Abstract

Context

Previous research from a sample of US secondary schools (n = 10 553) indicated that 67% of schools had access to an athletic trainer (AT; 35% full time [FT], 30% part time [PT], and 2% per diem). However, the population-based statistic in all secondary schools with athletic programs (n = approximately 20 000) is yet to be determined.

Objective

To determine the level of AT services and employment status in US secondary schools with athletics by National Athletic Trainers' Association district.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Public and private secondary schools with athletics.

Patients or Other Participants

Data from all 20 272 US public and private secondary schools were obtained.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Data were collected from September 2015 to April 2018 by phone or e-mail communication with school administrators or ATs and by online surveys of secondary school ATs. Employment categories were school district, school district with teaching, medical or university facility, and independent contractor. Data are presented as total number and percentage of ATs. Descriptive statistics were calculated for FT, PT, and no AT services data for public, private, public + private, and employment type by state and by National Athletic Trainers' Association district.

Results

Of the 20 272 secondary schools, 66% (n = 13 473) had access to AT services, while 34% (n = 6799) had no access. Of those schools with AT services, 53% (n = 7119) received FT services, while 47% (n = 6354) received PT services. Public schools (n = 16 076) received 37%, 32%, and 31%, whereas private schools (n = 4196) received 27%, 28%, and 45%, for FT, PT, and no AT services, respectively. Most of the Athletic Training Locations and Services Survey participants (n = 6754, 57%) were employed by a medical or university facility, followed by a school district, school district with teaching, and independent contractor. Combined, 38% of AT employment was via the school district.

Conclusions

The percentages of US schools with AT access and FT and PT services were similar to those noted in previous research. One-third of secondary schools had no access to AT services. The majority of AT employment was via medical or university facilities. These data depict the largest and most updated representation of AT services in secondary schools.

Keywords: athletic training, high schools, health care

Key Points

This is the first study to capture the level of athletic trainer (AT) services in every US high school with an athletics program.

Sixty-six percent of secondary schools in the United States had access to AT services, and of those, 53% had access to full-time services.

The majority of ATs in secondary schools (57%) were employed by medical or university facilities.

Athletic trainers (ATs) are the only allied health care practitioners specifically trained in injury prevention for the physically active1 who also provide on-site emergent and nonemergent care, coordinate appropriate follow-up, conduct rehabilitation, and return individuals to safe participation in sport.2 As such, ATs play a critical role in the promotion of safe physical activity and return to participation after injury. Furthermore, the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) position statements and best-practice documents require ATs to be educated on, and assist in, preventing or otherwise managing orthopaedic injuries,3–5 concussions,6 eating disorders,7 heat illnesses,8 lightning injuries,9 cardiac-related deaths,10 diabetic episodes,11 exertional sickling episodes,12 early-onset osteoarthritis,13 substance abuse,14 disease transmission,15 weight management,16 and dental and oral injuries17 in their scope of practice using evidence-based techniques. These prevention mechanisms are common practice for ATs and well within their scope of practice; however, many secondary schools that do not provide on-site AT services are left to implement these measures through other means. Although secondary school administrators understood the need for athlete health and safety measures, as well as the need to employ ATs as the most appropriate health care providers for this setting,12 employment of ATs in secondary schools has lagged.18–20

Although research has demonstrated that providing proper medical care to secondary school athletes minimizes the risks associated with injury and sudden death,1 that injuries are more likely to be identified and cared for by full-time (FT), school-employed ATs compared with outreach ATs,21 and that schools with ATs are more likely to report injuries such as concussions,22 nearly 34% of public and private secondary schools nationwide provided no AT services for their athletes.18 Moreover, deaths continue to occur among high school athletes during sport participation.23 For example, during the 2015–2016 season, the secondary school sport-related sudden death rate due to athletic participation increased 20% from the previous year.23 Despite an increasing number of legal cases involving secondary school athletes that have been ruled in favor of the plaintiff, court-ordered overhauling of health and safety policies, and the awarding of large settlements,24,25 school districts, school educational boards, state legislators, and state athletic associations continue to take reactive, rather than proactive, approaches to addressing these concerns. The fact remains that one-third of US secondary schools are without appropriate medical care for athletes participating in their sports. Various barriers and challenges to the hiring of ATs have been identified,18 including budgetary constraints, school size, lack of awareness of the AT's role, and public schools in remote locations.18

Despite these data, the profession of athletic training lacks a prospective, comprehensive, and research-based approach to monitoring and tracking changes in on-site AT services provided to secondary schools in the United States. Second, state athletic training associations and ATs nationally need to be able to provide real-time AT employment statistics at the national, district, and state levels for the purposes of strategic growth (eg, AT job increases), legislative initiatives (eg, scope-of-practice modifications), and enhanced interschool communication for the delivery of higher-quality health care for secondary school athletes. In these secondary school settings is the greatest potential for athletic training job market growth, with an estimated 6000 schools lacking AT services. Lastly, high school sport-participation numbers have been on the rise in recent years, and we must have accurate and up-to-date information on the on-site AT services being provided to secondary schools. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to expand on previous findings related to on-site AT services and employment status in the public and private secondary school sectors and acquire a US population-based sample from which an ongoing database can be developed and maintained.

METHODS

Procedures

All public (n = 16 076) and private (n = 4196) secondary schools with school-sanctioned interscholastic athletics programs in the 50 US states and the District of Columbia were obtained from the Athletic Training Locations and Services (ATLAS) database. All school types (public, private alternative, charter, magnet, preparatory, technical and vocational schools) that offered at least 1 of grades 9 to 12 were included. If the athletics program was a co-op or conjoined with other local area schools, the primary school athletics program was used, and the secondary school was removed. In cases where both schools reported athletics programs, both were included.

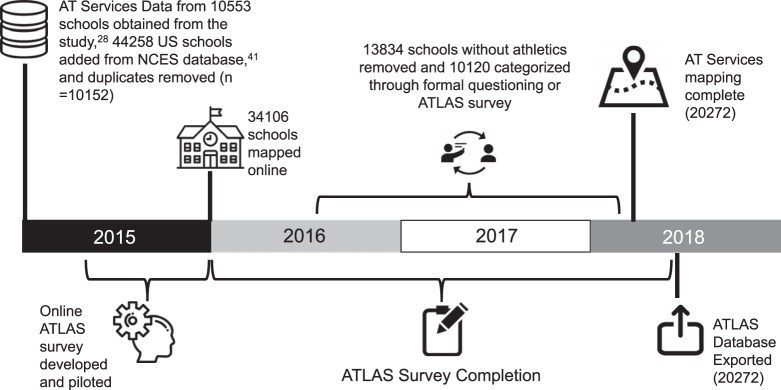

The ATLAS database contains information from a variety of sources. A timeline of the process is depicted in Figure 1. First, previously acquired data from 10 553 schools obtained from the studies by Pryor et al19 and Pike et al18,20 via the Korey Stringer Institute served as the foundation. Then, all secondary schools listed in the US Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics database were added, yielding a total of 44 258 US secondary schools. Duplicates were removed (n = 10 152) and each school was then mapped online (https://ksi.uconn.edu/nata-atlas/) using a Google-based platform (Zeemaps, Zee Source, Cupertino, CA). On each state map, we used markers to indicate schools with on-site AT services (green or teal markers), without on-site AT services (red markers), and those for which that level of on-site AT services was unknown (black markers). (Note: Throughout the manuscript, AT services are defined as on-site AT services so as not to be confused with services provided solely within a clinic). By mapping the unknown schools and making the maps public, each state and the ATs within that state were then able to assist us in categorizing the remaining schools.

