Abstract

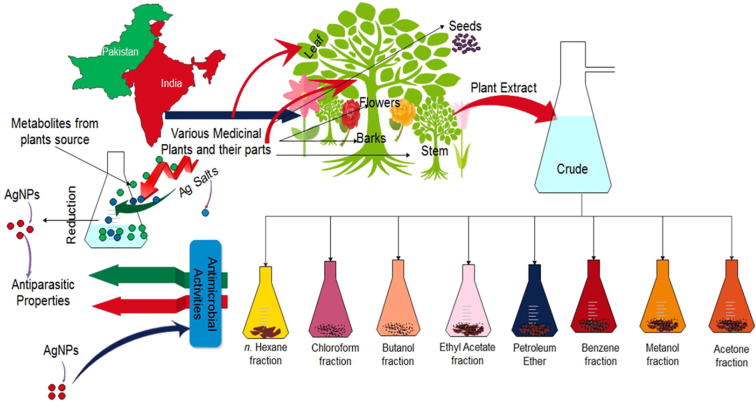

Infectious (or Communicable) diseases are not only the past but also the present problem in developing as well as developed countries. It is caused by various pathogenic microbes like fungi, bacteria, parasites and virus etc. The medicinal plants and nano-silver have been used against the pathogenic microbes. Herbal medicines are generally used for healthcare because they have low price and wealthy source of antimicrobial properties. Like medicinal plants, silver nanoparticles also have emergent applications in biomedical fields due to their immanent therapeutic performance. Here, we also explore the various plant parts such as bark, stem, leaf, fruit and seed against Gram negative and Gram-positive bacteria, using different solvents for extraction i.e. methanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, acetone, n. hexane, butanol, petroleum ether and benzene. Since ancient to date most of the countries have been used herbal medicines, but in Asia, some medicinal plants are commonly used in rural and backward areas as a treatment for infectious diseases. In this review, we provide simple information about medicinal plants and Silver nanoparticles with their potentialities such as antiviral, bactericidal and fungicidal. Additionally, the present review to highlights the versatile applications of medicinal plants against honey bee pathogen such as fungi (Ascosphaera apis), mites (Varroa spp. and Tropilaelaps sp.), bacteria (Melissococcus plutonius Paenibacillus larvae), and microsporidia (Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae). In conclusion, promising nonchemical (plant extracts) are innocuous to adult bees. So, we strongly believed that this effort was made to evaluate the status of medicinal plants researches globally.

Keywords: Medicinal plants, Bactericidal, Fungicidal and Honey bee Pathogen

1. Introduction

Today infectious (or Communicable) diseases are the most important global problem (Nair et al., 2017), and it has the prime source of the death (Vu et al., 2015), and almost 50,000 people’s deaths per day (Namita and Mukesh, 2012). Infectious diseases due to various pathogenic bacterial strains namely, Staphylococcus aureus (Nathwani et al., 2016), E. coli (Wang et al., 2016) Klebsiella pneumonia (Sidjabat et al., 2011), bloodstream associated Staphylococcus epidermidis (Hijazi et al., 2016) Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, Vibrio cholera are the most common pathogenic bacteria (Namita and Mukesh, 2012).

According to World health organization (WHO), more than 80% of the humanity inhabitants depend on heritage medicine for their most important health care needs (Nair and Chanda, 2005). The total reported plants species in the world is about 258,650. Among these, more than 10% are used for therapeutic purposes. North-West of Pakistan is granted with a variety of therapeutic plants assets because of diverse geographical and habitat conditions. The medicinal utilization of plants for healing a variety of remedies is a vital part of the region’s cultural heritage (Shinwari, 2010).

The area of Pakistan has 80,943 km2, lies between 60° 55′ to 75° 30′ E longitude and 23° 45′ to 36° 50′ N latitude. Pakistan has a rich flora, about 6000 species of higher plants. It has been reported that 600 to 700 species having good potential for therapeutic uses.

More recently it was reported that plant metabolites are an excellent source to control and reduce microbes (Samoilova et al., 2014, Ribeiro et al., 2018). Medicinal plants have good potential against microorganism, which can be used as an alternate source of antibiotics (Ameya et al., 2017, Girish and Satish, 2008, Shinwari, 2010, Malik et al., 2011, Walter et al., 2011, Rahimet al., 2015).

The medicinal plants are used in India, China and the north east as a source of relief from sickness. The Compound of natural as well as an artificial source has been the base of numerous therapeutic agents (Mahesh and Satish, 2008). India has wealthy tradition background on plant-based drugs both for use in precautionary and medicinal medication. India has rich flora for the improvement of drugs from a medicinal plant. Because of the potential of the Medicinal plants to cure various diseases now the plants are used as novel antimicrobial substances. Considering the vast potentiality of the plant as sources for antimicrobial drugs the present study is based on the review of such plants (Saranraj and Sivasakthi, 2014).

Moreover, the present review to highlights the versatile applications of medicinal plants, as the whole plant, selected parts, or in extract form, such as antiviral, antibacterial, fungicidal, antiparasitic and miticides against bee mites (Varroa destructor). Hence, the advancement of unconventional control approaches is likely and needs to be considered. Besides, that a novel approach to plants extracts application is to mitigate the honey bee pathogen like Bacteria (Paenibacillus larva), Mite (Varroa destructor), Fungi (Ascosphaera apis) had also been reported.

The most important field to generate the nanomaterials for biomedical purposes and other fields (agriculture, electronic, food and power etc) is termed as Nanotechnology (Ahluwalia et al., 2018, Gurunathan et al., 2014). Outbreak of the various infectious diseases, the researchers and pharmaceuticals companies are searching for the developed new type of antibiotic against these pathogens. The present period, nanoparticles have emerged due to unique physical and chemical properties, high surface to volume ratio as novel antimicrobial agents (Rai and Ingle, 2012, Duran and Marcato, 2013, Butler et al., 2015). Among the different type of nanoparticles, particularly, the silver nanoparticles has observed for its biomedical applications in the treatment of bactericidal (Tanvir et al., 2017, Manikandanet al., 2015), fungicidal (Sre et al., 2015) antiviral (Villeret et al., 2018, Malachováet al., 2011) and anti-protozoals (Fayaz et al., 2012).

Silver nanoparticles have been renowned practical applications against antibacterial properties. Furthermore, in recent years the Nanosilver potentialities have been evaluated against the different pathogens such as arthropods vectors infections, various types of cancer cells, but still, now there are many questions which are not yet solved, but in future, the scientists have been attention to solve in further research. Importantly, silver nanoparticles being measured for use as an alternative control in bee hives requires significant inhibitory activity against the bee disease without nontoxic effect on adult honeybees.

