Abstract

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC), a rare inherited disorder, progresses to liver failure in childhood. We have shown that sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (NaPB), a drug approved for urea cycle disorders (UCDs), has beneficial effects in PFIC. However, there is little evidence to determine an optimal regimen for NaPB therapy. Herein, a multicenter, open-label, single-dose study was performed to investigate the influence of meal timing on the pharmacokinetics of NaPB. NaPB (150 mg/kg) was administered orally 30 min before, just before, and just after breakfast following overnight fasting. Seven pediatric PFIC patients were enrolled and six completed the study. Compared with postprandial administration, an approved regimen for UCDs, preprandial administration significantly increased the peak plasma concentration and area under the plasma concentration-time curve of 4-phenylbutyrate by 2.5-fold (95% confidential interval (CI), 2.0–3.0;P = 0.003) and 2.4-fold (95% CI, 1.7–3.2;P = 0.005). The observational study over 3 years in two PFIC patients showed that preprandial, but not prandial or postprandial, oral treatment with 500 mg/kg/day NaPB improved liver function tests and clinical symptoms and suppressed the fibrosis progression. No adverse events were observed. Preprandial oral administration of NaPB was needed to maximize its potency in PFIC patients.

Subject terms: Clinical pharmacology, Liver diseases, Paediatric research

Introduction

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) is an autosomal recessive inherited liver disease. Intractable itching, jaundice, and growth retardation due to persistent intrahepatic cholestasis appear during infancy in patients with PFIC. Its exact prevalence is unknown, but it is estimated to be between 1 in 50,000 and 1 in 100,000 births1,2. This disease is classified into five types (PFIC1–5) according to gene that causes the disease1–6. PFIC1 and 2 are predominant subtypes of PFIC with normal levels of serum gamma glutamyl transferase (normal-GGT PFIC). These subtypes have a genetic deficiency in the ATP8B1 and ABCB11, which encode an aminophospholipid flippase expressed in many tissues and a bile salt export pump (BSEP) that mediates the biliary excretion of bile acids from hepatocytes, respectively2,3,6.

Normal-GGT PFIC progresses to liver failure and death before adulthood7,8. No effective medical therapy for this disease is currently available8. Even liver transplantation is insufficient to overcome normal-GGT PFIC because of ongoing graft steatosis and fibrosis in PFIC19 and recurrent graft failure in some patients with PFIC210–12. We and other groups have published experimental evidence that sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (NaPB), a drug approved for treating urea cycle disorders (UCDs), has another newly identified pharmacological effect: it increases the hepatocanalicular expression of BSEP13–15. Furthermore, our group and Gonzales et al. showed that treatment with NaPB improved biochemical parameters and liver histology in PFIC2 patients with mutations in ABCB11 that severely affect the hepatocanalicular expression of BSEP but not its transport activity14,16–19. We also found that this drug eliminates intractable itching in patients with PFIC120 in which ATP8B1 deficiency induces a decrease in both the expression and function of BSEP21,22. However, another observational study reported that monotherapy with NaPB had little therapeutic effect in two patients with PFIC223.

The originally described pharmacological action of NaPB involves generating an alternative pathway of nitrogen deposition that replaces the urea cycle through urinary excretion of 4-phenylacetylglutamine (PAG). PAG is formed through the conjugation of glutamine with 4-phenylacetate (PA), a metabolite of 4-phenylbutyrate (PB), leading to a reduction in the plasma ammonia level. Therefore, NaPB has a beneficial effect in UCDs, which are a group of inborn errors of hepatocyte metabolism involved in urea synthesis, resulting in the accumulation of ammonia in the blood at toxic levels. NaPB therapy has been the standard treatment for the long-term management of UCDs for over 20 years. The approved regimen dictates that it is taken with or immediately after a meal24. However, this regimen is not supported by specific clinical evidence. Little information about the pharmacokinetics of NaPB, other than its metabolism and excretion pathway, is available24. Herein, we performed a multicenter, open-label, single dose study of NaPB in seven patients with normal-GGT PFIC to investigate the influence of meal timing on the pharmacokinetics (PK) of NaPB, and showed that food intake before the administration of NaPB markedly reduced the systemic exposure to PB. We then, over 27 months, assessed the optimal regimen for NaPB in the treatment of normal-GGT PFIC in two patients with PFIC2, through biochemical and liver histological analysis and safety assessments.

Results

Meal timing effect on the PK of PB

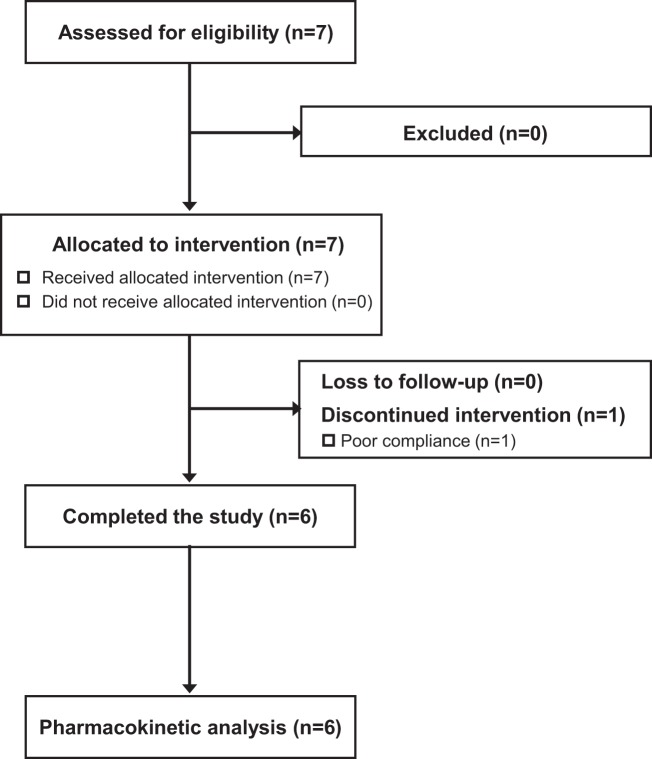

Seven patients were diagnosed with normal-GGT PFIC as described in Methods and enrolled in the PK study between November 2016 and March 2017 (Table 1). The subjects comprised three boys and four girls, and the mean ± SD values of their age, height, and body weight were 4.6 ± 2.1 years old (range, 1.5–8.0 years), 89.3 ± 13.4 cm (range, 67.3–109.2 cm), and 13.0 ± 4.0 kg (range, 6.6–19.2 kg). All except Patient 3 were Japanese. No clinically undesirable signs or symptoms attributable to the administration of NaPB were detected during the PK study. All subjects other than Patient 5 completed the study. The PK data concerning NaPB administration just after breakfast were missing in Patient 5 because he refused to take NaPB after breakfast. Therefore, his data were excluded from the PK analysis (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics.