Figure 1.

Timeline depicting data merging, acquisition, refinement, and mapping process for the Athletic Training Locations and Services (ATLAS) database. Also depicted is the survey development and validation, questionnaire availability and export. Abbreviations: AT, athletic trainer; NCES, National Center for Education Statistics.

Those schools identified and confirmed from the previous studies18–20 as not having AT services remained as such unless it was determined that the school had added AT services since the initial data collection. The unknown schools were researched, confirmed, and categorized by consensus of the researchers, NATA staff, NATA Secondary School Athletic Trainers' Committee (SSATC) chairs, and each state association's secondary school committee. Additionally, each of the NATA SSATC district chairs and each state association's secondary school committee chairs were provided a list of schools with unknown AT status in their states. Equipped with these lists, leaders reached out to schools via e-mail, online open-access directories of state high school athletics association member schools, phone communication, and in some cases in-person communication. During all forms of communication, a formal set of questions was asked of the school representative (which may have included the AT or other secondary school administrator): (1) “Does the school have an athletics program?”; (2) “Does the school receive health care services from an AT?” If the school answered yes to AT services, then the next questions were (3) “How many ATs provide these services?” and (4) “Can you provide us with the AT's contact information or e-mail so that we may call or send them a survey recruitment e-mail?” If the school answered no to having athletics, it was removed from the database. If the school answered yes to having athletics but no regarding the provision of health care services in the form of an AT, the school was listed in the database as having no AT services and the questioning was complete. When a school representative provided the responses and in an effort to reduce the inaccuracy of reporting, we made every attempt to garner a response from the secondary school AT who provided care to that school's athletes. If no AT was identified, then responses to the questions were gathered from the athletic director, principal or assistant principal, sport coach, or school office assistant. If both a school representative and the AT answered the questions (via phone, e-mail, or online survey), the response of the AT superseded that of the school official. Throughout the categorization process, the state lists that were shared with the NATA SSATC chairs and each state association's secondary school committee were cross-referenced by the researchers and the online maps were updated to reflect the changes to help expedite and track the progress being made in each state. Furthermore, revised working lists of schools whose AT services remained unknown were then shared with each NATA SSATC chair or state leader or liaison actively working with the researchers until the national mapping was completed (February 21, 2018).

In addition to the previously described data-acquisition questions, we used a secondary means of data procurement: the ATLAS Project database and schools previously determined to have AT services, recruitment e-mails, social media communications, blog posts, advertisements, and articles from both the NATA and the researchers asking ATs to participate in the ATLAS Survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) were distributed.26 Only schools that reported providing AT services were surveyed to obtain demographic information related to the level of AT services offered (eg, FT or part time [PT]), as well as the mode in which they were currently employed (eg, school district, school district with teaching, medical facility, hospital, clinic, university, or independent contractor).

We developed the ATLAS Survey with assistance from the NATA SSATC. Two content-area research experts, 1 with experience in secondary school athletic training research and 1 with leadership experience in the secondary school athletic training setting, and an AT graduate assistant researcher determined the content examined in the descriptive items of the questionnaire and judged the appropriateness of the items. After the questionnaire was completed and uploaded to the online platform, 4 content-area experts, 2 members of the NATA SSATC, and 2 content-area researchers with expertise in the development and administration of online surveys reviewed the questionnaire for face and content validity. After establishing face and content validity, we selected 1 state to pilot the survey and provide feedback. The responses were analyzed, and the multiple choice options were expanded to include all potential responses. Given that all items in this questionnaire are descriptive in nature, centered on a singular construct of the availability of AT services in secondary schools, the instrument did not necessitate criterion or construct validity. The questionnaire was then made publicly available via an open-access link. Annually in the month of August, additional questions were added to enhance the description of various items based on requests from the NATA and future research interests; however, the original questions remained unchanged. The additional items underwent the same face-validation and content-validation process previously described. If more than 1 AT from a school completed the questionnaire or an individual responded to the questionnaire more than once, the most recent and complete questionnaire was used. The research was reviewed and approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board.

Analyses

All files were managed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.14.1; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). Questionnaire responses were exported to comma-separated values (.csv) files and merged using common identifiers: school name, city, state, and zip code. Descriptive statistics including counts, ranges, and percentages for FT, PT and no AT services for public, private, and public + private secondary schools combined by state, by employment, and by NATA district are outlined in the following section. Full-time AT services were operationally defined as a school that received AT services for ≥30 hours per week, ≥5 days per week, and ≥10 months per year. Part-time AT services were defined as anything less than FT, and no AT services meant that at no time did the school receive any services from an AT. The highest (top 5 with the highest relative percentages) and lowest (bottom 5 lowest percentages) percentages were also reported.

RESULTS

Athletic Trainer Services by State and by NATA District

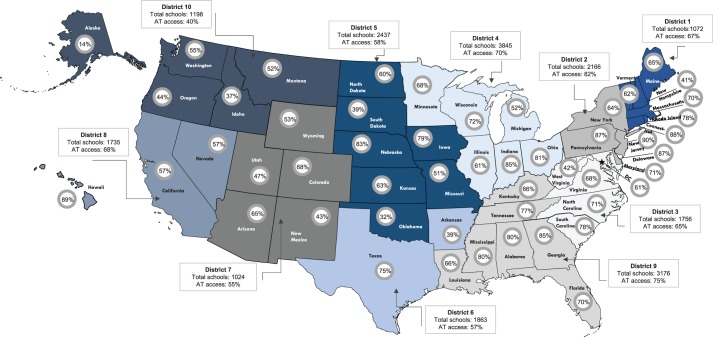

Secondary schools with athletics programs and the type and amount of AT services provided in each of the 50 US states and the District of Columbia were categorized (n = 20 272) and, furthermore, 50% (n = 6754) of the schools with AT services (n = 13 473) completed the ATLAS Survey. Descriptive statistics regarding AT services by type in US secondary schools by state and district are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Access to AT services (FT and PT combined) by state and district are presented in Figure 2. In total, 66% (n = 13 473, N = 20 272) of US secondary schools with athletics programs received AT services, while 34% (n = 6799) did not. Of those secondary schools that provided AT services, 53% (n = 7119) received FT services and 47% (n = 6354) received PT services. The state-specific percentages of levels of AT services provided ranged from 1% to 80% for FT, 8% to 60% for PT, and 10% to 86% for no AT services. New Jersey, Hawaii, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Delaware had the highest percentages of access to AT services. New Jersey, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Indiana had the highest percentages of FT services, while Nebraska, Rhode Island, Alaska, Iowa, and Connecticut had the highest percentages of PT services. The states with the highest percentages of secondary schools without AT services were Alaska, Oklahoma, Idaho, Arkansas, and North Dakota.

