Abstract

The TNF superfamily ligands BAFF and APRIL interact with three receptors, BAFFR, BCMA and TACI, to play discrete and crucial roles in regulating B cell selection and homeostasis in mammals. The interactions between these ligands and receptors are both specific and redundant: BAFFR binds BAFF, while BCMA and TACI bind to either BAFF or APRIL. In a previous phylogenetic inquiry we identified and characterized a BAFF-like gene in lampreys, which with hagfish are the only extant jawless vertebrates, both of which have B-like and T-like lymphocytes. To gain insight into lymphocyte regulation in jawless vertebrates, here we identified two BCMA-like genes in lampreys, BCMAL1 and BCMAL2, which were found to be preferentially expressed by B-like lymphocytes. In vitro analyses indicated that the lamprey BAFF-like protein can bind to a BCMA-like receptor Ig fusion protein and to both BCMAL1- and BCMAL2-transfected cells. Discriminating regulatory roles for the two BCMA-like molecules are suggested by their differential expression before and after activation of the B-like lymphocytes in lampreys. Our composite results imply that BAFF-based mechanisms for B cell regulation evolved before the divergence of jawed and jawless vertebrates.

Introduction

Members of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily (TNFSF) and their receptors (TNFSFR) orchestrate a wide range of immune system functions and other biological processes in mammals. The closely related TNF superfamily (TNFSF) ligands, B-cell activating factor (BAFF, a.k.a BLyS and TNFSF13b) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL, TNFSF13) are key regulators of B lymphocyte activation, selection and survival (Reviewed in (1, 2)). BAFF and APRIL influence B cells at various stages of differentiation via interaction with three different receptors (3-6). Both BAFF and APRIL bind to the BCMA (B cell maturation antigen) and TACI (transmembrane activator and CAML interactor) cell surface receptors (7); BAFF also binds uniquely to the BAFF receptor (BAFFR, a.k.a BR3), another TNFSFR family member (6, 8-10). Whereas BAFF binds more avidly to BAFFR, APRIL has higher binding affinities for BCMA and TACI (Reviewed in (11)). The cellular expression patterns of BAFFR, BCMA and TACI also differ; BAFFR and TACI are both expressed on pre-immune B cells and are differentially downregulated during activation and plasma cell differentiation, whereas BCMA is expressed solely among plasma cells (12). BAFFR interactions with BAFF mediate the survival of pre-immune B cells, and thus regulate the steady state numbers of these populations in mammals (13).

The extant jawless vertebrates (agnatha), lampreys and hagfish, have an alternative adaptive immune system featuring B-like and T-like lymphocytes, but they use entirely different types of receptors for antigen recognition (14-18). Instead of the immunoglobulin domain-based B cell receptors (BCRs) and T cell receptors (TCRαβ and TCRγδ) that jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes) use, the jawless vertebrates use three types of variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRA, VLRB and VLRC) containing leucine-rich-repeat (LRR) sequences for antigen recognition (14, 15, 19-26). VLRB is expressed by B-like lymphocytes, whereas VLRA and VLRC are expressed by T-like lymphocytes with characteristics akin to the TCRαβ and TCRγδ populations of T cells in jawed vertebrates (18, 26, 27).

In a prior phylogenetic analysis of TNFSF members, we identified a lamprey BAFF-like gene and demonstrated its expression by T-like, B-like and innate immune cells of this ancient jawless vertebrate representative (28). The lamprey BAFF-like protein exhibits amino acid sequence and surface electric charge similarities with both BAFF and APRIL (28, 29). Here, we have identified and characterized two lamprey TNFSFR genes that have sequence similarity to mammalian BCMA. The two BCMA-like genes are predominantly expressed by VLRB+ B cell-like lymphocytes and both can bind the lamprey BAFF-like molecule. Our findings indicate that this set of ligands and receptors had already evolved in a common ancestor of jawed and jawless vertebrates, and suggests they play regulatory roles for VLRB+ B cell-like lymphocytes.

Materials and methods

Cloning

Lamprey BAFF-associated receptors (BCMAL1 and BCMAL2) were found by a TBLASTN search of the Petromyzon marinus (sea lamprey, genome assembly Pmarinus_7.0) and Lethenteron japonicum (Japanese lamprey, genome assembly LetJap1.0) genome sequences. Retrieved sequences from Japanese lamprey were used primarily for sequence comparison. Sea lamprey was used as a source of cDNA and was the species in which gene expression was analyzed. For the amplification, the following primers were used with KOD polymerase (TOYOBO): (i) BCMAL1, Pm BCMAL1-F; ATGGAGACGTCTCGGGAGCCGGC and Pm BCMAL1-R; TCACCCTACAACAAGCTCAGATGGGCCTT; (ii) BCMAL2, Pm BCMAL2-F; ATGACCTCGCACTGCCCGGCT and Pm BCMAL2-R; TCAAGTGTAGTTTGTGACCATTTGCGAAG. After adding adenine to the 3’-ends, the amplified DNA was ligated into the pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega).

Phylogenetic and bioinformatics analyses

Full-length amino acid sequences of BAFFR, BCMA and TACI from human (NP_443177, CAA82690 and NP_036584) and mouse (NP_082351, XP_006522052 and NP_067324) were downloaded from the NCBI database. In order to retrieve their orthologous sequences in other vertebrate and invertebrate chordate species, we performed TBLASTN search for matches with E-value less than 10−5 against genome sequence databases as well as cDNA databases (when available) from ENSEMBL (http://useast.ensembl.org/index.html), and NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The hypothetical translations of retrieved sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE and ClustalW programs (30, 31). Signal peptide cleavage sites were predicted with SignalP 4.0 (32). Protein domain prediction was performed using the SMART database (33).

