Abstract

Anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit inflammation, particularly those classified as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Several studies have reported that propolis has both anti-ulcerogenic and anti-inflammatory effects. In this study, we investigated the bioactive compound and in vivo anti-inflammatory properties of both smooth and rough propolis from Tetragronula sp. To further identify anti-inflammatory markers in propolis, LC-MS/MS was used, and results were analyzed by Mass Lynx 4.1. Rough and smooth propolis of Tetragonula sp. were microcapsulated with maltodextrin and arabic gum. Propolis microcapsules at dose 25–200 mg/kg were applied for carrageenan-induced rat’s paw-inflammation model. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis statistical tests. LC-MS/MS experiments identified seven anti-inflammatory compounds, including [6]-dehydrogingerdione, alpha-tocopherol succinate, adhyperforin, 6-epiangustifolin, deoxypodophyllotoxin, kurarinone, and xanthoxyletin. Our results indicated that smooth propolis at 50 mg/kg inhibited inflammation to the greatest extent, followed by rough propolis at a dose of 25 mg/kg. SPM and RPM with the dose of 25 mg/kg had inflammatory inhibition value of 62.24% and 58.12%, respectively, which is comparable with the value 70.26% of sodium diclofenac with the dose of 135 mg/kg. This study suggests that propolis has the potential candidate to develop as a non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, Edema, In vivo, Rough propolis, Soft propolis, Tetragonula sp

1. Introduction

Anti-inflammatory drugs are classified as agents that either inhibit or reduce inflammation, which can occur as a result of physical injury, infection, heat, and antigen–antibody interactions (Fullerton and Gilroy, 2016, Houglum and Harrelson, 2011). Based on mechanistic studies, anti-inflammatory drugs can be divided into two types, namely, steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs, including aspirin, acetaminophen, diclofenac sodium, and ibuprofen, represent the most common type of anti-inflammatory drug. However, NSAIDs can cause additional effects that are ulcerogenic (Domiati et al., 2016, Hawkey and Langman, 2003).

Propolis is a resin material collected by bees from plant exudate and plant shoots. The name propolis is Greek; pro means fortress and polis means city. Bees use propolis in a number of ways, including to smooth the wall of the beehive, to protect them from disease, and to cover carcasses and prevent their decomposition (Bankova et al., 2000). Propolis is also well known as a traditional medicine for treating many diseases. The biological activities of propolis include its actions as an antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotector (Mahadewi et al., 2018, Pratami et al., 2018, Sahlan et al., 2017, Sahlan and Supardi, 2013, Soekanto et al., 2018). Accordingly, propolis extract has been widely used as a beverage, nutritional supplement, and an added ingredient in food. The main contents of propolis are flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolic acid, cinnamic acid, cafeic acid, and various esters (Bankova, 2005, Bittencourt et al., 2015).

Previous studies of Brazilian, South African, Japanese, and Chinese propolis have shown that propolis possesses anti-inflammatory effects. The anti-inflammatory compound identified in Brazilian propolis is artepillin C (Paulino et al., 2008). For South African propolis, the identified anti-inflammatory compounds include galangin and quercetin, whereas Chinese propolis has been shown to have glycerol esters as anti-inflammatory compounds (Du Toit et al., 2009, Shi et al., 2012).

Recent research conducted by Paulino et al. (2015) compared the anti-inflammatory effects of sodium diclofenac and propolis. Both compounds demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects; however, sodium diclofenac can cause ulcerogenic disease. However, additional research has indicated that propolis may inhibit the formation of ulcers caused by sodium diclofenac (Paulino et al., 2015).

In Indonesia, investigations of the anti-inflammatory effects of propolis, particularly the identification of anti-inflammatory biomarkers in propolis, are limited. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory properties of Indonesian propolis. Collectively, our findings indicate that propolis may be a promising alternative to NSAIDs, with both anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcerogenic effects.

