Abstract

Background:

Pediatric healthcare quality in the U.S. varies but the reasons for variation are not fully understood. Differences in pediatric practices’ organizational characteristics, such as organizational structures, strategies employed to improve quality, and other contextual factors may contribute to the variation observed.

Purpose:

To assess the relationship between organizational characteristics and performance on clinical quality (CQ) and patient experience (PE) measures in primary care pediatric practices in Massachusetts.

Methodology:

A 60-item questionnaire that assessed the presence of selected organizational characteristics was sent to 172 pediatric practice managers in Massachusetts between December 2017 and February 2018. The associations between select organizational characteristics and publicly available CQ and PE scores were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA); open-ended survey questions were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results:

86 practices (50.0%) responded; 80 (46.5%) were included in the primary analysis. Having a quality champion (p=0.03); offering co-located specialty services (e.g., behavioral health) (p=0.04); being a privately-owned practice (p=0.04); believing that patients and families feel respected (p=0.03); and having a lower percentage of patients (10% to 25%) covered by public health insurance (p=0.04) were associated with higher CQ scores. Higher PE scores were associated with private practice ownership (p=0.0006). Qualitative analysis suggested organizational culture and external factors, such as healthcare finance, may affect quality.

Conclusions:

Both modifiable organizational practices and factors external to a practice may affect quality of care. Addressing differences in practice performance may not to be reducible to implementation of changes in single organizational characteristics.

Practice Implications:

Pediatric practices seeking to improve quality of care may wish to adopt the strategies that were associated with higher performance on quality measures, but additional studies are needed to better understand the mechanisms behind these associations and how they relate to each other.

Introduction

Despite efforts to improve quality of care through programs such as the Patient Centered Medical Home and quality improvement (QI) collaboratives, many children in the U.S. do not receive care consistent with evidence-based guidelines (Aysola, Bitton, Zaslavsky, & Ayanian, 2013; Bordley, Margolis, Stuart, Lannon, & Keyes, 2001; Chien et al., 2017; Mangione-Smith et al., 2007). Although a number of factors likely contribute to the quality of care a practice provides, organizational characteristics, such as specific strategies to improve quality, and contextual factors are increasingly thought to play a role in variations in care (Vartak, n.d.; Vaughn et al., 2002; West, 2000). The relationship between organizational characteristics and quality of care has been extensively studied for adults, but the lessons learned in studies of adult care may not apply in pediatric primary care due to the prevention-oriented nature of pediatric care and the role of parents’ in children’s healthcare.

Studies of the relationship between organizational characteristics and pediatric primary care quality have found that team-based approaches to care (Chuang et al., 2017) and a “QI culture” (McAllister, Cooley, Van Cleave, Boudreau, & Kuhlthau, 2013) are associated with specific aspects of care quality. However, these and other pediatric studies have focused either on disease-specific quality issues or a single aspect of preventive care such as vaccination and theoretical approaches to redesigning pediatric primary care delivery have also been described (Batalden et al., 2016; Coker, Windon, Moreno, Schuster, & Chung, 2013). Studies of the relationship between organizational characteristics of a practice, and overall performance on measures of care quality are lacking.

This study sought to address this gap in knowledge by determining the relationship between organizational characteristics and performance on composite clinical quality (CQ) and patient experience (PE) measures for pediatric primary care practices in Massachusetts. Results of the study may inform future efforts to improve pediatric primary care quality.

Theory

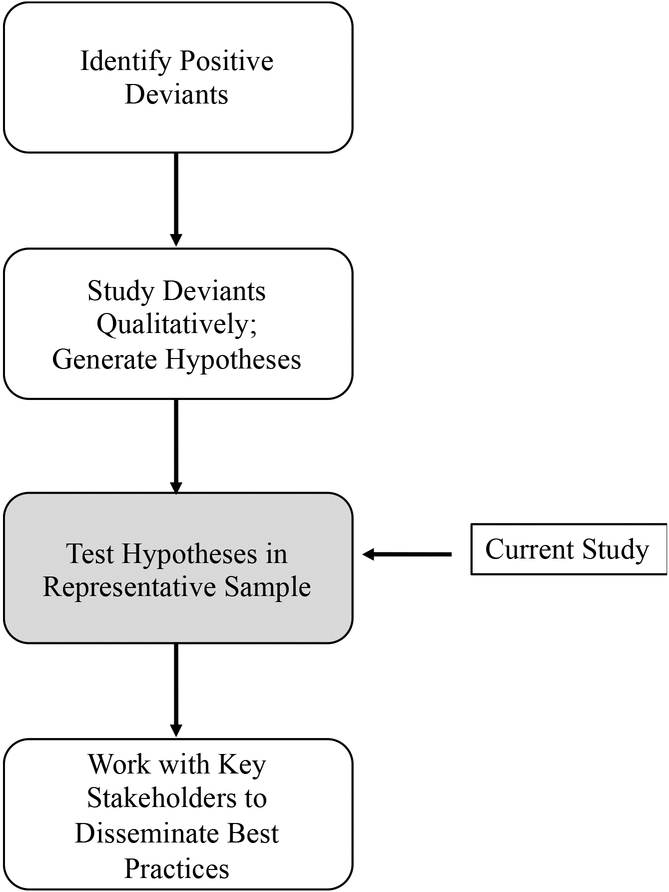

Positive Deviance is a framework for understanding why some individuals, communities, organizations, or other social units achieve more desirable outcomes than similar social units that have access to similar resources (Bradley et al., 2009). Comprised of four steps (Figure 1) the framework calls for first identifying “positive deviants” or groups that demonstrate consistently higher performance than other similar groups in the area of interest. Positive deviants are then studied using qualitative methods to generate hypotheses regarding the practices that enable the unit to achieve higher performance. In the third phase, hypotheses are tested statistically in a larger representative sample; in the fourth phase, newly identified best practices are disseminated to potential adopters (Lawton, Taylor, Clay-Williams, & Braithwaite, 2014).

