Abstract

Background:

The U.S. Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) was a landmark federal policy aimed at increasing access to substance use treatment, yet studies have found relatively weak impacts on treatment utilization. The present study considers whether there may be moderating effects of pre-existing state parity laws and differential changes in treatment rates across racial/ethnic groups.

Methods:

We analyzed data from SAMSHA’S Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) from 1999–2013, assessing changes in alcohol treatment admission rates across states with heterogeneous, pre-existing parity laws. NIAAA’s Alcohol Policy Information System data were used to code states into five groups based on the presence and strength of states’ pre-MHPAEA mandates for insurance coverage of alcohol treatment and parity (weak; coverage no parity; partial parity if coverage offered; coverage and partial parity; strong). Regression models included state fixed effects and a cubic time trend adjusting for state- and year-level covariates, and assessed MHPAEA main effects and interactions with state parity laws in the overall sample and racial/ethnic subgroups.

Results:

While we found no significant main effects of federal parity on alcohol treatment rates, there was a significantly greater increase in treatment rates in states requiring health plans to cover alcohol treatment and having some pre-existing parity. This was seen overall and in all three racial/ethnic groups (increasing by 25% in whites, 26% in blacks, and 42% in Hispanics above the expected treatment rate for these groups). Post-MHPAEA, the alcohol treatment admissions rate in these states rose to the level of states with the strongest pre-existing parity laws.

Conclusion:

The MHPAEA was associated with increased alcohol treatment rates for diverse racial/ethnic groups in states with both alcohol treatment coverage mandates and some prior parity protections. This suggests the importance of the local policy context in understanding early effects of the MHPAEA.

Keywords: Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, alcohol treatment, substance use disorder treatment, health disparities, alcohol policy environment

1. Introduction

By removing unfair restrictions on insurance coverage of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) has the potential to significantly increase treatment utilization and help reduce the vast U.S. treatment gap whereby one out 10 Americans with an SUD receives specialty treatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & Office of the Surgeon General, 2016). An extension of the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, the MHPAEA applied parity to SUDs and broadened the scope of parity to include other financial requirements (e.g., deductibles, co-pays, co-insurance), duration of care (e.g., frequency of treatment, number of visits), and management of health services (e.g., prior authorizations) (Herrera, Hargraves, & Stanton, 2013). Recent studies indicate that the MHPAEA has led to the removal of limits on behavioral health visits and episodes of care (Horgan et al., 2016; Thalmayer, Friedman, Azocar, Harwood, & Ettner, 2017), and some reductions in patient cost-sharing (Ettner et al., 2016; S. A. Friedman, Thalmayer, et al., 2018; Harwood et al., 2017). But while such changes might be expected to increase treatment use, the MHPAEA appears to have had modest effects on behavioral health care utilization at best. Moreover, very little is known about the MHPAEA’s effects on SUD treatment specifically.

In the relatively small literature evaluating the MHPAEA, studies have tended to focus on spending outcomes and have commonly analyzed behavioral health care as a whole without distinguishing SUD and mental health. In two studies of patients with SUDs, Friedman et al. (2017) observed a modest increase in behavioral health care plan spending generally; a subsequent study that parsed out SUD spending found lower patient cost-sharing for detox services through reduced co-pays, which were partly offset by simultaneous increases in co-insurance (S. A. Friedman, Azocar, Xu, & Ettner, 2018). Drilling down further, a rare study differentiating alcohol and illicit drug treatment showed that Oregon’s parity law led to increased plan spending for alcohol, but not for illicit drug treatment nor for SUD services overall (McConnell, Ridgely, & McCarty, 2012).

In general, the few utilization studies suggest that the MHPAEA has had mixed effects. For example, some studies based on insurance claims have found a greater percentage of plan enrollees using behavioral health services following the MHPAEA (Harwood et al., 2017; Mark, Hodgkin, Levit, & Thomas, 2016) as well as increased behavioral health visits by service users (Harwood et al., 2017). However, other analyses of claims data suggest that the probability of utilizing behavioral health care may have changed little based on findings from interrupted time series and difference-in-differences analyses (Ettner et al., 2016). This raises the question of whether the MHPAEA might have been more successful at increasing behavioral health care utilization by existing service users rather than treatment entry. Research focused on SUD treatment appears to support this possibility. When accounting for secular trends, Busch and colleagues’ (2014) study of claims data in 2010 (vs. 2009) found no change in the probability of engaging in SUD treatment, and McGinty, Busch et. al. (2015) observed increased utilization among existing SUD service users; specifically, a 4.3 percent increase above the expected probability of out-of-network treatment, and higher mean visits per treatment user.

In view of the sparse research investigating the MHPAEA’s impact on SUD treatment entry, we examined whether treatment admissions rates have increased following implementation of the federal parity law. Our analysis focused on alcohol-related treatment, as prior research suggests that parity laws can affect alcohol and illicit drug treatment utilization differently and because alcohol use disorders are common, affecting an estimated 16.3 million Americans in 2014, and 8 out of every 10 persons with a substance use disorder (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017). Excessive drinking has been found to be the third leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). Our analysis also recognizes that passage of the MHPAEA occurred during the Great Recession, whose effects could influence treatment utilization. The recession was associated with the loss of health insurance, increased heavy drinking and alcohol problems (Bor, Basu, Coutts, McKee, & Stuckler, 2013; Mulia, Zemore, Murphy, Liu, & Catalano, 2014) as well as reduced outpatient treatment among nonprofit providers (Cantor, Stoller, & Saloner, 2017) and is a potentially important confounder to account for.

The major focus of our study is on the potential moderating effects of state parity laws that existed prior to the MHPAEA and which have received relatively little attention. Indeed, it is possible that prior studies show modest impacts of the MHPAEA because many states already had parity mandates. Following passage of the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, the majority of U.S. states had behavioral health parity laws but these varied considerably in scope and applicability to SUDs, resulting in a patchwork of state parity regulations across the country (Peterson & Busch, 2018). Coverage for alcohol and illicit drugs also varied across states. A Blue Cross Blue Shield report from 1999 indicates that while 44 states mandated benefits for alcoholism treatment, only 31 states had drug abuse coverage requirements (Barry & Sindelar, 2007). When they did exist, SUD mandates were typically more restrictive than mental health parity rules. For example, in one state parity applied to SUDs only given the presence of a co-occurring mental health condition (Barry & Sindelar, 2007).

