse than 6/60; inability to count fingers from 2 to 6 m away); also includes lagophthalmos, iridocyclitis and corneal opacities. |

In Cuba, leprosy was no longer a national health problem in 1993, when the rate of registered prevalence of less than 1 case per 10 000 inhabitants was reached. This is according to the WHO goal and definition of eliminating the disease, and serves as a guide for control programmes in other countries. Despite the progress made in the control of the disease, the detection of new cases has remained constant.10 Every year new cases of childhood leprosy are reported. The frequency of cases with disabilities is not significant, but the multibacillary clinical forms predominate. The early diagnosis of new leprosy cases continues to be a central point in the development of control strategies to reduce the time of exposure of children to these untreated infectious sources.11

The present review summarised the Cuban experience on childhood leprosy control between 2000 and 2017.

Archived documents, medical records, disease prevalence censuses conducted since 2000, epidemiological survey, mandatory notification cards, and leprosy morbidity and mortality statistics for 2000–2017 from the National Statistics Office of the Ministry of Public Health were reviewed, along with scientific publications and the National Guidelines for Leprosy Control. The data included in this review were collected by the National Program for Leprosy Control as part of their monthly analysis of the leprosy situation in the country.

Clinical manifestations of leprosy

The diagnosis of leprosy should be based on cardinal features of leprosy. Childhood leprosy does not differ from adult leprosy but has specific characteristics.

Children at an early age, from 3 to 4 years old, suffer from the initial or infantile form of the disease12 13 (table 2). The first symptoms are usually at the neural level, with a tingling sensation (paraesthesia or acroparaesthesia), especially in the extremities. In its initial stages, macules or hypochromic and/or erythematous spots appear, which are usually of variable size, number and location, with diffuse or well-defined borders. They may be associated with disorders of superficial sensitivity (thermal, tactile and painful) and may be accompanied by alterations in sweating or in hair growth.14

Table 2.

Leprosy classification using the Cuban programme for leprosy control18 43 44

| Leprosy classification | Brief description | ||||

| WHO operational system (1987) | Ridley-Jopling (1966) |

Madrid (1953) | Number of skin lesions | Neurological damage | Bacteriology: microscopic criteria |

| Paucibacillary 1 skin lesion Paucibacillary 2–5 skin lesions |

Tuberculoide (TT) |

Tuberculoide (TT) |

Unique and infiltrated lesions | No neurological damage | Negative |

| Borderline tuberculoide (BB) | |||||

| Stasis and hypopigmented lesions | Little neurological damage | Negative | |||

| Indeterminate (IND) | |||||

| Few or many lesions of varying size | Little or no neurological damage | Negative/ 1+ | |||

| Multibacillary >5 lesions |

Borderline Borderline (BB) |

Multiple lesions, maculopapular | Late thickening of the nerves | ≥2+ | |

| Borderline lepromatous (BL) | |||||

| Multiple lesions, maculopapular, nodules | Late thickening of the nerves | >2+ | |||

| Lepromatous (LL) | |||||

| Lepromatous (LL) | |||||

| Multiple lesions, maculopapular, nodules | Late thickening of the nerves | >2+ | |||

1+ or 2+: microscopic criteria when acid fast bacilli were observed using Ziehl-Neelsen stain.

Negative: no acid fast bacilli observed.

BL, Borderline lepromatous; BT, Borderline tuberculoid; IND, Indeterminate; LL, lepromatous leprosy; TT, Tuberculoid leprosy.