Figure 1.

Positive Deviance

Adapted from (Lawton, Taylor, Clay-Williams. & Braithwaite, 2014)

In a previous study, we conducted the first two steps of the Positive Deviance framework by identifying primary care pediatric practices that achieved high scores on clinical quality (CQ) and patient experience (PE) quality measures and interviewing pediatric providers and staff at these high performing organizations to generate hypotheses as to the organizational or practice characteristics (organizational structures, strategies, and contextual factors) that may have enabled these practices to deliver the highest quality of care. This study is described in greater detail in the methods section (full study reported separately). The current focused on the third step in the positive deviance framework by testing the hypotheses generated in the second phase. Organizational characteristics identified in the second phase were used to develop the questionnaire for the survey conducted in the current study. The questionnaire aimed to identify potentially modifiable organizational characteristics associated with higher quality of care.

Methods

Overview

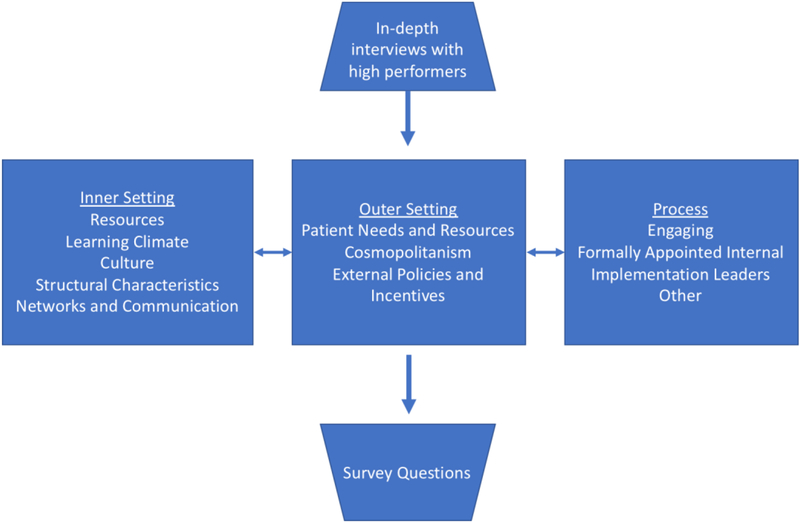

In a prior study, we identified “positive deviant” practices using publicly available scores on quality measures (“Healthcare Compass MA,” n.d.) to calculate composite quality scores. In-depth semi-structured individual and small group interviews were conducted with pediatric providers and staff at 10 “high performing” practices. Practices were purposively selected based on ranking in the top quartile for composite CQ and PE scores, size of the practice, geographic location in the state, practice type (private, hospital-owned), and median income for zip code. The interviews aimed to elicit participants’ thoughts on why their practice performed well on quality measures and probed specific strategies the practices employed to improve care quality. Transcripts of the interviews were analyzed using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The themes that emerged from line coding, fit closely with three Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) domains, including 13 constructs found within these domains (Figure 2). The CFIR framework is designed to be used in systematic analyses of multi-level contributors to facilitators and barriers to implementation of evidence-based clinical practices, making it a logical fit for the current study (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Figure 2:

CFIR Domains and Constructs Identified Through In-depth Interviews with High Performing Practices

Questionnaire Development and Administration

The questionnaire aimed to ascertain the presence of the organizational structures, strategies and contextual factors identified in the pediatric primary care practices. The questionnaire was pre-tested with 32 individuals: First, a psychometrician and an expert in healthcare quality metrics assessed the content and structure of the questionnaire. Cognitive interviewing techniques (Subar et al., 1995) were then used to further assess the clarity and completeness of concepts and questions; health services researchers with expertise in questionnaire design and ambulatory clinical staff (e.g., clinicians, nurses, and practice managers) participated in this phase of pilot testing. Finally, both online and paper versions of the questionnaire were pilot tested with a convenience sample of primary care internists and practice managers to assess ease of use of the online version and to determine the average length of time it took respondents to complete the questionnaire. The final questionnaire included a total of 60 yes/no, Likert-style, and open-ended questions. If respondents worked with more than one practice, they were asked to consider only one of the practices in their responses.

All pediatric primary care practices with performance data on the Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP) website were eligible to participate in the study (n=172). MHQP is a non-profit organization that seeks to improve healthcare quality in Massachusetts (“Massachusetts Health Quality Partners,” 2013). MHQP reports scores for eight CQ measures, each of which is based on the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures (“NCQA > HEDIS & Quality Measurement,” 2013). MHQP administers a PE survey biannually and reports scores from this survey in seven categories. Further details of MHQP’s methods for generating CQ and PE performance scores are located available from MHQP.

MHQP staff sent e-mail invitations and up to three reminders with a link to the electronic version of the questionnaire to the practices for which they had active e-mail addresses (n=74). The research team sent a paper copy of the questionnaire with an introductory letter to each practice for which MHQP did not have an e-mail address and to practices that did not respond to the initial e-mail invitation from MHQP. The mailed paper copy of the questionnaire included a stamped, addressed return envelope. The letter sent with the paper version of the questionnaire included a link to the electronic version and the practice’s unique identification number so that respondents could choose to respond electronically. Up to five reminders were sent after the initial contact and all practices were given $10 cash in appreciation of their time (Dillman, 2011). REDCap, a secure, web-based data management system (Harris et al., 2009) was used to administer the electronic version of the questionnaire; paper questionnaire responses were entered into the REDCap database by a research assistant.