Nonetheless, studies based on SAMHSA’s administrative treatment data have found that state parity laws led to greater SUD treatment admissions, particularly in states with comprehensive parity mandates (Dave & Mukerjee, 2011; Wen, Cummings, Hockenberry, Gaydos, & Druss, 2013). Building on these findings for state parity laws, our study assessed differential impacts of the MHPAEA across states with different parity mandates for alcohol treatment. We identified states with “weak” or non-existent laws that should benefit minimally, if at all, from the MHPAEA and which could serve as a comparison group when analyzing the federal law’s effects. Compared to these states, we hypothesized that states mandating health plan coverage of alcohol treatment services but with no pre-existing parity laws would show the largest increase in alcohol treatment admissions post-MHPAEA.

A second key question we address in this study relates to potential racial/ethnic differences in the effects of the MHPAEA. Growing evidence suggests that broad-based public health interventions can lead to positive population health outcomes while also introducing or exacerbating health inequities (Benach, Malmusi, Yasui, Martínez, & Muntaner, 2011; Lorenc, Petticrew, Welch, & Tugwell, 2013; Mulia & Jones-Webb, 2017); for instance, if an intervention benefits only some population groups, or some more than others. Initially, the MHPAEA applied only to employer-sponsored health insurance as it was only in 2013 that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced that the law would apply to Medicaid managed care plans (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2013; Mann, 2013). In view of racial/ethnic differences in insurance coverage (Brown, Ojeda, Wyn, & Levin, 2000; DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2007; Doty, 2003), we tentatively hypothesized that whites would show a greater increase in alcohol treatment admissions in the early years post-MHPAEA compared to blacks and Hispanics. This possibility is concerning because it could have the unintended consequence of widening disparities in alcohol-related problems (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Delker, Brown,& Hasin, 2016; Mulia, Ye, Greenfield, & Zemore, 2009; Zapolski, Pedersen, McCarthy, & Smith, 2014), as well as disparities in treatment utilization (Cook & Alegría, 2011; Mulia, Tam, & Schmidt, 2014; Schmidt, 2016; Schmidt, Ye, Greenfield, & Bond, 2007; Zemore et al., 2014). Thus, we examined changes in alcohol treatment admission rates associated with the MHPAEA in the U.S. overall, and in the nation’s three largest racial/ethnic groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Sample

We analyzed treatment admissions data over the 15-year period from 1999 through 2013 obtained from SAMSHA’s Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS-A), an administrative database of almost 2 million admissions annually to specialty SUD treatment providers in the U.S. TEDS data represent all public and private treatment facilities that are licensed or certified by a state’s substance abuse agency and receiving at least some public funding (including state agency funding or federal block grants); an estimated 81% of all SUD treatment admissions in the U.S. occur within such facilities (Dave & Mukerjee, 2011). Demographic characteristics of the TEDS admissions sample have been found comparable to a nationally representative sample of individuals self-reporting SUD treatment receipt in the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (Gfroerer et al., 2013). The current analytic sample consisted of a panel of 690 state-year observations across 45 states and the District of Columbia over this 15-year study period. Four states (Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Nevada) were excluded from this analysis because they changed their alcohol-related insurance and parity mandates around the time of the MHPAEA, making it difficult to assess the impact of federal parity. According to NIAAA’s Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS, described below), Alaska, Arkansas and Nevada eliminated state laws requiring health plans to cover or offer coverage for alcohol treatment, and Colorado greatly strengthened its alcohol treatment coverage and parity mandates. Mississippi was also excluded from this analysis due to considerable missing data in the post-MHPAEA period.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome—Alcohol Treatment Admissions Rate

This was estimated using annual, state- and race/ethnicity-specific treatment admission counts from 1999–2013 for clients aged 15 and older who reported alcohol as a primary, secondary, or tertiary substance of abuse leading to treatment. While we could have chosen to restrict the outcome to primary alcohol admissions, which account for approximately two-thirds of the total alcohol-related admissions throughout the study period (with a range from 68% in 1999 to 69% in 2013, and a low point of 65% in 2005), we instead chose to include admissions where alcohol is listed as a secondary or tertiary substance in recognition of very high levels of comorbid alcohol disorder among persons with drug disorders, and national data showing the large majority of persons with drug and alcohol comorbidity seek treatment for alcohol disorder only, or both alcohol and drug disorders (Stinson et al., 2005). Total alcohol admissions were aggregated to the state-level. To calculate the overall treatment rate per 10,000 population, we used the state population aged 15+ from the Census/American Community Survey for the corresponding year from 1999–2013 (Census 2000 was used to calculate 1999 treatment rates). The same procedure was used to calculate race-specific treatment rates based on TEDS self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic) and Census data on race- and state-specific population size.

