Abstract

Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) is widely used as a model chemical to study hypersensitive responses to biotic stress impacts in plants. Elevated levels of methyl jasmonate induce jasmonate-dependent defense responses, associated with a decline in primary metabolism and enhancement of secondary metabolism of plants. However, there is no information of how stress resistance of plants, and accordingly the sensitivity to exogenous MeJA can be decreased by endophytic plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) harboring ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate) deaminase. In this study, we estimated stress alleviating potential of endophytic PGPR against MeJA-induced plant perturbations through assessing photosynthetic traits and stress volatile emissions. We used mild (5 mM) to severe (20 mM) MeJA and endophytic plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Burkholderia vietnamiensis CBMB40 and studied how MeJA and B. vietnamiensis treatments influenced temporal changes in photosynthetic characteristics and stress volatile emissions. Separate application of MeJA markedly decreased photosynthetic characteristics and increased lipoxygenase pathway (LOX) volatiles, volatile isoprenoids, saturated aldehydes, lightweight oxygenated compounds (LOC), geranyl-geranyl diphosphate pathway (GGDP) volatiles, and benzenoids. However, MeJA-treated leaves inoculated by endophytic bacteria B. vietnamiensis had substantially increased photosynthetic characteristics and decreased emissions of LOX, volatile isoprenoids and other stress volatiles compared with non-inoculated MeJA treatments, especially at later stages of recovery. In addition, analysis of leaf terpenoid contents demonstrated that several mono- and sesquiterpenes were de novo synthesized upon MeJA and B. vietnamiensis applications. This study demonstrates that foliar application of endophytic bacteria B. vietnamiensis can potentially enhance resistance to biotic stresses and contribute to the maintenance of the integrity of plant metabolic activity

Keywords: Eucalyptus grandis, isoprene, methyl jasmonate, monoterpenes, photosynthesis, plant growth promoting rhizobacteria

1. Introduction

Plants produce an array of volatiles either constitutively or in response to direct impacts of different stresses and in response to airborne stress signals (Niinemets, 2010). Jasmonates (JA) are lipid-derived hormones, acting as key plant growth regulators and plant immunizing agents (Katsir et al., 2008; Lalel et al., 2003). Generally, abiotic and biotic stresses modulate endogenous levels of jasmonic acid and its methylated volatile ester, methyl jasmonate (MeJA) (Jiang et al., 2017a). Elevated levels of MeJA released into the air from plants acts as a signaling cue for triggering jasmonate-dependent defense pathways in undamaged parts of the affected plants or adjacent plants (Heil and Ton, 2008; Jiang et al., 2017a; Tamogami et al., 2008). Activation of jasmonate-triggered signalling will often lead to modulation of the activity of secondary metabolic pathways, including changes in constitutive defences and activation of stress-elicited defences including release of stress volatiles (Repka et al., 2013; Zhang and Xing, 2008).

Time-courses of volatile emissions can be diagnostic clues for estimation of the rate of priming and acclimation responses during and/or after stress-impacts (Kanagendran et al., 2017; Kanagendran et al., 2018a; Niinemets, 2010; Timmusk et al., 2014). Exogenous MeJA treatments often activate volatile biosynthesis pathways, particularly LOX (lipoxygenase), MEP/DOXP (2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate/1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate), MVA (mevalonate) and shikimate pathways, eventually leading to enhanced emission rates of LOX pathway volatiles and volatile isoprenoids (Jiang et al., 2017a; Mäntylä et al., 2014; Semiz et al., 2012). In fact, the emission of lipoxygenase pathway volatiles (LOX pathway volatiles, also called green leaf volatiles, GLV) is considered as a characteristic early stress response, followed by the emission of volatile isoprenoids: isoprene, monoterpenes, and sesquiterpenes (Kanagendran et al., 2018b; Kanagendran et al., 2018a). However, after the initial rapid emission, there is a second or third elicitation response corresponding to endogenous activation of JA pathway in 10-30 h since the initial stress impact (Jiang et al., 2017a; Li et al., 2017). These emissions of LOX pathway volatiles do reflect the stress status in the plant and are also involved in attracting herbivore enemies and priming adjacent plants (Copolovici et al., 2014a; Copolovici et al., 2011; Frost et al., 2008).

Generally, biotic stresses result in enhanced emission rates of LOX pathway volatiles, volatile isoprenoids, and volatile benzenoids (Heil and Ton, 2008; Kappers et al., 2010). In biotic stress studies, the emission rates of stress-induced volatiles are often positively correlated with the severity of biotic stress, e.g., with the percentage of leaf area eaten, the degree of fungus and bacterial infection, and the number of feeding larvae. Nevertheless, quantitative scaling of biotic stresses in plants is often difficult due to their complex localized spread and temporal impacts (Copolovici and Niinemets, 2016; Jiang et al., 2017a; Niinemets et al., 2013). Given that MeJA activates jasmonate-dependent defense pathways, exogenous application of MeJA with precisely defined doses is often employed to mimic biotic stress (Jiang et al., 2017a; Shi et al., 2015; Suh et al., 2013). In fact, previous studies revealed that a blend of volatiles induced by MeJA is almost similar to the emission blend elicited by herbivores, including geometrid moth Cabera pusaria feeding on European alder Alnus glutinosa (Copolovici et al., 2011), Spodoptera exigua caterpillars feeding on tomato Solanum lycopersicum (Thaler et al., 2002), gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) caterpillars attack of blueberry Vaccinium corymbosum (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2009), herbivores Pieris rapae and Plutella xylostella feeding on cabbage Brassica oleracea (Bruinsma et al., 2009), and pathogens, including infection by leaf rust of Salix spp. (Toome et al., 2010), by oak powdery mildew (Erysiphe alphitoides) of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) leaves (Copolovici et al., 2014b) (Brüggemann and Schnitzler, 2001), by Ceratocystis fagacearum fungus of live oak (Q. fusiformis) plants (Anderson et al., 2000), by oak gall wasps of Quercus robur leaves (Jiang et al., 2017b) and by Fusarium poae fungus of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) (Pańka et al., 2013). In addition, MeJA response is dose specific and higher doses of MeJA are known to cause hypersensitive reactions and programmed cell death similarly to necrotic lesion formation in response to insect and pathogen elicitors and severe abiotic stresses such as ozone stress (Jiang et al., 2017a; Repka et al., 2013; Zhang and Xing, 2008). Furthermore, similar to real biotic stresses, the volatiles induced by exogenous MeJA applications demonstrated attractiveness to herbivore enemies and repellency to herbivores (Bruinsma et al., 2009; Moraes et al., 2009; Ozawa et al., 2008). Taken together, these reports collectively underscore the biological significance of MeJA as a model for biotic stress impacts and chemical signaling.

In agriculture, there is a variety of strategies employed to enhance plant stress resistance, including breeding for stress resistance, developing transgenic plants, and using plant-growth-promoting-rhizobacteria (PGPR) (Chatterjee et al., 2018a; Koevoets et al., 2016; Mickelbart et al., 2015). Several studies have indicated that application of PGPR successfully alleviated the severity of biotic (Jain and Choudhary, 2014; Kadaikunnan et al., 2015; Nguyen and Kim, 2015) and abiotic stresses (Abd El-Daim et al., 2014; Chatterjee et al., 2017). Therefore, inoculating plants by PGPR is a highly effective, an economically feasible, and a relatively simple approach to cope with many negative effects of stresses in plants (Timmusk et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2009). A vast amount of literature demonstrates a positive impact of PGPR on plant growth, development and enhanced stress tolerance upon seed or root inoculation by PGPR (Abd El-Daim et al., 2014; Figueiredo et al., 2008; Koevoets et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2006; Onofre-Lemus et al., 2009; Timmusk et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2009; Zahir et al., 2003), but there is a scarcity of information about the changes in stress resistance due to inoculation of leaves by PGPR. Very few studies have demonstrated a significant outcome in plant growth and development in response to foliage inoculation by PGPR (Esitken et al., 2002; Esitken et al., 2003; Esitken et al., 2006; Esitken et al., 2010).

So far, there is no clear-cut mechanism of how PGPR can affect MeJA-induced plant stress responses. However, there are many explanations emphasizing the possible mechanisms of stress resistance enhancement by PGPR, including: (1) PGPR biosynthesize 1-amino cyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACC deaminase) that catalyzes the formation of α-ketobutyrate and ammonia from ethylene precursor; as the result, the hypersensitive ethylene-induced stress response was curbed (Chatterjee et al., 2018a; Chatterjee et al., 2017; Chatterjee et al., 2018b); (2) PGPR quantitatively increased ROS-scavenging enzymes and in turn, alleviated the effects of oxidative stress in plants (Mastouri et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012); (3) inoculation by PGPR led to enhanced biosynthesis of plant growth regulators IAA, gibberellic acid, cytokinins, and auxin, ultimately augmenting primary and secondary metabolism in plants (Figueiredo et al., 2008); and (4) PGPR biosynthesized certain antioxidants, i.e catalase, that increased induced-systemic resistance in plants (Yang et al., 2009). There is very limited information about the impact of PGPR on photosynthetic traits and volatile emission responses in plants under stress (Chatterjee et al., 2018a). Therefore, the main goal of this work was to estimate the stress tolerance potential of endophytic PGPR in response to foliage inoculation through assessing volatile emissions and photosynthetic traits.