In older children, around adolescence, where there is supposed to be a long time of exposure to the bacillus, other symptoms may appear more similar to those described for the polar forms of the disease. Occasionally, the only manifestation of the disease is the thickening of the superficial nerves, especially the auricular, superciliary and ulnar muscles.15

Tuberculoid and childhood nodular leprosy are the most common presentations in children. Tuberculoid leprosy presents single and small lesions. Elevated erythema with dry surface and alopecia may also be present. Childhood nodular leprosy is characterised by erythematous nodules on the face or limbs, usually a single lesion. Both forms are of benign prognosis. Some authors suggest that these two types of leprosy can disappear spontaneously and reappear over time, installing the disorder of sensitivity with the involvement of one or more peripheral nerves, face, buttocks and extremities.16 17

The less common presentations of leprosy in childhood include indeterminate and lepromatous leprosy. Indeterminate leprosy, according to the Indian classification system, consists of a single macula of non-precise edges, with sensory disturbance located mainly on the face, limbs and buttocks. Lepromatous leprosy, according to the Ridley and Jopling classification,18 is occasionally seen in children older than 5 years. The incidence of the disease increases with age. It is usually seen in children in countries with high endemicity of the disease. The clinical manifestations involve infiltration of large cutaneous areas, especially in the cartilaginous areas of the nose and ears. The mucous membranes of the nose are invaded by a large number of micro-organisms. The lesions can be hypochromic or hyperchromic, from small and single to multiple and large, including nodules.19

In cases in which a neural lesion appears, this is usually irreversible, and the loss of sensory, sympathetic and motor function ends in severe disability of the hands, feet and muscles. This leads to mutilation and deformity.20

Late diagnosis can lead to disabilities, ranging from lack of sensitivity to motor paralysis of a limb. It can also give rise to secondary lesions that are not specific to the pathology, such as burns and wounds, which if not treated properly will lead to bone destruction or reabsorption. Reaction complications are immune-mediated reactions caused by hyper-reactivity or immune complex and are considered rare in children.21

Epidemiology

In the last 5 years (2013–2017), there has been a slight decrease in the number of leprosy cases diagnosed annually, with 190 new cases in 20174 (figure 1). This diminution may suggest apparent progress. However, each year new cases of childhood leprosy are diagnosed in Cuba, which shows that active transmission of cases remains in almost all the provinces of the country (13 of 15 provinces of Cuba). It is accepted that the main mode of transmission of leprosy is through the upper airways. Multibacillary patients not undergoing treatment are the largest source of the bacillus. This is why household contacts of patients with leprosy have the highest probability of acquiring the disease. Children have a lower level of socialisation, which is why in populations where cases of childhood leprosy are diagnosed the presence of sick adults not undergoing treatment becomes evident. It is important to note that once a patient is diagnosed and treated with polychemotherapy, the disease transmission chain is eliminated due to the treatment’s high effectiveness. Figure 1 shows the number of cases of childhood leprosy and the total number of new cases diagnosed in Cuba between 2000 and 2017. In 2013, the largest number of cases of childhood leprosy was diagnosed with 11 children.2

Figure 1.

Number of cases of childhood leprosy for years and the total number of new leprosy cases diagnosed. Cuba 2000–2017. The left vertical axis represents the total number of new cases diagnosed in the country. The right vertical axis represents the total number of cases of childhood leprosy diagnosed in Cuba in the same period.

The provinces that have the most frequently reported cases in the period 2000–2017 are Granma, Santiago, Guantánamo, Ciego de Ávila and Havana.22–26

The age group most commonly affected by the disease among children under 15 years old was between 10 and 14 years (table 3). This is due to the disease’s long incubation period of approximately 3–5 years.8 The youngest patients diagnosed in Cuba were 3 years old. An equal number of boys and girls have been affected.25

Table 3.

Distribution by age of children diagnosed with leprosy in Cuba

| Years/Age | 0–4 | 5–9 | 10–14 | Total |

| 2000 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| 2001 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| 2002 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 2003 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 2004 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 2005 | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| 2006 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2007 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 2008 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| 2009 | 3 | 5 | 8 | |

| 2010 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| 2011 | 1 | 9 | 10 | |

| 2012 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| 2013 | 4 | 7 | 11 | |

| 2014 | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| 2015 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| 2016 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 2017 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Total | 2 | 28 | 73 | 103 |

In Cuba, with regard to the number of lesions, we found that 62 children of 103 diagnosed in this period had more than five lesions all over their body. We have also found that in this period one child was diagnosed with musculoskeletal manifestations, such as arthralgia and myalgia, on presentation. Additionally, another important indicator is the percentage of children with disability grades 1 and 2 among the new cases of childhood leprosy. In this period only four children had disabilities (one with grade 2 disabilities and three with grade 1 disabilities).