| Diagnosis | Diagnostic findings | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFIC1 | PFIC2 | PFIC2 | PFIC2 | PFIC2 | PFIC1 | PFIC1 | PFIC1 | PFIC-like | ||

| Gene | ||||||||||

| Causal gene | ATP8B1 | ABCB11 | ABCB11 | ABCB11 | ABCB11 | ATP8B1 | ATP8B1 | ATP8B1 | ND | |

| Gene mutation | Allele 1 | ex.5c.386G>A | ex.5 c.386G>A | ex.26 c.3692G>A | ex.5 c.461_462insT | ex.25 c.3033-34del | ex.28 c.3579_3589del | ND | ||

| Allele 2 | ex.5c.386G>A | ex.14 c.1460G>A | ex.26 c.3692G>A | ex.19 c.2124_2125insGAGCTACAGCTATTGAAGGC | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age | 3y6m | 3y10m | 5y5m | 1y5m | 6y1m | 8y0m | 4y5m | |||

| Sex | Girl | Girl | Girl | Girl | Boy | Boy | Girl | |||

| Race | Japanese | Japanese | Pakistani | Japanese | Japanese | Japanese | Japanese | |||

| Body height (cm) | 78.4 | 96.9 | 88.5 | 67.3 | 91.0 | 109.2 | 94.0 | |||

| Body weight (kg) | 9.4 | 14.8 | 12.5 | 6.6 | 14.3 | 19.2 | 14.5 | |||

| Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age of onset | 2m*1 | 2m*1 | 2m | 1m | 2m | 4m | 2m | 3m | 5m | |

| Cholestasis | +[100%] | +[100%] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Intractable pruritus | +[100%]*2 | +[100%]*2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Hepatomegaly | +[100%]*2 | +[97%]*2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Jaundice | +[73%]*1 | +[70%]*1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | — | |

| Splenomegaly | +[31%]*2 | +[41%]*2 | + | + | — | — | + | — | + | |

| Gallstones | +[0%]*1 | +[32%]*1 | — | + | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Diarrhea | +[61%]*1 | +[20%]*1 | + | — | + | — | + | — | + | |

| Steatorrhea | +[NA] | +[NA] | + | + | + | — | — | — | — | |

| Sensorineural deafness | +[31%]*1 | +[0%]*1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Pneumonia | +[13%]*1 | +[1%]*1 | — | — | + | — | — | — | — | |

| Pancreatitis | +[12%]*1 | +[1%]*1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Bleeding | +[0%]*2 | +[8%]*2 | — | + | + | — | — | + | + | |

| Rickets | +[46%]*1 | +[12%]*1 | — | — | — | + | + | — | — | |

| Failure to thrive | +[90%]*1 | +[59%]*1 | + | — | + | + | + | — | + | |

| Short stature | +[NA] | +[NA] | + | — | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Weight-for-height | > Normal [NA] | > Normal [NA] | > Normal | > Normal | > Normal | < Normal | > Normal | > Normal | > Normal | |

| Mental retardation | +[NA] | +[NA] | + | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Serum assay | ||||||||||

| AST (IU/L) | Peak (age) | <2 × Normal*1, 3[NA] | Elevated*1[NA] | 1,276 (5m) | 652 (4m) | 895 (5y2m) | 163 (5m) | 128 (2y1m) | 98 (7m) | 160 (3y10m) |

| Current | 56 | 33 | 338 | 93 | 87 | 68 | 50 | |||

| ALT (IU/L) | Peak (age) | <2 × Normal*3[NA] | Elevated*3[NA] | 1,457 (5m) | 890 (4m) | 439 (6m) | 104 (1y3m) | 99 (2y3m) | 123 (7m) | 208 (3y10m) |

| Current | 46 | 19 | 155 | 84 | 44 | 76 | 55 | |||

| GGT (IU/L) | Peak (age) | Low to normal*3[NA] | Low to normal*3[NA] | 118 (1y10m) | 33 (5m) | 39 (5y1m) | 59 (1y1m) | 70 (1y1m) | 33 (6y5m) | 38 (1y11m) |

| Current | 33 | 17 | 30 | 39 | 30 | 28 | 26 | |||

| T-Bil (μmol/L) | Peak (age) | Elevated*3[NA] | Elevated*3[NA] | 178.7 (1y11m) | 105.8 (1y8m) | 196.7 (5y2m) | 200.1 (5m) | 333.5 (4m) | 388.2 (6y5m) | 8.6 (2y6m) |

| Current | 12.5 | 16.2 | 65.0 | 47.9 | 109.4 | 71.8 | 6.8 | |||

| D-Bil (μmol/L) | Peak (age) | Elevated*3[NA] | Elevated*3[NA] | 80.8 (1y11m) | 47.7 (1y8m) | 102.4 (5y2m) | 102.4 (5m) | 180.3 (4m) | 194.2 (6y5m) | 3.2 (2y6m) |

| Current | 4.4 | 4.1 | 33.1 | 21.0 | 43.6 | 32.7 | 2.1 | |||

| TBA (μmol/L) | Peak (age) | Elevated*1, 3[NA] | Elevated*1[NA] | 529.1 (1y2m) | 456.2 (1y11m) | 357.1 (5y1m) | 425 (9m) | 351.8 (2y11m) | 268.9 (4y8m) | 245.4 (4y1m) |

| Current | 297.6 | 176.7 | NA | 297.1 | 174.4 | 87.2 | 145.8 | |||

| ALP (IU/L) | Peak (age) | Normal*1[NA] | Normal (lower limit)*1[NA] | 1,956 (7m) | 2,362 (1y1m) | 3,550 (5m) | 3,206 (5m) | 3,740 (5y6m) | 3,943 (8m) | 1,575 (1y8m) |

| Current | 1,525 | 1,428 | NA | 2,296 | 2,018 | 1,253 | 1,077 | |||

| Alb (g/dL) | Nadir (age) | Low to normal*1[NA] | Low*1[NA] | 4.3 (1y3m) | 3.1 (1y8m) | 1.6 (5y1m) | 3.0 (1y1m) | 2.5 (1y1m) | 2.7 (1y6m) | 3.7 (4y5m) |

| Current | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |||

| TG (mg/dL) | Peak (age) | Elevated*1[NA] | Elevated*1[NA] | 572 (1y6m) | 314 (1y3m) | 302 (5y1m) | 319 (10m) | 455 (8m) | 358 (6y5m) | 434 (4y1m) |

| Current | 177 | 71 | — | 150 | 152 | 110 | 345 | |||

| T-Cho (mg/dL) | Peak (age) | <2 × Normal*3[NA] | <2 × Normal*3[NA] | 256 (3m) | 232 (1y8m) | 259 (5y5m) | 177 (10m) | 235 (2m) | 176 (8m) | 280 (3y2m) |

| Current | 159 | 106 | 209 | 129 | 163 | 105 | 230 | |||

| Treatment | ||||||||||

| Surgical procedure (age) | — | — | — | — | — | PIBD (1y6m) | — | |||

| Liver transplantation (age) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

