Abstract

Secreted factors derived from Lactobacillus are able to dampen pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. Still, the nature of these components and the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Here, we aimed to identify the components and the mechanism involved in the Lactobacillus-mediated modulation of immune cell activation. PBMC were stimulated in the presence of the cell free supernatants (CFS) of cultured Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938, followed by evaluation of cytokine responses. We show that lactobacilli-CFS effectively dampen induced IFN-γ and IL-17A responses from T- and NK cells in a monocyte dependent manner by a soluble factor. A proteomic array analysis highlighted Lactobacillus-induced IL-1 receptor antagonist (ra) as a potential candidate responsible for the IFN-γ dampening activity. Indeed, addition of recombinant IL-1ra to stimulated PBMC resulted in reduced IFN-γ production. Further characterization of the lactobacilli-CFS revealed the presence of extracellular membrane vesicles with a similar immune regulatory activity to that observed with the lactobacilli-CFS. In conclusion, we have shown that lactobacilli produce extracellular MVs, which are able to dampen pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in a monocyte-dependent manner.

Subject terms: Cytokines, Bacteria

Introduction

The influence of gut commensal bacteria on immune development and function is well established1,2. Still, the relationship between the host and gut bacteria is complex and although microbial diversity is an important factor in maintaining immune homeostasis3–5, specific bacterial organisms such as lactobacilli have been found to have key roles in shaping immune cell composition and function locally as well as systemically6–9.

Probiotic bacteria are defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”10. Lactobacilli represent a large and diverse group of bacteria, including many species and strains with probiotic effects. Lactobacilli have been shown to promote immune homeostasis through several mechanisms including pathogen inhibition11–13, intestinal barrier fortification14,15 and modulation of immune cell composition and function16–23. Much research has been invested in identifying the Lactobacillus (L.)-derived components responsible for the aforementioned effects24,25. Indeed, isolated peptidoglycan (PGN) from L. salivarius Ls33 protects mice from colitis by activation of the intracellular NOD2 receptor pathway26. Cell wall associated polysaccharides contribute to the ability of lactobacilli to counteract lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation of murine macrophages27. Lactobacillus and its isolated RNA directly suppress CD4+ T cell proliferation in a MyD88-dependent mechanism28, while specific DNA motifs suppress IgE-responses through activation of regulatory dendritic cells (DC)29,30. The secreted protein p40 promotes intestinal homeostasis by engagement of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expressed on colonic epithelium as well as promoting IgA production via a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL)31,32. Interestingly, the highly abundant surface layer protein A (SlpA) from Lactobacillus, was found to supress NF-κB activation in intestinal cells while at the same time promoting inflammatory tumour necrosis factor (TNF) expression in macrophages33, highlighting the complexity of the cross-talk between probiotic bacteria and the host. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as butyrate and propionate (but not acetate) were found to increase de-novo generation of peripheral Treg cells in an in vivo mouse model34. Moreover, lactic acid has a suppressive effect on IFN-γ production in human T- and NK cells17, and its production is a major contributor to the protective effects of lactobacilli against bacterial vaginosis35.

T- and NK cell activity is strongly influenced by antigen presenting cells (APC) such as DC, macrophages and monocytes. APC control lymphocyte activation through expression of co-receptors, release of chemokines and cytokines to ensure optimal pathogen clearance and to avoid tissue damage. APC-derived cytokines such as TNF, IL-1α/β, IL-6 and IL-12 enhance lymphocyte effector functions while TGF-β, IL-1 receptor antagonist (ra) and IL-10 inhibit inflammatory responses36. Lactobacilli are known to induce the production of innate-derived cytokines via both cell wall-derived components and secreted metabolites. Interestingly, viable lactobacilli induced IL-1β and IL-12 gene transcription in macrophages while the corresponding cell free supernatants (CFS) did not37. Lactobacilli-derived cell-surface components were shown to be the main inducers of inflammatory TNF production from PBMC cultures38, suggesting different immune stimulatory capacity of whole lactobacillus cells compared with the CFS. Soluble components derived from the gut microbiota effectively translocate from the gut lumen to peripheral tissues where they remain biologically active39, thus, studies regarding the effects of Lactobacillus-CFS on peripheral lymphocytes are indeed relevant. However, the vast majority of mechanistic studies are restricted to the intestinal epithelium and innate immune cells whereas the influence of, and mechanisms behind, lactobacilli-mediated modulation of peripheral lymphocyte responses are not fully understood.

Here, we aimed to investigate the mechanism behind the ability of Lactobacillus-CFS to dampen inflammatory cytokine production in peripheral lymphocytes and to identify the responsible Lactobacillus-derived components. We show that Lactobacillus-CFS promotes monocyte activation and in parallel dampens inflammatory cytokine release from lymphocytes. Size fractionation of the Lactobacillus-CFS revealed multiple factors with the capacity to dampen IFN-γ secretion in a monocyte-dependent manner. Furthermore, we successfully identified extracellular membrane vesicles (MVs) derived from the Lactobacillus-CFS, which recapitulated both the immune stimulatory and the IFN-γ dampening activity observed with the CFS alone, suggesting that gut bacteria-derived extracellular MVs are important modulators of human immunity with new implications for probiotic design.

Material and Methods

Ethical statement and isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Healthy, anonymous, adult volunteers (age 18–65) were included in this study, which was approved by the Regional Ethic’s Committee at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden {Dnr 04-106/1 and 2014/2052-32} and the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All study subjects gave their informed written consent. Venous blood was diluted with RPMI-1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (HyClone Laboratories, Inc.). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were then isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB) gradient separation. The PBMC were washed in RPMI-1640, resuspended in freezing medium containing RPMI-1640 40%, Fetal calf serum (FCS) 50% and DMSO 10%, gradually frozen in a freezing container (Mr Frosty, Nalgene Cryo 1 °C; Nalge Co.) and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Bacterial strains and generation of cell free supernatants

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103), Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 1793840 (a kind gift from BioGaia AB, Stockholm, Sweden) and Staphylococcus aureus 161:2 (a kind gift from Åsa Rosengren, The National Food Agency, Uppsala, Sweden)41 were used in this study. The lactobacilli were first grown for 24 h on Rogosa agar plates (Oxoid) from which a single colony was inoculated into De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) medium and grown as still culture overnight. The bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with glucose 18 g/l and FCS 20% at OD600 of 0.2 and grown as still cultures for 48 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Finally, the bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation and the CFS was pH-neutralized using 5 M NaOH, 0.2 μm filtered and stored as aliquots at −20 °C. S. aureus was first grown for 24 h on brain, heart infused (BHI) agar plates from which a single colony was inoculated into BHI broth and grown as still cultures for 72 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The CFS was collected by centrifugation and 0.2 μm filtered aliquots were stored at −20 °C.

Size fractionation of the Lactobacillus-CFS

Size fractionation of the Lactobacillus-CFS was done using Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter units (Merck Millipore). In brief, CFS was centrifuged for 40 min at 3400 × g at 4 °C in sequential order starting with the highest molecular weight cut-off (MwCO) of 100 kDa. After centrifugation, the concentrated top-fraction was re-diluted to its starting volume with RPMI-1640 cell culture medium, aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until used in assays. High performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was performed using the Agilent 1260 infinity system. A Superdex 200 10/300 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare) was equilibrated sequentially with sterile filtered water, 30% (v/v) ethanol, sterile water and finally with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH7.4 (0.137 M NaCl, 0.0027 M KCl, 0.01 M Na2HPO4 and 0.0018 M KH2PO4). 500 µL of Lactobacillus-CFS was injected into the column of the system operating at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min and dispenser was set at 1 min slide time. Fractions were collected into a sterile 96-well plate. Consecutive fractions of 3 were subsequently pooled, aliquoted and stored at −20 °C.