2. Antibacterial potential of medicinal plants

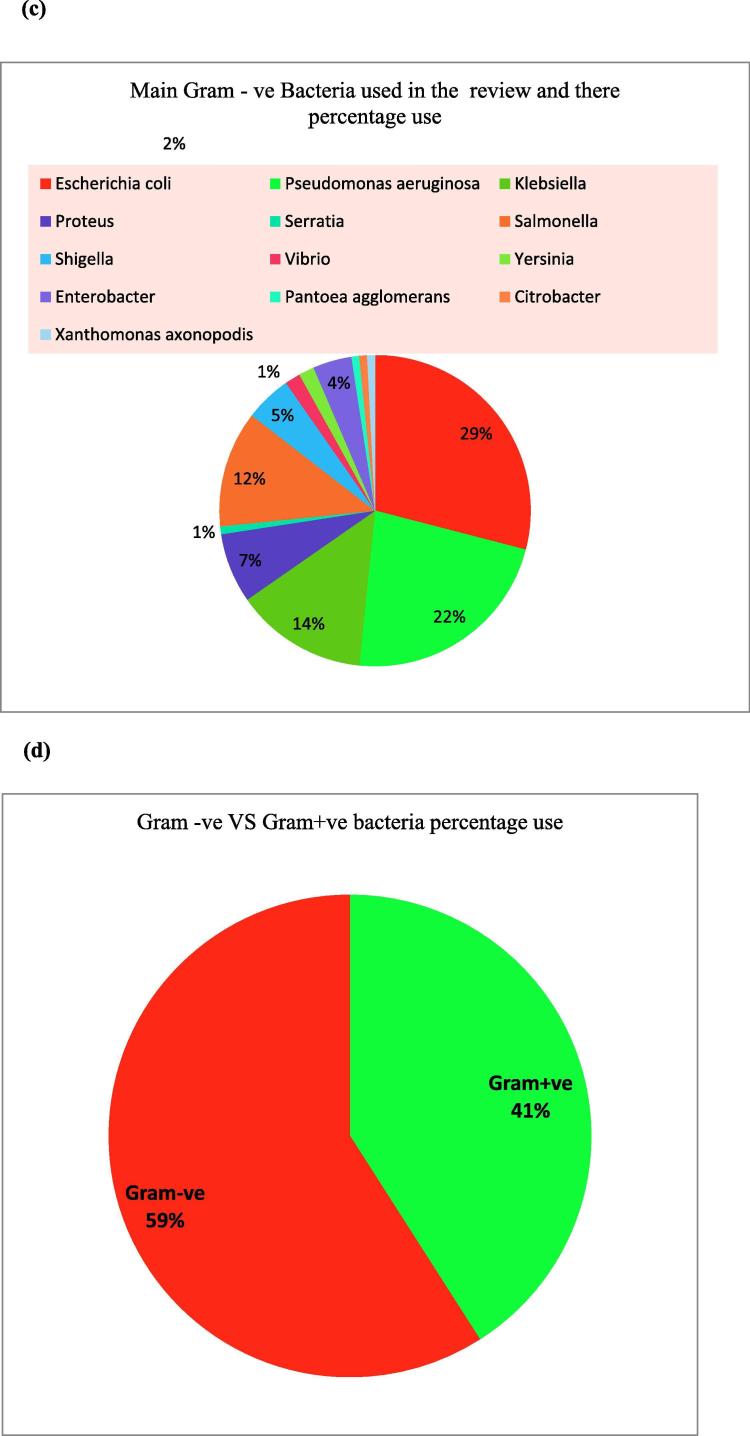

In this portion, we present medicinal plants and their different fractions, different parts (various methods and different micro-organisms) (Table 1, Table 2) and both Gram-negative and positive strains of bacteria (Table 1) and their percentage use is shown in (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) respectively. Furthermore, this review demonstrates the silver nanoparticles potentialities against microbes and parasites which are listed in Table 3.

Table 1.

Microorganism, methods and solvents described in the text.

| Gram positive Bacteria | Bacillus cereus, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus, Micrococcus, Listeria, Streptococcus, Cocci, Lactobacillus and Enterococcus fecalis) |

| Gram negative Bacteria | Enterobacter, Escherichia coli, Pantoeaagglomerans Proteus, Shigella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia, Vibrio, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Yersinia and Citrobacte. |

| Fungal species | Trichophytonmentagrophytes, Candidakrusei, Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candidakrusei, Aspergillus, A. flavus, A. niger, Curvularia sp., Fusarium sp., Rhizopussp and Candidaparapsilosis |

| Viruses | Monkeypoxvirus, respiratorysyncytial virus, HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex virus type 1, Vaccinia virus, human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV-3), Herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), tacaribe virus (TCRV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), Coxsackie virus B3 and influenza virus |

| Method Used | Agar well diffusion, Agar disk diffusion, Agar ditch diffusion, Tube diffusion, Bauer disc diffusion, Broth dilution, Micro dilution, Liquid dilution and Serial dilution |

| Solvent Used | Methanol, n-Hexane, Aqueous, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate, Benzene, Petroleum Ether, Acetone, Ethanolic, Dichloromethane, Dimethyl Sulphoxide and Diethyl Ether |

Table 2.

Various medicinal plants and their important parts used in the text against as antimicrobial properties.

| Sr. no. | Plant Name | Part Used | Essential oil | Whole plant | Stem | Root/Rhizome | Seed | Flower | Fruit | Bark | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | |||||||||||

| 1 | Ajugabracteosa | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Girish and Satish (2008) |

| 2 | Calotropisprocera | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Girish and Satish (2008) |

| 3 | Zizyphus sativa | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Girish and Satish (2008) |

| 4 | Sapindusemarginatus | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 5 | Hibiscus rosasinensis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 6 | Mirabilis jalapa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) | |

| 7 | Rhoeo discolor | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 8 | Nyctanthes arbor-tristis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 9 | Colocasiaesculenta | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) | |

| 10 | Gracilariacorticata | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 11 | Dictyotasp | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 12 | Pulicariawightiana | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nair et al. (2005) |

| 13 | Anisomelesindica | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ramasamy and Manoharan (2004) |

| 14 | Blumealacera | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ramasamy and Manoharan (2004) |

| 15 | Meliaazadirachta | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ramasamy and Manoharan (2004) |

| 16 | Phyllanthusamarus | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Aliero and Afolayan (2006) |

| 17 | Galinsoga ciliate | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Poonkothai et al. (2005) |

| 18 | Hippophaerhamnoides | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | – | Mohammad et al. (2007) |

| 19 | Parkiajavanica | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Saha et al. (2007) |

| 20 | Hemidesmusindicus (L.) | – | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 21 | Eclipta alba | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 22 | Cosciniumfenestratum | – | – | – | Stems | – | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 23 | Cucurbitapepo L | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 24 | Tephrosiapurpurea | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 25 | Menthapiperita | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 26 | Pongamiapinnata | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 27 | Symplocosracemosa | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 28 | Euphorbia hirta | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 29 | Tinosporacordyfolia | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 30 | Thespesiapopulnea | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 31 | Jasminumofficinale | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Kumar et al. (2007) |

| 32 | Marrubiumvulgare | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Warda et al. (2009) |

| 33 | Thymus pallidus | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Warda et al. (2009) |

| 34 | Eryngiumilicifolium | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Warda et al. (2009) |

| 35 | Lavandulastoechas. | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Warda et al. (2009) |

| 36 | Mimosa pudica, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Balakrishnan et al. (2006) |

| 37 | Angle marmelos | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruits | – | Balakrishnan et al. (2006) |

| 38 | Sidacordifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Balakrishnan et al. (2006) |

| 39 | Acalyphaindica | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Ushimaru et al. (2007) |

| 40 | Mollugolatoides | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ushimaru et al. (2007) |

| 41 | Nelumbonucifera | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Ushimaru et al. (2007) |

| 42 | Garciniamangostana | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruits | – | Saranraj, 2011a, Saranraj, 2011b) |

| 43 | Puciniagranatum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Saranraj, 2011a, Saranraj, 2011b) |

| 44 | Quercusinfectoria | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Saranraj, 2011a, Saranraj, 2011b) |

| 45 | Daturametel | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Saranraj, 2011a, Saranraj, 2011b) |

| 46 | Phyla nodiflora | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ullah et al. (2013) |

| 47 | Zingiberofficinale | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Norajit et al. (2007) |

| 48 | Alpiniagalanga | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Norajit et al. (2007) |

| 49 | Curcuma longa | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Norajit et al. (2007) |

| 50 | Boesenbergiapandurata | – | Essential oil | – | – | - | - | - | - | - | Norajit et al. (2007) |

| 51 | Amomumxanthioides | – | Essential oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Norajit et al. (2007) |

| 52 | Pterocarpusangolensis | – | – | – | Stem | – | – | – | – | – | Samie et al. (2009) |

| 53 | Lippiajavanica | – | Essential Oil | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Samie et al. (2009) |

| 54 | Zingiberofficinale | – | – | Whole plants | – | – | – | – | – | – | Al-Daihan et al. (2013) |

| 55 | Curcuma longa, | – | – | Whole plants | – | – | – | – | – | – | Al-Daihan et al. (2013) |

| 56 | Commiphoramolmol | – | – | Whole plants | – | – | – | – | – | – | Al-Daihan et al. (2013) |

| 57 | Pimpinellaanisum | – | – | Whole plants | – | – | – | – | – | – | Al-Daihan et al. (2013) |

| 58 | Elaeagnusangustifolia | Leaves | – | – | Stem | Root | – | – | – | – | Khan et al. (2013) |

| 59 | Elaeagnusangustifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Okmen et al. (2013) |

| 60 | Elaeagnusangustifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Farzaei et al. (2015) |

| 61 | Stephaniaglabra | – | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Semwal et al. (2009) |

| 62 | Woodfordiafruticosa | – | – | – | Stem | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Chougale et al. (2009) |

| 63 | Betulautilis | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Kumaraswamy et al. (2008) |