Outcomes

To assess the relationship between organizational strategies, contextual factors, and performance on quality measures, we first calculated average CQ and PE scores for each practice using scores reported on the MHQP website in November 2017. MHQP classifies practices’ scores into one of four categories of performance and represents practices’ scores graphically on their website with circles similar to the representation formerly used by Consumer Reports (full circle+=highest score; empty circle=lowest score). Average CQ and PE scores were calculated for practices that had scores on four or more CQ or PE measures; four was selected as a cutoff to maximize both the number of scores included in the average and the number of practices eligible to be included. A full circle + was assigned 3 points; a full circle was 2 points, a half circle was 1 point; and an empty circle was 0 points.

Quantitative Analysis

Analysis of variance models (functionally t-tests when used with two groups) were used to test the association between each predictor variable (organizational strategy/contextual factor) and practice average CQ and PE scores. Likert-style questions were dichotomized into “strongly agree” vs. all other, reflecting response distributions. A practice was considered to have higher than expected average CQ/PE score when an organizational strategy or contextual factor was present compared to the referent group if the parameter estimate was positive. Multivariable analyses were not conducted due to insufficient power and high independent variable correlation. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Qualitative Analysis

Open-ended survey questions elicited participants’ perspectives on: 1) Barriers to providing high quality care;; and 2) Additional thoughts on factors that impact pediatric healthcare quality. These responses were combined and analyzed for thematic content using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A codebook was developed after reading all of the open-ended responses, and codes were assigned to comment excerpts. Codes were then organized into major themes with associated subthemes using CFIR domains as an organizing framework.

Results

A total of 86 questionnaires were returned from the 172 pediatric practices surveyed (50.0%); seven had participated in the in-depth interviews conducted in the first phase of the study. Two questionnaires were missing the practice identification number and were excluded from the primary analysis. Four of the respondents served as practice managers for two different practices, each of which had unique quality scores. We contacted these respondents to ascertain which practice they had in mind when they completed the questionnaire; this resulted in 80 practices eligible for the analysis. Of these, 66 had CQ scores reported on the MHQP website and 61 of these had scores for four or more measures. For PE scores, 63 practices had scores on the MHQP website; 61 had scores for four or more PE measures. The median composite quality scores were 1.83 (IQR=1.63 to 2.00) for CQ and 1.71 (IQR=1.57 to 1.86) for PE. We found no statistically significant differences between responding and non-responding practices on the following characteristics: number of providers, median CQ scores, median PE scores, median income for the zip code in which the practice was located, and private vs. non-private practice status. We also did not find differences in average practice PE or CQ scores for responding practices compared to non-responding practices.

Practice characteristics are located in Table 1 and demographic information for the individuals who responded for their practice are located in Table 2. Responses to yes/no questions demonstrated that 67 practices (83.8%) were part of a network (e.g., physician-hospital organization); 65 (81.3%) had processes in place for measuring the impact of QI interventions; other strategies were less commonly employed.

Table 1:

Practice Characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 100 | |

| # Sites seeing exclusively pediatric patients | ||

| 1 | 39 | 48.8 |

| 2 | 12 | 15.0 |

| 3 | 5 | 6.25 |

| 4 or more | 15 | 18.8 |

| I Don’t Know | 7 | 8.75 |

| No response | 2 | 2.5 |

| # Pediatric clinicians | ||

| No response | 2 | 2.5 |

| 1–2 | 2 | 2.5 |

| 3–5 | 24 | 30.0 |

| 6–10 | 27 | 33.8 |

| More than 10 | 25 | 31.3 |

| Percentage patients with public insurance or uninsured | ||

| No response | 5 | 6.25 |

| Less than 10% | 12 | 15.0 |

| 10–24% | 18 | 22.5 |

| 25–49% | 24 | 30.0 |

| 50–74% | 17 | 21.3 |

| More than 75% | 4 | 5.0 |

Table 2:

Respondent Characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 100 | |

| Role in practice | ||

| Practice manager | 58 | 72.5 |

| Nurse manager | 6 | 7.5 |

| Physician owner | 1 | 1.25 |

| Physician leader | 4 | 5.0 |

| Other | 9 | 11.3 |

| No response | 2 | 2.5 |

| Years in current role | ||

| Less than 2 years | 5 | 6.25 |

| 2–5 years | 7 | 8.75 |

| 6–10 years | 12 | 15.0 |

| 11–15 years | 8 | 10.0 |

| 16–20 years | 18 | 22.5 |

| More than 20 years | 28 | 35.0 |

| No response | 2 | 2.5 |

| Education | ||

| No degree | 17 | 21.3 |

| Associate degree | 15 | 18.8 |

| Bachelors’ degree | 18 | 22.5 |

| MBA/MPH/MSc | 6 | 7.5 |

| LPN/RN | 10 | 12.5 |

| MD | 5 | 6.25 |

| Other/no response | 9 | 11.3 |

| Age | ||

| 26–35 years | 8 | 10.0 |

| 36–45 years | 17 | 21.3 |

| 46–55 years | 17 | 21.3 |

| 56–65 years | 31 | 38.8 |

| More than 65 years | 3 | 3.75 |

| No response | 4 | 5.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 66 | 82.5 |

| Male | 10 | 12.5 |

| Non-binary | 1 | 1.25 |

| No response | 3 | 3.75 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-white/no response* | 14 | 17.5 |

| White | 66 | 82.5 |

Associations between organizational strategies, contextual factors, and quality scores

The following organizational characteristics were associated with higher average scores on CQ measures (p<0.05): offering co-located specialty services (e.g., behavioral health, social work) (p=0.04); being a privately-owned practice (p=0.04); having a designated quality champion (p=0.03); and believing that patients and families feel respected by staff and clinicians (p=0.03). Several other organizational strategies and contextual factors approached statistical significance for association with higher CQ scores (Table 3). Neither use of technology for QI, nor being part of a network, such as a physician-hospital organization was associated with higher CQ scores. Privately-owned practices were more likely to be mid-sized (6 to 10 providers) and to have a lower percentage of patients insured by Medicaid.