In Vitro stimulation of PBMC

PBMC were thawed, washed and stained with Trypan blue followed by live cell counting using a 40x light microscope. Cells were resuspended in cell culture medium containing RPMI-1640 supplemented with HEPES (20 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), L-glutamine (2 mM) (all from HyClone Laboratories, Inc.) and FCS 10% (Gibco by Life Technologies) at a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were seeded in flat-bottomed cell culture plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 atmosphere. S. aureus-CFS was used as stimuli at 2.5% (v/v), lactobacilli-CFS was used at 10% (v/v) and Dynabeads human T-activator CD3/CD28 (Life Technologies) was used at 2:1 (cell:bead) ratio.

Cell enrichment and depletion

Enriched T cells were generated from PBMC through negative selection using EasySepTM Human T cell enrichment kit. To generate monocyte-depleted PBMC or B cell-depleted PBMC we used positive selection with EasySepTM Human CD14 Positive Selection Kit II or EasySepTM Human CD19 Positive Selection Kit II, respectively (all from STEMCELL Technologies Inc.). In brief, frozen PBMC were thawed, washed and resuspended in PBS containing FCS 2% and EDTA 1 mM at 50 × 106 cells/ml. PBMC were incubated with an antibody cocktail, followed by magnetic particles and target cells were depleted or recovered using an EasySep magnet according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cell purity after depletion or enrichment was confirmed by flow cytometric analyses.

Generation of monocyte-conditioned medium

Isolated monocytes were seeded in a 48-well culture plate at 1 × 106 cells/ml and treated for 6 h with 10% LGG-CFS. Next, the monocytes were washed twice with cell culture medium and incubated in fresh cell culture medium for 14 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Finally, the monocyte-conditioned medium was collected by centrifugation and stored at 4 °C until later use.

Proteome profiler array

The monocyte-conditioned medium was analysed for 105 secreted proteins using the Human XL Cytokine Array Kit (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the stamped identification number on each membrane was cut off and replaced with an individual mark using a pencil. Each membrane was then blocked, washed and incubated overnight at 4 °C on a rocking platform with 1.5 ml of monocyte-conditioned medium diluted 1:3 using the supplied array buffer. Membranes were washed and incubated with the detection antibody cocktail for 1 h at room temperature (RT) on a rocking platform followed by addition of IRDye 800 CW Streptavidin (LI-COR Biosciences) for 30 min. Finally, the membranes were scanned and images acquired using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Lipid removal assay

The commercial kit Cleanascite lipid adsorption and clarification reagent (Biotech Support Group) was used to remove lipids and extracellular membrane vesicles from the Lactobacillus-CFS according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, one part of Cleanascite reagent was added to four parts of Lactobacillus-CFS and incubated at RT for 40 min under periodical mixing. Finally, the Cleanascite reagent was separated from the CFS by centrifugation at 15000 × g for 1 min after which the supernatant was collected and subjected to fractionation using an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter unit (Merck Millipore) with a MwCO of 100 kDa.

Proteinase K digestion and heat treatment

The Lactobacillus-CFS was subjected to protein digestion using Proteinase K immobilized to agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) using a modified protocol of that described elsewhere42. Proteinase K-agarose was added to Lactobacillus-CFS to a working concentration of 1 mg/ml and incubated with rotation at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, the Proteinase K-agarose was removed by centrifugation at 15000 × g for 1 min. Finally, the proteinase K digested CFS was fractionated using an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter unit (Merck Millipore) with a MwCO of 100 kDa. Fractionated control-CFS was also subjected to heat treatment at 96 °C for 15 min prior to cell stimulations.

Isolation of extracellular membrane vesicles (MVs)

Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 bacterial cells were grown in MRS broth (Oxoid) for 24 h at 37 °C. The bacterial cells were removed from the culture broth by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and followed by another centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Then the supernatants were filtrated using 0.45 μm pore filter (Millipore). Cell free supernatants were concentrated using Amicon Ultra filter unit with a MwCO of 100 kDa (which remove proteins and other molecules under 100 kDa). The supernatants were loaded on top of 12% sucrose cushion with 50 mM Tris buffer pH 7,2, with the volume ratio 5:1, and centrifuged by Beckman coulter Optima L – 80XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman coulter) at 118,000 × g at 4 °C for 3 h. The supernatants were discarded and the pellet was resuspended in PBS buffer and ultra-centrifuged for the second time (118,000 × g at 4 °C for 3 h). The pellets were then dissolved in PBS, aliquoted and stored at −70 °C.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

The physicochemical characterization of MVs was also investigated by using the Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). Extracellular vesicles were diluted with PBS, and directly tracked using the NanoSight NS300 system (NanoSightTM technology). The analysis was carried out according to the following instrumental set up: (i) a laser beam of 488 nm (blue); (ii) and a high-sensitivity sCMOS camera. Videos were collected and analysed using the NTA software (version 3.2), capturing a video file of the particles moving under Brownian motion. The software tracks many particles individually and using the Stokes–Einstein equation calculates their hydrodynamic diameters. Multiple videos of 90 s duration were recorded generating replicate histograms that were averaged for each sample.

ELISA

Secreted levels of the cytokines IL-1ra (R&D Systems-BioTechne), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A and IFN-γ (MabTech AB) were measured in cell culture supernatants using sandwich ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm using a micro-plate reader (Molecular Devices Corp.) and results analysed using SoftMax Pro 5.2 rev C (Molecular Devices Corp.).

Flow cytometry

Stimulated cells were treated with GolgiPlug/Brefeldin A for the last 4 h of incubation to block secretion of cytokines. Cells were collected and transferred to a V-shaped 96-well staining plate, stained with the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit-Aqua (Life Technologies) and Fc-receptors were blocked with 10% human serum. Next, extracellular surface markers were stained with anti-CD3-PECy7 (clone: SK7), CD4-PE (clone: RPA-T4) (both from BioLegend), CD8-APCH7 (clone: SK1), CD56-APC (clone: B159) (both from BD Biosciences) and pan-γδ TCR-FITC (clone: IMMU510) (Beckman Coulter). Cells were fixed/permeabilized with the Transcription Factor buffer set (BD Biosciences) followed by intracellular staining with IFN-γ-PerCPCy5.5 (clone: B27) (BD Biosciences). Stained cells were acquired using a FACSVerse instrument with the FACS Suite software (BD Biosciences). Lymphocytes were gated based on forward/side scatter properties. Viable lymphocytes were further gated on cell surface markers; NK cells were classified as CD3−CD56+, T helper cells as CD3+CD4+, T cytotoxic cells as CD3+CD8+ and γδ T cells as CD3+γδ TCR+. Data was analysed using FlowJo Software (TreeStar).