Alb, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; D-Bil, direct bilirubin; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; NA, not available; ND, not detected; PIBD, partial internal biliary diversion; PFIC, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis; TBA, total bile acid; T-Bil, total bilirubin; T-Cho, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

*1: Pawlikowska L et al., J Hepatol. 2010 Jul;53(1):170–8.; *2: Davit-Spraul A et al., Hepatology. 2010 May;51(5):1645–55.; *3: Suchy FJ, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF. Liver Disease in Children, 4th edition. England: Cambridge University Press; 2014: 199–215.

Figure 1.

Eligibility and follow-up of patients in the PK study.

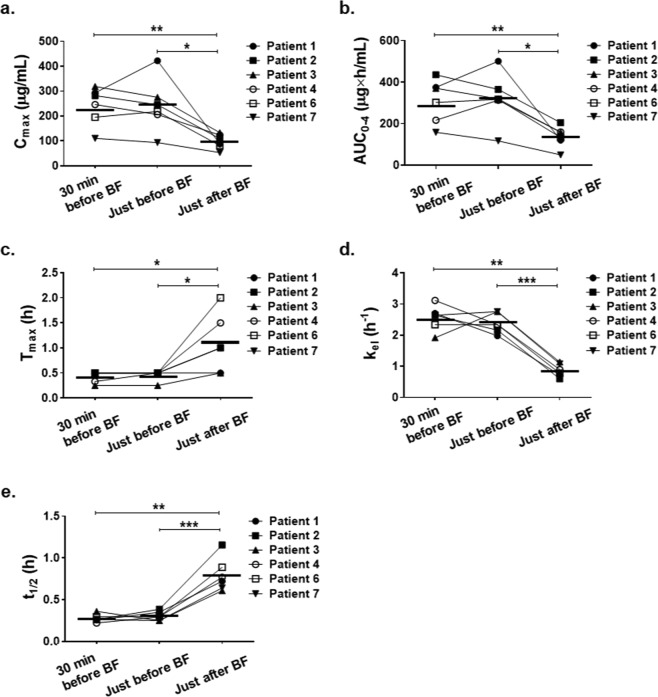

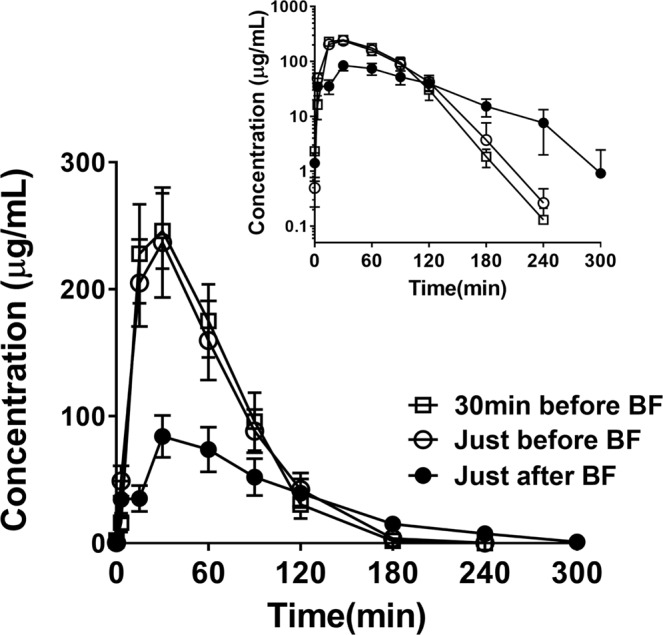

The mean plasma concentration–time curves after a single oral dose of 150 mg/kg NaPB at each time point relative to the meal are shown in Fig. 2. The PK parameters for each patient are shown in Fig. 3. Food intake before the administration of NaPB markedly reduced the plasma concentration of PB and delayed its elimination from blood. There was no significant difference between the administration of NaPB 30 min before or just before breakfast in terms of these parameters. The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of PB and the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 4 h after the administration of NaPB (AUC0–4) of PB for NaPB administration just after breakfast were 2.47 times (95% confidential interval (CI), 1.96–2.97; P = 0.003) and 2.43 times (95% CI, 1.66–3.21; P = 0.005) lower than those for administration just before breakfast, and 2.54 times (95% CI, 1.31–3.77; P = 0.029) and 2.52 times (95% CI, 1.39–3.64; P = 0.016) lower than those for administration 30 min before breakfast (Table 2). The time to reach Cmax (Tmax) of PB after postprandial administration occurred later than after preprandial administration. The elimination rate constant (kel) of PB was markedly decreased by food intake before administration of NaPB. Consequently, the elimination half-life (t1/2) of PB for administration just after breakfast was 3.25 times (95% CI, 2.09–4.41; P = 0.001) and 3.03 times (95% CI, 2.36–3.70; P < 0.001) longer than for administration just before and 30 min before breakfast, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effect of meal timing on PB systemic exposure after oral administration of NaPB in patients with normal-GGT PFIC. NaPB (150 mg/kg) was administered orally to patients with normal-GGT PFIC 30 min before, just before (<10 min), and just after (<10 min) breakfast following an overnight fast. Each regimen was separated by a washout period of more than 24 h. Plasma concentrations of PB were determined at the times shown. Data concerning all the patients excluding Patient 5, who refused to take NaPB after breakfast, are shown as means ± SEM (n = 6) of the plasma concentrations. The inset depicts the same data on a logarithmic scale. Plasma concentrations of PB at 300 min after the preprandial dosing of NaPB were below the lower limit of quantification. BF, breakfast.