Table 3:

Univariate Associations Between Organization Strategies and Contextual Factors and Performance on Quality Measures by Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Category

| CFIR Domain | CQ | PE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average CQ score (SE) (Strongly agree/Yes) | Average CQ score (SE) (Do not strongly agree/No) | p-value | Average PE score (SE) (Strongly agree/Yes) | Average PE score (SE) (Do not strongly agree/No) | p-value | |

| Inner Setting - Structural | ||||||

| Scribes^ | 1.78 (0.19) | 1.80 (0.04) | 0.93 | 1.53 (0.18) | 1.73 (0.04) | 0.27 |

| Co-located specialty services^ | 1.85 (0.05) | 1.66 (0.08) | 0.04 | 1.73 (0.05) | 1.71 (0.07) | 0.87 |

| Privately owned^ | 1.86 (0.05) | 1.68 (0.07) | 0.04 | 1.82 (0.04) | 1.55 (0.06) | 0.0006 |

| Practice leaders offer professional development * | 1.78 (0.07) | 1.81 (0.05) | 0.73 | 1.65 (0.06) | 1.76 (0.05) | 0.19 |

| Adequate medical assistant staffing. * | 1.90 (0.08) | 1.77 (0.05) | 0.18 | 1.74 (0.08) | 1.72 (0.05) | 0.78 |

| Adequate front desk staffing * | 1.89 (0.07) | 1.76 (0.05) | 0.15 | 1.82 (0.07) | 1.67 (0.05) | 0.09 |

| Adequate nurse staffing * | 1.80 (0.08) | 1.80 (0.05) | 0.94 | 1.78 (0.07) | 1.70 (0.05) | 0.33 |

| Adequate clinician staffing * | 1.87 (0.06) | 1.75 (0.05) | 0.19 | 1.80 (0.06) | 1.67 (0.05) | 0.12 |

| Have the resources needed to carry out QI initiatives * | 1.81 (0.07) | 1.79 (0.05) | 0.83 | 1.71 (0.07) | 1.73 (0.05) | 0.88 |

| Have skills needed for QI initiatives * | 1.87 (0.07) | 1.75 (0.05) | 0.16 | 1.77 (0.06) | 1.69 (0.05) | 0.35 |

| Inner Setting - Climate/Culture | ||||||

| Practice leaders are approachable * | 1.84 (0.05) | 1.70 (0.08) | 0.14 | 1.74 (0.05) | 1.68 (0.07) | 0.51 |

| Our practice feels like a family * | 1.82 (0.06) | 1.78 (0.06) | 0.69 | 1.79 (0.06) | 1.67 (0.05) | 0.13 |

| Front desk staff feel valued * | 1.87 (0.08) | 1.77 (0.05) | 0.28 | 1.77 (0.08) | 1.71 (0.05) | 0.47 |

| Medical assistants feel valued * | 1.84 (0.07) | 1.78 (0.05) | 0.53 | 1.73 (0.07) | 1.72 (0.05) | 0.88 |

| Nurses feel valued * | 1.81 (0.08) | 1.80 (0.05) | 0.87 | 1.71 (0.08) | 1.73 (0.05) | 0.88 |

| Clinicians feel valued * | 1.87 (0.07) | 1.76 (0.05) | 0.21 | 1.78 (0.06) | 1.69 (0.05) | 0.26 |

| Clinicians and staff communicate well * | 1.83 (0.07) | 1.78 (0.05) | 0.58 | 1.82 (0.07) | 1.67 (0.05) | 0.08 |

| Patients and families feel respected * | 1.90 (0.06) | 1.71 (0.05) | 0.03 | 1.80 (0.06) | 1.65 (0.05) | 0.06 |

| Patients and families trust * | 1.86 (0.06) | 1.72 (0.06) | 0.12 | 1.79 (0.05) | 1.64 (0.06) | 0.07 |

| Outer Setting | ||||||

| Part of a network^ | 1.80 (0.05) | 1.79 (0.10) | 0.88 | 1.71 (0.04) | 1.81 (0.10) | 0.35 |

| Patient experience measures reflect quality of care * | 1.81 (0.07) | 1.79(0.05) | 0.85 | 1.80 (0.06) | 1.67 (0.05) | 0.13 |

| Clinical quality measures reflect the quality of care * | 1.87 (0.06) | 1.75 (0.05) | 0.17 | 1.79 (0.06) | 1.67 (0.05) | 0.15 |

| Quality scores are influenced by factors we have no control over | 1.86 (0.10) | 1.78 (0.05) | 0.46 | 1.66 (0.09) | 1.74 (0.04) | 0.43 |

| We actively seek to address healthcare disparities * | 1.79 (0.08) | 1.80 (0.05) | 0.92 | 1.74 (0.07) | 1.71 (0.05) | 0.77 |

| Process | ||||||

| Designated quality champion^ | 1.86 (0.05) | 1.66 (0.07) | 0.03 | 1.75 (0.05) | 1.66 (0.07) | 0.29 |

| Process for identifying quality issues^ | 1.81 (0.05) | 1.77 (0.09) | 0.67 | 1.71 (0.04) | 1.75 (0.08) | 0.71 |

| Parent advisoiy board^ | 1.77 (0.09) | 1.81 (0.05) | 0.68 | 1.67 (0.08) | 1.74 (0.05) | 0.47 |

| Study QI changes^ | 1.81 (0.05) | 1.75 (0.09) | 0.54 | 1.72 (0.04) | 1.73 (0.08) | 0.97 |