Statistics

All statistical tests were done using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). All data was considered non-parametric. For Figs. 1–5, the Wilcoxon test was employed. The Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons was employed in Fig. 4a. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05 and the following significance levels were used *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

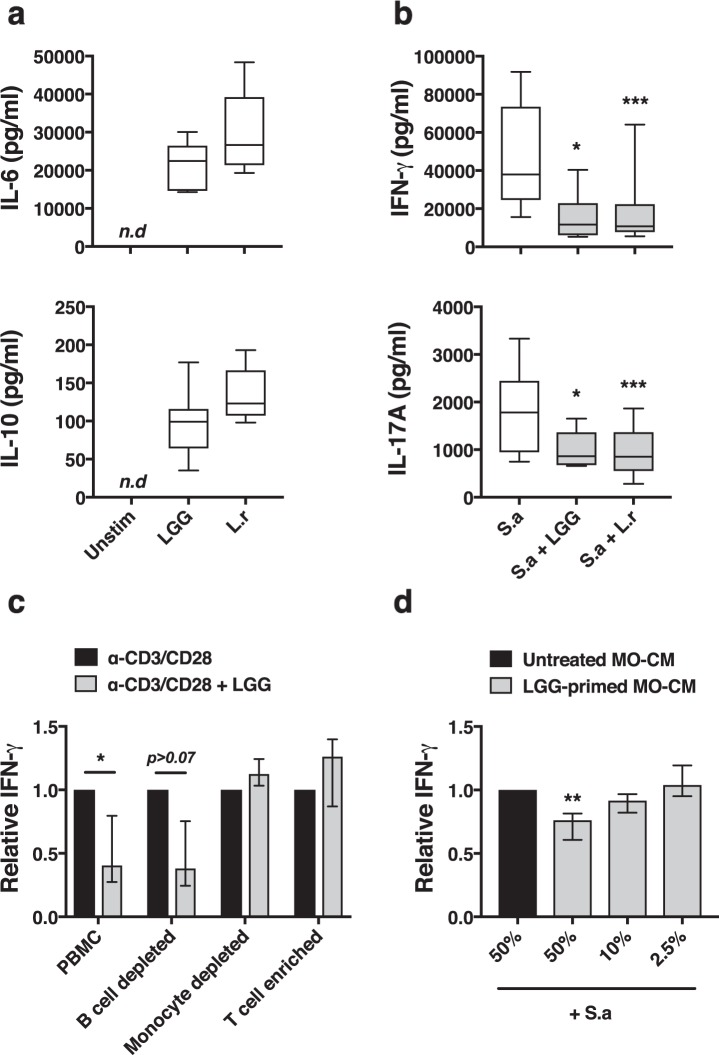

Figure 1.

Lactobacilli-CFS dampens IFN-γ in a monocyte-dependent manner. PBMC were stimulated as indicated and culture supernatants were collected after 48 h and secreted cytokines evaluated with ELISA. (a) Secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 following stimulation with LGG- or L. reuteri (L.r)-CFS (n = 5–6). (b) Secretion of IL-17A and IFN-γ following stimulation with S. aureus (S.a)-CFS alone and in combination with Lactobacillus-CFS (n = 6–14). (c) Whole PBMC, B cell depleted, monocyte depleted or enriched T cells were stimulated with T cell specific activator beads towards CD3/CD28 alone and in combination with LGG-CFS. Secreted levels of IFN-γ was determined and normalized to stimulated cells in the absence of LGG-CFS, (n = 4–8). (d) Monocyte-conditioned medium (MO-CM) from isolated monocytes primed with LGG-CFS for 6 h, extensively washed and incubated in fresh cell culture medium for 14 h, was mixed 1:1 (50%), 1:10 (10%) or 1:40 (2.5%) with S.a-CFS-stimulated autologous PBMC cultures. Secreted levels of IFN-γ was quantified and normalized to stimulated cells mixed 1:1 with unprimed monocyte conditioned medium, (n = 6–8). Boxes cover data between the 25th and the 75th percentile with medians as the central line and whiskers showing min-to-max. Bar plots show median with interquartile range.

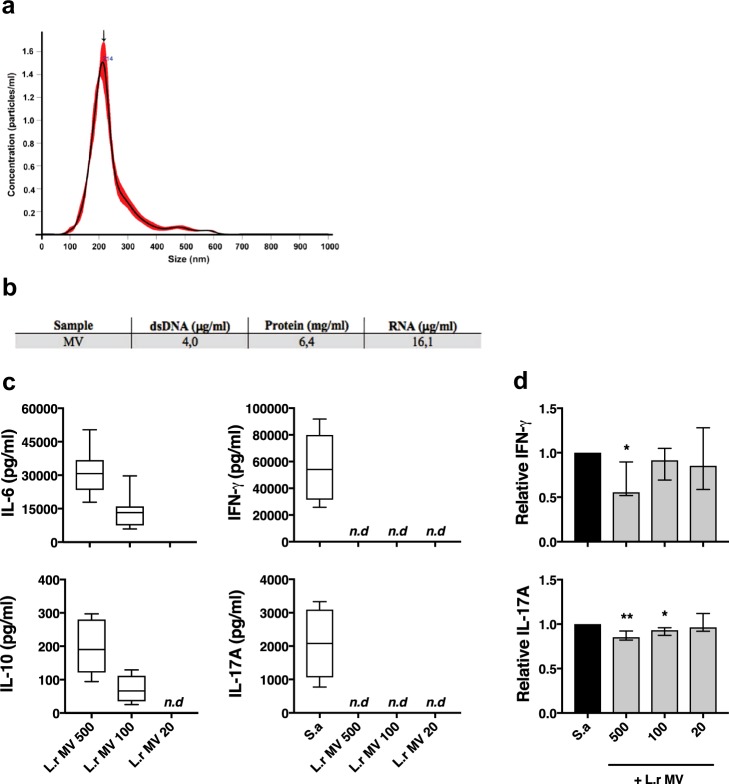

Figure 5.

Lactobacilli-derived extracellular membrane vesicles are immune stimulatory and dampen IFN-γ and IL-17A responses. Characterization and evaluation of the immunomodulatory effects of purified L. reuteri-derived extracellular membrane vesicles (MVs) in PBMC cultures. (a) The nanoparticle tracking distribution of isolated MVs from L. reuteri is representative of three independent replicates. The size distribution represents the wide distribution of vesicles with the arrow marking the mean peaks of particles at 214 nm and a concentration of 1,6 × 1012 particles/ml. (b) Quantification of dsDNA, protein and RNA content of the MVs isolates. (c) PBMC were cultured for 48 h in the presence of L. reuteri (L.r)-MVs at 500:1, 100:1, and 20:1 (MV:cell) ratio followed by quantification of secreted levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A and IFN-γ (n = 8). (d) PBCM were stimulated with S. aureus (S.a)-CFS (2.5%) in the presence of L.r-MVs at 500:1, 100:1 and 20:1 (MV:cell) ratio followed by quantification of secreted levels of IFN-γ and IL-17A. Shown are relative values normalized to S. aureus-CFS alone, (n = 8). Boxes cover data between the 25th and the 75th percentile with medians as the central line and whiskers showing min-to-max. Bar plots show median with interquartile range.