2.2.2. MHPAEA Policy Indicator and States’ Pre-Existing Parity Laws (PEP)

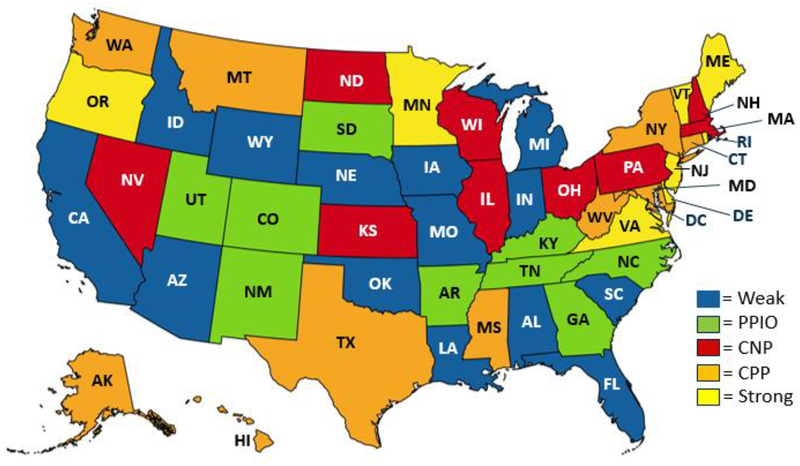

The MHPAEA went into effect for health plans starting on or after July 2010. As many health plans begin in January, we defined 2011–2013 as the post-policy period consistent with other studies (e.g., Ettner et al., 2016; S. Friedman et al., 2017; Thalmayer et al., 2017); sensitivity analyses using 2010–2013 showed similar results (data not shown). NIAAA’s Alcohol Policy and Information System (APIS) data were used to code states according to the presence or absence of mandates related to parity for alcohol treatment prior to the MHPAEA. For the large majority of states, pre-existing parity (PEP) policies were in place by 2003, with only a few states subsequently changing policies prior to the MHPAEA; for example, Delaware went from no law to strong parity laws in 2005, and Oregon strengthened their laws in 2007 by adding parity in service and financial limits to existing parity requirements for deductibles, co-insurance and co-pays. The APIS database includes state-by-year data indicating whether the state required health plans to cover or offer coverage for alcohol treatment, along with any of 4 types of parity for alcohol-related services. The latter include parity in deductibles; co-pays and co-insurance; service limits; and financial limits. Based on these laws, we coded states as: 1) weak; 2) coverage no parity; 3) partial parity if offered; 4) coverage and partial parity; or 5) strong (see Figure 1 for a map of states as coded). Weak states had no alcohol treatment coverage mandate and no alcohol parity requirements (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wyoming); these were expected to show minimal change, if any, following the MHPAEA. Coverage-no-parity (CNP) states were those that mandated plan coverage of alcohol treatment but without any parity requirements and were hypothesized to benefit the most from the MHPAEA (Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin). Partial-parity-if-offered (PPIO), a term coined by Wen et al. (2013), refers to states that required health plans to offer alcohol treatment coverage and when provided, required at least one but not all 4 types of parity (Georgia, Kentucky, New Mexico, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Utah). Coverage-and-partial-parity (CPP) states mandated coverage of alcohol treatment and required at least one but not all types of parity (Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, Montana, New York, Texas, Washington, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia). Strong states mandated alcohol treatment coverage as well as all 4 types of parity (Delaware, Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia). Note that although they already had comprehensive parity requirements for quantitative treatment limitations, strong states could still potentially benefit from federal parity requirements concerning non-quantitative treatment limitations (e.g., related to pre-authorization, medical management) and applicability of the MHPAEA to large, self-insured firms that were previously exempt from state parity mandates.

Figure 1.

State Heterogeneity in Parity Laws for Alcohol Treatment Prior to the MHPAEA

Notes: States were coded based on NIAAA’s Alcohol Policy Information System data on mandates related to health plan coverage of alcohol treatment and presence of different types of parity requirements for alcohol treatment (0–4), including deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance, service limits, and financial limits. States were categorized as: 1) Weak = no required coverage or parity; 2) PPIO, Partial parity if offered (coverage must be offered and one or some parity requirements apply; 3) CNP, coverage no parity (coverage is mandated, there are no parity requirements); 4) CPP, coverage and partial parity (coverage is mandated with some parity); 5) Strong (coverage and all 4 types of parity are required).

2.2.3. State- and Year-level Covariates

Models controlled for state- and year-level variables, including unemployment rate, percent living in poverty, and percent uninsured, available from the Health Resources & Services Administration's Area Health Resource File (AHRF).1 These are potentially important confounders, given the Great Recession and variation in the severity and timing of macroeconomic impacts across states. We also controlled for states’ annual alcohol dependence rates obtained from publicly available tables based on the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, and used here as an indicator of the state’s level of need for alcohol treatment. We also adjusted for the number of treatment facilities accepting private insurance per 10,000 state residents, available from SAMSHA’s N-SSATS (an annual census of U.S. public and private substance abuse treatment facilities). In sensitivity analyses of Hispanic treatment admissions, we further adjusted for number of facilities providing treatment in Spanish per 10,000 Hispanic residents. Preliminary descriptive analyses also examined PEP differences in urbanicity (percent of state residents in urban areas in 2010, from the AHRF) and state treatment funding per capita based on treatment expenditure data reported by states (see Table 2 in (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2006).

Table 2.

Effects of MPHAEA on Alcohol Treatment Admission Rates by Pre-existing Parity Policy: Overall and By Race/Ethnicity

| Total Sample (n=676) |

White Sample (n=676) |

Black Sample (n=676) |

Hispanic Sample (n=657) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | p | SE | Coef | p | SE | Coef | p | SE | Coef | p | SE | |

| Post-MHPAEA period Interaction with Pre-existing Parity (Ref: Weak) | −0.015 | 0.069 | −0.017 | 0.072 | −0.020 | 0.082 | −0.202 | 0.140 | ||||

| PPIO*MHPAEA | 0.184 | 0.099 | 0.139 | 0.102 | 0.101 | 0.113 | 0.458 | * | 0.200 | |||

| CNP*MHPAEA | −0.068 | 0.096 | −0.049 | 0.100 | −0.082 | 0.110 | 0.028 | 0.194 | ||||

| CPP*MHPAEA | 0.270 | ** | 0.094 | 0.236 | * | 0.097 | 0.248 | * | 0.107 | 0.552 | ** | 0.190 |

| Strong*MHPAEA | 0.077 | 0.096 | 0.097 | 0.099 | 0.044 | 0.110 | 0.262 | 0.193 | ||||

| State-level Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Unemployment rate | 0.022 | * | 0.010 | 0.024 | * | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.021 | ||

| % Uninsured | −0.034 | ** | 0.013 | −0.037 | ** | 0.013 | −0.036 | * | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.026 | |

| % Living in poverty | 0.037 | * | 0.018 | 0.039 | * | 0.018 | 0.050 | * | 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.036 | |

| Alcohol dependence rate | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.016 | 0.030 | −0.006 | 0.035 | 0.020 | 0.059 | ||||

| Treatment facilities accepting private insurance (per 10,000 residents) | −0.327 | 0.256 | −0.311 | 0.266 | −0.133 | 0.297 | 0.706 | 0.519 | ||||

| Constant | 3.363 | 0.331 | 3.103 | 0.341 | 3.800 | 0.373 | 1.426 | 0.706 | ||||