After sequences were aligned and configured for highest accuracy, phylogenetic trees were constructed by neighbor-joining and maximum likelihood methods, implemented in MEGA5.0 (34, 35). The evolutionary distances were computed by the JTT matrix-based method (36). Reliability of internal branches was evaluated using the bootstrapping method (1000 bootstrap replicates).

Homology modeling

The quaternary structures of sea lamprey BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 were modelled by SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/), based on the crystal structure of human BCMA (PDB no. 4zfo) as a modeling template. The electrostatic potential was calculated by the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver (APBS) in CueMol2 (http://www.cuemol.org/en/). The percent identity at particular amino acid sites was calculated by Jalview (37).

Sorting of VLRA+, VLRB+, VLRC+ and VLR negative lymphocytes

Leukocyte isolation from blood and tissues and staining for flow cytometry was conducted as described (18). Briefly, leukocytes from blood and tissues were stained with anti-VLRA rabbit polyclonal serum (R110), anti-VLRB mouse monoclonal antibody (4C4) and biotinylated anti-VLRC mouse monoclonal antibodies (3A5) and with matched secondary reagents. Staining and washes were in 0.67× PBS with 1% BSA. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). VLRA+, VLRB+, VLRC+ and VLR triple-negative (TN) cells in the lymphocyte gate were sorted on BD FACS Aria II (BD Bioscience) for quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The purity of the sorted cells was > 95%. Lampreys were injected intra-coelomically with 25 μg phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-L (Sigma) as described previously (17, 18).

Expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs from tissues (skin, kidneys, intestine, gills and blood) from lamprey larvae and purified VLRA+, VLRB+, VLRC+ and TN lymphocytes were extracted using RNeasy kits with on-column DNA digestion by DNase I (QIAGEN). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with random hexamer primers by Superscript III (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using SYBR Green on a 7900HT ABI Prism thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. The values for both BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 genes were normalized to the expression of β-Actin.

Transfection

293T cells were cultured in DMEM (sigma) containing 5% FBS at 37° C and 5% CO2. Lamprey BAFF-like (BAFFL) ligand and human ectodysplasin A was ligated into the pDisplay vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific), fused with N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag (pDisplay-HA-BAFFL and pDisplay-HA-hEDA). Lamprey BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 receptors are also ligated into the pDisplay vector, fused with N-terminal FLAG-tag (pDisplay-FLAG-BCMAL1 and pDisplay-FLAG-BCMAL2). The extracellular domain of lamprey BCMAL-receptors were also fused with human IgG Fc-tag at the C-terminal, and ligated in pIRES puro vector (pIRES puro-FLAG-BCMAL1-Fc and pIRES puro-FLAG-BCMAL2-Fc). The expression vectors were transfected to 293T cells using polyethylenimine (PEI). After three days incubation, the culture medium and transfected cells were harvested for further assay.

Protein analysis by gel electrophoresis

The procedure of Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) was described previously (38). Briefly, the culture medium of pDisplay-HA-BAFFL transfected 293T cells was mixed with 5% glycerol and 0.01% Ponceau S, then applied on 10% native PAGE gel. Mouse IgG (~160kDa), bovine serum albumin (BSA, 66kDa) and ovalbumin (OVA, 43 kDa) were electrophoresed as size markers. The separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by conventional semi-dry blotting. The HA-tagged lamprey BAFF-like protein was reacted with mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (clone 2-2.2.14, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After washing with PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20), the blot was reacted with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugating goat anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotech). After washing with PBST, the HA-BAFFL was detected using SuperSignal West Pico (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on an Image station 4000 MM pro (Kodak).

Flow cytometry

To detect ligand-receptor interaction, 293T cells transfected with the pDisplay-FLAG-BCMAL receptor construct were incubated with HA-BAFFL containing DMEM for 30 minutes. After washing with PBS, the cells were reacted with a rabbit anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody (Sigma) and a mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (clone 2-2.2.14, Thermo Fisher Scientific). PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Southern biotech) and Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for detection. The stained cells were analyzed using a BD Accuri C6 cytometer and Cytobank (https://community.cytobank.org/).

Immunoprecipitation

The secreted HA-BAFFL protein and BCMAL-Fc proteins from transfected 293T cells were purified using anti-HA agarose (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE healthcare) following the manufactures protocol. 1μg of purified receptor and ligand proteins were incubated at 4°C in 100μl PBS with gently mixing overnight. 30 μl of protein G slurry was added and then incubated for an hour at 4°C with gentle mixing. After washing the protein G beads with PBS, the proteins were denatured with 2 × SDS-sample buffer 0.1M tris-HCL (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 12% beta-mercaptoethanol and bromophenol blue. The protocols for SDS-PAGE and western blotting were described previously (39). The antibodies for detecting HA-BAFFL proteins were the same as those used for western blotting after BN-PAGE. The secreted HA-BAFFL, HA-hEDA and FLAG-BCMAL-Fc proteins from transfected 293T cells were also mixed with anti-HA agarose (Pierce) for pull-down assay.

Results

Identification of two BCMA-like genes in lampreys

When human and mouse BAFFR, BCMA and TACI amino acid sequences were used in a similarity search against sea lamprey and Japanese lamprey genomic sequences, we found two significant partial matches in each lamprey species. By extension of the complementary hit regions in the genome sequences, we could identify two potential open reading frames using the hypothetical translation of retrieved genomic sequences in both the sea lamprey and Japanese lamprey. The two predicted BAFF-interacting TNFSFR homologs in sea lamprey were cloned and sequenced from blood cell cDNA. These two genes, sequence1 and sequence2, which are found in the same scaffold (PIZI01000003.1) of the reference sea lamprey genome, face in head to head transcriptional directions and encode proteins of 179 aa and 152 aa, respectively. Whereas the putative BAFF-interactive TNFSFR members in sea lamprey exhibit only ~40% aa sequence similarity with each other, sequence1 and sequence2 exhibit 89% and 96% similarity with their orthologous Japanese lamprey counterparts, respectively.