Figure 3.

Effect of meal timing on the PK parameters of PB in patients with normal-GGT PFIC. The Cmax (a), AUC0–4 (b), Tmax (c), kel (d), and t1/2 (e) values of PB were calculated as described in the Methods. The plots represent these parameters for individual patients; the points representing the same patient are connected to one another by lines. The horizontal line in each column indicates the mean values. BF, breakfast. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs just after BF.

Table 2.

PK parameters of NaPB administered orally at 150 mg/kg in patients with normal-GGT PFIC.

| Regimen | 30 min before BF | Just before BF | Just after BF | 30 min before BF to just after BF | Just before BF to just after BF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | P value | Ratio | P value | ||||

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 240.8 (159.9–321.6) | 243.2 (130.7–355.8) | 97.8 (66.8–128.9) | 2.47 (1.96–2.97) | 0.003 | 2.54 (1.31–3.77) | 0.029 |

| AUC0–4 (μg×h/mL) | 309.7 (199.6–419.7) | 324.1 (191.5–456.8) | 136.5 (81.1–191.8) | 2.43 (1.66–3.21) | 0.005 | 2.52 (1.39–3.64) | 0.016 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.500 (0.250–0.500) | 0.500 (0.250–0.500) | 1.000 (0.500–2.000) | 0.500 (0.222–0.500) | 0.042 | 0.500 (0.250–0.500) | 0.028 |

| kel (h−1) | 2.56 (2.14–2.98) | 2.46 (2.20–2.72) | 0.85 (0.61–1.09) | 3.25 (2.09–4.41) | 0.001 | 3.03 (2.36–3.70) | <0.001 |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.277 (0.227–0.327) | 0.295 (0.243–0.346) | 0.870 (0.616–1.124) | 0.346 (0.199–0.493) | 0.005 | 0.351 (0.289–0.412) | 0.002 |

Data are shown as mean (95% confidence interval); Tmax data are shown as median (range). BF, breakfast.

The administration of NaPB with breakfast was tested in Patient 1 and resulted in the same plasma concentration and PK parameters for PB as those obtained through administration just after breakfast (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In vitro assessment of the therapeutic potency of NaPB in Patients 1 and 2

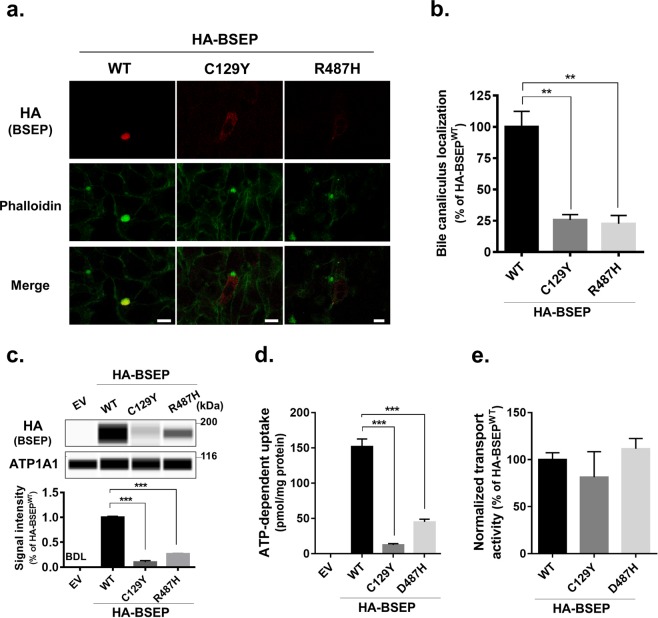

Patients 1 and 2 carried homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations, respectively, in ABCB11 (Table 1). To assess the therapeutic efficacy of NaPB in both patients, the impact of their ABCB11 mutations on BSEP was explored using HepG2 cells and HEK293T cells ectopically expressing HA-BSEPWT, HA-BSEPC129Y, and HA-BSEPR487H.

Immunocytochemical analysis using HepG2 cells confirmed that the expression of HA-BSEPWT was predominantly canalicular: it colocalized well with the phalloidin delineating the bile canaliculus. HA-BSEPC129Y and HA-BSEPR487H showed aberrant localization predominantly in endoplasmic reticulum-like structures (Fig. 4a). The number of cells with canalicular expression of either mutant was much lower than that for HA-BSEPWT (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that both mutations induce incomplete folding of BSEP molecules, which are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and then degraded through proteasomal degradation, as has been reported for other PFIC2-type mutations18,19. This leads to a decrease in BSEP expression at the hepatocanalicular membrane.

Figure 4.

Characterization of c.386 G > A (p.C129Y) and c.1460 G > A (p.R487H) mutations in ABCB11. HepG2 cells (a,b) and HEK293T cells (c–e) were transfected with pShuttle-HA-BSEPWT, HA-BSEPC129Y, HA-BSEPR487H, or a corresponding EV. (a,b) Expression and cellular localization of HA-BSEPC129Y and HA-BSEPR487H in HepG2 cells. The cells were immunostained and analyzed through confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. The cellular outline and bile canaliculi were visualized using alexa488-phalloidin. A representative image is shown in (a). Yellow in the merged images indicates colocalization. Scale bar: 10 μm. An analysis of the percentage of cells with each form of HA-BSEP at the bile canaliculus is shown in (b). A total of 30–40 cells immunostained using an anti-HA antibody were analyzed in each coverslip. (c–e) Expression and transport function of HA-BSEPC129Y and HA-BSEPR487H in HEK293T cells. Membrane vesicles prepared from the cells were analyzed through a capillary-based immunoassay (c) and subjected to a transport assay with 0.8 μM [3H]-TC. ATP-dependent uptake of [3H]-TC for 2 min was measured using each batch of membrane vesicles (d). Transport activity of [3H]-TC by each form of HA-BSEP (e) was calculated by normalizing the transport values in (d) by the HA-BSEP expression level determined in (c). In (a–e), a representative result of two independent experiments is shown. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of each experiment in triplicate. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; BDL, below detection limits because of low expression levels; EV, empty vector.