2. Methodology/experimental

2.1. Material

Two samples of ethanolic extracts of propolis (EEP), consisting of soft propolis (taken from inside the nest) and rough propolis (taken from outside the nest), were used as active ingredients for microencapsulation. Propolis samples from Tetragonula sp were taken from Masamba, North of the Luwu district, in the South Sulawesi Province of Indonesia. Maltodextrin 97 dextrose equivalent (DE) 18 and gum arabic 98 were obtained from Brataco Co. (Indonesia). n-Hexane, ethyl acetate, and acetic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Identification of anti-inflammatory compounds

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted to obtain the optimal sample. The solvent and the eluent phase consisted of ethyl acetate and a mixture of n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and acetic acid (31:14:5), respectively. The results obtained from TLC were injected into the LC-MS/MS instrumentation, and the data were analyzed using Mass Lynx 4.1 software. Analytical LC-MS/MS experiments were performed using an ACQUITY UPLC I-Class System connected through a split to a Xevo G2-XS Q-tof Mass Spectrometer (Waters, USA) in the police laboratory and forensics, Jakarta, Indonesia.

2.3. Propolis microencapsulation

Extract ethanol propolis (EEP) was prepared from smooth and rough propolis extracted with 96% ethanol using the method described in Pratami et al. (2018). Microencapsulation using maltodextrin and gum arabic as described by Da Silva (2013) and Marquiafável (2015), with some modifications (Da Silva et al., 2013, Marquiafável et al., 2015). First, 10 g of maltodextrin, 1 g of arabic gum, and 100 mL aquadest were mixed with a magnetic stirrer for 5 min. The mixture was then homogenized using a homogenizer ultra-turrax T18 (IKA, Germany) at a speed of 6,000 rpm for 30 min. Then, 300 mL of EEP was added and mixed at a speed of 15,000 rpm for 2 min. Finally, the mixture was dried using a spray dry method (Büchi B290, Flawil, Switzerland). The operational conditions of the spray dryer were as follows, aspirator 100%; spray gas 600 L/min; nozzle diameter: 1.5 mm; sample feed rate: 25%; and inlet temperature 110 °C. Morphology of Spray-dried propolis (SDP) microcapsules was observed by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) in Central Forensic Laboratory (PUSLABFOR) Jakarta Indonesia.

2.4. Ethical approval

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia-Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital (No. 0350/UN.2.FI/ETIK/2018).

2.5. Animals

A total of 53 fasted adult Sprague Dawley rat males (200–225 g) were used in the experiments. Before experiments were performed, animals were allowed to acclimate for as long as one week and had been fasted for ±18 h, with free access to water.

2.6. Solution test

There were seven test groups in this study, with 6–7 animals in each group. The negative control group was given 2 mL of Na CMC 0.5% (p.o), whereas the positive control group was given 135 mg/kg of sodium diclofenac (p.o). There were three doses used in this experiment for each propolis microcapsule solution in water, which were given to the animals orally. Doses for the soft propolis microcapsule (SPM) were 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg, whereas those of the rough propolis microcapsule (RPM) were 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg.

2.7. Measurement of paw edema

To measure paw edema, the animal’s paw was initially measured using a plethysmometer to obtain the initial paw volume. After that, the animals received a 0.2 mL carrageenan injection in one hind paw to induce inflammation. One hour after this injection, the test solution was given, and the subsequent paw volume was measured as V0. Measurements of paw volume were taken every hour for 5 h.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Before applying the statistical analysis method, the edema volume was calculated. Edema volume represented the deficiency of the initial volume (Vi) and paw volume per each time (Vt) (Eq. (1)). After the edema volume was calculated, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated (Eq. (2)), where t is the time interval of the measurement in an hour. The value of the AUC was then used to calculate the percentage of inflammatory inhibition (Eq. (3)), where AUCt represented the AUC treatment, whereas AUCnc was the AUC negative control.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The AUC value was also used for the statistical analysis. The AUC of the SPM was analyzed with the Kruskal–Wallis test and the Post-Hoc Mann–Whitney test. This test was applied due to the normalized distribution of the data. In contrast, the AUC of the RPM was analyzed by one-way ANOVA, with Post-Hoc LSD multiple comparison because the data were normal and homogeneous. This statistical analysis was developed using statistical software with confidence limits of 95%.