When we conducted a comprehensive sequence comparison of this pair of BAFF-interactive TNFSFR homologous sequences in lampreys with currently identified BAFFR, BCMA and TACI sequences of representative jawed vertebrate species, using neighbor joining (NJ) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods, the resultant tree topologies were found to be very similar (Fig1 and Fig S1). Two major clusters are evident in both trees. All of the TACI sequences form one phylogenetic cluster, while the BAFFR, BCMA, and lamprey TNFSFR homologs are in the other cluster. In the latter cluster, BAFFR sequences are separated from heterogeneous BCMA sequences and the lamprey TNFSFR homologs are closest to BCMA, although the bootstrap support is low (Fig1 and Fig S1). We therefore designate sequence1 as BCMA-like1 (BCMAL1) and sequence2 as BCMA-like2 (BCMAL2). In this phylogenetic analysis, we also identified orthologs of mammalian BAFFR, BCMA and TACI in the elephant shark genome sequence. Note that the phylogenetic trees are rooted with the closely related ectodysplasin A receptor (EDAR) sequences, which like the TACI sequences contain multiple cysteine-rich domains (CRDs).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship among BAFF-interactive receptors. The Phylogenetic tree is constructed by the Neighbor joining method. BCMA-like sequences in lampreys and BAFFR, BCMA and TACI sequences in elephant shark are highlighted in bold letters. Bootstrap supports in interior branches are shown. The tree is rooted by ectodysplasin A receptor sequences from vase tunicates (Ciona intestinalis) and elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii). A cartoon depicting receptor-ligand interactions in mammals is shown in the lower right corner.

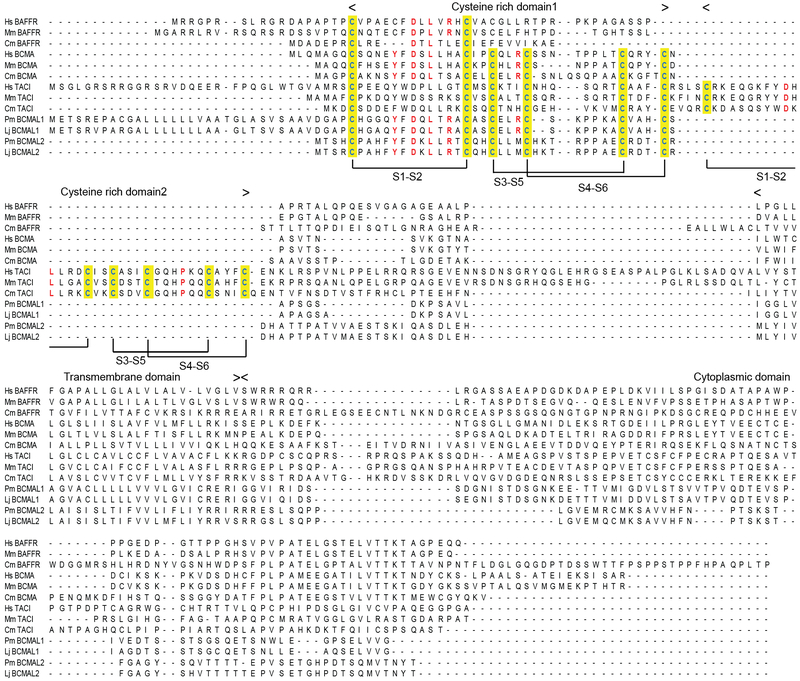

Among the three types of BAFF-interactive receptors, the TACI sequences in jawed vertebrates contain two complete CRDs, whereas BCMA sequences contain only one complete CRD (Fig.2, Fig.S2A and S2B). Each CRD domain of TACI and BCMA contains six conserved cysteine residues, which could allow formation of three disulfide bonds. In contrast, BAFFR sequences contain a partial CRD that could allow a single disulfide bond (Fig.2 and Fig.S2C). Like the BCMA sequences in jawed vertebrates, the BAFF-interactive TNFSFR homologous sequences in both sea lamprey and Japanese lamprey possess one complete CRD with six cysteine residues, which potentially could contribute to three disulfide bonds (Fig.2). In mammalian BCMA, a tyrosine (Y13 in human), an aspartic acid (D15 in human) and a leucine (L17 in human), are located between the 1st and 2nd cysteine residues of the CRD, and these participate in BAFF and APRIL binding (11). Notably, those residues are also conserved in the lamprey BCMA-like sequences, BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 (Fig.2). Additionally, both sea lamprey and Japanese lamprey BCMAL1 sequences have a conserved leucine (L26 in humans) and arginine (R27 in humans) immediately upstream of the 4th cysteine residue in the CRD (Fig.2), which favors APRIL binding in mammals (40).

Figure 2.

Alignment of BAFF-interacting receptors. The location of cysteine-rich domains (CRD1 and CRD2), transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic domain are shown above the alignment. Conserved cysteine residues in CRD1 and CRD2 are highlighted in yellow and residues involved in mammalian BAFF and/or APRIL binding are shown in red color. The formation of predicted disulfide bonds (S1-S2, S3-S5, and S4-S6) are indicated by brackets. Hs, Homo sapiens (Human); Mm, Mus Musculus (Mouse); Cm, Callorhinchus milii (Shark); Pm, Petromyzon marinus (Sea lamprey); Lj, Lethenteron japonicum (Japanese lamprey).