In the present study, we used flooded gum (Eucalyptus grandis), a model plant frequently used in isoprenoid studies (Henery et al., 2008; Myburg et al., 2014; Oates et al., 2015). Eucalyptus species and subspecies are endemic to Australian continent, but many Eucalyptus spp., including E. grandis, are extensively grown in tropical, subtropical, and Mediterranean and warm temperate climates due to their high adaptability and rapid growth rate in a wide range of climatic conditions and soil types (Külheim et al., 2015). In addition, eucalypts are strong constitutive-isoprenoid emitters and therefore often used as potential model species in volatile isoprenoid emission studies (Funk et al., 2006; Guenther et al., 1991; He et al., 2000; Kanagendran et al., 2018a; Street et al., 1997; Winters et al., 2009). A distinctive morphological feature of eucalypt leaves is the presence of numerous and relatively large sub-dermal secretory cavities (~200 μm diameter) and oil-glands, where volatile and non-volatile terpenoids are stored (Goodger et al., 2016; Külheim et al., 2015). As a common phenomenon in terpene-storing plant species including eucalypts, terpenes are slowly diffusing out of storage pools in a temperature-dependent manner (Grote and Niinemets, 2008; Kanagendran et al., 2018a). In addition, several storage emitters also synthesize mono- and sesquiterpenes in a light and temperature-dependent manner in mesophyll cells either constitutively or during stress (Grote et al., 2013; Holzke et al., 2006). Ultimately, the sum of storage and de novo emissions of mono- and sesquiterpenes makes up the total volatile emission blend of a given species under given set of environmental conditions (Copolovici and Niinemets, 2016). However, there is still a lack of information about the regulation volatile emissions upon biotic and abiotic stresses in eucalypts.

In this study, we used Burkholderia vietnamiensis CBMB40 (GenBank Accession No: AY683043) as plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Burkholderia vietnamiensis CBMB40 is a methylotrophic bacterium and an endophytic and nitrogen fixing strain (Madhaiyan et al., 2008). In addition, B. vietnamiensis CBMB40 biosynthesizes indole-3-acetic acid that enhances photosynthetic characteristics in plants (Aldesuquy, 2000). Furthermore, B. vietnamiensis CBMB40 produces ACC deaminase and also expresses a high antagonistic activity against biotic stress caused by phytopathogen Erwinia caratovora subsp. caratovora in plants (Madhaiyan et al., 2008). Our primary study indicated that B. vietnamiensis CBMB40 can grow successfully in a medium containing higher MeJA doses. Furthermore, several Burkholderia species have developed strong beneficial interactions with plants and colonize roots, stems and even leaves (Coenye and Vandamme, 2003; Estrada-De Los Santos et al., 2001).

We applied precisely defined doses (0-20 mM) of MeJA solution to B. vietnamiensis inoculated and un-inoculated leaves of E. grandis and studied time-dependent variations in photosynthetic traits and different classes of stress volatile emission rates after treatments. In addition, we analyzed terpenoid content and composition in untreated E. grandis leaves to estimate the storage capacity for foliage terpenes and differentiate stored and de novo synthesized terpenoids. We soughed to study (1) whether foliage inoculation by endophytic bacteria B. vietnamiensis enhances photosynthetic traits upon subsequent MeJA treatments; (2) how foliage inoculation by B. vietnamiensis impacts foliage volatile emissions in response to subsequent treatments of MeJA; and (3) how bacterial inoculation alters the relationship between photosynthetic traits and volatile emission throughout the stressed-period upon MeJA treatments in inoculated and non-inoculated leaves of E. grandis. We hypothesized that (1) exogenous application of MeJA reduces photosynthetic traits and the degree of reduction scales with MeJA dose; (2) exogenous application of MeJA immediately elicits stress volatile emissions, followed by elicitation of specific isoprenoid and benzenoid emissions and after reaching the maximum values, the emissions decline after stress applications; (3) foliage inoculation by B. vietnamiensis enhances photosynthetic traits and decreases volatile emission rates; and (4) changes in photosynthetic traits and volatile emission upon MeJA treatments in bacteria-inoculated leaves are less than those in non-inoculated leaves, suggesting that B. vietnamiensis inoculation protects plant cells from subsequent oxidative stress. We know of no studies investigating the impact of foliar inoculation of symbiotic methylotrophic bacteria on plant volatiles, and changes in simulated biotic stress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants and growth conditions

Three-year-old eucalypt (E. grandis) plants were used in this experiment. The plants were grown in 10 L pots filled with commercial potting mixture (Biolan Oy, Kekkilä group, Finland) and supplemented with essential macronutrients N (100 mg L-1), P (30 mg L-1), and K (200 mg L-1) and micronutrients. The soil water pH in the pots was 6.2. The plants were grown in a plant growth room under the controlled environmental conditions of light intensity of 300 - 400 μmol m-2 s-1 (HPI-T Plus 400 W metal halide lamps, Philips) provided for 12 h photoperiod, day/night temperature of 28/25 °C, ambient CO2 concentration of 380-400 ppm, and relative air humidity of 60-70%. Plants were regularly watered to soil field capacity. Plants were fertilized once a week with a liquid fertilizer (Baltic Agro, Lithuania). The fertilizer included NPK (N: P2O5: K2O - 5:5:6), and micronutrients B (0.01%), Cu (0.03%), Fe (0.06%), Mn (0.028%), and Zn (0.007%), and at each time, each plant was fertilized with 80 mL diluted liquid fertilizer (ca. 0.4% solution) for the optimum plant growth.

2.2. Bacterial strain, culture conditions, media and foliage applications

Burkholderia vietnamiensis CBMB40 was grown in an ammonium mineral salt (AMS) medium supplemented with 0.5 % sodium succinate as a sole carbon source, according to the protocol of Lee et al. (2006). The bacterial culture was allowed to grow up to mid exponential phase in AMS broth, then the culture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, the cell pellets were washed twice, and finally the bacterial suspension was prepared in 0.03 M MgSO4. Our preliminary study indicated that B. vietnamiensis CBMB40 successfully grew in the growth medium that contained up to 50 mM MeJA. The bacterial inoculation in E. grandis leaves was carried out as a foliar spray on both sides of the leaves. One ml of bacterial solution was applied to each leaf. In the case of combined application of bacteria and MeJA (bacteria and MeJA), first the leaves were sprayed with bacteria once in a day for four consecutive days. Thereafter, the plants with leaves inoculated with bacteria were kept in a controlled growth room for 10 days for optimum growth of bacteria and then MeJA applications were carried out.

2.3. MeJA application protocol

A variety of protocols have been used for the preparation and application of MeJA on plants (Heijari et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2017a; Liang et al., 2006; Loivamäki et al., 2004). A comparison of various protocols suggested that the use of aqueous ethanol (5-20%) as a solvent for MeJA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was the most suitable method as it was associated with negligible non-specific effects in control (aqueous alcohol) treatments (Jiang et al., 2017a). In our study with thick highly hydrophobic leaves of eucalypt, we used MeJA dissolved in 20% ethanol solution. As in the study of Jiang et al. (2017a), there were no significant differences in photosynthetic characteristics and volatile emissions between the untreated leaves and the leaves treated with 20% ethanol. To construct MeJA dose responses, the following concentrations of 1 ml of MeJA solution were sprayed on both sides of each individual leaf: 0 (control), 5, 10, and 20 mM MeJA. In all cases, a randomly selected branch of the same age and similar biomass, consisting of three fully mature leaves was selected for MeJA treatments, and each different MeJA dose treatment was applied to three individual plants. In the case of combined application of bacteria and MeJA, first the leaves were inoculated with bacteria as described above and then, MeJA was applied as for the treatments with MeJA alone. Immediately after treatments, the plants were kept in the plant growth room under controlled environmental conditions (see “Plants and growth conditions” for details).

2.4. Description of the gas-exchange system and measurement set-up

A custom-made cylindrical glass chamber (1.2 L) was used to measure gas exchange and volatile emission rates. The temperature of the glass chamber was maintained constant at 25 °C by circulating distilled water of 25 °C between the double layers of the glass chamber. The measurement light was provided by four halogen lamps, and its intensity was controlled at 700 - 800 μmol m-2 s-1 at the leaf surface by a dimming regulator. The leaf temperature varied between 27 - 29 °C. The measurement air was taken from outside and purified by passing through a charcoal-filter and a custom-made ozone trap, and humidified by a custom-made humidifier. During the measurements, the ambient CO2 concentration was 390 - 400 ppm and the relative air humidity 60 - 70 % in the chamber. The air temperature inside the glass chamber was measured by a thermistor (NTC thermistor, model ACC-001, RTI Electronics, Inc., St. Anaheim, CA, USA) and the leaf temperature was monitored by a thermocouple. A fan (Sunon Group, Beijing, China) inside the chamber provided high air turbulence, resulting in high leaf boundary layer conductance with no still air pockets. The bottom of the chamber had an opening for the leaf petiole. After the enclosure of the leaf, the chamber opening was sealed with low-emitting modelling clay to ensure there was no air leakage from or into the chamber. All chamber connections were made of stainless steel and all tubing was made of Teflon® to assure low adsorption of volatile on the system surfaces. Reference and measurement modes at the chamber-inlet and outlet ports were used to take gas exchange measurements and volatile sampling.

CO2 and H2O concentrations at reference (ingoing air) and measurement (outgoing air) modes were estimated by an infrared dual-channel gas analyzer (CIRAS II, PP-systems, Amesbury, MA, USA). All measurements were taken when stomata opened and steady chamber CO2 and H2O concentrations were achieved, ca. 15-20 min. after leaf enclosure and then volatiles were collected as explained below. Foliage net assimilation rate (A) and stomatal conductance to water vapor (gs) per projected unit leaf-area were estimated according to von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981). A detail description of the similar glass chamber set up can be found in Kanagendran et al. (2018a) and Copolovici and Niinemets (2010).

In the case of bacterial inoculation alone, the gas exchange and volatile measurements taken at days 1, 3, and 7 referred to the number of days after the last bacterial inoculations were carried out, whereas in the case of separate MeJA, and combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, the gas exchange and volatile measurements taken at days 1, 3, and 7 referred to the number of days after MeJA treatments were carried out.