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Anti-inflammatory biomarker identification result

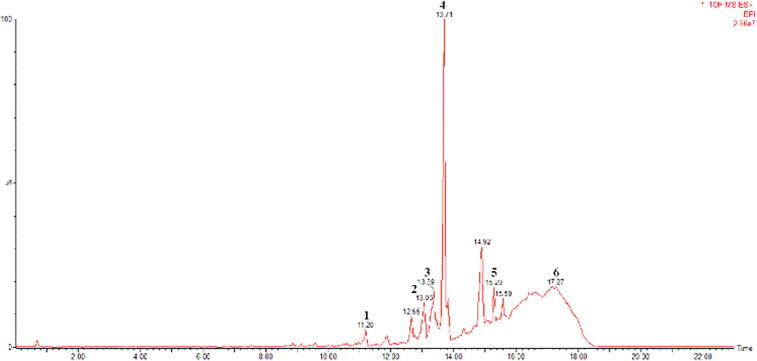

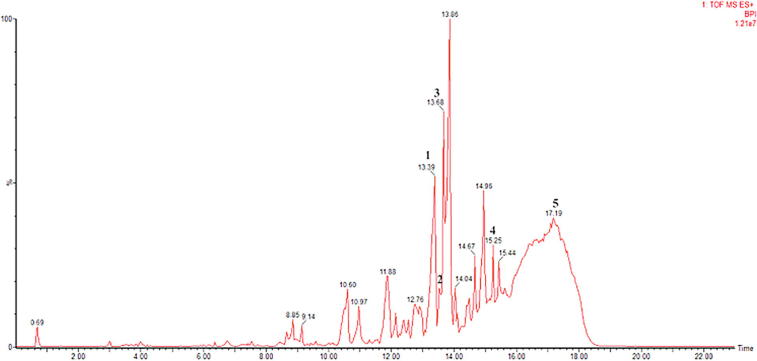

Chromatogram and mass spectra results from the LC-MS/MS experiments (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) were analyzed using Mass Lynx 4.1 software. In the mass spectra, the BPI (Base Peak Intensity) type of view was used. This was because BPI shows more detailed resolutions and the most intense peaks; thus the detection of compounds was easier and more accurate. The analytical parameters that we used in identifying biomarker were matches between the parent fragments and at least two child fragments from the results obtained with the literature. The parent fragment is a charged molecule that can dissociate to form fragments, while the fragments of the fragments from the parent fragments are fragments of the children. After the initial ionization, the parent ion would experience fragmentation, causing the release of free radicals or small neutral molecules. A molecular ion does not rupture randomly but tends to form the most stable fragments. The parameters in this test are similar with those of Troendle et al., 1999, Kivrak et al., 2016 that the presence of a compound can be confirmed if there were at least two child fragments, given that the m/z parent fragment was larger than the child fragment (Kivrak et al., 2016, Troendle et al., 1999). This can be used as a parameter because the fragmentation patterns were used to identify unknown compounds, as each molecule has a different pattern of fragmentation. The results of the LC-MS/MS identification can be seen in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

UPLC TOF MSE (50–1500) 4 eV ESI+-Low CE (BPI) Profile of Smooth Propolis (1) Deoxypodophyllotoxine, (2) Kurarinone, (3) 6-Dehydrogingerdione, (4) 6-Epiangustifolin, (5) dhyperforin, (6) alpha-Tocopherol Succinate.

Fig. 2.

UPLC TOF MSE (50–1500) 4 eV ESI+-Low CE (BPI) Profile of Rough Propolis (1) 6-Dehydrogingerdione, (2) Xanthoxyletin, (3) 6-Epiangustifolin, (4) Adhyperforin, (5) alpha-Tocopherol Succinate.

Table 1.

Propolis anti-inflammatory bioactive-compound identification results.

| Bioactive compounds | Category | Plant source | Chemical structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| [6]-Dehydrogingerdione | Methoxy phenol | Ginger (Zingiber officinale) |  |

| alpha-Tocopherol Succinate | Vitamin | Spinach, sunflower, and turnip |  |

| Adhyperforin | Phloroglucinol | Genus Hypericum |  |

| 6-Epiangustifolin | Diterpenoid | Genus Isodon |  |

| Deoxypodophyllotoxin | Lignan | Genus Podophyllum |  |

| Kurarinone | Flavonoid | Genus Sophora (legumes group) |  |

| Xanthoxyletin | Coumarin | Genus Zanthoxylum and Clausena |  |

In general, the anti-inflammatory mechanism of these molecules is through the NF-kB inhibition mechanism. NF-kB plays an important role in the formation of inflammatory mediators such as iNOS, COX-2, and TNF-α. Also, some compounds are known to have antioxidant properties, which can inhibit oxygen (radicals) actively, thereby reducing the oxidative stress triggers that can cause inflammation.