| 64 | Bidenspilosa | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 65 | Bixaorellana | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 66 | Cecropiapeltata | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 67 | Cinchona officinalis | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 68 | Gliricidiasepium | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 69 | Jacarandamimosifolia | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 70 | Justiciasecunda | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 71 | Piper pulchrum | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 72 | P. paniculata | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 73 | Spilanthes Americana | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Patel et al. (2007) |

| 74 | Azadirachtaindica | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | – | El-Mahmood et al. (2010) |

| 75 | Albizialebbeck (L.) | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 76 | Cleistanthuscollinus (Roxb.) | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 77 | Emblicaofficinalis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 78 | (Phyllanthusemblica L.) | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 79 | Eucalyptus deglupta | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 80 | (Eucalyptus tereticornis) | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 81 | Eupatorium odoratum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 82 | Oxalis corniculata L. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 83 | Heveabrasiliensis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 84 | Lantana camara | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Maity et al. (2010) |

| 85 | Acacia nilotica | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | Bark | Mahesh and Satish (2008) |

| 86 | Sidacordifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | Bark | Mahesh and Satish (2008) |

| 87 | Tinosporacordifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | Bark | Mahesh and Satish (2008) |

| 88 | Withaniasomnifer | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | Bark | Mahesh and Satish (2008) |

| 89 | Ziziphusmauritiana | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | Bark | Mahesh and Satish (2008) |

| 90 | Lantana indica | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Venkataswamy et al. (2010) |

| 91 | Arnebianobilis | – | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 92 | Garciniaindica | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 93 | Boerhaviadiffusa | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 94 | Solanumalbicaule | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 95 | Vitexnegundu | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 96 | Buniumpersicum | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 97 | Acacia concinna | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 98 | Albizialebbeck | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Menghani et al. (2011) |

| 99 | Syzygiumaromaticum Linn. | – | – | – | Stem, | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 100 | Piper betle Linn. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 101 | Curcuma longa Linn. | – | – | – | – | Rhizhome | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 102 | Punicagranatum Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 103 | Garciniamangostana Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit Peel | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 104 | Andrographispaniculata | Leaves | – | – | Stem | – | – | Flower | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) | |

| 105 | Sennaalata (Linn.) | – | – | – | – | – | Seed | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 106 | Boesenbergiapandurata | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) | |

| 107 | Cassia angustifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 108 | Cinnamomumzeylanicum | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 109 | Caesalpiniasappan Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 110 | Curcuma xanthorrhiza | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 111 | Syzygiumaromaticum Linn. | – | – | – | Stem | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 112 | Piper betle Linn. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 113 | Curcuma longa Linn. | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 114 | Punicagranatum Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit Peel, | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 115 | Garciniamangostana Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit Peel | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 116 | Andrographispaniculata | Leaves | – | – | Stem, | – | – | Flower | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) | |

| 117 | Sennaalata (Linn.) | – | – | – | – | – | Seed | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 118 | Boesenbergiapandurata | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 119 | Cassia angustifolia | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 120 | Cinnamomumzeylanicum | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 121 | Caesalpiniasappan Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 122 | Curcuma xanthorrhiza | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 123 | Carthamustinctorius Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 124 | Derris scandens | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 125 | Cyperusrotundus Linn. | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 126 | Acanthus ebracteatus | Leaves | – | – | Stem, | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 127 | Tinosporacrispa(L.) | – | – | – | Stem | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 128 | Eclipta prostate | Leaves | – | – | Stem, | – | – | Flower | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 129 | Phyllanthusemblica Linn. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 130 | AzadirachtaindicaA. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 131 | Morindacitrifolia, | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 132 | Sennasiamea | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 133 | Morus alba Linn. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 134 | Citrus aurantifolia | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 135 | Piper retrofractum | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong (2009) |

| 136 | Aloe Vera | – | – | – | Stem | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 137 | Azadirachtaindica | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 138 | Allium sativum | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 139 | Calotropisprocera | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 140 | Cannabis sativa | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 141 | Carumcapticum | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) | |

| 142 | Eucalyptus camaldulensi | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 143 | Lantana camara, | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 144 | Mangiferaindica, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 145 | Menthapiperita, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 146 | Nigella sativa, | – | – | – | – | – | Seed | Flower | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 147 | Opuntia | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 148 | Ficusindica, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 149 | Piper nigrum. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | Yasmeen et al. (2012) | |

| 150 | Zingiberofficinalis | – | – | – | – | Rhizhome | – | – | – | – | Yasmeen et al. (2012) |

| 151 | Achyranthesbidentata | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 152 | Belamcandachinensis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 153 | Chelidoniummajus | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 154 | Houttuyniacordata. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 155 | Platycodongrandiflorum | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 156 | Rehmaniaglutinosa | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 157 | Sanguisorbaofficinalis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 158 | Schizandrachinensis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 159 | Tribulusterrestris | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 160 | Tussilagofarfara | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Janovska et al. (2003) |

| 161 | Achilleamillifolium, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 162 | Caryophyllusaromaticus, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 163 | Melissa offficinalis, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 164 | Ocimunbasilucum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 165 | Psidiumguajava | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 166 | Punicagranatum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 167 | Rosmarinusofficinalis, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 168 | Salviofficinalis, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 169 | Syzygyumjoabolanum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 170 | Thymus vulgaris | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Nascimento et al. (2000) |

| 171 | Albizialebbeck | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 172 | Terminaliachebula | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 173 | Syzygiumcumini | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 174 | Solanumnigrum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 175 | Picrorhizakurrooa | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 176 | Buteamonosperma | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 177 | Saracaindica | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | Flowers | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 178 | Aeglemarmelos | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | Acharyya et al. (2009) | ||

| 179 | Withaniasomnifera | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Acharyya et al. (2009) |

| 180 | TamarixGallica, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 181 | MuscariComosun, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 182 | Rhetinolepissp, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 183 | Taraxacumofficinnale, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 184 | Zygohyllum album, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 185 | Uricadioica | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 186 | Silybummarianum, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 187 | Traganumnudatun, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 188 | Rhamnussp | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zaouia et al. (2010) |

| 189 | Sedum kamtschaticum | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) |

| 190 | Geumjaponicum, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) | |

| 191 | Geranium sibiricum, | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) | |

| 192 | Saururuschinensis, | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) |

| 193 | Agrimoniapilosa, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) |

| 194 | Houttuyniacordata, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) |

| 195 | Perillafrutescens | – | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) |

| 196 | Agastacherugosa | Leaves | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Kang et al. (2011) |

| 197 | Pereskiableo, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) | |

| 198 | Pereskiagrandifolia, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) | |

| 200 | Curcuma zedoria, | – | – | – | – | Rhizhome | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) |

| 201 | Curcuma mangga, | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) |

| 202 | Curcuma inodora | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) |

| 203 | Zingiberofficinale var. officinale | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) |

| 204 | Zingiberofficinale var. rubrum | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) |

| 205 | Curcuma aeruginosa | – | – | – | – | Rhizome | – | – | – | – | Philip et al. (2009) |

| 206 | Hypericumscabrum, | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 207 | Myrtuscommunis, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 208 | Pistachiaatlantica, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 209 | Arnebiaeuchroma, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 210 | Salvia hydrangea, | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 211 | Saturejabachtiarica, | – | – | – | – | Roots | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 212 | Thymus daenensis | – | Essential oils | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) | |

| 213 | Kelussiaodoratissima | – | Essential oils | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Ghasemi et al. (2010) |

| 214 | Aloe vera, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 215 | Phyllanthusemblica, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 216 | Phyllanthusniruri, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 217 | Cynodondactylon, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 218 | Murryakoenigii, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 219 | Lawsoniainermis, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 220 | Adhathodavasica | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Selvamohan et al. (2012) |

| 221 | Terminaliachebula, | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Prabhat and Navneet (2010) |

| 222 | Mimusopselengi, | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Prabhat and Navneet (2010) |

| 223 | Achyranthesaspera, | – | – | Whole plant | – | – | – | – | – | – | Prabhat and Navneet (2010) |

| 224 | Acacia catechu, | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Prabhat and Navneet (2010) |

| 225 | A. arabica | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Bark | Prabhat and Navneet (2010) |

| 226 | Glycyrrhizaglabra extracts | – | – | – | – | Root | – | – | – | – | Prabhat and Navneet (2010) |

| 227 | Acacia Arabica, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | Hassan et al. (2009) | ||||

| 228 | Nymphaea lotus, | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Hassan et al. (2009) |

| 229 | Sphaeranthshirtus, | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | Hassan et al. (2009) | |

| 230 | Emblicaofficinalis, | – | – | – | – | – | – | Fruit | – | Hassan et al. (2009) | |

| 231 | Cinchoriumintybus | – | – | – | – | – | – | Flower | – | – | Hassan et al. (2009) |

| 232 | Silybummarianum | – | – | – | – | – | Seeds | – | – | – | Hassan et al. (2009) |

| 233 | Ocimum sanctum | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zwetlana et al. (2014) |

| 234 | Citrus limon | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zwetlana et al. (2014) |

| 235 | Nerium oleander | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zwetlana et al. (2014) |

| 236 | Azadirachtaindica | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zwetlana et al. (2014) |

| 237 | Hibiscus rosasinensis | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zwetlana et al. (2014) |

| 238 | Eucalyptus globules | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Zwetlana et al. (2014) |

| 239 | Aloe vera, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Johnson et al. (2011) |

| 240 | Daturastromonium, | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Johnson et al. (2011) |

| 241 | Pongamiapinnata | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Johnson et al. (2011) |

| 242 | Lantonacamara. | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Johnson et al. (2011) |

| 243 | Calotropisprocera | Leaves | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Johnson et al. (2011) |