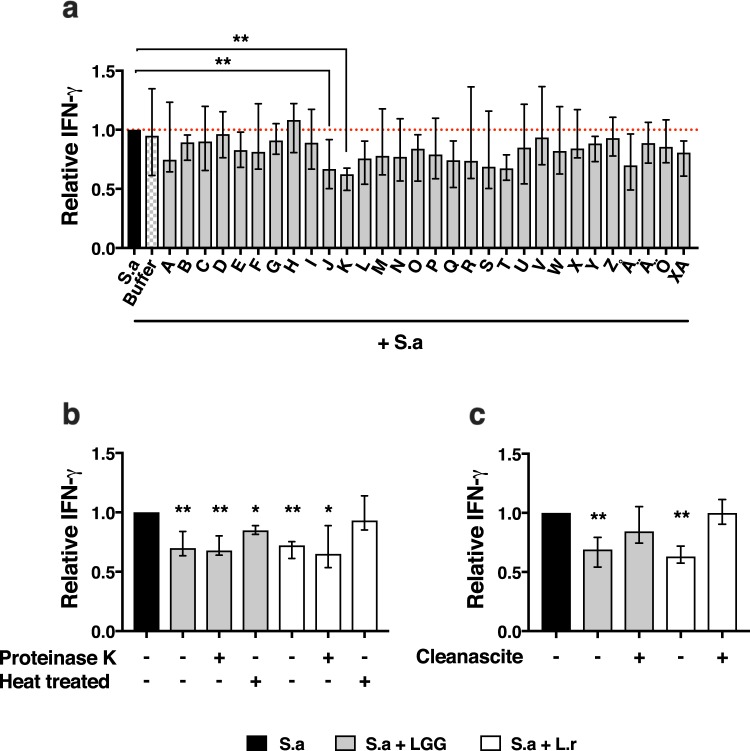

Figure 4.

The lactobacilli-CFS high Mw fraction contains an isolated heat sensitive lipid-based factor. Molecular characterization of the IFN-γ dampening factor of the Lactobacillus-CFS high Mw fraction. The Lactobacillus-CFS high Mw fraction was subjected to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), proteinase K treatment, heat inactivation or delipidation through lipid adsorption before being added to S. aureus (S.a)-CFS stimulated PBMC. (a) The LGG-CFS was spin-column fractionated with a pore-size of 100 kDa, after which the top fraction was collected and subjected to further size fractionation using HPLC. The HPLC generated fractions were added to S.a-CFS stimulated PBMC for 48 h followed by quantification of secreted levels of IFN-γ normalized to S.a-CFS alone, (n = 8). (b) PBMC were stimulated 48 h in the presence or absence of proteinase K treated, heat treated and control Lactobacillus-CFS whereby relative secreted levels of IFN-γ was analysed, (n = 8). (c) PBMC were stimulated 48 h in the presence or absence of delipidated or control Lactobacillus-CFS whereby relative secreted levels of IFN-γ was analysed (n = 8). Shown are medians with interquartile range.

Results

Lactobacilli dampen IFN-γ responses by induction of a monocyte-derived soluble inhibitor

We have previously shown that cell free supernatants (CFS) from lactobacilli grown in their regular MRS medium dampen IFN-γ and IL-17A responses from T- and NK cells17,20. In the present study we cultivated the lactobacilli in modified cell culture medium, a more physiologically relevant medium for immune cells. PBMC cultured in the presence of CFS from L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) or L. reuteri DSM 17938 secreted IL-6 and IL-10 (Fig. 1a), showing that lactobacilli promote secretion of innate cytokines when grown in cell culture medium. Furthermore, both LGG- and L. reuteri-CFS significantly dampened S. aureus-induced IFN-γ and IL-17A secretion (Fig. 1b), suggesting that lactobacilli have the capacity to promote innate responses while suppressing adaptive inflammatory responses.

Activation of T- and NK cells is regulated by innate APC such as monocytes43,44. We therefore investigated whether the lactobacilli-mediated dampening of IFN-γ requires the presence of monocytes or B cells. We depleted PBMC of either monocytes or B cells or isolated pure T cells, prior to stimulation with a T cells specific activator towards CD3/CD28 alone or in combination with LGG-CFS. Depletion of B cells did not affect the IFN-γ-dampening activity while depletion of monocytes completely abolished the LGG-CFS-mediated IFN-γ suppression. In accordance with this, the LGG-CFS was not able to dampen IFN-γ secretion in pure T cell cultures (Fig. 1c). Next, we sought to investigate if the monocyte-dependent dampening of IFN-γ required physical contact between the monocyte and the IFN-γ-producing cell. We isolated and primed monocytes for 6 h with LGG-CFS, thoroughly washed and incubated them in fresh cell culture medium for an additional 14 h. The conditioned medium from the LGG-primed monocytes was subsequently added to stimulated autologous PBMC cultures. We observed a significant reduction in IFN-γ secretion by the monocyte-conditioned medium in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1d), suggesting that LGG dampens IFN-γ responses by inducing a monocyte-derived soluble inhibitor.