| Clinicians and staff included in decision-making about quality improvement * | 1.83 (0.07) | 1.78 (0.05) | 0.59 | 1.79 (0.06) | 1.68 (0.05) | 0.17 |

| Use technology for QI * | 1.86 (0.05) | 1.71 (0.07) | 0.09 | 1.77 (0.05) | 1.65 (0.06) | 0.13 |

| Burnout Constructs | ||||||

| Satisfaction with job (Very satisfied) | 1.87 (0.06) | 1.73 (0.06) | 0.1 | 1.77 (0.05) | 1.67 (0.06) | 0.22 |

| Control over work schedule (A lot) | 1.86 (0.06) | 1.73 (0.06) | 0.13 | 1.80 (0.05) | 1.63 (0.06) | 0.03 |

| Emotionally and/or physically drained (Often) | 1.74 (0.06) | 1.86 (0.06) | 0.18 | 1.67 (0.05) | 1.78 (0.06) | 0.21 |

| Practice Characteristics | ||||||

| # Pediatric-only sites | 0.59 | 0.41 | ||||

| 3, 4 or more | 1.72 (0.08) | NA | 1.66 (0.08) | NA | ||

| 2 | 1.72 (0.11) | NA | 1.84 (0.10) | NA | ||

| 1 | 1.81 (0.06) | NA | 1.72 (0.06) | NA | ||

| # Pediatric clinicians | NA | 0.78 | NA | 0.14 | ||

| More than 10 | 1.78 (0.08) | NA | 1.59 (0.08) | NA | ||

| 6–10 | 1.82 (0.07) | NA | 1.79 (0.06) | NA | ||

| 1–2, 3–5 | 1.75 (0.08) | NA | 1.74 (0.07) | NA | ||

| Percentage with public insurance or uninsured | NA | 0.16 | NA | 0.32 | ||

| >=50% | 1.61 (0.09) | NA | 1.68 (0.09) | NA | ||

| 25–49% | 1.84 (0.07) | NA | 1.66 (0.07) | NA | ||

| 10–24% | 1.86 (0.08) | NA | 1.79 (0.08) | NA | ||

| Less than 10% | 1.86 (0.12) | NA | 1.87 (0.10) | NA | ||

CQ= Clinical Quality; PE= Patient. Experience; N/A Not applicable;

referent group=No;

referent group=Agree/Strongly agree;

p<0.05  ;

;

p>0.05</= 0.1

The analysis of the association between organizational strategies and contextual factors and PE scores indicated that being a privately-owned practice and feeling that one has control over one’s schedule (p=0.03) were associated with higher average PE scores (p=0.0006). In addition to this finding, the presence of the following organizational characteristics approached statistical significance for association with higher PE scores: feeling that clinicians and staff communicate well with each other (p=0.08); believing that patients and families feel respected by staff and clinicians (p=0.06); believing that patients and families trust staff and providers (p=0.07); and having adequate nurse staffing (p=0.09) (Table 3).

Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Providing High-Quality Pediatric Care

Twenty-eight participants (35%) provided a total of 51 responses to the survey’s three open-ended questions. Some responses included multiple concepts, resulting in 62 coded excerpts. These coded excerpts fit into two CFIR domains and constructs (in parentheses): 1) Inner Setting (Structural Characteristics, Networks and Communications, Culture, Learning Climate, Leadership Engagement) and 2) Outer Setting (Patient Needs and Resources, External Policies and Incentives). Representative excerpts from respondents’ comments are located in Table 4.

Table 4:

Themes, Sub-themes, and Representative Excerpts from Open-ended Questions

| CFIR Domain | Representative Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Inner Setting | |

| • Staffing • Time • Co-location |

Adequate staff and time are the two things that I feel influence the quality of care a pediatric practice provides. Offering co-located specialty care |

| • Timely appointment | Access to appointments when you need one |

| • Continuity | Multiple locations (i.e., the PCP might not be in the same place you (parent) usually book appointments because they are at the other site |

| • Communication between providers and staff | Having good communication between clinicians and staff is very important so that we are all on the same page |

| • Working well together/respect | Working well with each other |

| • Managing mistakes | …clinicians and staff and having a ‘lesson learned’ attitude to any mistakes that are made. Utilizing ‘teaching moments’ to improve the knowledge base of the staff and clinicians. |

| • Interactions with patients/ families | Treating patient as if they were your own Listening to patients Engaging families |

| • Skilled/knowledgeable staff | I think that having skilled, knowledgeable staff interacting with Pedi patients and parents is key to satisfying this demographic. Regardless of race, gender, ethnicity… |

| • Knowledge/attitudes | Unlike the business world, medical practices are often run by all physicians. They can have limited business process improvement know how, not want to change how they do things and may even resist change as a way to retaliate against insurance companies. |

| Outer Setting | |

| • Electronic Health Record barriers | EHR limitations to capture and report performance |

| Electronic health records slow… down productivity and make clinical care more difficult | |

| • Patient-related barriers | Patients came in without health insurance properly updated |

| • Accountable for patients who are not “ours” | Kids who are over 18 years old and do not come in for regular physicals yearly; should not affect the PCP quality control scores. Some of these kids haven’t been in for 3 years, but still have us listed as PCP |

| • Misalignment of quality measures and practice goals | Measure definitions (for UDS/MU/PCMH) do not always match our quality improvement goals. |

| • Insurance | Some of the insurance companies do not let us remove patients off our panels that do not belong to our practice. |

| • Pediatric primary care under-resourced | While we are PCMH Level 3, PCMH Prime… since 2011, PQRS since 2007 and have over-achieved for MIPS.MACRA we still struggle financially. I wish out work were more valued by insurance companies. |

| We are pediatric primary care so we lack funding for additional programs that would really help families |

Inner setting

Respondents felt that strategies that increased access to care enhance quality of care. These included offering co-located specialty services and evening appointments. Factors cited as decreasing continuity and decreasing quality of care included freestanding urgent care centers and providers seeing patients at multiple practice sites.