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of various medicinal plants, their different parts used for Antimicrobial activities along with biogenic silver synthesis and its biological potential.

Fig. 2.

(a) Number of various plant parts used in the review, showing antibacterial potential. (b) Percentage use of Gram-positive Bacteria. (c) Percentage use of Gram-negative Bacteria. (d) The Gram positive VS Gram negative% use in the text.

Table 3.

Plants synthesized nano-silver and their biological properties.

| Plant name | Plant portion used | Size of silver nano particles | Reported properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia leucophloea | Bark | 17–29 nm | Bactericidal | Murugan et al. (2014) |

| Aeglemarmelos | Fruit | 34.7 nm | Bactericiadal & Antibiofilm | Nithya Deva Krupa and Raghavan (2014) |

| Alpiniagalanga | Rhizome | 20.82 nm | Antifungal and Antibacterial | Joseph and Mathew (2014) |

| Artemisia princeps | Leaf | 10–40 nm | Antibacterial and anticancer | Gurunathan et al. (2015) |

| Psidiumguajava | Leaves and fruits | 26 and 60 nm | Antibacterial and antifungal | Raghunandan et al. (2011), Gupta et al. (2014) |

| Nyctanthesarbortristis | Flowers | 5–20 nm | Antibacterial and cytotoxicity | Gogoi et al. (2015) |

| Myristicafragrans | Essential oils | 12–26 nm | Bactericidal | Vilas et al. (2014) |

| Moringaoleifera | Seed and leaf | 100 nm | Larvicidal and antibacterial | Mubayi et al. (2012), Sujitha et al. (2015) |

| Lantana camara | Leaf | 11–24 nm | Antibacterial | Ajitha et al. (2015) |

| Ficusmicrocarpa | Leaf | ND | Antibacterial | Praba et al. (2015) |

| Euphorbia hirta | Latex and leaf | 30–60 and 263.11 nm | Antibacterial, larvicidal and pupicidal | Patil et al. (2012), Priyadarshini et al. (2012) |

| Dalbergiaspinose | Leaves | 18 nm | Bactericidal, antioxidant and anti–inflammatory | Muniyappan and Nagarajan (2014) |

| Citrus limon | >100 nm | Antifungal | Vankar and Shukla (2012) | |

| Chenopodiummurale | Leaf | 30–50 | Antibacterial | Abdel-Aziz et al. (2014) |

| Caesalpiniacoriaria | Leaf | 40–98 nm | Antibacterial | Jeeva et al. (2014) |

| Andrographispaniculata | Leaves | 55 nm | Antiprotozoal | Panneerselvam et al. (2011) |

| Catharanthusroseus | Leaves | 35–55 | Anitprotozoal | Ponarulselvam et al. (2012) |

Note: ND; Not detected.

Girish and Satish (2008), studied three plants mainly the leaves portion had been utilized as shown in Table 2. Two Gram-positive (Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis) and three Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhi) bacterial strains, by using agar well diffusion method. The result indicated that methanol fraction shows a potent result against the entire tested organisms, apart from Zizyphus sativa plant inactive against Salmonella typhi and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The n-Hexane extracts showed the promising action against both strains, while the Zizyphus sativa fraction of n-Hexane also has no performance against Bacillus cereus and Salmonella typhi (Girish and Satish, 2008).

Nair and his company (2005) evaluated nine plants. Antibacterial activity was tested against 6 bacterial strains, Pseudomonas testosteroni, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Bacillus subtilis, Proteus morganii and Micrococcus flavususing Agar disk and agar ditch diffusion method. The result showed that Pseudomonas testosterone and Klebsiella pneumonia were the great resistant strains, while the Sapindusem arginatus has greater bactericidal potential against all the tested strains (Nair et al., 2005).

In another study, three plants were used. The result indicated that acetone and methanol fractions of all the tested plants display stout antibacterial effect, while the petroleum ether and aqueous did not show any result. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcesenes were comparatively more sensitive (Ramasamy and Manoharan, 2004). Aliero and Afolayan (2006) screened a single plant using Bauer disc diffusion method. The results showed that, strains isolated from both HIV sero-positive patients were susceptible to different concentrations of the fraction (5 mg/mL, 10 mg/mL, 20 mg mL−1, 40 mg/mL and 80 mg/mL) (Aliero and Afolayan, 2006).

Poonkothai and his colleagues demonstrated leaves of a single plant against both strains of bacteria using Agar well diffusion method. The results showed instead of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, all the fractions i.e. acetone, petroleum ether and benzyl ethyl acetate of the leaves of Galinisoga ciliate have strong property against Bacillus subtilis (Poonkothai et al., 2005). The bactericidal potential of Parrotia persican leaves was tested against Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia enterocolitica, the MIC values were found to be 750 ppm and 1000 pmm respectively (Mohammad et al., 2007). Furthermore, the author and his friends tested the parkiajavanica medicinal plant bark against three different bacterial strains. The result demonstrated that excluding Escherichia coli all the tested bacteria showed the strong result (Saha et al., 2007).

Recently, Kumar et al. examined 12 medicinal plants. The disc diffusion method result showed that among the 12 plants the 07 medicinal plants could forbid the growth of Propioni bacterium acnes. Amid that Hemidesmus indicus, Coscinium fenestratum, Tephrosia purpurea, Euphorbia hirta, Symplocosracemosa, Curcubito pepo and Eclipta albahad strong inhibitory effects. Based on a broth dilution method, the Coscinium fenestratum extract had the supreme antibacterial effect. The same MIC values i.e. (0.049 mg/ml) for both bacterial species and the MBC values were 0.049 and 0.165 mg/ml against Propioni bacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis (Kumar et al., 2007).

In recent study four (04) medicinal plants were used, the result was to be found that, the methanol extract of Marrubium vulgare, Thymus pallidus and Lavandula stoechas shows significant result against bacterial strains (Warda et al., 2009). Sidacoxdifolia Minosapudica and Aegle marmelos medicinal plants were used against bacterial strains. The result indicated that highest zone of inhibition Sida coxdifolia against Bacillus subtilis (35 mm) and Salmonella typhi (26 mm), while the rest plants also show activity against tested organisms (Balakrishnan et al., 2006).

Ushimaru and his company (2009) tested three (03) plants against bacterial strains. The results demonstrated that the aqueous fraction of Mollungo latoides and Acalypha indica were displayed potent activity against Escherichia coli at various concentrations, Nelumbo nucifera alcoholic extract was to be found 0.390 mg/mL against Klebsiella pneumonia (Ushimaru et al., 2007).

Moreover, three plants and their various parts were used; all the plants displayed the great potential against the tested bacteria. The MICs and MBCs were to be observed for Staphylococcus aureus of 0.1, 0.2 and 0.1 mg/mL, 0.4–1.6 mg/mL and 0.4, 3.2 and 1.6 mg/mL respectively (Saranraj, 2011a, Saranraj, 2011b). The author examined the phytochemicals and bacterial activity of Datura metel leaf, using Ager well diffusion method. The author reported that ethanol fraction of the plant had the highest zone of inhibition (26 mm) against Bacillus subtilis, and Escherichia coli, while the Staphylococcus aureus has the lowest zone of inhibition (8 mm). The ethyl acetate fraction display strong zone of inhibition against E. coli, but no effect against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Saranraj, 2011a, Saranraj, 2011b).