The sequence identity of BAFFR, BCMA and TACI is relatively high in their cysteine-rich domains, transmembrane domains and a short stretch of the TRAF-binding region located close to the C-terminus. Members of the TNF receptor associated factor (TRAF) family of signaling adaptor proteins participate in downstream signaling via a consensus TRAF-binding motif (11, 41, 42). A putative TRAF-binding motif PVQDT which is homologous to the experimentally determined TRAF-binding motif present in human CD40 (PVQET), mouse Cardif (PVQDT) and human OX40 (PIQEE) was identified in the cytoplasmic domains of the lamprey BCMAL1 (Fig.3A). However, a slightly diverged homologous sequence PVSET, where the consensus glutamine residue (amide group containing polar amino acid) was substituted by the hydroxyl group containing polar amino acid serine was found in the C-terminal region of lamprey BCMAL2 (Fig. 3A). In the human BCMA and BAFFR, the glutamine residue is also substituted by methionine and proline, respectively. Among the TRAF family members, TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, and TRAF5 interact with similar motifs within the cytoplasmic region of the receptors (a major consensus sequence (P/S/A/T)x(Q/E)E, where × is any amino acid) (41-43). In some instances, atypical TRAF-binding motifs are also found (44, 45). For example, the atypical TRAF-binding motif (PVPAT) of BAFFR specifically interacts with TRAF3, but the modification of PVPAT to the TRAF-binding PVQET motif of CD40 allows the modified BAFFR to interact with both TRAF2 and TRAF3 (44, 45). When we searched for TRAFs in sea lamprey and Japanese lamprey genome sequences using query sequences of human TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, TRAF4, TRAF5 and TRAF6 (accession numbers: NP_005649, NP_066961, NP_663777, NP_004286, NP_001306136, and NP_004611) and a hagfish TRAF3 (accession number: BAG85182), we found two TRAF3 homologs (TRAF3a and TRAF3b) and a TRAF6 homolog in both lamprey species (Fig. 3B). In the sea lamprey genome TRAF3a, TRAF3b and TRAF6 are located in scaffolds PIZI01000029.1, PIZI01000036.1 and PIZI01000002.1, respectively. In the Japanese lamprey they are also distributed in three different scaffolds (Scaffold KE993941, KE993702 and KE993865). There is ~63% sequence similarity between these two TRAF3 homologs in lampreys. The differences in the putative TRAF-binding motifs in lamprey BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 and the presence of multiple TRAFs in lampreys opens the possibility that BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 have different signaling functions through the interaction with different TRAFs.

Figure 3.

TRAFs and potential TRAF-binding motifs in lamprey BCMAL1 and BCMAL2. (A) Putative TRAF-binding motif in the cytoplasmic domain of BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 in lampreys. The typical consensus TRAF-binding motif is shown in dark color shades and the substitution with similar amino acids is shown in lighter shades. As modes of interaction between TRAF family members and TNF receptors have been well studied for TRAF2 and TRAF3, we used TRAF2- and TRAF3-binding motifs as representatives (shown in bold letters, PDB ID is given). Position of amino acid residues are shown in parenthesis. Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Pm, Petromyzon marinus; Lj, Lethenteron japonicum. (B) Phylogenetic relationship of human, mouse, hagfish and lamprey TRAFS. The unrooted phylogenetic tree is constructed by Neighbor joining method. Bootstrap supports in all branches are shown.

We could not find BAFFR, BCMA and TACI homologs in the reference genomes of the lower chordate representatives, vase tunicate (Ciona intestinalis), colonial star tunicate (Botryllus schlosseri) and amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae). Previously, we reported that BAFF and APRIL homologs are absent in invertebrate chordates (28). Altogether, our observations are consistent with the conjecture that the homologs of BAFF and BAFF-interacting receptors co-evolved in vertebrates.

Homology modelling of lamprey BCMA-like receptors

In order to evaluate the concordance and divergence in the 3D structures for the BCMA-like proteins in lampreys and BAFF-interacting proteins in humans, we conducted homology modelling. When we estimated surface electrostatic charge by APBS, charged residues were accumulated around the ligand binding surface in human BAFF-R and TACI. On the other hand, human BCMA has only relatively moderate charges on the ligand binding surface (Fig.4). We constructed 3D models of the lamprey BCMA-like receptors to estimate the surface electrostatic charge. The surface charge distributions predicted by these models suggest that both lamprey BCMA-like receptors have relatively moderate charge on the surface corresponding to the ligand binding site in the human BAFF receptors. The sequence comparison in the ligand recognition site suggests that lamprey BCMA-like receptors have conserved features that could favor designation as either BAFF or APRIL types of ligands (Fig.S3). Both lamprey BCMA-like receptors have a tyrosine corresponding to the Tyr13 residue in human BCMA, which is required to bind mammalian APRIL. On the other hand, the lamprey BCMA-like receptors retain the conserved Arg30 residue found in human BAFFR that preferentially binds mammalian BAFF. The lamprey BCMAL2 shares a hydrophobic residue (Met) in the corresponding site for Leu38 in human BAFFR, which preferentially binds BAFF rather than APRIL (40). In our previous study, we noted that the lamprey BAFF-like protein possesses important amino acid similarities to both mammalian BAFF and APRIL (28). These conserved features suggest that both BCMA-like proteins could interact with the lamprey BAFF-like protein.

Figure 4.

The protein structure and surface electrostatic potential of BAFF-related receptors. The structures for two lamprey BCMA-like receptors, BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 were predicted by SWISS-MODEL, based on the crystal structure of human BCMA (PDB: 4zfo). The blue and red colors represent positive and negative surface electrostatic potential, respectively. Yellow arrowhead indicates the ligand binding site.