Notes. n= number of state-year observations. Results are from the overall sample and race-stratified models. All models estimated with generalized least squares accounting for autocorrelation, time trend with linear, quadratic and cubic terms, and state fixed effects.

p<0.05,

p<0.01

2.3. Data analysis

Analysis was conducted using panel data with 690 state-year observations across 45 states plus the District of Columbia and 15 years. We began with descriptive analyses of trends in overall treatment admission rates for the total sample and for whites, blacks, and Hispanics separately across the study period, 1999–2013. We also conducted bivariate analysis to compare state characteristics according to PEP groupings. We used generalized least squares (GLS) to fit the panel data across time. GLS estimates a model while capturing autocorrelation within states and cross-sectional correlation and heteroscedasticity across states (StataCorp., 2017). Given considerable variation in state treatment rates that results in a skewed distribution, and to address heteroscedasticity, we modelled the outcome as logged treatment admission rates consistent with other studies (e.g., Wen et al., 2013).

We estimated the following GLS model to assess the overall effect of the federal parity law across all states, captured by P:

where Yst is the treatment admission rate at state s in year t. Time is modeled by linear, t, quadratic, t2, and cubic, t3, terms. (The cubic term captures a second downward trend observed in treatment rates in the late 2000s.) State fixed effects, Ss, are included to account for state differences in unobserved, time-invariant factors; sensitivity analyses further examined state-specific linear time trends to account for unobserved within-state, time-varying factors such as treatment spending per capita, which could vary across states depending upon the severity of the recession’s impact on state budgets. State-level, time-varying covariates described above, Cst, are included as controls. P is the policy indicator, modelled as the post-MHPAEA period (2011–2013). PEP refers to the 5-category grouping of states based on the pre-MHPAEA treatment coverage and parity laws.

To assess whether the MHPAEA’s impact differed according to these state laws, we tested the interaction of the MHPAEA indicator, P, and states’ pre-existing parity policy, PEP:

Here P estimates the effect of the MHPAEA in weak PEP states, which were the referent. These weak states comprise a natural comparison group because these were the only states with neither mandates for alcohol treatment coverage nor parity, and federal parity is moot in the absence of treatment coverage. Regression analyses of trends in alcohol treatment rates in the pre-MHPAEA period (1999–2010) found no significant interactions of PEP with linear, quadratic and cubic time. This indicates that temporal trends before the MHPAEA’s implementation did not differ significantly between weak states (the referent) and any of the 4 groups of comparison states with differing parity laws. Models were run for the overall sample and race-stratified samples. To facilitate interpretation of the interaction of the MHPAEA indicator with states’ pre-existing parity laws, we plotted the predicted alcohol treatment admission rates.

3. Results

3.1. Trends in Alcohol Treatment Rates and Characteristics of PEP States

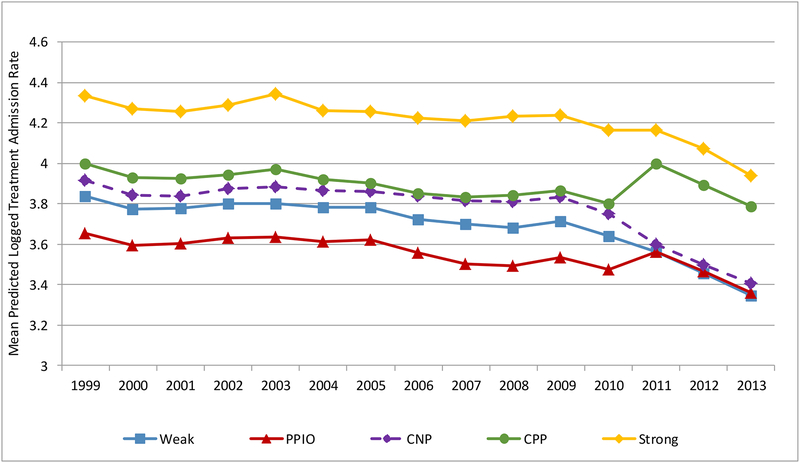

Alcohol treatment admission rates have generally been declining since 1999, particularly following the Great Recession of 2008–2009. Figure 2 presents alcohol treatment rates for U.S. states overall and by states’ pre-existing parity (PEP) policies. As expected, strong states (with mandated alcohol treatment coverage and all 4 parity laws prior to the MHPAEA) had generally the highest alcohol treatment admission rates across the 15-year period, followed by CPP states (mandating coverage and partial parity). Weak states (no coverage and no parity mandates) and CNP states (mandated coverage but no parity laws) were roughly similar in treatment rates over this period. Treatment admission trends in PPIO states (partial parity if coverage is offered) were not significantly different from those in weak and CNP states, but diverged and increased after 2004–2005.

Figure 2.

Average Alcohol Treatment Admission Rates by Pre-Existing Parity Policy, U.S. States n=46

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics of states by PEP groupings. CPP, PPIO, and weak states were more racially/ethnically diverse than strong and CNP states, and also had greater unemployment, poverty, and larger uninsured populations, on average, over the study period. Notably, across all PEP groups there was a considerable rise in average unemployment and poverty rates beyond the Great Recession and into the post-MHPAEA period. Strong PEP states, followed by CNP states, had the greatest supply of treatment facilities accepting private insurance over the study period, while weak states had the fewest facilities; in fiscal year 2003, strong PEP states also had the highest treatment expenditures per capita, followed by CPP states.

Table 1.