The other research conducted by Haiming Shi (2012) has identified has identified anti-inflammatory activities of the five new compounds of propolis from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The five glycerol esters including 2-acetyl-1-coumaroyl-3-cinnamoylglycerol, (+)-2-acetyl-1-feruloyl-3-cinnamoylglycerol, (-)-2-acetyl-1-feruloyl-3-cinnamoylglycerol, 2-acetyl-1,3-dicinnamoylglycerol, and (-)-2-acetyl-1-(E)-feruloyl-3-(3″(ζ),16″)-dihydroxy-palmitoylglycerol (Shi et al., 2012).

The chemical composition of Brazilian propolis from Apis sp has identified by Lima Cavendish et al. (2015) as isoflavones such as formononetin and biochanin A. Formononetin as biomarker of Brazilian propolis has potential anti-inflammatory activity on experimental models (Lima Cavendish et al., 2015). Therefore, Megumi Funakoshi-Tago (2015) found the components of Nepalese Propolis that exhibit anti-inflammatory activity. These results indicate that 3′,4′-dihydroxy-4-methoxydalbergione, 4-methoxydalbergion, cearoin, and chrysin were the substances responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity of Nepalese propolis (Funakoshi-Tago et al., 2015).

The compounds identified in this research also can be found in other propolis. Adhyperforin was part of ent-Kauranoids, which also can be found in propolis from a Brazillian stingless bee, Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioidese (Velikova et al., 2000). The derivative compound can be found in Cuba propolis (Piccinelli et al., 2009). Another compound was xanthoxyletin, which part of the coumarin. Through the several studies, this coumarin also can be found in Slovakian propolis (Hroboňová et al., 2013). Eventhough the rest of the compounds have not been identified in other propolis, it can be caused by biodiversity. Propolis is a bee product of plant origin, thus at different geographic locations the source plants might vary with respect to the local flora (Bankova, Popova, & Trusheva, 2014).

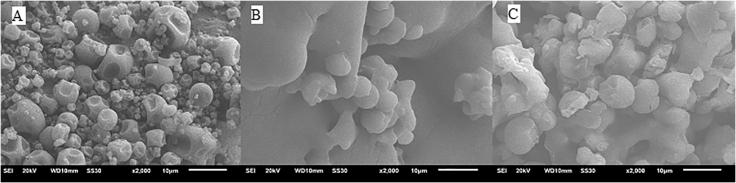

3.2. Propolis microencapsulation

In this work, propolis microcapsule powders were prepared by coating propolis with maltodextrin and gum arab using the spray-drying method. Maltodextrin with the DE value of 18 chosen as microencapsulation coating material, it has medium glucose chains and higher solubility. Encapsulation using maltodextrin–gum arabic (MD/GA) as microwall material represented a solution to overcome the problems related to their direct application (Rao et al., 2016). MD/GA offered the best protection in bioactive compounds in microencapsulation conducted (Alves et al., 2014). The gums as coating material added to the formulation to improve microencapsulation efficiency of some polyphenols with spray-drying (Busch et al., 2017).

Fig. 3 shows that morphologies of propolis microcapsules analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SDP microcapsules presented uniform spherical particles sizes ranging from 0.8 to 4 μm. The SEM images of SDP microcapsules was similar to those observed by Busch (2017), the microencapsulating improved the size uniformity and microparticles integrity, also showed better core material protection (Busch et al., 2017).

Fig. 3.

SEM Image of spray dried propolis powder. (A) microwall maltodextrin and gum arabic, (B) smooth propolis microcapsules, (C) rough propolis microcapsules.

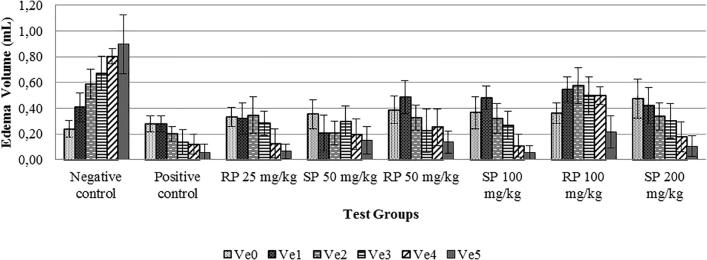

3.3. Doses effect on inflammatory inhibition

In vivo tests were performed to evaluate the anti-inflammatory properties of propolis. Inflammation was induced by carrageenan (Fig. 4A), and anti-inflammatory test results demonstrated rat paw volume changes in each test group (Table 2 and Fig. 4B). In the negative control group, the edema volume increased from 0 to 5 h and showed a different trend compared with the other groups. This occurred because there was not an active compound to inhibit the inflammatory response in the negative control group. Therefore, the edema increased each hour. For both types of propolis microencapsulation (SPM and RPM), a significant decrease in paw volume was observed, indicating an anti-inflammatory effect related to the SPM and RPM (Fig. 4C). This result of edema volume in rat paw per each test group represented that there were an anti-inflammatory compound in SPM and RPM (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Rat paw. (A) Before carrageenan injection, (B) after carrageenan injection, (C) after propolis provisioning.