Receptor-ligand interaction

To examine the potential for ligand-receptor interactions between the lamprey BAFF-like protein and BCMA-like receptors, a flow cytometry analysis was performed using purified soluble lamprey BAFF-like protein and recombinant forms of the two lamprey BCMA-like receptors which were expressed on 293T cells. The soluble BAFF-like protein was bound by BCMAL1- or BCMAL2-expressing 293T cells, thereby indicating that BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 can each bind the lamprey BAFF-like protein (Fig.5). Immunoprecipitation analysis was also performed using the recombinant BAFF-like protein and soluble recombinant forms of the two BCMA-like receptors. The size of the recombinant HA-tagged BAFF-like proteins was estimated in native PAGE to be ~78 kDa, which is about four times the expected monomer size of 18 kDa (Fig.S4). This size shifting could be explained by spontaneous homo-multimer formation of lamprey BAFF-like protein, akin to the homo-trimer formation by human BAFF (46, 47). We confirmed that soluble lamprey BAFF-like protein was co-precipitated by proteins formed by the extracellular domains of the BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 receptor proteins fused with an Ig Fc domain (Fig.S4). We also confirmed that the FLAG-tagged extracellular domains of the BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 receptor proteins were co-precipitated by the lamprey BAFF-like protein, but not by human ectodysplasin A (EDA) (Fig.S4).

Figure 5.

Interaction between the lamprey BCMA-like receptor proteins (BCMAL1 and BCMAL2) and the lamprey BAFF-like (BAFFL) ligand. The purified soluble HA-tagged BAFFL protein was incubated with 293T cells (top right panel) and 293T cell transfects expressing FLAG-BCMAL1 (top left panel) or FLAG-BCMAL2 (top middle panel). Binding was evaluated by flow cytometry. The receptors and the ligand were detected by anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. The data without the HA-BAFFL ligand are shown in the bottom panels. Two flow cytometry experiments were overlaid in each panel (red and black dots). Red set: cells stained with both primary and secondary antibodies. Black set: cells stained with secondary antibody only. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Cellular expression patterns of the lamprey BCMA-like genes

Like the jawed vertebrates, jawless vertebrates have discrete hematopoietic tissues that contain B-like cells (VLRB+), T-like cells (VLRA+ and VLRC+), innate lymphocytes and other types of hematopoietic cells, including thrombocytes, erythroid, monocytic and granulocytic cells (17, 18). Hence, we performed a quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis in order to examine the tissue expression profiles of transcripts encoding the two BCMA-like genes in lampreys. Our qPCR analysis indicated that both BCMA-like genes are highly expressed by circulating white blood cells (WBCs) and to a lesser extent by cells obtained from intestine, gill region and skin tissue samples (Fig.6A). When the different lymphocyte-like populations in lamprey blood and other tissues were examined, preferential expression of both BCMA-like genes was observed for the VLRB+ B cell-like population and to a lesser extent for the VLRA+ and VLRC+ T cell-like populations (Fig.6B). Significant expression of both BCMA-like genes was also observed in the ‘triple-negative’ lymphocyte population. These expression profiles for BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 suggest their potential for contribution to the regulation of B-like cells in lampreys. When the expression profiles of BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 were examined for VLRB+ cells derived from naïve non-stimulated and phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated lampreys, we found that BCMAL1 was preferentially expressed by VLRB+ cells of naïve animals, whereas BCMAL2 was preferentially expressed by PHA-stimulated animals (Fig.6C).

Figure 6.

Expression of two BCMA-like genes in lampreys. (A) Tissue distribution of BCMAL1 and BCMAL2. Relative expression levels of BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 transcripts were determined by real-time PCR analysis of skin, gills, kidneys, intestine, and WBCs of sea lamprey larvae (n = 3 larvae). (B) BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 expression by sorted VLRA+, VLRB+, VLRC+, and triple-negative (TN) lymphocyte populations (n = 3 larvae) in lampreys. (C) The expression of BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 by VLRB+ cells in naïve and PHA-stimulated lampreys (n =3). Relative expression levels of two BCMA-like genes were determined by real-time PCR (mRNA abundance relative to that of β-Actin). Error bars represent mean ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

Lampreys offer an important model organism with links to the early evolution of vertebrates, wherein both B-like and T-like lymphocytes are present (17, 18). In considering the immunological roles of BAFF, APRIL and their receptors in the B-cell arm of the immune system, we examined the available genome sequences of diverse vertebrates, including lamprey and elephant shark; and the invertebrate chordates, amphioxus and tunicates. Previously, we identified and characterized a single BAFF-like gene in lamprey (28). The lamprey BAFF-like protein is a bipolar TNF with both a negatively charged BAFF-like side and a positively charged APRIL-like side (28). Like mammalian BAFF and APRIL this BAFF-like relative is expressed in a wide range of tissues and by a variety of cell types.

In the present study, we identified two BCMA-like receptors in lampreys; BCMAL1 and BCMAL2, and used this information to reconstruct a plausible evolutionary scenario for the emergence of this B cell signaling system. Our in vitro binding assays indicate that both BCMA-like receptors are capable of interaction with the lamprey BAFF-like protein. The search for BAFF or APRIL-like orthologues (28) and BAFFR, BCMA and TACI sequences in invertebrate chordates like vase tunicates (Ciona intestinalis), colonial star tunicate (Botryllus schlosseri) and amphioxus (Branchiostoma floridae) was fruitless. BAFF/APRIL and their cognate receptors thus appear to be vertebrate lineage innovations.