2.5. VOC collection and analysis by gas-chromatography/mass spectrometry

Volatiles emitted by the leaves were collected onto stainless steel adsorbent cartridges, filled with three Carbotrap adsorbents with different surface area and mesh size. The three different types of adsorbent materials are carbotrap C 20-40 mesh, carbopack B 40-60 mesh, and carbotrap X 20-40 mesh (Kännaste et al., 2014). An air sample of four liters was sampled through the chamber-outlet onto the adsorbent cartridges, using an air sample portable pump 210-1003MTX (SKC Inc., Houston, TX, USA) operated at a constant suction rate of 0.2 l min-1 for 20 minutes. The cartridges were analyzed for VOC in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Shimadzu TD20 automated cartridge desorber and Shimadzu 2010 Plus GC-MS instrument, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), with a Zebron ZB-624 fused silica capillary column (0.32 mm i.d., 60 m length, 1.8 μm film thickness, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA).

A two-step desorption method was employed to analyze the stainless steel cartridges in GC-MS. In the first step, He purge flow was set to 40 ml / min, primary desorption temperature to 250 °C, and primary desorption time to 6 min. In the second step, a trap temperature during primary desorption was set to -20 °C, and the second stage trap desorption temperature was set to 280 °C and the withhold time of 6 min (Kännaste et al., 2014).

GC oven program used for separation of the volatile compounds was as follows: 40 °C for 1 min, 9 °C / min to 120 °C, 2 °C / min to 190 °C, 20 °C / min to 250 °C, and eventually maintaining for 250 °C for 5 min. The mass spectrometer of GC-MS instrument was operated in electron-impact mode (ei) at 70 eV in the scan range of m/z 30 - 400. The transfer line temperature was set to 240 °C and ion-source temperature was set to 150 °C. The cartridges were analyzed for qualitative and quantitative estimation of LOX pathway volatiles, volatile isoprenoids, saturated aldehydes, lightweight oxygenated volatile organic compounds (LOC), geranyl-geranyl diphosphate pathway volatiles (GGDP volatiles), and benzenoids. Compounds were identified by mass spectra of national institute of standards and technology (NIST 05) library based on retention time identity and confirmed with the authentic standards (GC purity) (Kännaste et al., 2014). The emission rates of individual volatiles and total emissions for different volatile compound classes per unit leaf area were estimated according to the following equation (Liu et al., 2018; Niinemets et al., 2011).

In this equation, φe is the emission rate of a VOC (nmol m-2 s-1); Pi is its peak area in the chromatogram, F is the rate of air flow (1.4 L min-1) in the glass chamber; C is the calibration factor (nmol-1) calculated by dividing peak area in the chromatogram by the amount of a standard compound for given VOC; S is the enclosed leaf area (m2) in the chamber; and V is the volume (L) of gas collected onto cartridges during 20-min collection. The volatile measurements in the empty chamber were also carried out to estimate the net foliage emission rate of volatiles per unit leaf area. A detailed description of the adsorbent cartridges, and the method of volatile collection and GC-MS analysis is provided in Toome et al. (2010) and Kännaste et al. (2014).

2.6. Measurement of foliage chlorophyll fluorescence and estimation of leaf area

Upon completion of gas-exchange measurements and VOC collection, leaves were darkened for 10 min and dark-adapted maximum chlorophyll fluorescence yield (Fv/Fm) was estimated with an imaging PAM flourometer (Walz IMAG-MIN/B, Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). First, the minimum fluorescence yield (Fo) was estimated, followed by the application of a 1 s saturating pulse (7000 μmol m-2 s-1) blue light (460 nm) to asses Fm. After these measurements, the leaves were scanned at 300 dpi to estimate the leaf area using a custom-made software tool.

2.7. Quantitative estimation of foliage terpene contents

Terpene contents were quantitatively estimated for untreated leaves of E. grandis after hexane extraction. For the extraction, six fresh leaf samples (120 ± 30 mg) were randomly taken from six mature leaves of individual plants. The samples were transferred in 2 ml tubes with 2.8 mm stainless-steel beads (Bertin Technologies, Aix-en-Provence, France). Tubes containing fresh leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and then 1.5 ml GC-grade hexane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each tube. The samples were homogenized with a homogenizer (Precellys 24, Bertin Technologies, Aix-en-Provence, France) at 2400 g for 30 seconds at 25°C. Thereafter, the homogenized mixture was incubated in a Thermo-Shaker (TS-100C, Biosan, Riga, Latvia) for 3 h at 1000 rpm at 25°C. After incubation, samples were centrifuged (Universal 320R, Hettich, Tuttlingen, Germany) for 30 sec at 13200 g at 25°C. One point five millilitre of supernatant was transferred to a 2 ml GC-MS glass vial (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for further GC-MS analysis. One microlitre of sample was injected into GC-MS. The quantitative estimation of foliage terpene contents was estimated as follows,

In this equation, φm is the foliage terpene content (nmol g-1DM), Pi is the peak area of given compound in a chromatogram, C is the calibration factor of a compound (nmol/ peak area), Vf is the final volume (μl) of supernatant in GC-MS vial, m is the dry mass (g) of a fresh leaf sample, Vi is the injected volume (μl) of sample into GC-MS.

2.8. Data analysis

In this study, there were four replicates for control and bacterial treatments, and three replicates for separate MeJA, and combined bacteria and MeJA treatments. All data were checked for normality of distributions and homogeneity of variances according to Shapiro-Wilk and Levene's tests. When appropriate, the data were log-transformed to comply with normality and homoscedasticity assumptions for parametric tests. Generalized Linear Models (GLM) with maximum likelihood model fitting were used to estimate individual and interactive effect of MeJA, bacteria, and time (number of days after treatments) on photosynthetic characteristics, and volatile emission rates. GLM were conducted with SPSS v.24 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted with RStudio (R version 3.5.1) using the package of ‘Factoextra’ (Alboukadel and Fabian, 2017) to test for the efficiency of bacterial and MeJA treatments on VOC emissions. In addition, we performed a partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) using the package of ‘DiscriMiner’ (Gaston, 2013) in Rstudio (R version 3.5.1) for various volatile blends upon different treatments at 1, 3, and 7-days after treatments, to identify which VOC-class primarily contributed to the discrimination between treatments using the first two partial least square (PLS) components. All plots were done with SigmaPlot version 12.5 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA, USA), except for PCA and PLS-DA plots that were made with Rstudio. In all cases, the effects were statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of MeJA and bacterial treatments on time-courses of foliage photosynthetic characteristics

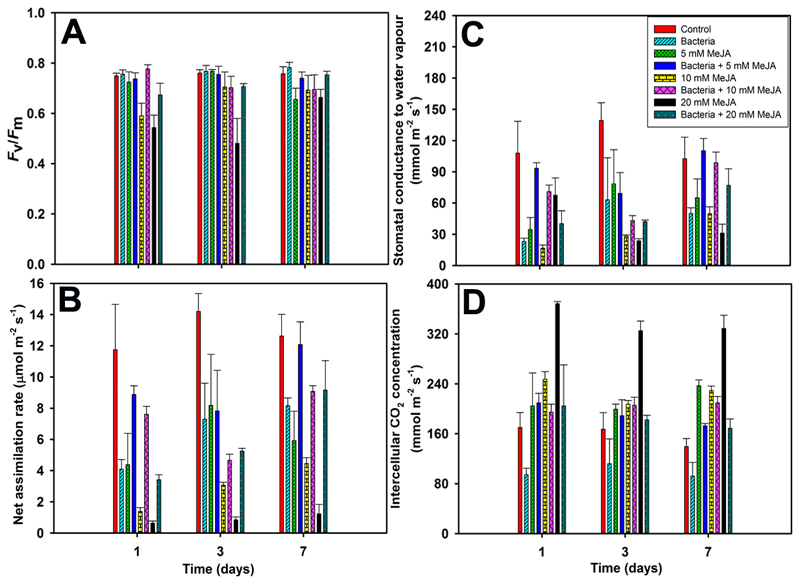

The dark-adapted photosystem II (PS II) quantum yield estimated by chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) decreased in MeJA-treated leaves, especially in leaves treated with 10 and 20 mM MeJA (Table 1, Fig. 1A). However, Fv/Fm was not significantly affected by bacterial treatment and by the combined bacteria and MeJA treatments, albeit there was a tendency of lower Fv/Fm in 20 mM bacteria and MeJA treated leaves (Table 1, Fig. 1A). Fv/Fm was fully recovered by day 7 for 10 mM MeJA treatment, but not for 5 mM and 20 mM treatment (Fig. 1A, Table 1).

Table 1.

Output of generalized linear model (GLM) for individual and interactive effects of methyl jasmonate (MeJA) application and bacterial inoculation, and bacteria and MeJA treatments, and effects of time after treatments (1, 3, and 7 days after treatment) on dark-adapted (10-minute darkening) maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) estimated by chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm), foliage net assimilation rate, and stomatal conductance to water vapor, and intercellular CO2 concentration in E. grandis leaves. Stress application protocol and the baseline environmental conditions during measurements as in Fig. 1. P values show the significance of wald chi-square (χ2) statistics.

| Physiological characteristics | Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | P value | ||

| Fv/Fm | MeJA | 65.113 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 1.498 | 1 | 0.221 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.880 | 1 | 0.049* | |

| Time | 1.757 | 1 | 0.185 | |

| MeJA x Time | 7.261 | 1 | 0.007** | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.436 | 1 | 0.509 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.879 | 1 | 0.170 | |

| Net assimilation rate (A) | MeJA | 167.047 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 6.433 | 1 | 0.011* | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 21.395 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 12.813 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.117 | 1 | 0.732 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.044 | 1 | 0.833 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.292 | 1 | 0.589 | |

| Stomatal conductance to water vapor (gs) | MeJA | 19.723 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 16.649 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 7.860 | 1 | 0.005** | |

| Time | 9.792 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| MeJA x Time | 3.136 | 1 | 0.077 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.135 | 1 | 0.713 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.002 | 1 | 0.964 | |

| Intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) | MeJA | 67.413 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 72.504 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.066 | 1 | 0.797 | |

| Time | 0.295 | 1 | 0.587 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.000 | 1 | 0.991 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.004 | 1 | 0.948 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.000 | 1 | 0.998 | |

Figure 1.