The author and his co-authors used phyla nodiflora plant against bacteria. The author and his coworker concluded that n-hexane and n-butanol fractions were observed to be positive against E. coli and P. Aeruginosa, while the chloroform, n-butanol, ethyl acetate and n-hexane fractions show potential action against Salmonella and MRSA except for the crude fraction (Ullah et al., 2013).

Norajit and his coworkers screened the essential oil of five plants used by disc diffusion method. The outcomes of the essential oils obtained from Boesenbergia pandurata and Amomum xanthioides stop the growth of all tested bacteria, while the essential oil of Zingiber officinale had the highest potential against three positive strains of bacteria (S. aureus, B. cereus and L. monocytogenes). It was to be found that the minimum concentration of inhibition to be 6.25 mg/ml against B. cereus and L. monocytogenes (Norajit et al., 2007).

In another study, two plants were used. The results indicated that the acetone extract had displayed significant property against all strains. 0.0156 mg/mL against Staphylococcus aureus, while 2 mg/mL against Enterobacter cloacae. The essential oil obtained from Lippia javanica was also found to be reasonable result against Entamoeba histolytica. The inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 25 and 100 mg/mL, respectively (Samie et al., 2009).

Al-Daihan et al. phytochemically screened four different medicinal plants used against different bacterial strains. The result shows that methanol extract of C. molmol and C. longa against S. pyogenes and S. aureus displayed maximum activity (19 mm), while the minimum activity of aqueous fraction against P. anisum against E. coli and P. aeruginosa (7 mm) (Al-Daihan et al., 2013). Khan and his company examined Elaeagnus angustifolia plant against different bacteria. The various parts of the plant were used i.e. leaves, branches, stem bark, root and root bark. The author reported that methanolic crude extract, n-hexane, and ethyl acetate showed bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, while n-hexane and ethyl acetate also showed an antibacterial effect against Pseudomonasa eruginosa (Khan et al., 2013).

The Elaeagnus angustifolia leaves were also used for bactericidal and antioxidant potential. The result was to be found that, methanolic fraction inhibit the growth of Yersinia enterocolitica, while the MIC range against clinical strain coagulate negative Staphylococci was to be 3250–6500 μg/mL (Okmen and Turkcan, 2013b, Okmen and Turkcan, 2013a). Furthermore, the soft extract of the Elaeagnus angustifolia was used. The author summarized that all samples showed the potent activity against the bacteria (Farzaei et al., 2015). Semwal and his coworkers (2009) demonstrated the rhizome of the plant species against antimicrobial property. Three extracts were used, the result summarized that among this only ethanolic fraction had strong activity against the tested microorganisms. Using novobiocin (15 μg/mL) as standard to check the zone of inhibition, the minimum inhibition concentration was to be found 50 μg/mL against S. mutants and S. epidermidis (Semwal et al., 2009).

Woodfordia fruticosekurz medicinal plant was used to check the antibacterial potential. The results summarized that the various amount of acetone (80 μg and 120 μg) were shows promising activity against all the tested bacteria. It was further tested against standard antibiotic erythromycin) (Chougale et al., 2009). In another study, Betulautilis was used for antibacterial and phytochemical analysis using Agar well diffusion method. And they used 15 microorganisms namely, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella paratyphi, Salmonella typhi, Salmonella typhimurium, Shigellaflexneri, Shigellasonnei, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus faecalis, Shigella boydii, Citrobacter spp., Salmonella paratyphi B and Shigella boydii. The result indicated that methanol, ethanol and aqueous extracts were to be found significant activity against all the tested bacteria, while petroleum and chloroform extract inactive (Kumaraswamy et al., 2008).

Patel and his company screened (2007) medicinal plants against antimicrobial potential. The result demonstrated that aqueous fractions of Bidenspilosa, Jacaranda mimosifolia, and Piper pulchrum shows significant action against Bacillus cereus and Escherichia coli thanantibioticgentamycin sulfate. While the ethanol fractionof all samples was active against Staphylococcus aureus except for Justicia secunda. Furthermore, Bixa orellana, Justicia secunda and Piper pulchrum showed minimum MICs against Escherichia coli (0.8, 0.6 and 0.6 μg/mL, respectively) compared to gentamycin sulfate (0.98 g/mL). Bixa orellana was found to be strong MIC against Bacillus cereus (0.2 μg/mL) than gentamycin sulfate (0.5 μg/mL) (Patel et al., 2007).

Seeds of the Azadarichta indica were used against pathogenic bacteria. The results showed that both strains growth were inhibited, it is also found that gram positive more susceptible as compared to gram negative bacteria. The control laboratory strains were reported as more sensitive to the toxic effects of the crude extracts than the corresponding test bacteria. Hexane extracts were reported as more effective, producing larger zones of growth inhibition sizes and smaller MIC and MBC values, than the aqueous extracts. The MIC values ranged from 1.59 to 25 mg/mL while the MBC values ranged from 3.17 to 50 mg/mL (El-Mahmood et al., 2010).

Recently, Maity et al. (2010) evaluated the antimicrobial activity of the leaves of eight plants species. The various fractions of Albizia lebbeck, Cleistanthus collinus, Emblica officinalis, Eucalyptus deglupta, Eupatorium odoratum, Oxaliscorniculata and Hevea brasiliensis were showed the healthier zone of inhibition (>11 mm) against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Vibriocholerae and Candida albicans. The zone of inhibition of 11–13 mm was reported by Lantanacamara against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Vibrio choleraeand Candida albicans. The extract of Butea frondosais, Melastoma malabathricum, Terminalia Arjuna, and Lycopodium japonicum were reported to show reasonable activity (8–11 mm) against all the tested bacteria. The plants like Adina cordifolia, Asparagus racemosus, Aegle marmelos, Cassia tora, Dillenia pentagyna, Valeriana wallichii were found to be a poor activity (5–8 mm) against all the tested bacteria. Ocimum basilicum were found to reasonable activity (05–08 mm). The MIC values of plant extracts were found to exhibit significant at 0.35–0.80 mg/mL. Among the tested plants, Albizia lebbeck, Cleistanthus collinus, Emblica officinalis, Eucalyptus deglupta, Eupatorium odoratum, Oxalis corniculata and Hevea brasiliensis were reported to show the minimum MIC values of 0.35–0.60 mg/mL. For the acetonic fraction of Emblica officinalis, Eucalyptus deglupta, Oxalis corniculata and Hevea brasiliensis greatest activity were reported (Maity et al., 2010).

Mahesh and Satish (2008) tested the biological property of five plants. The results showed that, the methanolic leaf extract of Acacia nilotica, Sida cordifolia, Tinospora cordifolia, Withania somnifer and Ziziphus mauritiana strong action against Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Staphylococcus aureus and Xanthomonas axonopodis. Malvacearum. While the maximum antibacterial activity was found for A. nilotica and S. cordifolia leaf extract against B. subtilis. And Z. mauritiana leaf extract against Xanthomonas axonopodis, Malvacearum. For root and leaf extract of S. cordifoliasignificant activity was recorded against all the test bacteria (Mahesh and Satish, 2008).

Venkataswamy et al. (2010) screened the leaves of the single plant. The results were found that the aqueous and methanol fraction of the leaf shows maximum inhibition against E. coli, Proteus vulgaris, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyrogens, Klebsiella pneumonia, while moderate inhibitory action against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhi (Venkataswamy et al., 2010). Recently, eight Indian medicinal plants were screened for antimicrobial potential. The results were to be found that, the bactericidal potential of thecrude extracts of selected plants i.e. B. persicum, A. concinna, A. lebbeck A. nobilils, G. indica, S. albicaule, V. nigundu, and B. diffusa, and was shown significant performance against all tested bacteria (Menghani et al., 2011).

Phattayakorn and friend (2009) screened antimicrobial potential of various medicinal plants. The results were exposed that; Piper betle could inhibit all strains of bacteria. Furthermore, Phyllanthusemblica (Malacca tree), Senna siamea (cassod tree) and Punica granatum (pomegranate) show greater significant (P ≤ 0.05) antimicrobial activity when compared with other herb extracts, with the zone of inhibition ranging from 12.330.58 to 25.001.73 mm. The ethanol extracts of the three herbs (Malacca tree, cassod tree, and pomegranate) were the most efficient antimicrobial compounds. The values of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC of the herb extracts were 0.3–2.4, >3 and 1.2–2.4% (w/v), respectively (Phattayakorn and Wanchaitanawong, 2009).