Table 2.

The differences of edema volume per each hour.

| Test groups | Average edema Volume (mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ve0 | Ve1 | Ve2 | Ve3 | Ve4 | Ve5 | |

| Negative control | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | 0.67 ± 0.13 | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.23 |

| Positive control | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.09 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.06 |

| RPM 25 | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.12 | 0.34 ± 0.14 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.06 |

| SPM 50 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.30 ± 0.12 | 0.20 ± 0.13 | 0.15 ± 0.11 |

| RPM 50 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.48 ± 0.13 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | 0.22 ± 0.17 | 0.25 ± 0.14 | 0.14 ± 0.09 |

| SPM 100 | 0.36 ± 0.13 | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 0.27 ± 0.11 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.05 ± 0.06 |

| RPM 100 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.10 | 0.57 ± 0.14 | 0.50 ± 0.15 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.13 |

| SPM 200 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.14 | 0.34 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.10 ± 0.08 |

Note. RPM 25: Rough propolis microcapsule 25 mg/kg, SPM : Smooth propolis microcapsule 50 mg/kg, RPM 50: Rough propolis microcapsule 50 mg/kg, SPM 100: Smooth propolis microcapsule 100 mg/kg, RPM 100: Rough propolis microcapsule 100 mg/kg, SPM 200: Smooth propolis microcapsule 200 mg/kg, Ve0 = paw volume in 0 h. Ve0 = paw volume in 0 h. Ve1 = paw volume in 1 h. Ve2 = paw volume in 2 h. Ve3 = paw volume in 3 h. Ve4 = paw volume in 4 h. Ve5 = paw volume in 5 h.

Fig. 5.

Edema volume in rat paw per each test group (SP: smooth propolis microencapsulation, RP: rough propolis microencapsulation).

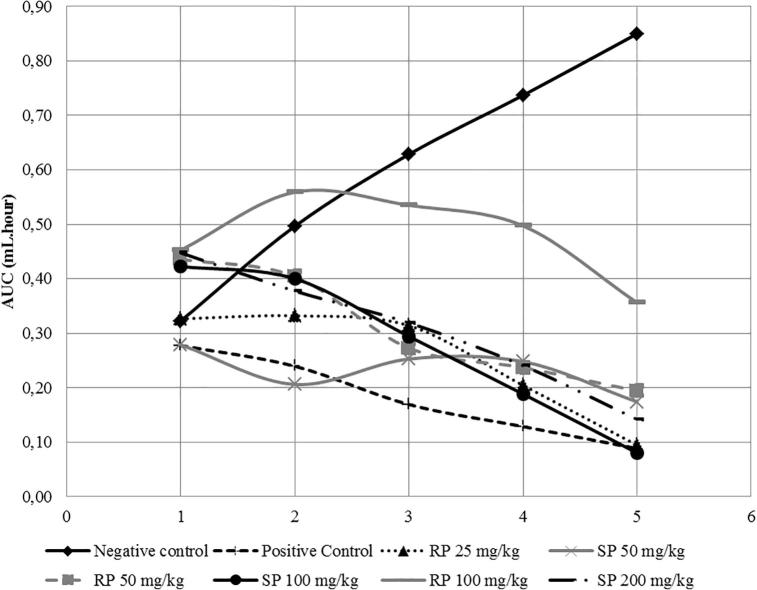

AUC value was the area under curved value between average edema volume against percentage of inflammatory inhibition (Table 3 and Fig. 6). The negative control had the highest AUC value (3.03). In contrast, SPM 50 had the lowest AUC value (0.90), followed by RPM 25 (1.27). The AUC value was inversely proportional with the inflammatory inhibition percentage capability. The negative control, which had the highest AUC value, produced the lowest inflammatory inhibition percentage, and vice versa. SPM generated a better anti-inflammatory effect than RPM due to the inflammatory inhibition value.

Table 3.