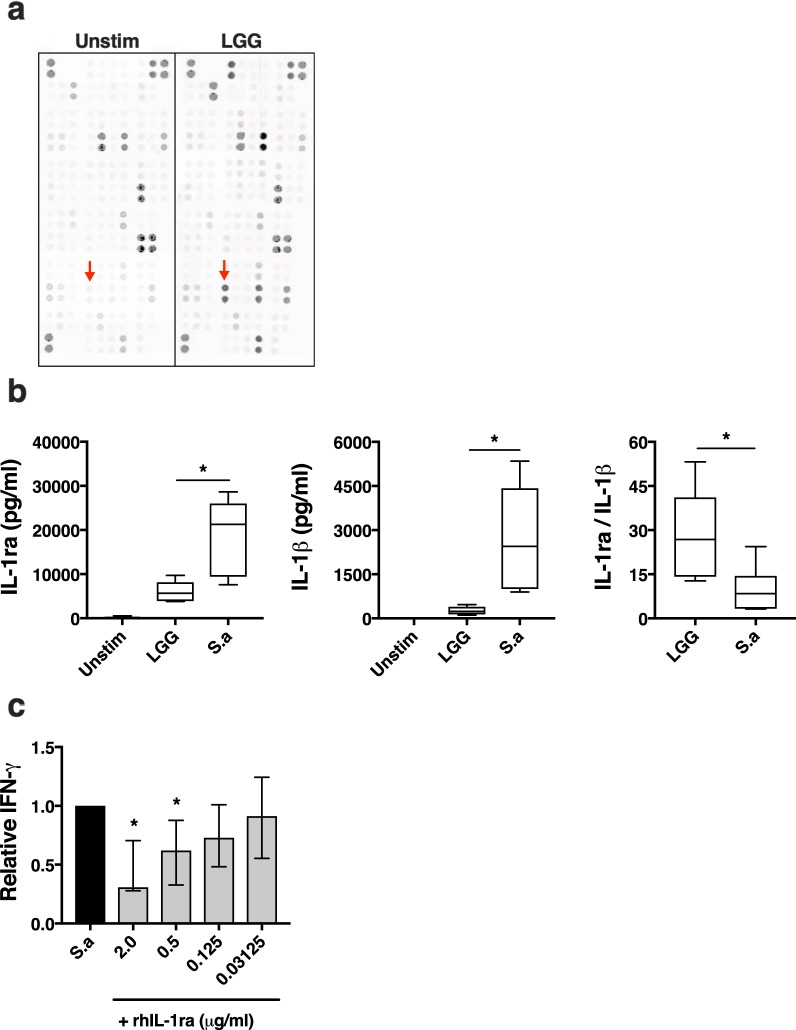

Lactobacillus-primed monocytes secrete IL-1ra

In order to identify the IFN-γ suppressive monocyte-derived factor, the monocyte-conditioned medium was analysed on a proteomic array. Only twelve of the measured factors were increased in LGG-treated samples compared with unstimulated conditions (Table 1), of which IL-1ra was the candidate molecule that was most likely to exert immune regulatory effects on T cells (Fig. 2a). IL-1ra is an antagonistic inhibitor of the pro-inflammatory IL-1 signalling pathway and it has been shown to reduce IFN-γ secretion45. We observed significantly higher levels of IL-1ra in response to S. aureus alone compared to LGG, however, S. aureus also induced significantly more IL-1β. In fact, we found that LGG alone induced a 3-fold higher ratio of IL-1ra/IL-1β than S. aureus alone (Fig. 2b), indicating that LGG favours an anti-inflammatory IL-1 signalling pathway. Finally, supplementation of recombinant IL-1ra to S. aureus stimulated PBMC resulted in reduced IFN-γ levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2c). Collectively, these data indicate that lactobacilli promote the anti-inflammatory IL-1ra signalling pathway and that this may contribute to their IFN-γ-dampening effect.

Table 1.

Proteome Profiler Array results of supernatants obtained from LGG-treated or unstimulated isolated human monocytes.

| Protein | LGG-treated monocytes | Unstimulated monocytes |

|---|---|---|

| Increased as compared to unstimulated | Detected | |

| CXCL5 | Yes | Yes |

| CCL2 | Yes | Yes |

| uPAR | Yes | Yes |

| MMP-9 | Yes | Yes |

| CXCL1 | Yes | No |

| CCL7 | Yes | No |

| CCL20 | Yes | No |

| IL-1ra | Yes | No |

| IL-6 | Yes | No |

| IL-10 | Yes | No |

| Angiopoietin-2 | Yes | No |

| MIP-1α/β | Yes | No |

Figure 2.

LGG-CFS induces IL-1ra from isolated monocyte cultures. Evaluation of the involvement of IL-1ra in suppression of IFN-γ production. (a) A membrane based cytokine array of the LGG-CFS primed monocyte-conditioned medium compared with unstimulated monocytes. Duplicate spots are positioned vertically and red arrows indicate IL-1ra. Shown is one representative membrane from two separate experiments. (b) Quantification of IL-1ra secretion (left), IL-1β secretion (middle) and the ratio of IL-1ra over IL-1β secretion (right) from PBMC cultures, (n = 6). (c) Quantification of IFN-γ secretion from S. aureus (S.a)-CFS stimulated PBMC in the presence of recombinant human (rh) IL-1ra. Box plots show the 25th and the 75th percentile with median value as the central line and whiskers show min-to-max. Bar plot shows median with interquartile range.

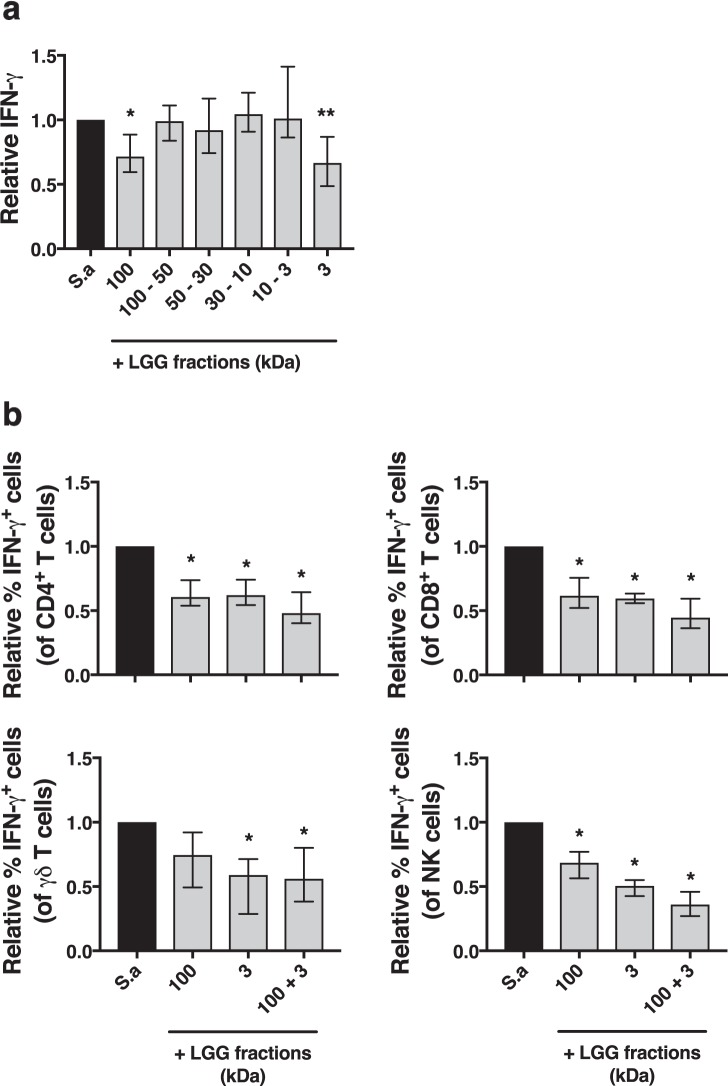

Lactobacilli dampen IFN-γ in T cells and NK cells through multiple factors of different molecular size

Several components of lactobacilli have been shown to be important for host cell interactions, in particular proteins, nucleic acids, PGN and SCFA26,46,47. In order to isolate the factors that mediate the IFN-γ dampening activity, we subjected the lactobacilli-CFS to size exclusion fractionation generating multiple fractions spanning from less than 3 kDa to larger than 100 kDa in molecular weight (Mw) and stimulated PBMC in the presence of each isolated fraction and measured secretion of IFN-γ. Two fractions of the LGG-CFS, the 3 kDa (from hereinafter referred to as “low Mw fraction”) and the 100 kDa (from hereinafter referred to as “high Mw fraction”), were able to dampen S. aureus-induced IFN-γ production (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, the dampening activity of the L. reuteri-CFS was also confined within the same two fractions of the CFS as for LGG (data not shown), suggesting that the mechanism of cytokine modulation is conserved between both species. Finally, we analysed IFN-γ expression on a cellular level using flow cytometry and found that both the high and the low Mw fractions significantly reduced the frequency of IFN-γ expressing cells within the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell, γδ T cell and NK cell populations (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Size fractionation of lactobacilli-CFS reveals multiple factors with IFN-γ dampening activity. Spin-column fractionation was employed to generate fractions of the LGG-CFS ranging from larger than 100 kDa to smaller than 3 kDa in molecular weight, whereby the IFN-γ dampening capacity of each fraction was evaluated on PBMC stimulated 48 h with S. aureus (S.a)-CFS. (a) Quantification of secreted levels of IFN-γ from stimulated PBMC normalized to S.a-CFS alone, (n = 8). (b) Flow cytometric analyses of intracellular IFN-γ expression in CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells and NK cells normalized to S.a-CFS alone, (n = 6). Shown are medians with interquartile range.