The mammalian BAFFR, BCMA and TACI proteins are type III transmembrane receptors characterized by an extracellular ligand binding site at the N-terminus, a transmembrane domain and the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain that is responsible for intracellular signaling (48). The binding of BAFF or APRIL by these receptors occurs in the fairly conserved cysteine-rich domain (CRD) located within the extracellular region (49). TNF receptors typically have multiple CRDs (50), but BCMA receptors in all of the jawed vertebrates, including the cartilaginous fishes, have only one CRD and the BAFFR family members have only a partial CRD (Fig.2, Fig.S2). On the other hand, the TACI sequences in all jawed vertebrates contain two CRDs (Fig.2, Fig.S2). In humans, the first CRD of TACI has been shown to have a much weaker affinity than the second CRD for BAFF and APRIL binding (40). Even a transcript variant of the human TACI sequence, which lacks the first CRD, binds as efficiently as the native TACI with two CRDs (40). These findings suggest that one CRD is sufficient for interaction with BAFF and APRIL. Like BCMA in jawed vertebrates, both of the BCMA-like receptors in lampreys possess one CRD. Moreover, phylogenetic analyses for whole sequences and the CRDs, as well as homology modelling, support the conclusion that both lamprey receptors are close relatives of the BCMA receptors of jawed vertebrates. Both NJ and ML trees for the entire sequences of BAFF-interacting receptors reveal two main clusters, one of which includes all TACI sequences and the other of which contains BAFFR, BCMA and lamprey BCMA-like sequences (Fig. 1, Fig.S1). In view of the multiple CRDs in other TNF receptors, including the closely related ectodysplasin A receptors, an evolutionary scenario is suggested that a TACI-like organization is ancestral to the BAFF-interacting receptor genes and the evolution of BCMA-like genes involved the loss of one CRD. A parsimonious interpretation is that the common ancestor of jawed and jawless vertebrates should have both TACI-like and BCMA-like genes; a TACI-like gene was lost later in jawless vertebrates and the BAFFR-like gene in jawed vertebrates evolved by gene duplication and further loss of cysteine residues in the single CRD. The presence of two BCMA-like genes in sea lampreys and Japanese lampreys also indicates that a duplication event occurred before the divergence of these two lamprey species. Overall, the evolutionary scenario indicates that CRD loss and degeneration occurred during the evolution of BAFF-interacting receptors.

The cytoplasmic domains of BAFFR, BCMA, and TACI exhibit only a short stretch of similarity, which includes the respective TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF) binding sites (11). Despite poor conservation within the C-terminal region of the two BCMA-like receptors in lampreys, our analysis indicates that both proteins have a putative TRAF binding motif in this region, thereby supporting their role in downstream signaling (Fig. 3). However, these potential TRAF-binding regions differ from each other. Lampreys also possess multiple TRAF genes which may interact differentially with the lamprey BCMA-like proteins. Of note in this regard, mammalian BCMA may bind to several TRAFs (51, 52). These features raise the possibility that there are differences in the downstream signaling pathways for the two lamprey BCMA-like proteins. Parenthetically, we still lack a complete molecular understanding of the signaling events of BAFF-interacting receptors in mammals.

Our evaluation of the two BCMA-like genes in sea lampreys indicates that both have similar expression patterns; they are highly expressed in peripheral blood cells and to a lesser extent in cells derived from the intestine, gills and skin. Among the different lymphocyte populations, both lamprey BCMA-like genes are most highly expressed in the VLRB+ B-cell-like lymphocytes, consistent with the largely B-lineage-skewed expression of BAFFR and BCMA in mammals (53-55). The expression profiles for BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 suggest their equivalent potential for contributing to the regulation of lamprey B-like cells. When we compared their individual expression levels in VLRB+ cells in naïve versus PHA-stimulated lampreys, we found significantly higher expression of BCMAL1 in naïve animals and lower expression in VLRB+ cells of the PHA stimulated animals. The opposite expression pattern was observed for BCMAL2, for which the expression level is increased in VLRB+ cells from the PHA-stimulated animals. This result suggests that BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 could regulate different stages of lamprey B-like cell differentiation, reminiscent of the differential roles of BAFFR and BCMA in naïve versus plasma cells in mammals.

Homology modeling of BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 revealed that both have moderate charge distribution on their putative ligand-binding surfaces and conservation of amino acid residues (Fig.4, Fig.S3) typically involved in the interaction with both BAFF and APRIL (11). Our previous study suggests that the lamprey BAFF-like ligand has both BAFF and APRIL characteristics in terms of conserved amino acids and surface electrostatic charge (28). Our in vitro analysis also indicates that, like mammalian BAFF, the lamprey BAFF-like protein forms homo multimers and can bind with both BCMAL1 and BCMAL2. We hypothesize therefore that both BCMA-like receptors and BAFF-like ligand in lampreys were selected evolutionarily for their receptor-ligand interaction.

In conclusion, the preferential expression of both BCMA-like receptors in the VLRB+ B cell-like lymphocytes and their interaction with the BAFF-like protein in lampreys may reflect an ancient mechanism for BAFF-mediated regulation of B-like lymphocytes. The present results also suggests that the interaction between a BAFF-like ligand and its receptors evolved in a common ancestor of jawed and jawless vertebrates prior to the emergence of the specific interacting receptor BAFFR in jawed vertebrates. Further studies concerning mechanisms of regulation of VLRB-producing B-like lymphocytes by the interaction between lamprey BAFF-like ligand and BCMA-like receptors may facilitate the development of methods to maintain lamprey B-like cells ex vivo.

Supplementary Material

Key points:

Two lamprey BCMA-like (BCMAL) receptors interact with a single lamprey BAFF protein.

BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 genes are differentially expressed during VLRB cell stimulation.

BAFF-based mechanisms for B cell regulation appeared early in vertebrate evolution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katherine Augustus for technical support.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (R01AI072435, R35GM122591, and GM108838), National Science Foundation grants (1655163 and 1755418) and the Georgia Research Alliance.

The lamprey BCMAL1 and BCMAL2 sequences reported in this article have been submitted to GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under accession numbers MK301154 and MK301155.