Table 1.

Athletic Trainer Services in US Secondary Schoolsa

| State |

District |

Public and Private Schools Combined, No. |

Public and Private Schools Combined, %b |

|||||

| Total Schools |

Full Time |

Part Time |

None |

Full Time |

Part Time |

None |

||

| Connecticut | 1 | 213 | 78 | 109 | 26 | 37 | 51 | 12 |

| Maine | 1 | 148 | 55 | 41 | 52 | 37 | 28 | 35 |

| Massachusetts | 1 | 392 | 140 | 136 | 116 | 36 | 35 | 30 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 175 | 44 | 27 | 104 | 25 | 15 | 59 |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 59 | 12 | 34 | 13 | 20 | 58 | 22 |

| Vermont | 1 | 85 | 24 | 29 | 32 | 28 | 34 | 38 |

| District totals | 1072 | 353 | 376 | 343 | 31 | 37 | 33 | |

| Delaware | 2 | 55 | 30 | 18 | 7 | 55 | 33 | 13 |

| New Jersey | 2 | 446 | 355 | 48 | 43 | 80 | 11 | 10 |

| New York | 2 | 898 | 241 | 333 | 324 | 27 | 37 | 36 |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 767 | 515 | 149 | 103 | 67 | 19 | 13 |

| District totals | 2166 | 1141 | 548 | 477 | 57 | 25 | 18 | |

| District of Columbia | 3 | 51 | 27 | 4 | 20 | 53 | 8 | 39 |

| Maryland | 3 | 298 | 131 | 80 | 87 | 44 | 27 | 29 |

| North Carolina | 3 | 522 | 236 | 137 | 149 | 45 | 26 | 29 |

| South Carolina | 3 | 293 | 177 | 53 | 63 | 60 | 18 | 22 |

| Virginia | 3 | 461 | 230 | 82 | 149 | 50 | 18 | 32 |

| West Virginia | 3 | 131 | 14 | 41 | 76 | 11 | 31 | 58 |

| District totals | 1756 | 815 | 397 | 544 | 44 | 21 | 35 | |

| Illinois | 4 | 832 | 284 | 221 | 327 | 34 | 27 | 39 |

| Indiana | 4 | 424 | 236 | 123 | 65 | 56 | 29 | 15 |

| Michigan | 4 | 789 | 139 | 271 | 379 | 18 | 34 | 48 |

| Minnesota | 4 | 440 | 123 | 175 | 142 | 28 | 40 | 32 |

| Ohio | 4 | 854 | 381 | 307 | 166 | 45 | 36 | 19 |

| Wisconsin | 4 | 506 | 152 | 210 | 144 | 30 | 42 | 28 |

| District totals | 3845 | 1315 | 1307 | 1223 | 35 | 35 | 30 | |

| Iowa | 5 | 352 | 85 | 193 | 74 | 24 | 55 | 21 |

| Kansas | 5 | 365 | 72 | 157 | 136 | 20 | 43 | 37 |

| Missouri | 5 | 604 | 141 | 168 | 295 | 23 | 28 | 49 |

| Nebraska | 5 | 298 | 68 | 178 | 52 | 23 | 60 | 17 |

| North Dakota | 5 | 157 | 20 | 41 | 96 | 13 | 26 | 61 |

| Oklahoma | 5 | 497 | 77 | 84 | 336 | 15 | 17 | 68 |

| South Dakota | 5 | 164 | 31 | 67 | 66 | 19 | 41 | 40 |

| District totals | 2437 | 494 | 888 | 1055 | 20 | 38 | 42 | |

| Arkansas | 6 | 243 | 72 | 23 | 148 | 30 | 9 | 61 |

| Texas | 6 | 1620 | 797 | 418 | 405 | 49 | 26 | 25 |

| District totals | 1863 | 869 | 441 | 553 | 39 | 18 | 43 | |

| Arizona | 7 | 283 | 109 | 76 | 98 | 39 | 27 | 35 |

| Colorado | 7 | 336 | 112 | 116 | 108 | 33 | 35 | 32 |

| New Mexico | 7 | 150 | 44 | 21 | 85 | 29 | 14 | 57 |

| Utah | 7 | 182 | 51 | 34 | 97 | 28 | 19 | 53 |

| Wyoming | 7 | 73 | 25 | 14 | 34 | 34 | 19 | 47 |

| District totals | 1024 | 341 | 261 | 422 | 33 | 23 | 45 | |

| California | 8 | 1558 | 312 | 582 | 664 | 20 | 37 | 43 |

| Hawaii | 8 | 75 | 56 | 11 | 8 | 75 | 15 | 11 |

| Nevada | 8 | 102 | 31 | 27 | 44 | 30 | 26 | 43 |

| District totals | 1735 | 399 | 620 | 716 | 42 | 26 | 32 | |

| Alabama | 9 | 474 | 127 | 250 | 97 | 27 | 53 | 20 |

| Florida | 9 | 729 | 275 | 233 | 221 | 38 | 32 | 30 |

| Georgia | 9 | 535 | 211 | 246 | 78 | 39 | 46 | 15 |

| Kentucky | 9 | 289 | 122 | 68 | 99 | 42 | 24 | 34 |

| Louisiana | 9 | 396 | 159 | 102 | 135 | 40 | 26 | 34 |

| Mississippi | 9 | 329 | 100 | 162 | 67 | 30 | 49 | 20 |

| Tennessee | 9 | 424 | 168 | 159 | 97 | 40 | 38 | 23 |

| District totals | 3176 | 1162 | 1220 | 794 | 37 | 38 | 25 | |

| Alaska | 10 | 157 | 1 | 21 | 135 | 1 | 13 | 86 |

| Idaho | 10 | 169 | 40 | 22 | 107 | 24 | 13 | 63 |

| Montana | 10 | 177 | 34 | 58 | 85 | 19 | 33 | 48 |

| Oregon | 10 | 295 | 57 | 73 | 165 | 19 | 25 | 56 |

| Washington | 10 | 400 | 98 | 122 | 180 | 25 | 31 | 45 |

| District totals | 1198 | 230 | 296 | 672 | 17 | 23 | 60 | |

| National totals | 20 272 | 7119 | 6354 | 6799 | 35 | 31 | 34 | |

The response rate in all states was 100%.

Value represents the percentage of total schools with athletics.

Table 2.