Representative time-courses (mean + SE) of dark-adapted maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PS II) estimated by chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm: A), net assimilation rate (A: B), stomatal conductance to water vapor (gs: C), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci: D) of control, endophytic bacteria-inoculated (Burkholderia vietnamiensis CBMB40), MeJA treated (5, 10, and 20 mM MeJA in 20% ethanol), and bacteria and MeJA treated leaves (first inoculated with bacteria, followed by 5, 10, and 20 mM MeJA treatments) at 1, 3, and 7 days after treatments in Eucalyputs grandis. The bacterial inoculation of E. grandis leaves was carried out as foliar spray on both sides of the leaves for four consecutive days. In the case of combined application of MeJA and bacteria, first the leaves were sprayed with bacteria once a day for four consecutive days and then the plants with selected leaves inoculated with bacteria were kept in a controlled growth room for 10 days for optimum growth of bacteria in the leaves before MeJA applications. In fact, there were no significant temporal changes in photosynthetic characteristics between the leaves treated with 20% ethanol and non-treated leaves. In this experiment, mature leaves of three-year-old eucalypt plants were used. Photosynthetic measurements were conducted upon establishing a stable gas flow in the glass chamber. The baseline environmental conditions during measurements were: PPFD of 700-800 μmol m-2 s-1, leaf temperature of 27 - 29 °C, ambient CO2 concentration of 390-400 μmol mol-1, and relative air humidity of 60-70 %. In this study, there were four replicates for control and bacterial treatments, and all other treatments were replicated thrice. The details of statistical analysis as in Table 1.

Bacterial treatment alone resulted in reduced net assimilation rate (A) and stomatal conductance (gs) at day 1, but both traits slightly increased at days 3 and 7 (Fig. 1B and 1C, Table 1). Similarly, A and gs in response to separate MeJA and combination of bacterial and MeJA treatments were slightly increased at days 3 and 7 (P < 0.01, Table 1); however, a sustained decline in both physiological traits was observed for separate MeJA treatments, compared to combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. 1B and 1C). Overall, the reduction was particularly large at day 1 after the MeJA treatment and then a partial recovery was observed (Fig 1B and 1C, Table 1). In all cases, changes in A and gs were highly correlated throughout the stressed-phase. However, in bacterial treatment alone, intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) was reduced, but for MeJA treatments, Ci was increased (P < 0.001, Table 1 for separate bacterial and MeJA treatments). In fact, Ci was invariable for bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. 1D, P < 0.5, Table 1).

3.2. Temporal changes in constitutive isoprene emissions in dependence on MeJA and bacterial treatments

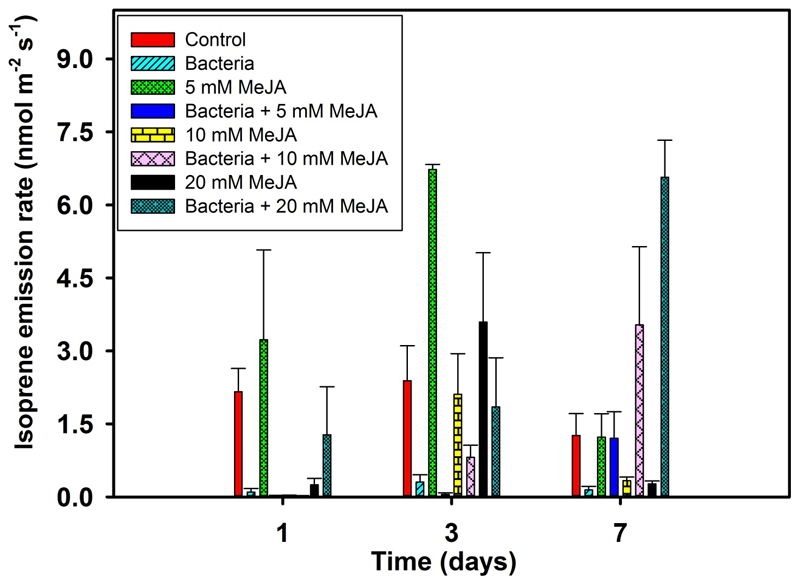

In control leaves, the baseline emission rate of isoprene varied between 1.3 - 2.4 nmol m-2 s-1 (Fig. 2, Table 2). However, surprisingly, isoprene emission was suppressed by bacterial treatment alone (P < 0.001, Table 2), but it was initially elicited to the higher level when the leaves were treated with MeJA alone and with bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. 2, Table 2). The highest elicitation of isoprene emission rate varied with the type of treatments; it was at day 3 for separate MeJA treatments and at day 7 for combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Temporal variation (means + SE) in isoprene emission rate from E. grandis leaves in response to control, bacterial inoculation, MeJA treatments (5, 10, and 20 mM), and bacterial and MeJA treatments (first inoculated with bacteria, followed by 5, 10, and 20 mM MeJA treatments) at 1, 3, and 7 days after treatments. Details of treatments and replications, and standard environmental conditions during measurements as in Fig. 1. Details of statistical analysis as in Table 2.

Table 2.

Output of generalized linear model for individual and interactive effects of MeJA, bacteria, bacteria and MeJA, and time (1, 3, and 7 days after treatment) after treatments on foliage isoprene emission rate in E. grandis. Stress application protocol and the baseline environmental conditions during measurements as in Fig. 1. P values show the significance of wald chi-square (χ2) statistics.

| Compounds | Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | P value | ||

| Isoprene | MeJA | 0.119 | 1 | 0.730 |

| Bacteria | 15.696 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.159 | 1 | 0.690 | |

| Time | 7.573 | 1 | 0.006** | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.369 | 1 | 0.242 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.337 | 1 | 0.248 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 3.002 | 1 | 0.083 | |

3.3. Temporal changes of individual LOX pathway volatiles in response to MeJA and bacterial treatments

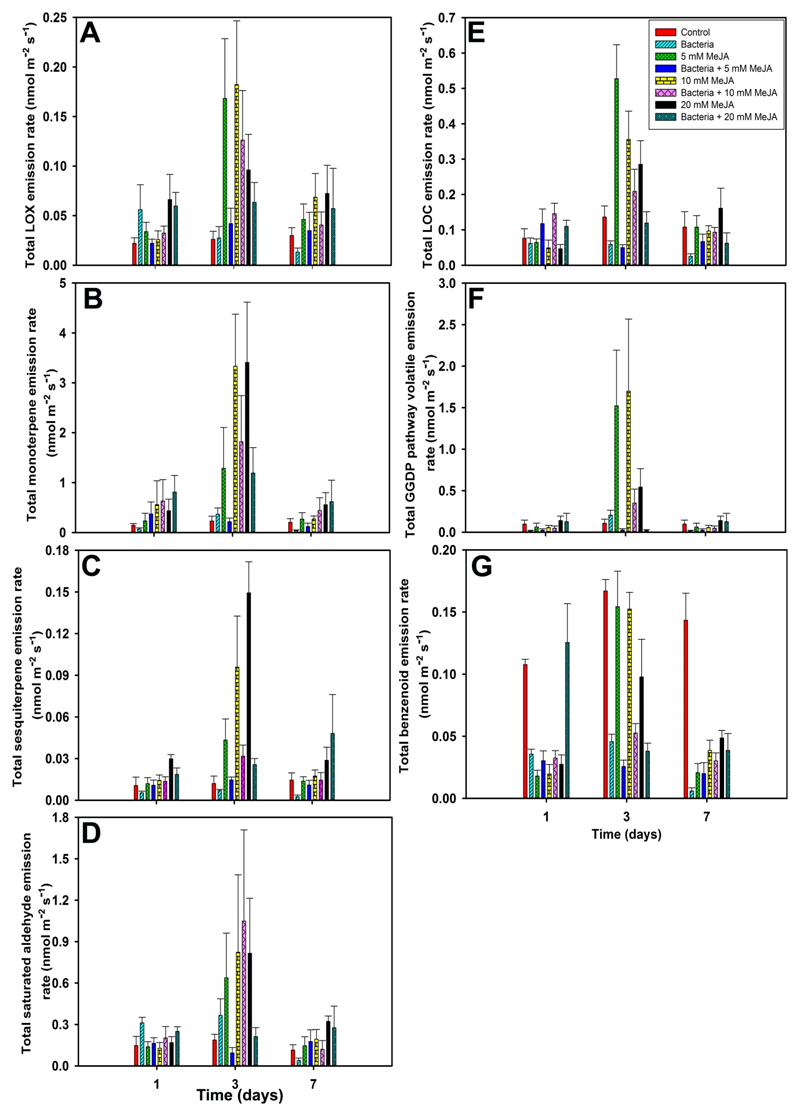

The emission rate of total LOX pathway volatiles in control leaves was in the range of 0.02-0.03 nmol m-2 s-1 (Fig. 3A). However, bacterial inoculation increased total LOX volatile emission at day 1 and then it started decreasing in a time-dependent manner at day 3 and day 7 (Fig. 3A). In addition, the emission rate of total LOX pathway volatiles was exponentially enhanced when the leaves were subjected to separate MeJA (P < 0.001, Table 3), followed by combined bacterial and MeJA applications. At day 1 and 7, total LOX pathway volatile emission scaled positively with MeJA dose (Fig. 3A). Generally, the emission rates of total LOX pathway volatiles were higher at day 3 after stress applications (ca. 5-fold increment for separate MeJA treatments and ca. 2-fold increment for combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, compared to controls), where the highest emission was observed in response to 10 mM MeJA treatment. A greater share of total LOX emission blend remained almost higher at all times after stress application due to the sustained emission rates of hexanal and pentanal (Fig. 3A and Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Temporal variation in emission rates (Mean + SE) of total lipoxygenase pathway (LOX pathway or GLV, green leaf volatiles) volatiles (A), monoterpenes (B), sesquiterpenes (C), saturated aldehydes (D), light weight oxygenated compounds (LOC) (E), geranyl geranyl diphosphate (GGDP) pathway volatiles (F), and benenoids (G) from E. grandis leaves response to control, bacterial inoculation, MeJA treatments (5, 10, and 20 mM), and bacterial and MeJA treatments (first inoculated with bacteria, followed by 5, 10, and 20 mM MeJA treatments) at 1, 3, and 7 days after treatments. Details of treatments and replications, and standard environmental conditions during measurements as in Fig. 1. Details of statistical analysis as in Table 3.