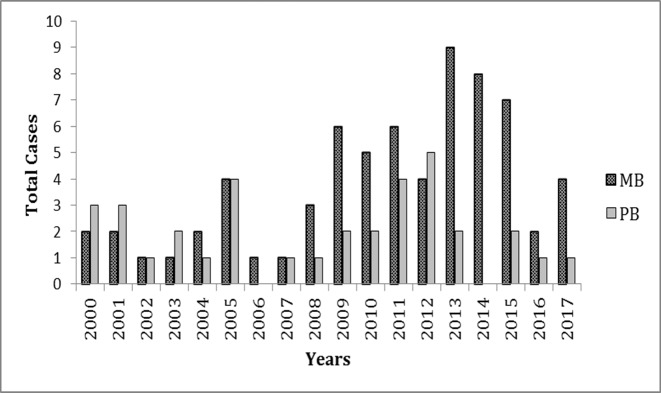

The last decade has seen an increase in multibacillary forms (BL and lepromatous leprosy) (figure 2). This is evidence, in our opinion, of the greater exposure of these children to the bacillus, due largely to sick people remaining in the community, especially multibacillary patients, without treatment.

Figure 2.

Distribution of cases of childhood leprosy per year according to operational classification, Cuba 2000–2017. MB, multibacillary patients; PB, paucibacillary patients.

Cuban strategies for leprosy control

Leprosy was a health problem in Cuba until 1993. Between 1960 and 1990, research and surveillance actions were carried out to reduce the incidence of the disease. These actions were based on the development of an inclusive control programme that allowed for active surveillance in both rural and urban populations on the island.27 These actions were based on the Cuban public health system.10 The beginning of the application of polychemotherapy in Cuba in 1988 and its inclusion in the control programme guaranteed a dramatic decrease in the incidence of the disease. As of 2003,16 when the rate of <1 case per 10 000 inhabitants at the province level was reached, a new stage begins that requires the implementation of novel strategies that allow the active search for new cases to be sustainable. All described data indicate that children who are at risk of developing the disease still escape from active surveillance. This situation has shown the need to develop strategies to improve surveillance and active search among suspected cases.

The National Program for Leprosy Control, in agreement with other Cuban health institutions (Tropical Medicine Institute Pedro Kourí, Pediatric Hospital Juan Manuel Marquez, and Provincial Center for Hygiene, Epidemiology and Microbiology of Havana), has developed intervention projects with the objective of identifying those children who are contacts of patients with leprosy earlier and proposing a follow-up strategy that allows early diagnosis.

A set of national investigations have been developed to intervene in a timely manner. Some projects considered improve the clinical dermatological evaluation of all children contacts of patients.28 29 Other strategies combine conventional methods with the use of serological methods based on phenolic glycolipid I and molecular methods to perform an initial assessment of all children who are contacts of patients with leprosy.

In general terms, the most important method for early diagnosis is the dermatological examination of signs and symptoms of leprosy in children and adults. In children, this test is very difficult to conduct. If some of the children appear to be suspicious, a bacteriological and pathological analysis is recommended. In Cuba, to diagnose leprosy in children, a total of six samples of lymph smears are taken and a biopsy of the cutaneous lesions is done for histopathological study. A new case is classified according to WHO’s classification. The treatment is also according to WHO’s recommendation5 and is controlled and supervised by local health structures (family doctors and nurses). These professionals, along with local dermatologists, are responsible for clinical surveillance of family and non-family contacts of the new case every year for 5 years.30 This method has been effective in maintaining the incidence of the disease; however, it has been ineffective in eliminating the disease. For this reason, strategies that combine this clinical surveillance with a serological follow-up of children suspected of leprosy show interesting results in terms of early diagnosis.