Athletic Trainer Services in US Public and Private Secondary Schools by National Athletic Trainers' Association District

| State |

District |

Public Schools |

Private Schools |

||||||||

| Total Schools, No. |

Percentagea |

Total Schools, No. |

Percentagea |

||||||||

| Services |

Full Time |

Part Time |

None |

Services |

Full Time |

Part Time |

None |

||||

| Connecticut | 1 | 145 | 92 | 33 | 59 | 8 | 68 | 78 | 44 | 34 | 22 |

| Maine | 1 | 116 | 66 | 35 | 30 | 34 | 32 | 63 | 44 | 19 | 38 |

| Massachusetts | 1 | 329 | 65 | 32 | 34 | 35 | 63 | 97 | 57 | 40 | 3 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 86 | 60 | 34 | 27 | 40 | 89 | 21 | 17 | 4 | 79 |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 43 | 74 | 16 | 58 | 26 | 16 | 88 | 31 | 56 | 13 |

| Vermont | 1 | 62 | 68 | 26 | 42 | 32 | 23 | 48 | 35 | 13 | 52 |

| District totals | 781 | 71 | 29 | 42 | 29 | 291 | 66 | 38 | 28 | 34 | |

| Delaware | 2 | 30 | 100 | 57 | 43 | 0 | 25 | 72 | 52 | 20 | 28 |

| New Jersey | 2 | 355 | 96 | 86 | 9 | 4 | 91 | 69 | 53 | 16 | 31 |

| New York | 2 | 758 | 64 | 27 | 37 | 36 | 140 | 66 | 26 | 40 | 34 |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 588 | 93 | 75 | 18 | 7 | 179 | 66 | 41 | 25 | 34 |

| District totals | 1731 | 88 | 61 | 27 | 12 | 435 | 68 | 43 | 25 | 32 | |

| District of Columbia | 3 | 36 | 53 | 44 | 8 | 47 | 15 | 80 | 73 | 7 | 20 |

| Maryland | 3 | 186 | 76 | 44 | 32 | 24 | 112 | 63 | 45 | 18 | 38 |

| North Carolina | 3 | 416 | 76 | 50 | 25 | 24 | 106 | 55 | 25 | 29 | 45 |

| South Carolina | 3 | 203 | 89 | 71 | 18 | 11 | 90 | 54 | 36 | 19 | 46 |

| Virginia | 3 | 313 | 81 | 62 | 19 | 19 | 148 | 39 | 24 | 15 | 61 |

| West Virginia | 3 | 114 | 42 | 11 | 31 | 58 | 17 | 41 | 6 | 35 | 59 |

| District totals | 1268 | 69 | 47 | 22 | 31 | 488 | 55 | 35 | 20 | 45 | |

| Illinois | 4 | 689 | 61 | 35 | 26 | 39 | 143 | 57 | 30 | 27 | 43 |

| Indiana | 4 | 349 | 90 | 60 | 30 | 10 | 75 | 61 | 36 | 25 | 39 |

| Michigan | 4 | 658 | 55 | 19 | 36 | 45 | 131 | 35 | 11 | 24 | 65 |

| Minnesota | 4 | 384 | 70 | 28 | 41 | 30 | 56 | 55 | 25 | 30 | 45 |

| Ohio | 4 | 709 | 83 | 46 | 37 | 17 | 145 | 67 | 36 | 31 | 33 |

| Wisconsin | 4 | 415 | 77 | 33 | 43 | 23 | 91 | 47 | 15 | 32 | 53 |

| District totals | 3204 | 73 | 37 | 36 | 27 | 641 | 54 | 26 | 28 | 46 | |

| Iowa | 5 | 313 | 80 | 24 | 56 | 20 | 39 | 74 | 26 | 49 | 26 |

| Kansas | 5 | 326 | 64 | 20 | 44 | 36 | 39 | 49 | 18 | 31 | 51 |

| Missouri | 5 | 500 | 51 | 24 | 27 | 49 | 104 | 54 | 21 | 33 | 46 |

| Nebraska | 5 | 261 | 81 | 22 | 59 | 19 | 37 | 95 | 30 | 65 | 5 |

| North Dakota | 5 | 148 | 37 | 12 | 25 | 63 | 9 | 67 | 22 | 44 | 33 |

| Oklahoma | 5 | 460 | 32 | 15 | 17 | 68 | 37 | 41 | 22 | 19 | 59 |

| South Dakota | 5 | 150 | 59 | 19 | 40 | 41 | 14 | 71 | 21 | 50 | 29 |

| District totals | 2158 | 58 | 19 | 38 | 42 | 279 | 64 | 23 | 41 | 36 | |

| Arkansas | 6 | 212 | 39 | 30 | 9 | 61 | 31 | 39 | 26 | 13 | 61 |

| Texas | 6 | 1340 | 80 | 55 | 25 | 20 | 280 | 50 | 21 | 30 | 50 |

| District totals | 1552 | 60 | 43 | 17 | 40 | 311 | 45 | 23 | 21 | 55 | |

| Arizona | 7 | 233 | 71 | 43 | 28 | 29 | 50 | 38 | 16 | 22 | 62 |

| Colorado | 7 | 298 | 69 | 33 | 36 | 31 | 38 | 61 | 34 | 26 | 39 |

| New Mexico | 7 | 130 | 44 | 30 | 14 | 56 | 20 | 40 | 25 | 15 | 60 |

| Utah | 7 | 133 | 61 | 37 | 24 | 39 | 49 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 92 |

| Wyoming | 7 | 71 | 55 | 34 | 21 | 45 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| District totals | 865 | 60 | 35 | 25 | 40 | 159 | 29 | 16 | 13 | 71 | |

| California | 8 | 1087 | 59 | 21 | 38 | 41 | 471 | 55 | 18 | 37 | 45 |

| Hawaii | 8 | 45 | 96 | 91 | 4 | 4 | 30 | 80 | 50 | 30 | 20 |

| Nevada | 8 | 86 | 62 | 33 | 29 | 38 | 16 | 31 | 19 | 13 | 69 |

| District totals | 1218 | 72 | 48 | 24 | 28 | 517 | 55 | 29 | 26 | 45 | |

| Alabama | 9 | 360 | 85 | 29 | 56 | 15 | 114 | 61 | 19 | 42 | 39 |

| Florida | 9 | 454 | 83 | 46 | 37 | 17 | 275 | 48 | 24 | 24 | 52 |

| Georgia | 9 | 369 | 98 | 44 | 54 | 2 | 166 | 57 | 29 | 28 | 43 |

| Kentucky | 9 | 232 | 69 | 45 | 24 | 31 | 57 | 51 | 30 | 21 | 49 |

| Louisiana | 9 | 288 | 70 | 41 | 30 | 30 | 108 | 54 | 38 | 16 | 46 |

| Mississippi | 9 | 243 | 84 | 34 | 49 | 16 | 86 | 69 | 20 | 49 | 31 |

| Tennessee | 9 | 321 | 81 | 42 | 39 | 19 | 103 | 66 | 32 | 34 | 34 |

| District totals | 2267 | 81 | 40 | 41 | 19 | 909 | 58 | 27 | 31 | 42 | |

| Alaska | 10 | 147 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 87 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 70 |

| Idaho | 10 | 147 | 38 | 26 | 12 | 62 | 22 | 27 | 9 | 18 | 73 |

| Montana | 10 | 166 | 52 | 20 | 33 | 48 | 11 | 45 | 9 | 36 | 55 |

| Oregon | 10 | 247 | 47 | 20 | 27 | 53 | 48 | 29 | 17 | 13 | 71 |

| Washington | 10 | 325 | 58 | 26 | 32 | 42 | 75 | 40 | 17 | 23 | 60 |

| District totals | 1032 | 42 | 18 | 23 | 58 | 166 | 34 | 10 | 24 | 66 | |

| National totals | 16 076 | 69 | 37 | 32 | 31 | 4196 | 55 | 27 | 28 | 45 | |

Value represents the percentage of total schools with athletics.