AUC value per each test groups.

| Test groups |

Area under curve (mL.Hour) |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Negative control | 0.32 | 0.5 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.85 | 3.03 |

| Positive control | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.9 |

| RPM 25 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 1.27 |

| SPM 50 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 1.16 |

| RPM 50 | 0.44 | 0.4 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 1.54 |

| SPM 100 | 0.42 | 0.4 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 1.39 |

| RPM 100 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0.36 | 2.4 |

| SPM 200 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 1.53 |

Fig. 6.

AUC graph per each test group SPM and RPM.

The highest percentage of inflammatory inhibition was obtained from SPM 50, with a value of 61.81%, followed by RPM 25, with the value of 58.12% (Table 4). Using least square method, we can calculate both SPM and RPM in the same dose; in our case we want to compare the inflammatory inhibition at dose 25 mg/kg. SPM and RPM with dose 25 mg/kg had inflammatory inhibition value of 62.24% and 58.12%, respectively.

Table 4.

Inflammatory inhibition percentage for each test group.

| Test groups | Inflammatory inhibition (%) |

|---|---|

| Positive control | 70.26 |

| SPM 25 | 62.24 |

| RPM 25 | 58.12 |

| SPM 50 | 61.81 |

| RPM 50 | 49.14 |

| SPM 100 | 54.36 |

| RPM 100 | 20.92 |

| SPM 200 | 49.71 |

These results are supported by research from Christina et al. (2018), which showed that soft propolis has a polyphenol content two and half times more than rough propolis. The polyphenol content of soft propolis was 1,106 μg/mL, whereas for rough propolis, it was 444.75 μg/mL (Christina et al., 2018). Polyphenols are phenolic compounds with more than one hydroxyl group. Polyphenols are found in many plants and have important biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbe, anti-thrombosis, and immunomodulator (Chan et al., 2013), in addition to being potent antioxidants (Nina et al., 2016). Research conducted by Pratami et al. (2018) compared the antioxidant activity of soft and rough propolis and found that soft propolis had better antioxidant activity than rough propolis, with EC50 values in DPPH assays were 25.54 and 69.96 μg/mL, respectively (Pratami et al., 2018). An abundance of free radicals can serve to identify compounds low antioxidant activity. These free radicals generate oxidative stress, which triggers inflammation. SPM demonstrated better inflammatory inhibition than RPM, likely due to its polyphenol content and increased antioxidant activity.

3.4. The relation between doses and toxicity of propolis

After 10 days when the study was concluded, there were several animal deaths in the SPM 100, SPM 200, and RPM 100 groups. These results were likely due to the toxicity of propolis and are similar to those reported for red Brazilian propolis by Da Silva et al. (2015). In that study, red Brazilian propolis at doses of 200 mg/kg and 300 mg/kg showed an indication of toxicity (da Silva et al., 2015). This toxicity was predicted by an imbalance in estrogen hormone and the high content of isoflavones, which cause inflammation.

Estrogen is a sex hormone associated with inflammatory activity (Lessey and Young, 2014). Indeed, estrogen suppresses pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α. Thus, activated estrogen hormone could bind with a transcription factor such as NF-kB and prevent it from binding DNA, which could depress inflammation (Weitzmann and Pacifici, 2006). As a result, if an imbalance in estrogen occurred, the inflammatory inhibition would be less. Propolis of Tetragronula sp from Indonesia has a high flavonoid content (Christina et al., 2018, Pratami et al., 2018), and isoflavones are one type of flavonoid. A high isoflavone content beyond a certain limit may trigger oxidative stress and lead to inflammatory reactions (da Silva et al., 2015).

3.5. Statistical analysis result

Before Kruskal–Wallis and one-way ANOVA testing were performed, homogeneity and normality tests were performed. Both data from the SPM and RPM produced a normal distribution with a sig. value of 0.367 for SPM and 0.447 for RPM. However, the data for the soft propolis microencapsulation showed a normalized distribution (sig. value of 0.41), so this test would be continued with the Kruskal–Wallis and Post-Hoc Mann–Whitney test. For the rough propolis microencapsulation, the distribution was normal, and this test was continued with one-way ANOVA and the LSD Multiple Comparisons test. The Kruskal–Wallis test produced significantly different results in the minimal two test groups. After that, the Post-Hoc Mann–Whitney test indicated that the negative control was significantly different from the other test groups, whereas the positive control was not different from the SPM 50 and RPM 100 groups. In contrast, the positive control was significantly different from the SPM 200 group. One-way ANOVA tests indicated that there were significant difference between the minimal two test groups. Subsequently, the LSD Multiple Comparisons test indicated that the negative control was significantly different from the other test groups, whereas the positive control was not different from the RPM 25 group but was different from the RPM 50 and RPM 100 groups.