Also, the integration of molecular methods of diagnosis could be a great strategy for leprosy control in Cuba. Moreover, the high incidence of leprosy in some regions of the country makes us believe that contacts who do not live with children could be an important source of infection. The new strategies now include school contacts and neighbours. The options of the national control programme have been to monitor contacts suspected of leprosy by combining several methods, clinical, serological and molecular, for a period never less than 3 years.

Communication strategies have been part of the Cuban programmes, and these include active education in populations with high and low incidence of the disease, with the objective of encouraging active search for typical injuries among people and increasing risk perception.

Cuban experience in the context of other American countries

The Cuban public health system has recognised robustness, so for children with leprosy the average range in terms of the time of evolution of the skin lesions and the first consultation is less than a year, according to parents. This fairly short time between the start of the symptoms and the consultation is probably due to the easy access of patients to primary care.31 In other countries, authors refer to a time of 18 months between presentation and diagnosis.8 However, this indicator, at least in Cuba, shows an inconsistent behaviour, taking into account that in children the initial manifestations of the disease are observed predominantly in the skin and the multibacillary form takes many years to evolve.32 33 Some authors suggest that, in paediatric ages, skin alterations take years to show, and many times in the initial forms of leprosy they present as non-specific chronic dermatitis. It is clear that in Cuba we are facing a situation of little perception of risk of both the population and health professionals, due undoubtedly to the drastic decrease of new cases experienced in Cuba in the last decade. On the other hand, 89% of the cases diagnosed have at least one case of leprosy diagnosed in their family, so they must be diagnosed by household contact tracing.

In Cuba, some of the children presenting with leprosy are considered an index case (first case in the family). The source of infection is diagnosed after examining the children’s household contacts. In a retrospective study conducted over 20 years (1989–2006) at the Pediatric Hospital Juan Manuel Marquez, 60% of children with leprosy had a known source of infection in the family and in 48% of the cases were grandparents.28 The behaviour in the last decade has not changed because it is recognised in the literature that, especially in the case of children, family contact is the primary source of the infection.33 It is almost always an intrafamilial member. Special attention to this epidemiological pattern can help in the identification of new cases. Children do not have a mature immune system,34 and considering that predisposition to developing the disease is inherited35 36 they are the most vulnerable group. Active surveillance on this age group is therefore essential.

Romero-Montoya et al37 38 in a study of 12 children with leprosy in Colombia found that 9 of them had a household contact with a patient with leprosy. They reported that in a family where there are cases of undiagnosed leprosy, children are the ones most likely to get sick. Among the household contacts, the risk of developing the disease was up to nine times more, while for neighbourhood contacts the risk was four times more.39 Durães et al40 in Brazil demonstrated a risk of illness of 2.4 times greater than the case index in household contacts as compared with household perimeter contacts, and 2.05 if the contacts were first-degree relatives. Considering the same type of household contact, in a nuclear family it was observed that blood relatives had a higher incidence of the disease than other non-blood relatives, illustrating the genetic predisposition described in other studies.

In Cuba, several studies have been carried out using the UMELISA Hansen kit for the detection of IgM antibodies against the phenolic glycolipid I.41 In a study conducted in three Cuban provinces between 2013 and 2015, a serological follow-up was carried out every 6 months during 2 years in children’s household contacts of patients with leprosy. In this period a total of 151 children were included in the study, of whom 44 (29%) were positive for phenolic glycolipid. Of these children, 11 were diagnosed in the 3 years of the project.41 The results could serve as a basis to evaluate the use of this tool as a possible strategy for active searching for new cases of leprosy among children contacts of patients. Currently, studies have been conducted using the anti-PGL-I to evaluate the seroprevalence of household and school contacts in American hyperendemic areas. Barreto et al42 conducted a study with school children in the Amazon region and found that 777 (48.8%) of the 1592 school children proved to be seropositive for anti-PGL-I. The results suggest that in these regions there may be children with subclinical or undiagnosed infections. This is why early diagnosis is important.42 The proposal of this investigation on the Cuban experience is to use this analysis as a tool in seroprevalence studies and in supporting the active search for new cases at least among patient contacts.