Figure 2.

Percentages of schools by state and National Athletic Trainers' Association district with athletic trainer (AT) services.

Descriptive data of AT services in order of NATA district and the states within each district are available in Table 1. By NATA district, Districts 2, 9, and 6 had the highest percentages of secondary schools with access to AT services (78%, 75%, and 70%, respectively; Table 2). Districts 2 and 6 also had the highest percentages of FT services. Districts 10 and 5 had the highest percentages of secondary schools without access to AT services.

Athletic Trainer Services by School Type by State

On-site AT services in the United States by secondary school type (public and private), state, and NATA district are presented in Table 2. In the public school setting, 69% of secondary schools had access to AT services, while 31% were without. Of those public secondary schools with access to AT services (n = 11 171), 54% received FT (n = 5990) and 46% (n = 5181) received PT services. The ranges of AT access, FT, PT, and no AT services in the public setting were 13% to 100%, 1% to 91%, 4% to 59%, and 0% to 87%, respectively. Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania had the highest percentages of public secondary schools with access to AT services, while Alaska, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Idaho, and Arkansas had the lowest percentages of public secondary schools with AT services. Compared with public secondary schools, private secondary schools had a 14% reduction in access to AT services, a 10% reduction in FT services, and a 4% reduction in PT services. Of those private secondary schools with access to AT services (n = 2302), 27% received FT services and, similarly, 28% received PT services. The states of Massachusetts, Nebraska, and Rhode Island, the District of Columbia, and Hawaii had the highest percentages of private secondary schools with access to AT services, while FT services were highest in the District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Delaware, and Hawaii. The states with the highest percentages of private secondary schools with PT services were Nebraska, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Mississippi, and Iowa. The states with the largest percentages of private secondary schools without AT services were Wyoming, Utah, New Hampshire, Idaho, and Alaska.

Athletic Trainer Services by School Type by NATA District

District data (Table 2) demonstrated that NATA districts 2, 3, and 6 had the highest percentages of public + private secondary schools with access to AT services; these same 3 districts also had the highest public school percentages of FT services. Districts 10, 5, and 8 had the highest percentages of secondary schools without AT services. Districts 2, 1, and 5 had the highest percentages of private secondary schools with AT access (67%, 61%, and 61%, respectively), while districts 2, 1, and 3 had the highest percentages of private secondary schools with FT services (43%, 38%, and 35%, respectively).

Athletic Trainer Employment Type

Of the 13 473 schools with access to AT services, 50% (n = 6754) of secondary schools completed the online ATLAS Survey (Table 3). Individual state response rates ranged from 26% to 100%. Eighty-four percent of ATLAS Survey respondents were from public secondary schools, while 16% were from private secondary schools. Fifty-seven percent of respondents were employed by a medical or university facility, 38% were employed by the school district (school district = 24%, school district with teaching = 14%), and 5% were independent contractors. Employment data by district revealed that Districts 3 and 10 had the highest percentages of ATLAS Survey completion (66% and 63%, respectively). Districts 6 and 8 had the highest percentages of respondents employed by the school district (80% and 63%, respectively), while district 4 had the lowest percentage (11%). Districts 4, 5, and 9 had the highest percentages of respondents employed by medical or university facilities (85%, 72%, and 72%, respectively), whereas Districts 6, 7, and 8 had the lowest percentages (18%, 40%, and 28%, respectively).

Table 3.

Employers of Athletic Trainers (ATs) in US Secondary Schools by National Athletic Trainers' Association District

| State |

District |

Schools With AT Services, No. |

Athletic Training and Locations Services Survey Response Rate, %a |

AT Employer, No. |

AT Employer, %b |

||||||

| School District |

School District + Teaching |

Hospital, Clinic, or University |

Independent Contractor |

School District |

School District + Teaching |

Hospital, Clinic, or University |

Independent Contractor |

||||

| Connecticut | 1 | 187 | 44 | 29 | 4 | 46 | 4 | 35 | 5 | 55 | 5 |

| Maine | 1 | 96 | 99 | 26 | 10 | 52 | 7 | 27 | 11 | 55 | 7 |

| Massachusetts | 1 | 276 | 42 | 51 | 17 | 42 | 7 | 44 | 15 | 36 | 6 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 71 | 70 | 17 | 4 | 26 | 3 | 34 | 8 | 52 | 6 |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 46 | 46 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 29 | 10 | 57 | 5 |

| Vermont | 1 | 53 | 100 | 18 | 3 | 27 | 5 | 34 | 6 | 51 | 9 |

| District totals | 729 | 57 | 147 | 40 | 205 | 27 | 35 | 10 | 49 | 6 | |

| Delaware | 2 | 48 | 69 | 9 | 7 | 15 | 2 | 27 | 21 | 45 | 6 |

| New Jersey | 2 | 403 | 58 | 210 | 15 | 6 | 4 | 89 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| New York | 2 | 574 | 40 | 79 | 15 | 122 | 14 | 34 | 7 | 53 | 6 |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 664 | 61 | 92 | 21 | 274 | 16 | 23 | 5 | 68 | 4 |

| District totals | 1689 | 53 | 390 | 58 | 417 | 36 | 43 | 6 | 46 | 4 | |

| District of Columbia | 3 | 31 | 97 | 26 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 87 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Maryland | 3 | 211 | 70 | 36 | 14 | 87 | 10 | 24 | 10 | 59 | 7 |

| North Carolina | 3 | 373 | 64 | 26 | 64 | 140 | 8 | 11 | 27 | 59 | 3 |

| South Carolina | 3 | 230 | 80 | 16 | 39 | 116 | 14 | 9 | 21 | 63 | 8 |

| Virginia | 3 | 312 | 59 | 72 | 53 | 55 | 3 | 39 | 29 | 30 | 2 |

| West Virginia | 3 | 55 | 27 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 27 | 13 | 53 | 7 |

| District totals | 1212 | 66 | 180 | 174 | 406 | 38 | 23 | 22 | 51 | 5 | |

| Illinois | 4 | 505 | 39 | 30 | 18 | 138 | 11 | 15 | 9 | 70 | 6 |

| Indiana | 4 | 359 | 62 | 12 | 15 | 187 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 85 | 3 |

| Michigan | 4 | 410 | 54 | 23 | 6 | 176 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 79 | 8 |

| Minnesota | 4 | 298 | 58 | 2 | 1 | 165 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 95 | 3 |

| Ohio | 4 | 688 | 42 | 4 | 16 | 267 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 91 | 2 |

| Wisconsin | 4 | 362 | 29 | 3 | 0 | 99 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 94 | 3 |

| District totals | 2622 | 46 | 74 | 56 | 1032 | 48 | 6 | 5 | 85 | 4 | |

| Iowa | 5 | 278 | 27 | 9 | 1 | 61 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 81 | 5 |