The lactobacilli-CFS high Mw fractions contain a heat sensitive lipid-based factor

During size fractionation, lactobacilli-derived metabolites and small compounds end up in the low Mw fraction of the CFS. We here focused our attention on the cytokine modulating capacity of the high Mw fraction. In order to increase the resolution of the fractionation, the high Mw fraction was further fractionated using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). An additional 30 fractions were generated and tested for IFN-γ dampening activity on S. aureus- stimulated PBMC. We identified two consecutive fractions, named J and K, which consistently dampened IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, comparing the protein absorption chromatogram with the ability to dampen IFN-γ, fractions J and K was found to completely match the first protein peak to be eluted from the HPLC column, which indeed was absent in the growth medium control (See Supplementary Fig. S1). Importantly, the protein absorption chromatogram from LGG and L. reuteri looked near identical, further supporting that the IFN-γ-dampening elicited by both species involved the same factor and mechanism. In order to further characterize the isolated factor, we subjected the lactobacilli-CFS to protein digestion using agarose-immobilized proteinase K followed by size fractionation with a 100 kDa filter and assessed the IFN-γ dampening activity of the proteinase K treated high Mw fraction on S. aureus-stimulated PBMC. Interestingly, no difference in the ability of LGG or L. reuteri to dampen IFN-γ was observed after proteinase K treatment. Heat inactivation of the L. reuteri-CFS, but not LGG-CFS, prior to stimulations abolished the mediated IFN-γ dampening (Fig. 4b). The lactobacilli-CFS was treated with a lipid adsorption matrix to remove all lipids, including extracellular membrane vesicles (MVs) that are enclosed by a lipid membrane, before being added to stimulated PBMC. Indeed, the IFN-γ dampening was lost for both LGG and L. reuteri after lipid removal (Fig. 4c).

Lactobacilli-derived extracellular MVs dampen IFN-γ and IL-17A secretion

Lactobacilli are known to produce MVs48 and these bacterial MVs are also know to contain membrane integrated proteins as well as intravesicular proteins that, due to the membrane enclosure, are protected from enzymatic digestion while still susceptible to heat inactivation49. We isolated MVs from both species of lactobacilli and a physiochemical characterization of the L. reuteri-MVs revealed a size distribution ranging from 100 nm to 400 nm in diameter, with an average size of 214 nm (Fig. 5a) and contained proteins, DNA and RNA (Fig. 5b). In order to test whether the MVs are responsible for the cytokine-modulatory effect observed with the lactobacilli-high Mw fraction, isolated MVs were added to PBMC at a MV-to-cell ratio of 500:1, 100:1 and 20:1 and incubated for 48 h. The cell culture supernatants were collected and analysed for induction of cytokines using ELISA. The L. reuteri-MVs clearly induced the production of both IL-6 and IL-10 in a concentration dependent manner, while no IFN-γ or IL-17A was detected (Fig. 5c). Moreover, adding isolated MVs to S. aureus-stimulated PBMC significantly dampened IFN-γ and IL-17A secretion to a similar extent as the CFS-high Mw fraction (Fig. 5d). Again, a substantial dampening of IFN-γ and IL-17A was also observed using LGG-derived MVs (data not shown).

Discussion

In the current study, we aimed to explore the underlying mechanism behind the cytokine-modulatory effects of lactobacilli. Here we show that lactobacilli produce soluble factors that induce the production and secretion of chemokines (Table 1) and cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 from PBMC cultures. We identify extracellular MVs as being one of the main contributors to both the immune-stimulatory and immune-dampening activity of the lactobacilli-CFS, possibly by increasing the relative abundance of IL-1ra to IL-1β by a monocyte-dependent mechanism.

Lactobacilli and its components have been shown to influence T cell differentiation and proliferation in a T cell intrinsic manner. Lactobacillus-derived RNA suppress CD4+ T cell proliferation in the absence of APC28 and SCFA increase extrathymic generation of Treg cells by promoting acetylation of the foxp3 gene locus within the naïve T cell population itself34. In the current study, we also investigated whether the lactobacilli-CFS-mediated dampening of IFN-γ was dependent solely on T cell intrinsic factors or not. Interestingly, IFN-γ dampening was fully dependent on the presence of monocytes since the Lactobacillus-CFS had no effect on IFN-γ production from isolated T cell or monocyte-depleted PBMC cultures (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, we observed a significant level of dampening by using Lactobacillus-primed monocyte-conditioned medium alone, confirming that the dampening mechanism is cell-to-cell contact independent.

Innate cells are known to regulate lymphocyte activation through soluble mediators50. IL-10 is a regulatory cytokine with an important role in preventing excessive inflammation by increasing Treg cell function and reducing inflammatory cytokine responses. Lactobacilli-induced IL-10 is described as an important mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of probiotic bacteria on excessive immune activation51,52. However, neutralizing IL-10 does not affect the ability of lactobacilli-CFS to dampen IFN-γ production from stimulated PBMC17. Moreover, studies in IL-10 KO mice models show that lactobacilli can still modulate immune responses and ameliorate intestinal inflammation by an IL-10-independent mechanism53,54, indicating multiple mechanisms of action involving lactobacilli-mediated immune modulation. IL-1ra is another anti-inflammatory cytokine that suppress immune activation by antagonistic competition with IL-1α/β signalling. IL-1 signalling is important for both T- and NK cells effector responses, in particular for IL-17A and IFN-γ production, respectively55,56. IL-1β has also been identified as a driver of inflammation in (certain) intestinal inflammatory diseases57 and neutralizing IL-1β using IL-1ra inhibits fungal-induced IFN-γ responses45. In the current study we confirmed IL-1ra production from PBMC cultured with either Lactobacillus-CFS or S. aureus-CFS. However, Lactobacillus-CFS induced minimal levels of IL-1β (Fig. 2b), while S. aureus induced significantly larger amounts of IL-1β. In fact, Lactobacillus-CFS treatment resulted in a 3-fold higher ratio of IL-1ra/IL-1β compared with S. aureus-CFS. Moreover, adding recombinant IL-1ra to S. aureus-stimulated PBMC resulted in suppressed IFN-γ responses, supporting the involvement of IL-1 signalling in Lactobacillus-mediated dampening of induced IFN-γ.

In a previous study, we confirmed the IFN-γ-dampening effect of lactate, specifically on unconventional mucosal associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, γδ T cells and NK cells but not conventional T cells. Here, we showed that the low fraction of the Lactobacillus-CFS, containing only molecules of less than 3 kDa in molecular weight, was able to dampen IFN-γ production in all T cell subtypes including conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. This indicates that lactobacilli produce low molecular weight molecules, other than lactate, capable of modulating pro-inflammatory responses in T cells. Lactobacilli produce several SCFA such as propionate, acetate and butyrate with known effects on host physiology and immunity34.