Yasmeen et al. (2012) evaluated fourteen plants species. Serial dilution method for antibacterial activity, while Nessler reagents and Colorimetric method were used for estimation of Ammonia and urease activity. The results indicated that, the Allium satvium alcoholic and aqueous fractions had shown (pH: 8.5560, 8.8480, Ammonia: 4.42, 3.52 μg/mL, Urease: 0.009, 0.007 IU/mL respectively) as compared to control positive (pH: 9.03, Ammonia: 6.7 μg/mL, Urease: 0.013 IU/mL). However, alcoholic extracts of Mangifera indica (8.8820, 5.42 μg/mL, 0.010 IU/mL), Mentha piperita (8.8880, 4 μg/mL, 0.008 IU/mL) Carum capticum (8.9540, 4.84 μg/mL, 0.009 IU/mL) and aqueous extract of Opuntia ficusindica (8.8100, 5.22 μg/mL, 0.010 IU/mL) were to be found moderate activity against P. mirabilis. Furthermore, alcoholic and aqueous fractions of Euclyptus camalduensis (pH: 8.91, 8.96, Ammonia: 5.16, 5.06 μg/mL, Urease: 0.01, 0.01 IU/mL) had poor inhibitory effect. They also reported that all the commercial products were to be found the excellent antibacterial property (pH: 4.8–6.8, Ammonia: 0 μg/mL, Urease: 0 IU/mL). The rest of the herbal extracts were not significantly different (p < 0.05) from positive control. It was concluded that all products had strong antibacterial activity against P. mirabilis (Yasmeen et al., 2012).

Janovska and his coworkers tested ten different plants species. These plants were used against four species of microorganisms: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Bacillus cereus and Staphylococcus aureus. Out of ten medicinal plants, five plants showed antimicrobial potentials, while the Tussilago farfara, Chelidonium majus and Sanguisorba officinalis were most active medicinal plant against antimicrobes (Janovska et al., 2003).

In another study, different plants species were screened for phytochemicals and biological activities. The result exposed that, great potential against antimicrobes were found for the extracts of Syzygyum joabolanum and Caryophyllus aromaticus, which inhibited 57.1% 64.2 and64.2% of the tested bacterial strains, respectively, while strong activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria (83.3%). Some plant extracts were inactive, while in case of association of plant extracts and antibiotic to be found active against antibiotic resistant bacteria. The extracts clove, jambolan, pomegranate and thyme inhibited the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Nascimento et al., 2000).

Acharyya et al. (2009) evaluated the antimicrobial activity total nine plants. All of these plants had a bacterial effect. Furthermore, Syzygium cumini, Skeels (Myrtaceae) and Terminalia chebula Retz (Combretaceae) was observed the most promising bactericidal action, inhibiting the growth of all tested organism, especially Bacillus subtilis, Aeromonas hydrophila and Vibrio cholera. The MBC was found to be in the range of 0.25–4 mg/mL (Acharyya et al., 2009).

Recently, the antimicrobial activities of total nine plants were evaluated. The author reported that among nine plants the most active plants were Muscari Comosun, Rhetinolepi ssp and Tamarix gallica. Among the all tested extracts, the methanolic fraction of Rhetinolepi ssp and aqueous extract of Tamarix gallica were to be found most active, and their diameter was in the range of 15 mm, 22 mm and 10 mm, 17 mm respectively (Zaouia et al., 2010).

In another study, eight plants were reported against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria strains. The microorganisms were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and Proteus mirabilis (CDC S 17), Proteus vulgaris (CDC 527C), and Listeria monocytogenes. Namely, Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 1228), Bacillus subtillis (ATCC 31091), Bacillus cereus (ATCC 11778), Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC14028), Psedudomonas aeruginoas (ATCC 9027), E. coli (ATCC 31165), Salmonella enteritidis (ATCC 4931), Klebsiella pneumonae (ATCC 13883), E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 43894), Enterobacte aerogenes (ATCC 29010), Shigella dysenteriae (ATCC 29026). The result showed that all plants extracts were active against both tested strains. Furthermore, Gram-negative was found strong potential than Gram positive bacteria (Kang et al., 2011).

Philip et al. (2009) were studied eight plants. The aqueous fraction had no inhibition, while all the tested plants were to be found inactive in Escherichia coli. However, Curcuma manga displayed action against the tested bacterial strain (Philip et al., 2009). In another study the author reported 8 medicinal plants and their various parts; the results showed that the essential oils of T. daenensis and M. communis were most active against antimicrobes. The MIC values were to be found for essential oils and active extract 0.039 and 10 mg/ml. Furthermore, some plants extracts and their oils also used as food preservation (Ghasemi et al., 2010).

Recently, seven medicinal plants were examined for antibacterial potential, the result indicated that the methnolic extract of Phyllanthus niruri (stone breaker) was to be found strong action against Staphylococcus sp, while the aqueous and methanolic fraction had minimum activity as compared to methanolic (Selvamohan et al., 2012). The author used total six plants, against dental pathogens. All the plants were active against all the tested pathogens. The methanolic extract of T. chebula was to be observed highest zone of inhibition against S. aureus 27 mm, while the lowest value for petroleum ether extract of A. aspera and M. elengi against S. aureusand S. mutans (9 mm). It was concluded that high contents of phytochemicals in these plants might have exerted synergistic antimicrobial effect (Prabhat and Navneet, 2010).

Hassan and his company screened various medicinal plants. The result indicated that Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa were the most inhibited microorganisms. The extract of Sphareranthu hirtus was the most active against multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and enterohemorrhagic E. coli. The ethanolic extract of S. hirtus exhibited a higher effect than the hot water extract (Hassan et al., 2009). The author investigated six plants leaves against Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and E. coli. The result was to be found that, the aqueous lemon leaf fraction against E. coli, while Eucalyptus leaf ethanol extract against Klebsiella shows potent activity. Furthermore, except Tulsi plant, Pseudomonas showed resistant to all tested fractions (Zwetlana et al., 2014).

Johnson and his colleagues (2011) screened five important medicinal plants, and the results observed that the maximum of Aloevera plant was to be exposed against S. aureusand E. coli, while Lanatacamara inactive against bacterial strains. However, the aqueous fraction of the Pongamia pinnata had more active as compared to alcoholic extract against E. coli. Calotropis procera medicinal plant showed antibacterial potential against E. coli and Staphyloccus aureus, while Datura stramonium only active against Staphyloccus aureu (Johnson et al., 2011).

3. A novel application of plant extracts against honey bee pathogens

Honeybees would seem particularly vulnerable to pests and pathogens as each colony is a dense group of individuals. Although honeybees possess many types of defenses against diseases, such as hygienic behavior or the production of anti-microbial substances, colonies still suffer from a number of diseases and pests (Martin, 2001, Simone-Finstrom et al., 2017). But they are threatened by various pathogens like Gut microflora and parasitic mites globally and this may lead to serious consequences (Ansari et al., 2017). Some of the important pathogens of Honey bees are Paenibacillus larva (Bacteria), Varroa destructor (mite) and Ascosphaera apis (Fungi).

Recently, it was demonstrated that, in Europe and the US, prominent losses of honeybee colonies are associated with the mite Varroa destructor (Ryabov et al., 2017, Oddie et al., 2017). The spore-forming bacterium Paenibacillus larvae (Genersch, 2010) are the agent causing American foulbrood (AFB) (Alvarado et al., 2017). It is a widespread larval pathogen of the honey bee, infecting young larvae through ingestion of contaminated food. The bacterial spores germinate and proliferate in the midgut lumen after which they start to breach the epithelium and invade the haemocoel. Young larvae (from the first and second instars) are highly susceptible to this disease and can become infected by as few as 10 spores. However, the dosage-mortality relationship is greatly affected by larval age, genetic makeup and bacterial strain. This disease can be mitigated both through hygienic behavior by adult workers and through larval resistance traits (Qin et al., 2006).

Besides that, essential oils are being used to control these microbial strains. Such strategy allows an alternative way for the control of this serious disease affecting honey and its by-products (wax, pollen and propolis). Also, it can meet consumer demand for a diminution or absence of other antimicrobial chemical substances, which can be substituted by the addition of natural substances.