| Kansas | 5 | 229 | 34 | 9 | 3 | 57 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 74 | 10 |

| Missouri | 5 | 309 | 52 | 11 | 18 | 123 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 77 | 5 |

| Nebraska | 5 | 246 | 26 | 15 | 5 | 37 | 6 | 24 | 8 | 59 | 10 |

| North Dakota | 5 | 61 | 57 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 94 | 0 |

| Oklahoma | 5 | 161 | 76 | 31 | 17 | 67 | 8 | 25 | 14 | 54 | 7 |

| South Dakota | 5 | 98 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 15 |

| District totals | 1382 | 43 | 76 | 45 | 434 | 44 | 13 | 8 | 72 | 7 | |

| Arkansas | 6 | 95 | 67 | 10 | 13 | 41 | 0 | 16 | 20 | 64 | 0 |

| Texas | 6 | 1215 | 46 | 290 | 190 | 71 | 10 | 52 | 34 | 13 | 2 |

| District totals | 1310 | 48 | 300 | 203 | 112 | 10 | 48 | 32 | 18 | 2 | |

| Arizona | 7 | 185 | 58 | 37 | 41 | 25 | 5 | 34 | 38 | 23 | 5 |

| Colorado | 7 | 228 | 51 | 34 | 16 | 62 | 4 | 29 | 14 | 53 | 3 |

| New Mexico | 7 | 65 | 51 | 10 | 21 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 64 | 3 | 3 |

| Utah | 7 | 85 | 80 | 6 | 15 | 44 | 3 | 9 | 22 | 65 | 4 |

| Wyoming | 7 | 39 | 74 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 41 | 21 | 34 | 3 |

| District totals | 602 | 59 | 99 | 99 | 142 | 14 | 28 | 28 | 40 | 4 | |

| California | 8 | 894 | 35 | 147 | 60 | 75 | 33 | 47 | 19 | 24 | 10 |

| Hawaii | 8 | 67 | 54 | 27 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| Nevada | 8 | 58 | 69 | 5 | 6 | 25 | 4 | 13 | 15 | 63 | 10 |

| District totals | 1019 | 38 | 179 | 66 | 109 | 37 | 46 | 17 | 28 | 9 | |

| Alabama | 9 | 377 | 30 | 0 | 16 | 87 | 11 | 0 | 14 | 77 | 10 |

| Florida | 9 | 508 | 51 | 59 | 43 | 135 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 52 | 9 |

| Georgia | 9 | 457 | 45 | 20 | 22 | 151 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 74 | 5 |

| Kentucky | 9 | 190 | 52 | 8 | 5 | 84 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 86 | 1 |

| Louisiana | 9 | 261 | 68 | 11 | 31 | 123 | 12 | 6 | 18 | 69 | 7 |

| Mississippi | 9 | 262 | 35 | 3 | 4 | 83 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 91 | 1 |

| Tennessee | 9 | 327 | 55 | 18 | 7 | 148 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 82 | 4 |

| District totals | 2382 | 47 | 119 | 128 | 811 | 66 | 11 | 11 | 72 | 6 | |

| Alaska | 10 | 22 | 32 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 57 | 29 |

| Idaho | 10 | 62 | 60 | 4 | 9 | 24 | 0 | 11 | 24 | 65 | 0 |

| Montana | 10 | 92 | 64 | 5 | 4 | 45 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 76 | 8 |

| Oregon | 10 | 130 | 69 | 25 | 3 | 52 | 10 | 28 | 3 | 58 | 11 |

| Washington | 10 | 220 | 64 | 12 | 41 | 77 | 10 | 9 | 29 | 55 | 7 |

| District totals | 526 | 63 | 47 | 57 | 202 | 27 | 14 | 17 | 61 | 8 | |

| National totals | 13 473 | 50 | 1611 | 926 | 3870 | 347 | 24 | 14 | 57 | 5 | |

Value represents the percentage of total schools with athletics.

Value represents the percentage of total survey respondents.

DISCUSSION

The primary results from our analyses were that 66% of US secondary schools (both public and private combined) with athletics programs had AT services. Of the 13 473 secondary schools with AT services, 53% (n = 7119) received FT services and the remaining 47% (n = 6354) received PT services. Although a majority of secondary schools had AT services, perhaps our most critical finding from a health and safety perspective was that 34% (n = 6799) of US secondary schools with athletics programs did not have access to AT services. Additionally, we determined that there were 14% more secondary schools with AT services, 10% more secondary schools with FT services, and 4% more secondary schools with PT services in the public versus the private sector. Lastly, in the 50% of US secondary schools with AT services that responded to the ATLAS Survey (n = 6754), 57% of ATs were employed by a medical or university facility, while 38% were employed directly through the school district (school district and school district with teaching responsibilities combined).

These key findings provide insights in several important areas. First, given the 6799 US schools without AT services, a large opportunity for growth for the athletic training profession in the secondary school setting remains. It is imperative that future researchers explore this opportunity and the factors associated with the current lack of AT services provided by these schools to their athletes. Studies in this area will enhance and confirm our understanding of the potential demographic,27 socioeconomic,28 financial,29,30 geographic, and organizational barriers20,29,30 and proximity to other medical facilities30 highlighted by previous investigators in this area. Second, although our findings of reduced AT services in private versus public secondary schools are consistent with those of Pike et al,18 why private schools, despite the similar barriers involving school size, budget, and lack of awareness reported, have fewer AT services remains unknown. Future authors should examine other factors specific to private schools such as boarding versus nonboarding, legal responsibility and liability, and the sense of independent governance as opposed to the policy compliance often required by state athletic associations for the public sector. Our understanding of the factors associated with medical or university employment versus school district employment must be enhanced. To that point, if the differences among these employment models can be established, perhaps linkages to the quality of medical care and value that the AT services provide from an outcomes-based perspective can be identified. It is by examining these key questions that we can better comprehend the market for and long-term growth of the athletic training profession in secondary schools.

Our findings were consistent with those of Pryor et al,19 who demonstrated that 70% of public secondary schools had AT services, and those of Pike et al,20 who showed that 58% of private secondary schools had AT services. Furthermore, when they combined the public and private school data, Pike et al18 established that 67% of public and private secondary schools had AT services. This result was within 3% of our data (Table 4). Taken together, the consistency of these findings across all studies provides a high level of reliability regarding the percentage of secondary schools with AT services and the employment status of ATs. It is also important to note that although our definitions of FT and PT differed slightly from those used by previous researchers, the results were similar. Interestingly, if data from 1993 to 1994, first reported by Lyznicki et al31 in 1999, as well as data from 2008 reported by Lowe and Pulice32 in 2009, are taken in concert with the previous findings, the percentage of combined public + private secondary schools with AT services appears to have increased from 35% in 1993 to 67% in 2017. Based on these data, an increase in the percentage of secondary schools with AT services (32%) occurred while the number of secondary schools was simultaneously increasing. Although previous results18–20 and ours suggest that the percentage of secondary schools with AT services has plateaued in the last 4 years, the percentage of growth observed from 1993 to 2017 would suggest the numbers are increasing. However, it is important to point out that these few data points are not enough to predict or suggest true changes in the employment of ATs in this setting over time. Prospective analyses would allow for a greater understanding of the growth, decline, and saturation of AT services in this setting. Furthermore, we need continued monitoring and reporting of AT services data in the secondary school setting via projects and databases such as those described earlier.