Table 3.

Output of generalized linear model for individual and interactive effects of MeJA, bacteria, MeJA and bacteria, and time (1, 3, and 7 days after treatment) after treatments on total volatile emission rates of various volatile classes emitted by E. grandis leaves. Stress application protocol and the baseline environmental conditions during measurements as in Fig. 1. P values show the significance of wald chi-square (χ2) statistics.

| Compounds | Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | P value | ||

| Total LOX volatiles | MeJA | 11.559 | 1 | 0.001*** |

| Bacteria | 2.892 | 1 | 0.089 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.022 | 1 | 0.082 | |

| Time | 0.754 | 1 | 0.385 | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.270 | 1 | 0.260 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 7.431 | 1 | 0.006** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 2.169 | 1 | 0.141 | |

| Total monoterpenes | MeJA | 12.588 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 14.183 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 12.745 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 3.718 | 1 | 0.050* | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.264 | 1 | 0.607 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.206 | 1 | 0.650 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.476 | 1 | 0.490 | |

| Total sesquiterpenes | MeJA | 49.998 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 29.431 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 12.322 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 0.221 | 1 | 0.639 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.485 | 1 | 0.486 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 5.482 | 1 | 0.019* | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.030 | 1 | 0.863 | |

| Total saturated aldehydes | MeJA | 6.391 | 1 | 0.011* |

| Bacteria | 0.023 | 1 | 0.878 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 2.191 | 1 | 0.139 | |

| Time | 6.186 | 1 | 0.013* | |

| MeJA x Time | 4.719 | 1 | 0.030* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 9.702 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.074 | 1 | 0.786 | |

| Total light-weight oxygenated volatiles (LOC) | MeJA | 4.239 | 1 | 0.040* |

| Bacteria | 12.426 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.051 | 1 | 0.821 | |

| Time | 0.608 | 1 | 0.436 | |

| MeJA x Time | 6.668 | 1 | 0.010** | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.669 | 1 | 0.196 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.758 | 1 | 0.185 | |

| Total GGDP volatiles | MeJA | 9.523 | 1 | 0.002** |

| Bacteria | 0.084 | 1 | 0.772 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.538 | 1 | 0.463 | |

| Time | 6.384 | 1 | 0.012* | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.131 | 1 | 0.717 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 3.841 | 1 | 0.050* | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.322 | 1 | 0.571 | |

| Total benzenoids | MeJA | 2.595 | 1 | 0.107 |

| Bacteria | 6.628 | 1 | 0.107 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.074 | 1 | 0.785 | |

| Time | 9.919 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| MeJA x Time | 8.298 | 1 | 0.004** | |

| Bacteria x Time | 7.108 | 1 | 0.008** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.655 | 1 | 0.198 | |

The blend of LOX pathway volatiles consisted of hexanal, 2-(E)-hexenal, 3-(Z)-hexenol, and pentanal and the emission blend was dominated by pentanal, followed by hexanal upon all treatments (Fig. S1 and Table S1). In addition, separate MeJA treatments led to a stronger LOX volatile emission rates, followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments at day 3. However, the emission of classical LOX pathway volatiles, (E)-2-hexenal and (Z)-3-hexenol, tended to peak for 20 mM MeJA treatment at day-1 after treatments and then started declining. The separate application of MeJA had a statistically significant impact on hexanal and pentanal emissions, whereas bacterial treatment alone and combined application of bacteria and MeJA had a statistically significant impact on (E)-2-hexenal and (Z)-3-hexenol emissions (P < 0.05, Table S1). In addition, (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate emission was also observed at trace levels upon separate MeJA treatments (data not shown).

3.4. Time-dependent regulation of foliage mono-and sesquiterpene emissions upon MeJA and bacterial treatments

Eucalyptus grandis is a low-level mono- and sesquiterpene emitter under non-stressed conditions. The total average emission rate of monoterpenes by control leaves was varied between 0.14 - 0.23 nmol m-2 s-1 (Fig. 3B). Generally, bacterial inoculation decreased total mono- and sesquiterpenes in a time-dependent manner, compared to controls (Fig. 3B and 3C, P < 0.001 for bacterial inoculation alone, Table 3). However, the emission rate peaked when leaves were subjected to separate MeJA treatments (ca. 12-fold increment compared to controls for 20 mM MeJA at day 3), followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments at day 3 (ca. 6-fold increment compared to controls for a combined application of bacteria and 10 mM MeJA at day 3) (P < 0.001 for separate and combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, Table 3).

Eucalyptus grandis leaves emitted fifteen monoterpenes (Fig. S2). The blend of monoterpenes was dominated by 1,8-cineole (ca. 20 % of total monoterpenes), followed by α-pinene (ca. 13 % of total monoterpenes) and p-cymene (ca. 10 % of total monoterpenes). Generally, the separate MeJA treatments resulted in a greater impact on individual monoterpene emission rates, followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. S2 and Table S1). In addition, classical stress-induced monoterpenes (E)-β-ocimene, and (Z)-β-ocimene were also observed in this study (Fig. S2J and S2K). In fact, the emission rates of both (E)-β-ocimene, and (Z)-β-ocimene were higher for separate MeJA treatments than for combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (P < 0.001 for separate MeJA, and combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, Table S1). In our study, emission responses of linalool were scattered (emission rate ranging between 3-13 pmol m-2 s-1, data not shown) and detected only from the leaves treated with combined bacterial and MeJA at day 1 after treatments.

Separate and combined MeJA and bacterial treatments significantly impacted the timing of monoterpene emission responses. In general, there were four types of emission kinetics observed for monoterpene emissions. In the case of m-cymene (Fig. S2E), p-cymene (Fig. S2F), limonene (Fig. S2G), the emission responses remained almost the same throughout all times after treatments. For 1,8-cineole (Fig. S2D), 1,3,8-p-menthatriene (Fig. S2H) and β-myrcene (Fig. S2I), the emission rates increased to the maxima at day 1 and day 3, and then decreased to the minima at day 7 after treatments. However, for α-phellandrene (Fig. S2L), the emission rate was the highest at day 1 and day 7, and the lowest at day 3 after treatments. For all other monoterpenes, the emissions achieved the maxima at day 3 and minima at day 1 and 7 after treatments.

The average total sesquiterpene emission of control leaves was 0.010-0.014 nmol m-2 s-1 (Fig. 3C). Similar to the dynamics of total monoterpenes, the emission rate of total sesquiterpene was progressively enhanced by separate MeJA treatments (ca. 8-fold increment compared to controls controls for 20 mM MeJA at day 3), followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments at day 3 (ca. 4-fold increment compared to controls a combined application of bacteria and 10 mM MeJA at day 3) (P < 0.001 for separate and combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, Table 3). There were five sesquiterpenes emitted in this study, of which the emission was dominated by α-copaene (ca. 60% of total sesquiterpenes), followed by Δ-cadinene (ca. 30% of total sesquiterpenes) (Fig. S3). Similar to the emission pattern of most of the monoterpenes, the leaves subjected to separate MeJA treatments significantly increased all sesquiterpenes, followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. S3, and Table S1). However, the elicitation of Δ-cadinene was the highest, followed by α-copaene and longifolene. In addition, the leaves treated with bacteria alone suppressed the emission rates of sesquiterpenes, compared to controls (Fig. 3C). In the case of individual sesquiterpenes, there were two different types of emission kinetics observed. The emission responses remained almost the same throughout stressed-period for Δ-cadinene, β-farnesene, and longifolene (Fig. S3B, S3D, and S3E). In the case of alloaromadendrene and α-copaene (Fig. S3A and S3C), the emissions were peaked at day 3 and remained minimum at day 1 and 7 after treatments. Generally, the emission rates of total mono- and sesquiterpenes were scaled with the severity of stress applications (Fig. 3B and 3C).

3.5. Quantitative estimation of foliage terpene contents

There were 23 monoterpenes and 17 sesquiterpenes were detected in the storage structures of E. grandis leaves (Table 4). The storage pool of monoterpenes was dominated by 1, 8-cineole and the sesquiterpenes were dominated by aromadendrene. The monoterpenes (Z)-allo-ocimene, m-cymene, (E)-β-ocimene, and (Z)-β-ocimene, and the sesquiterpenes (E)-β-farnesene and longifolene were observed in the headspace collection of volatile blends, but not in the foliage storage structures (Fig. S2 and S3, and Table 4).

Table 4.