4. Conclusion

The biomarkers for soft propolis that we identified in this study were [6]-dehydrogingerdione, alpha-tocopherol succinate, adhyperforin, 6-epiangustifolin, deoxypodophyllotoxin, and kurarinone, whereas those for rough propolis were [6]-dehydrogingerdione, alpha-tocopherol succinate, adhyperforin, 6-epiangustifolin, and xanthoxyletin. Both soft and rough propolis have anti-inflammatory effects. Smooth propolis exhibited higher inflammatory inhibition effect than rough propolis. This result is due to the fact that soft propolis contains more isoflavones than rough propolis. Isoflavones have antioxidant activities that reduce free radicals which cause oxidative stress and inflammation. This study suggests that propolis has the potential to develop as a non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug since our in vivo experiment showed its ability to decrease inflammation paw volume in Sprague Dawley Rat induce by carrageenan.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the funding from USAID through the SHERA program - Centre for Development of Sustainable Region (CDSR). The author also acknowledges the financial support partly funded from PTUPT Project 2018 (No: 499/UN2.R3.1/HKP05.00/2018) and the World Class Professor Program (No. 123.3/D2.3/KP/2018) from the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Alves S.F., Borges L.L., dos Santos T.O., de Paula J.R., Conceição E.C., Bara M.T.F. Microencapsulation of essential oil from fruits of Pterodon emarginatus using gum arabic and maltodextrin as wall materials: composition and stability. Drying Technol. 2014;32(1):96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bankova V. Chemical diversity of propolis and the problem of standardization. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100(1–2):114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankova V., Castro S. De, Marcucci M. Propolis: Recent advances in chemistry and plant origin. Apidologie. 2000;31(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bankova V., Popova M., Trusheva B. Propolis volatile compounds: chemical diversity and biological activity: a review. Chem. Cent. J. 2014;8(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt M.L.F., Ribeiro P.R., Franco R.L.P., Hilhorst H.W.M., de Castro R.D., Fernandez L.G. Metabolite profiling, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Brazilian propolis: Use of correlation and multivariate analyses to identify potential bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2015;76(3):449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch V.M., Pereyra-Gonzalez A., Segatin N., Santagapita P.R., Poklar Ulrih N., Buera M.P. Propolis encapsulation by spray drying: Characterization and stability. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2017;75:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Chan G.C.F., Cheung K.W., Sze D.M.Y. The immunomodulatory and anticancer properties of propolis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2013;44(3):262–273. doi: 10.1007/s12016-012-8322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christina, D., Hermansyah, H., Wijanarko, A., Rohmatin, E., Sahlan, M., Pratami, D.K., Mun’Im, A., 2018. Selection of propolis Tetragonula sp. extract solvent with flavonoids and polyphenols concentration and antioxidant activity parameters. In: AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 1933. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5023967.

- Da Silva F.C., Da Fonseca C.R., Alencar De. Assessment of production efficiency, physicochemical properties and storage stability of spray-dried propolis, a natural food additive, using gum Arabic and OSA starch-based carrier systems. Food Bioproducts Process. 2013;91(1):28–36. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva R.O., Andrade V.M., Bullé Rêgo E.S., Azevedo Dória G.A., dos Santos Lima B., da Silva F.A., Zanardo Gomes M. Acute and sub-acute oral toxicity of Brazilian red propolis in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;170:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domiati S., El-Mallah A., Ghoneim A., Bekhit A., El Razik H.A. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory, analgesic activities, and side effects of some pyrazole derivatives. Inflammopharmacology. 2016;24(4):163–172. doi: 10.1007/s10787-016-0270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit K., Buthelezi S., Bodenstein J. Anti-inflammatory and antibacterial profiles of selected compounds found in South African propolis. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2009;105(11–12):470–472. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton J.N., Gilroy D.W. Resolution of inflammation: a new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2016;15(8):551. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi-Tago M., Okamoto K., Izumi R., Tago K., Yanagisawa K., Narukawa Y., Tamura H. Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonoids in Nepalese propolis is attributed to inhibition of the IL-33 signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey C.J., Langman M.J.S. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: overall risks and management. Complementary roles for COX-2 inhibitors and proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2003;52(4):600–608. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houglum J.E., Harrelson G.L. Slack Incorporated; United State: 2011. Principles of Pharmacology for Athletic Trainers. [Google Scholar]