The Cuban experience on leprosy control in the American region is relevant in terms of control programme strategies that could be economically sustainable for developing countries. The use of phenolic glycolipid serology I as a monitoring tool for suspected patients can be useful and sustainable even in low-income countries. However, although this proposal is not entirely new, the positive results of the Cuban experience rest on the solidity of the public health system that is completely inclusive and reaches every person in the country. Besides being unique in its operation and staggered in its structures, it allows the use of networks and strategies designed to deal with other diseases, integrated and adapted to the surveillance of leprosy.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of childhood leprosy in Cuba shows the relevance of leprosy control activities even in areas with low prevalence in order to sustain the elimination of leprosy. The intervention strategies used in Cuba have made it possible to increase the effectiveness of the active search for cases of childhood leprosy. Early detection of cases due to effective health education campaigns, regular and complete treatment with multidrug therapy (MDT), and contact tracing may be important in reducing the burden of leprosy in the community.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JLR-F made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, carried out the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the work, and made final approval of the version to be published. RRC carried out the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, made critical revision for important intellectual content, and made final approval of the version to be published. LdlCHG carried out the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, made critical revision for important intellectual content, and made final approval of the version to be published. FP carried out the revision of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, made final approval of the version to be published, and ensured that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Cardona-Castro N, Beltrán-Alzate JC, Romero-Montoya M. Clinical, bacteriological and immunological follow-up of household contacts of leprosy patients from a post-elimination area - Antioquia, Colombia. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009;104:935–6. 10.1590/S0074-02762009000600021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yadav N, Kar S, Madke B, et al. Leprosy elimination: a myth busted. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2014;5:S028–32. 10.4103/0976-3147.145197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith WCS, Odong DS, Ogosi AN. The importance of neglected tropical diseases in sustaining leprosy programmes. Lepr Rev 2012;83:121–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Weekly epidemiological record, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Global leprosy strategy 2016-2020, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araújo S, Lobato J, Reis Érica de Melo, et al. Unveiling healthy carriers and subclinical infections among household contacts of leprosy patients who play potential roles in the disease chain of transmission. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2012;107:55–9. 10.1590/S0074-02762012000900010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butlin C, Saunderson P. Children with leprosy. Lepr Rev 2014;85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dogra S, Narang T, Khullar G, et al. Childhood leprosy through the post-leprosy-elimination era: a retrospective analysis of epidemiological and clinical characteristics of disease over eleven years from a tertiary care hospital in North India. Lepr Rev 2014;85:296–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira MBBde, Diniz LM, Martins Diniz L. Leprosy among children under 15 years of age: literature review. An Bras Dermatol 2016;91:196–203. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20163661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beldarrain-Chaplé E. Historical overview of leprosy control in Cuba. MEDICC Review 2016;19:8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberts CJ, Smith WCS, Meima A, et al. Potential effect of the World Health Organization’s 2011–2015 global leprosy strategy on the prevalence of grade 2 disability: a trend analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:487–95. 10.2471/BLT.10.085662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasidharanpillai S, Binitha MP, Riyaz N, et al. Childhood leprosy: a retrospective descriptive study from government medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India. Lepr Rev 2014;85:100–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilasrao Gitte S, Ramanath S, Kamble K. Childhood leprosy in an endemic area of central India. Indian Pediatrics 2016;53:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philip M, Samson J, Ebenezer S. A ten year study of pediatric leprosy cases in a tertiary care centre in South Kerala. Indian J Lepr 2018;90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira SMB, Freitas B, Cortela D. Trend of leprosy in individuals under the age of 15 in Mato Grosso (Brazil), 2001-2013. Rev Saude Publica 2017;51:28 10.1590/S1518-8787.2017051006884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fakhouri R, Sotto MN, Manini MPI, et al. Nodular leprosy of childhood and tuberculoid leprosy: a comparative, morphologic, immunopathologic and quantitative study of skin tissue reaction. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 2003;71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez G, González R, Gonzalez D, et al. Búsqueda activa de lepra Y de otras Enfermedades de la piel en escolares de Agua de Dios. Colombia Rev Salud Publica 2007;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five-group system. Int J Leprosy 1966;34:255–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain M, Nayak C, Aderao R, et al. Clinical, bacteriological, and histopathological characteristics of children with leprosy: a retrospective, analytical study in dermatology outpatient department of tertiary care centre. Indian Journal of Paediatric Dermatology 2014;15 10.4103/2319-7250.131830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinnarasan M, Vinothiney K, Gopalan B. A clinico-epidemiological study of paediatric leprosy in a tertiary care centre. J Evolution Med Dent Sci 2018;7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumaravel S, Murugan S, Fathima S, et al. Clinical presentation and histopathology of childhood leprosy. International Journal of Scientific Study 2017;4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MINSAP Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2013. Cuba: Ministerio de Salud Pública, Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MINSAP Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2011. Cuba, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MINSAP Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2012. Cuba: Ministerio de Salud Pública. Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MINSAP Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2016. Cuba: Ministerio de Salud Pública, Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MINSAP Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2017. Cuba: Misniterio de Salud Pública, Dirección de Registros Médicos y Estadísticas de Salud, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gil Suárez R, Ramirez Fernández R, Santin Peña M, et al. Situacion actual de la lepra en cuba: sera factible la interrupcion de la transmision ? Hansen Int 1996;21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastrana Fundora F, Moredo Romo E, Ramírez Albajés C. Caracterización de Los casos de lepra Infantil atendidos en El Hospital Pediátrico Universitario Juan Manuel Márquez. Folia dermatologica de Cuba 2008;2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleites Rumbaut M, Moredo Romo E, Pastrana Fundora F, et al. Lepra indeterminada vs. Pitiriasis alba. Folia dermatologica de Cuba 2009;3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.MINSAP Lepra, Normas Tecnicas para El control Y tratamiento. editorial Ciencias Medicas, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.De la Osa J. A first-hand look at public health in Cuba. Estudios avanzados 2011;25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaschignard J, Grant AV, Thuc NV, et al. Pauci- and multibacillary leprosy: two distinct, genetically neglected diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016;10:e0004345 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurtado L, Gonzalez L, Tejera J, et al. Comportamiento clínico epidemiológico. La habana. Período 2008-2016. Fontilles Rev Leprol 2017;31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon AK, Hollander GA, McMichael A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc R Soc B 2015;282 10.1098/rspb.2014.3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardona-Castro N, Cortés E, Beltrán C, et al. Human genetic ancestral composition correlates with the origin of Mycobacterium leprae strains in a leprosy endemic population. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0004045 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardona-Castro N, Sánchez-Jiménez M, Rojas W, et al. Il-10 gene promoter polymorphisms and leprosy in a Colombian population sample. Biomédica 2012;32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romero-Montoya IM, Beltrán-Alzate JC, Ortiz-Marín DC, et al. Leprosy in Colombian children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014;33:321–2. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romero-Montoya M, Beltran-Alzate JC, Cardona-Castro N. Evaluation and monitoring of Mycobacterium leprae transmission in household contacts of patients with Hansen's disease in Colombia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11:e0005325 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendes Carvalho A. Specific antigen serologic tests in leprosy: implications for epidemiological surveillance of leprosy cases and household contacts. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2017;112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durães SMB, Guedes LS, Cunha MDda, et al. Epidemiologic study of 107 cases of families with leprosy in Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol 2010;85:339-45 10.1590/s0365-05962010000300007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz-Fuentes J, Suarez O, Pastrana F. Diagnóstico de lepra en niños mediante seguimiento serológico de anticuerpos Contra El glicolípido fenólico I. Revista Cubana de Pediatría 2019;91. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barreto JG, Guimarães LDS, Leão MRN, et al. Anti-PGL-I seroepidemiology in leprosy cases: household contacts and school children from a hyperendemic municipality of the Brazilian Amazon. Lepr Rev 2011;82:358–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization Who expert Committee on leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2012;51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta R, Kar HK, Bharadwaj M. Revalidation of various clinical criteria for the classification of leprosy-a clinical pathological study. Lep Rev 2012;83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.