Output of generalized linear models for individual and interactive effects of MeJA, bacteria, bacteria and MeJA and time (1, 3, and 7 days after treatment) after treatments on individual volatiles emitted by E. grandis leaves.

| Compounds | Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | P value | ||

|

LOX volatiles Hexanal |

MeJA | 4.604 | 1 | 0.032* |

| Bacteria | 8.855 | 1 | 0.003** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.322 | 1 | 0.571 | |

| Time | 0.730 | 1 | 0.393 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.232 | 1 | 0.630 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.733 | 1 | 0.188 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.652 | 1 | 0.419 | |

| (E)-2-Hexenal | MeJA | 0.197 | 1 | 0.657 |

| Bacteria | 6.056 | 1 | 0.014* | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 6.725 | 1 | 0.010** | |

| Time | 17.945 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.320 | 1 | 0.251 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 6.981 | 1 | 0.008** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 6.906 | 1 | 0.009** | |

| (Z)-3-Hexenol | MeJA | 0.011 | 1 | 0.915 |

| Bacteria | 5.375 | 1 | 0.020* | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 5.837 | 1 | 0.016* | |

| Time | 13.451 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.650 | 1 | 0.420 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 5.944 | 1 | 0.015* | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 7.489 | 1 | 0.006** | |

| Pentanal | MeJA | 9.349 | 1 | 0.002** |

| Bacteria | 2.220 | 1 | 0.136 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.301 | 1 | 0.069 | |

| Time | 0.151 | 1 | 0.698 | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.564 | 1 | 0.211 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 2.405 | 1 | 0.121 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.655 | 1 | 0.418 | |

|

Monoterpenes (Z)-allo-ocimene |

MeJA | 19.253 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 11.088 | 1 | 0.001*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 10.542 | 1 | 0.001*** | |

| Time | 9.135 | 1 | 0.003** | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.511 | 1 | 0.219 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.010 | 1 | 0.315 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 4.297 | 1 | 0.038* | |

| Camphene | MeJA | 0.774 | 1 | 0.379 |

| Bacteria | 17.588 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.309 | 1 | 0.579 | |

| Time | 7.340 | 1 | 0.007** | |

| MeJA x Time | 4.059 | 1 | 0.044* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 16.045 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 2.901 | 1 | 0.089 | |

| Δ3-Carene | MeJA | 4.137 | 1 | 0.042* |

| Bacteria | 0.513 | 1 | 0.474 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.465 | 1 | 0.495 | |

| Time | 2.753 | 1 | 0.097 | |

| MeJA x Time | 2.269 | 1 | 0.132 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.696 | 1 | 0.404 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 6.376 | 1 | 0.012* | |

| 1,8-Cineole | MeJA | 5.391 | 1 | 0.020* |

| Bacteria | 3.841 | 1 | 0.050* | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.174 | 1 | 0.075 | |

| Time | 0.120 | 1 | 0.729 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.520 | 1 | 0.471 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.007 | 1 | 0.933 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 2.176 | 1 | 0.140 | |

| m-Cymene | MeJA | 3.291 | 1 | 0.070 |

| Bacteria | 0.616 | 1 | 0.433 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.288 | 1 | 0.591 | |

| Time | 9.198 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.119 | 1 | 0.730 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 2.700 | 1 | 0.100 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.810 | 1 | 0.179 | |

| p-Cymene | MeJA | 0.469 | 1 | 0.493 |

| Bacteria | 14.038 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 6.576 | 1 | 0.010** | |

| Time | 6.998 | 1 | 0.008** | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.128 | 1 | 0.288 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.196 | 1 | 0.658 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.287 | 1 | 0.592 | |

| Limonene | MeJA | 0.592 | 1 | 0.442 |

| Bacteria | 4.406 | 1 | 0.036* | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 5.034 | 1 | 0.025* | |

| Time | 1.322 | 1 | 0.250 | |

| MeJA x Time | 2.597 | 1 | 0.107 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 2.546 | 1 | 0.111 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 2.952 | 1 | 0.086 | |

| 1,3,8-p-Menthatriene | MeJA | 32.373 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 34.725 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 16.355 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 4.986 | 1 | 0.026* | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.004 | 1 | 0.947 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 3.177 | 1 | 0.075 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 9.673 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| β-Myrcene | MeJA | 2.377 | 1 | 0.123 |

| Bacteria | 2.415 | 1 | 0.120 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 9.725 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| Time | 1.157 | 1 | 0.282 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.342 | 1 | 0.559 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.414 | 1 | 0.520 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 7.148 | 1 | 0.008** | |

| (E)-β-Ocimene | MeJA | 18.737 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 8.560 | 1 | 0.003** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 26.540 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 0.228 | 1 | 0.633 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.798 | 1 | 0.372 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.085 | 1 | 0.771 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.375 | 1 | 0.540 | |

| (Z)-β-Ocimene | MeJA | 43.197 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 25.608 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 23.919 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 14.054 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.322 | 1 | 0.570 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 3.265 | 1 | 0.071 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 2.458 | 1 | 0.117 | |

| α-Phellandrene | MeJA | 8.484 | 1 | 0.004** |

| Bacteria | 4.186 | 1 | 0.041* | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.332 | 1 | 0.068 | |

| Time | 36.873 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.424 | 1 | 0.515 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.210 | 1 | 0.647 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.051 | 1 | 0.305 | |

| α-Pinene | MeJA | 2.082 | 1 | 0.149 |

| Bacteria | 2.429 | 1 | 0.119 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.270 | 1 | 0.603 | |

| Time | 0.344 | 1 | 0.557 | |

| MeJA x Time | 5.868 | 1 | 0.015* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.369 | 1 | 0.544 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.694 | 1 | 0.405 | |

| β-Pinene | MeJA | 0.515 | 1 | 0.473 |

| Bacteria | 0.172 | 1 | 0.678 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.011 | 1 | 0.915 | |

| Time | 1.156 | 1 | 0.282 | |

| MeJA x Time | 7.973 | 1 | 0.005** | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.503 | 1 | 0.478 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.658 | 1 | 0.417 | |

| γ-Terpinene | MeJA | 5.767 | 1 | 0.016* |

| Bacteria | 2.047 | 1 | 0.152 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 11.595 | 1 | 0.001*** | |

| Time | 0.649 | 1 | 0.421 | |

| MeJA x Time | 2.445 | 1 | 0.118 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.012 | 1 | 0.912 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.929 | 1 | 0.165 | |

|

Sesquiterpenes Alloaromadendrene |

MeJA | 0.192 | 1 | 0.661 |

| Bacteria | 0.104 | 1 | 0.748 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.109 | 1 | 0.742 | |

| Time | 0.677 | 1 | 0.411 | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.113 | 1 | 0.291 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 2.051 | 1 | 0.152 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.159 | 1 | 0.690 | |

| Δ-Cadinene | MeJA | 58.936 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 67.744 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 40.024 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 0.022 | 1 | 0.882 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.146 | 1 | 0.702 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.001 | 1 | 0.971 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.062 | 1 | 0.804 | |

| α-Copaene | MeJA | 3.687 | 1 | 0.055 |

| Bacteria | 29.741 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.217 | 1 | 0.073 | |

| Time | 2.372 | 1 | 0.124 | |

| MeJA x Time | 3.608 | 1 | 0.058 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.881 | 1 | 0.170 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 4.338 | 1 | 0.037* | |

| (E)-β-Farnesene | MeJA | 61.511 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 57.718 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 2.777 | 1 | 0.096 | |

| Time | 5.936 | 1 | 0.015* | |

| MeJA x Time | 4.579 | 1 | 0.032* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 6.067 | 1 | 0.014* | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 4.331 | 1 | 0.037* | |

| Longifolene | MeJA | 0.502 | 1 | 0.478 |

| Bacteria | 0.064 | 1 | 0.800 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.220 | 1 | 0.639 | |

| Time | 0.860 | 1 | 0.354 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.117 | 1 | 0.733 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.735 | 1 | 0.188 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 3.611 | 1 | 0.057 | |

|

Saturated aldehydes Decanal |

MeJA | 6.478 | 1 | 0.011* |

| Bacteria | 0.201 | 1 | 0.654 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.499 | 1 | 0.480 | |

| Time | 9.340 | 1 | 0.002** | |

| MeJA x Time | 2.785 | 1 | 0.095 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 7.211 | 1 | 0.007** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.014 | 1 | 0.904 | |

| Heptanal | MeJA | 4.182 | 1 | 0.041* |

| Bacteria | 0.784 | 1 | 0.376 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.909 | 1 | 0.340 | |

| Time | 2.134 | 1 | 0.144 | |

| MeJA x Time | 4.887 | 1 | 0.027* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 9.048 | 1 | 0.003** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 2.188 | 1 | 0.139 | |

| Nonanal | MeJA | 6.345 | 1 | 0.012* |

| Bacteria | 0.103 | 1 | 0.748 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 4.790 | 1 | 0.029* | |

| Time | 4.797 | 1 | 0.029* | |

| MeJA x Time | 6.617 | 1 | 0.01* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 10.873 | 1 | 0.001** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.154 | 1 | 0.695 | |

| Octanal | MeJA | 3.918 | 1 | 0.048* |

| Bacteria | 0.290 | 1 | 0.590 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 1.656 | 1 | 0.198 | |

| Time | 3.046 | 1 | 0.081 | |

| MeJA x Time | 4.445 | 1 | 0.035* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 8.211 | 1 | 0.004** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.436 | 1 | 0.509 | |

|

Lightweight oxygenated compounds (LOC) Acetaldehyde |

MeJA | 2.186 | 1 | 0.139 |

| Bacteria | 22.125 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 3.283 | 1 | 0.070 | |

| Time | 0.425 | 1 | 0.515 | |

| MeJA x Time | 17.979 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Bacteria x Time | 3.358 | 1 | 0.067 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 8.281 | 1 | 0.004** | |

| Acetone | MeJA | 3.559 | 1 | 0.059 |

| Bacteria | 7.298 | 1 | 0.007** | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 1.185 | 1 | 0.276 | |

| Time | 0.207 | 1 | 0.649 | |

| MeJA x Time | 2.832 | 1 | 0.092 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.224 | 1 | 0.269 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.253 | 1 | 0.615 | |

|

GGDP pathway volatiles (Z)-Geranyl acetone |

MeJA | 10.026 | 1 | 0.002** |

| Bacteria | 1.245 | 1 | 0.265 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.094 | 1 | 0.760 | |

| Time | 7.960 | 1 | 0.005** | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.852 | 1 | 0.356 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 2.304 | 1 | 0.129 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.218 | 1 | 0.640 | |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | MeJA | 0.008 | 1 | 0.930 |

| Bacteria | 1.137 | 1 | 0.286 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 15.766 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| Time | 0.278 | 1 | 0.598 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.827 | 1 | 0.363 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 3.728 | 1 | 0.050* | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 10.394 | 1 | 0.001*** | |

|

Benzenoids Benzaldehyde |

MeJA | 12.758 | 1 | 0.000*** |

| Bacteria | 2.394 | 1 | 0.122 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 7.300 | 1 | 0.007** | |

| Time | 4.253 | 1 | 0.039* | |

| MeJA x Time | 4.083 | 1 | 0.043* | |

| Bacteria x Time | 12.295 | 1 | 0.000*** | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.259 | 1 | 0.611 | |

| o-Xylene | MeJA | 4.074 | 1 | 0.044** |

| Bacteria | 3.325 | 1 | 0.068 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.051 | 1 | 0.821 | |

| Time | 1.469 | 1 | 0.225 | |

| MeJA x Time | 0.421 | 1 | 0.516 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 3.724 | 1 | 0.050* | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 0.291 | 1 | 0.589 | |

| p-Xylene | MeJA | 2.741 | 1 | 0.098 |

| Bacteria | 0.968 | 1 | 0.325 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 10.746 | 1 | 0.001*** | |

| Time | 0.004 | 1 | 0.947 | |

| MeJA x Time | 1.808 | 1 | 0.179 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 0.403 | 1 | 0.525 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.249 | 1 | 0.264 | |

| Toluene | MeJA | 0.627 | 1 | 0.429 |

| Bacteria | 0.647 | 1 | 0.421 | |

| Bacteria + MeJA | 0.154 | 1 | 0.694 | |

| Time | 3.683 | 1 | 0.055 | |

| MeJA x Time | 2.343 | 1 | 0.126 | |

| Bacteria x Time | 1.574 | 1 | 0.210 | |

| (Bacteria + MeJA) x Time | 1.185 | 1 | 0.276 | |

Stress application protocol and the baseline environmental conditions during measurements as in Figure 1. P values show the significance of wald chi-square (χ2) statistics.