- Hroboňová K., Lehotay J., Čižmárik J., Sádecká J. Comparison HPLC and fluorescence spectrometry methods for determination of coumarin derivatives in propolis. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2013;36(4):486–503. [Google Scholar]

- Kivrak I., Kivrak S., Harmandar M. Development of a rapid method for the determination of antibiotic residues in honey using UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Food Sci. Technol. 2016:scielo. [Google Scholar]

- Lessey B.A., Young S.L. Homeostasis imbalance in the endometrium of women with implantation defects: The role of estrogen and progesterone. Sem. Reprod. Med. 2014;32(5):365–375. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1376355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima Cavendish R., De Souza Santos J., Belo Neto R., Oliveira Paixao A., Valeria Oliveira J., Divino De Araujo E., Zanardo Gomes M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Brazilian red propolis extract and formononetin in rodents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;173:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadewi A.G., Christina D., Hermansyah H., Wijanarko A., Farida S., Adawiyah R., Sahlan M. Selection of discrimination marker from various propolis for mapping and identify anti Candida albicans activity. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018;1933(1):20005. [Google Scholar]

- Marquiafável F.S., Nascimento A.P., Barud H. da S., Marquele-Oliveira F., De-Freitas L.A.P., Bastos J.K., Berretta A.A. Development and characterization of a novel standardized propolis dry extract obtained by factorial design with high artepillin C content. J. Pharm. Technol. Drug Res. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.7243/2050-120x-4-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nina N., Quispe C., Jiménez-Aspee F., Theoduloz C., Giménez A., Schmeda-Hirschmann G. Chemical profiling and antioxidant activity of Bolivian propolis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016;96(6):2142–2153. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulino N., Abreu S.R.L., Uto Y., Koyama D., Nagasawa H., Hori H., Bretz W.A. Anti-inflammatory effects of a bioavailable compound, Artepillin C, in Brazilian propolis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;587(1–3):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulino N., Coutinho L.A., Coutinho J.R., Vilela G.C., Pio V., Paulino A.S. Antiulcerogenic effect of Brazilian propolis formulation in mice. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2015;6:580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli A.L., Campone L., Dal Piaz F., Cuesta-Rubio O., Rastrelli L. Fragmentation pathways of polycyclic polyisoprenylated benzophenones and degradation profile of nemorosone by multiple-stage tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2009;20(9):1688–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratami D.K., Mun A., Sundowo A., Sahlan M. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of propolis ethanolic extract from tetragonula bee. Pharmacognosy J. 2018;10(1):128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rao P.S., Bajaj R.K., Mann B., Arora S., Tomar S.K. Encapsulation of antioxidant peptide enriched casein hydrolysate using maltodextrin-gum arabic blend. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016;53(10):3834–3843. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2376-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlan M., Dienayati D., Hamdi D., Zahra S., Hermansyah H., Chulasiri M. Encapsulation process of propolis extract by casein micelle improves sunscreen activity. Makara J. Technol. 2017;21(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlan M., Supardi T. Encapsulation of Indonesian propolis by casein micelle. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2013;4(1):297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Yang H., Zhang X., Sheng Y., Huang H., Yu L. Isolation and characterization of five glycerol esters from wuhan propolis and their potential anti-inflammatory properties. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2012;60(40):10041–10047. doi: 10.1021/jf302601m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soekanto S.A., Bachtiar E.W., Ramadhan A.F., Febrina R., Sahlan M. AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing; 2018. The effect of propolis honey candy on C. Albicans and clinical isolate biofilms viability (in-vitro) p. 30004. [Google Scholar]

- Troendle F.J., Reddick C.D., Yost R.A. Detection of pharmaceutical compounds in tissue by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization and laser desorption/chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry with a quadrupole ion trap. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1999;10(12):1315–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Velikova M., Bankova V., Tsvetkova I., Kujumgiev A., Marcucci M.C. Antibacterial ent-kaurene from Brazilian propolis of native stingless bees. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(6):693–696. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann M.N., Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: an inflammatory tale. J. Clin. Investig. 2006;116(5):1186–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]