Good communication between staff and providers, respect, and working well as a team were inner setting factors identified as important for providing high quality care. Practice leadership was also felt to be an import inner setting contributor to care quality. Practice leaders’ attitudes towards change, knowledge of and commitment to QI, willingness to educate staff about QI strategies, and designating a quality champion were all felt to impact a practice’s quality of care. One respondent felt that having leaders view mistakes as “teachable moments” meant that the practice learned from mistakes rather than being afraid to discuss and fix system-issues that contributed to them. Another respondent felt that a leader’s antagonistic relationship with insurance companies was a barrier to providing the best quality of care.

A culture of patient-centered care was also felt to lead to better quality of care Listening to patients, engaging families in care, treating patients like they were part of one’s family, and believing that all parents’ concerns are legitimate and should be treated as such were considered important factors contributing to high quality of care by several respondents. Outer Setting

Respondents described financial and time-related barriers to providing the highest quality of care. Specific issues cited included the time it takes to hire staff and credential providers; time spent on administrative issues related to reimbursement from healthcare insurance companies (e.g., prior authorizations); and the negative impact of productivity-based provider salaries (e.g., insufficient time during visits to address needs of complex patients). Some respondents felt that “patients’ behavior” could present a barrier to providing high quality of care. Reasons for this included not having their insurance updated before coming to a visit, not being aware of their insurance responsibilities, and not scheduling or coming in for visits when requested, particularly patients over the age of 18. Other external setting barriers included the perception that pediatric primary care is undervalued and under-resourced compared to specialty care, that the quality measures pediatric practices are required to report on do not align with practices’ quality goals, and that insurance companies do not allow practices to remove patients from their panels who are not part of the practice, resulting in being held accountable for patients who are not seen in the practice. Finally, the electronic health record (EHR) was perceived to be a barrier to providing high-quality of care by some respondents. Examples given included feeling that the EHR does not facilitate reporting on quality measures; that providers were slowed down by use of an EHR; and that the EHR makes clinical care more difficult.

Outer Setting

Respondents described financial and time-related barriers to providing the highest quality of care. Specific issues cited included the time it takes to hire staff and credential providers; time spent on administrative issues related to reimbursement from healthcare insurance companies (e.g., prior authorizations); and the negative impact of productivity-based provider salaries (e.g., insufficient time during visits to address needs of complex patients). Some respondents felt that “patients’ behavior” could present a barrier to providing high quality of care. Reasons for this included not having their insurance updated before coming to a visit, not being aware of their insurance responsibilities, and not scheduling or coming in for visits when requested, particularly patients over the age of 18. Other external setting barriers included the perception that pediatric primary care is undervalued and under-resourced compared to specialty care, that the quality measures pediatric practices are required to report on do not align with practices’ quality goals, and that insurance companies do not allow practices to remove patients from their panels who are not part of the practice, resulting in being held accountable for patients who are not seen in the practice. Finally, the electronic health record (EHR) was perceived to be a barrier to providing high-quality of care by some respondents. Examples given included feeling that the EHR does not facilitate reporting on quality measures; that providers were slowed down by use of an EHR; and that the EHR makes clinical care more difficult.

Discussion

This study identified organizational structures, strategies, and contextual factors associated with higher performance on both CQ and PE measures in pediatric primary care practices in Massachusetts as well as pediatric practice respondents’ perceptions of facilitators and barriers to providing high quality care. Some factors identified were potentially modifiable, such as offering co-located ancillary services (e.g., behavioral health), designating a quality champion, and creating an organizational culture in which staff believe that families and patients feel respected.

Being a privately-owned practice was the only factor that was statistically associated with both higher CQ and PE scores. Privately-owned practices in this sample differed from non-privately-owned practices in both the number of providers in the practice and the percentage of patients insured by Medicaid, factors which may contribute to the differences in performance observed. Additional studies powered to conduct multivariable analyses to further explore this association are warranted.

A number of factors that were either statistically associated with performance on quality measures or demonstrated a trend towards a statistically significant association were related to the CFIR Inner Setting constructs “culture” and “learning climate”. Although the questionnaire did not measure “burnout” per se, we asked respondents whether they felt they had control over their time, which relates to burnout (Linzer et al., 2015). Practices in which people felt they had more control had higher PE scores, which supports the relationship between employee burnout and patient care (Dewa, Loong, Bonato, & Trojanowski, 2017).

There was an inverse relationship between the estimated percentage of patients with public health insurance in a practice, an indicator for lower socioeconomic status, and performance on CQ measures in the current study. This may not be surprising since disparities in care are largely experienced by lower-income and racial/ethnic minority children (Dougherty, Chen, Gray, & Simon, 2014). Prior research has suggested that some healthcare providers may believe that caring for a lower-income population can result in worse quality scores due to factors beyond providers’ control (Goff et al., 2015; Lindenauer et al., 2014), a perception shared by some respondents in the current study. This raises two important considerations: whether risk-adjustment strategies should take social determinants of health into account when measuring pediatric ambulatory quality of care and whether the healthcare system provides adequate resources for practices caring for children impacted negatively by social determinants of health.

Some of the responses to open-ended questions contradicted the empiric associations found between certain organizational strategies and contextual factors. For example, early studies of the impact of EHRs and quality of care were equivocal or found EHRs were not associated with improvement (Romano & Stafford, 2011), but a recent review indicated that EHRs are associated with greater efficiency and quality when there is a comprehensive approach to EHR implementation (Campanella et al., 2016). However, a number of respondents commented that they felt that the EHR hindered quality. Additional research is needed to better understand this discrepancy between “evidence” and perceptions and how this discrepancy may impact care.