3.6. Impact of MeJA and bacterial treatments on temporal emission dynamics of saturated aldehydes

The emission rate of total saturated aldehyde was higher for all treatment effects with a progressive impact on day 3 after separate and combined applications of bacterial and MeJA (Fig. 3D, Table 3). In particular, the emission rate peaked by MeJA treatment alone (P < 0.001 for MeJA treatments, Table 3), followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, and bacterial treatment alone.

In this study, the pool of saturated aldehydes emitted was comprised of decanal, heptanal, nonanal, and octanal (Fig. S4, and Table S1). Similar to the emission kinetics of LOX volatiles, hexanal and pentanal (Fig. S1A and S1D), the inoculation with bacteria enhanced the emission rates of all saturated aldehydes, compared to controls (Fig. S4, and Table S1). However, the separate application of MeJA resulted in the highest emission burst of decanal and combined application of bacteria and MeJA led to the highest emission rates of heptanal, nonanal, and octanal particularly at day 3 after stress applications (P < 0.05 for separate MeJA treatments, Table S1). All saturated aldehydes demonstrated emission maxima at day 3 and minima at day 1 and 7 after treatments.

3.7. Emission trends in LOC, GGDP pathway volatiles, and benzenoids in MeJA and bacterial treatments and at different times after treatments

The emission rates of total LOC, benzenoids, and GGDP pathway volatiles were higher at day 3 after stress applications (Fig. 3E - 3G). In fact, bacterial inoculation decreased total LOC and GGDP pathway volatiles and increased total benzenoid emissions at all recovery phase. However, total LOC, benzenoids, and GGDP pathway volatiles were the highest when leaves were subjected to MeJA treatment alone (P < 0.05, Table 3), followed by combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. 3E - 3G).

Two LOC volatiles, acetaldehyde and acetone, were observed in the emission blend (Fig. S5A and S5B). The acetone constituted a greater share of LOC (Fig. S5B). The emission rates of acetaldehyde and acetone were decreased in response to bacterial inoculation at all recovery phase, compared to controls (P < 0.01 for bacteria, Table S1). Acetone emission responses tended to peak for separate MeJA treatments, compared to combined bacterial and MeJA treatments (Fig. S5B). In the case of acetaldehyde, surprisingly the emission tended to peak upon combined application of bacteria and MeJA at day 1 (Fig. S5A). Regarding the emission kinetics, the kinetics of acetaldehyde was remained the same through the different times of measurements after treatments, but in the case of acetone, the emission achieved to the maximum at day 3 after measurements and remained minimum at day 1 and 7 after treatments.

There were two compounds detected under the category of GGDP pathway volatiles, (Z)-geranyl acetone and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one (Fig. S5C and S5D, Table S1). Inoculation of bacteria alone led to enhanced emission rates of GGDP pathway volatiles till day 3 after stress applications and then to decreased emission rates, compared to controls. In fact, the emission rates of (Z)-geranyl acetone and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one were lower in response to combined bacterial and MeJA treatments than separate MeJA treatments at day 3 since treatments (Fig. S5C and S5D, Table S1). The combined application of bacteria and MeJA had a statistically significant impact on the emission rate of 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one (P < 0.001, Table S1). Regarding the emission kinetics of both cases, the emission achieved to the maxima at day 3 after measurements and then decayed.

The blend of benzenoid was dominated by benzaldehyde, followed by toluene, o-xylene, and p-xylene upon all treatments and through the time of measurements after treatments (Fig. S6). In the case of benzaldehyde, bacterial inoculation increased the emission responses till day 3 and then decreased it, compared to controls (Fig. S6A). In fact, benzenoid emissions were always higher for the separate application of MeJA than combined bacterial and MeJA treatments at day 3 after stress treatments (Fig. S6A, and Table S1). The highest emission of benzaldehyde was observed upon 10 mM MeJA, followed by 5 mM MeJA at day 3. Regarding the emission kinetics of p-xylene, application of bacteria inoculation ceased the emission throughout the stressed-phase (Fig. S6C). In the case of toluene emission, all treatments lowered the emission responses, compared to controls in different times after treatments; however, more severe decline was observed in response to combined bacterial and MeJA treatment than MeJA treatment alone particularly at day 3 after treatments (Fig. S6D).

3.8. Overall changes in the emission blend in response to various treatments

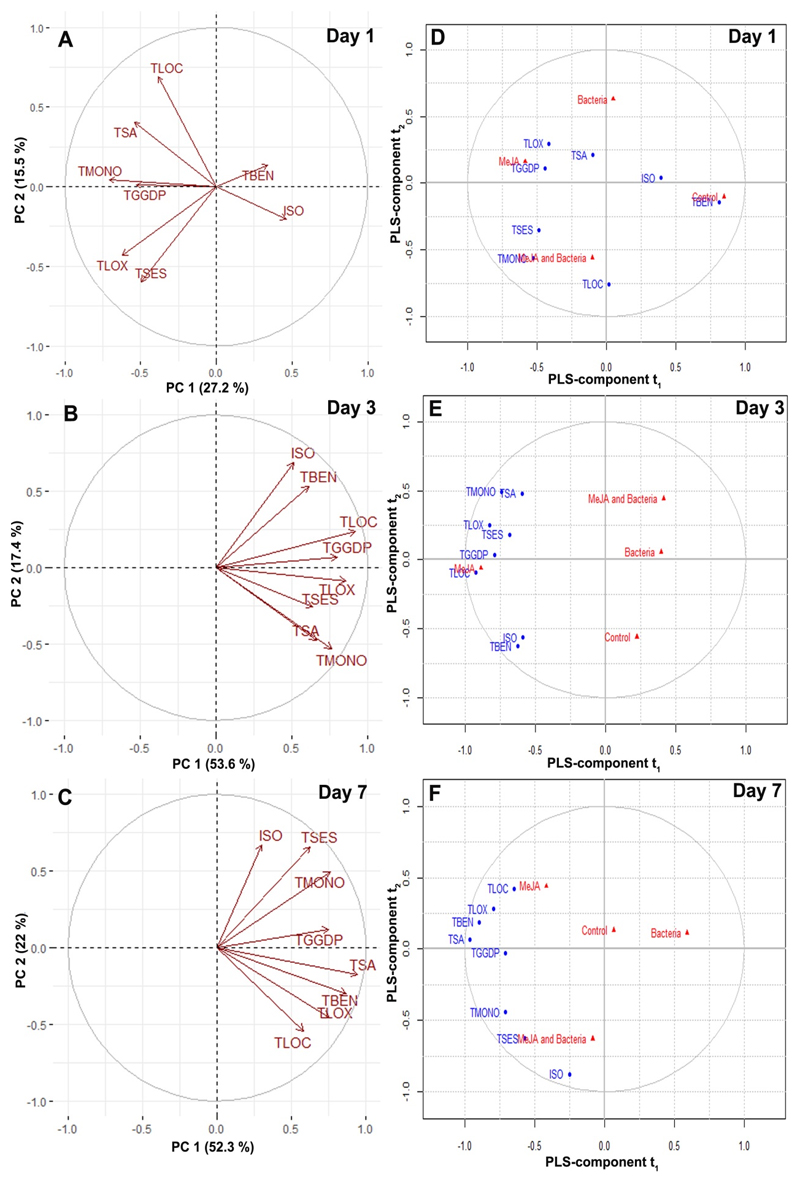

PCA analysis indicated that the first two principal components, PC1 and PC2, explained 40-80 % of the total variation in all cases (Fig. 4A, B, and C). The distribution of volatile compounds in the PCA loading plots from untreated and treated leaves showed highly quantitative variations in the volatile emission blends. In particular, isoprene and total benzenoid emission rates were negatively correlated with all other classes of compound emission at day 1, and this trend was changed in day 3 and day 7 after treatments, where all volatile classes were positively correlated (Fig. 4A, B, and C). In fact, the total monoterpene emission rate was strongly correlated with the emission rate of total GGDP pathway volatiles in day 1; however, it was strongly correlated with the emission rate of total saturated aldehydes in day 3, and total sesquiterpenes in day 7 after treatments. Furthermore, isoprene emission rates were strongly correlated with the total emission rates of benzenoids at day 1 and day 3, but it was strongly correlated with total sesquiterpene in day 7. Furthermore, the discriminant analysis based on PLS further indicates the influence of particular terpenes on the differences in the overall volatile blend upon different treatments (Fig. 4C, D, and E). In fact, MeJA treatment was highly influenced by total LOX, GGDP pathway volatiles, and saturated aldehydes at day 1, and it was highly influenced by total LOC at day 3, and total LOX, LOC, benzenoids, and saturated aldehydes at day 7. Bacterial inoculation was particularly influenced by isoprene at day 1 and none of the specific compounds at day 3 and day 7. However, combined application of MeJA and bacteria was highly influenced by total mono- and sesquiterpenes at day 1 and day 7, and it was not influenced by any compounds at day 3 after treatments. The association of other classes of volatiles to a particular treatment depended on the temporal variation of volatiles upon treatments and various controls (Fig. 4C, D, and E).