Consistent with the results obtained in HepG2 cells, expression of HA-BSEPC129Y and HA-BSEPR487H in membrane vesicles from HEK293T cells was 89.9% and 73.4% lower, respectively, than that of HA-BSEPWT (Fig. 4c). The transport assay showed that the ATP-dependent uptake of [3H]-taurocholate (TC) per mg of protein was 91.8% and 70.3% lower in HEK293T membrane vesicles expressing HA-BSEPC129Y and HA-BSEPR487H than in those expressing HA-BSEPWT (Fig. 4d). The differences in the expression of each form of HA-BSEP in these membrane vesicles (Fig. 4c) suggest that HA-BSEPC129Y and HA-BSEPR487H maintain their bile-acid transport activity at the same level as HA-BSEPWT (Fig. 4e). This in turn suggests that the increase in hepatic expression of BSEPC129Y and BSEPR487H as a result of NaPB therapy14,19,25 is therapeutically efficacious in Patients 1 and 2.

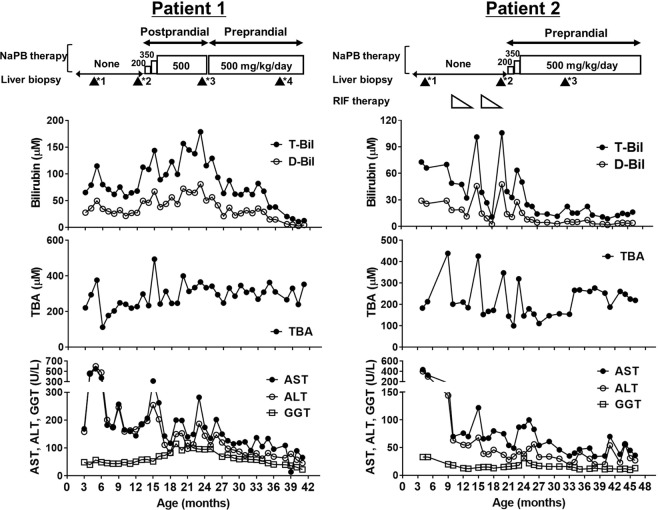

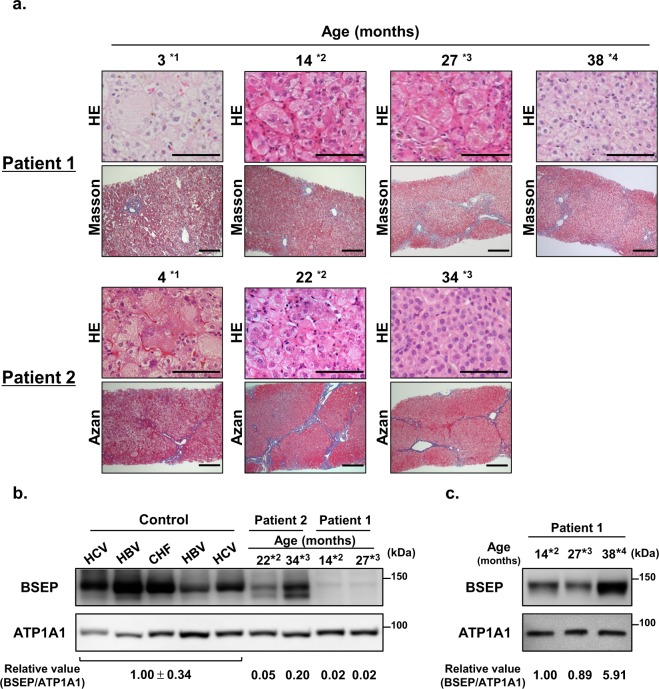

Biochemical and liver histological changes caused by NaPB therapy in Patients 1 and 2

Because in vitro assessment indicated the possible therapeutic efficacy of NaPB in Patients 1 and 2 (Fig. 4), these two patients started NaPB therapy at 14 and 22 months of age, respectively. For Patient 1, NaPB was administered orally during or just after meals in accordance with the approved guidelines for UCDs, and for Patient 2 it was administered before meals. The daily dose of NaPB started at 200 mg/kg/day divided into three doses; after 1 month, the dose was increased to 350 mg/kg/day, which was maintained for an additional month. Because neither a sufficient therapeutic effect nor any side effects were observed, the dose was increased to 500 mg/kg/day, the upper limit of the approved dose, and this was maintained for the next 12 and 25 months in Patients 1 and 2, respectively. During this time, the serum levels of total bilirubin (T-Bil) and direct bilirubin (D-Bil), aspartate aminotransaminase (AST), and alanine aminotransaminase (ALT) declined and reached the reference range (T-Bil < 20 μM; D-Bil < 4.3 μM; AST < 55 U/L; ALT < 40 U/L) in Patient 2, but not in Patient 1 (Fig. 5). Because of this, and based on the results of the PK study (Figs. 2, 3 and Table 2), Patient 1 was switched to preprandial oral administration of 500 mg/kg/day NaPB to increase PB systemic exposure and enhance PB therapeutic efficacy. The patient’s serum T-Bil and D-Bil levels gradually declined to within the reference range by 10 months after the change in regimen (Fig. 5). Serum AST and ALT levels also decreased and reached 66 and 46 U/L, respectively, close to the reference ranges (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Liver function tests in PFIC2 patients (Patients 1 and 2) before and during the course of NaPB therapy. Patients 1 and 2 underwent NaPB therapy as described in the Methods. Serum T-Bil, D-Bil, TBA, AST, ALT, and GGT levels were monitored. The dosage and regimen of NaPB administration during the course of therapy is shown at the top. Closed triangles represent times when a liver biopsy was performed. The number at the upper right of the triangles corresponds to that of age in Fig. 6. RIF, rifampicin; TBA, total bile acids.

In both patients, the improvement in liver function test results was accompanied by the disappearance of their jaundice and intractable itching, which eliminated their sleep disturbance. In contrast, the concentration of serum total bile acid (TBA) remained unchanged during the period of NaPB therapy, probably because of the co-administration of ursodeoxycholic acids. No severe side effects were observed during NaPB therapy.

Liver biopsies were performed at 3 months or 4 months of age for diagnosis and at 14, 27, and 38 months or 22 and 34 months of age to evaluate disease progression in Patients 1 and 2, respectively. In both patients, histological analysis at diagnosis showed cholestasis, giant cell transformation of hepatocytes, and fibrosis, liver histology compatible with PFIC2. Aggravation of these features with age was confirmed until onset of preprandial oral administration of NaPB. Preprandial oral administration of NaPB for 1 year markedly relieved cholestasis and hepatocyte swelling and suppressed the progression of fibrosis (Fig. 6a). Before commencement of preprandial oral administration of NaPB at 27 and 22 months of age in Patients 1 and 2, respectively, BSEP expression in the liver membrane fractions was <5% of that in age-matched control subjects. Preprandial oral NaPB therapy partly restored BSEP expression, although it remained at 12–20% of that in age-matched control subjects (Fig. 6b,c).