This study’s results should be considered in light of its limitations. First, each practice was asked to submit one response to the survey; other individuals in the practice may have offered different perspectives. Second, few respondents “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with Likert-style questions, leaving a relatively limited response distribution for these questions. Third, social desirability bias may have impacted responses. Fourth, the nature of the data on practices’ performance on quality measures presented several limitations. Performance scores were not available for all practices, CQ data were not available from public health insurers, and MHQP’s Consumer Reports style of reporting performance restricted the range of scores. This meant that, although we were able to determine whether a practice’s scores were higher than expected, the strength of the associations between a given organizational structure, strategy, or contextual factor and performance was more difficult to ascertain. Our use of average CQ and PE scores to rank practices’ performance weighted all of the individual quality items equally, which might not be appropriate in a general pediatric population. Also, practices that know their performance sores are reported on the MHQP website may be more attuned to quality improvement. Fifth, the study was underpowered for multivariable analyses, limiting the quantitative analysis and making it difficult to make strong recommendations for practices to follow and, lastly, although performance on quality measures is a common approach to measuring quality of care, other unmeasured factors contribute to quality, which may relate to the finding that some respondents perceptions of what contributed to high quality scores differed from both the findings of this study and the literature on organizational characteristics and quality improvement.

Practice Implications

The results of this study suggest that pediatric primary care practices seeking to improve the quality of care they provide might consider offering co-located services in their practice, designating a quality champion, and ensuring good communication practices throughout the organization. A number of contextual factors related to teamwork, respect, and feeling valued approached significance in the quantitative analysis and appeared in respondent’s comments. Incivility and rudeness are known to negatively impact patient care (Flin, 2010; Riskin et al., 2015), but practices may want to explore the relationship between civility, respect, and compassion and performance on quality measures. Finally, although it was beyond the scope of this study, understanding the interrelationships of multiple levels of organizations, such as inner and outer setting elements, are likely critical to not only understand variation in quality of care, but to ensure all children receive the highest quality of care possible.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a NICHD Career Development Award K23 HD080870 (Dr. Goff) and NHLBI Mid-Career Development Award K24 HL132008 (Dr. Lindenauer)

MHQP Benchmarks and Performance Categories for Public Reporting

MHQP publicly reports clinical quality practice site results on its Healthcare Compass (www.healthcarecompassma.org) website. MHQP convened a multi-stakeholder Quality Performance Benchmark Workgroup which included physicians, patients, representatives from health plans, and statistical experts to review options and advise MHQP about setting performance levels and communicating about performance in our public reporting. Based on a review of performance data and considering recommendations from our statistical consultant and advice from the workgroup recommended for each clinical quality measure, MHQP use one of two methods to ensure a minimum level of statistical reliability is reached for publicly reporting site results and for establishing benchmarks for comparative purposes. The choice of which method to apply is based on the distribution and the volume of patients and providers represented in the data.

Beta-Binomial Method

To create three performance categories based on relative performance, two benchmarks, based on the 20th and 80th beta-binomial percentiles of performance, were established for measures demonstrating relatively wide variation and with sufficient data to detect true differences in performance. The beta-binomial fits performance data to a theoretical model that has been shown to describe the true distribution of performance scores, reducing error. Therefore, the beta-binomial distribution of scores can be used to identify performance benchmarks that are expected to remain stable over time. These relative performance levels differentiate those practices that are truly higher or lower in performance than those practices in the middle range of performance. This method is most applicable when there is ample measurement data available and when there is variation in performance, not with limited variation in performance. The pediatric measures employing the beta-binomial benchmarks are: Chlamydia Screening (Ages 16–20) and Well Care Adolescent Visits (Ages 12–21).

Modified Hochberg Method

When performance is high or low across almost all practices for a given measure, it is difficult to distinguish levels of performance among practices. Therefore, an alternative method of performance classification is needed. In these cases MHQP applied a modified version of the Hochberg method. The Hochberg method essentially defines performance level by comparing practice performance to the median. Practice scores are evaluated to determine whether they are statistically similar to or different from the median practice score. Benchmarks are defined by determining the exact point at which a practice with sufficient sample size would be significantly lower than or higher than the median.

To calculate performance benchmarks for this Clinical Quality report, when performance was high or low across almost all practices for a given measure, MHQP used a modification of the Hochberg method which uses only one benchmark instead of two. When performance is consistently high across practices, practices in the middle and high performance categories are moved into the high performance category. Similarly, when performance is consistently low across practices, practices in the middle and high performance categories are moved into the middle performance category. Methodologically, those practices falling into the recalibrated lowest performance level reported are still truly different from the majority of practices being reported. MHQP adjusted the modified Hochberg method for a few measures, when practice rates did not differ from the median in a statistically significant way, even though care provided was clearly superior (i.e. the performance rate was at or above the beta binomial 99th percentile). In these cases, MHQP put the practice result in the high performance category and included a high performance designation (see section below). This decision is based upon the clinical relevance of these practices providing the desired service most of the time and MHQP’s intent to produce maximally useful and meaningful quality information for consumers.

The pediatric measures employing the modified Hochberg method are: Appropriate Asthma Medication Use (Ages 5–11 & Ages 12–50); Appropriate Asthma Medication Use; Appropriate Testing for Children with Pharyngitis; Appropriate Treatment for Children with URI; and Well Infant (First 15 months of life), Well Child (Ages 3–6).

Misclassification Risk and Buffer Zones

MHQP’s public reporting establishes performance categories so that meaningful differences in performance among practices are represented. The number of performance categories is limited in order to highlight differences and reduce the chance that a practice could be misclassified in a category that is lower than it should be. For measures using beta-binomial performance benchmarks, MHQP also defines a one point buffer zone around each performance cut-point to further reduce the possibility of incorrectly categorizing a practice in a lower category. The Hochberg method protects against misclassification through a statistical process reducing the chance of error.