Figure 4.

Loading plots (A, B, and C) of principal component analysis (PCA) of emission rates of foliage isoprene and other classes of total VOCs in E. grandis leaves in response to control, bacterial inoculation, MeJA treatments, and bacteria and MeJA treatments (first inoculated with bacteria, followed by MeJA treatments) at 1, 3, and 7 days after treatments. Loading plots (C, D, and E) of partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of isoprene and other classes of total VOCs in E. grandis leaves upon control, bacterial inoculation, MeJA treatments, and bacteria and MeJA treatments. The triangles represent the loading score for different treatments. Details of stress applications as in Figure 1. Details of isoprene and total volatile emissions as in Figure 2 and 3. Abbreviations represent different volatile classes as follows: ISO- isoprene, TLOX - total LOX, TMONO - total monoterpenes, TSES - total sesquiterpenes, TSA - total saturated aldehydes, TLOC- total lightweight oxygenated volatile compounds, TGGDP - total GGDP pathway volatiles, and TBEN - total benzenoids.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of MeJA and bacterial treatments on time-dependent changes in photosynthetic traits

In the present study, inoculation by endophytic PGPR, B. vietnamiensis, alone reduced stomatal conductance to water vapor by 60-70% compared to controls and in turn, reduced net assimilation rate (Fig. 1B and 1C). The reduction in net assimilation rate is due to the reduction in foliage stomatal conductance upon PGPR inoculation as an adoptive mechanism to increase foliage water-content under stress as reported by Benabdellah et al. (2011). In our study, this phenomenon was further confirmed by the sustained reduction of intercellular CO2 concentration (Fig. 1B - 1D). Therefore, this phenomenon implies that foliage application of B. vietnamiensis would have increased the leaf-water content in E. grandis leaves, compared to non-inoculated leaves. However, exogenous MeJA applications considerably reduced photosynthetic traits, compared to controls and the reductions were quantitatively associated with the severity of stress applications (Fig. 1). Generally, a decline in maximum dark-adapted photosystem II (PSII) quantum yield estimated by chlorophyll florescence (Fv/Fm) upon MeJA treatments is a typical stress response and a sensitive indicator of the stress-induced damage in PSII reaction centers (Wierstra and Kloppstech, 2000). In this work, higher doses of MeJA likely caused hypersensitive reactions and severe stress-induced perturbations in photosynthetic machinery, eventually leading to a sustained decline in photosynthetic characteristics. Our findings are consistent with previous reports stating that energy dissipation activity and PSII efficiency were dramatically decreased upon elevated MeJA applications (Wierstra and Kloppstech, 2000). In addition, elevated MeJA treatments resulted in pronounced degradation of D1 protein synthesis and a subsequent delay in the recovery rate of photosystem II activity (Wierstra and Kloppstech, 2000), ultimately leading to sustained reduction in Fv/Fm and photoinhibition (Fig. 1A and 1B).

In our study, higher doses of MeJA likely caused: (1) irreversible damage in thylakoid membranes as a result of hypersensitive reactions (Kohlmann et al., 1999), (2) downregulation of photosynthetic protein biosynthesis and the expression profiles of nuclear and plastid photosynthetic genes encoding essential photosynthetic proteins (Wierstra and Kloppstech, 2000), and (3) a reduced biosynthesis and activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), a key enzyme in Calvin cycle (Rodrigues Cavalcante et al., 1999), eventually leading to a sustained reduction in foliage photosynthesis. Furthermore, acute MeJA treatments generates inhibitory effect on guard cells and reduced stomatal movements due to enhanced production of ROS and abscisic acid, which is also associated with reduced photosynthesis (Zhu et al., 2012) (Fig. 1B and 1C). Thus, these reports conclusively establish that the exposure of elevated MeJA in E. grandis leaves simultaneously triggered multiple biochemical and non-biochemical mechanisms, associated with a progressive reduction in photosynthetic characteristics (Fig. 1). Similar to our findings, biotic stresses reduced photosynthetic traits, including leaf rust infection in willow (Salix burjatica x S. dasyclados) (Toome et al., 2010), oak powdery mildew (Erysiphe alphitoides) infection in pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) leaves (Copolovici et al., 2014b), infection of rust fungus (Melampsora larici-populina) in poplar (Populus balsamifera var. suaveolens) leaves (Jiang et al., 2016), larvae of green alder sawfly (Monsoma pulveratum) feeding on European alder (Alnus glutinosa) leaves.

We demonstrated that inoculation by endophytic bacteria B. vietnamiensis significantly protected the photosynthetic machinery upon subsequent application of MeJA treatments (Fig. 1), possibility due to enhanced production of indole acetic acid associated with increased production of chlorophyll contents as observed by Onofre-Lemus et al. (2009) for tomato plants treated with PGPR B. unamae. In addition, it was also evident that inoculation by a PGPR B. aquimaris upregulated relative water content, accumulation of proline, soluble sugar, activities of superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidase, and ascorbate peroxidase in maize leaves, ultimately leading to enhanced protection of photosynthetic machinery from salt stress (Li and Jiang, 2017). Thus, we suggest the similar mechanisms could be associated with B. vietnamiensis to increase the photosynthetic activity upon subsequent MeJA treatments. Importantly, B. vietnamiensis was reported to produce thiol specific antioxidants in plants (http://www.ecogene.org) that protect host-cells from hostile oxidative environments (Hyang et al., 2005). Therefore, it implies that enhanced production of thiol specific antioxidants B. vietnamiensis likely weakened hypersensitive reactions caused by elevated MeJA treatments in E. grandis leaves. However, future research is required to address the question of how B. vietnamiensis inoculation protects the integrity of photosynthetic machinery during higher MeJA treatments.

4.2. Temporal emission dynamics of isoprene upon MeJA and bacteria treatments

Given that isoprene is de novo biosynthesized via MEP pathway, the emission rate of isoprene is ultimately controlled by isoprene synthase gene expression, terminal enzyme activity and availability of substrates (Rasulov et al., 2016). However, stresses can often modify isoprene synthase gene expression, terminal enzyme activity, and the availability of substrates, ultimately leading to modification in isoprene emission responses (Niinemets, 2010). The present study illustrates that inoculation by B. vietnamiensis in E. grandis leaves decreased isoprene emission rate by 88-95 % at all times, implying that bacterial inoculation significantly altered the MEP pathway. In addition, bacterial inoculation decreased net assimilation rate by 20-50% compared to controls (Fig. 1B and 2). Thus, it seems that substrate limitation did not significantly contribute to the lower rate of isoprene emission; instead, bacterial inoculation could have downregulated terminal enzyme activities in the MEP pathway and/or isoprene synthase gene expression levels. Nevertheless, enhancement of other isoprenoid synthesis, e.g. volatile terpenoids and non-volatile terpenoids such as carotenoids can severely suppress isoprene emission because of greater affinity of these branches of terpenoid synthesis pathway to metabolic precursors (Rasulov et al., 2014; Rasulov et al., 2015).

However, bacterial inoculation declined stomatal conductance to water vapour by 60-70% compared to controls (Fig. 1C). In fact, changes in stomatal conductance do not have a significant direct impact on the changes in isoprene emission rate, due to the development of partial pressure of isoprene in leaf intercellular airspaces upon reduced stomatal conductance (Niinemets and Reichstein, 2003). However, isoprene emission can slightly be increased by moderate stomatal closure due to positive influence of enhanced intercellular CO2 concentration on isoprene emission rate (Rasulov et al., 2016; Wilkinson et al., 2009) (Fig. 1D and 2).

In all cases, foliage isoprene emission was increased in response to separate MeJA treatments, but decreased upon combined bacterial and MeJA treatments at day 3 after treatments, compared to controls (Fig. 2A). However, net assimilation rate was significantly decreased for separate MeJA and combined bacterial and MeJA treatments, compared to control. In fact, a previous study revealed that exogenous MeJA treatments did not change isoprene synthase gene expression levels in Populus alba (Sasaki et al., 2005). Therefore, our study suggests that changes in isoprene emission upon separate MeJA and combined bacterial and MeJA treatments were likely associated with the changes in isoprene synthase and other terminal enzyme activities in MEP pathway. In contrast to our findings, biotic stresses reported to downregulate isoprene emission responses. For example, isoprene emission negatively scaled with the percentage of leaf damage upon rust fungus (Melampsora larici-populina) infection of poplar (Populus balsamifera var. suaveolens) leaves (Jiang et al., 2016), oak powdery mildew (Erysiphe alphitoides) infection of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) leaves (Copolovici et al., 2014b), and leaf rust infection of willow (Salix burjatica x S. dasyclados) (Toome et al., 2010).

Surprisingly, isoprene emission was higher for combined bacterial and MeJA treatments than for separate MeJA treatments at day 7 after treatments. We argue in this particular case that B. vietnamiensis inoculation led to abolishment of hypersensitive reactions and programmed cell death to some extent, caused by lethal doses of MeJA, particularly by 20 mM MeJA (Reinbothe et al., 2009; Zhang and Xing, 2008) in E. grandis leaves. This phenomenon ultimately led to activation of MEP pathway and enhanced isoprene emission at later stages of recovery. This phenomenon was further confirmed by analogous emission rates of total mono- and sesquiterpenes for combined bacterial and 20 mM MeJA treatments at day 7 (Fig. 2, 3B and 3C). However, molecular studies of isoprene biosynthesis are required to understand the clear-cut mechanism of isoprene emission responses in this particular case.

4.3. Elicitation of LOX pathway volatiles under MeJA and bacteria treatments