Figure 6.

Liver histology and hepatic BSEP expression in PFIC2 patients (Patients 1 and 2) before and during the course of NaPB therapy. (a) Liver histology. The liver sections were subjected to HE, Azan, or Masson’s trichrome staining. A typical image under each condition is shown. Original magnification; 400× (HE staining) and 100× (Azan and Masson’s trichrome staining). Bar, 100 μm. (b,c) Hepatic BSEP expression. The prepared membrane fractions (5 μg) were analyzed with those from age-matched control subjects through immunoblotting. The signal intensity of BSEP relative to that of ATP1A1 is presented below the panel. CHF, congenital hepatic fibrosis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that preprandial oral administration, rather than the prandial or postprandial administration approved for treating UCDs, was needed for NaPB therapy in normal-GGT PFIC, because food intake before the administration of NaPB markedly reduced systemic exposure to PB (Fig. 2) and eliminated its therapeutic potency (Figs. 5 and 6). In addition, no severe adverse events were observed during preprandial oral NaPB therapy.

After intestinal absorption, PB is taken up into hepatocytes and predominantly converted to PA through β-oxidation. PA forms PAG through conjugation with glutamine and is then excreted into the urine26. A PK study of a single oral administration of NaPB (150 mg/kg) in seven patients with normal-GGT PFIC demonstrated that postprandial administration markedly decreased the Cmax and AUC0–4 of PB by approximately 60% compared with preprandial administration (Figs. 2, 3 and Table 2). The longer time until Tmax observed with postprandial oral administration (Table 2) suggests that food intake affects absorption of PB by enterocytes as well as the ionization of PB by changes of the gastric pH and/or protein binding, leading to reduced intestinal absorption and systemic exposure of PB. The effect of food was also observed in the elimination of PB from the blood with its t1/2 value more than 2.5 times greater with postprandial administration than with preprandial administration (Figs. 2, 3 and Table 2). Considering the elimination process of PB, this could stem from the influence of food ingestion on the hepatic uptake of PB, rather than PB β-oxidation to form PA in hepatocytes, because both PA and PB increase BSEP expression in the liver27. In that case, hepatic exposure to PB after postprandial oral administration of NaPB could be less than that predicted by its systemic exposure. Alternatively, the delayed elimination phase of PB could be explained by flip-flop pharmacokinetics due to the short half-life of PB.

The results of the current study in the two PFIC2 patients indicated that preprandial oral administration of NaPB, but not prandial or postprandial oral administration, normalized or nearly normalized the results of liver function tests, relieved cholestasis, suppressed the progression of hepatic fibrosis, and markedly improved jaundice, intractable itching, and sleep disturbance (Fig. 5). It is likely that the lack of effective therapeutic outcomes after prandial or postprandial administration of NaPB resulted from reduced hepatic exposure to PB because of the inhibitory effect of food intake on the intestinal absorption of PB, resulting in hepatic concentration that were insufficient to increase the hepatocanalicular expression of BSEP (Fig. 6b,c). This is supported by our previous in vitro study showing that the minimum concentration of PB required to increase ectopic BSEP expression in MDCKII cells was 1000 μM (164.2 μg/mL)14, which is above the plasma concentration of PB achieved through NaPB administration just after breakfast (Fig. 2).

In our previous study examining the short-term efficacy and safety of NaPB, biological and histological improvements were obtained in another PFIC2 patient (Patient 3) at a dosage of 500 mg/kg/day19. This patient’s mother divided the daily dosage of NaPB into four and gave the patient three doses preprandially and between meals, because the patient showed poor compliance with medication given orally in the prandial and postprandial period because of a sense of fullness. In contrast, we tested the short-term effect of NaPB in another two PFIC1 patients including Patient 5, using a regimen of postprandial oral administration, as approved for UCDs20. In these patients, NaPB therapy relieved intractable itching and resolved sleep disturbance, but did not improve liver function tests and liver histology. There are four other studies that have examined the efficacy and safety of NaPB in patients with normal-GGT PFIC16,17,23,28. Gonzales et al. reported that NaPB therapy improved the clinical and biological parameters of cholestasis in three of four PFIC2 patients and helped them to manage their medical condition16,17. However, based on observations in two PFIC2 patients, Malatack et al. suggested a combined drug regimen including NaPB for PFIC2, because monotherapy with NaPB appeared to be insufficient to improve and maintain the clinical condition of the patients23. There is no description in any of these articles concerning how or when NaPB was administered to these patients. Therefore, the inconsistencies between the results of these studies may be explained by the food interaction effects found in the current study. Additional studies with more patients are required to fully understand the therapeutic potency of NaPB in normal-GGT PFIC.

After confirming the optimal protocol to maximize the efficacy and safety of NaPB, it may be desirable to evaluate a combination therapy of NaPB with Maralixibat as previously proposed23. Maralixibat blocks the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids by inhibiting the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter that is expressed on intestinal epithelial cells and mediates the absorption of bile acids from the intestinal lumen. Therefore, therapy combining Maralixibat with NaPB, which enhances the biliary excretion of bile acids by increasing the hepatocanalicular expression of BSEP, could generate a synergistic therapeutic effect by lowering hepatic bile-acid levels in patients with normal-GGT PFIC, with the exception of those with a loss-of-function mutation in ABCB11. Such a combination therapy may become the preferred choice for the treatment of normal-GGT PFIC, replacing the need for partial external biliary diversion and liver transplantation.

A questionnaire survey of 52 patients of UCDs and their caregivers and physicians showed that patients have difficulty taking NaPB because of its odor, taste, and large dosage, which results in poor medication compliance and hence worse therapeutic outcomes29. The physicians indicated that the patients with UCDs were prescribed less than the target dosage of NaPB because of concerns about tolerance, administration, and cost. The findings of the current study suggest that in UCDs, preprandial instead of the approved prandial or postprandial administration may make it possible to reduce the clinically effective dosage of NaPB. It is not possible to compare the PK parameters in the current study with those obtained in healthy adults and individuals with other diseases because the relationship between dosing and meal timing was not described in previous studies26,30. However, considering that the effects of meal timing on the PK of NaPB were similar in all the participants in the present study (Fig. 3), who varied in age and disease severity (Table 1), it is conceivable that the findings of this study are applicable to UCDs as well as to normal-GGT PFIC.