Table 4.

Comparison of Research Examining Athletic Trainer (AT) Services in the United States

| Study |

Setting |

Total Schools, No. |

Access and Type of AT Services Reported |

||||

| AT Services, % (No.) |

FT, % (No.) |

PT, % (No.) |

No AT Services, % (No.) |

Per Diem, % (No.) |

|||

| Lyznicki et al (1999)31 | Combined | 7600 | 35 (2660)a | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Lowe and Pulice (2009)32 | Combined | 10 957a | 42 (4602) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Pryor et al (2015)19 | Public | 8509 | 70 (5930) | 37 (3145) | 31 (2619) | 30 (2579)a | 2 (199) |

| Pike et al (2016)20 | Private | 2044 | 58 (1176) | 28 (574) | 25 (501) | 42 (868)a | 4 (78) |

| Pike et al (2017)18 | Combined | 10 553 | 67 (7106) | 35 (3719) | 30 (3130) | 33 (3447)a | 3 (281) |

| Current study | Public | 16 076 | 69 (11 171) | 37 (5990) | 32 (5181) | 31 (4905) | ND |

| Current study | Private | 4196 | 55 (2302) | 27 (1129) | 28 (1173) | 45 (1894) | ND |

| Current Study | Combined | 20 272 | 66 (13 473) | 35 (7119) | 31 (6354) | 34 (6799) | ND |

Abbreviations: FT, full time; ND, no data; PT, part time.

Value calculated based on numbers reported in the study.

The overall comparison of AT services in the public, private, and combined public + private secondary schools demonstrated nearly 4 times the number of public secondary schools versus private secondary schools with athletics in the United States. Additionally, public secondary schools had increased access (+14%) to AT services. This is largely explained by the greater percentage of public secondary schools with FT services (+10%). Forty-five percent of private secondary schools with athletics programs did not have AT services. When combined, 34% (n = 6799) of public and private secondary schools nationwide did not have AT services during school-sponsored athletics. These results leave many unanswered questions related to athletes' health and safety. Specific concerns surrounding proper injury and illness diagnosis, management, and appropriate referral; preventive measures such as emergency planning and care; environmental monitoring and, if required, cancellation of activities; injury-prevention mechanisms; and risk management are left to the secondary school administrators, coaches, and the nearest emergency medical services.33 Although some secondary schools would consider these responsibilities unnecessary, in the event of a potential sudden death or catastrophic injury scenario when immediate treatment is necessary, the services of an onsite AT may be critical to the patient's survival. Also, we know from previous research34 on administrators in secondary schools that coaching staffs often are not certified in cardiopulmonary resuscitation or first aid and that 88% of the essential event-coverage components outlined by the American Academy of Pediatrics as important were not addressed in secondary schools. Survival data related to the presence of an AT or other medical personnel remain unknown, but data from the Korey Stringer Institute and National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research on sudden deaths from 2000 to 2013 indicated that 42% of respondents did not have medical services present at the time of death and an AT was not present or onsite for 62% of the deaths.35 Not all deaths are preventable or treatable (eg, anatomical cardiac abnormality), yet this reported lack of any type of medical services at the time of death must be taken into consideration by secondary school administrators, education boards, parent advocacy groups, and state high school athletics associations when assessing the level of health and safety in their sports programs and determining the need for medical services.

Our findings related to overall access to AT services in secondary schools were similar to those of previous investigators. However, we demonstrated that Districts 2, 9, and 4 had the highest percentages of public secondary schools with access to AT services: 88%, 81%, and 73%, respectively. These results were similar to those of an earlier study19 of public schools for 2 of the NATA Districts (2 and 4) but dissimilar for the next highest, District 3, which had 69% of secondary public schools with access to AT services, a 10% reduction in AT services compared with the previous findings. Of note, other large discrepancies occurred between the current study and the previous investigations. Districts 5, 6, and 8 displayed differences of −10%, −12%, and 14%, respectively. The differences observed were likely not due to actual changes in AT services provided to the secondary schools and more likely due to methodologic differences and overall response rates. For example, the observed response rates for these districts in the previous investigation were 47% (n = 150), 42% (n = 134), and 29% (n = 181), respectively, whereas our rates were 100% in all 3 districts and totals of 2158, 1552, and 1218 secondary public schools in Districts 5, 6, and 8, respectively. In any case, these values shed light on the need for accurate representations using population data rather than sampling. The same rationale is probably the case for the discrepancies in access to AT services in private schools between previous investigations and the current study. We determined that NATA Districts 2, 1, and 5 had the largest percentages of private secondary schools with AT services (68%, 66%, and 64%, respectively), whereas earlier authors showed that Districts 1, 2, and 3 were highest (76%, 62%, 61%, respectively). The largest observed difference in the access to AT services in private secondary schools was in NATA District 7: −29%. Again, this reduction was less likely due to actual reductions in AT services and more likely due to improved response rates. For example, in the earlier research, the rate for this district was 26% and a total of 46 private schools, whereas our rate was 100% and a total of 159 schools.

LIMITATIONS

This study was not without limitations. Although all data from the previous studies18–20 were updated and confirmed, data on AT services were collected from 2015 to 2018; thus, the services at a given secondary school may have changed during that time. Researchers continually updated data annually from publicly accessible information and from ATs who completed the ATLAS Survey annually for their school; still, we were not able to say with 100% certainty that the extent of AT services in this report reflects the present status of AT services and employment. However, given the magnitude of this research task, this is the best available information that can be produced in a timely manner. Furthermore, the responses provided by various types of school representatives regarding the presence of an AT may have resulted in inaccurate reporting. This would have occurred only in secondary schools that were identified as having an AT who did not complete the online ATLAS Survey.

Another limitation was that our data did not account for dual modes of AT employment. For example, we were unable to state how frequently multiple ATs in secondary schools were employed by different entities or when an AT was employed by a combination of employers (eg, 50% employed by the school district and 50% by a university). The most recent version of the ATLAS Survey (data not included in these results) has been modified with this limitation in mind so that we may be able to better address the needs of the profession and answer specific questions related to AT employment in future versions of the survey and subsequent publications.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides the most comprehensive quantification to date of AT services provided by US secondary schools with athletics programs. Sixty-six percent of US secondary schools had AT services, and most ATs were employed via a medical or university facility, followed by employment through the school district. Large differences in the access to, type of, and employment model for AT services existed among NATA regions and individual states. These data provide an update to previous research examining AT services in this setting and allow future authors to address the factors that might explain or predict AT services related to school demographics (eg, socioeconomic status, number of athletes, number of students, school locale) via upkeep of the prospective ATLAS Project database. Furthermore, these data provide evidence on which strategic secondary school health and safety initiatives can be based.