State Characteristics by Pre-Existing Parity Policy

| STATE PARITY POLICY PRIOR TO MHPAEA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weak (n=14) |

PPIO (n=7) |

CNP (n=8) |

CPP (n=9) |

Strong (n=8) |

p-value | |

| Alcohol treatment admission rates (per 10,000 population) 1999–2013 | ||||||

| Total Sample | 47.6 | 50.1 | 46.9 | 66.1 | 75.0 | *** |

| White | 42.7 | 36.6 | 40.7 | 52.8 | 69.6 | *** |

| Black | 99.2 | 128.3 | 102.2 | 136.9 | 174.6 | *** |

| Hispanic | 53.9 | 58.4 | 56.0 | 78.6 | 86.8 | *** |

| Unemployment rate | ||||||

| 1999–2013 | 5.86 | 5.78 | 5.42 | 5.88 | 5.62 | NS |

| 1999–2010 | 5.48 | 5.35 | 5.11 | 5.49 | 5.19 | |

| 2008–2009 | 7.11 | 6.84 | 6.40 | 6.48 | 7.08 | |

| 2011–2013 | 7.40 | 7.49 | 6.67 | 7.41 | 7.35 | |

| % Living in poverty | ||||||

| 1999–2013 | 13.9 | 15.0 | 11.1 | 13.4 | 10.9 | *** |

| 1999–2010 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 10.6 | 13.0 | 10.4 | |

| 2008–2009 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 11.2 | |

| 2011–2013 | 16.4 | 17.4 | 13.0 | 14.8 | 13.1 | |

| % Uninsured | ||||||

| 2005–2013 | 20.3 | 20.8 | 14.2 | 18.0 | 15.5 | *** |

| Alcohol dependence rate | ||||||

| 1999–2013 | 3.21 | 3.10 | 3.22 | 3.33 | 3.19 | * |

| % Hispanic population aged 15+ | ||||||

| 1999–2013 | 10.2 | 11.3 | 6.1 | 11.2 | 7.2 | *** |

| % Black population aged 15+ | ||||||

| 1999–2013 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 7.1 | 14.1 | 8.2 | *** |

| SUD Tx facilities accepting private insurance (per 10,000 state residents) | ||||||

| 1999–2013 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.60 | *** |

| 1999–2010 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.59 | |

| 2011–2013 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.63 | |

| Urbanicity | 73.6 | 70.1 | 75.2 | 80.9 | 72.0 | NS |

| FY 2003 Treatment spending per capita aged 15+ ($) | 13.90 | 11.15 | 14.01 | 21.36 | 41.00 | NS |

Notes. As described in the text, data sources include the SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set, NIAAA Alcohol Policy Information System, Census/ACS data, HRSA Area Health Resources Files, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, and the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Policy categories: Weak (Plans are not required to cover alcohol treatment for enrollees; no parity laws exist); Coverage No Parity (CNP; Plans must cover alcohol treatment but there are no parity requirements); Partial Parity if Offered (PPIO; Plans must offer alcohol treatment coverage to enrollees; if covered, some parity rules apply); CPP (Plans must cover alcohol treatment and some parity rules apply); Strong (Alcohol treatment coverage is mandated along with all 4 types of parity).

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001;

NS=not significant

3.2. Multivariable Results

Main effects models (not shown) which adjust for secular trends showed no significant change in the alcohol treatment admissions rate associated with the MHPAEA, neither overall (β= 0.068, 95% CI= −0.025, 0.162) nor for any of the three racial/ethnic groups examined separately (βwh = 0.062, 95% CIwh = −0.037, 0.161; βbl = 0.061, 95% CIbl = −0.053, 0.176; βhi = −0.015, 95% CIhi = −0.171, 0.202); results were also non-significant in fully adjusted main effects models. We next assessed differential changes in treatment admissions across states by examining the interaction of the MHPAEA policy indicator with states’ pre-existing parity (PEP) policies. Table 2 shows results from fully-adjusted models on overall alcohol treatment admission rates. Weak PEP states (the referent, with no mandates for alcohol treatment coverage) had a 1.5% decrease in the alcohol treatment rate post-MHPAEA, which was not significantly different from the pre-MHPAEA treatment rate in these states, accounting for temporal trends. CNP, PPIO and strong states were not significantly different from weak states in their post-MHPAEA change in treatment admissions. CPP states (mandating coverage and partial parity) were the only group to experience a change in alcohol admissions post-MHPAEA that was significantly different from weak states, as indicated by a positive interaction term (0.270, p<.01) which translates into a 29% increase in CPP states’ treatment admissions rate post-MHPAEA [exp(0.270−0.015) − 1]. These results held up in sensitivity analyses adjusting for state-specific linear time trends to account for unobserved differences in time-varying, state-level factors. Figure 3a plots the interaction to show the predicted logged treatment rates over time, and Figure 3b focuses further on the different trends in weak, CPP and strong states (shown from 2007 to 2013). It shows that during the pre-MHPAEA period, CPP and weak states had similar alcohol treatment admission rates, both of which were lower than those in strong states. After the MHPAEA, the treatment admissions rate in CPP states diverged from weak states, rising to become statistically indistinguishable from states with strong pre-existing parity.

Figure 3a.

Predicted Trends in Alcohol Treatment Admission Rates Before and After the MHPAEA by Pre-Existing Parity Policy, U.S. States n=46

Figure 3b.

Subset of Total Predicted Trends in Alcohol Treatment Admission Rates Before and After the MHPAEA by Pre-Existing Parity Policy, U.S. States n=46

Estimates from race-stratified models are also shown in Table 2. For each racial/ethnic group, CPP states showed a significant increase in alcohol treatment admission rates post-MHPAEA: whites increased by an estimated 24.5% (95% CI = 5.4% - 47.1%), blacks by 25.6% (4.2% - 51.5%) and Hispanics by 41.9% (2.3% - 96.9%) over their expected treatment admission rate had there been no federal parity law. Among Hispanics there was also a significant interaction suggesting an increase in treatment admissions in PPIO (partial-parity-if-offered) states (β =.458, p<.05), but this did not hold up in sensitivity analyses accounting for unobserved differences in time-varying, state factors (β =.205, p=.318). By contrast, sensitivity analyses revealed robust results for increased alcohol treatment rates in CPP (vs. weak) states; coefficients in final, race-stratified models were .24, .25, .55 for whites, blacks and Hispanics, respectively, and .31, .27, and .57 in corresponding sensitivity analyses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Moderating Effects of Pre-existing State Parity Laws

Prior research suggests that the federal parity law has had a generally weak effect on increasing treatment admissions but has not considered whether pre-existing state parity laws might have biased results towards the null and whether a focus on main effects might be masking important changes in treatment admissions in select states and population subgroups. The present study indicates that CPP states (which mandated health plan coverage of alcohol treatment and partial parity prior to the MHPAEA) were the only group to experience a significant increase in alcohol treatment admissions post-MHPAEA. This finding was obscured in our main effects models which showed no significant overall impact on the national alcohol treatment admission rate associated with the MHPAEA, neither in overall treatment rates nor race/ethnicity-specific rates. The latter is consistent with prior reports of weak or no increased probability of behavioral health services utilization post-MHPAEA (e.g., Busch et al., 2014; Ettner et al., 2016; S. A. Friedman, Azocar, et al., 2018).