In conclusion, the present study showed that food intake before the administration of NaPB markedly reduced PB systemic exposure and could eliminate its therapeutic efficacy in patients with normal-GGT PFIC. Therefore, preprandial oral administration of NaPB could be needed to maximize its potency in these patients and decrease the clinically effective dose in patients with UCDs. To determine an optimal NaPB regimen for each disease, preprandial treatment with NaPB should be assessed in future research with careful monitoring of adverse events, such as PA-induced hepatotoxicity28.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Tokyo, Juntendo University, Saiseikai Yokohama City Tobu Hospital, Yamaguchi University Hospital, Osaka University Hospital, and Nagasaki University Hospital, and was performed in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of each patient prior to enrollment in the study.

Patients

Seven patients with normal-GGT PFIC participated in the PK study (Table 1). The clinical diagnosis of normal-GGT PFIC was based on the presence of unremitting hepatocellular cholestasis with intractable pruritus, poor growth, and jaundice with normal serum GGT levels, in the first year of life, and the exclusion of type A, B, C, and E hepatitis, biliary atresia, Alagille syndrome, neonatal intrahepatic cholestasis caused by citrin deficiency, Dubin–Johnson syndrome, and Wilson disease. The patients did not suffer from any disease other than cholestasis, as determined through a detailed medical history, full physical examination, vital signs, urinalysis, and blood tests with values within the reference range or deemed to be normal by the clinical investigator.

Sanger sequencing of ABCB11 and ATP8B1 and liver biopsies were performed to determine the subtype of PFIC19,20. Patients who carried disease-causing mutations in both alleles of ABCB11 or ATP8B1 were diagnosed with PFIC2 (Patients 1–3) or PFIC1 (Patient 4), respectively. Patients 5 and 6, in whom only one mutant allele of ATP8B1 was detected, were diagnosed with PFIC1 because phenotypic analysis using peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages indicated an ATP8B1 deficiency2. Patient 7 had no mutations detectable through Sanger sequencing of either gene, and therefore was diagnosed with PFIC-like disease. The patients had not undergone any surgical procedures, except Patient 6 who underwent partial internal biliary diversion.

PK study design

To examine the effect of meal timing on the PK of NaPB in patients with normal-GGT PFIC, a multicenter, open-label, single-dose PK study was conducted in Juntendo University Hospital, Saiseikai Yokohama City Tobu Hospital, and Yamaguchi University Hospital. Eligible participants were children with a confirmed diagnosis of normal-GGT PFIC who had not undergone liver transplantation. Seven relevant patients as described above were identified in a Japanese nationwide survey conducted in 2015. They were enrolled by the physicians in the PK study between 29/11/2016 and 1/3/2018. This study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry at http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm (registration ID: UMIN000025037) on the 29/11/2016.

The patients were admitted a day before the PK study and were orally administered with 150 mg/kg NaPB (Buphenyl; OrphanPacific, Tokyo, Japan) 30 min before breakfast, just before (<10 min) breakfast, and just after (<10 min) breakfast following overnight fasting. Each regimen was separated by a washout period of more than 24 h, based on a previous study reporting that the majority of PB and its metabolites disappear from systemic circulation and are excreted into the urine within 24 h after oral administration of NaPB24,26. Standard hospital food suitable for the children was served as breakfast, and at 3 and 9 h post-treatment. All patients were prohibited from ingesting any food for at least 3 h after NaPB administration. Treatment with other drugs was maintained during patient participation in the PK study.

Blood samples were collected through a catheter placed in a forearm vein into an EDTA-2Na+-pretreated tube prior to, soon after, and 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 300 min after drug administration. Blood samples were placed at 4 °C immediately after collection and centrifuged for 15 min at 3,000 rpm to prepare the plasma. The prepared specimens were analyzed to measure PB concentration as described in the supplementary information.

PK analysis

The Cmax and Tmax of PB were determined directly from the observed data. The AUC0–4 of PB was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The kel of PB was estimated using a least-squares regression analysis from the terminal post-distribution phase of the concentration–time curve. The t1/2 of PB was calculated as 0.693 divided by the kel.

Treatment of the PFIC2 patients with NaPB

The effect of food on the therapeutic efficacy of NaPB was investigated in two patients (Patients 1 and 2) because the other patients participated in another clinical trial after the PK study. Patients 1 and 2 developed hepatocellular cholestasis and jaundice with normal GGT at the age of 1 and 2 months, respectively, and were diagnosed with PFIC2 at 5 and 4 months, respectively, based on genetic analysis and the lack of a detectable signal for BSEP at the canalicular membrane on performing a liver histological analysis. Patient 1 carried a homozygous mutation, c.386 G > A (p.C129Y) in ABCB11, the most frequent mutation in Japanese PFIC2 patients25,31. Patient 2 carried a compound heterozygous mutation, c.386 G > A (p.C129Y) and c.1460 G > A (p.R487H) in ABCB11 (see Table 1). Neither patient showed adequate improvement in liver biochemical tests and clinical symptoms with conventional medical treatment such as ursodeoxycholic acid. Patient 2 received two cycles of rifampicin treatment at 9–12 months of age and at 15–18 months of age, with gradually decreasing dosages (10, 7.5, 5, and 1.4 mg/kg/day). Although the medication gradually decreased patient jaundice and serum T-Bil and D-Bil levels and partially alleviated pruritus, the symptoms recurred after rifampicin withdrawal on both occasions (Fig. 5). Liver histological analysis at 22 months of age showed disease progression, compared with that at 4 months of age (Fig. 6a). Based on these observations and the fact that rifampicin is not suitable for long-term treatment because of its potential hepatotoxic effects32–34, the patients started NaPB therapy at 14 and 22 months of age, respectively. Before the intervention, the potential therapeutic potency of NaPB was confirmed in both patients through an in vitro assessment (Fig. 4) and our previous study25. In both patients, treatment with ursodeoxycholic acids and fat-soluble vitamins was maintained during the course of NaPB therapy.

Liver function tests were performed monthly using standard methods. A liver needle biopsy was performed before and during the course of NaPB treatment. Immediately after the sample collection, a part of the liver sample was fixed in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for histological analysis, and the remaining portion was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C for the preparation of membrane fractions. A detailed description for the histological analysis and preparation of membrane fractions is presented in the supplementary information.