The primary novelty of these data is that every US secondary school with athletics was contacted and information regarding the extent of health care in the form of AT services was obtained. To our knowledge, not only has this never been achieved before in athletic training, but this may be the first time in recent history that AT services in every high school have been examined outside of mandatory governmental reporting. Second, this manuscript and the data herein are intended to serve as the foundation for and the springboard to future research in the secondary school setting. The ATLAS Project database was developed to provide information to the profession for the purposes of improving the health and safety of athletes, advancing the profession, improving best practices and employment, and assisting with strategic legislative initiatives. Databases such as this are developed and maintained to allow for the tracking and advancement of the athletic training profession. These efforts have the potential to provide data comparing various employment models by locale, population density, socioeconomic status, and various other factors that could improve the delivery of health care and optimize the health and safety of hundreds of thousands of student-athletes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all who assisted with and continue to contribute to the ATLAS Project. We also thank the NATA SSATC as well as the individual state athletic trainers' associations, specifically members of the secondary school committees, for their aid with the concept, design, and data collection. In addition, we recognize the more than 100 Korey Stringer Institute student workers at the University of Connecticut for their dedicated efforts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hootman JM. 2008 Physical activity guidelines for Americans: an opportunity for athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2009;44(1):5–6. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prentice WE. Focusing the direction of our profession: athletic trainers in America's health care system. J Athl Train. 2013;48(1):7–8. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaminski TW, Hertel J, Amendola N, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: conservative management and prevention of ankle sprains in athletes. J Athl Train. 2013;48(4):528–545. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valovich McLeod TC, Decoster LC, Loud KJ, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: prevention of pediatric overuse injuries. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):206–220. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padua DA, DiStefano LJ, Hewett TE, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Athl Train. 2018;53(1):5–19. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-99-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broglio SP, Cantu RC, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train. 2014;49(2):245–265. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.1.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonci CM, Bonci LJ, Granger LR, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: preventing, detecting, and managing disordered eating in athletes. J Athl Train. 2008;43(1):80–108. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casa DJ, Csillan D. Preseason heat-acclimatization guidelines for secondary school athletics. J Athl Train. 2009;44(3):332–333. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh KM, Cooper MA, Holle R, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: lightning safety for athletics and recreation. J Athl Train. 2013;48(2):258–270. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drezner JA, Courson RW, Roberts WO, Mosesso VN, Link MS, Maron BJ. Inter-Association Task Force recommendations on emergency preparedness and management of sudden cardiac arrest in high school and college athletic programs: a consensus statement. J Athl Train. 2007;42(1):143–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimenez CC, Corcoran MH, Crawley JT, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: management of the athlete with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Athl Train. 2007;42(4):536–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casa DJ, Almquist J, Anderson SA, et al. The Inter-Association Task Force For Preventing Sudden Death In Secondary School Athletics Programs: best-practices recommendations. J Athl Train. 2013;48(4):546–553. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman M, Bovbjerg V, Hannigan K, et al. Athletic Training and Public Health Summit. J Athl Train. 2016;51(7):576–580. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.6.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell SM, Barry AE, Pitney WA. Exploring the athletic trainer's role in assisting student-athletes presenting with alcohol-related unintentional injuries. J Athl Train. 2015;50(9):977–980. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.5.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinder SM, Basler RSW, Foley J, Scarlata C, Vasily DB. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: skin diseases. J Athl Train. 2010;45(4):411–428. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turocy PS, DePalma BF, Horswill CA, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: safe weight loss and maintenance practices in sport and exercise. J Athl Train. 2011;46(3):322–336. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould TE, Piland SG, Caswell SV, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: preventing and managing sport-related dental and oral injuries. J Athl Train. 2016;51(10):821–839. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.8.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pike AM, Pryor RR, Vandermark LW, Mazerolle SM, Casa DJ. Athletic trainer services in public and private secondary schools. J Athl Train. 2017;52(1):5–11. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pryor RR, Casa DJ, Vandermark LW, et al. Athletic training services in public secondary schools: a benchmark study. J Athl Train. 2015;50(2):156–162. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.2.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pike A, Pryor RR, Mazerolle SM, Stearns RL, Casa DJ. Athletic trainer services in US private secondary schools. J Athl Train. 2016;51(9):717–726. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr ZY, Lynall RC, Mauntel TC, Dompier TP. High school football injury rates and services by athletic trainer employment status. J Athl Train. 2016;51(1):70–73. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.3.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace J, Covassin T, Nogle S, Gould D, Kovan J. Knowledge of concussion and reporting behaviors in high school athletes with or without access to an athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2017;52(3):228–235. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kucera KL, Thomas LC, Cantu RC. National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research 34th Annual Report. National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research Web site. 2018 http://nccsir.unc.edu/reports Accessed April 5.

- 24.Former high school athlete wins $4.4 million settlement against negligent athletic trainers. Illinois Injury Lawyer Blog. Levin & Perconti Web site. 2012 https://www.illinoisinjurylawyerblog.com/2012/03/former_athlete_wins_44_million_1.html. Published March 16. Accessed April 5, 2018.

- 25.Catastrophic football injury leads to $8M settlement. Athletic Business Web site. 2018 https://www.athleticbusiness.com/civil-actions/catastrophic-football-injury-leads-to-8m-settlement.html#lightbox/0. Accessed April 5.

- 26.Athletic Training Locations and Services (ATLAS) Survey. Qualtrics Web site. 2018 https://uconn.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_enPMxrKzIqlYRnL Accessed June 21.

- 27.Carek PJ, Dunn J, Hawkins A. Health care coverage of high school athletics in South Carolina: does school size make a difference? J S C Med Assoc. 1999;95(11):420–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Post E, Winterstein AP, Hetzel SJ, Lutes B, McGuine TA. School and community socioeconomic status and access to athletic trainer services in Wisconsin secondary schools. J Athl Train. 2019;54(2):177–181. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-440-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider K, Meeteer W, Nolan JA, Campbell HD. Health care in high school athletics in West Virginia. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17(1):3879. doi: 10.22605/rrh3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazerolle SM, Raso SR, Pagnotta KD, Stearns RL, Casa DJ. Athletic directors' barriers to hiring athletic trainers in high schools. J Athl Train. 2015;50(10):1059–1068. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyznicki JM, Riggs JA, Champion HC. Certified athletic trainers in secondary schools: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. J Athl Train. 1999;34(3):272–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowe R, Pulice J. Mandating athletic trainers in high schools. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. 2009 https://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/mandating-athletic-trainers-in-high-schools.pdf. Published. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- 33.Vandermark LW, Pryor RR, Pike AM, Mazerolle SM, Casa DJ. Medical care in the secondary school setting: who is providing care in lieu of an athletic trainer? Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2017;9(2):89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dewitt TL, Unruh SA, Seshadri S. The level of medical services and secondary school-aged athletes. J Athl Train. 2012;47(1):91–95. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huggins RA, Olivadoti JA, Adams WM, et al. Presence of athletic trainers, emergency action plans, and emergency training at the time of sudden death in secondary school athletics [abstract] J Athl Train. 2017;52(suppl 6):S79. [Google Scholar]