Contrary to expectations, CNP states showed no significant change in alcohol treatment rates. Because CNP states mandated alcohol treatment coverage (similar to CPP states) but without any parity laws, we expected these states to show the largest gain in alcohol treatment admissions. The null finding for CNP states raises the question of whether CPP states were able to implement or capitalize upon federal parity regulations more rapidly than CNP states. For instance, it may be that CPP states’ existing commitment to alcohol treatment parity could have primed insurers, employers, treatment providers and possibly even consumers for the new federal parity rules. Moreover, prior experience with implementing parity could have helped to expedite administrative processes on the part of insurers and treatment providers to change SUD treatment limits, patient costs, and treatment access procedures. Future research should endeavor to understand factors that might shed light on the differential policy effects seen across states that mandated treatment coverage but differed in the existence of prior parity.

Our null findings for strong PEP states and PPIO states were not greatly surprising. Strong PEP states required plan coverage of alcohol treatment and had the most comprehensive pre-MHPAEA parity mandates applied to deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance, service limits and financial limits. While the federal law introduced new parity requirements for non-quantitative treatment limitations, there are indications that these may have been less widely implemented due to more uncertainty in how to apply parity (Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity Task Force, 2016), thus possibly accounting for the absence of a policy impact. With regard to PPIO states, we tentatively expected that these would show some increase in treatment rates but that it would be smaller in magnitude compared to CPP states because PPIO states only require health plans to offer the option of coverage. The finding of largely null effects for PPIO, and no significant effect at all in sensitivity analyses, was therefore not greatly surprising. These differential effects seen for PPIO and CPP states further highlight the significance of coverage mandates for alcohol treatment.

It is important to note that strong states’ pre-existing mandates capture key, SUD-related provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Thus, the fact that strong states showed the highest treatment rates across the study period, and were joined by CPP states after the MHPAEA, signals the promise of improved treatment access through the ACA’s provision that SUD treatment be covered as an essential health benefit and its extension of MHPAEA protections to more Americans. Studies of treatment are just beginning to show evidence that the ACA has had an impact on treatment access, particularly access to specialty substance use treatment and medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder through Medicaid expansion (Andrews et al., 2019; Mojtabai, Mauro, Wall, Barry, & Olfson, 2019, in press; Sharp et al., 2018). Research is needed to examine impacts on alcohol and other drug treatment.

4.2. Racial/ethnic Differences in Alcohol Treatment Admission Rates after the MHPAEA

In our race-stratified analysis of the MHPAEA’s effects on alcohol treatment admissions, we again found significant increases in treatment rates only in CPP states, and these were of roughly similar magnitude in whites, blacks and Latinos. The CPP findings in the total sample were thus robust across racial/ethnic subgroups, and our expectation that whites would benefit most from the MHPAEA was not supported. Several possible factors might account for this. First, rising unemployment rates during the Great Recession led to particularly large losses of health insurance among whites, especially white men (Cawley, Moriya, & Simon, 2015; Holahan, 2011). Unemployment and uninsured rates remained high throughout the post-MHPAEA period analyzed here (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019) and thus could have offset effects of the MHPAEA, and led to a smaller than expected change in whites’ alcohol treatment admission rates. Second, it is possible that for those who retained health insurance throughout, federal parity could have encouraged treatment-seeking from different providers, such as private providers who operate without public funding and are not represented in this study. If so, this would be similar to the findings reported by McGinty et al. (2015) that the MHPAEA led to greater out-of-network provider visits for substance use treatment services. Third, temporal changes in U.S. substance use patterns might also play a role, particularly decreases in alcohol use disorder prevalence (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017) and the sharp increase in opioid use disorders which were notable among whites (Case & Deaton, 2015). These trends in prevalence have been mirrored by declining alcohol treatment admissions and rising drug-only admissions since 2008 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). While our analysis adjusted for state- and year-level alcohol dependence prevalence, whites are over-represented in and account for the large majority of alcohol-only treatment admissions (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). These various factors could have had a pronounced impact on white alcohol admission rates post-MHPAEA. Further, the slow economic recovery and rise of the opioid epidemic might help to explain the lack of a greater overall impact of the MHPAEA on alcohol treatment rates in the total population.

The findings from our race-stratified analyses have implications for treatment access by diverse groups under the ACA. Studies have shown that ACA-related gains in insurance coverage were particularly pronounced for blacks and Latinos, and that racial/ethnic disparities in coverage have declined as a result (Buchmueller, Levinson, Levy, & Wolfe, 2016; McMorrow, Long, Kenney, & Anderson, 2015). In light of this, and the ACA’s coverage of SUD treatment and parity protections, our findings bode well for more equitable access to alcohol and other SUD treatment under the ACA. Future research should investigate whether this bears out.