More, recently in vitro studies have revealed that propolis, and specific compounds within propolis, prevent the development of two infectious pathogens of honey bees, Paenibacillus larvae and Ascosphaera apis (Wilson et al., 2017, Borba and Spivak, 2017).

The essential oils proved to be highly effective against Paenbacillus larvae are Jamaica pepper oil (Pimenta dioica), mountain pepper oil (Litsea cubeba), ajwain oil (Trachyspermum ammi), corn mint oil, spearmint oil (Mentha spicata), star anise oil (Illicium verum), nutmeg oil (Myristica fragrans), camphor oil (Cinnamomum camphora) (Ansari et al., 2016), Barbaka (Vitex trifolia) and neem extracts (Azadirachta indica) (Anjum et al., 2015), nettle (Urtica dioica), Basil (Ocimum basilicum) (Mărghitaş et al., 2011), Argyle apple (Eucalyptus cinerea), Peperina (Minthostachys verticillata) (Gonzalez and Marioli, 2010), Nepeta clarkei water extracts against honey bee pathogen Paenibacillus larvae (Anjum et al., 2017) laurel (Laurus nobilis) (Damiani et al., 2014), Coronilha (Scutia buxifolia) (Boligon et al., 2013), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi) (Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b), wormwood (Artemisia absinthium),sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua), Lepechinia floribunda (pitchersages) (Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b), Achyrocline satureioides (Macela) (Sabaté et al., 2012), (Flourensia riparia),(Flourensia fiebrigii) (Reyes et al., 2013), Hypericum perforatum (Hernández-López et al., 2014) (as mentioned in Table 4).

Table 4.

Botanical compounds for the control of the honeybee pathogen.

| S. no | Plant | Common name | Mites | Bacteria | Fungus | Part used | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Trachyspermumammi | Ajwain | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 2. | Prunusglandulosa | Almond | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 3. | Ocimumtenuiflorum | Tulsi | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 4. | Citrus bergamia | Bergamot | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 5. | Juniperusvirginia | Cedar wood | P. larvae | Wood | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 6. | Azadirachtaindica | Neem | P. larvae | Seed | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 7. | Elettariacardamomum | Cardamom | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 8. | Murrayakoenigii | Curry | P. larvae | Leaves | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 9. | Zingiberofficinale | Ginger | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 10. | Vetiveriazizanoides | Khus | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 11. | Daucuscarota | Carrot | P. larvae | Seed | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 12. | Laurusnobilis | Bay | P. larvae | Leaves | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 13. | Citrus bergamia | Bergamot | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 14. | Melaleucaleucadendron | Cajuput | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 15. | Cinnamomumcamphora | Camphor | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 16. | Pimentadioica | Jamaica pepper | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 17. | Litseacubeba | Mountain pepper | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 18. | Myristicafragrans | Nutmeg | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 19. | Anibarosaeodora | Rosewood | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 20. | Menthaspicata | Spearmint | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 21. | Illiciumverum | Star anise | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 22. | Linumusitatissimum | Linseed | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 23. | Matricariachamomilla | Babuna | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 24. | Menthaarvensis | Corn mint | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 25. | Anethumgraveolens | Dill | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 26. | Pelargonium graveolens | Geranium rose | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 27. | Simmondsiachinensis | Jojoba | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 28. | Sesamumindicum | Sesame | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 29. | Triticumvulgare | Wheat germ | P. larvae | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2016) | ||

| 30. | Baccharis flabellate | Groundsel bush | V. destructor | Whole plant | Damiani et al. (2011) | ||

| 31. | Minthostachysverticillata | Peperina | V. destructor | Whole plant | Damiani et al. (2011) | ||

| 32. | Lavandula x intermedia | Lavandin | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 33. | Coriandrumsativum | Coriander | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 34. | Laurusnobilis | Laurel | Ascosphaeraapis | Leaves | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 35. | Cinnamomumglandulifera | False camphor | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 36. | Ocimumbasilicum | Basil | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 37. | Tagetesminuta | Tagetes | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 38. | Rosmarinusofficinalis | Rosemary | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 39. | Eucalyptus globulus | Eucalyptus | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Larrán et al. (2001) | ||

| 40. | Polygonumbistorta | Bistort or snakeroot | Paenibacillus larvae | Leaves, stem, flower, fruit | Cecotti et al. (2012) | ||

| 41. | Polygonumbistorta | Bistort or snakeroot | Melissococcusplutonius | Leaves, stem, flower, fruit | Cecotti et al. (2012) | ||

| 42. | Tasmannialanceolata | Mountain pepper | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 43. | Syzygiumaromaticum | Clove | Ascosphaeraapis | Bud | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 44. | Piper betle | Betel | Ascosphaeraapis | Leaves | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 45. | Anisomelesindica | Kala Bhangra | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 46. | Minthaspicata | Spearmint | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 47. | Matricariachamomila | Babuna or chamomile | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 48. | Daucuscarota | Carrot | Ascosphaeraapis | Seed | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 49. | Cuminumcyminum | Cumin | Ascosphaeraapis | Seed | Ansari et al. (2017) | ||

| 50. | Ocimumgratissimum | Clove basil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 51. | Allium sativum | Garlic | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 52. | Aeglemarmelos | Stone apple | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 53. | Pelargonium graveolens | Geranium rose oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 54. | Callistemon citrinus | Bottle brush oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 55. | Myristicafragrans | Nutmeg oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 56. | Cymbopogon martini | Palmrosa oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 57. | Elettariacardamomum | Cardamom oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 58. | Foeniculumvulgare | Fennel seed oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 59. | Trachyspermumammi | Ajwain oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 60. | Anethumgraveolens | Dill oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 61. | Cannabis sativa | Hempseed oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 62. | Glebioniscoronaria | Garland Daisy oil | Whole plant | Ansari et al. (2017) | |||

| 63. | Azadirachtaindica | Neem | Varroajacobsoni | Whole plant | Melathopoulos et al. (2000) | ||

| 64. | Brassica napus | Canola oil | Varroajacobsoni | Whole plant | Melathopoulos et al. (2000) | ||

| 65. | Azadirachtaindica | Neem | Acarapiswoodi | Whole plant | Melathopoulos et al. (2000) | ||

| 66. | Brassica napus | Canola oil | Acarapiswoodi | Whole plant | Melathopoulos et al. (2000) | ||

| 67. | Lavandulaangustifolia | English lavender | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 68. | Rosmarinusofficinalis | Rosemary | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 69. | Salvia officinalis | Sage | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 70. | Thymus vulgaris | Thyme | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 71. | Menthapiperita | Peppermint | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 72. | Pelargonium graveolens | Rose geranium | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 73. | Prunusdulcis | Almond | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 74. | Citrus aurantium | Key lime | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 75. | Oleaeuropaea | Olive | Ascosphaeraapis | Whole plant | Boudegga et al. (2010) | ||

| 76. | Laurusnobilis | Bay laurel | Nosemaceranae | Whole plant | Porrini et al. (2011) | ||

| 77. | Rosmarinusofficinalis | Rosemary | V. destructor | P. larvae | Whole plant | Maggi et al. (2011) | |

| 78. | Azadirachtaindica | Neem | V. destructor | Paenibacillus larvae | Whole plant | Anjum et al. (2015) | |

| 79. | Vitextrifolia | Barbaka | V. destructor | Paenibacillus larvae | Whole plant | Anjum et al. (2015) | |

| 80. | Azadirachtaindica | Neem | Bacillus subtilis | Whole plant | Anjum et al. (2015) | ||

| 81. | Azadirachtaindica | Neem | Staphylococcus hominis | Whole plant | Anjum et al. (2015) | ||

| 82. | Vitextrifolia | Barbaka | Bacillus subtilis | Whole plant | Anjum et al. (2015) | ||

| 83. | Vitextrifolia | Barbaka | Staphylococcus hominis | Whole plant | Anjum et al. (2015) | ||

| 84. | Carapaguianensis | Andiroba oil | P. larvae | Whole plant | Santos et al. (2012) | ||

| 85. | Copaiferalangsdorffii | Copaíba oils | P. larvae | Whole plant | Santos et al. (2012) | ||

| 86. | Lepidiumlatifolium | Pepperwort | V. destructor | Whole plant | Razavi et al. (2015) | ||

| 87. | Zatariamultiflora | Satar | V. destructor | Whole plant | Razavi et al. (2015) | ||

| 88. | Populusfremontii | Fremonts cottonwood | P. larvae | Ascosphaeraapis | Leaves | Wilson et al. (2017) | |