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (v. 6; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The data of Cmax, AUC0–4, kel, and t1/2 values were analyzed through repeated one-way analysis of variance with a post-hoc Dunnett’s test. The Tmax values were compared using Friedman test with a post-hoc Dunn’s tests. The nonclinical studies were analyzed through one-way analysis of variance with a post-hoc Dunnett’s test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families who participated in this study. This work was supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP19ek0109298 to H.H. The funding source does not participate in the study design and execution.

Author contributions

S.N. designed, performed the pharmacokinetic study, and wrote the manuscript. S.O. measured plasma concentration of PB, preformed in vitro experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.S. preformed in vitro experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. K.M., S.H. and M.S. carried out clinical assessment of the NaPB therapy, performed the pharmacokinetic study, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. H.K., T.K., Y.A., S.W., A.I., K.B., H.N., T.S. and H.K. helped to conceptualize the study, supervised data collection, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. H.K., A.N., K.T., M.K. and Y.Z. designed, performed the liver histological analysis, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. H.H. conceived, design, supervised the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

Dr. Hiroki Kondou has received NaPB for free from OrphanPacific, Inc. for an ongoing clinical trial (UMIN000024753). The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Satoshi Nakano and Shuhei Osaka.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-53628-x.

References

- 1.Davit-Spraul A, Gonzales E, Baussan C, Jacquemin E. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi, H. et al. Assessment of ATP8B1 Deficiency in Pediatric Patients With Cholestasis Using Peripheral Blood Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. EBioMedicine, 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.10.007 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bull LN, et al. A gene encoding a P-type ATPase mutated in two forms of hereditary cholestasis. Nat Genet. 1998;18:219–224. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez-Ospina N, et al. Mutations in the nuclear bile acid receptor FXR cause progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10713. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sambrotta M, et al. Mutations in TJP2 cause progressive cholestatic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:326–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strautnieks SS, et al. A gene encoding a liver-specific ABC transporter is mutated in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Nat Genet. 1998;20:233–238. doi: 10.1038/3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morotti RA, Suchy FJ, Magid MS. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) type 1, 2, and 3: a review of the liver pathology findings. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:3–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suchy, F. J., Sundaram, S. & Shneider, B. 13. Familial Hepatocellular Cholestasis. Liver Disease inChildren, 4th Edition, 199–215, 10.1017/Cbo9780511547409.001 (2014).

- 9.Hori T, et al. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: a single-center experience of living-donor liver transplantation during two decades in Japan. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:776–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jara P, et al. Recurrence of bile salt export pump deficiency after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1359–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keitel V, et al. De novo bile salt transporter antibodies as a possible cause of recurrent graft failure after liver transplantation: a novel mechanism of cholestasis. Hepatology. 2009;50:510–517. doi: 10.1002/hep.23083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maggiore G, et al. Relapsing features of bile salt export pump deficiency after liver transplantation in two patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2. J Hepatol. 2010;53:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi H, et al. AP2 adaptor complex mediates bile salt export pump internalization and modulates its hepatocanalicular expression and transport function. Hepatology. 2012;55:1889–1900. doi: 10.1002/hep.25591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi H, Sugiyama Y. 4-phenylbutyrate enhances the cell surface expression and the transport capacity of wild-type and mutated bile salt export pumps. Hepatology. 2007;45:1506–1516. doi: 10.1002/hep.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam P, et al. Levels of plasma membrane expression in progressive and benign mutations of the bile salt export pump (Bsep/Abcb11) correlate with severity of cholestatic diseases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1709–1716. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00327.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzales E, et al. Successful mutation-specific chaperone therapy with 4-phenylbutyrate in a child with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2. J Hepatol. 2012;57:695–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzales E, et al. Targeted pharmacotherapy in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2: Evidence for improvement of cholestasis with 4-phenylbutyrate. Hepatology. 2015;62:558–566. doi: 10.1002/hep.27767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi H, Takada T, Suzuki H, Akita H, Sugiyama Y. Two common PFIC2 mutations are associated with the impaired membrane trafficking of BSEP/ABCB11. Hepatology. 2005;41:916–924. doi: 10.1002/hep.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naoi S, et al. Improved liver function and relieved pruritus after 4-phenylbutyrate therapy in a patient with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1219–1227 e1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa Y, et al. Intractable itch relieved by 4-phenylbutyrate therapy in patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 1. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:89. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen F, et al. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, type 1, is associated with decreased farnesoid X receptor activity. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:756–764. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulusma CC, de Waart DR, Kunne C, Mok KS, Elferink RP. Activity of the bile salt export pump (ABCB11) is critically dependent on canalicular membrane cholesterol content. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9947–9954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808667200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malatack, J. J. & Doyle, D. A Drug Regimen for Progressive Familial Cholestasis Type 2. Pediatrics, 141, 10.1542/peds.2016-3877 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.(FDA), U. F. a. D. A. Labels for NDA 020572: BUPHENYL® (sodium phenylbutyrate) (2009).

- 25.Imagawa K, et al. Clinical phenotype and molecular analysis of a homozygous ABCB11 mutation responsible for progressive infantile cholestasis. J Hum Genet. 2018;63:569–577. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuire BM, et al. Pharmacology and safety of glycerol phenylbutyrate in healthy adults and adults with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2077–2085. doi: 10.1002/hep.23589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagasaka H, et al. Evaluation of risk for atherosclerosis in Alagille syndrome and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: two congenital cholestatic diseases with different lipoprotein metabolisms. J Pediatr. 2005;146:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shneider BL, Morris A, Vockley J. Possible Phenylacetate Hepatotoxicity During 4-Phenylbutyrate Therapy of Byler Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:424–428. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shchelochkov OA, et al. Barriers to drug adherence in the treatment of urea cycle disorders: Assessment of patient, caregiver and provider perspectives. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2016;8:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert J, et al. A phase I dose escalation and bioavailability study of oral sodium phenylbutyrate in patients with refractory solid tumor malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2292–2300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Togawa T, et al. Molecular Genetic Dissection and Neonatal/Infantile Intrahepatic Cholestasis Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J Pediatr. 2016;171:171–177 e174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prince MI, Burt AD, Jones DE. Hepatitis and liver dysfunction with rifampicin therapy for pruritus in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2002;50:436–439. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheuer PJ, Summerfield JA, Lal S, Sherlock S. Rifampicin hepatitis. A clinical and histological study. Lancet. 1974;1:421–425. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)92381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stapelbroek JM, van Erpecum KJ, Klomp LW, Houwen RH. Liver disease associated with canalicular transport defects: current and future therapies. J Hepatol. 2010;52:258–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.