4.3. Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. First, it is possible that our analysis has yielded conservative estimates of change in alcohol treatment admission rates associated with the MHPAEA, as TEDS data include uninsured and publicly insured admissions which were not targeted by the MHPAEA and which account for a large majority of treatment admissions in the U.S. Supporting this possibility, Wen et al.’s (2013) analysis of SAMHSA’s facilities-level data found that the effect of state parity laws on SUD treatment admissions was greater when analyses were restricted to treatment facilities accepting private insurance (as well as other types of insurance). Additionally, as noted in section 2.1 above, the TEDS data are collected from publicly funded, specialty treatment providers that are licensed or certified by the state, and therefore might not capture non-specialty treatment services received elsewhere, such as from private practitioners and physicians. As Saloner and colleagues (2018) point out, there are indications that treatment-seeking from the latter may be growing; for instance, the share of U.S. SUD spending for specialty treatment providers has decreased from 89% to 80% between 1998 and 2014, overlapping with a period of dramatic growth in spending on SUD medication (see Table A.6 and Exhibits 29–31 in (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016). However, this might reflect the integration of opioid treatment more than alcohol treatment in medical settings; primary care-based buprenorphine prescriptions have risen greatly since 2006 (Wen, Borders, & Cummings, 2019) in contrast to physician uptake of alcohol pharmacotherapy and brief alcohol interventions which has been slow (Glass, Bohnert, & Brown, 2016; Mark, Kassed, Vandivort-Warren, Levit, & Kranzler, 2009). It is important to emphasize that our findings are consistent with studies of private insurance claims data indicating very modest to null effects of the MHPAEA on treatment entry. Finally, there may be data reporting differences across states that reflect differences in state licensure and certification, as well as differences in coding of substances of abuse at admission (e.g., a tendency to code primary substances but not secondary or tertiary substances). Caution must therefore be used in making cross-state comparisons based on TEDS data (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2011). To address such concerns, our analysis used state fixed effects to approximate within-state changes in alcohol treatment rates pre- and post-MHPAEA, and also adjusted for state-specific linear time trends in sensitivity analyses to account for confounding due to any unobserved state-level, time-varying factors such as differences related to state reporting and coding.

4.4. Conclusion

The current study contributes to the sparse literature on the MHPAEA’s effects on access to SUD treatment by investigating whether and how pre-existing state parity laws moderate effects of the federal law, and whether diverse racial/ethnic groups are benefitting from federal parity protections. Our finding of significantly increased alcohol treatment rates in states with coverage mandates and partial (pre-existing) parity was observed overall and in diverse racial/ethnic groups. This suggests that the prior existence of parity in states might have facilitated implementation of the federal policy, enabling states to reap benefits of the MHPAEA earlier than other states. It further suggests that the pairing of comprehensive parity protections with SUD treatment coverage mandates, as laid forth by the ACA, may be a powerful strategy for increasing treatment admissions. Taken as a whole, the current findings hint at the public health setback that could result from dismantling ACA provisions that facilitate access to care for SUD. Future research should examine the ACA’s impact on alcohol and other drug treatment and across racial/ethnic groups. The latter will be essential to ensuring that landmark federal health care policies are advancing progress towards health equity in the US.

Highlights.

No significant change was found in the national alcohol treatment admission rate.

States mandating treatment coverage and some parity increased rates post-MHPAEA.

In these states, treatment rates increased in all three racial/ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P50AA005595).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: none.

Data on the % uninsured were available for 2005–2013. We used the 2005 value for 1999–2004, and conducted analyses limiting the study period to 2005–2013; compared to analyses using all years 1999–2013, results were similar.