Top Performance Designation

MHQP has identified practices achieving the highest or “top” level of performance in private and public reporting. Practices reaching this level of performance were identified using the beta-binomial method described above. Practices achieving “Top Performance” are at or above the 99th percentile of the beta-binomial distribution for a given measure. The beta-binomial 99th percentile can be used to set achievable goals for quality improvement for existing measures which have had stable results over time.

Contributor Information

Sarah L. Goff, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School - Baystate; Institute of Healthcare Delivery and Population Health Science.

Kathleen M. Mazor, Meyers Primary Care Institute; Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School - Worcester.

Aruna Priya, Biostatistics Core; Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science; University of Massachusetts Medical School - Baystate.

Michael Moran, Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science; University of Massachusetts Medical School - Baystate.

Penelope S. Pekow, Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science, University of Massachusetts Medical School - Baystate; School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts - Amherst.

Peter K. Lindenauer, Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate; Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School – Worcester.

References

- Aysola J, Bitton A, Zaslavsky AM, & Ayanian JZ (2013). Quality and equity of primary care with patient-centered medical homes: results from a national survey. Medical Care, 51(1), 68–77. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318270bb0d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, Seid M, Armstrong G, Opipari-Arrigan L, & Hartung H (2016). Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(7), 509–517. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordley WC, Margolis PA, Stuart J, Lannon C, & Keyes L (2001). Improving preventive service delivery through office systems. Pediatrics, 108(3), E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, & Krumholz HM (2009). Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implementation Science : IS, 4, 25. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella P, Lovato E, Marone C, Fallacara L, Mancuso A, Ricciardi W, & Specchia ML (2016). The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 26(1), 60–64. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien AT, Kuhlthau KA, Toomey SL, Quinn JA, Okumura MJ, Kuo DZ, … Schuster MA (2017). Quality of Primary Care for Children With Disabilities Enrolled in Medicaid. Academic Pediatrics, 17(4), 443–449. 10.1016/j.acap.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang E, Cabrera C, Mak S, Glenn B, Hochman M, & Bastani R (2017). Primary care team- and clinic level factors affecting HPV vaccine uptake. Vaccine, 35(35 Pt B), 4540–4547. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Windon A, Moreno C, Schuster MA, & Chung PJ (2013). Well-child care clinical practice redesign for young children: a systematic review of strategies and tools. Pediatrics, 131 Suppl 1, S5–25. 10.1542/peds.2012-1427c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science: IS, 4, 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, & Trojanowski L (2017). The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 7(6), e015141. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA (2011). Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method -- 2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty D, Chen X, Gray DT, & Simon AE (2014). Child and adolescent health care quality and disparities: are we making progress? Academic Pediatrics, 14(2), 137–148. 10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flin R (2010). Rudeness at work. BMJ, 340, c2480. 10.1136/bmj.c2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SL, Lagu T, Pekow PS, Hannon NS, Hinchey KL, Jackowitz TA, … Lindenauer PK (2015). A qualitative analysis of hospital leaders’ opinions about publicly reported measures of health care quality. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 41(4), 169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Compass MA. (n.d.). Retrieved January 1, 2019, from http://www.healthcarecompassma.org/

- Hsieh H-F, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton R, Taylor N, Clay-Williams R, & Braithwaite J (2014). Positive deviance: a different approach to achieving patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(11), 880–883. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Ross JS, Pekow PS, Shatz A, Hannon N, … Benjamin EM (2014). Attitudes of Hospital Leaders Toward Publicly Reported Measures of Health Care Quality. JAMA Internal Medicine. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, Varkey A, Yale S, Williams E, … Barbouche M (2015). A Cluster Randomized Trial of Interventions to Improve Work Conditions and Clinician Burnout in Primary Care: Results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(8), 1105–1111. 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, Keesey J, Klein DJ, Adams JL, … McGlynn EA (2007). The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(15), 1515–1523. 10.1056/NEJMsa064637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Health Quality Partners. (2013, September 24). Retrieved September 24, 2013, from http://www.mhqp.org/default.asp?nav=010000

- McAllister JW, Cooley WC, Van Cleave J, Boudreau AA, & Kuhlthau K (2013). Medical home transformation in pediatric primary care--what drives change? Annals of Family Medicine, 11 Suppl 1, S90–98. 10.1370/afm.1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCQA > HEDIS & Quality Measurement. (2013, October 1). Retrieved October 1, 2013, from http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx

- Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, Kugelman A, Gover A, Shoris I, … Bamberger PA (2015). The Impact of Rudeness on Medical Team Performance: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics, peds.2015–1385. 10.1542/peds.2015-1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano MJ, & Stafford RS (2011). Electronic Health Records and Clinical Decision Support Systems: Impact on National Ambulatory Care Quality. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(10), 897–903. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subar AF, Thompson FE, Smith AF, Jobe JB, Ziegler RG, Potischman N, … Harlan LC (1995). Improving Food Frequency Questionnaires: A Qualitative Approach Using Cognitive Interviewing. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 95(7), 781–788. 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00217-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartak SC (n.d.). Association between organizational factors and quality of care: an examination of hospital performance indicators, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn TE, McCoy KD, BootsMiller BJ, Woolson RF, Sorofman B, Tripp-Reimer T, … Doebbeling BN (2002). Organizational predictors of adherence to ambulatory care screening guidelines. Medical Care, 40(12), 1172–1185. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000036430.59183.7F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West E (2000). Organisational sources of safety and danger: sociological contributions to the study of adverse events. Quality in Health Care: QHC, 9(2), 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]