Lactobacillus is a highly heterogeneous genus with immune stimulatory activity that varies between species and strains58,59. Interestingly, the immune dampening activity we observed in our setting was conserved across species and strains (See Supplementary Fig. S2). The ability to produce extracellular MVs is also a generally conserved trait as it has been found among multiple bacterial genera, species and strains60. Treatment of the lactobacilli-CFS high Mw fraction with a lipid removal agent rendered both LGG and L. reuteri incapable of modulating IFN-γ production, indicating that MVs are involved for both species tested. Proteinase K treatment of the L. reuteri-CFS high Mw fraction had no impact on IFN-γ-dampening while heat inactivation did, suggesting that the MV-dampening involves delivery of intravesicular protein cargo to the target cells. On the other hand, heat inactivation of the LGG-CFS high Mw fraction did not abolish the dampening effect to a significant level, suggesting that there are differences in the MV-mediated modulation of cytokine responses between LGG and L. reuteri. Recently, bacterial MVs have been implicated in a broad range of functions in relation to bacteria-host interaction. MVs from Lactobacillus have been shown to inhibit hepatic cancer growth61, protect against S. aureus-induced atopic dermatitis62 and upregulate host immune gene transcription associated with defence against pathogenic infections63. The exact mechanism behind bacterial MV-associated host modulation is still not clear. MVs isolated from Bifidobacterium longum is internalized by mast cells in a phagocytosis-independent mechanism64, while MVs isolated from L. sakei subsp. sakei enhance IgA production by activation of Toll-like receptor 2 signalling65. Whether or not the MVs are taken up by the monocytes or interact solely with surface receptors, in our settings, remains to be investigated. Moreover, a protein analysis of purified Lactobacillus-derived MVs revealed the presence of several proteins (p40, p75) with known probiotic effects66. Indeed, the MVs, which we isolated from L. reuteri, did contain proteins and nucleic acids (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, gut bacteria-derived MVs have been isolated from peripheral blood, and the circulating MV-profile has been associated with neurodegenerative disease67, strengthening the relevance of our findings.

Collectively, we have shown that lactobacilli secrete multiple immunomodulatory factors with the capacity to counteract lymphocytic pro-inflammatory cytokine production by promoting monocyte-derived IL-1ra. Additionally, we identified Lactobacillus-produced extracellular MVs as a significant component for the cytokine regulatory effects observed, extending the general knowledge of bacteria-host interactions, which could bring new implications for future probiotic design.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (grant no 2016-01715_3), The Cancer and Allergy Foundation, The Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association’s Research Foundation, Mjölkdroppen Foundation, The Engkvist Foundations, The Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation (Freemasons of Sweden), Carl Trygger Foundation, The Swedish Cancer Foundation and Stockholm University.

Author contributions

Designed the study and experiments: M.M.F., S.B. and E.S.E. Performed the experiments: M.M.F., S.B., Y.P., L.L., I.B.E. and M.C.J. Performed data and statistical analyses: M.M.F. Contributed reagents and material: M.M.F., M.N., M.O., Y.P., L.L., S.R. and E.S.E. Wrote the manuscript: M.M.F. and E.S.E. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

Authors S.R and L.L are currently employed by the company BioGaia AB. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sophia Björkander and Yanhong Pang.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-53576-6.