Abbreviations used in this article:

- BAFF

B-cell activating factor

- APRIL

a proliferation-inducing ligand

- BAFFR

BAFF receptor

- BCMA

B-cell maturation antigen

- TACI

transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor

- EDAR

Ectodysplasin A receptor

- CRD

Cysteine-rich domain

Footnotes

Disclosures

M.D.C. is a cofounder and shareholder of NOVAB, which produces lamprey antibodies for biomedical purposes and J.P.R. is a consultant of NOVAB.

References

- 1.Cancro MP 2004. The BLyS family of ligands and receptors: an archetype for niche-specific homeostatic regulation. Immunological reviews 202: 237–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller JP, Stadanlick JE, and Cancro MP. 2006. Space, selection, and surveillance: setting boundaries with BLyS. Journal of immunology 176: 6405–6410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laabi Y, Gras MP, Brouet JC, Berger R, Larsen CJ, and Tsapis A. 1994. The BCMA gene, preferentially expressed during B lymphoid maturation, is bidirectionally transcribed. Nucleic acids research 22: 1147–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross JA, Johnston J, Mudri S, Enselman R, Dillon SR, Madden K, Xu W, Parrish-Novak J, Foster D, Lofton-Day C, Moore M, Littau A, Grossman A, Haugen H, Foley K, Blumberg H, Harrison K, Kindsvogel W, and Clegg CH. 2000. TACI and BCMA are receptors for a TNF homologue implicated in B-cell autoimmune disease. Nature 404: 995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Bulow GU, Russell H, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, and Bram RJ. 2000. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of murine transmembrane activator and CAML interactor (TACI) with chromosomal localization in human and mouse. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society 11: 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan M, Marsters SA, Grewal IS, Wang H, Ashkenazi A, and Dixit VM. 2000. Identification of a receptor for BLyS demonstrates a crucial role in humoral immunity. Nature immunology 1: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsters SA, Yan M, Pitti RM, Haas PE, Dixit VM, and Ashkenazi A. 2000. Interaction of the TNF homologues BLyS and APRIL with the TNF receptor homologues BCMA and TACI. Current biology : CB 10: 785–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiemann B, Gommerman JL, Vora K, Cachero TG, Shulga-Morskaya S, Dobles M, Frew E, and Scott ML. 2001. An essential role for BAFF in the normal development of B cells through a BCMA-independent pathway. Science 293: 2111–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan M, Brady JR, Chan B, Lee WP, Hsu B, Harless S, Cancro M, Grewal IS, and Dixit VM. 2001. Identification of a novel receptor for B lymphocyte stimulator that is mutated in a mouse strain with severe B cell deficiency. Current biology : CB 11: 1547–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayagaki N, Yan M, Seshasayee D, Wang H, Lee W, French DM, Grewal IS, Cochran AG, Gordon NC, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, and Dixit VM. 2002. BAFF/BLyS receptor 3 binds the B cell survival factor BAFF ligand through a discrete surface loop and promotes processing of NF-kappaB2. Immunity 17: 515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bossen C, and Schneider P. 2006. BAFF, APRIL and their receptors: structure, function and signaling. Seminars in immunology 18: 263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stadanlick JE, Kaileh M, Karnell FG, Scholz JL, Miller JP, Quinn WJ 3rd, Brezski RJ, Treml LS, Jordan KA, Monroe JG, Sen R, and Cancro MP. 2008. Tonic B cell antigen receptor signals supply an NF-kappaB substrate for prosurvival BLyS signaling. Nature immunology 9: 1379–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harless SM, Lentz VM, Sah AP, Hsu BL, Clise-Dwyer K, Hilbert DM, Hayes CE, and Cancro MP. 2001. Competition for BLyS-mediated signaling through Bcmd/BR3 regulates peripheral B lymphocyte numbers. Current biology : CB 11: 1986–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pancer Z, Amemiya CT, Ehrhardt GR, Ceitlin J, Gartland GL, and Cooper MD. 2004. Somatic diversification of variable lymphocyte receptors in the agnathan sea lamprey. Nature 430: 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alder MN, Rogozin IB, Iyer LM, Glazko GV, Cooper MD, and Pancer Z. 2005. Diversity and function of adaptive immune receptors in a jawless vertebrate. Science 310: 1970–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alder MN, Herrin BR, Sadlonova A, Stockard CR, Grizzle WE, Gartland LA, Gartland GL, Boydston JA, Turnbough CL Jr., and Cooper MD. 2008. Antibody responses of variable lymphocyte receptors in the lamprey. Nature immunology 9: 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo P, Hirano M, Herrin BR, Li J, Yu C, Sadlonova A, and Cooper MD. 2009. Dual nature of the adaptive immune system in lampreys. Nature 459: 796–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirano M, Guo P, McCurley N, Schorpp M, Das S, Boehm T, and Cooper MD. 2013. Evolutionary implications of a third lymphocyte lineage in lampreys. Nature 501: 435–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pancer Z, Saha NR, Kasamatsu J, Suzuki T, Amemiya CT, Kasahara M, and Cooper MD. 2005. Variable lymphocyte receptors in hagfish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 102: 9224–9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogozin IB, Iyer LM, Liang L, Glazko GV, Liston VG, Pavlov YI, Aravind L, and Pancer Z. 2007. Evolution and diversification of lamprey antigen receptors: evidence for involvement of an AID-APOBEC family cytosine deaminase. Nature immunology 8: 647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasamatsu J, Sutoh Y, Fugo K, Otsuka N, Iwabuchi K, and Kasahara M. 2010. Identification of a third variable lymphocyte receptor in the lamprey. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107: 14304–14308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Das S, Herrin BR, Hirano M, and Cooper MD. 2013. Definition of a third VLR gene in hagfish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 15013–15018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han BW, Herrin BR, Cooper MD, and Wilson IA. 2008. Antigen recognition by variable lymphocyte receptors. Science 321: 1834–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano M, Das S, Guo P, and Cooper MD. 2011. The evolution of adaptive immunity in vertebrates. Advances in immunology 109: 125–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehm T, McCurley N, Sutoh Y, Schorpp M, Kasahara M, and Cooper MD. 2012. VLR-based adaptive immunity. Annual review of immunology 30: 203–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das S, Li J, Hirano M, Sutoh Y, Herrin BR, and Cooper MD. 2015. Evolution of two prototypic T cell lineages. Cellular immunology 296: 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehm T, Hirano M, Holland SJ, Das S, Schorpp M, and Cooper MD. 2018. Evolution of Alternative Adaptive Immune Systems in Vertebrates. Annual review of immunology 36: 19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das S, Sutoh Y, Hirano M, Han Q, Li J, Cooper MD, and Herrin BR. 2016. Characterization of Lamprey BAFF-like Gene: Evolutionary Implications. Journal of immunology 197: 2695–2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redmond AK, Pettinello R, and Dooley H. 2017. Outgroup, alignment and modelling improvements indicate that two TNFSF13-like genes existed in the vertebrate ancestor. Immunogenetics 69: 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edgar RC 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC bioinformatics 5: 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, and Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic acids research 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, and Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature methods 8: 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letunic I, Doerks T, and Bork P. 2015. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic acids research 43: D257–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitou N, and Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular biology and evolution 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, and Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular biology and evolution 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones DT, Taylor WR, and Thornton JM. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Computer applications in the biosciences : CABIOS 8: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, and Barton GJ. 2009. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25: 1189–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wittig I, Braun HP, and Schagger H. 2006. Blue native PAGE. Nature protocols 1: 418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han Q, Das S, Hirano M, Holland SJ, McCurley N, Guo P, Rosenberg CS, Boehm T, and Cooper MD. 2015. Characterization of Lamprey IL-17 Family Members and Their Receptors. Journal of immunology 195: 5440–5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hymowitz SG, Patel DR, Wallweber HJ, Runyon S, Yan M, Yin J, Shriver SK, Gordon NC, Pan B, Skelton NJ, Kelley RF, and Starovasnik MA. 2005. Structures of APRIL-receptor complexes: like BCMA, TACI employs only a single cysteine-rich domain for high affinity ligand binding. The Journal of biological chemistry 280: 7218–7227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park HH 2018. Structure of TRAF Family: Current Understanding of Receptor Recognition. Frontiers in immunology 9: 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foight GW, and Keating AE. 2016. Comparison of the peptide binding preferences of three closely related TRAF paralogs: TRAF2, TRAF3, and TRAF5. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 25: 1273–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye H, Park YC, Kreishman M, Kieff E, and Wu H. 1999. The structural basis for the recognition of diverse receptor sequences by TRAF2. Molecular cell 4: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ni CZ, Oganesyan G, Welsh K, Zhu X, Reed JC, Satterthwait AC, Cheng G, and Ely KR. 2004. Key molecular contacts promote recognition of the BAFF receptor by TNF receptor-associated factor 3: implications for intracellular signaling regulation. Journal of immunology 173: 7394–7400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrison MD, Reiley W, Zhang M, and Sun SC. 2005. An atypical tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor-binding motif of B cell-activating factor belonging to the TNF family (BAFF) receptor mediates induction of the noncanonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry 280: 10018–10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karpusas M, Cachero TG, Qian F, Boriack-Sjodin A, Mullen C, Strauch K, Hsu YM, and Kalled SL. 2002. Crystal structure of extracellular human BAFF, a TNF family member that stimulates B lymphocytes. Journal of molecular biology 315: 1145–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oren DA, Li Y, Volovik Y, Morris TS, Dharia C, Das K, Galperina O, Gentz R, and Arnold E. 2002. Structural basis of BLyS receptor recognition. Nature structural biology 9: 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magis C, van der Sloot AM, Serrano L, and Notredame C. 2012. An improved understanding of TNFL/TNFR interactions using structure-based classifications. Trends in biochemical sciences 37: 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodmer JL, Schneider P, and Tschopp J. 2002. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends in biochemical sciences 27: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith CA, Farrah T, and Goodwin RG. 1994. The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell 76: 959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hatzoglou A, Roussel J, Bourgeade MF, Rogier E, Madry C, Inoue J, Devergne O, and Tsapis A. 2000. TNF receptor family member BCMA (B cell maturation) associates with TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 and activates NF-kappa B, elk-1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Journal of immunology 165: 1322–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shu HB, and Johnson H. 2000. B cell maturation protein is a receptor for the tumor necrosis factor family member TALL-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97: 9156–9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson JS, Bixler SA, Qian F, Vora K, Scott ML, Cachero TG, Hession C, Schneider P, Sizing ID, Mullen C, Strauch K, Zafari M, Benjamin CD, Tschopp J, Browning JL, and Ambrose C. 2001. BAFF-R, a newly identified TNF receptor that specifically interacts with BAFF. Science 293: 2108–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novak AJ, Darce JR, Arendt BK, Harder B, Henderson K, Kindsvogel W, Gross JA, Greipp PR, and Jelinek DF. 2004. Expression of BCMA, TACI, and BAFF-R in multiple myeloma: a mechanism for growth and survival. Blood 103: 689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Connor BP, Raman VS, Erickson LD, Cook WJ, Weaver LK, Ahonen C, Lin LL, Mantchev GT, Bram RJ, and Noelle RJ. 2004. BCMA is essential for the survival of long-lived bone marrow plasma cells. The Journal of experimental medicine 199: 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.