References

- Andrews CM, Pollack HA, Abraham AJ, Grogan CM, Bersamira CS, D’Aunno T, & Friedmann PD (2019). Medicaid coverage in substance use disorder treatment after the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 102, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, & Sindelar JL (2007). Equity in private insurance coverage for substance abuse: a perspective on parity. Health Affairs (Millwood), 26(Supp 2), w706–w716. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.w706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benach J, Malmusi D, Yasui Y, Martínez JM, & Muntaner C (2011). Beyond Rose’s strategies: a typology of scenarios of policy impact on population health and health inequalities. International Journal of Health Services, 41(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor J, Basu S, Coutts A, McKee M, & Stuckler D (2013). Alcohol use during the great recession of 2008–2009. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 48(3), 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ER, Ojeda VD, Wyn R, & Levin R (2000). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Health Insurance and Health Care [Accessed: 2014-11-24. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6UKmqPEej] (pp. 86). Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller TC, Levinson ZM, Levy HG, & Wolfe BL (2016). Effect of the Affordable Care Act on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1416–1421. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SH, Epstein AJ, Harhay MO, Fiellin DA, Un H, Leader D Jr., & Barry CL (2014). The effects of federal parity on substance use disorder treatment. The American Journal of Managed Care, 20(1), 76–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J, Stoller KB, & Saloner B (2017). The response of substance use disorder treatment providers to changes in macroeconomic conditions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 81, 59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, & Deaton A (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(49), 15078–15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J, Moriya AS, & Simon K (2015). The impact of the macroeconomy on the health insurance coverage: evidence from the great recession. Health Economics, 24(2), 206–223. doi: 10.1002/hec.3011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act [Accessed: 2014-07-28. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6RPlO4rGI]. Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research and Health, 33(1–2), 152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, & Alegría M (2011). Racial-ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment: the role of criminal history and socioeconomic status. Psychiatric Services, 62(11), 1273–1281. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave D, & Mukerjee S (2011). Mental health parity legislation, cost-sharing and substance-abuse treatment admissions. Health Economics, 20(2), 161–183. doi: 10.1002/hec.1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delker E, Brown Q, & Hasin DS (2016). Alcohol consumption in demographic subpopulations: an epidemiologic overview. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(1), 7–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, & Smith J (2007). Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2006 [Accessed: 2012-07-11. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/695Y9Zr8R] Current Population Reports (pp. 78). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Doty MM (2003). Hispanic patients’ double burden: Lack of health insurance and limited English. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL, Harwood JM, Thalmayer A, Ong MK, Xu H, Bresolin MJ, … Azocar (2016). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act evaluation study: Impact on specialty behavioral health utilization and expenditures among “carve-out” enrollees. Journal of Health Economics, 50, 131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Xu H, Harwood JM, Azocar F, Hurley B, & Ettner SL (2017). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act evaluation study: impact on specialty behavioral healthcare utilization and spending among enrollees with substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 80, 67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SA, Azocar F, Xu H, & Ettner SL (2018). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) evaluation study: Did parity differentially affect substance use disorder and mental health benefits offered by behavioral healthcare carve-out and carve-in plans? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SA, Thalmayer AG, Azocar F, Xu H, Harwood JM, Ong MK, … Ettner SL (2018). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act Evalution Study: impact on mental health financial requirements among commercial “carve-in” plans. Health Services Research, 53(1), 366–388. doi: 10.1111/1475-3773.12614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer J, Bose J, Trunzo D, Strashny A, Batts K, & Pemberton M (2013). Estimating substance abuse treatment: a comparison of data from a Household Survey, a Facility Survey, and an Administrative Data Set FCSM Research Conference Washington, DC: November 5. [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Bohnert KM, & Brown RL (2016). Alcohol screening and intervention among United States adults who attend ambulatory healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(7), 739–745. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3614-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood JM, Azocar F, Thalmayer A, Xu H, Ong MK, Tseng C-H, … Ettner SL (2017). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act Evaluation Study: impact on specialty behavioral health care utilization and spending among carve-in enrollees. Medical Care, 55(2), 164–174. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. (2013). Key facts about the uninsured population Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera C-N, Hargraves J, & Stanton G (2013). The Impact of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act on Inpatient Admissions [Accessed: 2014-07-21. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6RErApuJ0] (pp. 10). Washington, DC: Health Care Cost Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan J (2011). The 2007–09 recession and health insurance coverage. Health Affairs, 30(1), 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Hodgkin D, Stewart MT, Quinn A, Merrick EL, Reif S, … Creedon TB (2016). Health plans’ early response to federal parity legislation for mental health and addiction services. Psychiatric Services, 67(2), 162–168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, & Van Horn SL (2017). Trends in substance use disorders among adults aged 18 or older The CBHSQ Report: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, & Tugwell P (2013). What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(2), 190–193. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann C (2013, January 16). [[Letter to State Health Directors and State Medicaid Directors] Re: Application of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act to Medicaid MCOs, CHIP, and Alternative Benefit (Benchmark) Plans [Accessed: 2014-07-29. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6RQs6Kib9]]. [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Hodgkin D, Levit KR, & Thomas CP (2016). Growth in spending on and use of services for mental and substance use disorders after the great recession among individuals with private insurance. Psychiatric Services, 67(5), 504–509. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Kassed CA, Vandivort-Warren R, Levit KR, & Kranzler HR (2009). Alcohol and opioid dependence medications: prescription trends, overall and by physician specialty. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99(1–3), 345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell KJ, Ridgely MS, & McCarty D (2012). What Oregon’s parity law can tell us about the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and spending on substance abuse treatment services. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(3), 340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Busch SH, A. SE, Huskamp HA, Gibson TB, Goldman HH, & Barry CL (2015). Federal parity law associated with increased probability of using out-of-network substance use disorder treatment services. Health Affairs, 34(8), 1331–1339. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow S, Long SK, Kenney GM, & Anderson N (2015). Uninsurance disparities have narrowed for Black and Hispanic adults under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs, 34(10), 1774–1778. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity Task Force. (2016). Final Report [Accessed: 2019-03-18. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/mental-health-substance-use-disorder-parity-task-force-final-report.pdf]: Executive Office of the President of the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Mauro C, Wall MM, Barry CL, & Olfson M (2019). Medication treatment for opioid use disorders in substance use treatment facilities. Health Affairs, 38(1), 14–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Mauro C, Wall MM, Barry CL, & Olfson M (in press). The Affordable Care Act and opioid agonist therapy for opioid use disorder. Psychiatric Services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, & Gerberding JL (2004). Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA, 291(10), 1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, & Jones-Webb R (2017). Alcohol policy: a tool for addressing health disparities? In Giesbrecht N & Bosma LM (Eds.), Prevention of Alcohol-Related Problems: Evidence and community-based initiatives (pp. 377–395). Washington, DC: APHA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Tam TW, & Schmidt LA (2014). Disparities in the use and quality of alcohol treatment services and some proposed solutions to narrow the gap. Psychiatric Services 65(5), 626–633. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE (2009). Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(4), 654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Zemore SE, Murphy R, Liu H, & Catalano R (2014). Economic loss and alcohol consumption and problems during the 2008 to 2009 U.S. recession. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(4), 1026–1034. doi: 10.1111/acer.12301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2006). Inventory of State Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Activities and Expenditures, Executive Summary [Available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/ondcppubs/publications/inventory/executive_summary.pdf]. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President (Publication No. NCJ 216918). [Google Scholar]

- Peterson E, & Busch S (2018). Achieving mental health and substance use disorder treatment parity: a quarter century of policy making and research. Annual Review of Public Health, 39, 421–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pubhealth-040617-013603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Akosa Antwi Y, Maclean JC, & Cook B (2018). Access to health insurance and utilization of substance use disorder treatment: evidence from the Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Provision. Health Economics, 27(1), 50–75. doi: 10.1002/hec.3482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA (2016). Recent developments in alcohol services research on access to care. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(1), 27–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Bond J (2007). Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(1), 48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp A, Jones A, Sherwood J, Kutsa O, Honermann B, & Millett G (2018). Impact of Medicaid expansion on access to opioid analgesic medications and medication-assisted treatment. American Journal of Public Health (AJPH), 108(5), 642–648. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Huang B, & Saha T (2005). Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 80(1), 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Behavioral Health Spending and Use Accounts, 1986–2014. HHS Publication No. SMA-16–4975. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2015). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2003–2013 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. BHSIS Series S-75, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15–4934. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2016 Admissions to and Discharges from Publicly Funded Substance Use Treatment. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Thalmayer AG, Friedman SA, Azocar F, Harwood JM, & Ettner SL (2017). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) Evaluation Study: impact on quantitative treatment limits. Psychiatric Services, 68(5), 435–442 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Charting the labor market: data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) [Available at: https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cps_charts.pdf].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: the Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health [Accessed: 2017-03-07. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6onCCszJk]. Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2011). Treatment Episode Data Set -- Admissions (TEDS-A), 2011: Codebook (ICPSR 34876) Accessed: 2014-07-28. [Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6RPhmXRXk] (pp. 64). Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Borders TF, & Cummings JR (2019). Trends in buprenorphine prescribing by physician specialty. Health Affairs, 38(1), 24–28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Gaydos LM, & Druss BG (2013). State parity laws and access to treatment for substance use disorders in the United States: implications for federal parity legislation. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(12), 1355–1362. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, & Smith GT (2014). Less drinking, yet more problems: understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 188–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Murphy RD, Mulia N, Gilbert PA, Martinez P, Bond J, & Polcin DL (2014). A moderating role for gender in racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol services utilization: results from the 2000 to 2010 National Alcohol Surveys. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(8), 2286–2296. doi: 10.1111/acer.12500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]