References

- 1.Martin R, et al. Early life: gut microbiota and immune development in infancy. Beneficial microbes. 2010;1:367–382. doi: 10.3920/BM2010.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46:562–576. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamsson TR, et al. Low gut microbiota diversity in early infancy precedes asthma at school age. Clinical and experimental allergy: journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014;44:842–850. doi: 10.1111/cea.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahenzli J, Koller Y, Wyss M, Geuking MB, McCoy KD. Intestinal microbial diversity during early-life colonization shapes long-term IgE levels. Cell host & microbe. 2013;14:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakobsson HE, et al. Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by caesarean section. Gut. 2014;63:559–566. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lathrop SK, et al. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 2011;478:250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson MA, Sjogren YM, Persson JO, Nilsson C, Sverremark-Ekstrom E. Early Colonization with a Group of Lactobacilli Decreases the Risk for Allergy at Five Years of Age Despite Allergic Heredity. PloS one. 2011;6:e23031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder BO, Backhed F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nature medicine. 2016;22:1079–1089. doi: 10.1038/nm.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li F, et al. The microbiota maintain homeostasis of liver-resident gammadeltaT-17 cells in a lipid antigen/CD1d-dependent manner. Nature communications. 2017;7:13839. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill C, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014;11:506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Broek MFL, De Boeck I, Claes IJJ, Nizet V, Lebeer S. Multifactorial inhibition of lactobacilli against the respiratory tract pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis. Beneficial microbes. 2018;9:429–439. doi: 10.3920/BM2017.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossoni RD, et al. Antifungal activity of clinical Lactobacillus strains against Candida albicans biofilms: identification of potential probiotic candidates to prevent oral candidiasis. Biofouling. 2018;34:212–225. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2018.1425402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostad SN, et al. Live and heat-inactivated lactobacilli from feces inhibit Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli adherence to Caco-2 cells. Folia microbiologica. 2009;54:157–160. doi: 10.1007/s12223-009-0024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Hao-Yu, Roos Stefan, Jonsson Hans, Ahl David, Dicksved Johan, Lindberg Jan Erik, Lundh Torbjörn. Effects of Lactobacillus johnsonii and Lactobacillus reuteri on gut barrier function and heat shock proteins in intestinal porcine epithelial cells. Physiological Reports. 2015;3(4):e12355. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel RM, et al. Probiotic bacteria induce maturation of intestinal claudin 3 expression and barrier function. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsubara VH, et al. Probiotic Bacteria Alter Pattern-Recognition Receptor Expression and Cytokine Profile in a Human Macrophage Model Challenged with Candida albicans and Lipopolysaccharide. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:2280. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson MA, et al. Probiotic Lactobacilli Modulate Staphylococcus aureus-Induced Activation of Conventional and Unconventional T cells and NK. Cells. Frontiers in immunology. 2016;7:273. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villena J, Kitazawa H. Modulation of Intestinal TLR4-Inflammatory Signaling Pathways by Probiotic Microorganisms: Lessons Learned from Lactobacillus jensenii TL2937. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;4:512. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemgang TS, Kapila S, Shanmugam VP, Kapila R. Cross-talk between probiotic lactobacilli and host immune system. Journal of applied microbiology. 2014;117:303–319. doi: 10.1111/jam.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haileselassie Y, et al. Lactobacilli Regulate Staphylococcus aureus 161:2-Induced Pro-Inflammatory T-Cell Responses In Vitro. PloS one. 2013;8:e77893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smelt MJ, et al. L. plantarum, L. salivarius, and L. lactis attenuate Th2 responses and increase Treg frequencies in healthy mice in a strain dependent manner. PloS one. 2012;7:e47244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peluso I, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei B21060 suppresses human T-cell proliferation. Infection and immunity. 2007;75:1730–1737. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01172-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pena JA, Versalovic J. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG decreases TNF-alpha production in lipopolysaccharide-activated murine macrophages by a contact-independent mechanism. Cellular microbiology. 2003;5:277–285. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.t01-1-00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosseini Nezhad M, Hussain MA, Britz ML. Stress Responses in Probiotic Lactobacillus casei. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2015;55:740–749. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.675601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nezhad MH, Knight M, Britz ML. Evidence of changes in cell surface proteins during growth of Lactobacillus casei under acidic conditions. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2012;21:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s10068-012-0033-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macho Fernandez E, et al. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut. 2011;60:1050–1059. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.232918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasuda E, Serata M, Sako T. Suppressive effect on activation of macrophages by Lactobacillus casei strain shirota genes determining the synthesis of cell wall-associated polysaccharides. Appl Environ Microb. 2008;74:4746–4755. doi: 10.1128/Aem.00412-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida A, et al. Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2809 and its RNA suppress proliferation of CD4(+) T cells through a MyD88-dependent signalling pathway. Immunology. 2011;133:442–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iliev ID, et al. Strong immunostimulation in murine immune cells by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG DNA containing novel oligodeoxynucleotide pattern. Cellular microbiology. 2005;7:403–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iliev ID, et al. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotide containing TTTCGTTT motif from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG DNA potentially suppresses OVA-specific IgE production in mice. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2008;67:370–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, et al. An LGG-derived protein promotes IgA production through upregulation of APRIL expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Mucosal immunology. 2017;10:373–384. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan F, et al. Colon-specific delivery of a probiotic-derived soluble protein ameliorates intestinal inflammation in mice through an EGFR-dependent mechanism. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2242–2253. doi: 10.1172/JCI44031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taverniti V, et al. S-layer protein mediates the stimulatory effect of Lactobacillus helveticus MIMLh5 on innate immunity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1221–1231. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03056-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arpaia N, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aldunate M, et al. Antimicrobial and immune modulatory effects of lactic acid and short chain fatty acids produced by vaginal microbiota associated with eubiosis and bacterial vaginosis. Frontiers in physiology. 2015;6:164. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akdis M, et al. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor beta, and TNF-alpha: Receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016;138:984–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinteiro-Filho WM, Brisbin JT, Hodgins DC, Sharif S. Lactobacillus and Lactobacillus cell-free culture supernatants modulate chicken macrophage activities. Research in Veterinary Science. 2015;103:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashraf R, Vasiljevic T, Smith SC, Donkor ON. Effect of cell-surface components and metabolites of lactic acid bacteria and probiotic organisms on cytokine production and induction of CD25 expression in human peripheral mononuclear cells. Journal of dairy science. 2014;97:2542–2558. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menard S, et al. Lactic acid bacteria secrete metabolites retaining anti-inflammatory properties after intestinal transport. Gut. 2004;53:821–828. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.026252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosander A, Connolly E, Roos S. Removal of antibiotic resistance gene-carrying plasmids from Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and characterization of the resulting daughter strain, L. reuteri DSM 17938. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6032–6040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00991-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosengren A, Fabricius A, Guss B, Sylven S, Lindqvist R. Occurrence of foodborne pathogens and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus in cheese produced on farm-dairies. International journal of food microbiology. 2010;144:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zauberman A, et al. Host Iron Nutritional Immunity Induced by a Live Yersinia pestis Vaccine Strain Is Associated with Immediate Protection against Plague. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2017;7:277. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bieber K, Autenrieth SE. Insights how monocytes and dendritic cells contribute and regulate immune defense against microbial pathogens. Immunobiology. 2015;220:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerosa F, et al. Interleukin-12 primes human CD4 and CD8 T cell clones for high production of both interferon-gamma and interleukin-10. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;183:2559–2569. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warris A, et al. Cytokine responses and regulation of interferon-gamma release by human mononuclear cells to Aspergillus fumigatus and other filamentous fungi. Medical mycology. 2005;43:613–621. doi: 10.1080/13693780500088333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maudsdotter L, Jonsson H, Roos S, Jonsson AB. Lactobacilli reduce cell cytotoxicity caused by Streptococcus pyogenes by producing lactic acid that degrades the toxic component lipoteichoic acid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1622–1628. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00770-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghadimi D, et al. Effects of probiotic bacteria and their genomic DNA on TH1/TH2-cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy and allergic subjects. Immunobiology. 2008;213:677–692. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dean SN, Leary DH, Sullivan CJ, Oh E, Walper SA. Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus-derived membrane vesicles. Scientific reports. 2019;9:877. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37120-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCaig WD, Loving CL, Hughes HR, Brockmeier SL. Characterization and Vaccine Potential of Outer Membrane Vesicles Produced by Haemophilus parasuis. PloS one. 2016;11:e0149132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain A, Pasare C. Innate Control of Adaptive Immunity: Beyond the Three-Signal Paradigm. Journal of immunology. 2017;198:3791–3800. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1602000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Giacinto C, Marinaro M, Sanchez M, Strober W, Boirivant M. Probiotics ameliorate recurrent Th1-mediated murine colitis by inducing IL-10 and IL-10-dependent TGF-beta-bearing regulatory cells. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:3237–3246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Moreno de Leblanc A, et al. Importance of IL-10 modulation by probiotic microorganisms in gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases. ISRN gastroenterology. 2011;2011:892971. doi: 10.5402/2011/892971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pena JA, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus spp. diminish Helicobacter hepaticus-induced inflammatory bowel disease in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:912–920. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.912-920.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCarthy J, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled trial of two probiotic strains in interleukin 10 knockout mice and mechanistic link with cytokine balance. Gut. 2003;52:975–980. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cooper MA, et al. Interleukin-1beta costimulates interferon-gamma production by human natural killer cells. European journal of immunology. 2001;31:792–801. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<792::AID-IMMU792>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jain A, Song R, Wakeland EK, Pasare C. T cell-intrinsic IL-1R signaling licenses effector cytokine production by memory CD4 T cells. Nature communications. 2018;9:3185. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coccia M, et al. IL-1beta mediates chronic intestinal inflammation by promoting the accumulation of IL-17A secreting innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) Th17 cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:1595–1609. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsieh PS, et al. Potential of probiotic strains to modulate the inflammatory responses of epithelial and immune cells in vitro. The new microbiologica. 2013;36:167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fink LN, et al. Distinct gut-derived lactic acid bacteria elicit divergent dendritic cell-mediated NK cell responses. International immunology. 2007;19:1319–1327. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JH, Lee J, Park J, Gho YS. Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial extracellular vesicles. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2015;40:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Behzadi E, Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini H, Imani Fooladi AA. The inhibitory impacts of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-derived extracellular vesicles on the growth of hepatic cancer cells. Microbial pathogenesis. 2017;110:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim MH, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum-derived Extracellular Vesicles Protect Atopic Dermatitis Induced by Staphylococcus aureus-derived Extracellular Vesicles. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2018;10:516–532. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.5.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li M, et al. Lactobacillus-derived extracellular vesicles enhance host immune responses against vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Bmc Microbiol. 2017;17:66. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-0977-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JH, et al. Extracellular vesicle-derived protein from Bifidobacterium longum alleviates food allergy through mast cell suppression. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016;137:507–516 e508. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamasaki-Yashiki S, Miyoshi Y, Nakayama T, Kunisawa J, Katakura Y. IgA-enhancing effects of membrane vesicles derived from Lactobacillus sakei subsp. sakei NBRC15893. Bioscience of microbiota, food and health. 2019;38:23–29. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.18-015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dominguez Rubio AP, et al. Lactobacillus casei BL23 Produces Microvesicles Carrying Proteins That Have Been Associated with Its Probiotic Effect. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:1783. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park JY, et al. Metagenome Analysis of Bodily Microbiota in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease Using Bacteria-derived Membrane Vesicles in Blood. Experimental neurobiology. 2017;26:369–379. doi: 10.5607/en.2017.26.6.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.