| 89. | Oleaeuropea | Olive | P. larvae | Leaves | ARENAS (2015) | ||

| 90. | Oleaeuropea | Olive | Nosema species | Leaves | ARENAS (2015) | ||

| 91. | Oleaeuropea | Olive | Melissococcusplutomius | Leaves | ARENAS (2015) | ||

| 92. | Thymus satureioides | Thyme | V. destructor | Whole plant | Ramzi et al. (2017) | ||

| 93. | Origanumelongatum | Majorana | V. destructor | Whole plant | Ramzi et al. (2017) | ||

| 94. | Lippiaberlandieri | Oregano | Beauveriabassiana | Whole plant | Ramzi et al. (2017) | ||

| 95. | Lippiaberlandieri | Oregano | Metarhiziumanisopliae | Whole plant | Ramzi et al. (2017) | ||

| 96. | Thymus kotschyanus | Thymol | V. destructor | Whole plant | Ghasemi et al. (2011) | ||

| 97. | Ferula assa–foetida | Devils dung | V. destructor | Whole plant | Ghasemi et al. (2011) | ||

| 98. | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | River red gum | V. destructor | Whole plant | Ghasemi et al. (2011) | ||

| 99. | Ocimumbasilicum | Basil | P. larvae | Whole plant | Mărghitaş et al. (2011) | ||

| 100. | Thymus vulgaris | Thyme | P. larvae | Whole plant | Mărghitaş et al. (2011) | ||

| 101. | Urticadioica | Nettle | P. larvae | Whole plant | Mărghitaş et al. (2011) | ||

| 102. | Humuluslupulus | Common hop | P. larvae | Whole plant | Flesar et al. (2010) | ||

| 103. | Myrtuscommunis | Myrtle | P. larvae | Whole plant | Flesar et al. (2010) | ||

| 104. | Achyroclinesatureioides | Macela | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 105. | Chenopodiumambrosioide | Wormseed | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 106. | Eucalyptus cinerea | Argyle apple | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 107. | Gnaphaliumgaudichaudianum | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | |||

| 108. | Lippiaturbinata, | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | |||

| 109. | Marrubiumvulgare | Common horehound | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 110. | Minthostachysverticillata | Peperina | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 111. | Origanumvulgare | Common origanum | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 112. | Tagetesminuta | Black mint | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 113. | Thymus vulgaris | Thyme | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gonzalez and Marioli (2010) | ||

| 114. | Laurusnobilis | Bay laurel | P. larvae | Whole plant | Damiani et al. (2014) | ||

| 115. | Piper betle | Betel | A. apis | Whole plant | Chantawannakul et al. (2005) | ||

| 116. | Cinnamomum cassia | Cassia | A. apis | Whole plant | Chantawannakul et al. (2005) | ||

| 117. | Lavendulaangustifolia | Lavenda | V. destructor | Whole plant | Damiani et al. (2009) | ||

| 118. | Laurusnobilis | Laurel | V. destructor | Leaves | Damiani et al. (2009) | ||

| 119. | Thymus vulgaris | Thyme | V. destructor | Whole plant | Damiani et al. (2009) | ||

| 120. | Scutiabuxifolia | Coronilha | Paenibacillus species | Whole plant | Boligon et al. (2013) | ||

| 121. | Acantholippiaseriphioides | Andean thyme | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al. (2007) | ||

| 122. | Citrus paradise | Grape fruit | P. larvae | Fruit | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | ||

| 123. | ‘Citrus sinensis | Sweet orange | Fruit | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | |||

| 124. | Citrus limon | Lemon | Fruit | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | |||

| 125. | Citrus nobilis | Mandarin | Fruit | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | |||

| 126. | Artemisia absinthium | Wormwood | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | ||

| 127. | Artemisia annua | Sweet wormwood | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | ||

| 128. | Lepechinia floribunda | Pitchersages | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al., 2008a, Fuselli et al., 2008b) | ||

| 129. | Tagetesminuta | Black mint | V. destructor | P. larvae | A. apis | Whole plant | Eguaras et al. (2005) |

| 130. | Tessoriaabsinthium | A. apis | Whole plant | Dellacasa et al. (2003) | |||

| 131. | Aloysiagratissima | Whitebrush | A. apis | Whole plant | Dellacasa et al. (2003) | ||

| 132. | Heterothecalatifolia | Camphorweed | A. apis | Whole plant | Dellacasa et al. (2003) | ||

| 133. | Lippiajuneliana | A. apis | Whole plant | Dellacasa et al. (2003) | |||

| 134. | Lippiaintegrifolia | A. apis | Whole plant | Dellacasa et al. (2003) | |||

| 135. | Lippia turbinate | A. apis | Whole plant | Dellacasa et al. (2003) | |||

| 136. | Achyroclinesatureioides | Macela | P. larvae | Whole plant | Sabaté et al. (2012) | ||

| 137. | Thyme | Varroa mites | Whole plant | Ariana et al. (2002) | |||

| 138. | 0 | Savory | Varroa mites | Whole plant | Ariana et al. (2002) | ||

| 139. | Menthaspicata | Spearmint | Varroa mites | Whole plant | Ariana et al. (2002) | ||

| 140. | Flourensiariparia | P. larvae | Whole plant | Reyes et al. (2013) | |||

| 141. | Flourensiatortuosa | P. larvae | Whole plant | Reyes et al. (2013) | |||

| 142. | Flourensiafiebrigii | P. larvae | Whole plant | Reyes et al. (2013) | |||

| 143. | Hypericum species | P. larvae | Whole plant | Hernández-López et al. (2014) | |||

| 144. | Pimpinellaanisum | Green anise | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gende et al. (2009) | ||

| 145. | Foeniculumvulgare | Fennel | P. larvae | Whole plant | Gende et al. (2009) | ||

| 146. | Melaleucaviridiflora | Niaouli | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al. (2010) | ||

| 147. | Melaleucaalternifolia | Tea tree | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al. (2010) | ||

| 148. | Cymbopogonnardus | Citronella grass | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al. (2010) | ||

| 149. | Cymbopogonmartinii | Palmarosa | P. larvae | Whole plant | Fuselli et al. (2010) | ||

| 150. | Cinnamomumverum | Cinnamon | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Whole plant | Calderone et al. (1994) | |

| 151. | Laurusnobilis | Bay leaf | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Whole plant | Calderone et al. (1994) | |

| 152. | Cinnamomumcamphora | Camphor | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Whole plant | Calderone et al. (1994) | |

| 153. | Syzyygiumaromaticum | Clove | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Whole plant | Calderone et al. (1994) | |

| 154. | Cymbopogonwinterianus | Citronellal | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Leaves and stem | Calderone et al. (1994) | |

| 155. | Origanumvulgare | Origanum | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Whole plant | Calderone et al. (1994) | |

| 156. | Thymus vulgarus | Thyme | Bacillus larva | A. apis | Whole plant | Calderone et al. (1994) |

It is an ecto-parasitic mesostigmata mite. Varroa causes many physical and physiological detrimental effects at the individual bee and colony levels. Repeated Varroa feeding on adult bee and brood hemolymph injures the bees physically, leads to a reduction in their protein content and wet and dry body weights, and interferes with organ development. In addition, the parasitic mite and the viruses they vector contribute to morphological deformities like small body size, shortened abdomen, deformed wings. These morphological deformities reduce vigor and longevity. They also affect flight duration and the homing ability of foragers (Conte et al., 2010).

The Varroa mite is responsible for the horizontal and vertical transmission of many viruses like DWV, SBV, APV, IAPV and KBV. The horizontal transmission of viruses from nurse bees to larvae occurs through larval food and via brood to adults (Conte et al., 2010). Usually, untreated Varroa-infested colonies usually die within six months to two years of mite infestation at the colony level (Conte et al., 2010). V. destructor is supposed to be a very serious threat to the honey bees. Varroa parasitism plays in the recent honey bee losses worldwide (Conte et al., 2010). To lower the hazardous effects caused by V. destructor, several plant extracts have been found to be extremely effective. These are Groundsel bush (Baccharis flabellate), Peperina (Minthostachys verticillata) (Damiani et al., 2011), Pepperwort (Lepidium latifolium) (Razavi et al., 2015), Thymol (Thymus kotschyanus) (Ghasemi et al., 2011), Laurel (Laurus nobilis), thyme (Damiani et al., 2009), savory, spearmint (Ariana et al., 2002).